In 1994, Eclipse Comics went bankrupt, and there are two conflicting stories why.

Here’s owner Dean Mullaney’s take:

We never—EVER—received a single sales statement. Therefore, no royalty statements. So there I was, paying advances to creators (bigger than the top rates in the field at the time—hey, we were going to be in bookstores, too!), tying up all my capital. And then nothing from Harper. No statements, no money. Meanwhile, creators were naturally asking for THEIR statements and royalitites. I explained the situation, but still never got anything from Harper. It go to the point that I had no cash left to even carry on normal business because we had laid out everything we had for advances.

All that was left to do was sell off every piece of inventory I could get my hands on, pay all the little guys (individual creators and small vendors), and stiff the large ones (printers and freight companies). And declare bankruptcy.

When Toren took the licence away from Eclipse and went to Dark Horse, he suddenly discovered that he was making four or five times as much money! But the sales had not gone up and the deal was pretty much the same. So then he got his accountant or his lawyer to get in touch with Eclipse to say, ‘Please send me all the figures so we can do an audit.’ And Eclipse sent both sets of books, the one with the true figures and the false figures. Given that Toren had the true figures and the false figures, he took them to court and the judgement… it was pretty much an open-and-shut case. There was a $100,000 judgement against Eclipse.

Now, this is hearsay, of course, but that’s quite a story, and I wondered whether there might be an easy way to verify whether it’s true or not. So I outsourced to an er American er associate the task of getting the case information: Toren Smith sued Eclipse Enterprises in a California court, so that should be easy enough, right?

Nine months later, I finally have the papers!

And instead of building the suspense here in this blog article, I’m just going to state my findings up front: There’s nothing in these papers to either support or invalidate Gaiman’s summary of the story.

So that’s a major disappointment.

Either American court cases are just plain weird, or Toren Smith’s lawyers are weird.

But while the papers don’t tell me what I wanted to know, they’re kinda interesting in other ways, so let’s just go through them for amusing bits. I’ve scanned all the documents and you can download the PDFs from the links below if you want to read them. But I’ll summarise.

First of all, there’s an index of sorts that lists all the documents available in the case. I didn’t get all of them, but the ones that are missing do not seem very likely to have anything interesting in them, but there’s always the possibility that I just didn’t get the right papers.

The meat of the matter is in the complaint. It’s a series of numbered allegations from Toren Smith, like:

Basically the first few pages state that Jan and Dean Mullaney are responsible for whatever Eclipse Enterprises do, which seems uncontroversial enough. Then there’s a couple of section for each series Toren Smith translated for Eclipse (Black Magic, Appleseed, etc) like this:

Finally, at allegation 40 we get something:

OK, Smith alleges that Eclipse has failed to pay him (and the Japanese owners of the comics).

But how did Smith know that Eclipse failed to pay him?

“has thereby been damagen in the amount of not less than Thirty Nine Thousand Six Hundred Seventy Three Dollars and 24/100 ($39,673.24) with the exact amount to be determined according to proof”. (This is just for Appleseed; there’s a section like this for each of the series Smith was involved with.)

So that’s a weirdly specific amount, which lends some credence to the story from Gaiman that Smith had received both sets of books (real and fake) from Eclipse. On the other hand, it says “to be determined according to proof”, so perhaps that’s just a number Smith’s lawyers pulled out of their asses.

The sum of all these unexplained allegations is $150,561.66:

Again with the “according to proof”. Is this a done thing? You start a court case without even a hint of proof of misdoing, but just allege a bunch of things, and then you do the proof during the court case itself? Giving away what the proof is give the opponent a heads up and you don’t want to do that?

There’s nothing in this complaint to even hint at how Smith knows that Eclipse done him wrong, and if this was how I was being sued, I would scratch my head and say “eh? what?”

This is more or less what Eclipse’s lawyer, Daniel Kornbluth, Esq. does in the answer, but he’s less long-winded than Smith’s lawyers:

And then does “uhm?” on a bunch of other allegations:

Kornbluth manages to get in a zinger or two:

Heh heh.

But, finally, the answer to the meat of the suit:

The “er, what?” part of the answer: Kornbluth points of that the suit doesn’t really state any facts that they can act on.

Which seems like the correct response to me.

And then there’s a bunch of (what I take to be) copypasta defenses, like:

If it had been the doctrine of leaches, it would have been funnier.

And that’s it: There’s no further evidence, either for or against Eclipse, presented in these papers. But the documents keep rolling in. First of all, Smith wants an injunction against Eclipse to stop them from

liquidating their assets:

As proof of this, they include two articles from The Comics Journal about Eclipse’s problems… and a letter from Jan Mullaney to Smith where Mullaney seems to say that he’s working on paying Smith (if Smith is willing to settle for $50K), but Smith takes this to mean that he’s doing nothing of the kind:

Which is kinda mind boggling. Here’s the letter:

I’m guessing this declaration from Smith is his way of saying “no thanks”.

Kornbluth responds by saying that the parties had been involved in a settlement negotiation, but that Smith’s lawyers were being unreasonable:

And that they’re using this process (“Ex Parte Temporary Protective Order”) to blackmail Eclipse into settling on terms impossible for them.

Dean Mullaney files a similar declaration, where he says that he still doesn’t know exactly how Smith came up with the sums he’s suing Eclipse for:

And that the Ex Parte was blackmail:

And he disputes that Eclipse is selling off assets in an attempt to defraud Smith:

Then there’s a stipulation that a judge is a judge.

But then, on May 3rd, two weeks after the Ex Parte, there’s a

“stipulation for entry of judgment”, which seems to be… an agreement between Eclipse and Toren Smith as how they’re going to pay him all this money. I can’t see anything in there where Eclipse admits to owing him money, but they’re going to pay him… and under severe conditions.

But first of all, the Ex Parte thing was “held in abeyance” by the judge:

The agreement between the parties say that Kornbluth will establish an escrow account:

And here’s the terms of payment:

Basically, Smith will get all the money that Eclipse earns through any channel. Except back issue sales, for some reason. These are terms that are impossible for any company do business on. Eclipse can keep only $500; all the rest are belong to Smith.

The rest of these 16 pages describe in perverse minutiae (was Smith’s lawyer’s paid by the page?) how Eclipse are to do this, and what the consequences are if they fail to pay Smith. I have to admit I only skimmed this document, because it’s paranoid and perverse:

And on and on:

There’s a personal obligation for the Mullaneys, too:

The final document is “Judgment pursuant to stipulation for entry of judgment” (phew) from September 30th, 1994. It’s short:

Paragraph 13 is the one that says that if Eclipse fails to pay Smith according to the schedule, then Smith should get all the money immediately.

So that’s what the judge does now:

Eclipse has to pay Smith $122,328.59.

This lines up somewhat with what Gaiman said:

They paid it for one month, they paid it for a second month, but when the third month happened there was no payment forthcoming. Dean and Jan had cleaned out Eclipse and let it close down.

The documents don’t really say how long Eclipse kept paying Smith, though.

So there you are: The court documents are frustratingly vague on what actually happened and how the parties knew they were happening.

Eclipse’s lawyers seem like better lawyers than Smith’s, though, so my guess would be that Smith had the facts on his side… Otherwise they wouldn’t have folded the way they did.

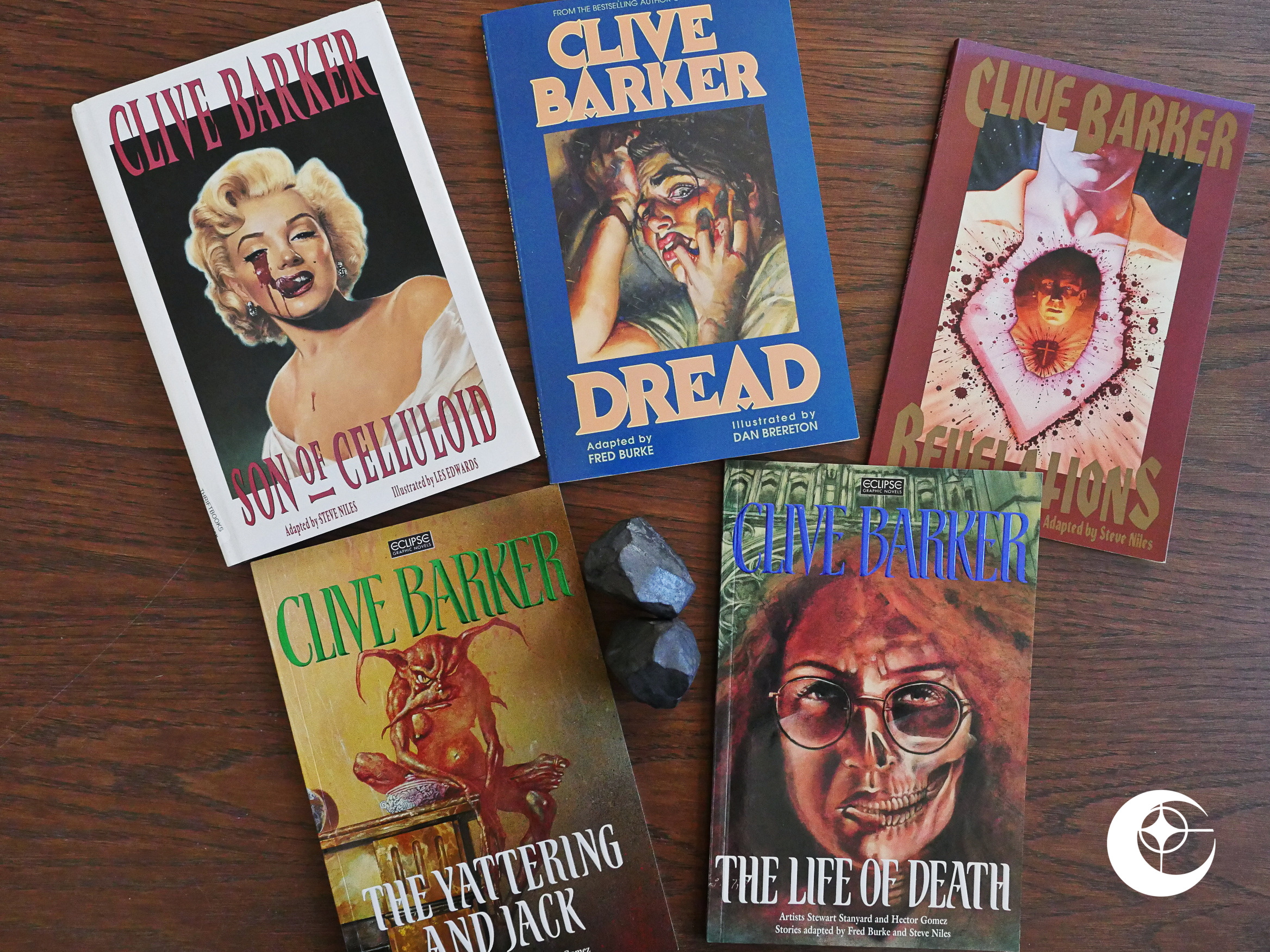

The Yattering and Jack (1991)

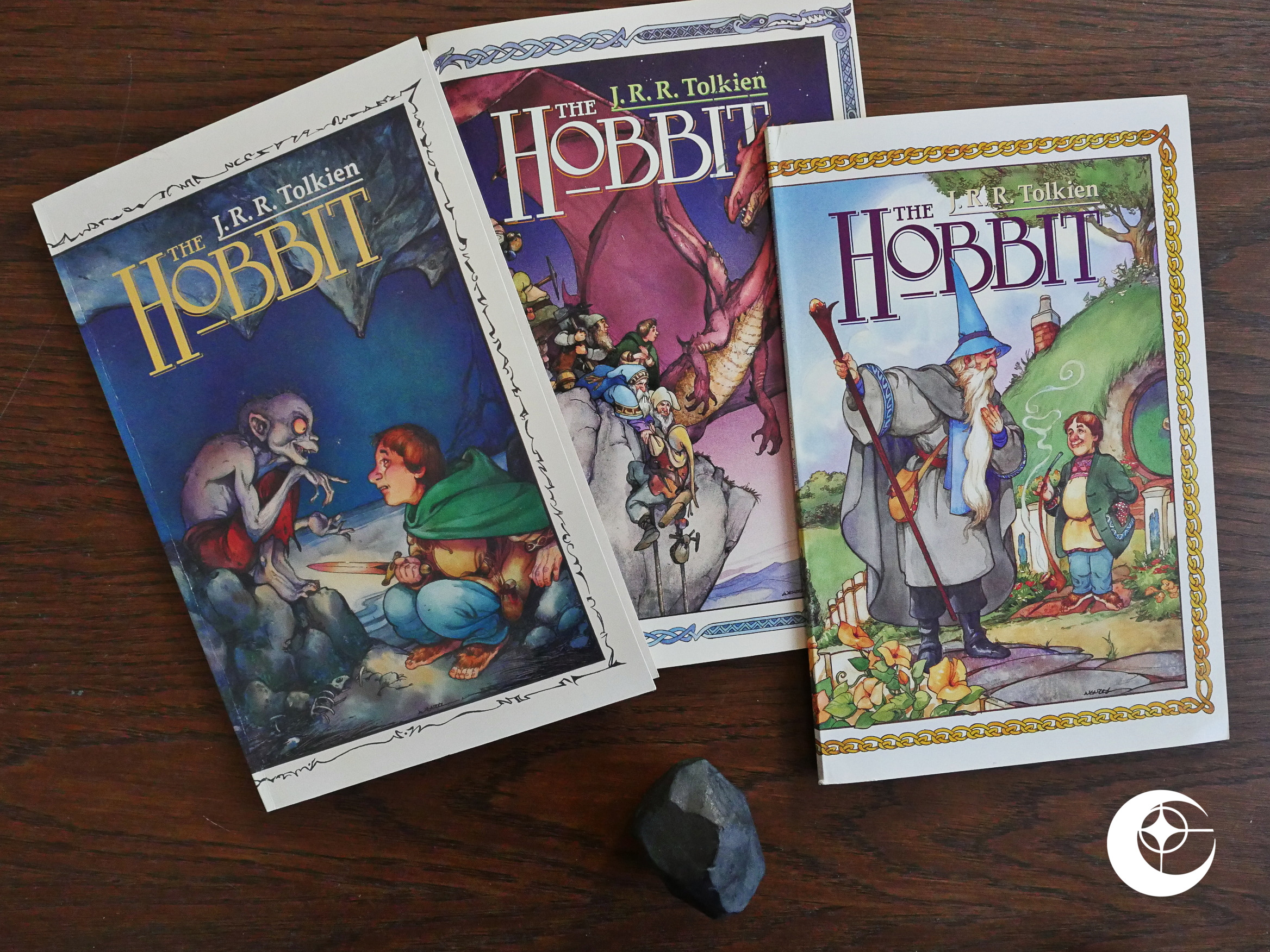

The Yattering and Jack (1991) The Hobbit (1993)

The Hobbit (1993) Miracleman: The Golden Age (1993)

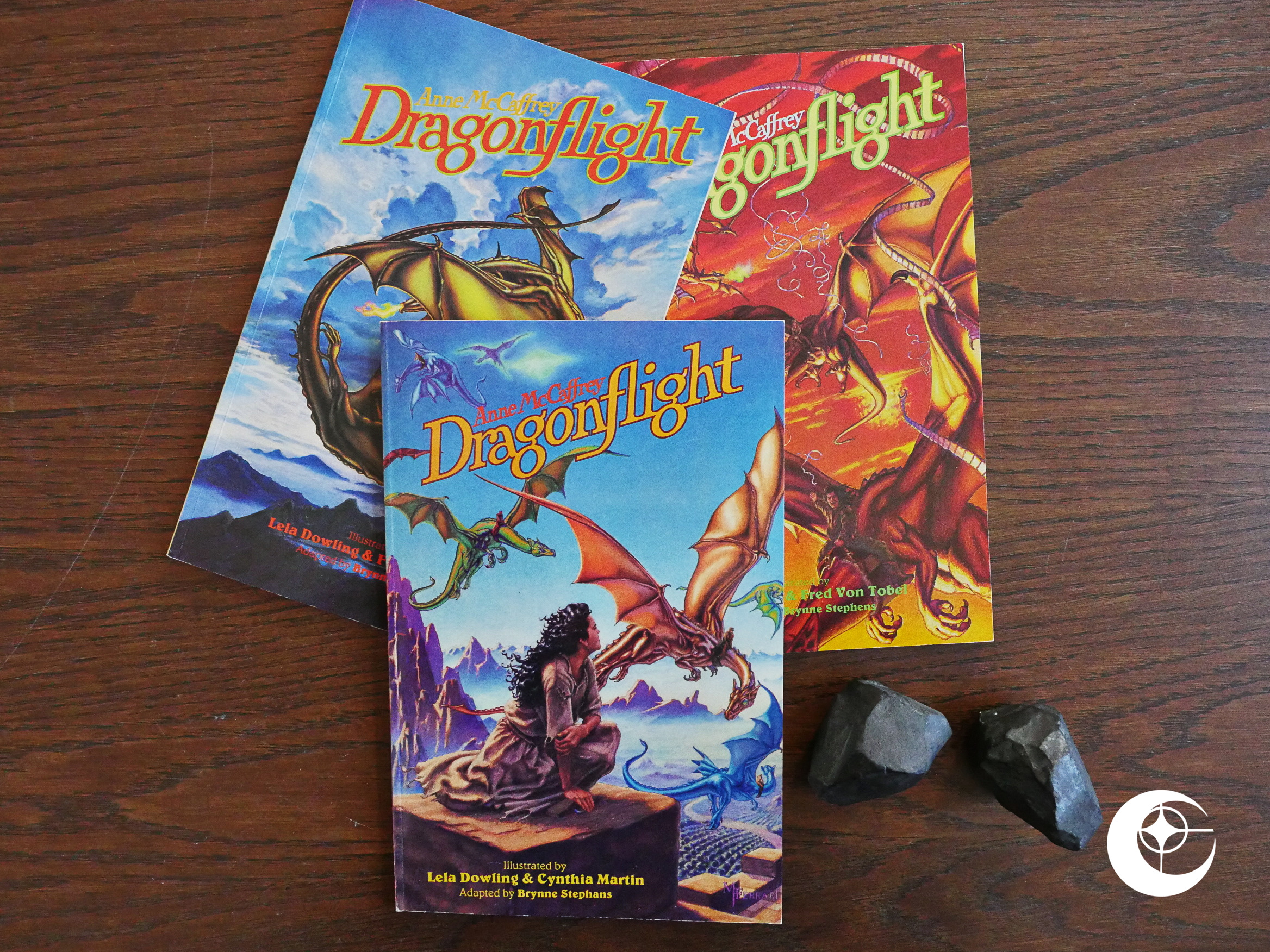

Miracleman: The Golden Age (1993) Dragonflight (1993)

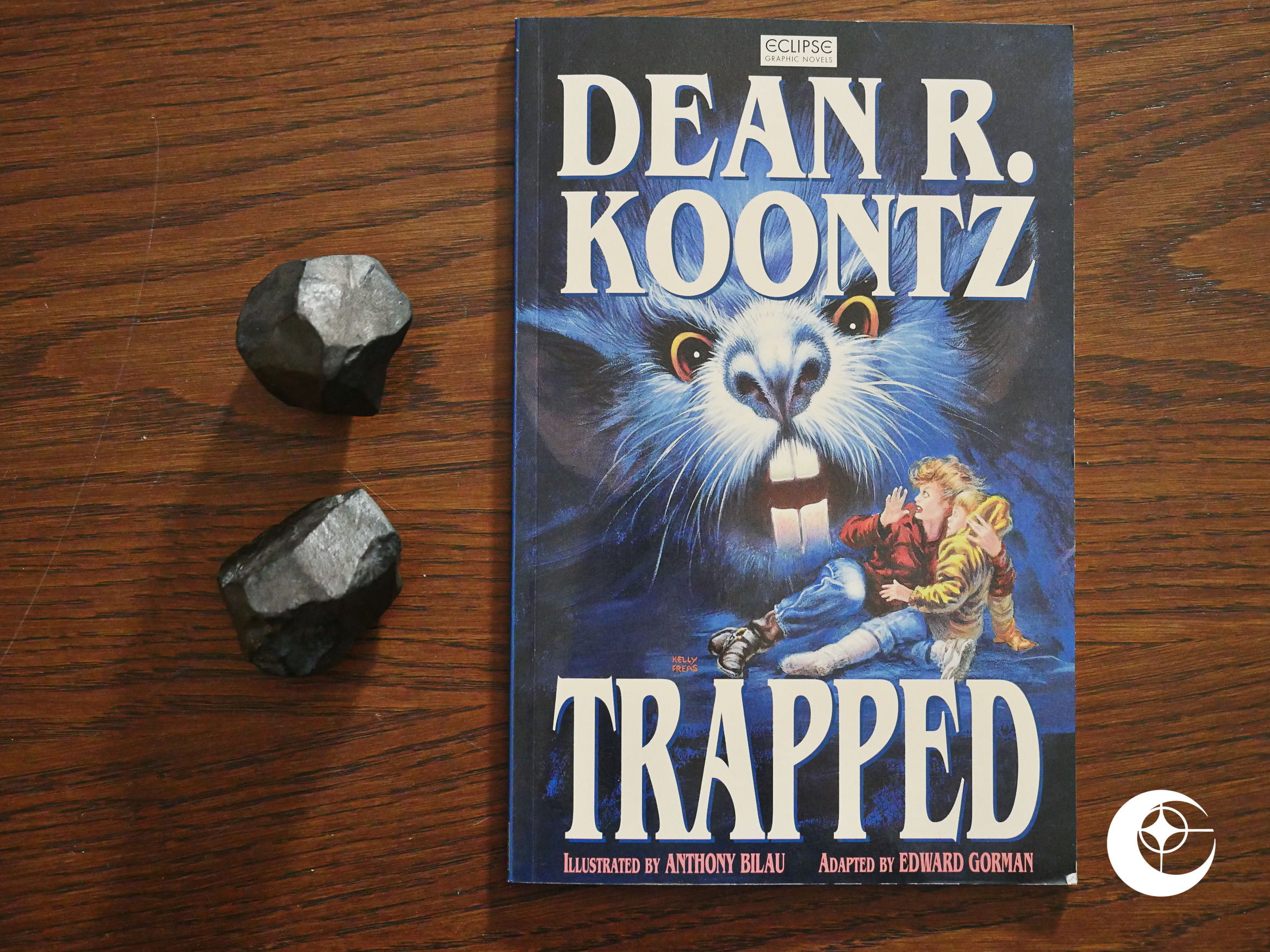

Dragonflight (1993) Trapped (1993)

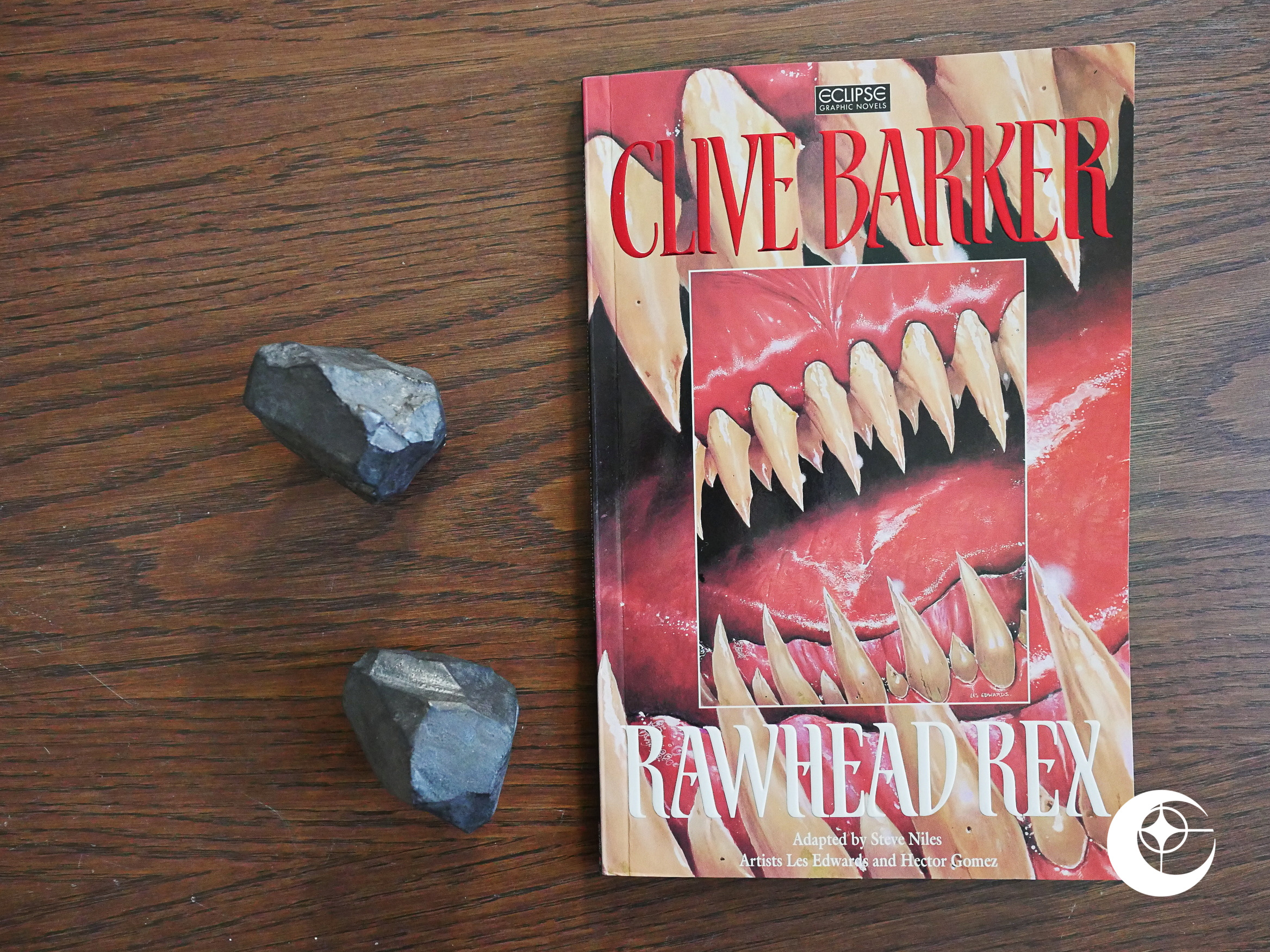

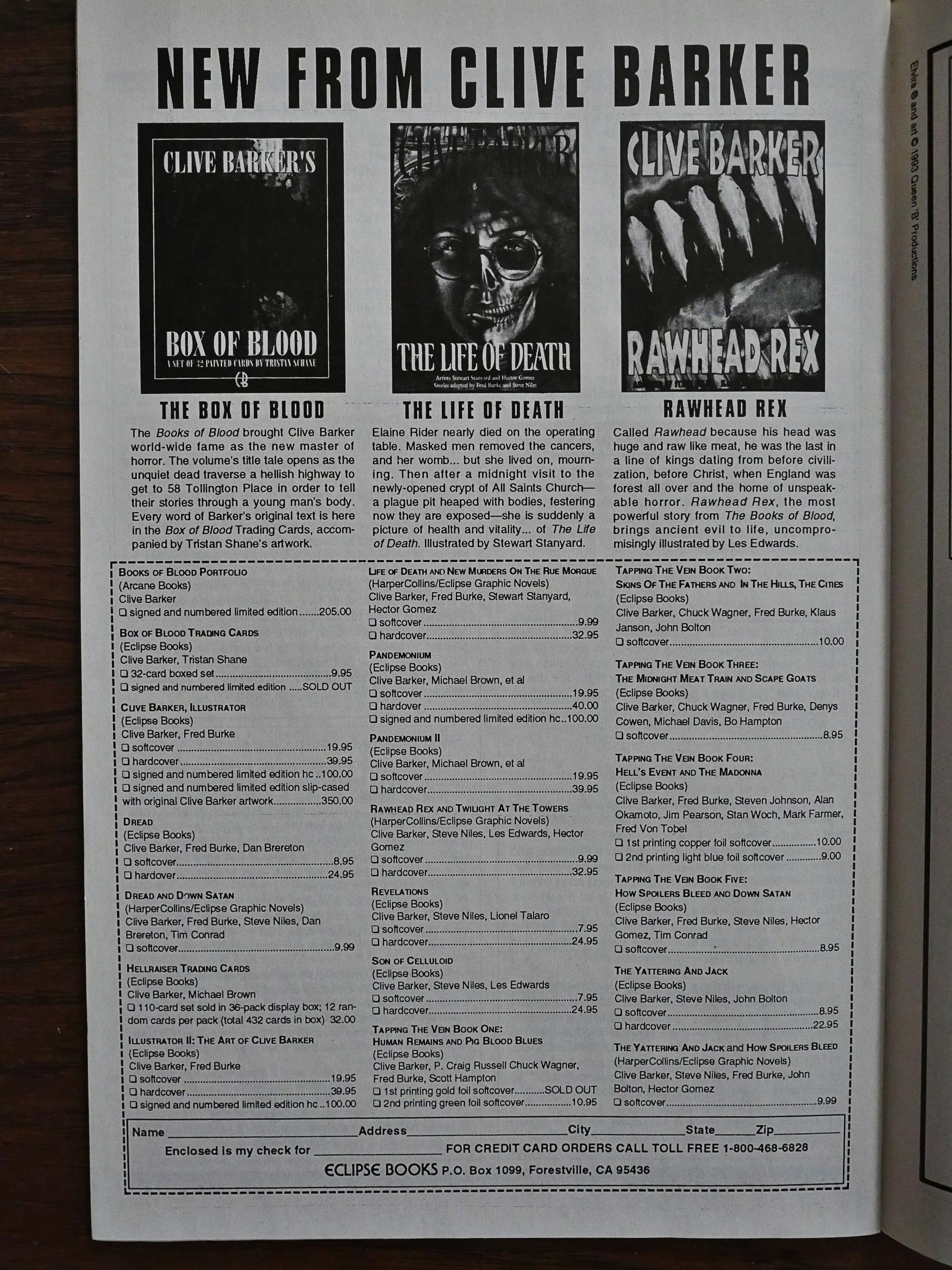

Trapped (1993) Rawhead Rex (1994)

Rawhead Rex (1994)

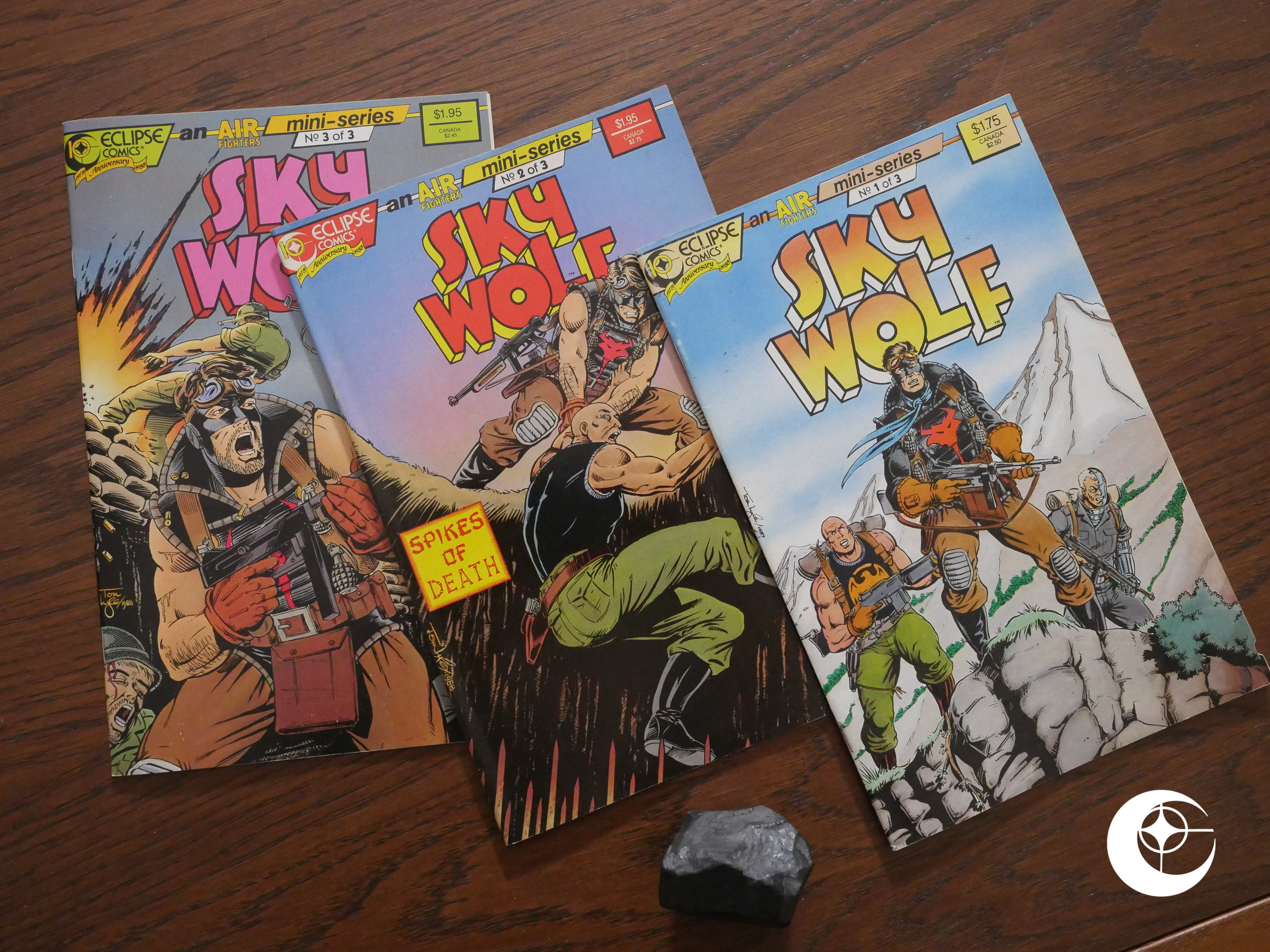

Airboy (1986) #1-50

Airboy (1986) #1-50 Airboy-Mr. Monster Special (1987) #1

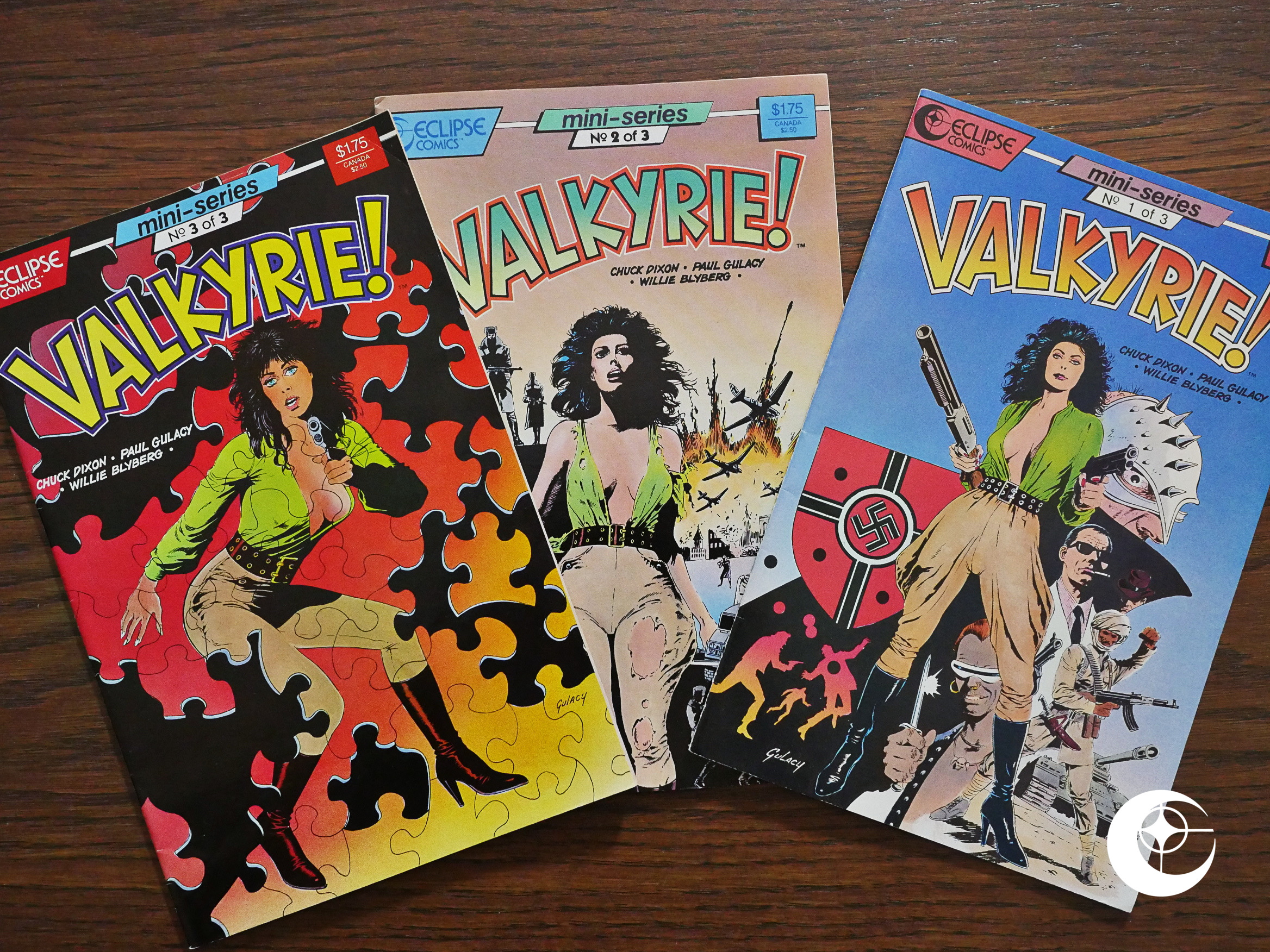

Airboy-Mr. Monster Special (1987) #1 Valkyrie! (1987) #1-3

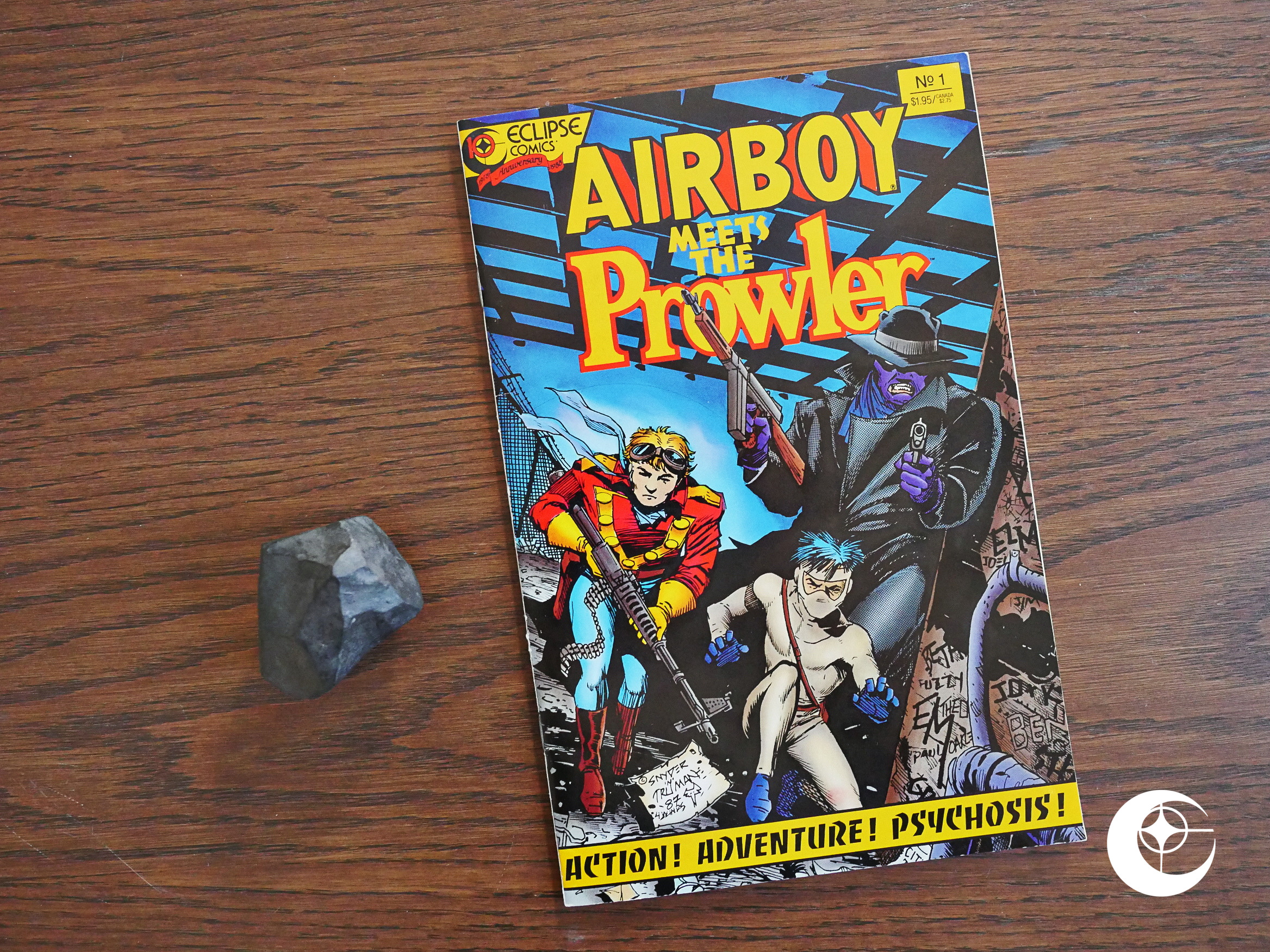

Valkyrie! (1987) #1-3 Airboy Meets the Prowler (1987) #1

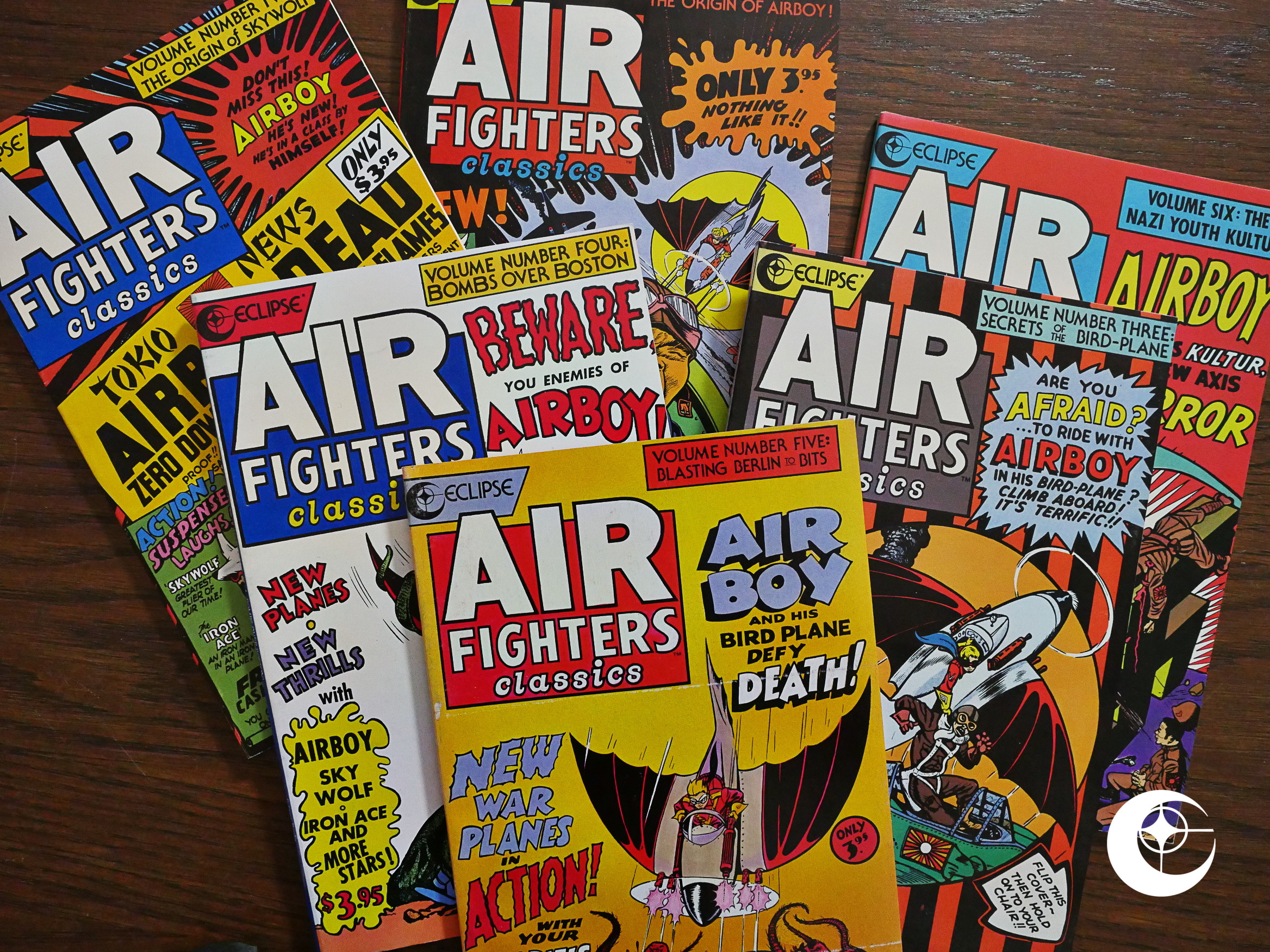

Airboy Meets the Prowler (1987) #1 Air Fighters Classics (1987) #1-6

Air Fighters Classics (1987) #1-6 Target: Airboy (1988) #1

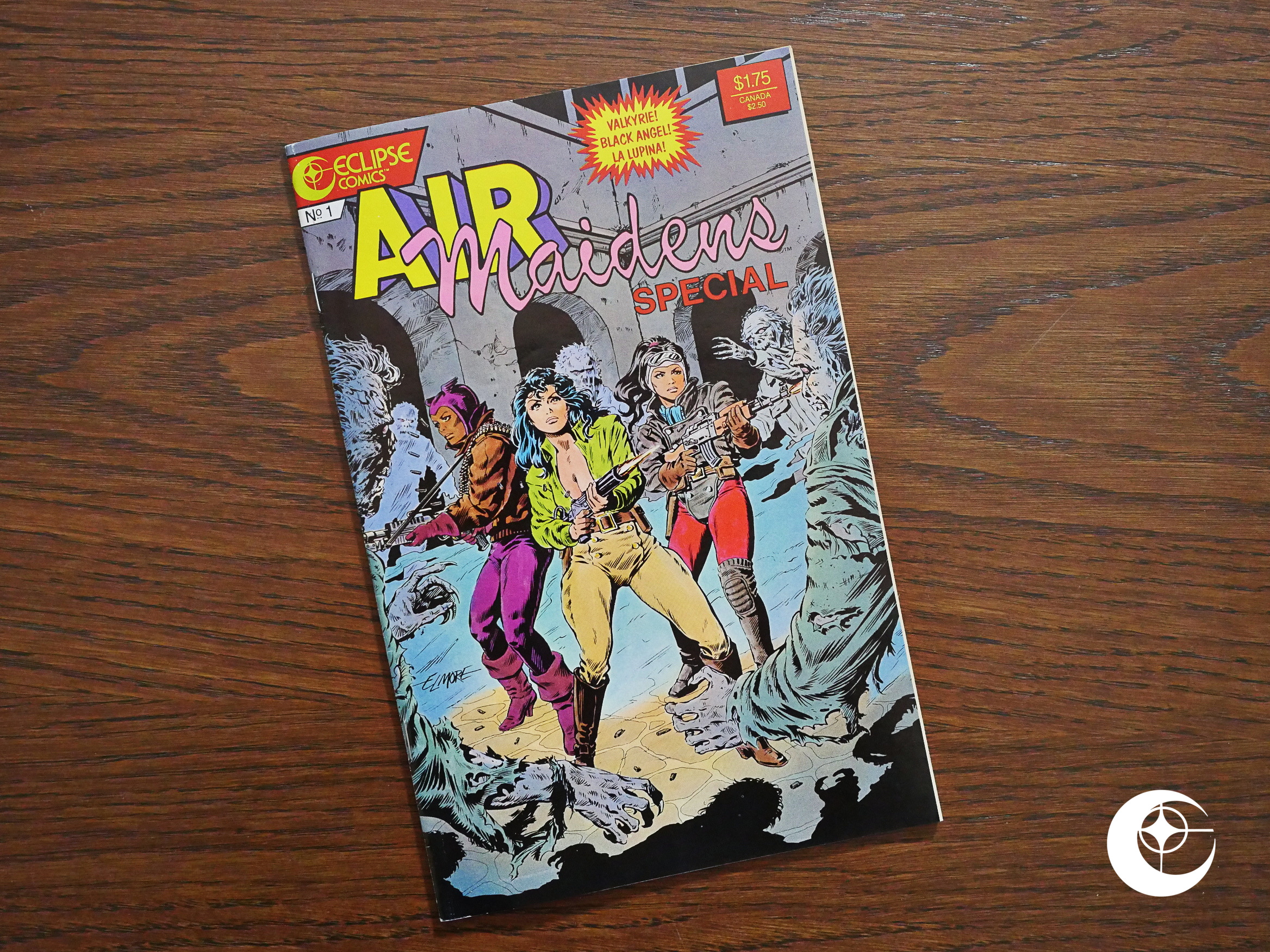

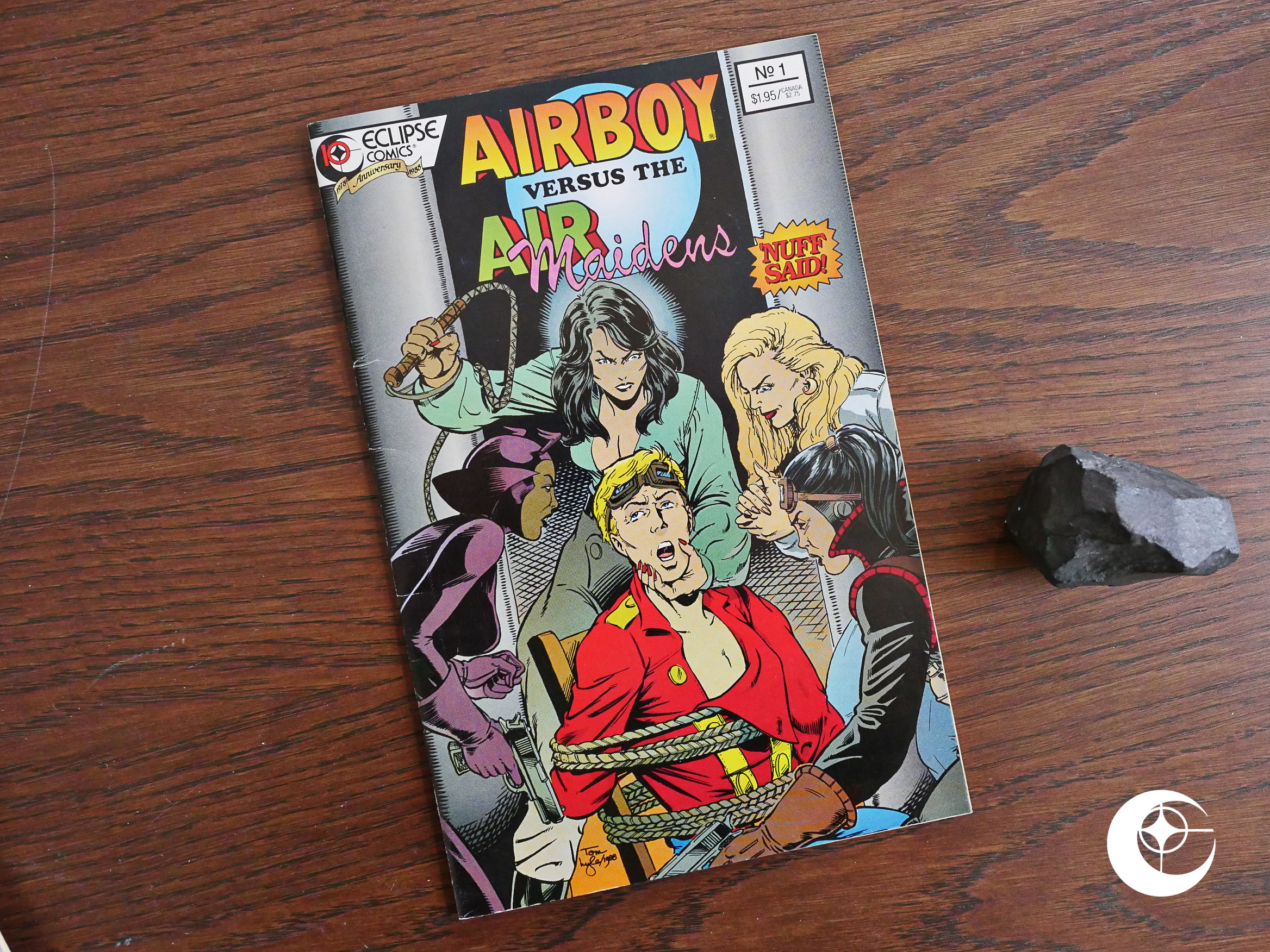

Target: Airboy (1988) #1 Airboy versus the Airmaidens (1988) #1

Airboy versus the Airmaidens (1988) #1 Valkyrie! (1988) #1-3

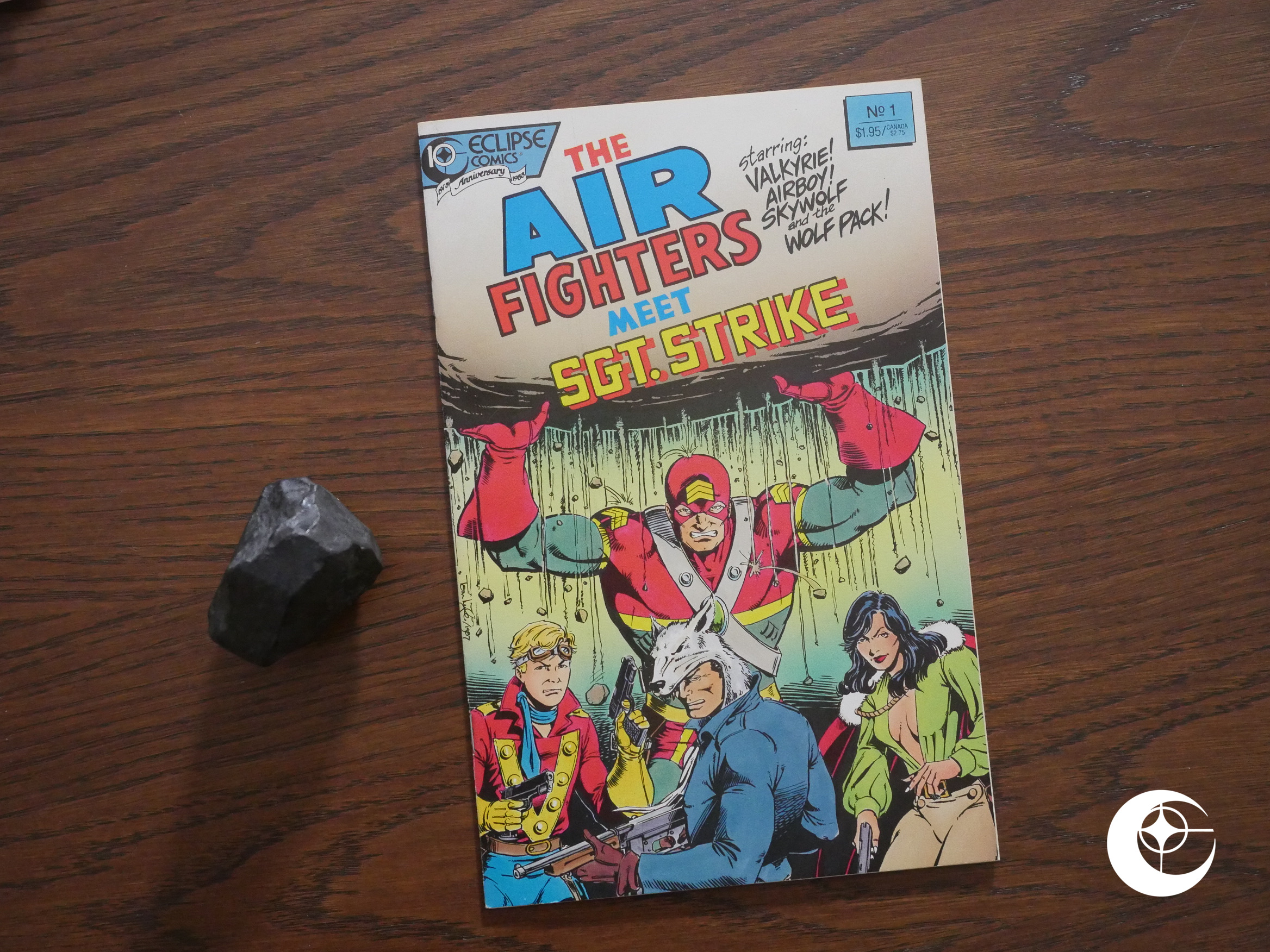

Valkyrie! (1988) #1-3 The Airfighters Meet Sgt. Strike Special (1988) #1

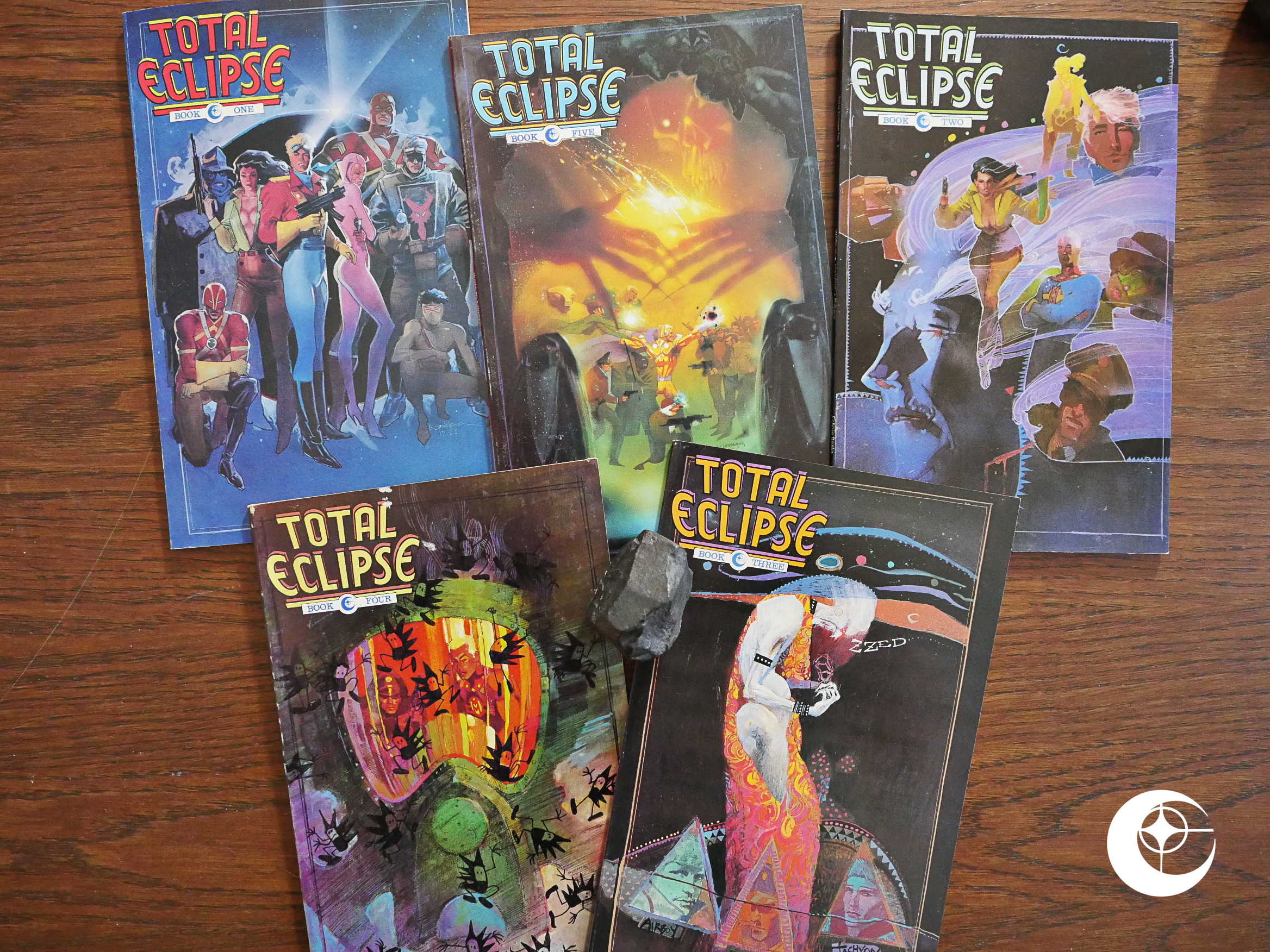

The Airfighters Meet Sgt. Strike Special (1988) #1 Total Eclipse (1988) #1-5

Total Eclipse (1988) #1-5

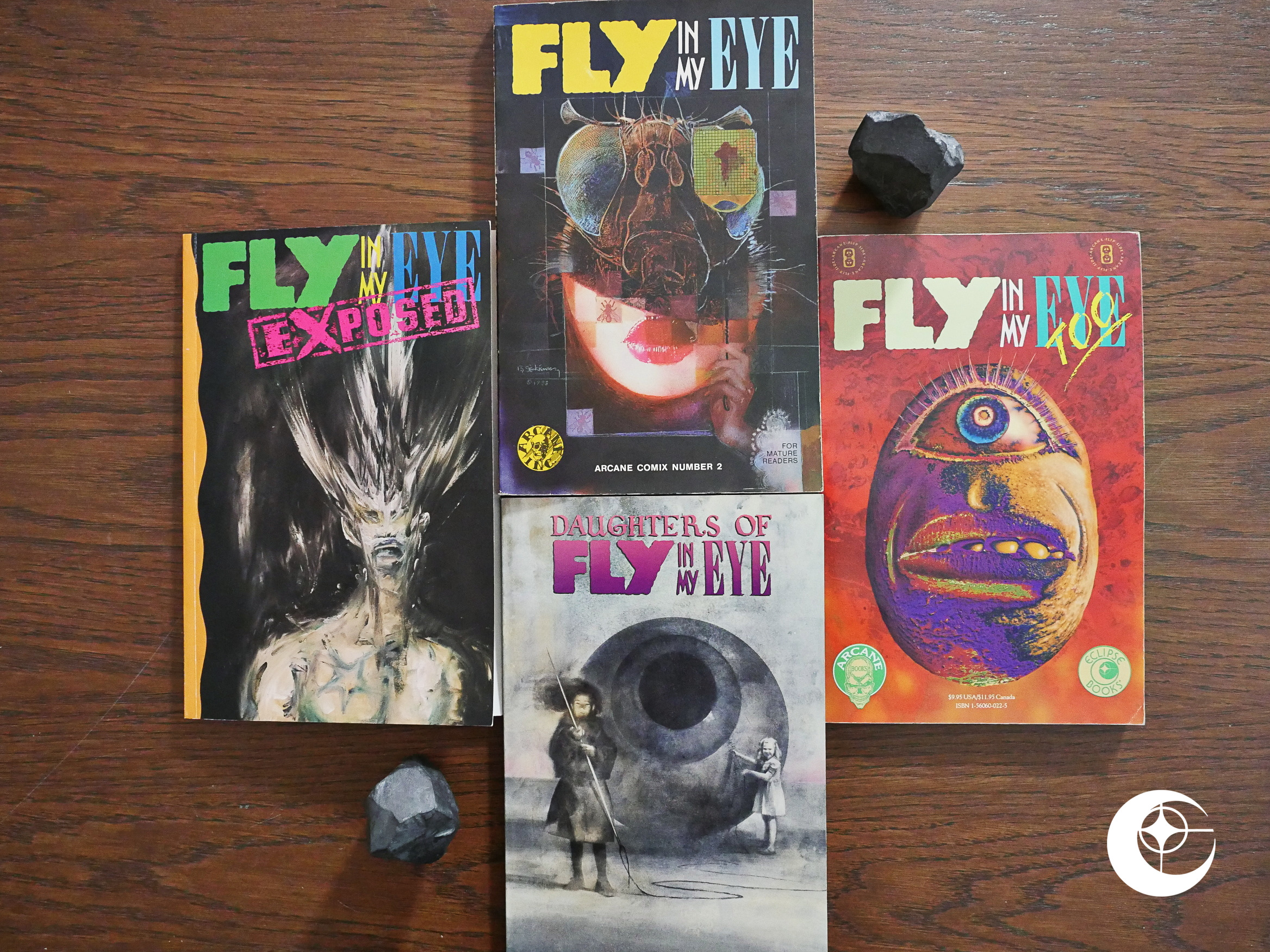

Fly in My Eye (1988)

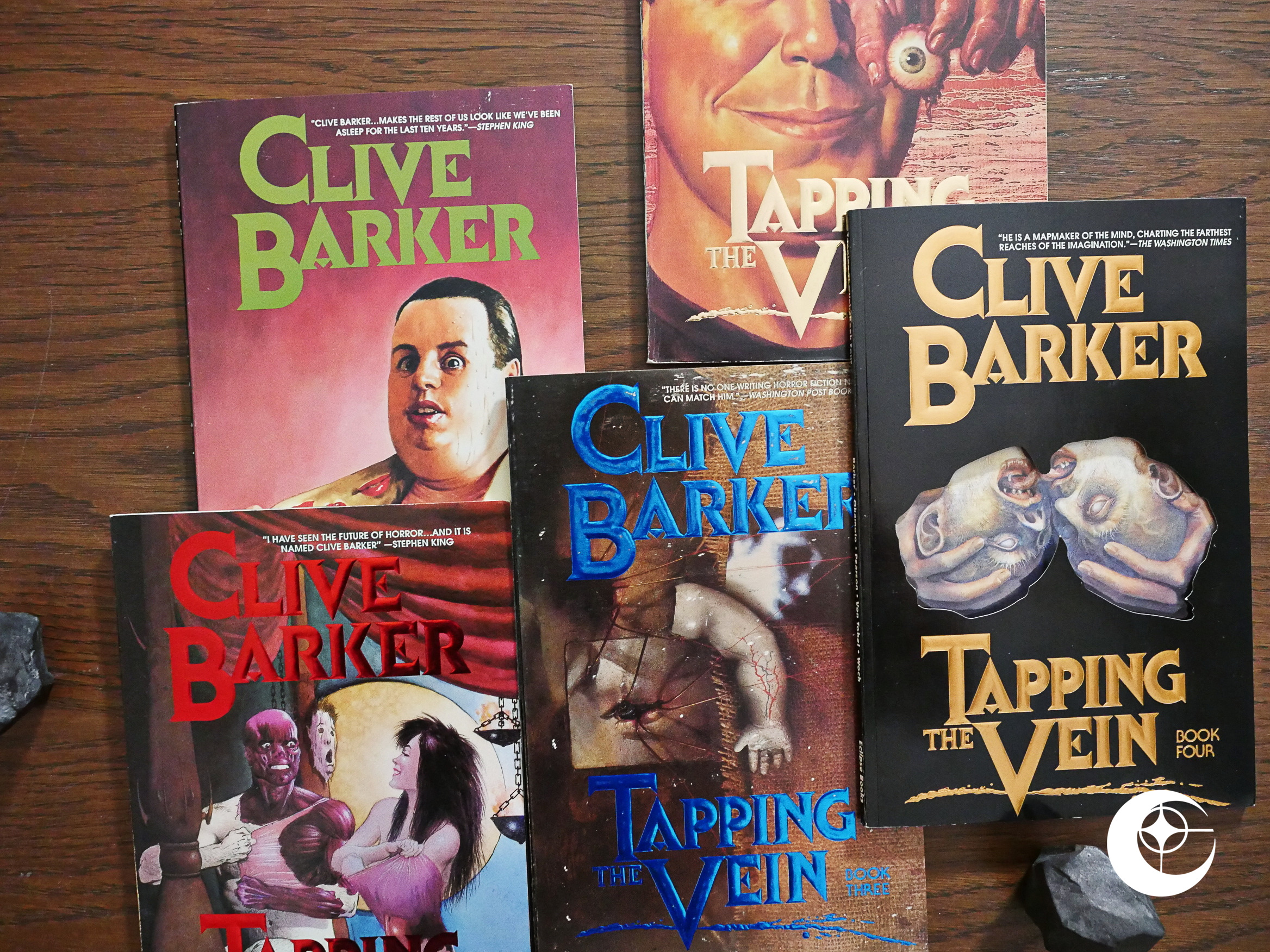

Fly in My Eye (1988) Tapping the Vein (1989) #1-5

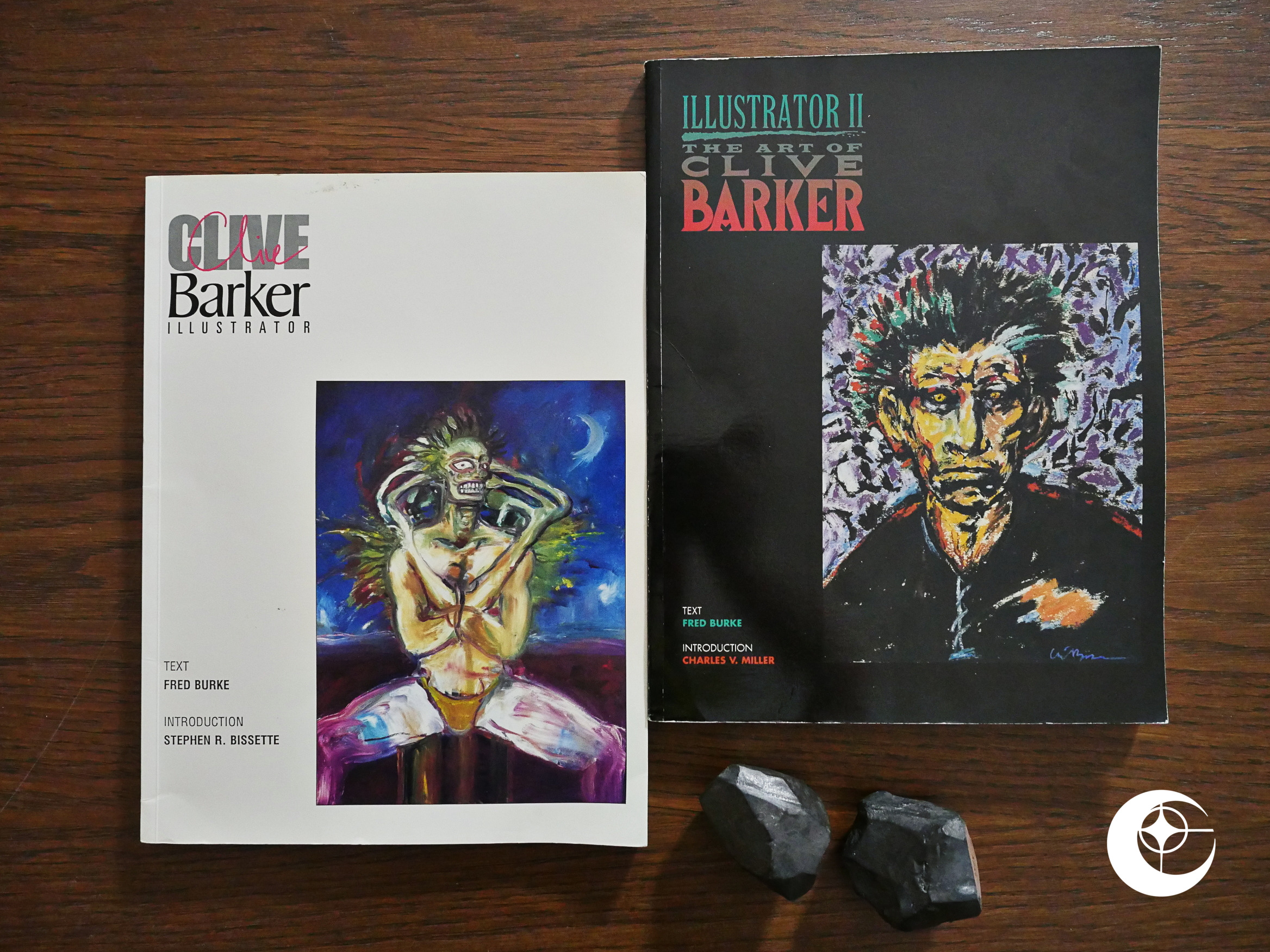

Tapping the Vein (1989) #1-5 Clive Barker Illustrator (1990)

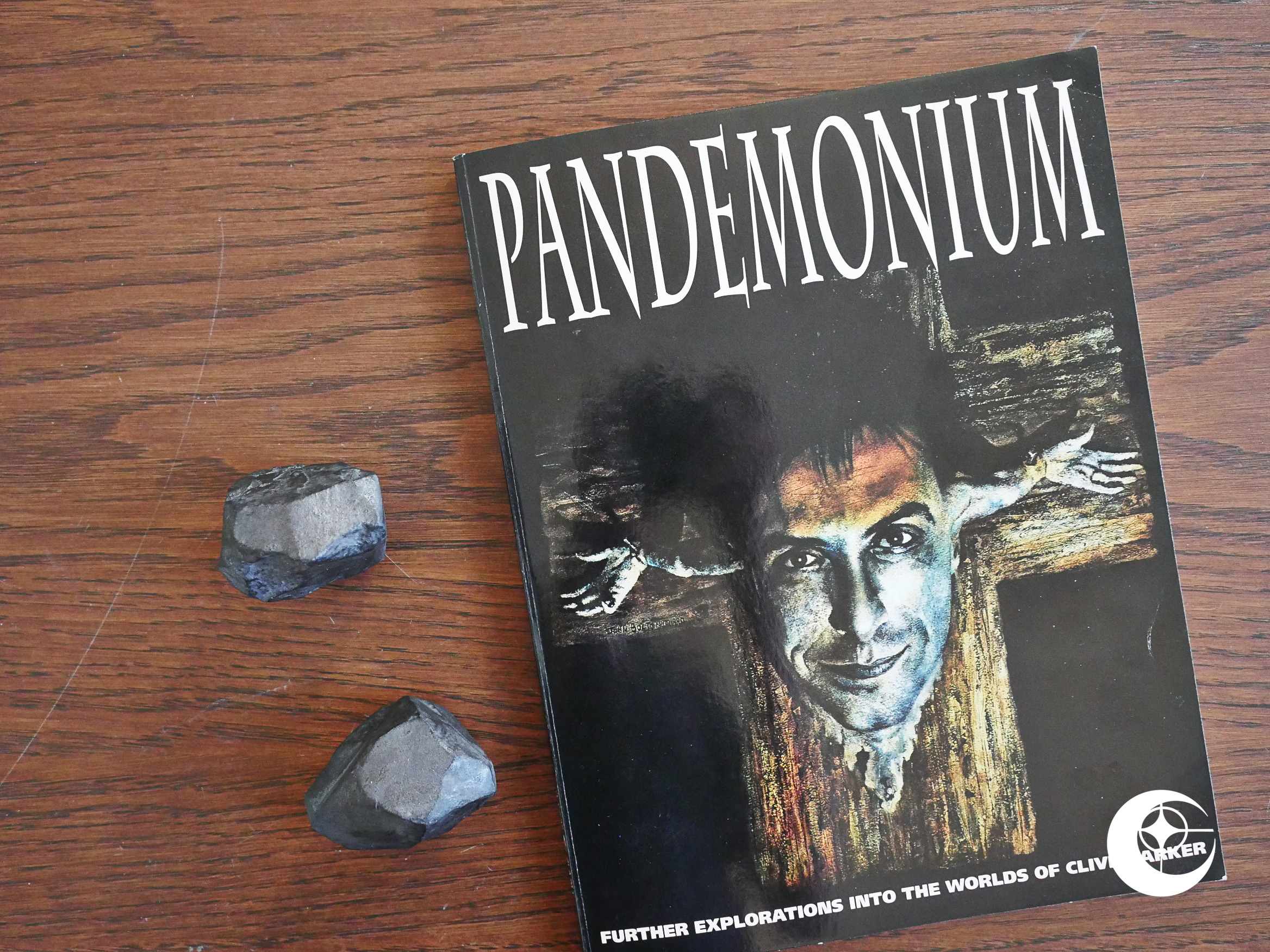

Clive Barker Illustrator (1990) Pandemonium (1991)

Pandemonium (1991)

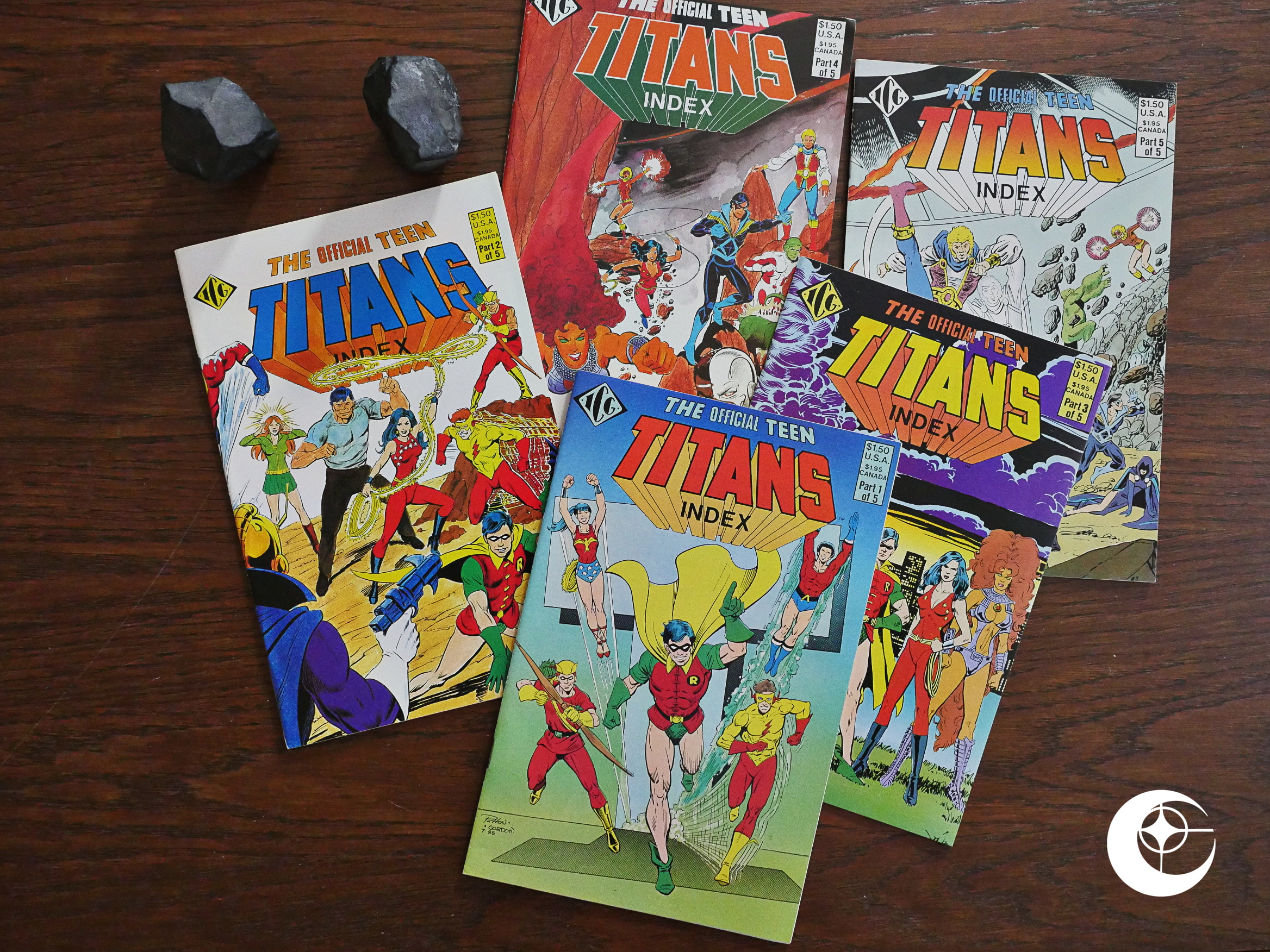

The Official Teen Titans Index (1985) #1-5

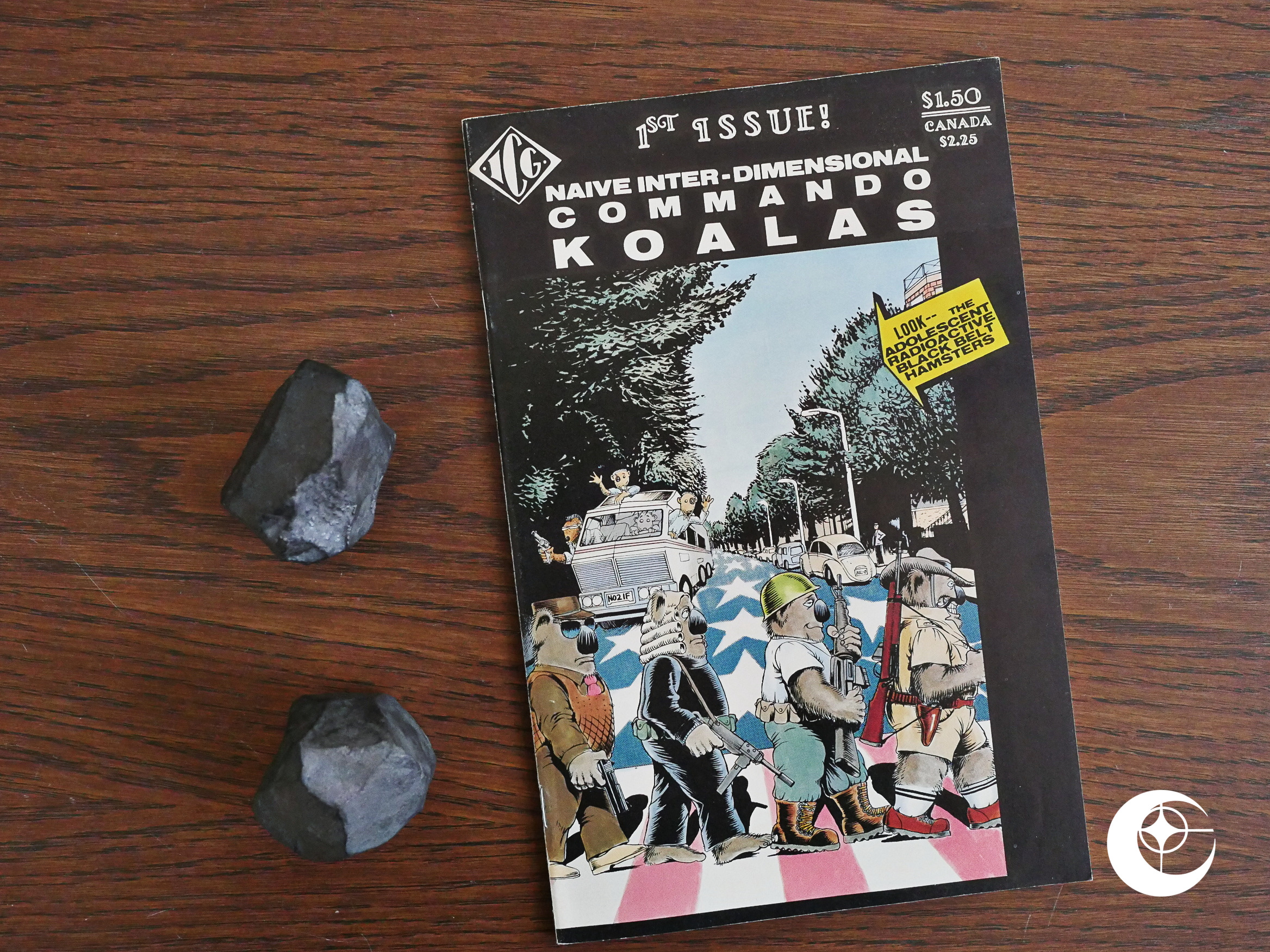

The Official Teen Titans Index (1985) #1-5 Naive Inter-Dimensional Commando Koalas (1986) #1

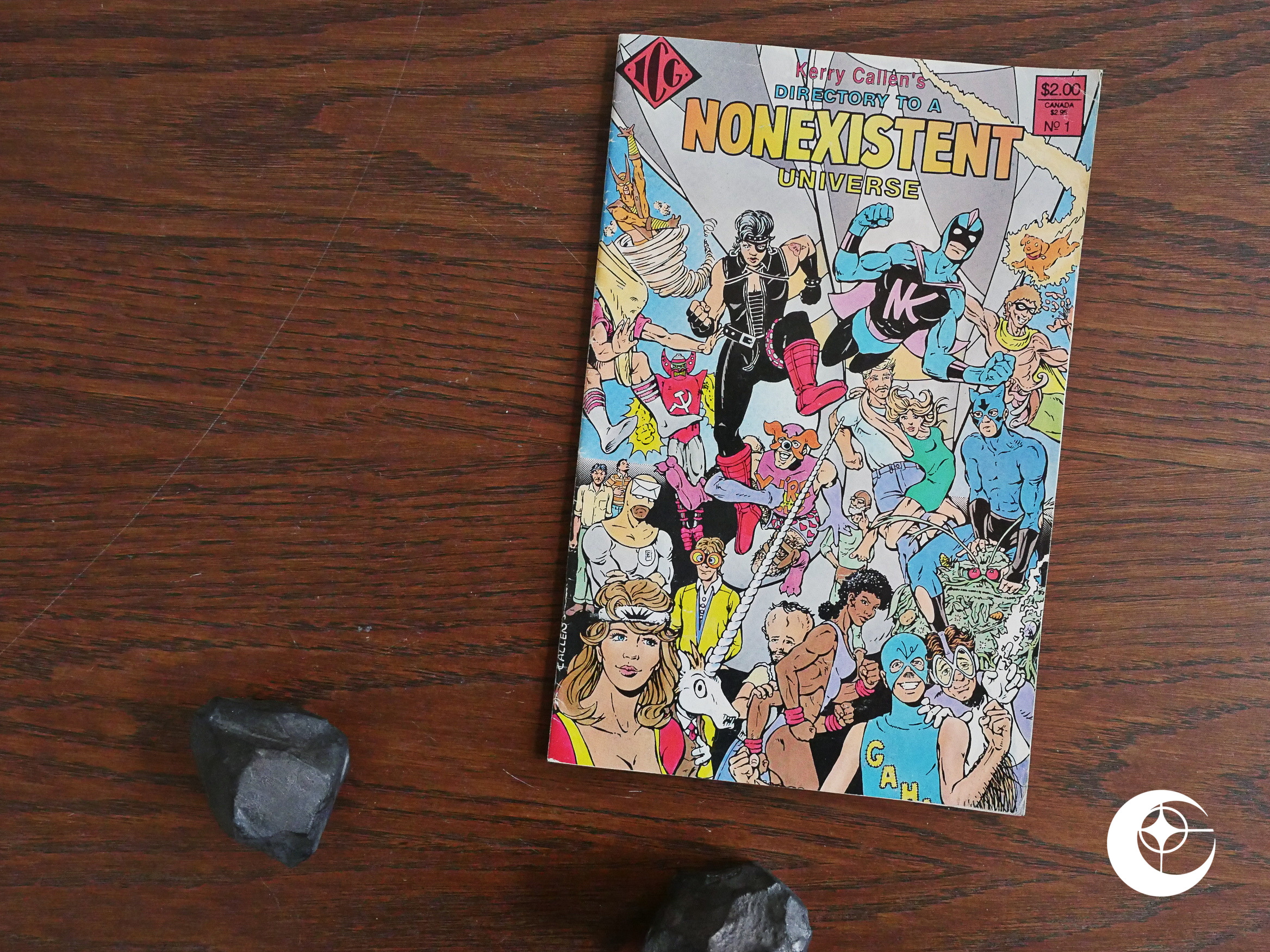

Naive Inter-Dimensional Commando Koalas (1986) #1 Directory to a Non-Existent Universe (1987) #1

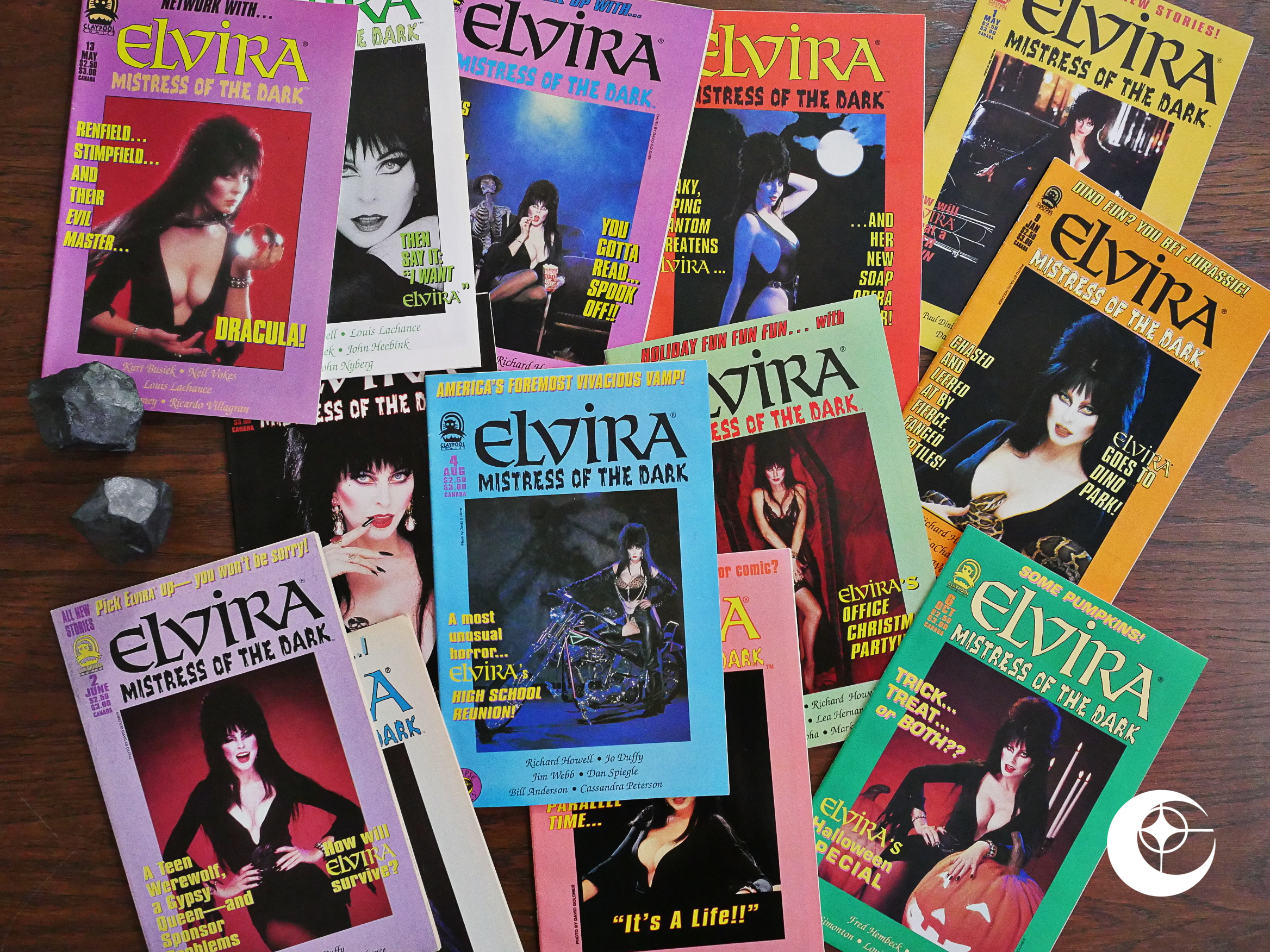

Directory to a Non-Existent Universe (1987) #1 Elvira, Mistress of the Dark (1993) #1-11

Elvira, Mistress of the Dark (1993) #1-11 Phantom of Fear City (1993) #1-6

Phantom of Fear City (1993) #1-6 Soulsearchers and Company (1993) #1-6

Soulsearchers and Company (1993) #1-6 Deadbeats (1993) #1-6

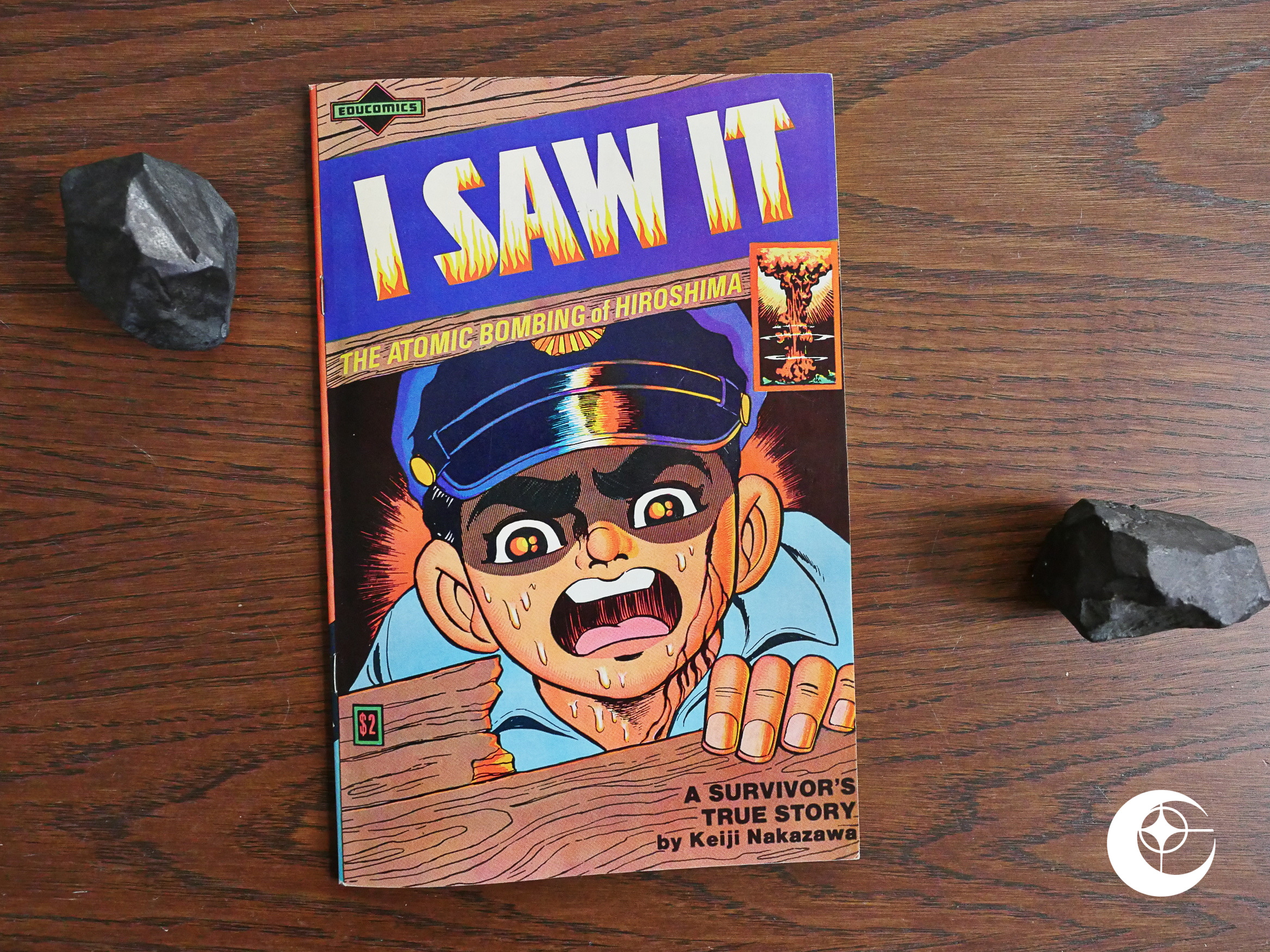

Deadbeats (1993) #1-6 I Saw It (1982)†

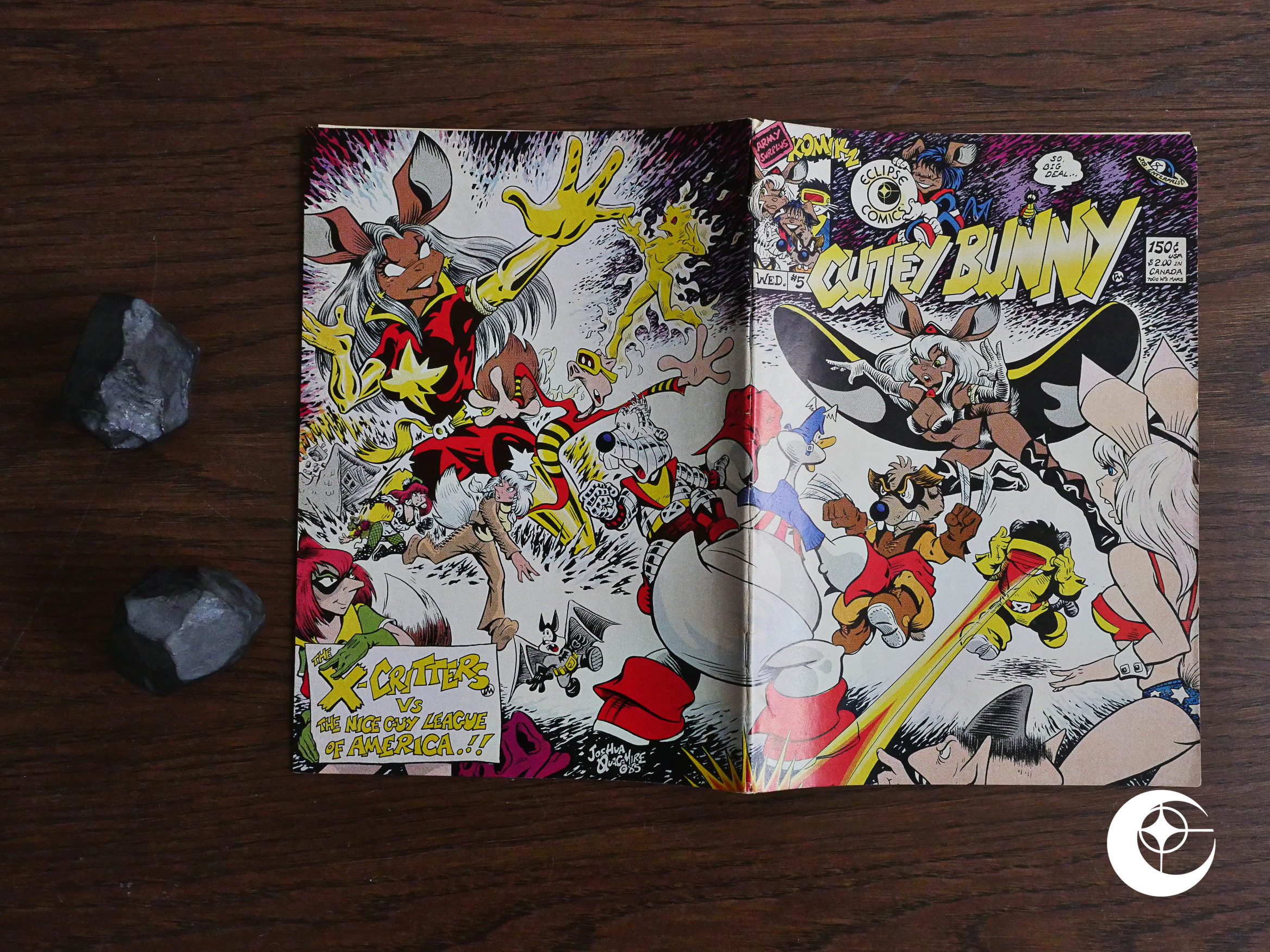

I Saw It (1982)† Army Surplus Komikz Featuring: Cutey Bunny (1985) #5*

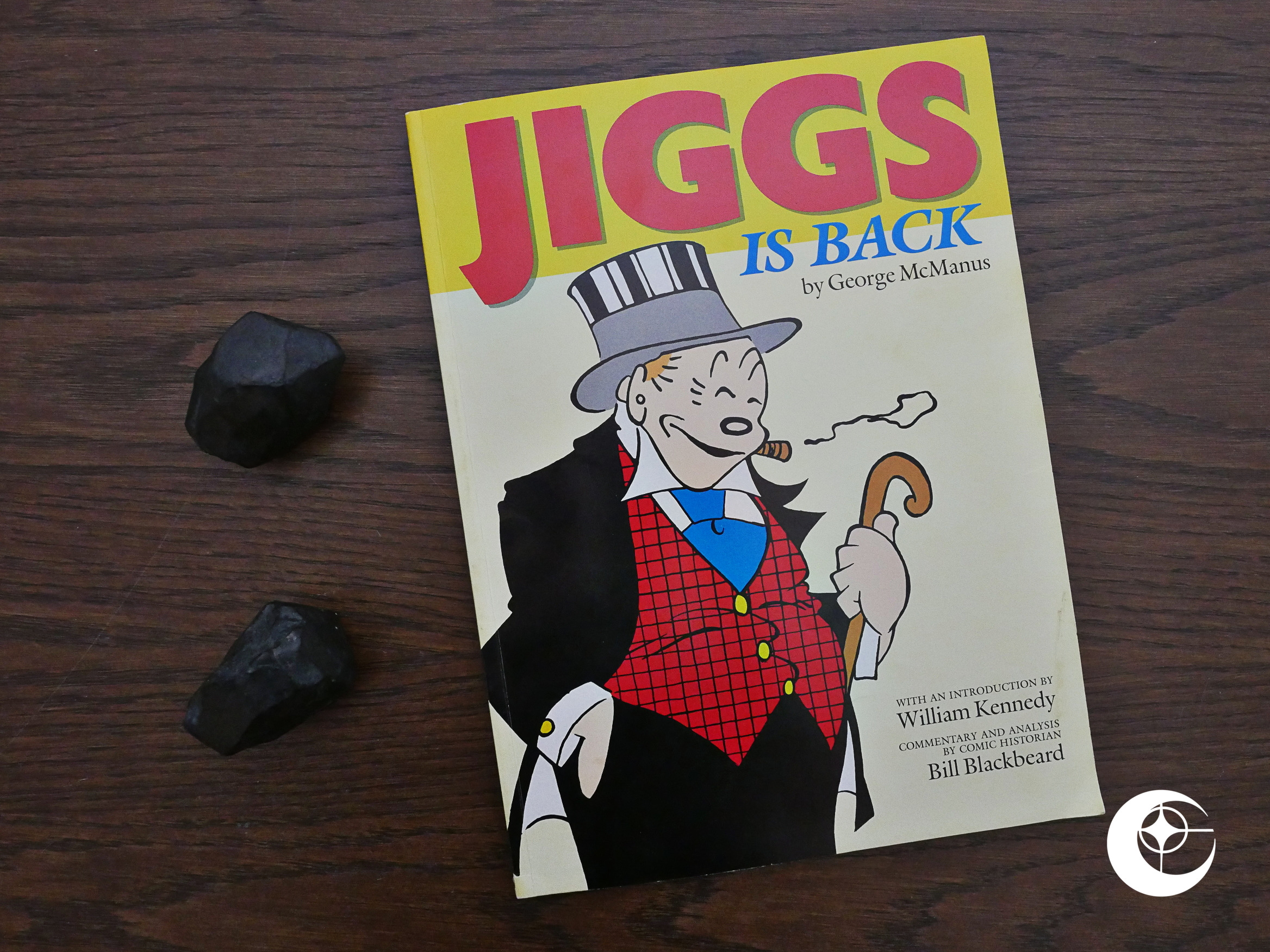

Army Surplus Komikz Featuring: Cutey Bunny (1985) #5* Jiggs is Back (1986)*

Jiggs is Back (1986)* Spaced (1986) #10-13*

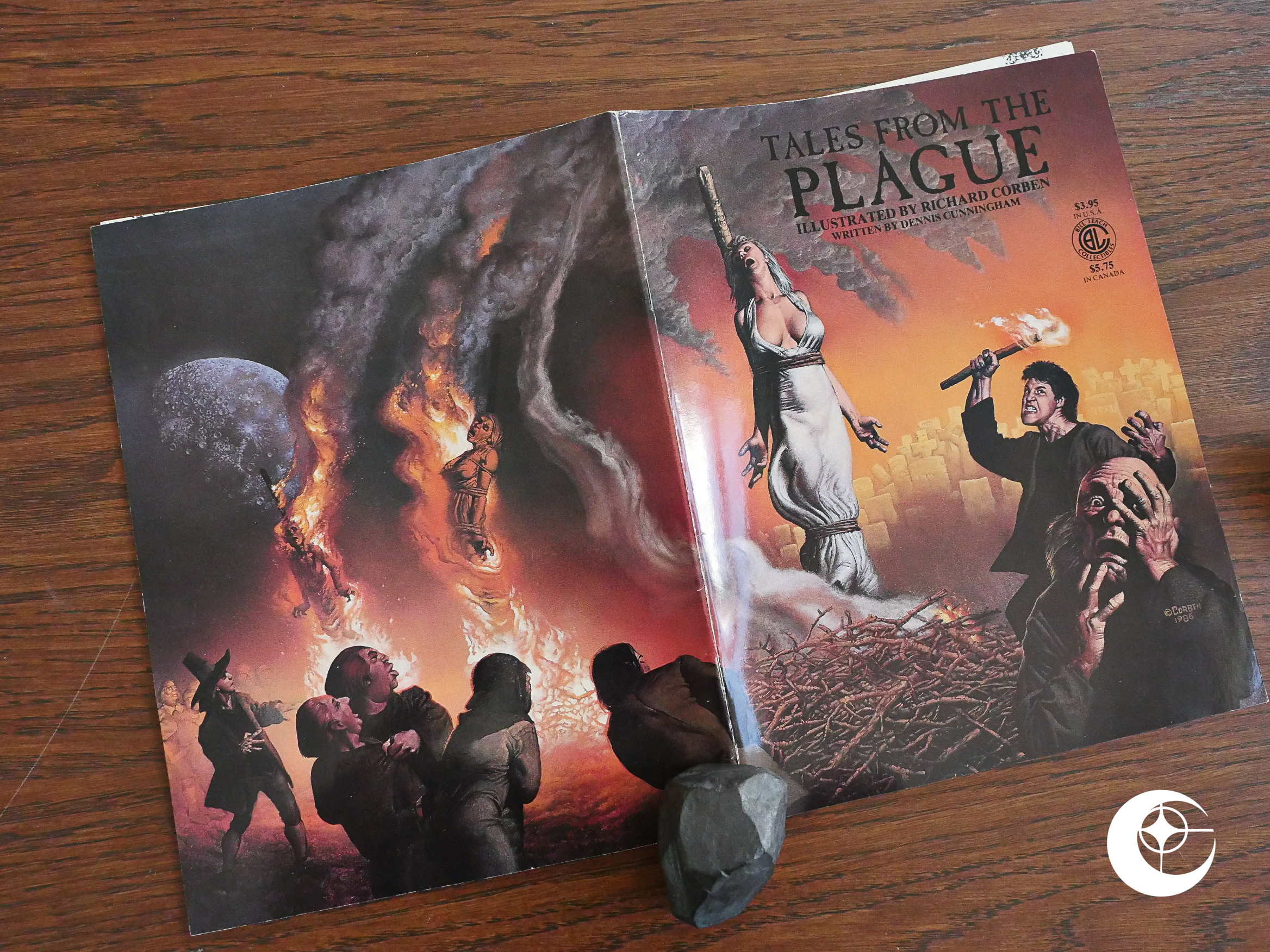

Spaced (1986) #10-13* Tales

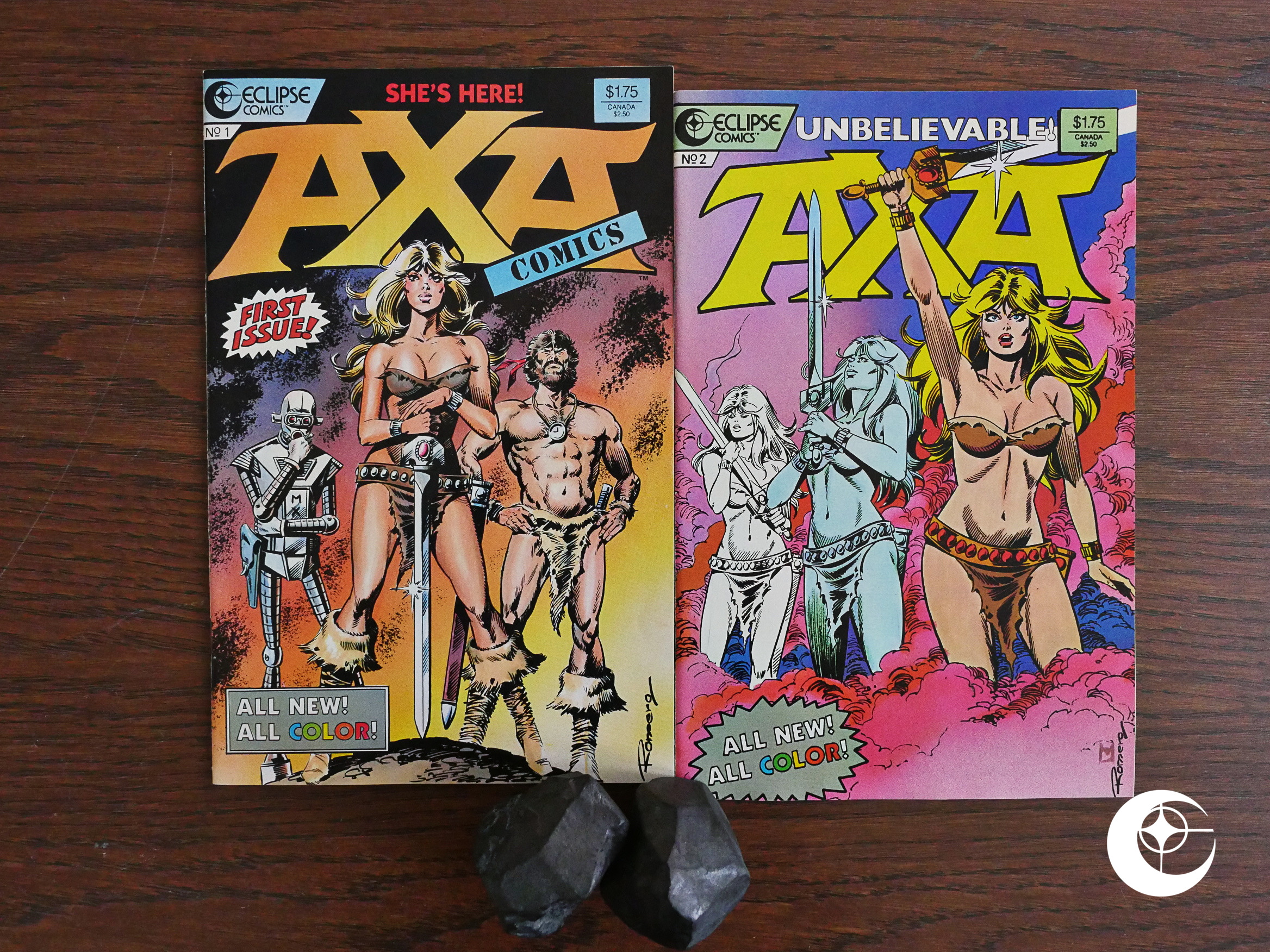

Tales Axa (1987) #1-2*

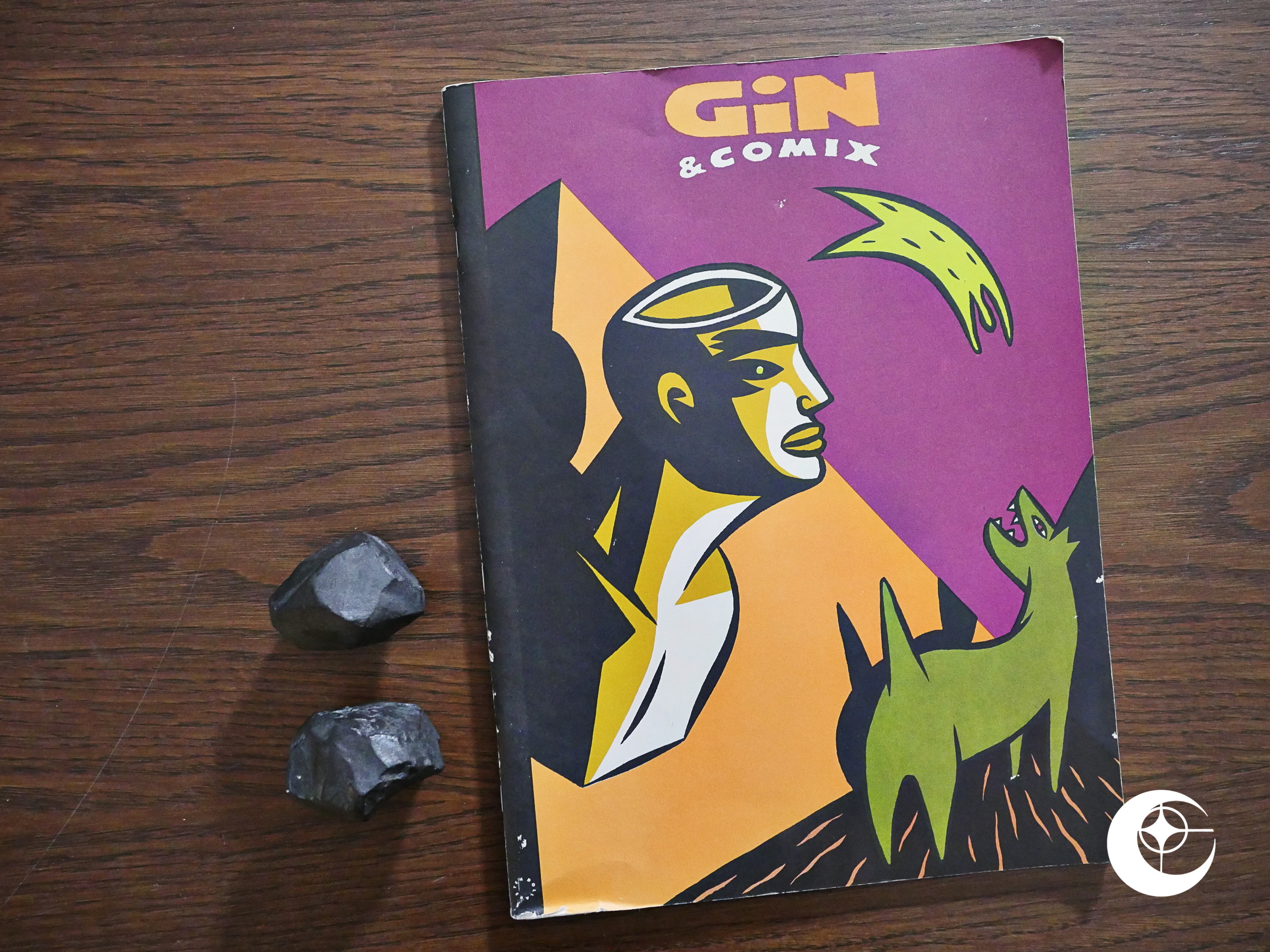

Axa (1987) #1-2* Gin

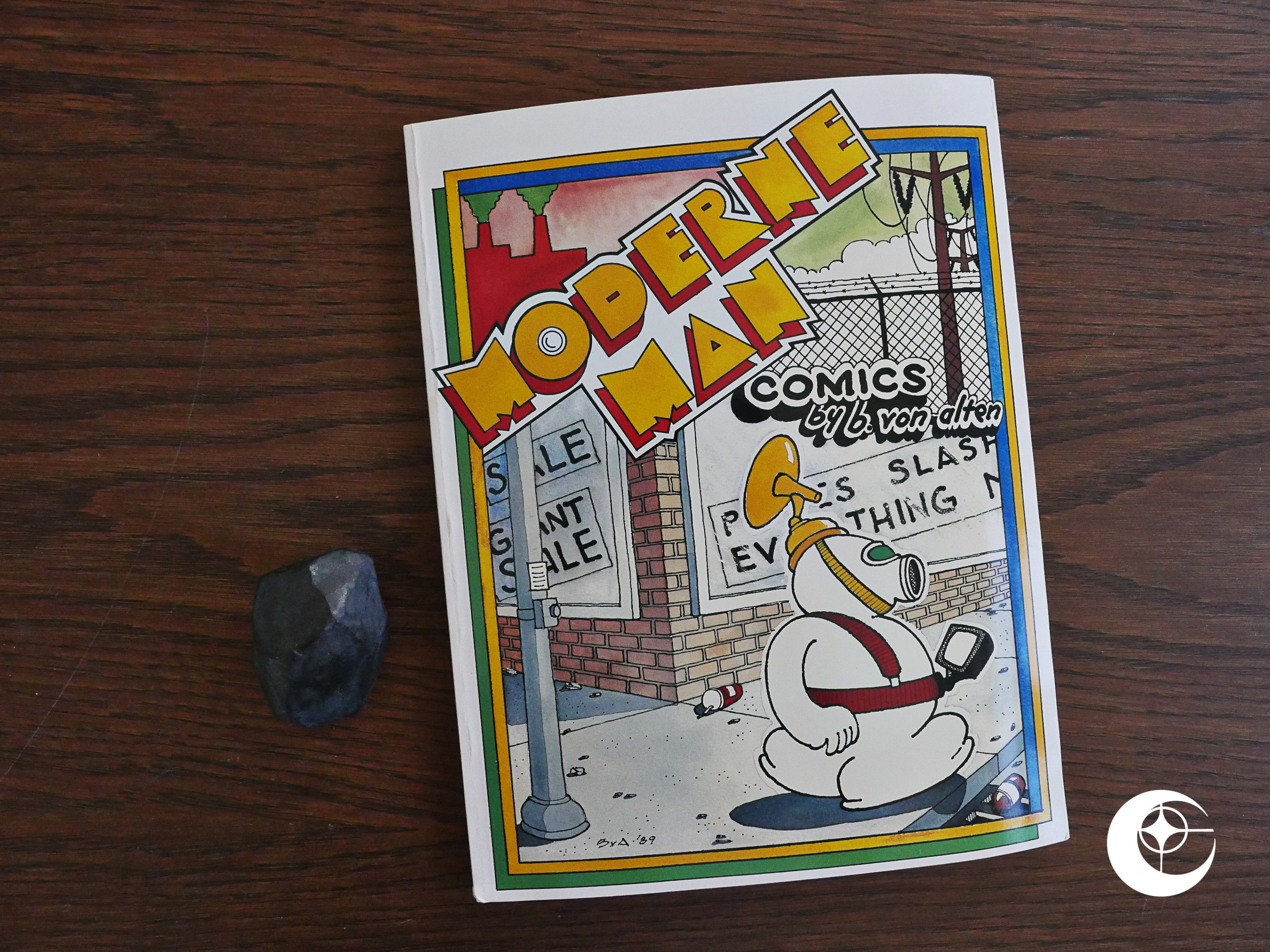

Gin Moderne Man Comics (1990)‡

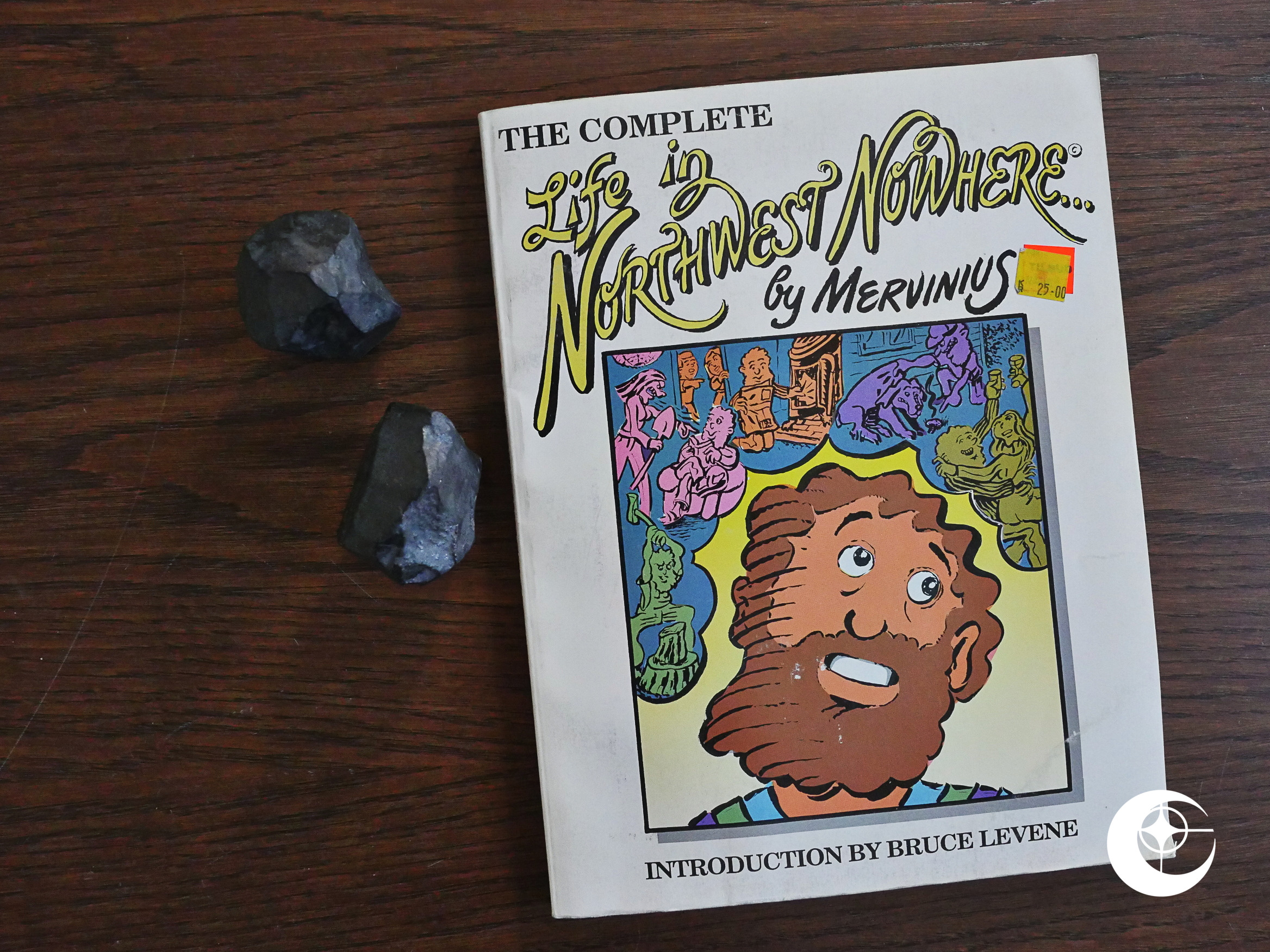

Moderne Man Comics (1990)‡ Life in Northwest Nowhere (1990)†

Life in Northwest Nowhere (1990)†

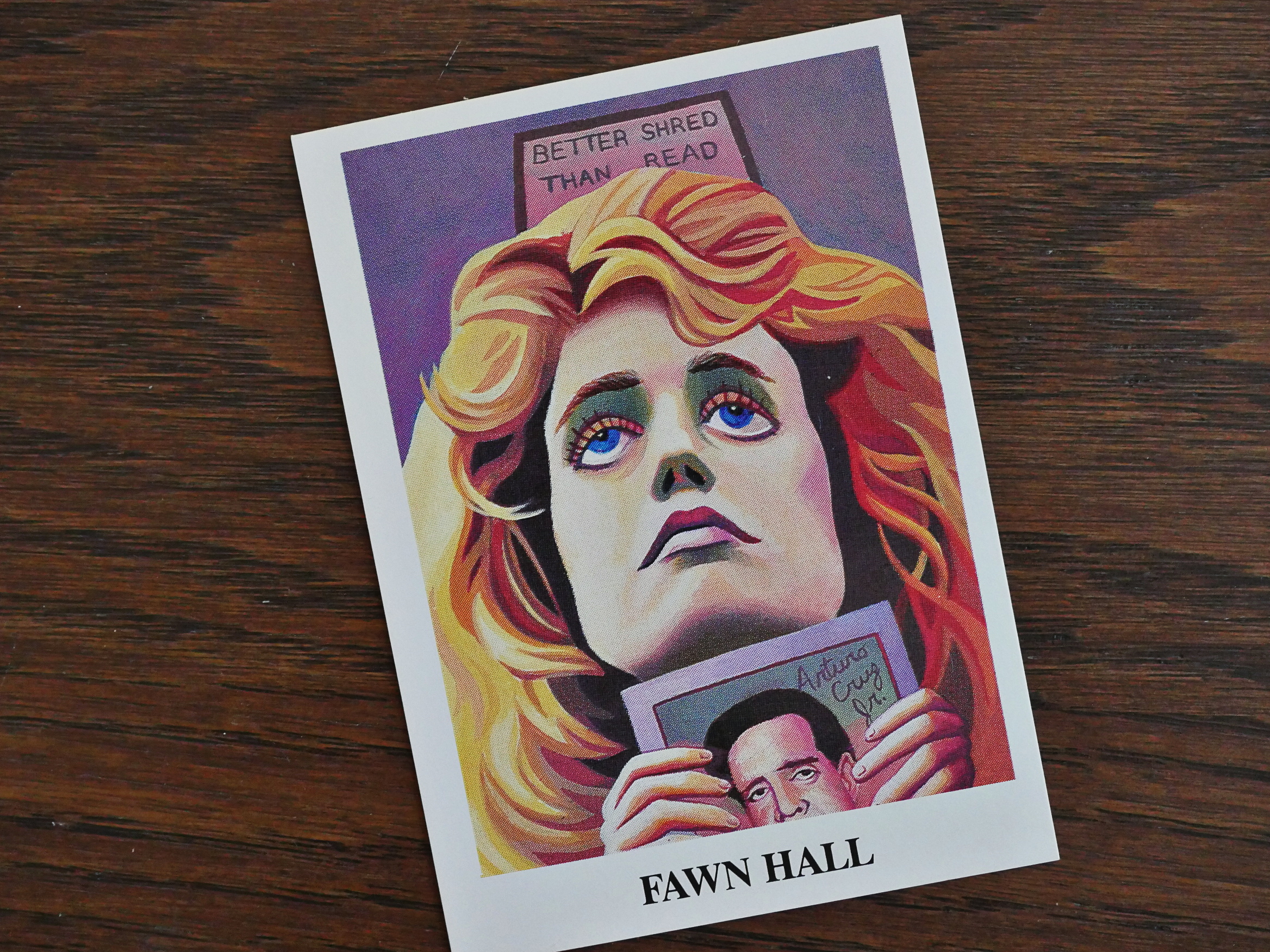

The Iran-Contra Scandal Trading Cards (1988)

The Iran-Contra Scandal Trading Cards (1988) Friendly Dictators Trading Cards (1989) #1

Friendly Dictators Trading Cards (1989) #1 Bush League Trading Cards (1990)

Bush League Trading Cards (1990) Rock Bottom Trading Cards (1990)

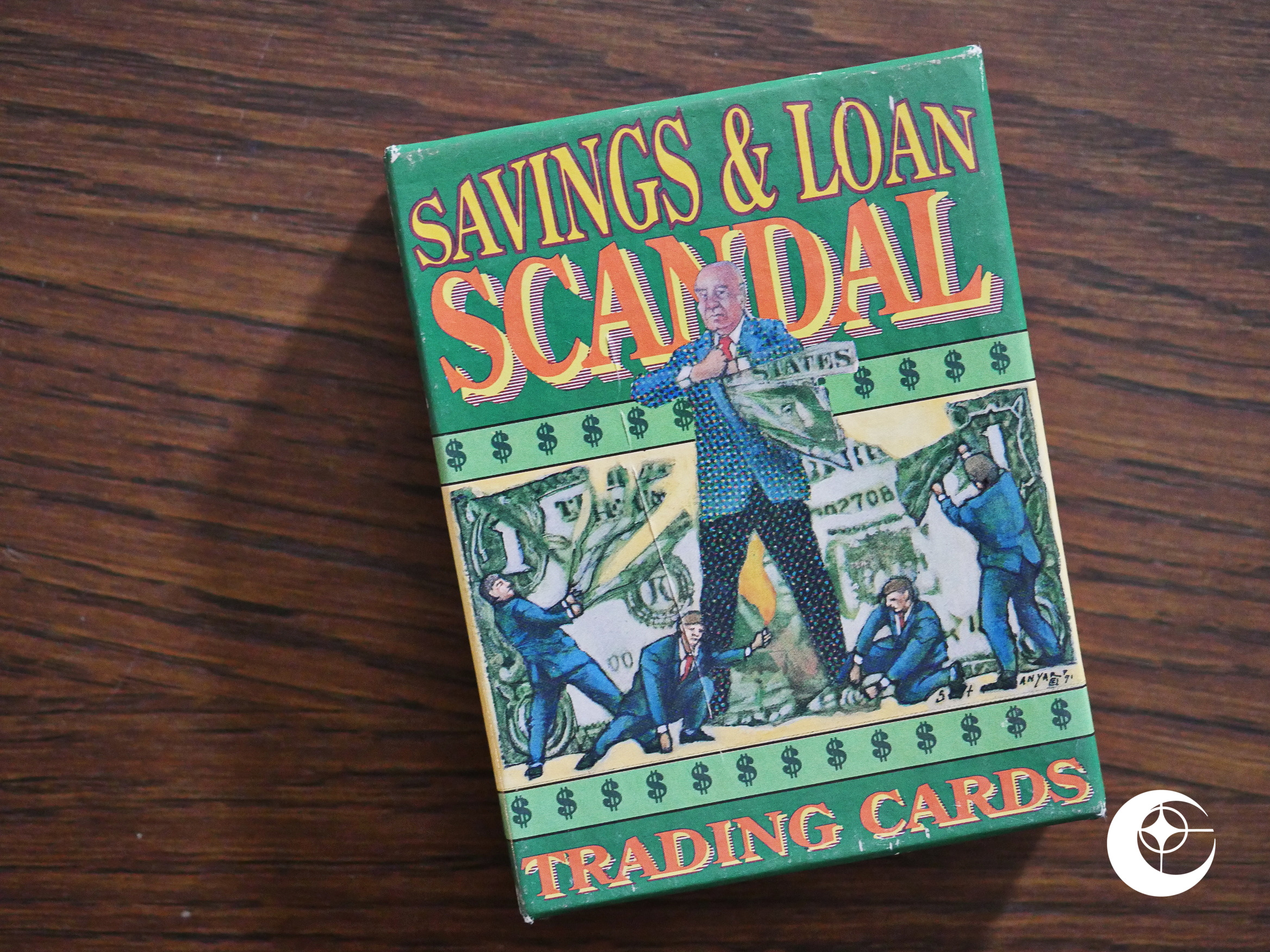

Rock Bottom Trading Cards (1990) The Savings and Loans Scandal Trading Cards (1991)

The Savings and Loans Scandal Trading Cards (1991) Famous Comic Book Creators Trading Cards (1992)

Famous Comic Book Creators Trading Cards (1992) Crime and Punishment Trading Cards (1992)

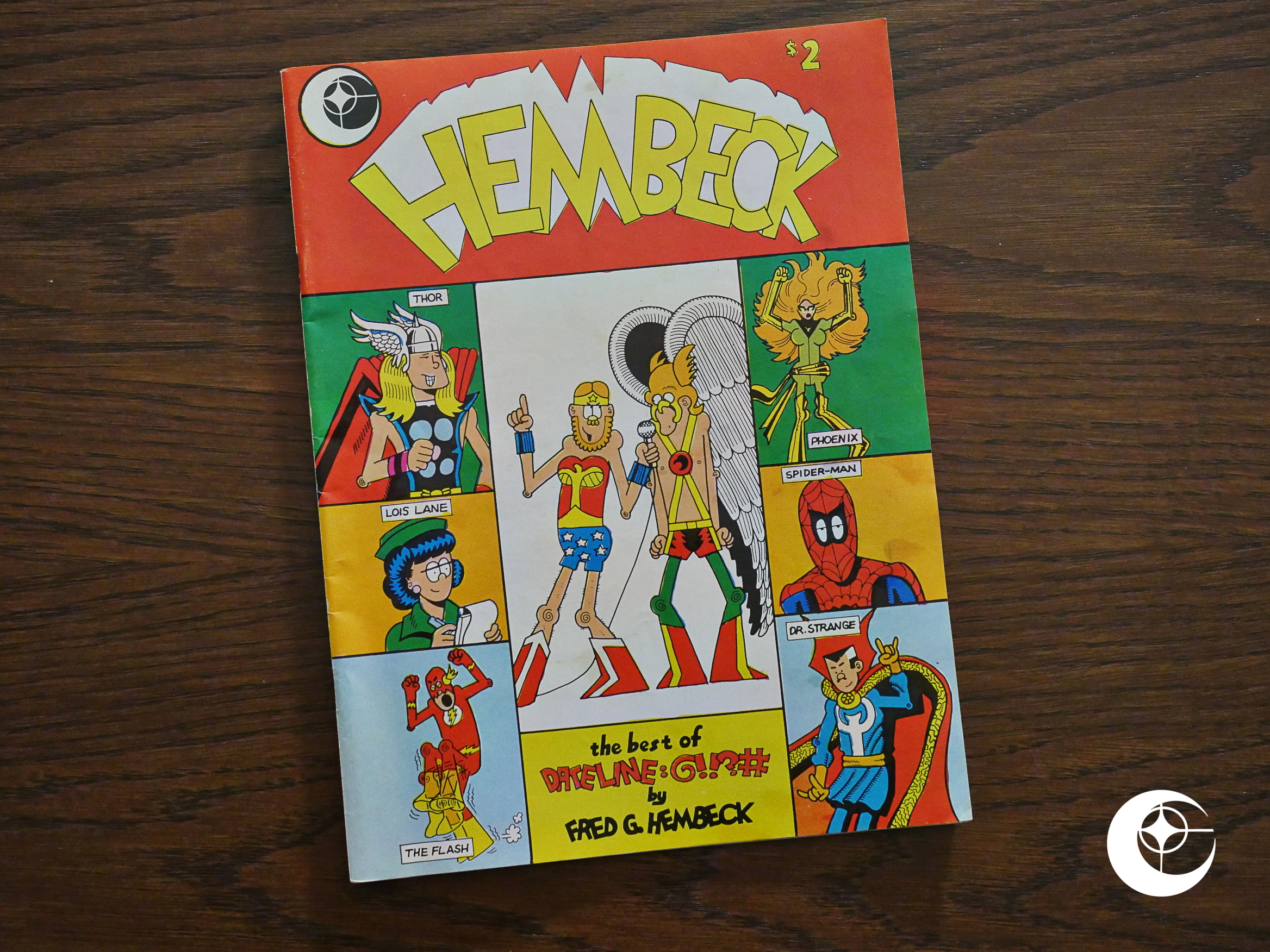

Crime and Punishment Trading Cards (1992) Hembeck: The Best of Dateline: @!!?# (1979) #1

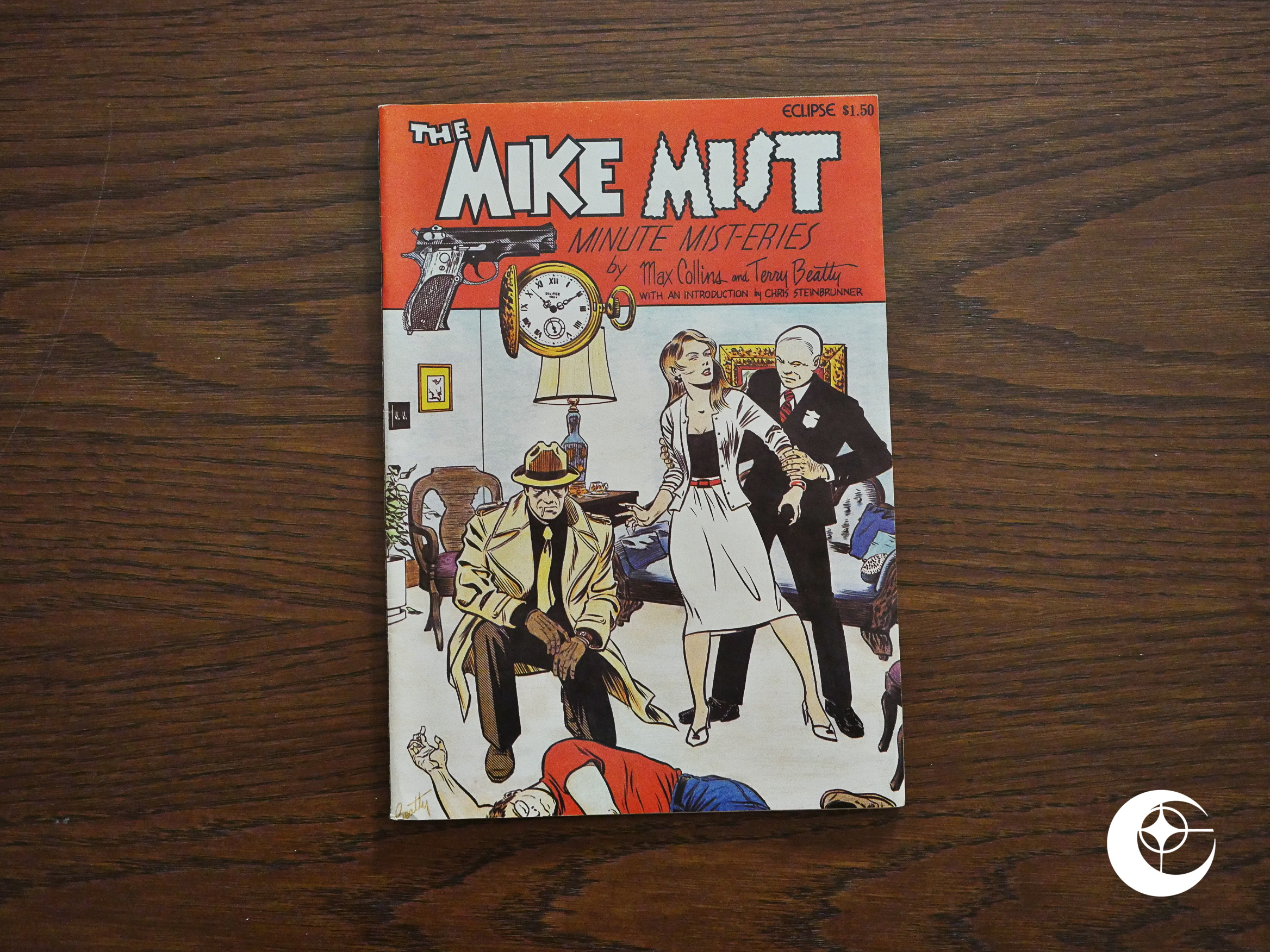

Hembeck: The Best of Dateline: @!!?# (1979) #1 The Mike Mist Minute Mist-Eries (1981) #1

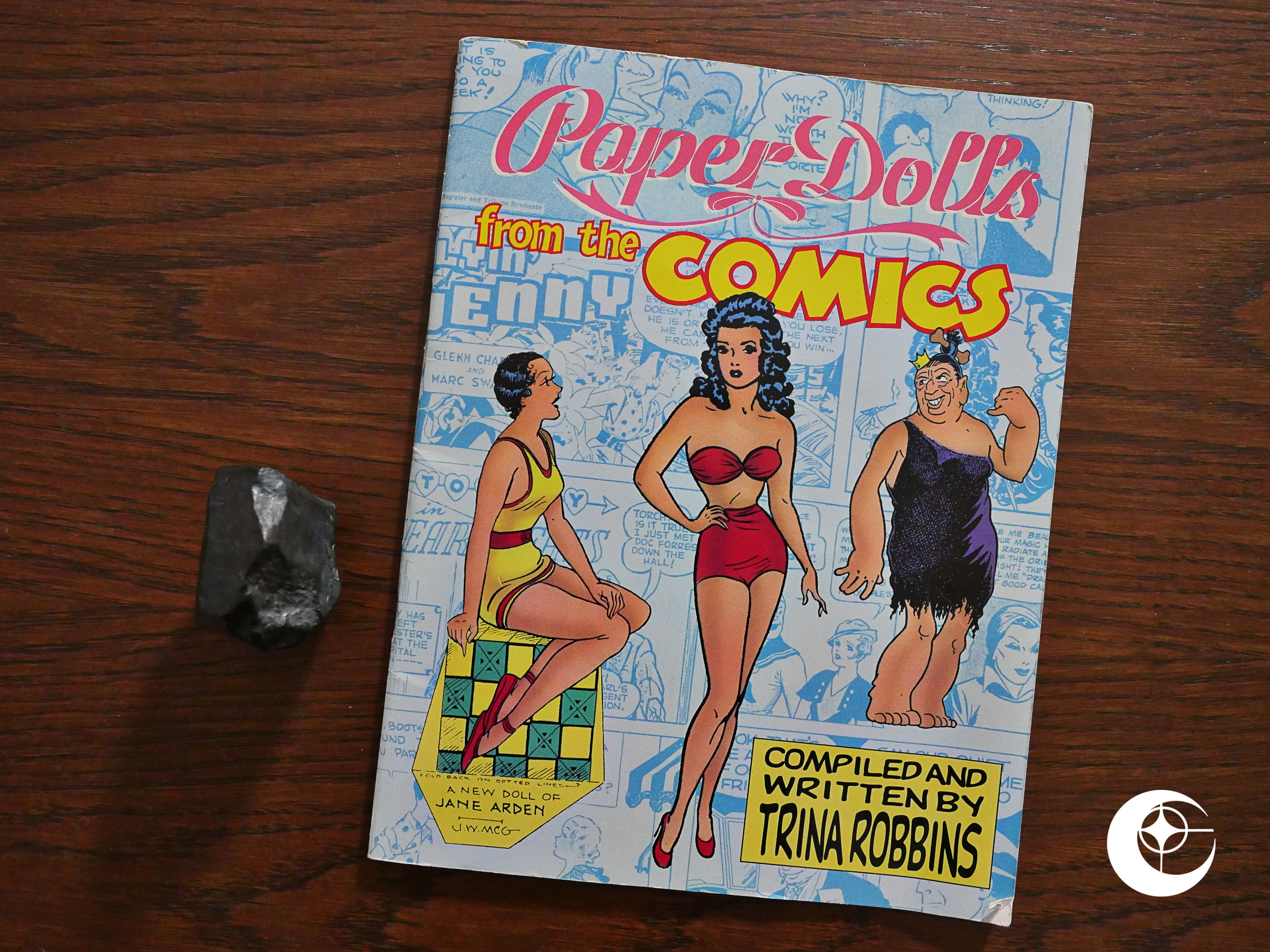

The Mike Mist Minute Mist-Eries (1981) #1 Paper Dolls from the Comics (1987)

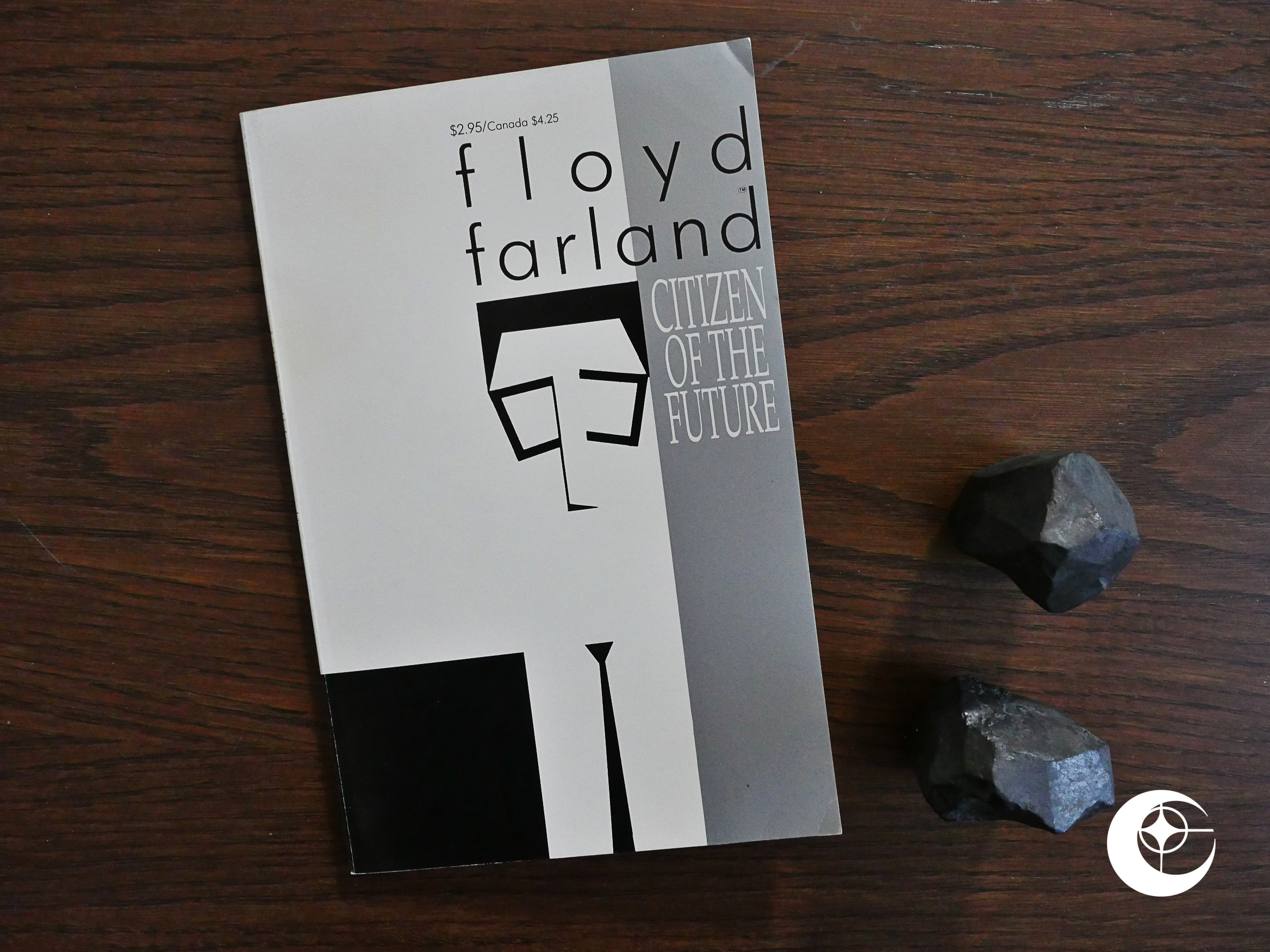

Paper Dolls from the Comics (1987) Floyd Farland – Citizen of the Future (1987)

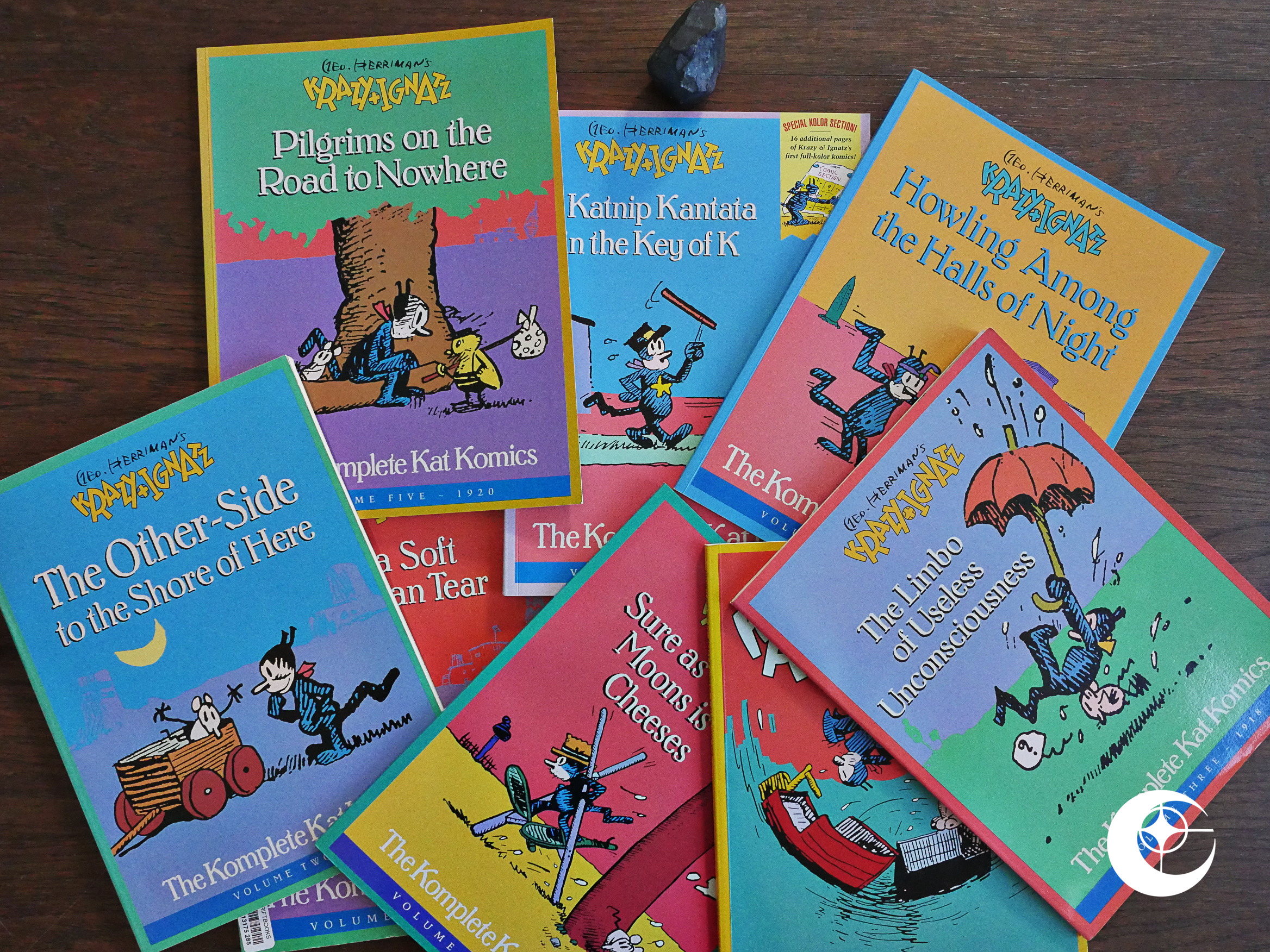

Floyd Farland – Citizen of the Future (1987) Krazy & Ignatz: The Komplete Kat Comics (1988) #1-9

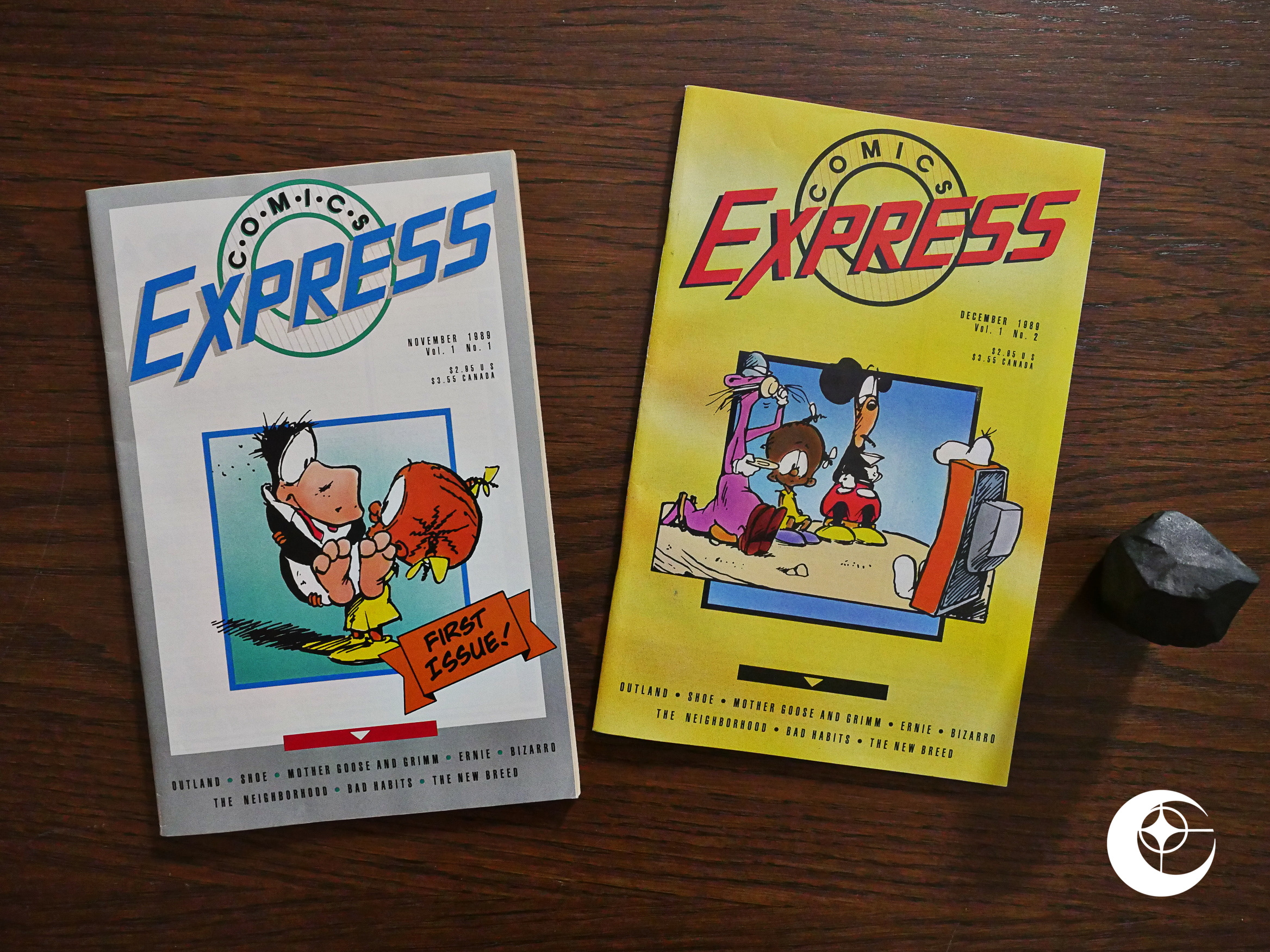

Krazy & Ignatz: The Komplete Kat Comics (1988) #1-9 Comics Express (1989) #1-2

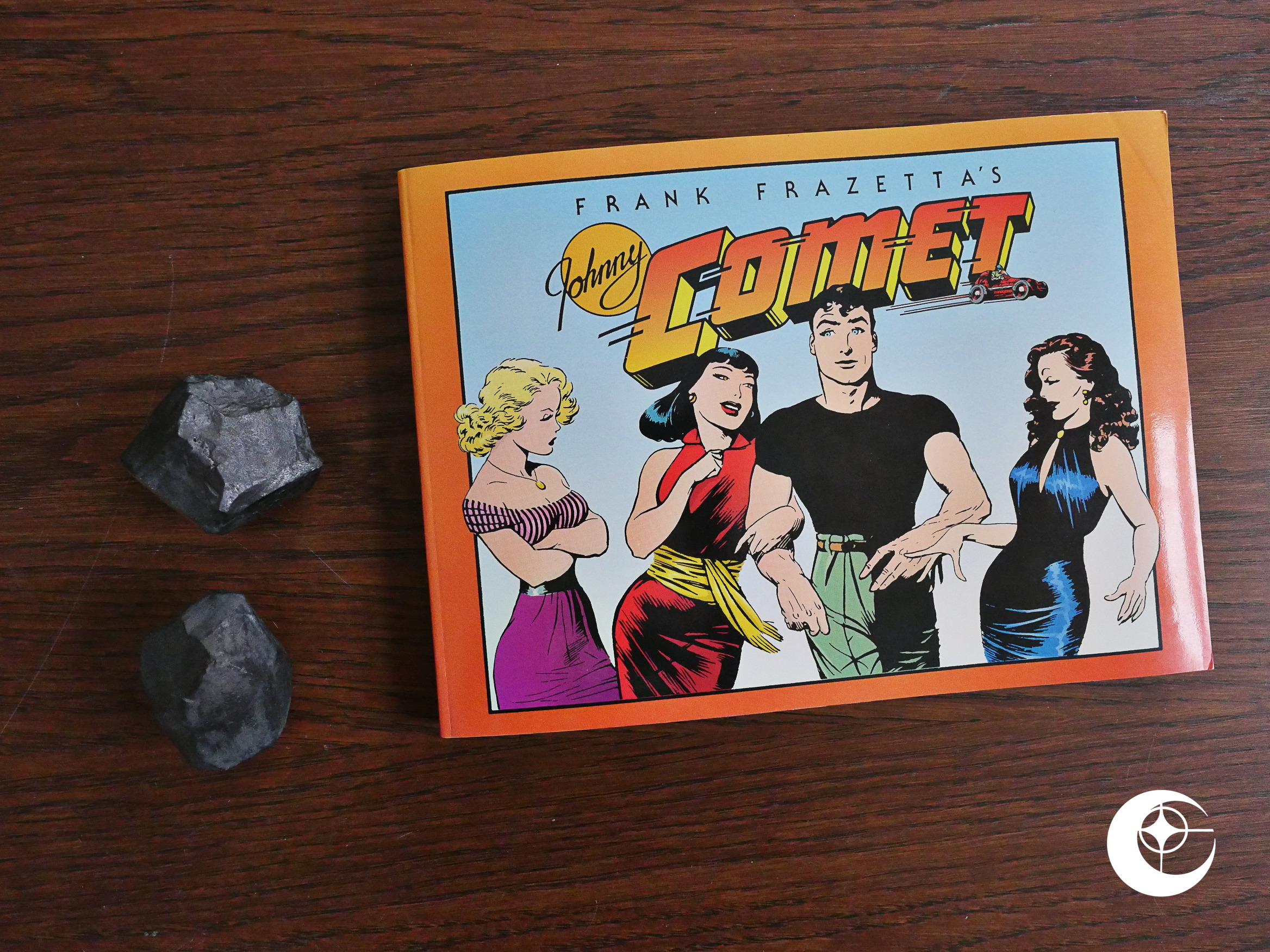

Comics Express (1989) #1-2 Johnny Comet (1991)

Johnny Comet (1991)