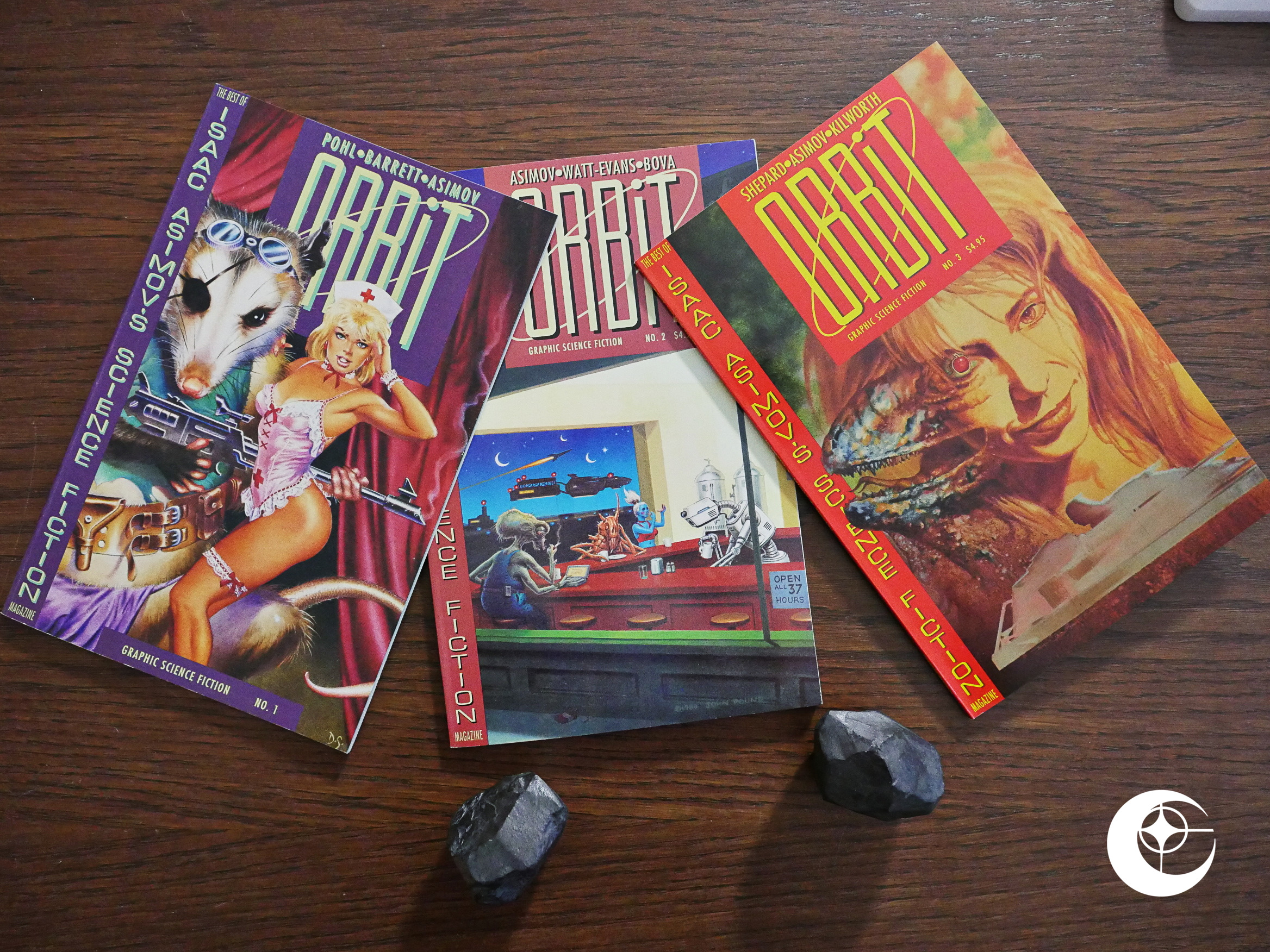

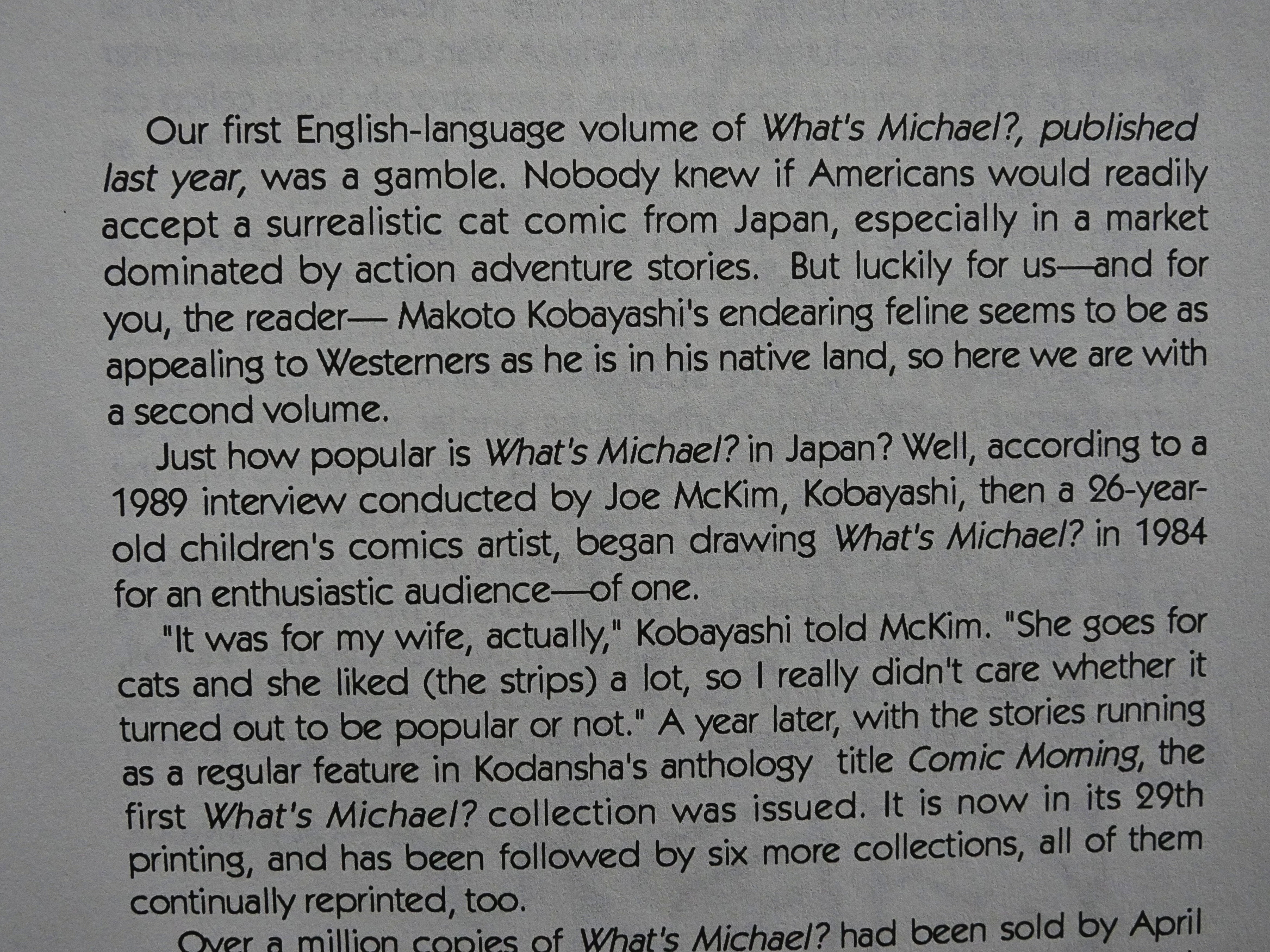

ORBiT (1990) #1-3 edited by Letitia Glozer.

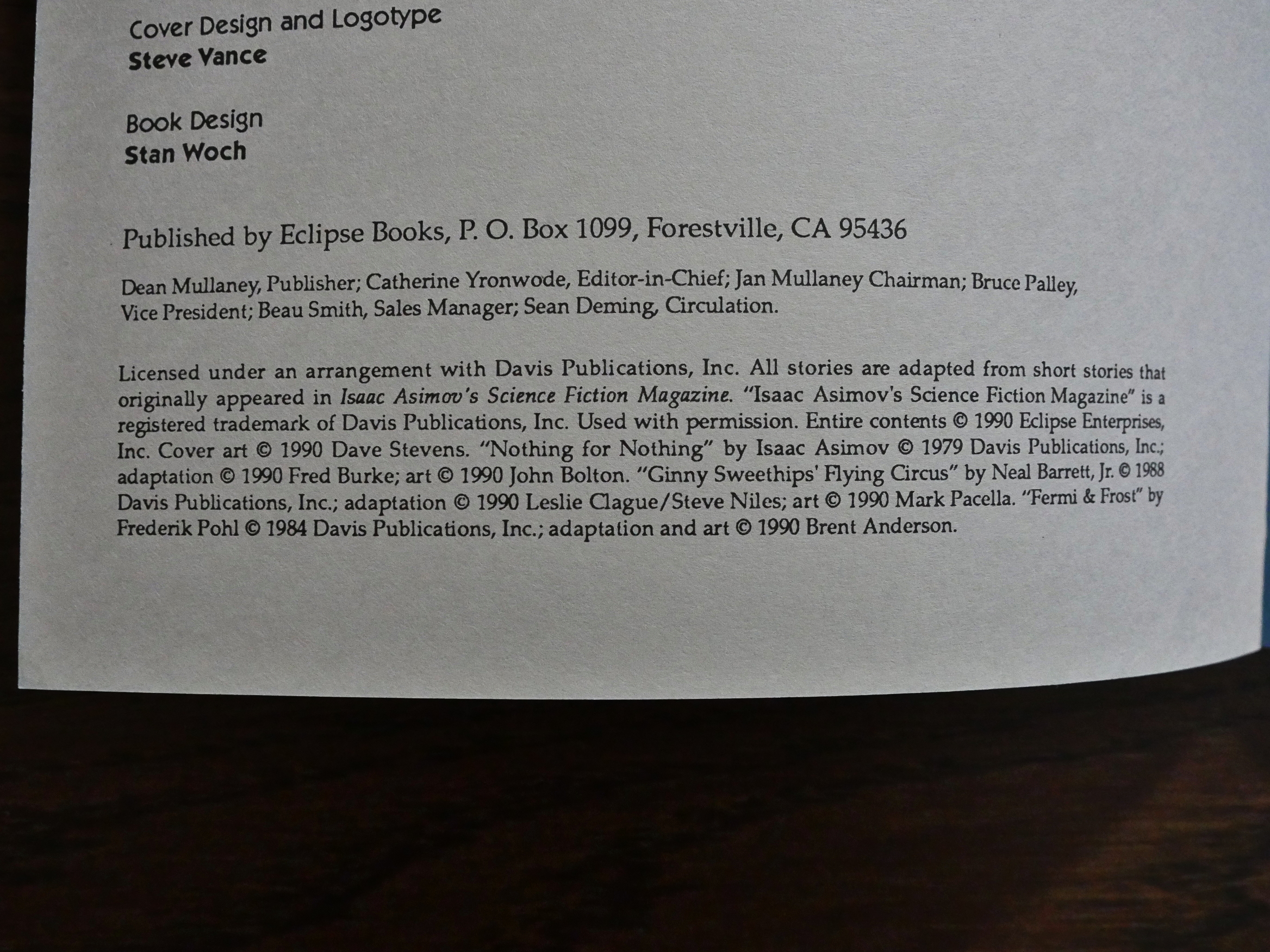

Eclipse had started doing adaptations of Clive Barker’s short stories some months earlier with Tapping the Vein, so perhaps it felt natural to branch out into science fiction short story adaptations, too.

So this is an adaptation of short stories from the Isaac Asimov magazine, which I’ve never seen. I’ve never read any of the science fiction magazines, even if I’m a huge sf geek. I’ve nothing but my own prejudice to go on, really, but I’ve always assumed that those mags were pretty staid and boring. I mean, I liked reading Asimov when I was, like, 12, but I went on to other authors.

Hey! Either Stan Woch or Steve Vance did the design on this extra-special Eclipse/Orbit logo. Heh.

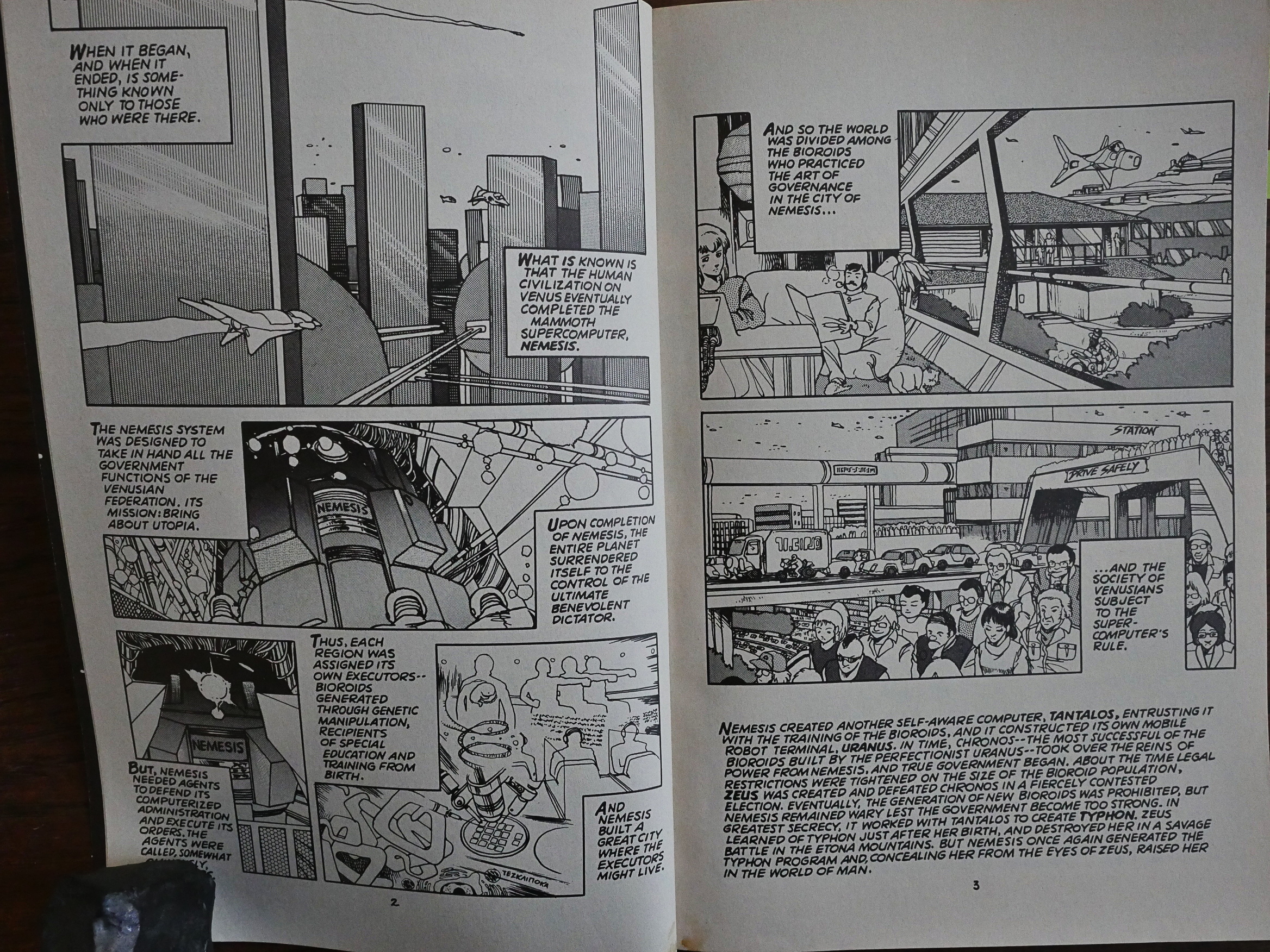

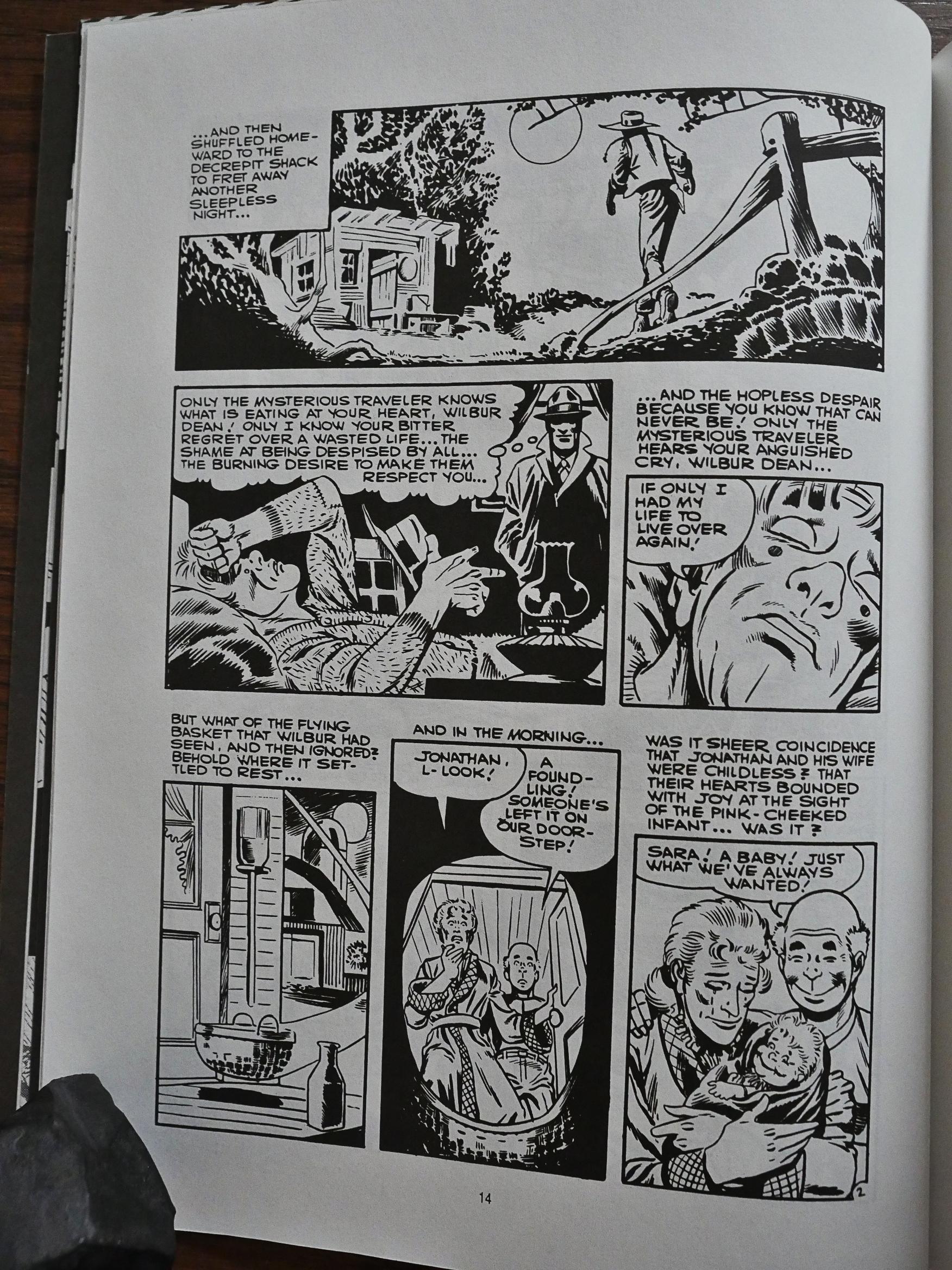

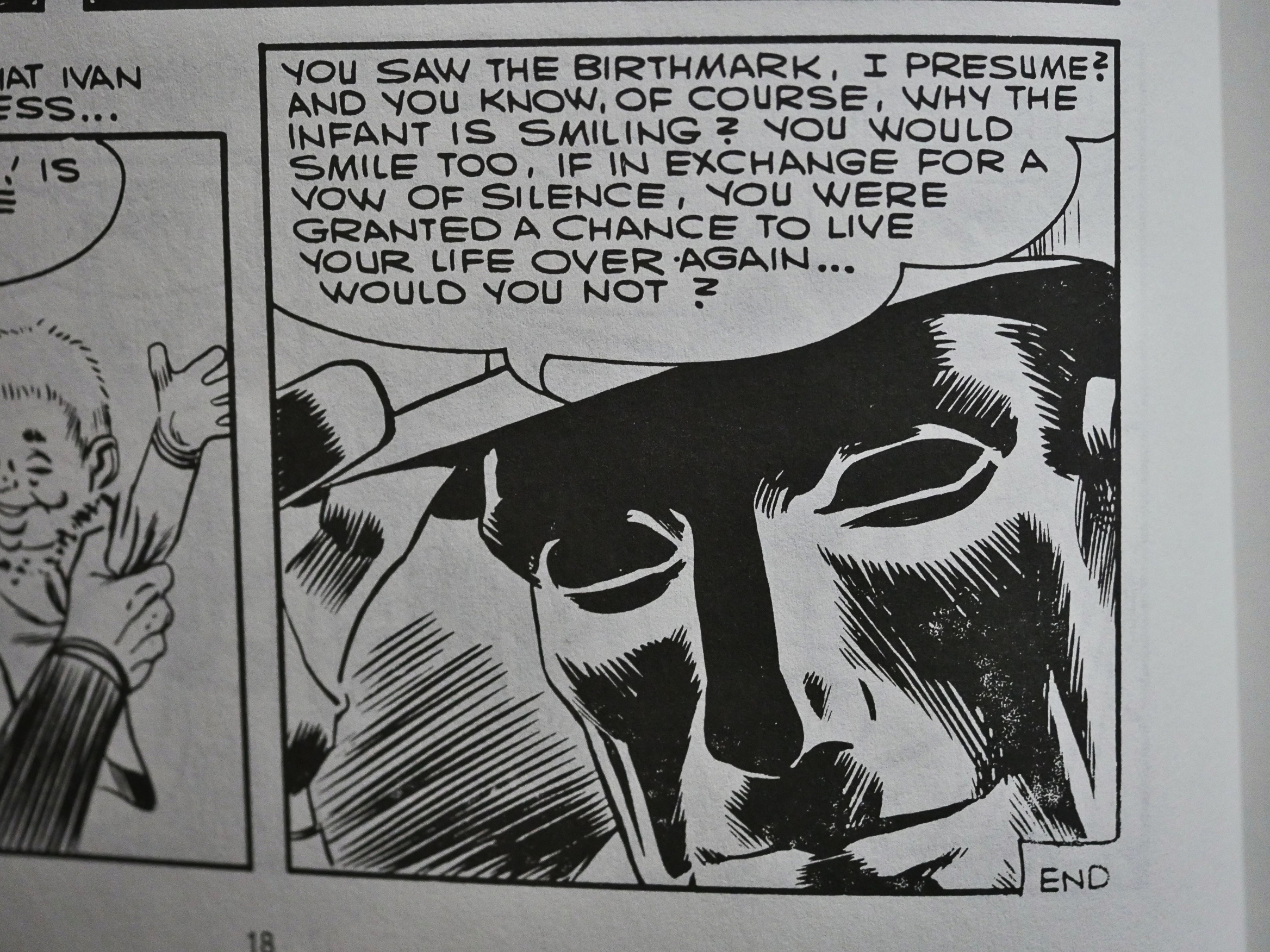

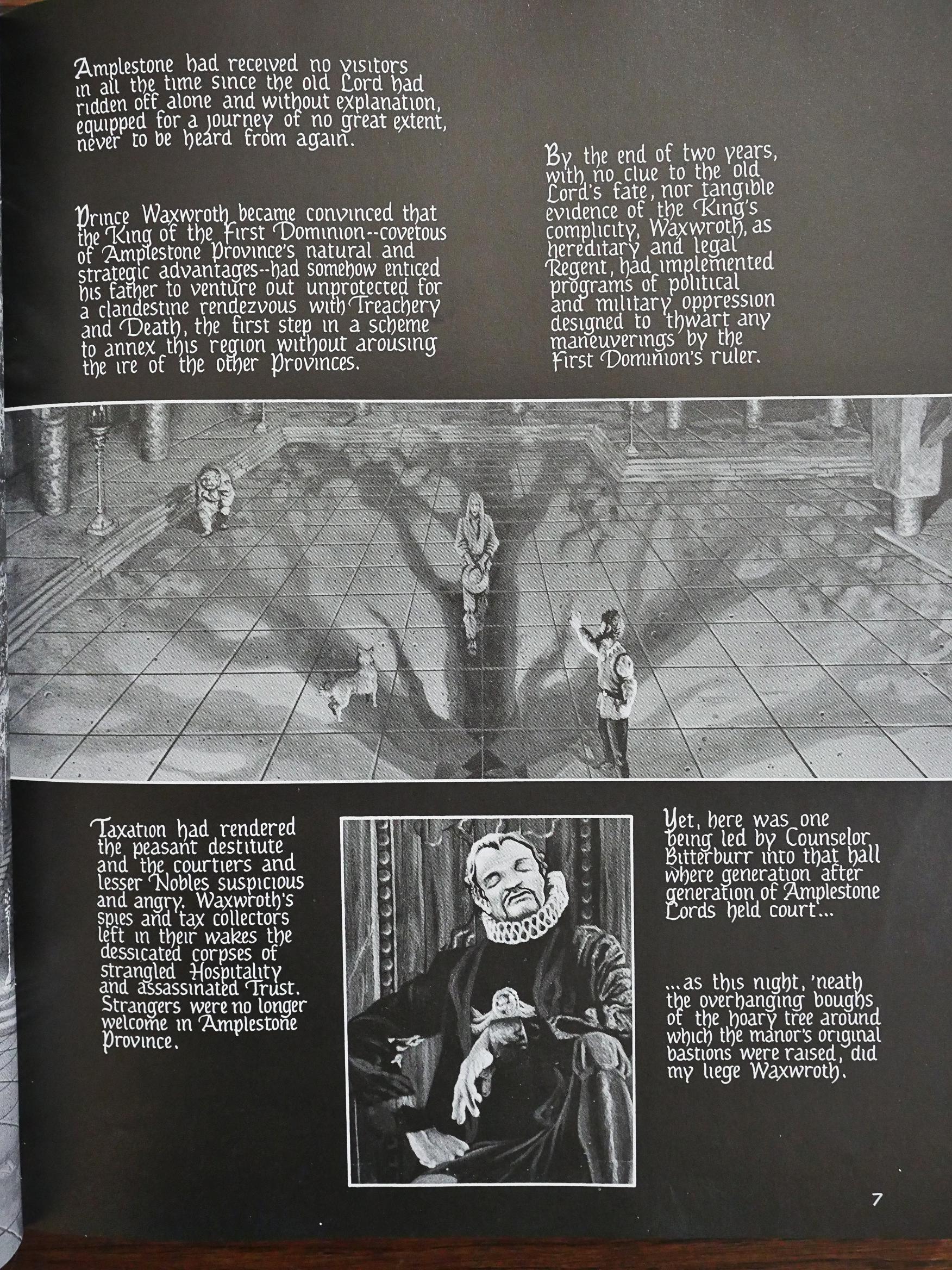

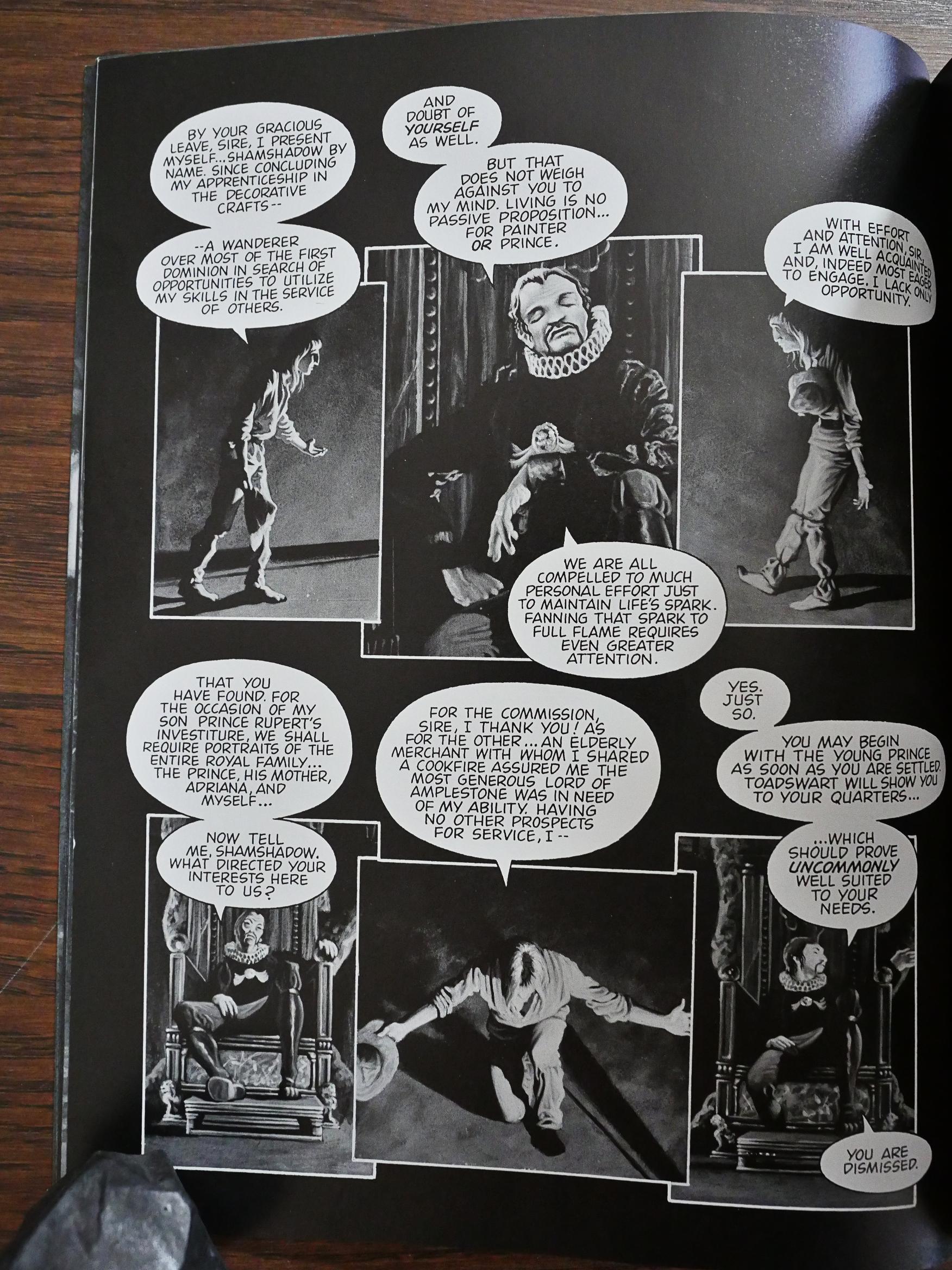

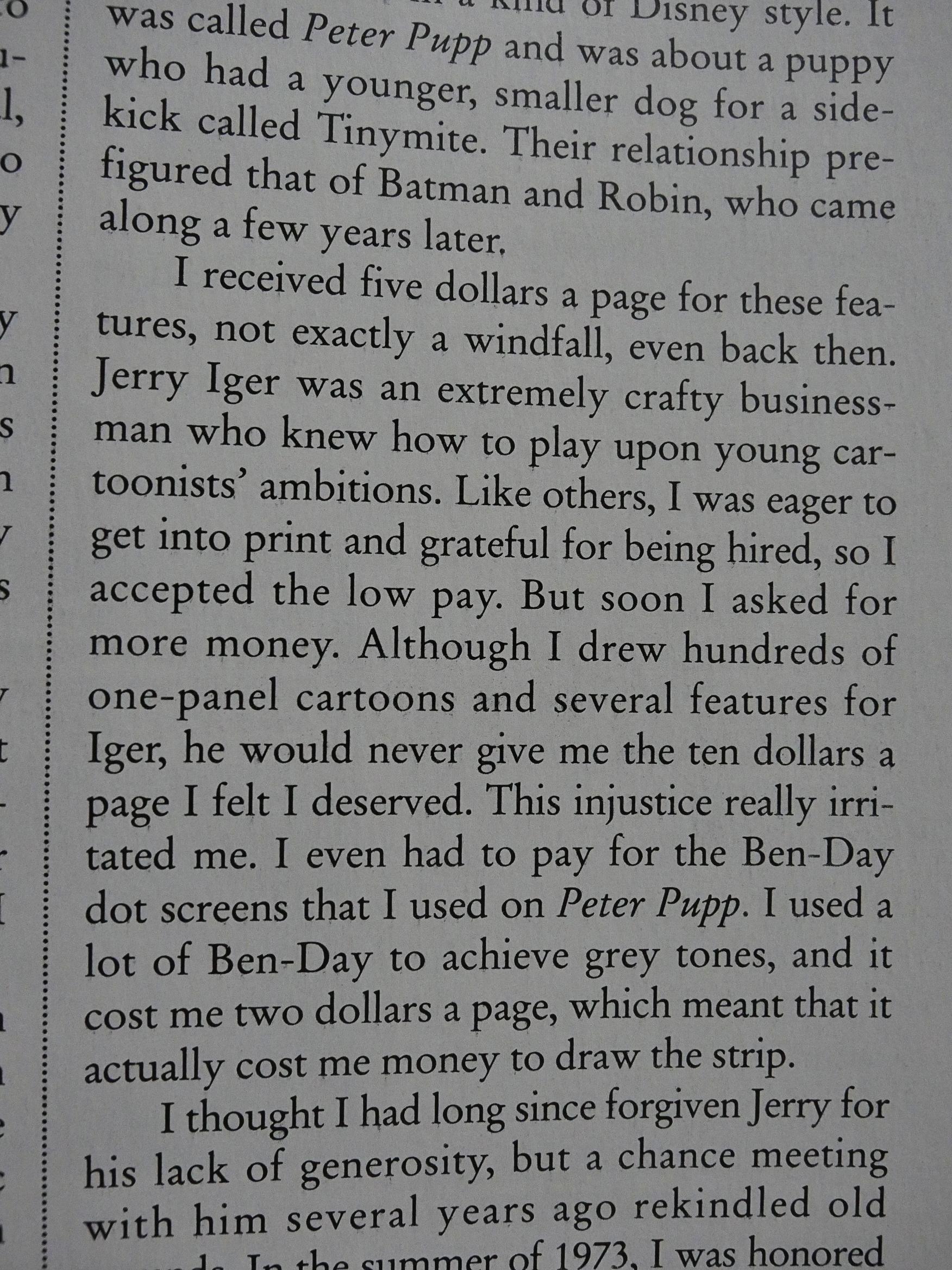

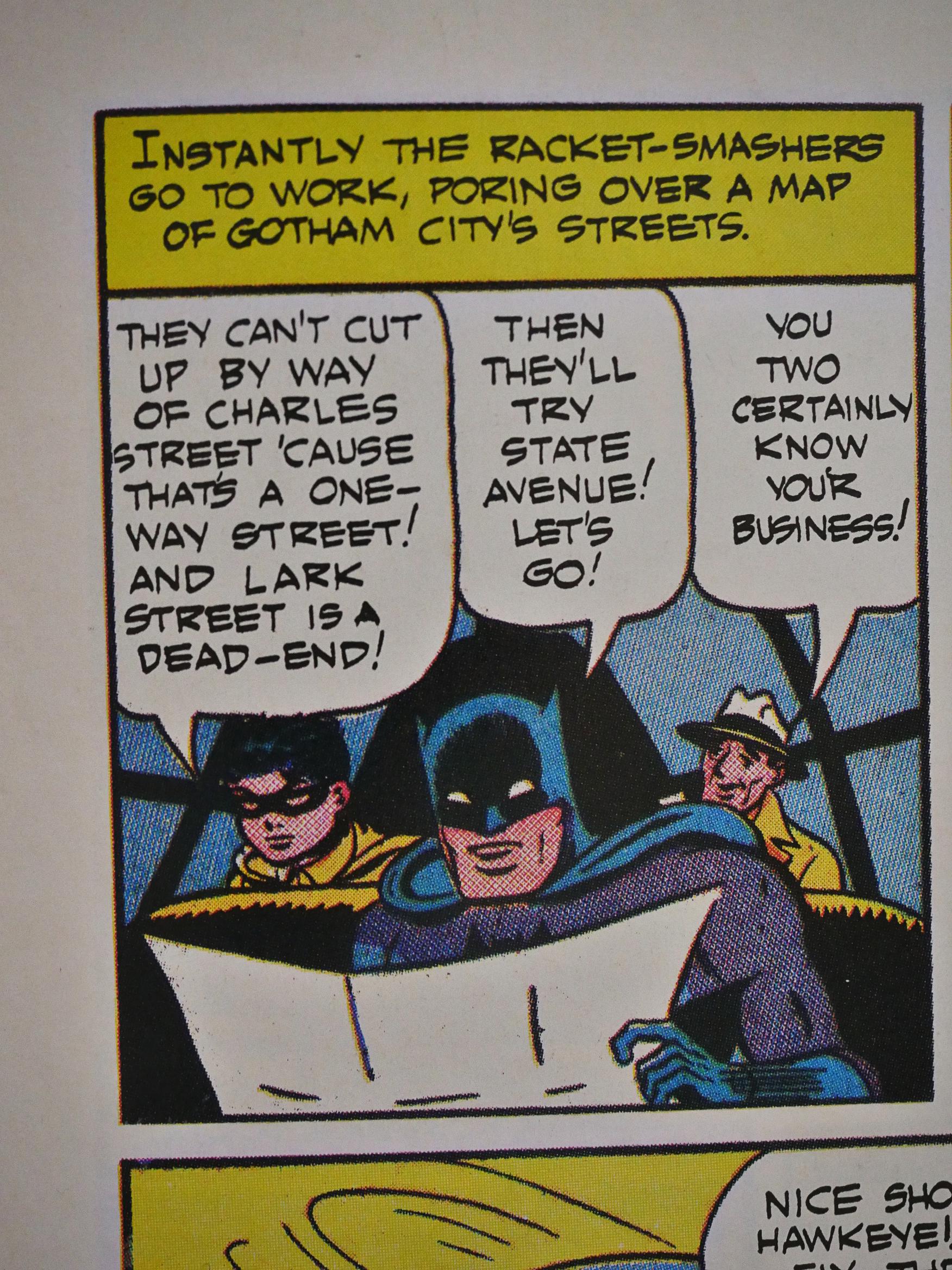

This is very similar to the Clive Barker anthology in many ways. It’s also squarebound, around 50 pages long, features mostly fully-painted artwork, and ex-editor Fred Burke does most of the adaptations. And, as before Burke’s approach to adapting a short story into comic book story is to preserve as many of the original words as possible. His adaptations almost don’t function as comics at all, but more as illustrated stories.

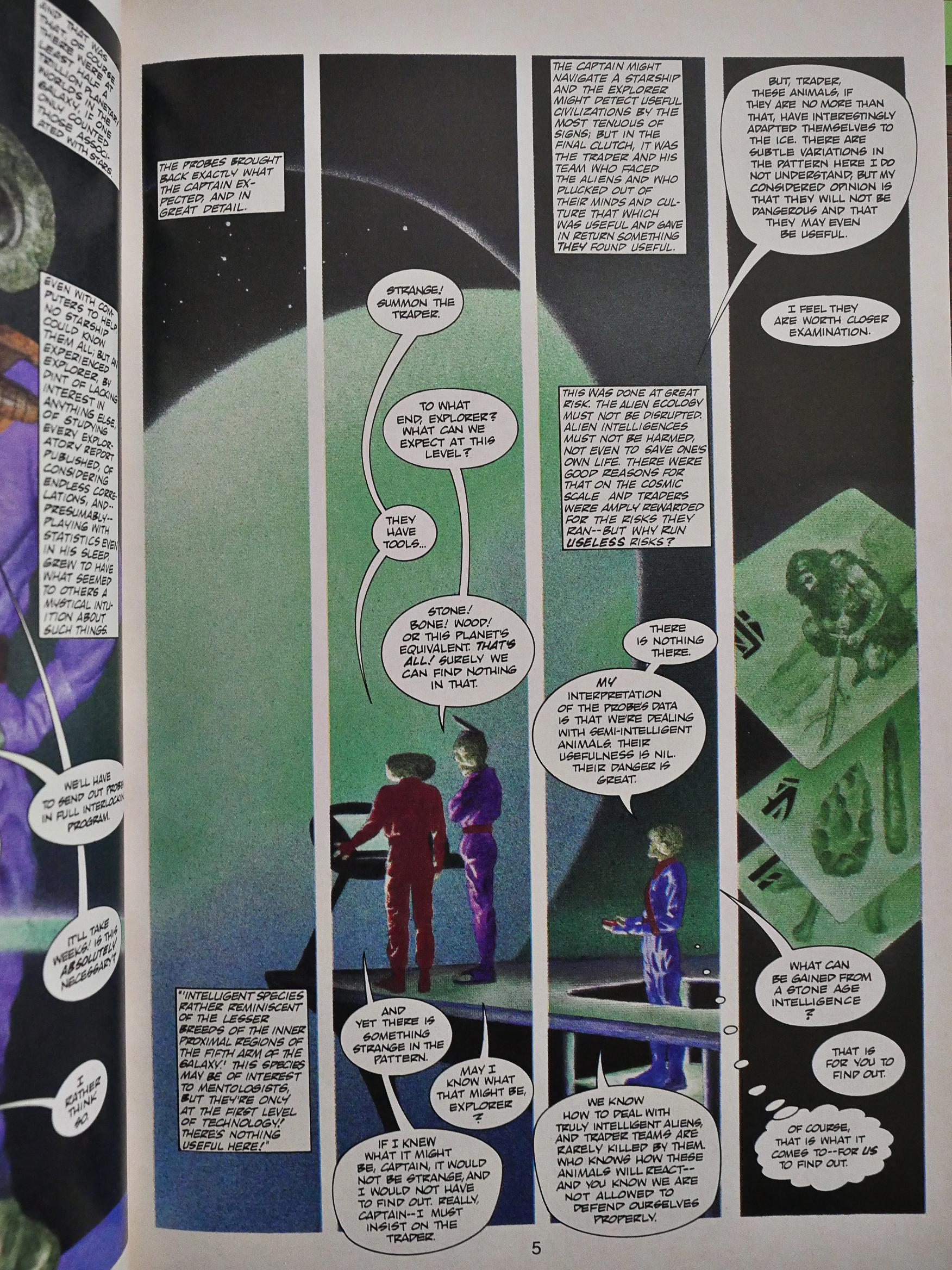

So it illustrators like John Bolton don’t really have much space to work… especially since all these adaptations are around 14 pages long (so there’s three stories per issue).

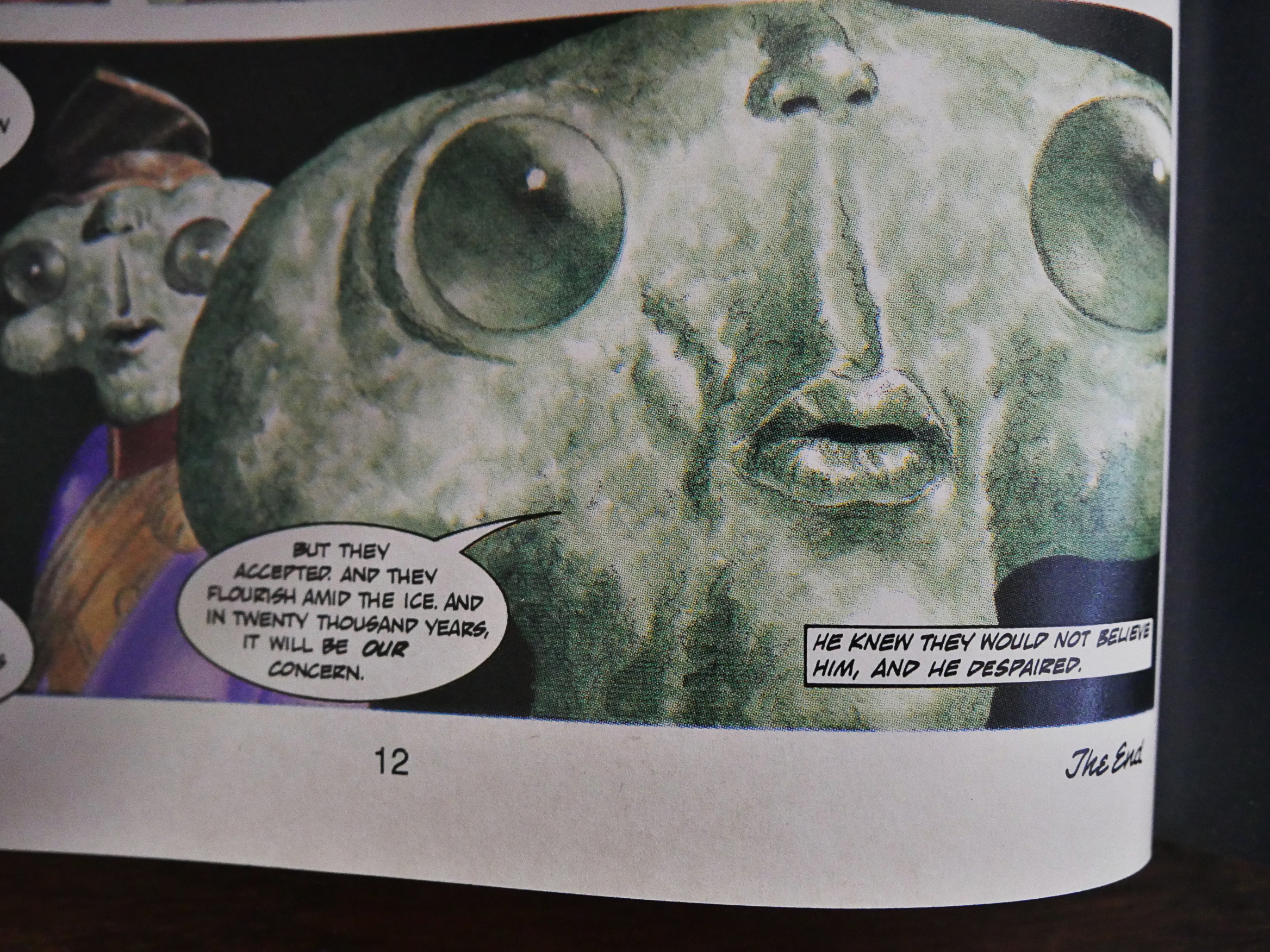

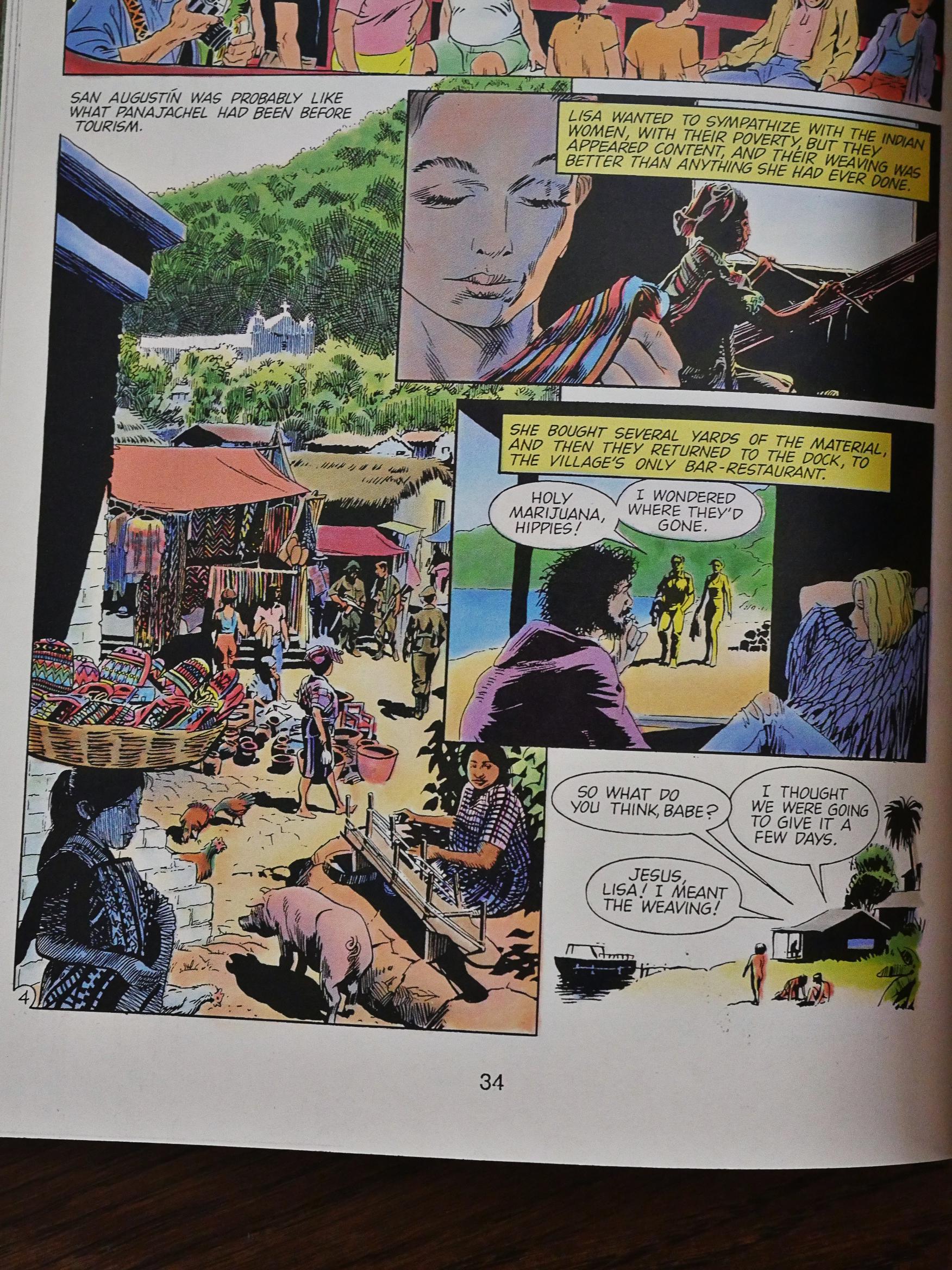

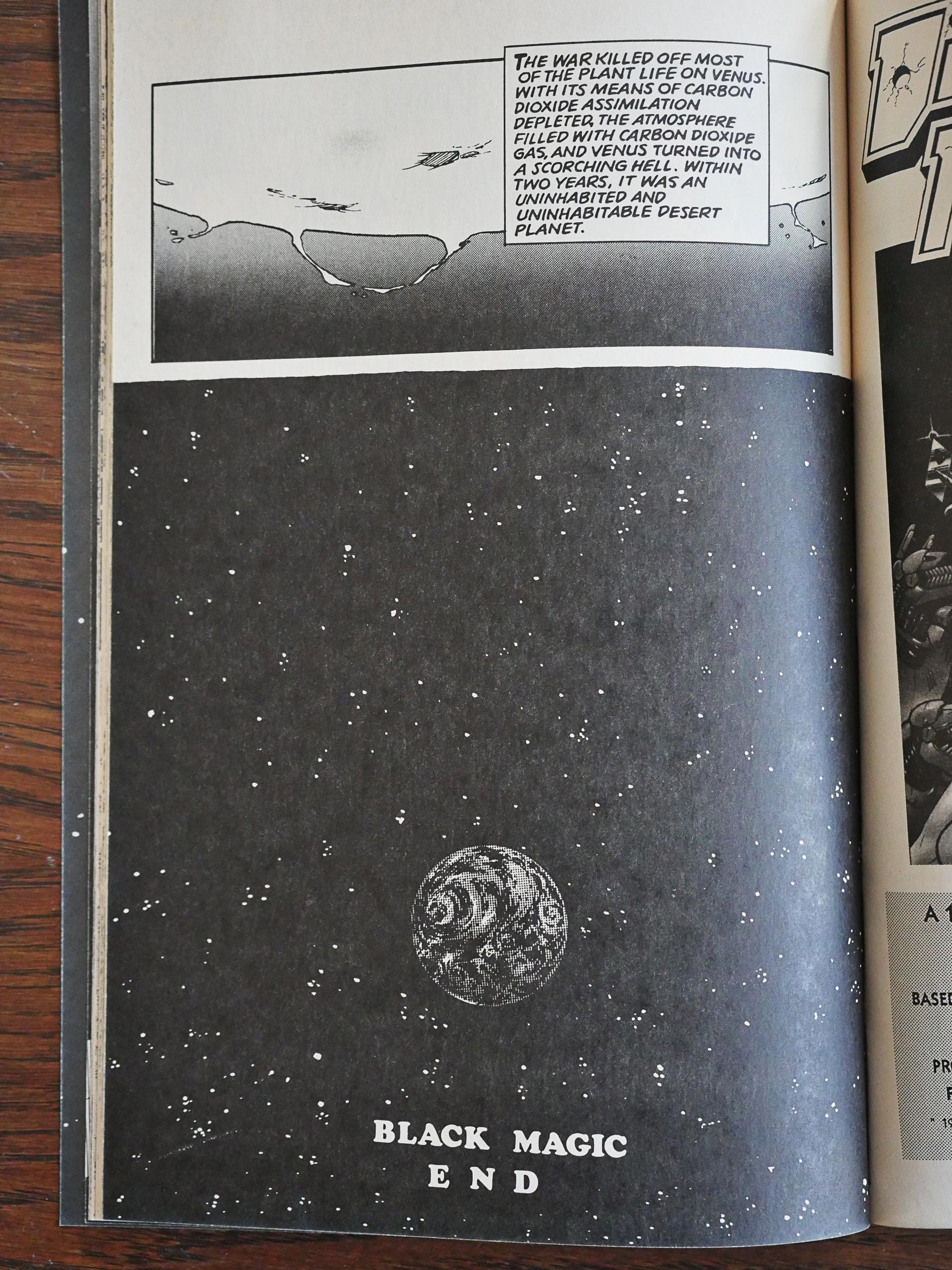

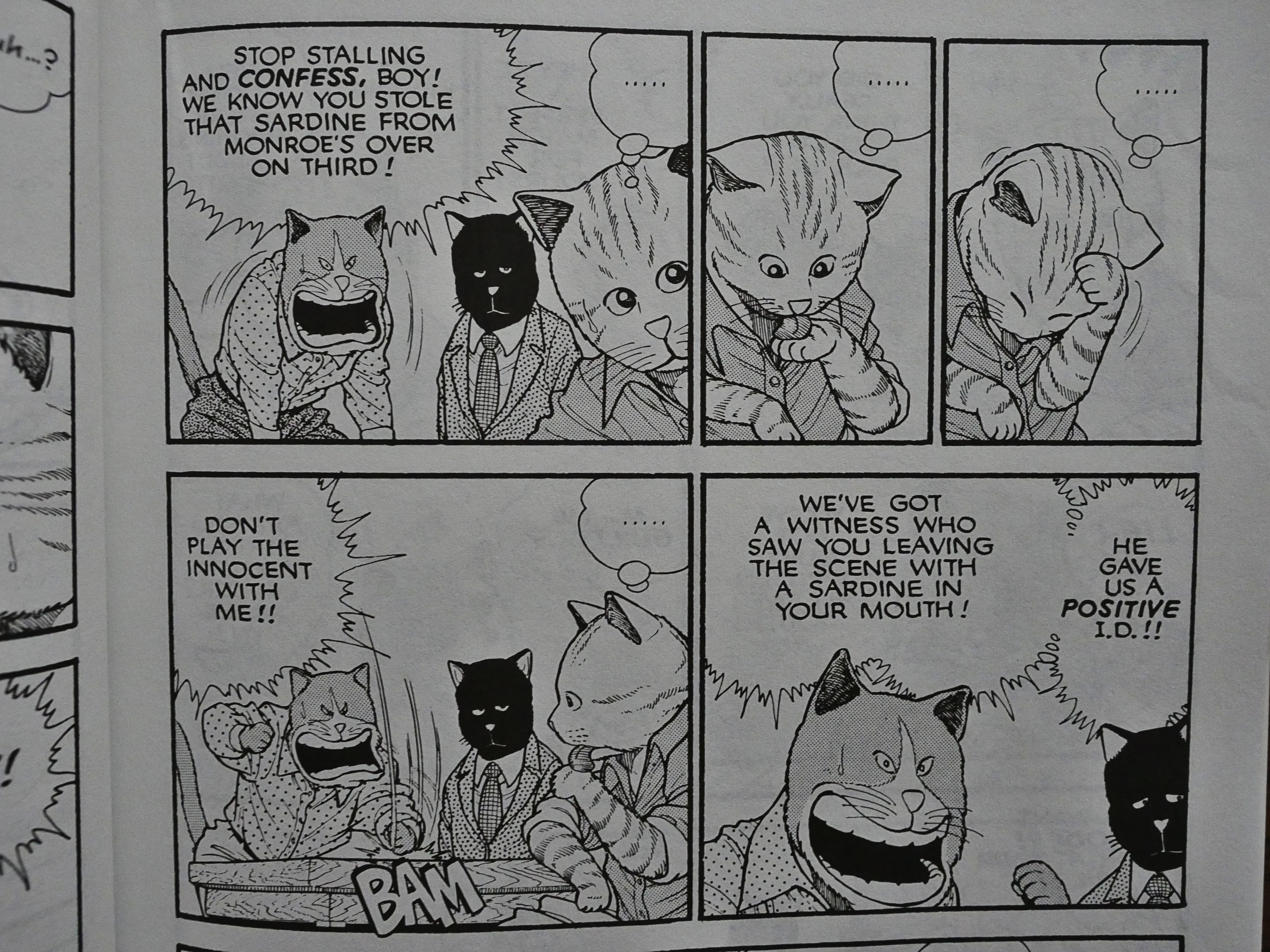

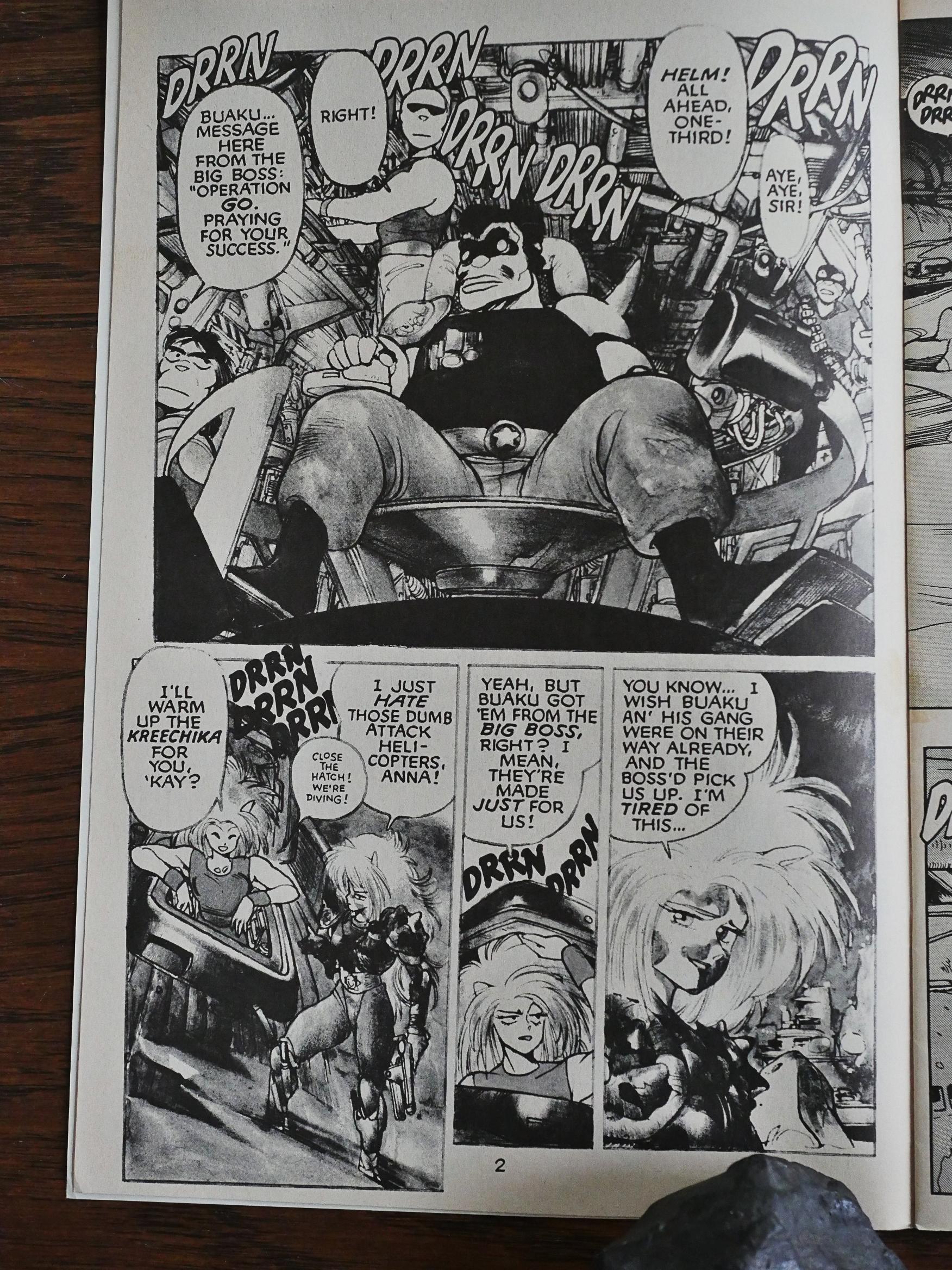

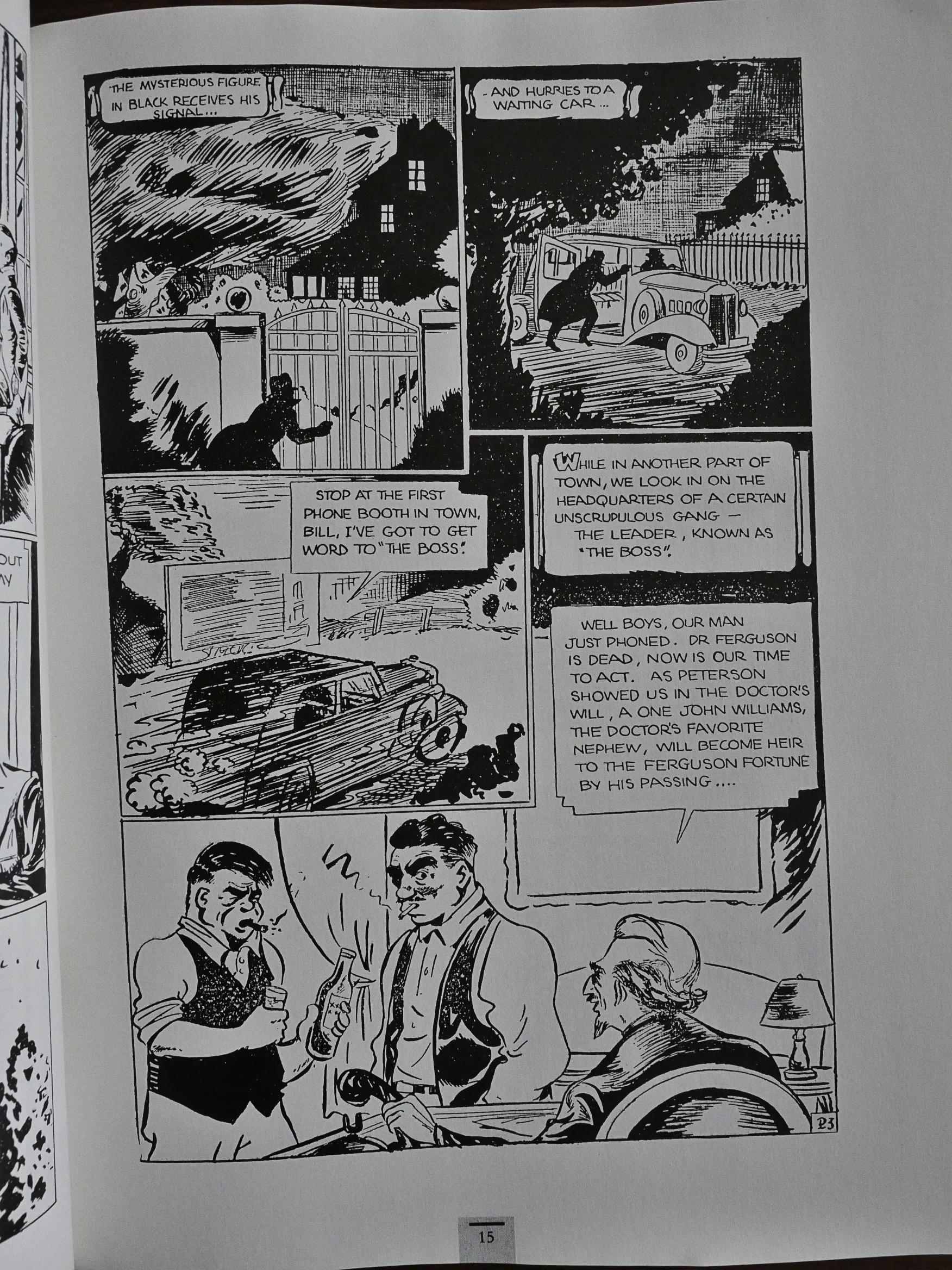

Some of these pieces survive in what I imagine is a pretty unscathed fashion: I can totally see the above piece being faithful to the original Asimov story, for better or worse.

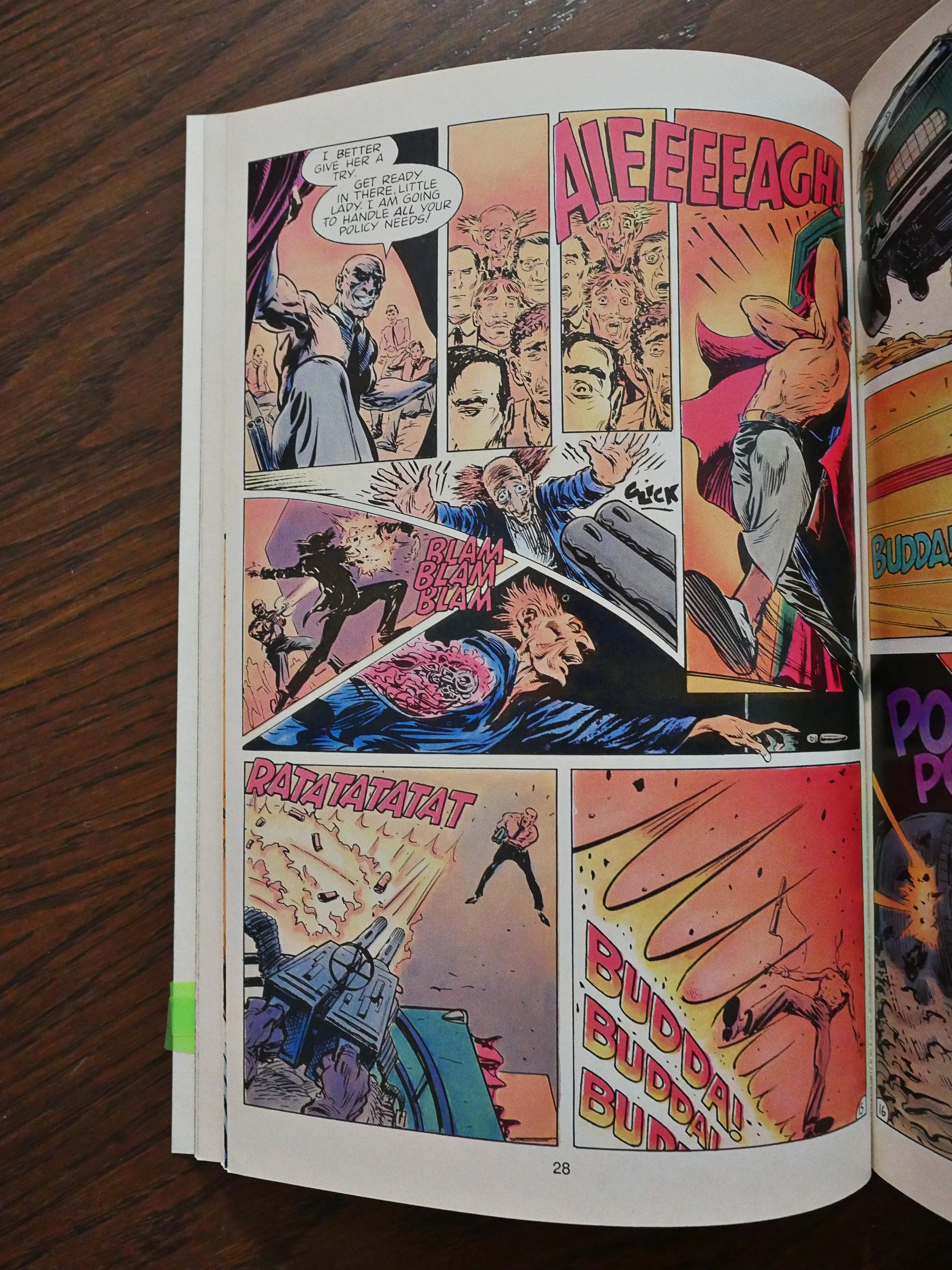

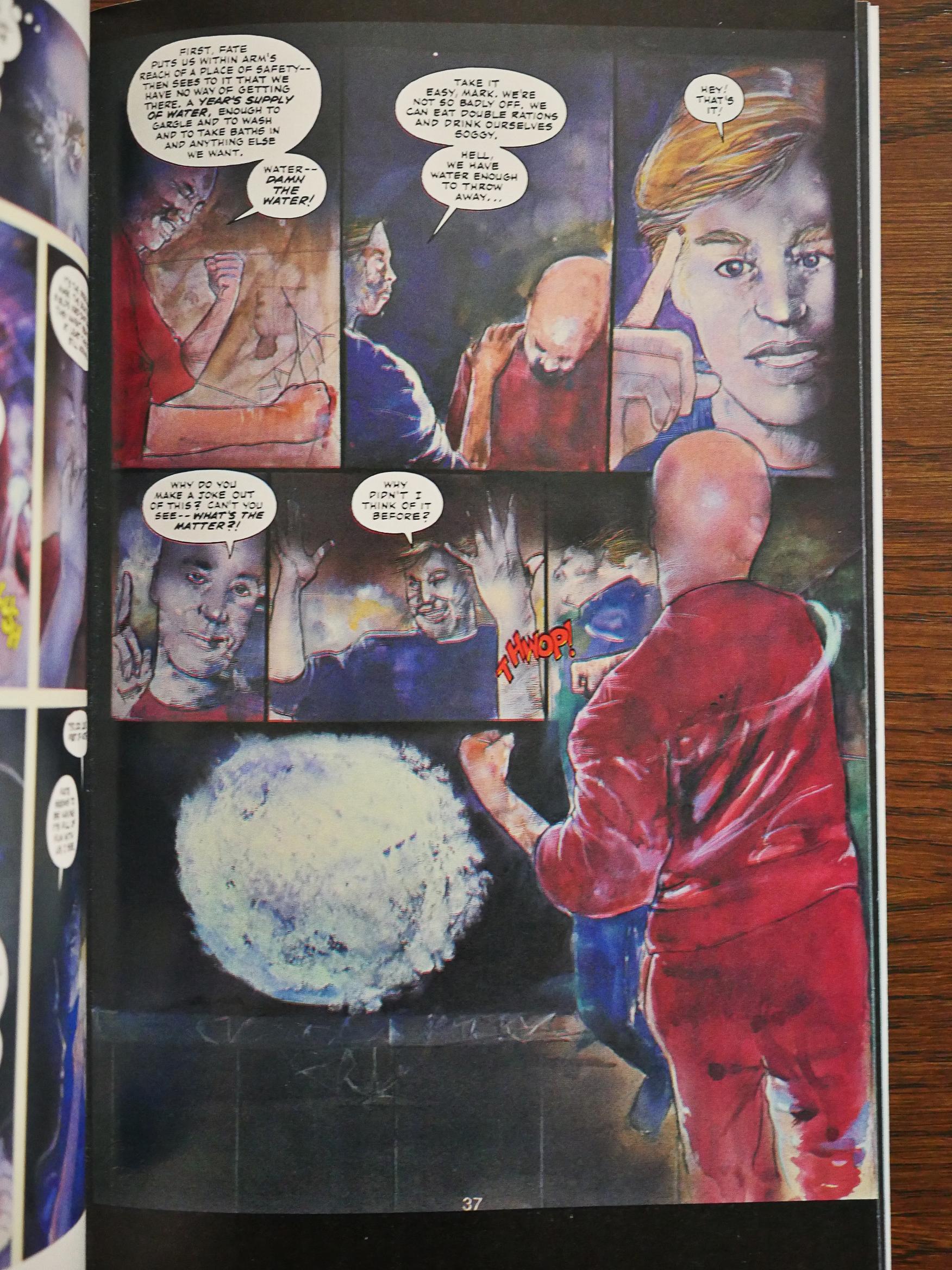

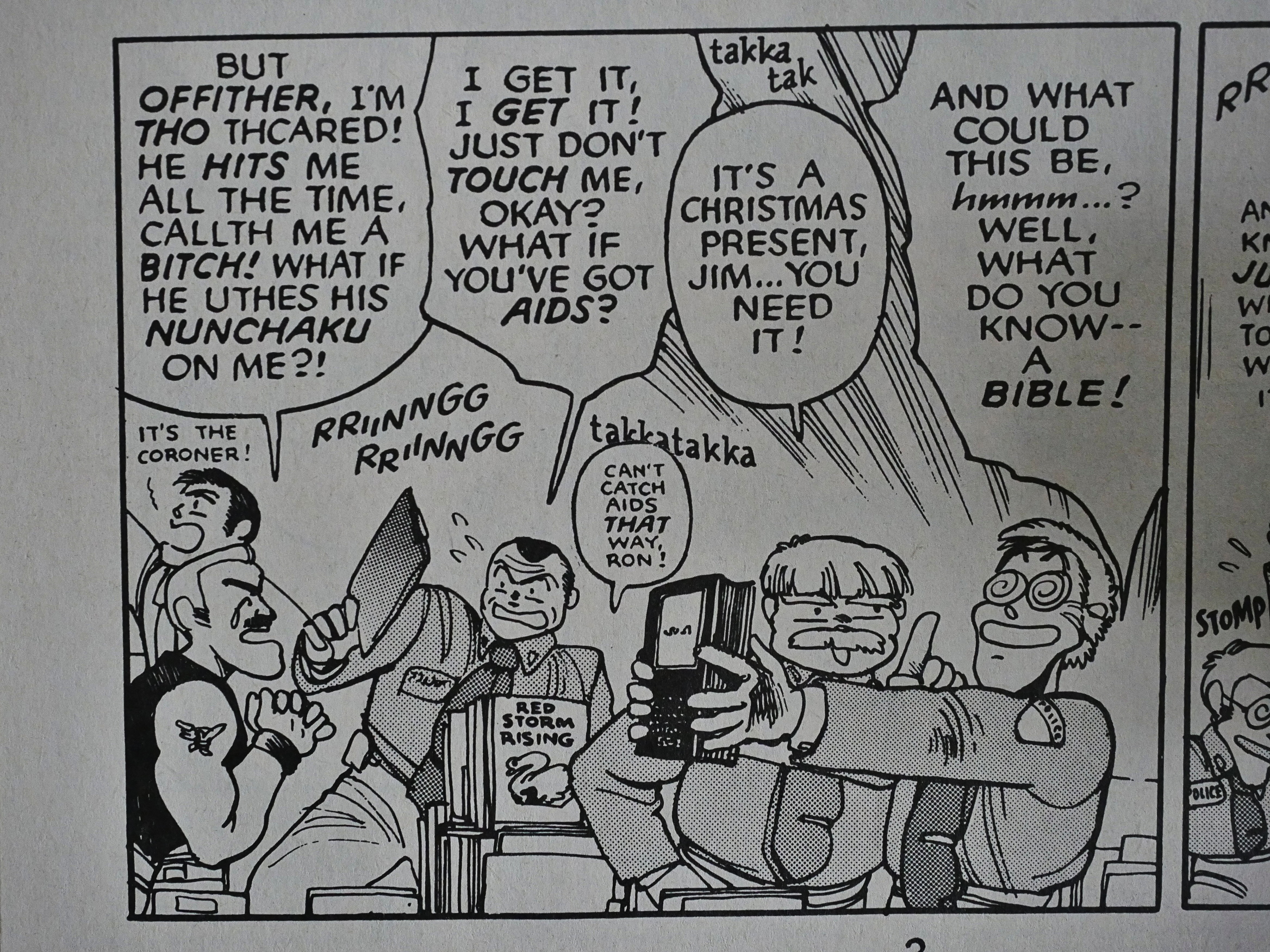

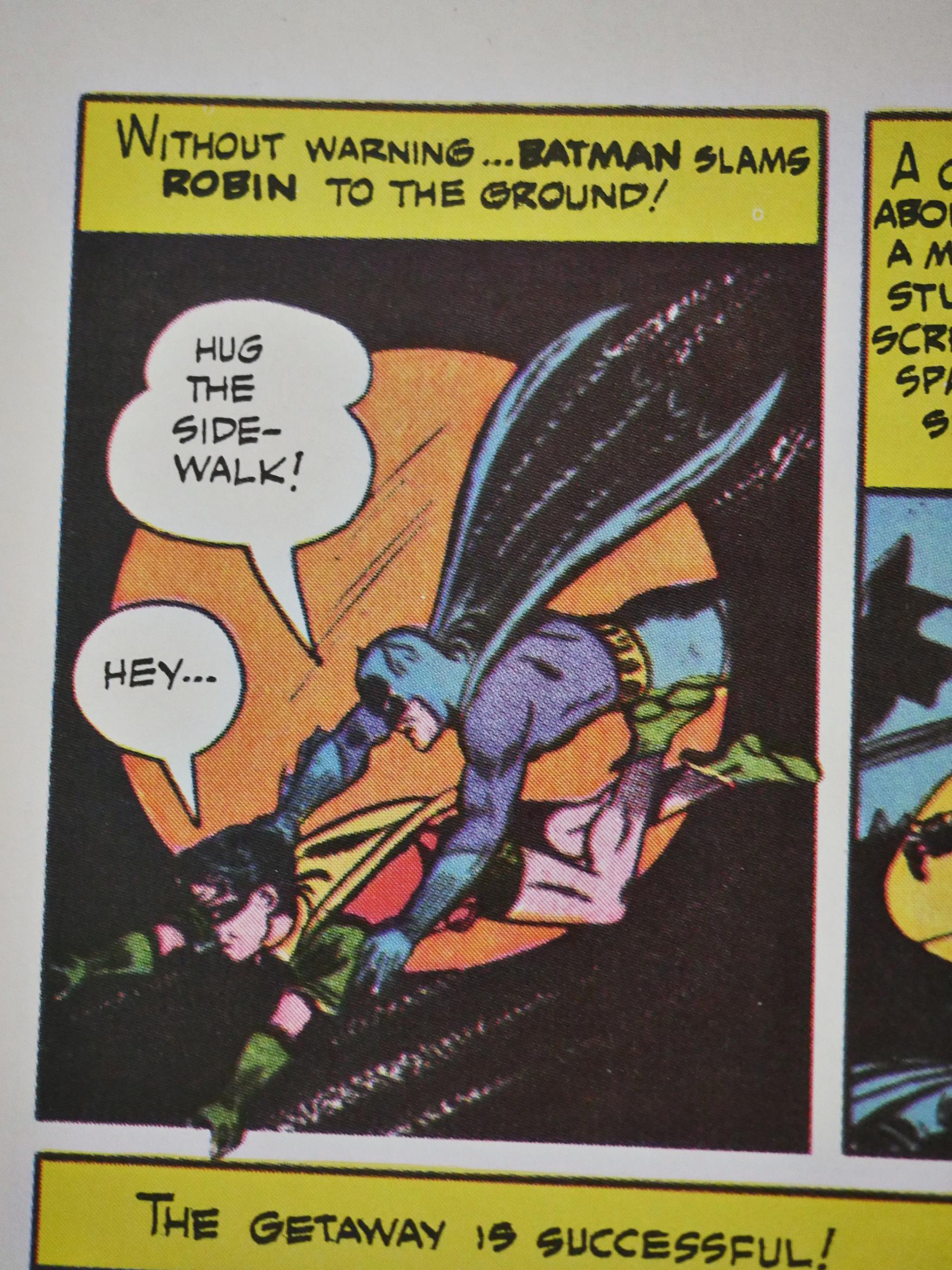

Leslie Clague and Steve Niles pare down the word count considerably for their version of the Neal Barrett, Jr. story, so it kinda works, but the story is a bit of a mess and Mark Pacella’s artwork, while moving a lot better than most of the panels in this series, isn’t very exciting.

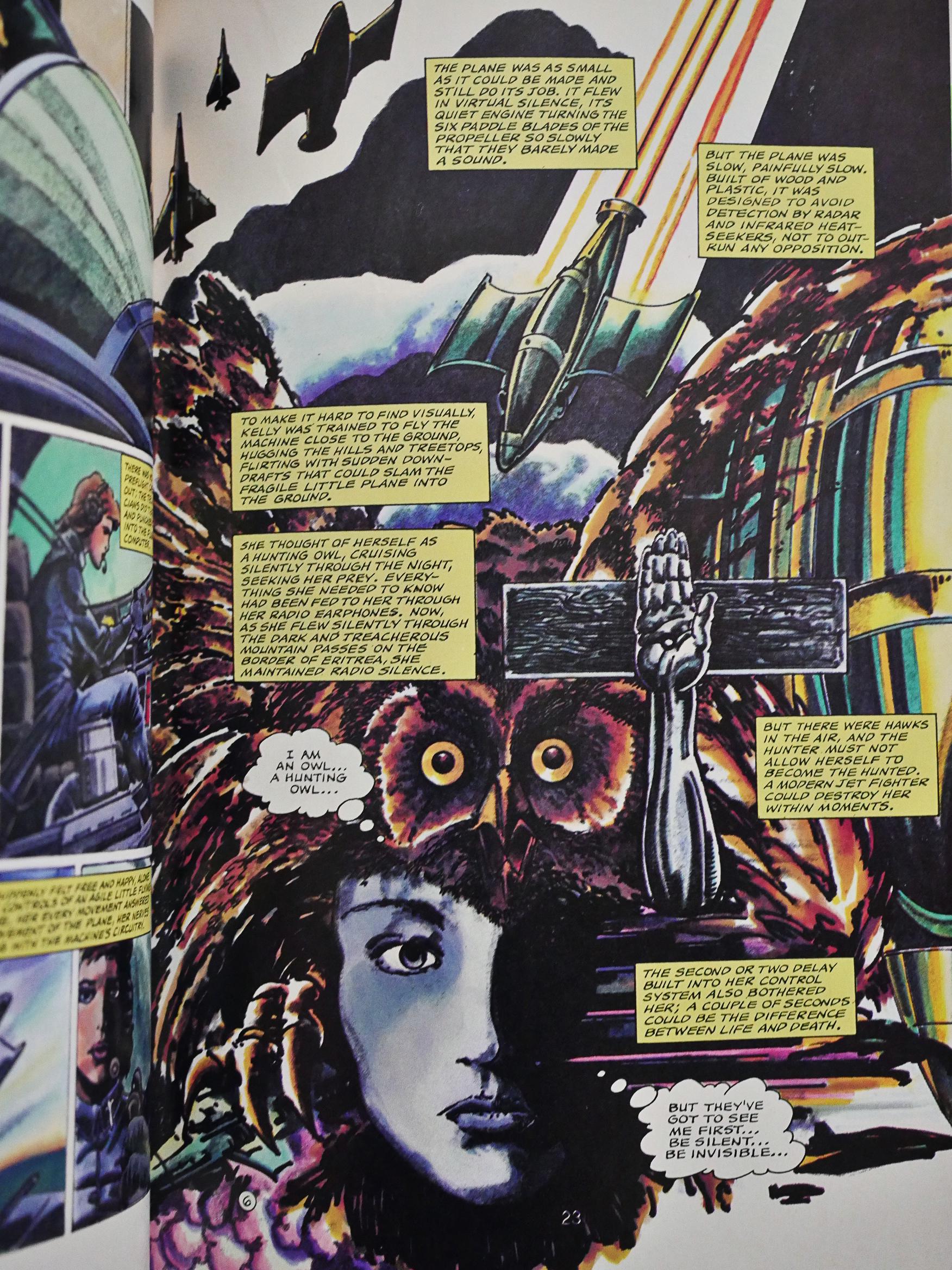

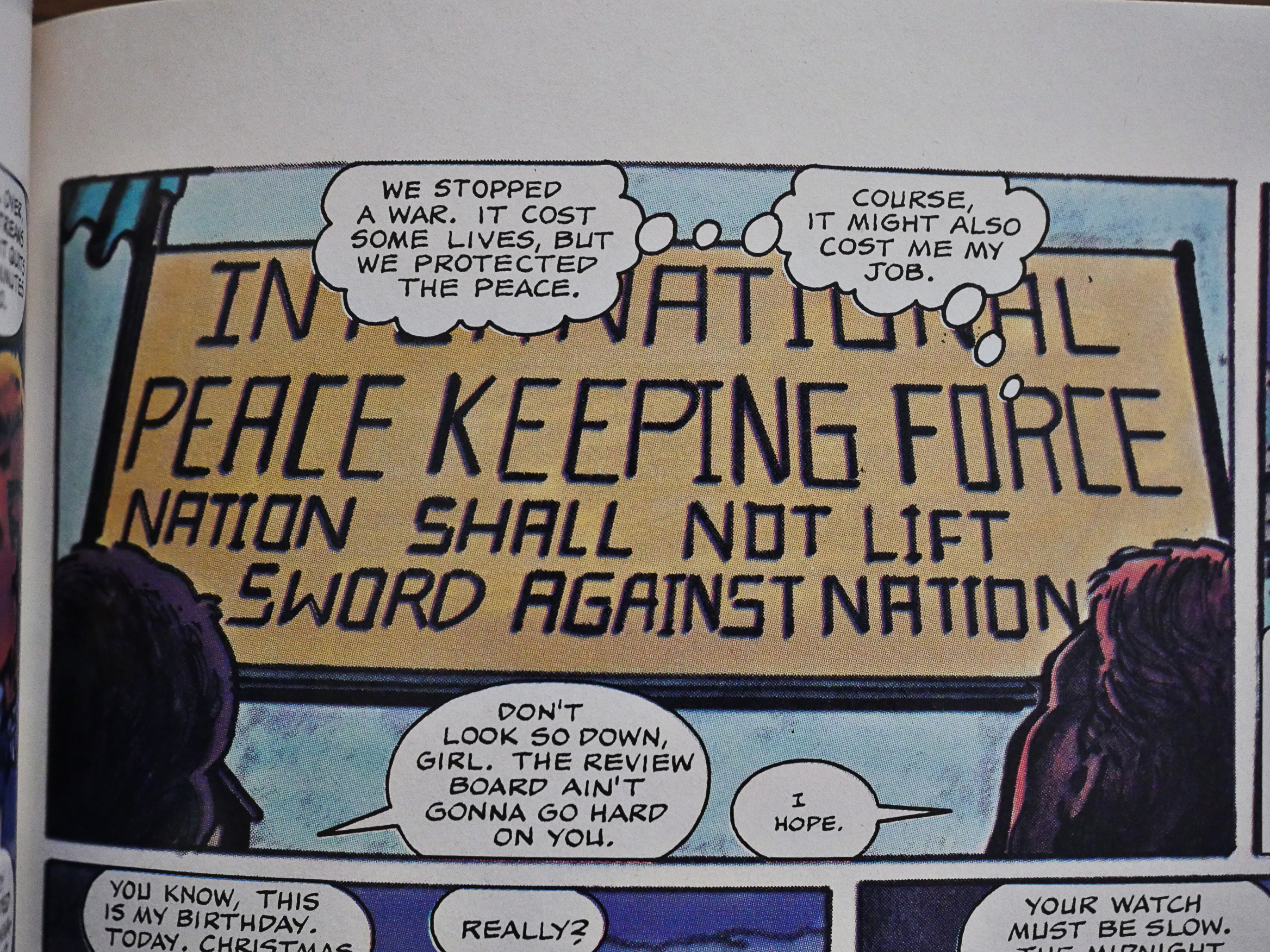

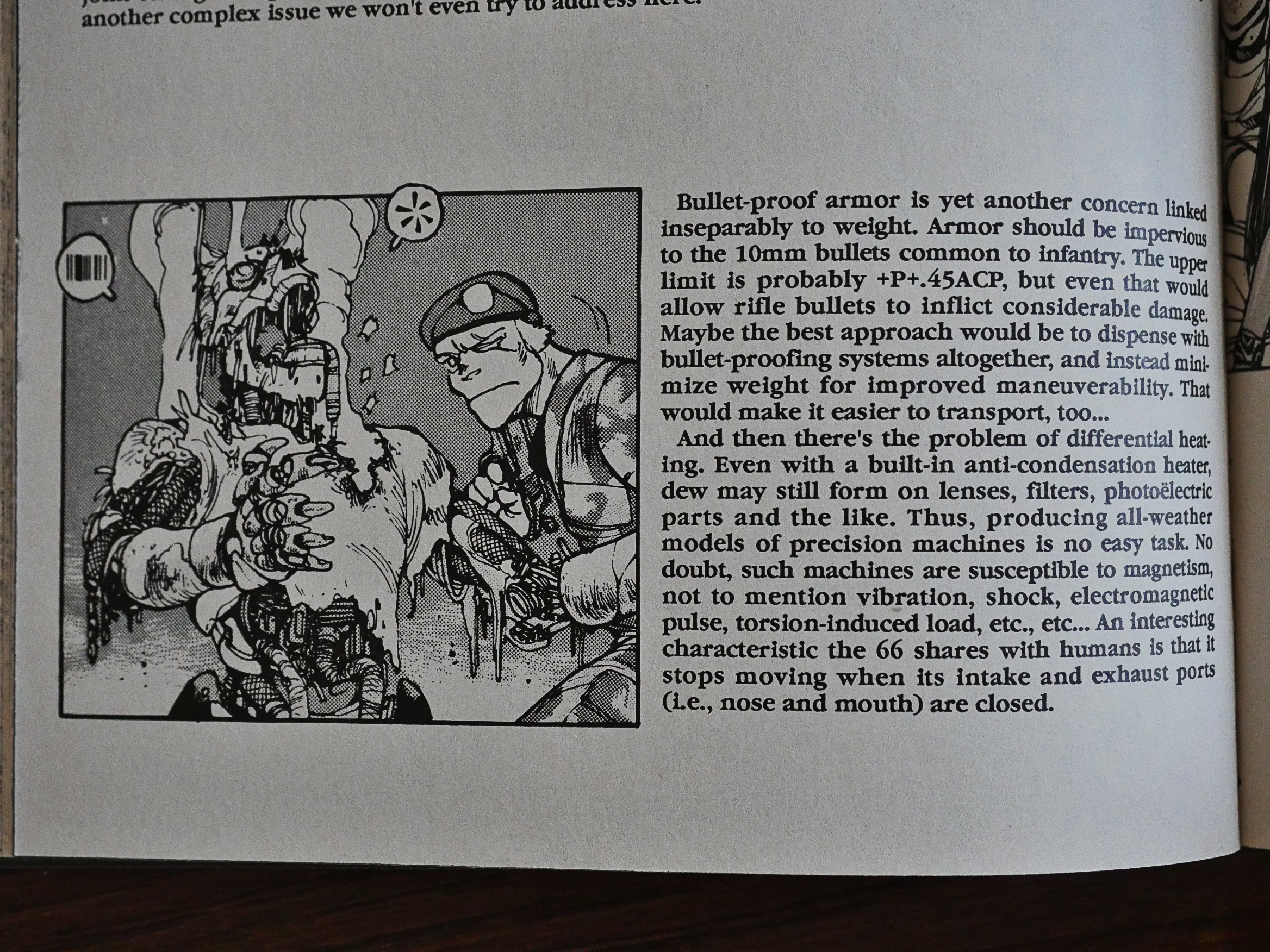

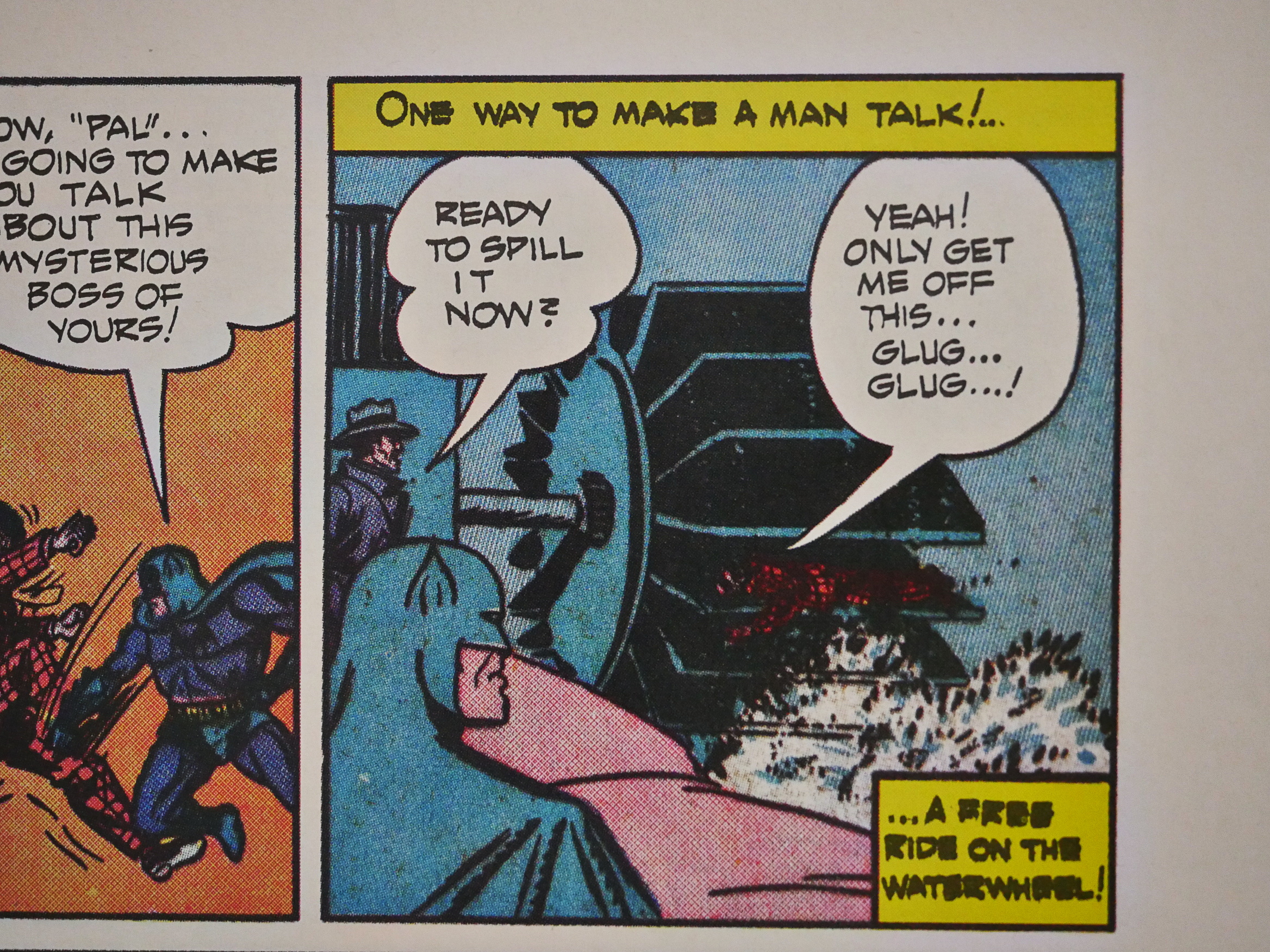

The Burke/Rafael Kayanan version of a Ben Bova story is probably the weirdest thing here, and I’m guessing it’s all down to Kayanan, because Burke is verbose as usual…

… and Bova’s point seems to be that drone pilots are people too. Or something.

Perhaps they give this story as a reading assignment at the military stations in Nevada?

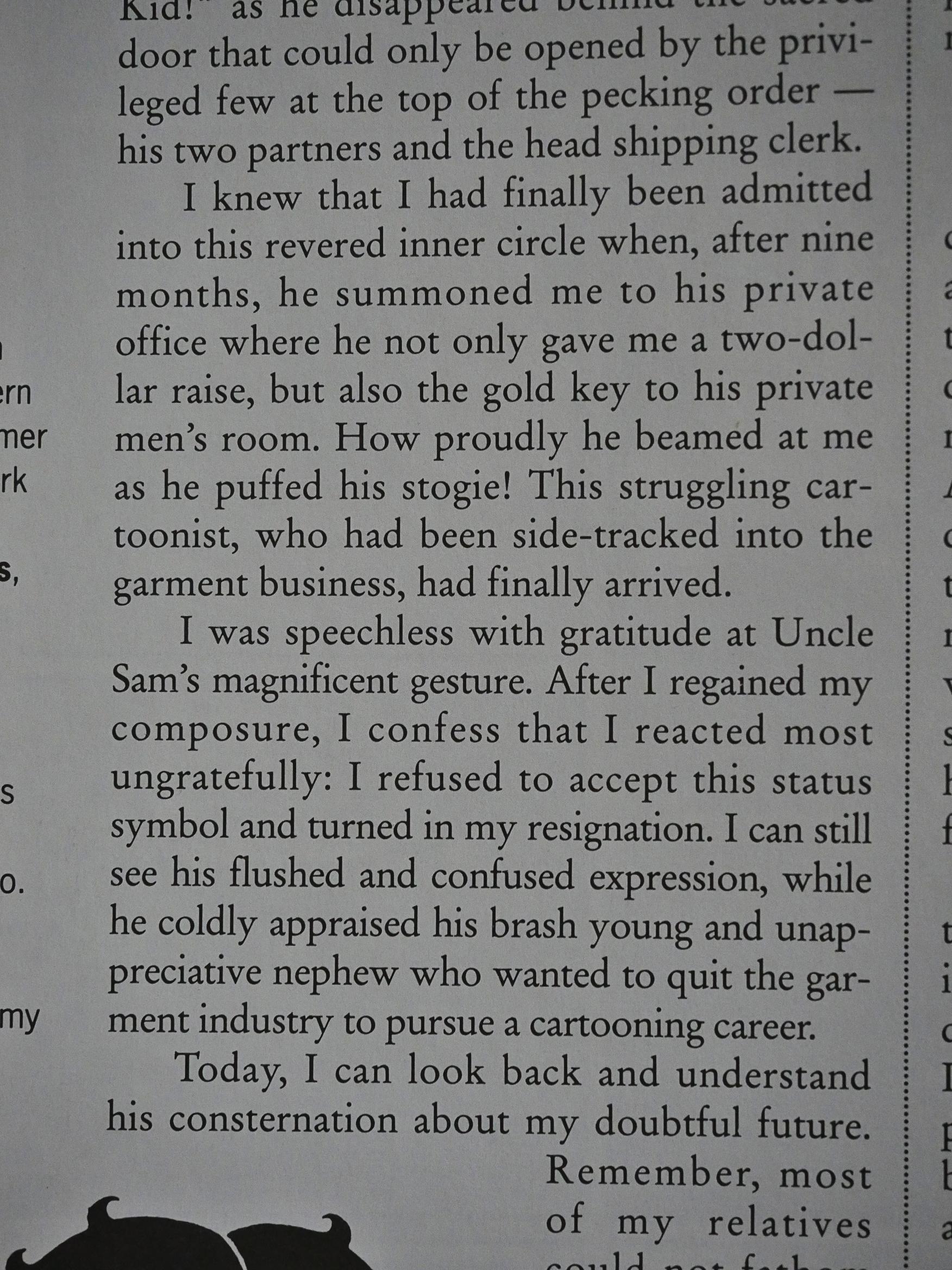

I get the attraction of painted artwork: It looks a lot more luxe and adult and less comic-bookey, which seemed important when going after a bookstore market. (But then it turned out that the bookstore market wanted a black and white pen-and-ink book about a Maus instead.) But some of these artists are almost completely unable to tell a story, like in the JD Scott/Michael Davis piece above.

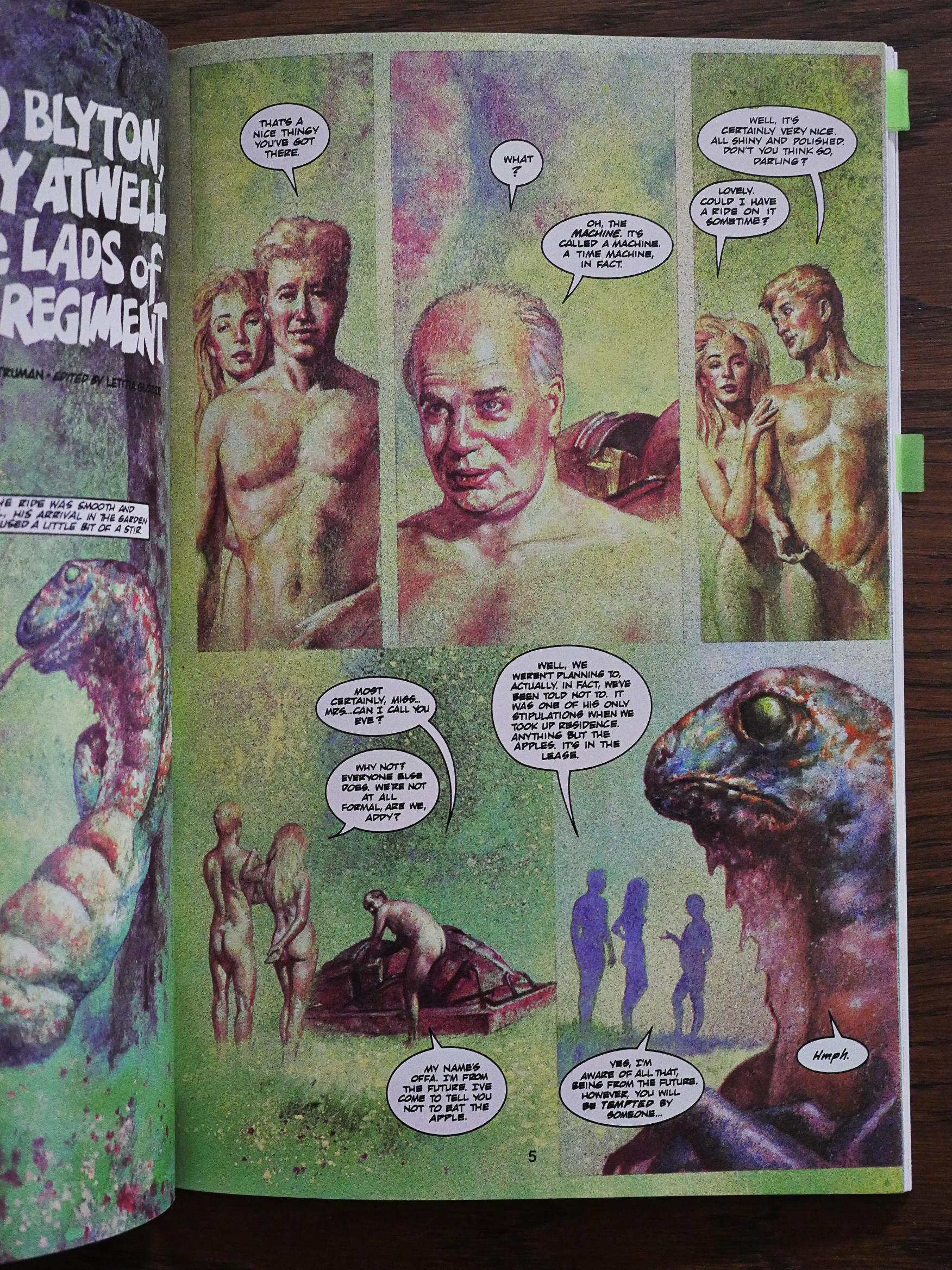

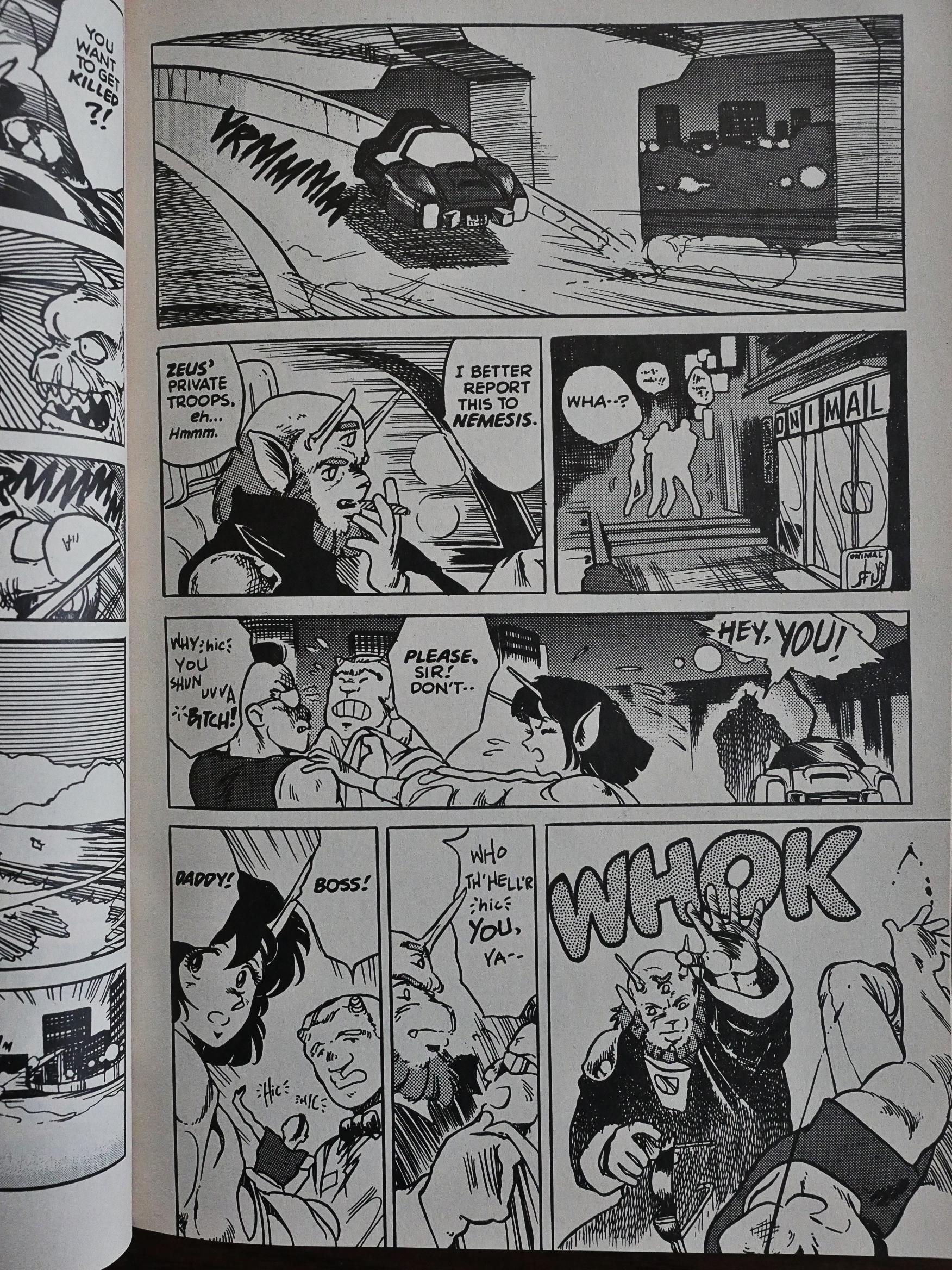

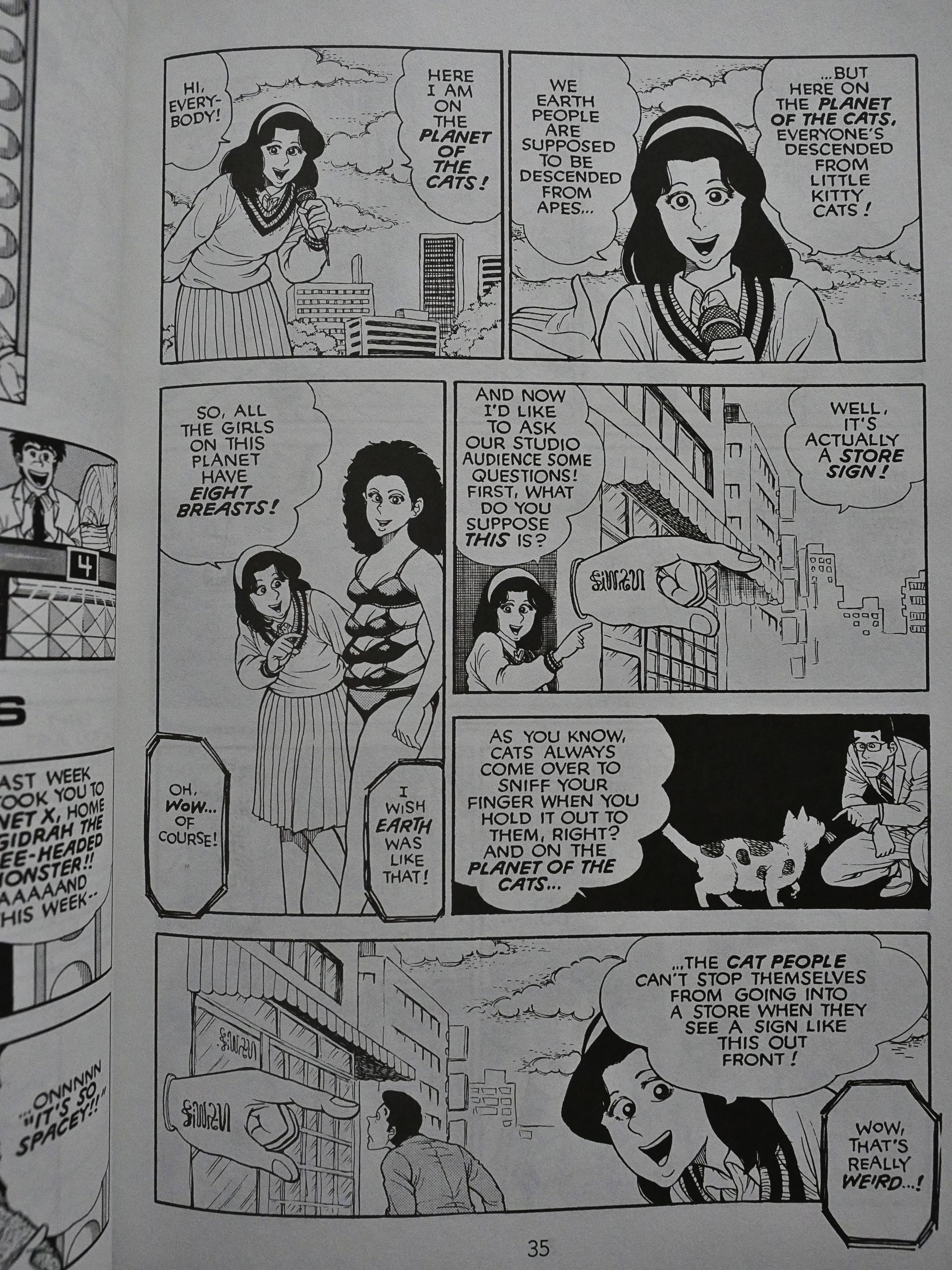

John Bolton to the rescue! And for once, Burke keeps the exposition down. On the other hand, this story (by Garry Kilworth) is little more than an extended joke, so 14 pages is more than enough to tell it in a leisurely fashion.

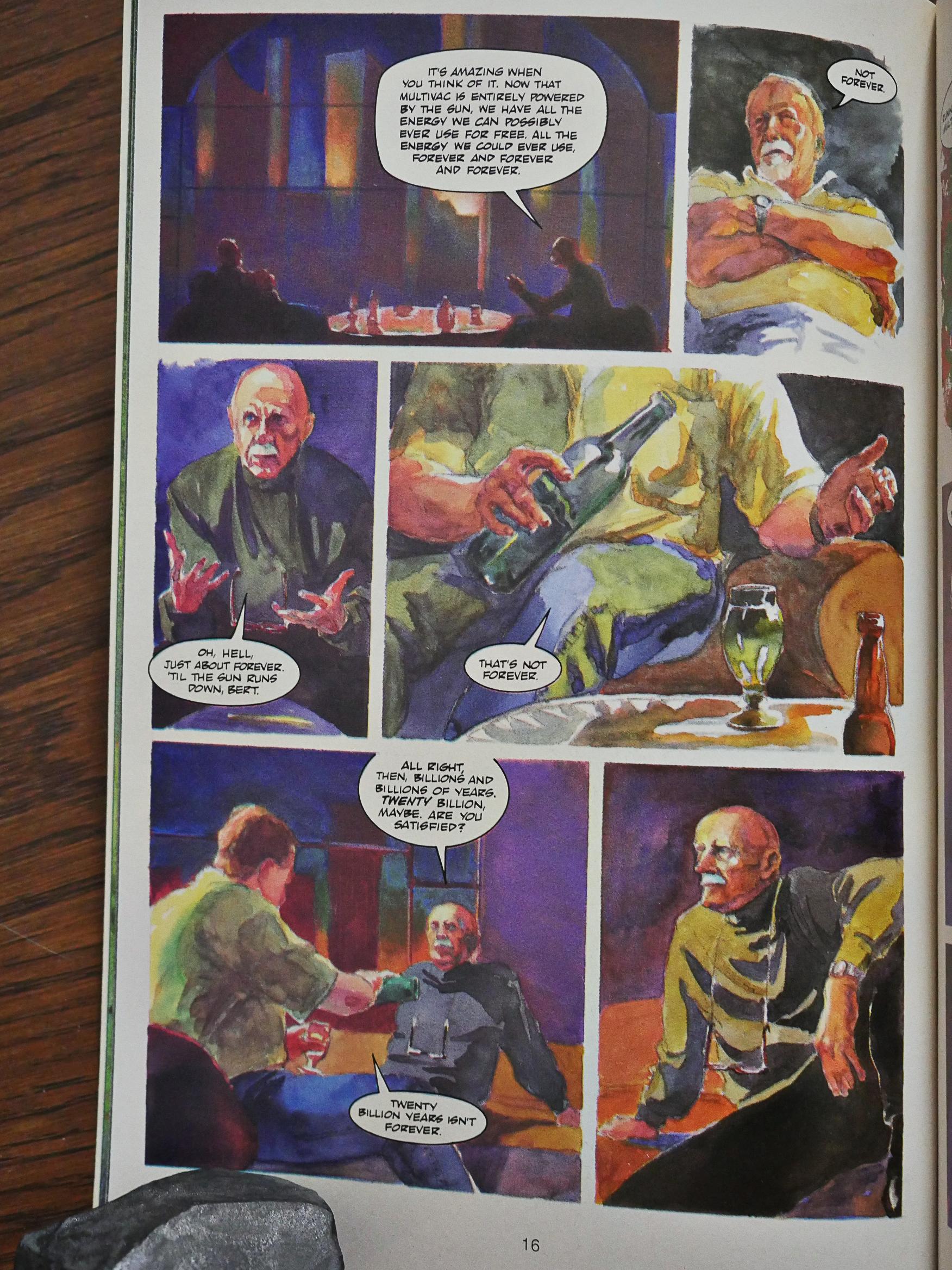

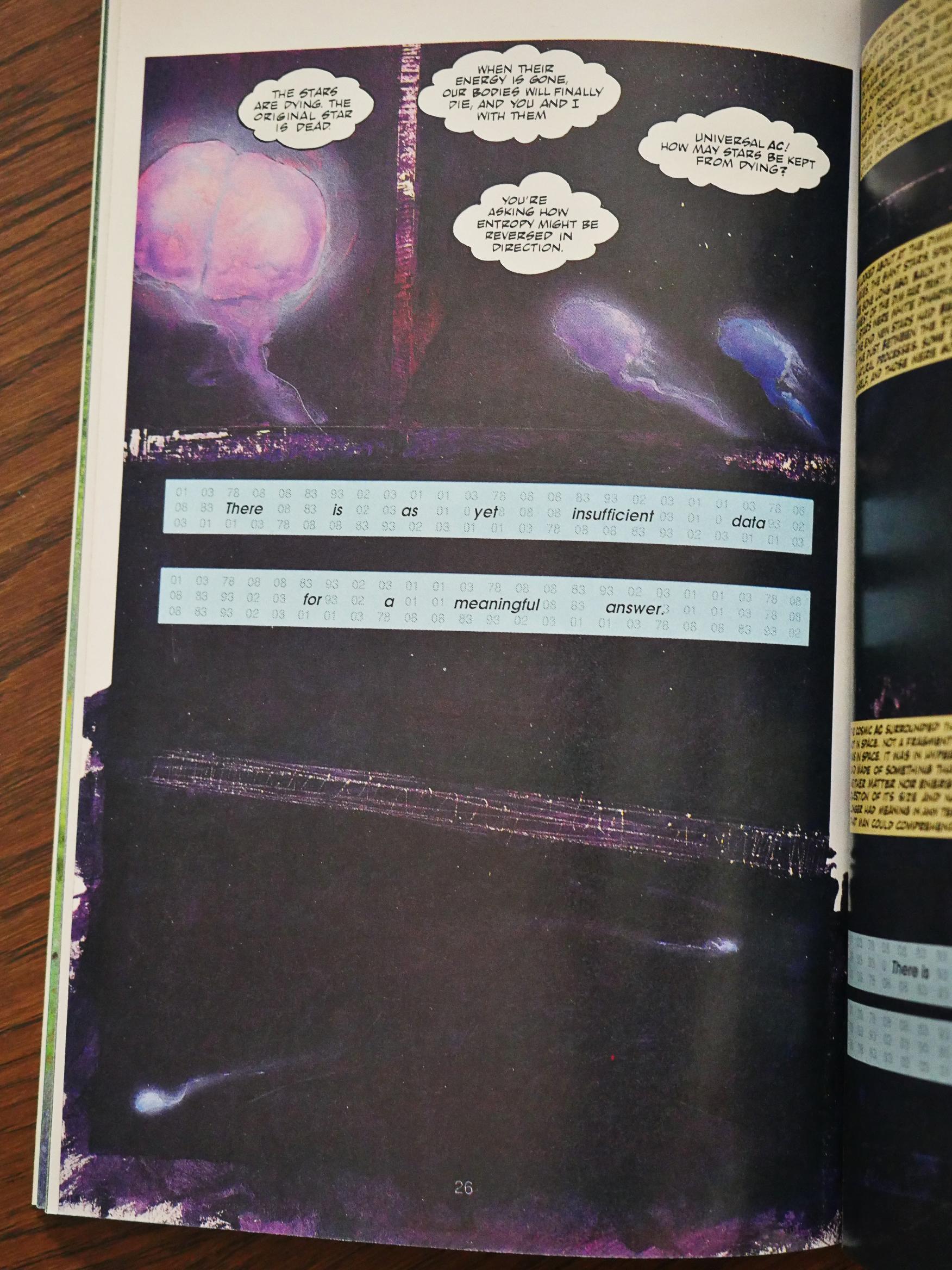

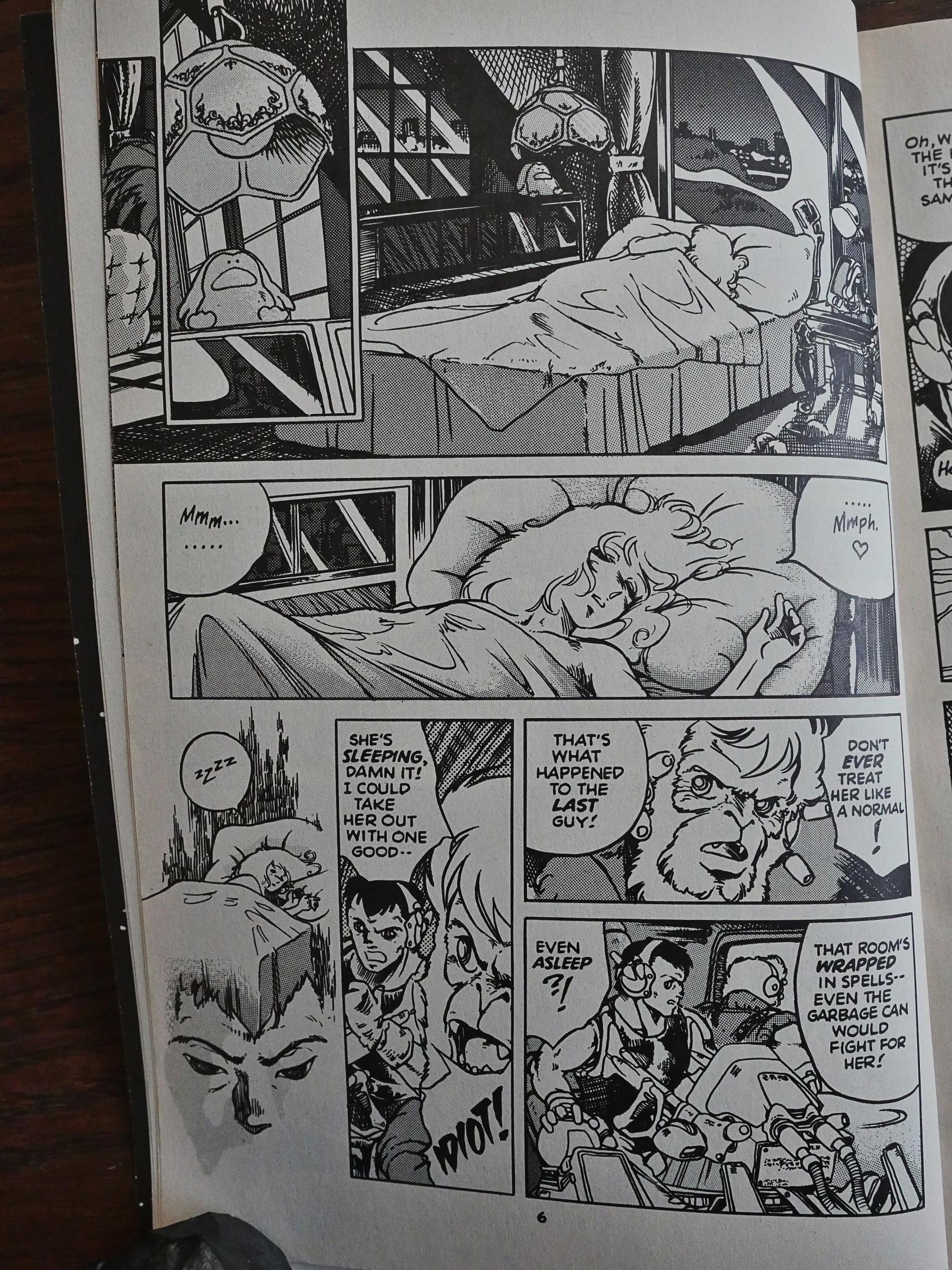

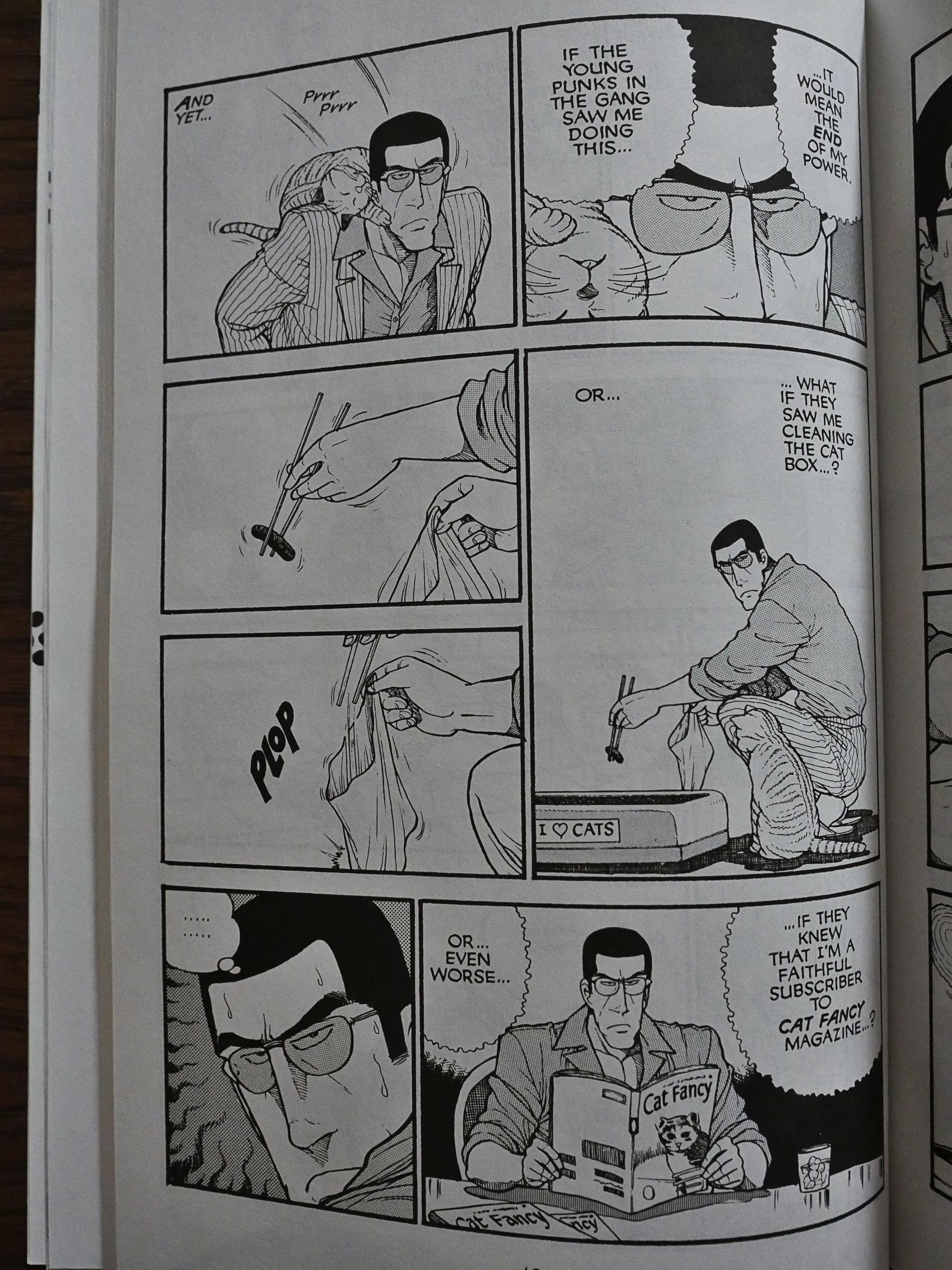

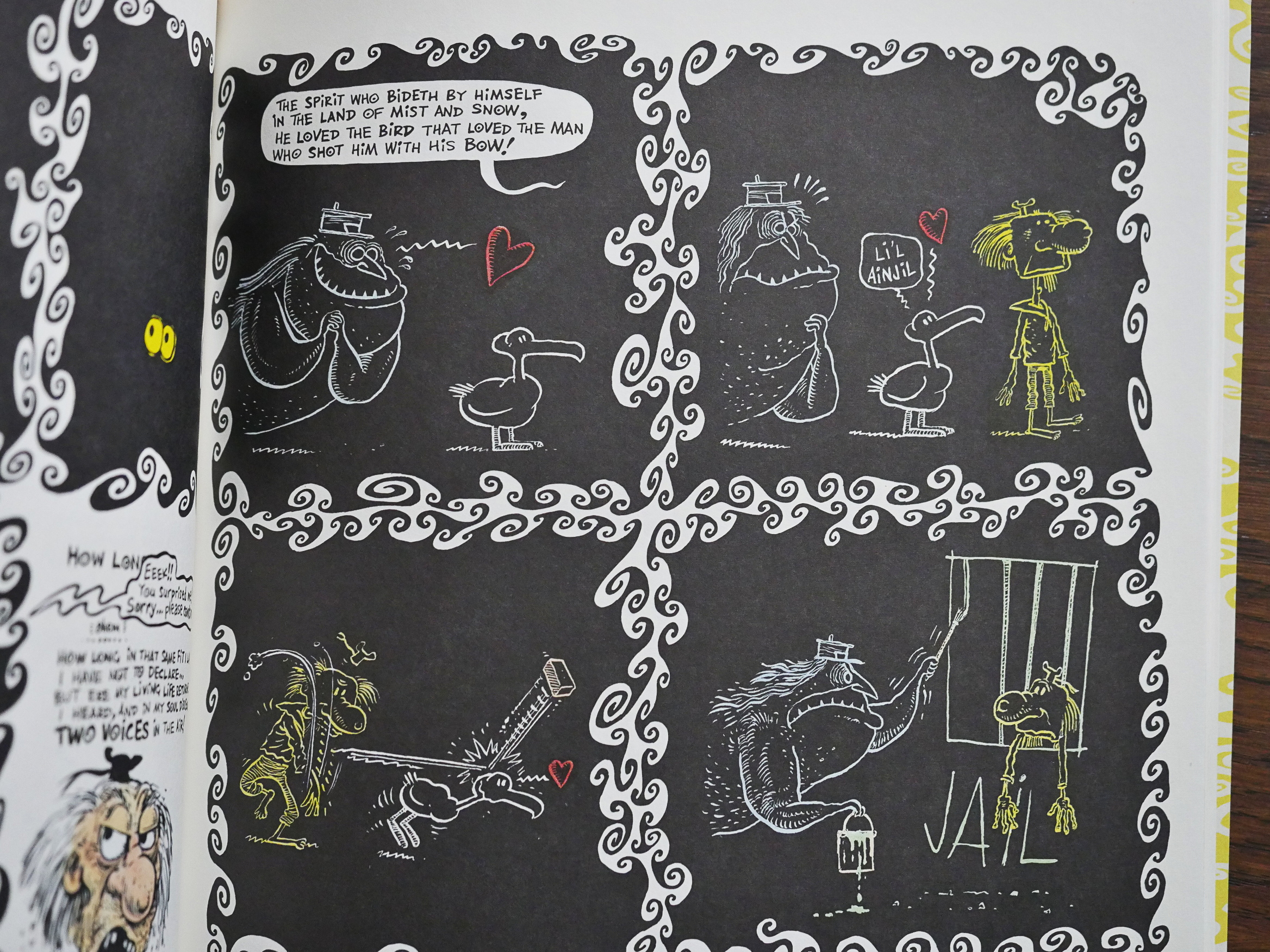

John Estes does a great job on this Don Thompson adaptation of an Asimov story, that, again, is little more than an extended joke. Estes goes from this style…

… to this, as the story grows more abstract. It’s not a very interesting story, but the artwork almost makes you believe that it is.

Tom Yeates’ version of a Lucius Shepard story is probably the most successful one in these three issues, in that it has both a pretty interesting story and in that Yeates tells it really well.

All these three issues were released within a year, which is pretty unusual for these kinds of projects. So either they only had three issues in mind when they started it, or perhaps their co-editors at the Asimov magazine helped out keeping things rolling? I’m just guessing.