This is a blog about the 80s independent comics publisher Eclipse Comics  written by somebody with no association whatsoever with that publisher.

written by somebody with no association whatsoever with that publisher.

To the right, there should be a menu listing all the blog posts in this series, and below there’s a capsule history of Eclipse Comics with an index over all the comics (and some miscellany) they published. One thing I’ve found interesting about Eclipse is that over the years, Eclipse changed a lot, so I’ve broken the index into chunks. Somewhat arbitrary chunks, because Eclipse continued publishing comics from previous periods even as they shifted focus. Still, you can sort of see how they changed publishing strategies several times, pivoting from one approach to another.

I’m also going to be quoting quite a lot from an interview with Eclipse publisher and co-owner Dean Mullaney here.

The Refuge for Disgruntled Marvel Writers

Eclipse Comics’ first publication was the Sabre graphic novel, written by Don McGregor, a writer best-known for his work at Marvel Comics, and that set the tone for the first years of Eclipse. McGregor, along with other high-profile writers like Steve Gerber, Jim Starlin, Doug Moench, and artists like P. Craig Russell and Marshall Rogers, were dissatisfied with Marvel’s editorial restrictions, and also wanted to own their own work. They all ended up doing work for Eclipse Comics. And almost all of them went back to Marvel after Archie Goodwin started the Epic imprint, which allowed the creators to keep ownership to their works.

Here’s publisher Dean Mullaney:

RA: What prompted you to make the jump to comic publisher?

DM: I, like many fans, became disgusted with how Marvel was treating its creative talent. One night in 1977, at Don McGregor’s loft on the Bowery, I noticed a penciled drawing of (what I thought was) Jimi Hendrix on the wall. Don explained that it was a new character he was working on with Paul Gulacy. By the time the night was over, Eclipse was conceived with the idea that not only would he and Paul be given creative freedom, but that we would emulate the high-quality paper format of the Ed Aprill strip reprints. At the time, all comics were printed on crappy newsprint using plastic plates. Our concept was to use metal plates, print on 100 lb. vellum, and sell it as a book. We called it a “graphic album,” and it became the first graphic novel published for the comic’s specialty market.

RA: Sabre came out in 1978. Were you aware that McGregor had previously used the character in a couple of the Killraven strips over at Marvel? There he was a dark-skinned Hispanic but his name, weaponry and general appearance was basically the same.

DM: I don’t recall the Sabre character in Killraven. As I said however, Sabre was already conceived when I came aboard.

RA: What can you tell us about starting up Eclipse?

DM: I started Eclipse with whatever minimal publishing knowledge I gained publishing fanzines. The goals of Eclipse were threefold: allow creators to own their own material, to publish work I liked and thought other fans would like, and to publish in a high-quality format. My brother Jan and I formed the company. Jan’s band was touring with Bad Company at the time, so he had a little money and he asked me how much money it would cost to get it started. I said “$2,000” and that’s what he put up. Although it wasn’t much money, I thought, using my accounting background, that we could get by. I had agreed to pay Don, Paul and Annette Kawecki their going Marvel rates. No one was asked to work on the cheap. So, as my friend Chuck Dixon likes to say about me, I used guerrilla marketing techniques from the start. I wrote individual solicitation letters to fans whose names appeared in letters pages, and to individual store owners who advertised in RBCC, The Comic Reader, Alan Light’s The Comic-Buyer’s Guide, etc. I brazenly asked them all to pay in advance for the orders. This money helped fund the project. Today, you need an investment banker; back then all we needed were fans starved for something good, and storeowners willing to pay up front in order to get new comics to sell. I also published a Sabre poster in December 1977, partially to appease people for the delay in the graphic album, but also to generate more working capital.

Then I went over the bridge to Brooklyn to talk with the Big Man himself—Phil Seuling, the only distributor to the comics market at the time. Phil put his reaction to my pitch on paper and handed it to me: a cartoon of Phil’s head, hair standing straight up, saying “$5.00 for a comic book!!!!”

Despite his bombastic outward appearance, Phil was one of the nicest people I ever met in comics. He was also one of the most encouraging to young publishers (I was 23 at the time). He agreed to take 200 copies and sent a solicitation out to his stores. A short time later, I got a call from Phil telling me to get over to his office. I thought he wanted his money back, but as it turned out, the reaction to his solicitation was so good that he wanted to double his order. Before Sabre saw print, Phil had upped his order several more times, and based on the strength of his continuing orders, we went into a second printing!

Pacific Takeover

So for the first six years, from 1978 to 1984, Eclipse was a small, but well-respected publisher, publishing what seemed to be a cohesive and well-curated set of comics. In addition to the Marvel diaspora, they’d also dipped their toes into other waters, with Zot! and DNAgents, but we’re talking mostly superior genre comics.

Then Pacific Comics went bankrupt. Not due to publishing comics that didn’t sell, but because they had a distribution arm that went under. Eclipse bought the rights to all the comics that were already in the pipeline, and also the rights to comics that were only in the planning phase. This changed the tone and size of the company overnight: In one month, December of 1984, they published a whopping eleven ex-Pacific books, which came on top of the normal three to five they were normally doing.

The Imperial Phase

This cash infusion from the Pacific titles seemed to have two effects: First, having gotten the taste for easy pickings, Eclipse spent the next half year doing one micro-series after another of horror reprints, and most of them taken from the little-known Web of Horror early-70s magazine, along with a smattering of stories from Warren titles.

Then it all segued into the launch of their two most commercially successful titles, Scout and Airboy, as well as their most critically acclaimed title, Miracleman (which was part of the Pacific deal).

My guess is that Eclipse were finally making some money and getting their comics out to a larger audience. Which makes their next phase all the more bewildering, but may be related to The Flood.

The Black and White Boom and Bust

Eclipse Comics may not have created the speculator craze that was The Black and White Boom, but they certainly got in on the action. Adolescent Radioactive Black Belt Hamsters was considered, by many, to be patient zero in this phenomenon which almost wiped out alternative comics in 1987.

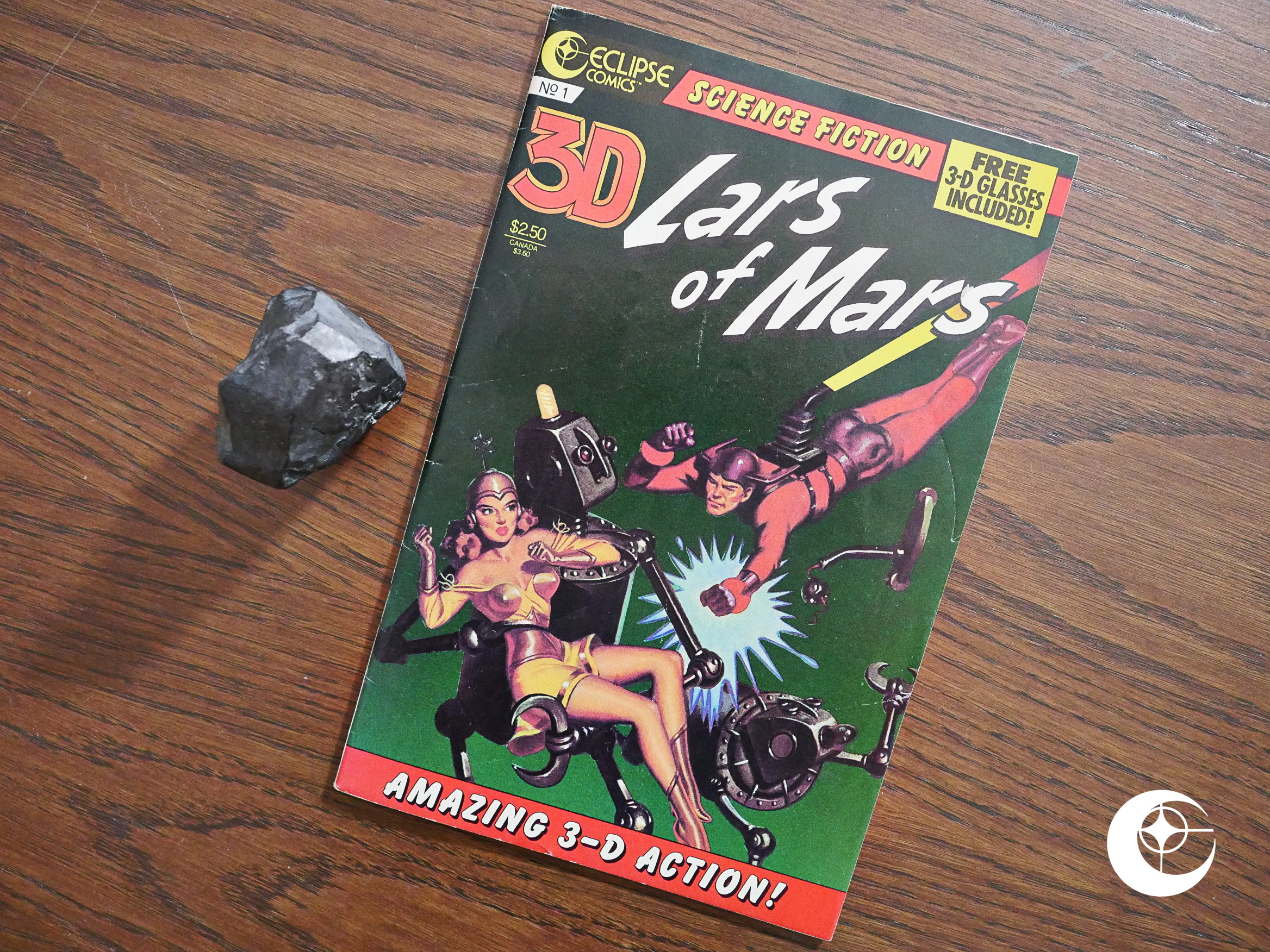

While also shovelling out whatever black and white comic they could get their hands on, Eclipse also published a bewildering number of 3-D comics, and foreshadows Eclipse’s move from critically respected but small indie comics publisher to gimmick-first product extrusion factory.

How much of this was caused by geniune enthusiasm for 3-D and really bad black and white comics I have no idea. But it’s perhaps worth nothing these comics mostly appeared after the big Guerneville flood in February 1986, which completely flooded Eclipse’s offices and warehouse. Eclipse Comics had, at the time, a major mail-order back-issue operation going, and losing all the backstock had to be a major economic blow.

The Major Player Gambit

Eclipse buckled down and tried to make their action series a thing, centred around Airboy and related properties. This included the company-wide crossover series Total Eclipse, written by Marv Wolfman, the man who’d done Crisis on Infinite Earths for DC Comics. It didn’t really work out well, and Eclipse started stepping away from the monthly comics market… slowly.

Respectable and Adult

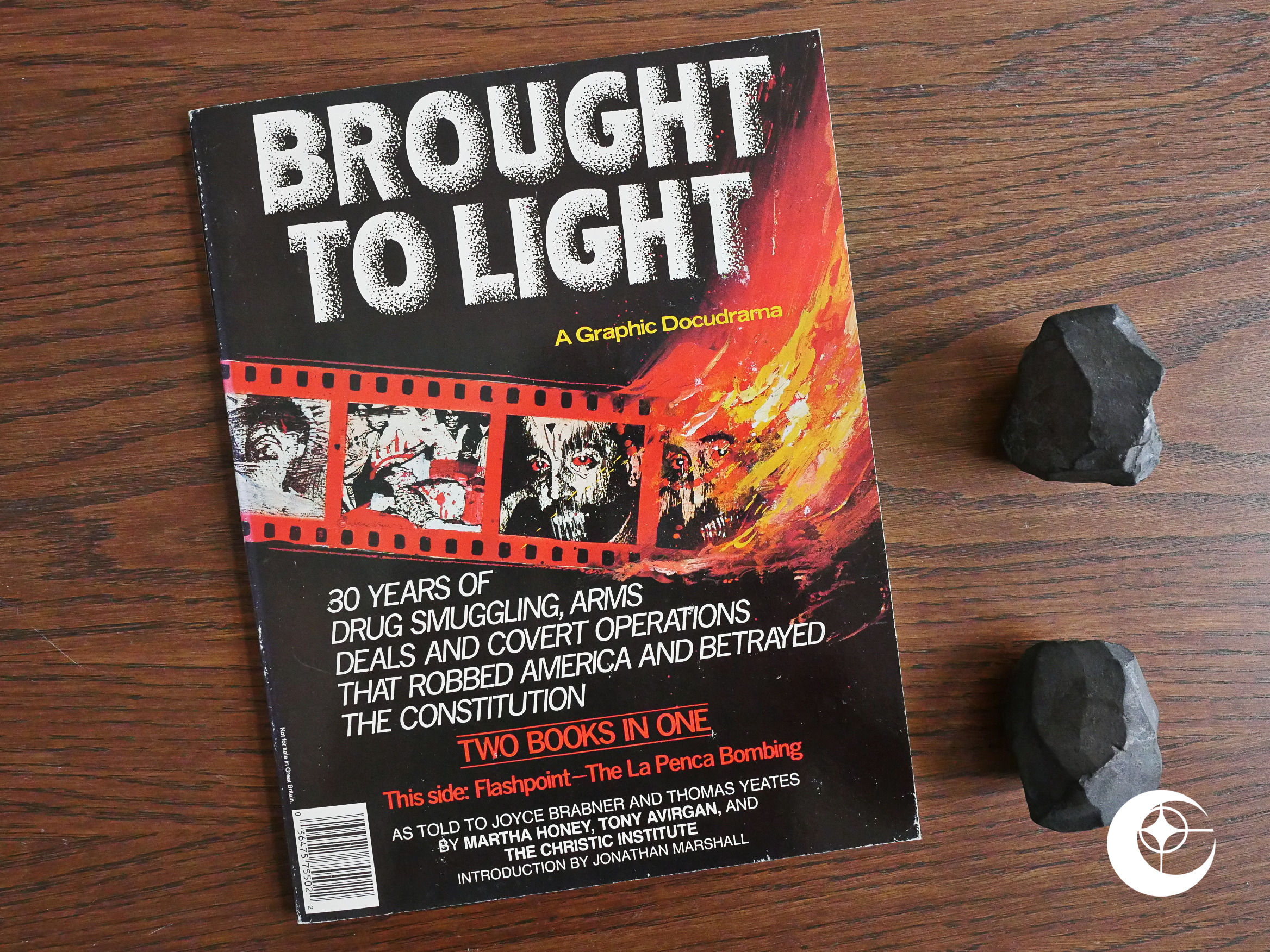

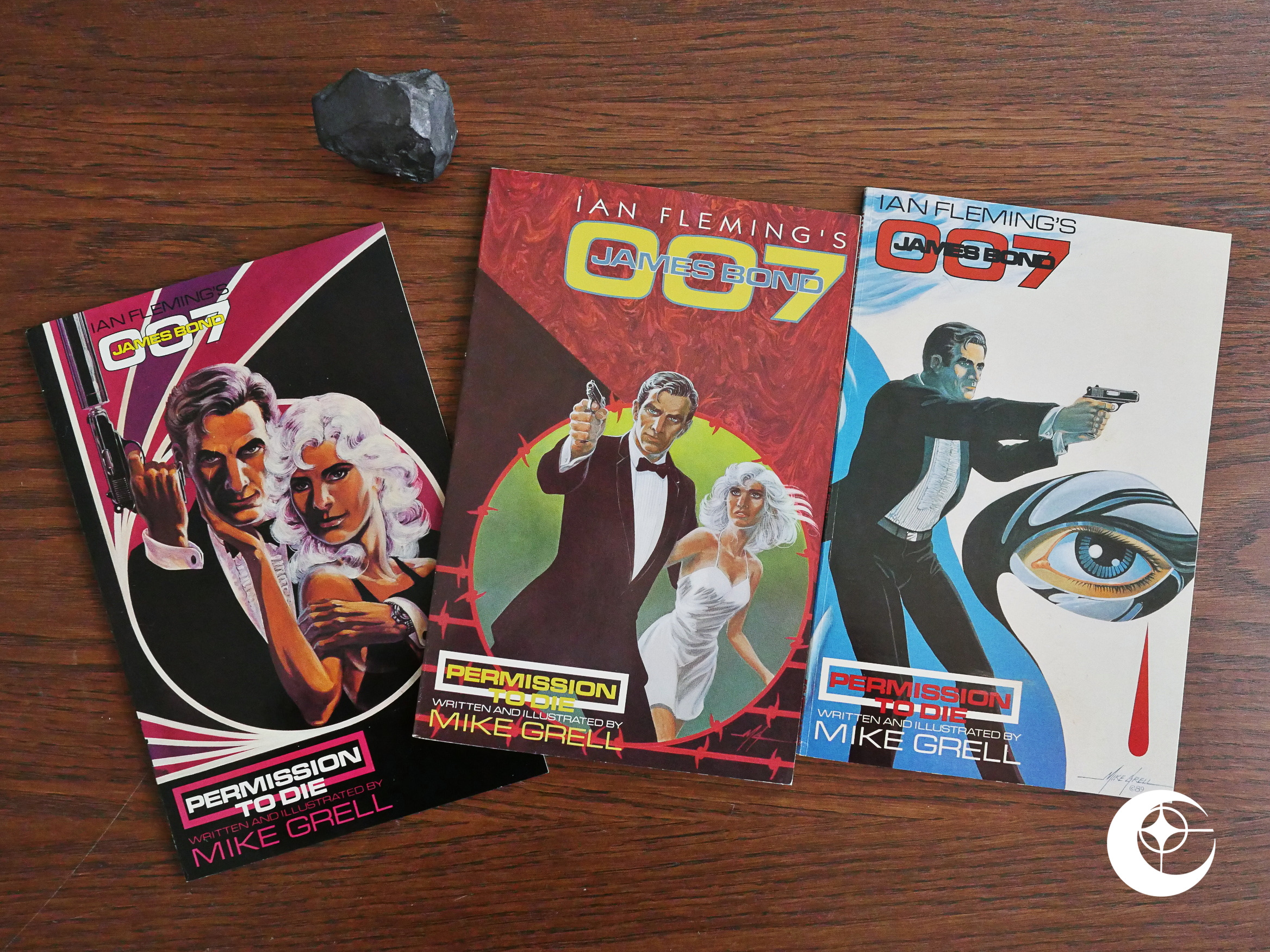

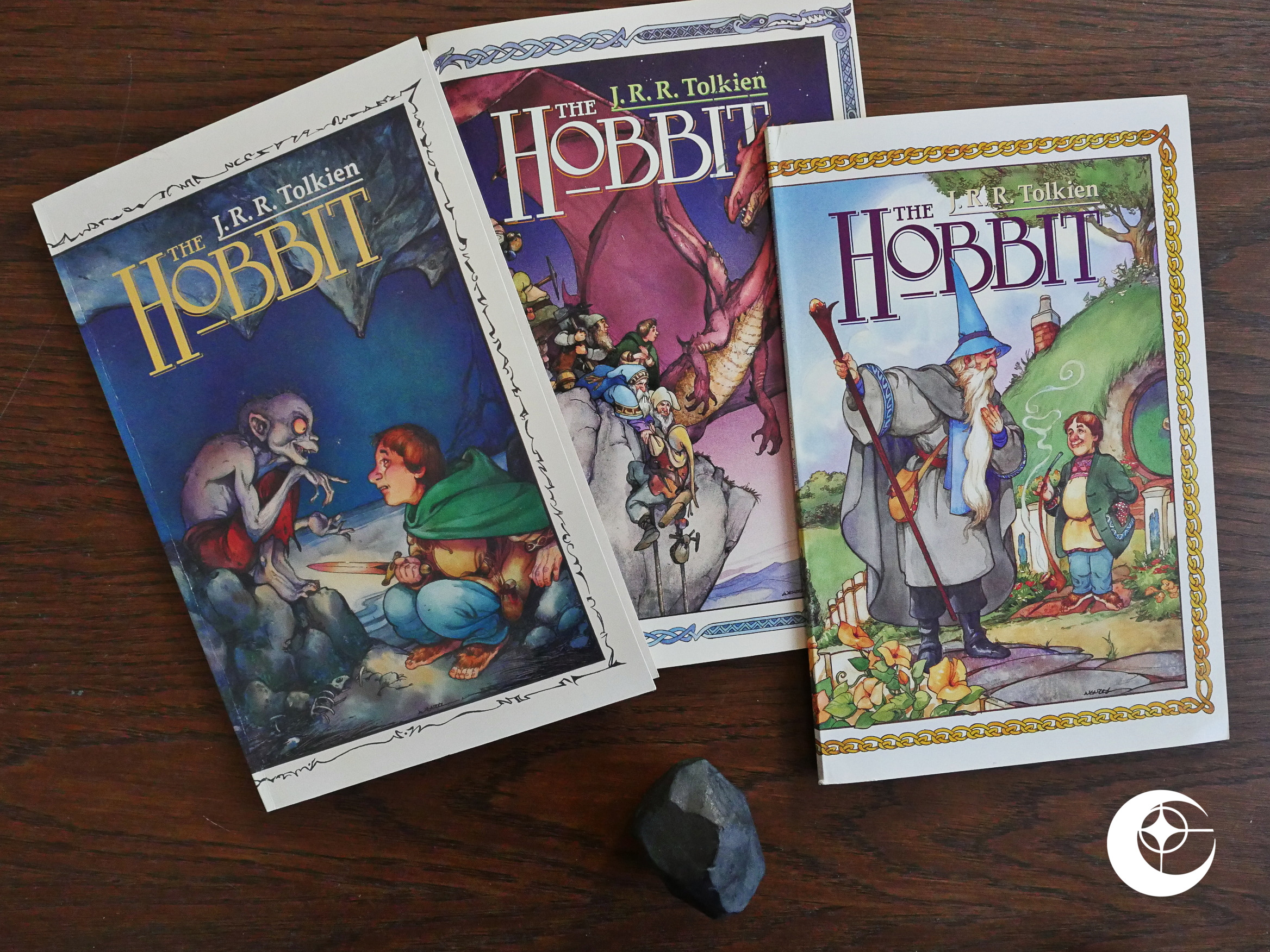

When running a mainstream-ish cheap action/adventure comic book company wasn’t sustainable, Eclipse went all in on upscale graphic novels. Most of these were adaptations of famous properties (like James Bond and The Hobbit), but also a number of political books like Brought to Light, which was about the CIAs crimes. This period also saw Eclipse continue their very successful Japanese translations, and their entry into what would come to consume Eclipse almost completely for their last couple of years: Non-sports trading cards.

Decline and Fall

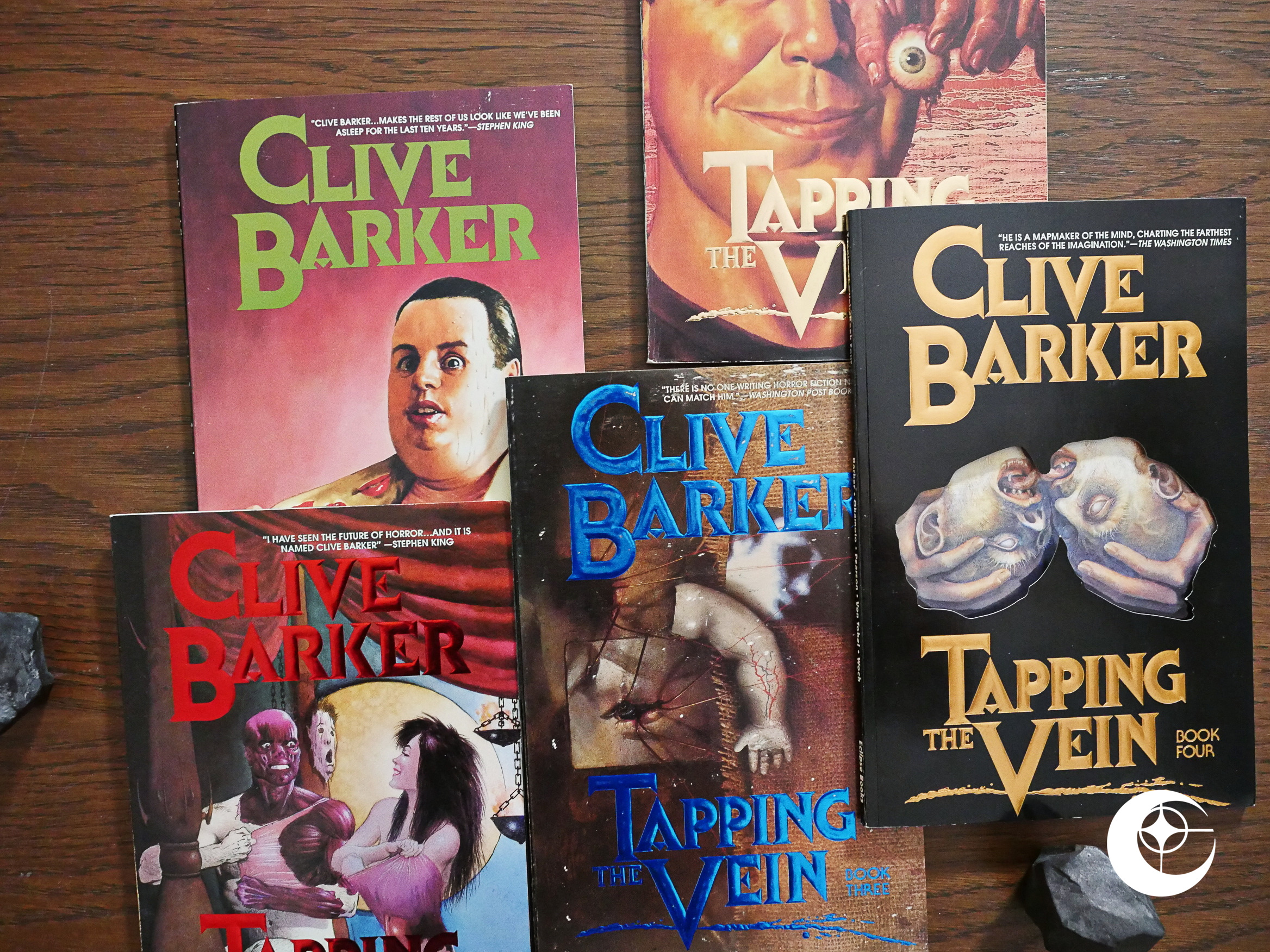

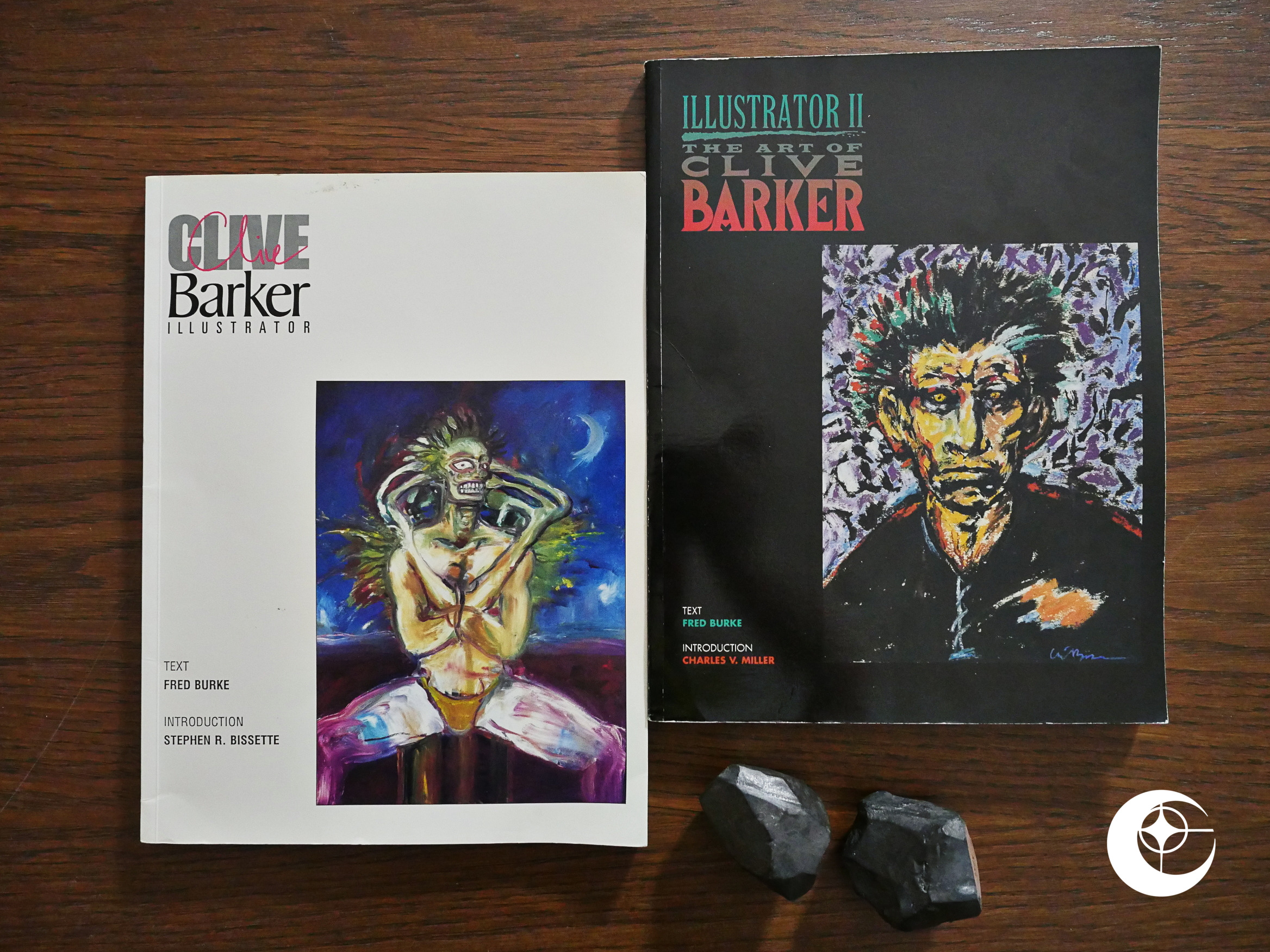

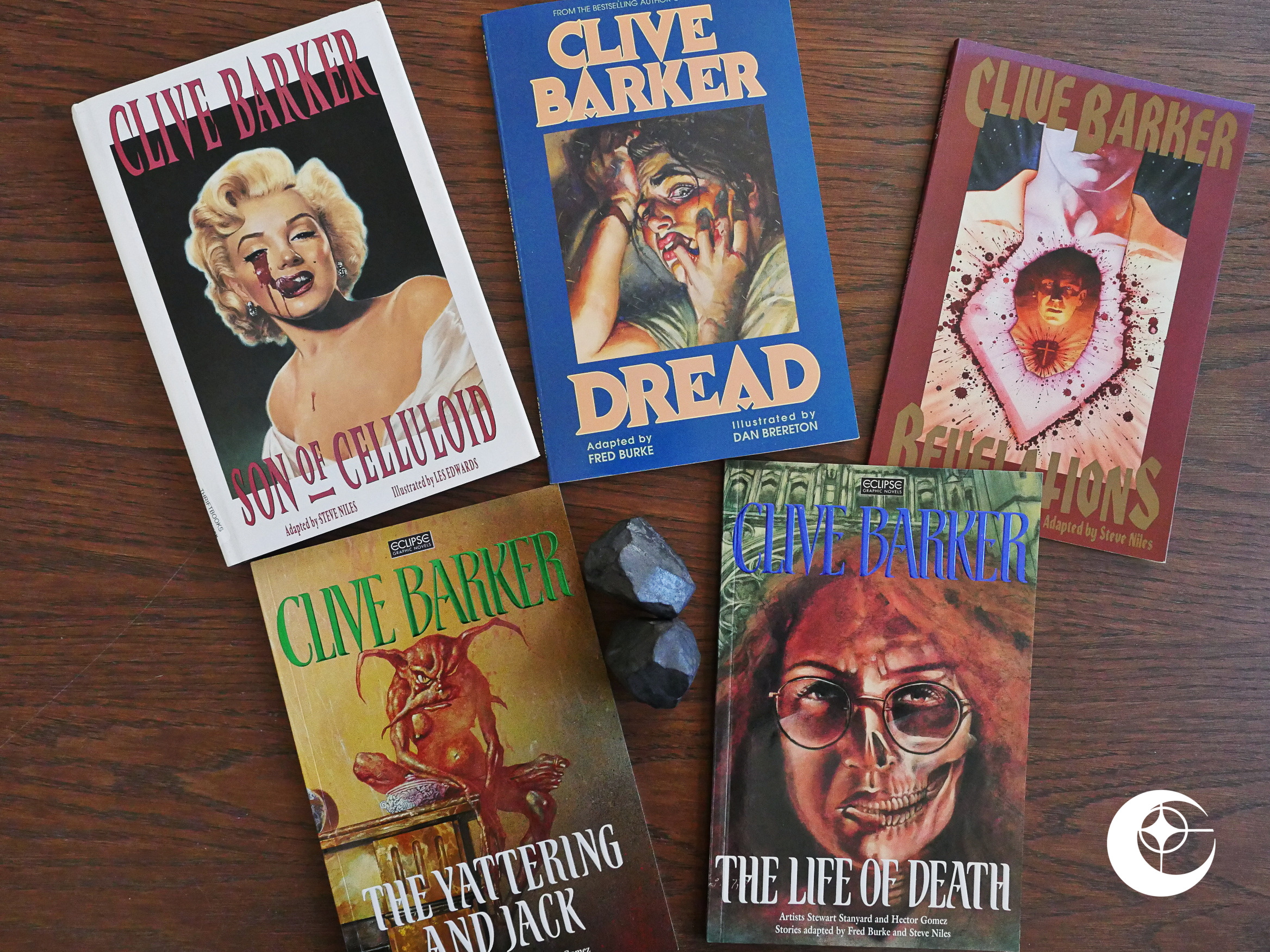

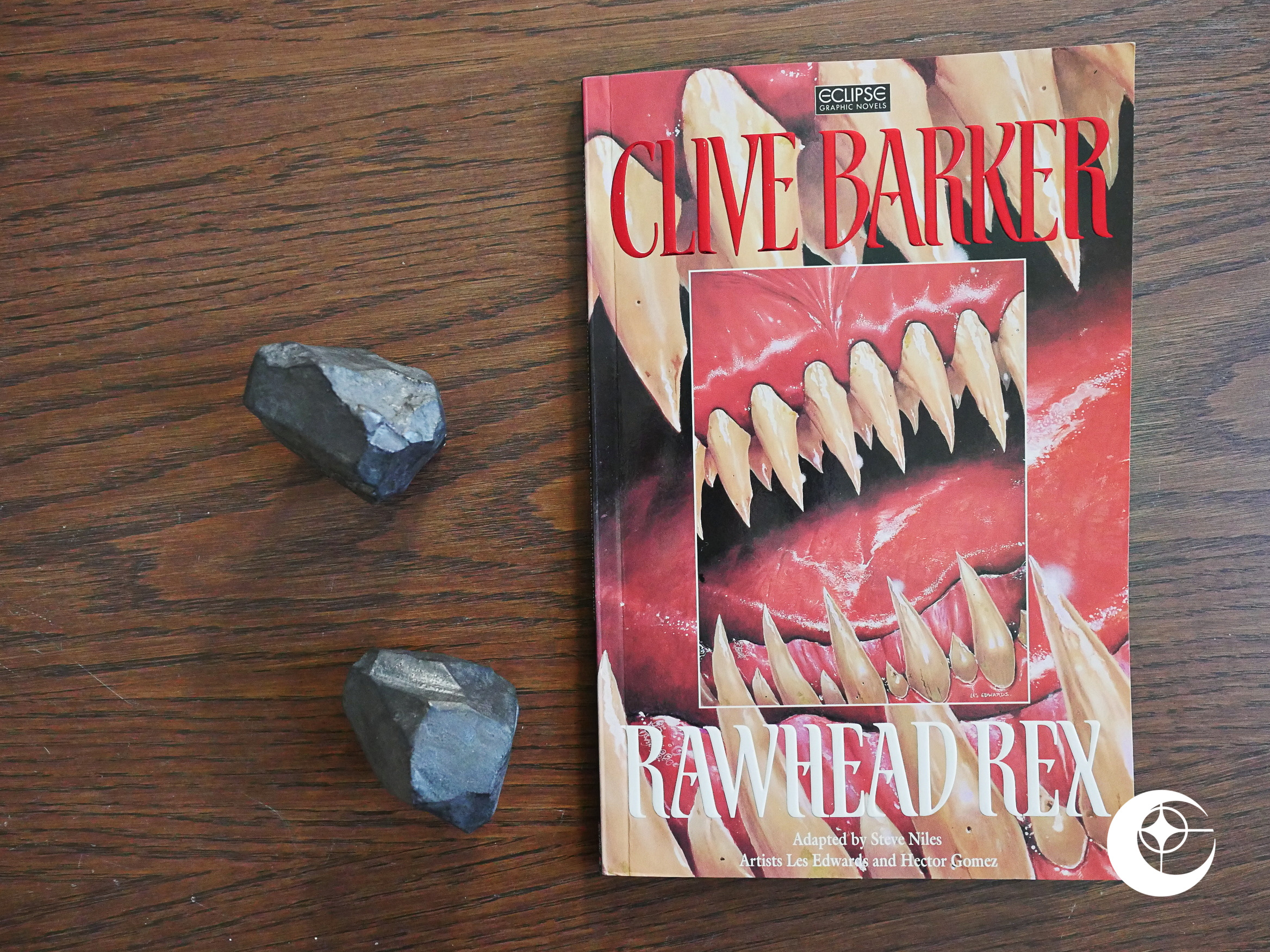

The most successful property Eclipse had in its last few years was a deal with Clive Barker to adapt all of his Books of Blood short stories: The final book they published before going bankrupt was one of these. By 1992, rumours about Eclipse’s money troubles had begun popping up in the trade press, and writers like Neil Gaiman had stopped doing work for them until they got paid for the last thing they did.

Eclipse also went into a distribution deal with HarperCollins, and publisher Dean Mullaney claims that was the reason for their money woes:

RA: What did cause the collapse of Eclipse in 1994?

DM: I’ve never really told anyone why Eclipse folded. It had nothing to do with cat and I getting divorced. First of all, the comics specialty market was in the toilet. Like every other publisher, we were scrambling to sell enough comics to keep things going. We didn’t have the luxury of losing $150 million a year like one of competitors did. We were a small, family-run business. So things were incredibly tight. Eclipse didn’t have bankable continuing monthly series. We often published a wide variety of one-shots, mini-series and graphic novels because we liked them. Comic shops were closing and the remaining shops, for the most part, drastically cut orders on anything not from Marvel or DC.

We saw the comics specialty market alone was not a receptive place for our company’s survival, let alone expansion. My dream, from 1978 when I published Sabre, was to get graphic novels in mainstream bookstores. As the direct market became overcome with greed and milking readers by focusing on comics as investment, multiple covers, etc., I saw the future in the bookstores. We had great success with Ballantine on The Hobbit (75,000 copies in the first half year, not counting the comics shops where we sold 25,000 copies of the collection and over 100,000 each of the three $4.95 issues), and so when the opportunity arose to have a co-publishing deal with one of the world’s largest publishers, I had to go for it. We entered into a co-publishing deal with HarperCollins. Harper published Clive Barker and didn’t want us taking his graphic novels to a competitor. Harper had also bought Unwyn-Hyman, publishers of Tolkien’s work in every country but the US, and again didn’t want a competitor to have the graphic novel. They also realized that we could get the graphic novel rights to books published by other houses and bring them to Harper (this was before graphic novel rights were on the mind of mainstream publishers).

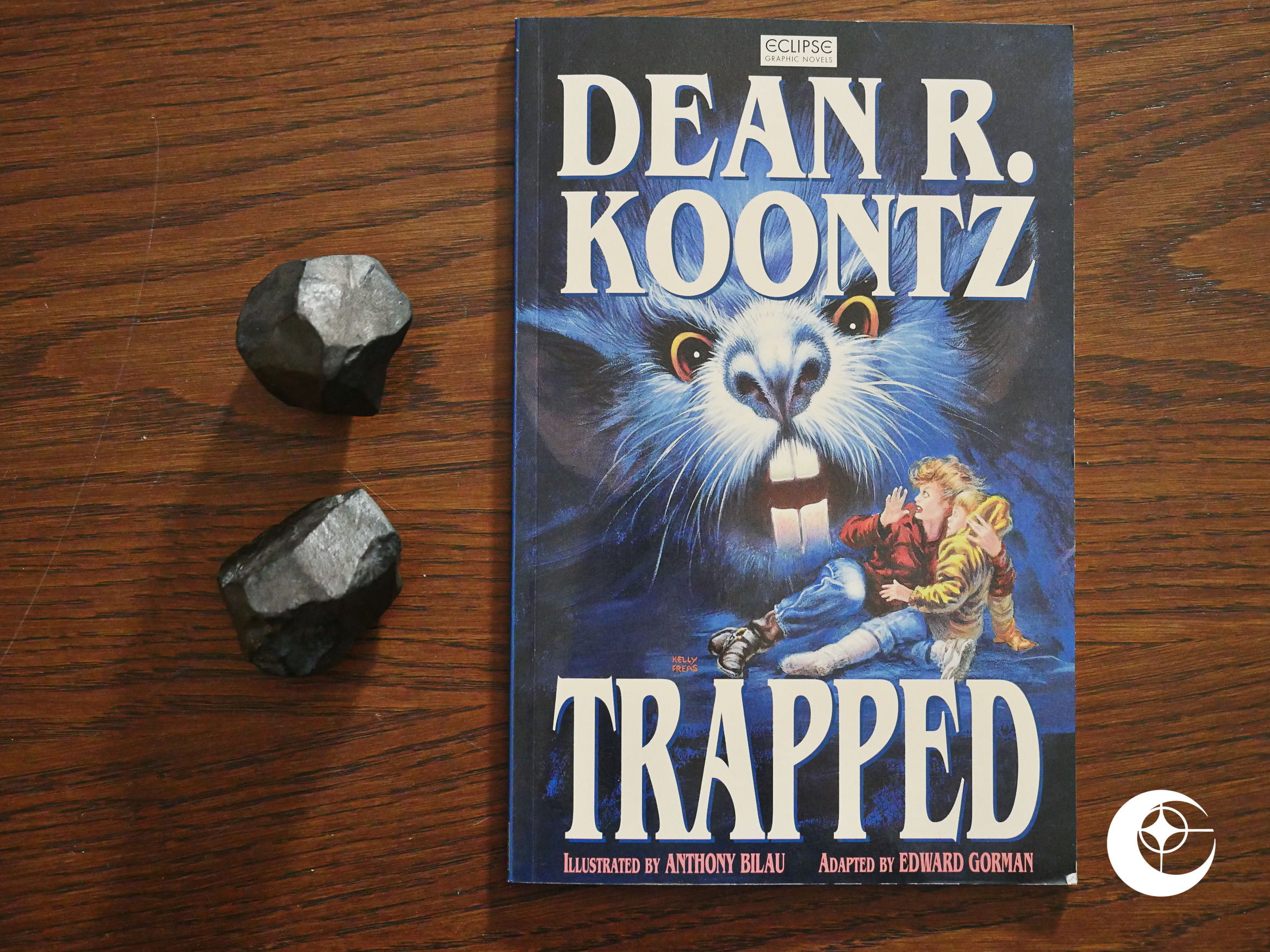

It was an exclusive deal both ways. In the beginning, it was a fantastic relationship. We did all the production and were invited to give presentations at all their sales meetings in the US and UK. They made fantastic floor and counter displays for bookstores. When they released The Hobbit graphic novel, they sold more copies in the UK alone than Ballantine did in all the US! The problems started when we asked for sales figures on the other books (Miracleman, Clive Barker’s titles, Dragonflight, Dean Koontz’s Trapped, etc.). We never—EVER—received a single sales statement. Therefore, no royalty statements. So there I was, paying advances to creators (bigger than the top rates in the field at the time—hey, we were going to be in bookstores, too!), tying up all my capital. And then nothing from Harper. No statements, no money. Meanwhile, creators were naturally asking for THEIR statements and royalitites. I explained the situation, but still never got anything from Harper. It go to the point that I had no cash left to even carry on normal business because we had laid out everything we had for advances.

All that was left to do was sell off every piece of inventory I could get my hands on, pay all the little guys (individual creators and small vendors), and stiff the large ones (printers and freight companies). And declare bankruptcy.

I still have no idea how many copies of our graphic novels Harper sold, or what they did with the money owed us and creators.

But my plans for placing graphic novels in bookstores was still a good one. I just picked the wrong publisher and was about ten years too early. If Eclipse were around now, there’s no doubt that we would be the leading graphic novel publisher in mainstream bookstores.

However, Eclipse Comics were sued by Toren Smith, who won a judgement of $120K against Eclipse apparently for failing to pay him what they owed him. They filed for bankruptcy a few months after the sentencing.

And that was that.

Sabre (1978)

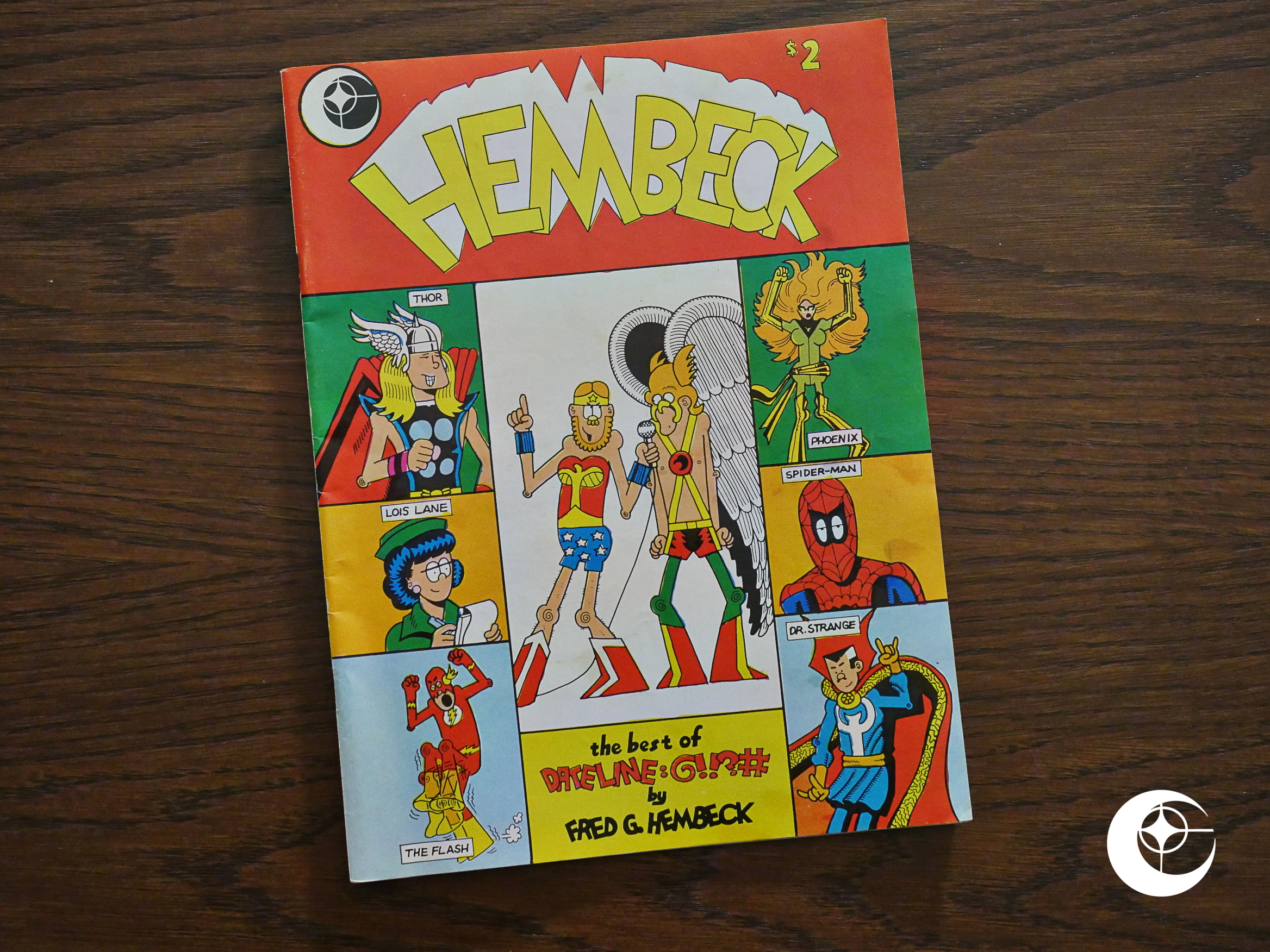

Sabre (1978) Hembeck: The Best of Dateline: @!!?# (1979) #1

Hembeck: The Best of Dateline: @!!?# (1979) #1 Night Music (1979)

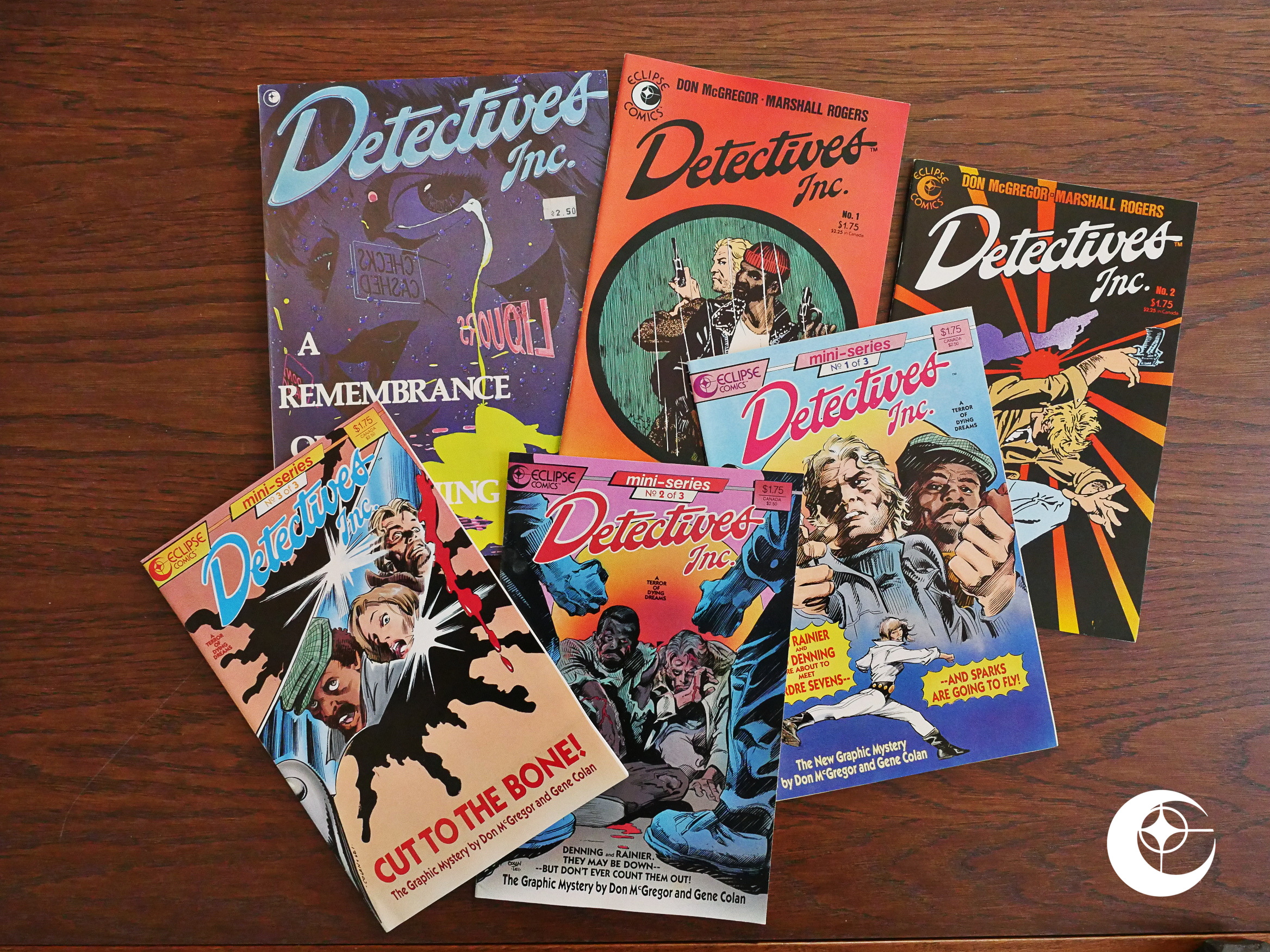

Night Music (1979) Detectives, Inc. (1980)

Detectives, Inc. (1980) Stewart the Rat (1980)

Stewart the Rat (1980) The Mike Mist Minute Mist-Eries (1981) #1

The Mike Mist Minute Mist-Eries (1981) #1 Eclipse, the Magazine (1981) #1-8

Eclipse, the Magazine (1981) #1-8 The Price (1981)

The Price (1981) Buster Keaton (1982)

Buster Keaton (1982) Destroyer Duck (1982) #1-7

Destroyer Duck (1982) #1-7 I Saw It (1982)

I Saw It (1982) Scorpio Rose (1983) #1-2

Scorpio Rose (1983) #1-2 Ms. Tree’s Thrilling Detective Adventures (1983) #1-3

Ms. Tree’s Thrilling Detective Adventures (1983) #1-3 John Law Detective (1983) #1

John Law Detective (1983) #1 The DNAgents (1983) #1-24

The DNAgents (1983) #1-24 Eclipse Monthly (1983) #1-10

Eclipse Monthly (1983) #1-10 I Am Coyote (1984)

I Am Coyote (1984) Aztec Ace (1984) #1-15

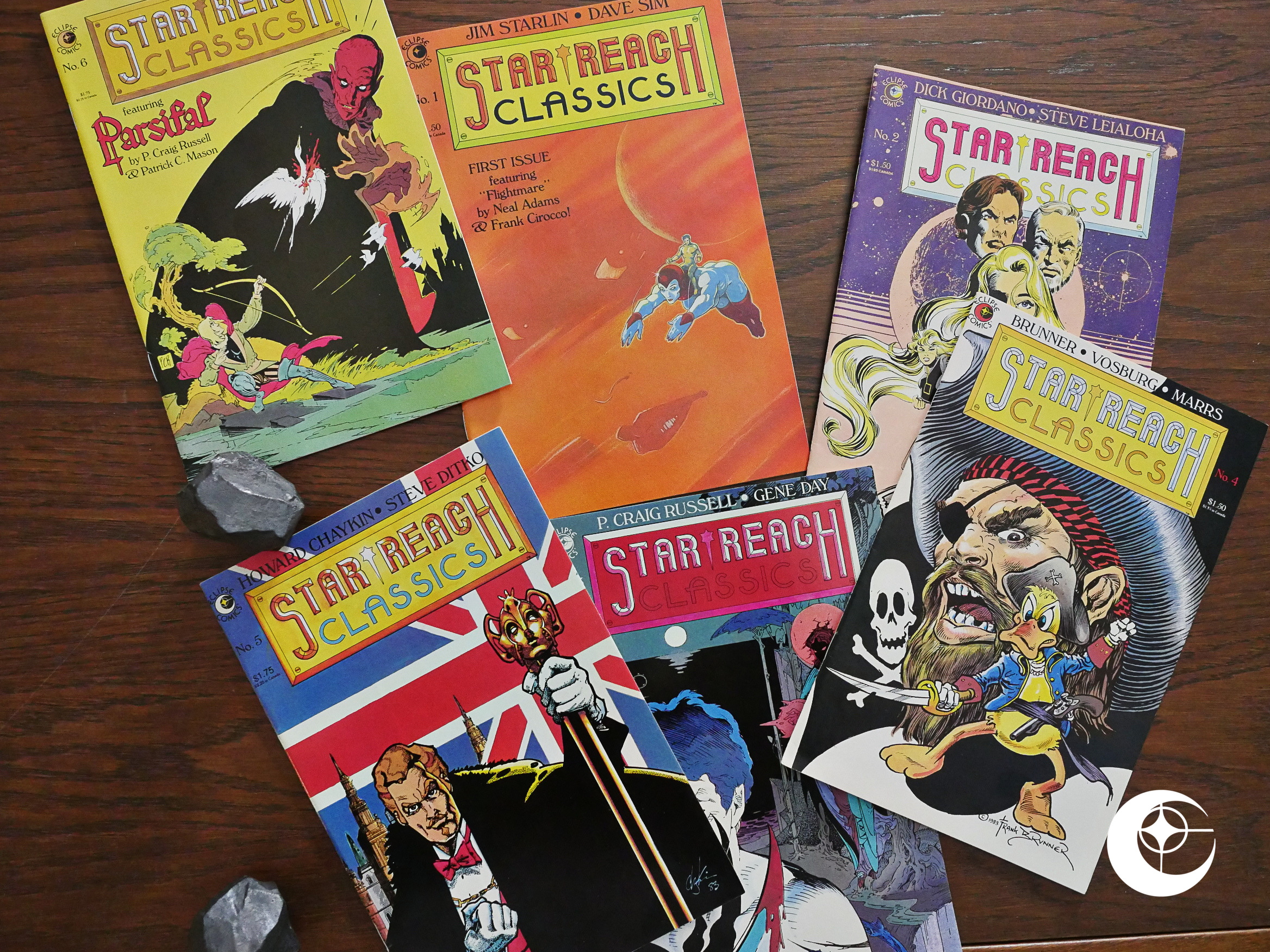

Aztec Ace (1984) #1-15 Star*Reach Classics (1984) #1-6

Star*Reach Classics (1984) #1-6 Zot! (1984) #1-36

Zot! (1984) #1-36 Crossfire (1984) #1-26

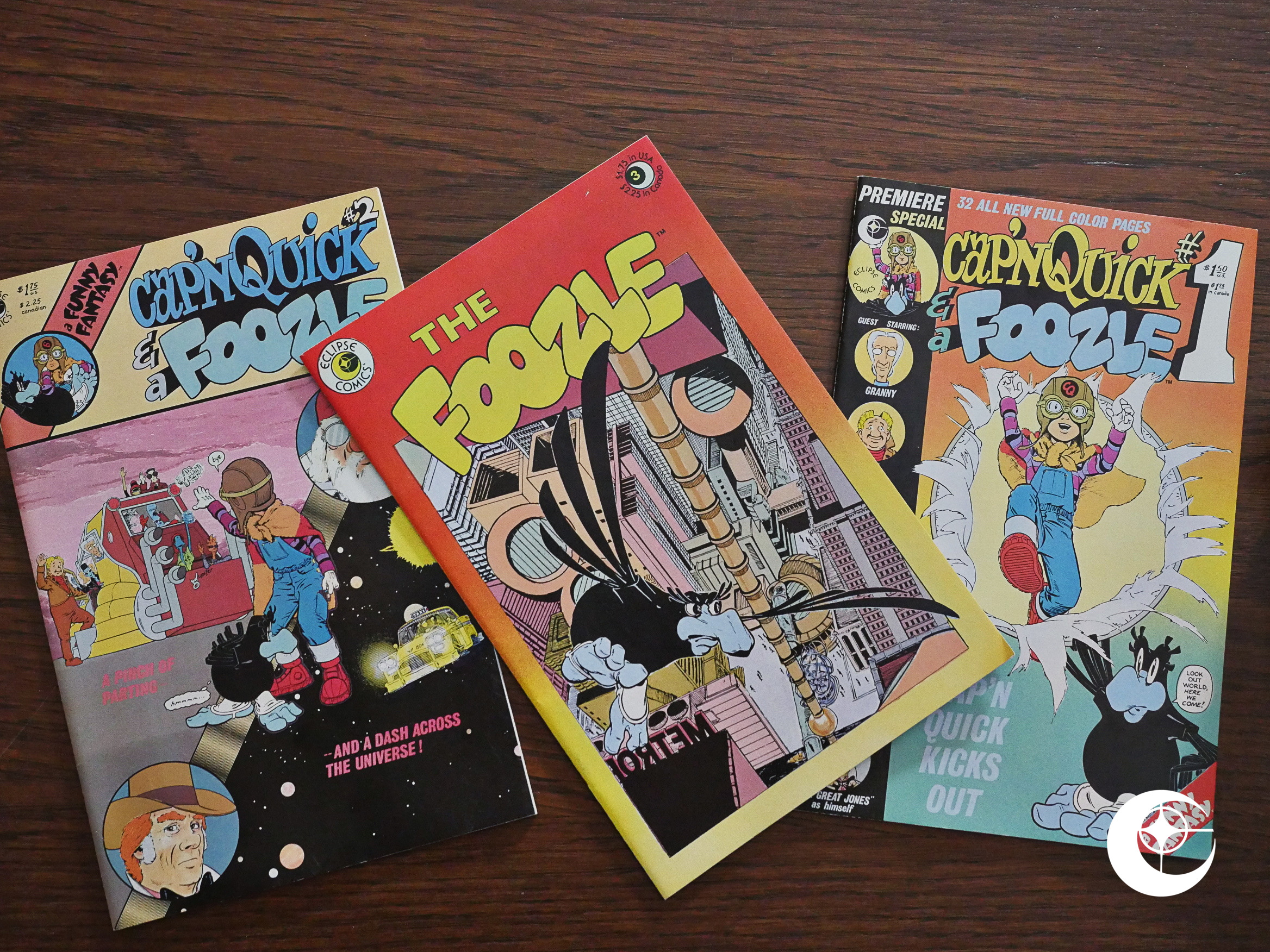

Crossfire (1984) #1-26 Cap’n Quick & a Foozle (1984) #1-2

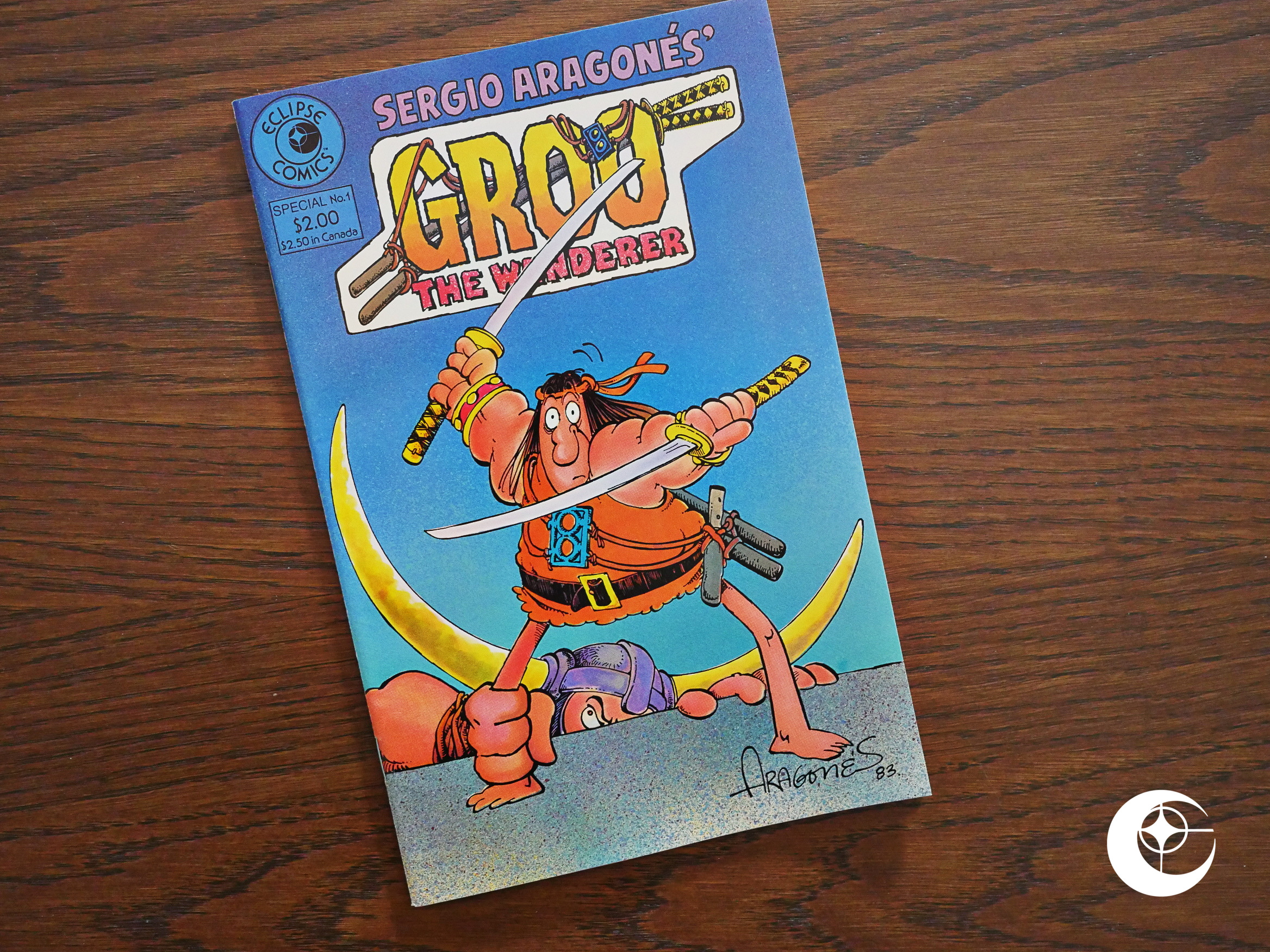

Cap’n Quick & a Foozle (1984) #1-2 Groo Special (1984) #1

Groo Special (1984) #1 Alien Worlds (1984) #8-9

Alien Worlds (1984) #8-9 Axel Pressbutton (1984) #1-6

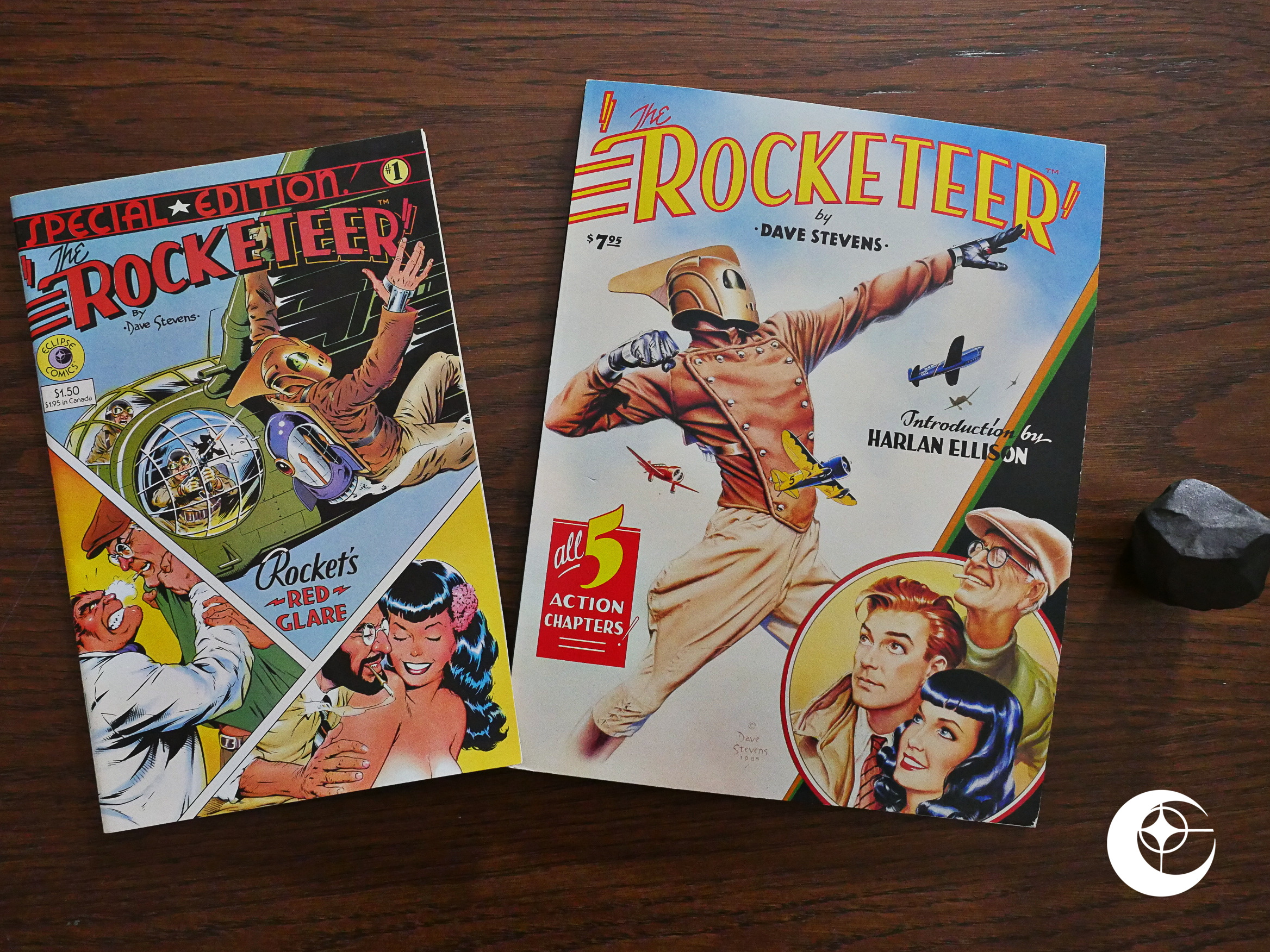

Axel Pressbutton (1984) #1-6 The Rocketeer Special Edition (1984) #1

The Rocketeer Special Edition (1984) #1 Siegel and Shuster: Dateline 1930s (1984) #1-2

Siegel and Shuster: Dateline 1930s (1984) #1-2 Somerset Holmes (1984) #5-6

Somerset Holmes (1984) #5-6 Sun-Runners (1984) #4-7

Sun-Runners (1984) #4-7 Strange Days (1984) #1-3

Strange Days (1984) #1-3 Berni Wrightson, Master of the Macabre (1984) #5

Berni Wrightson, Master of the Macabre (1984) #5 Twisted Tales (1984) #9-10

Twisted Tales (1984) #9-10 The Masked Man (1984) #1-12

The Masked Man (1984) #1-12 Doc Stearn…Mr. Monster (1985) #1-10

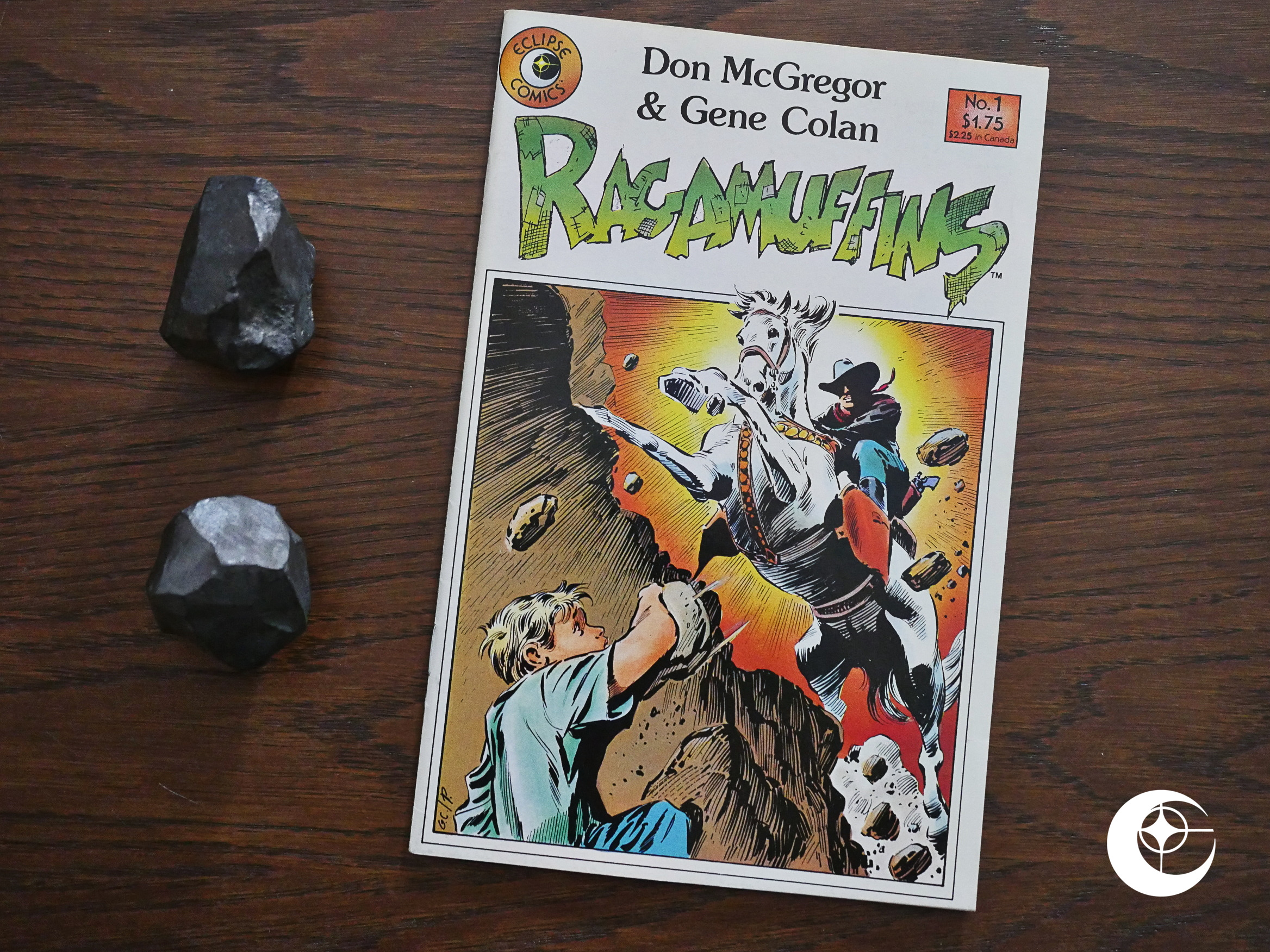

Doc Stearn…Mr. Monster (1985) #1-10 Ragamuffins (1985) #1

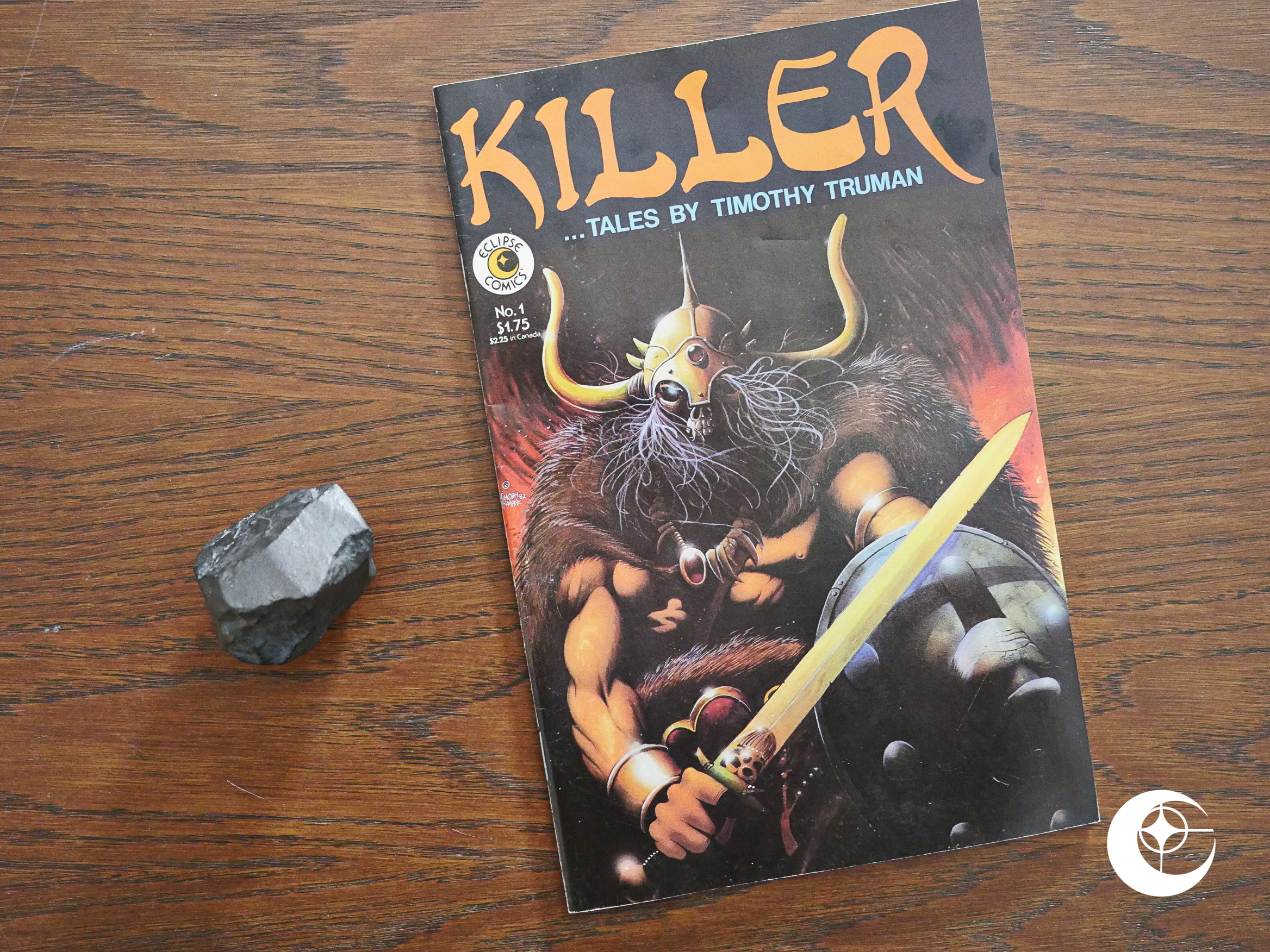

Ragamuffins (1985) #1 Killer… Tales by Timothy Truman (1985) #1

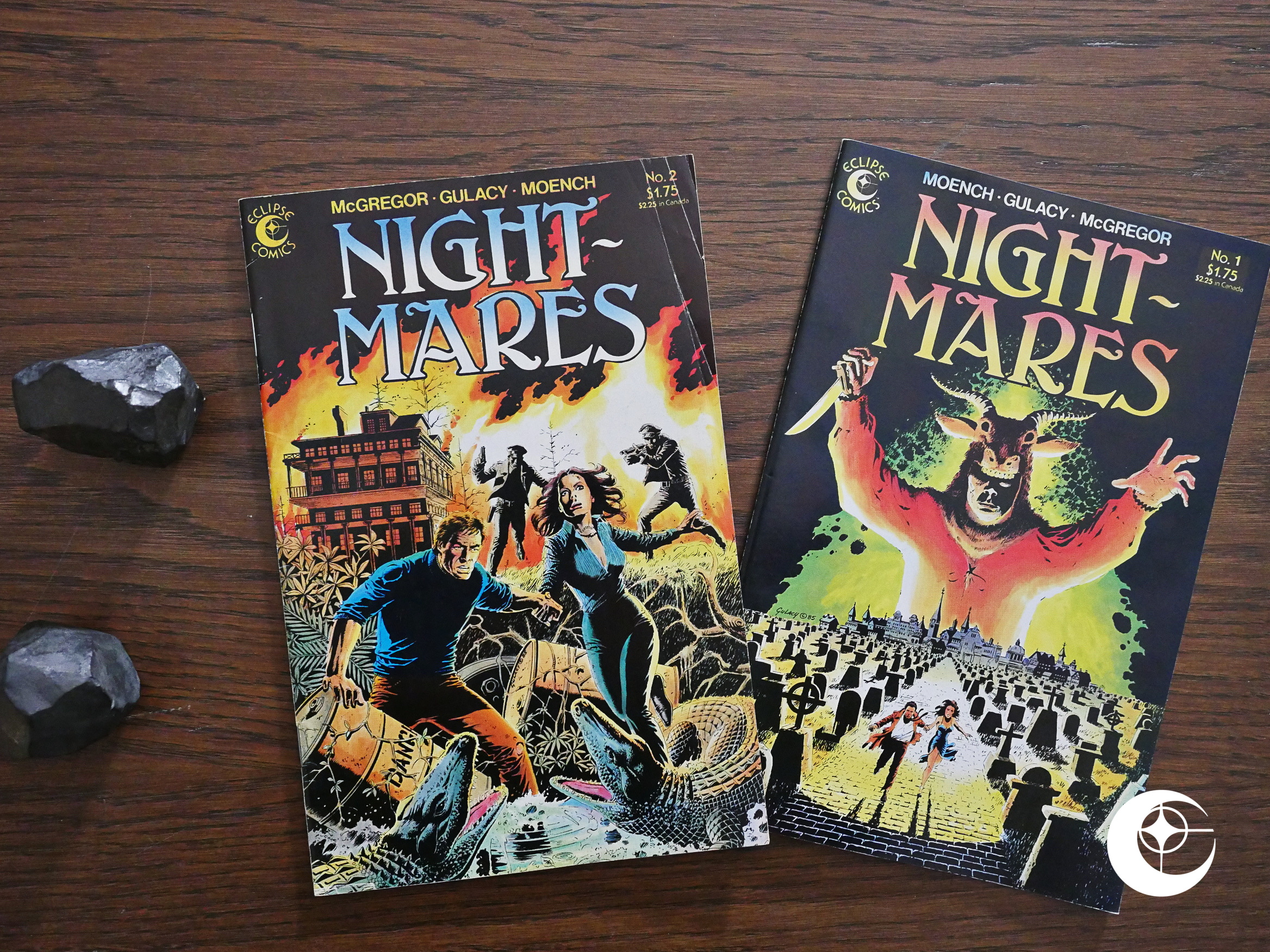

Killer… Tales by Timothy Truman (1985) #1 Nightmares (1985) #1-2

Nightmares (1985) #1-2 Alien Encounters (1985) #1-14

Alien Encounters (1985) #1-14 John Bolton’s Halls of Horror (1985) #1-2

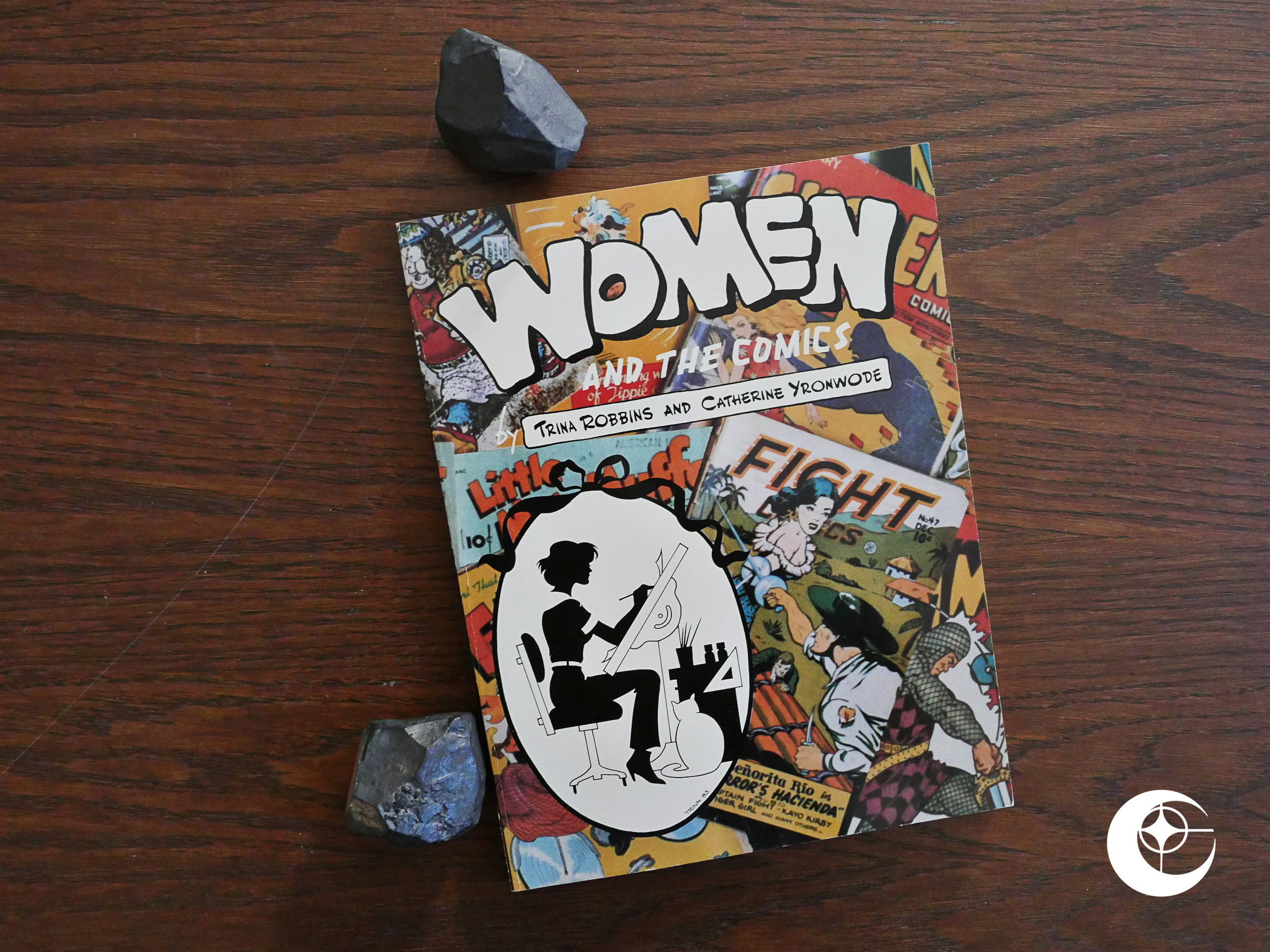

John Bolton’s Halls of Horror (1985) #1-2 Women and the Comics (1985) #1

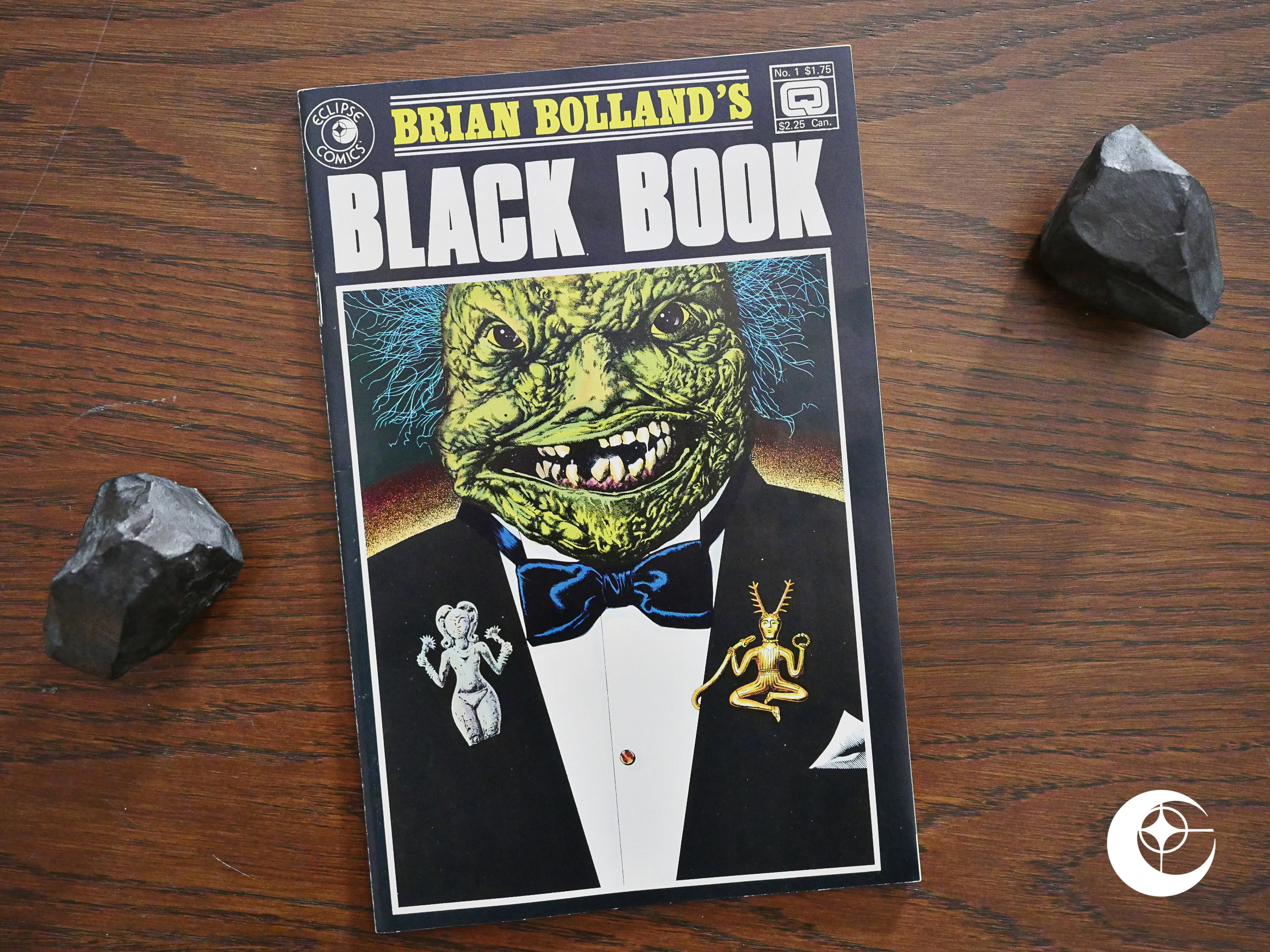

Women and the Comics (1985) #1 Brian Bolland’s Black Book (1985) #1

Brian Bolland’s Black Book (1985) #1 Tales of Terror (1985) #1-13

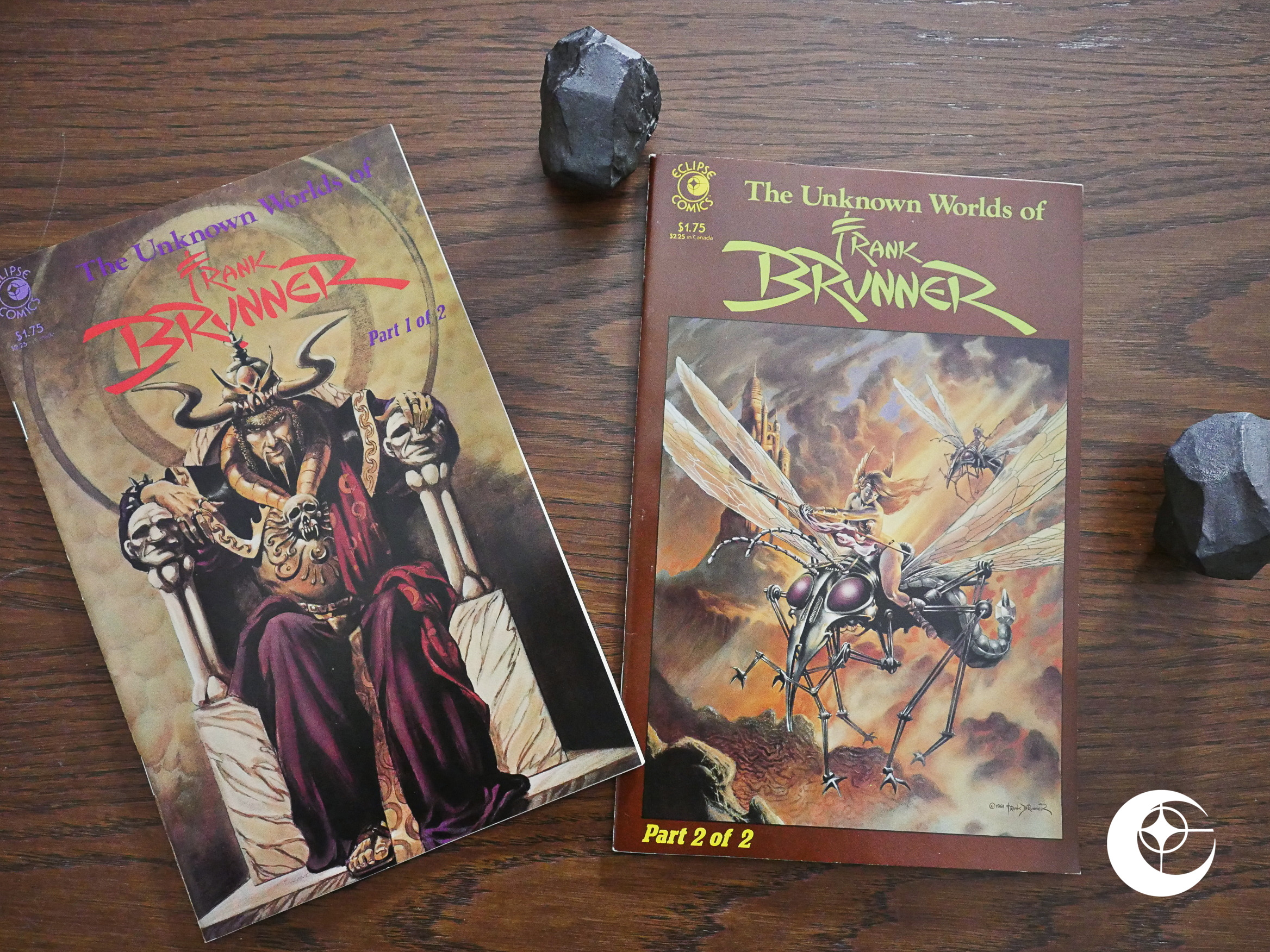

Tales of Terror (1985) #1-13 The Unknown Worlds of Frank Brunner (1985) #1-2

The Unknown Worlds of Frank Brunner (1985) #1-2 Miracleman (1985) #1-24

Miracleman (1985) #1-24 Bedlam (1985) #1-2

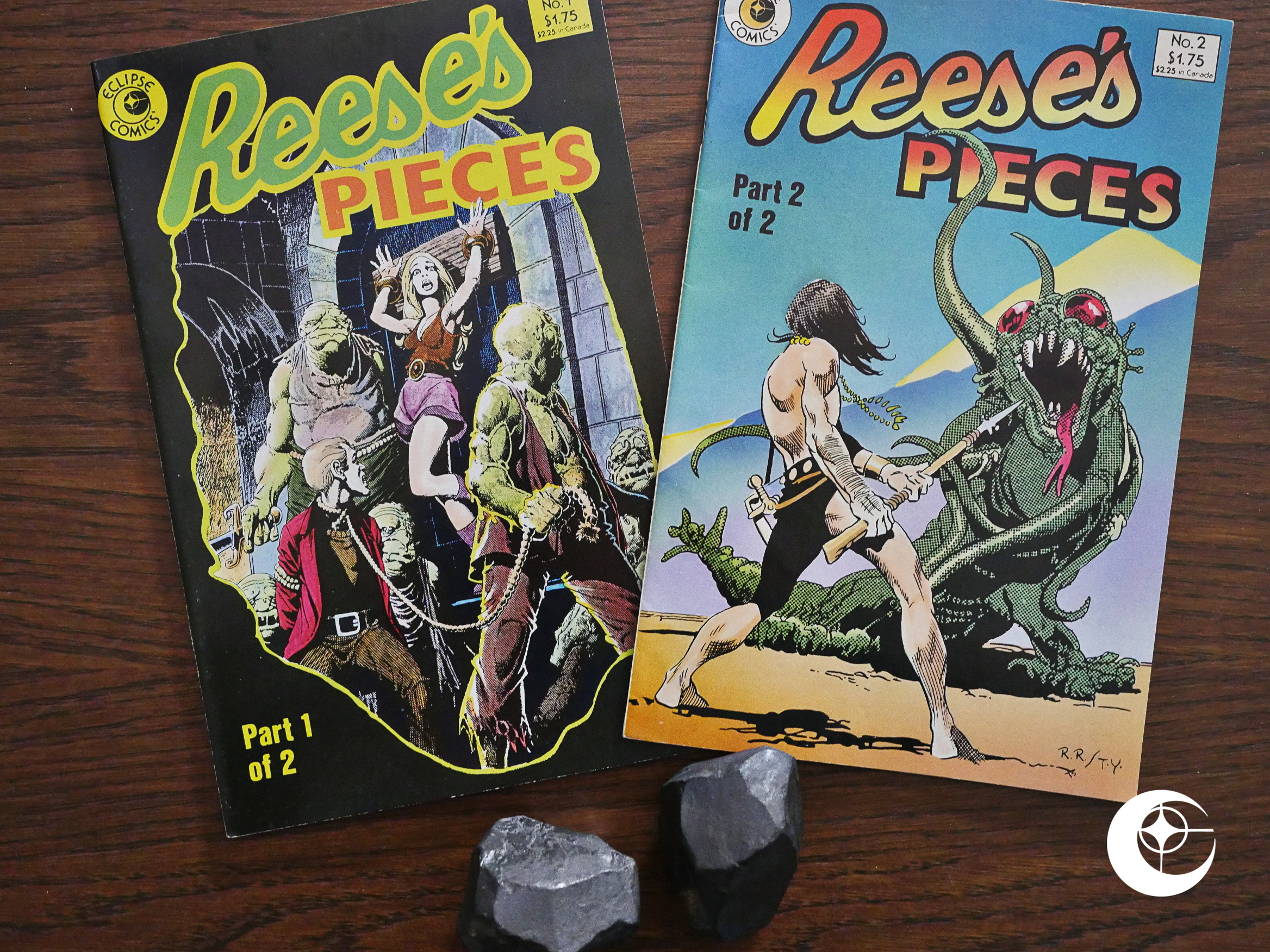

Bedlam (1985) #1-2 Reese’s Pieces (1985) #1-2

Reese’s Pieces (1985) #1-2 Scout (1985) #1-24

Scout (1985) #1-24 Seduction of the Innocent 3-D (1985) #1-2

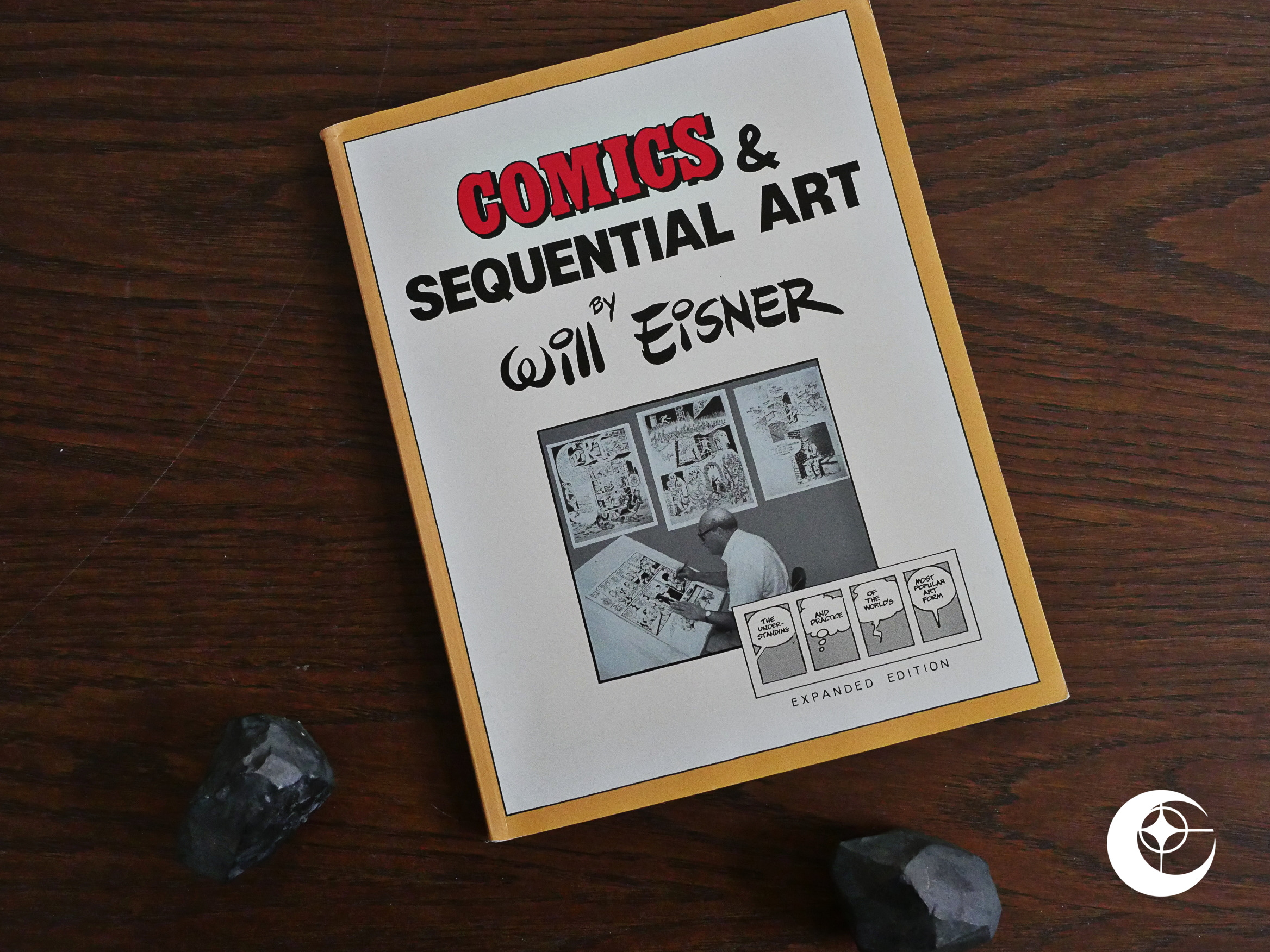

Seduction of the Innocent 3-D (1985) #1-2 Comics & Sequential Art (1985) #1

Comics & Sequential Art (1985) #1 Tales of the Beanworld (1985) #1-21

Tales of the Beanworld (1985) #1-21 Army Surplus Komikz Featuring: Cutey Bunny (1985) #5

Army Surplus Komikz Featuring: Cutey Bunny (1985) #5 The Official Teen Titans Index (1985) #1-5

The Official Teen Titans Index (1985) #1-5 Airboy (1986) #1-50

Airboy (1986) #1-50 Adolescent Radioactive Black Belt Hamsters (1986) #1-9

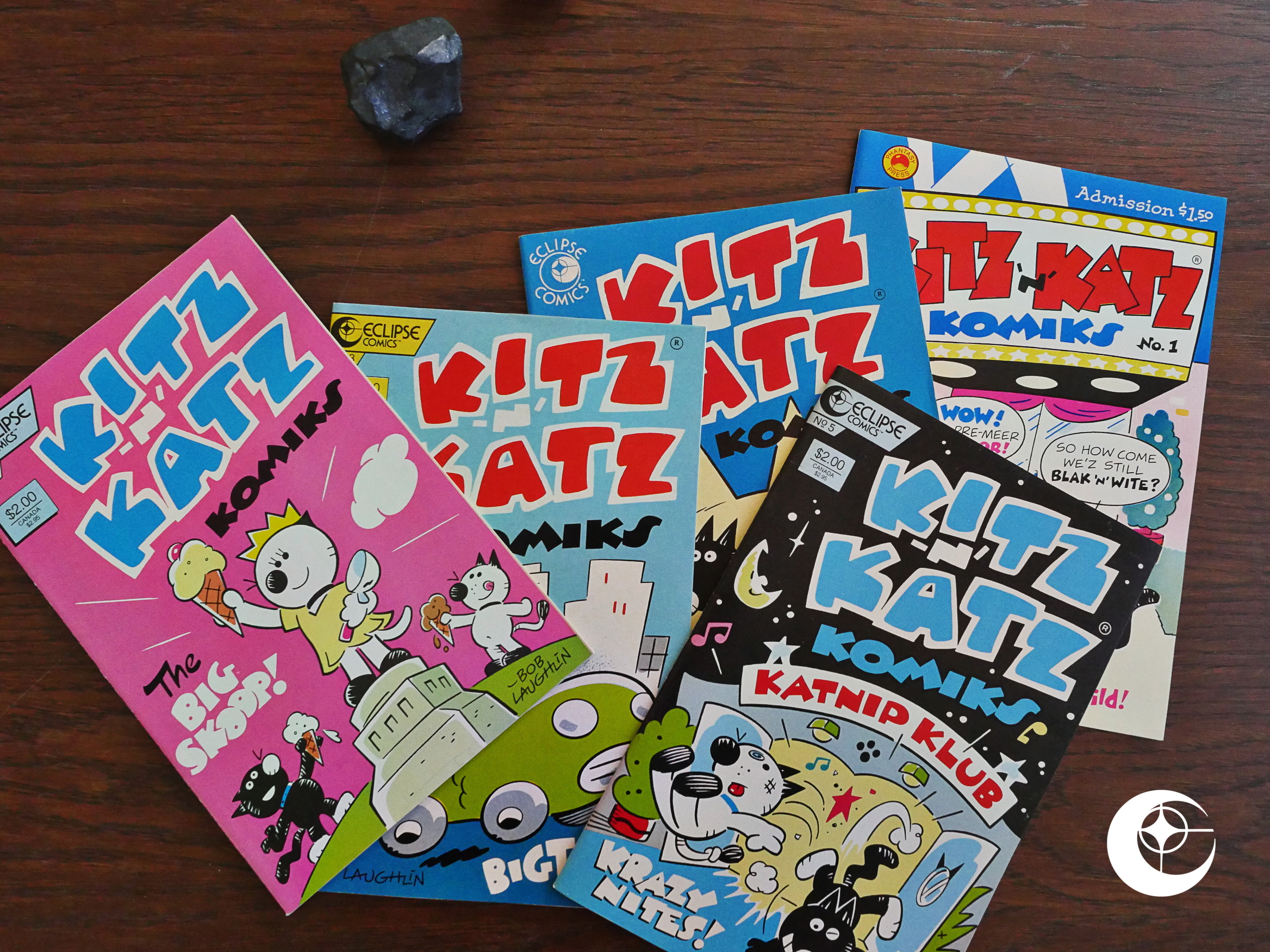

Adolescent Radioactive Black Belt Hamsters (1986) #1-9 Kitz ‘n’ Katz Komiks (1986) #1-4

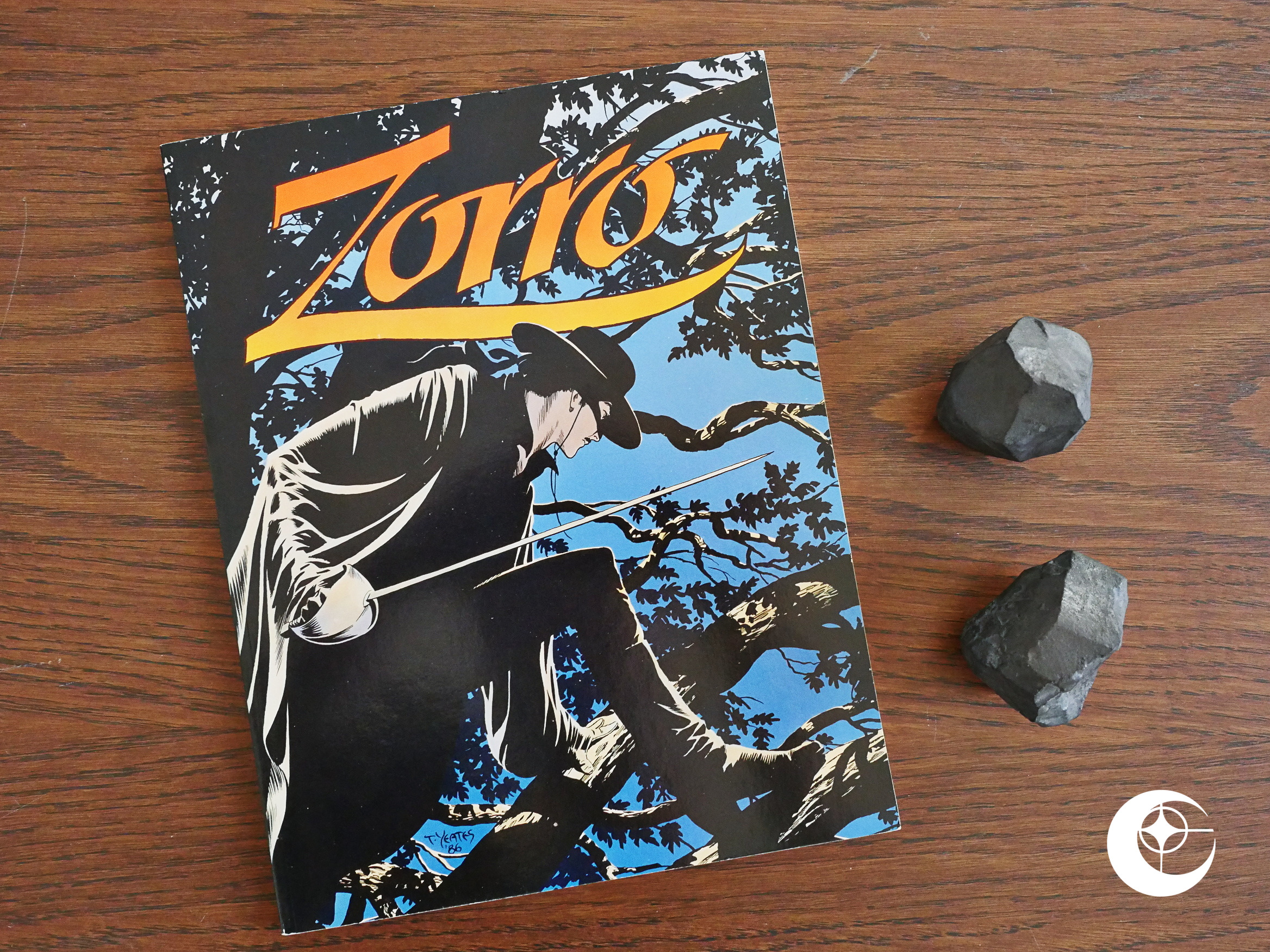

Kitz ‘n’ Katz Komiks (1986) #1-4 Zorro in Old California (1986) #1

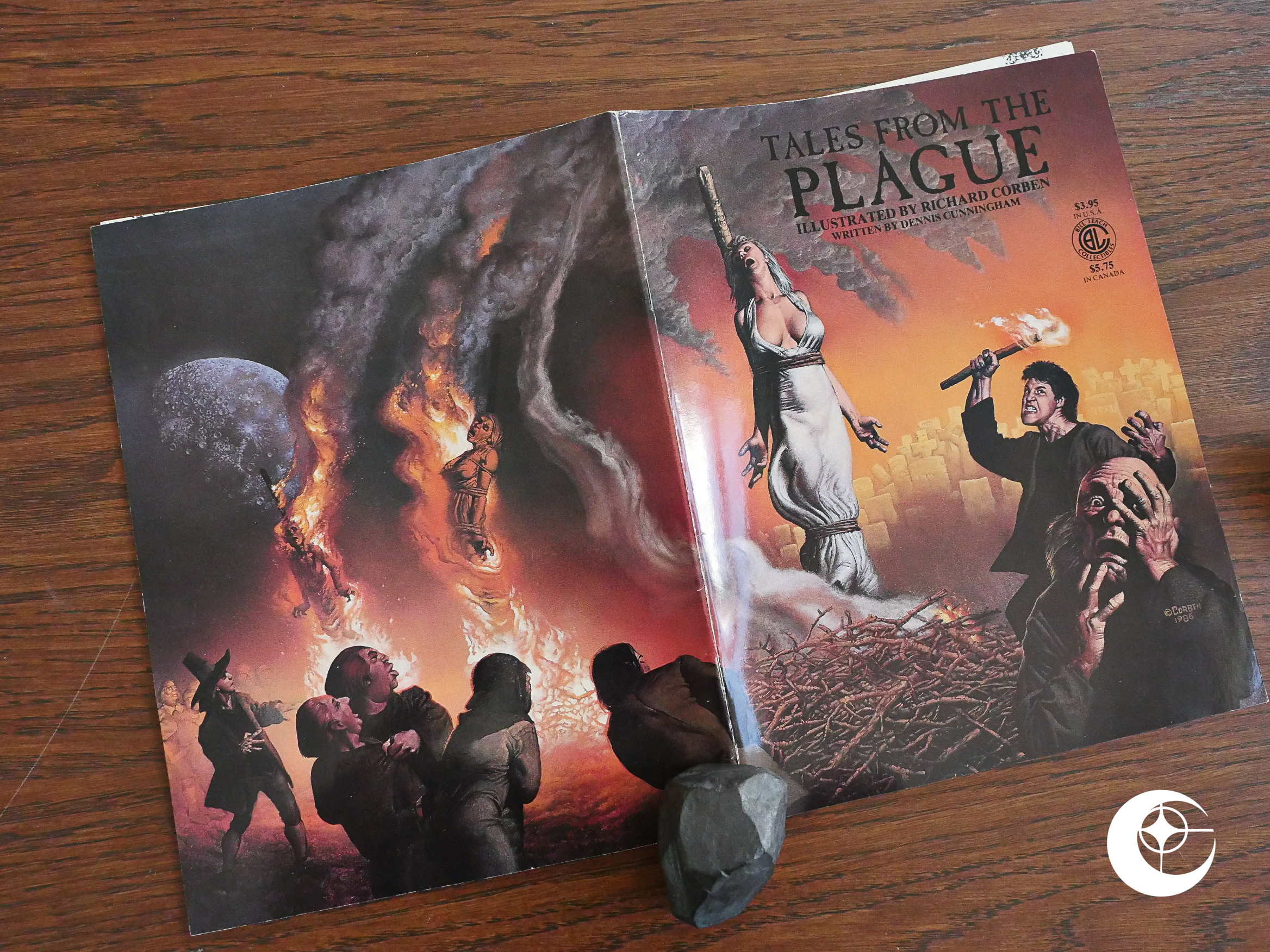

Zorro in Old California (1986) #1 Tales from the Plague (1986) #1

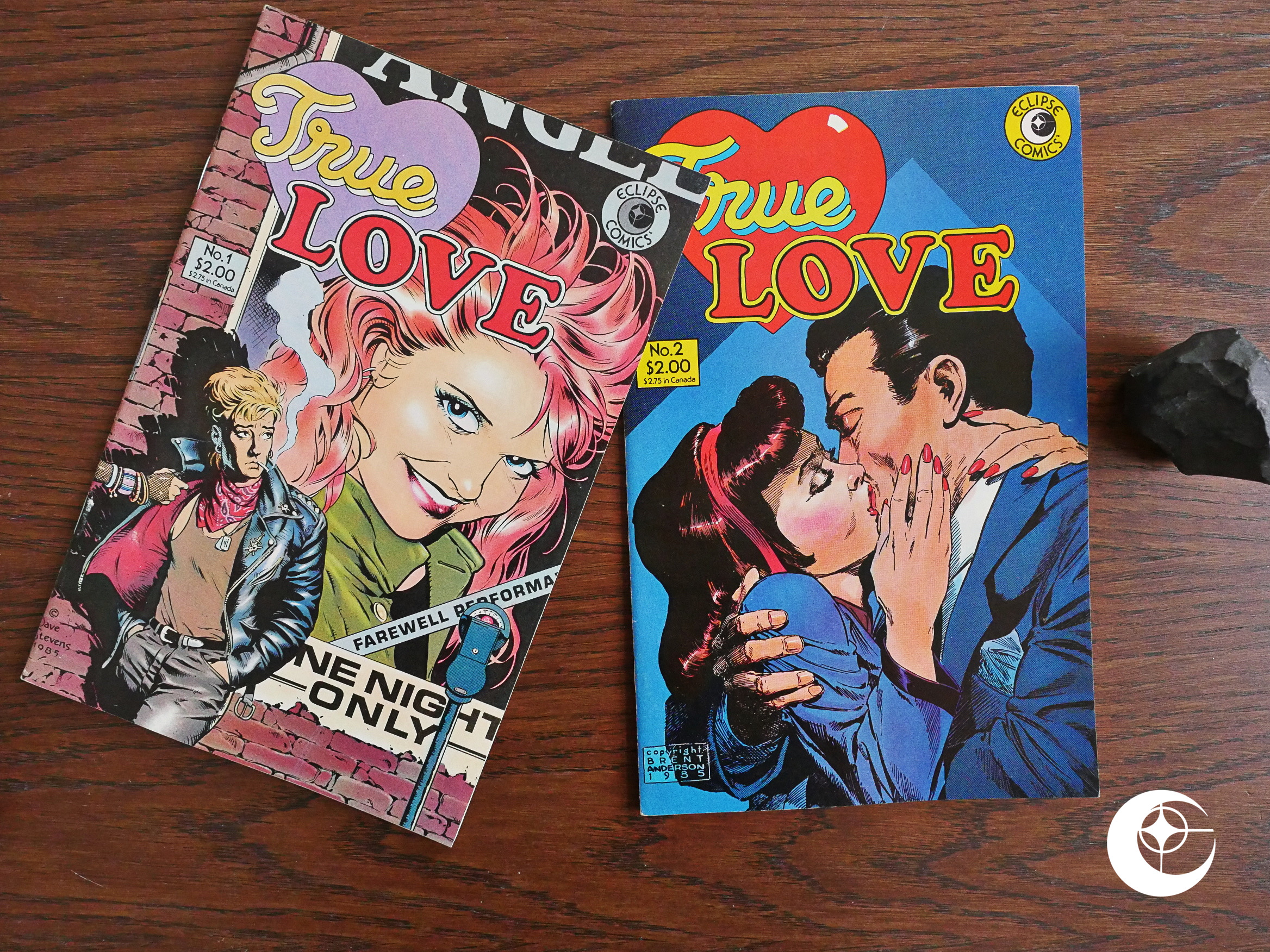

Tales from the Plague (1986) #1 True Love (1986) #1-2

True Love (1986) #1-2 World of Wood (1986) #1-5

World of Wood (1986) #1-5 Champions (1986) #1-6

Champions (1986) #1-6 The New Wave (1986) #1-13

The New Wave (1986) #1-13 Espers (1986) #1-5

Espers (1986) #1-5 The Spiral Path (1986) #1-2

The Spiral Path (1986) #1-2 Tor 3-D (1986) #1-2

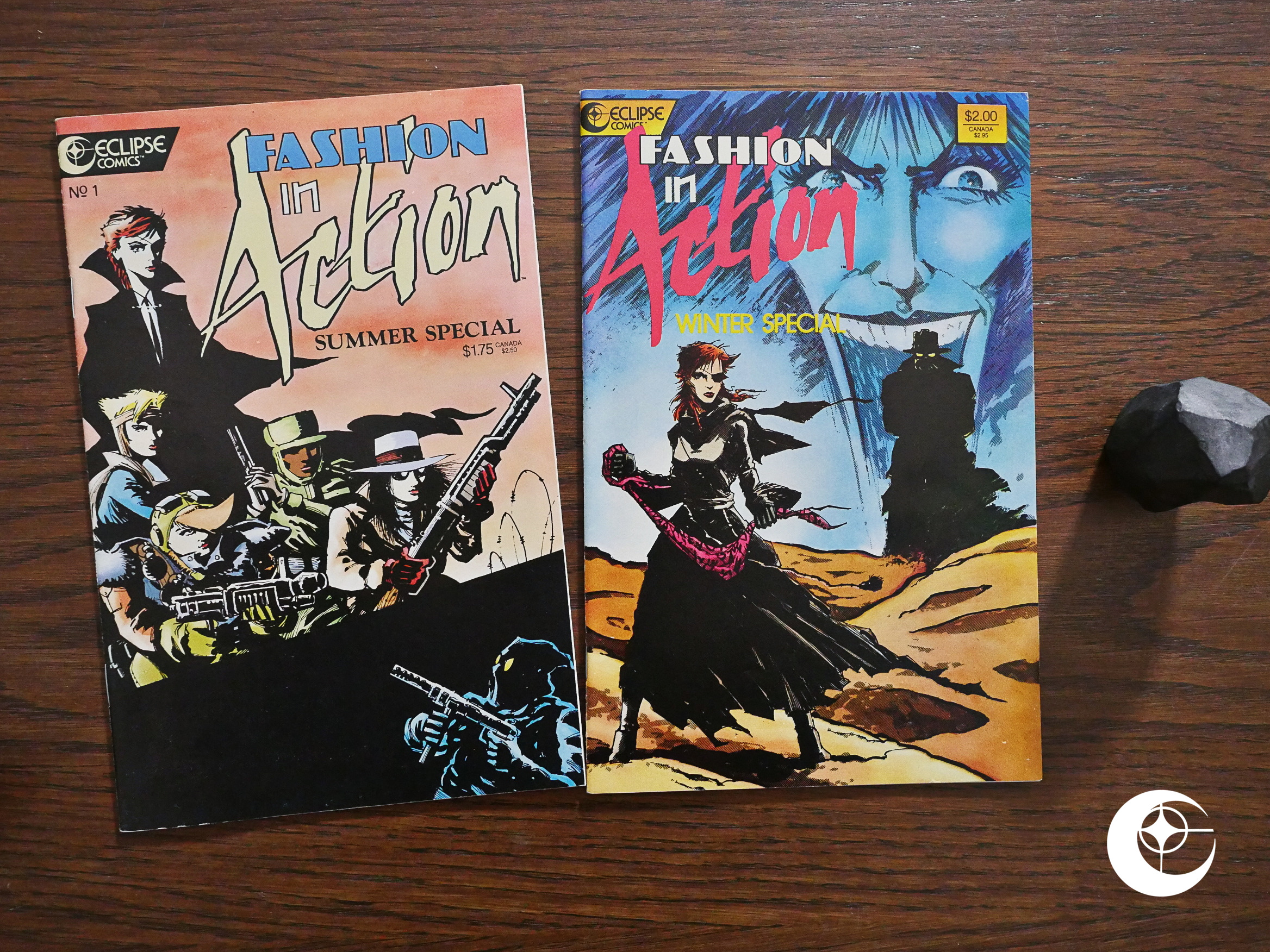

Tor 3-D (1986) #1-2 Fashion in Action Summer Special (1986) #1

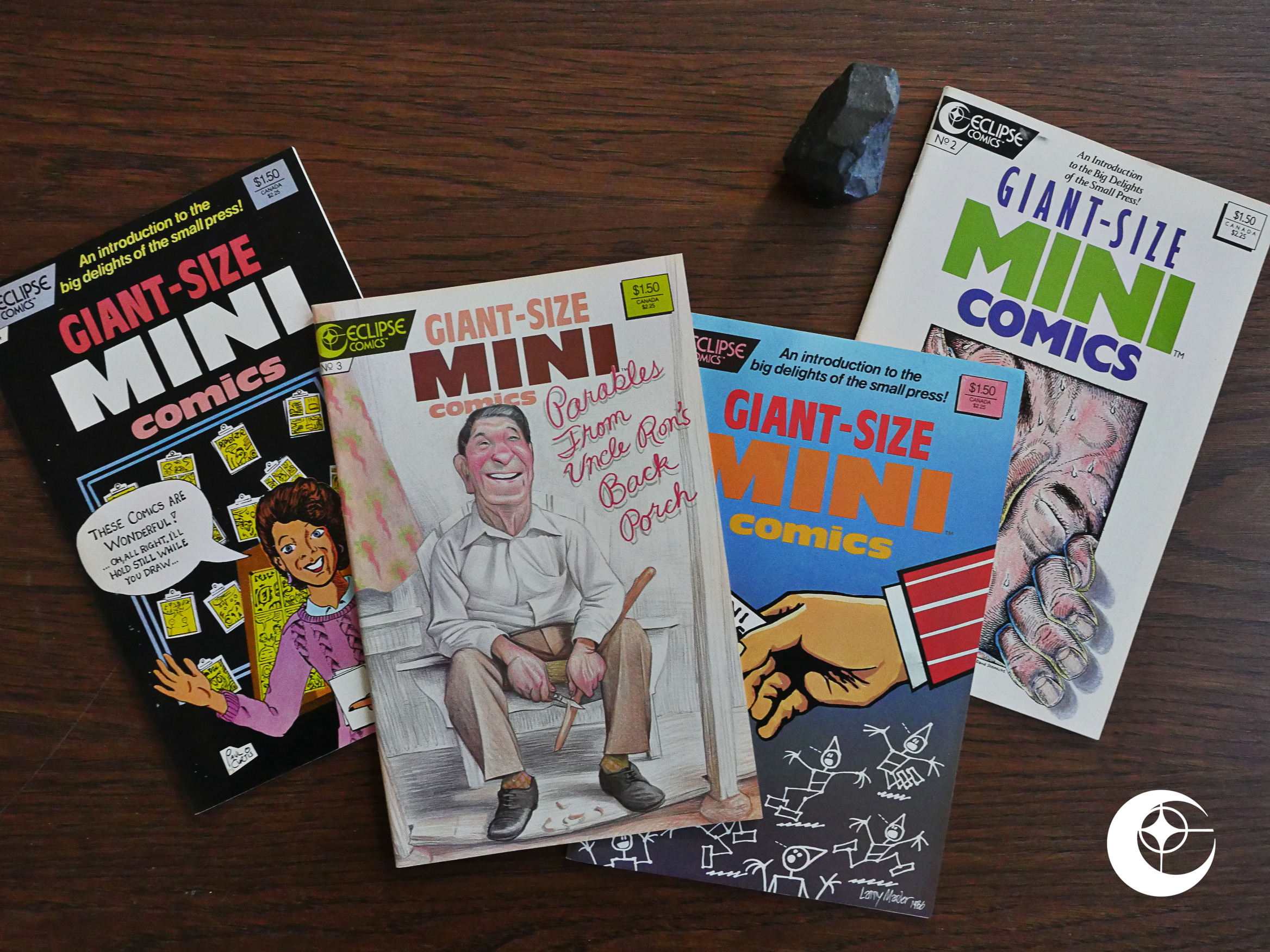

Fashion in Action Summer Special (1986) #1 Giant-Size Mini Comics (1986) #1-4

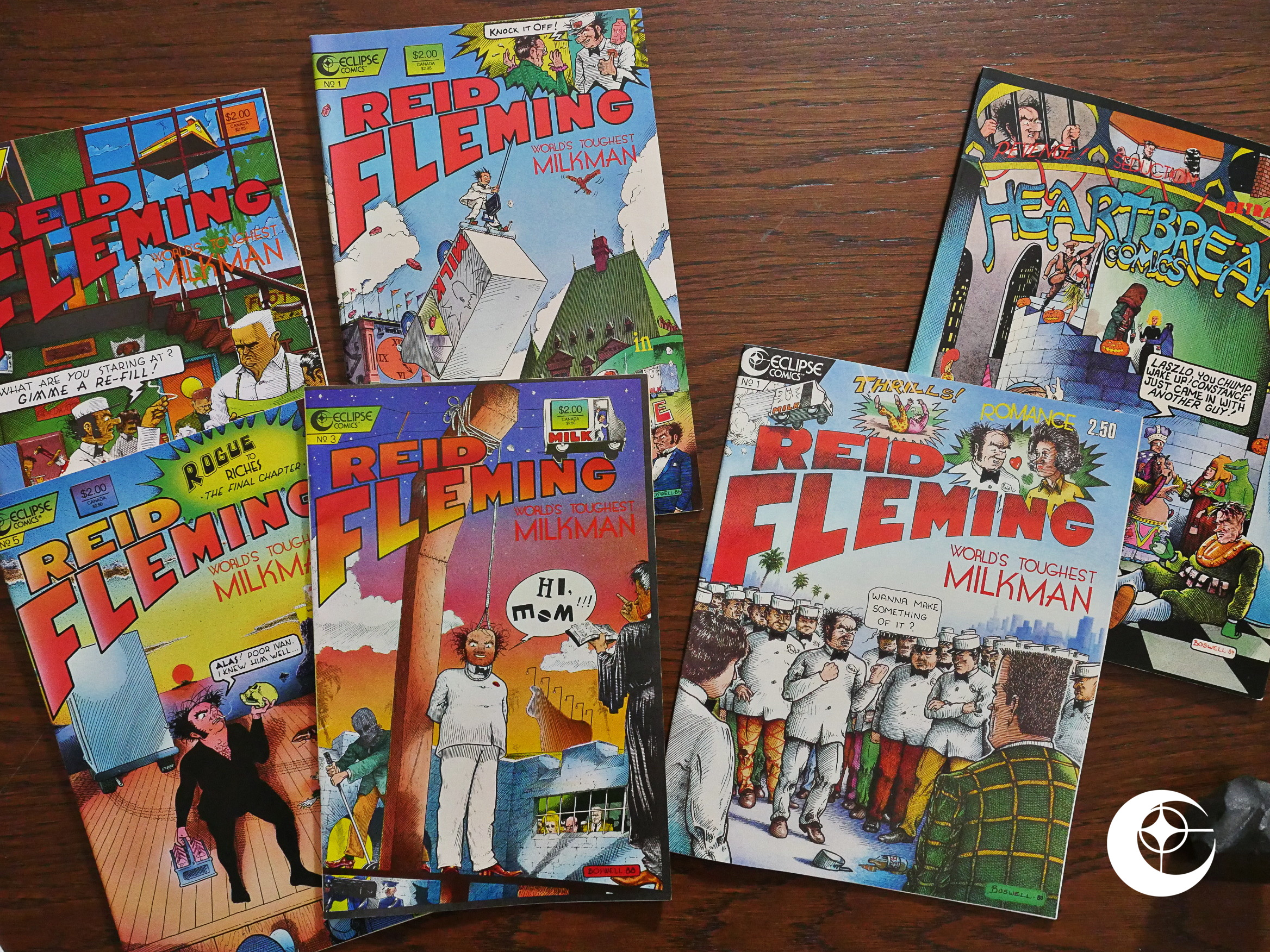

Giant-Size Mini Comics (1986) #1-4 Reid Fleming, World’s Toughest Milkman (1986) #1

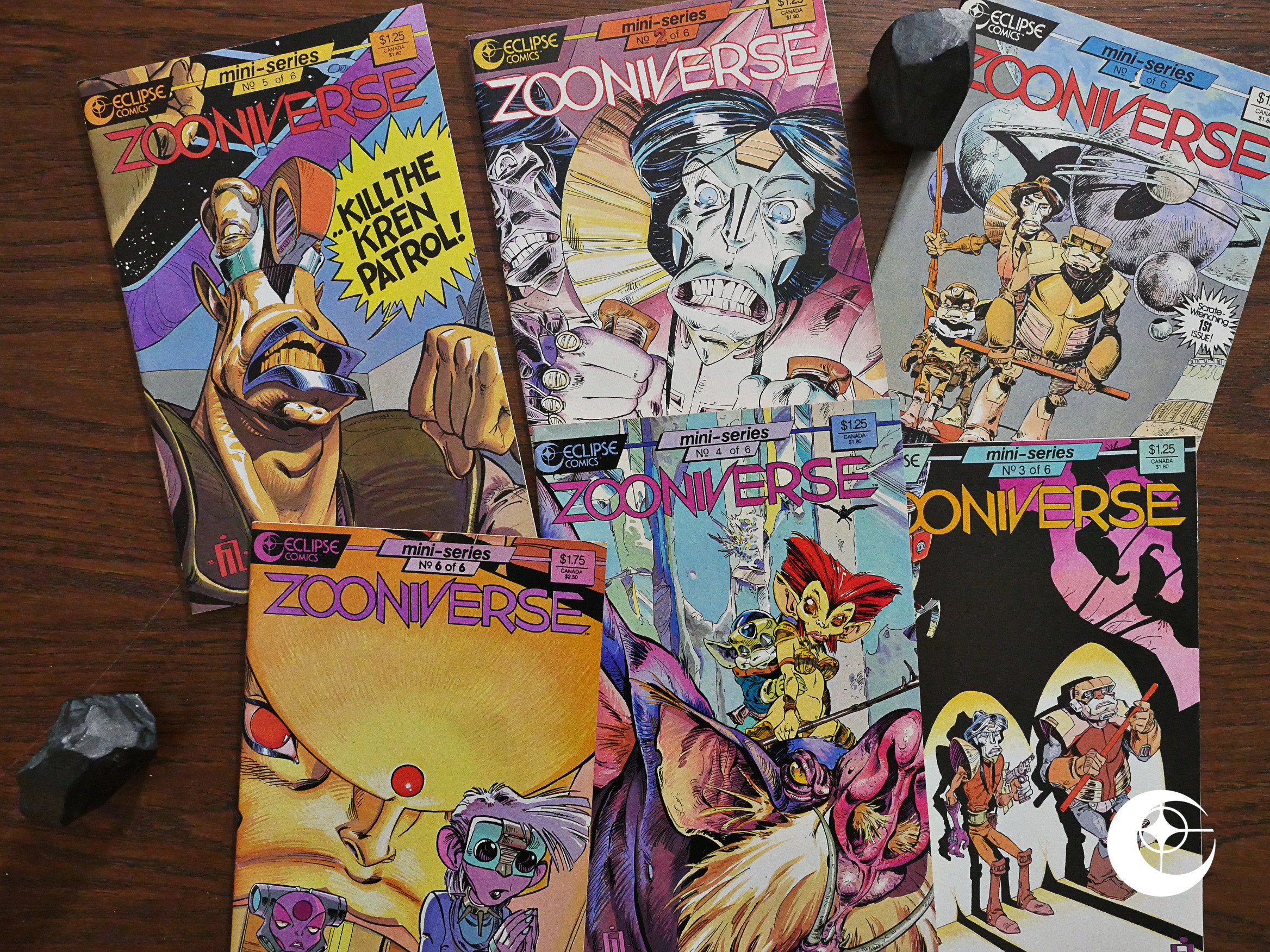

Reid Fleming, World’s Toughest Milkman (1986) #1 Zooniverse (1986) #1-6

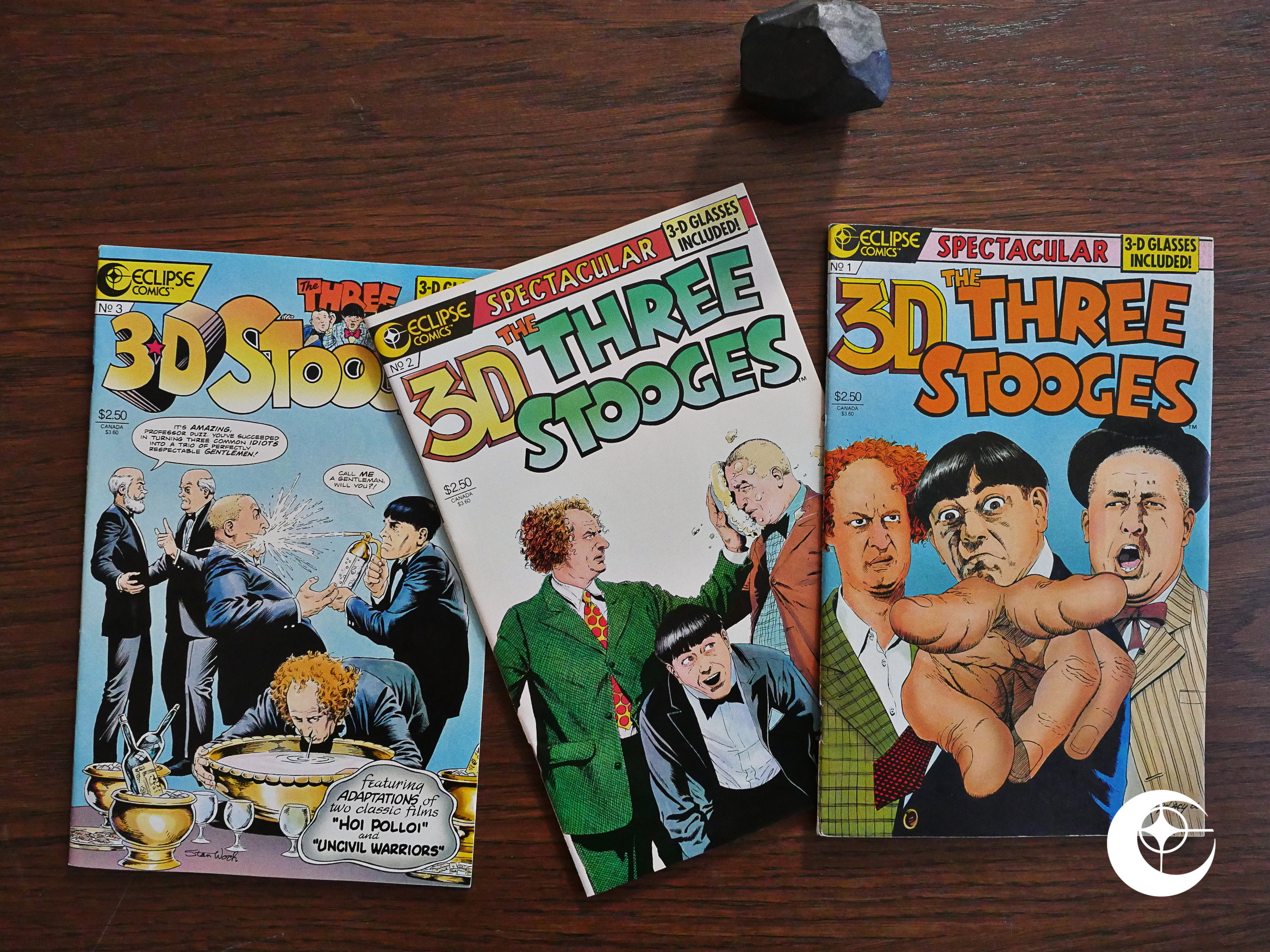

Zooniverse (1986) #1-6 Three-D Three Stooges (1986) #1-3

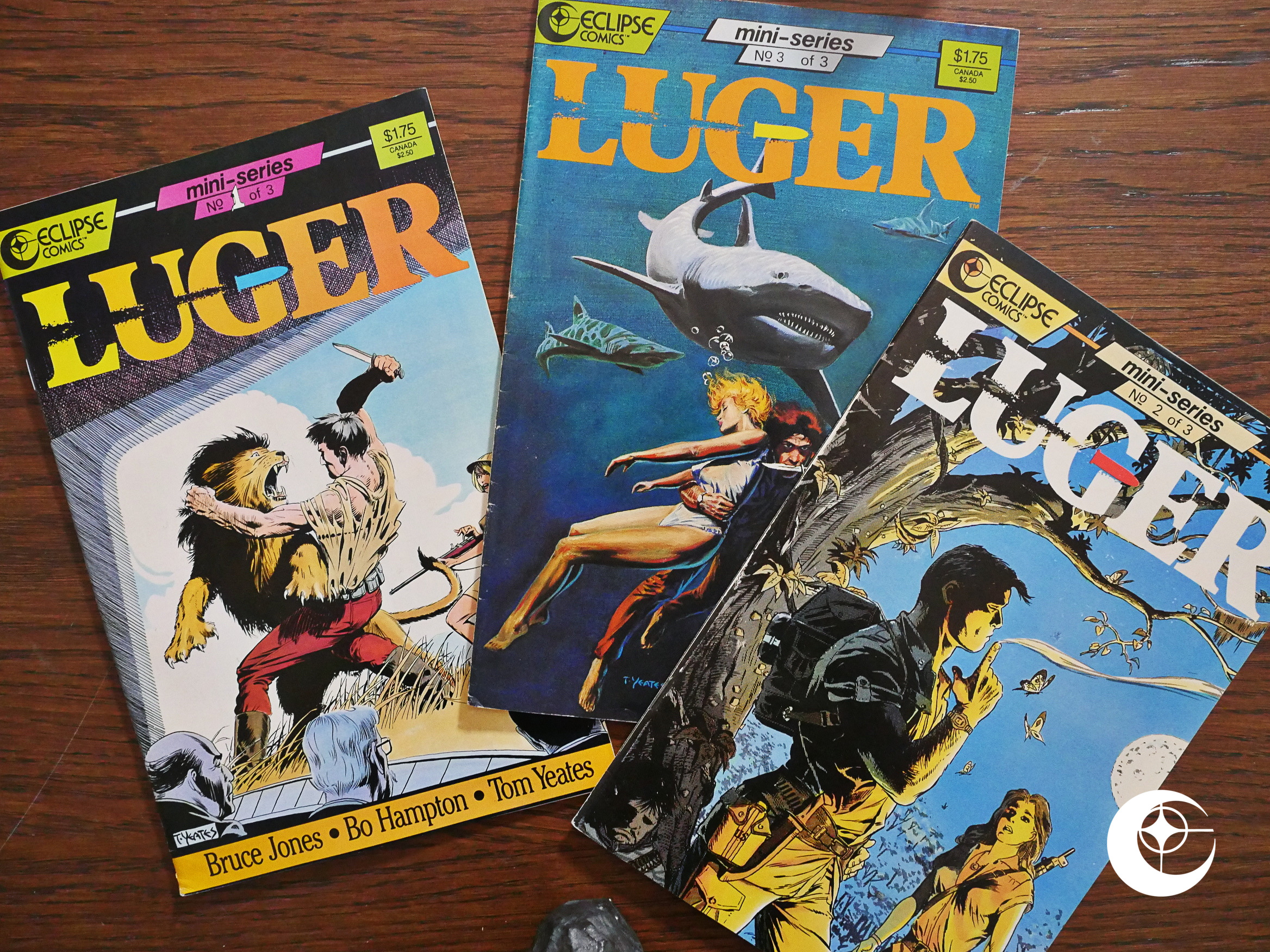

Three-D Three Stooges (1986) #1-3 Luger (1986) #1-3

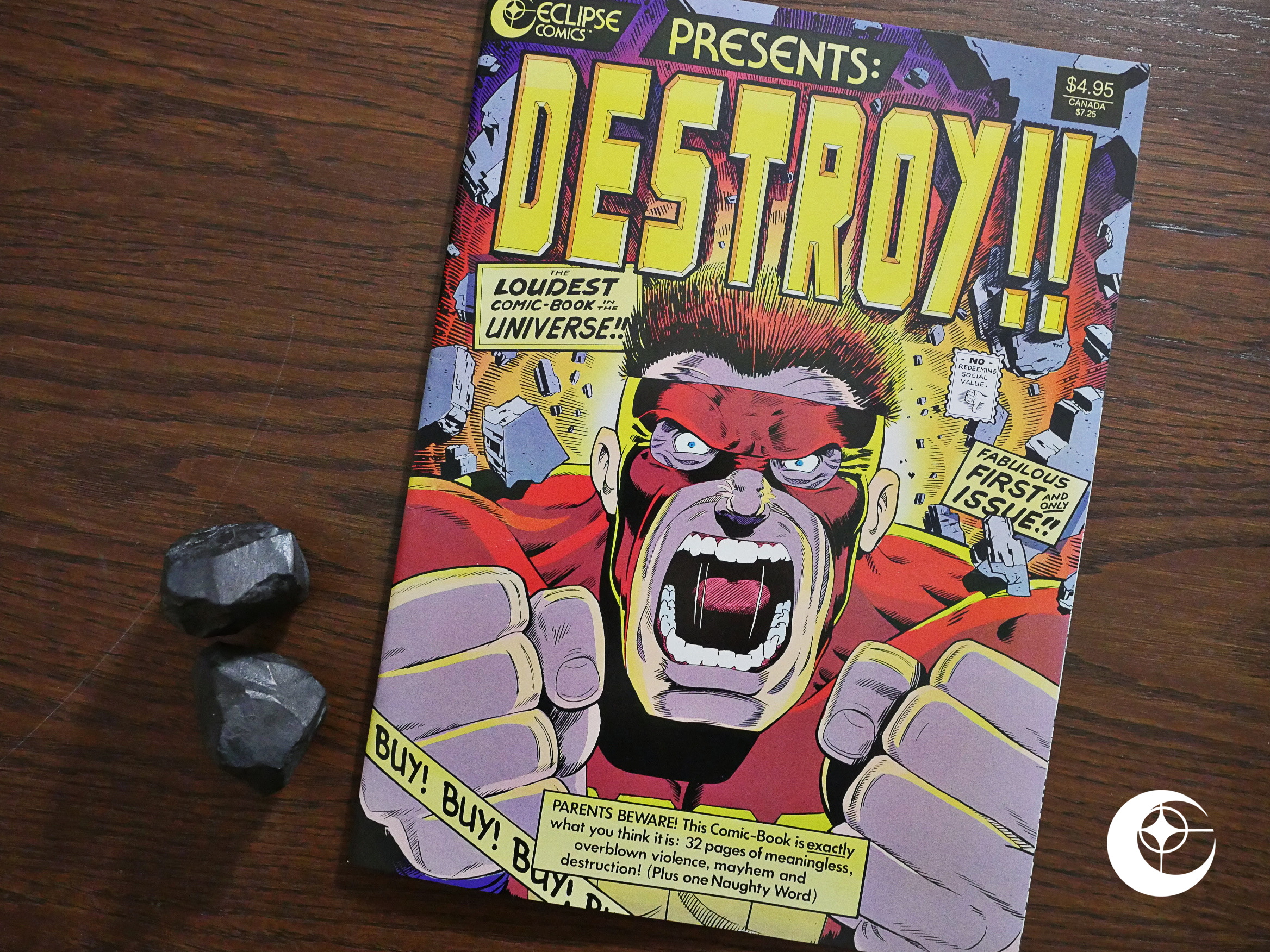

Luger (1986) #1-3 Destroy!! (1986) #1

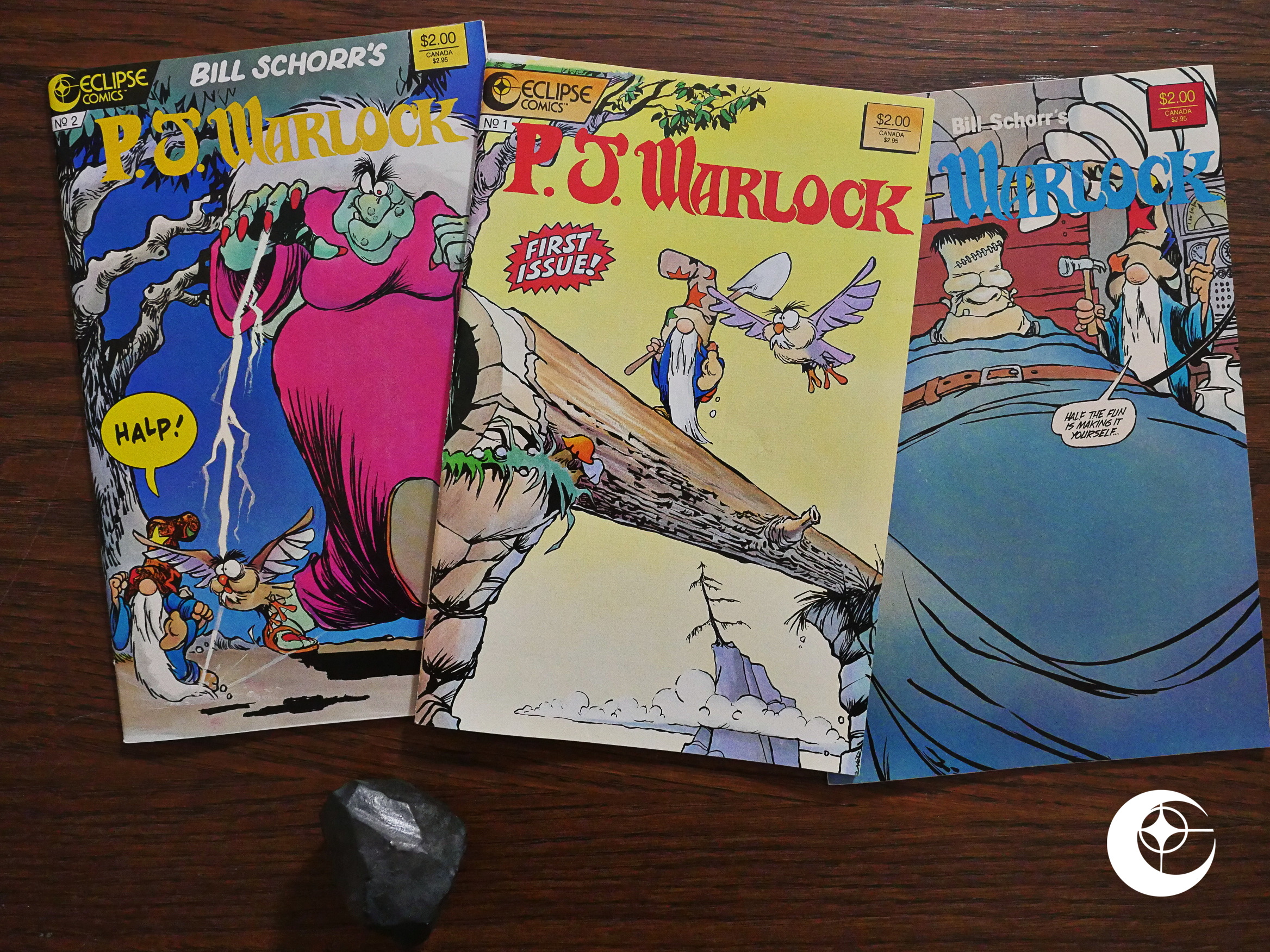

Destroy!! (1986) #1 P.J. Warlock (1986) #1-3

P.J. Warlock (1986) #1-3 Villains and Vigilantes (1986) #1-4

Villains and Vigilantes (1986) #1-4 Portia Prinz of the Glamazons (1986) #1-6

Portia Prinz of the Glamazons (1986) #1-6 The Dreamery (1986) #1-14

The Dreamery (1986) #1-14 Forgotten Horrors (1986) #1

Forgotten Horrors (1986) #1 Naive Inter-Dimensional Commando Koalas (1986) #1

Naive Inter-Dimensional Commando Koalas (1986) #1 Spaced (1986) #10-13

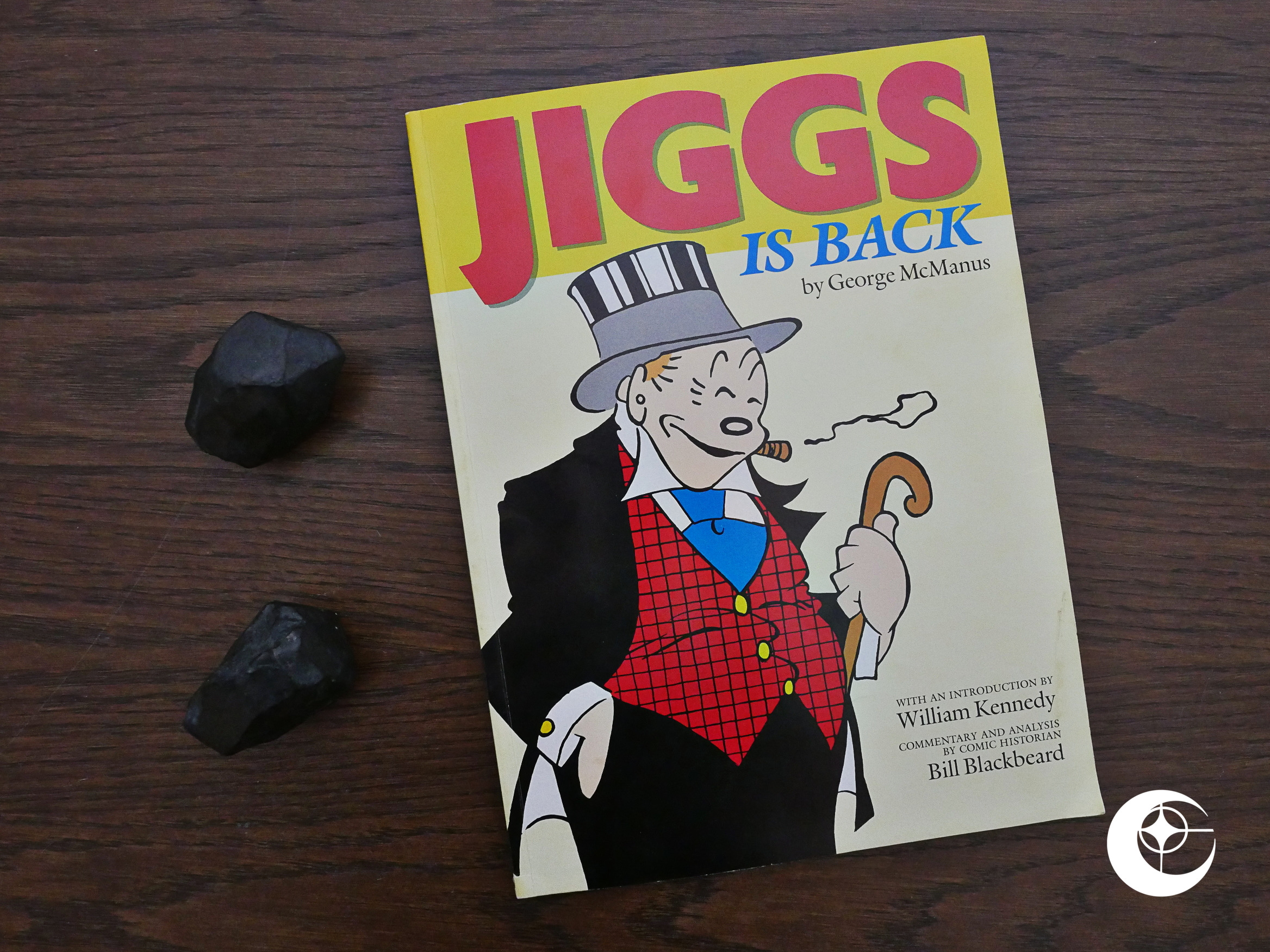

Spaced (1986) #10-13 Jiggs is Back (1986) #1

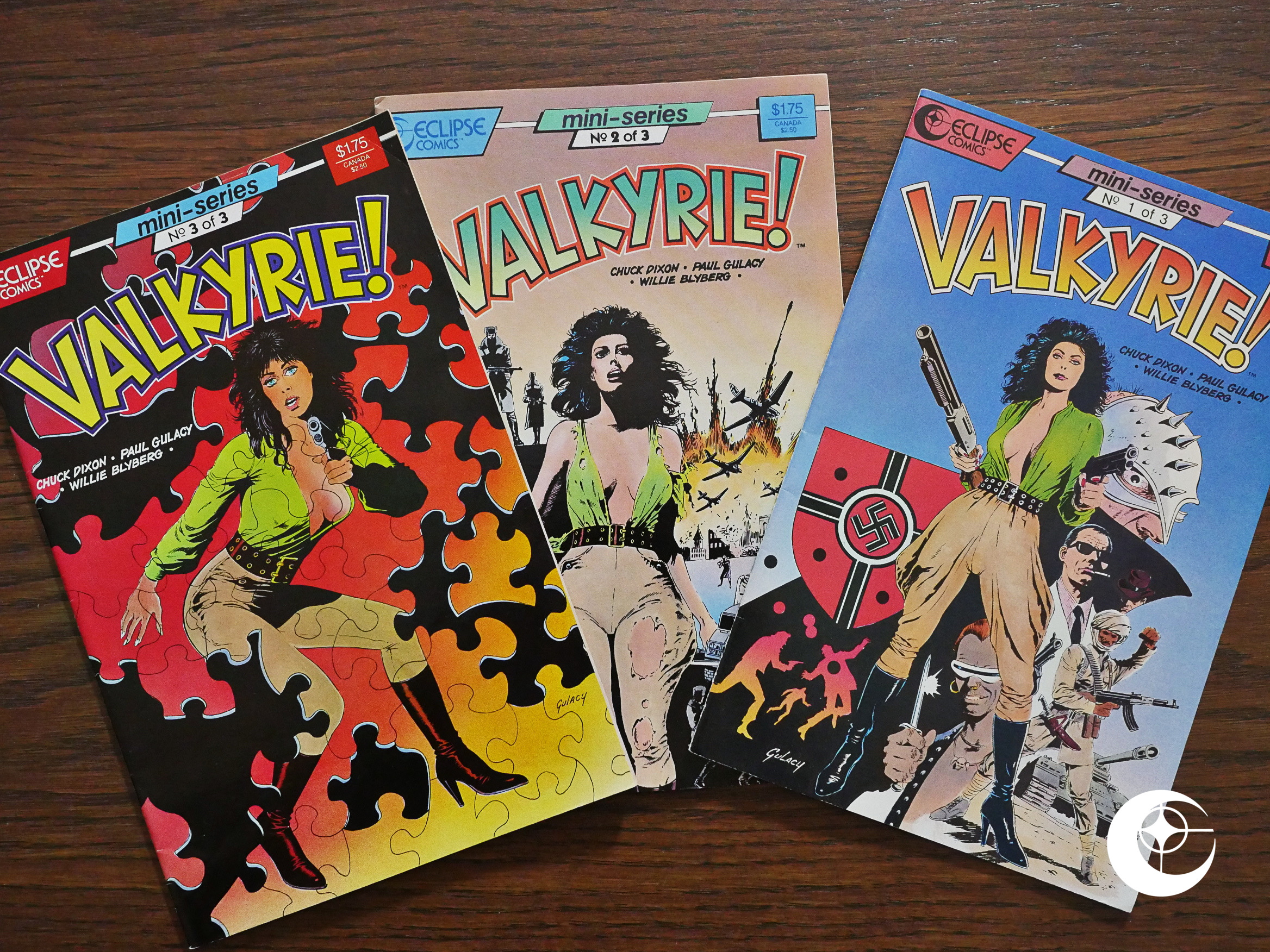

Jiggs is Back (1986) #1 Valkyrie! (1987) #1-3

Valkyrie! (1987) #1-3 Fusion (1987) #1-17

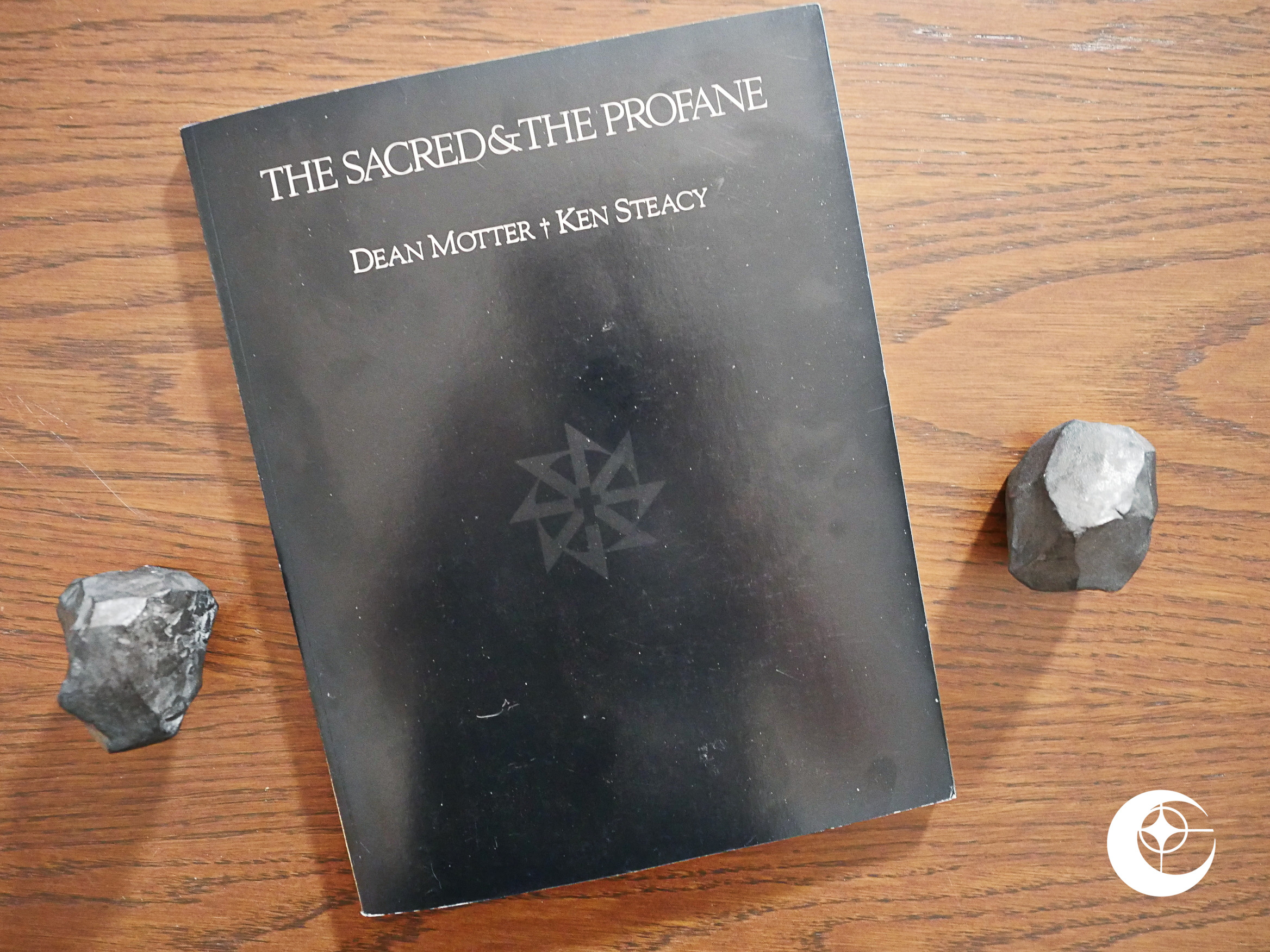

Fusion (1987) #1-17 The Sacred and the Profane (1987) #1

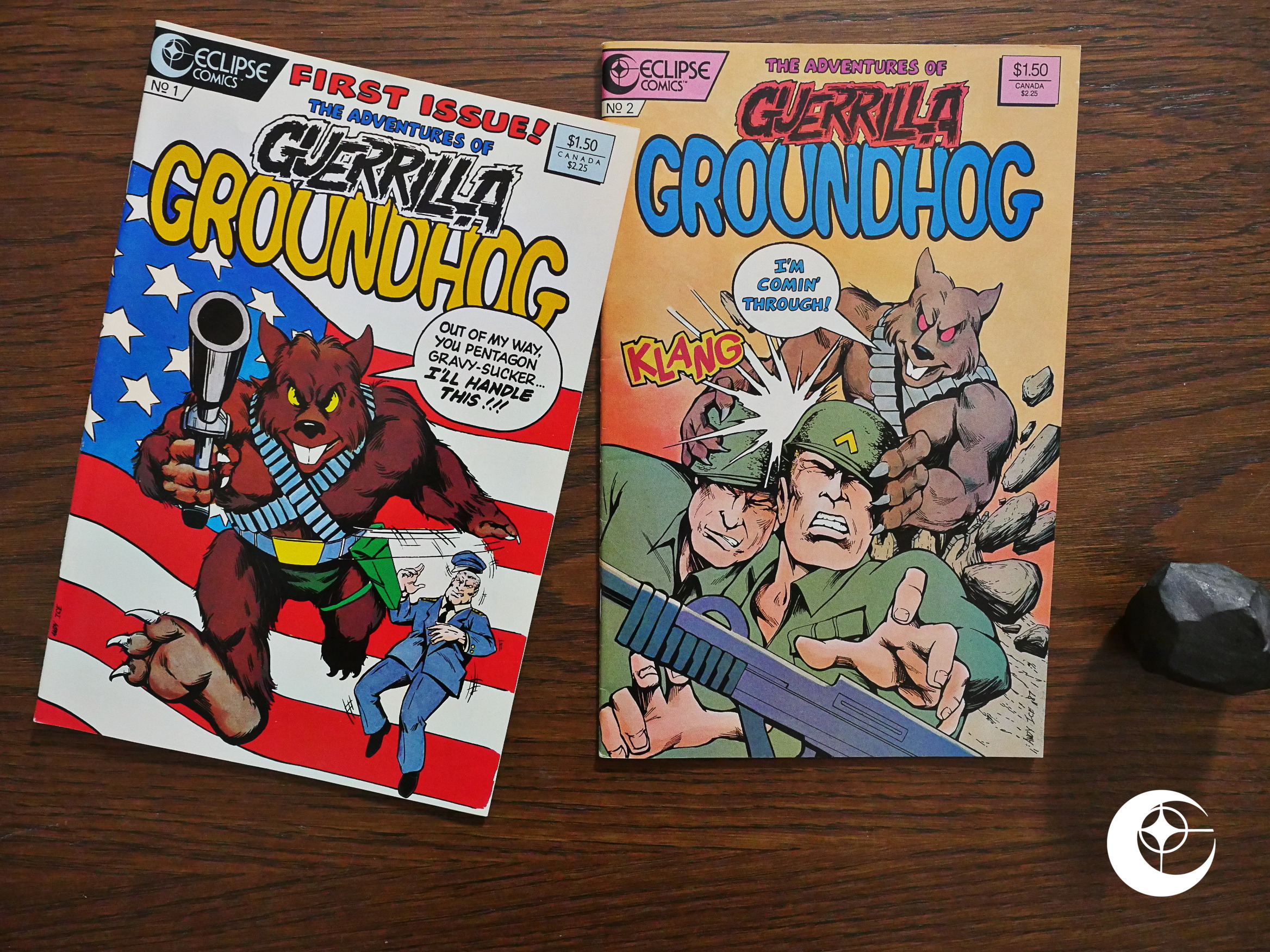

The Sacred and the Profane (1987) #1 Guerrilla Groundhog (1987) #1-2

Guerrilla Groundhog (1987) #1-2 Stig’s Inferno (1987) #6-7

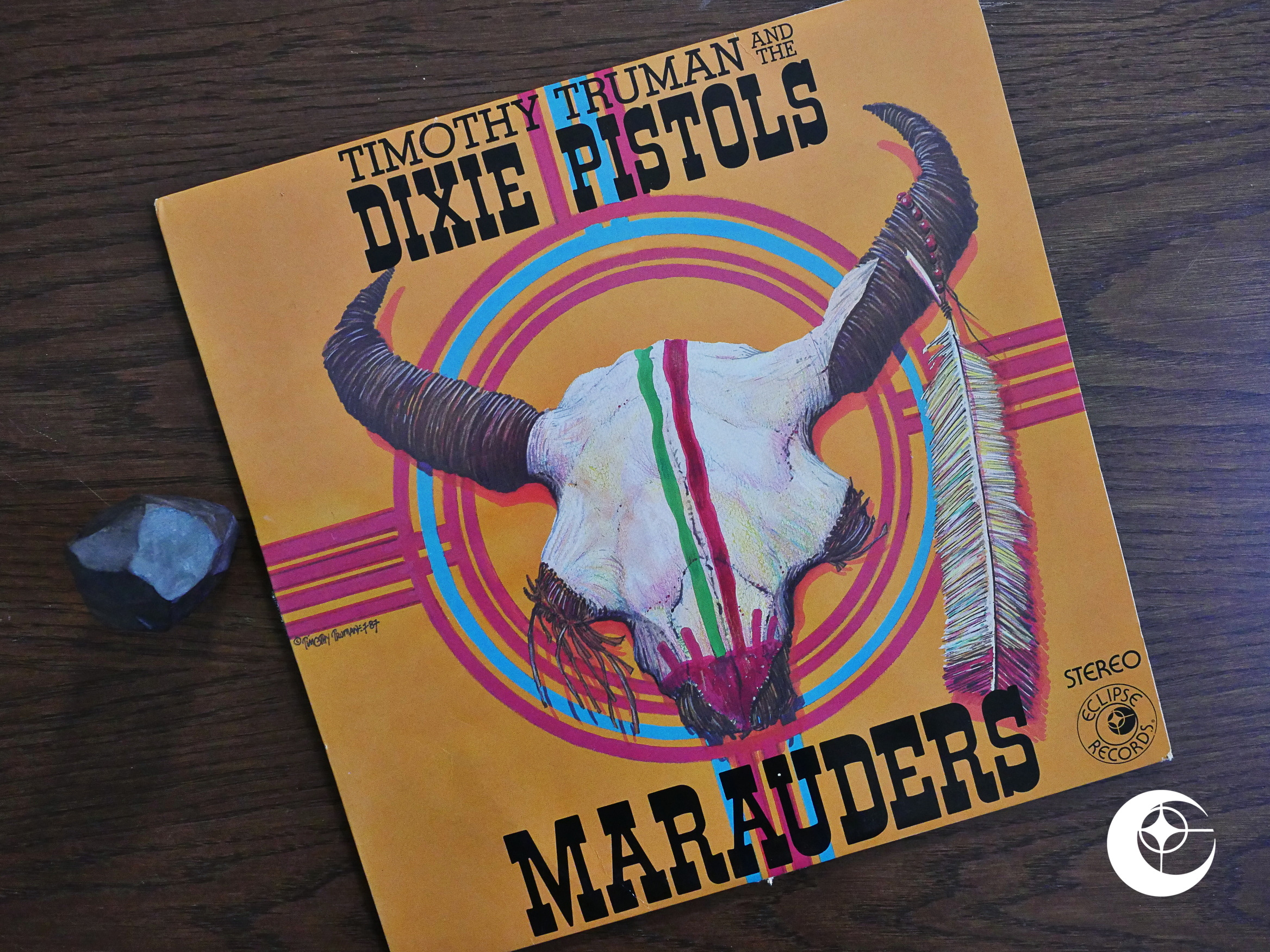

Stig’s Inferno (1987) #6-7 Marauders (1987)

Marauders (1987) Bullet Crow, Fowl of Fortune (1987) #1-2

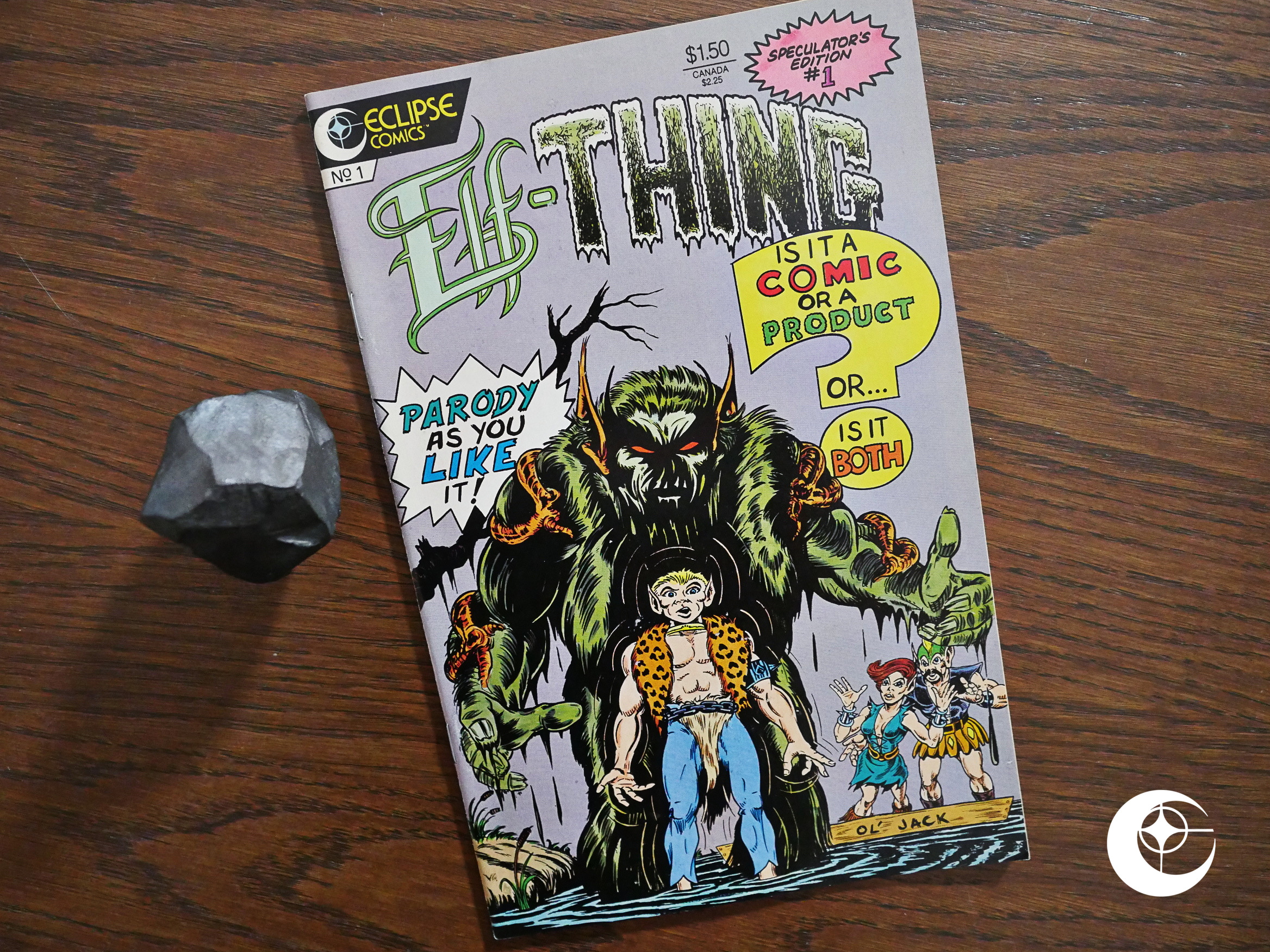

Bullet Crow, Fowl of Fortune (1987) #1-2 Elf-Thing (1987) #1

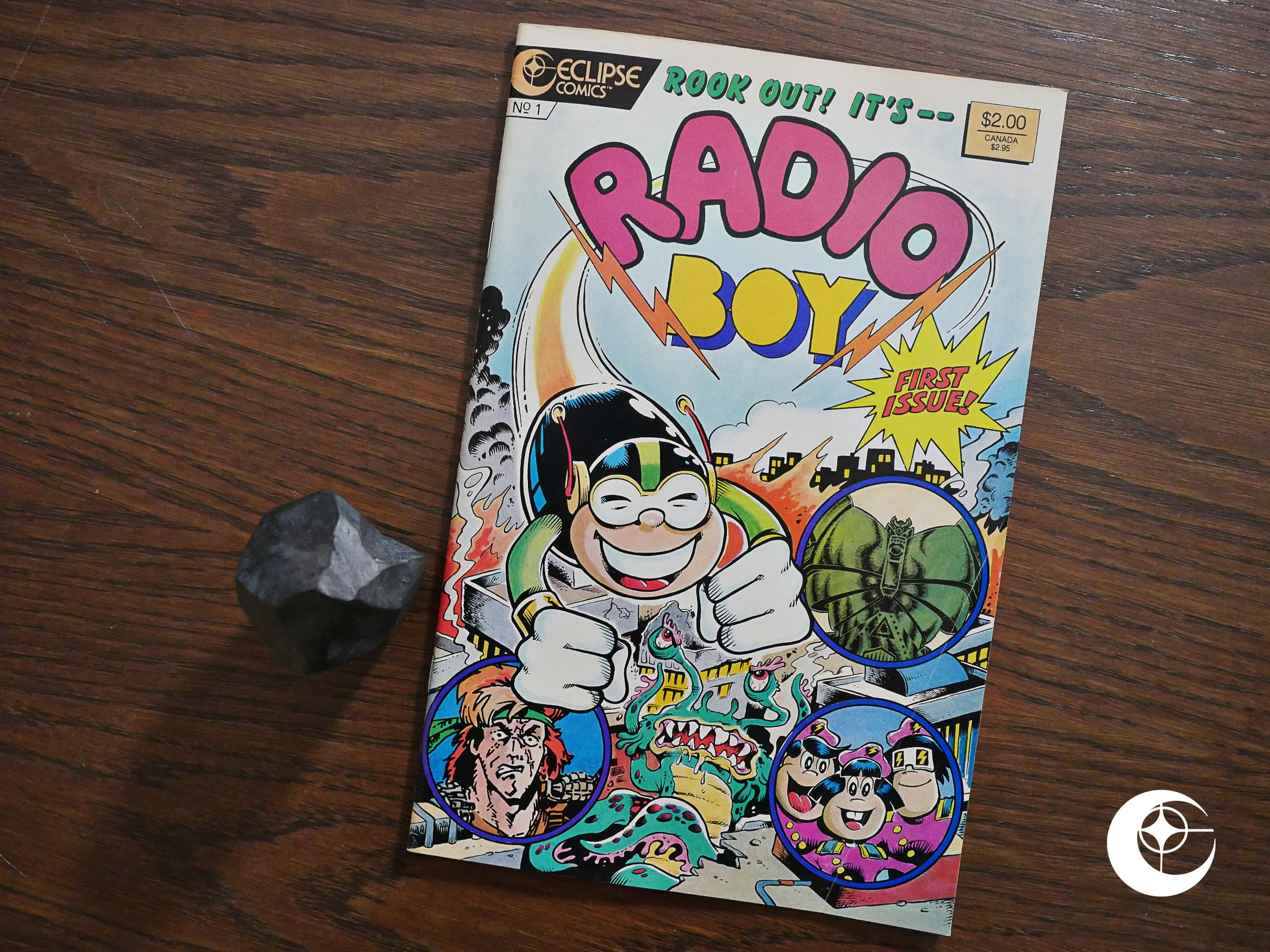

Elf-Thing (1987) #1 Radio Boy (1987) #1

Radio Boy (1987) #1 Lars of Mars 3-D (1987) #1

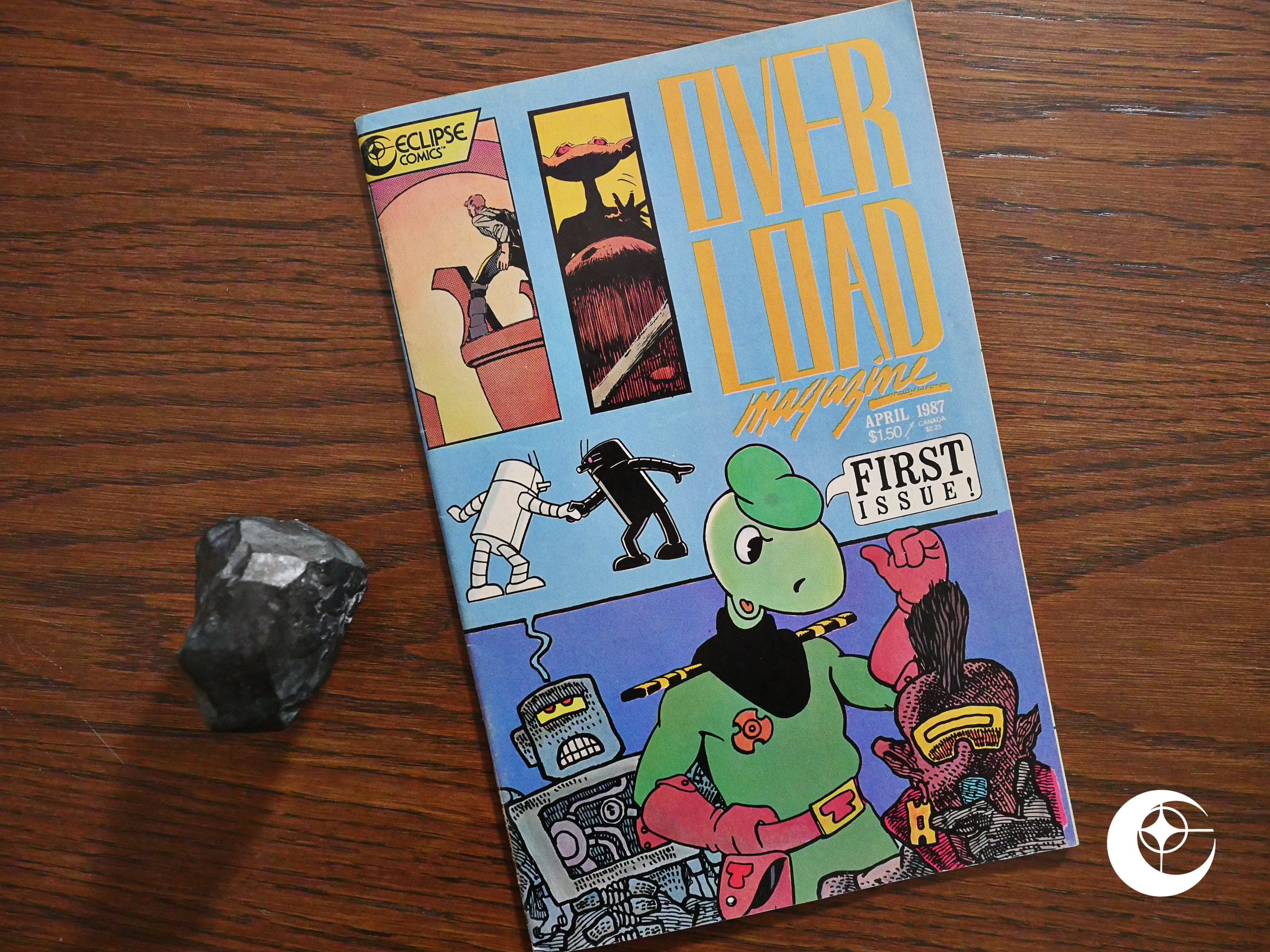

Lars of Mars 3-D (1987) #1 Overload Magazine (1987) #1

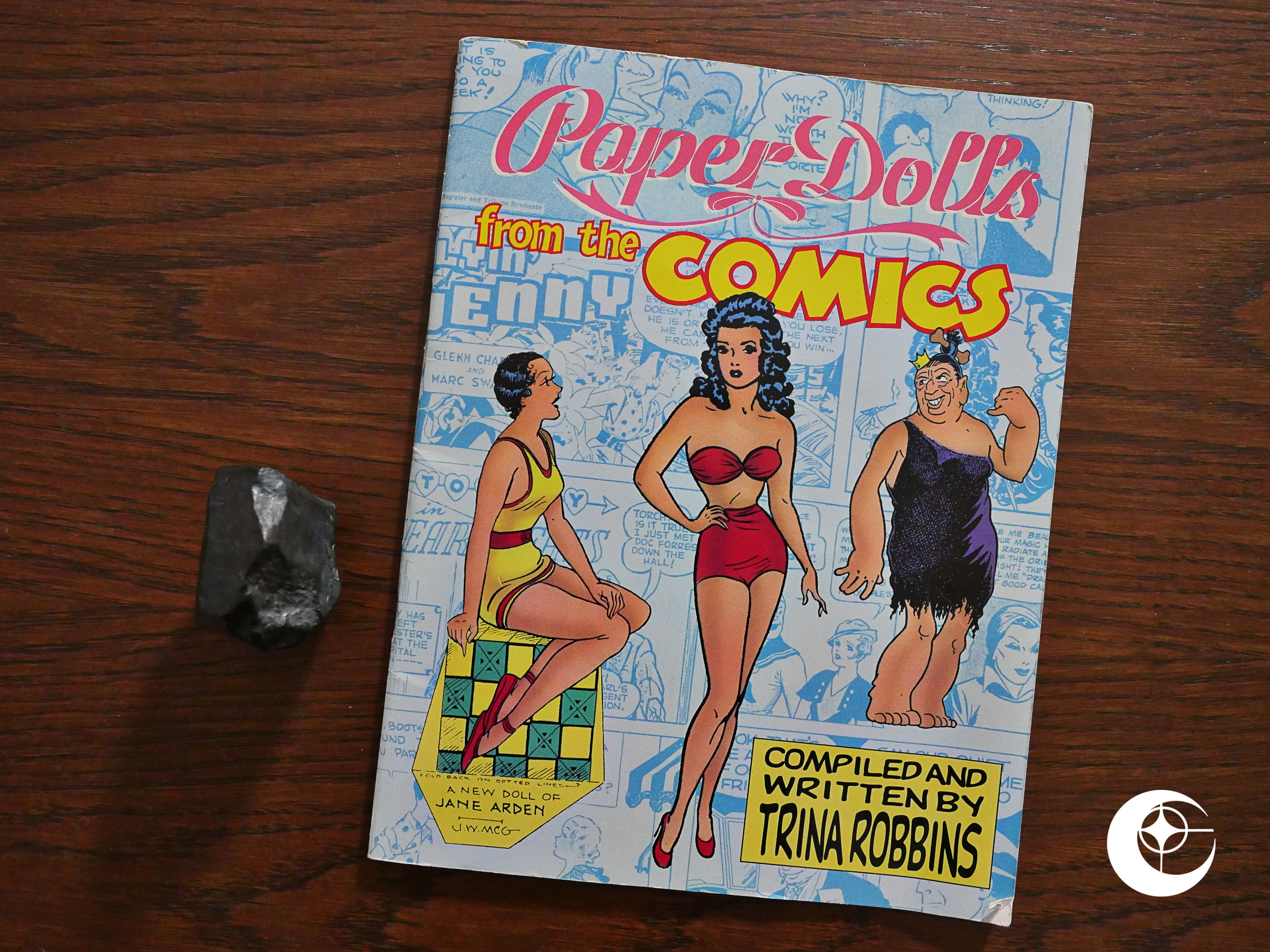

Overload Magazine (1987) #1 Paper Dolls from the Comics (1987) #1

Paper Dolls from the Comics (1987) #1 Area 88 (1987) #1-36

Area 88 (1987) #1-36 Kamui (1987) #1

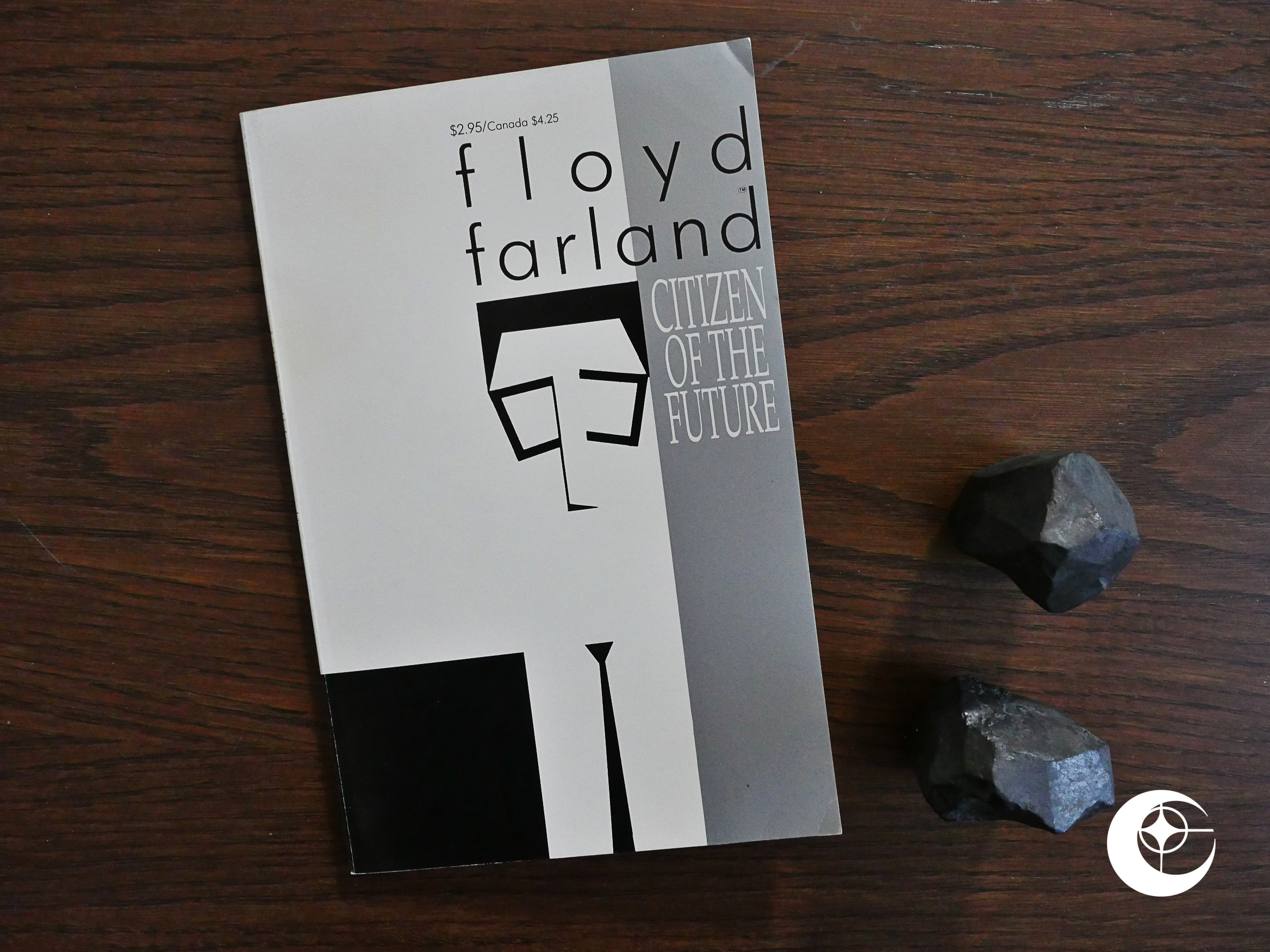

Kamui (1987) #1 Floyd Farland – Citizen of the Future (1987)

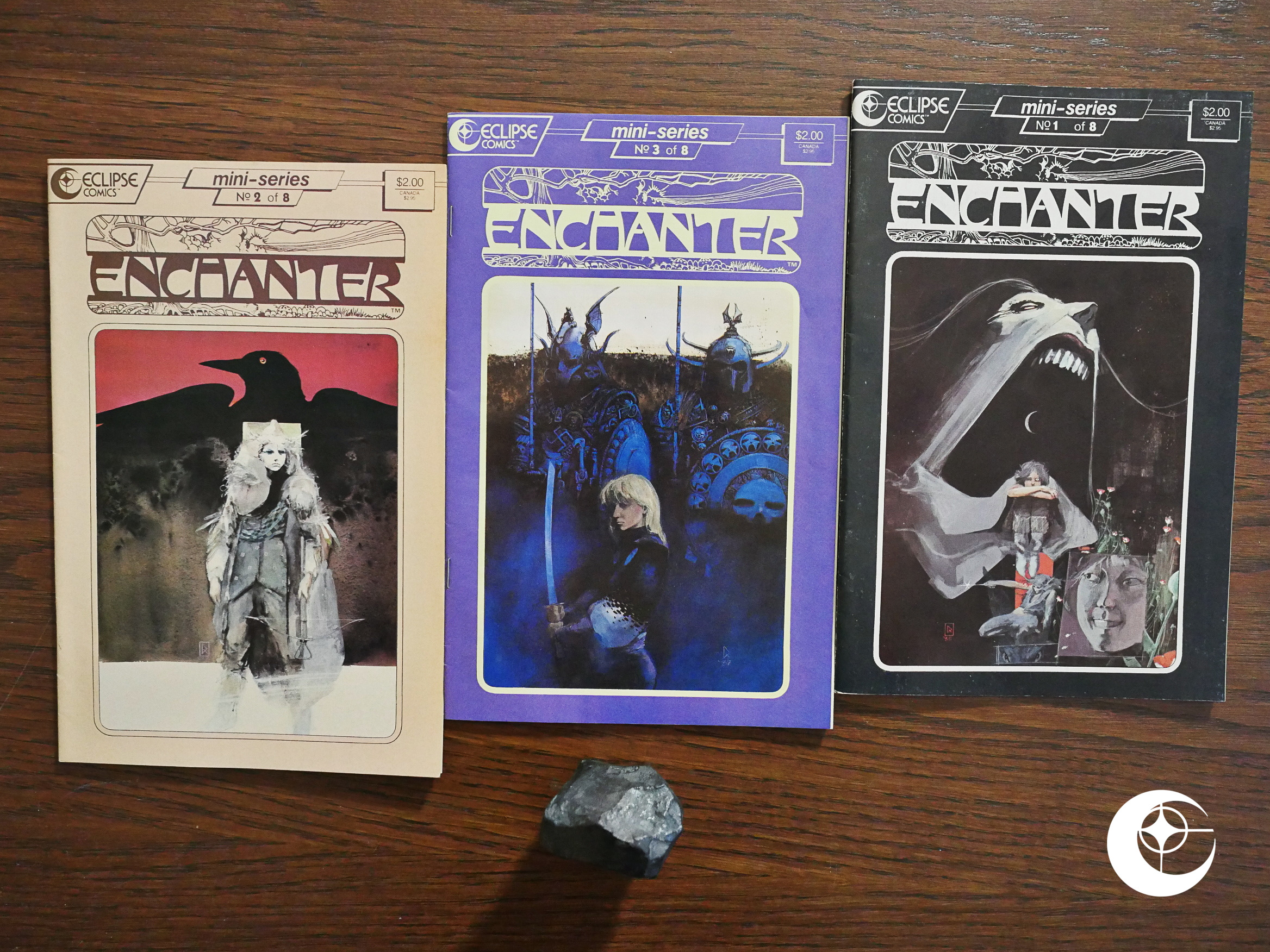

Floyd Farland – Citizen of the Future (1987) Enchanter (1987) #1-3

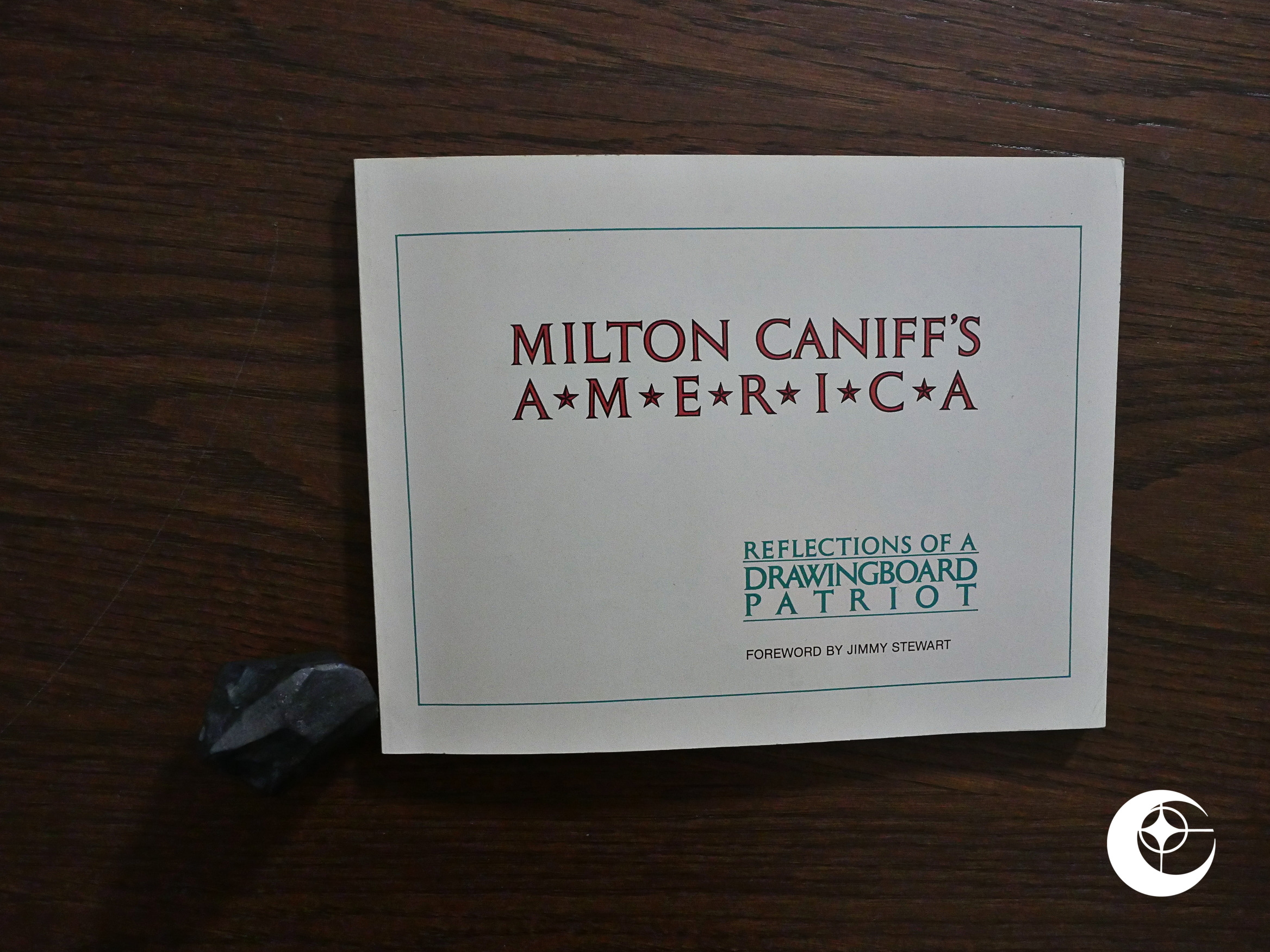

Enchanter (1987) #1-3 Milton Caniff’s America (1987)

Milton Caniff’s America (1987) Lost Planet (1987) #1-6

Lost Planet (1987) #1-6 Mai, the Psychic Girl (1987) #1-28

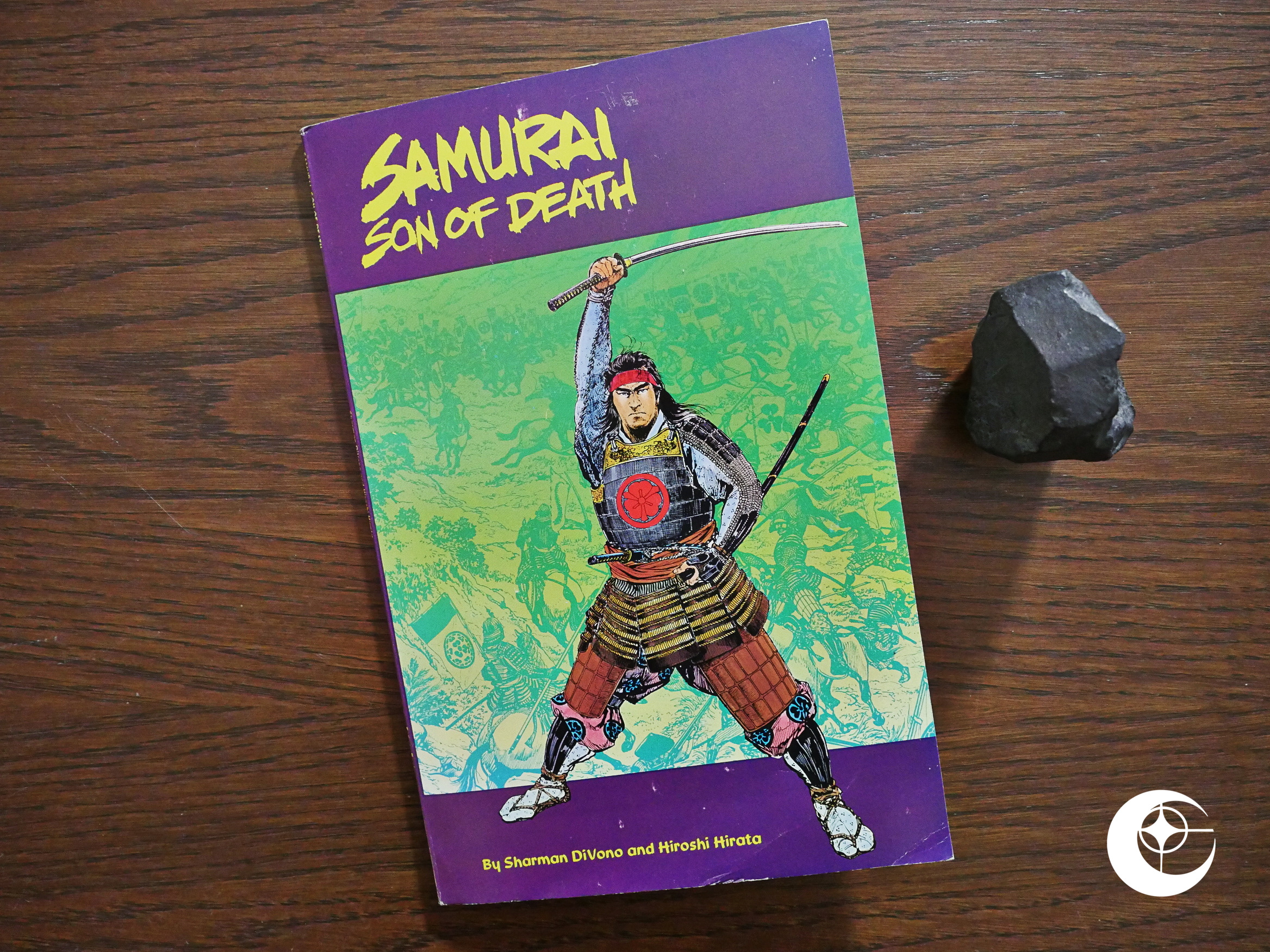

Mai, the Psychic Girl (1987) #1-28 Samurai, Son of Death (1987) #1

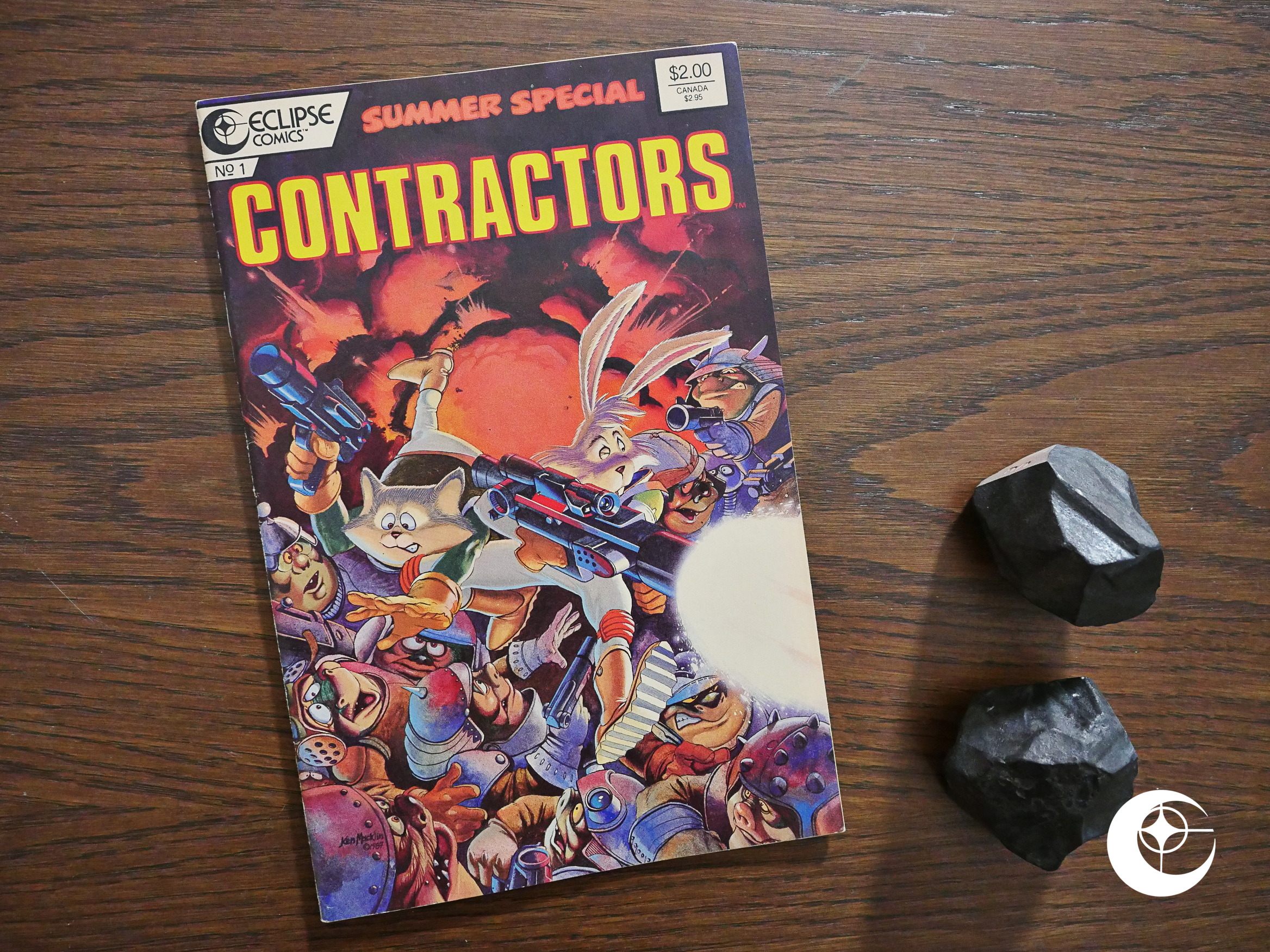

Samurai, Son of Death (1987) #1 Contractors (1987) #1

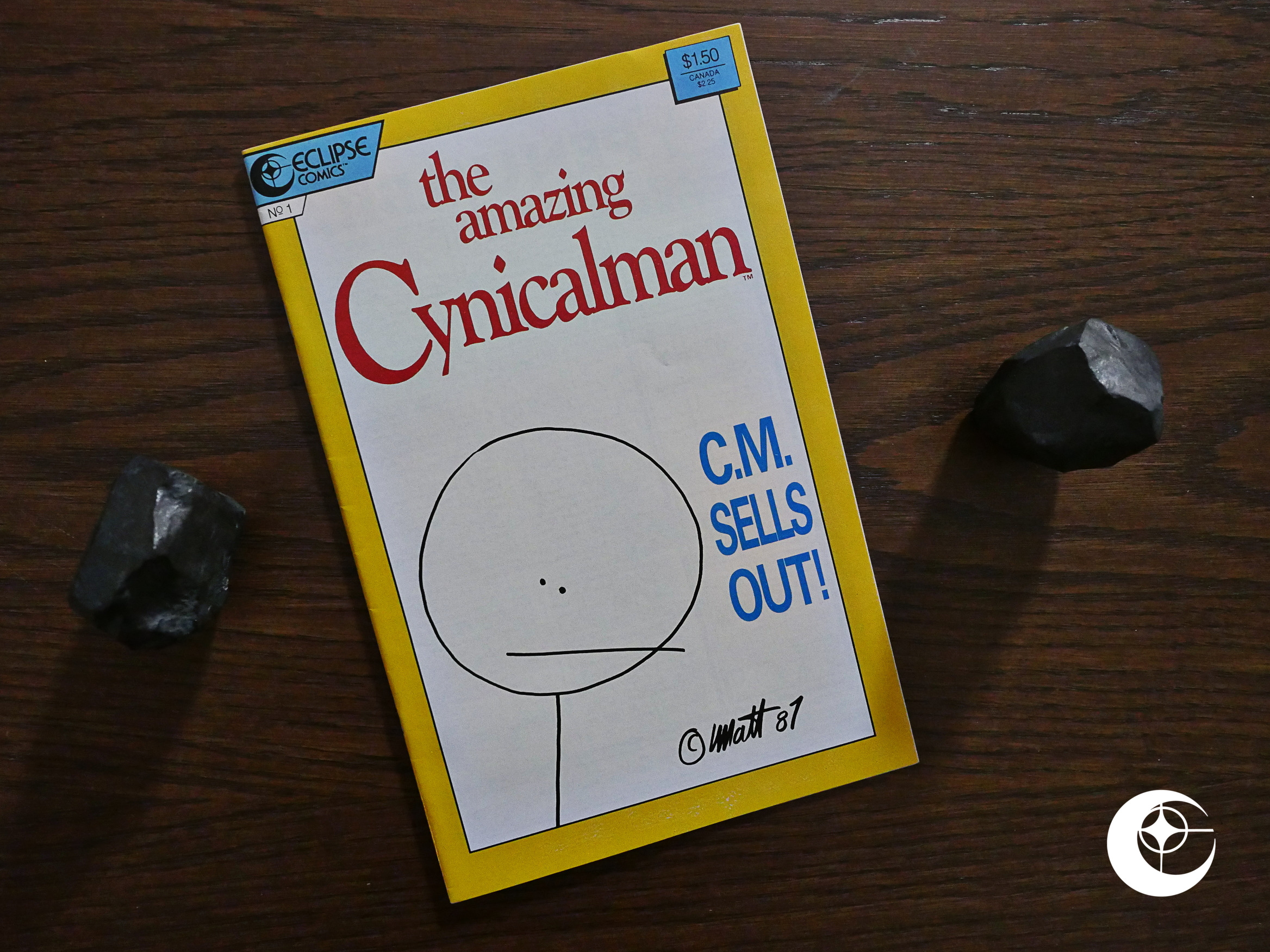

Contractors (1987) #1 The Amazing Cynicalman (1987) #1

The Amazing Cynicalman (1987) #1 California Girls (1987) #1-8

California Girls (1987) #1-8 Hotspur (1987) #1-3

Hotspur (1987) #1-3 The Sisterhood of Steel (1987)

The Sisterhood of Steel (1987) The Liberty Project (1987) #1-8

The Liberty Project (1987) #1-8 Captain EO 3-D (1987) #1

Captain EO 3-D (1987) #1 The Prowler (1987) #1-4

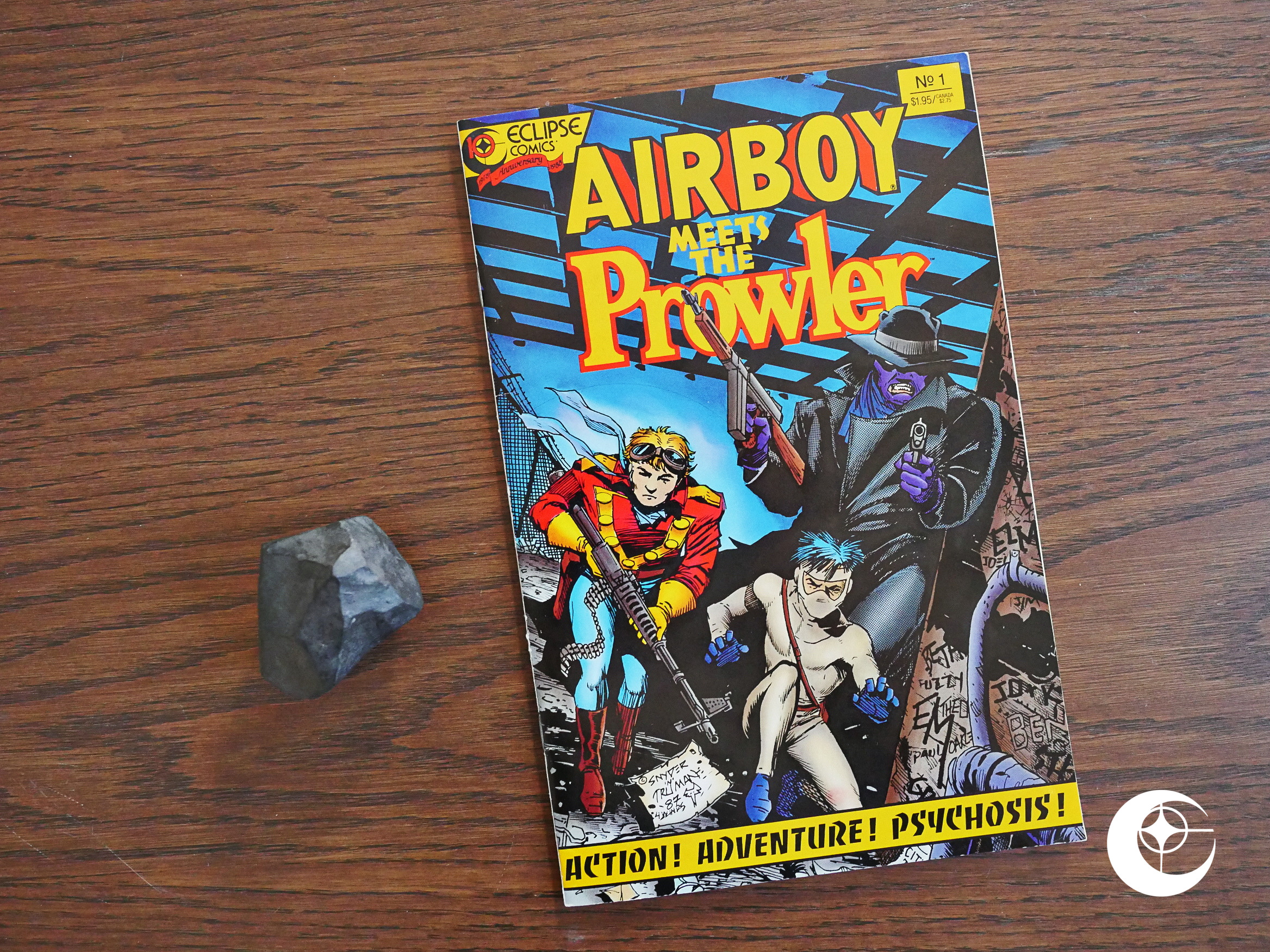

The Prowler (1987) #1-4 Airboy Meets the Prowler (1987) #1

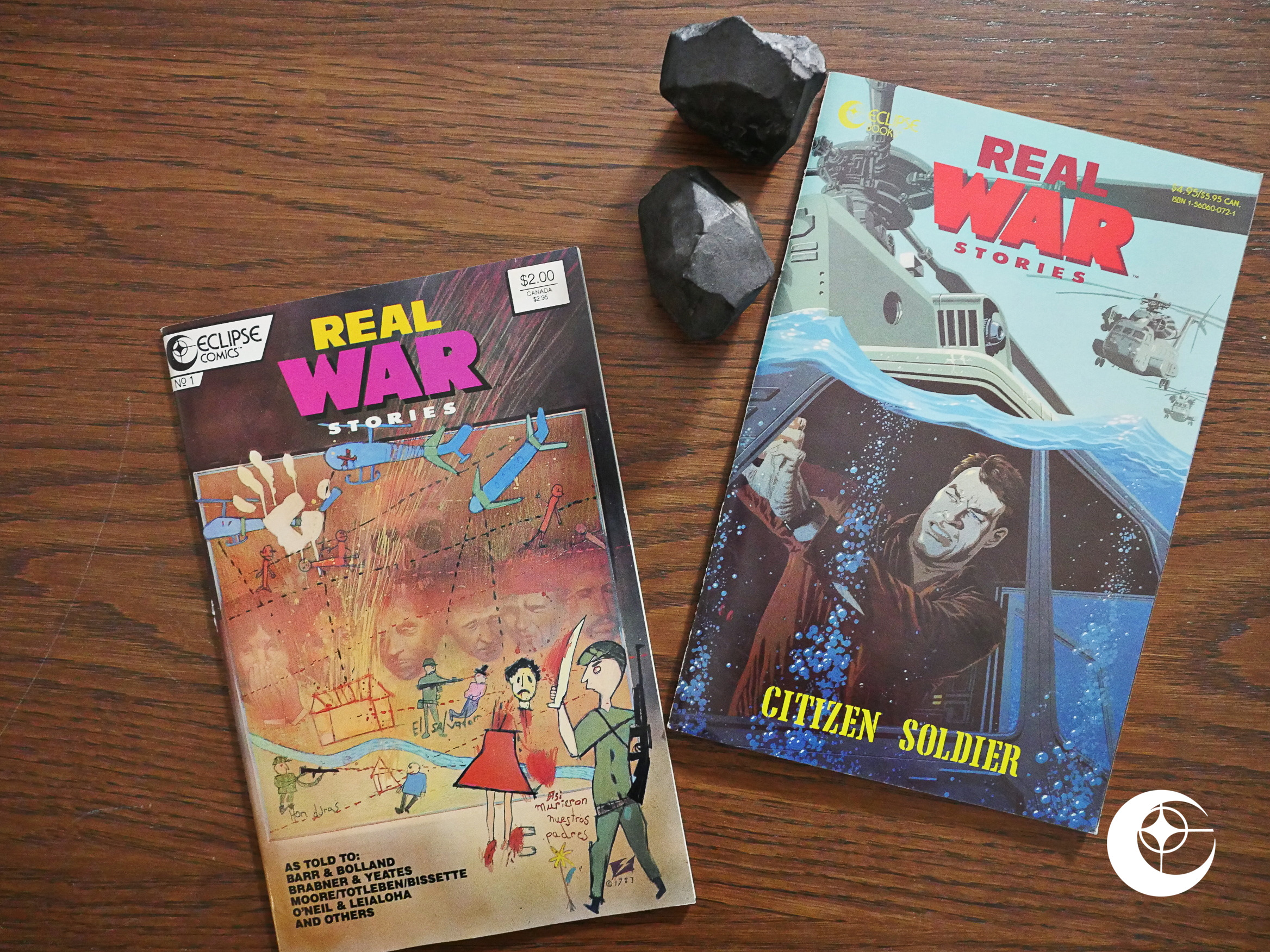

Airboy Meets the Prowler (1987) #1 Real War Stories (1987) #1-2

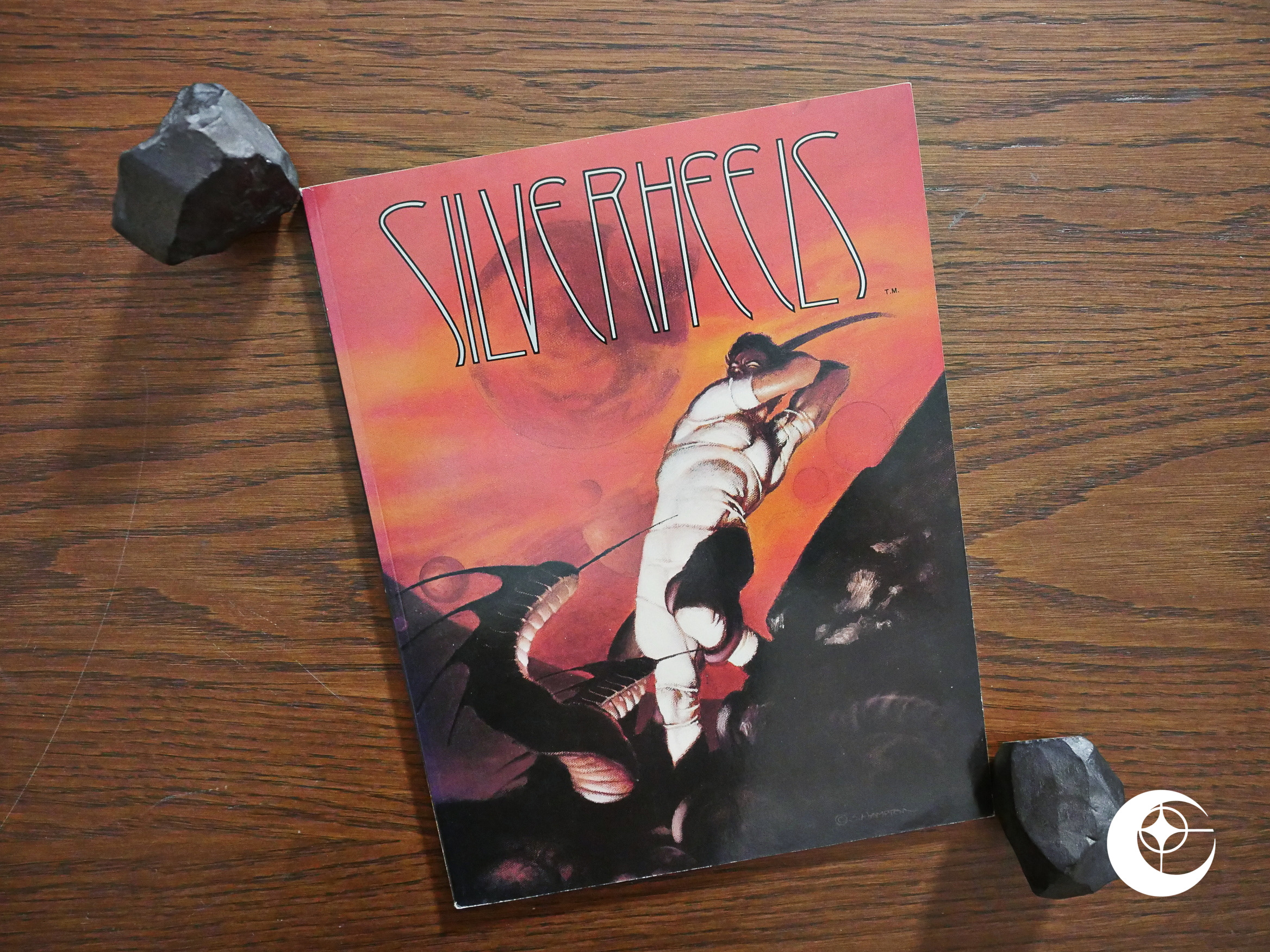

Real War Stories (1987) #1-2 Silverheels (1987) #1

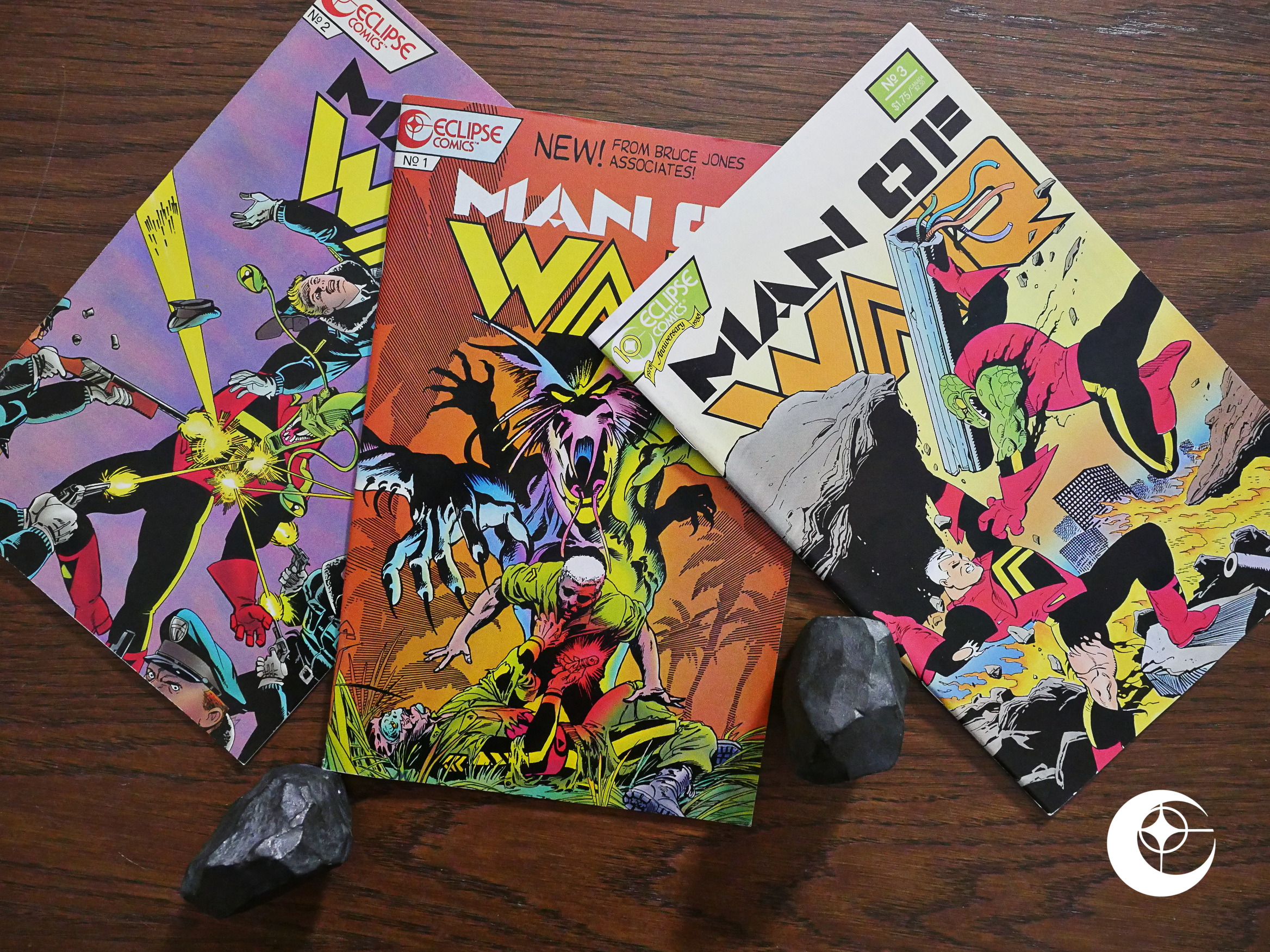

Silverheels (1987) #1 Man of War (1987) #1-3

Man of War (1987) #1-3 Strike! (1987) #1-6

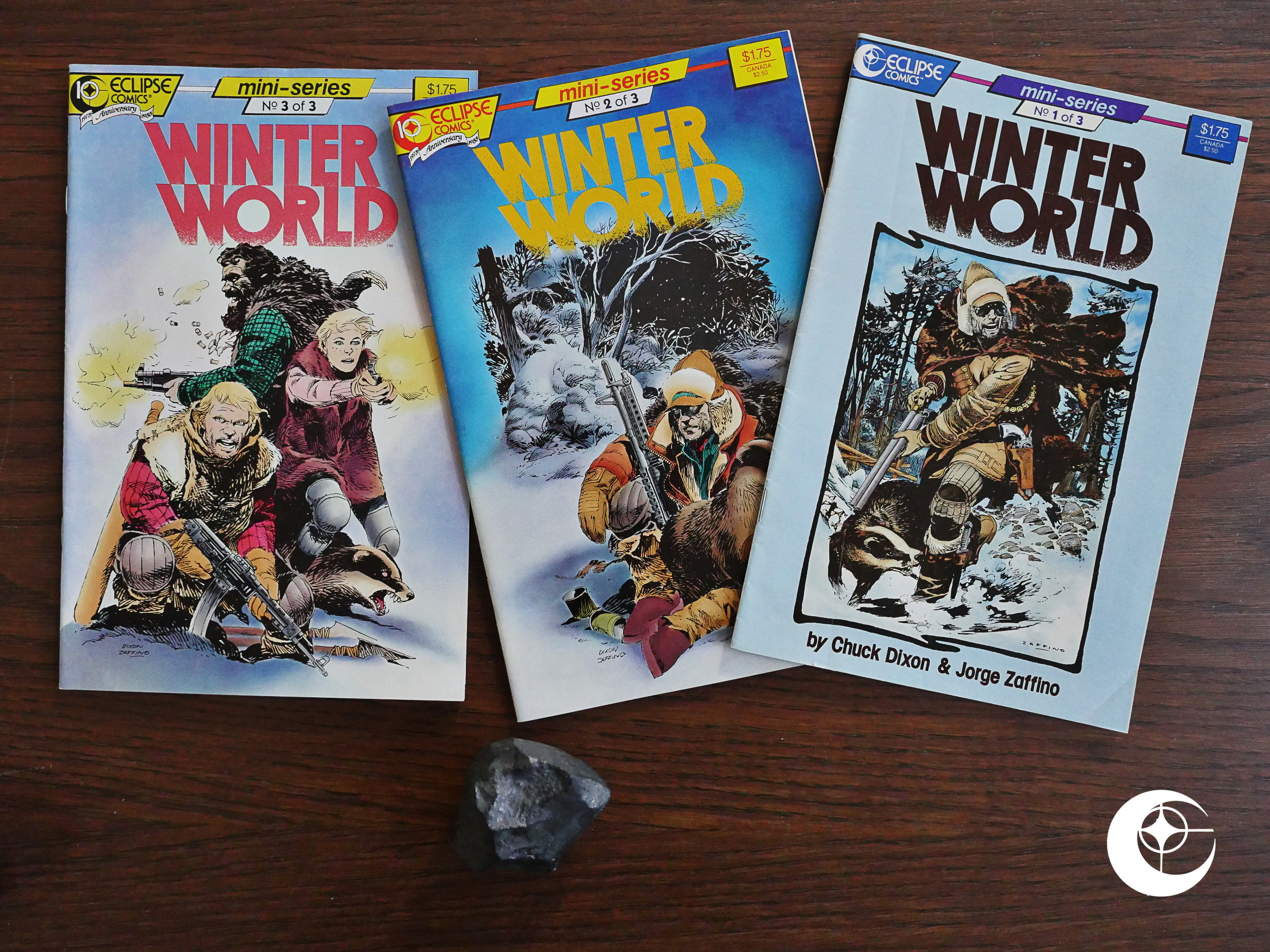

Strike! (1987) #1-6 Winter World (1987) #1-3

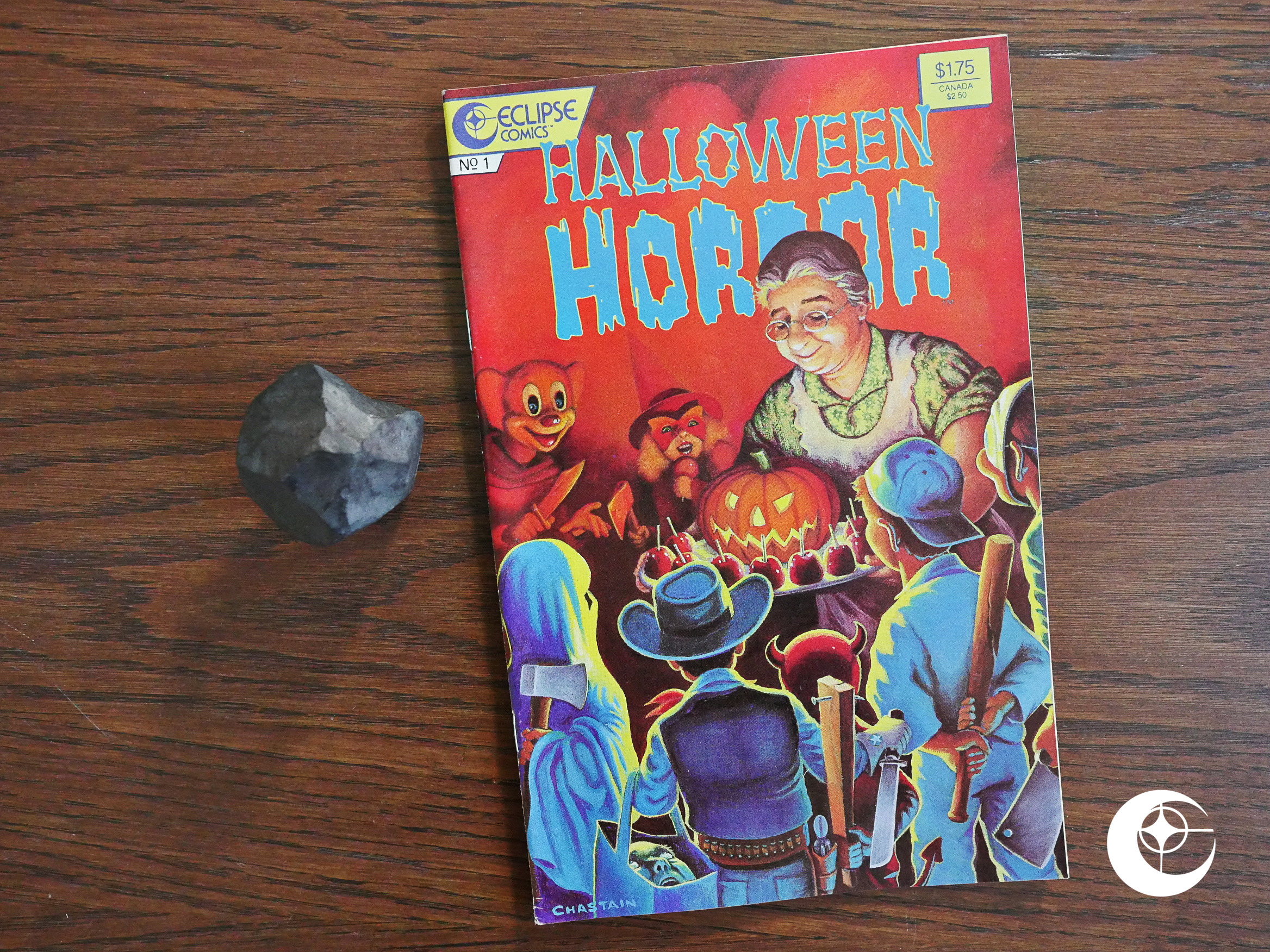

Winter World (1987) #1-3 Halloween Horror (1987) #1

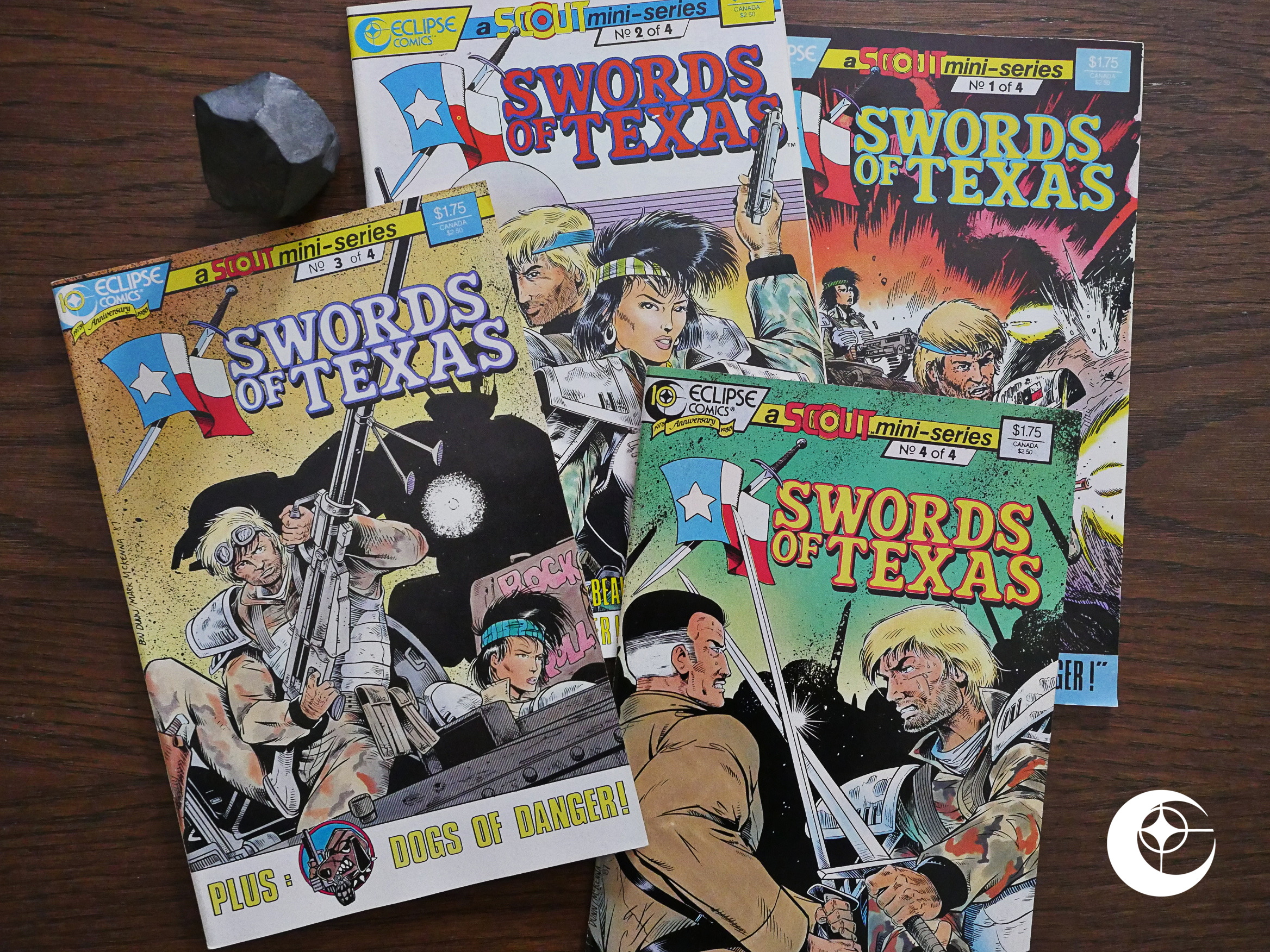

Halloween Horror (1987) #1 Swords of Texas (1987) #1-4

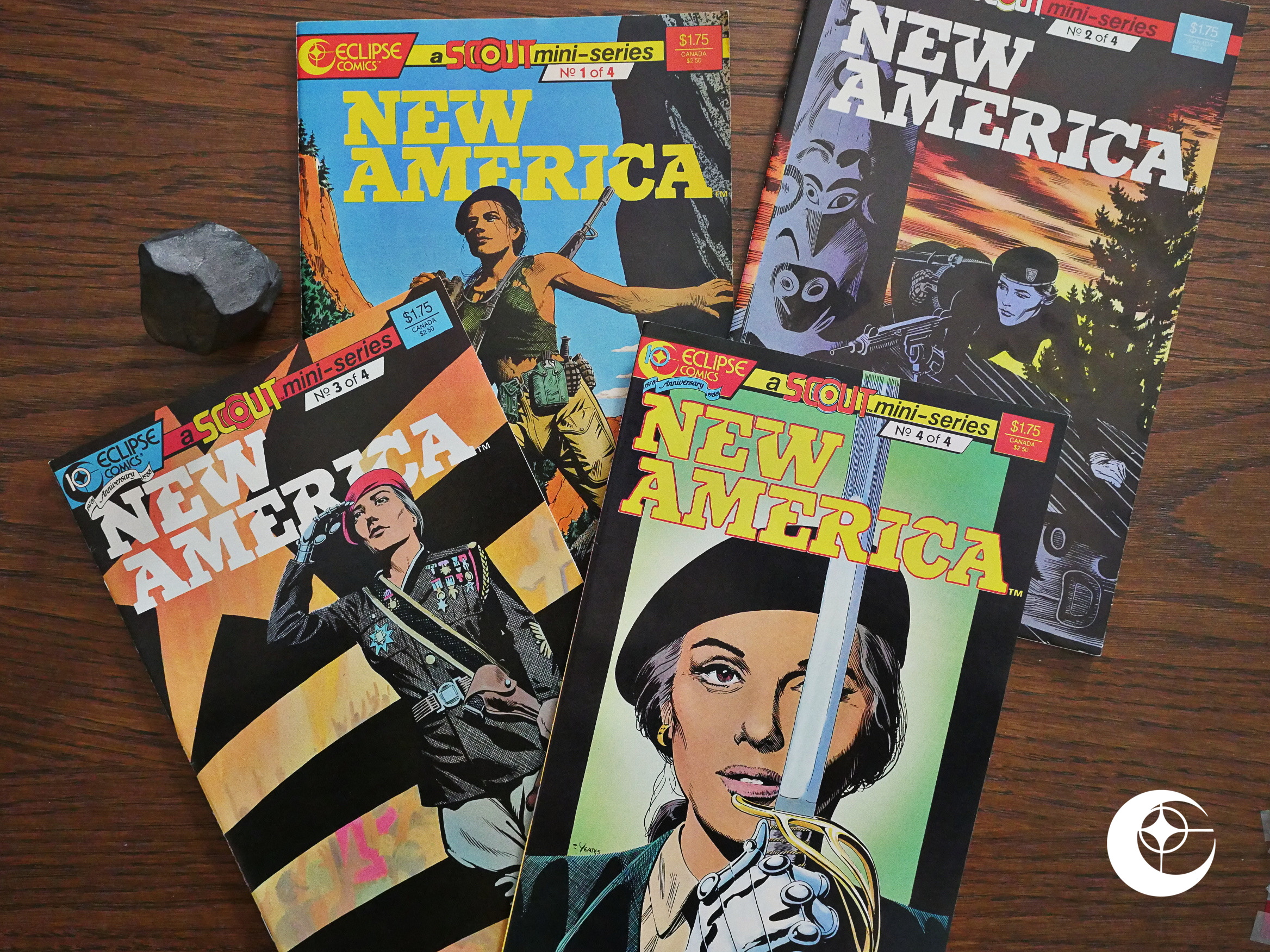

Swords of Texas (1987) #1-4 New America (1987) #1-4

New America (1987) #1-4 Air Fighters Classics (1987) #1-6

Air Fighters Classics (1987) #1-6 Walt Kelly’s Christmas Classics (1987) #1

Walt Kelly’s Christmas Classics (1987) #1 Xenon (1987) #1-23

Xenon (1987) #1-23 Axa (1987) #1-2

Axa (1987) #1-2 Directory to a Non-Existent Universe (1987) #1

Directory to a Non-Existent Universe (1987) #1 Target: Airboy (1988) #1

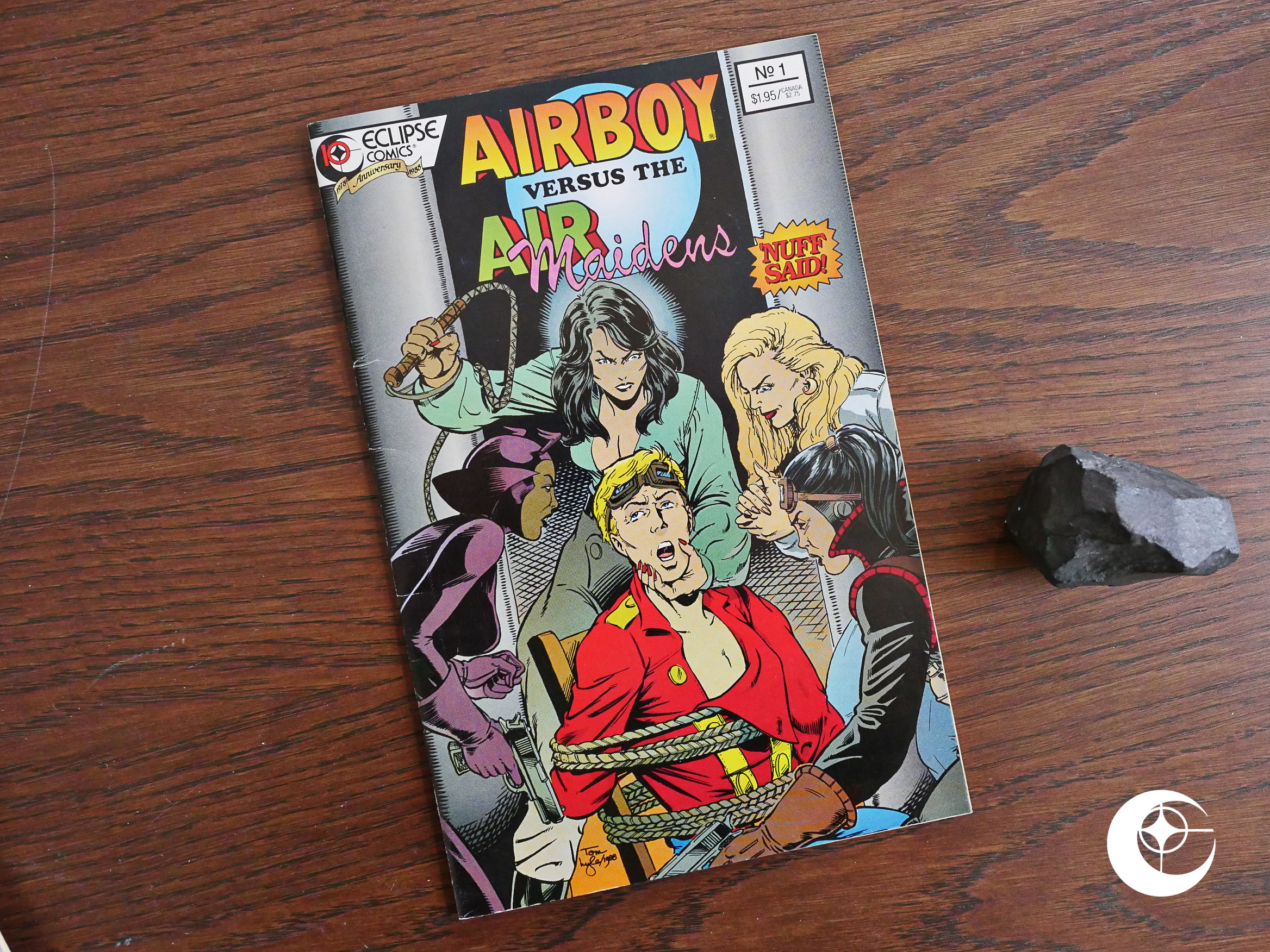

Target: Airboy (1988) #1 Airboy versus the Airmaidens (1988) #1

Airboy versus the Airmaidens (1988) #1 Valkyrie! (1988) #1-3

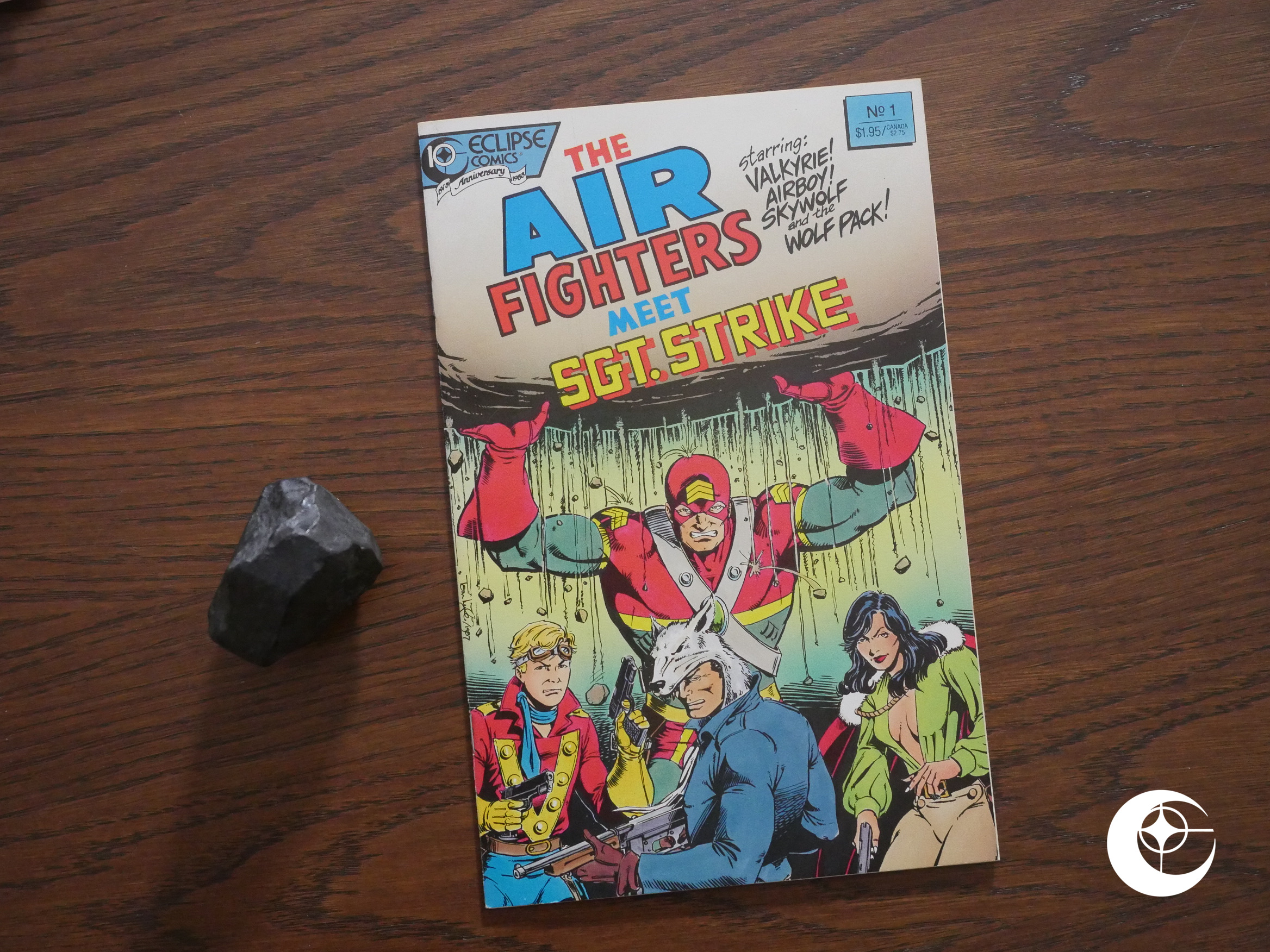

Valkyrie! (1988) #1-3 The Airfighters Meet Sgt. Strike Special (1988) #1

The Airfighters Meet Sgt. Strike Special (1988) #1 Total Eclipse: The Seraphim Objective (1988) #1

Total Eclipse: The Seraphim Objective (1988) #1 The Revenge of the Prowler (1988) #1-4

The Revenge of the Prowler (1988) #1-4 The Prowler in White Zombie (1988) #1

The Prowler in White Zombie (1988) #1 Hand of Fate (1988) #1-3

Hand of Fate (1988) #1-3 Weird Romance (1988) #1

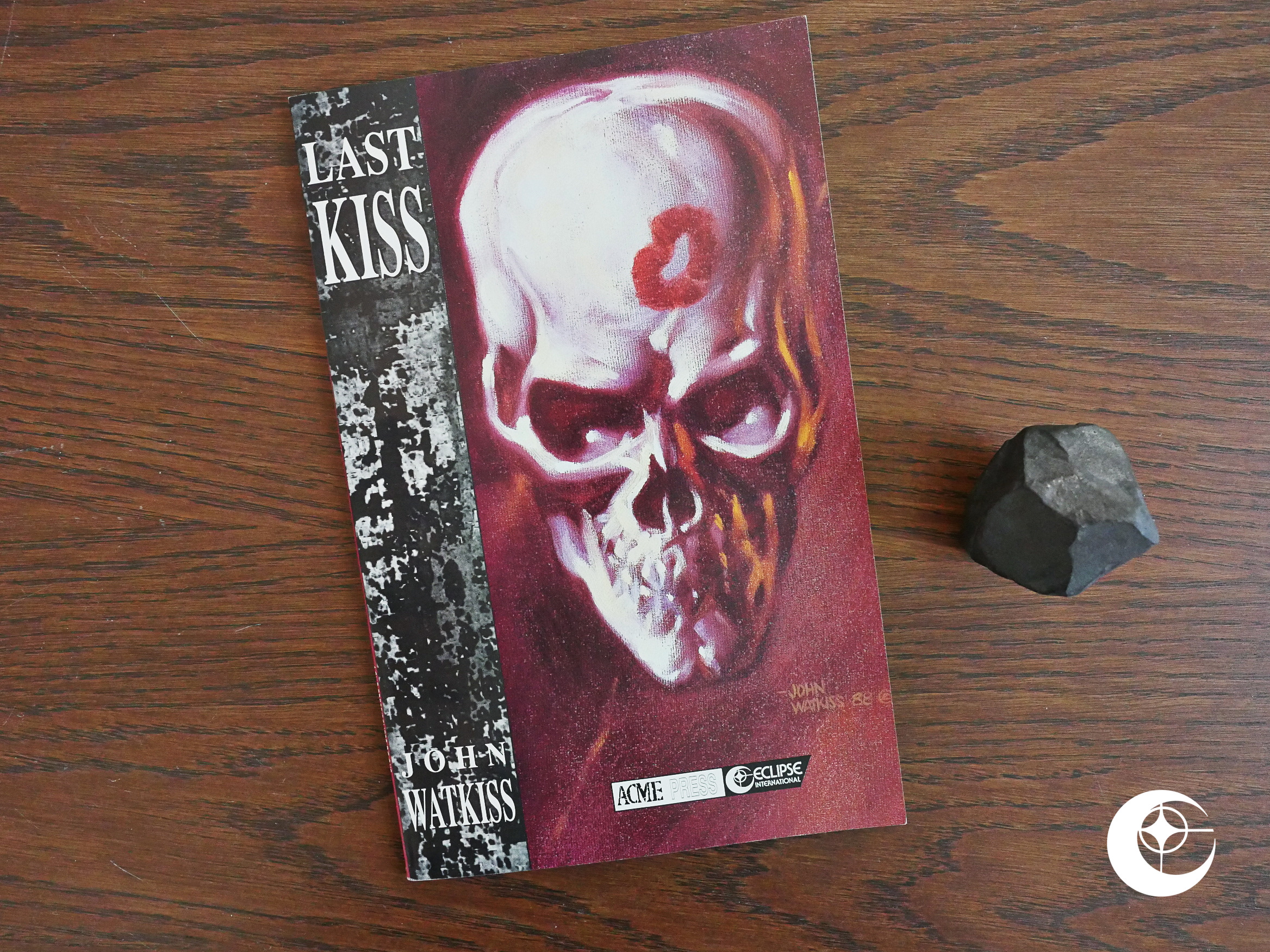

Weird Romance (1988) #1 Last Kiss (1988) #1

Last Kiss (1988) #1 Power Comics (1988) #1-4

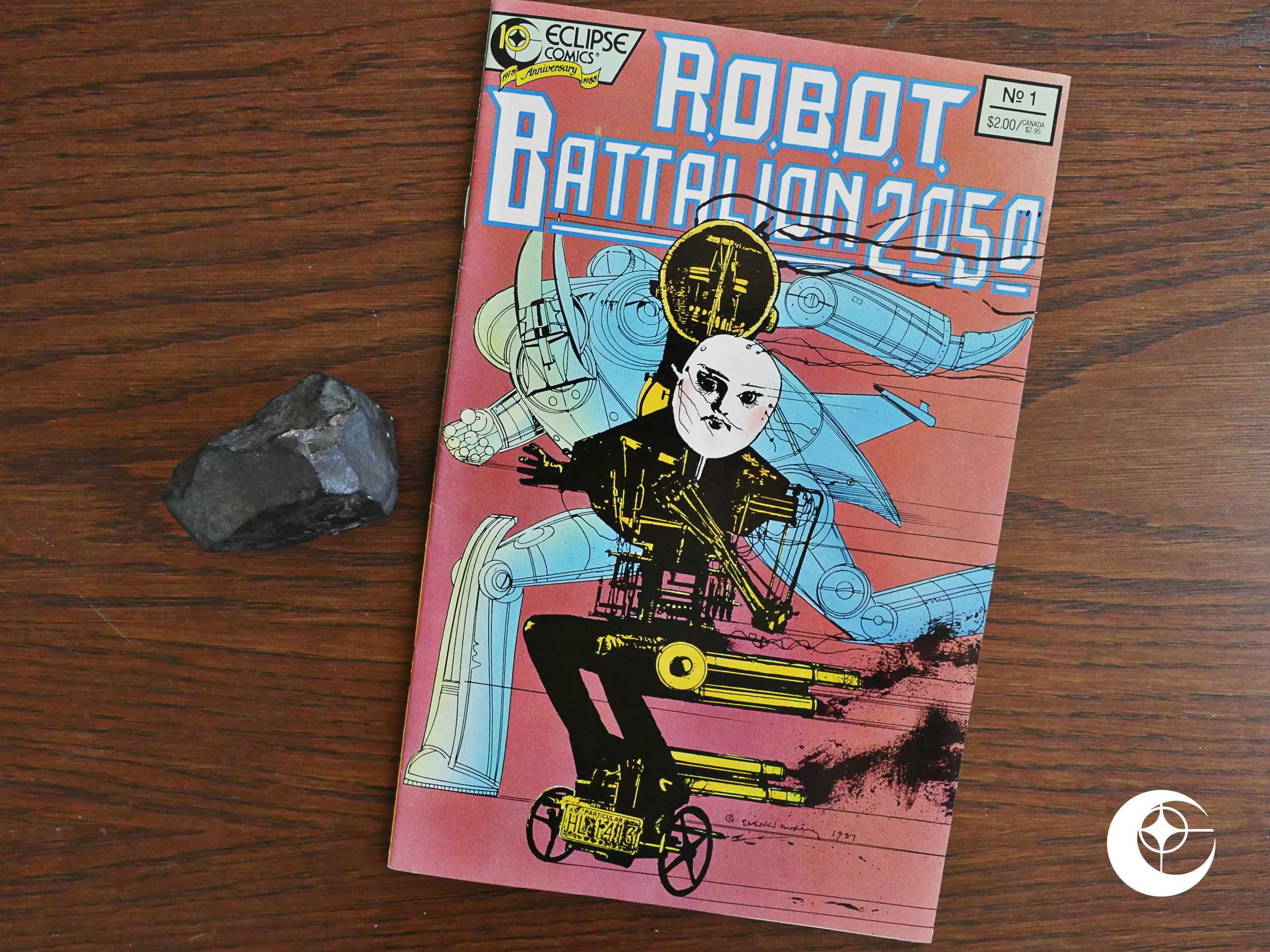

Power Comics (1988) #1-4 R.O.B.O.T. Battalion 2050 (1988) #1

R.O.B.O.T. Battalion 2050 (1988) #1 Scout: War Shaman (1988) #1-16

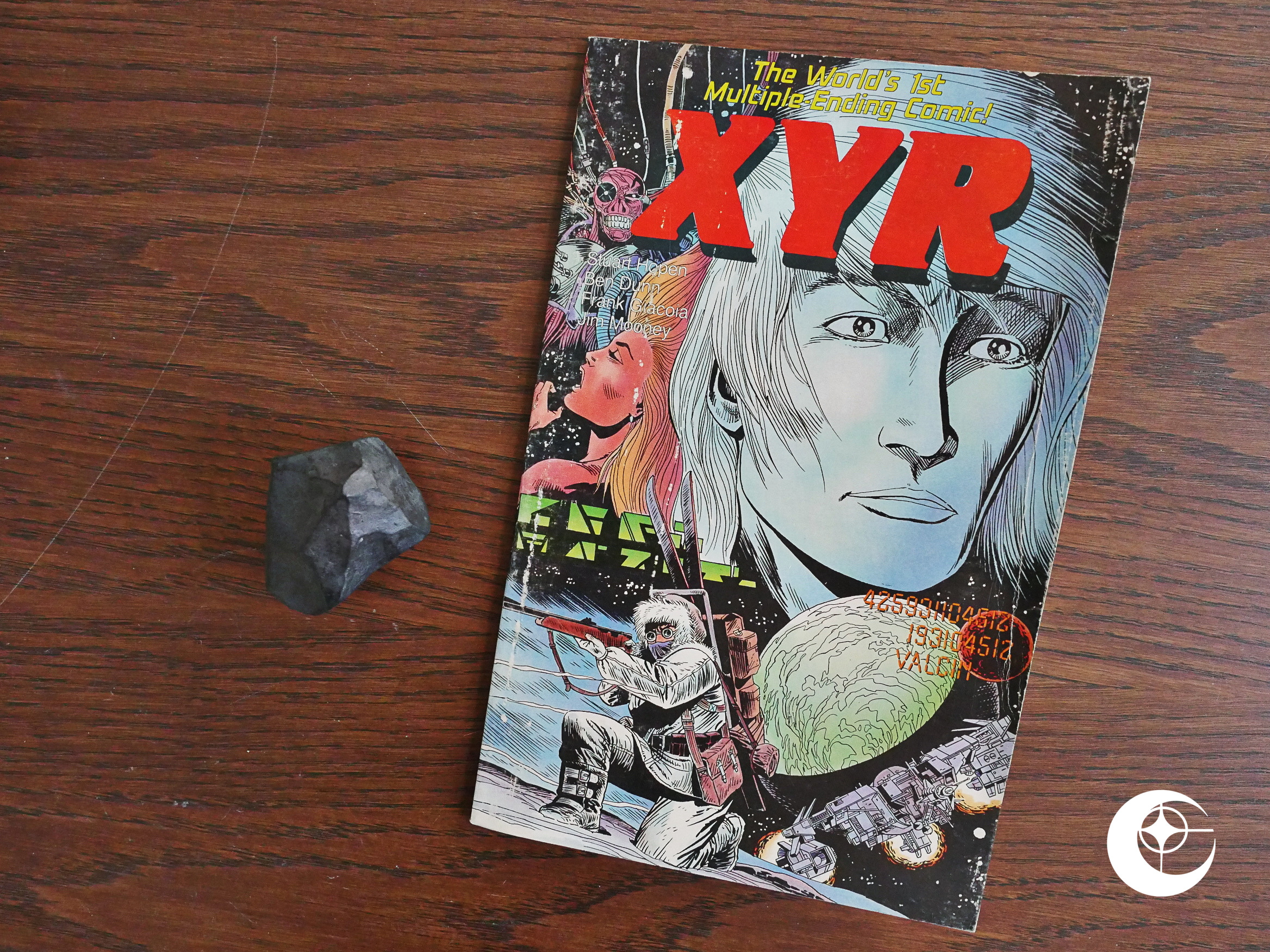

Scout: War Shaman (1988) #1-16 XYR (1988)

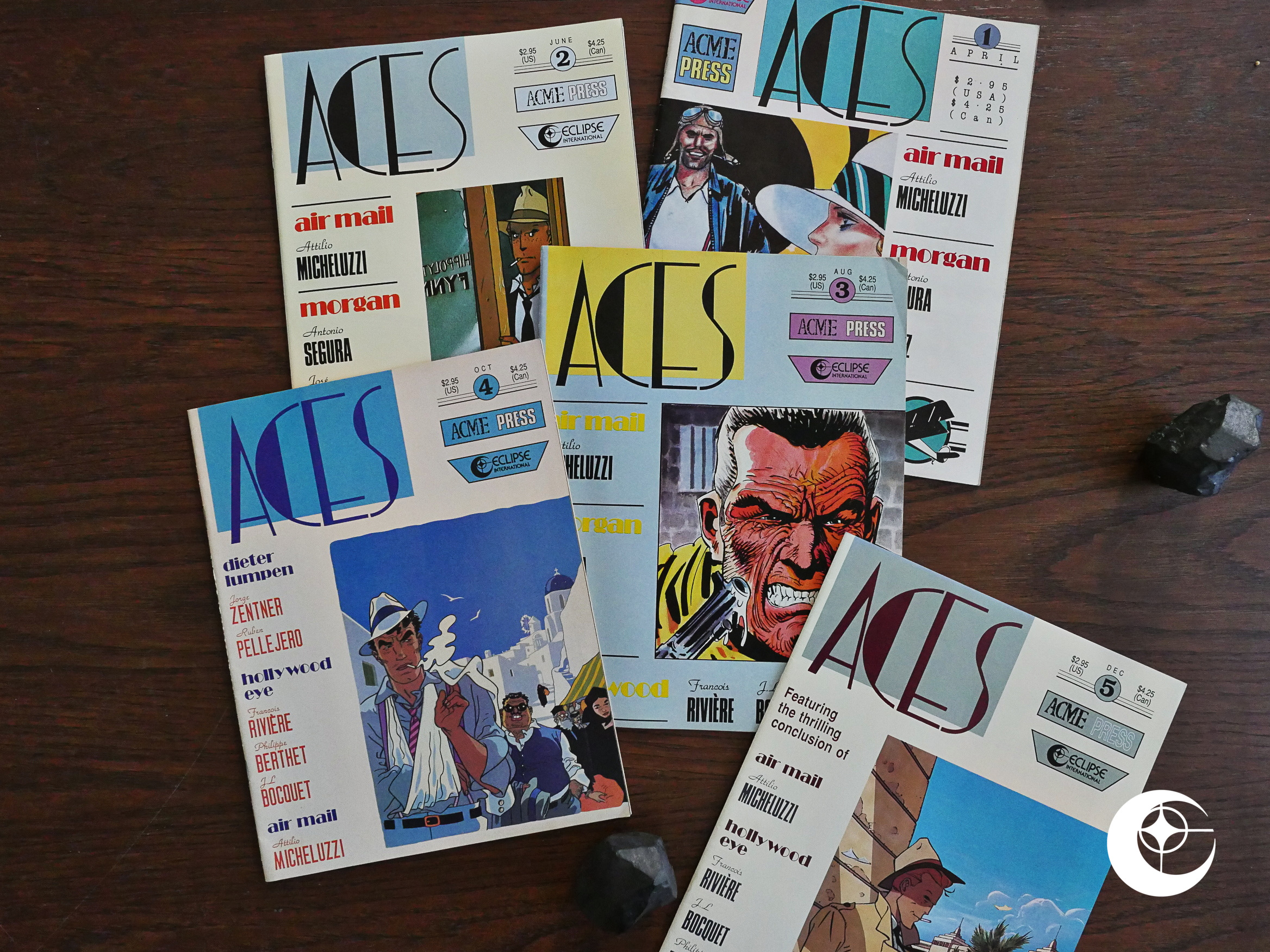

XYR (1988) Aces (1988) #1-5

Aces (1988) #1-5 Phaze (1988) #1-2

Phaze (1988) #1-2 Total Eclipse (1988) #1-5

Total Eclipse (1988) #1-5 Zorro: The Complete Classic Adventures by Alex Toth (1988) #1-2

Zorro: The Complete Classic Adventures by Alex Toth (1988) #1-2 Merchants of Death (1988) #1-4

Merchants of Death (1988) #1-4 Fast Fiction (She) (1988) #1

Fast Fiction (She) (1988) #1 Krazy & Ignatz: The Komplete Kat Comics (1988) #1-9

Krazy & Ignatz: The Komplete Kat Comics (1988) #1-9 New York: Year Zero (1988) #1-4

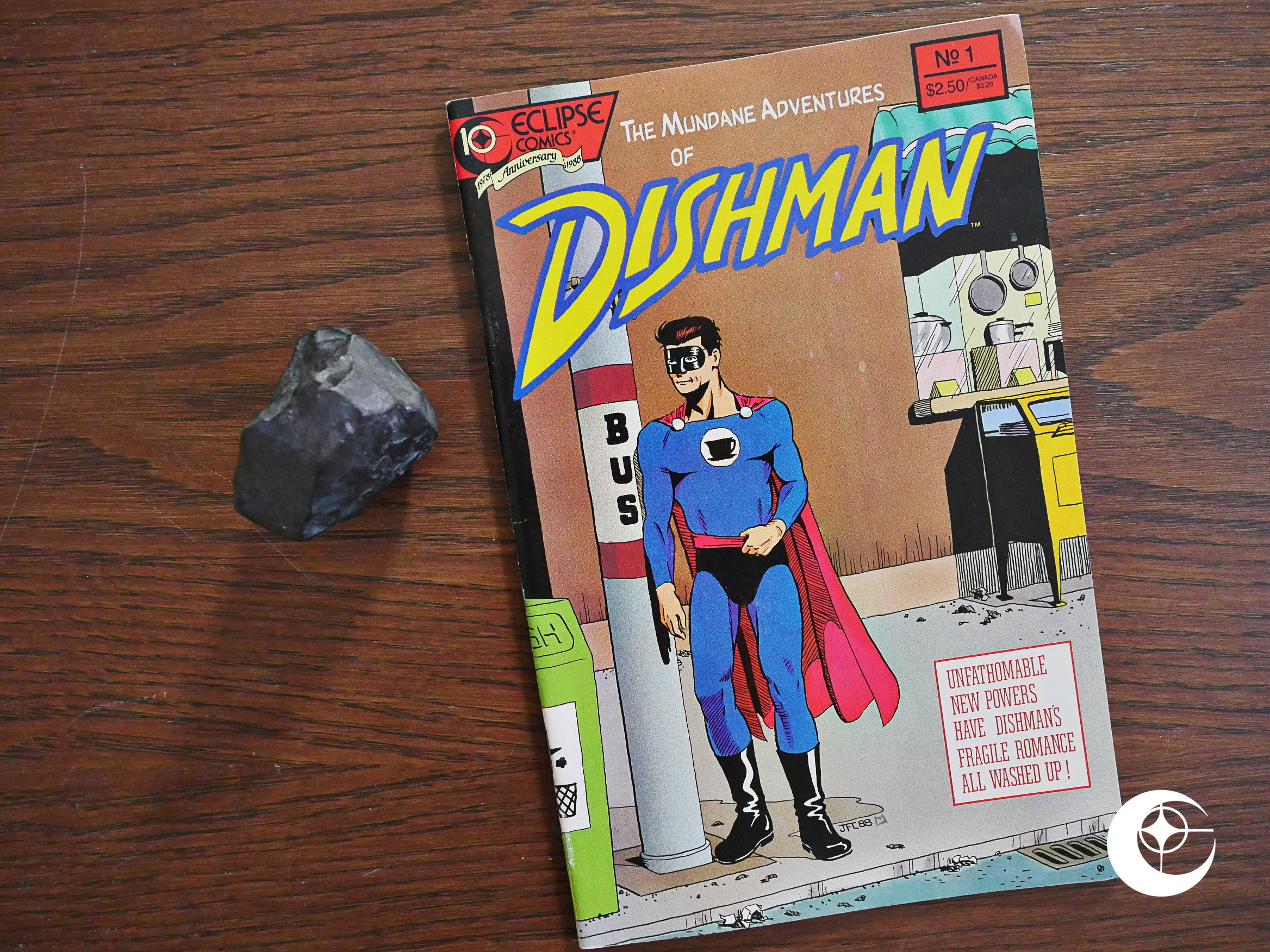

New York: Year Zero (1988) #1-4 Dishman (1988) #1

Dishman (1988) #1 Appleseed (1988) #1-19

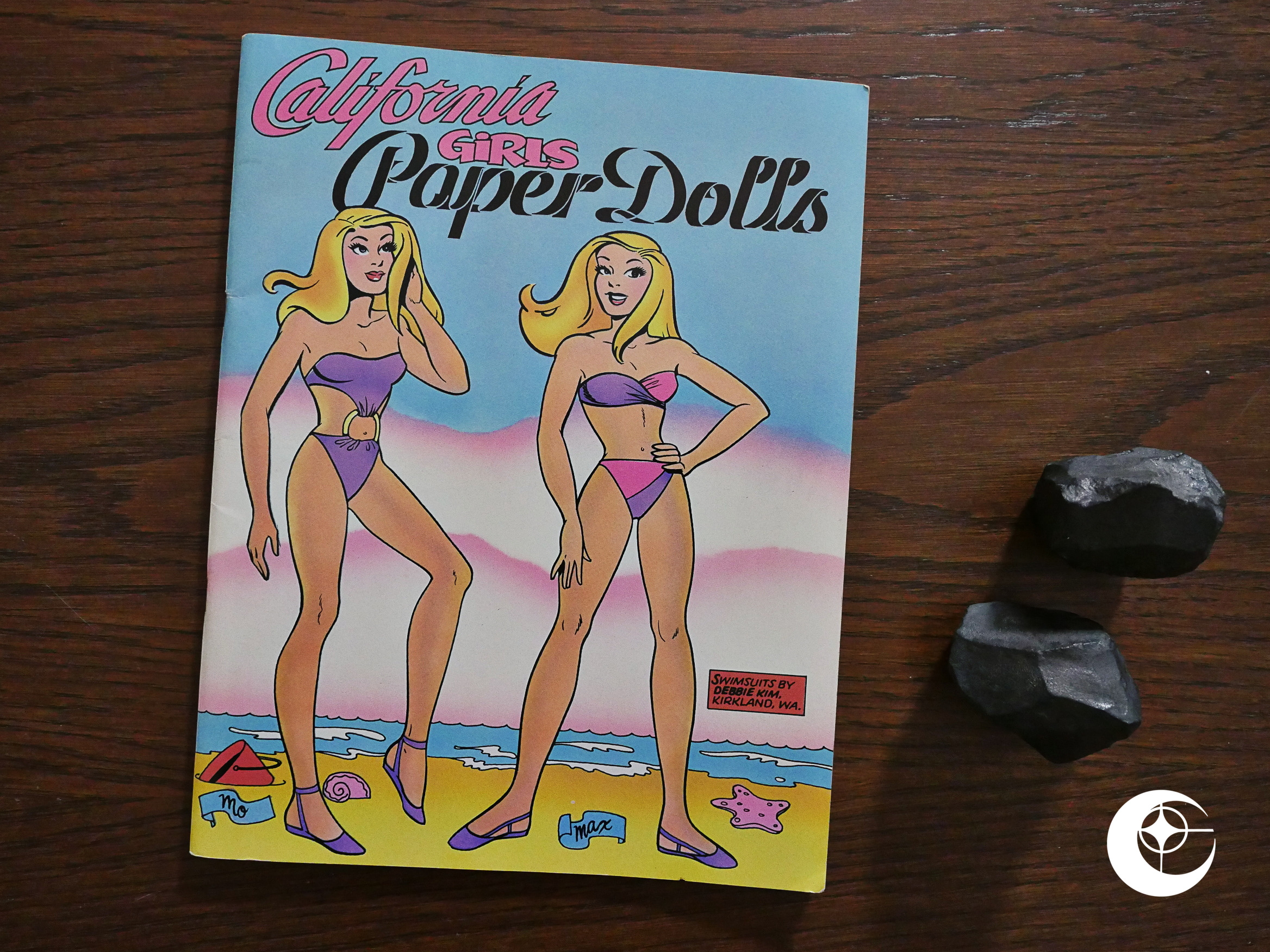

Appleseed (1988) #1-19 California Girls Paper Dolls (1988) #1

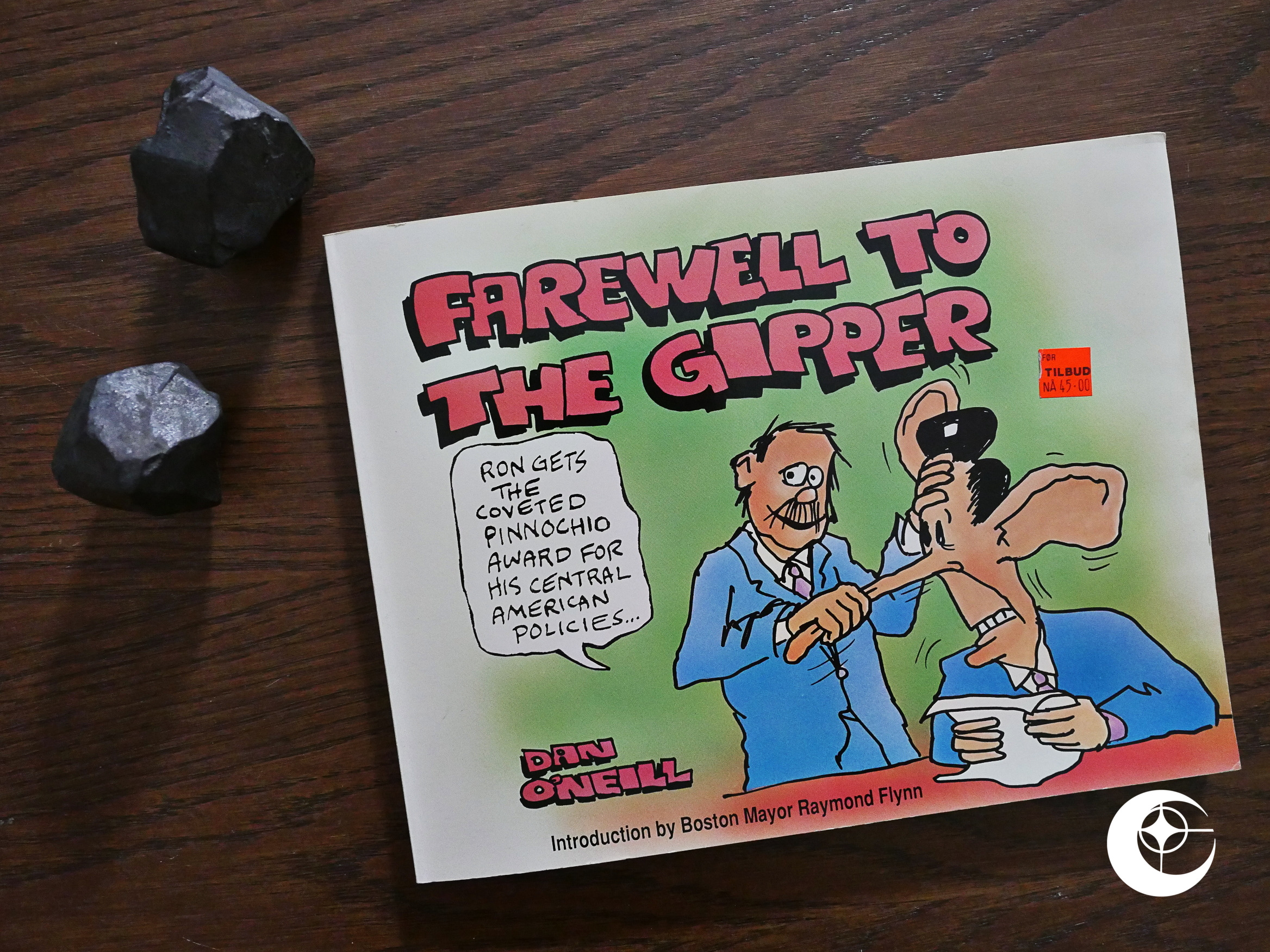

California Girls Paper Dolls (1988) #1 Farewell to the Gipper (1988) #1

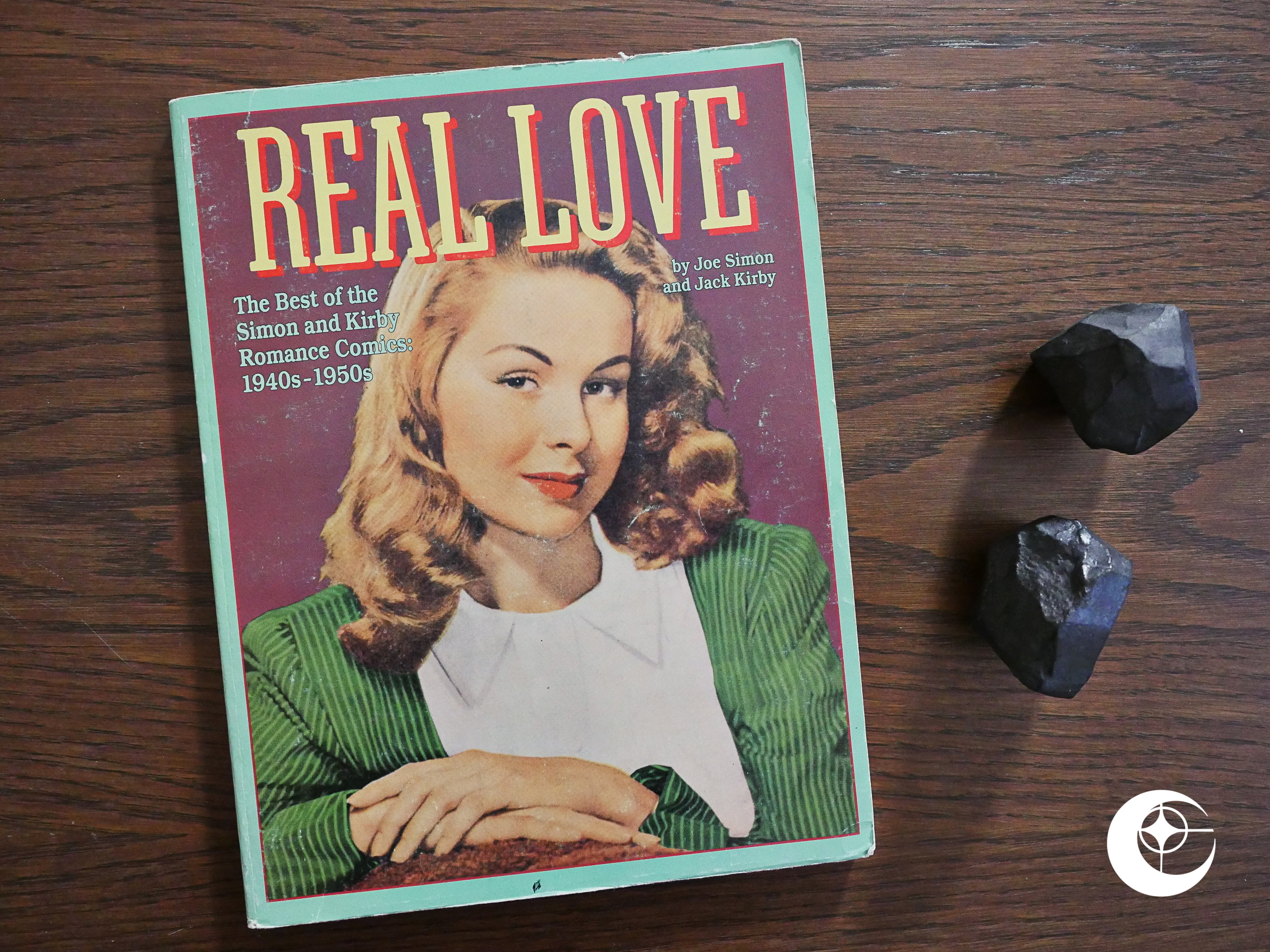

Farewell to the Gipper (1988) #1 Real Love: The Best of Simon and Kirby Romance Comics (1988)

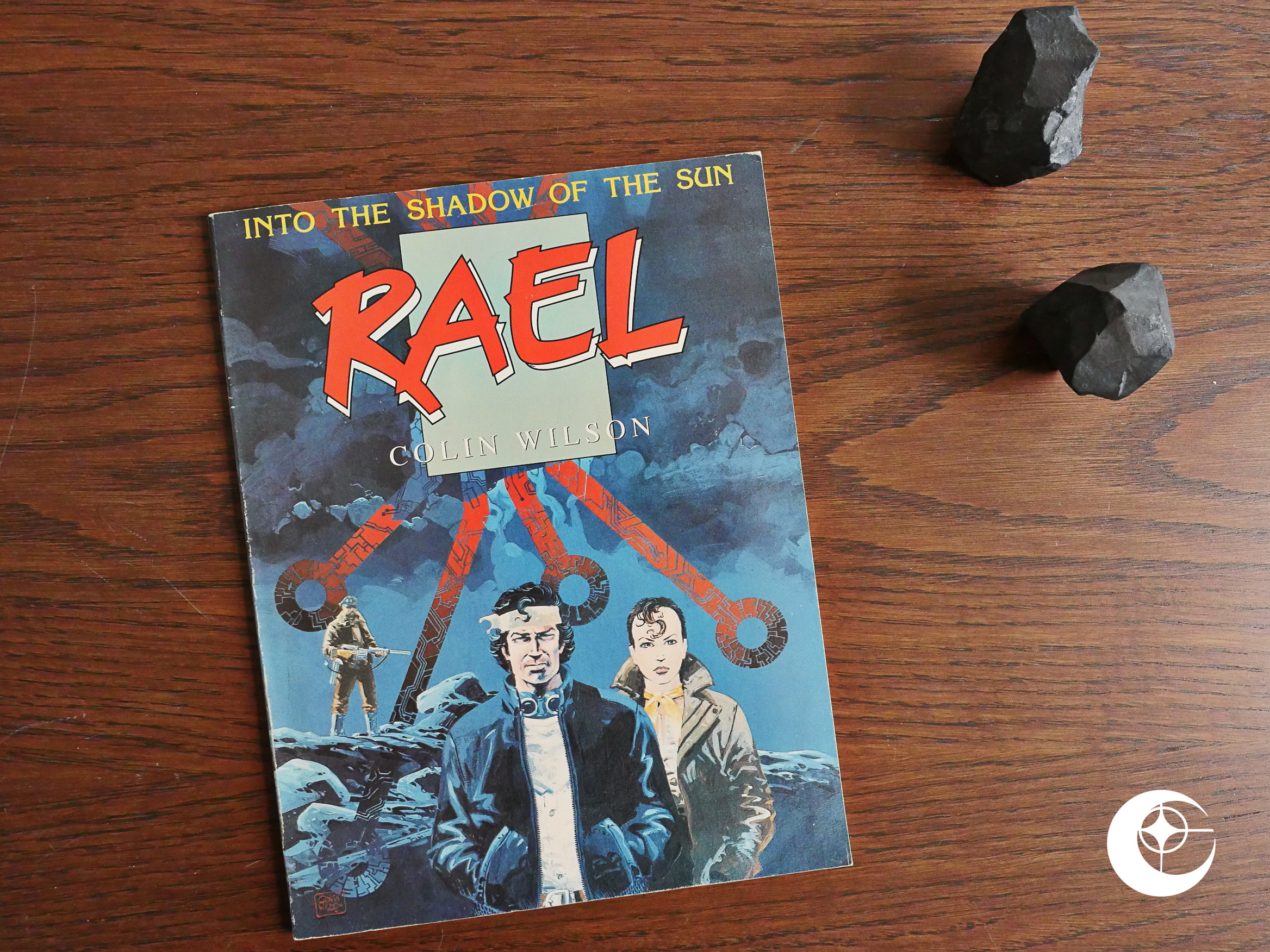

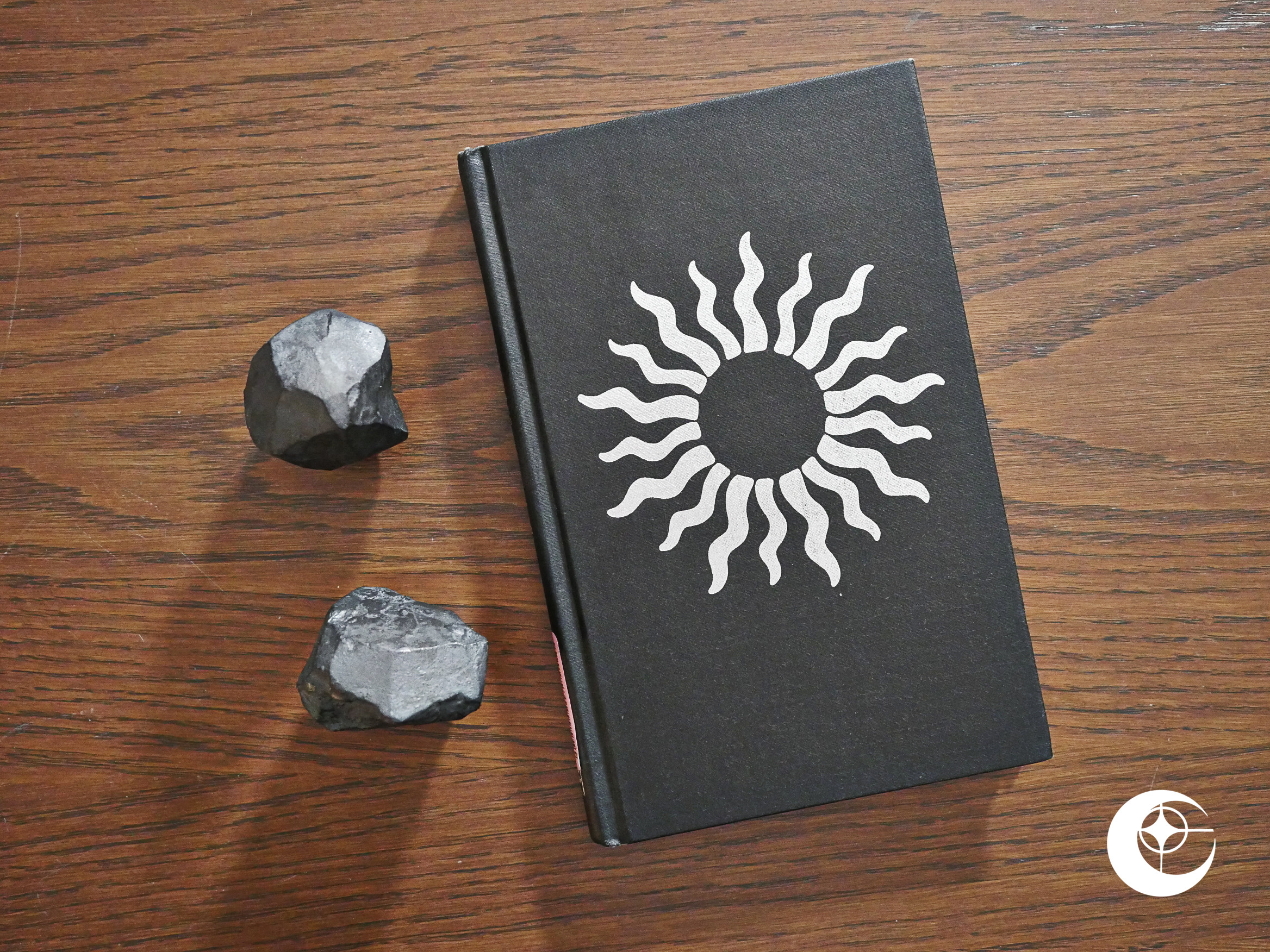

Real Love: The Best of Simon and Kirby Romance Comics (1988) Into the Shadow of the Sun: Rael (1988)

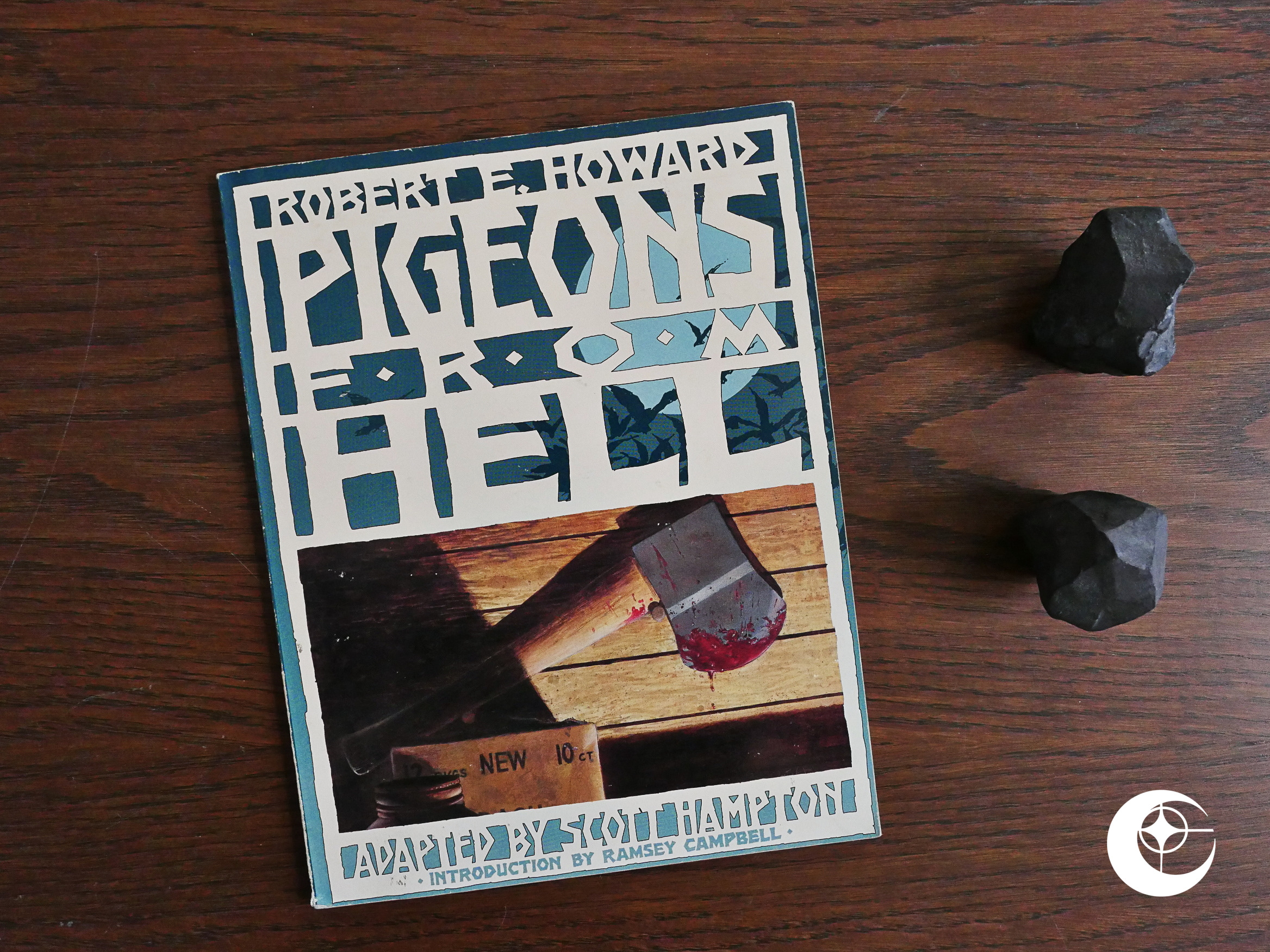

Into the Shadow of the Sun: Rael (1988) Pigeons from Hell (1988) #1

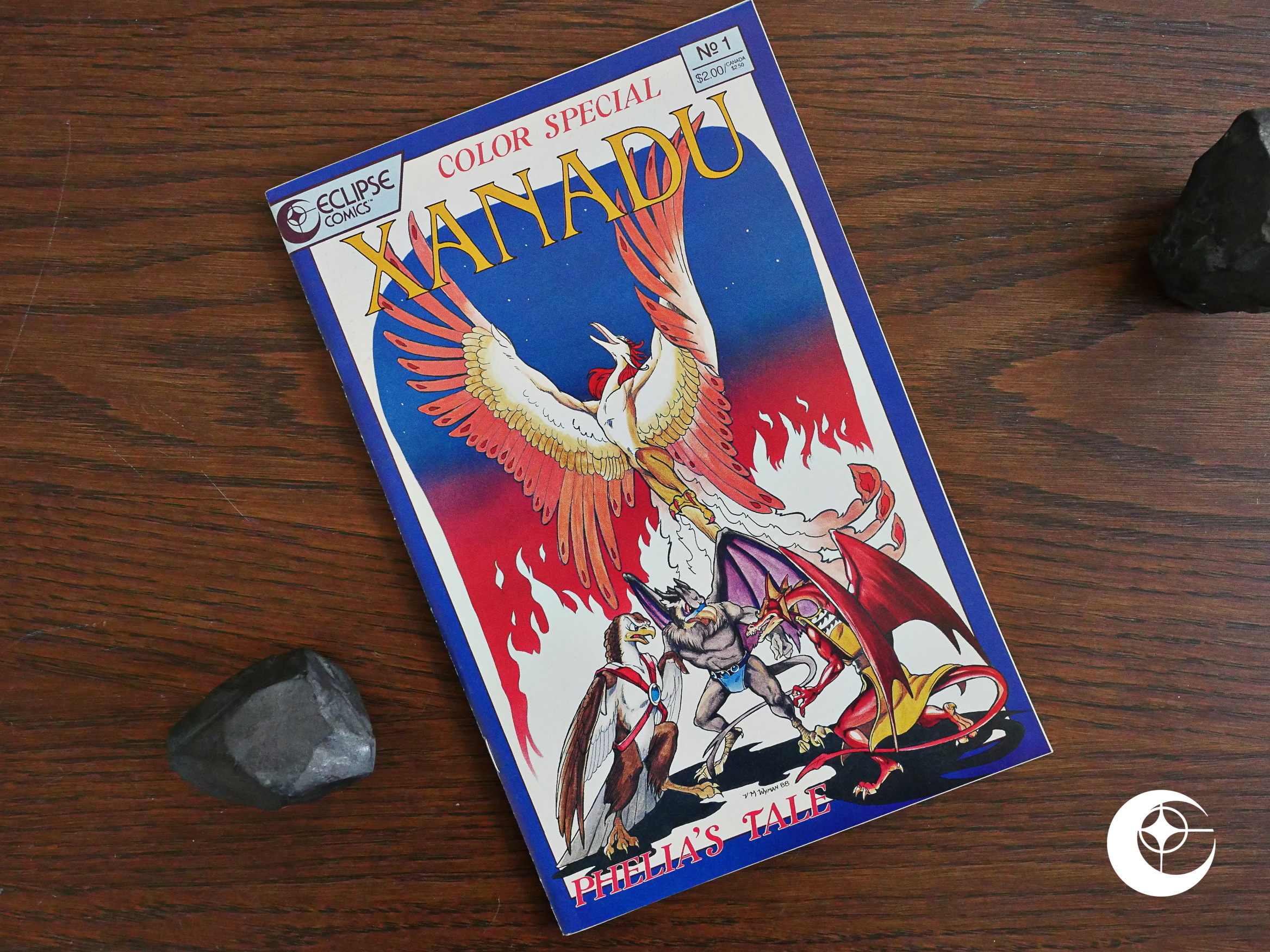

Pigeons from Hell (1988) #1 Xanadu Color Special (1988) #1

Xanadu Color Special (1988) #1 Dirty Pair (1988) #1-4

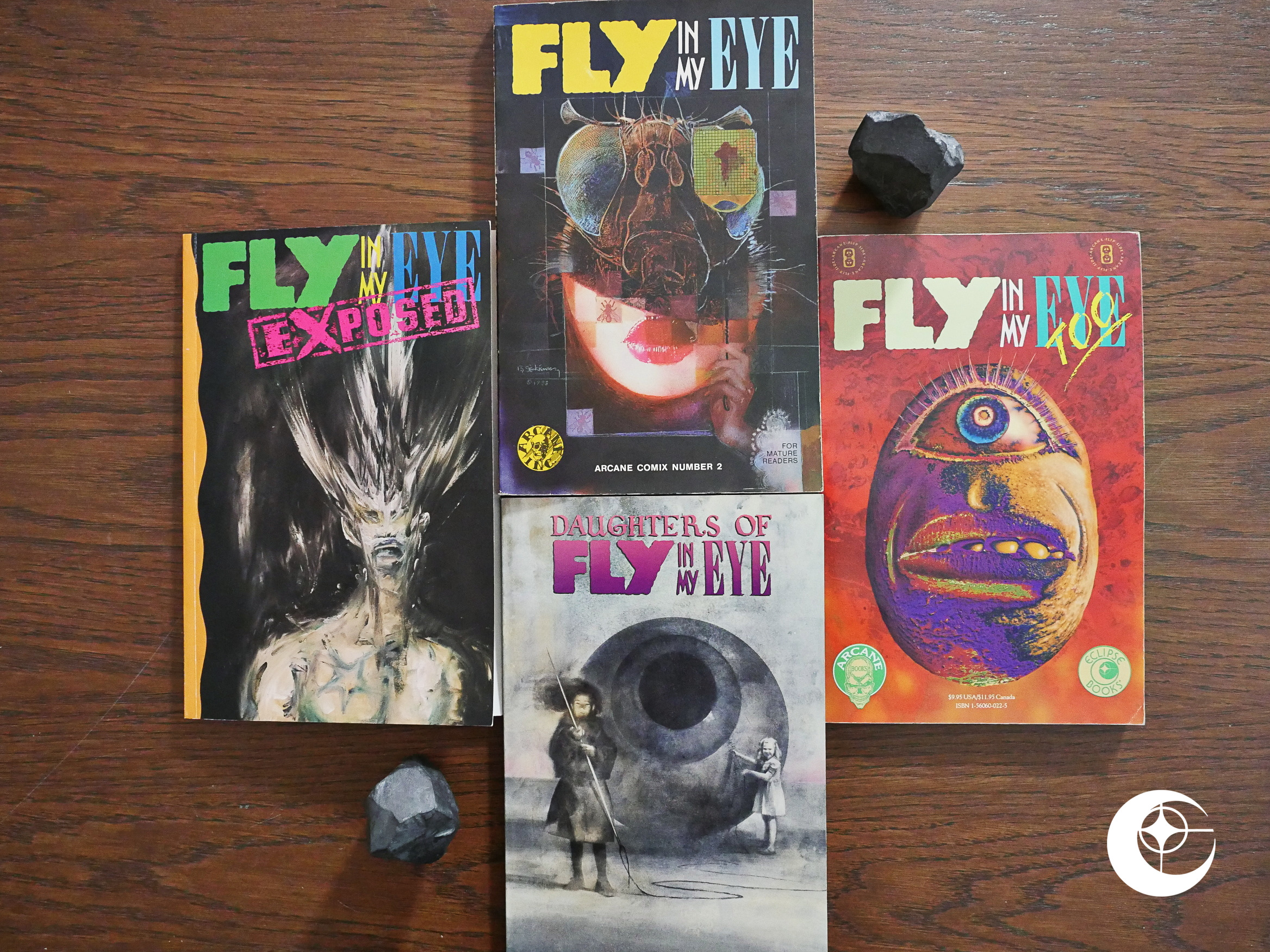

Dirty Pair (1988) #1-4 Fly in My Eye (1988)

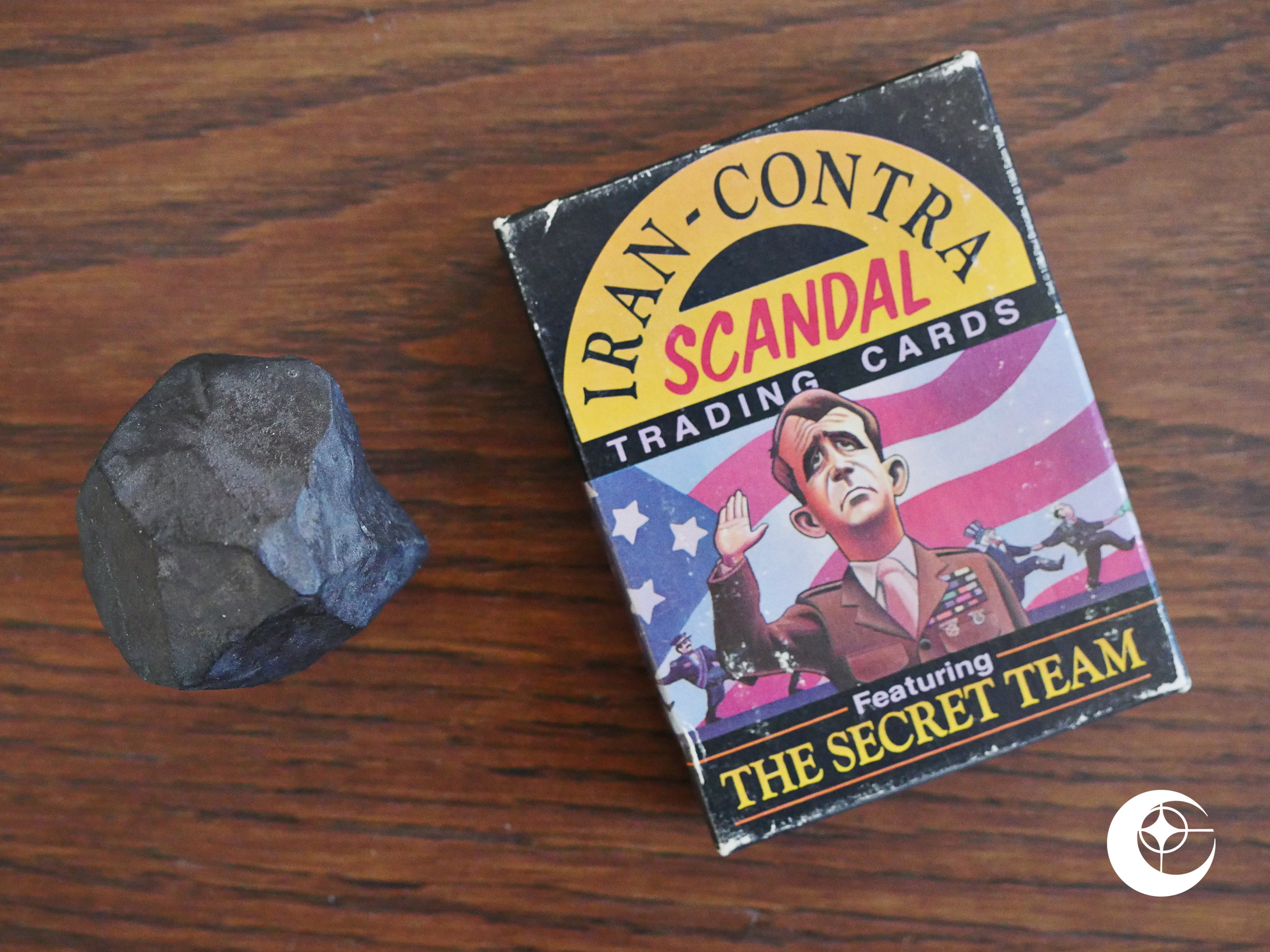

Fly in My Eye (1988) The Iran-Contra Scandal Trading Cards (1988)

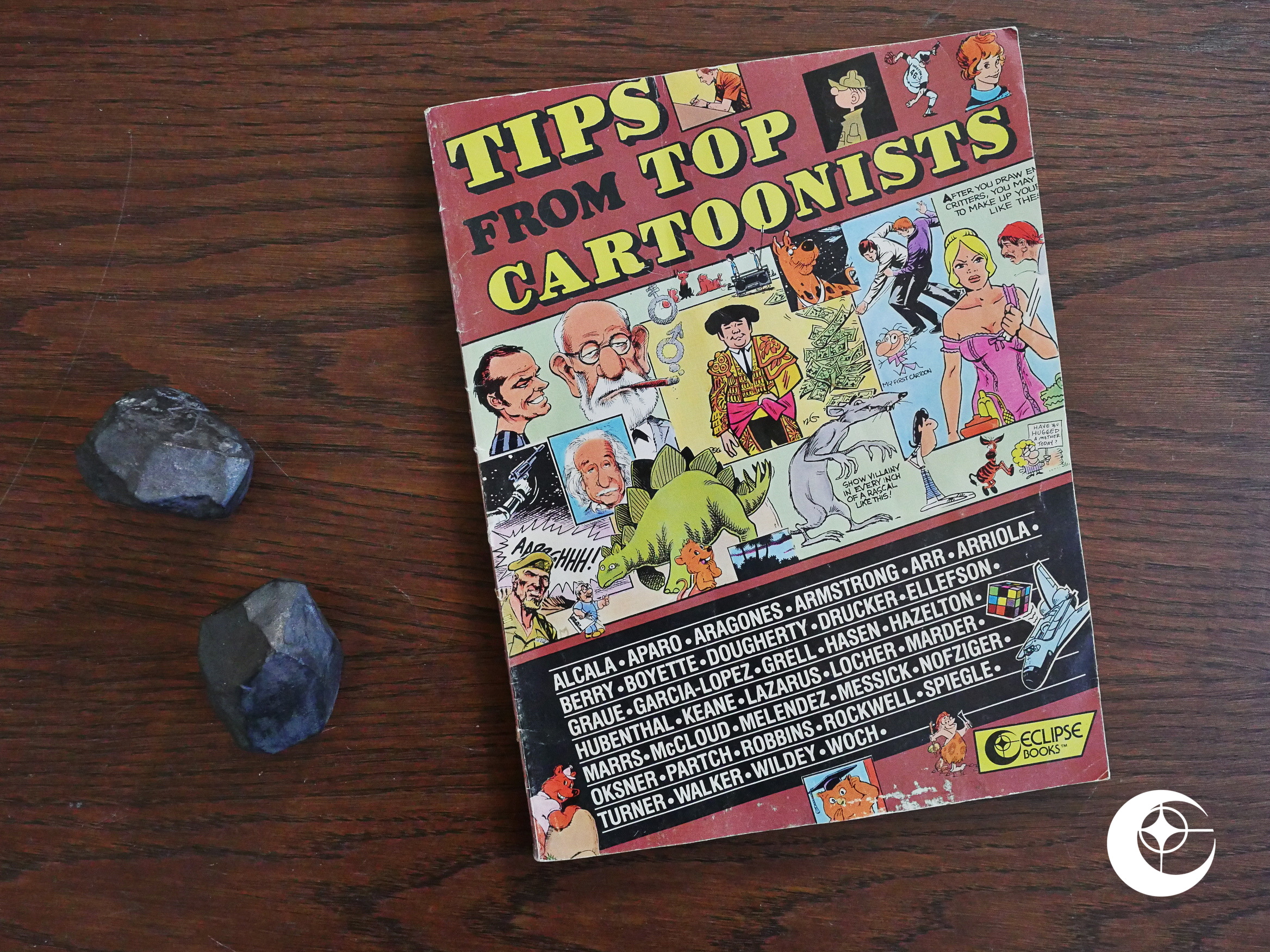

The Iran-Contra Scandal Trading Cards (1988) Tips from Top Cartoonists (1988)

Tips from Top Cartoonists (1988) Lil’ Grusome and the Nutshell Gang (1988)

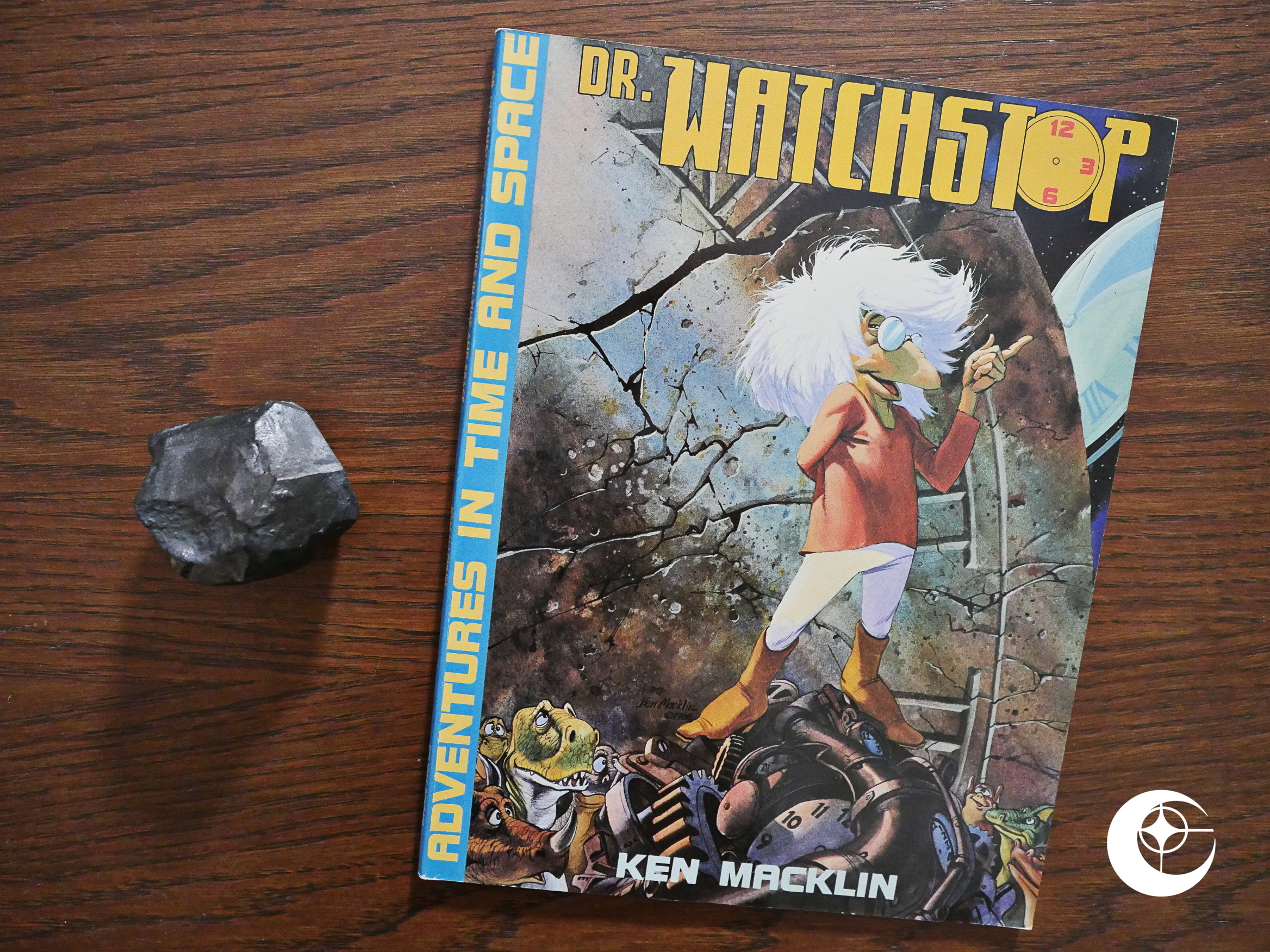

Lil’ Grusome and the Nutshell Gang (1988) Dr. Watchstop: Adventures in Time and Space (1989) #1

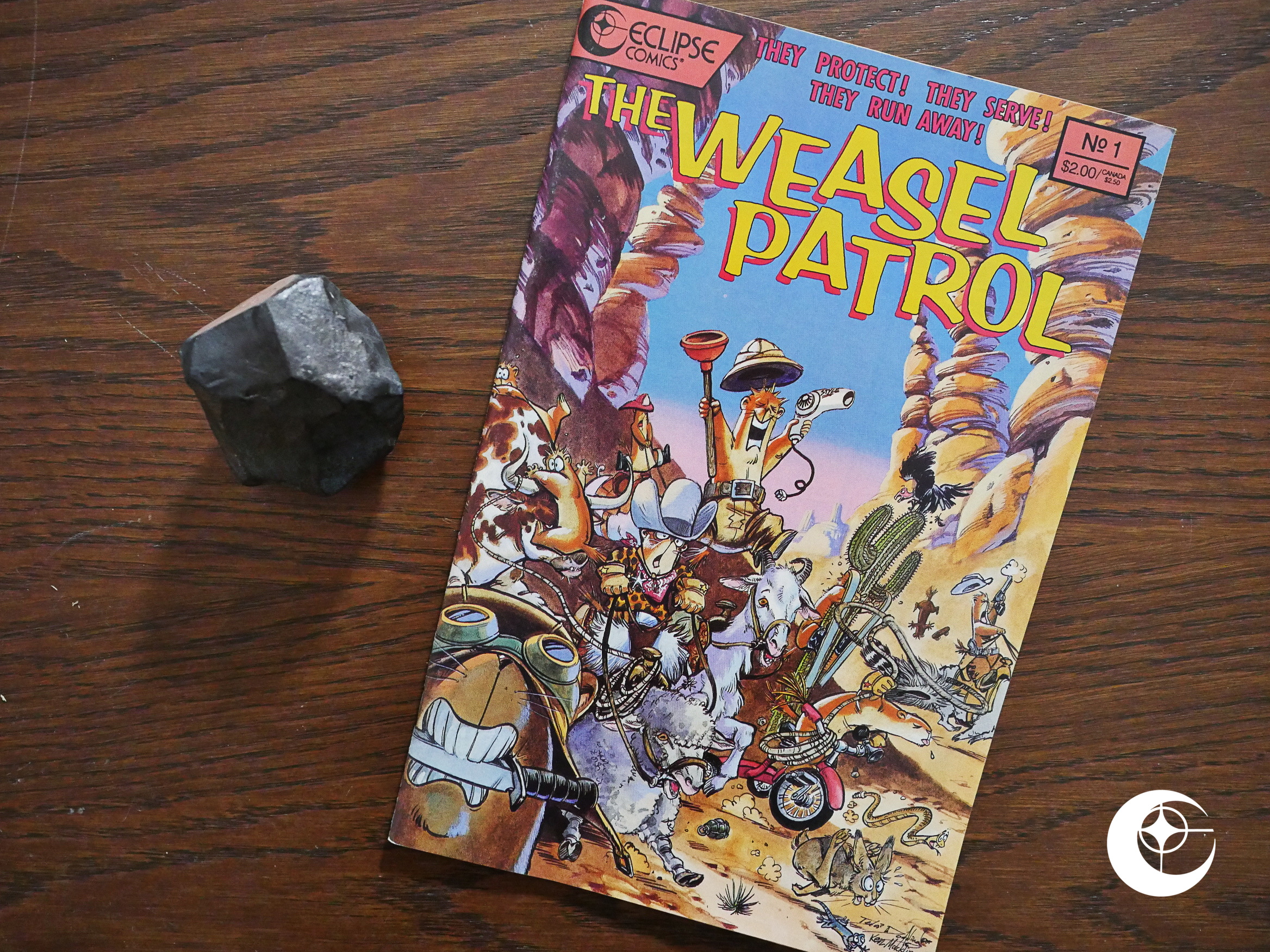

Dr. Watchstop: Adventures in Time and Space (1989) #1 Weasel Patrol (1989) #1

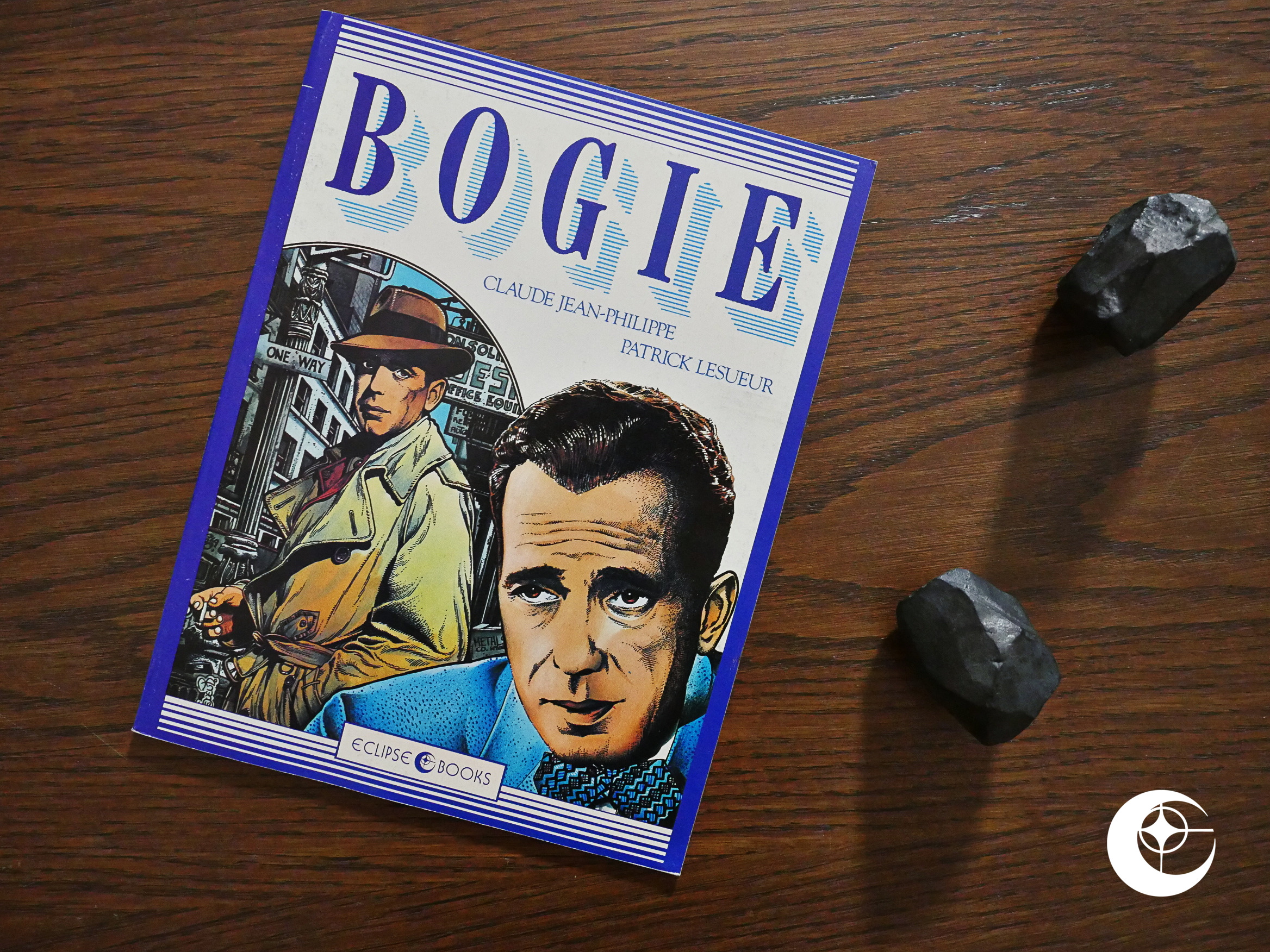

Weasel Patrol (1989) #1 Bogie (1989)

Bogie (1989) Brought to Light (1989) #1

Brought to Light (1989) #1 James Bond: Permission to Die (1989) #1-3

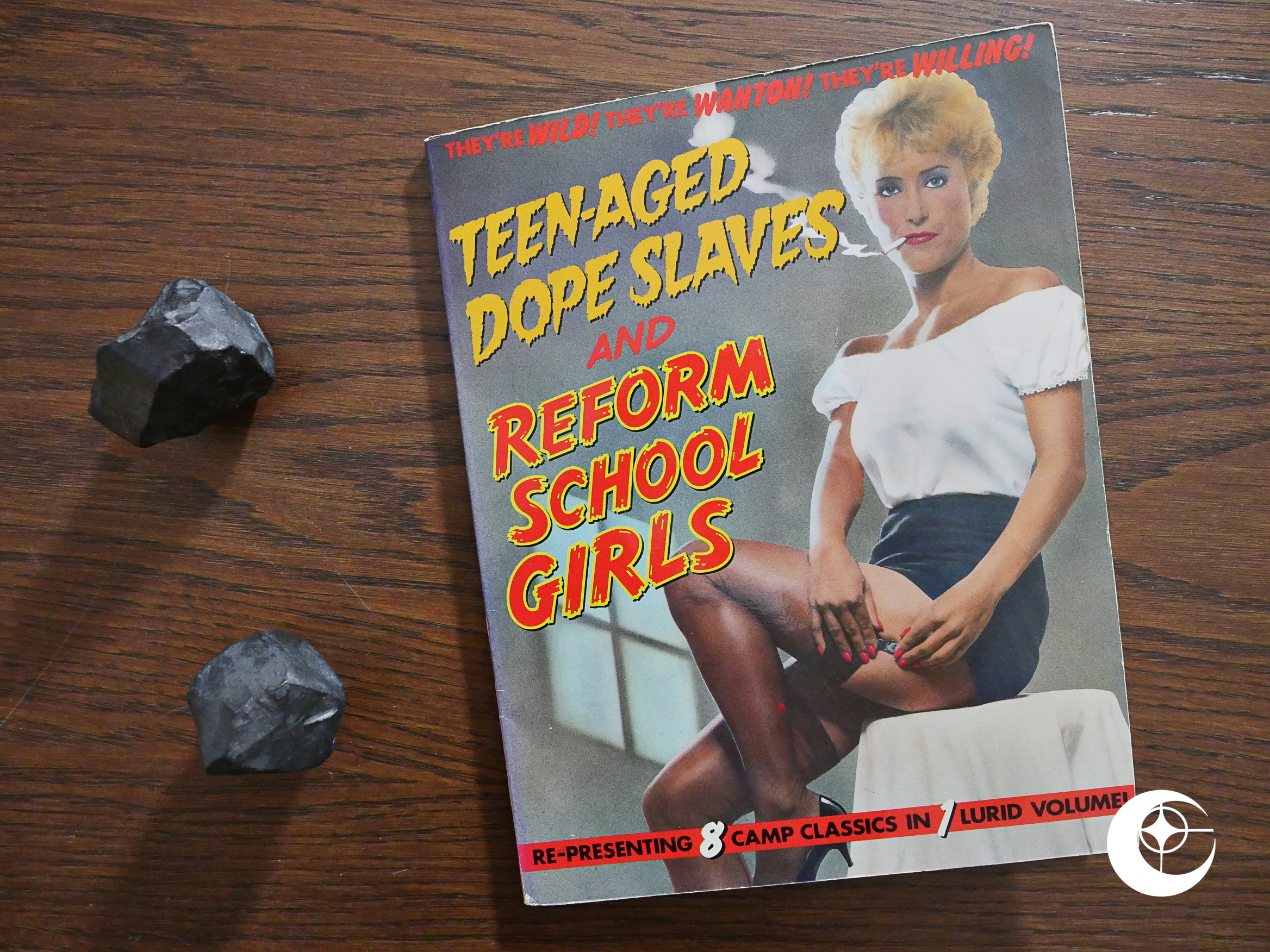

James Bond: Permission to Die (1989) #1-3 Teen-Aged Dope Slaves and Reform School Girls (1989)

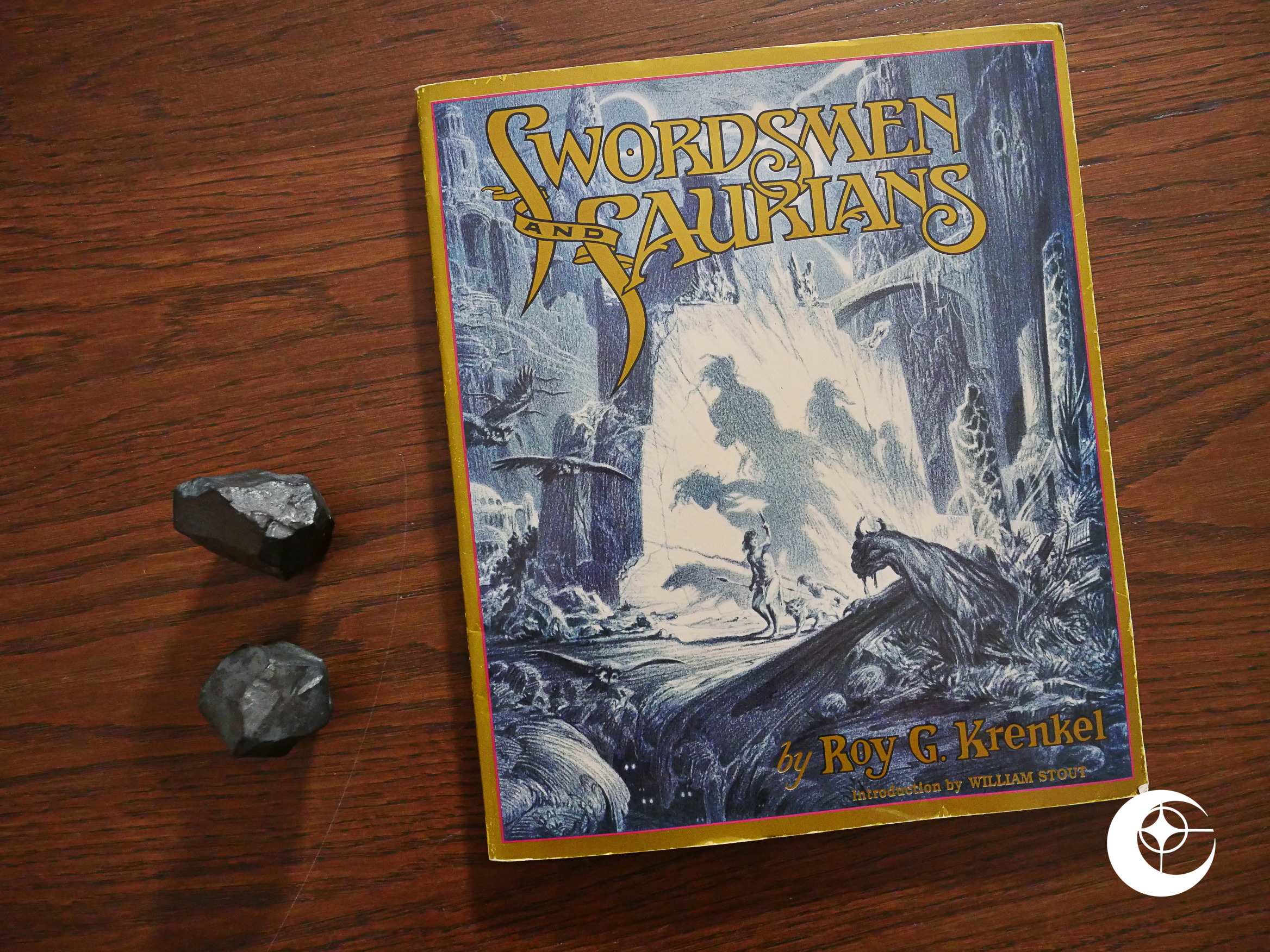

Teen-Aged Dope Slaves and Reform School Girls (1989) Swordsmen and Saurians (1989)

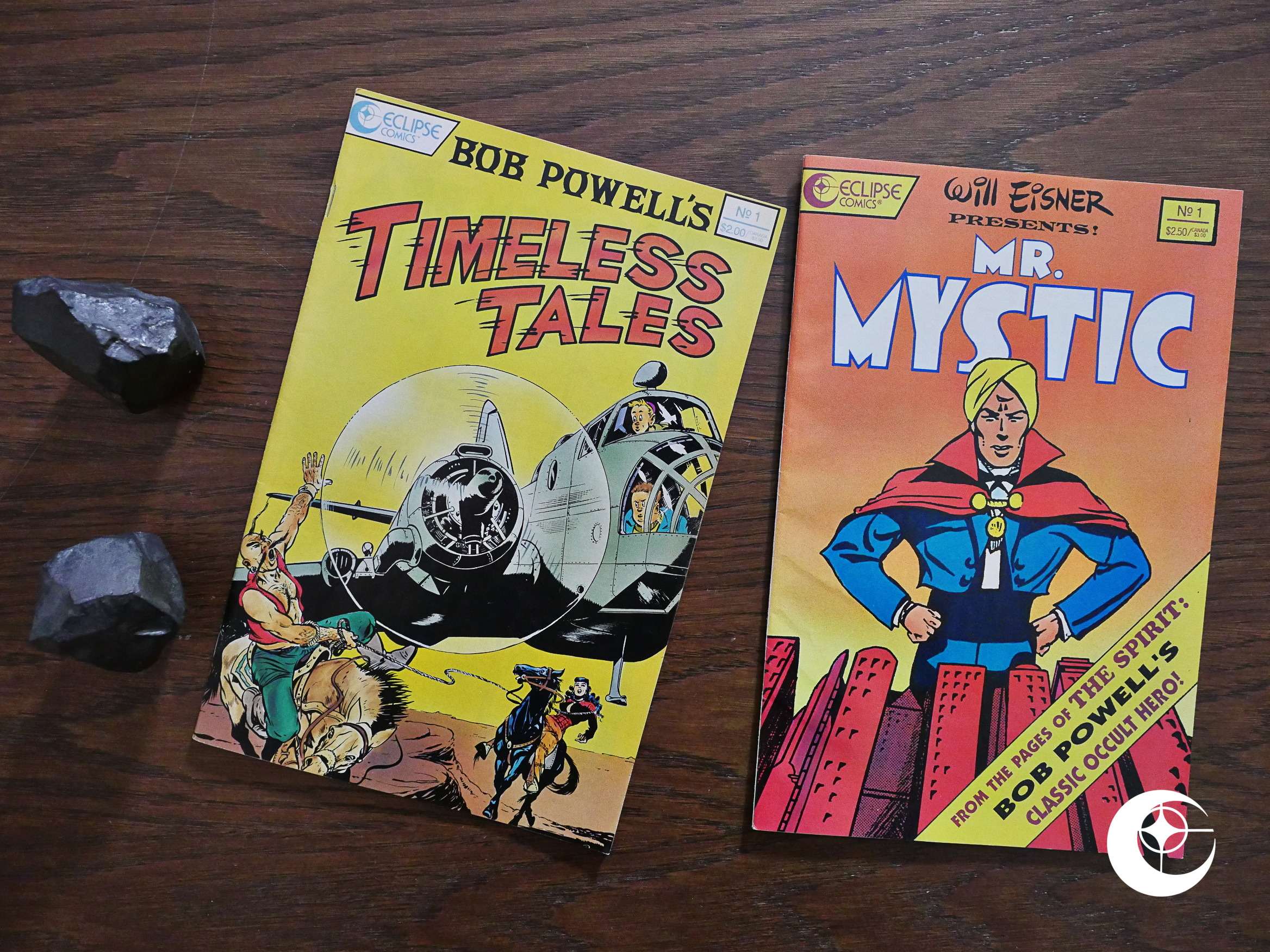

Swordsmen and Saurians (1989) Bob Powell’s Timeless Tales (1989) #1

Bob Powell’s Timeless Tales (1989) #1 Cyber 7 (1989) #1-7

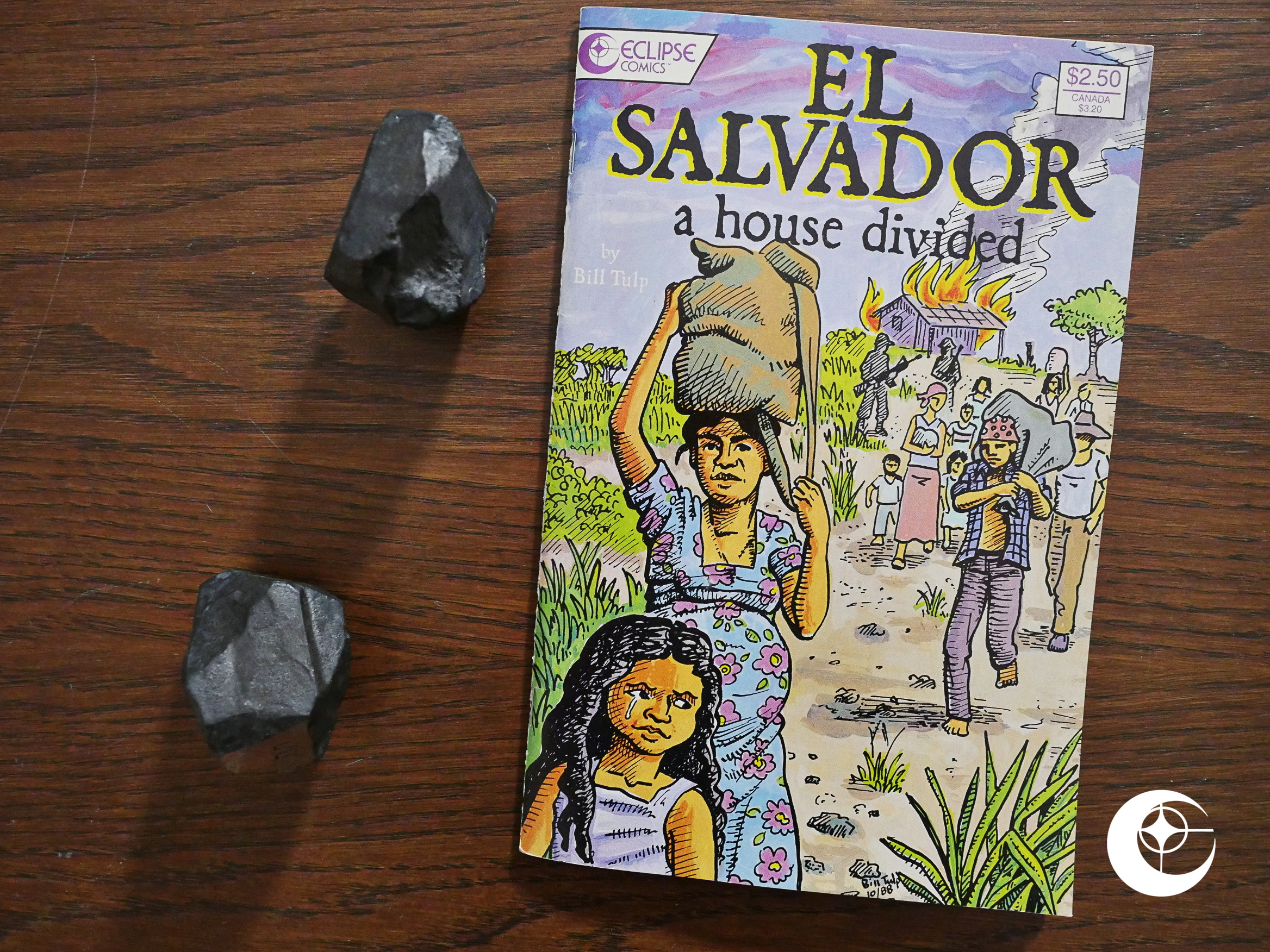

Cyber 7 (1989) #1-7 El Salvador: A House Divided (1989)

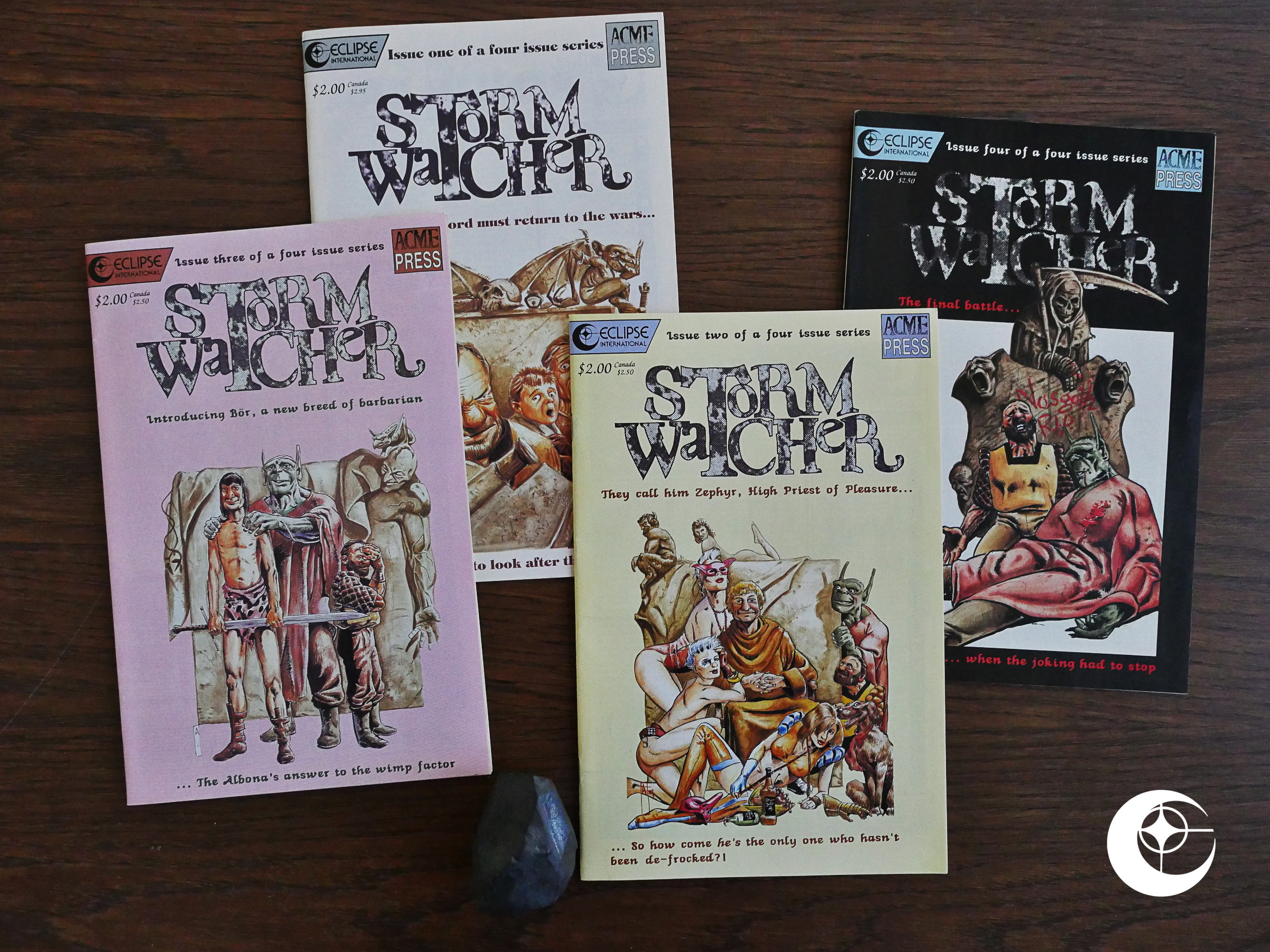

El Salvador: A House Divided (1989) Stormwatcher (1989) #1-4

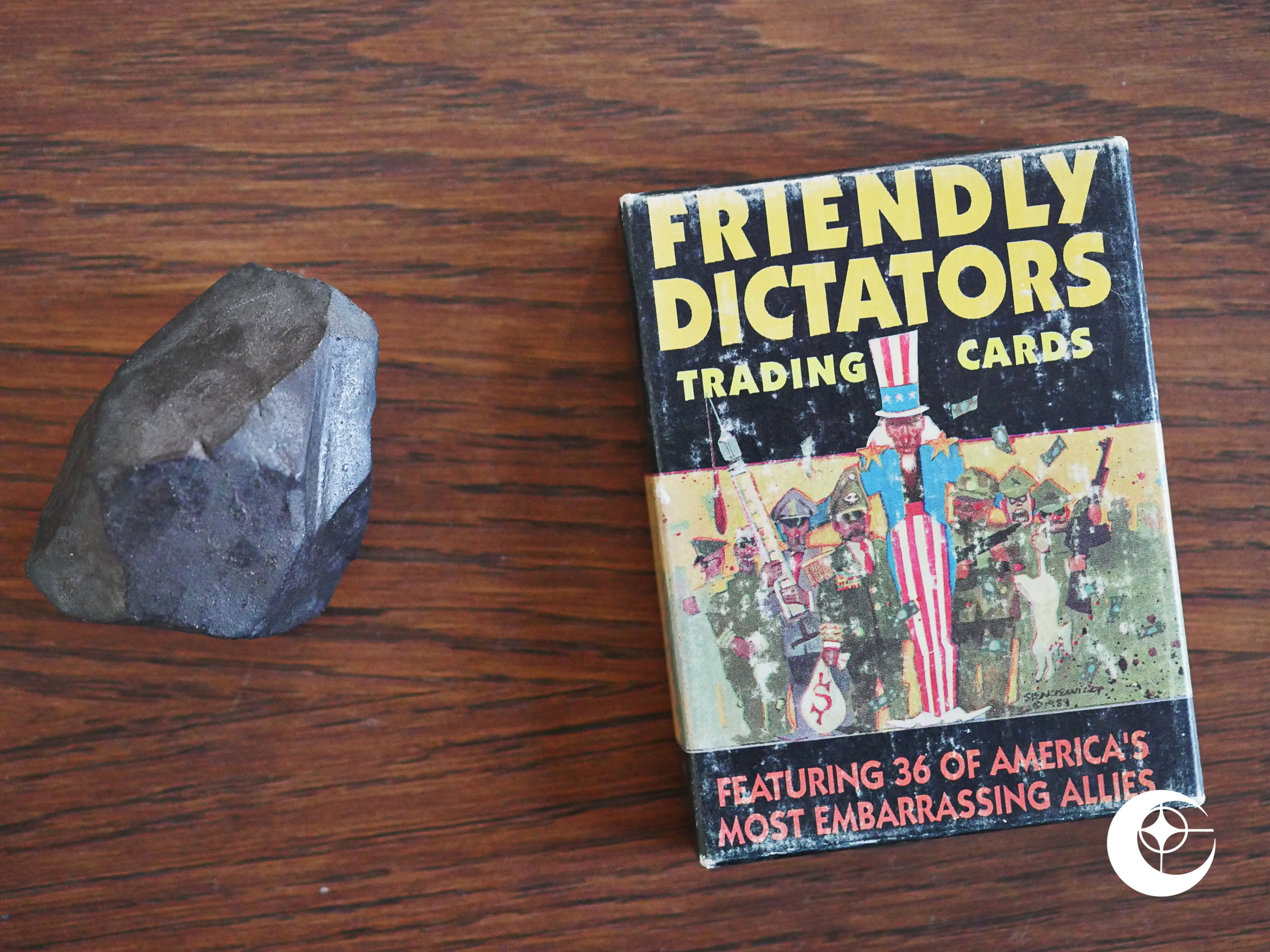

Stormwatcher (1989) #1-4 Friendly Dictators Trading Cards (1989) #1

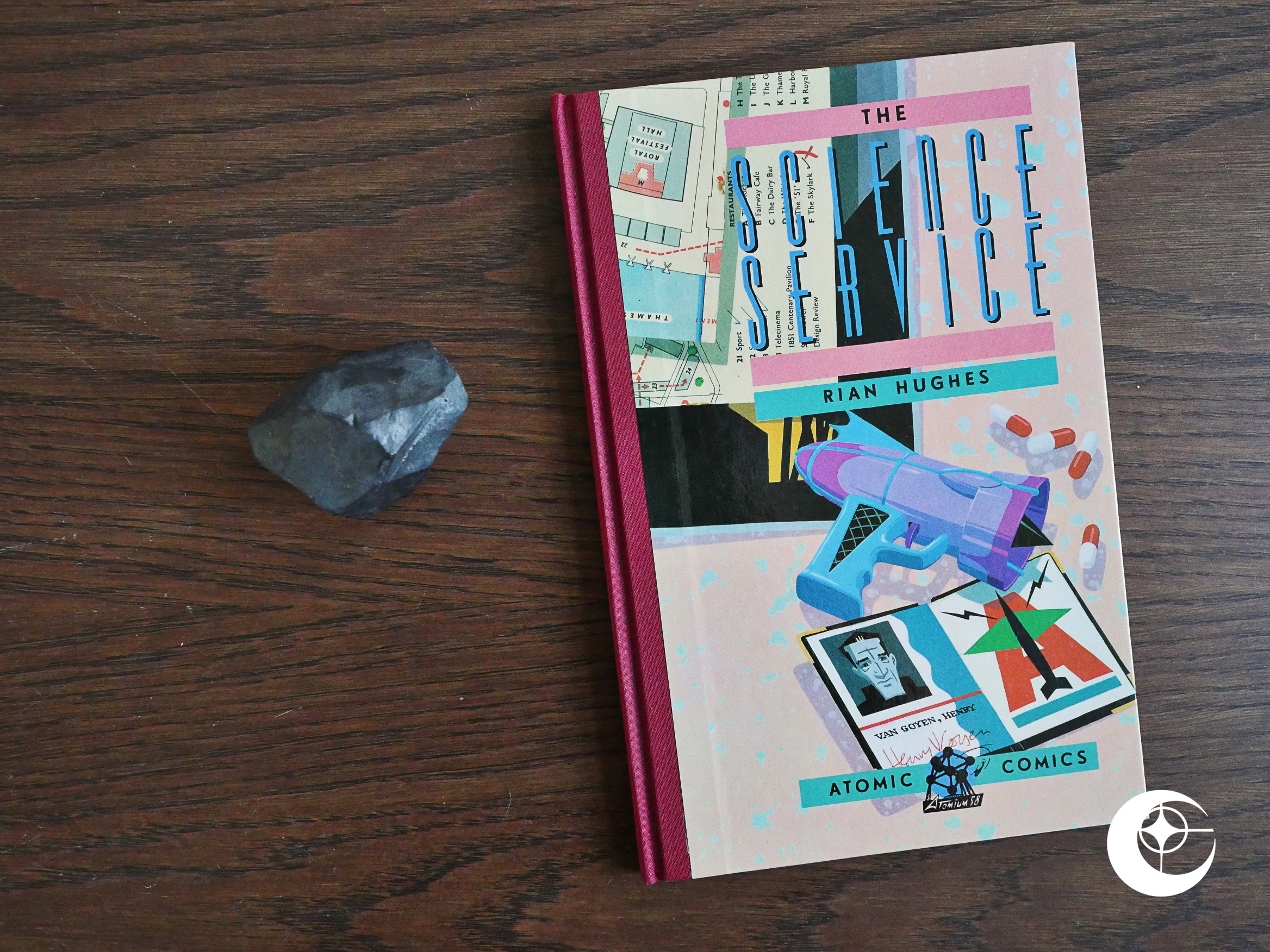

Friendly Dictators Trading Cards (1989) #1 The Science Service (1989)

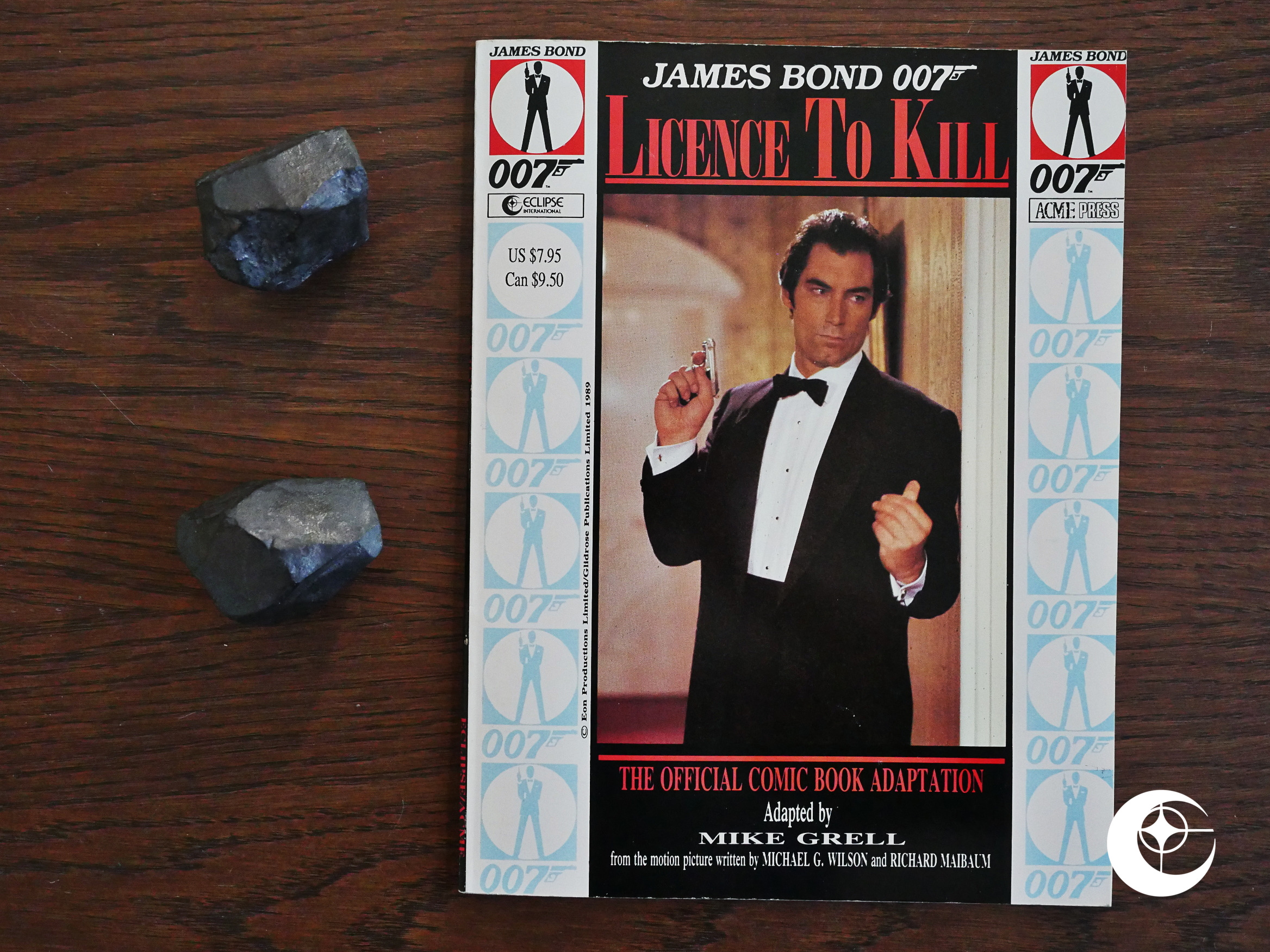

The Science Service (1989) James Bond 007: Licence to Kill (1989)

James Bond 007: Licence to Kill (1989) The Hobbit (1989) #1-3

The Hobbit (1989) #1-3 Tapping the Vein (1989) #1-5

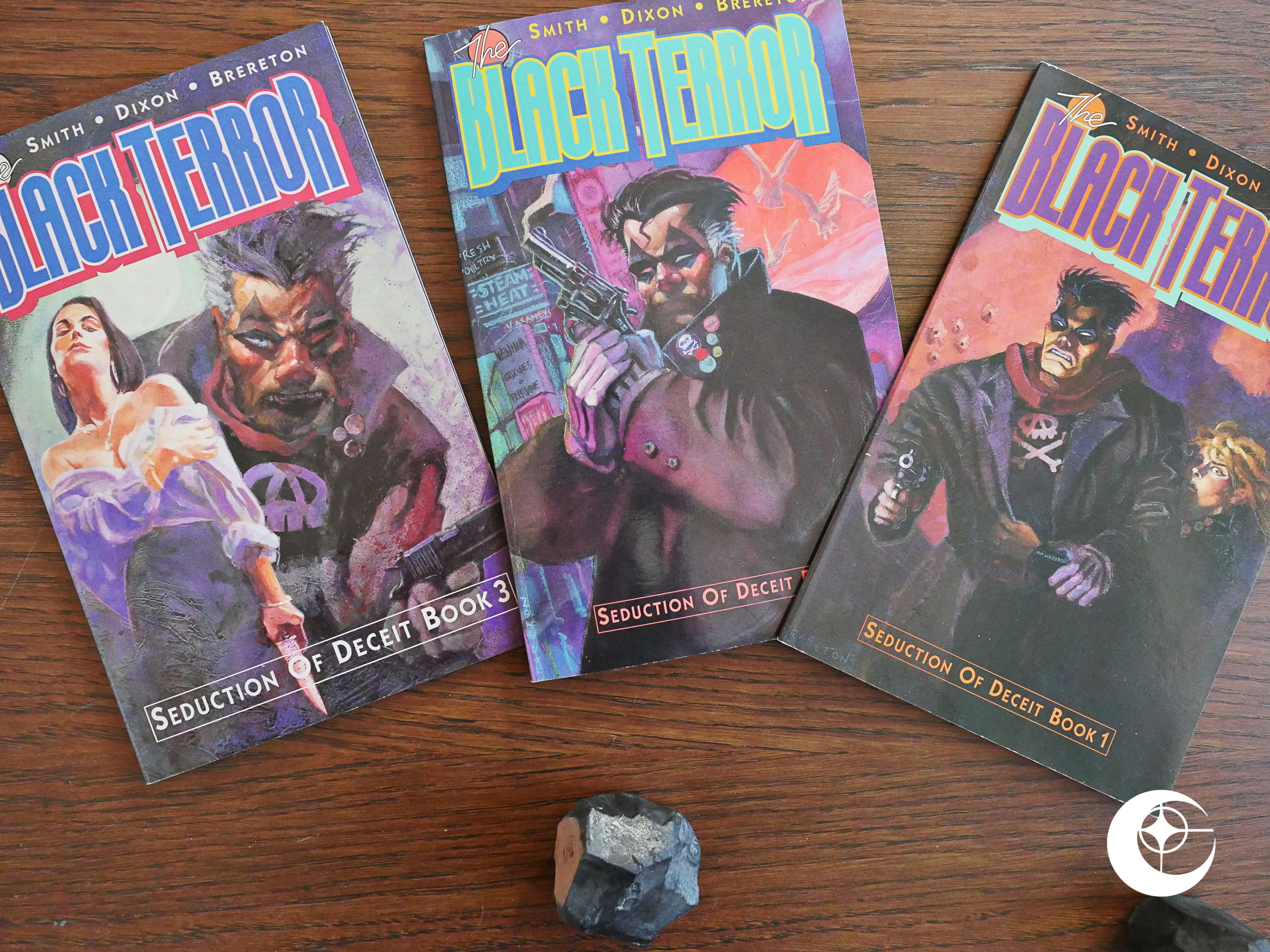

Tapping the Vein (1989) #1-5 The Black Terror (1989) #1-3

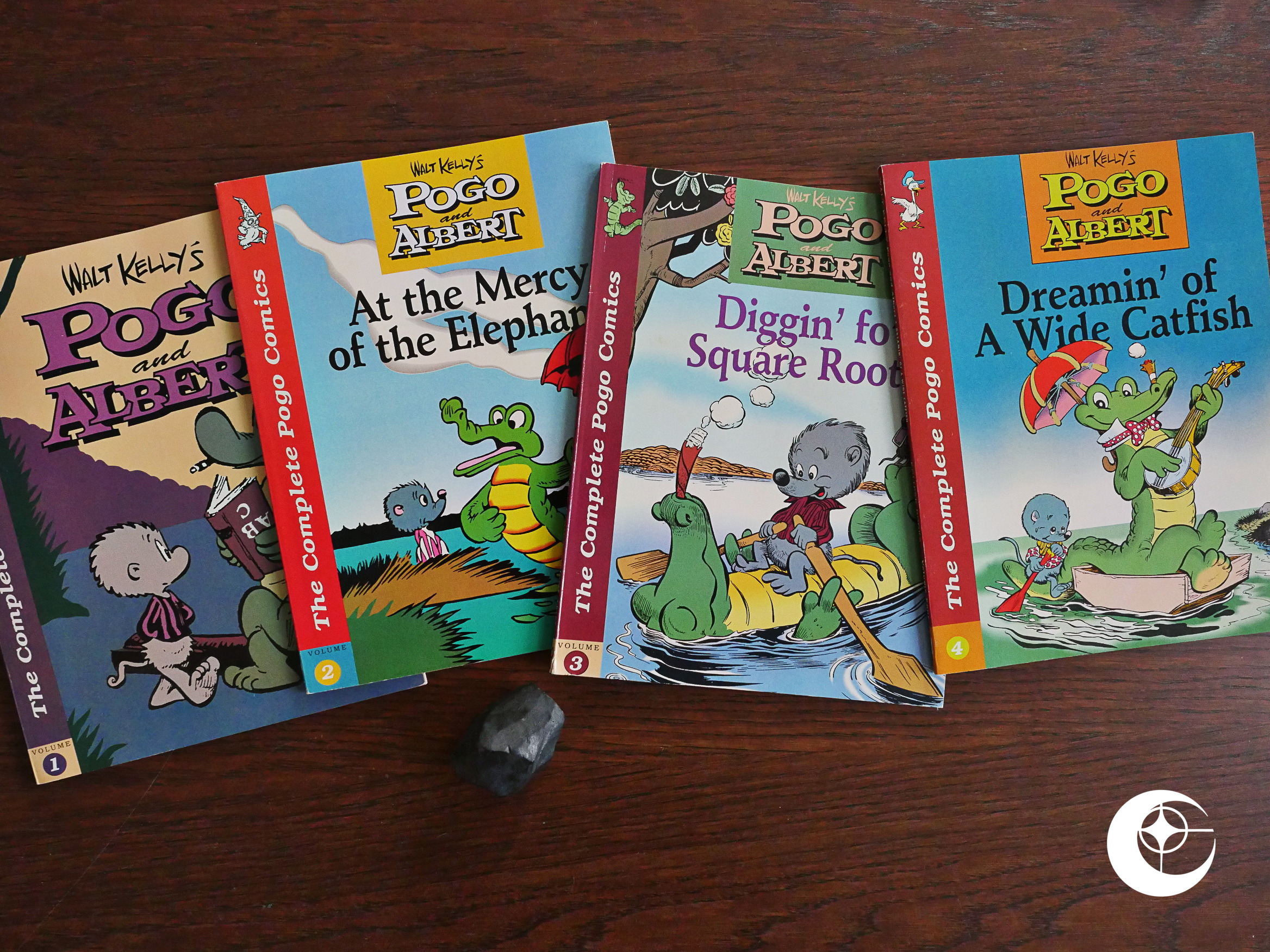

The Black Terror (1989) #1-3 The Complete Pogo Comics (1989) #1-4

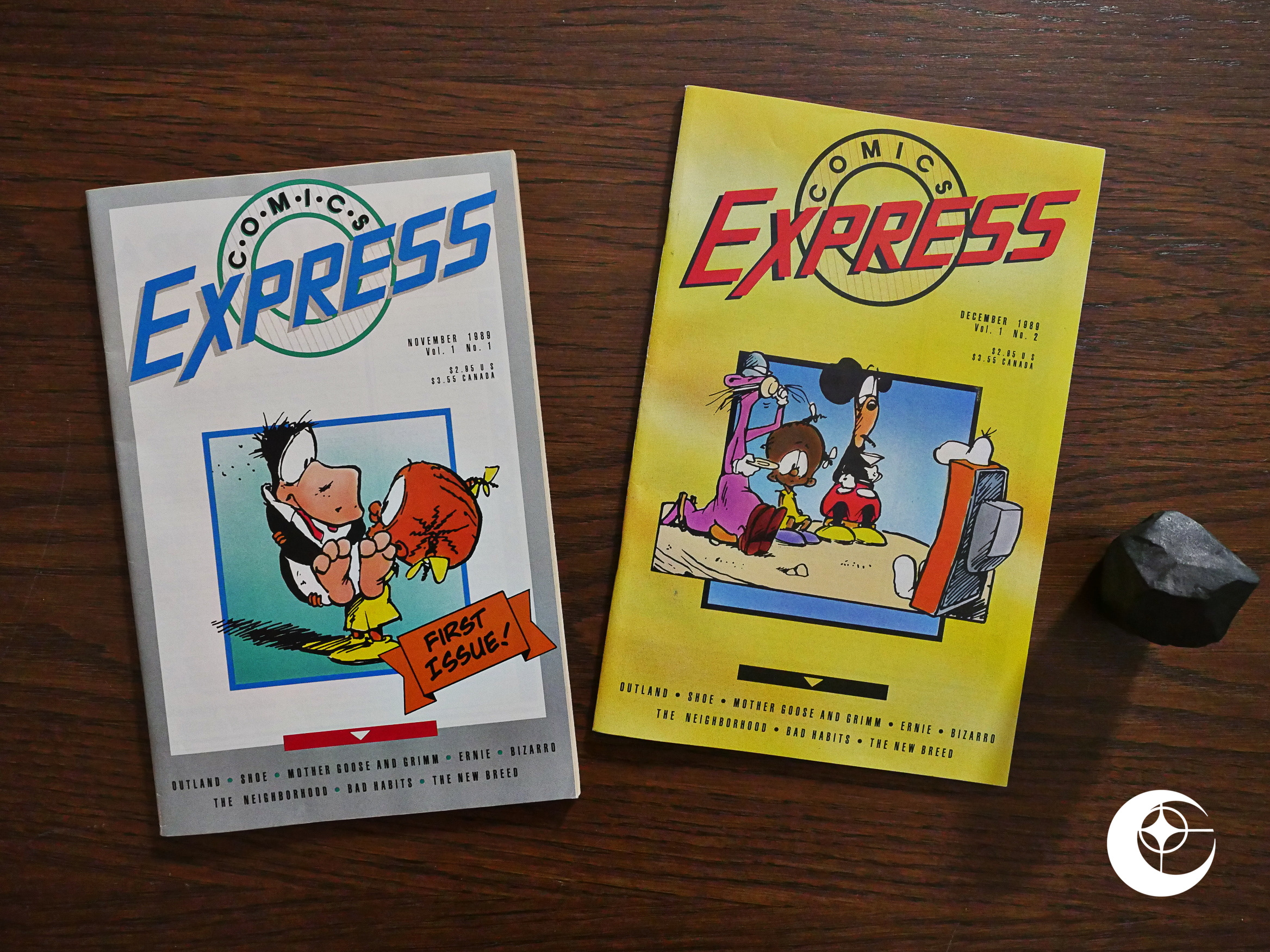

The Complete Pogo Comics (1989) #1-4 Comics Express (1989) #1-2

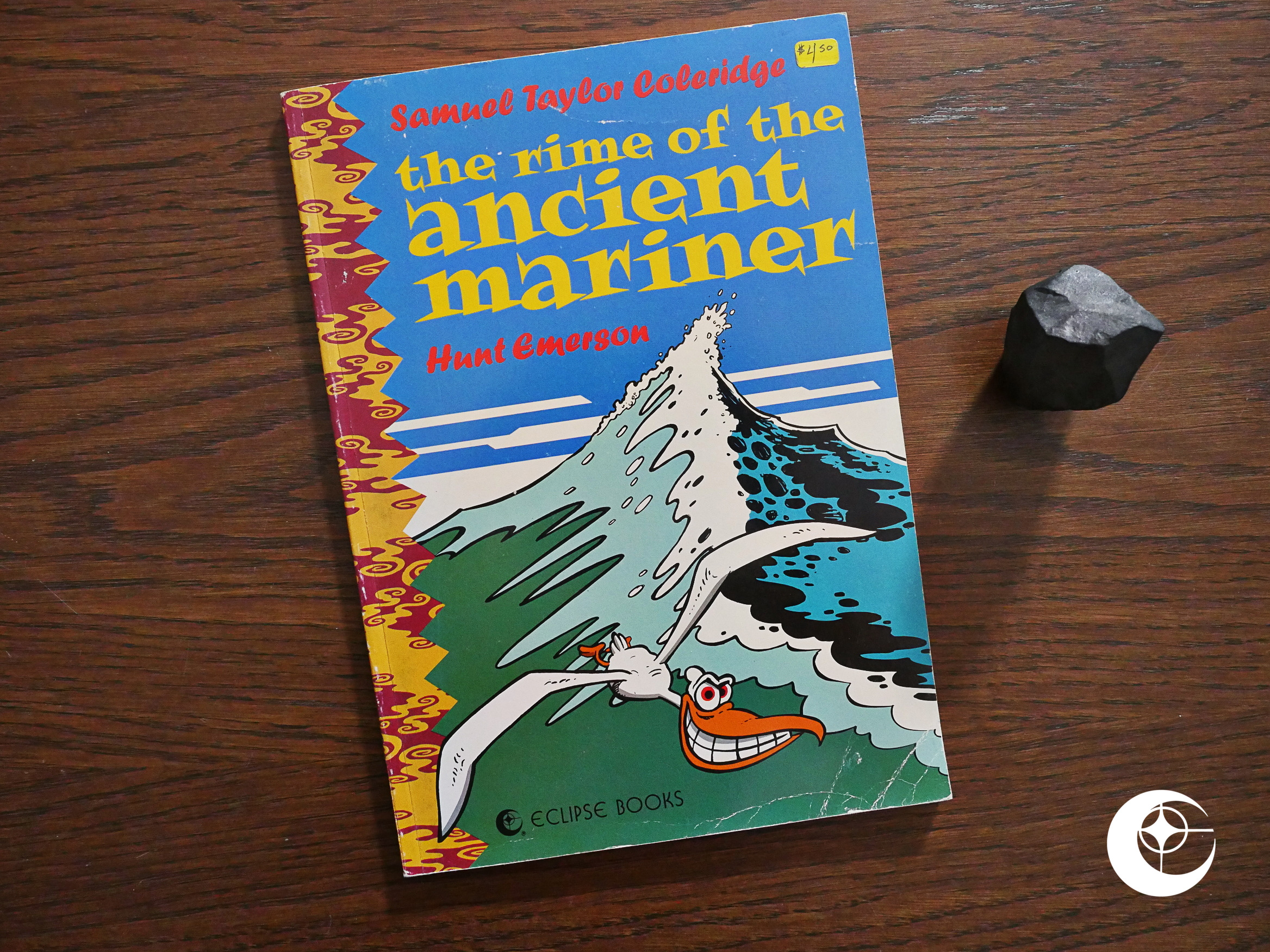

Comics Express (1989) #1-2 The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1989)

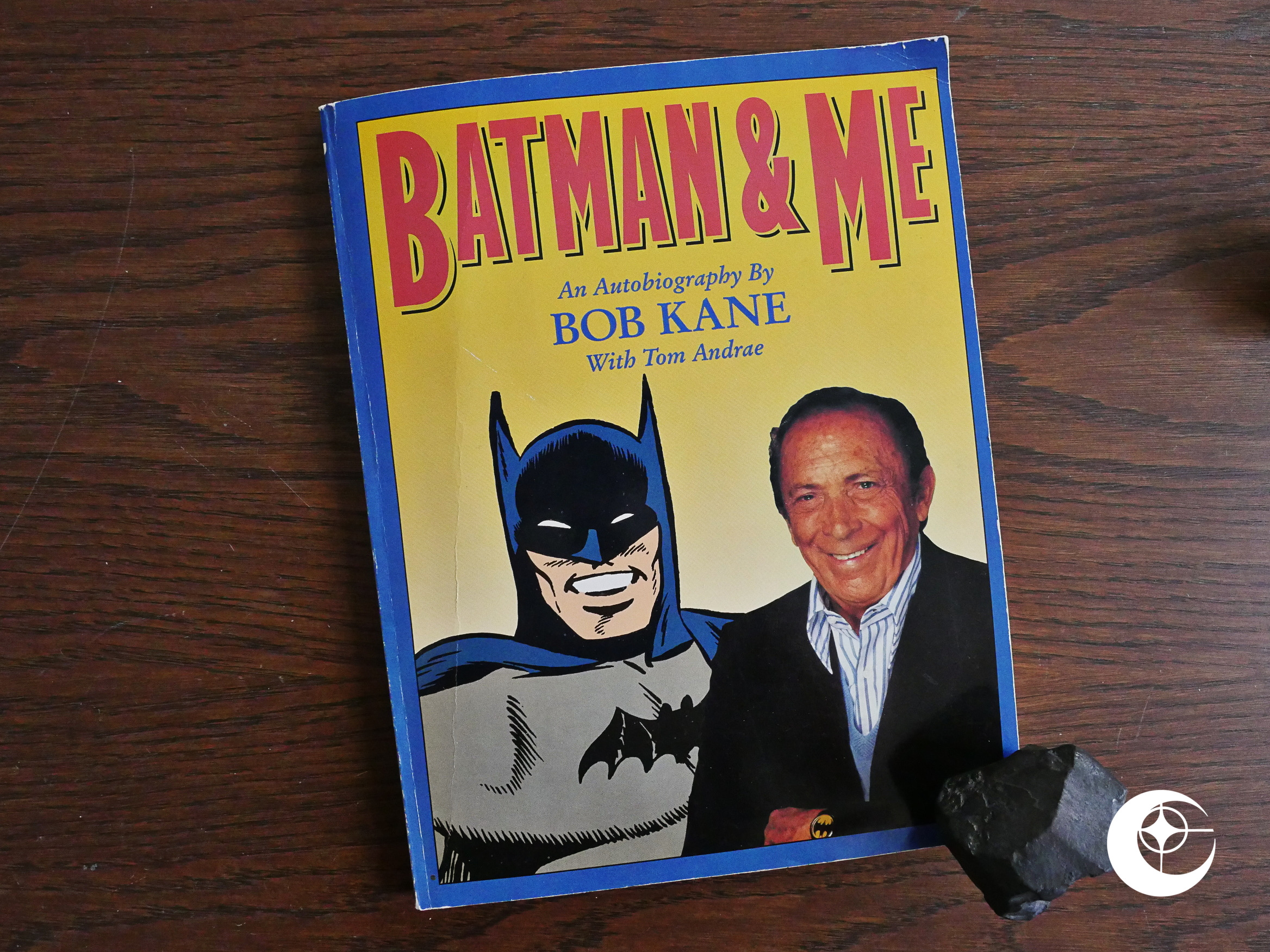

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1989) Batman & Me (1989)

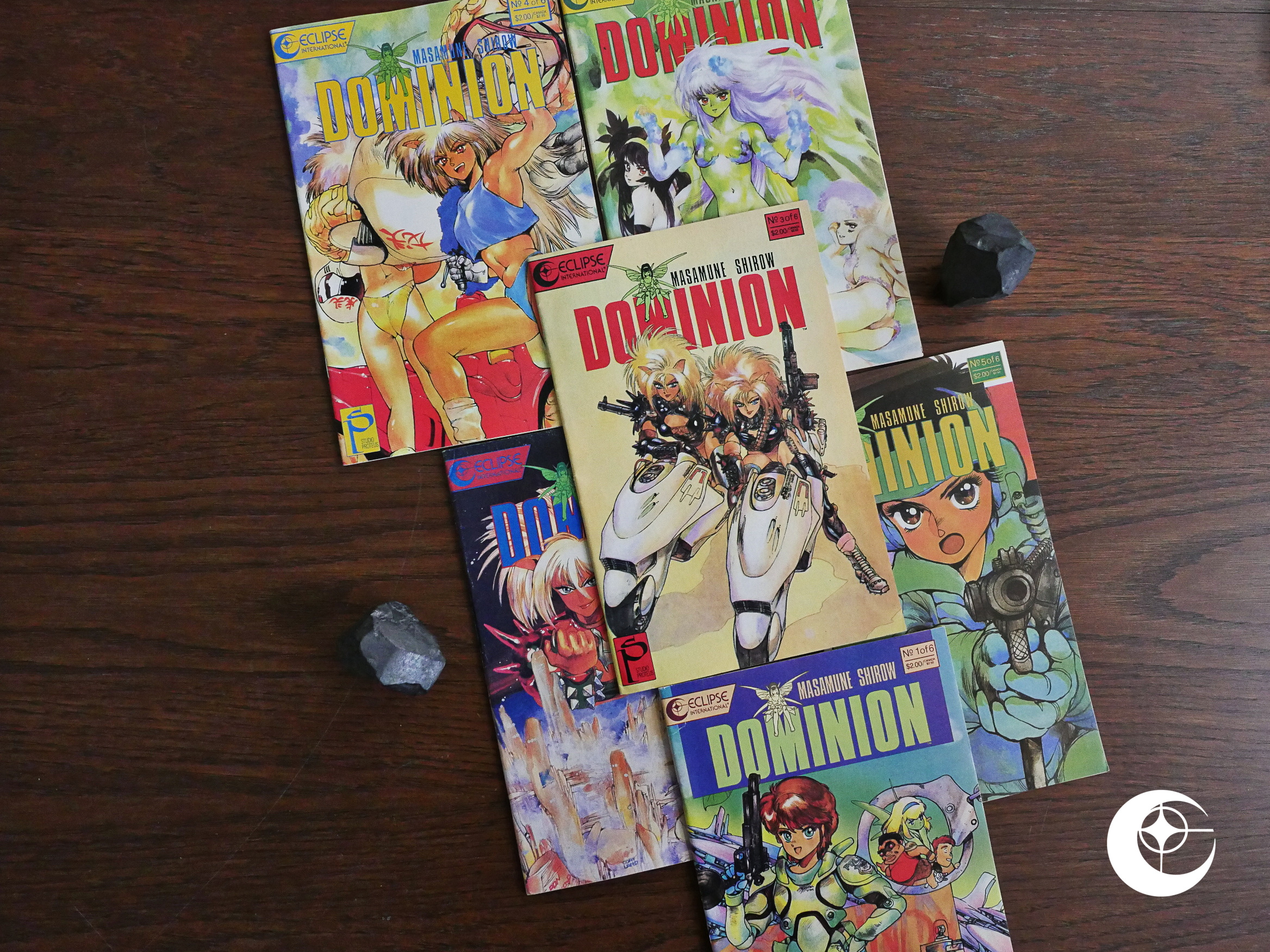

Batman & Me (1989) Dominion (1989) #1-6

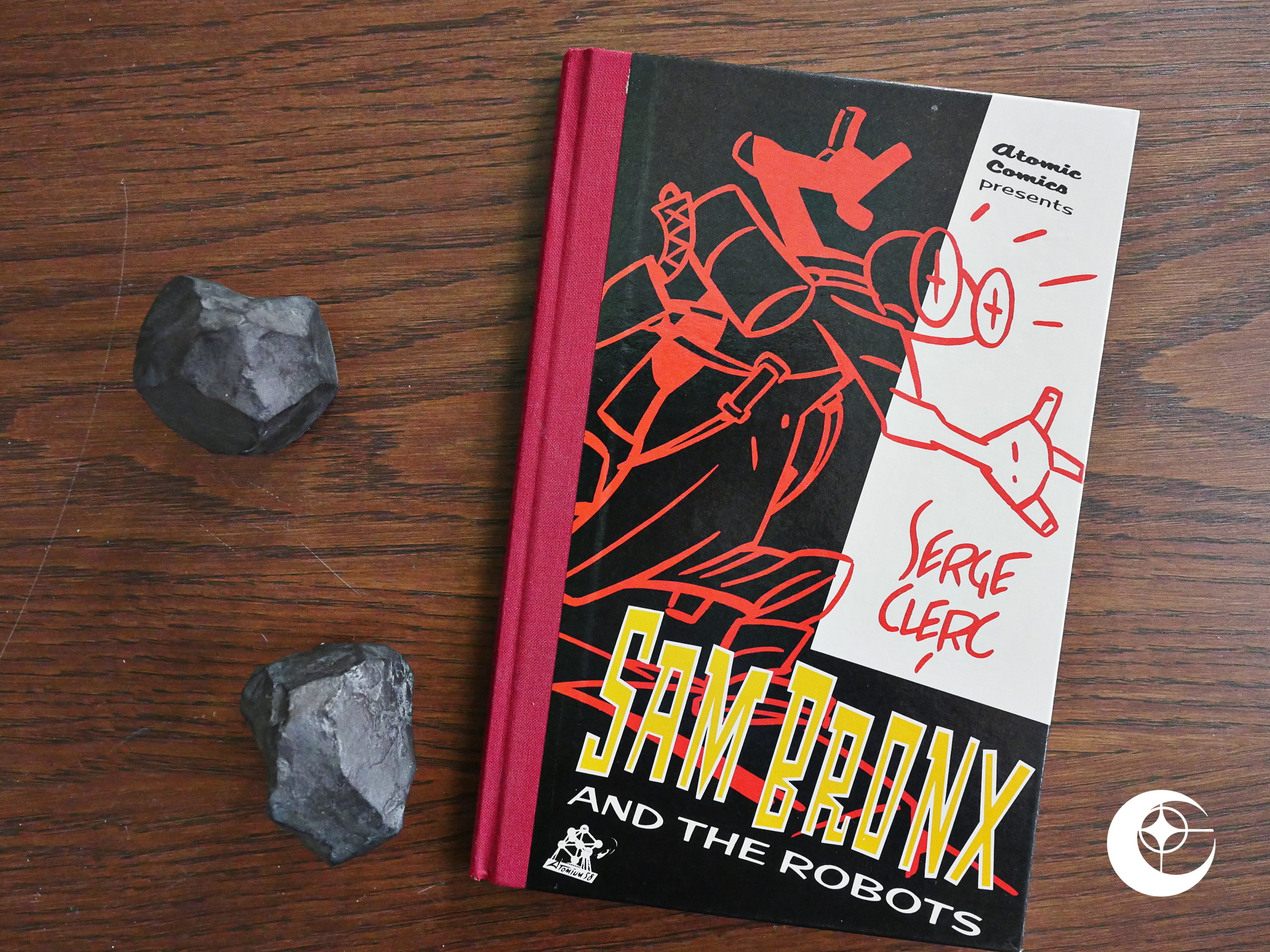

Dominion (1989) #1-6 Sam Bronx and the Robots (1989)

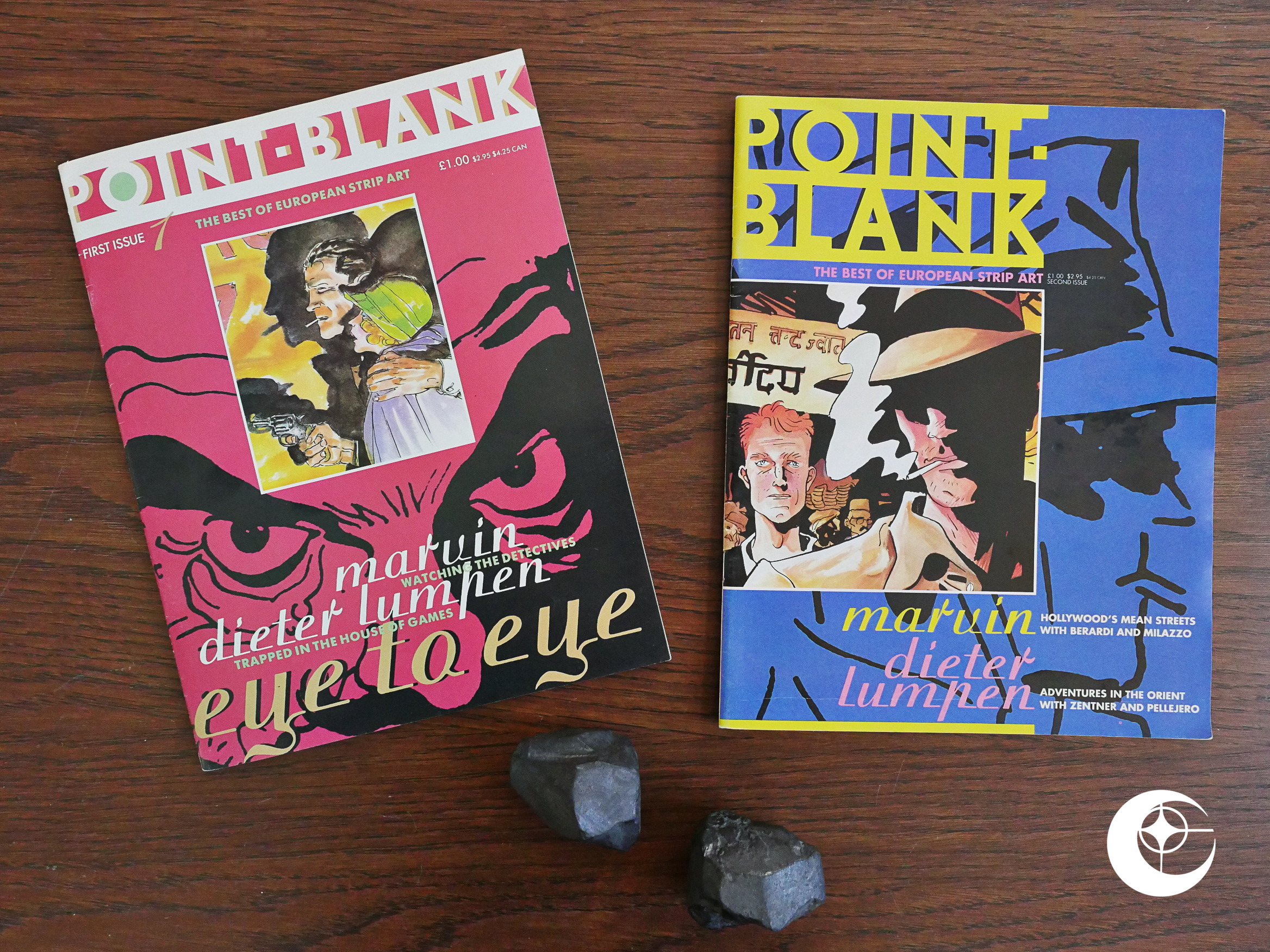

Sam Bronx and the Robots (1989) Point Blank (1989) #1-2

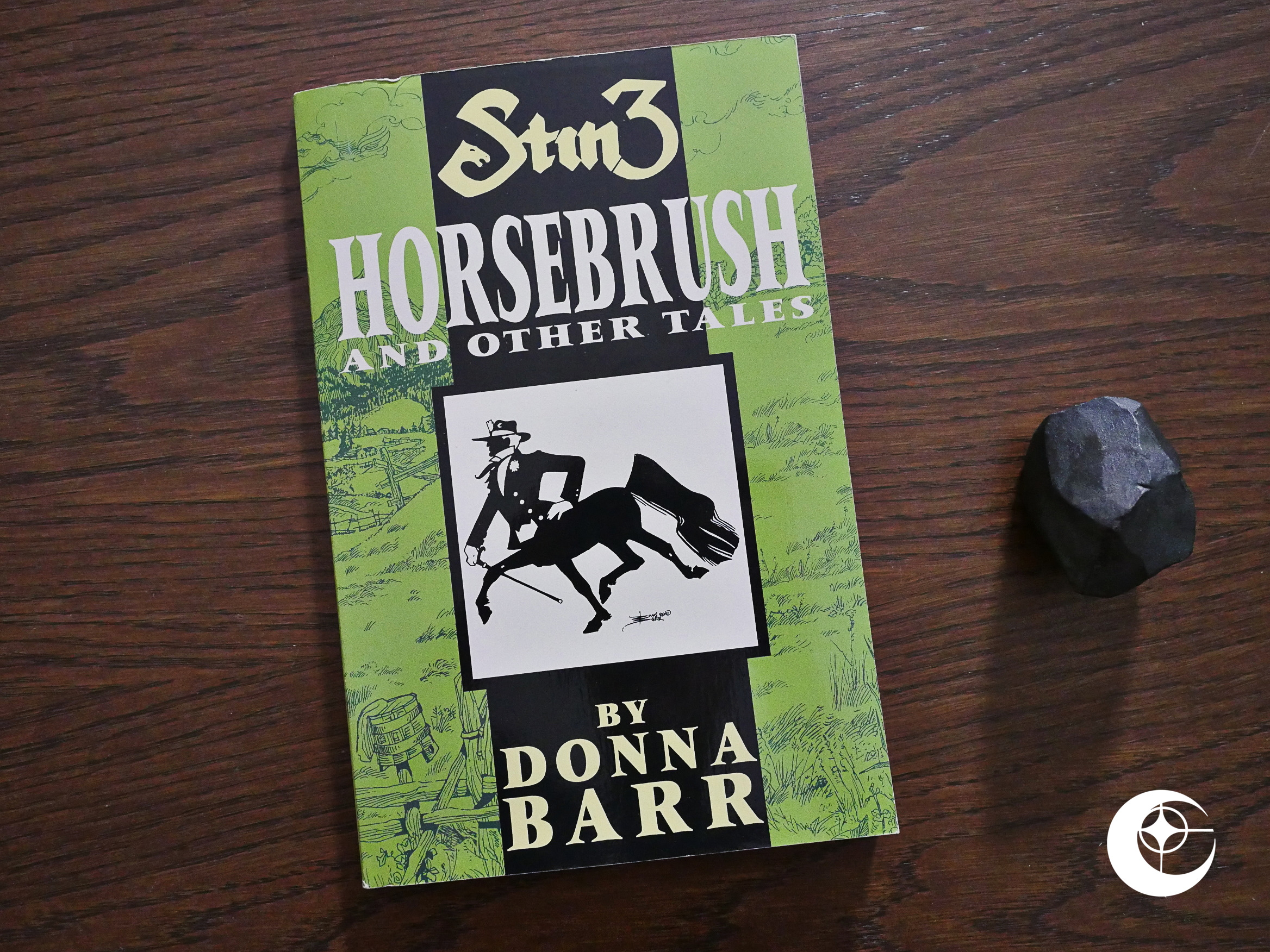

Point Blank (1989) #1-2 Stinz: Horsebrush and Other Tales (1990) #1

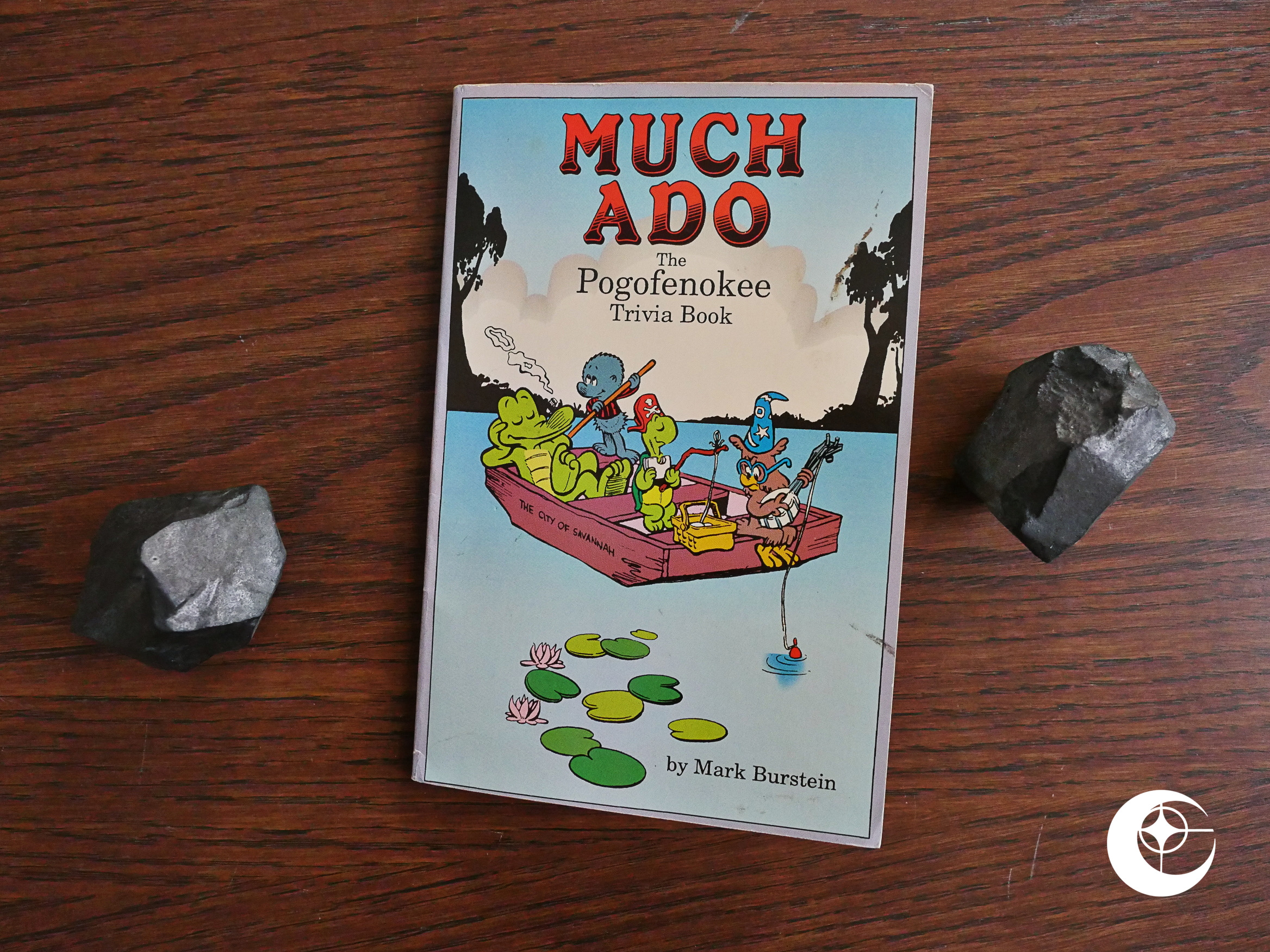

Stinz: Horsebrush and Other Tales (1990) #1 by Walt Kelly, Much Ado: The Pogofenokee Trivia Book (1990)

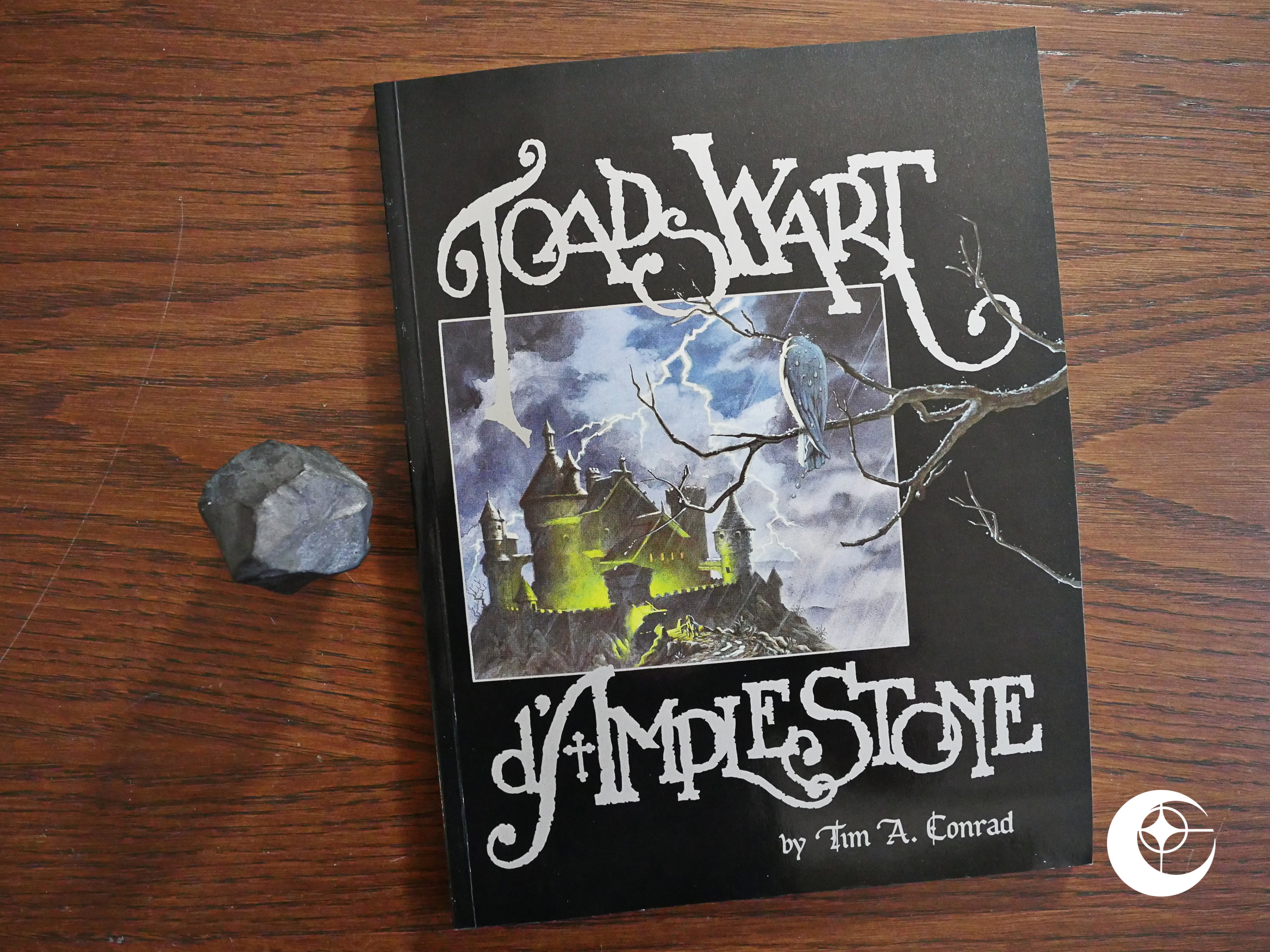

by Walt Kelly, Much Ado: The Pogofenokee Trivia Book (1990) Toadswart D’Amplestone (1990)

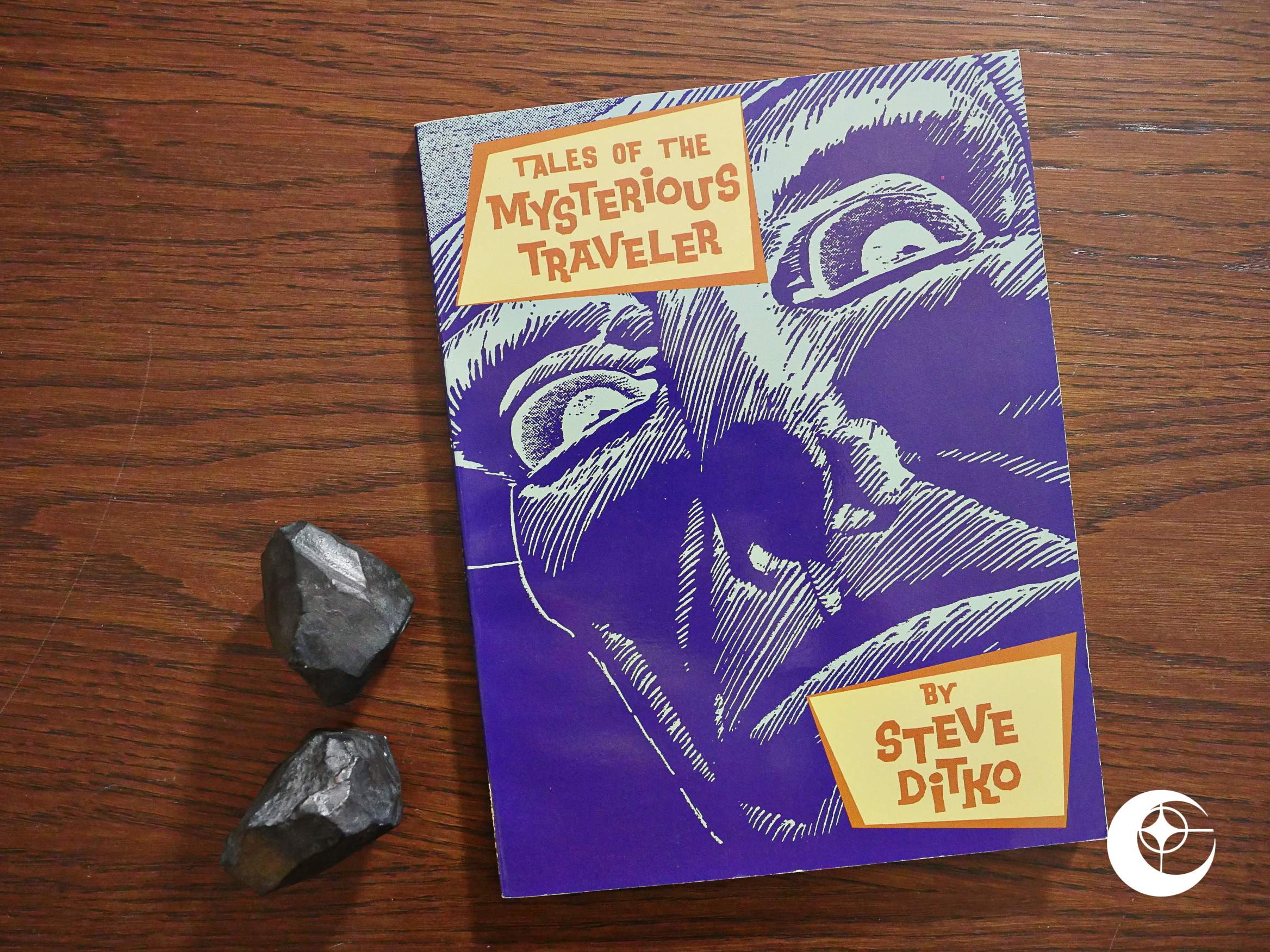

Toadswart D’Amplestone (1990) Tales of the Mysterious Traveler (1990)

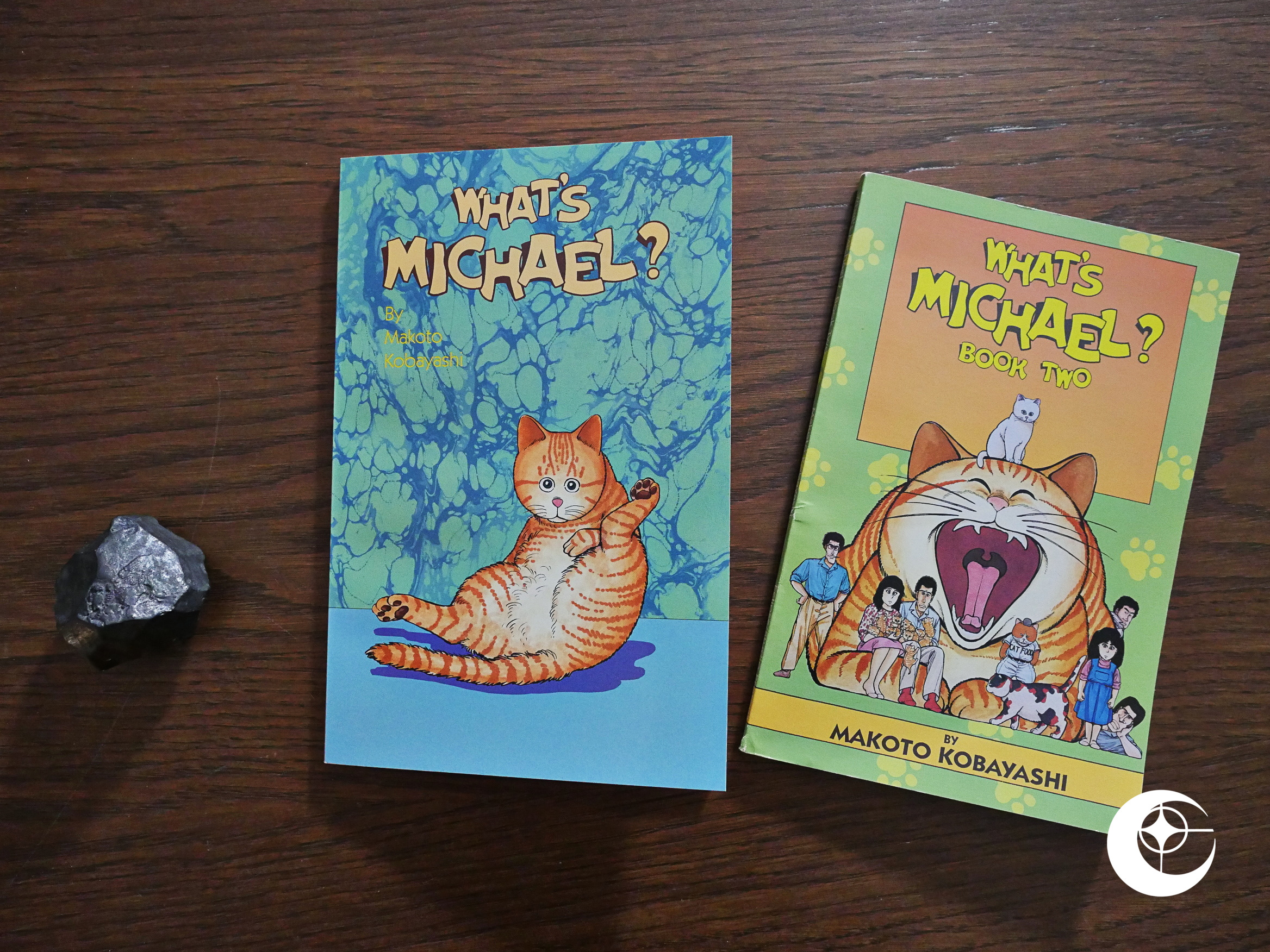

Tales of the Mysterious Traveler (1990) What’s Michael? (1990) #1-2

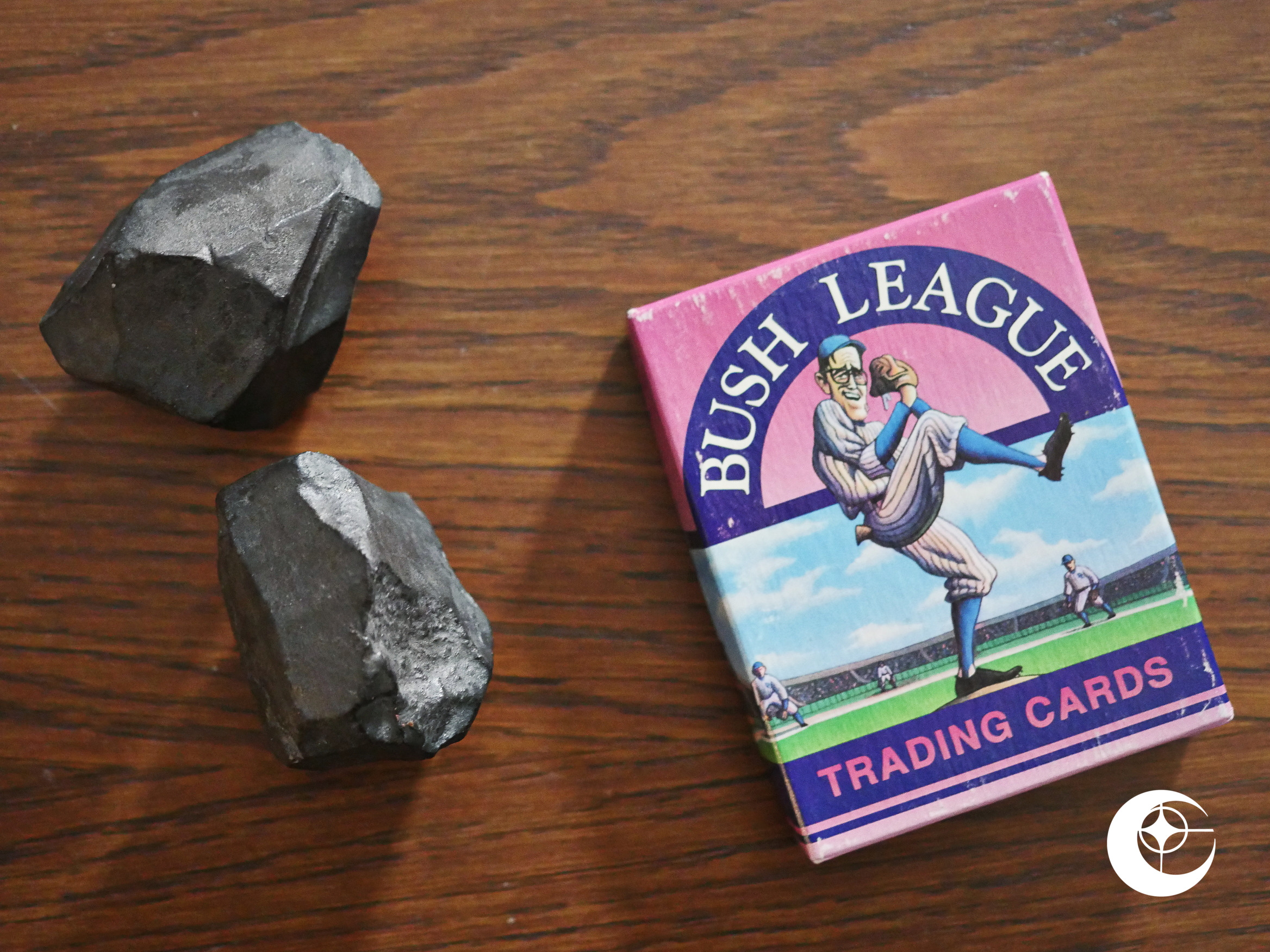

What’s Michael? (1990) #1-2 Bush League Trading Cards (1990)

Bush League Trading Cards (1990) Black Magic (1990) #1-4

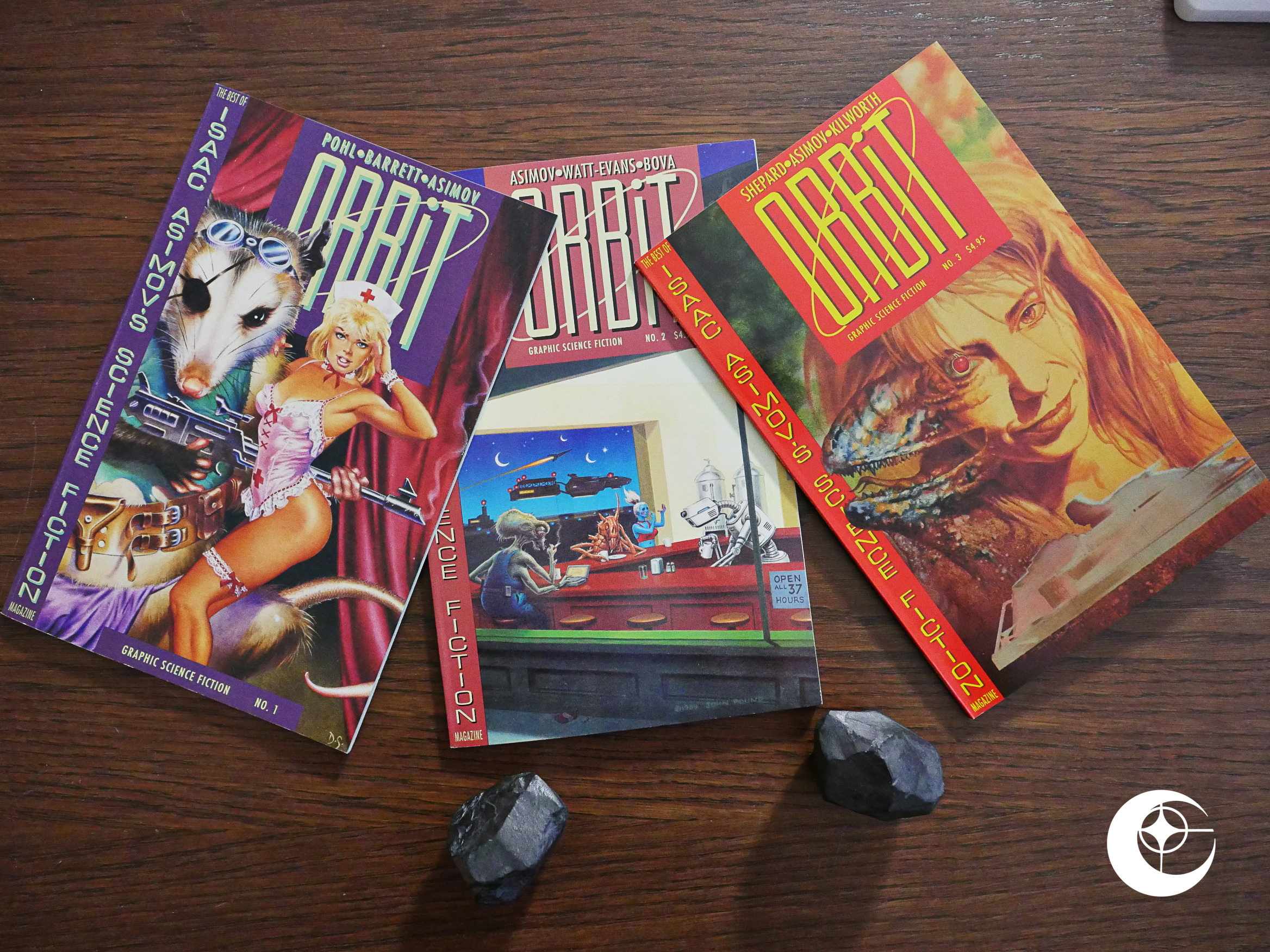

Black Magic (1990) #1-4 ORBiT (1990) #1-3

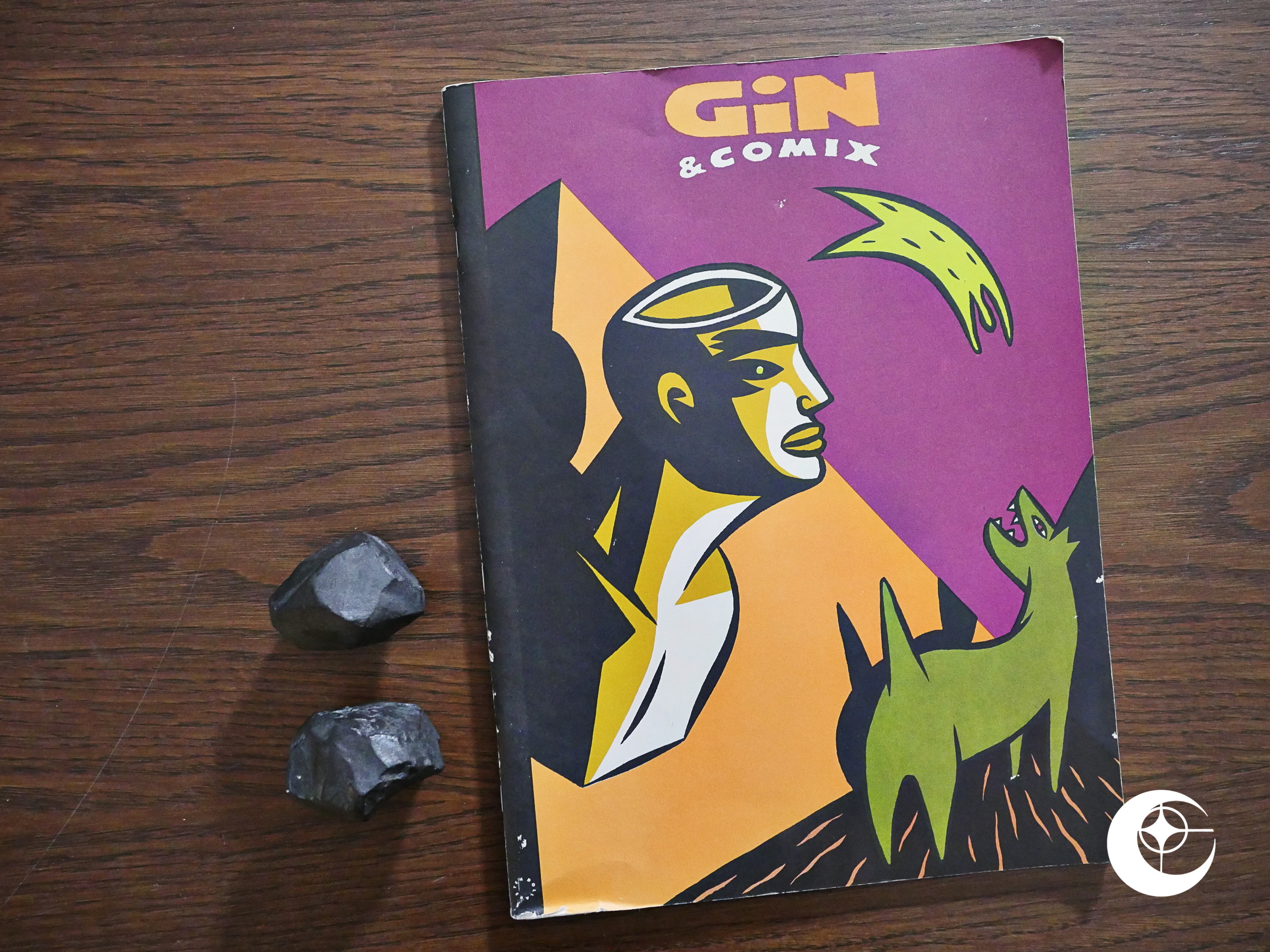

ORBiT (1990) #1-3 Gin and Comix (1990) #1

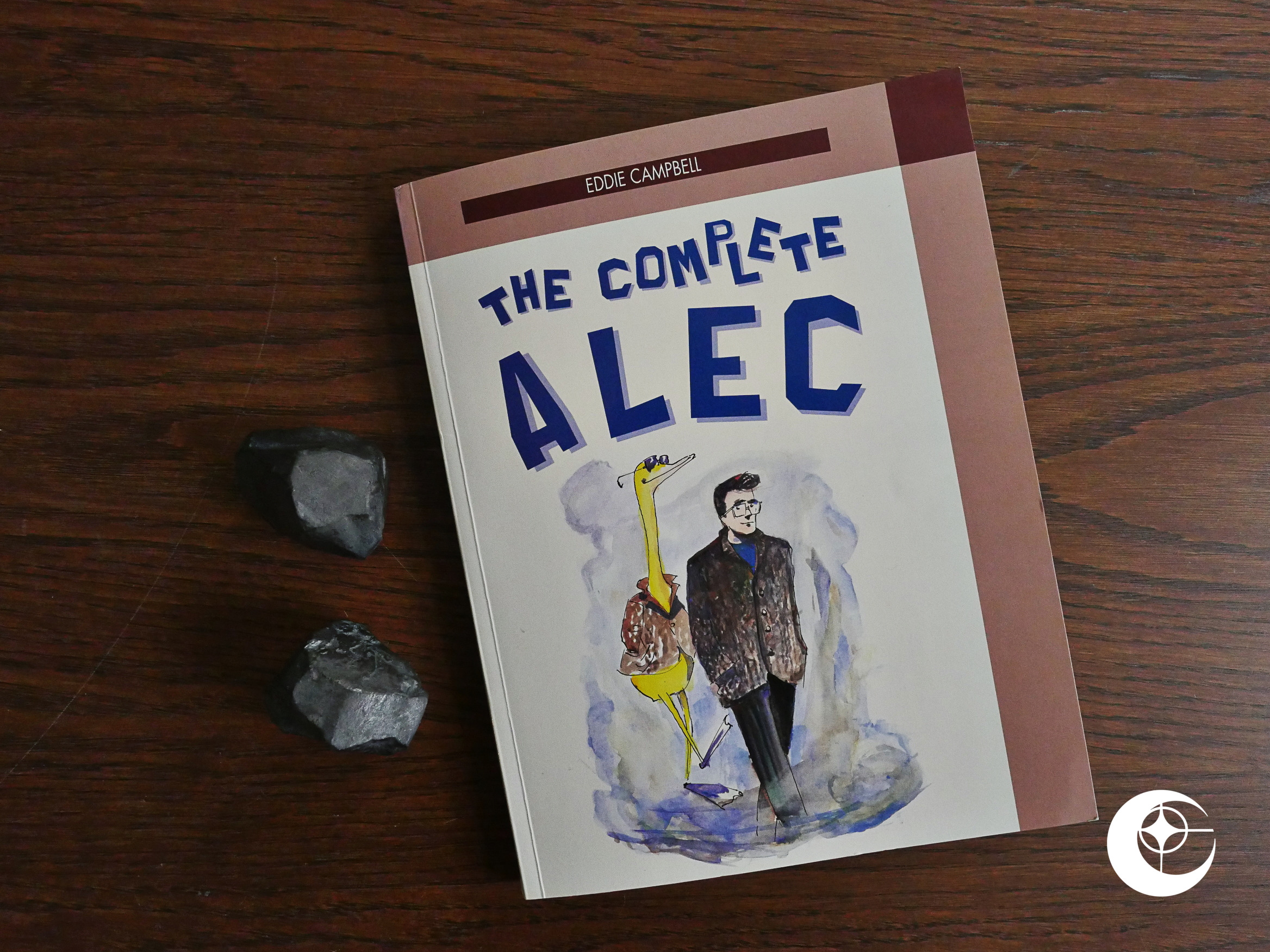

Gin and Comix (1990) #1 The Complete Alec (1990)

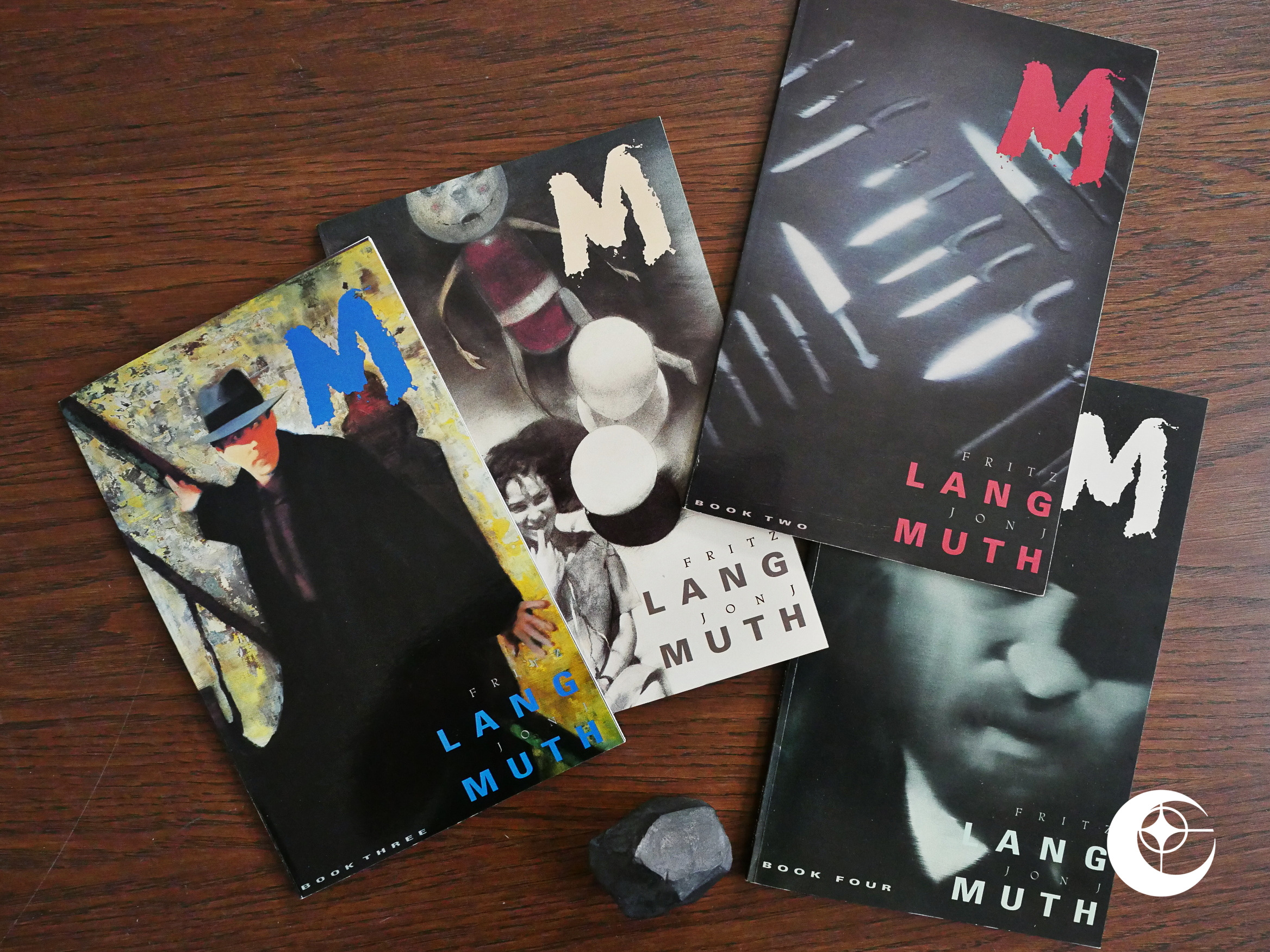

The Complete Alec (1990) M (1990) #1-4

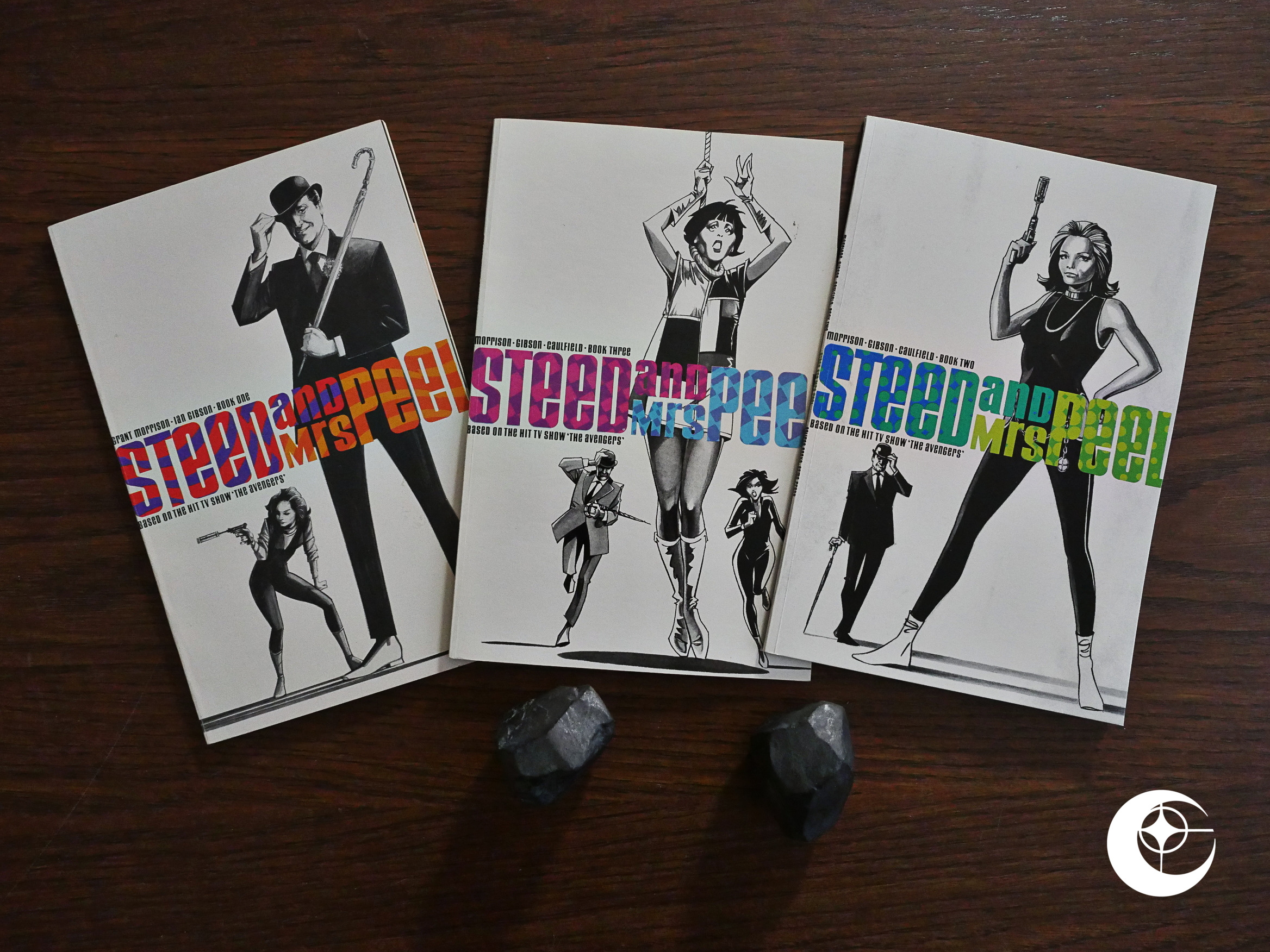

M (1990) #1-4 Steed and Mrs. Peel (1990) #1-3

Steed and Mrs. Peel (1990) #1-3 Clive Barker Illustrator (1990)

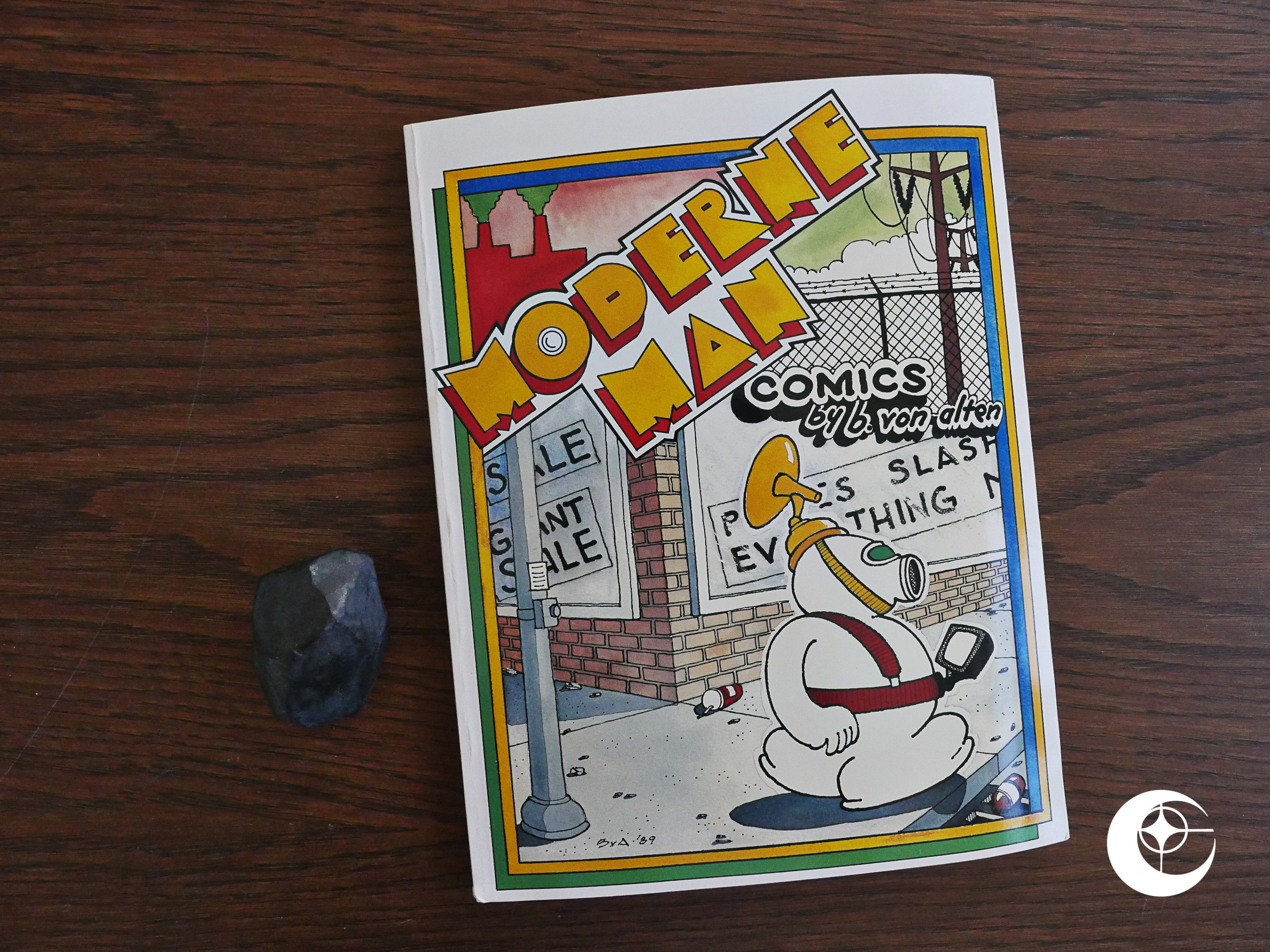

Clive Barker Illustrator (1990) Moderne Man Comics (1990) #1

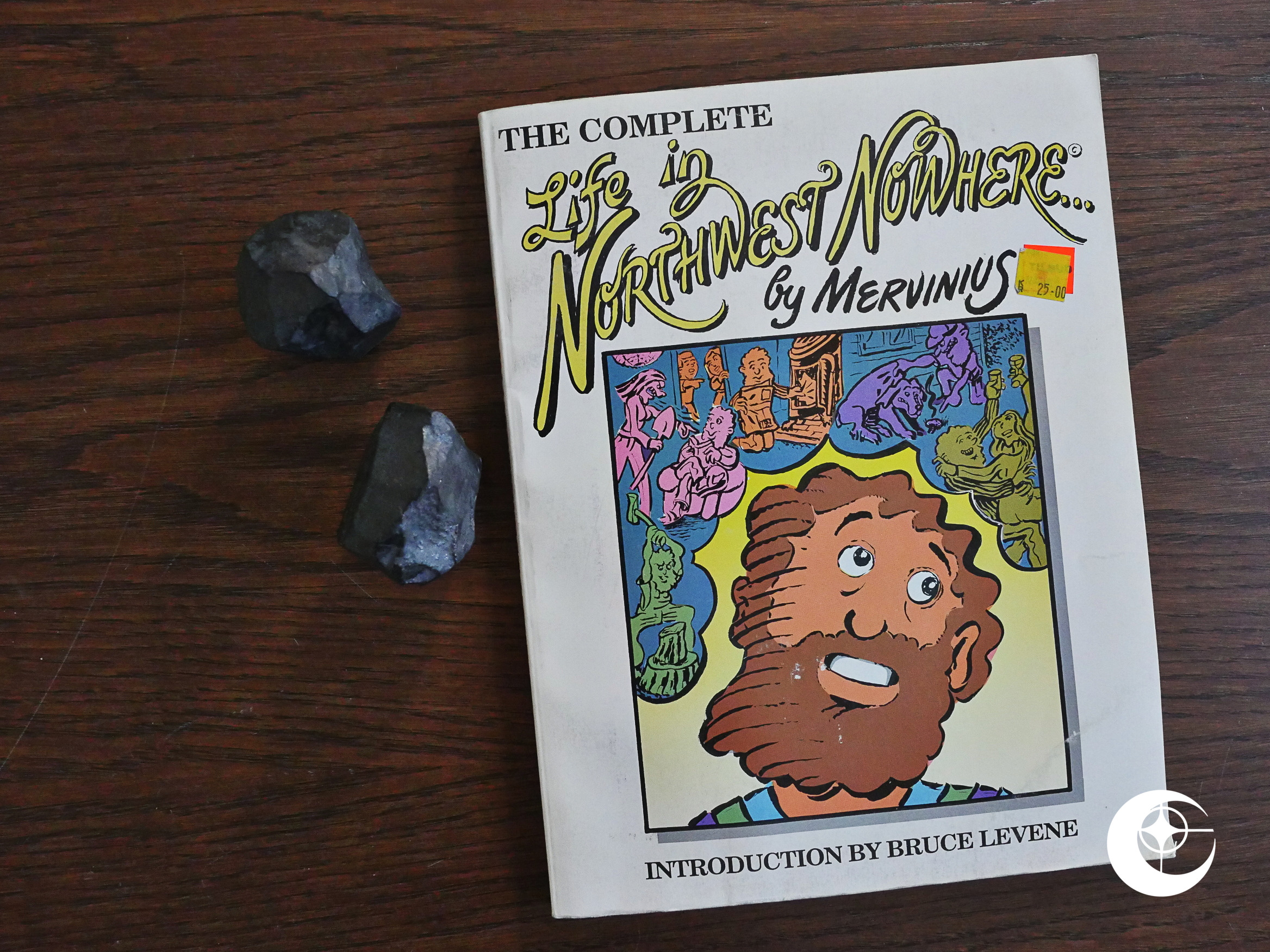

Moderne Man Comics (1990) #1 Life in Northwest Nowhere (1990)

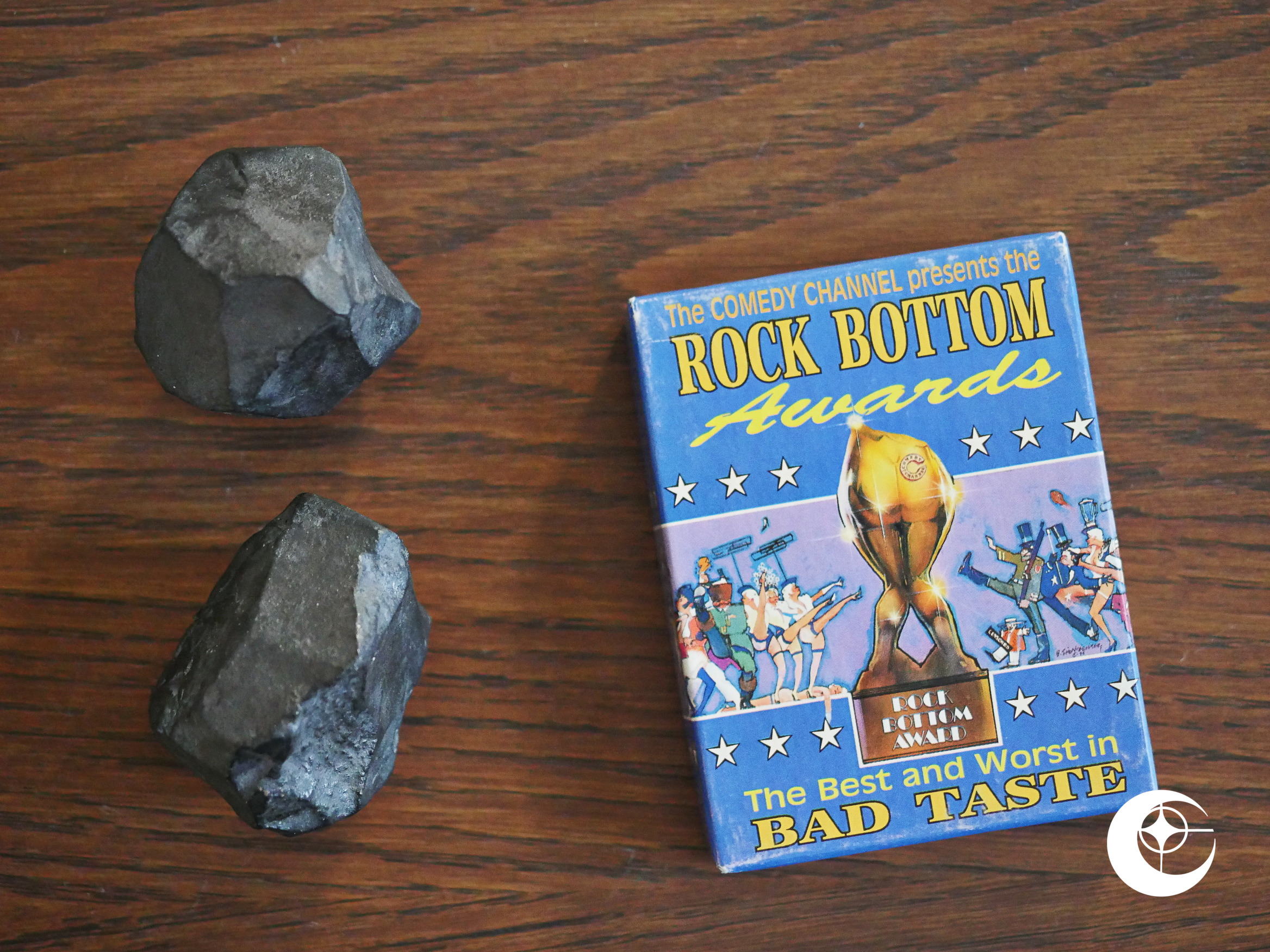

Life in Northwest Nowhere (1990) Rock Bottom Trading Cards (1990)

Rock Bottom Trading Cards (1990) Lost Continent (1990) #1-6

Lost Continent (1990) #1-6 Words Without Pictures (1990)

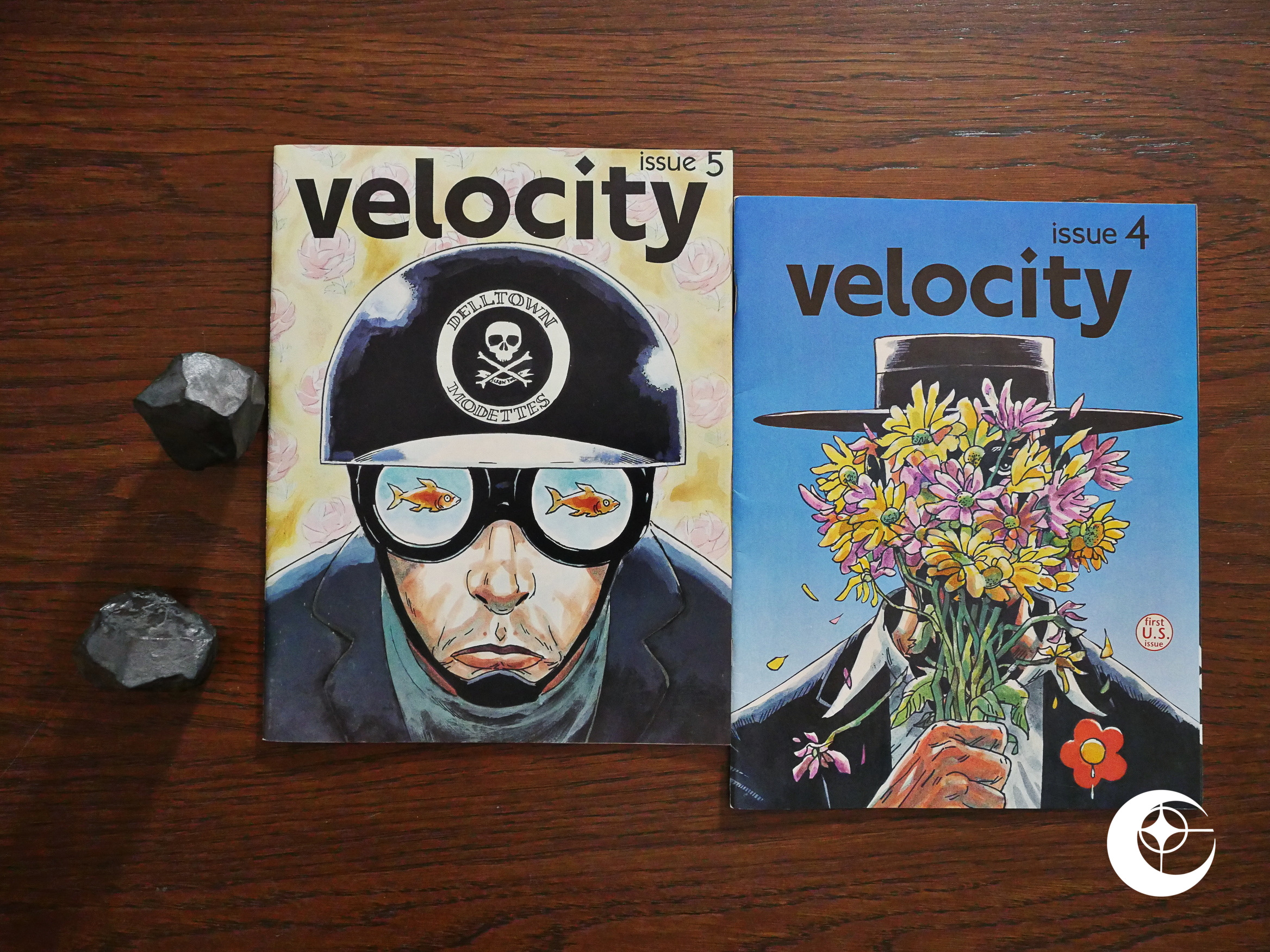

Words Without Pictures (1990) Velocity (1991) #4-5

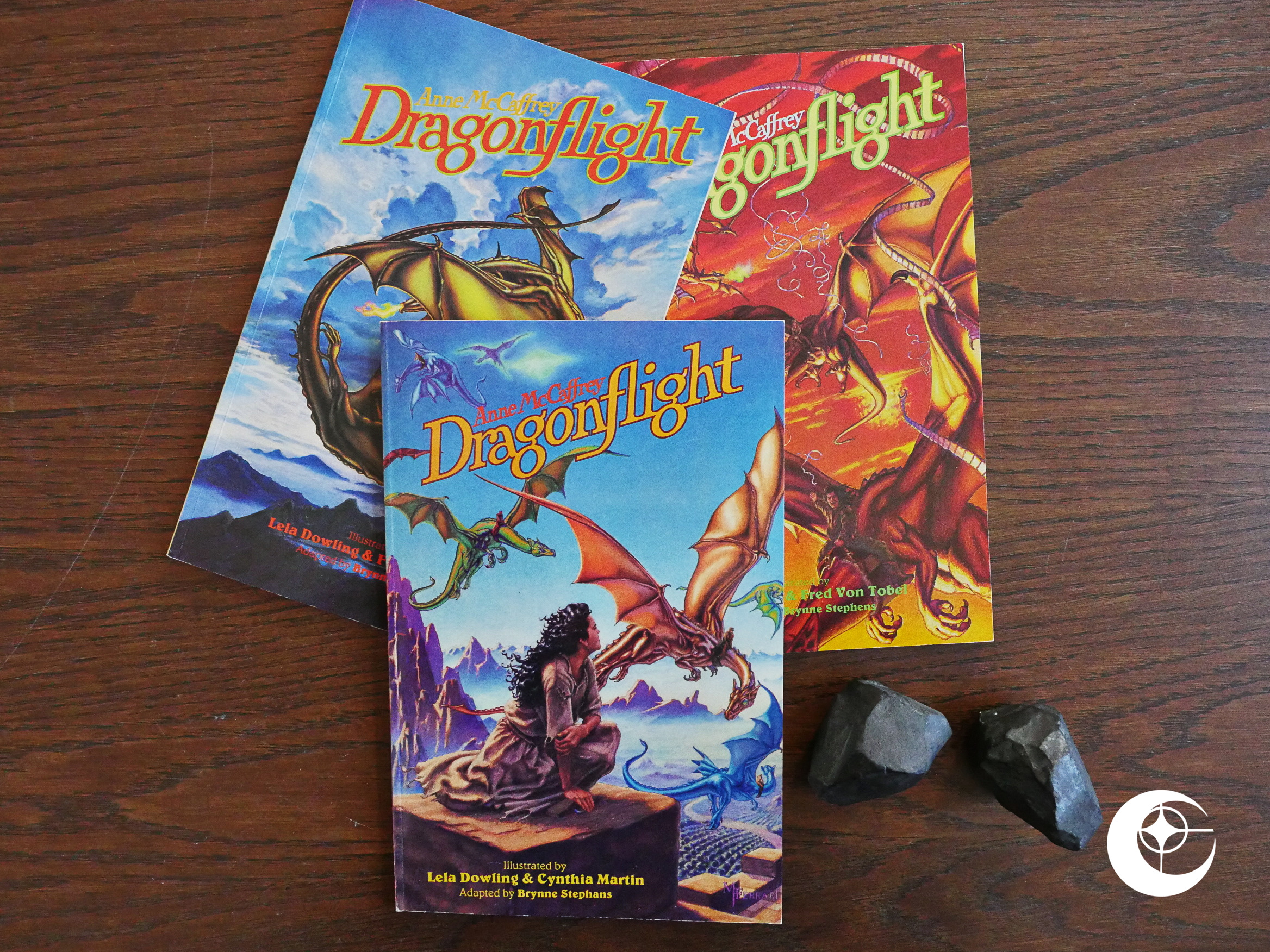

Velocity (1991) #4-5 Dragonflight (1991) #1-3

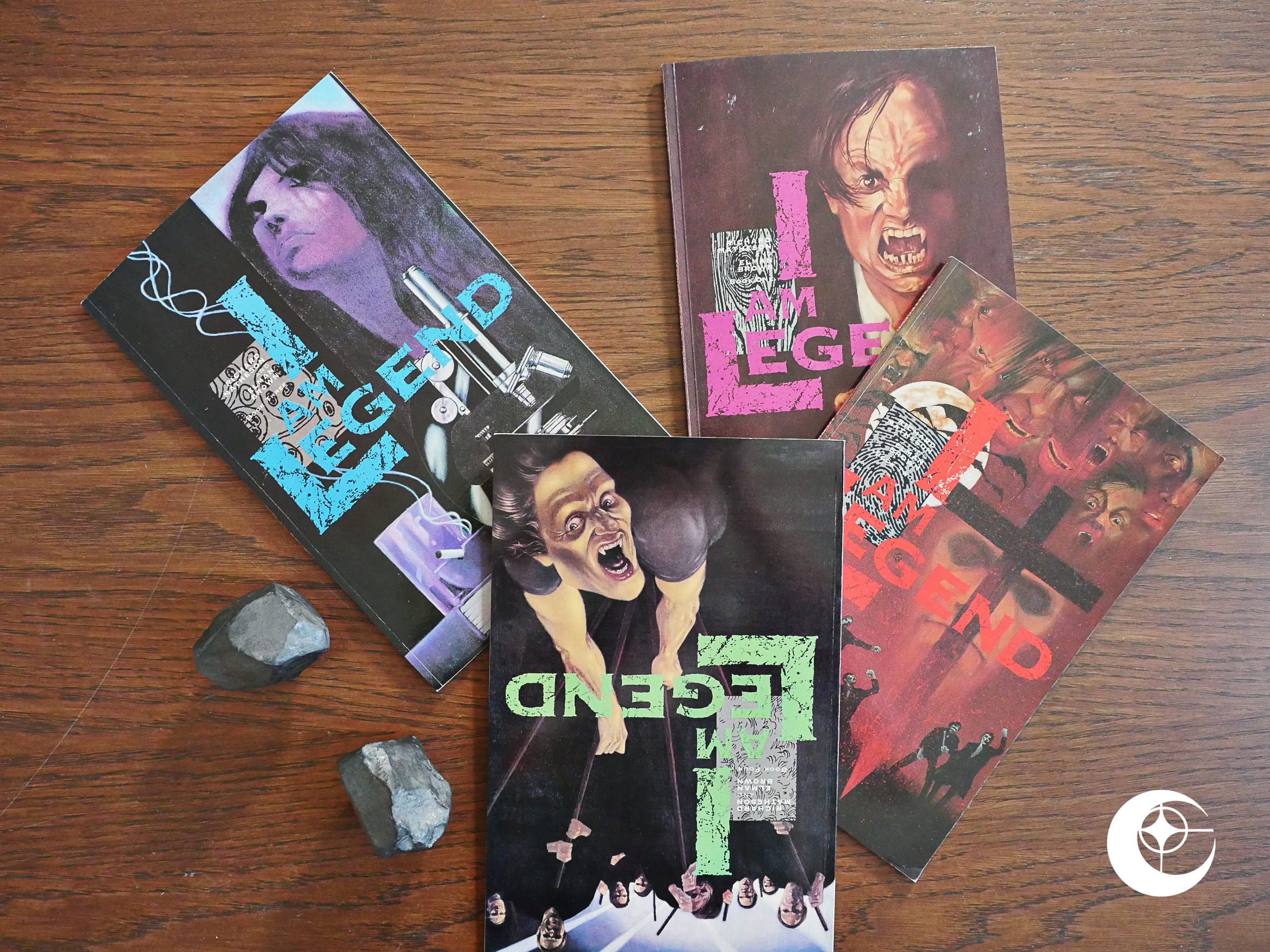

Dragonflight (1991) #1-3 I Am Legend (1991) #1-4

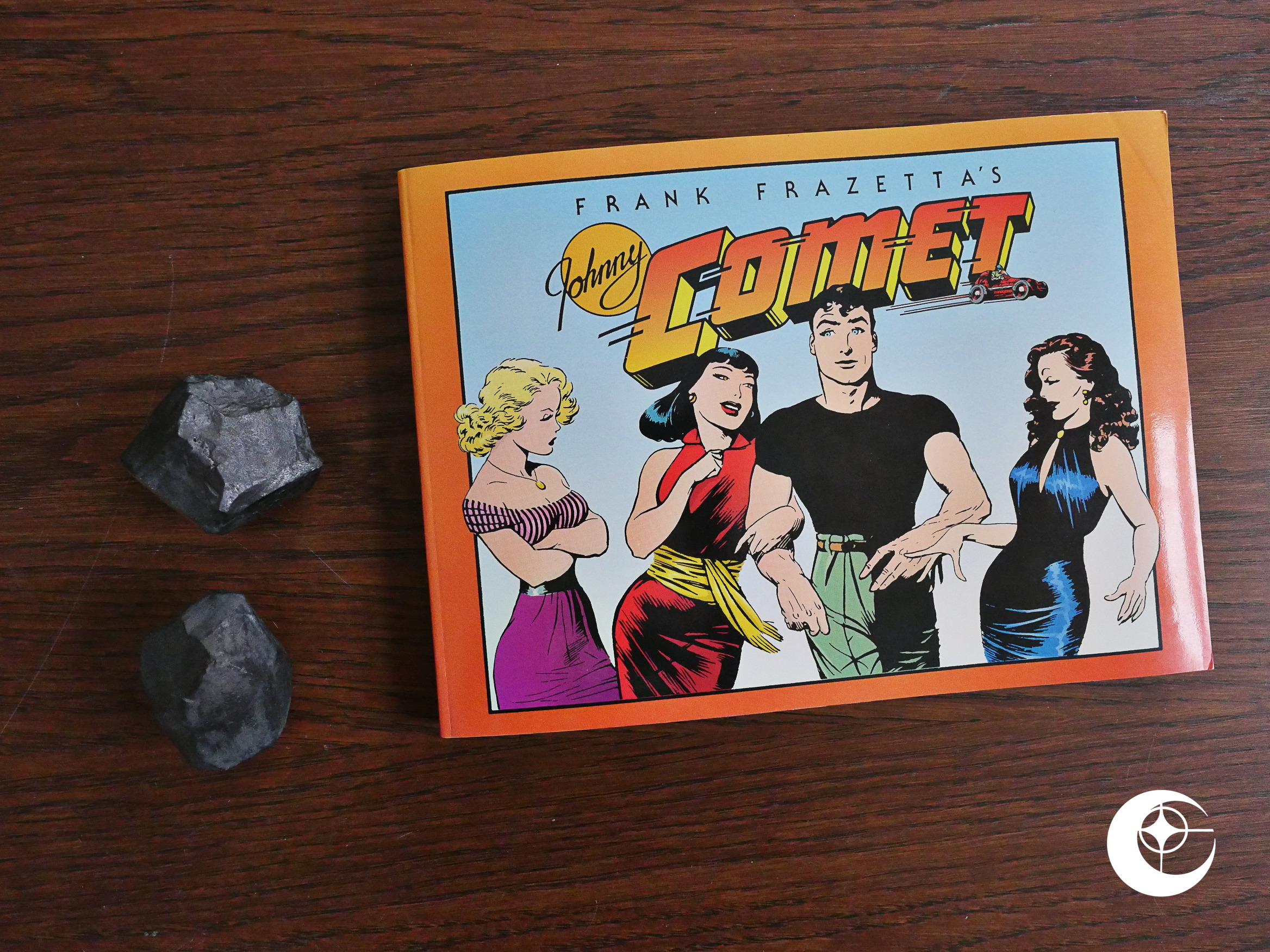

I Am Legend (1991) #1-4 Johnny Comet (1991) #1

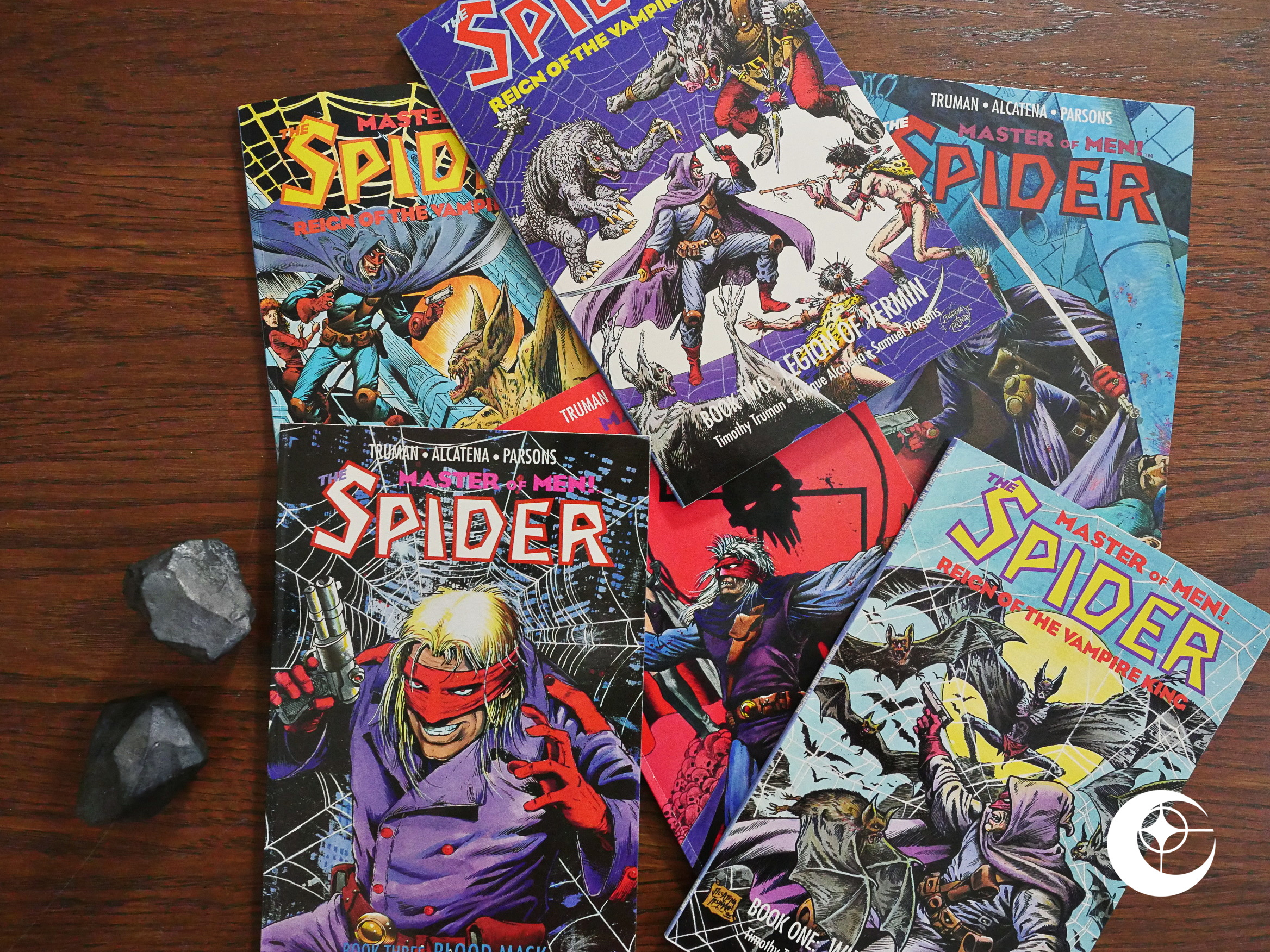

Johnny Comet (1991) #1 The Spider (1991) #1-3

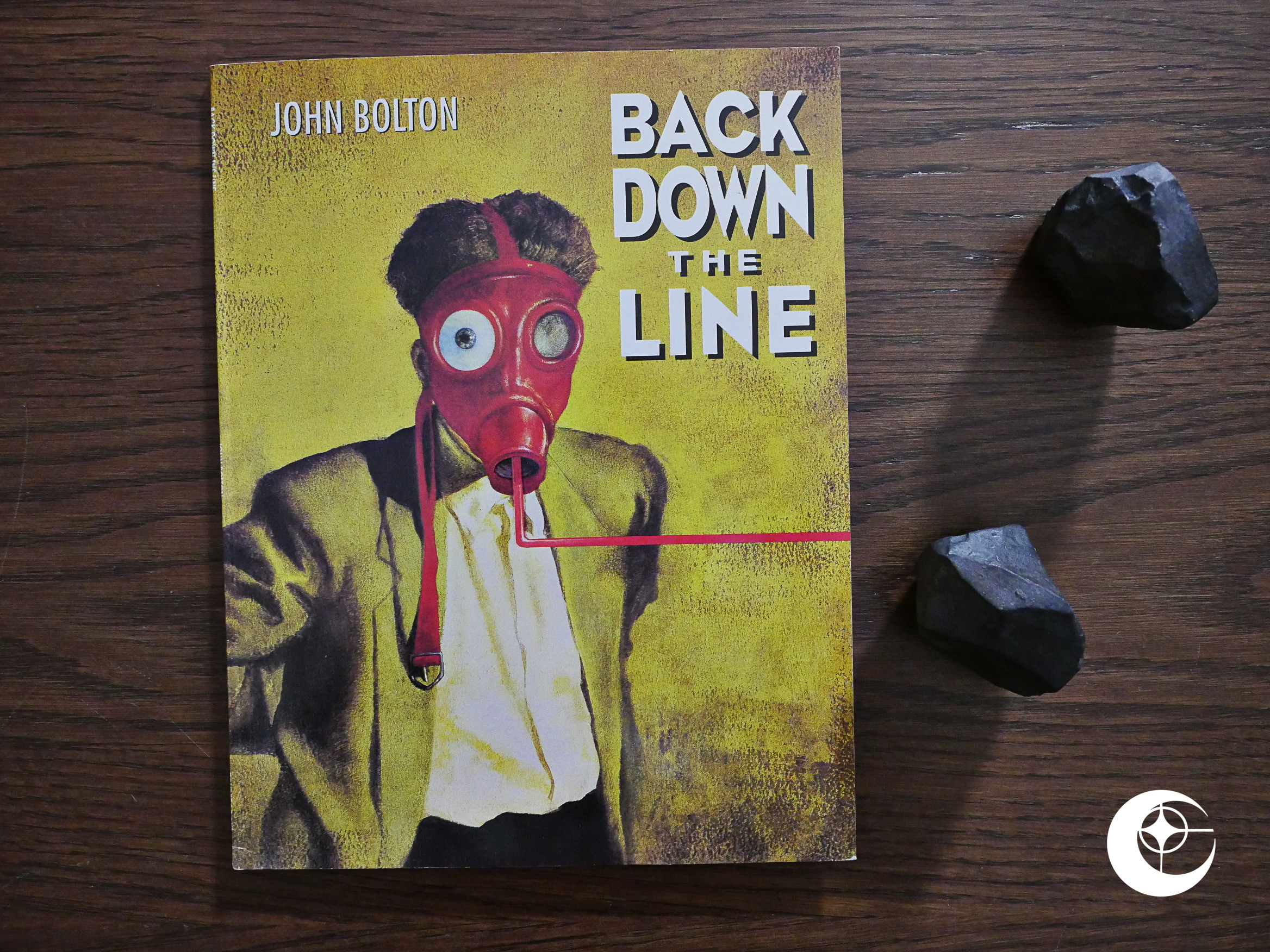

The Spider (1991) #1-3 Back Down the Line (1991)

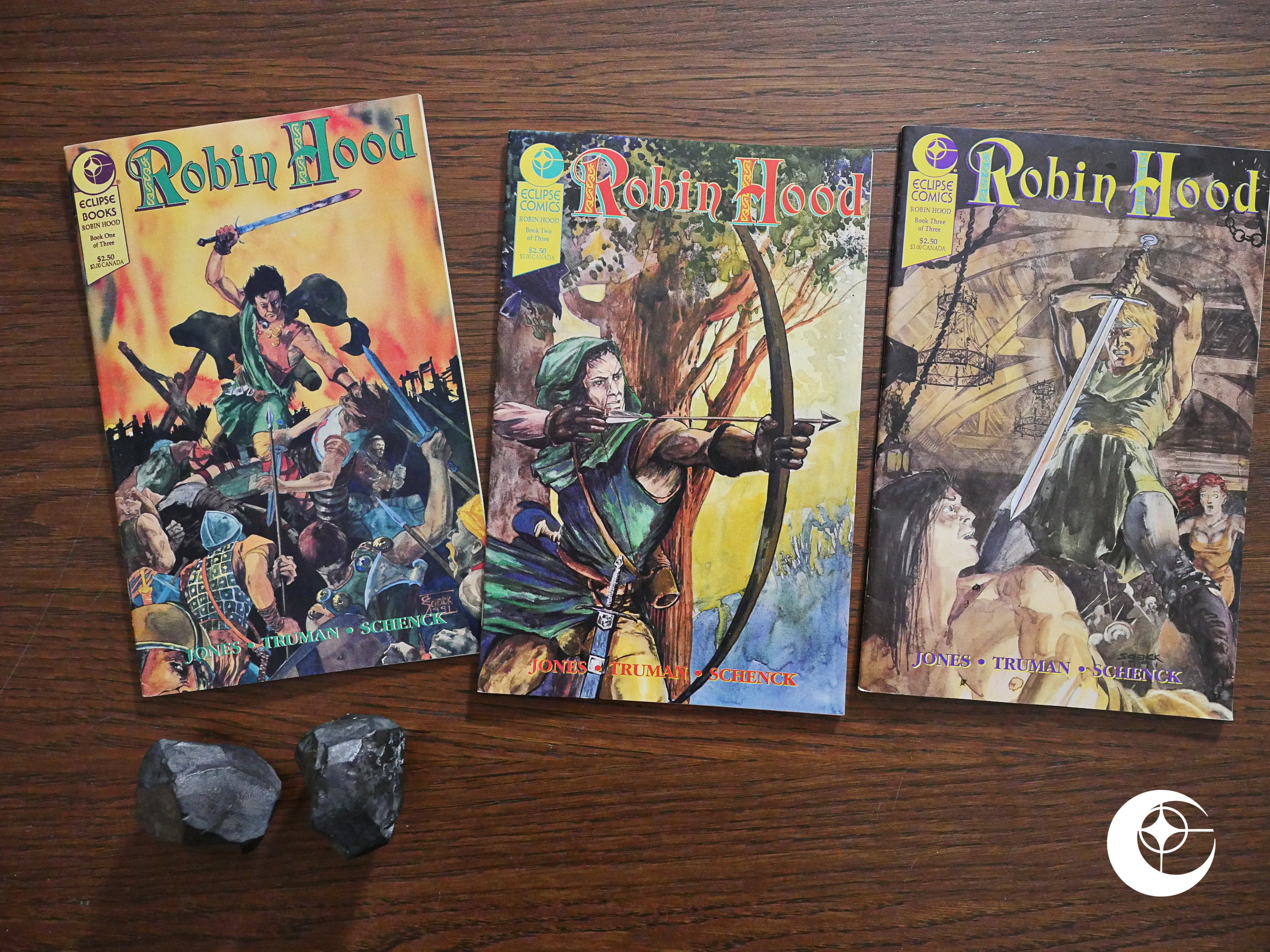

Back Down the Line (1991) Robin Hood (1991) #1-3

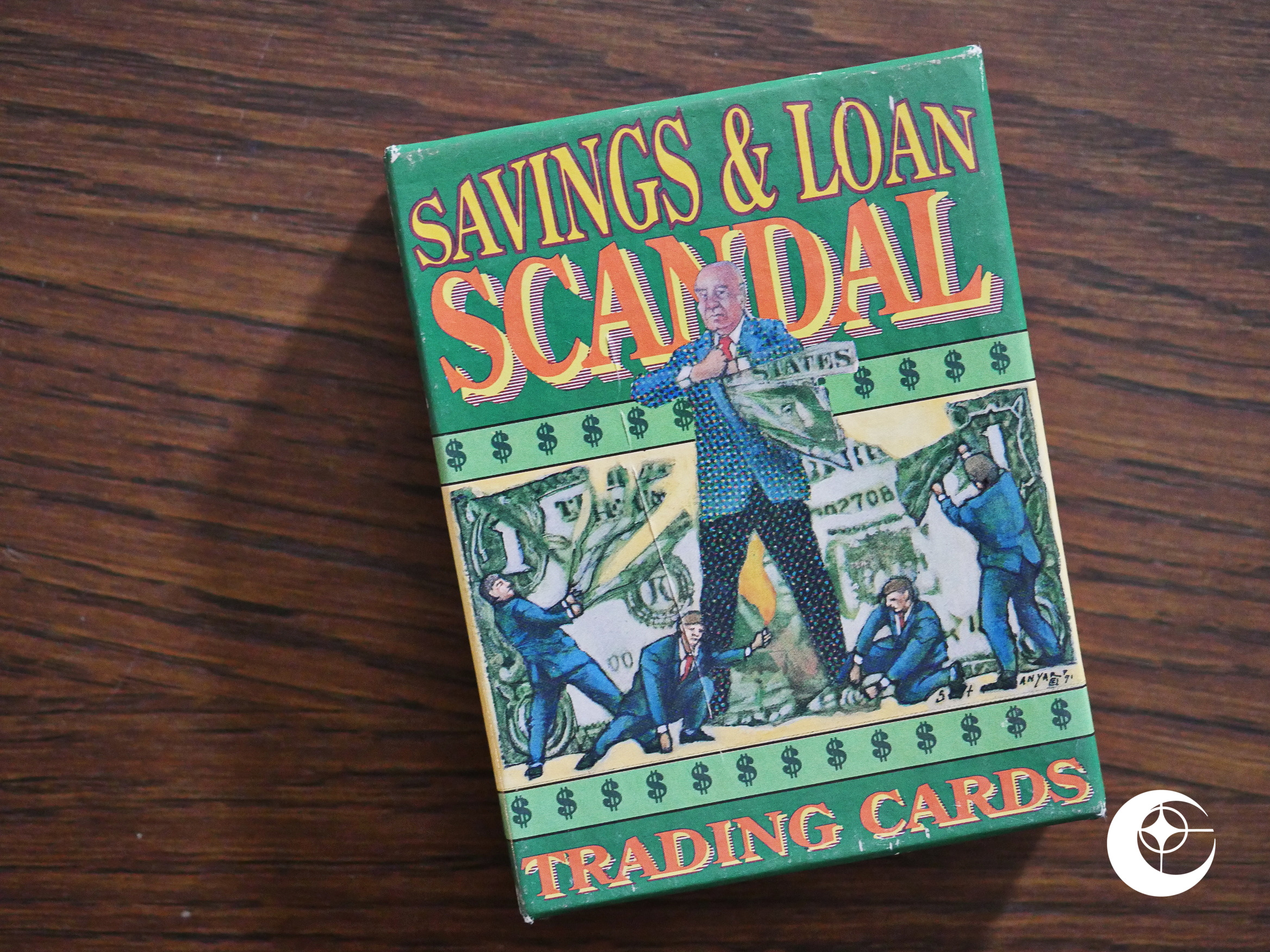

Robin Hood (1991) #1-3 The Savings and Loans Scandal Trading Cards (1991)

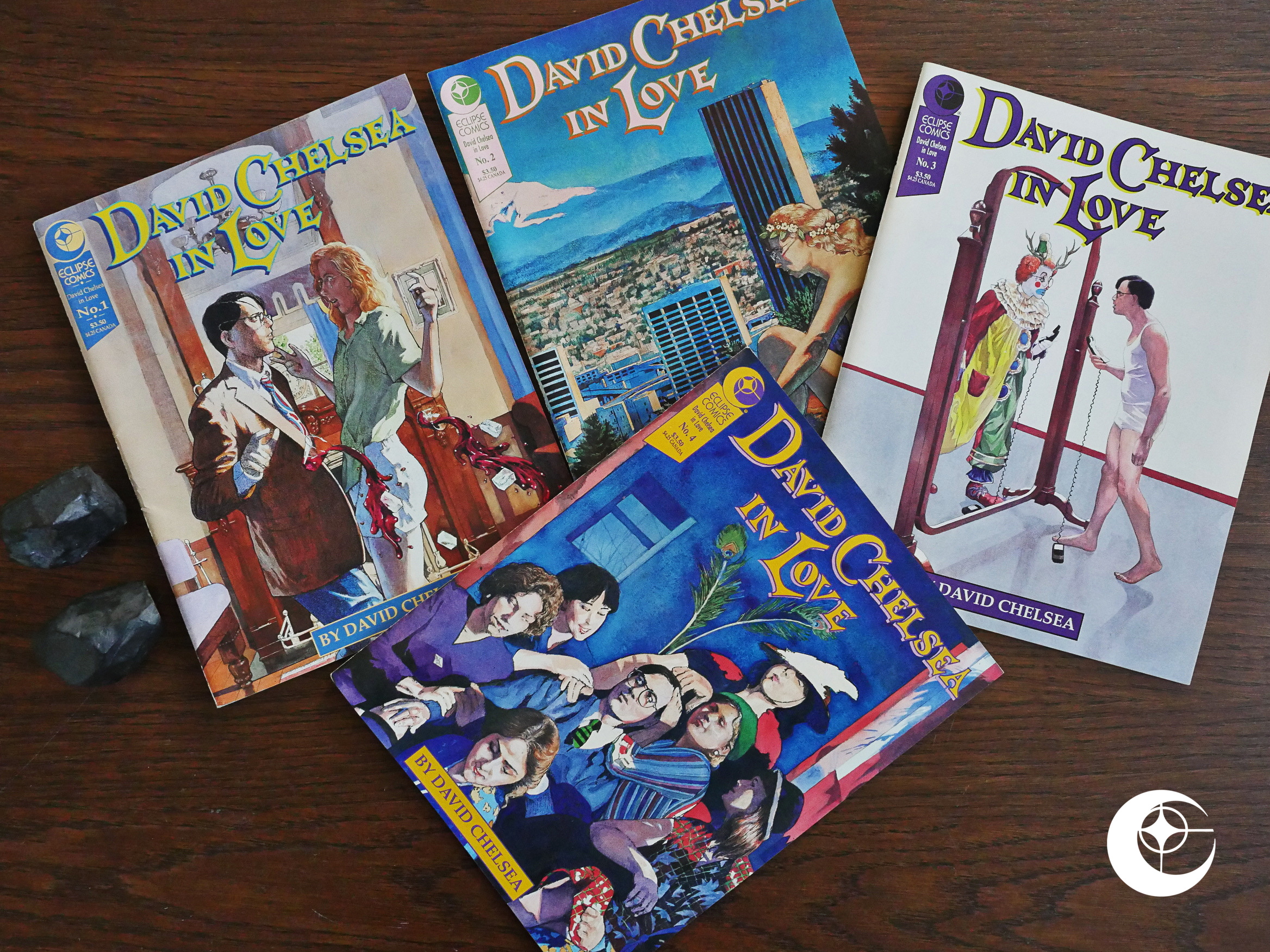

The Savings and Loans Scandal Trading Cards (1991) David Chelsea in Love (1991) #1-4

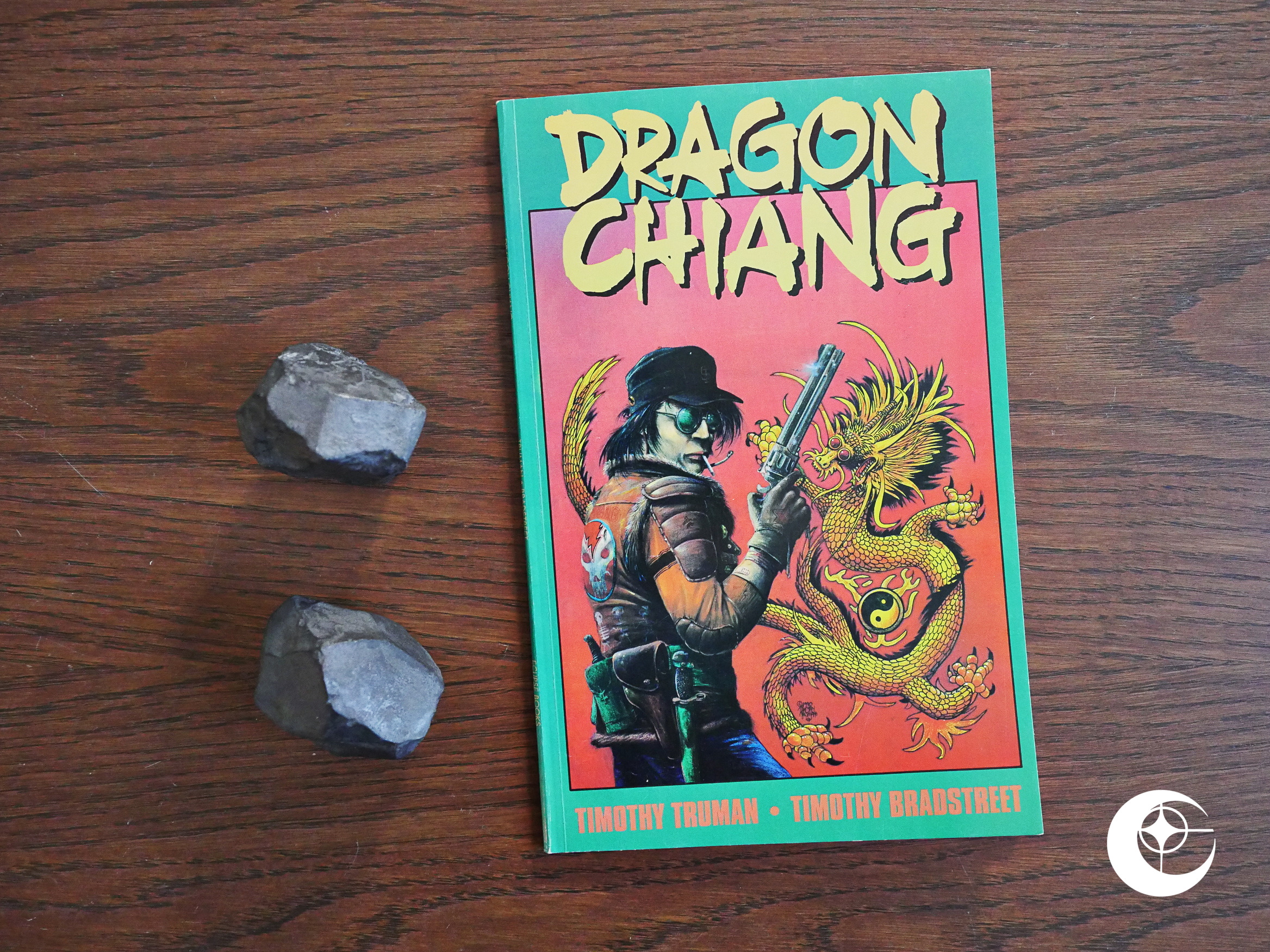

David Chelsea in Love (1991) #1-4 Dragon Chiang (1991) #1

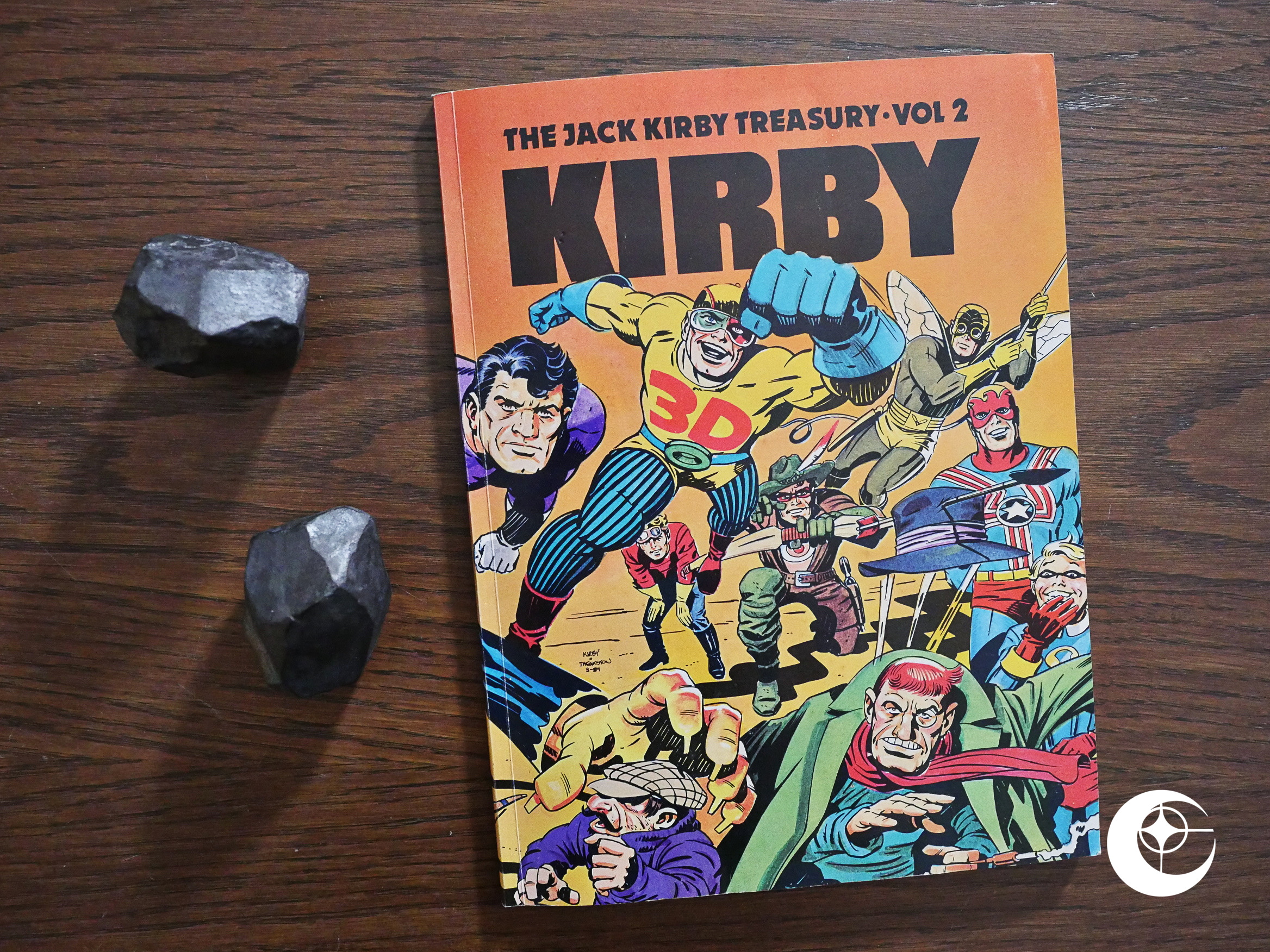

Dragon Chiang (1991) #1 The Jack Kirby Treasury (1991)

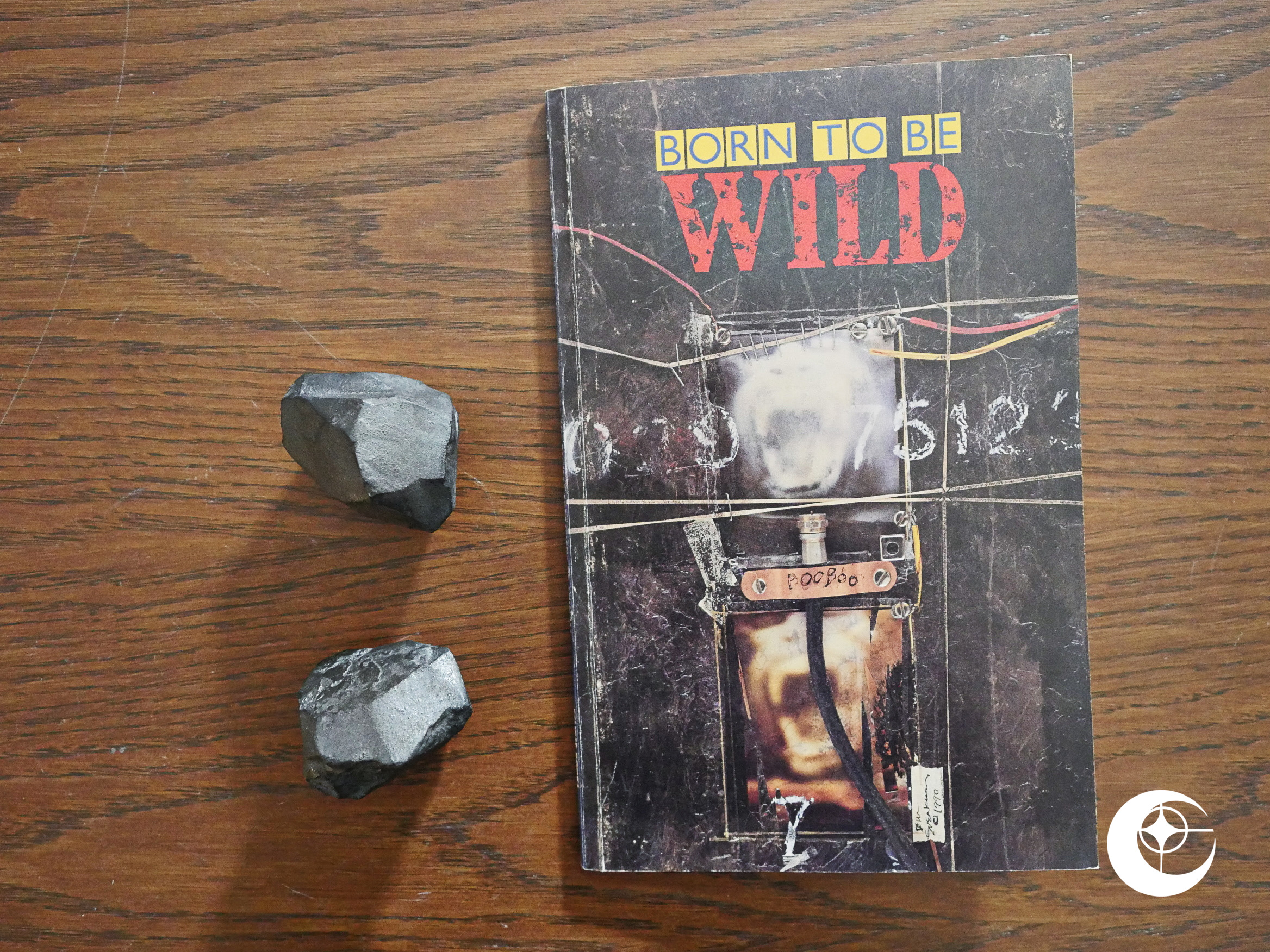

The Jack Kirby Treasury (1991) Born to Be Wild (1991)

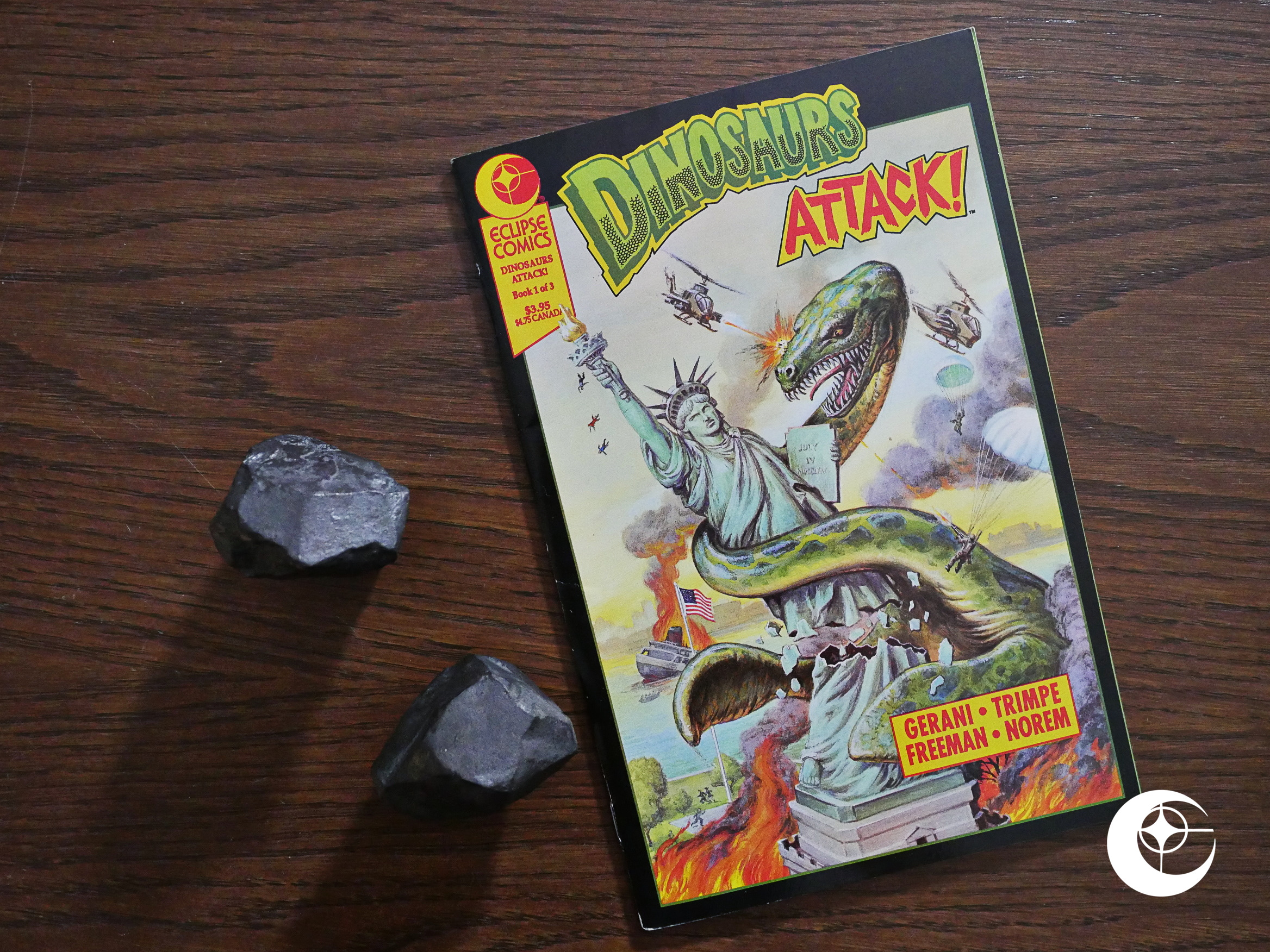

Born to Be Wild (1991) Dinosaurs Attack! The Graphic Novel (1991) #1

Dinosaurs Attack! The Graphic Novel (1991) #1 Son of Celluloid (1991)

Son of Celluloid (1991) One Mile Up (1991) #1

One Mile Up (1991) #1 Pandemonium (1991)

Pandemonium (1991) Straight Up to See the Sky (1991)

Straight Up to See the Sky (1991) Drug Wars (1991)

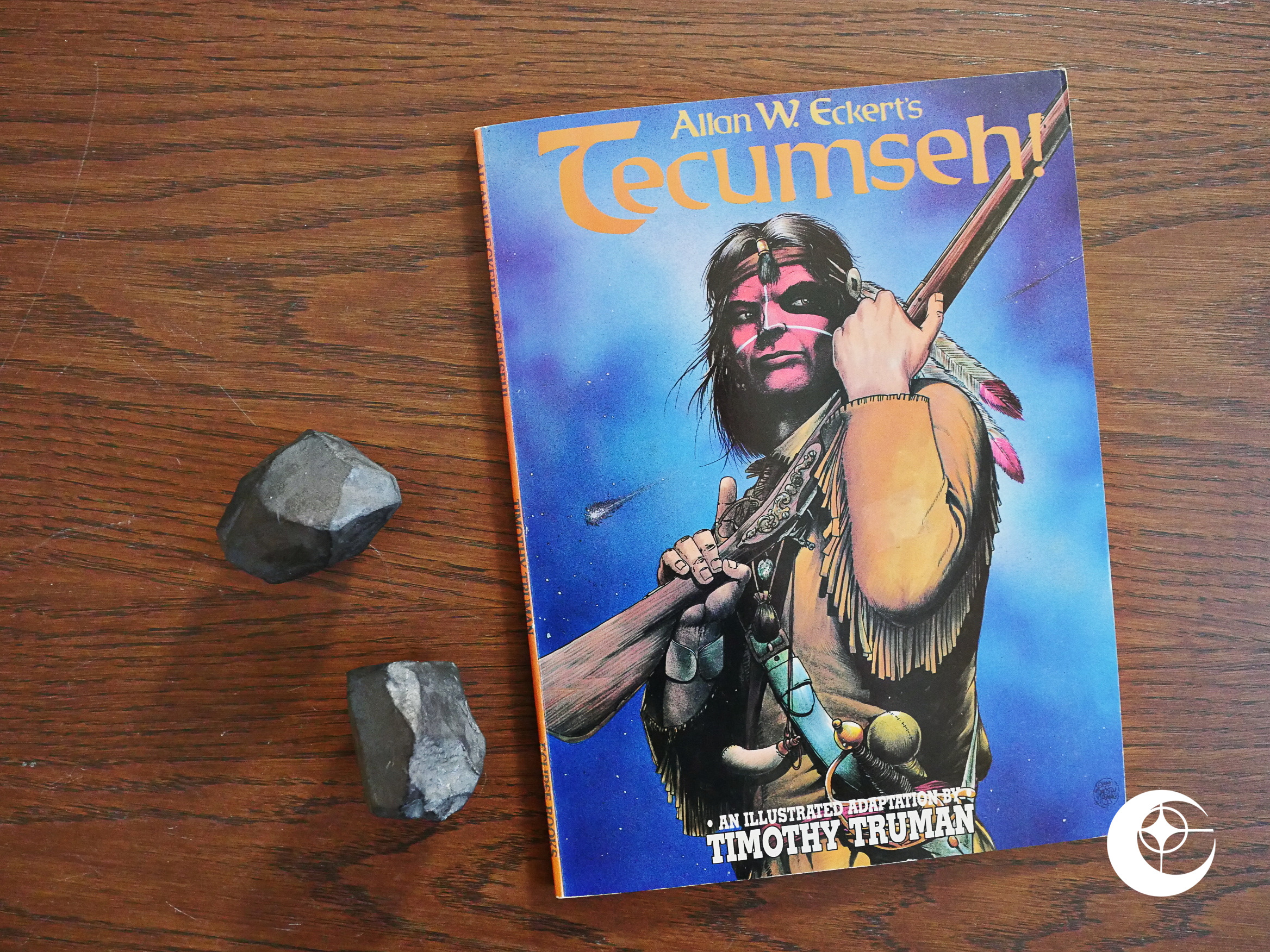

Drug Wars (1991) Allan W. Eckert’s Tecumseh! (1992)

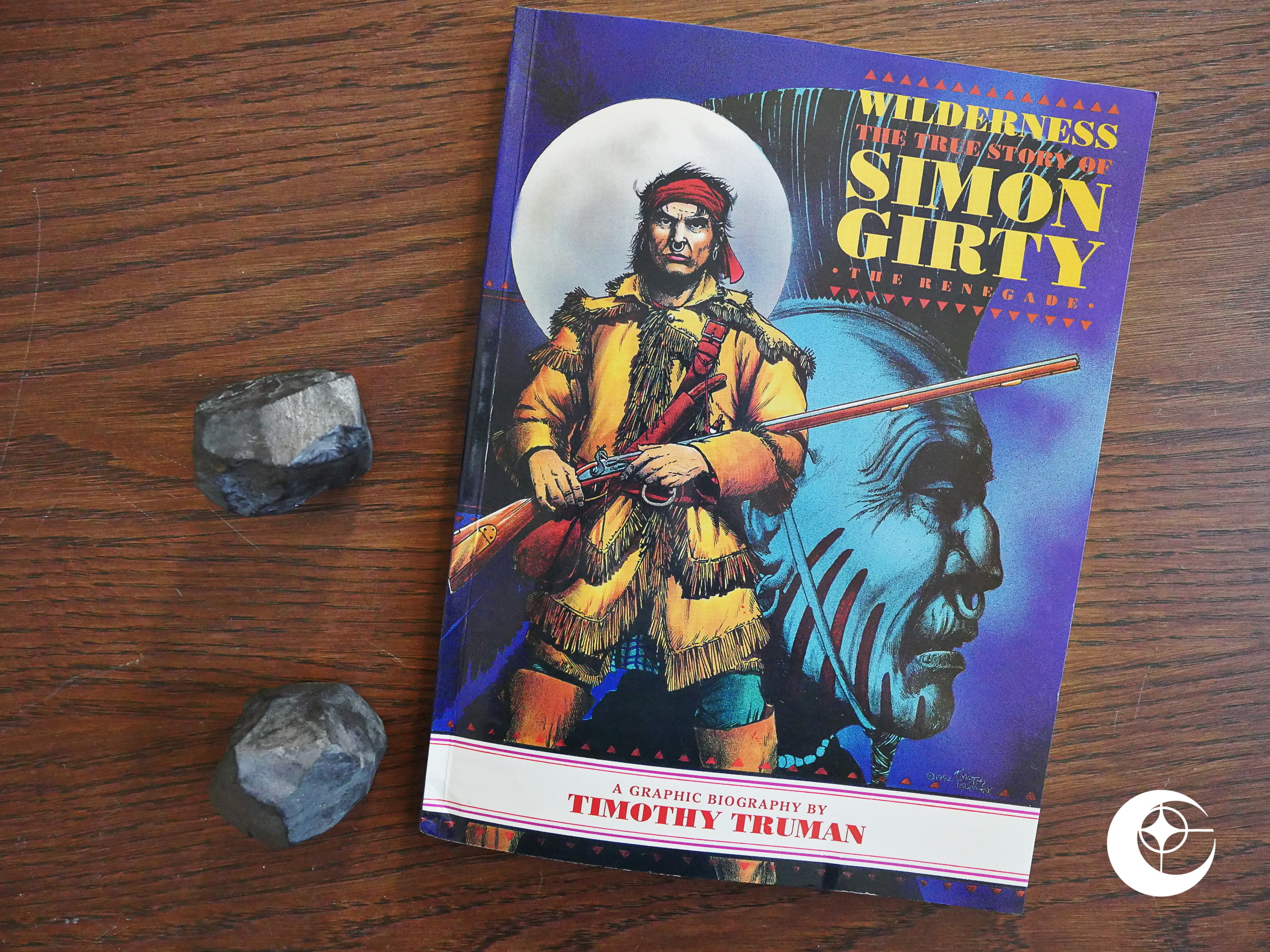

Allan W. Eckert’s Tecumseh! (1992) Wilderness: The True Story of Simon Girty (1992)

Wilderness: The True Story of Simon Girty (1992) Famous Comic Book Creators Trading Cards (1992)

Famous Comic Book Creators Trading Cards (1992) Crime and Punishment Trading Cards (1992)

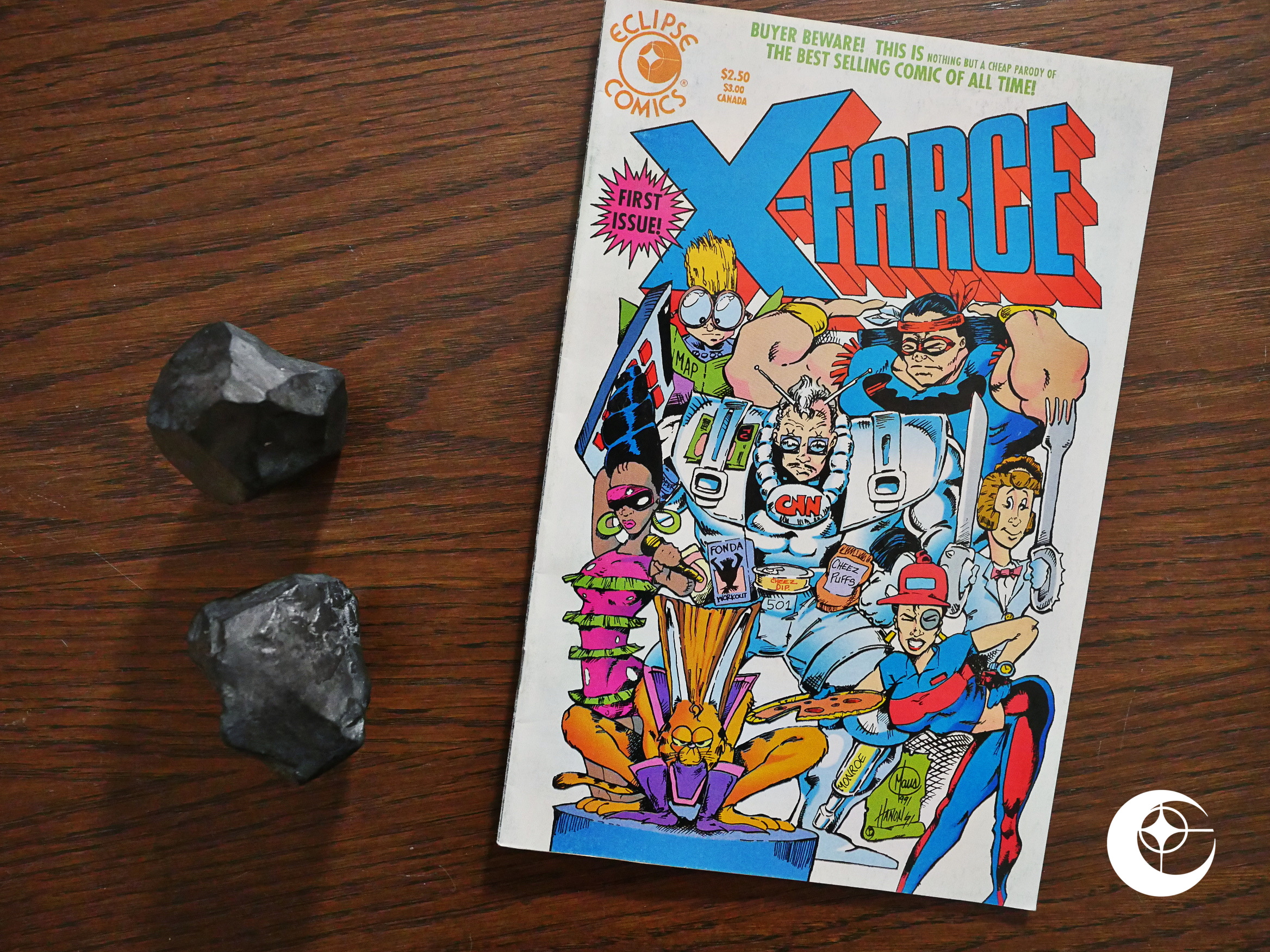

Crime and Punishment Trading Cards (1992) X-Farce (1992) #1

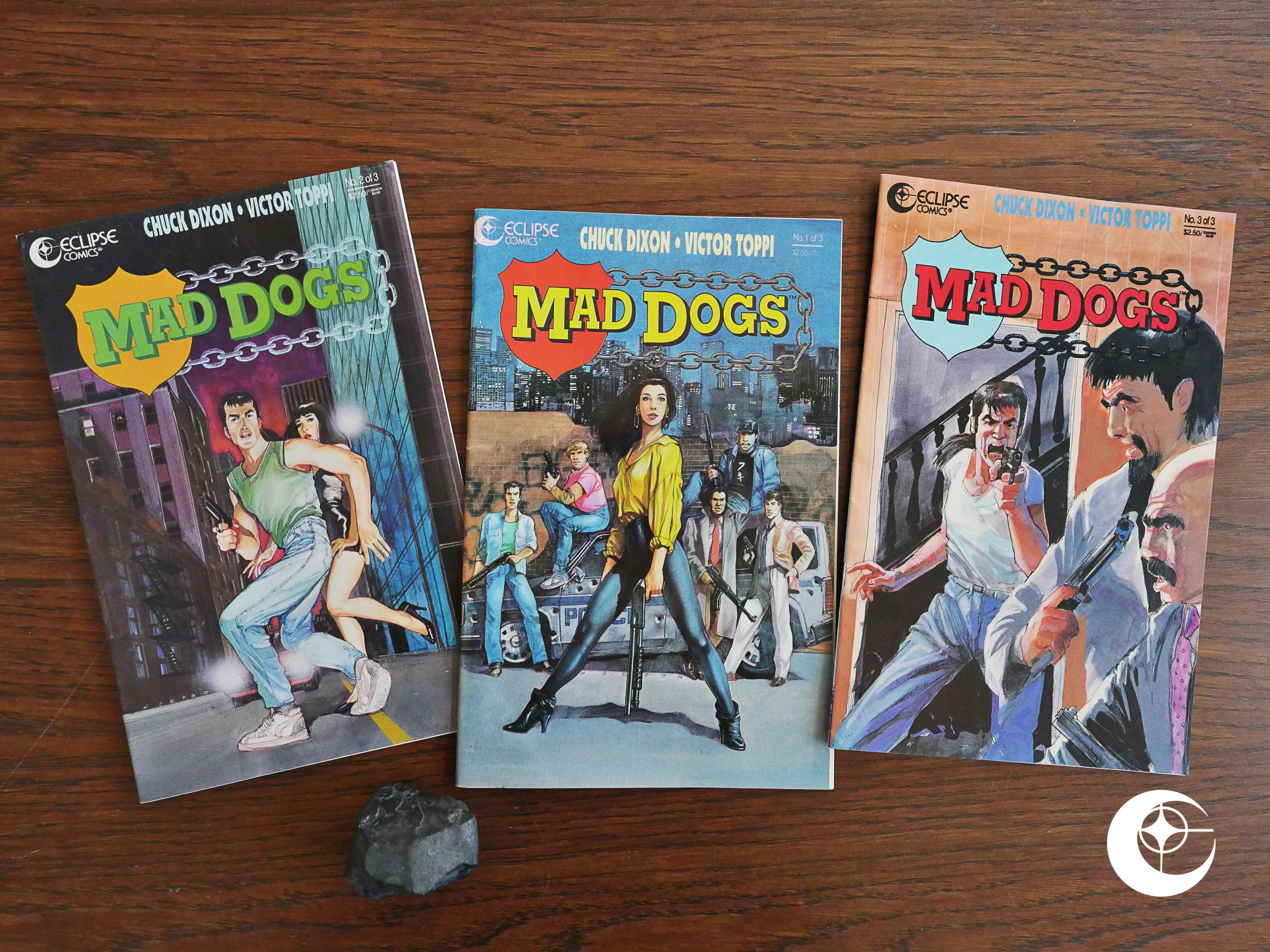

X-Farce (1992) #1 Mad Dogs (1992) #1-3

Mad Dogs (1992) #1-3 Metaphysique (1992) #1-2

Metaphysique (1992) #1-2 Blood is the Harvest (1992) #1-4

Blood is the Harvest (1992) #1-4 Parts Unknown (1992) #1-4

Parts Unknown (1992) #1-4 Blandman (1992) #1

Blandman (1992) #1 Retaliator (1992) #1-4

Retaliator (1992) #1-4 Loco vs. Pulverine (1992) #1

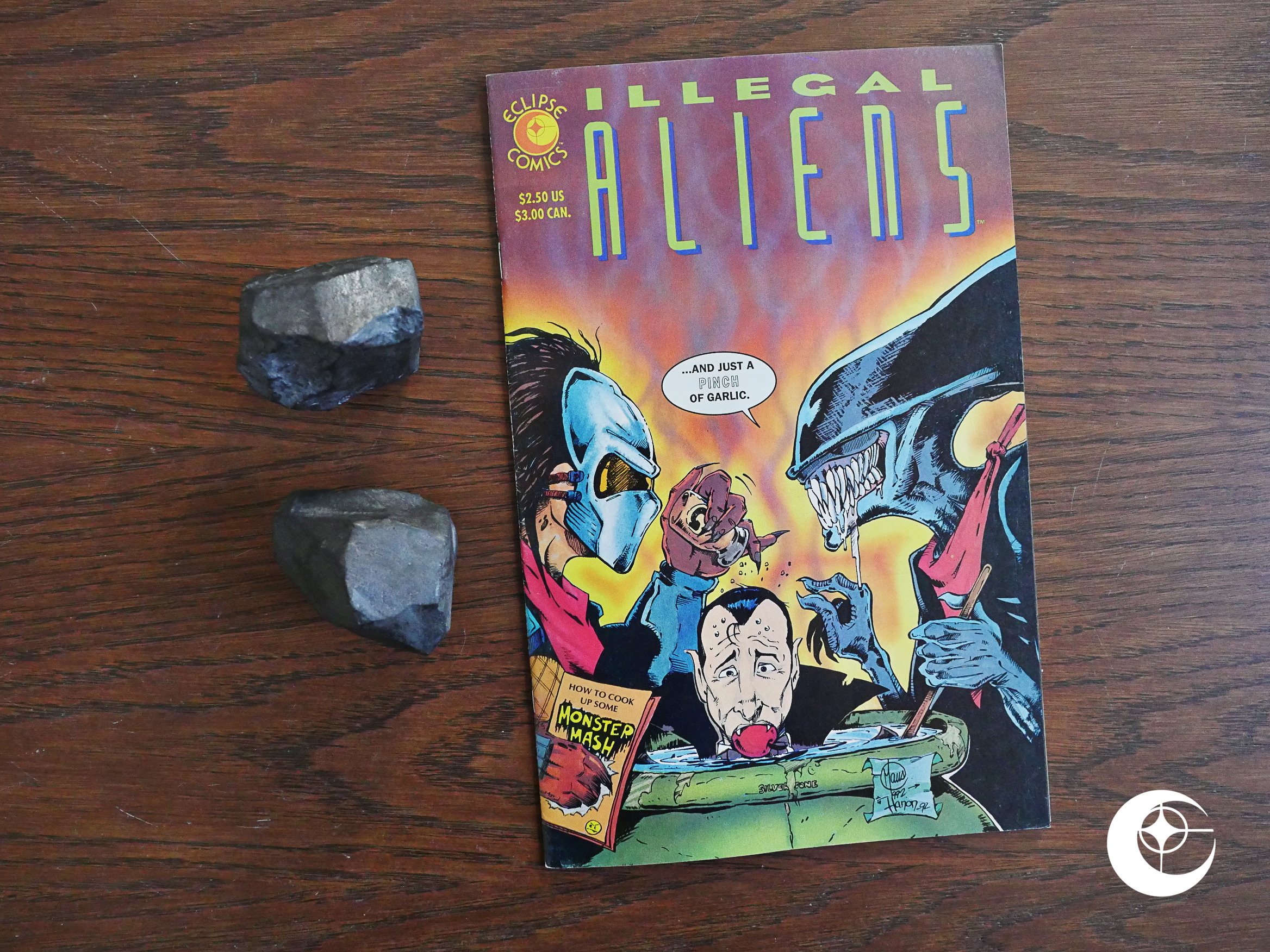

Loco vs. Pulverine (1992) #1 Illegal Aliens (1992) #1

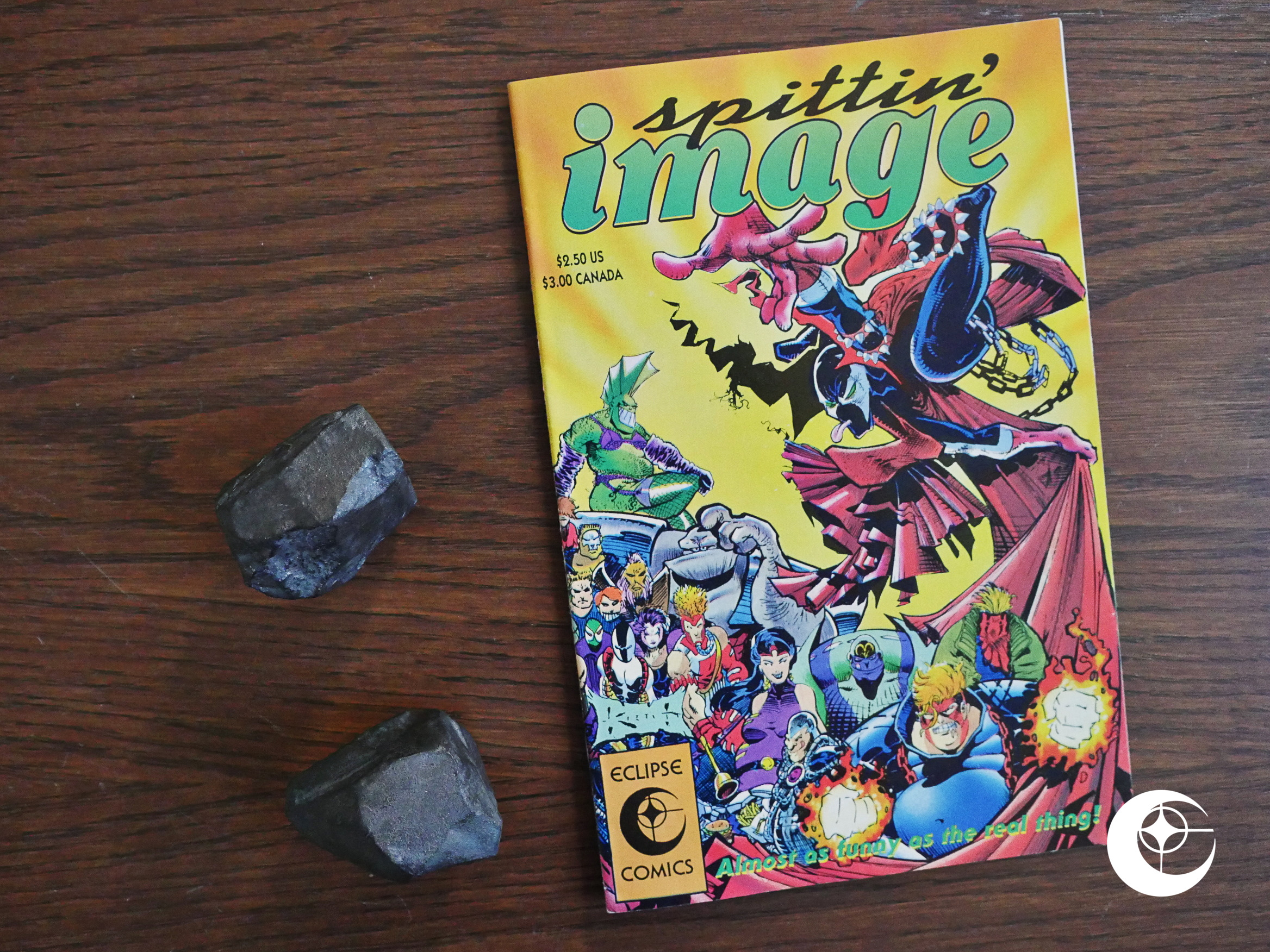

Illegal Aliens (1992) #1 Spittin’ Image (1992) #1

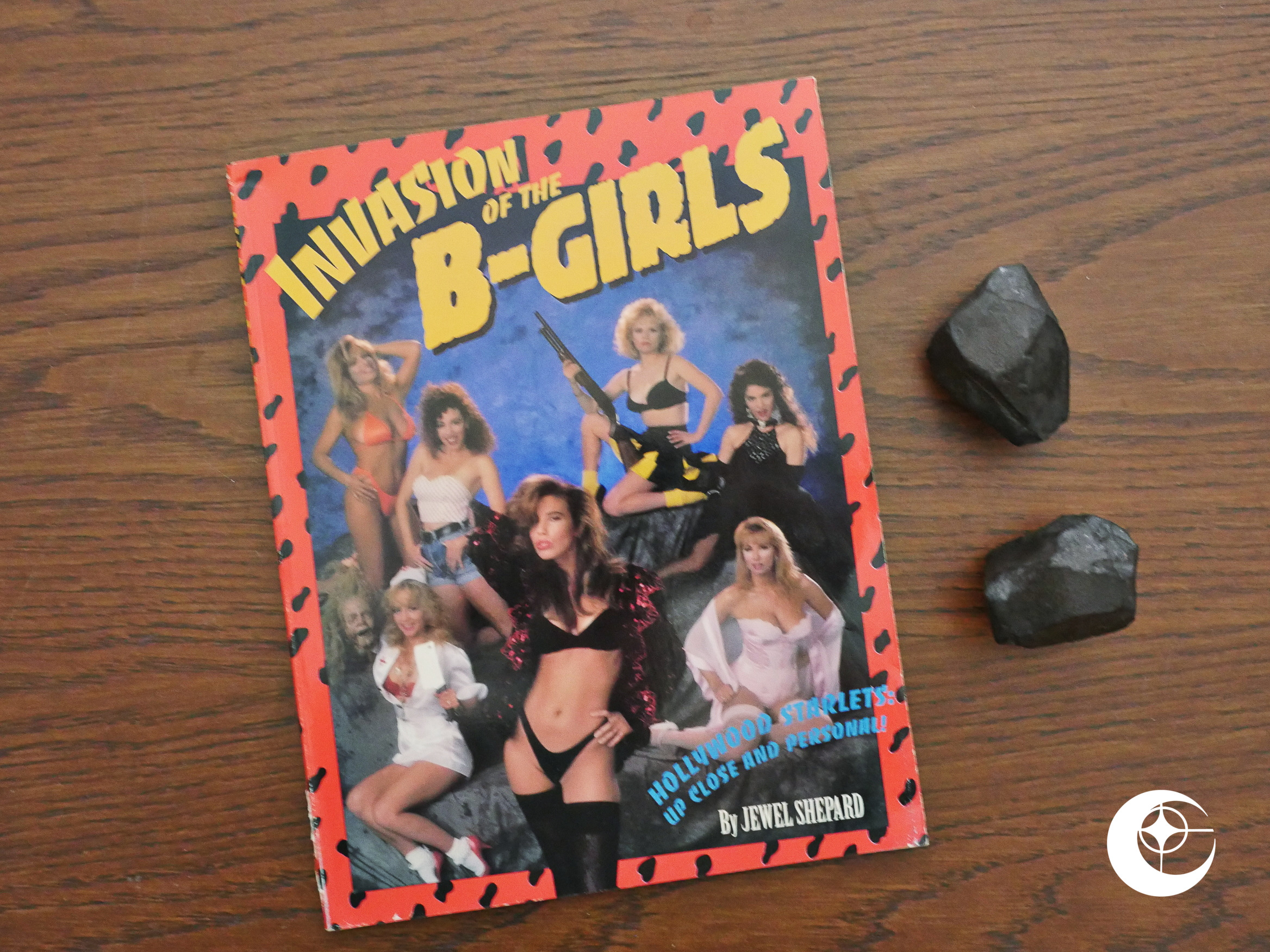

Spittin’ Image (1992) #1 Invasion of the B-Girls (1992)

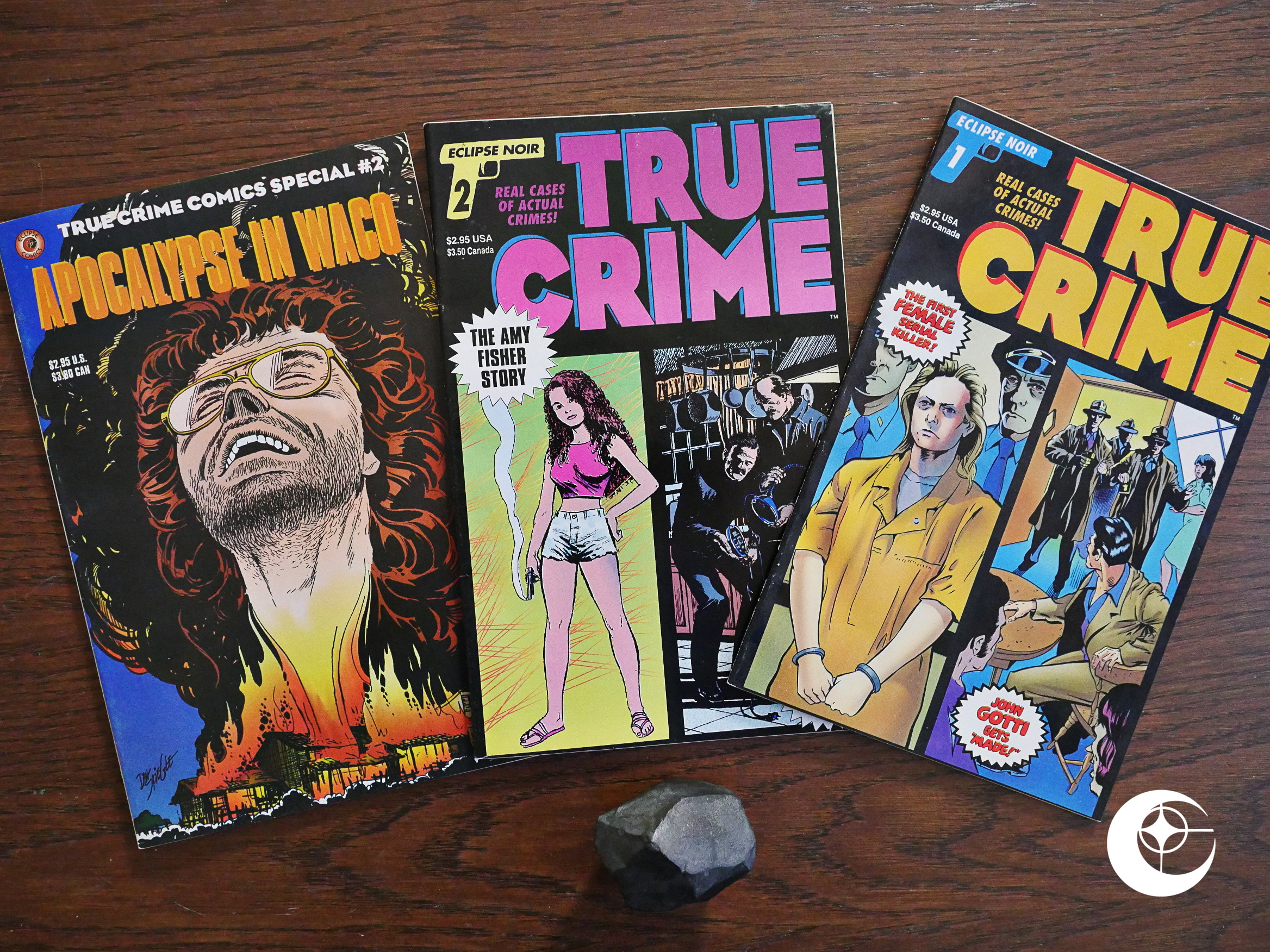

Invasion of the B-Girls (1992) True Crime Comics (1993) #1-2

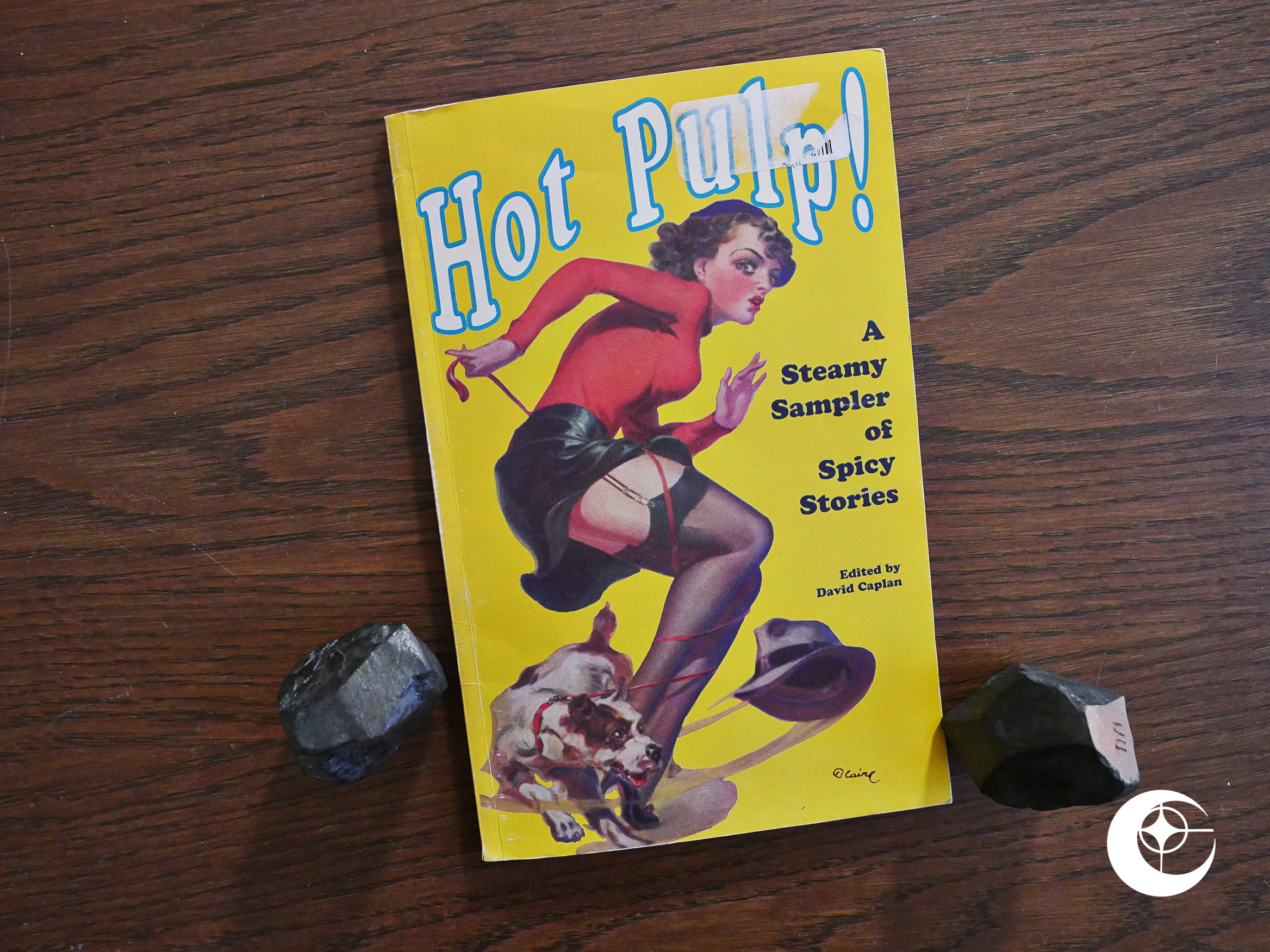

True Crime Comics (1993) #1-2 Hot Pulp (1993)

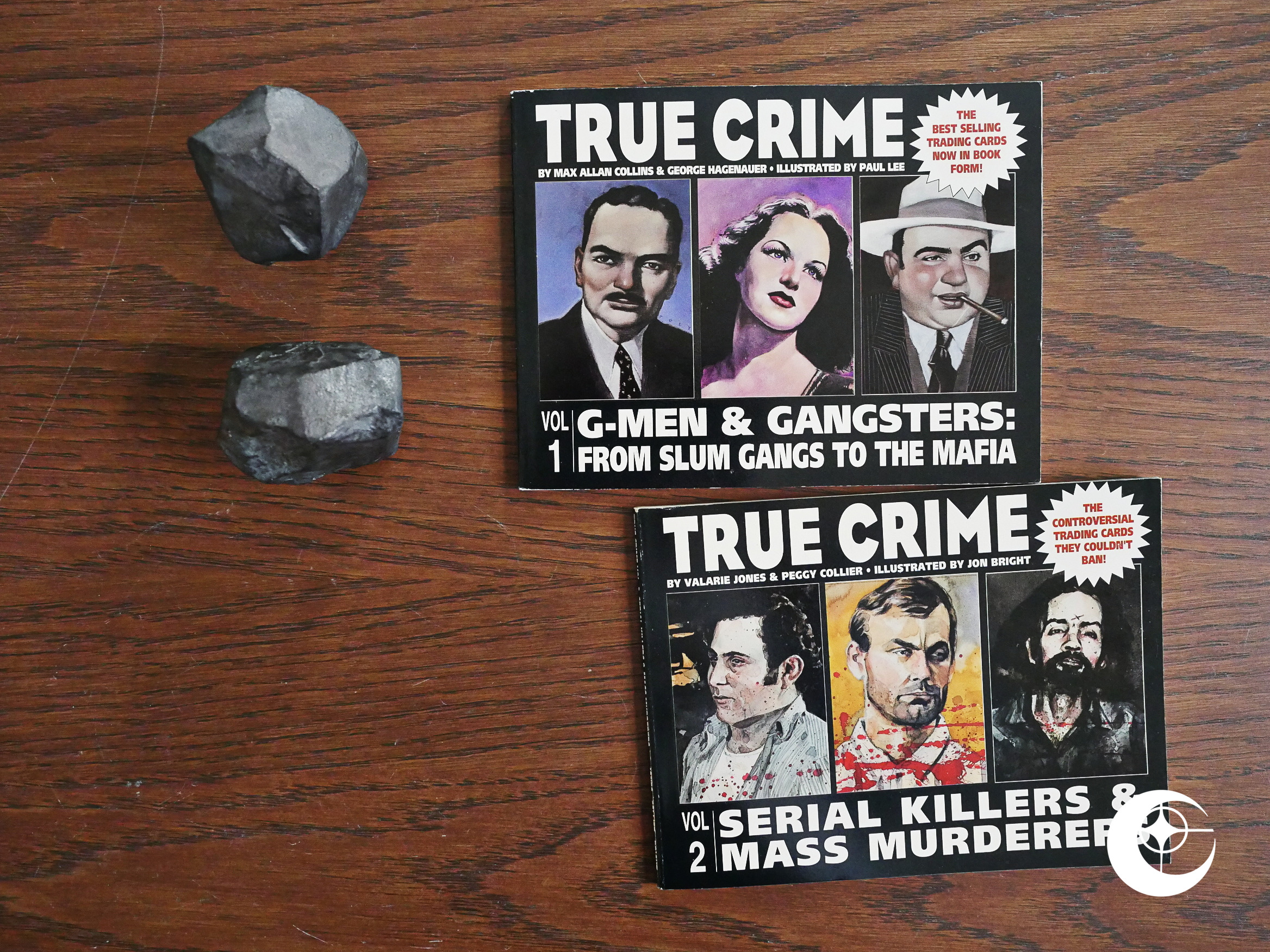

Hot Pulp (1993) True Crime (1993) #1-2

True Crime (1993) #1-2 Elvira, Mistress of the Dark (1993) #1-11

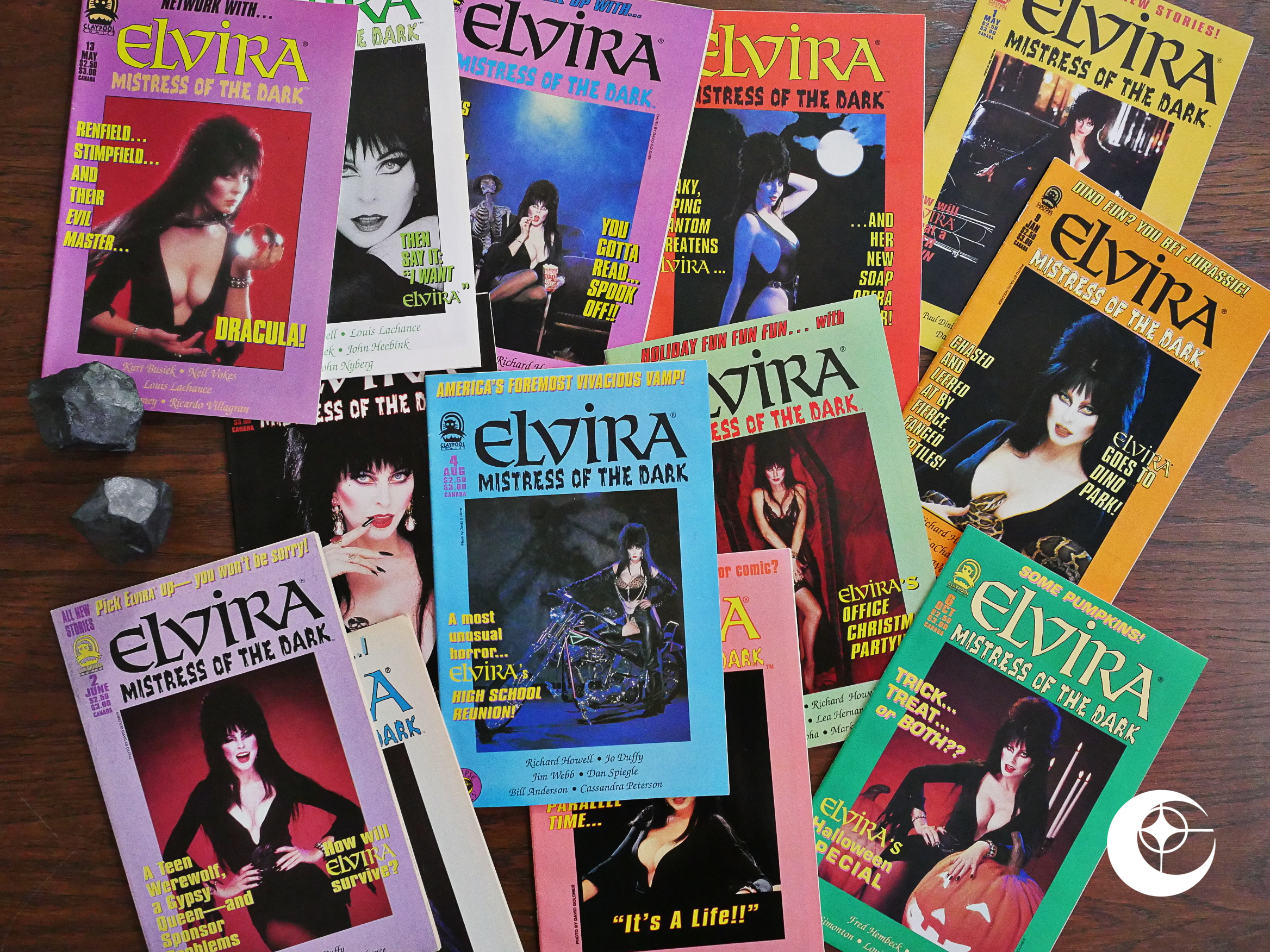

Elvira, Mistress of the Dark (1993) #1-11 Phantom of Fear City (1993) #1-6

Phantom of Fear City (1993) #1-6 Soulsearchers and Company (1993) #1-6

Soulsearchers and Company (1993) #1-6 Deadbeats (1993) #1-6

Deadbeats (1993) #1-6 Trapped (1993)

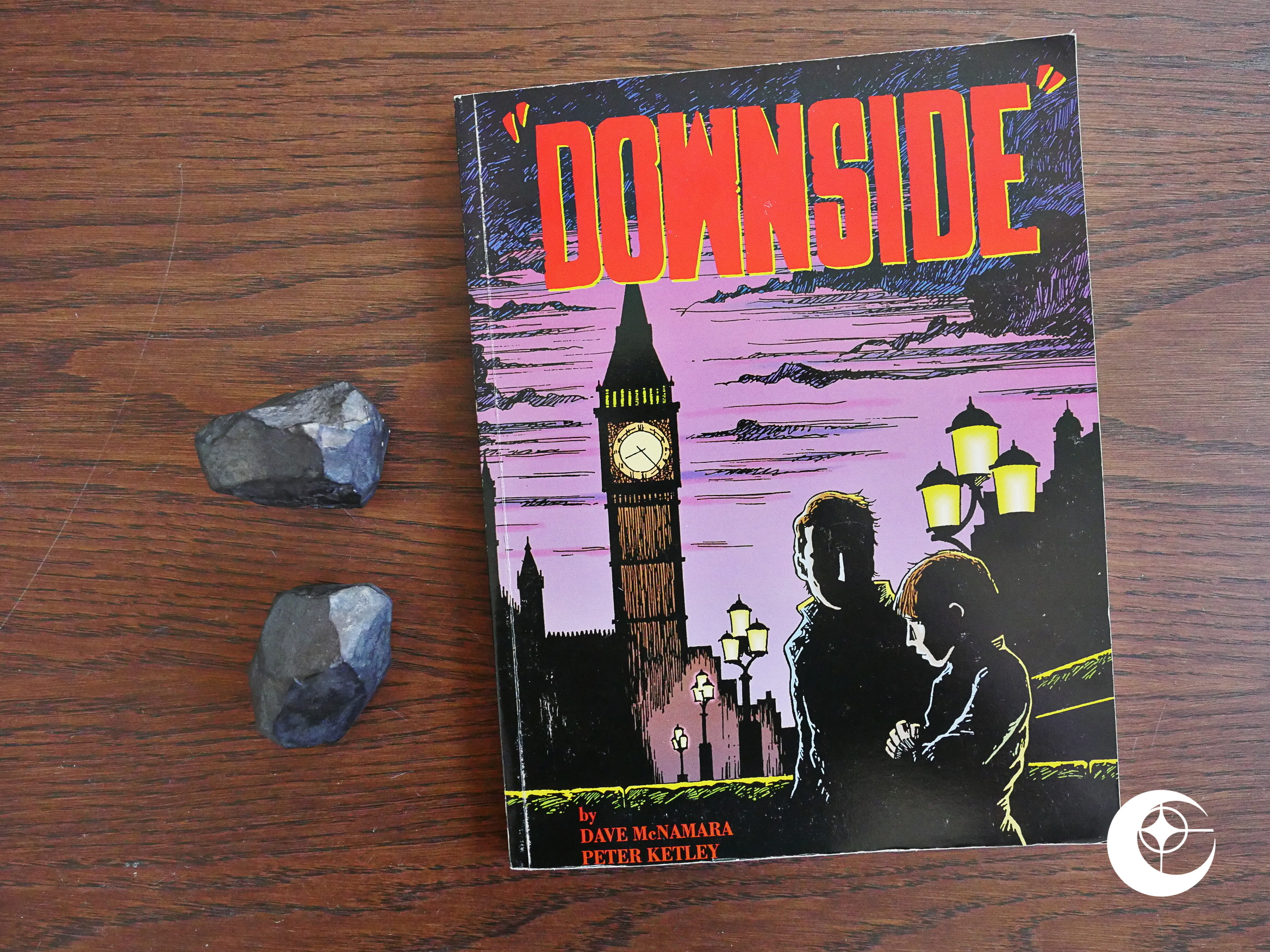

Trapped (1993) Downside (1993)

Downside (1993) Rawhead Rex (1994)

Rawhead Rex (1994)

Bummer. A tragic end which leaves me wondering, did Harper ever offer an explanation for their apparent failure to honor their side of the deal?

I tried googling quite a bit to see whether anybody had spoken to HarperCollins about the allegations made by Dean Mullaney, but I couldn’t find anything. But this was in 1993-94, and not everything is on the web.

Somebody should interview the parties involved before it becomes to late…

It did strike me as strange that Dean Mullaney did not take legal action when faced with such a disaster. But, of course, he would have needed funds to pay the lawyer$ and Eclipse was totally strapped for cash…

Did you ask him about this?

I just read comics and write a bit. I haven’t talked to anybody. 🙂

Pingback: lucalorenzon.blogspot.com