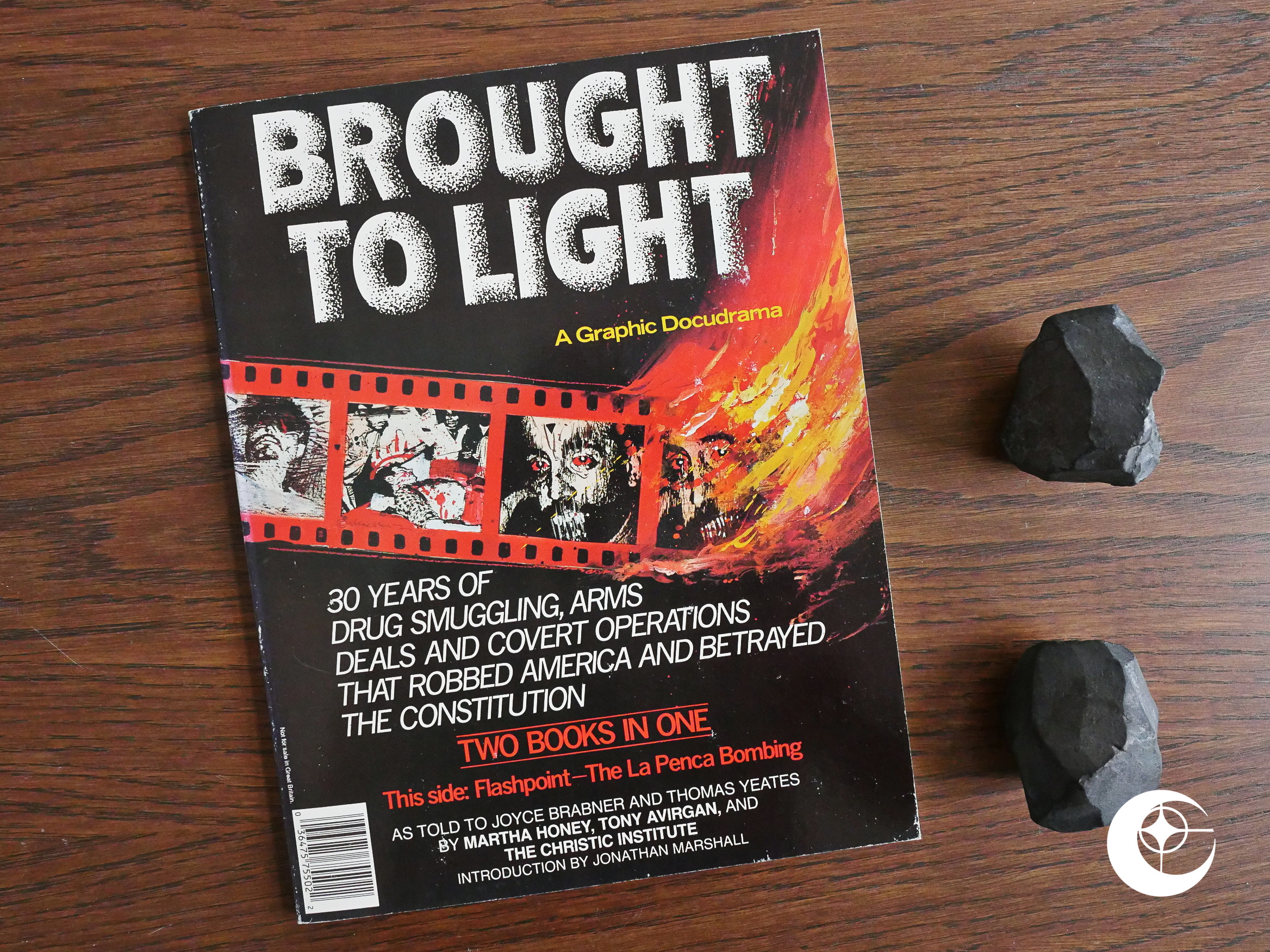

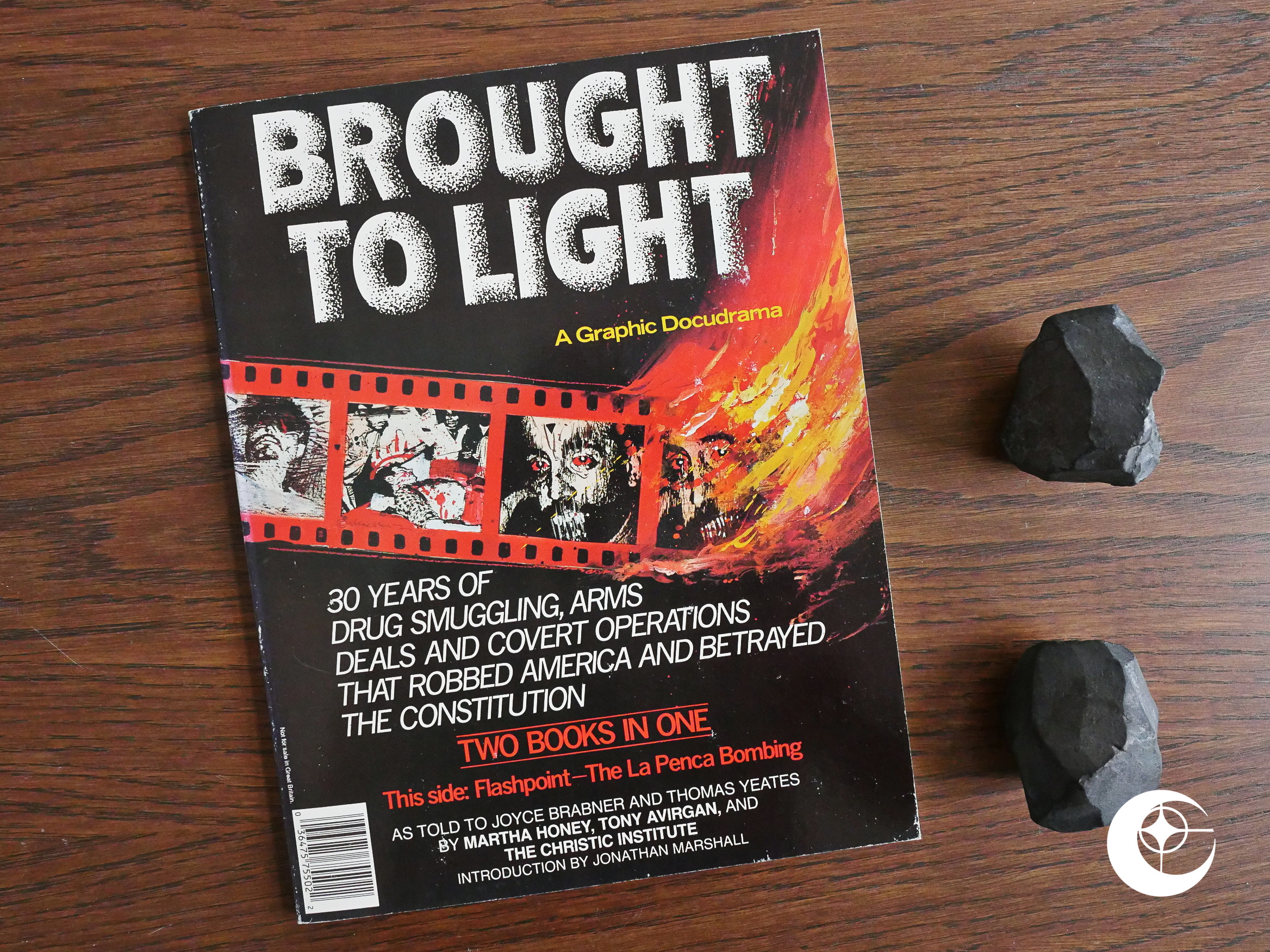

Brought to Light (1989) #1 by Joyce Brabner and Thomas Yeates, Alan Moore and Bill Sienkiewicz, Paul Mavrides et al.

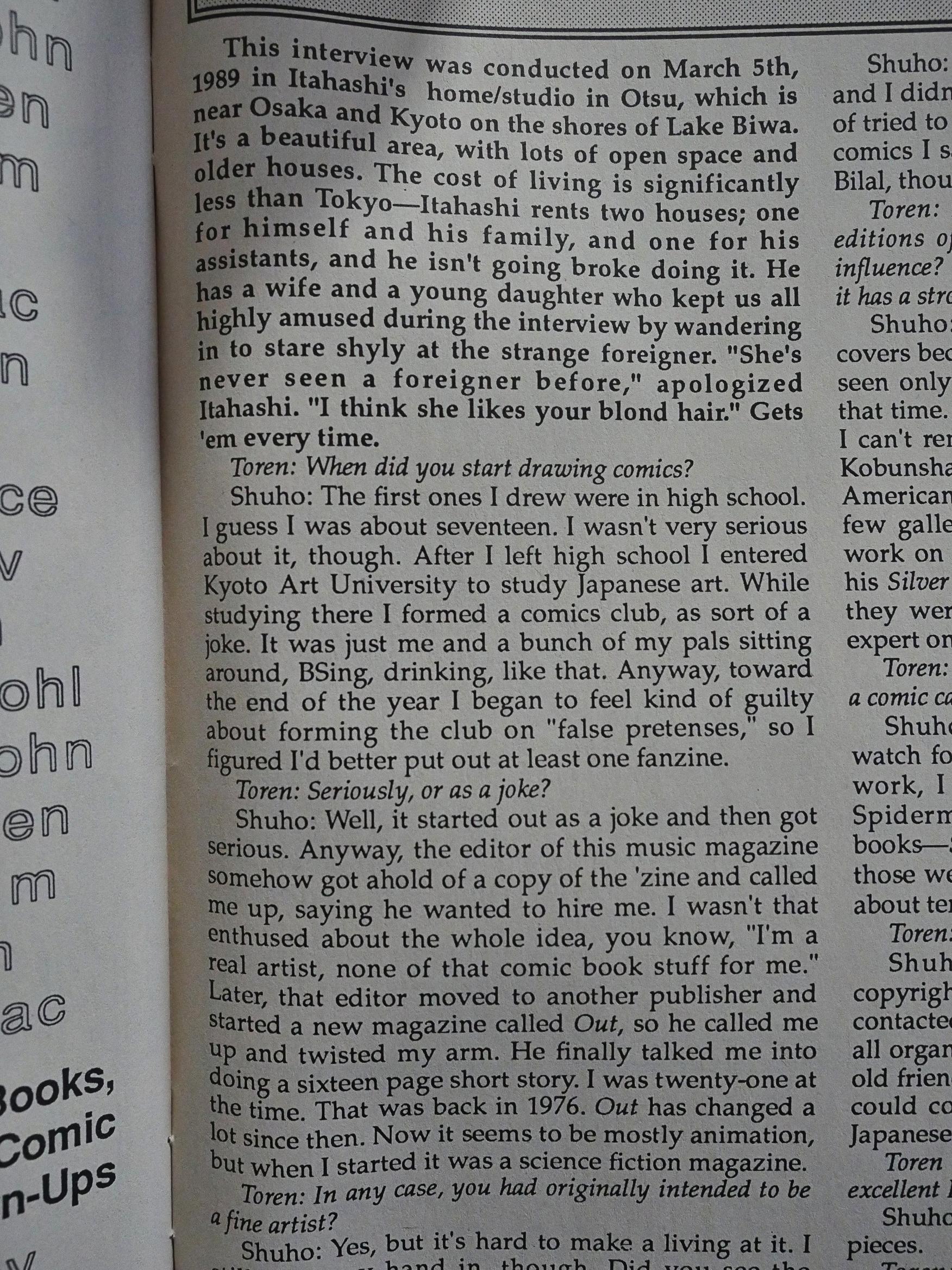

This is part of Eclipse’s “current affair” series of political journalism comics started with Real War Stories. Editor-in-chief cat ⊕ yronwode wrote in an Airboy letters column (and I’m paraphrasing) that it seemed less important to do yet another action/adventure comic about child pornography and drug running when they had an opportunity to do relevant comics that even got taken seriously by real, non-comics journalists, and later wrote this editorial in the December 1988 comics about the experience.

OK, that may sound like I think yronwode was more cynical than she probably was: I think doing these political comics was a heartfelt project. They probably didn’t bring in huge amounts of cash, I have to believe.

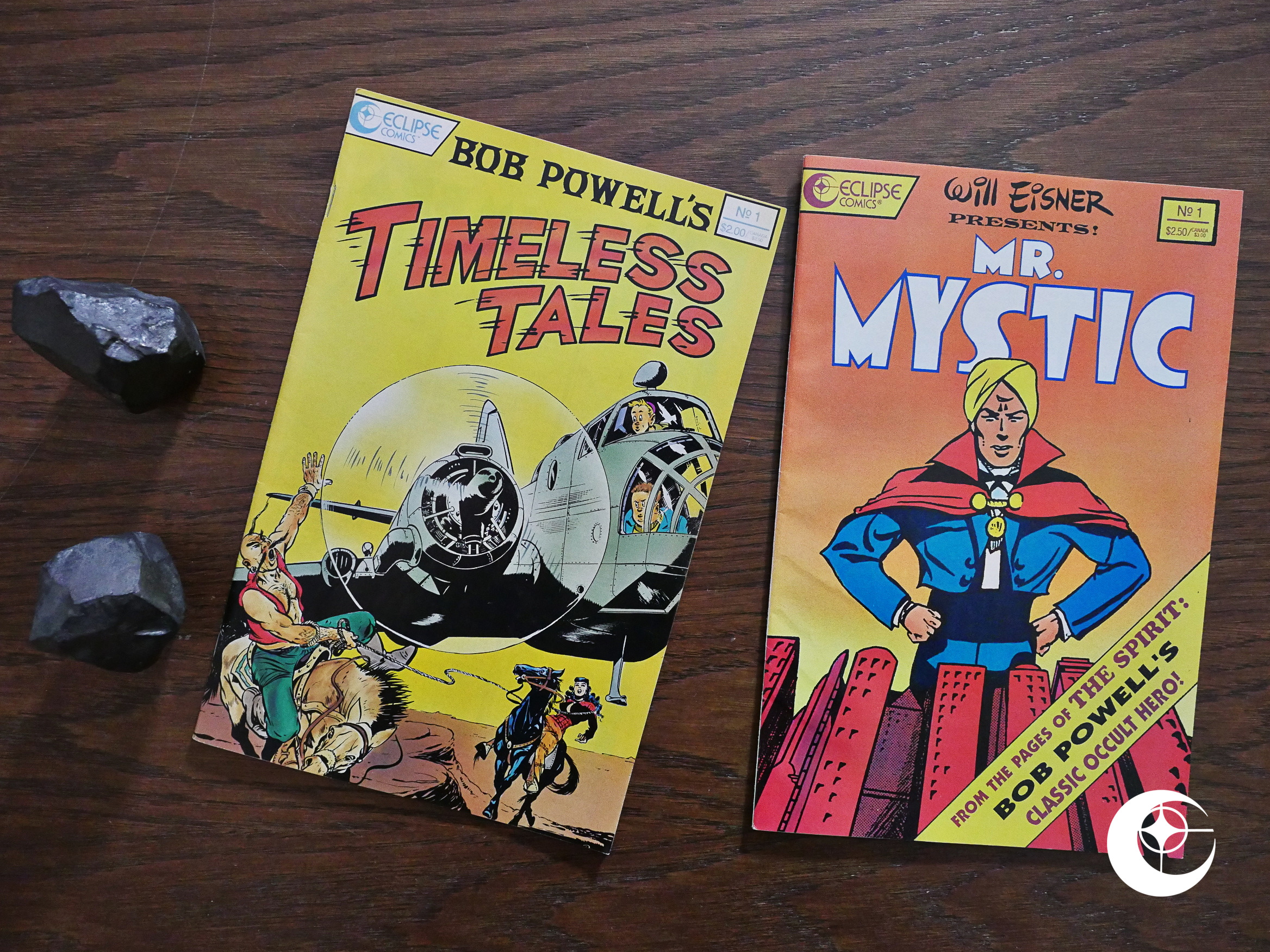

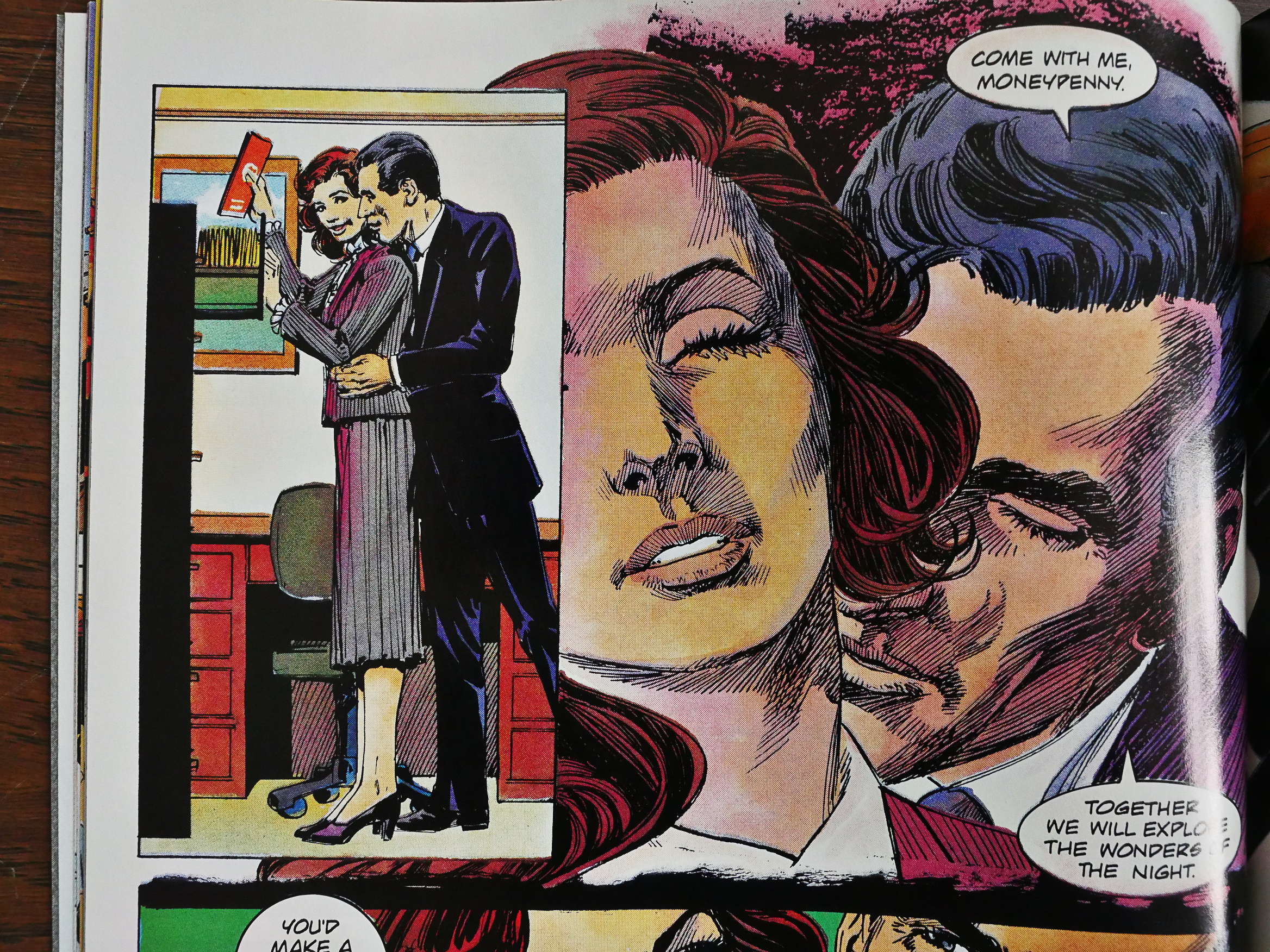

This is probably the most famous of these comics, and mostly because half of it’s by Alan Moore and Bill Sienkiewicz, two of the biggest names in comics at the time.

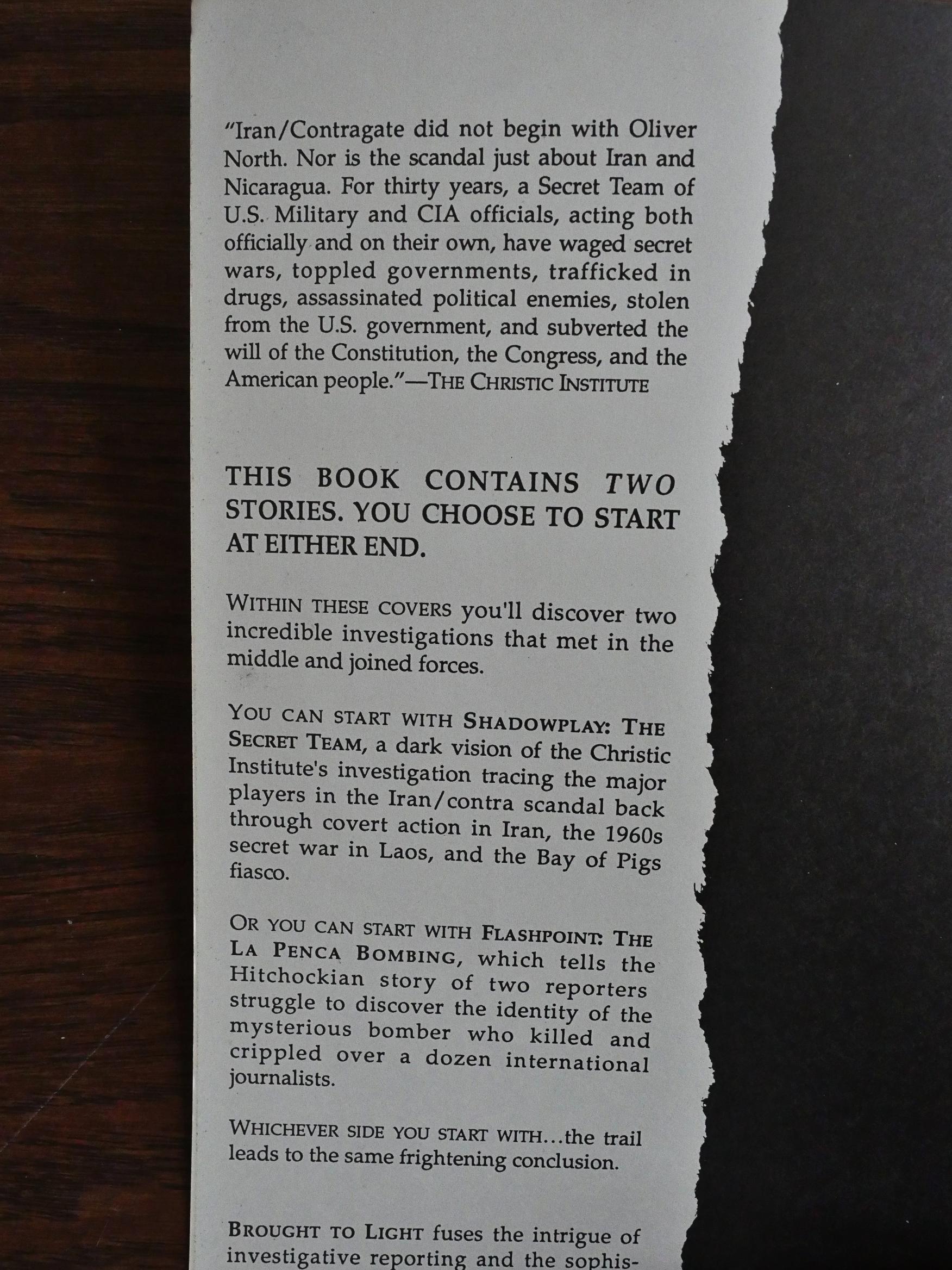

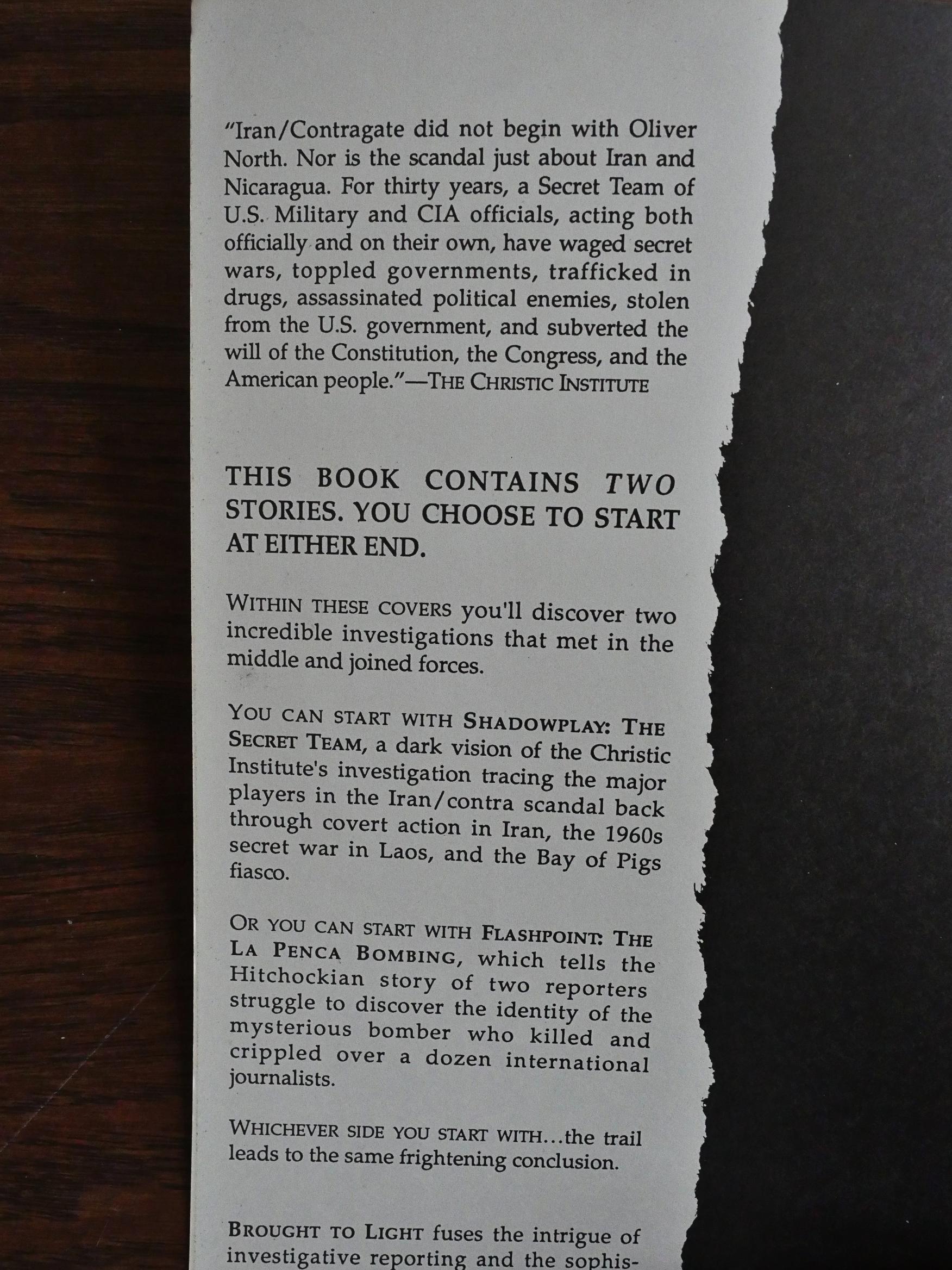

As the introduction explains, this album sized graphic novel has two covers; you just flip the book over to start at the other end. Both are 30 pages long, but they’re very different. The introduction suggests that you can start at either end, so I started at the Brabner/Yeates side.

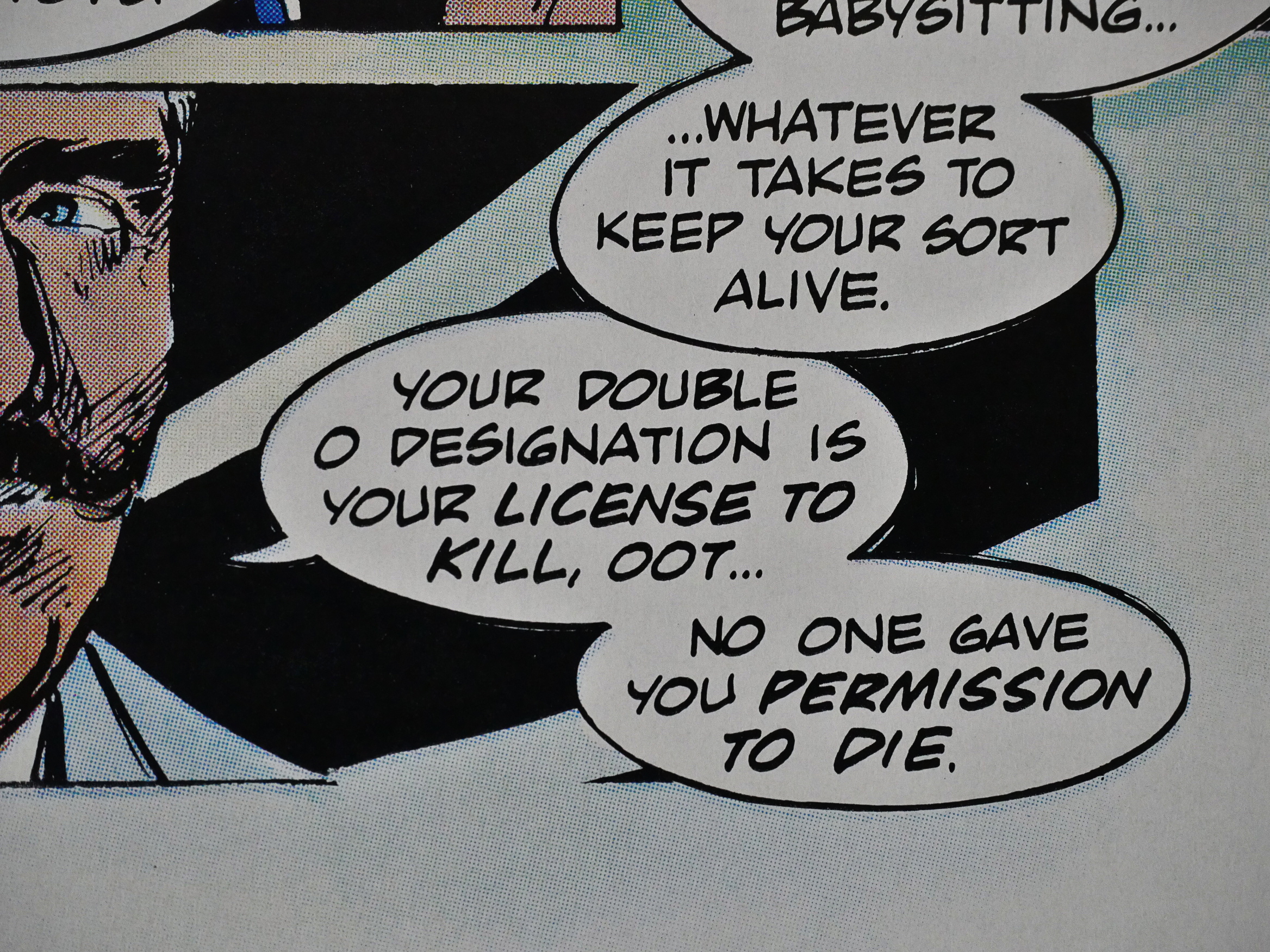

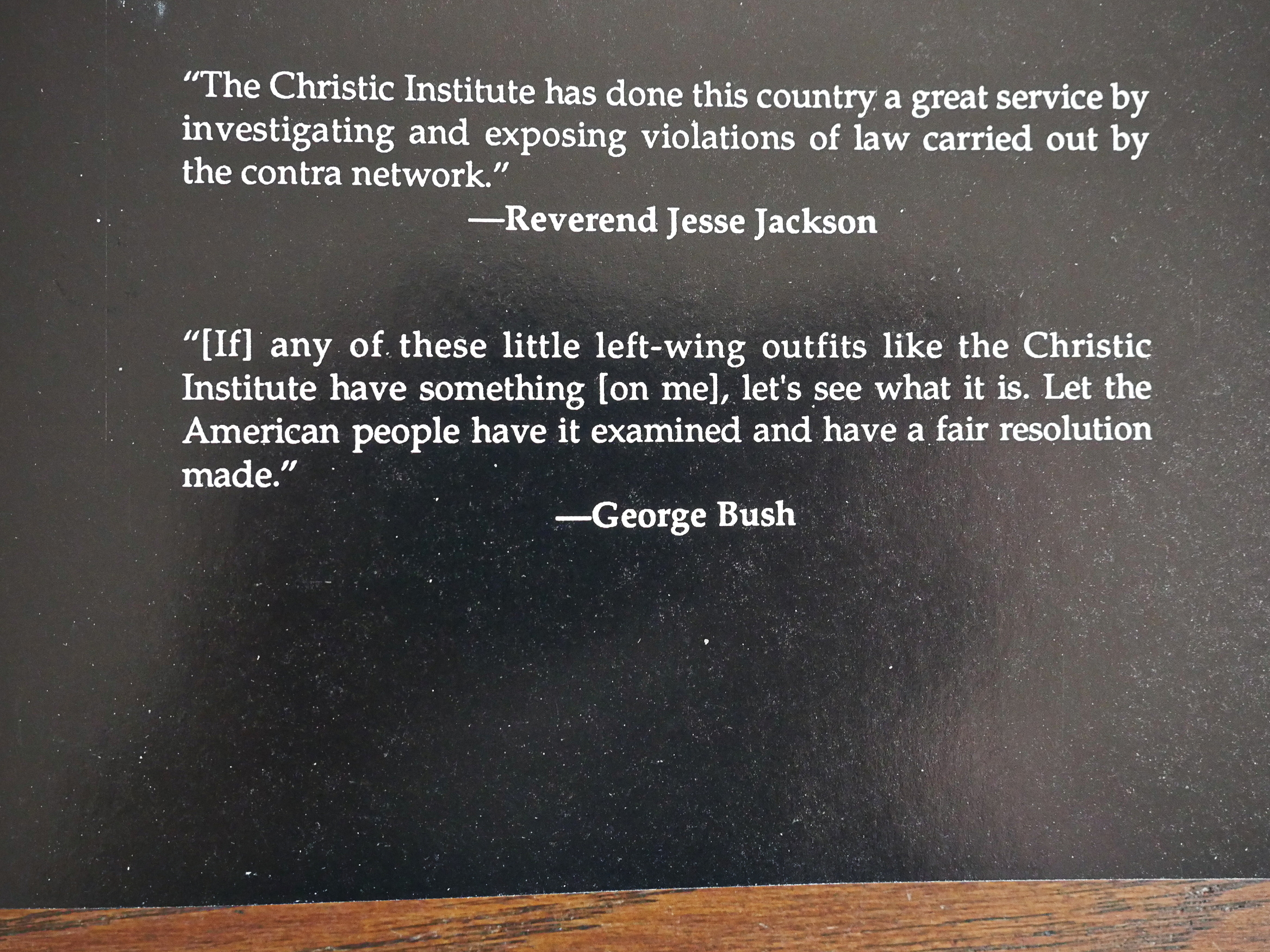

That’s a nice challenge from George Bush.

The introduction by Jonathan Marshall goes to great lengths to explain what a novelty it is that a comic book exists that’s not for kids or trash for semi-literate adults. Nice to know.

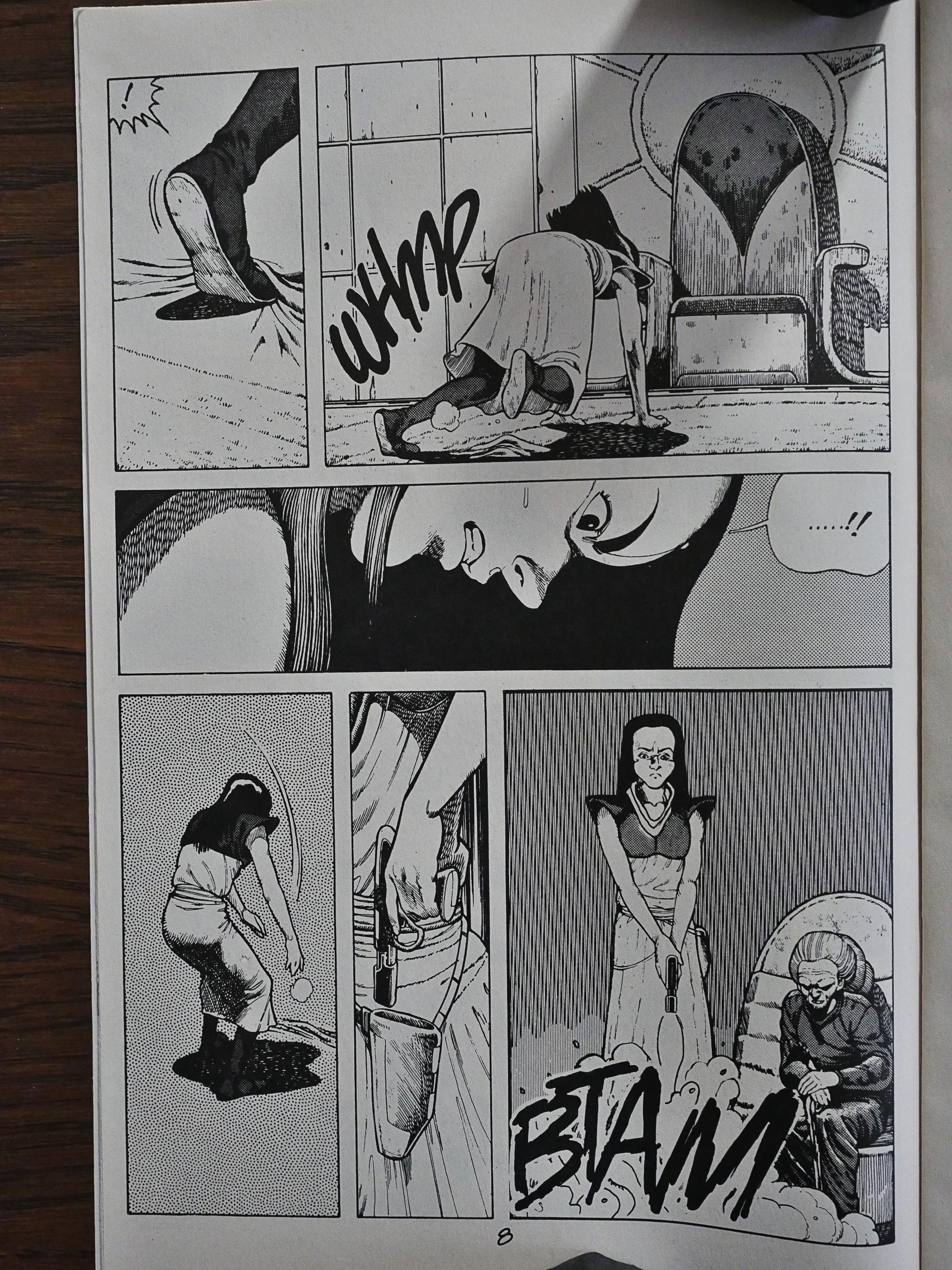

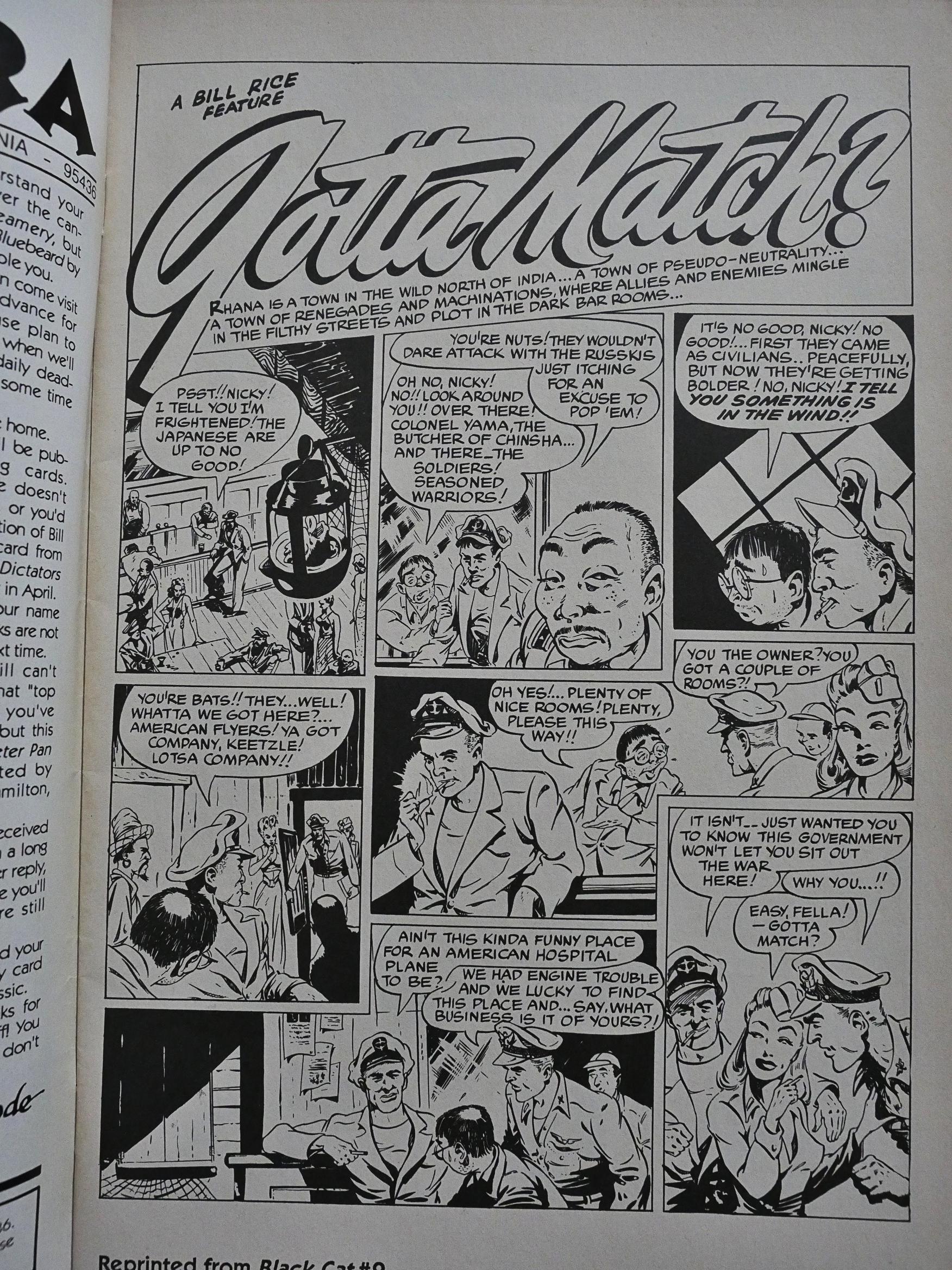

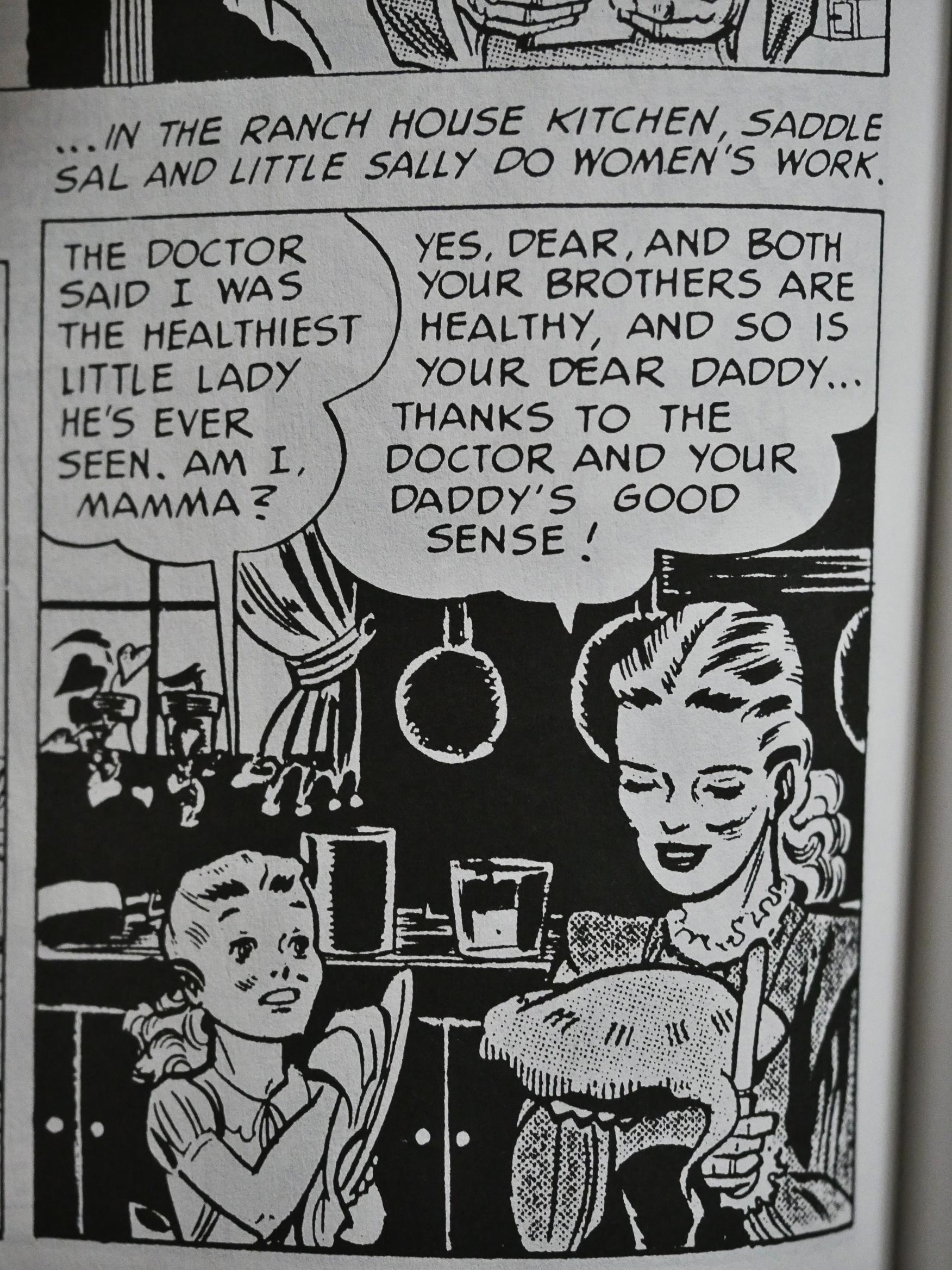

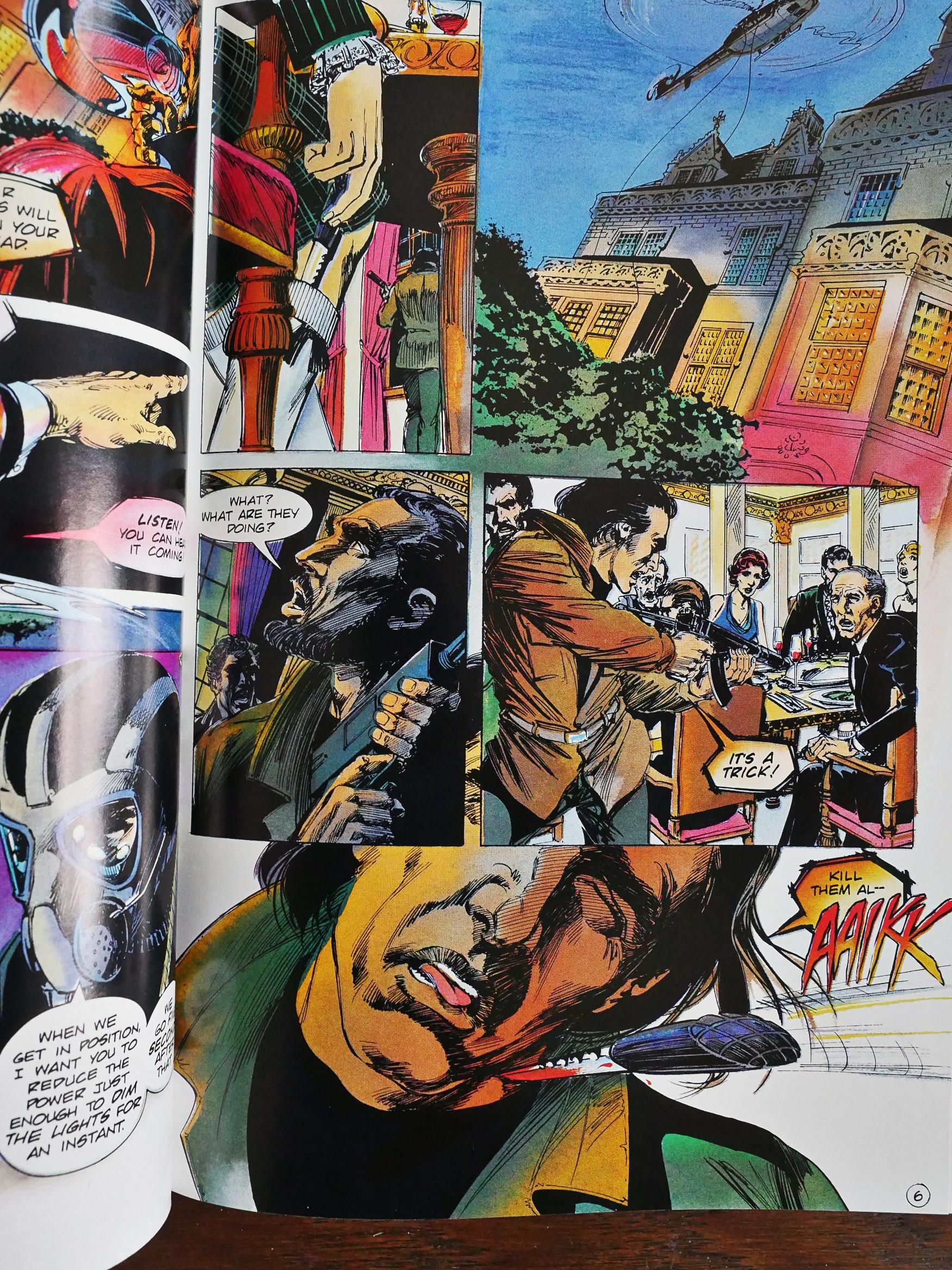

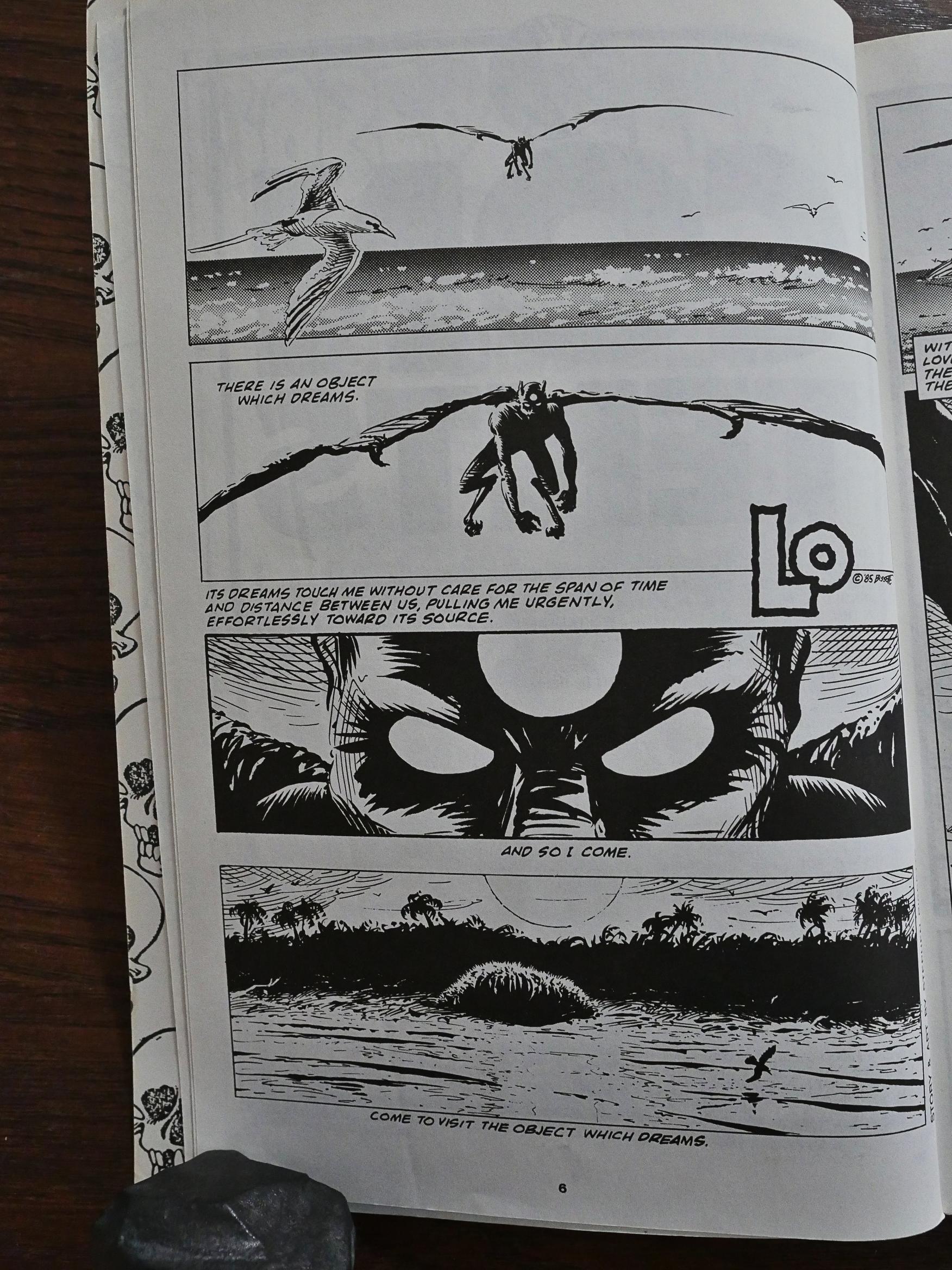

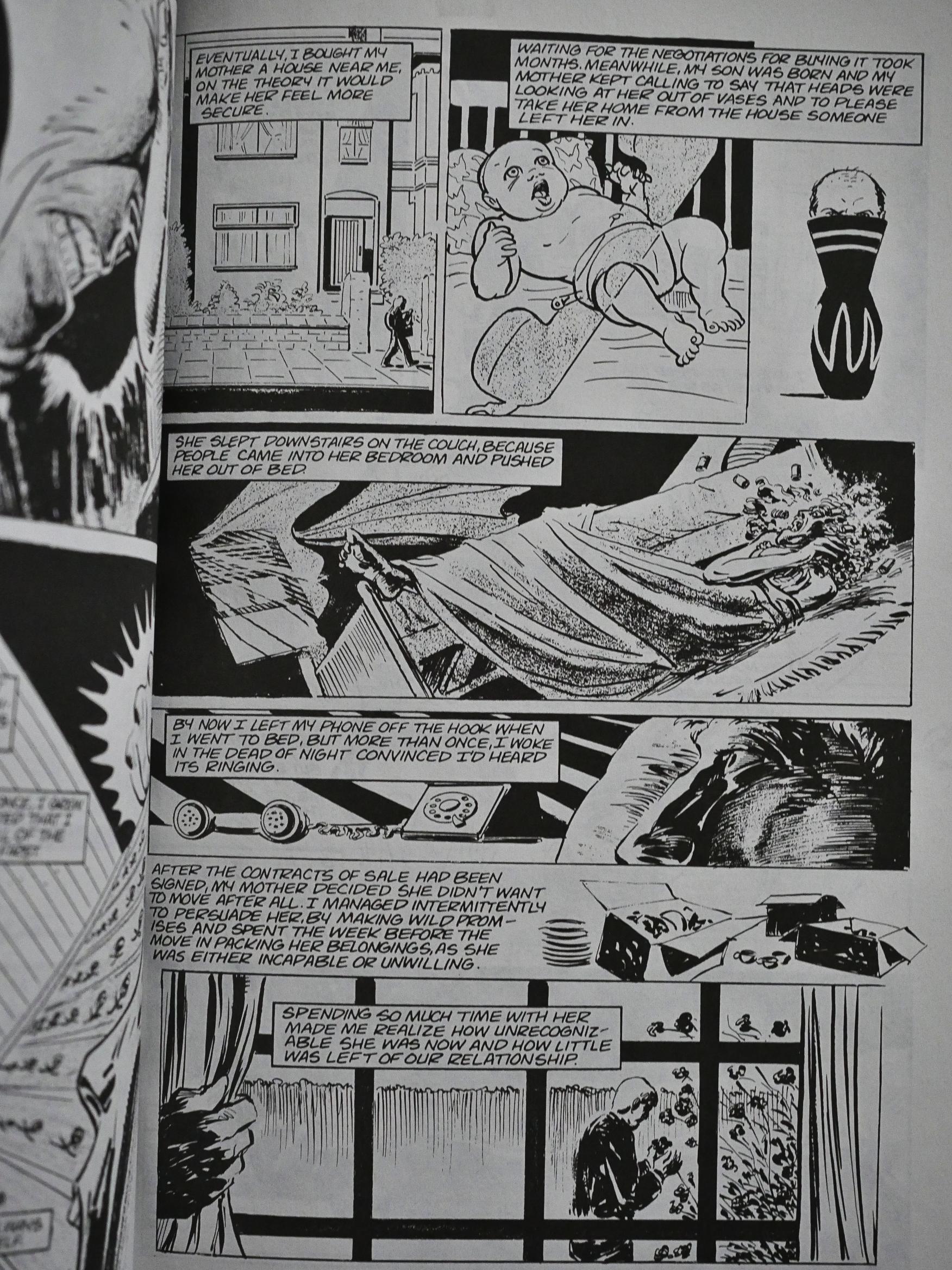

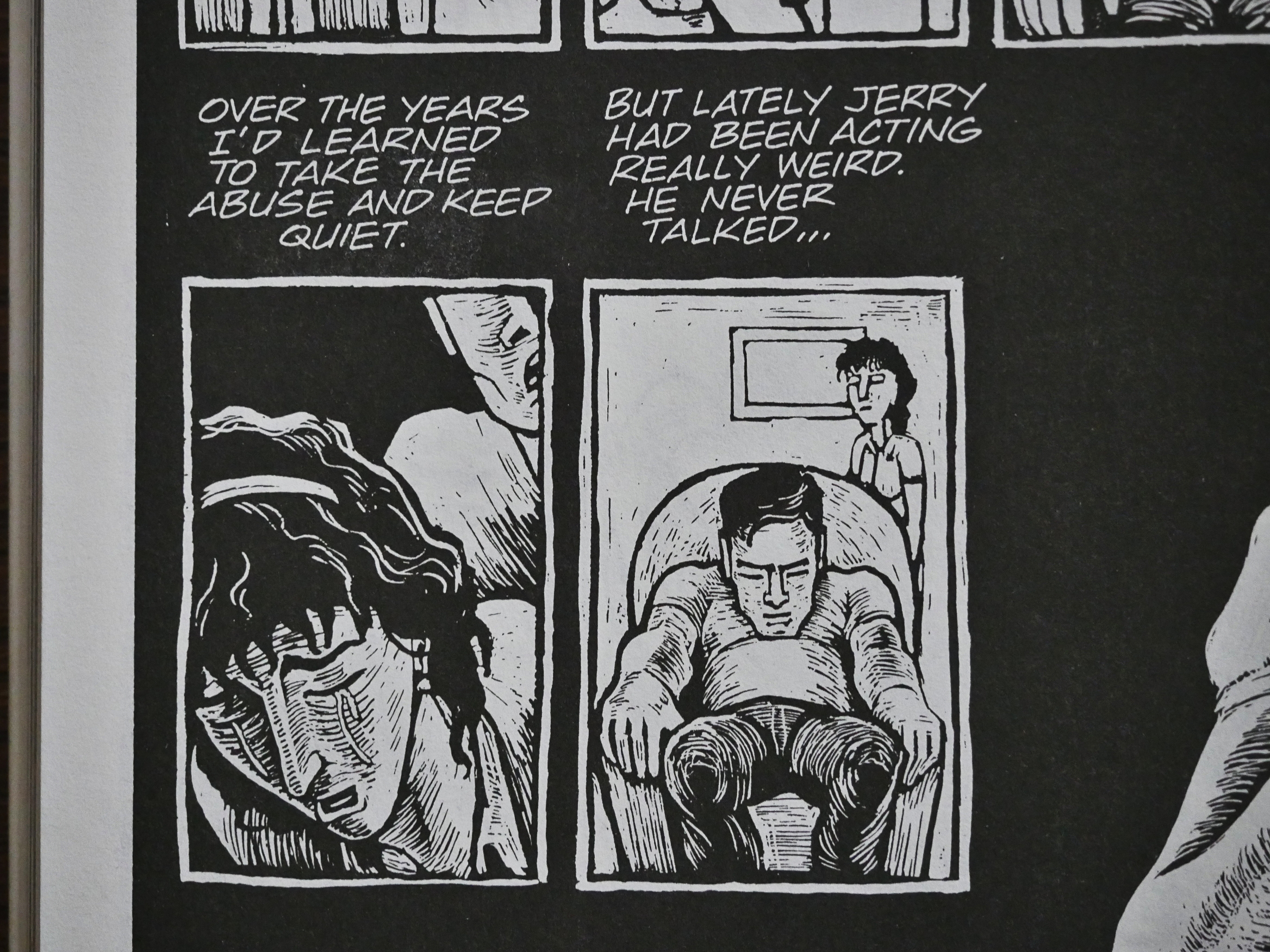

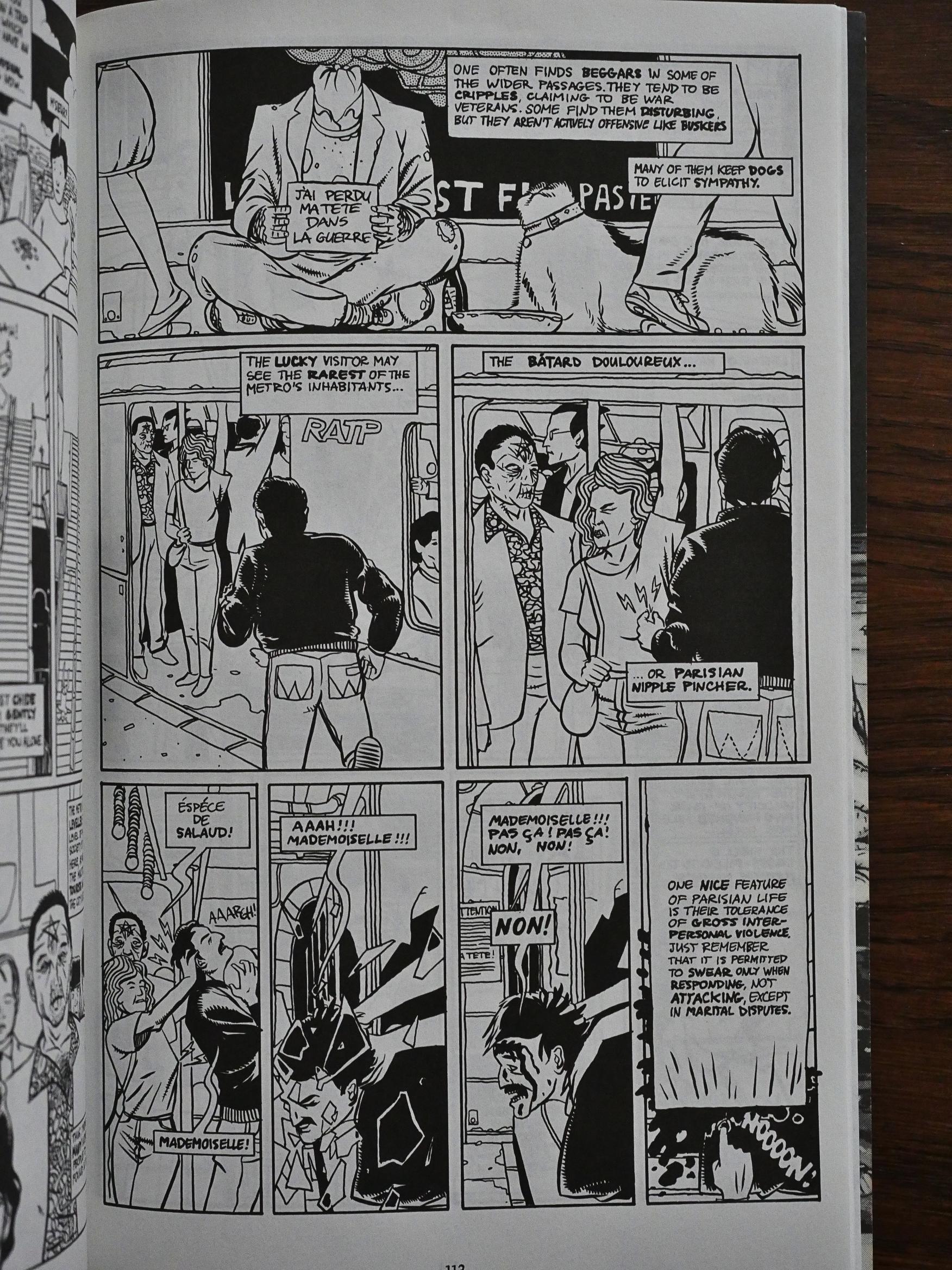

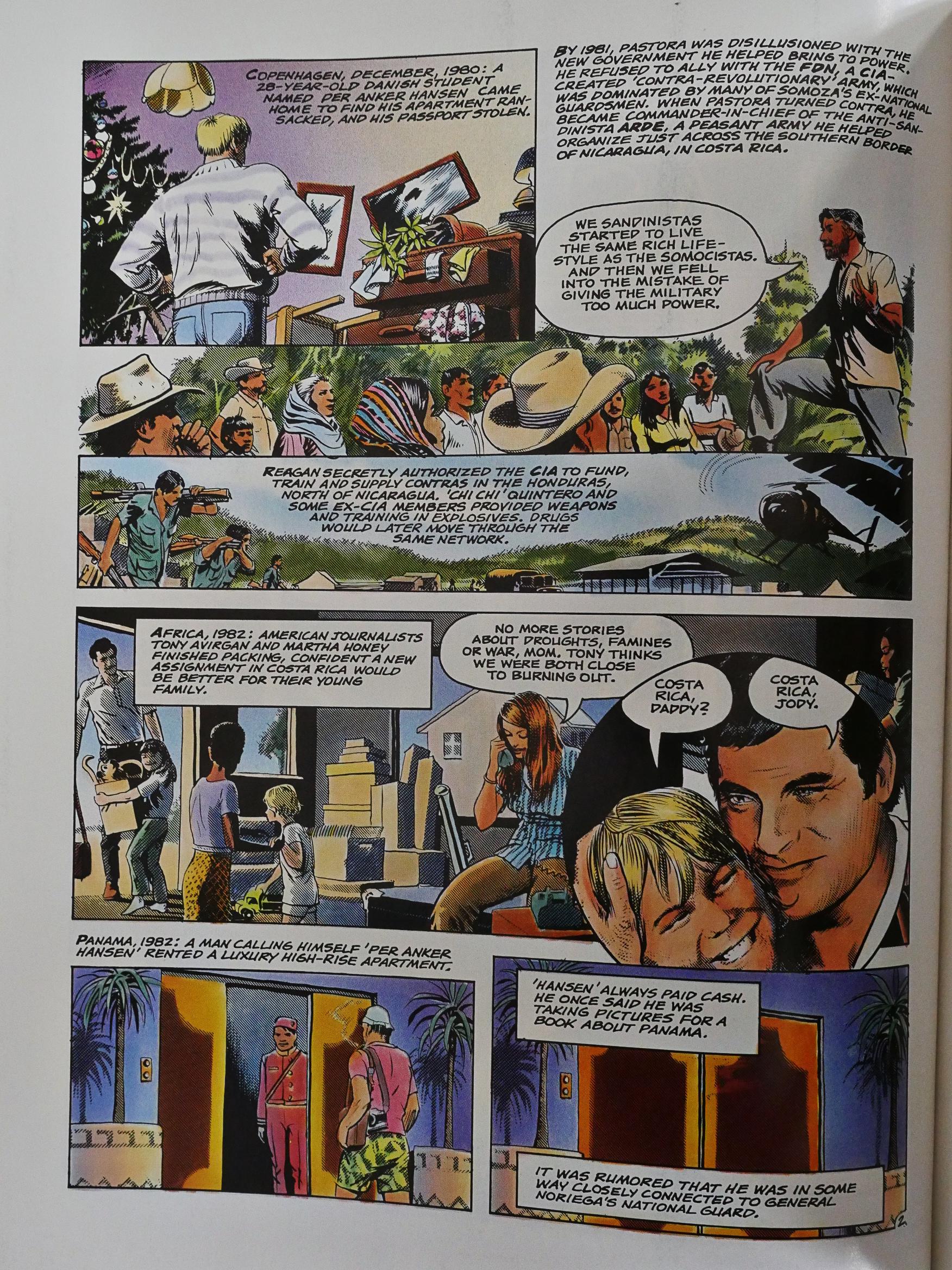

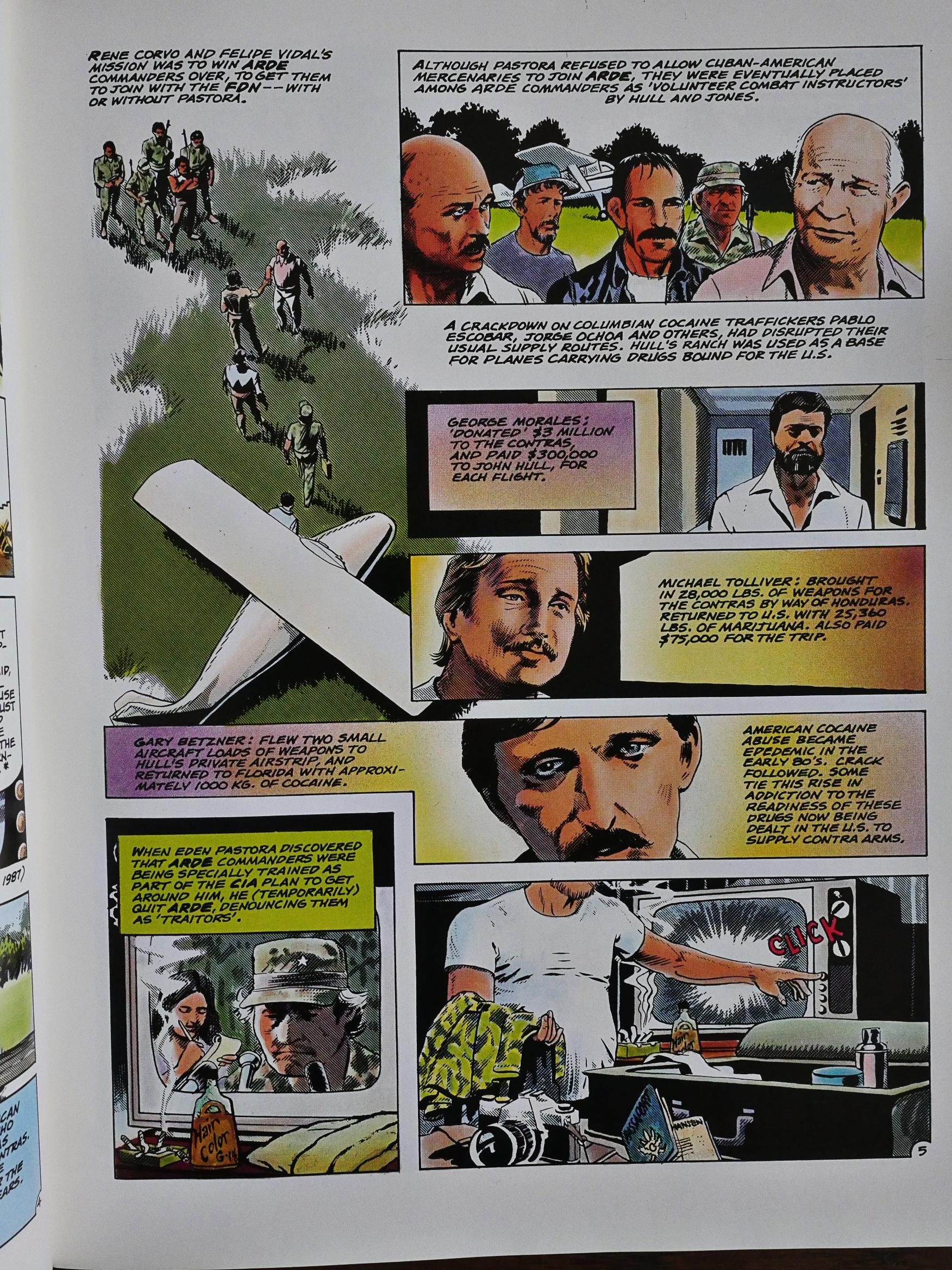

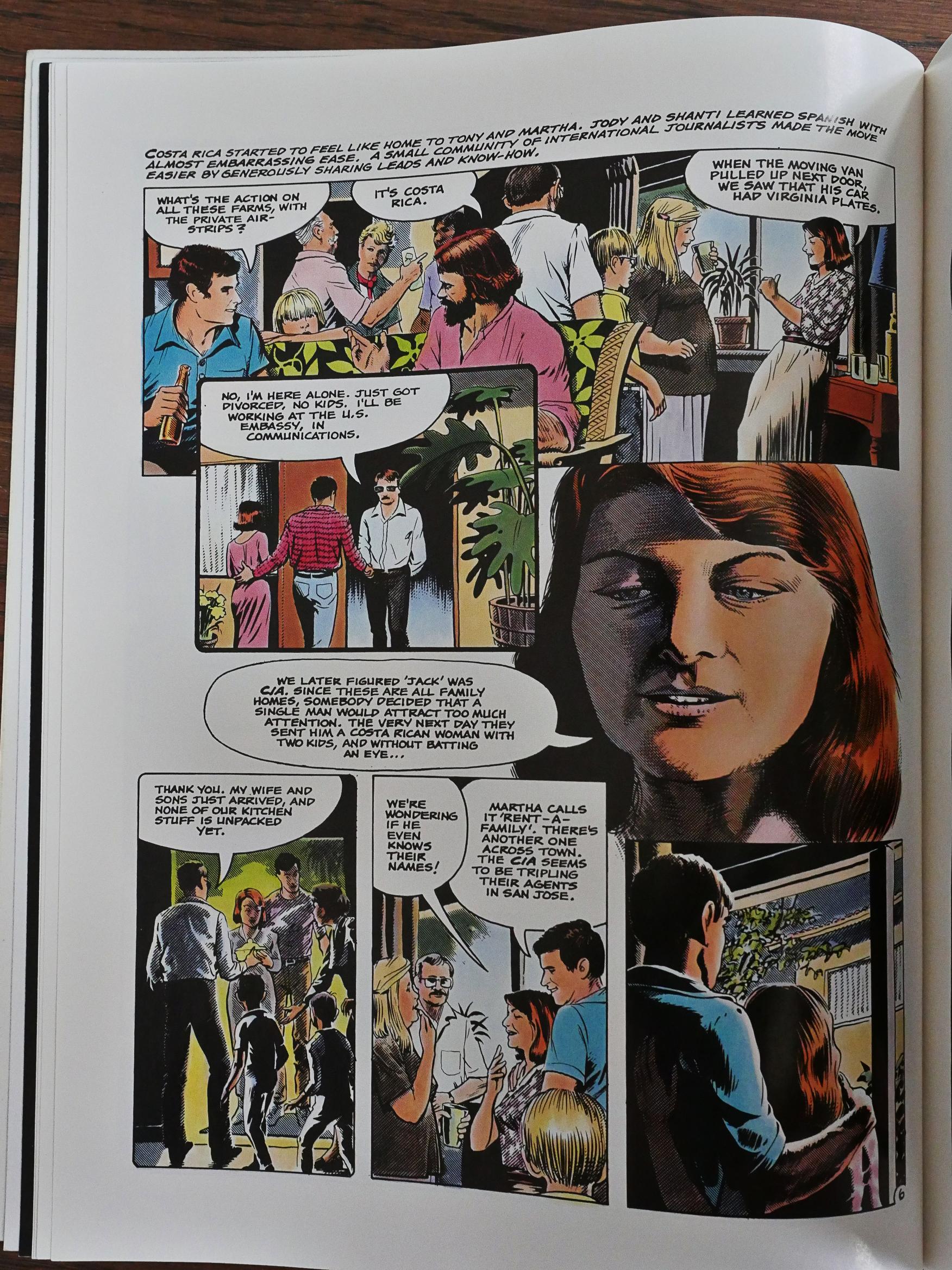

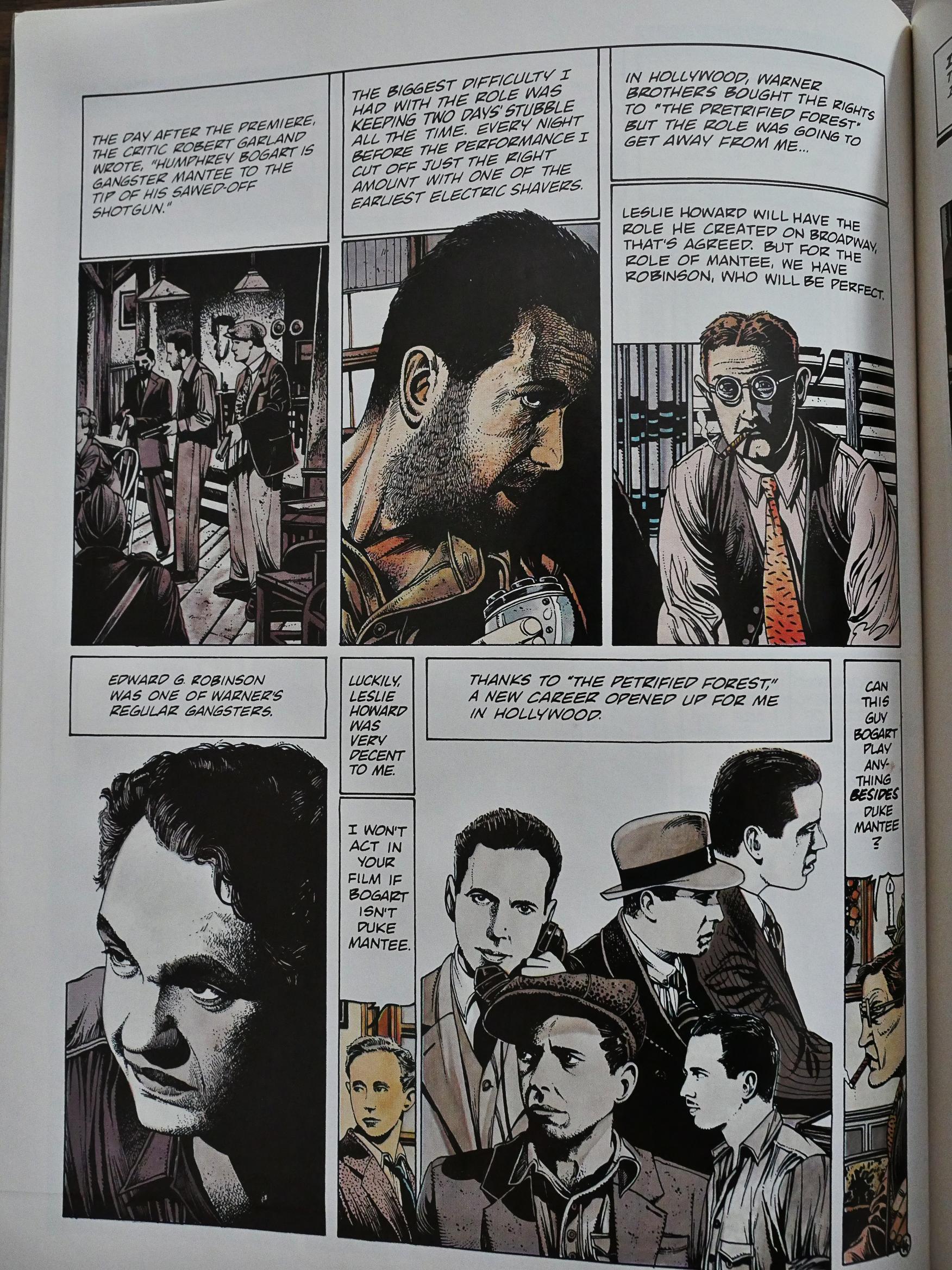

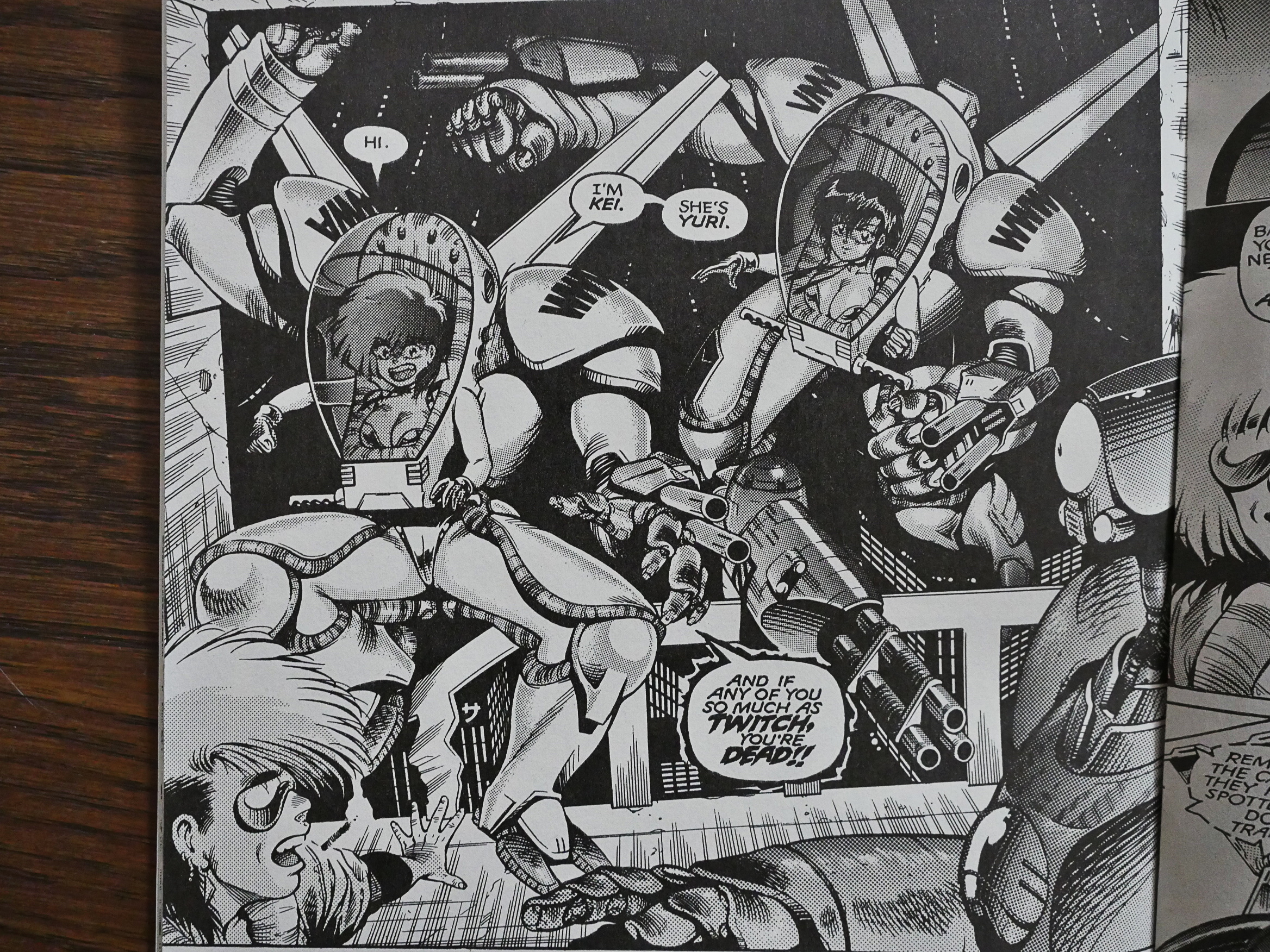

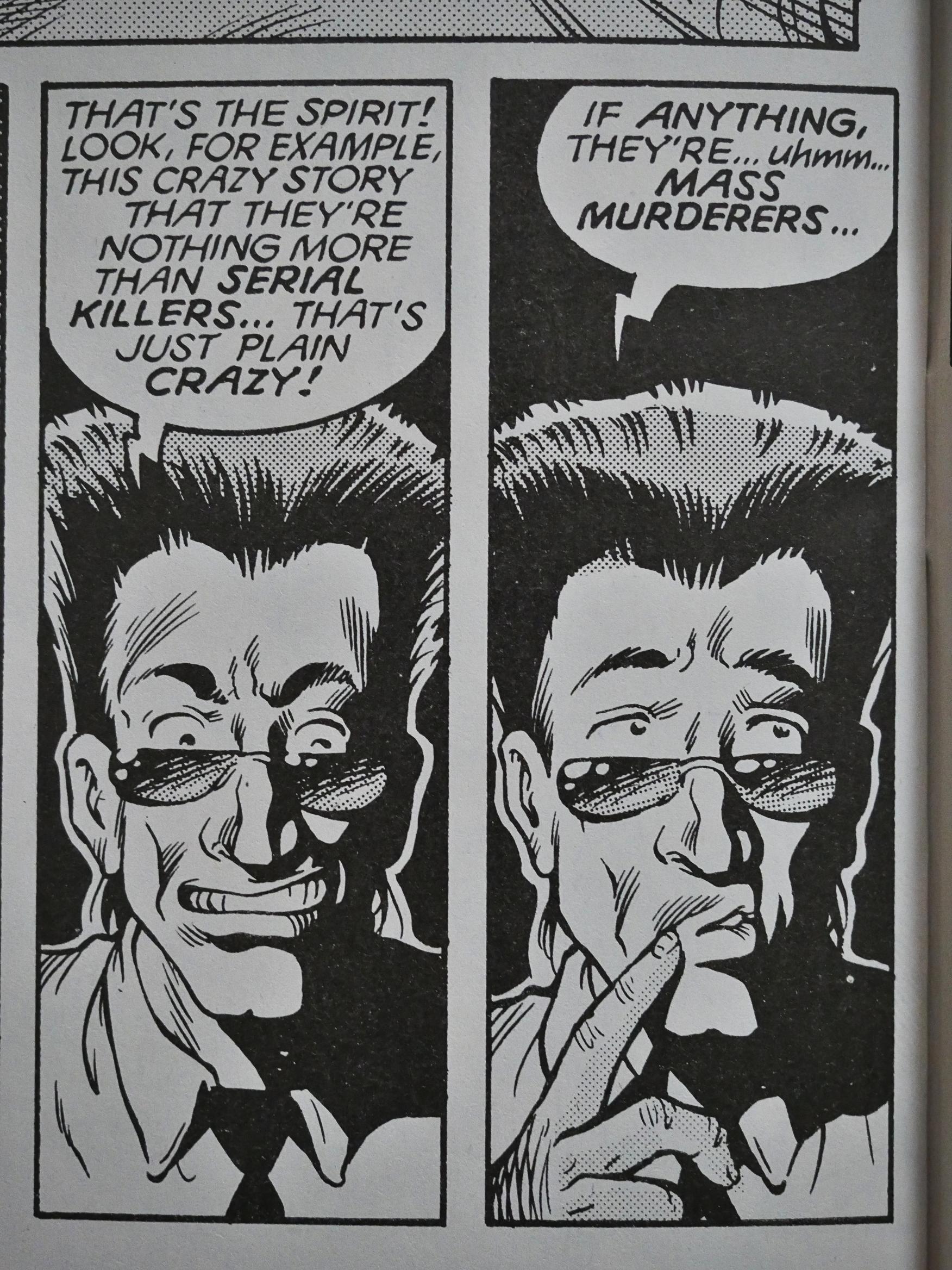

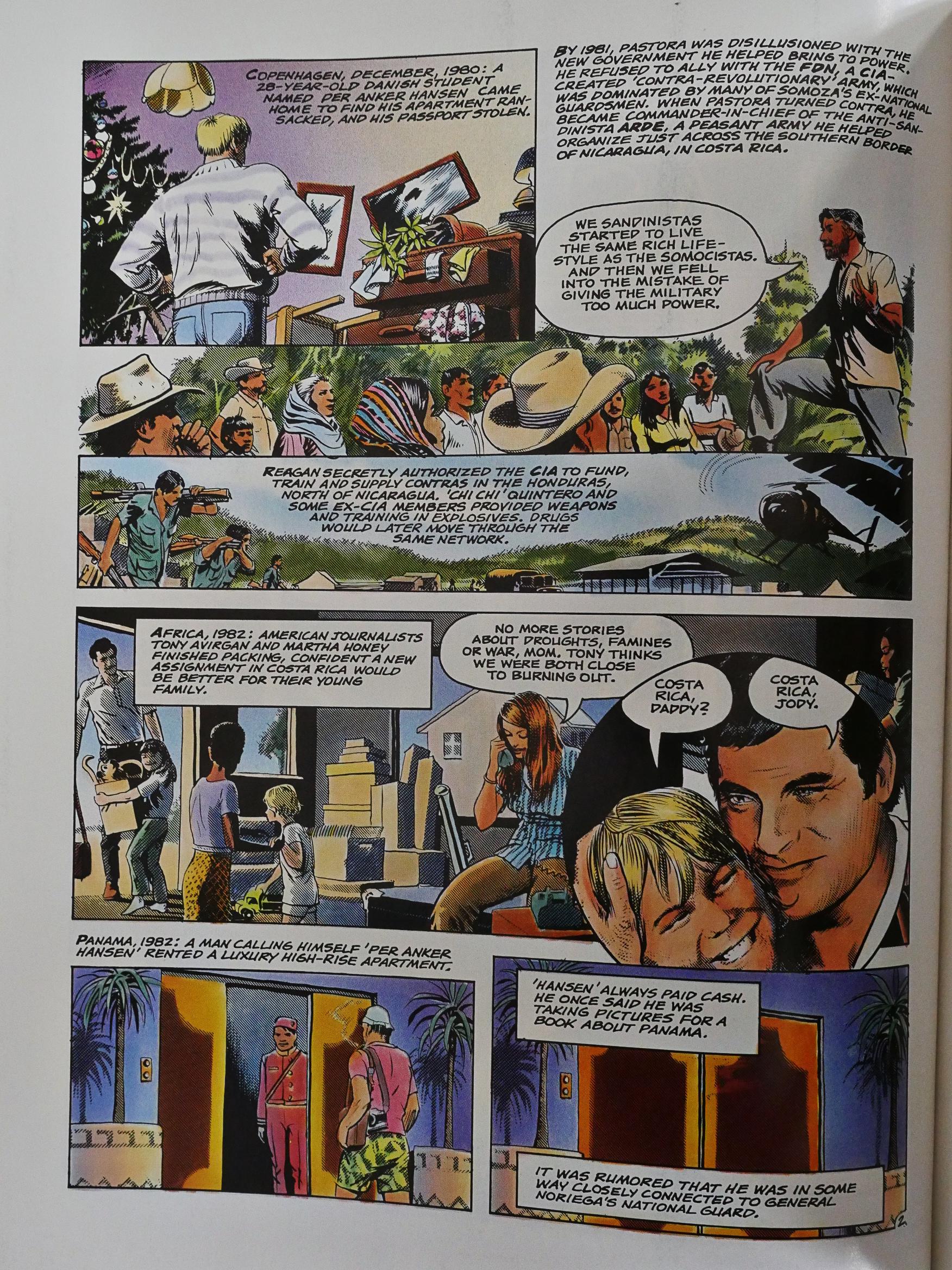

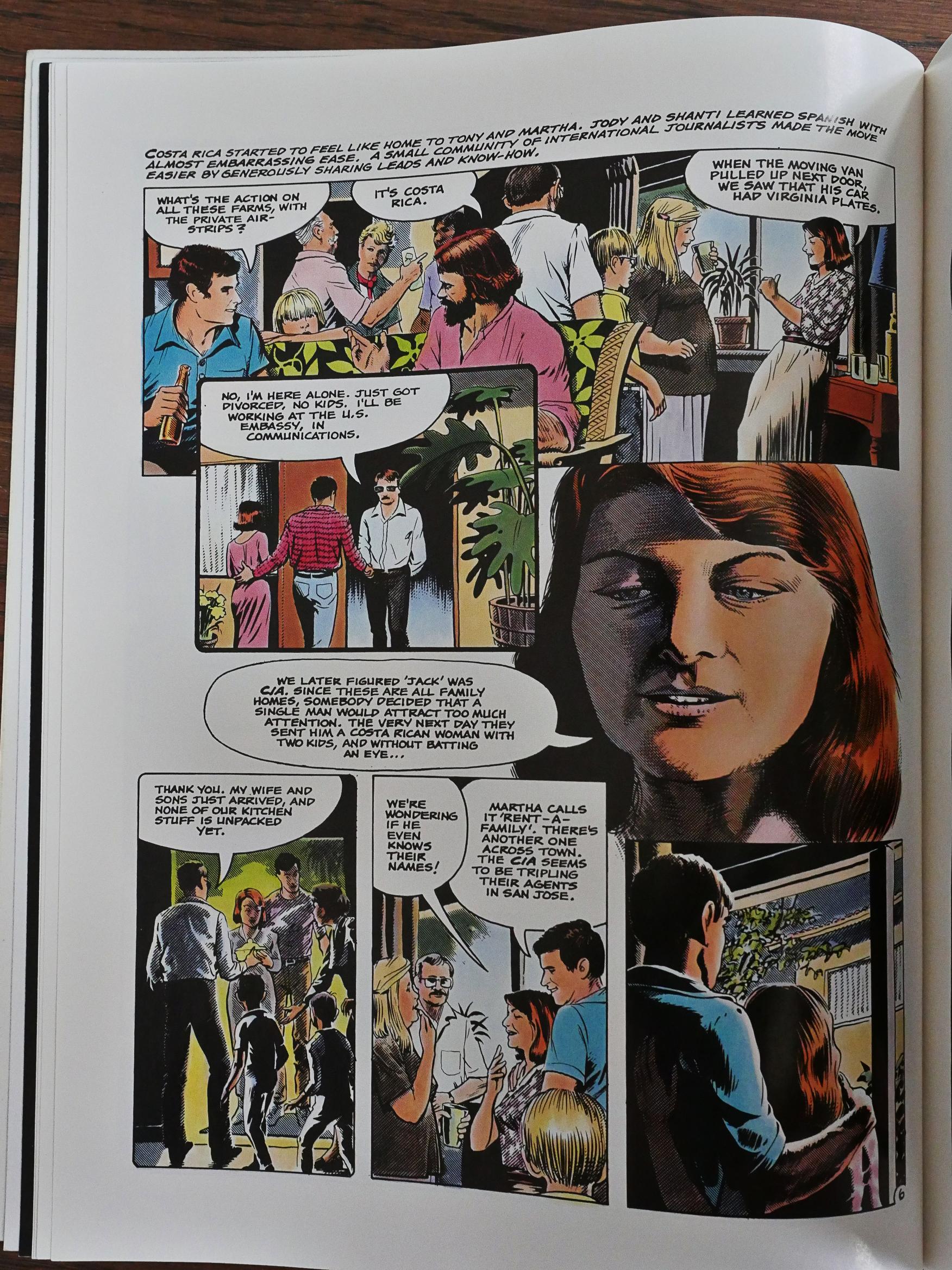

And it’s pretty clear who the Brabner/Joyce piece is for. If you’ve ever seen a two hour American TV documentary, you’ll be able to follow along perfectly, because it’s told without any comic book storytelling techniques, really. You have a narrator (probably a very deep, serious, male one) doing the voice-over, explaining everything to you, and then you have rapid, rapid edits that gives you a sentence or two of sound bites from people, and it’s a mixture of re-enactments and people telling us the story.

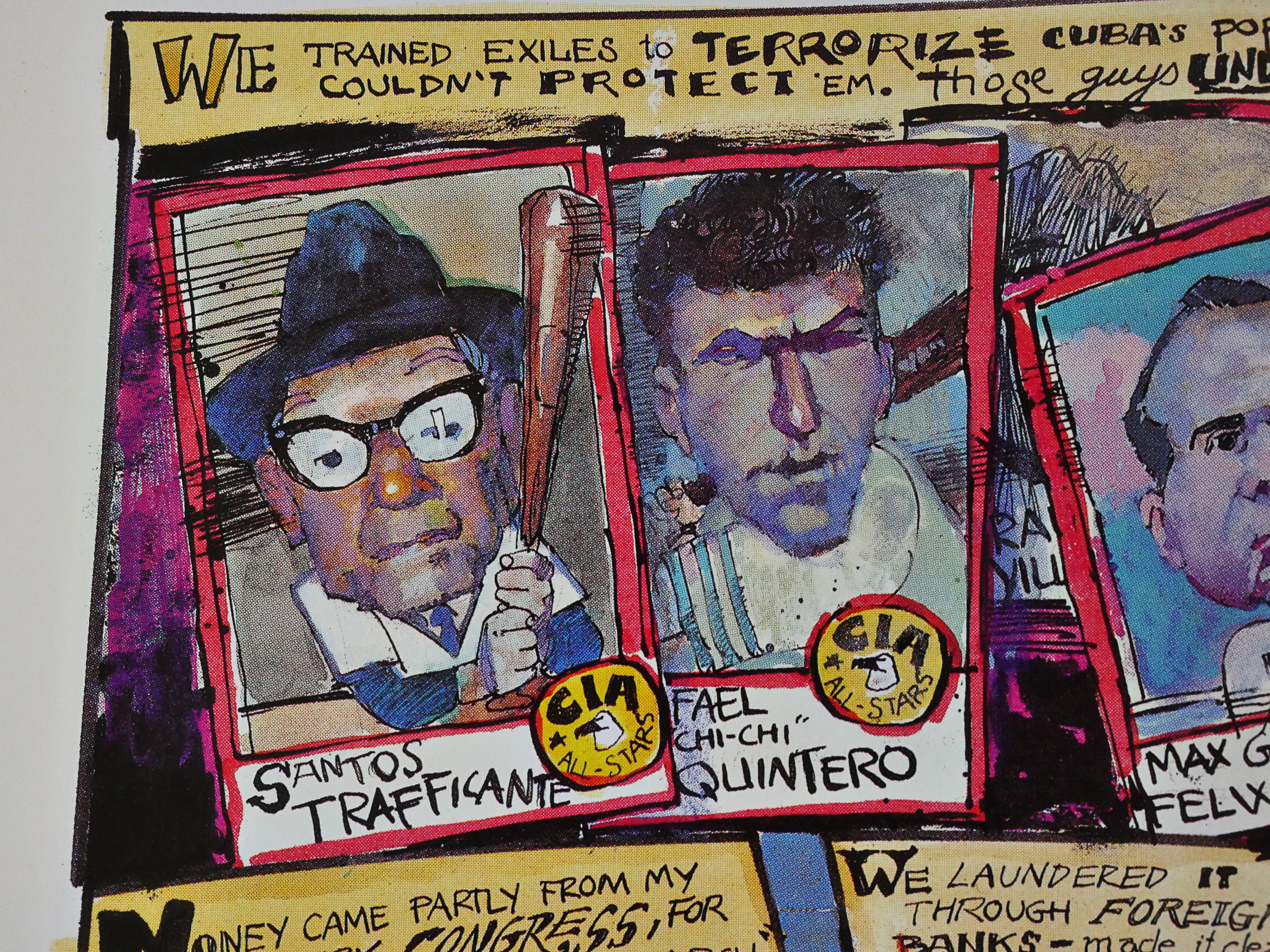

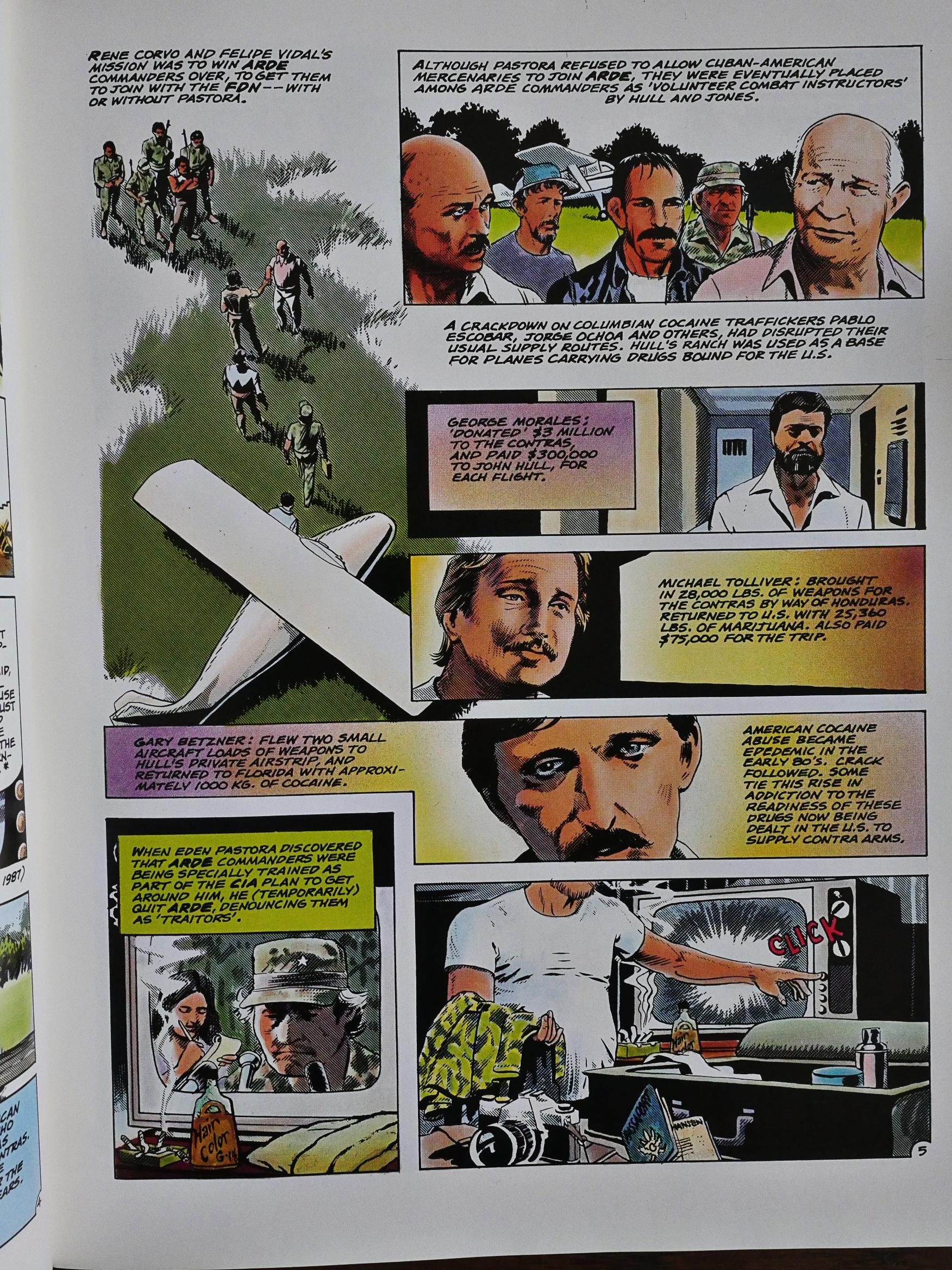

And it’s a story of the CIA planning to kill an independent Contra leader and blaming the Sandinistas for the murder. Instead it goes slightly wrong, as these CIA operations usually do, and they kill five journalists instead. We also get a lot of information about other (mostly botched) operations they attempted, like killing a US ambassador.

Mostly these pages don’t need to be a comic book at all: They’d work just as well with just the “narrators” text as a newspaper article.

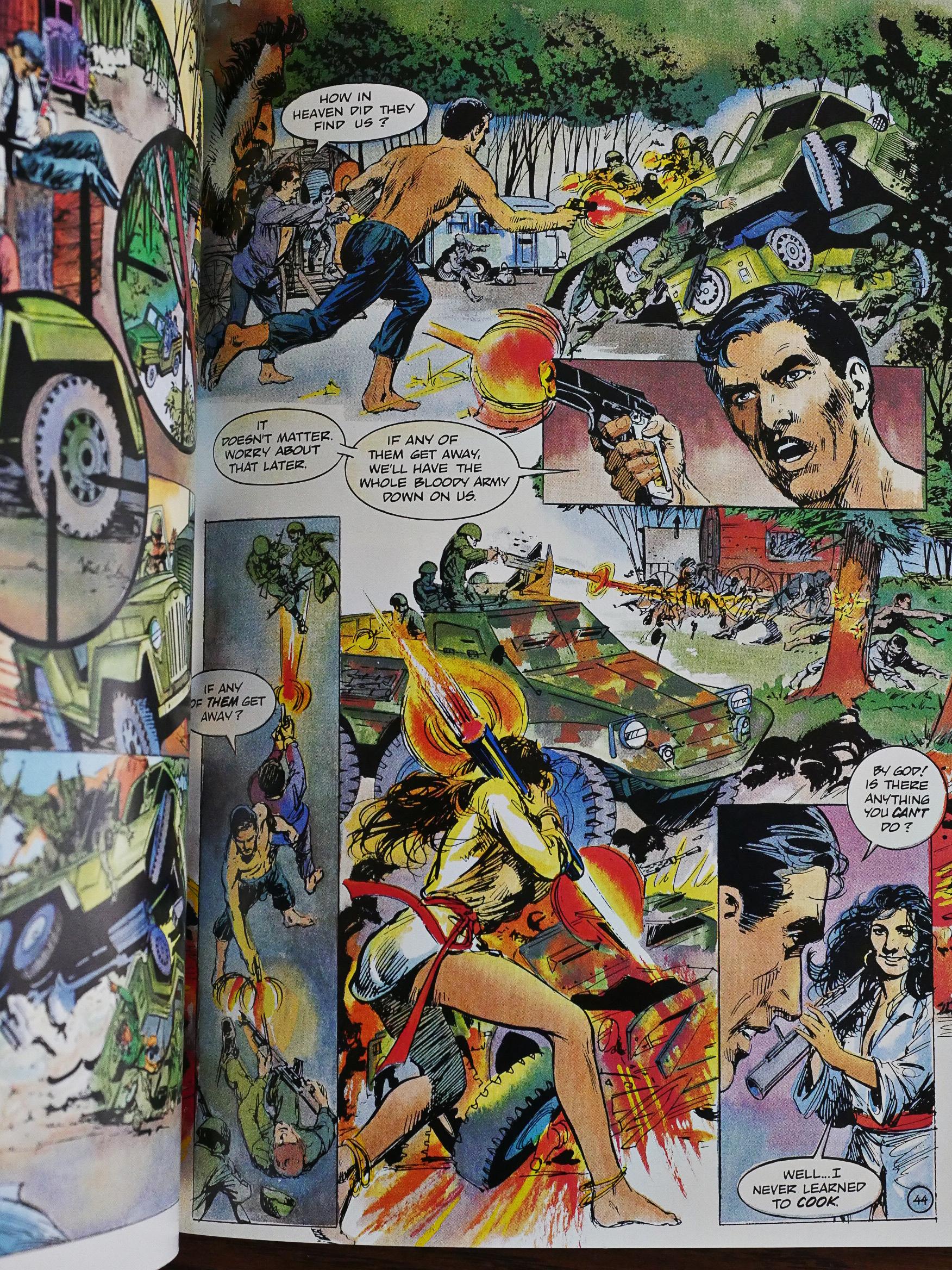

Sometimes, though, they find room to show us the people and have them interact a bit, and it really helps a lot. And it helps in understanding how inept these CIA operations mostly are.

But, on the other hand, since nothing ever happens when they’re found out (even if they have the killers on video), why should they care?

Now, Brabner has most of her information about these proceedings from the Christic Insitute (of Silkwood fame), which I understand has had their reputation somewhat tarnished in later years, so I have no idea how much of this stuff is accurate, but if we’ve learned anything over the last decades, it’s that all the lefty conspiracy theories about the CIA from the 80s have been proved to be true, so…

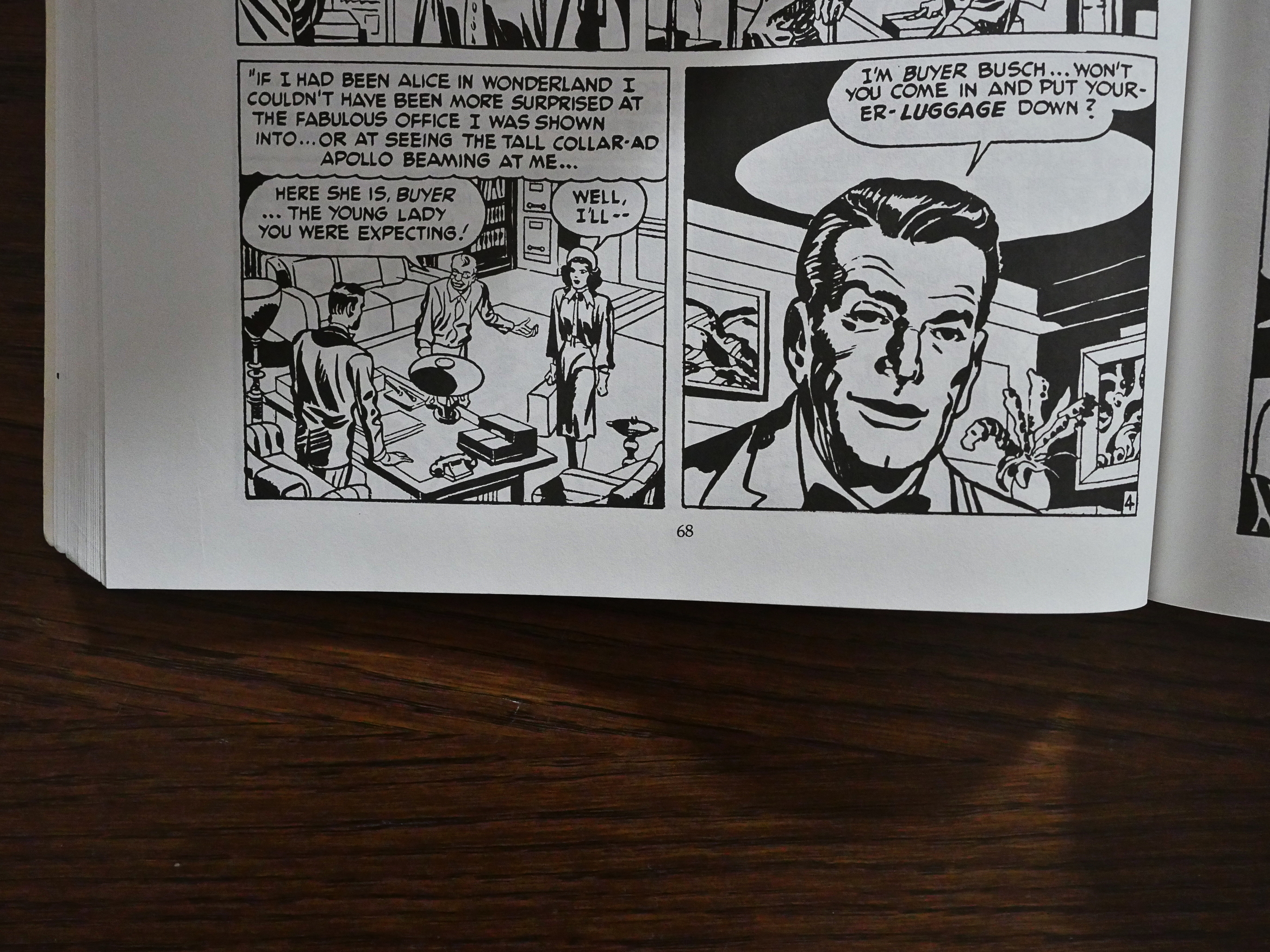

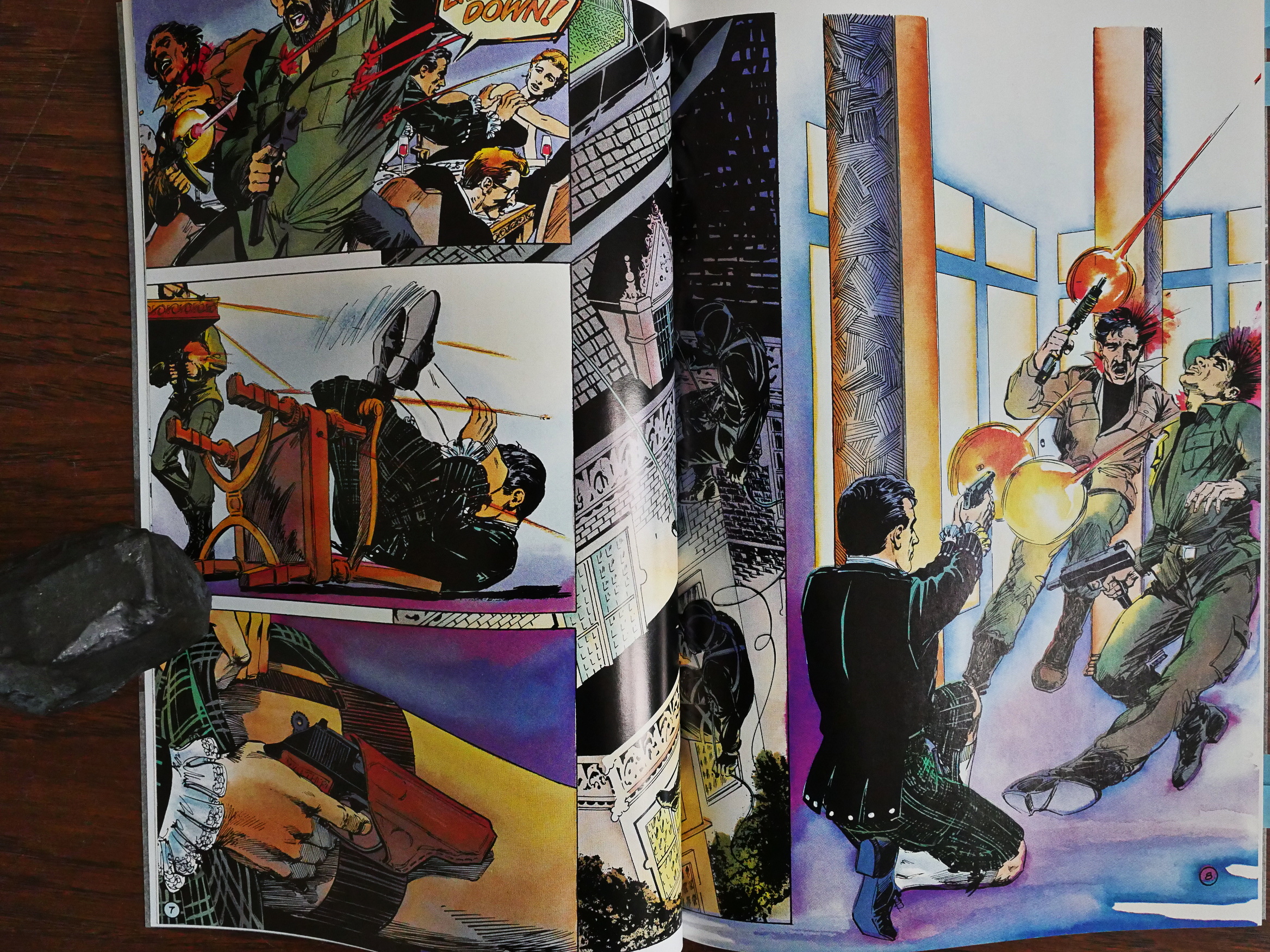

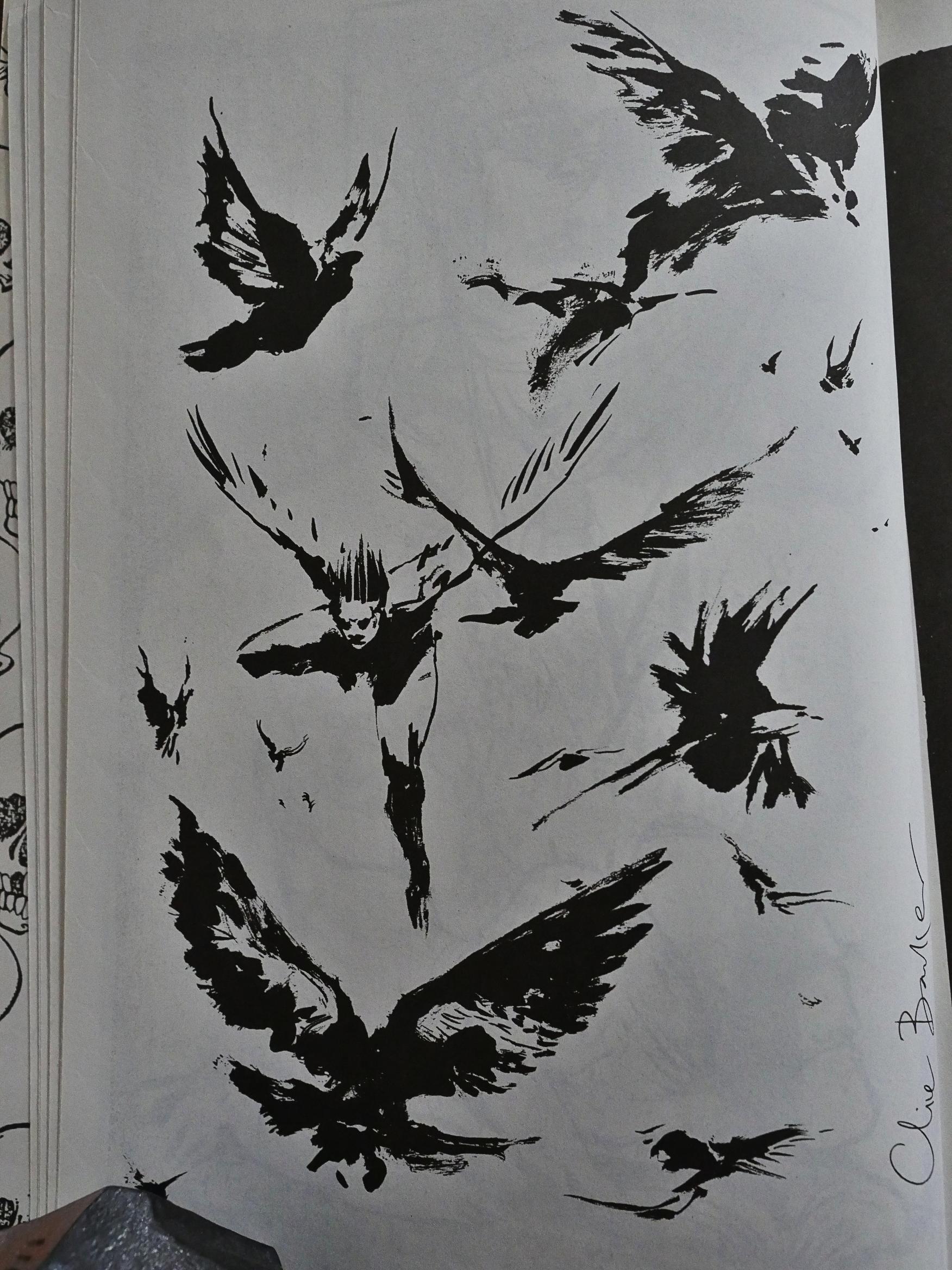

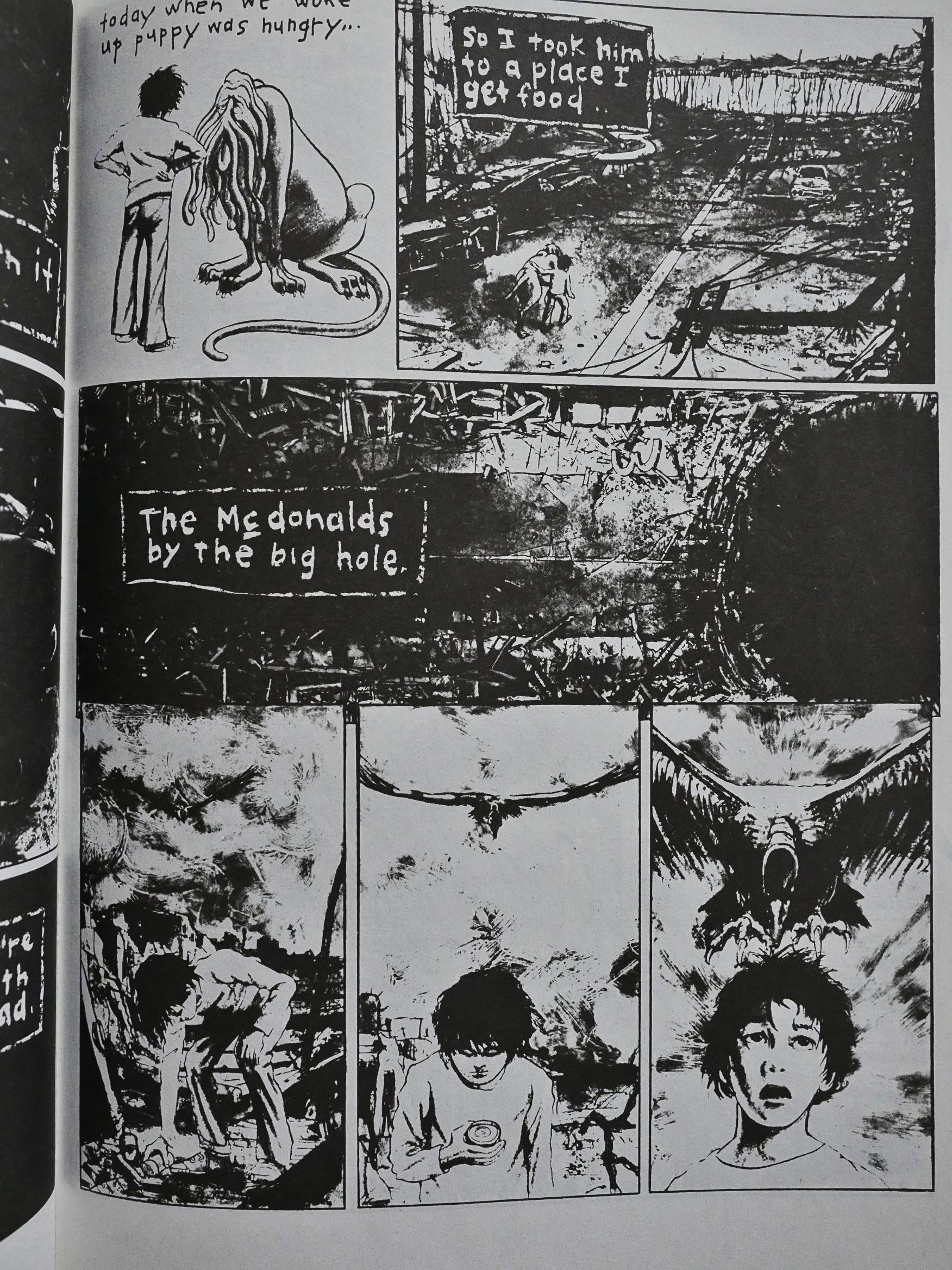

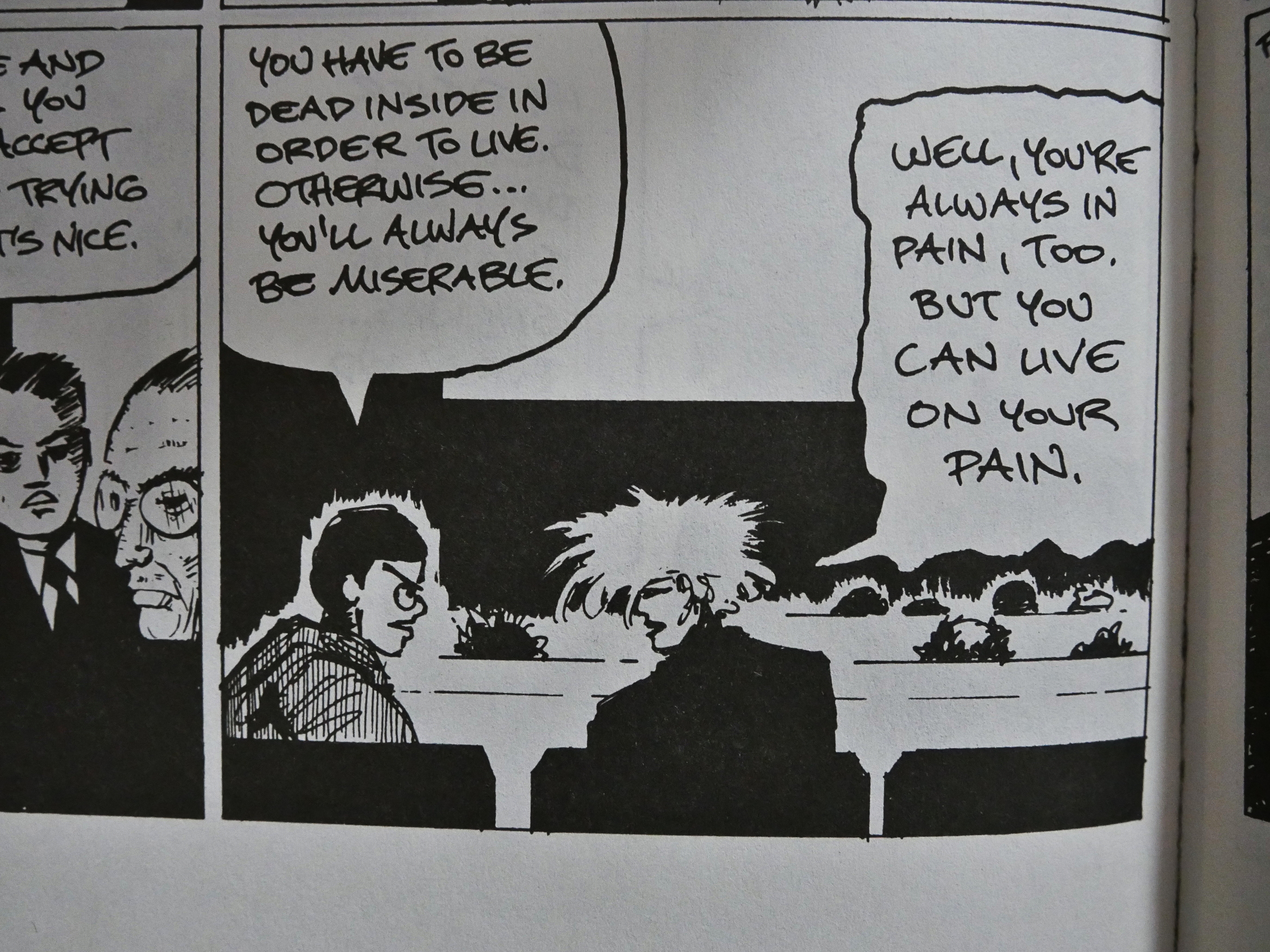

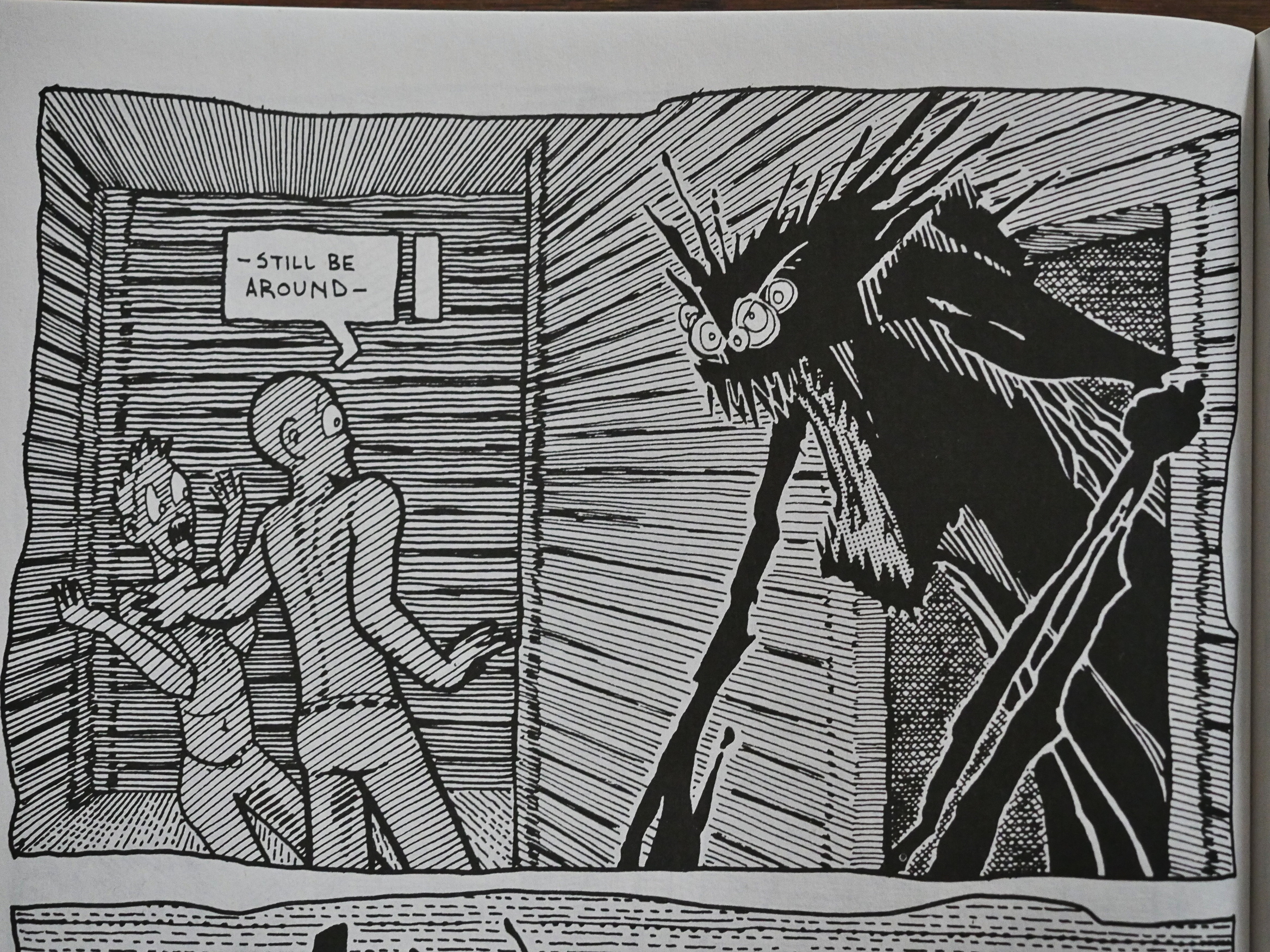

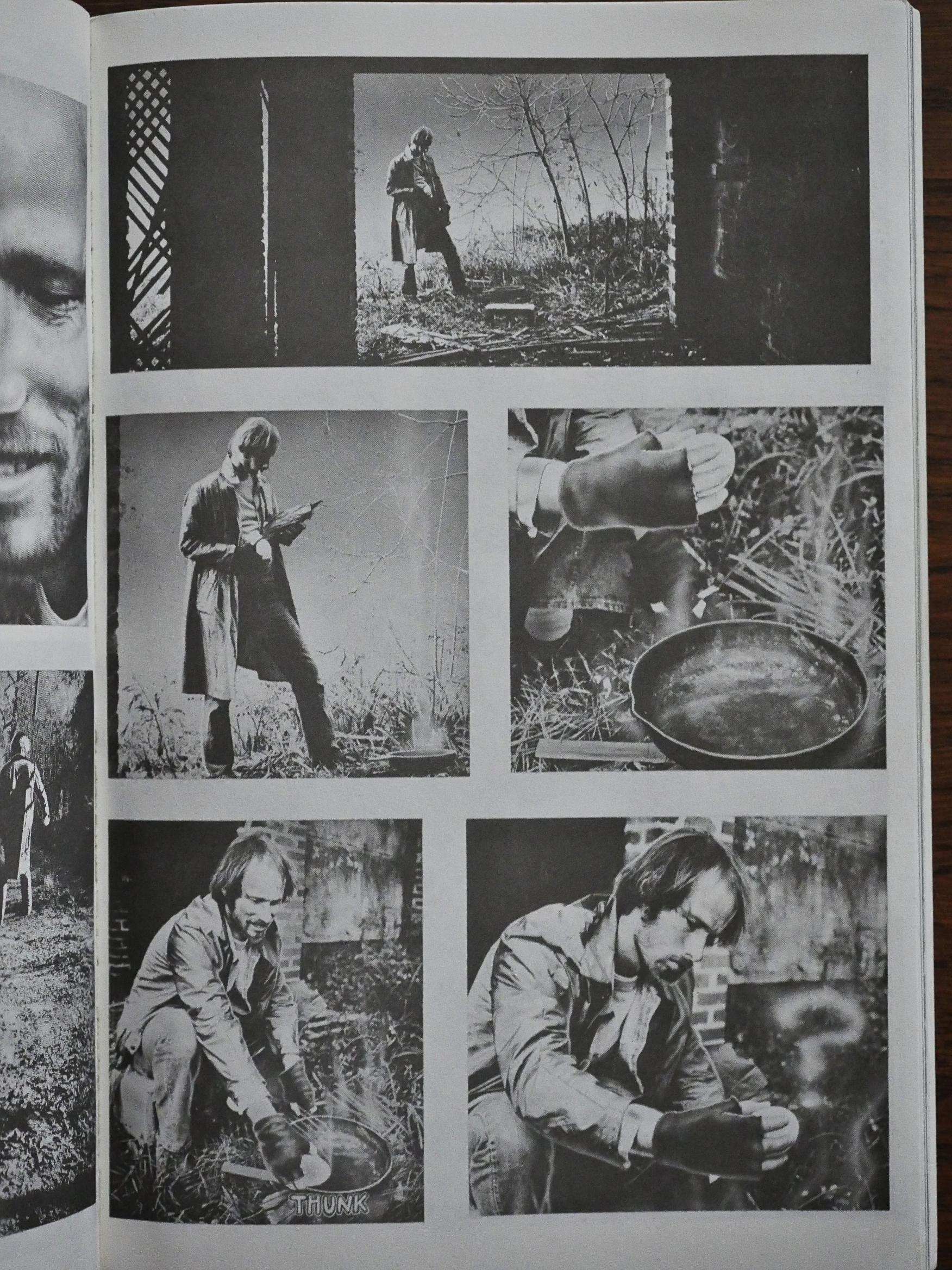

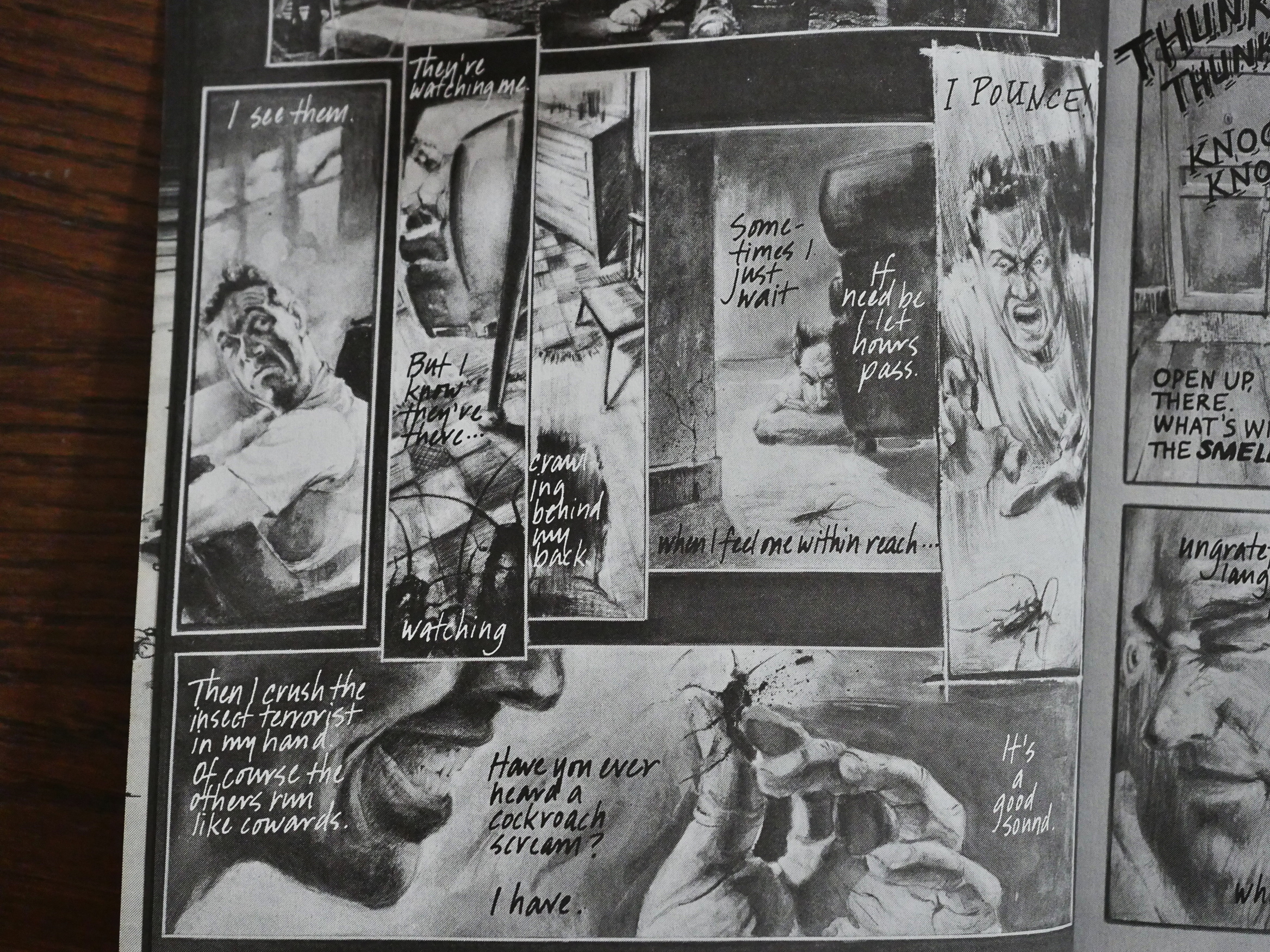

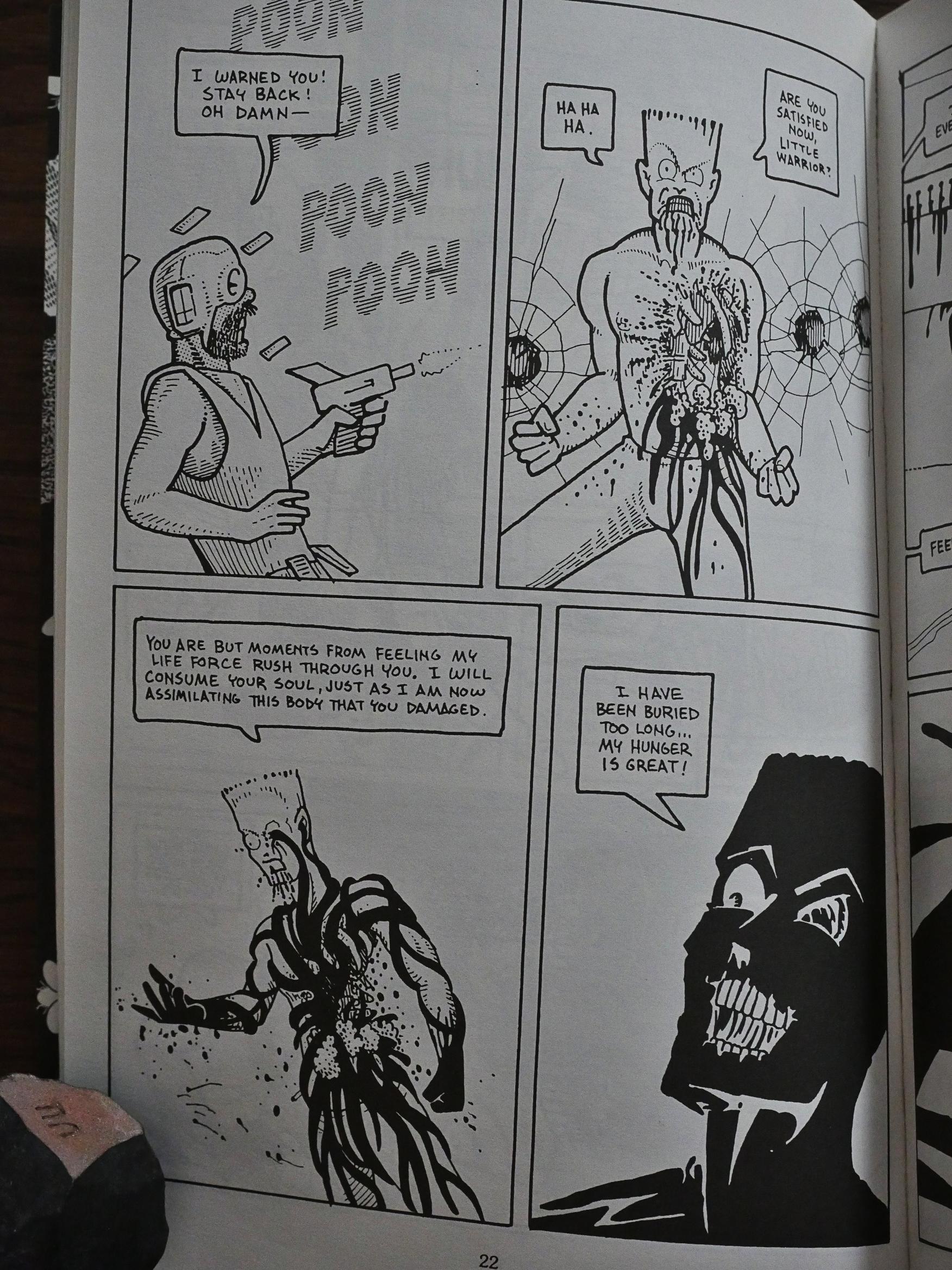

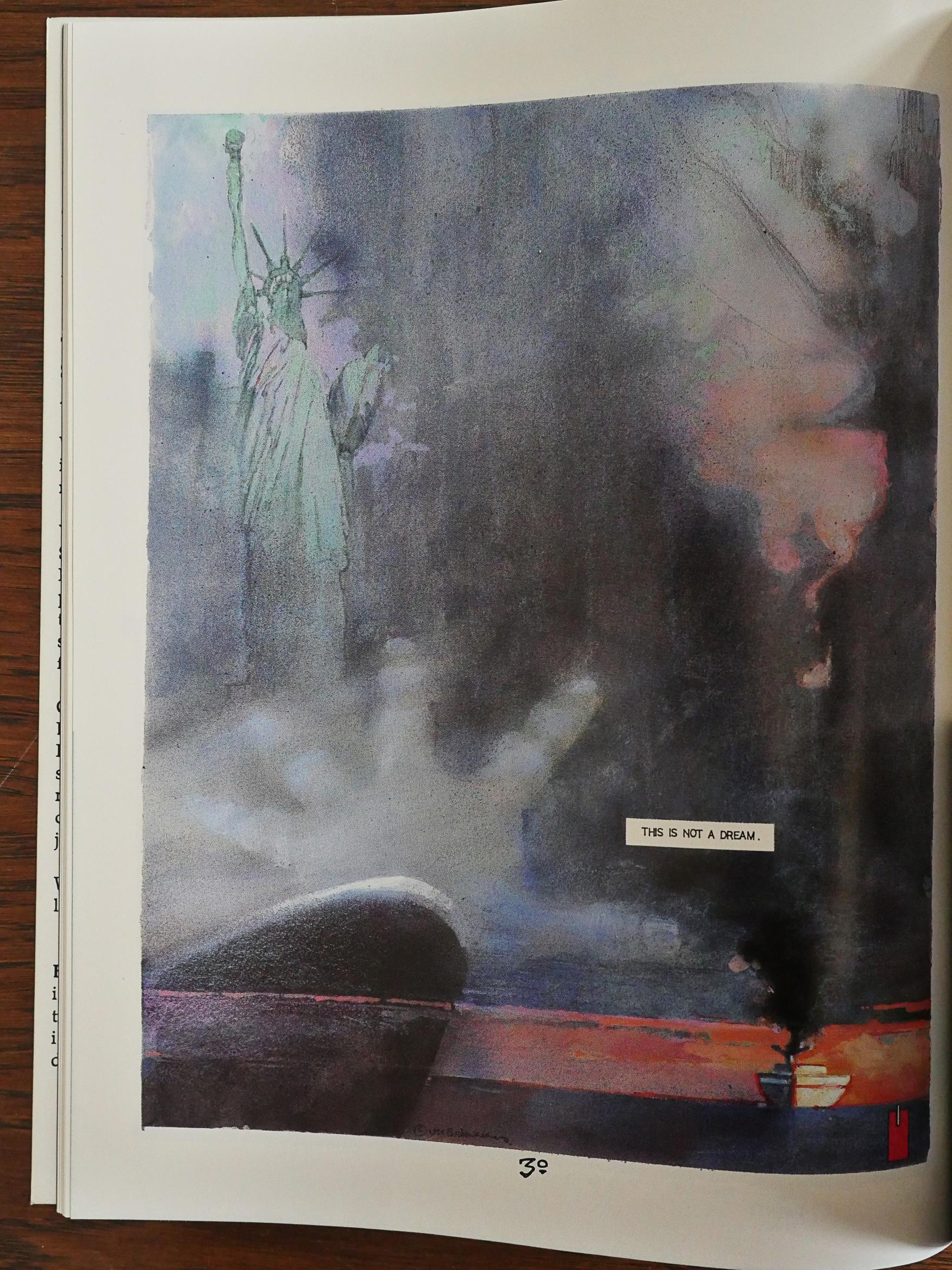

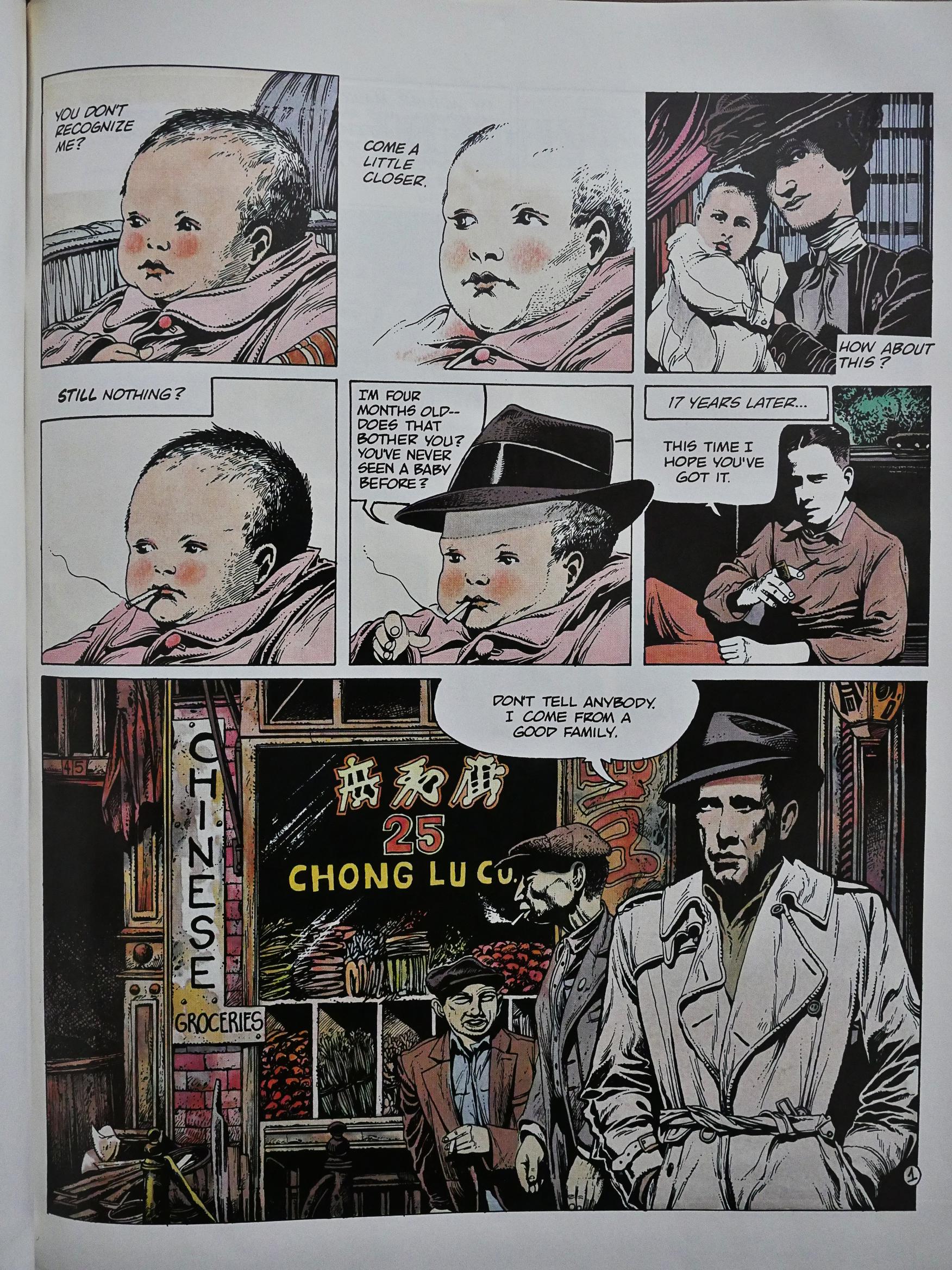

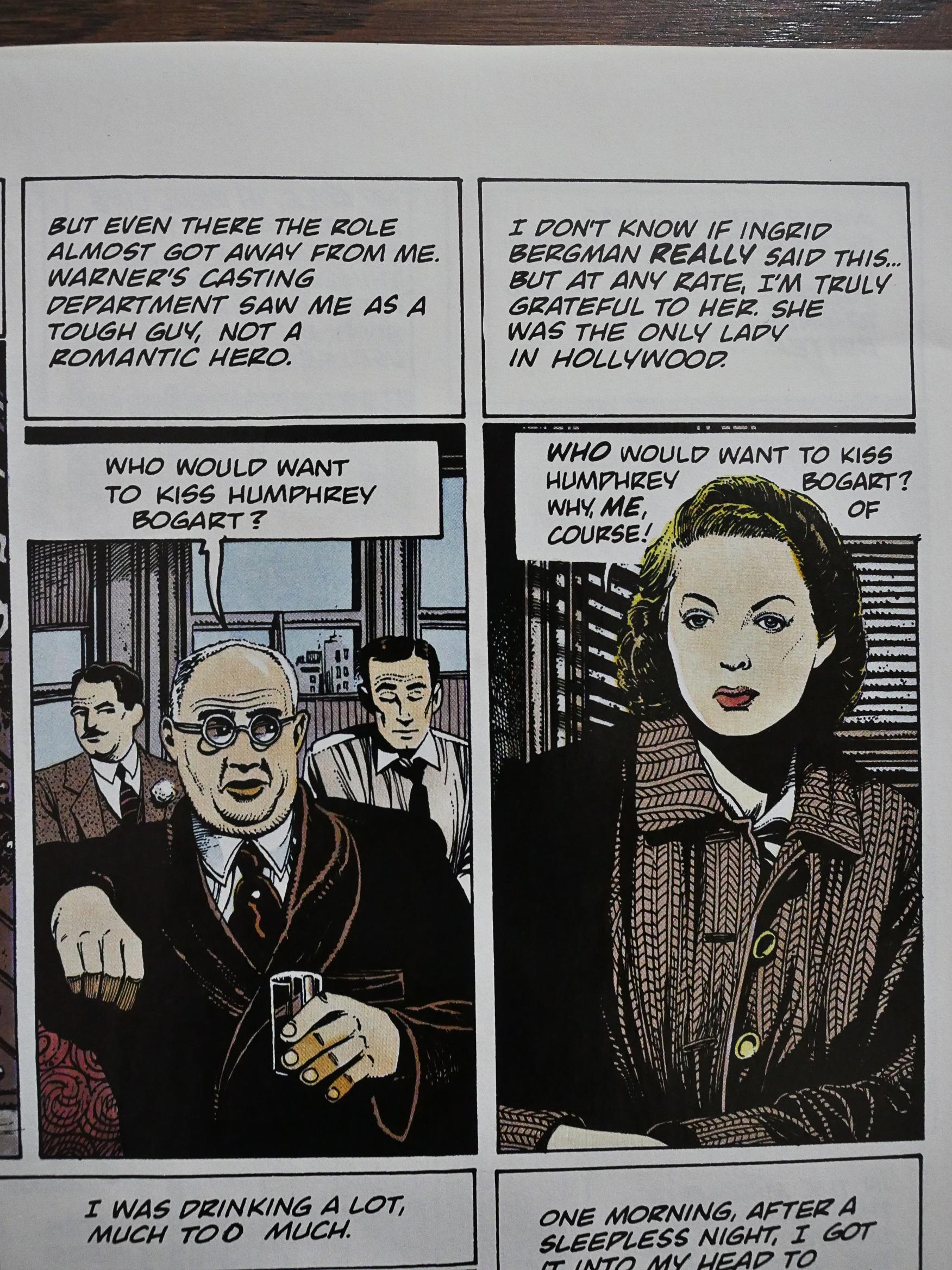

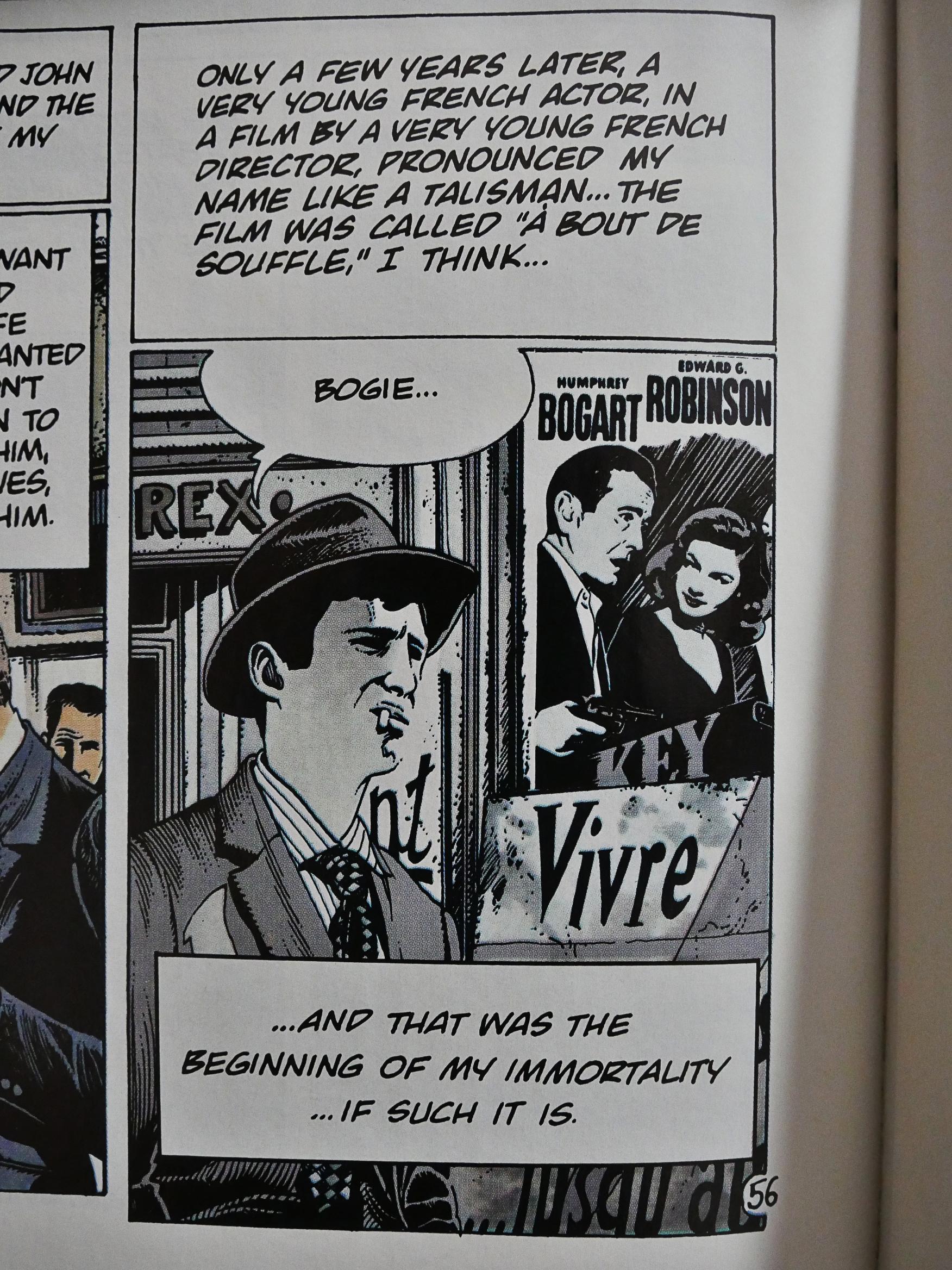

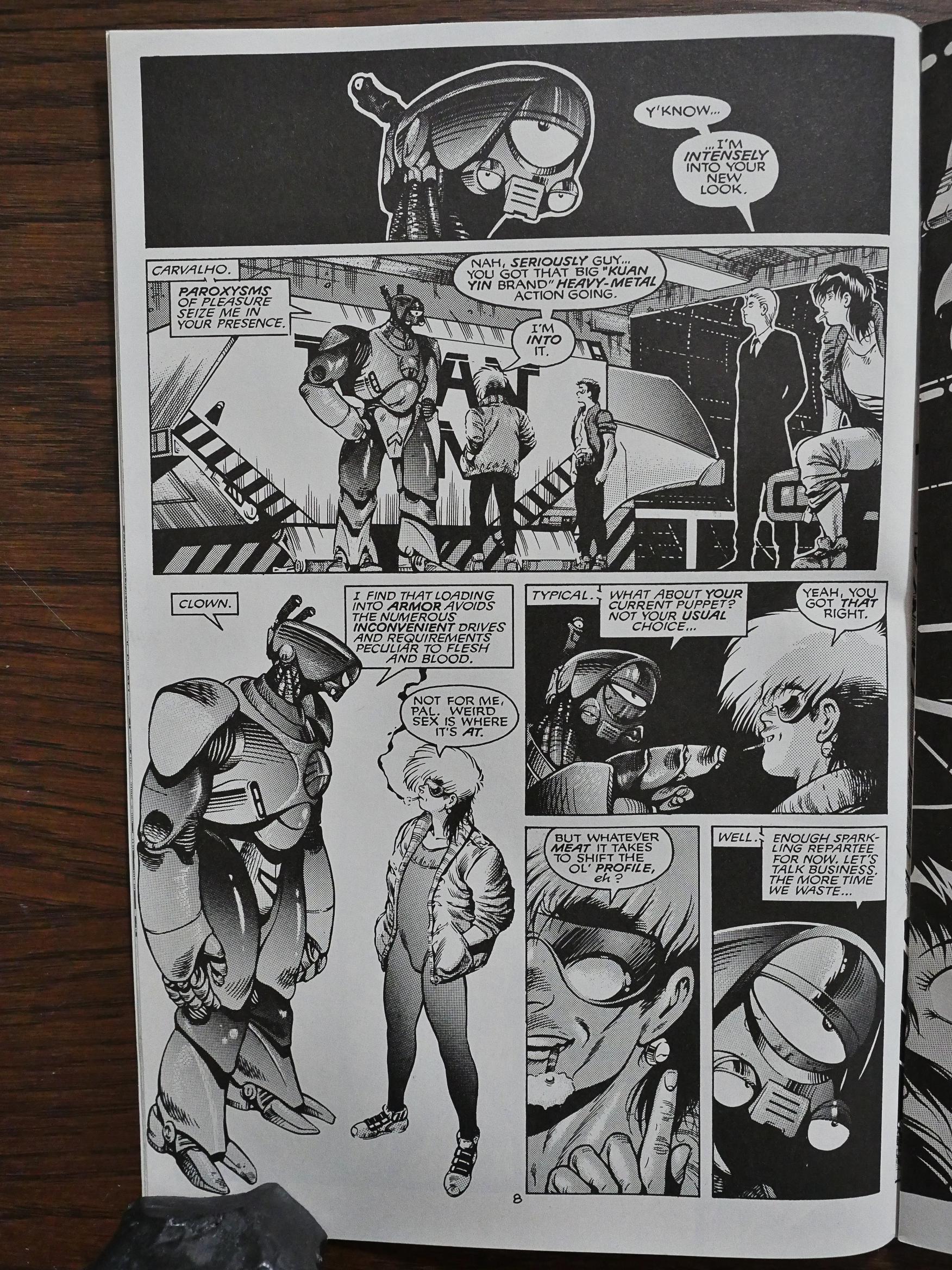

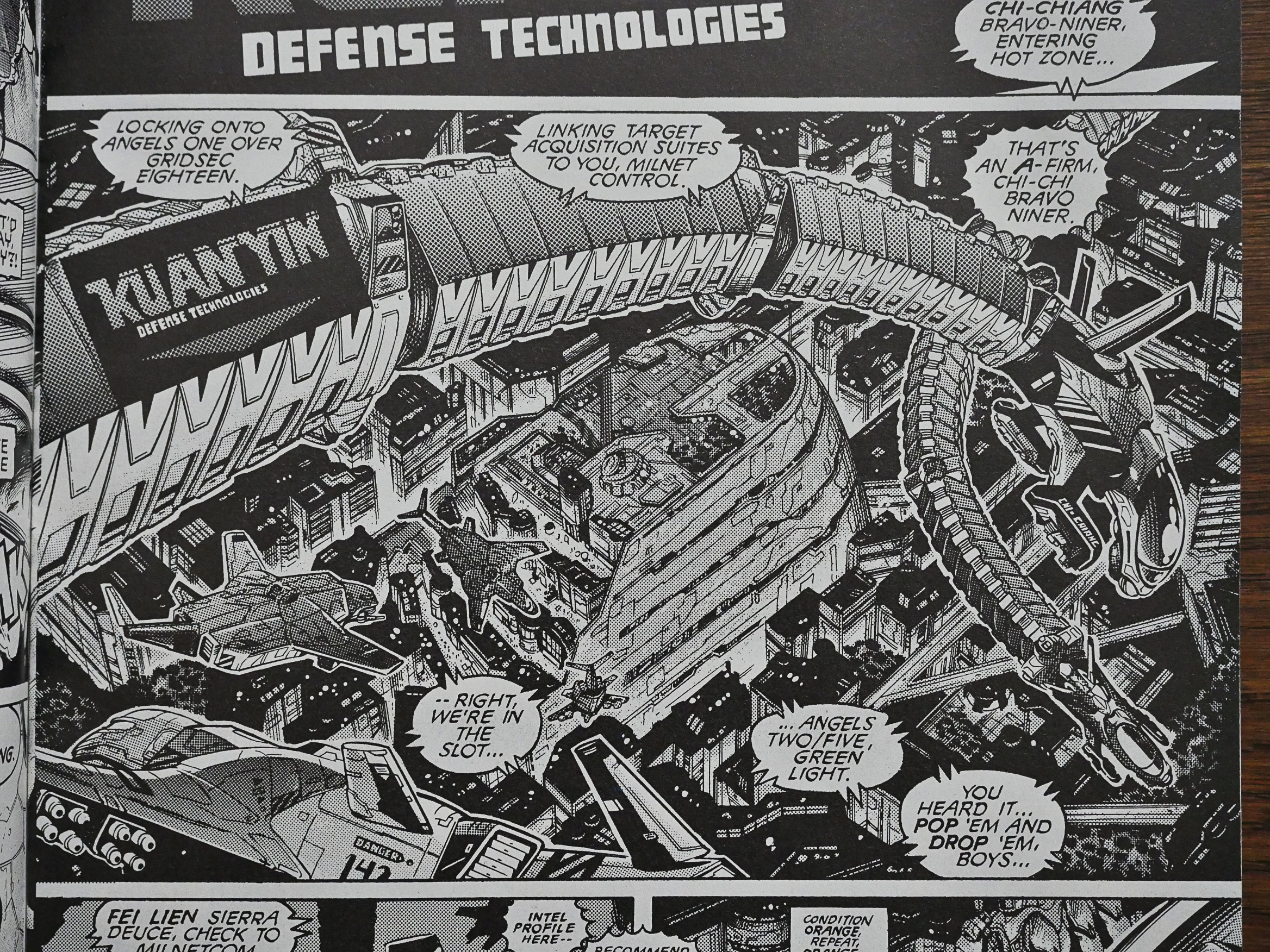

The Moore/Sienkiewicz part of this book is, as the introduction tells us, completely different. It says that it’s a “subjective, surreal and artistic interpretation”, and… I don’t think the middle bit is accurate.

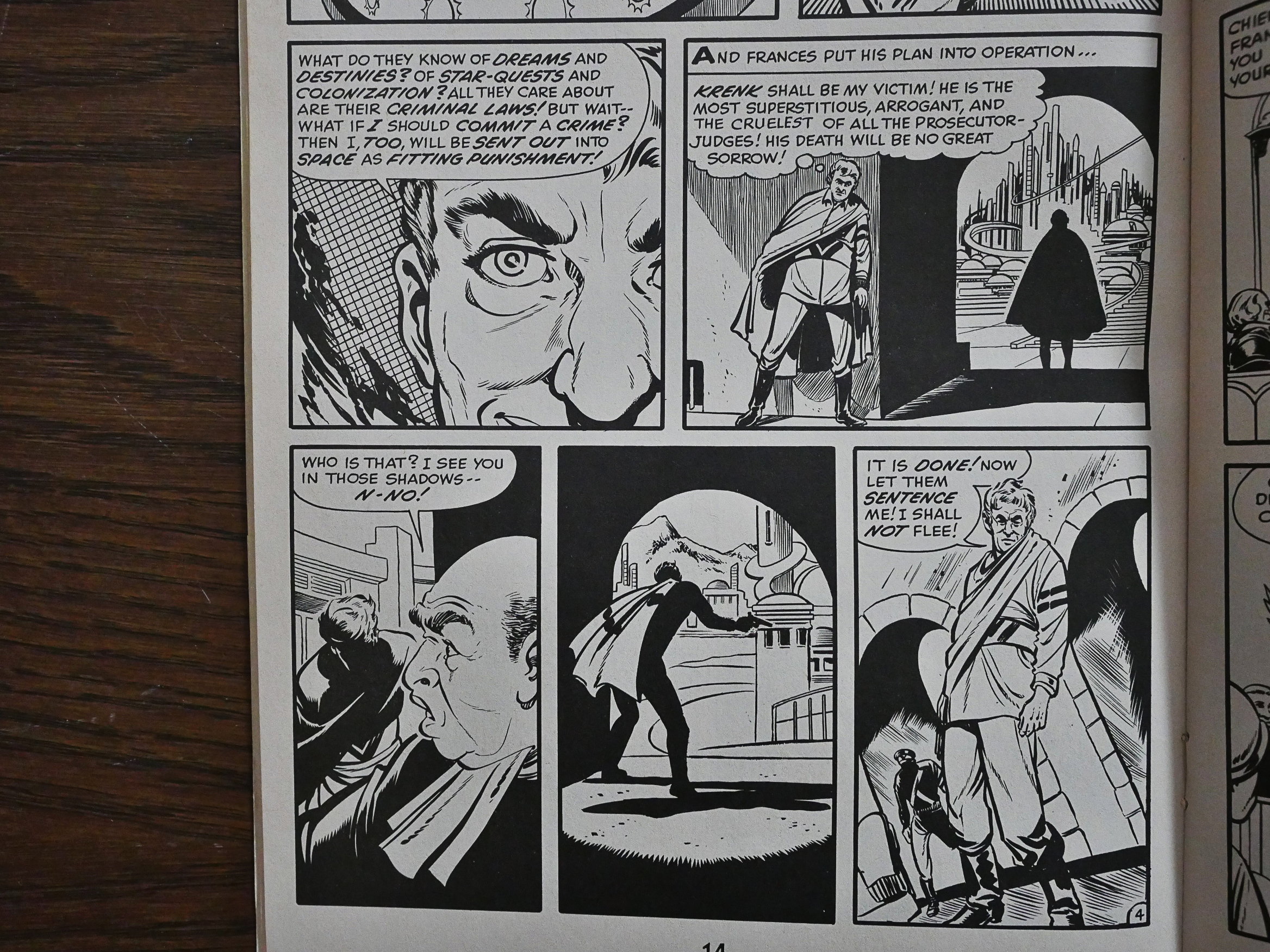

It’s not surreal; it’s just comics. This piece is told from the point of view of the CIA, represented here as a chain-smoking, hard-drinking eagle, which I think makes a lot of sense.

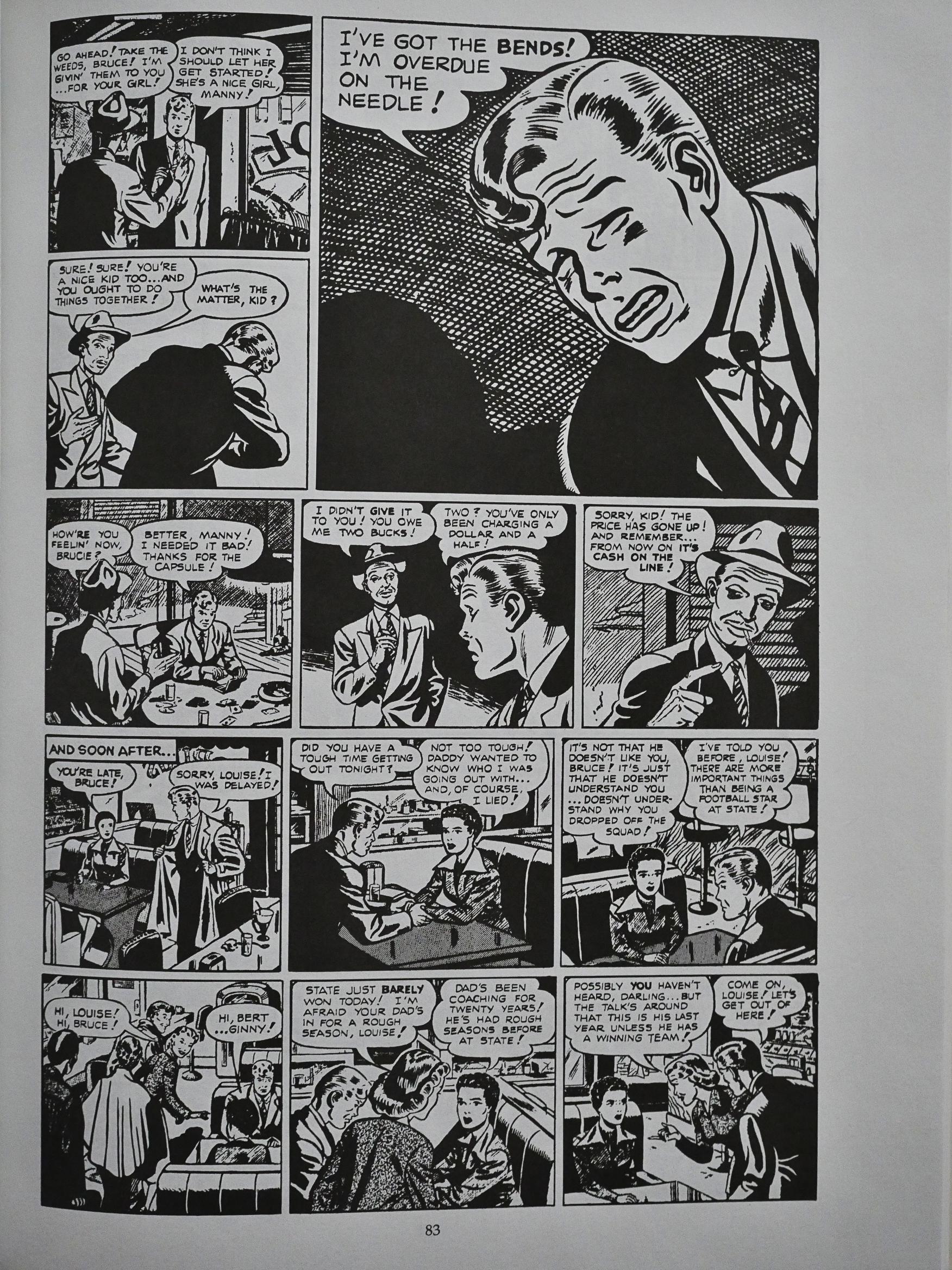

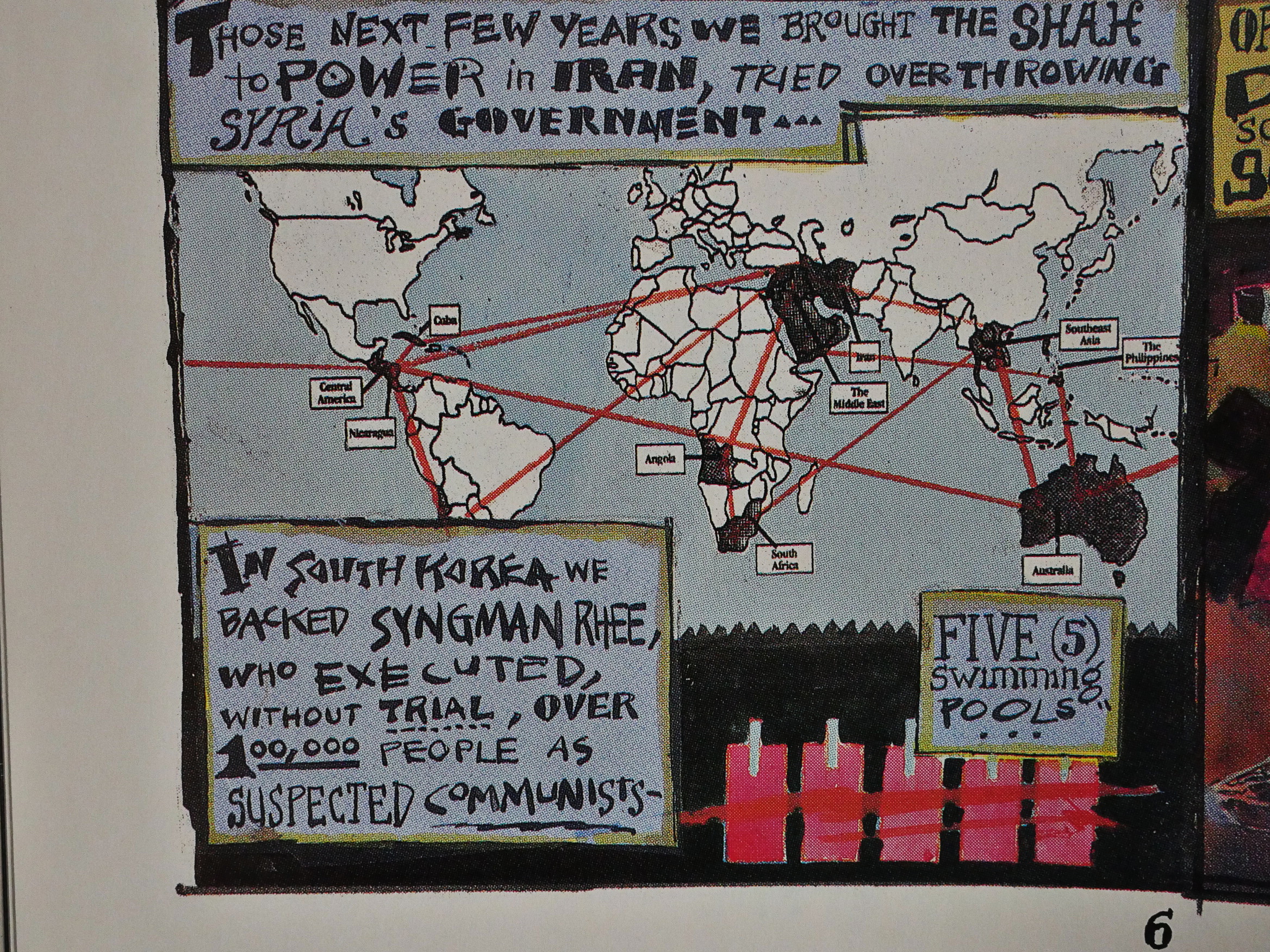

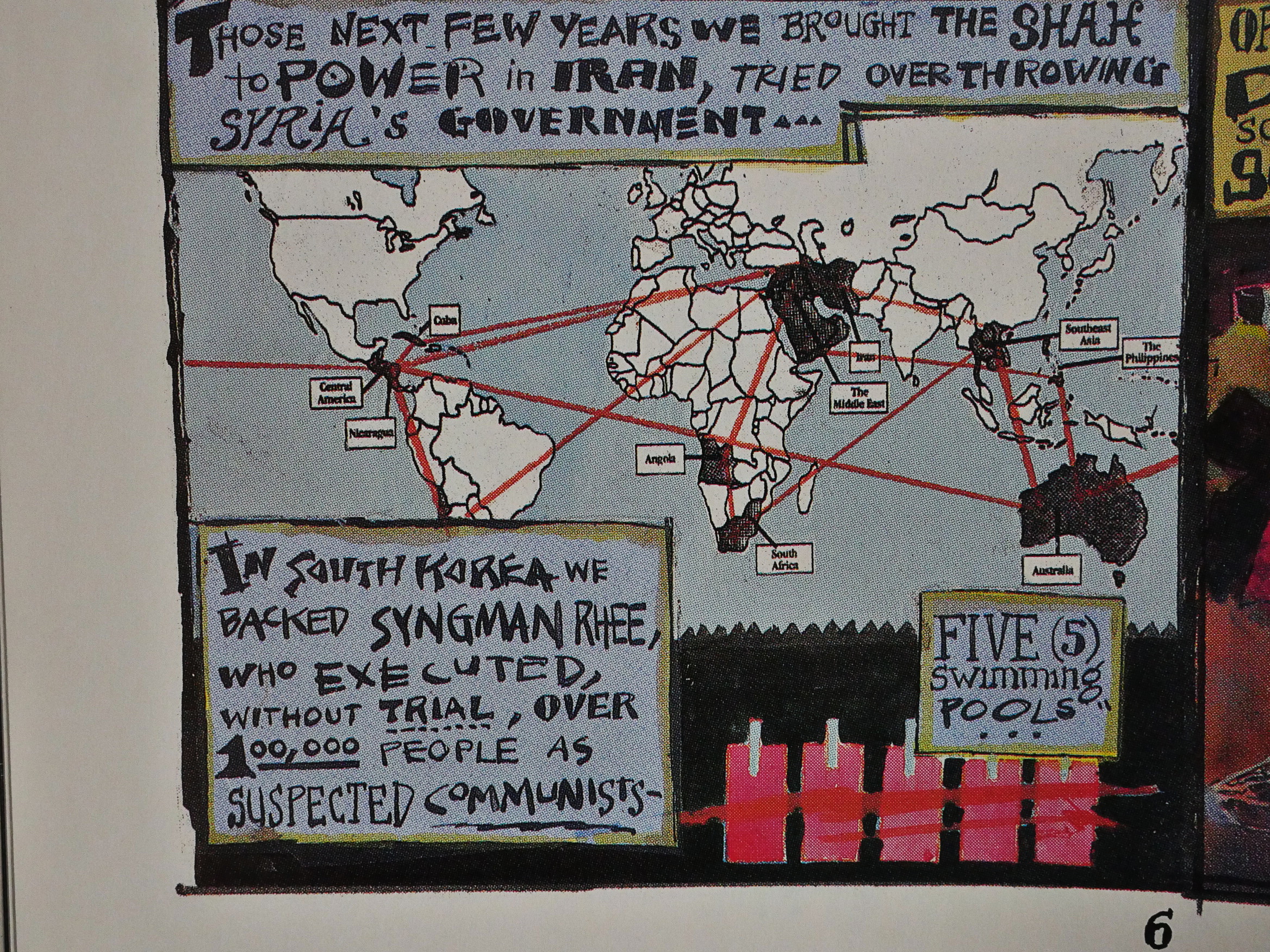

The main storytelling metaphor Moore uses is to represent 20K dead people with a swimming pool filled with blood.

So Syngman Rhee killing 100K people is five (5) swimming pools.

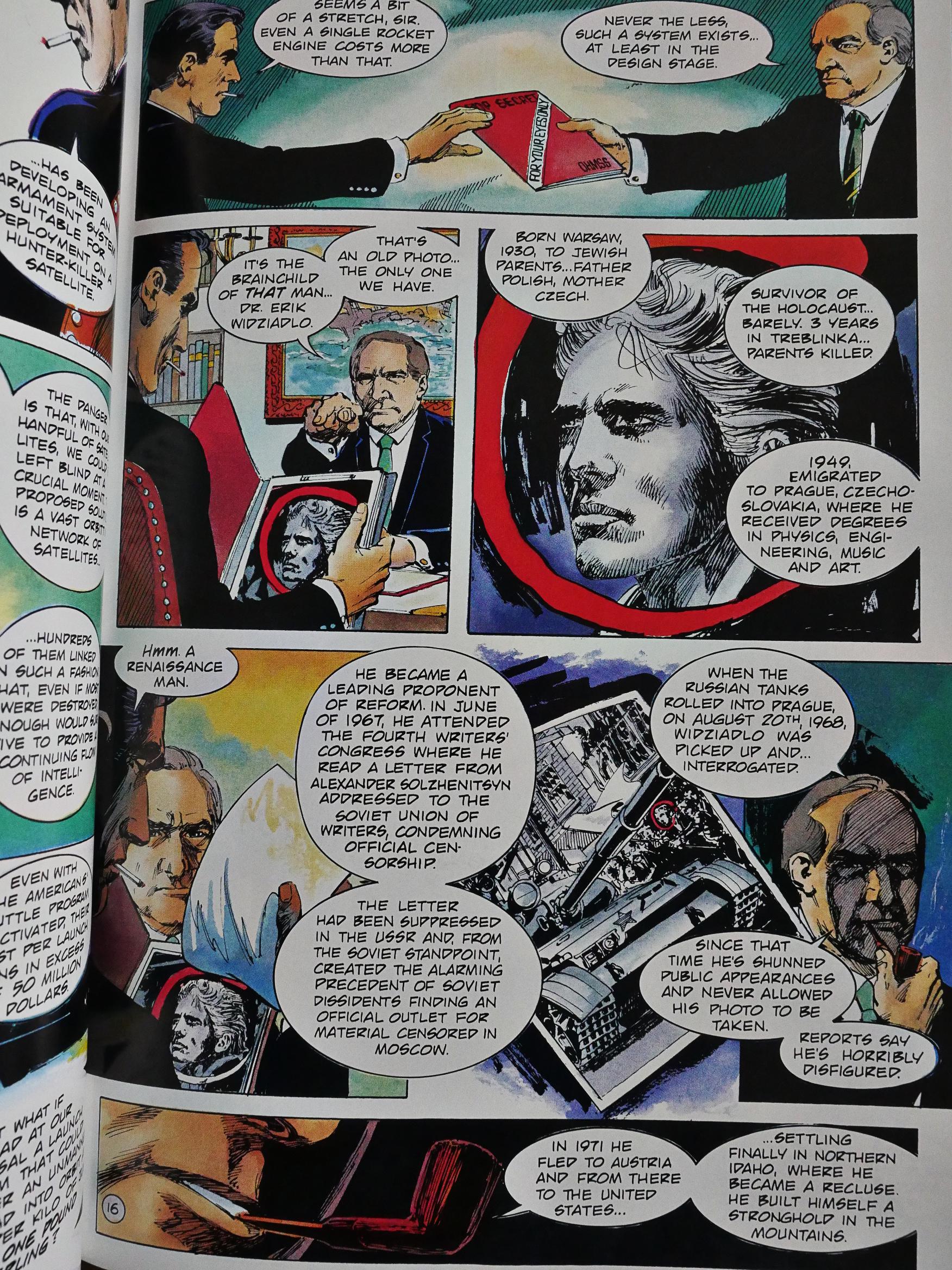

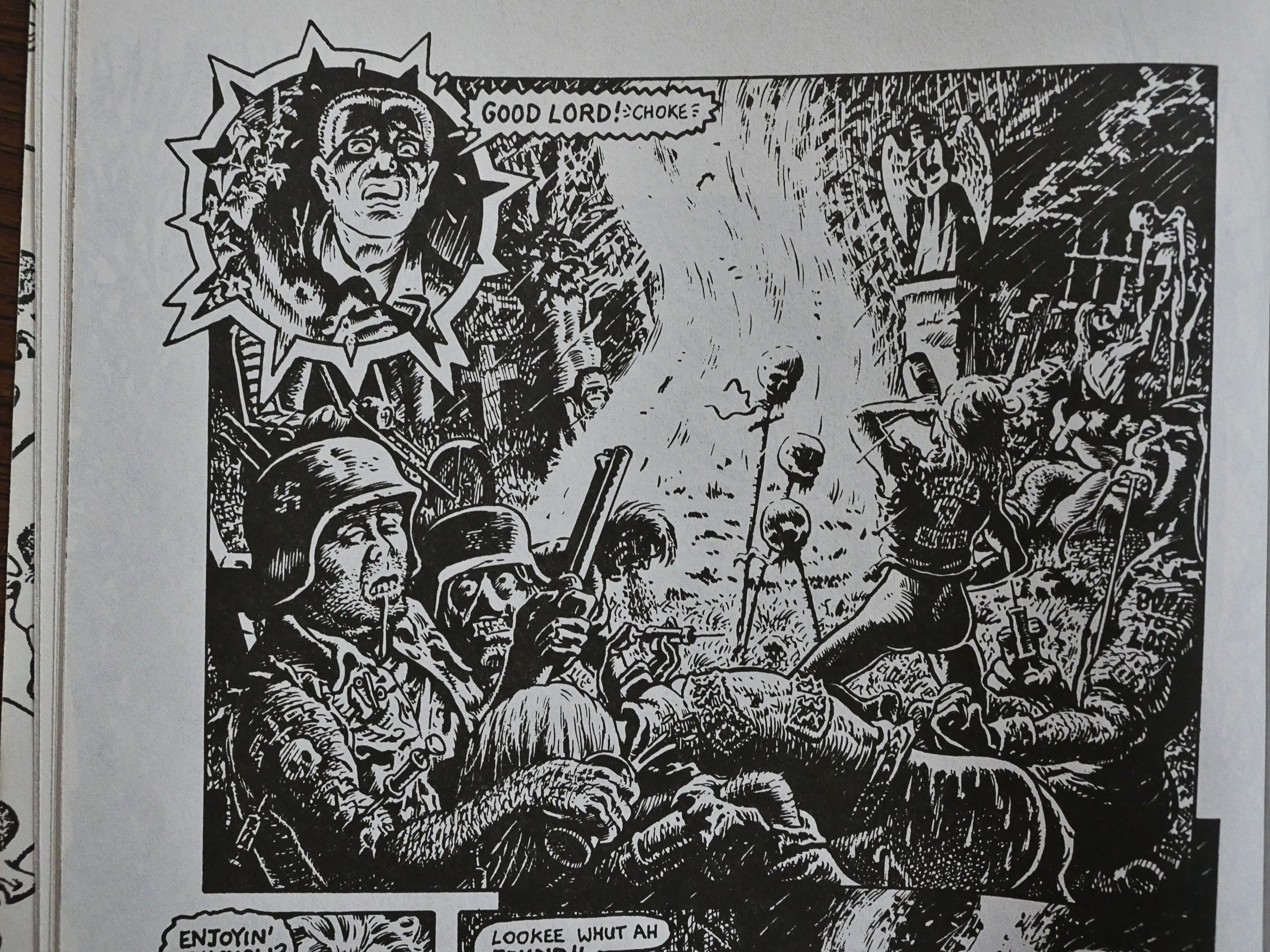

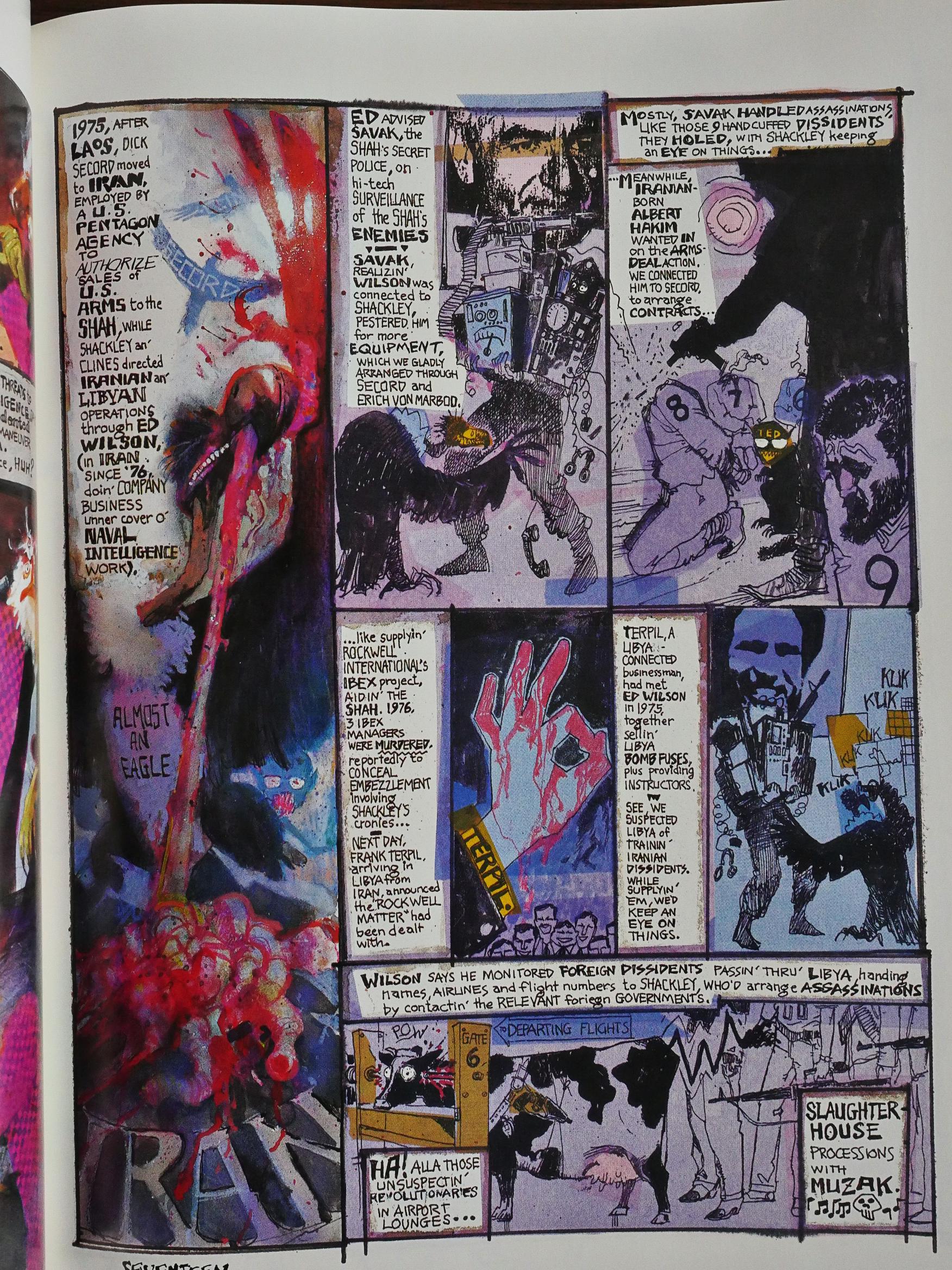

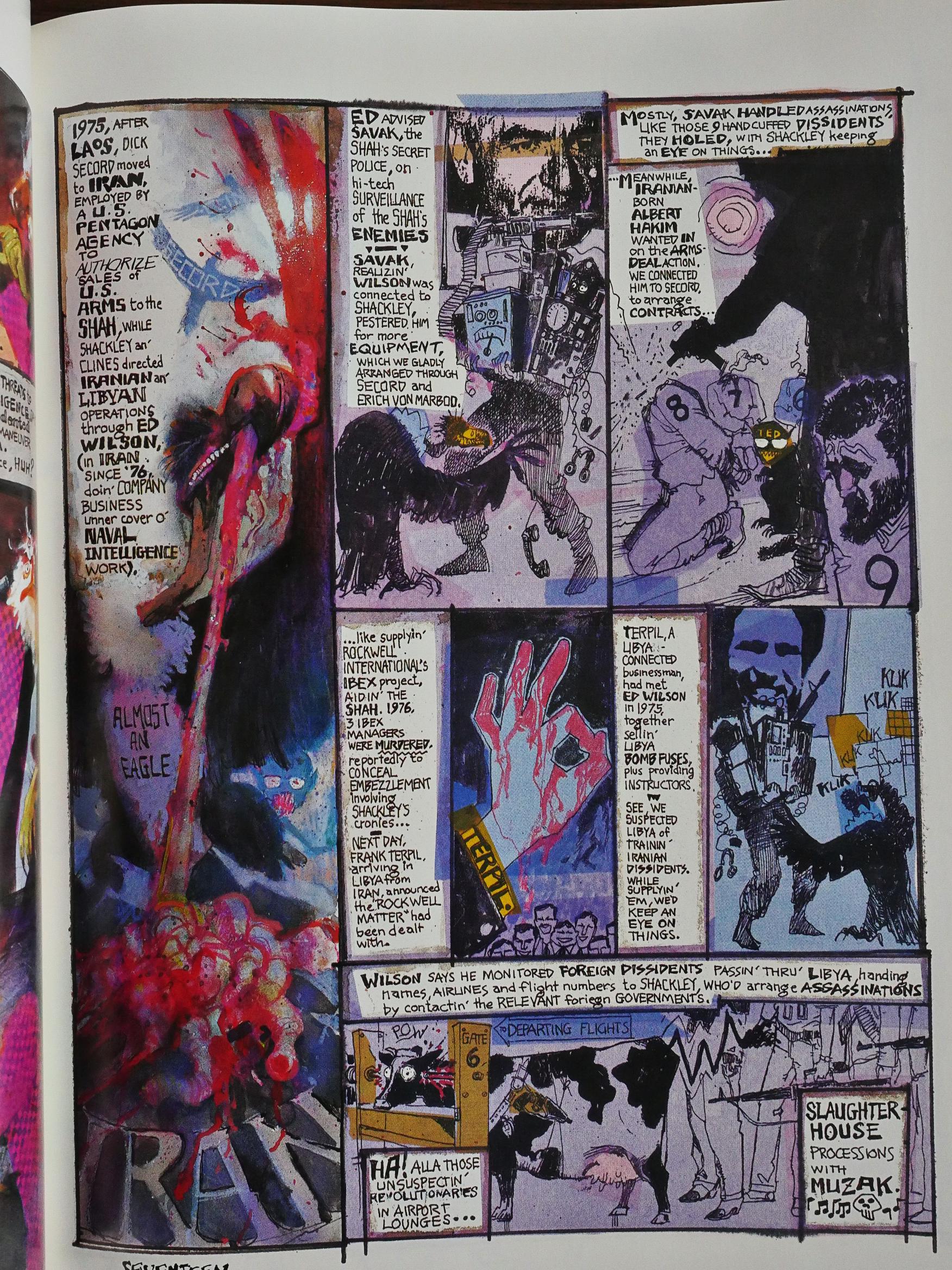

While Brabner told the story of the CIA killing the rebel Contra guy at La Penca, Moore basically tells the story of all major CIA “secret” operations from WWII and to the present date, so there’s a lot of information to get through.

Most of what Moore describes was controversial at the time (*gasp* “CIA involved with toppling Allende in Chile? What slander!”) has now transmogrified into things that are self-evident and trivial (*yawn* “Of course the CIA had to intervene. It’s just common sense.”) without ever stopping by the “Oops; sorry for lying all these years” stage.

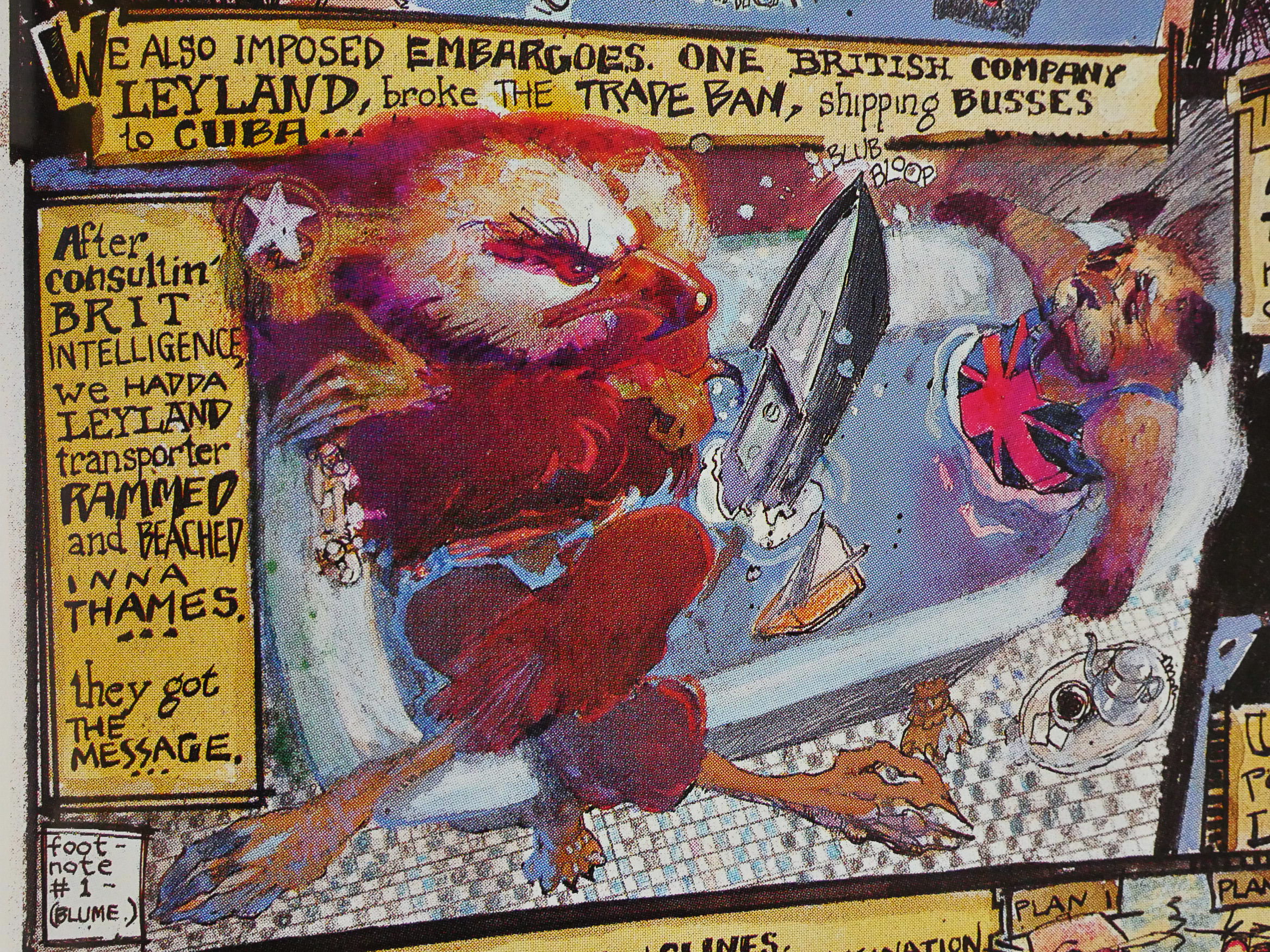

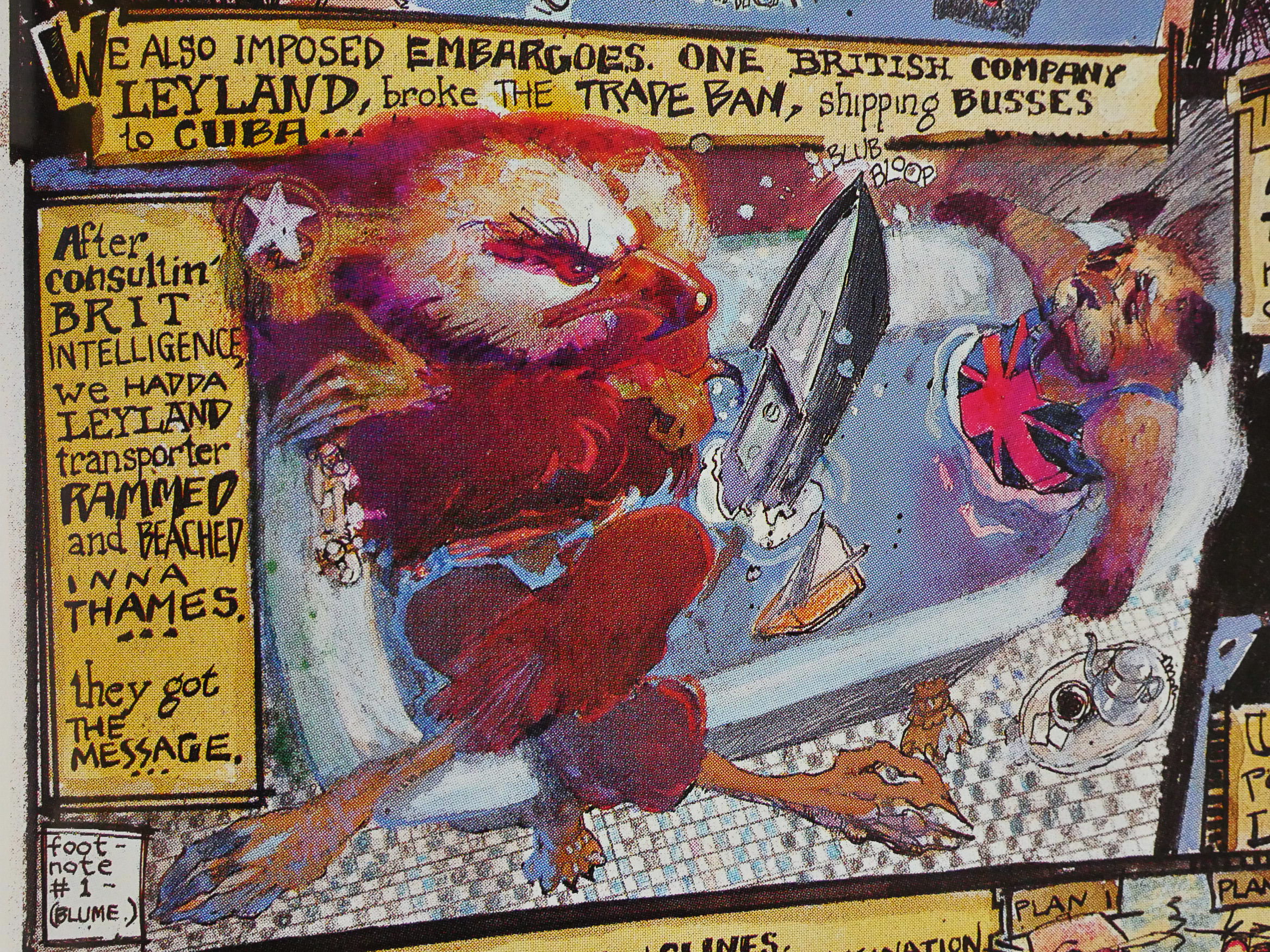

But this one had me googling, and… it seems like the jury is still out on this one. Did the CIA arrange to scuttle a ship transporting Leyland buses to Cuba? Perhaps not.

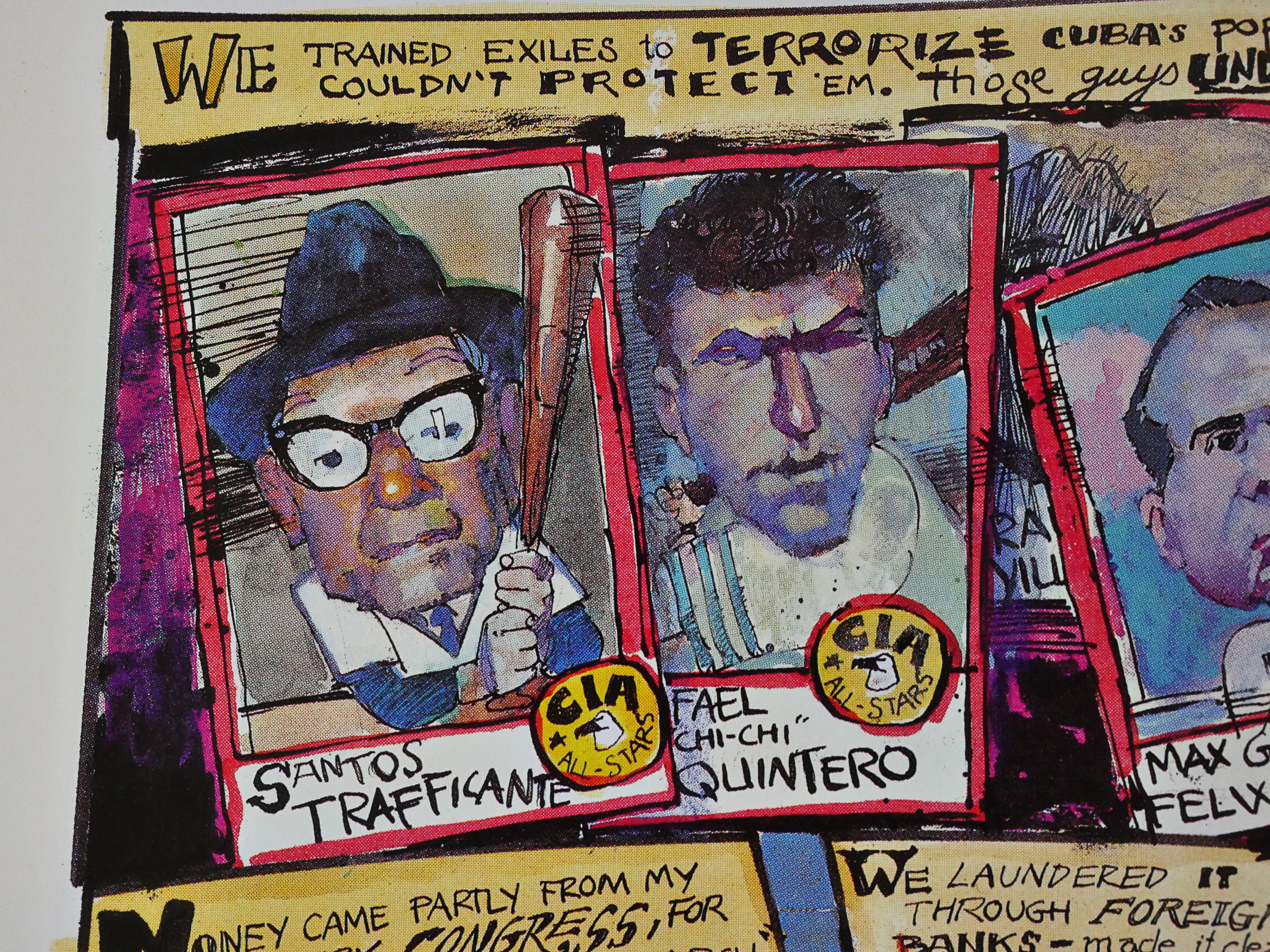

Heh. We’ll later in this blog series cover Eclipse’s non-sports “trading cards”, many of which also cover current events. I think first up are cards on the Iran-Contra scandal, and Sienkiewicz drew (some?) of those. So this is cross-over advertising!

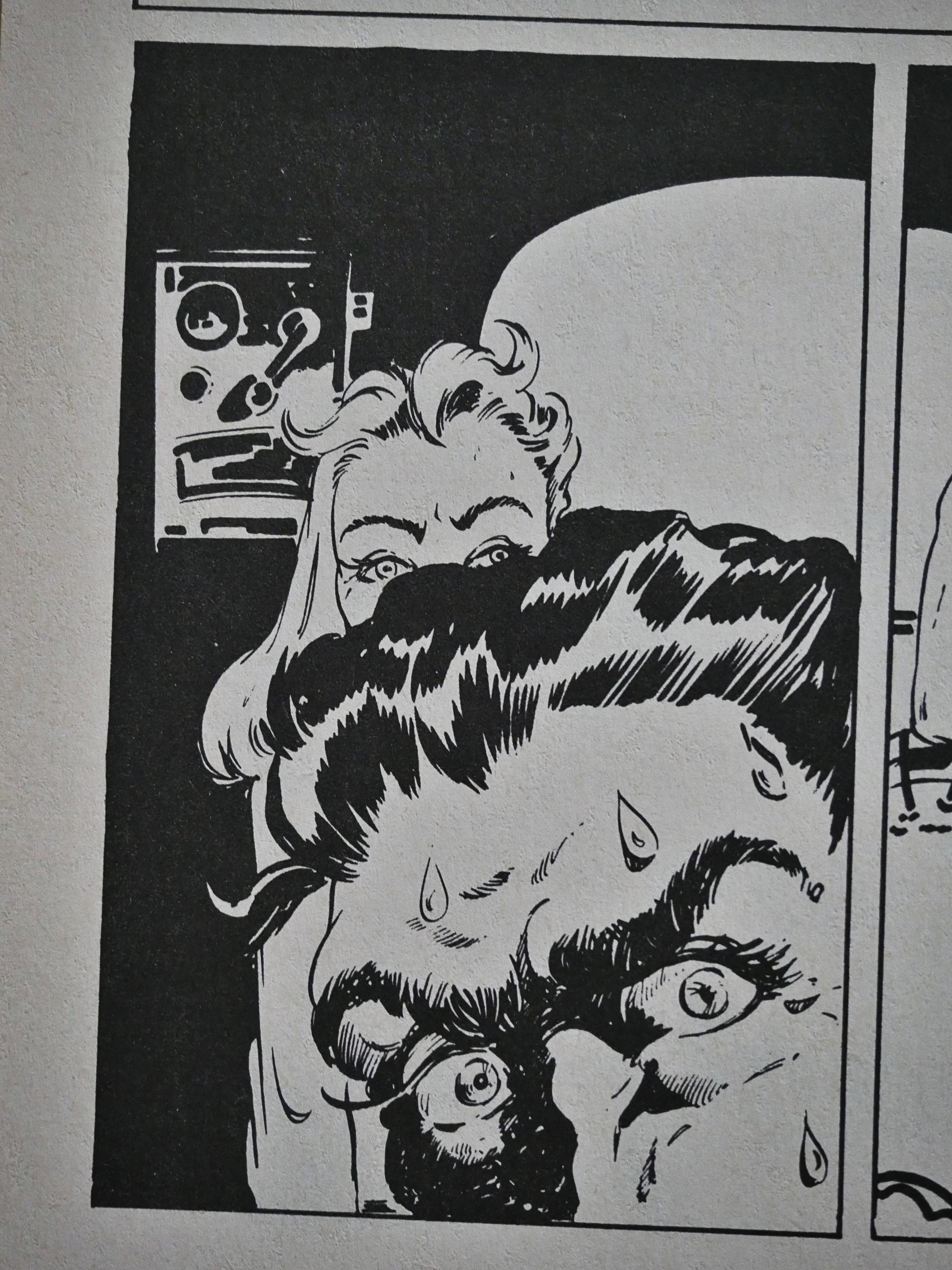

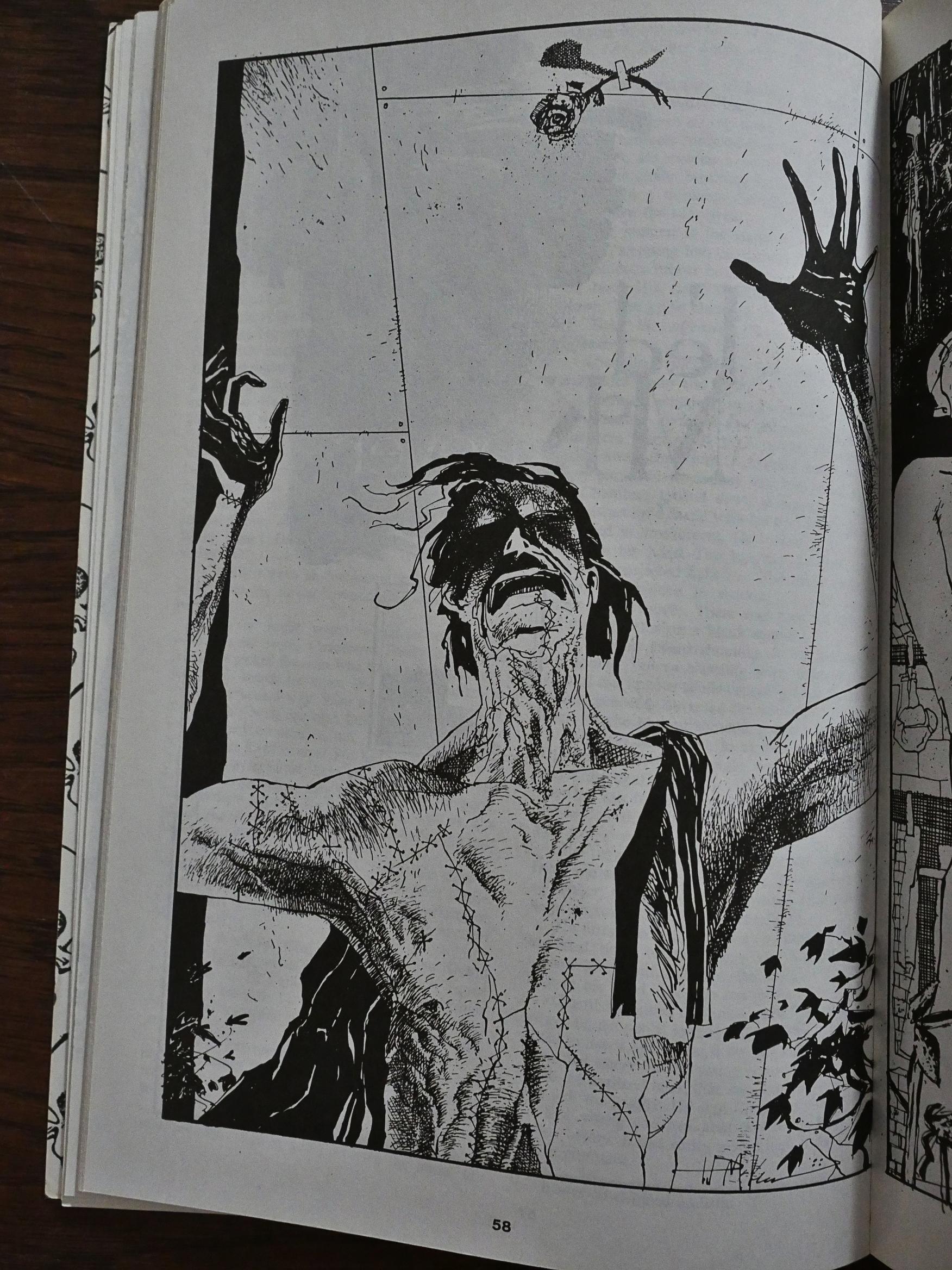

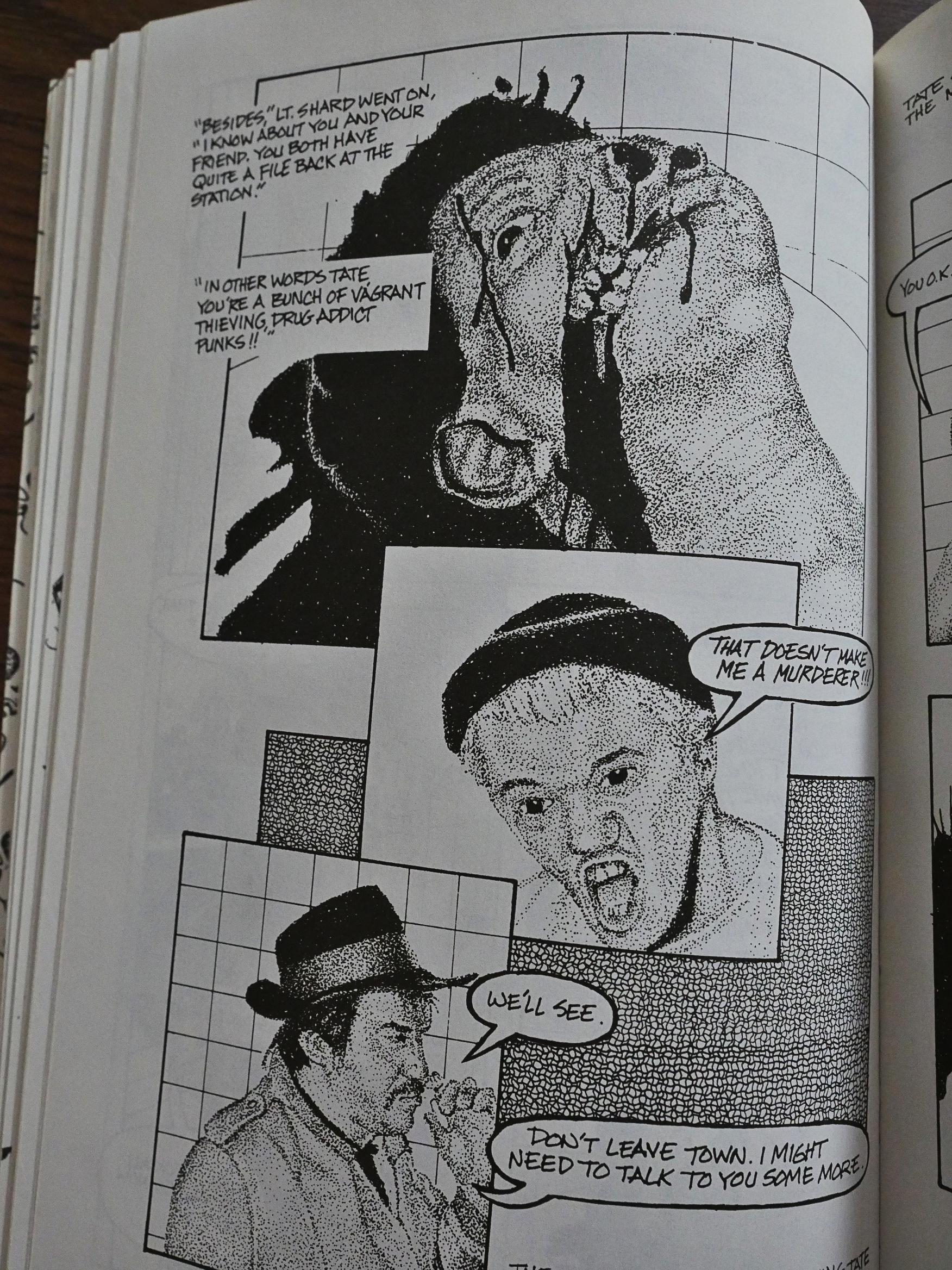

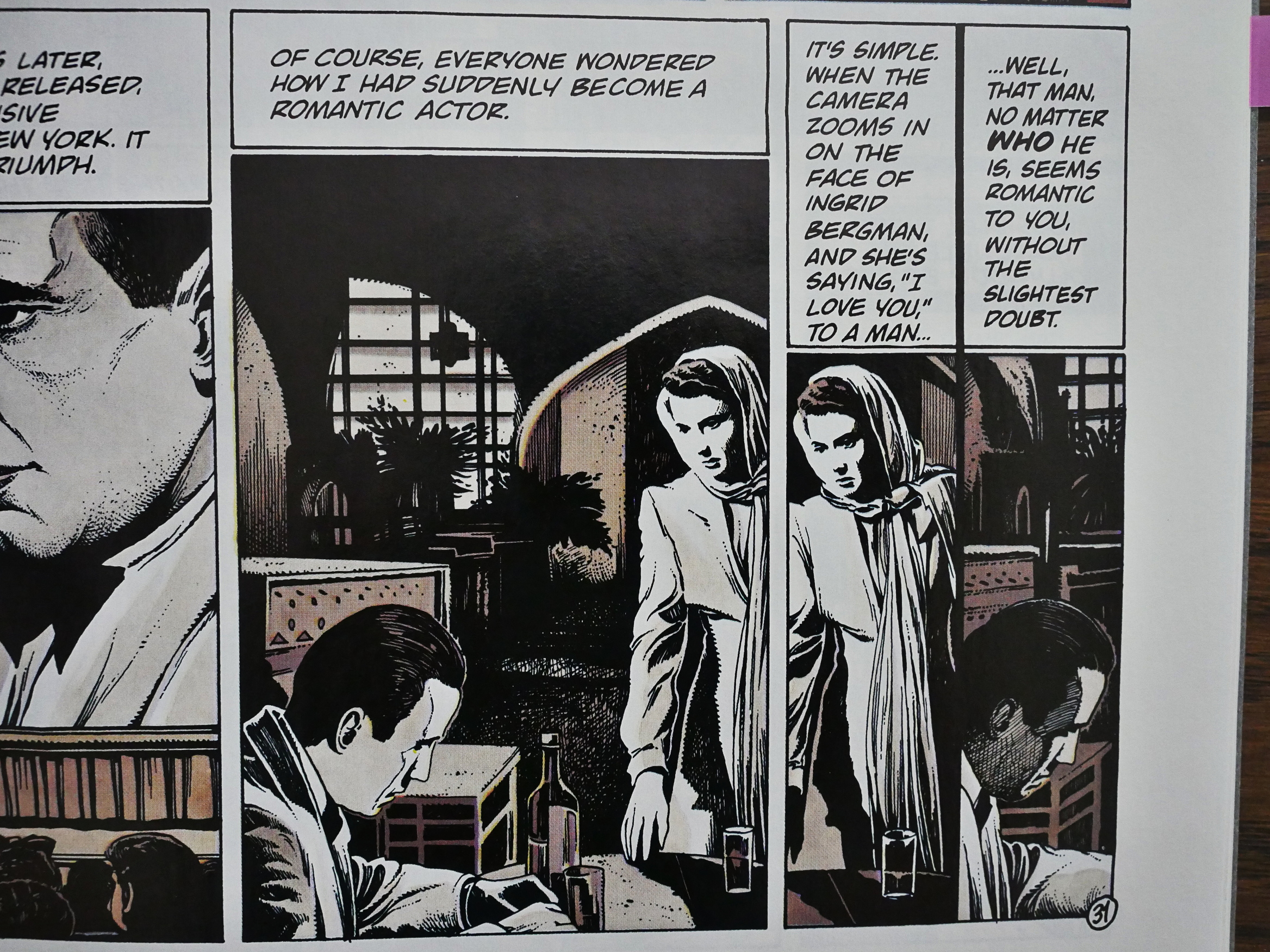

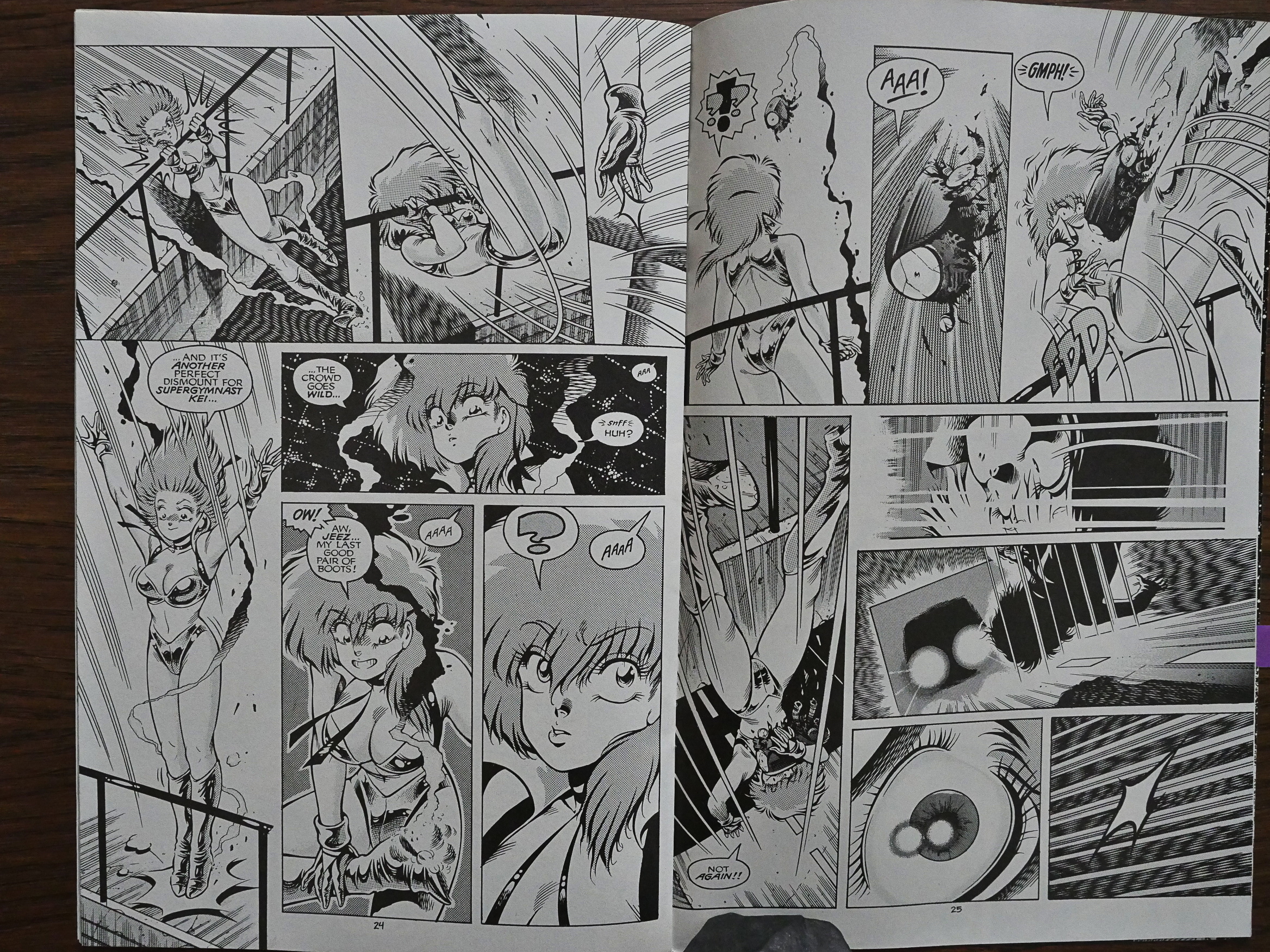

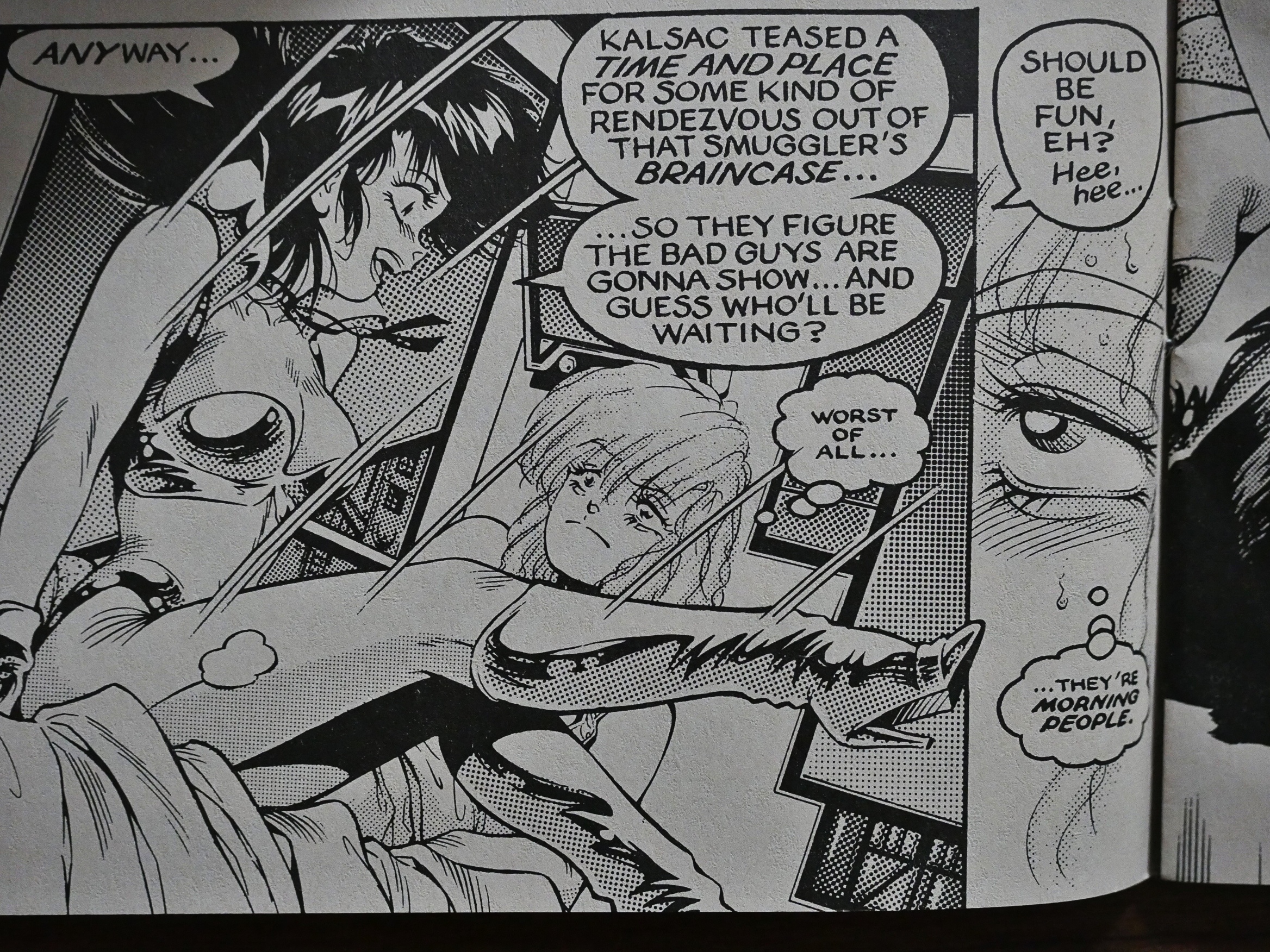

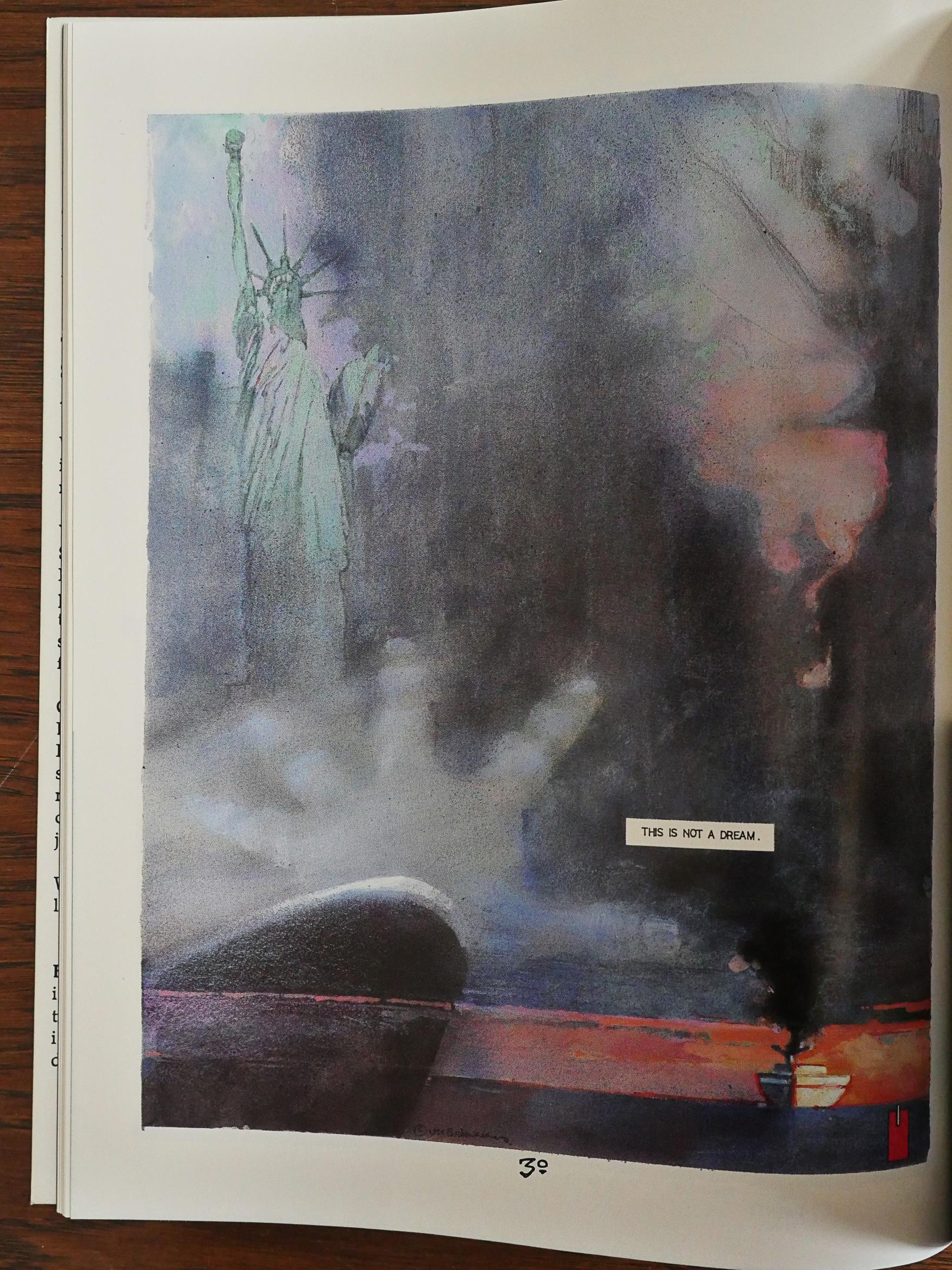

Sienkiewicz artwork (and lettering) for this piece is wonderful. It’s as deranged and blood-soaked as the CIA operations were. I think he does some of the best work of his career here, and he’s done a lot of really good stuff. I mean, look at that cow.

It’s not Moore’s best work, though. He tries to fit so much stuff into these short 30 pages that my eyes had started glazing over by the time I got to this page.

There’s a framing sequence of sorts, though: Just a couple of pages before and after the main action, not told in the CIA guy’s hectoring voice, but instead in Moore’s more portentous one, and the ending gave me chills.

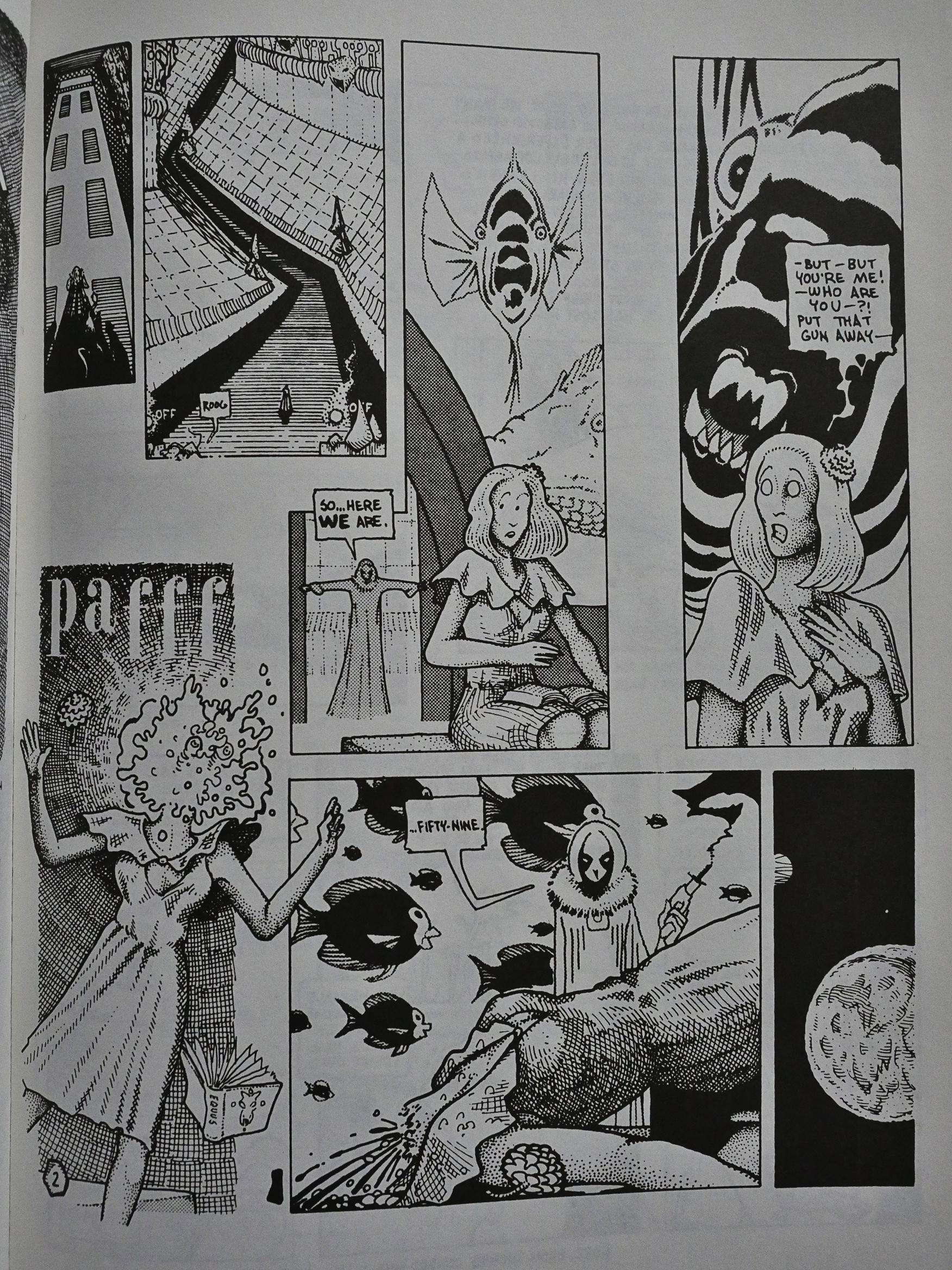

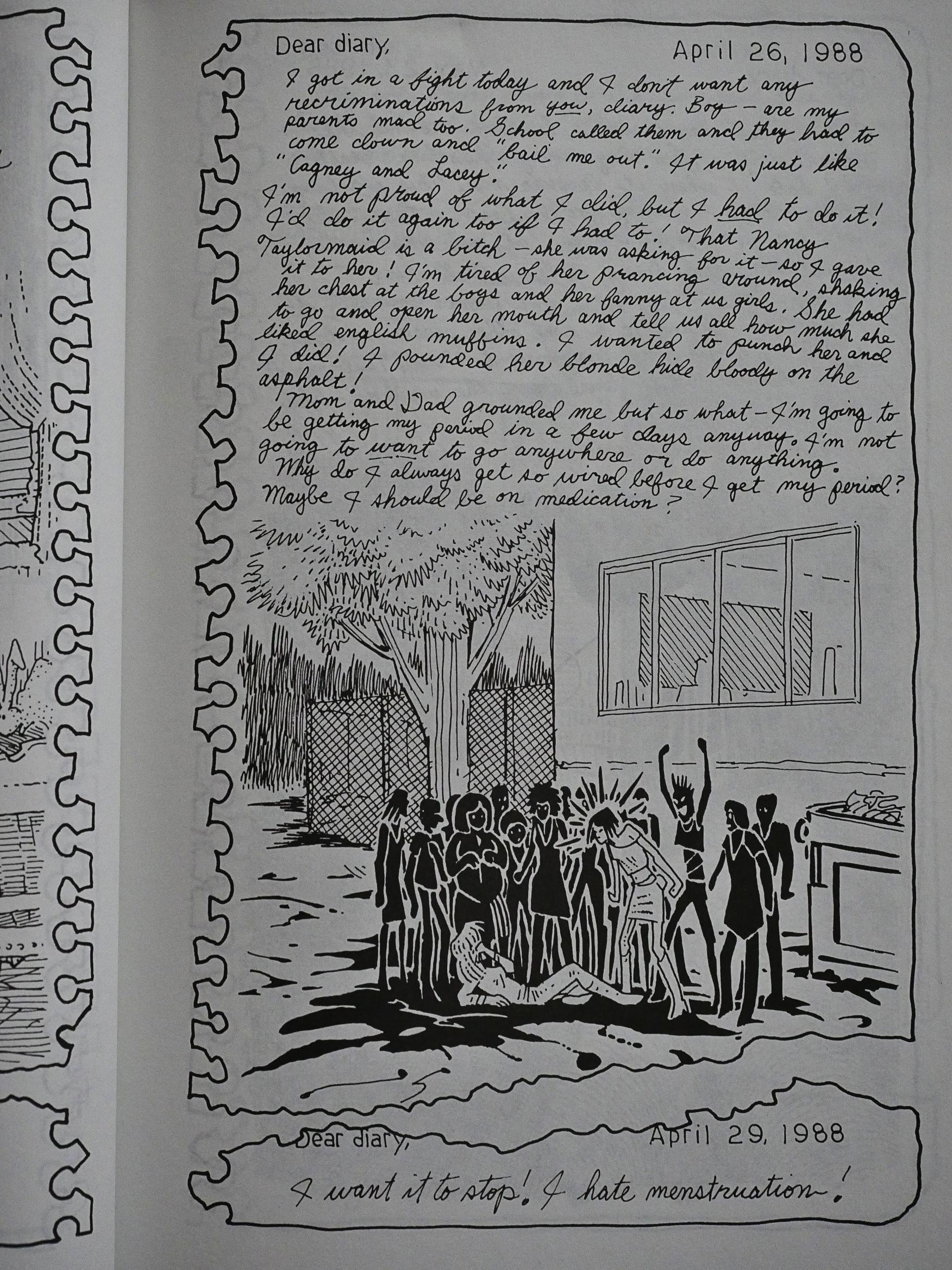

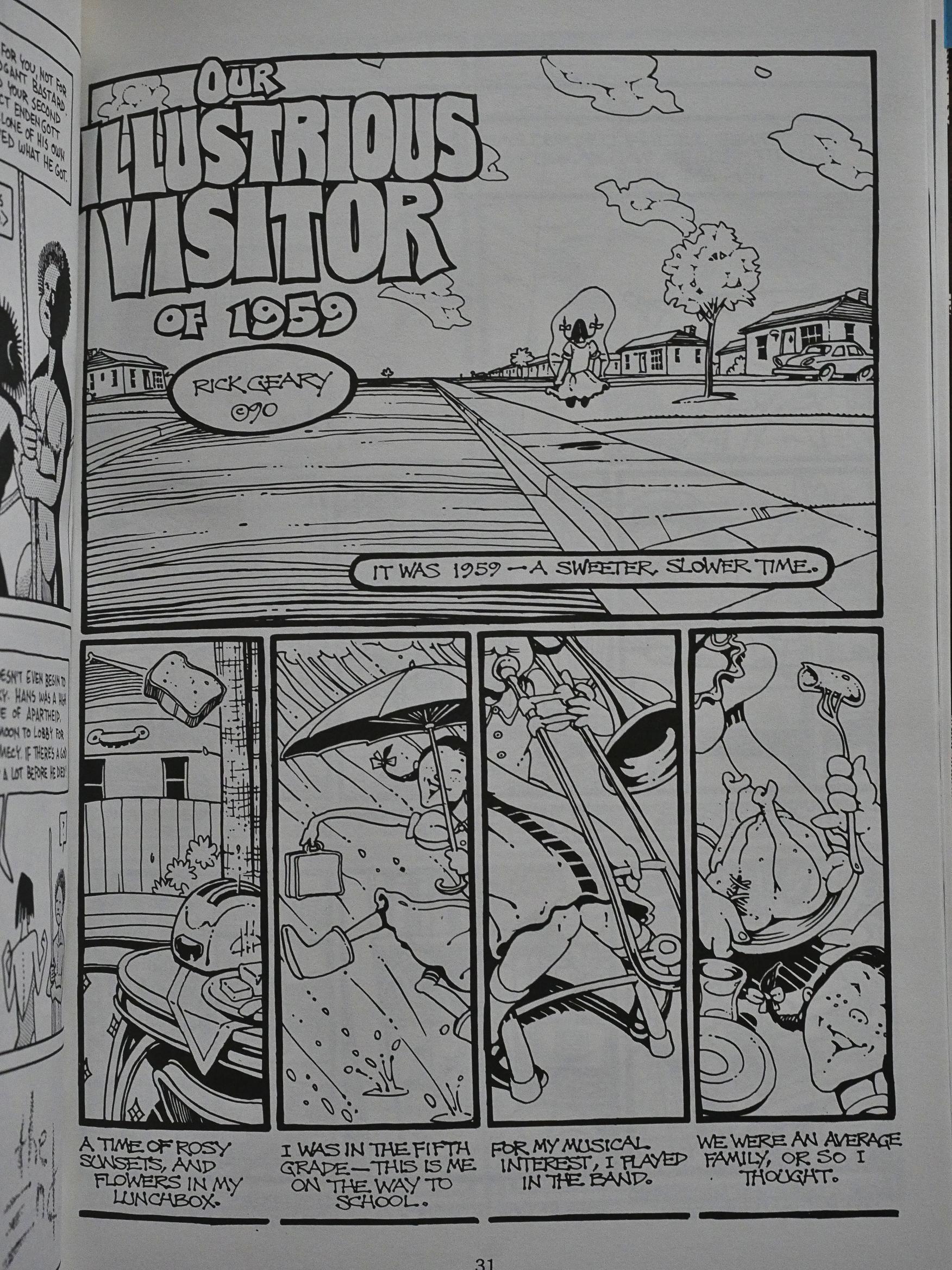

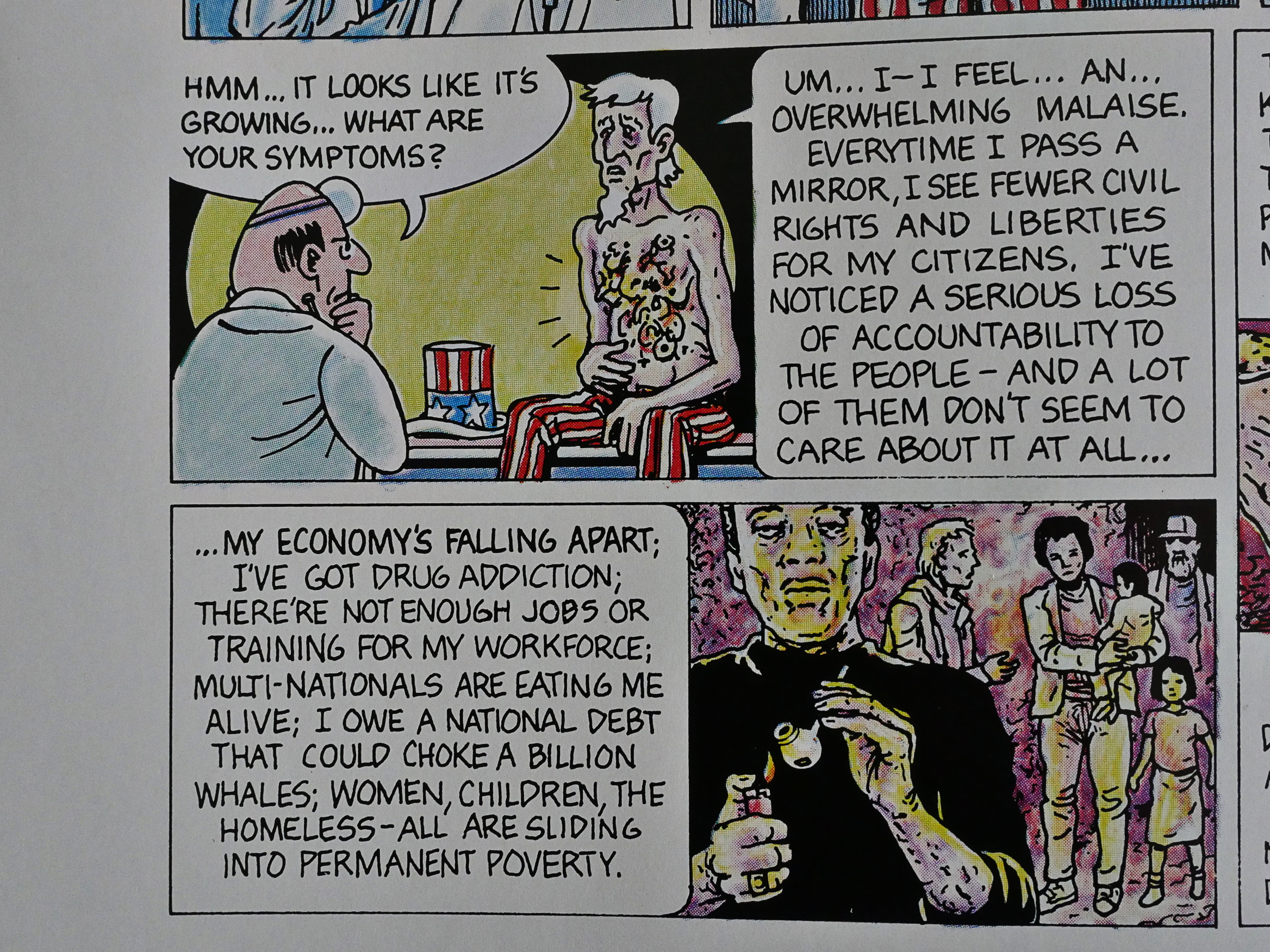

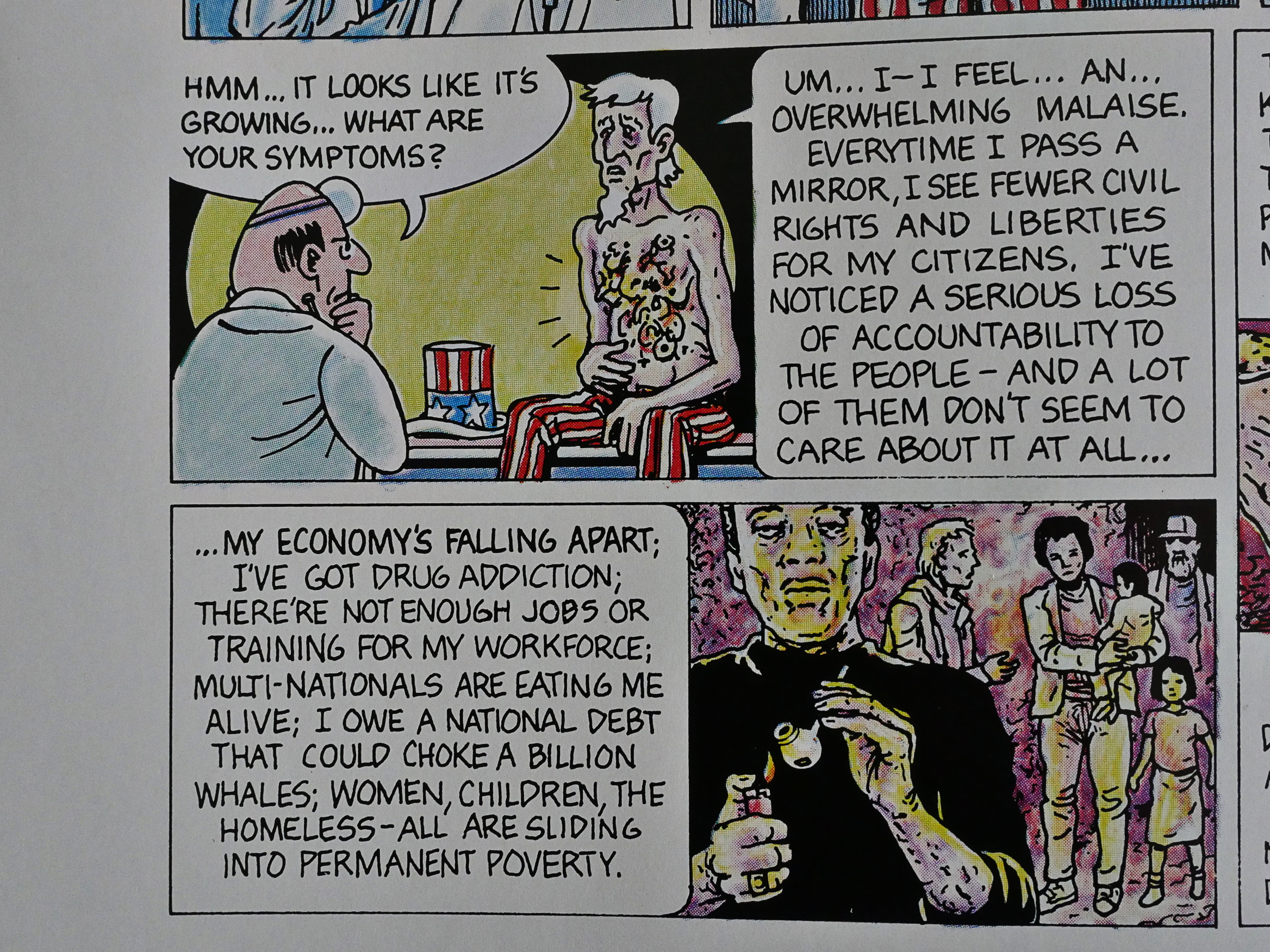

Between these two 30 page pieces, we have a two page strip by Paul Mavrides that uses the metaphor of an diseased Uncle Sam, and a doctor who tells him what he has to do to get better.

What was the reaction to the book? The Comics Journal 121 announces it:

This summer Eclipse Comics and Warner Books will simultaneously publish Brought to light, a comic designed to publicize the lawsuit brought against members of the CIA by the Christic Institute. The 64-page book will include two comic stories, one written by Alan Moore and drawn by Bill Sienkiewicz and the other written by Joyce Brabner and drawn by Rick Veitch. Eclipse will be producing a comic version of the project while the Warner’s version will be in book form.

The Comics Journal 124:

Although a federal district court in Miami recently threw out a lawsuit brought against several high-ranking memtxrs of the Reagan administration by the Christic Institute, Brought to Light, the comic book which tells the story of that suit, will be released as planned this fall, acording to the comic’s editor, Joyce Brabner.

[…]

“I have to keep rewriting the damn thing” as the case develops, Brabner said. Christies suit, brought under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO), charges that 29 individuals have engaged in a criminal conspiracy in South America that includes assassination, drug trafficking, and gun running. Individuals named include General Richard Secord, General John Siglaub, and financier Albert Hakim. Federal Judge James Lawrence King dismissed the case, maintaining that Christic had failed to establish its central premise, that a wide-ranging conspiracy, involving the persons named in the suit, was responsible for an assassination attempt against Contra leader Eden Pastora, during which eight people were killed by a bomb.

[…]

The lawsuit has also come under attack in the liberal press, with critical articles appearing in Mother Jones and The Nation. Brabner acknowledged that the writers made some valid points, but said Brought to Light was still important because “The purpose of this book is not to tell people how things are, the purpose is to raise questions.”

Oh. “To raise questions”, the first defence of any troll… That’s not encouraging.

The Comics Journal 125:

Warner Books has terminated its agreement to co-publish the controversial Brought to Light book with Eclipse Comics. Citing fears of vulnerability to libel litigation, Warner tendered Eclipse a cash settlement to remove itself from the project, Eclipse Publisher Dean Mullaney said. The move pushes publication of the Iran-Contra expose past the November elections and leaves Eclipse searching for a bookstore distributor. “The net effect is that the book will be released right around Thanksgiving rather than November 1.” Mullaney said. “But it is in production, the paper’s been ordered, and we’re currently set to go to press November 1.” Under the agreement, Warner was to distribute the 64-page book to bookstores while Eclipse offered it to the direct sales comics market.

Warner representatives refused several requests for comment.

[…]

“As to the background on why they pulled out,” Mullaney said, “one person at Warners — a lower-echelon person — said to me, ‘What would we do if George Bush wins?’ An executive at Warners told my brother (Eclipse partner Jan Mullaney) that it would be ‘unwise’ to go ahead with the book ‘given the current political climate.’ He didn’t say whether he meant at Warners or in the country — presumably both. Mullaney said he is “not exactly sure who put the kabosh” on Warner’s involvement, but that both companies had solicited advice from several libel specialists, as well as Warner and Christic Institute attorneys, at every stage of development.

[…]

Warner’s stated reason for its withdrawal , according to Mullaney and Brought to Light Editor Joyce Brabner, is that the July dismissal in Miami of Christic Institute’s lawsuit — a major source for the information related in the book — “changed the situation in regards to possible libel liability. ”

[…]

Lucas, who was promoted from Vice President of Marketing to Assistant Publisher after bringing The Dark Knight to bookstores, refused several requests for comment.

[…]

Shadowplay, by Alan Moore and Bill Sienkiewicz, details the 25-year history — as outlined in the Christie lawsuit filed in Miami on May 29, 1986 — of an American “secret team” Of military and intelligence that pursued political destabilization around the world in the name Of American “national security interests.” Of Warner’s libel objections, Alan Moore said: “I don’t know what your libel is, really. I’ve been given the facts and have tried to present them coherently. With a work of this complexity and density, there were some areas I misunderstood and we cleared those things up and I revised me script — and of course more information has come out and I’ve changed me script appropriately. ‘ ‘The script is based on material given me (by Eclipse and Brabnerl from the press and the Christic affidavit,” Moore said. “If those sources are true and accurate, then my script is true and accurate. ”

[…]

Yronwode speculated that Warner officials sought to disassociate themselves from the project because Of documented ties to organized crime, which has also been implicated in the Iran-Contra affair.

OK, it’s because Warner’s has a mob connection. There’s a whole sidebar on the connection.

This is a more fascinating publication history than most comics have!

But what did the critics think of it after it had been released? Here’s Andrew Dagilis from The Comics Journal 129:

Brought to Light is more than a snack. but still less than a meal. The cooks behind the dish have undoubtedly toiled long and hard in the steaming kitchen; their sweat drenches the pages. But for all their exhausting labors the end result falls far short of a feast.

[…]

For the rest of Sienkiewicz• art. arm yourself with patience and be prepared to scan some panels several times before you finally make out what’s drawn there. The same applies to some balloons.

It’s too bad, almost a shame. Considering how important is the story being told here, how hard Alan Moore worked to organize and present it. and how very good Bill Sienkiewicz can be when he decides to serve the materlal more than his own artistic fancies. one wishes the end result cohered better. As it is, Shadowplay tells an ugly tale with a surprising amount of ugly art.

[…]

In trying to fit it all in (what happened. what was said, what was felt, what’s the historical background) Brabner jerks the reader around too much. Bit players appear and disappear, faces come and go after uttering one Or cryptic word balloons, dates change without warning… the story’s component parts never lock together in a solid whole but instead seem to lie there in a barely-connected jumble.

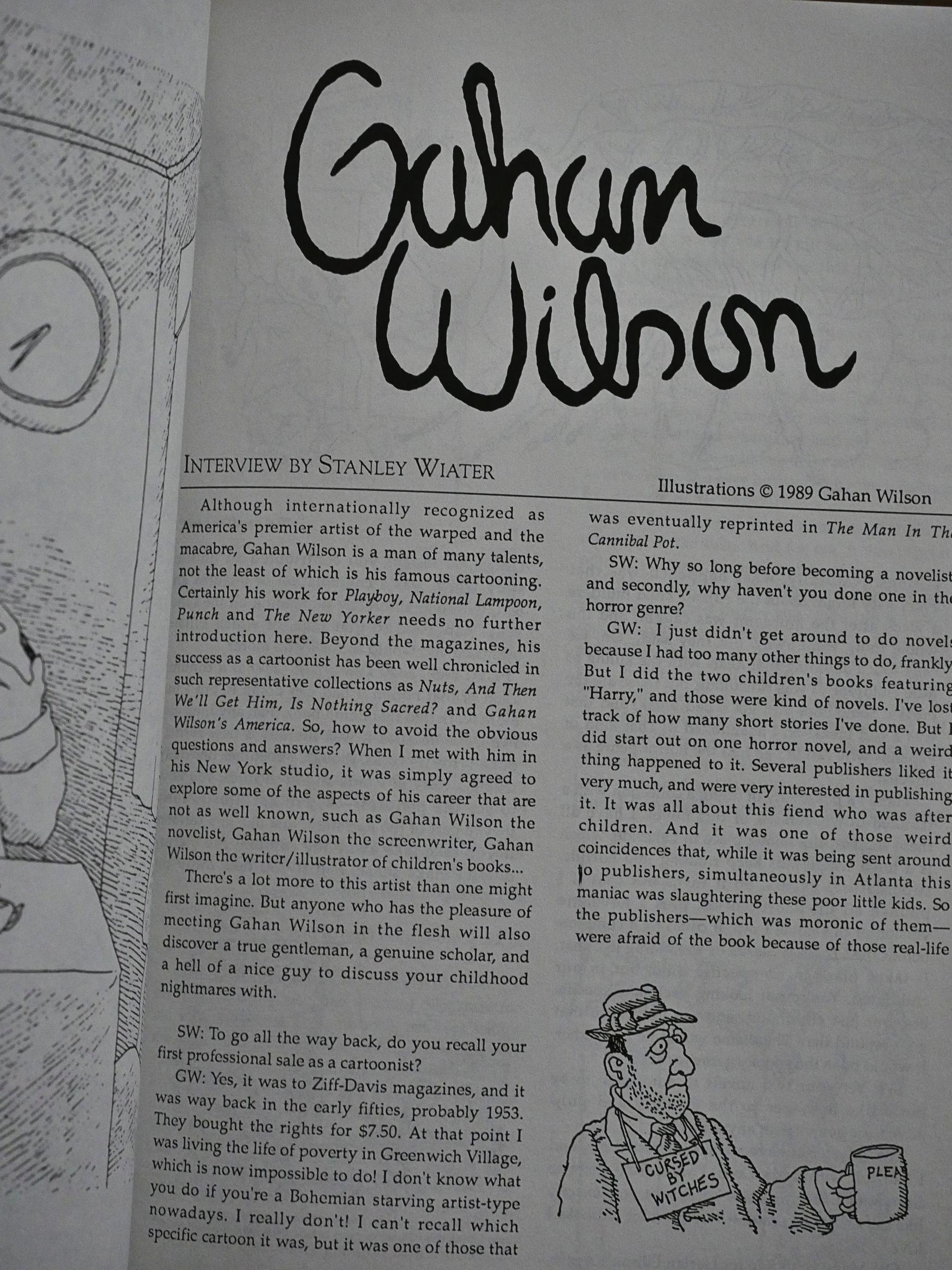

Oh, my, I have to include this bit from an interview with Moore in issue 140:

GROTH; I assume they just let you loose on the CIA and that was it.

MOORE: Joyce did provide all the reference I needed and pointed us in which direction to take the strip in the initial stages, and then they turned us loose. I vas very, very pleased with Brought to light; it’s one of my favorite works so far. I was thrilled with what Bill (Sienkiewiczl had done with it.

There was a review in the Journal #129 which praised me but criticized Bill for going too wild with the illustrations. I feel that I should take this opportunity to put matters straight in that most of Bill’s wildness was called for in the script.

Bill was only doing what I asked him to do a lot of the time. Some of the things that looked like the wild, orgiastic flights Of fancy that Bill might be known for were, in fact, directed by me. That’s not to downplay Bill’s contribution at all because he did bring those ideas to life with such verve, and there were some things in there that were purely Bill’s. However, the majority of the wilder visual directions were down to me, so I should accept my share of the blame for that, if there was anything wrong with them. For me they worked perfectly.

I wish the work had been seen more. I wish that it had gotten more coverage. There were national papers and magazines avoiding reviewing Brought to Light, not because of its quality, but because the time wasn’t right politically. It was just before or after the elections; Bush had just got in or whatever and there was the new “up” mood in this “kinder and gentler” America. Brought to Light seemed a bit downbeat and spoilsport. Was there an injunction against it in America?

GROTH: I don’t believe so, no.

MOORE: Maybe that was just a rumor over here. I know that Smith’s (an English bookstore chain) over here refused to stock it. They pulled it after unidentified complaints from unidentified people, that it showed how to make a Molotov cocktail. This was, in fact, one of the bits where we were reprinting a CIA manual that they handed out to Nicaraguans. I suppose the moral is that it’s OK to tell brown people how to set fire to themselves but not OK to tell white people how to set fire to each Other.

GROTH: That’s a reasonable interpretation, I think.

MOORE: On the other hand, there was some interest in it over here. It got covered on a couple of media programs and there was an excellent stage play performed from it. It was not very widely performed, but the performances that I saw were excellent. It was a guy named Phil Judge from a pop group over here called “Morris Minor and the Majors” who’s also an actor. He did it as a one-person monologue, which is basically what it is. It was chilling.

As for the lawsuit by the Christic institute, which is where this material was adapted from:

It was the liberal magazine Mother Jones that first raised serious questions about Daniel Sheehan’s theory. In a harsh take-out last winter, writer James Traub suggested that the Christic lawsuit was a “gorgeous tapestry . . . woven of rumor and half-truth and wish fulfillment” and that Sheehan was a man “in whom passion has overcome reason.”

And somebody has edited Wikipedia to say:

Writing for the Columbia Journalism Review, Chip Berlet described the Christic Institute as “something of a rarity among advocacy groups: starting out on the left of the political spectrum, over the years it was drawn into the conspiracy theories woven by the radical right.”

I can’t really find anybody doing a dive into the material in the Brought To Light book, though, to point out what’s supported and what’s not.

I’m guessing: Most of it. There.