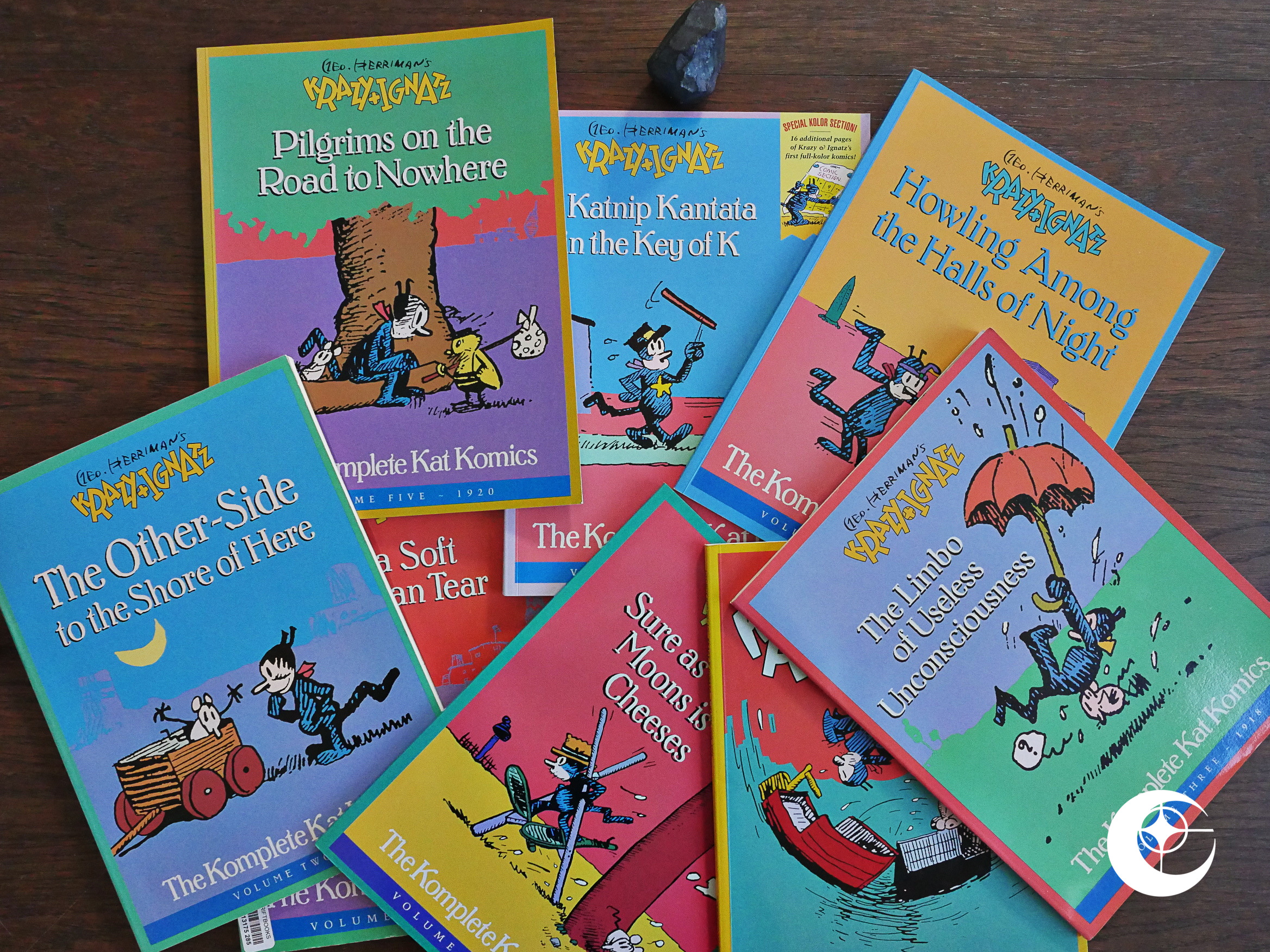

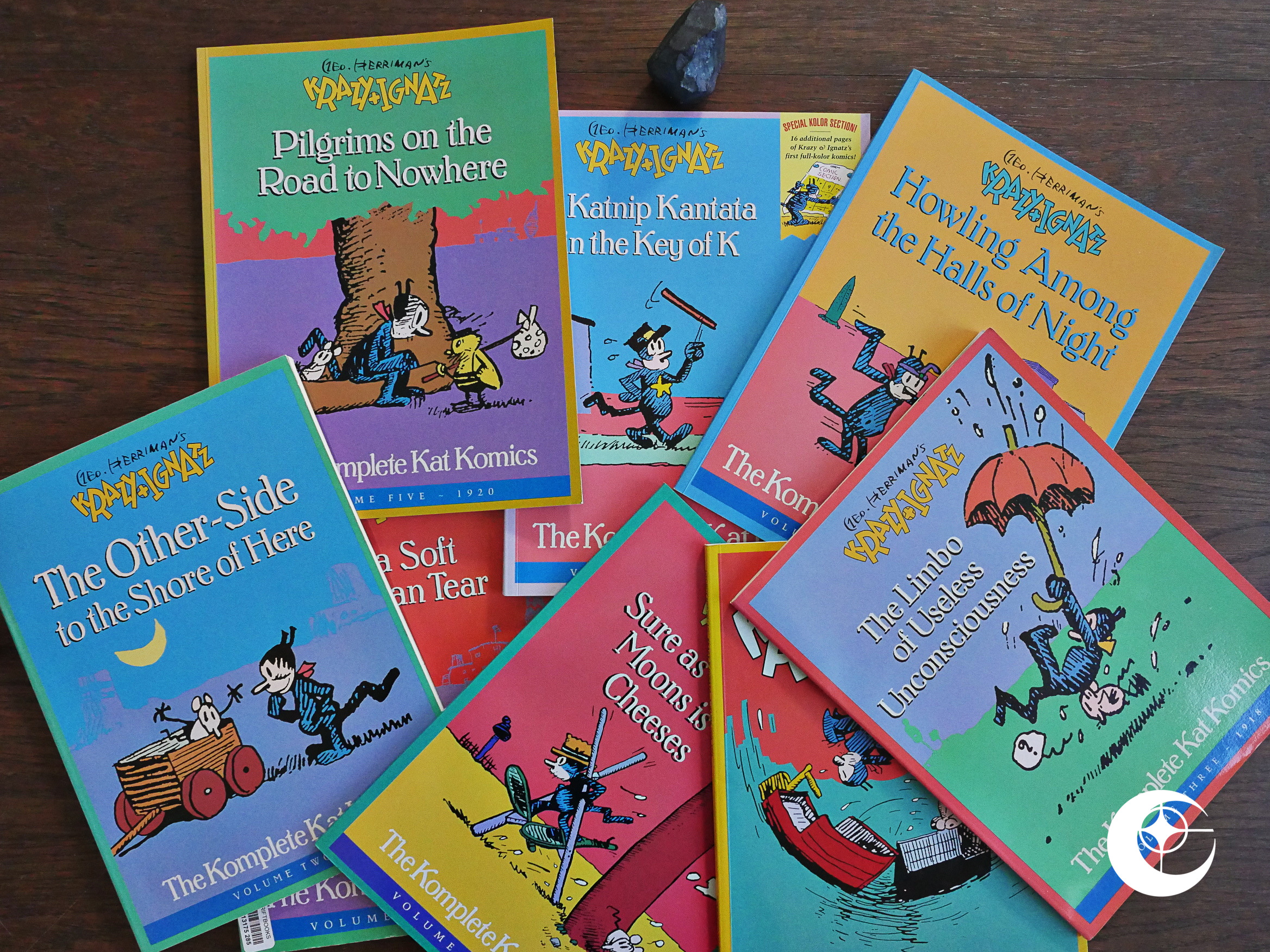

Krazy & Ignatz: The Komplete Kat Comics (1988) #1-9 by George Herriman.

Well, you can’t say that Eclipse didn’t reprint a lot of crap, but then they go and make amends by trying to do a substantial reprinting of the Krazy Kat Sunday strips. We’d seen some lethargic attempts at getting this, the best comic ever, back into print before, but Eclipse managed to do nine whole years worth, which is probably nine times as much as anybody else had managed until now.

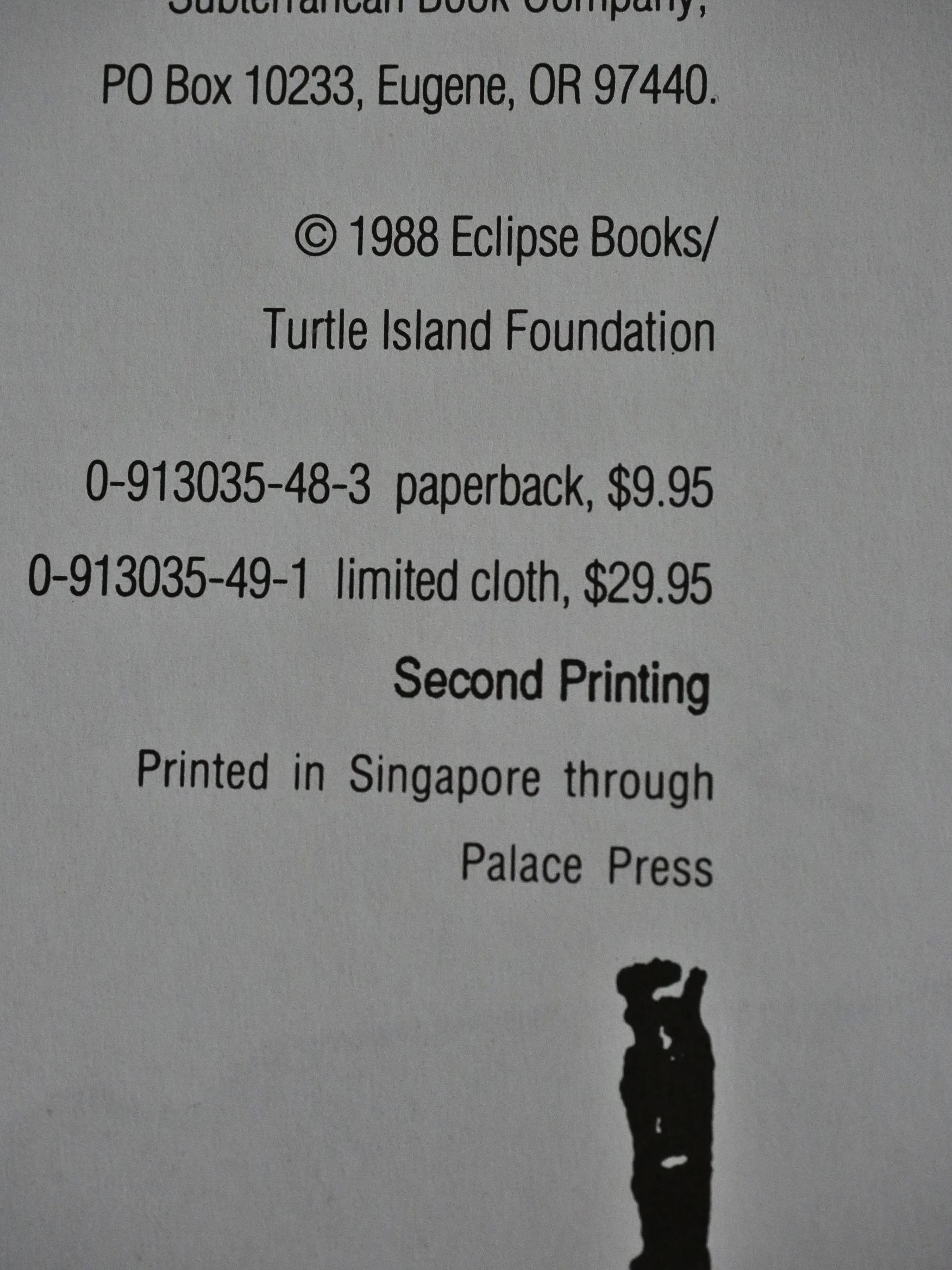

And it was apparently something of a success? The first volume, at least, went into a second printing, and Eclipse kept doing them until they went under, more or less…

Anyway, there are more essays and books about Krazy Kat than just about any other subject in comics, aren’t there? I bought the latest two books recently, but I haven’t read them yet, so my feeling about the field is out of date.

But every time I read an article about Krazy Kat in the 80s and 90s, are that they try too hard to pin the work down. “This is what Herriman meant.” “This is Herriman’s theme (singular).” “This is what it all means.”

Even sensitive and intelligent writers like Austin English falls into that trap, I think, but doesn’t get stuck.

It’s like reading reductive books on your favourite album. “This song is about the singer picking his nose.” It’s wonderful reading books that gives you lots of background information about how the record was created and what the author was going through; that open up the interpretative options, not close them down. I remember Jonathan Lethem’s book about Talking Heads’ Fear of Music fondly in that regard.

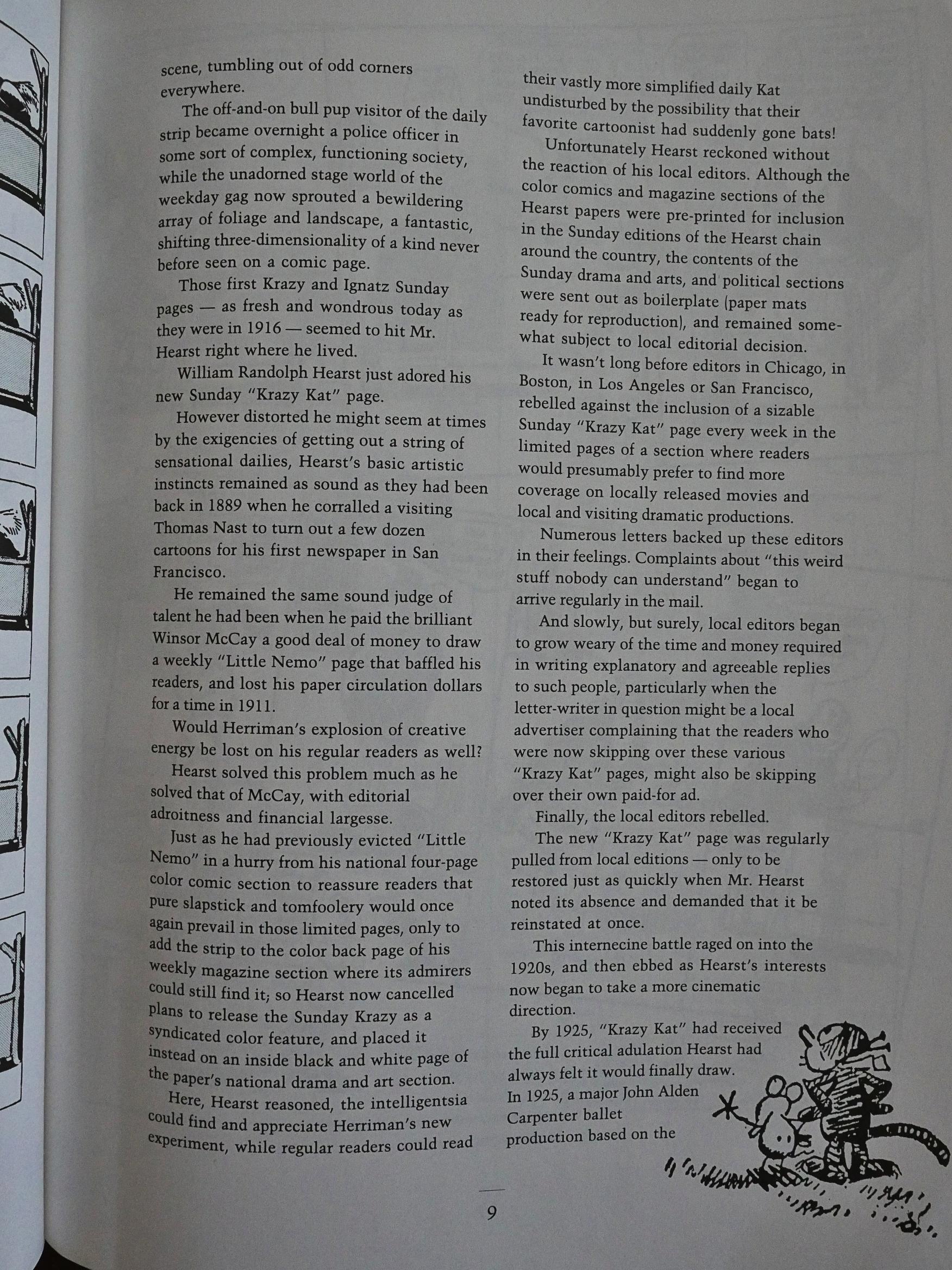

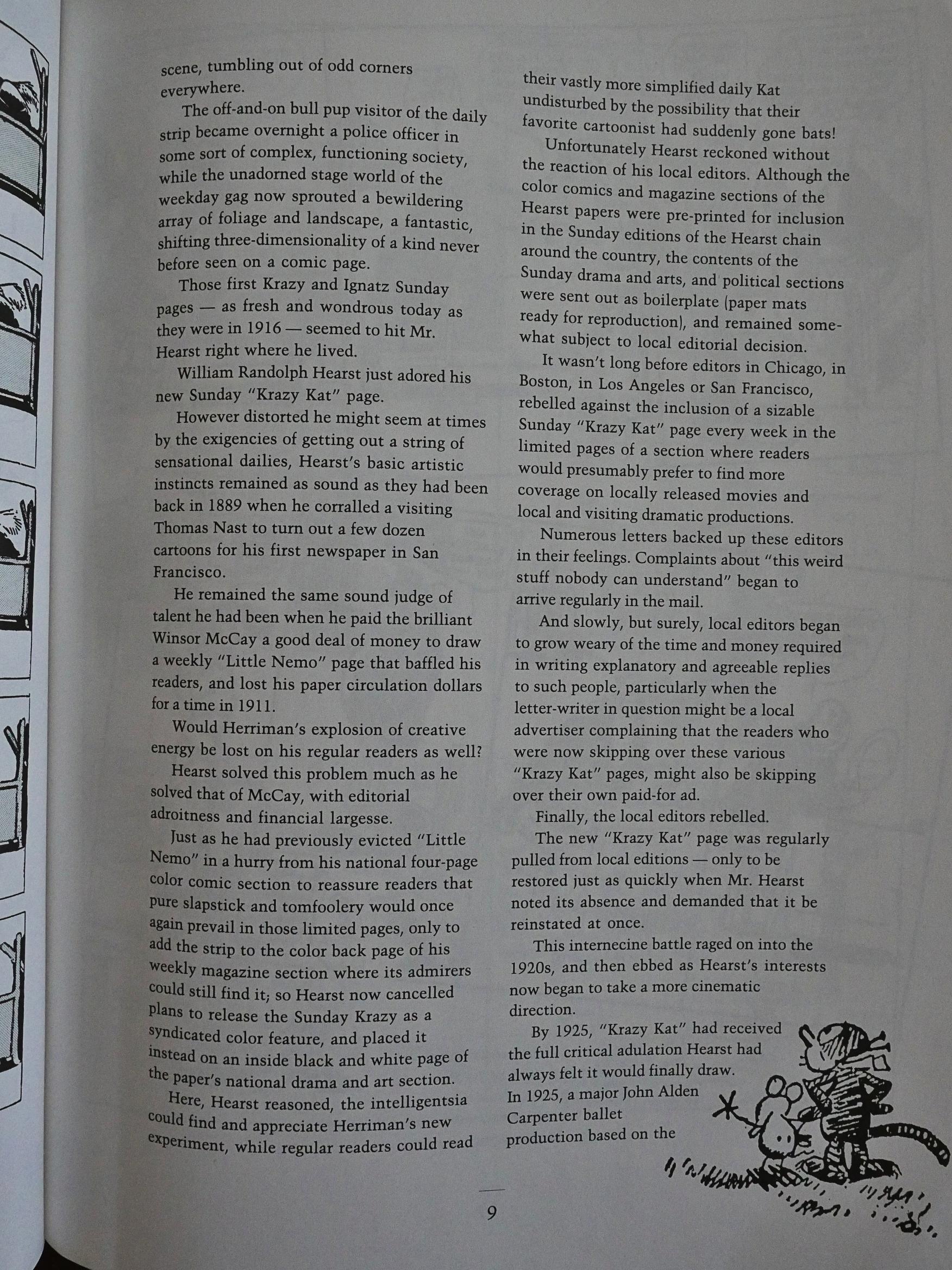

Editor Bill Blackbeard provides the introductions in these volumes, and gives a bit of context, but he mainly says 1) we don’t know anything about Herriman, and 2) William Hearst had to cajole the editors of this newspapers to keep them running it. Blackbeard’s explanation for they didn’t want to run it was that (basically) that it’s baffling. The readers wrote in and were upset with all their general confusion.

He doesn’t provide any examples of the general bafflement, and reading these early strips, I think there may be a reason why: These strips are clear, easy to read, and very logical. The reason the editors wanted to be rid of the strip may perhaps not have been because they didn’t understand it, but because they understood it all too well.

It’s a strip about Krazy Kat (presented always, in these early years as “he”, “nephew” and all the other male words in the lexicon) in love with Ignatz (demonstrably male; with wife and children), who alternates between loathing Krazy and loving him (but only when nobody’s watching).

Could it possibly be that the editors (and readers) reacted negatively because *gasp* IT”S ABOUT TEH GAYES!

No, of course not. It’s because it’s too “highbrow”, as Blackbeard puts it.

*sigh*

But if that’s the reading the people a hundred years ago gave these strips, it may or may not have been what Herriman intended. After a few years of people asking him what gender Krazy Kat is, he’d go on to say that Krazy is sexless, a “pixie”.

I remember, with horror, articles from the 90s where people had gathered seemingly every panel where Krazy Kat had done something particularly effeminate, or somebody had called Krazy “she” and wrote “here’s definite proof that Krazy is female!!1!ONE”.

Or to put it even more moronically, here’s RC Harvey for

instance:

(Despite refusal to assign a gender to his title character, I use the feminine pronoun because Ignatz is clearly male, and a female-male love relationship — while perhaps too conventional for the whimsical

unconventionality of the strip — was not so untoward as to disturb Herriman’s first readers, crossspecies implications to the contrary notwithstanding, and so most of them doubtless thought of Krazy as being

female. Why shouldn’t we?)

“Doubtless.”

People are amazing. Sometimes horrifyingly so.

And I’m sorry for that rant, because Herriman is somebody who plays with everything, anything, for a laugh, like this guy who apparently laid an egg after eating Mexican jumping beans. Herriman can’t be reduced or pinned down, ever, but being obtuse to this degree (about other people’s reaction to the work) is really annoying.

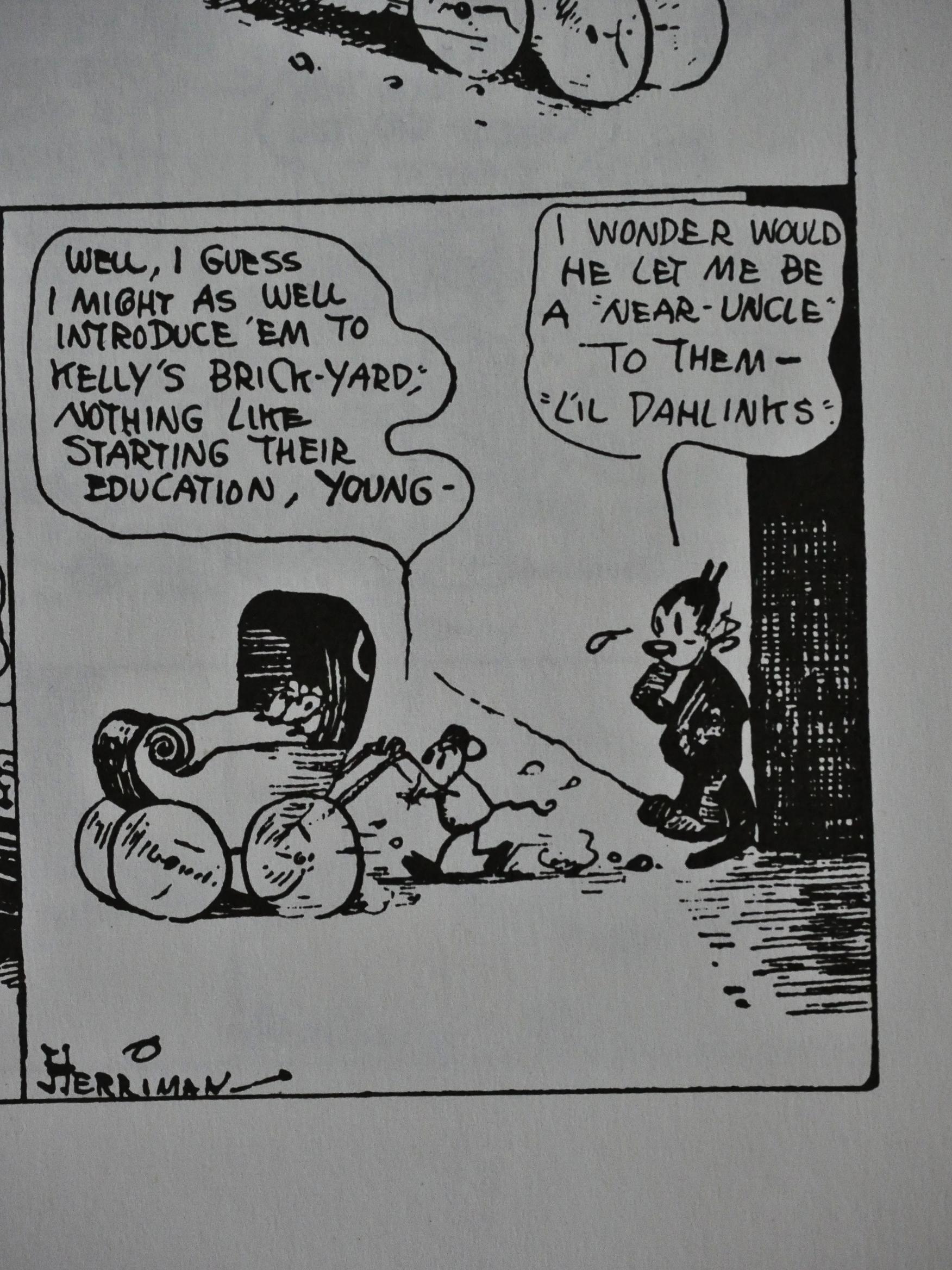

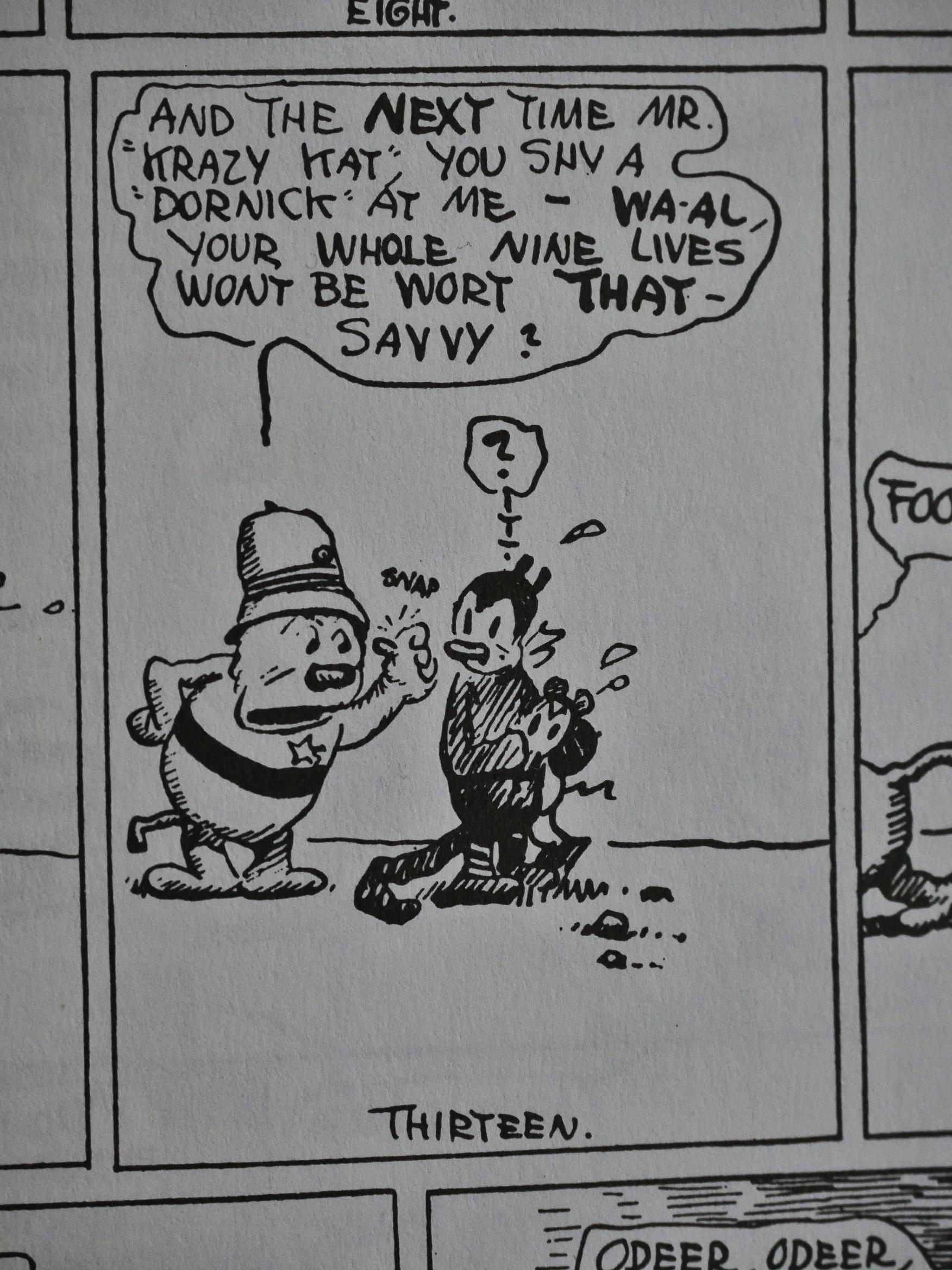

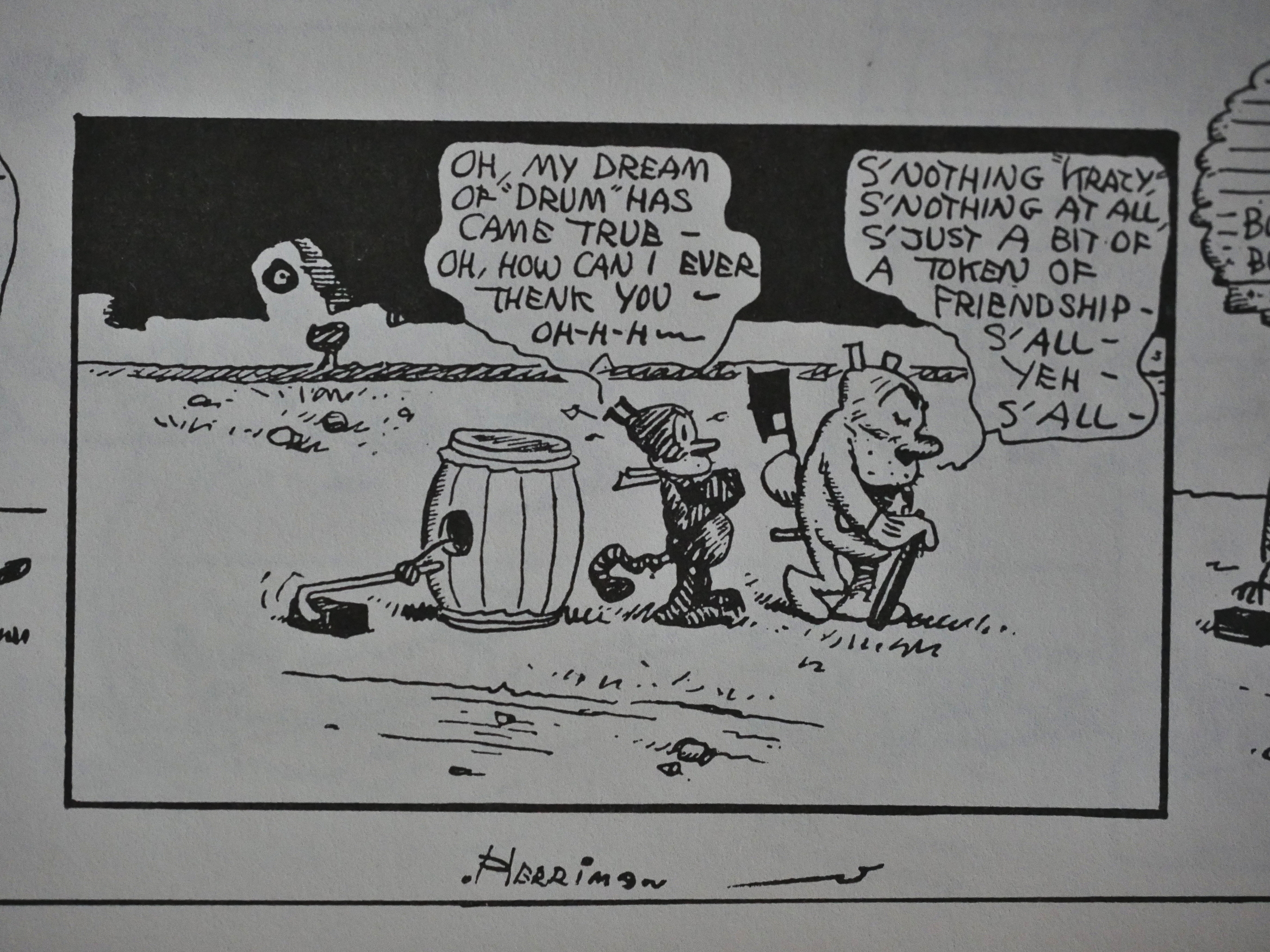

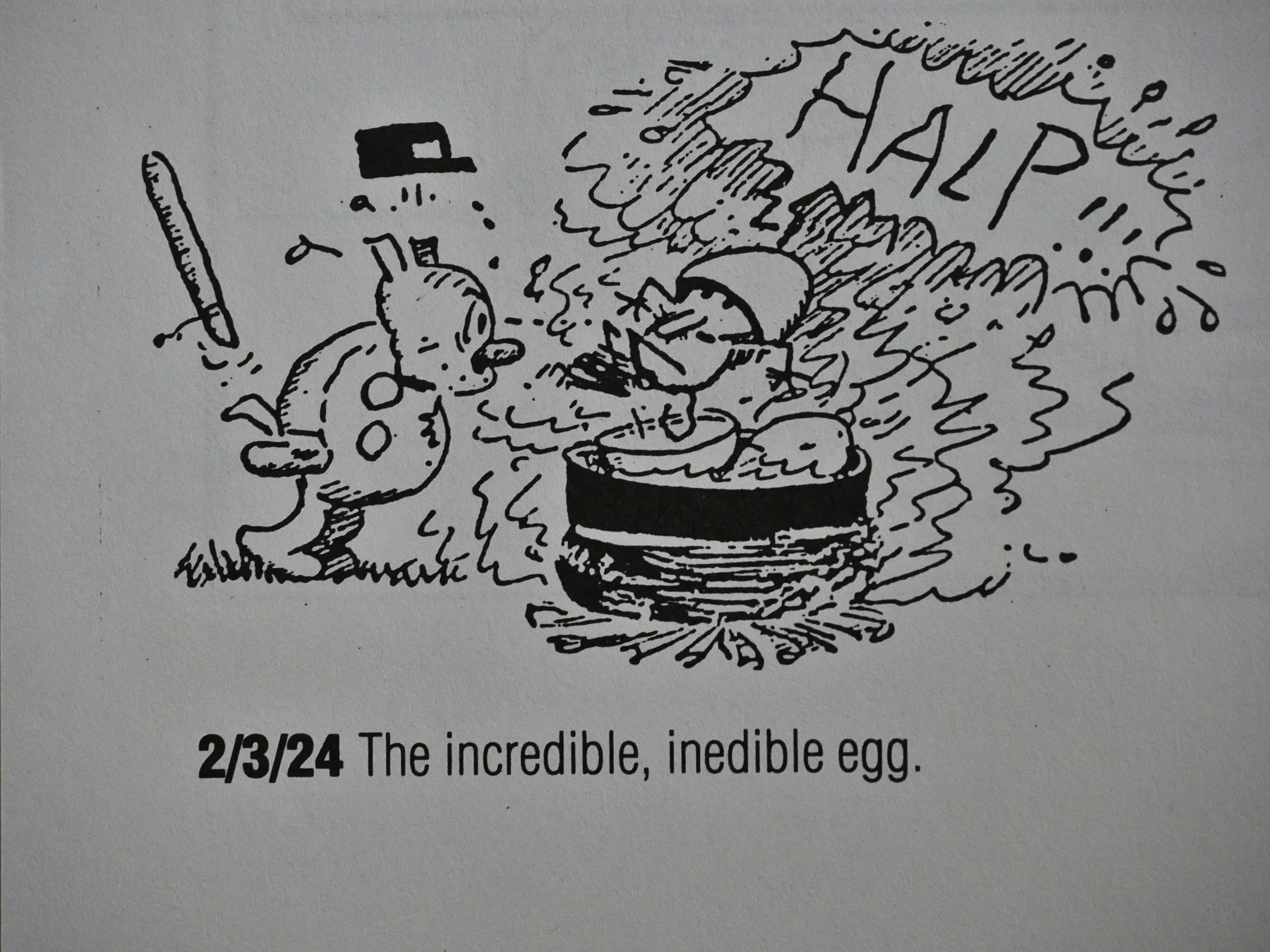

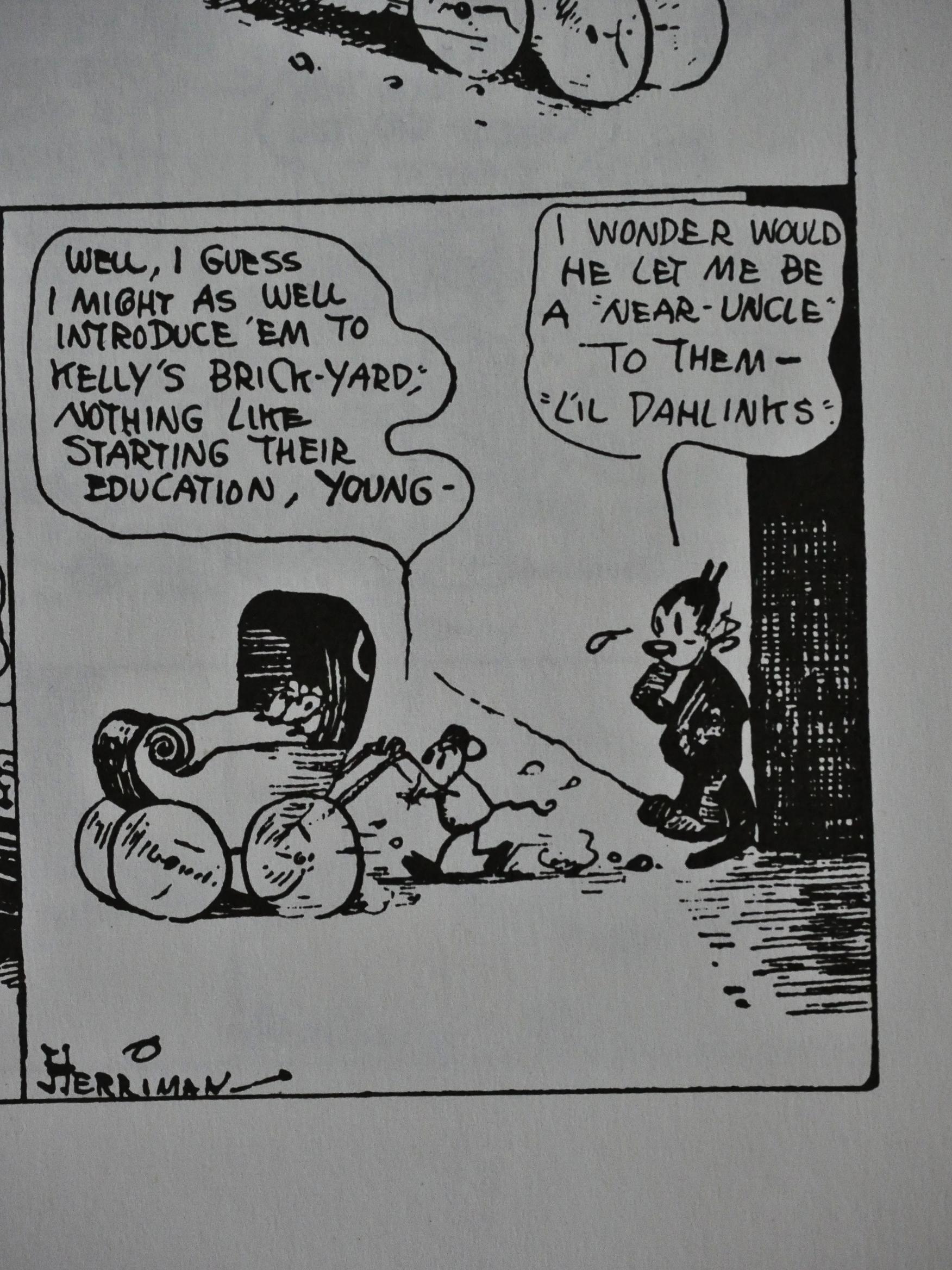

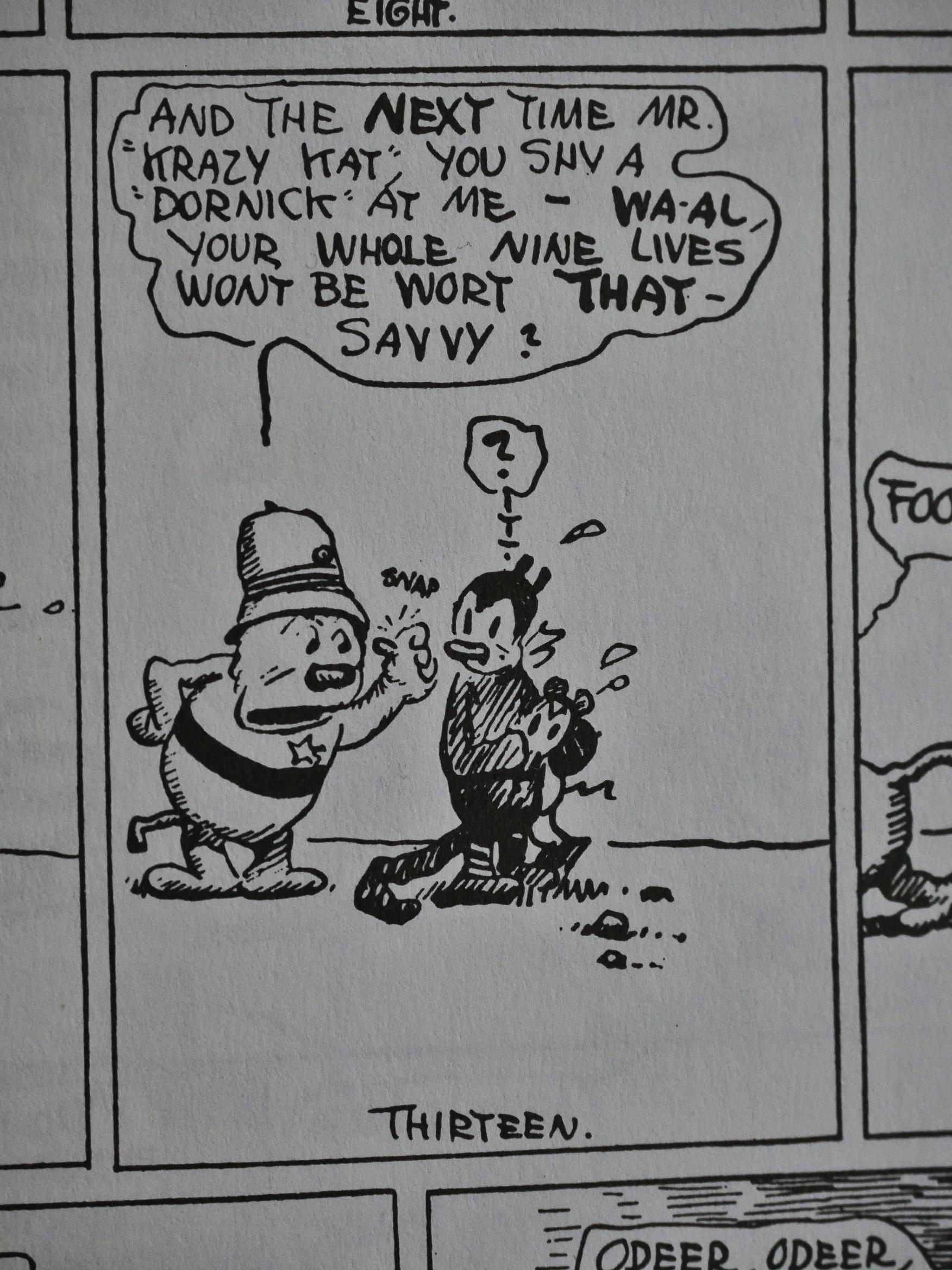

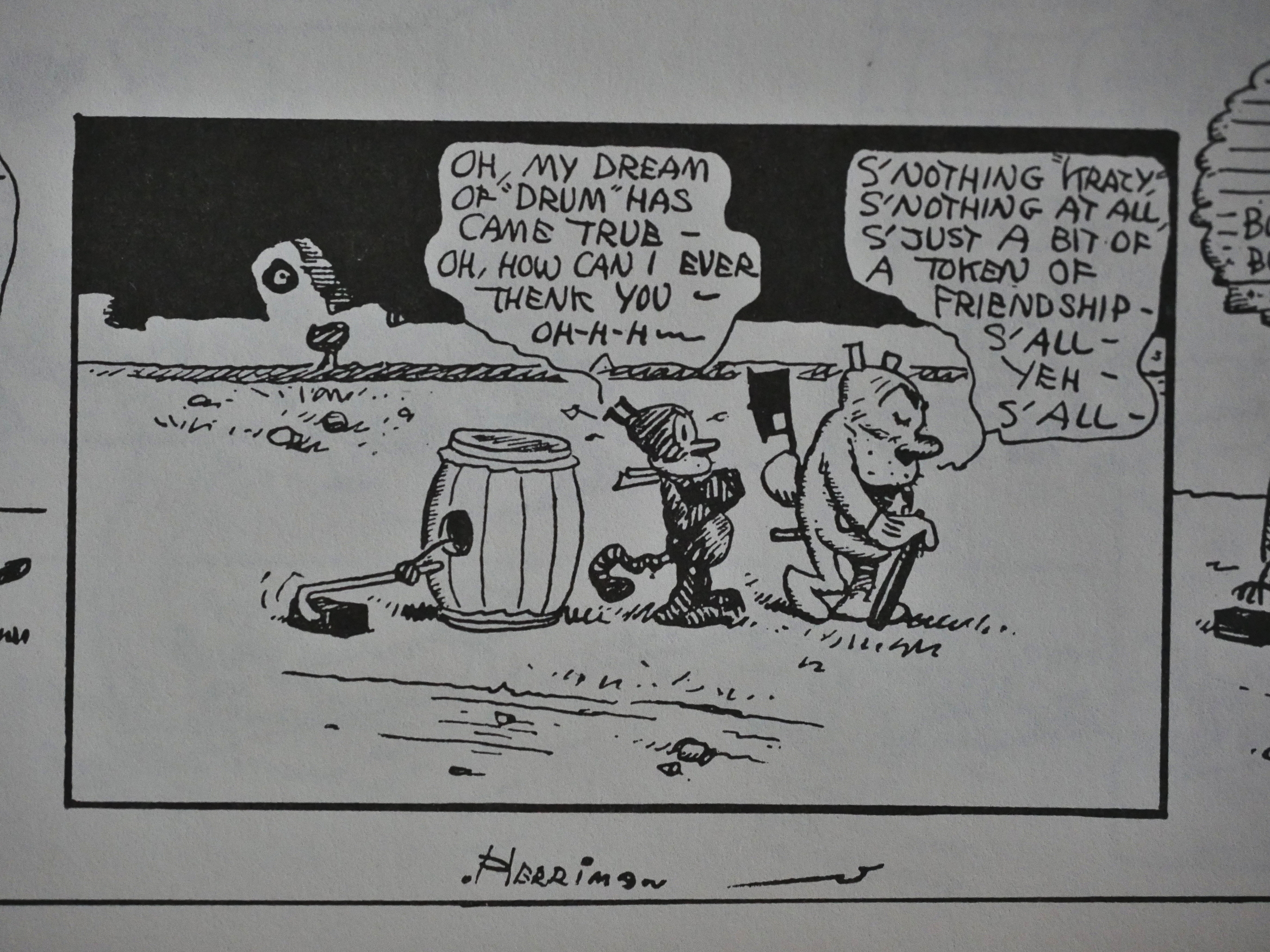

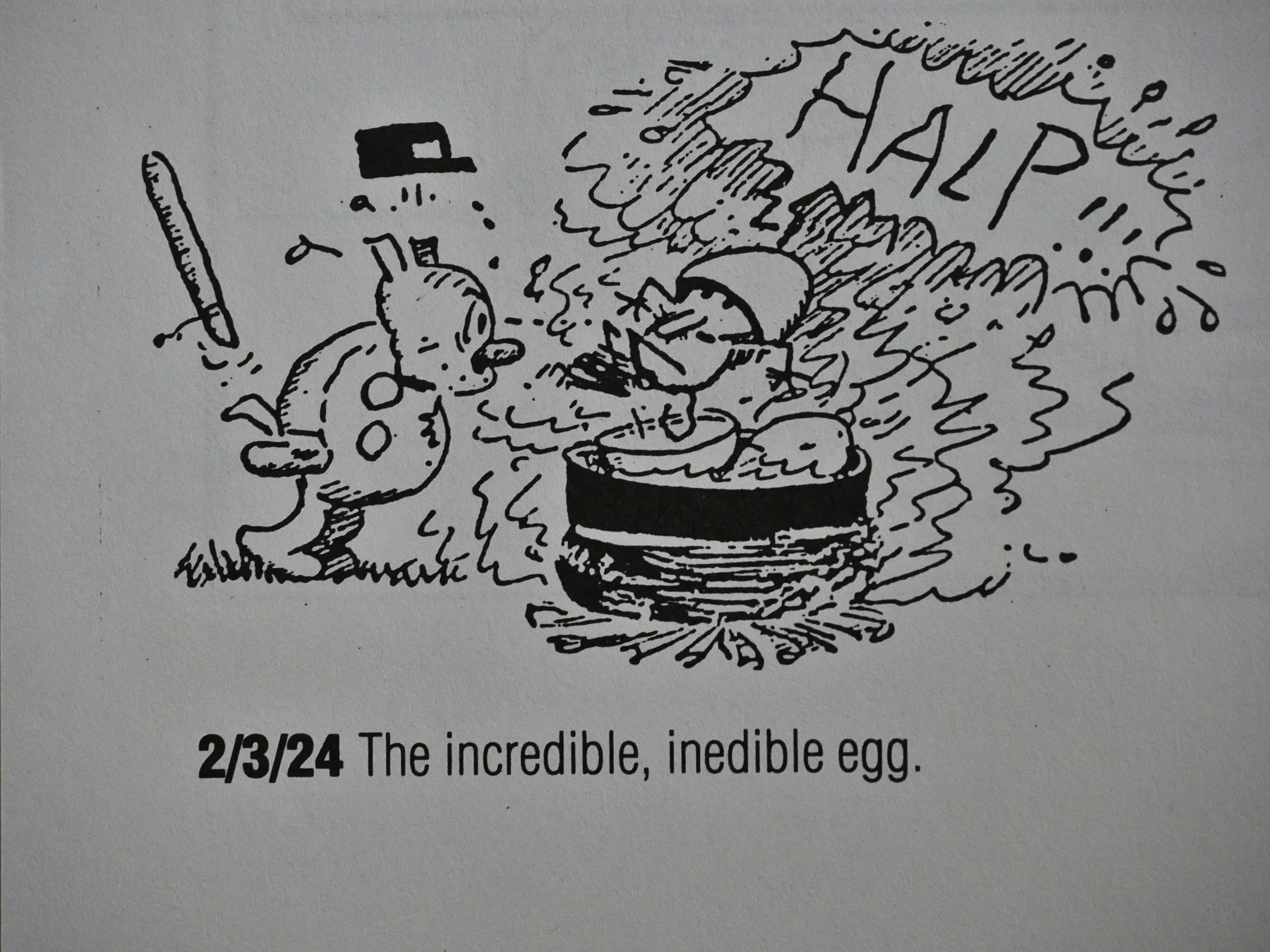

So let’s talk about other things! Like how Ignatz is really creepy in these early strips. I’ve read all the Sundays (as Fantagraphics were publishing them in this century), and they pick it up around 1926. Here, ten years earlier, he’s much nastier than I remember him being in the strips I’ve read more recently. Above he’s conspiring to eat a bird’s eggs while she’s away, having placed Krazy Kat in charge.

And there’s no sign here of how infatuated Offisa Pup would become with Krazy Kat: He barely tolerates Krazy in these strips.

In my mind, the central cast of the story are constants, but it’s really only Krazy Kat who remains the same throughout the series. And a lot of important, but peripheral characters, like Krazy’s aunt Tabby, go missing.

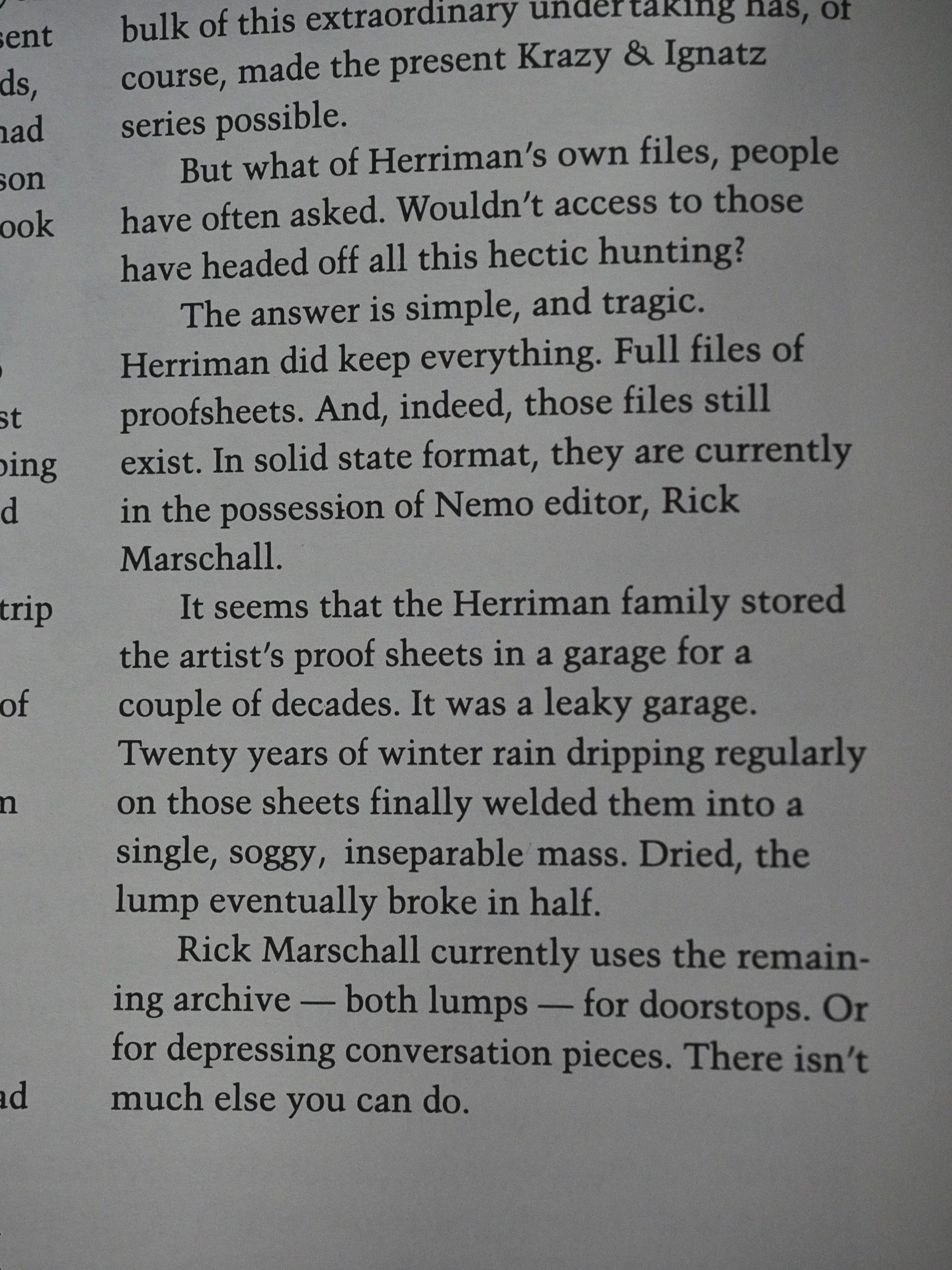

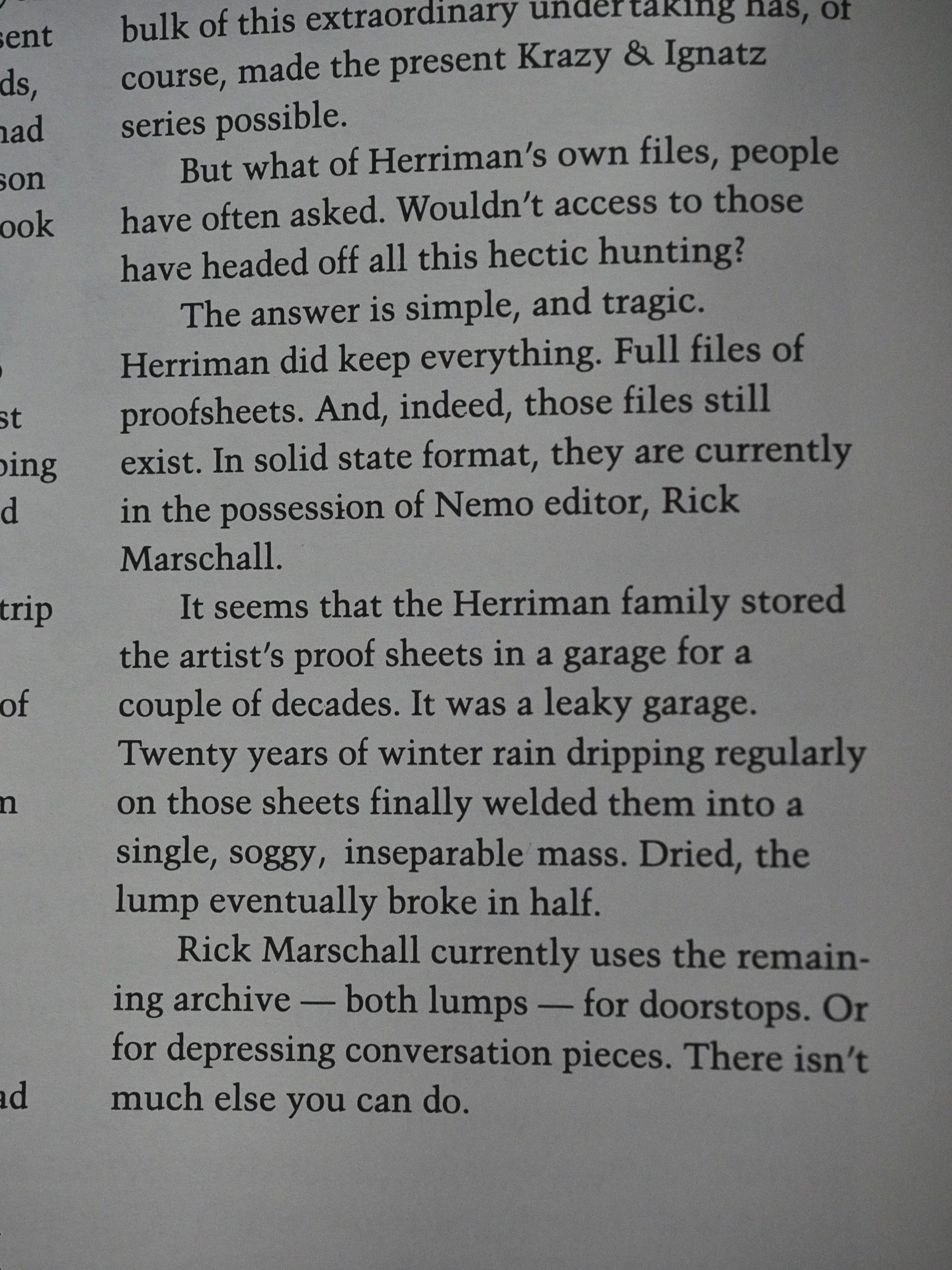

Blackbeard recounts the sad, sad story of what happened to the original proofs (the family put them into a leaky garage and they turned into a block of paper) and why this series is reproduced from newspaper printings. But I vaguely recall something about this now being quite accurate any more? Googling for half a minute doesn’t turn up much, though.

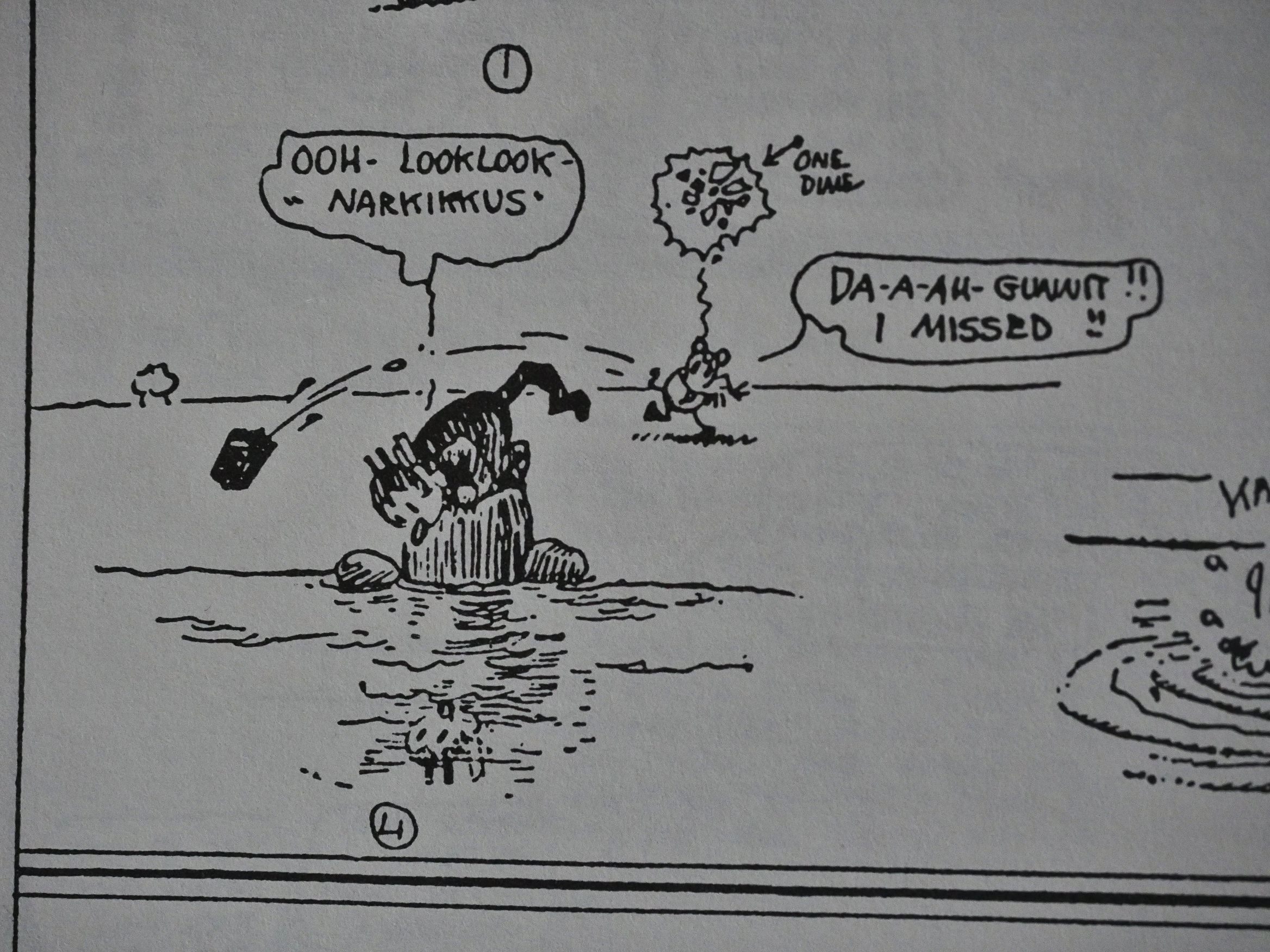

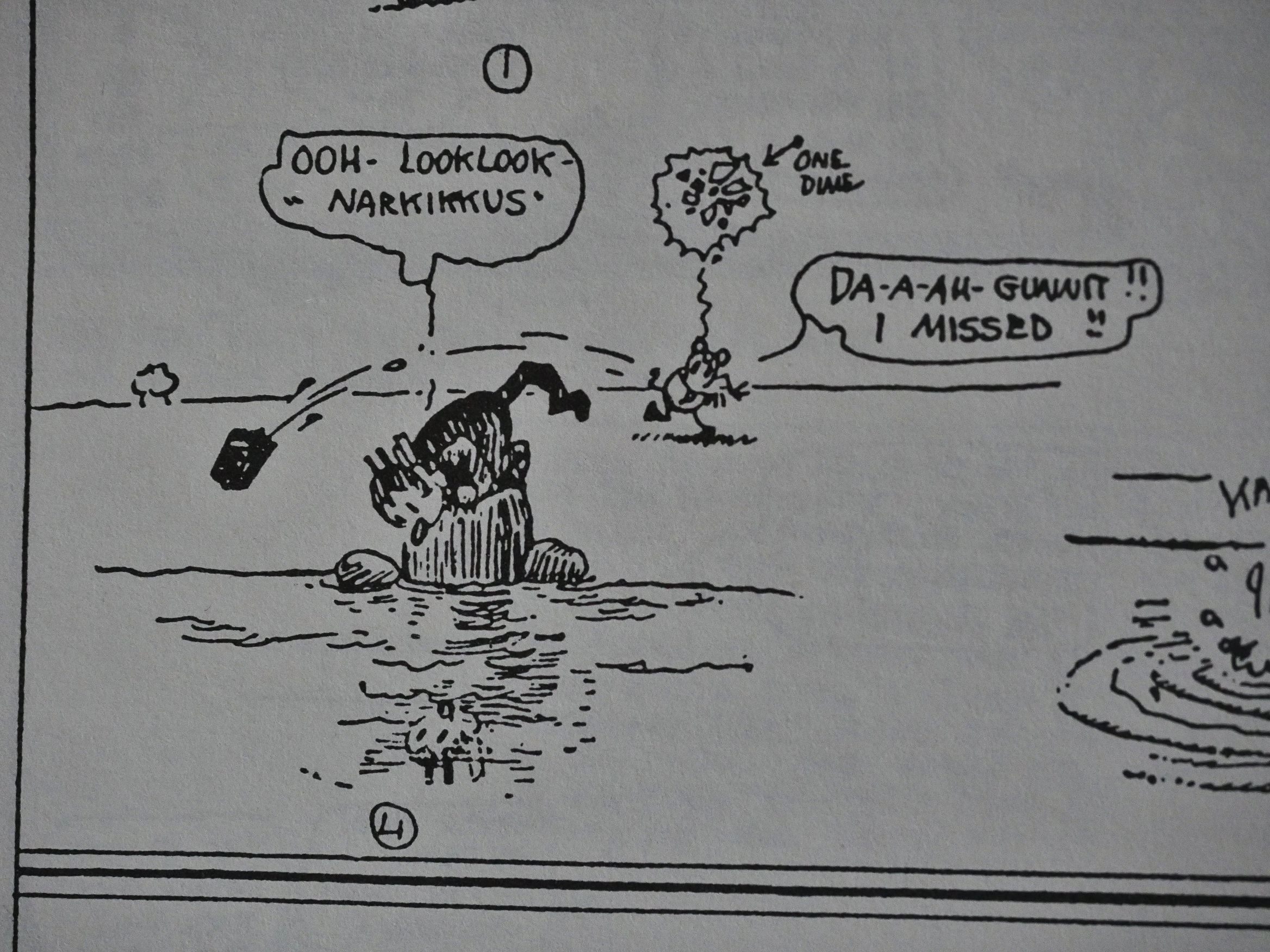

Blackbeard is right in that there are some “highbrow” things in here. Would most Sunday paper readers get the Narcissus reference? I think perhaps more than you’d expect…

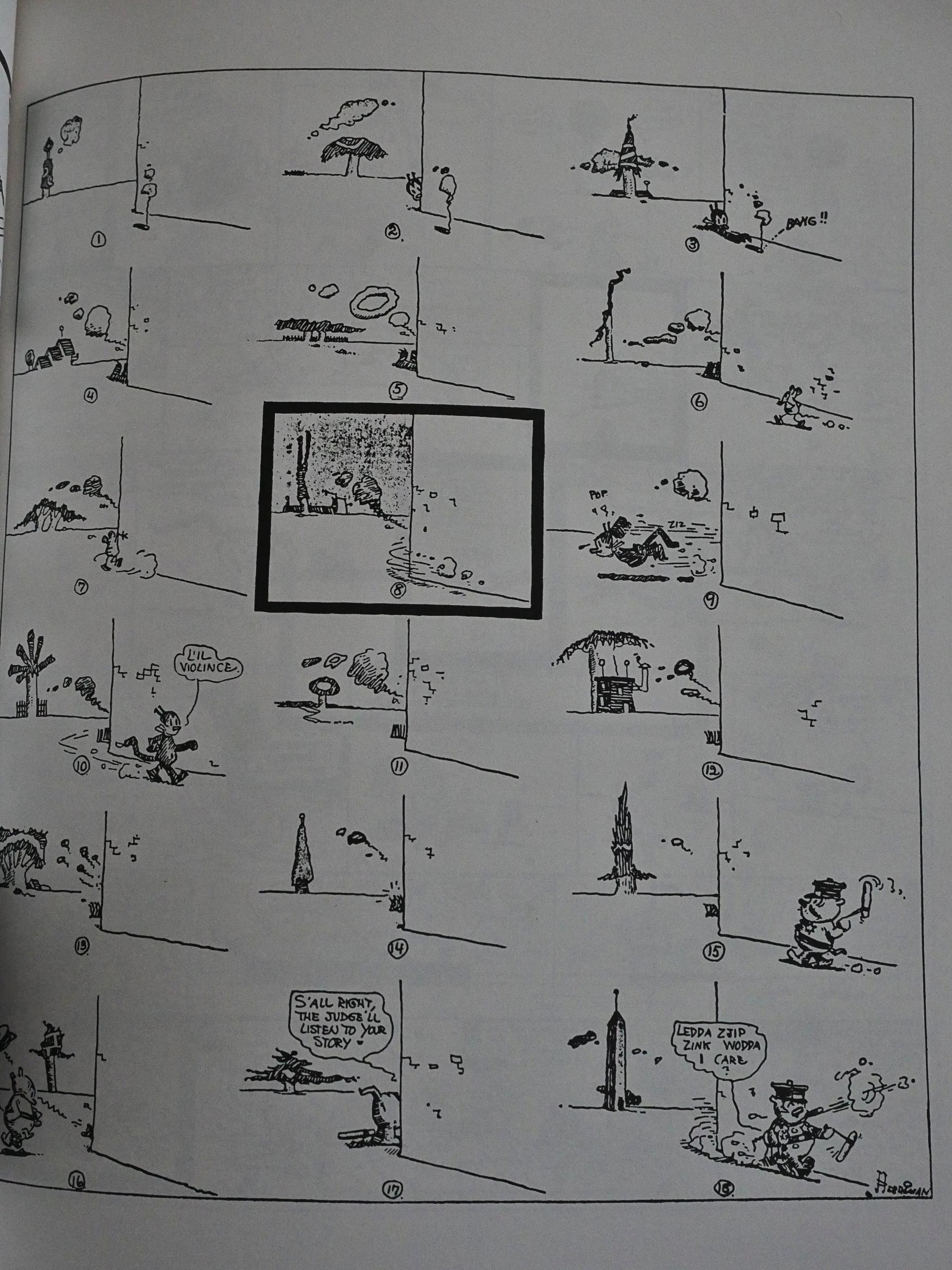

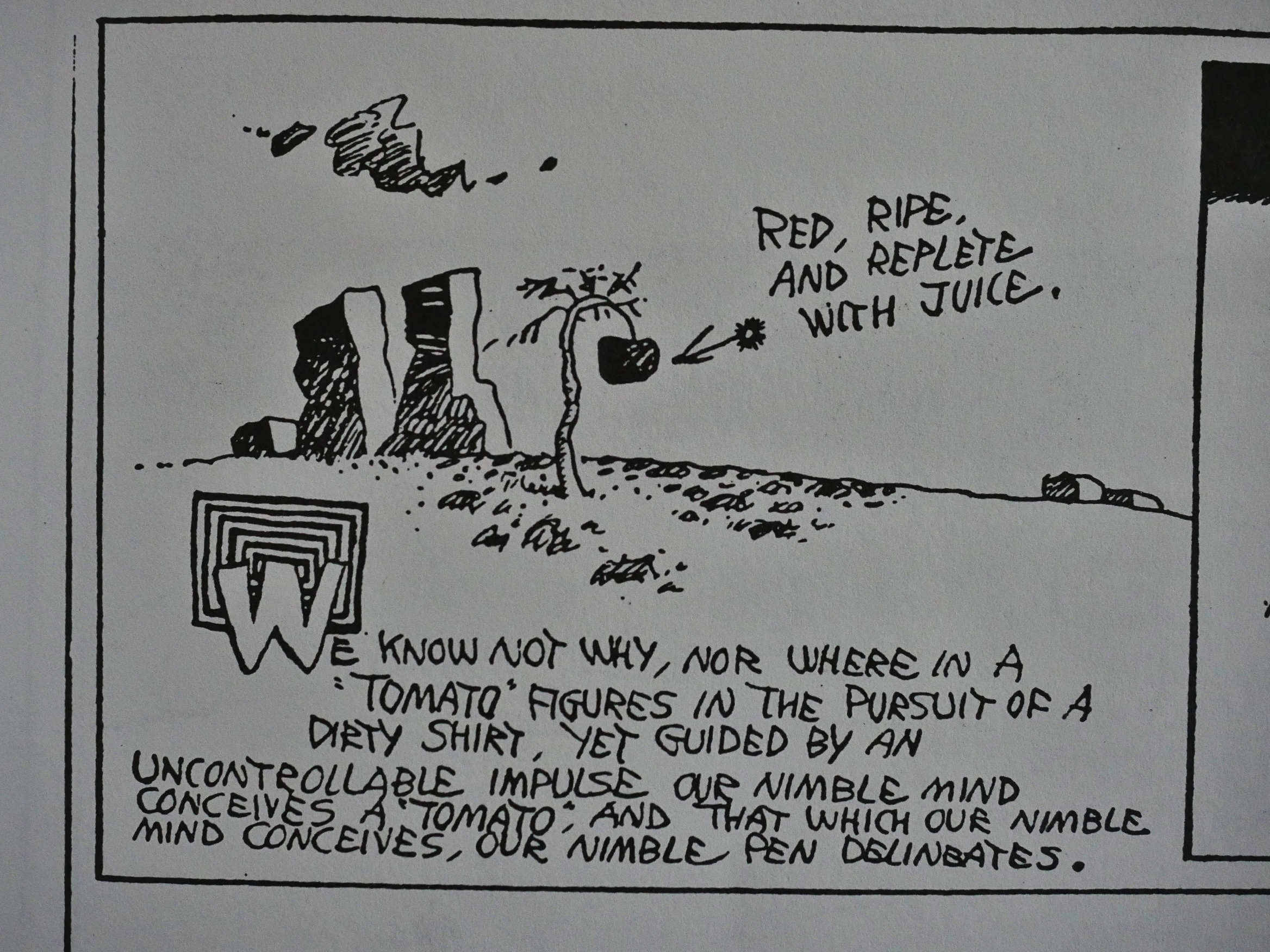

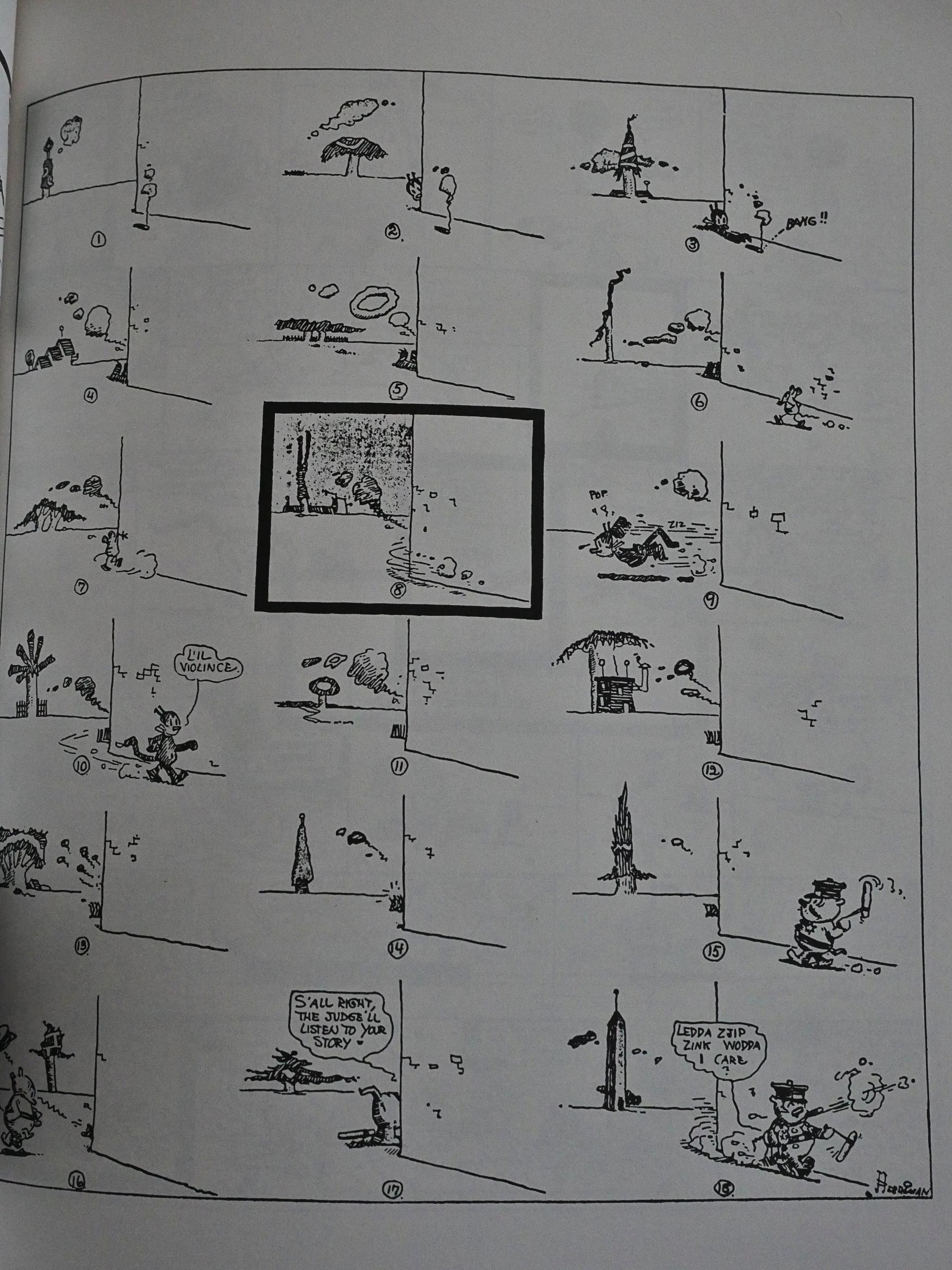

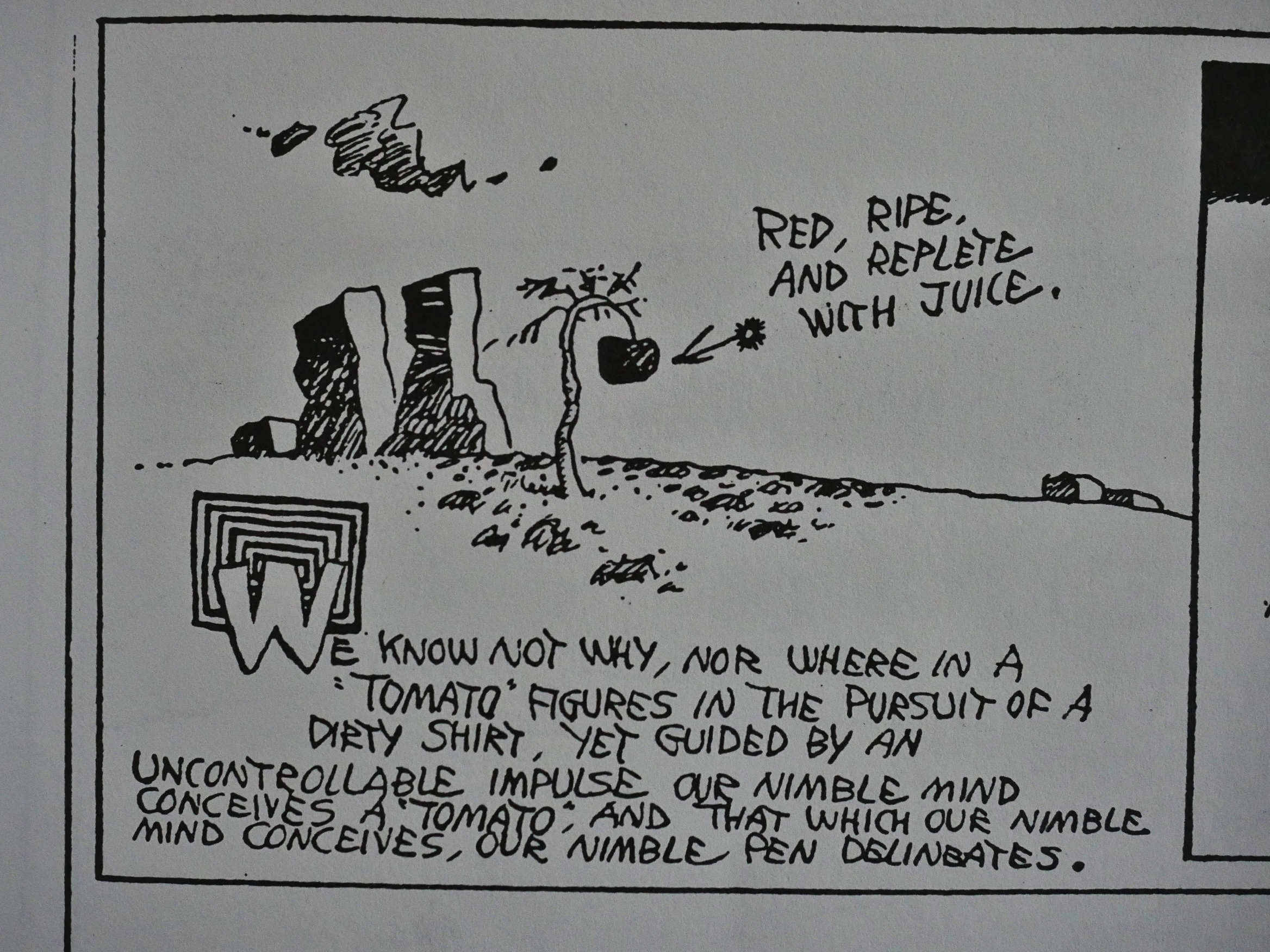

At the that of the series, Herriman didn’t really do the overtly shifting backgrounds much. It’s only in 1917 he really starts in with pages like this, where the object at the horizon changes constantly, but once he started, he used it quite a lot. And never really stopped.

In the second volume we get a debaffler feature, which is nice, because some of the references Herriman comes up with are a bit obscure (beyond the constant dialect word play).

Like “jam closet”, which is a synonym for “blind pig”, which means “a place where you drink alcohol”.

Heh heh. I mean, Herriman does this constantly with names, but I was taken with the Don Kyoti/Sancho Pansy pairing.

Perhaps the most evil scheme Ignatz cooks up in these early strips is his plot to defraud a widow of her cuckoo clock. He’s sold it to her on a down payment plan, but there’s a clause in the contract that states that if it’s broken, he can repossess it. So the day before the final payment is due, he’s stolen the cuckoo out of it, and is on his way to take it.

I guess Herriman also thought this was a bit too far, too real: Ignatz as a scoundrel is fun, but Ignatz as a profiteer would make him unlovable to Krazy, too. (Who foils his evil plans, as usual.)

Perhaps the constant references to “the proletariat” didn’t endear him to the editors of Hearst’s newspapers… which were mostly conservative papers, I think?

Ignatz doesn’t like it when Krazy Kat shows too much attention to women.

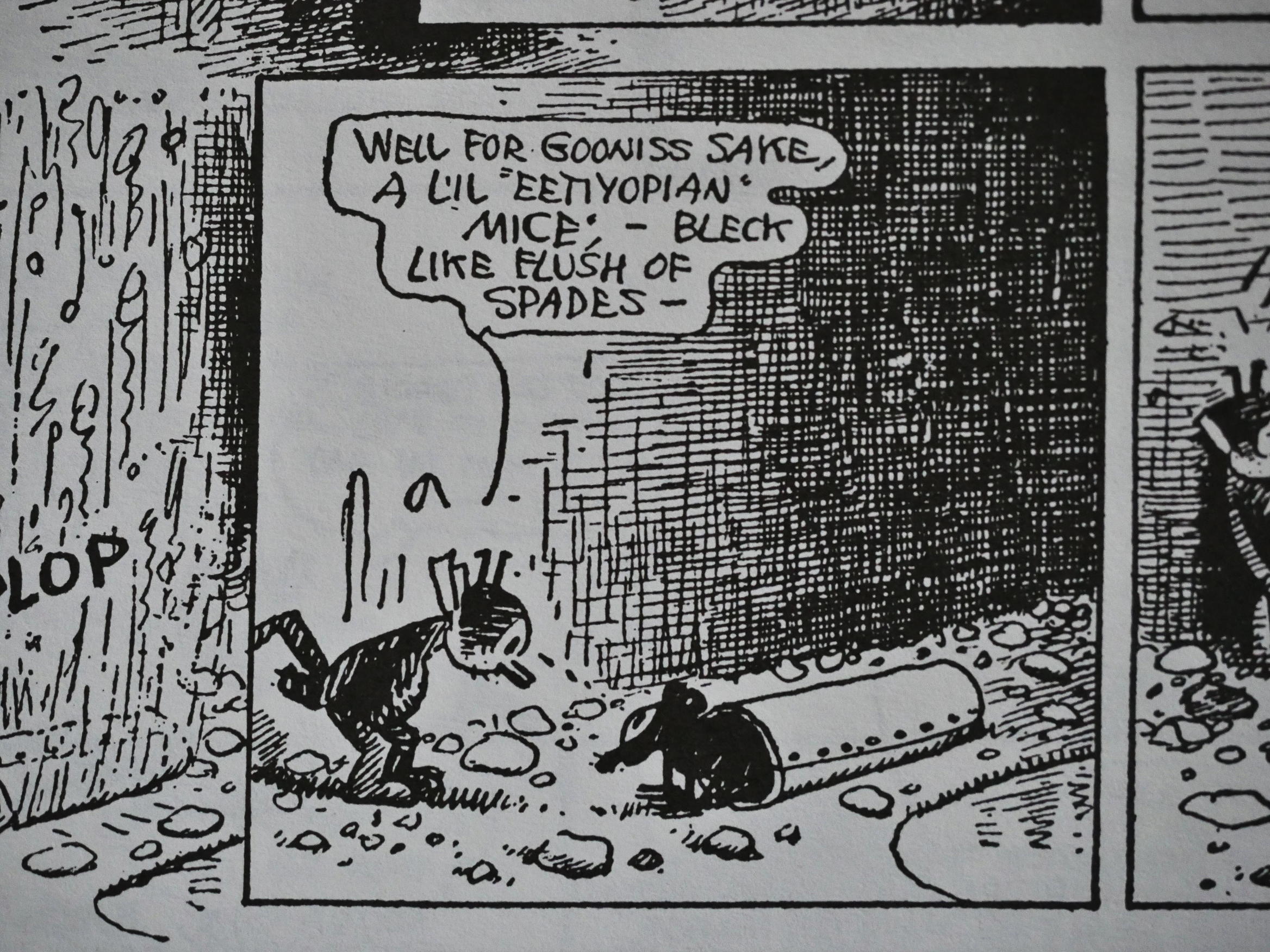

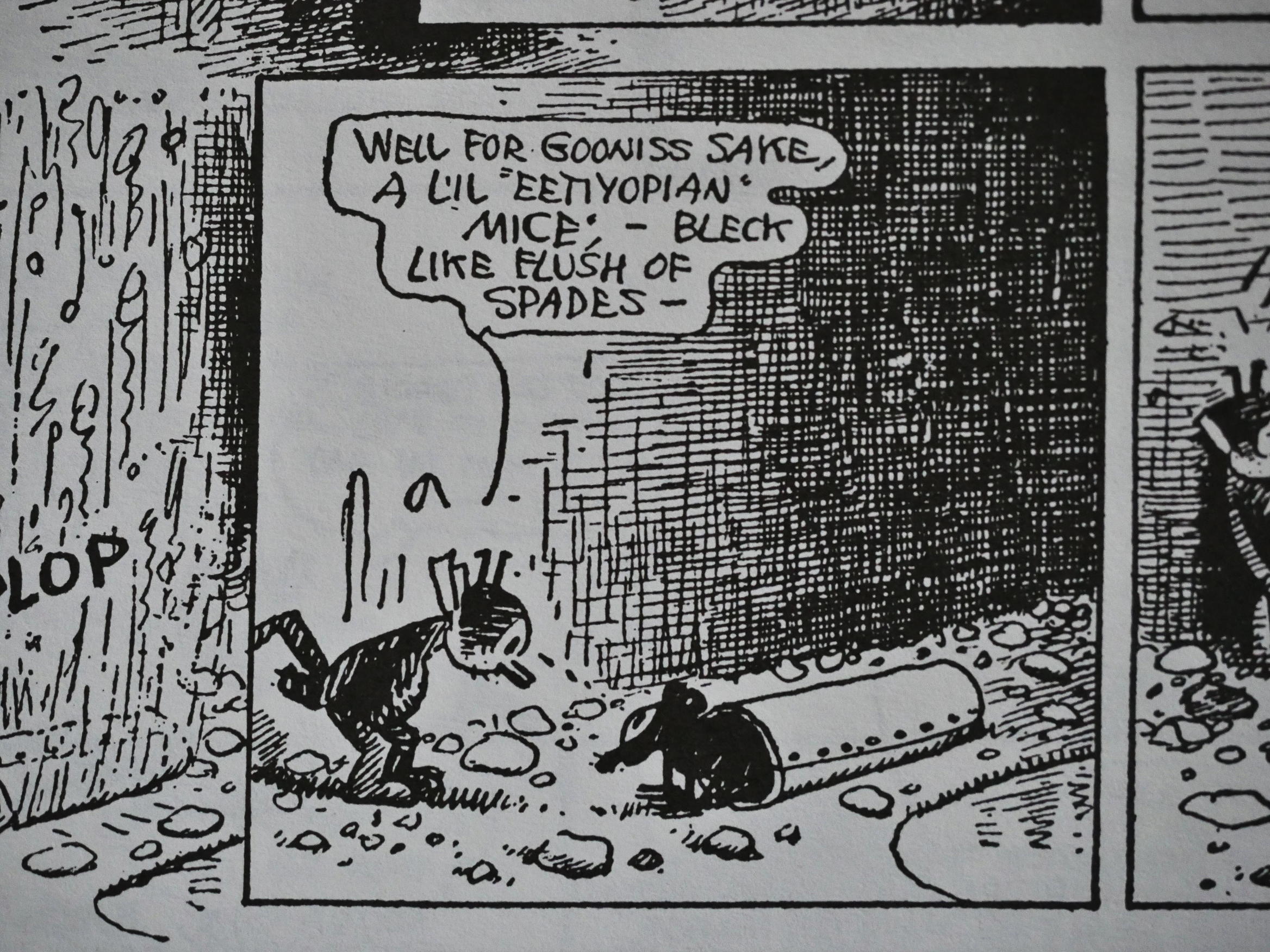

In 1918, we have this page that I think is the first time Herriman plays much with race. Krazy’s hair has been bleached and is now a blonde, so Ignatz suddenly becomes very, very attracted.

One thing I had forgotten is how relatively little Herriman plays with the strip format himself. For a kooky strip like this, he relatively seldom goes meta and draws attention to the mechanics of the strip. Here he’s playing with a line that both a horizon line and something that Krazy can hide underneath and pop out of to surprise Ignatz.

I’m sure that word play meant nothing at the time. Nothing!

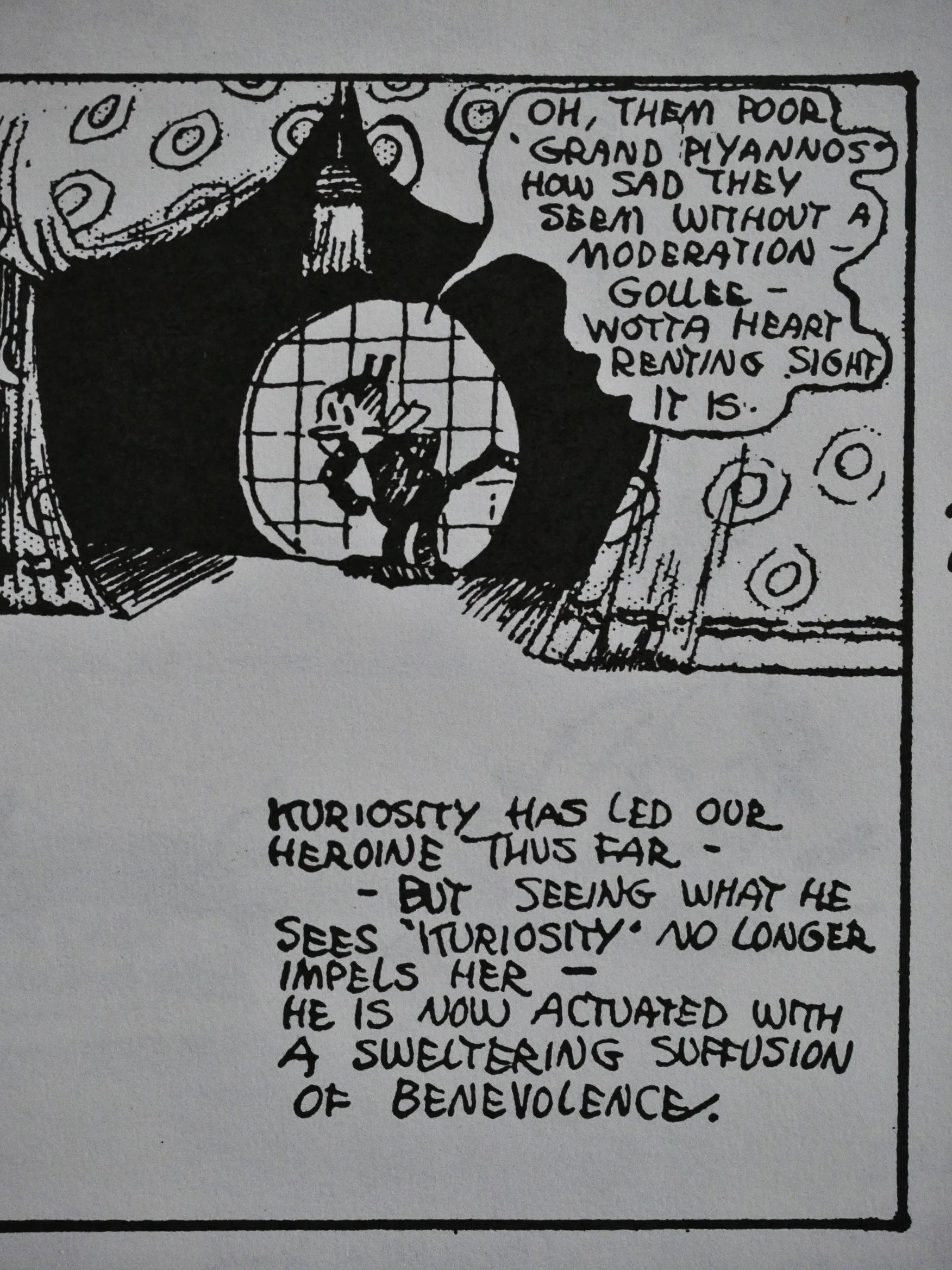

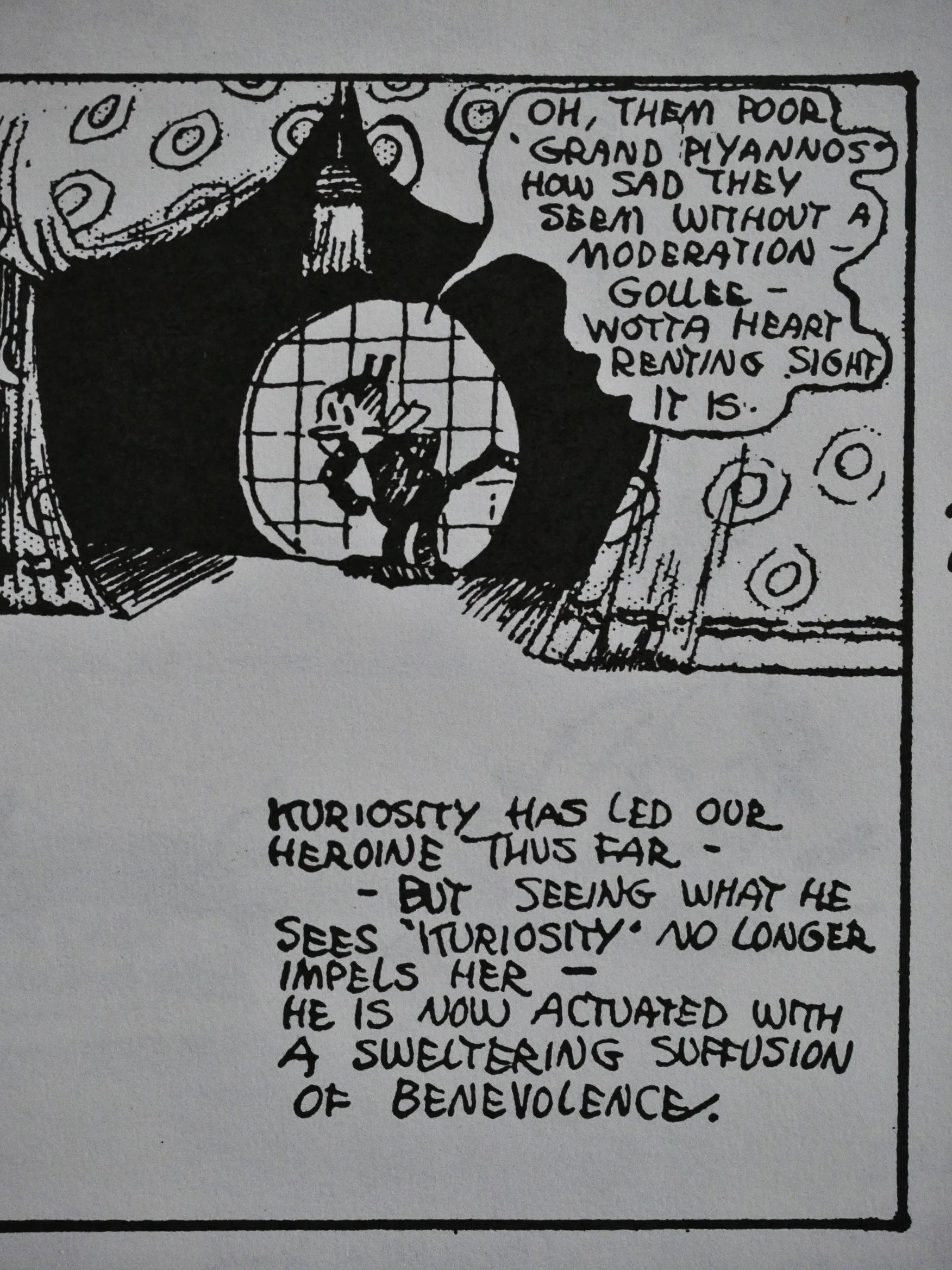

I love the way Herriman ends some of his strips with these diffident, airy comments.

Nearly beer. Was low-alcohol beer also illegal during the prohibition? I’m sure google could tell me, but I’m too lazy to find out.

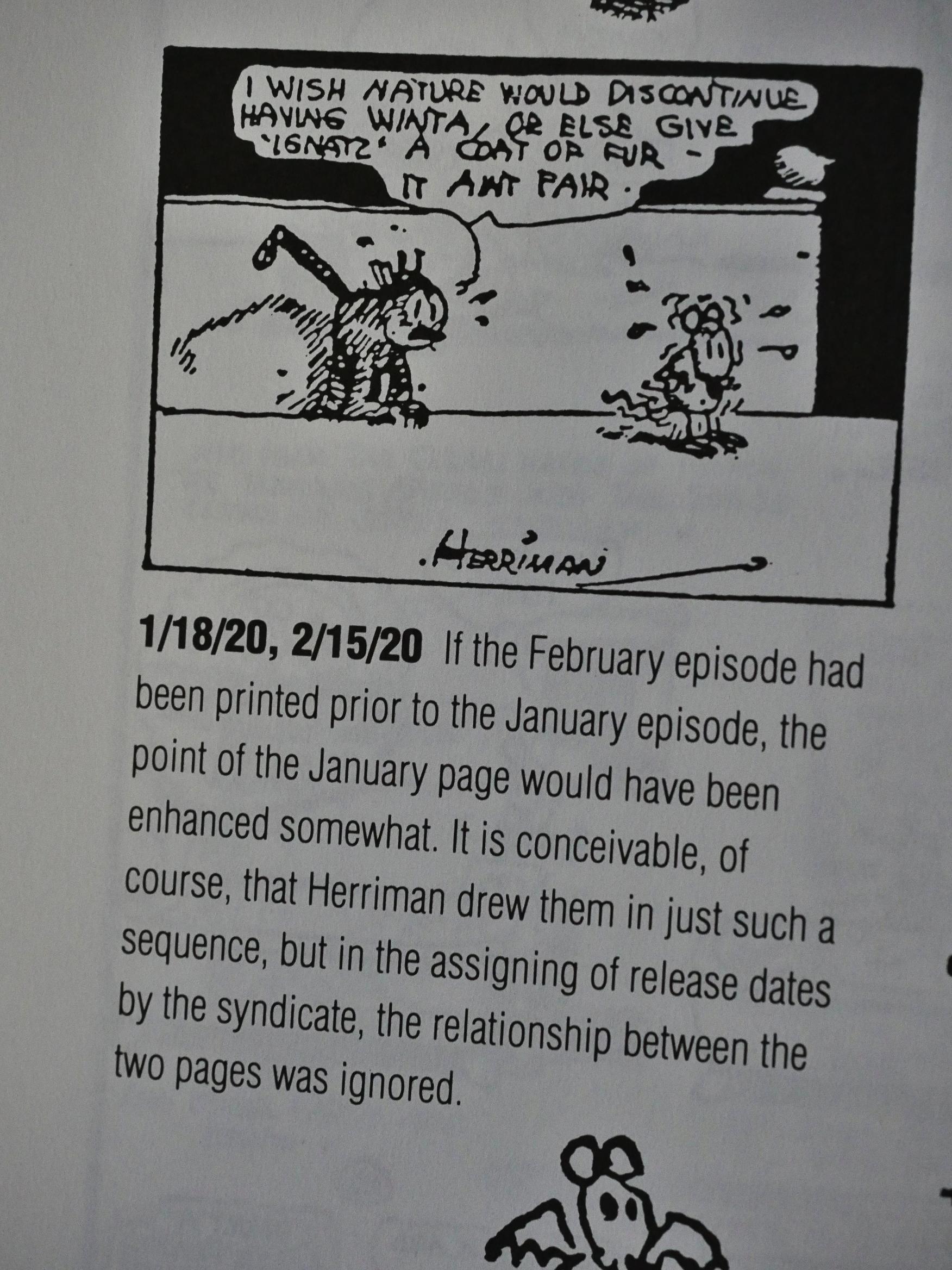

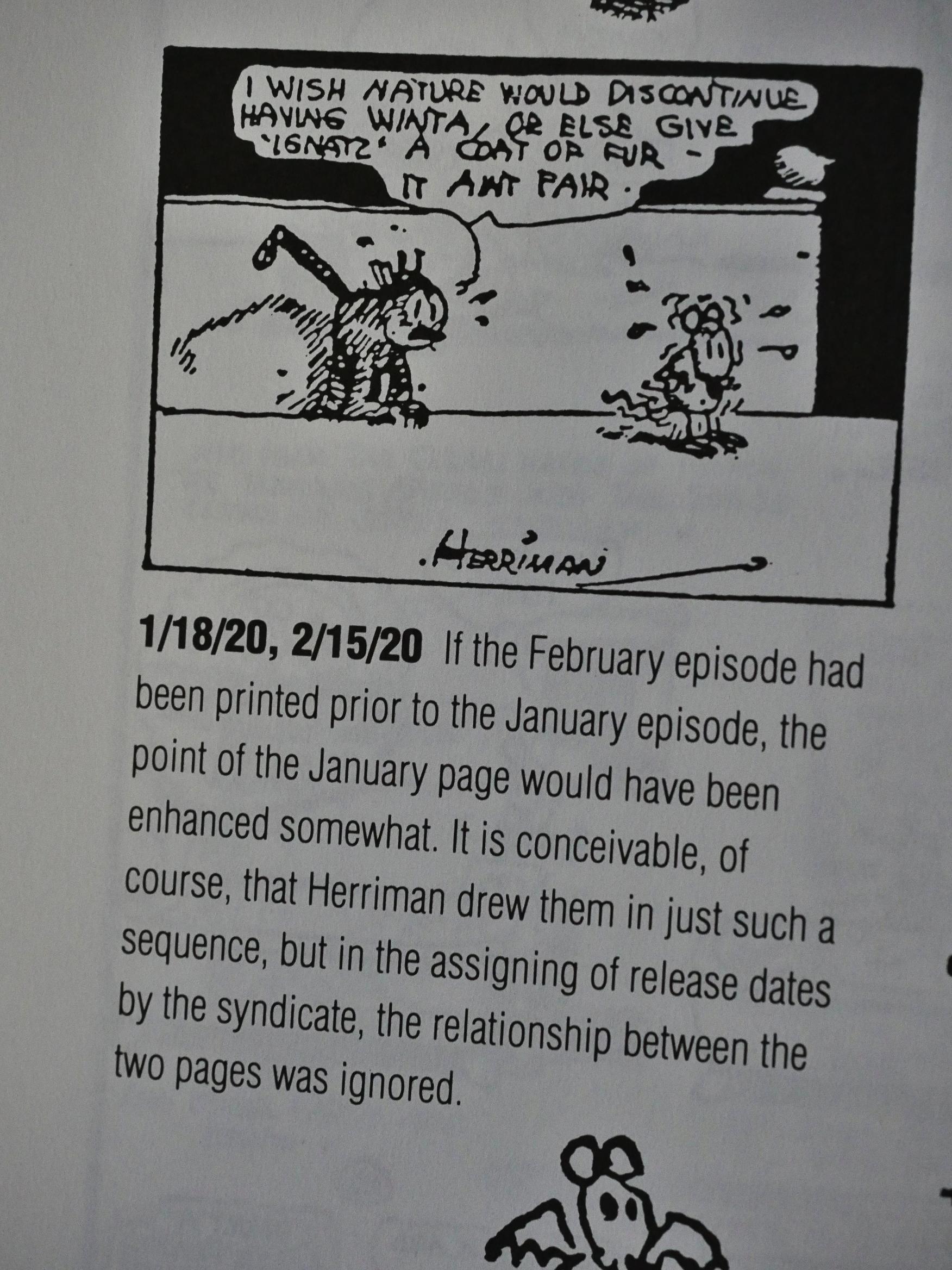

In 1920, we get the first reprinted strip. The story of how mice lost their fur originally appeared in 1919, I think, so I turned to the debaffler page:

Which doesn’t mention that at all, only that it would have made more sense for that page to appear before the January page where the story continued. So Blackbeard had forgotten the earlier appearance of the February page. Tsk, tsk. I still wonder whether it was really reprinted, or whether this was a production snafu when they collected pages for this collection.

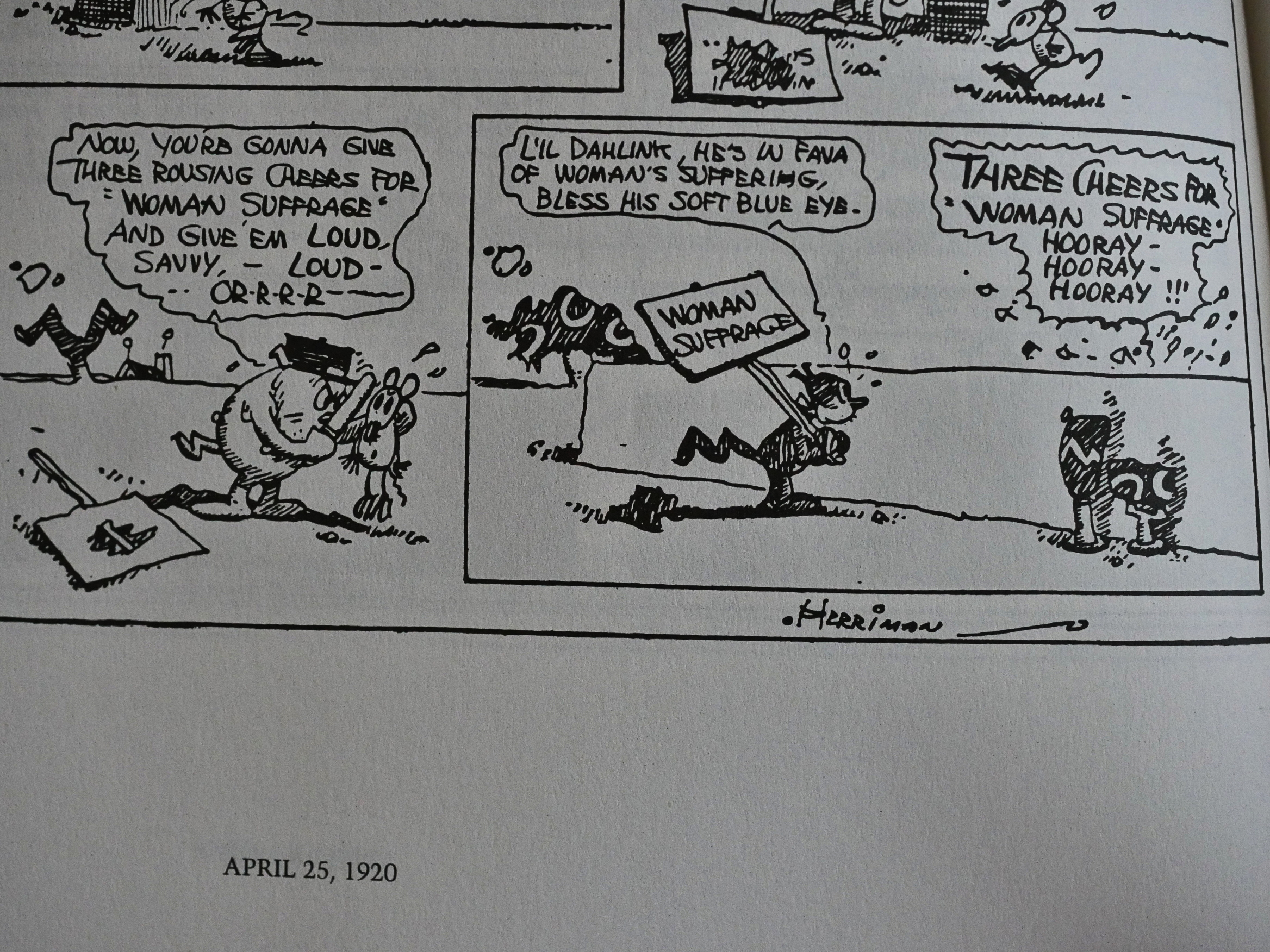

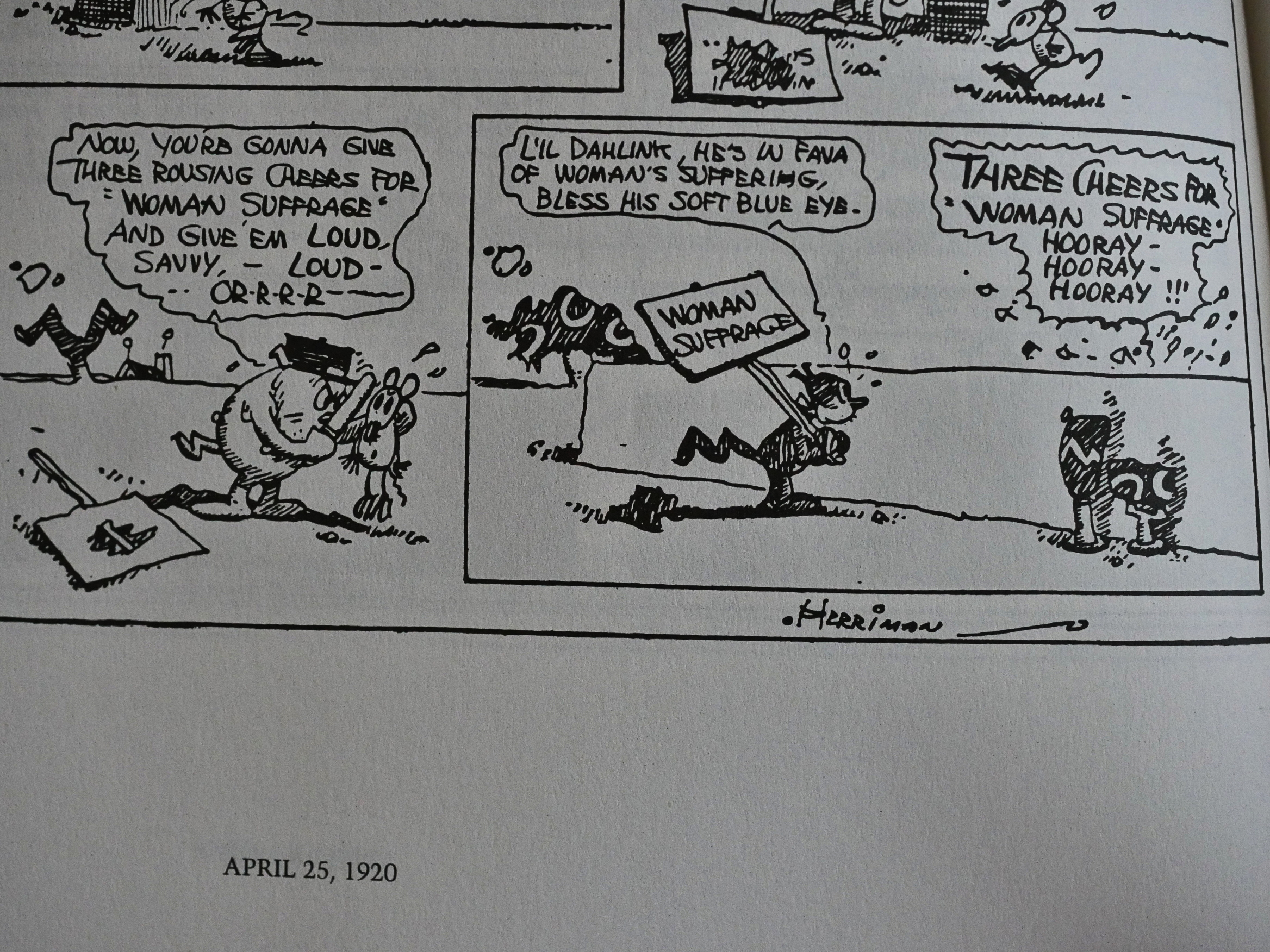

Ignatz is, of course, on the wrong side of every cause.

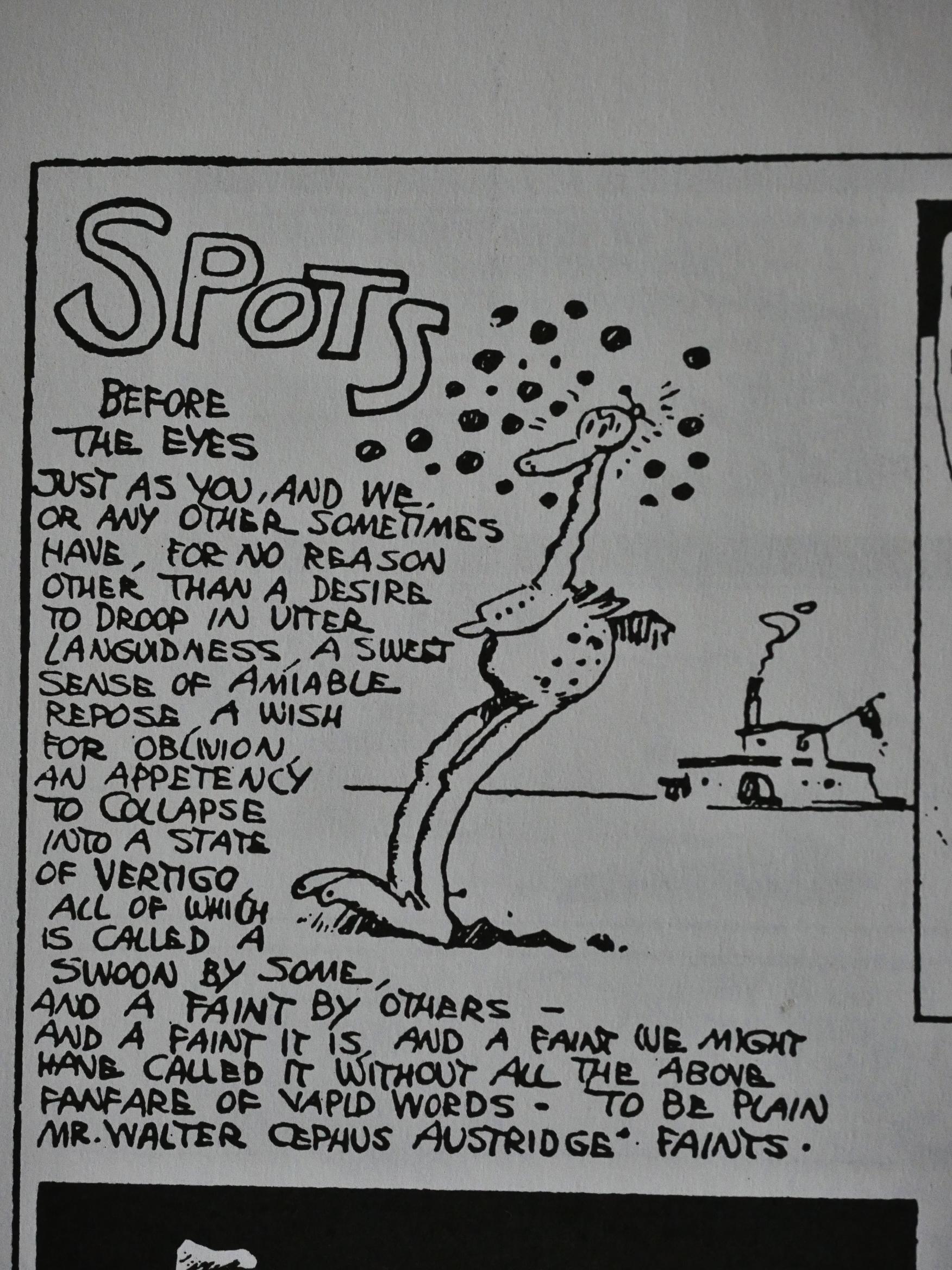

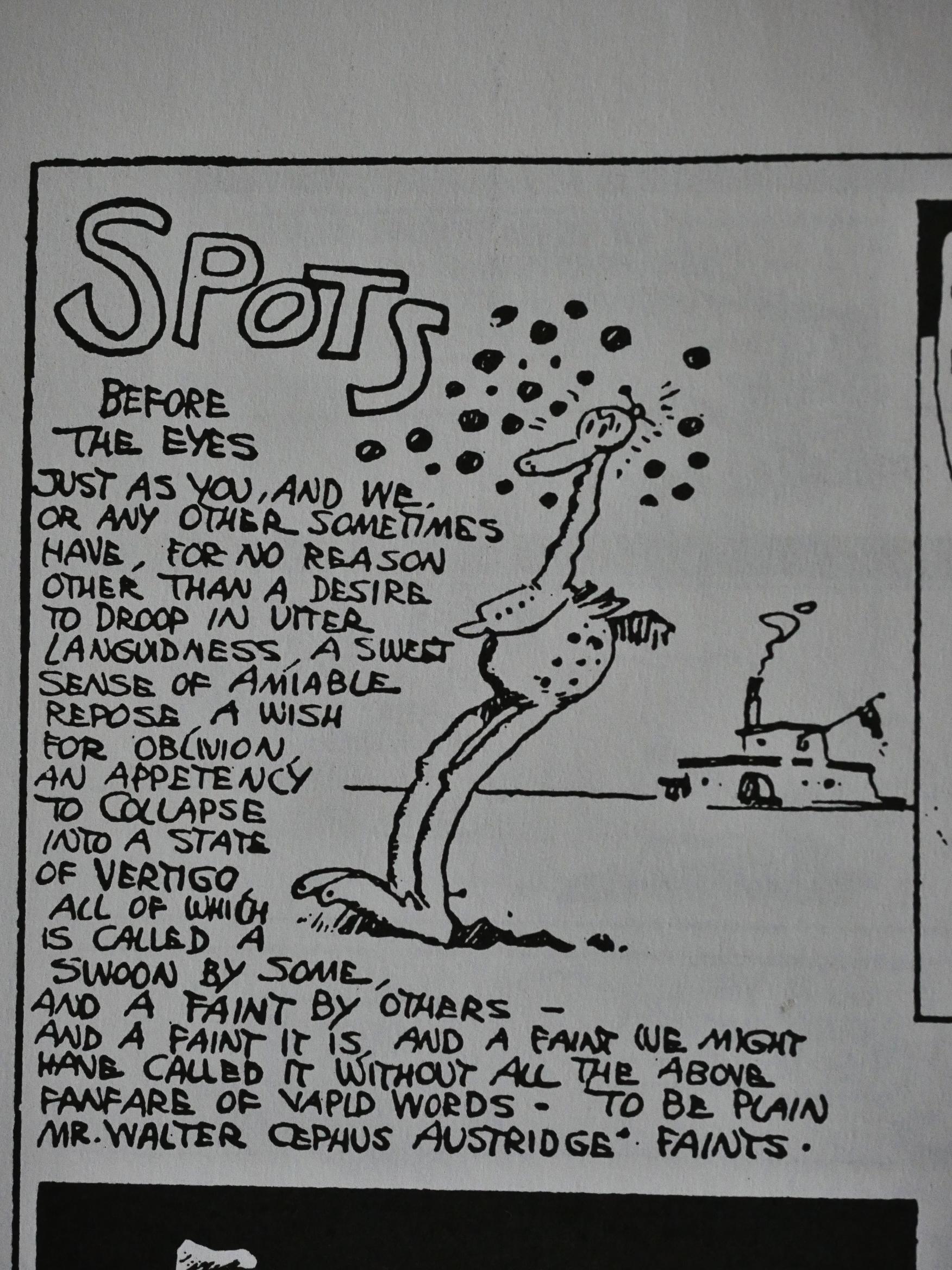

I’m really impressed with Herriman’s meandering way of saying not very much at all. It seem so unforced and natural that I’m just bemused and amused. I can totally see how other people might not have the patience for this nonsense, though.

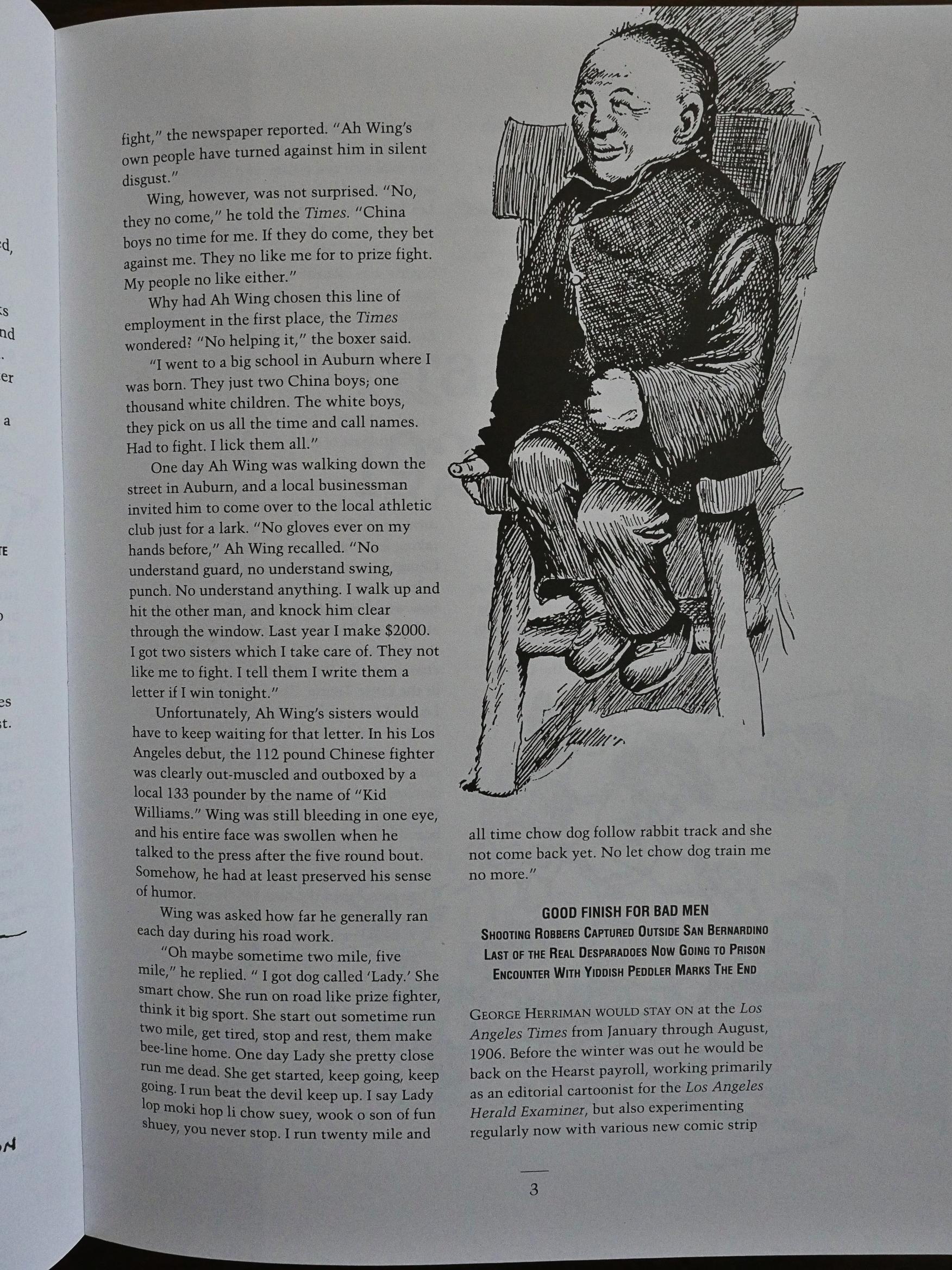

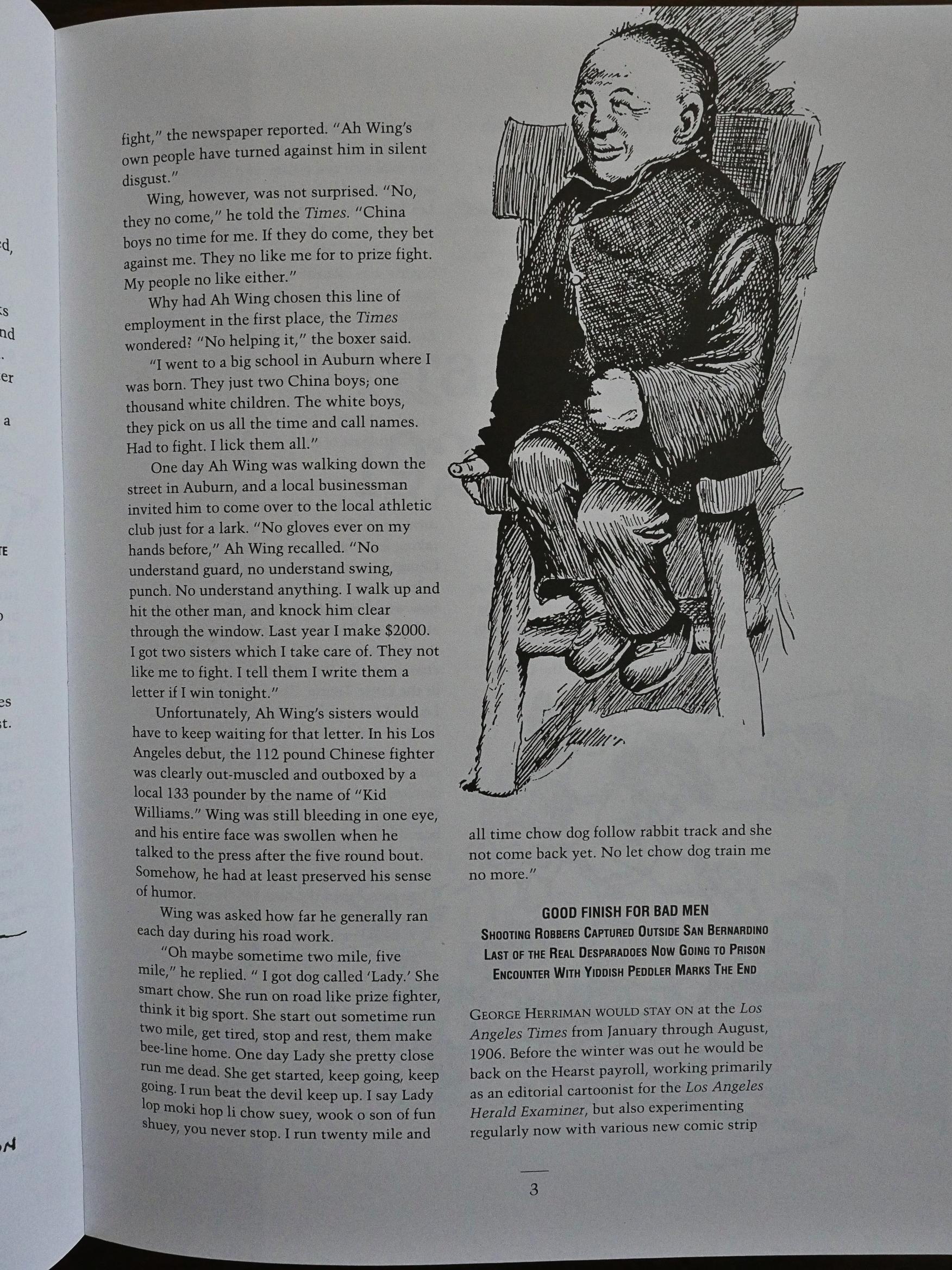

Blackbeard’s introductions get more interesting as the series progresses. Perhaps the series created an impetus for him (and others) to go out there and do more research? Anyway, in the 1921 volume we get examples from Herriman’s career as a journalist… for “lighter” items, like here when he’s interviewing a Chinese boxer that’s visiting the US.

Krazy Kat is usually very gentle, but there’s several strips where Krazy’s a boxer… and it’s a total massacre.

After the first few years, the reproduction get a lot better. I’m guessing they found better-preserved newspapers? It’s still variable (especially the 1924 volume has some annoying glitches), but some of these look absolutely astounding.

I think if we could peek into Herriman’s head when he was (sort of) baiting the tiresome “well, what gender is Krazy?” people, like here, we’d find that the overriding thought going on was “tee hee”.

Or perhaps not. Are we mind readers?

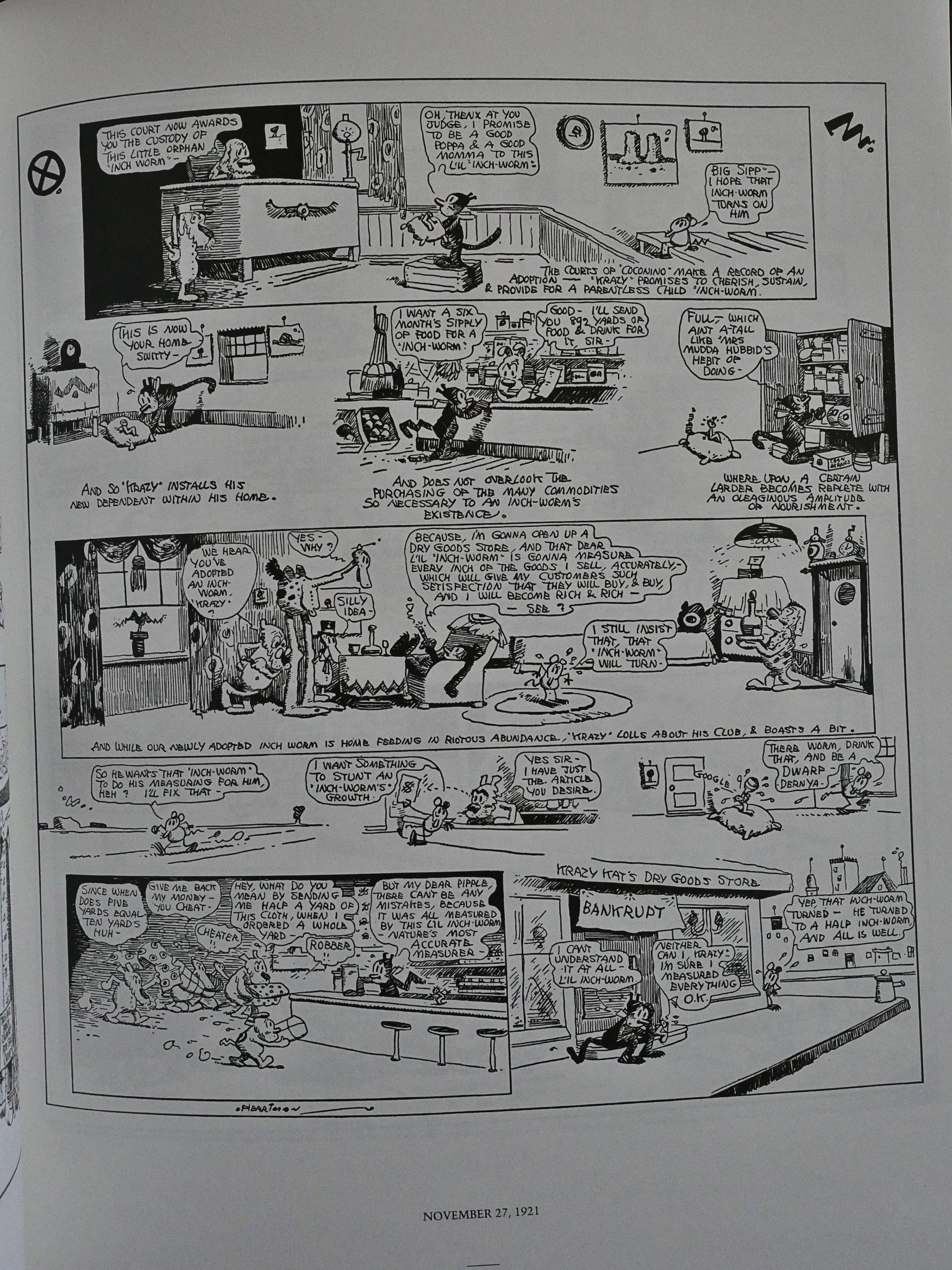

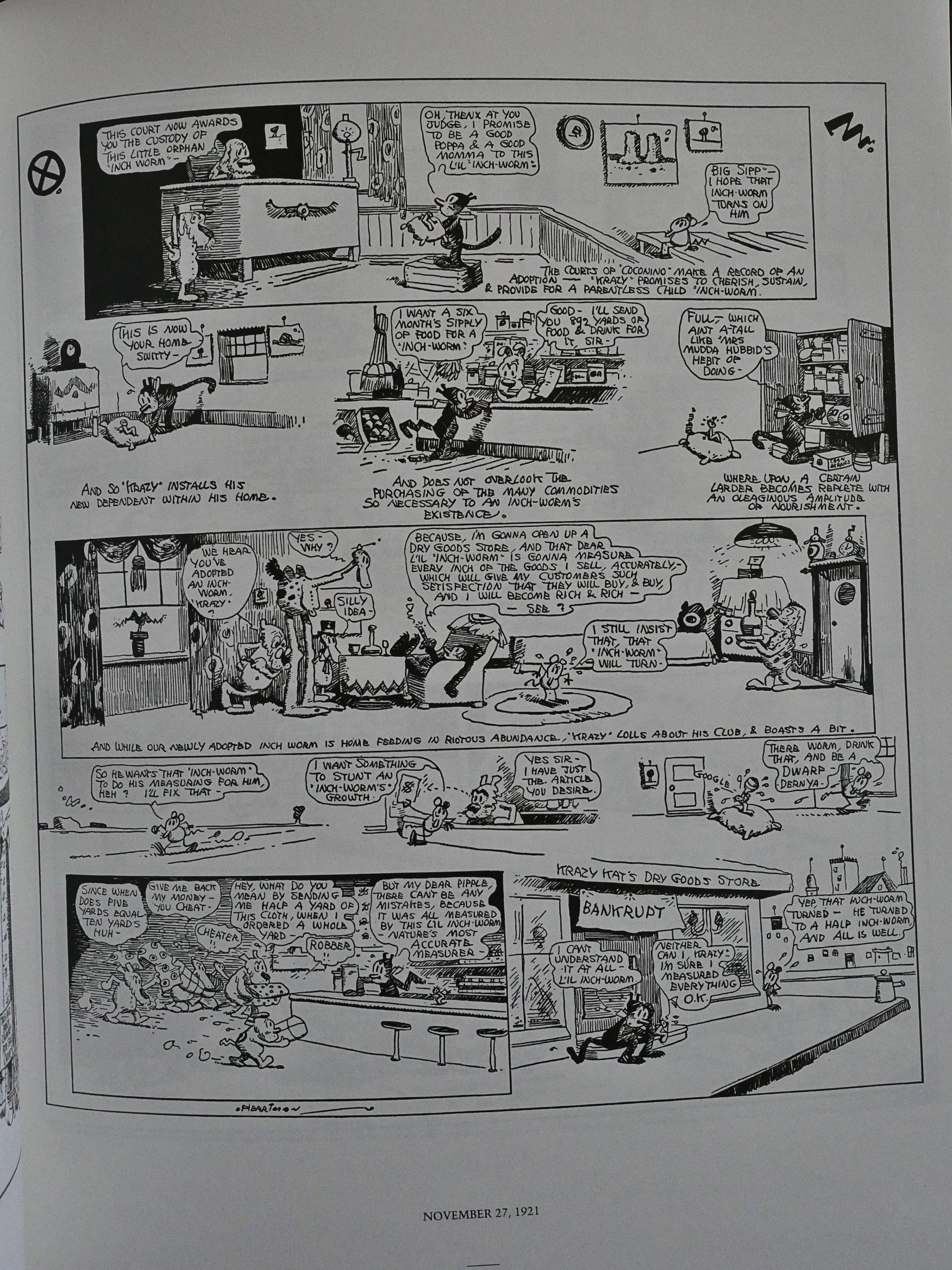

There aren’t many strips like this, which is like a Carl Barks ten-page Donald Duck strip in miniature: Krazy comes up with a brilliant business scheme, it all goes wrong, and the business has to be shut down. I love it. I mean, I like the “normal” stuff, too, but (especially after having read all these in as short as time as this), variation’s nice, too.

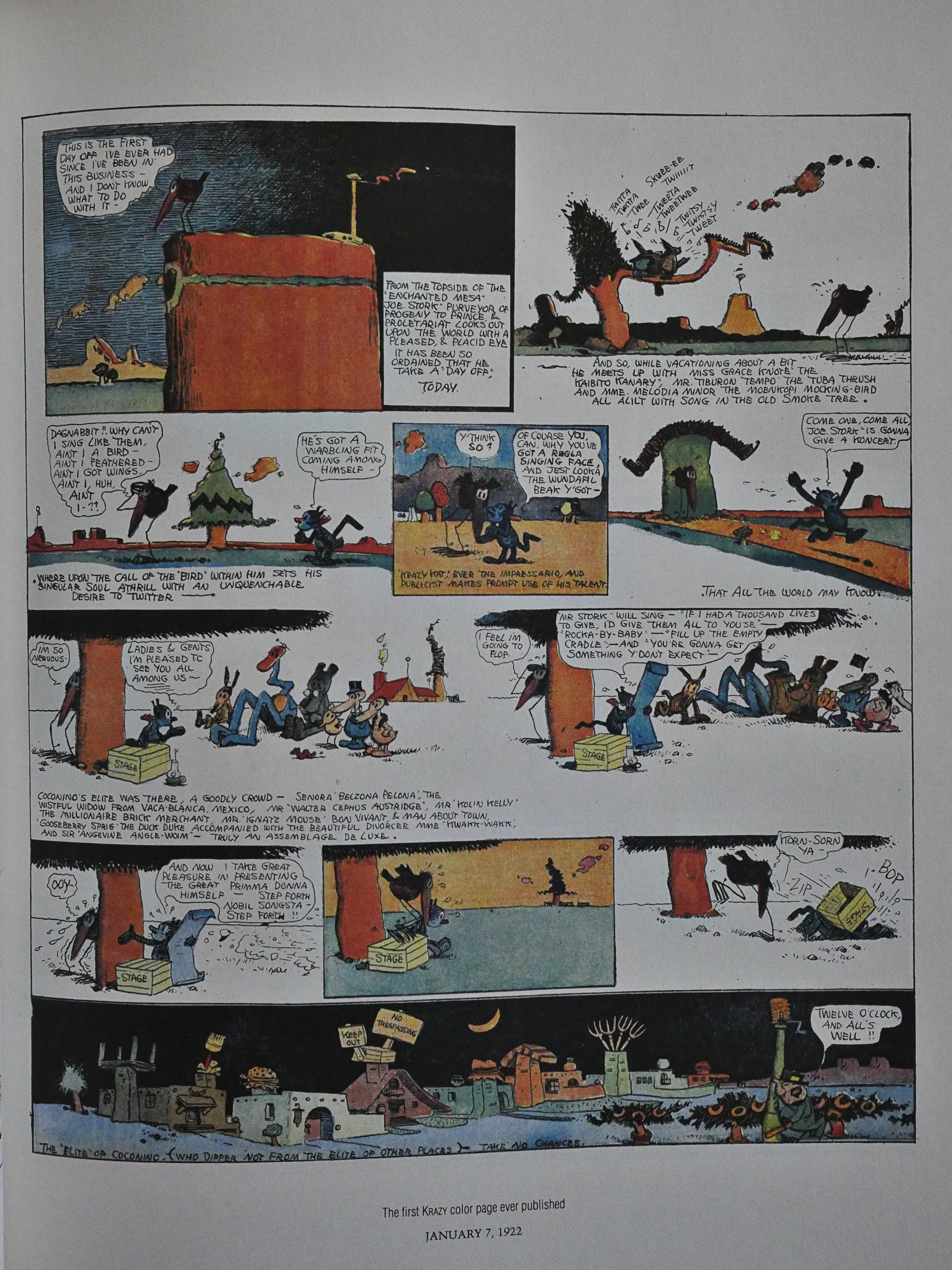

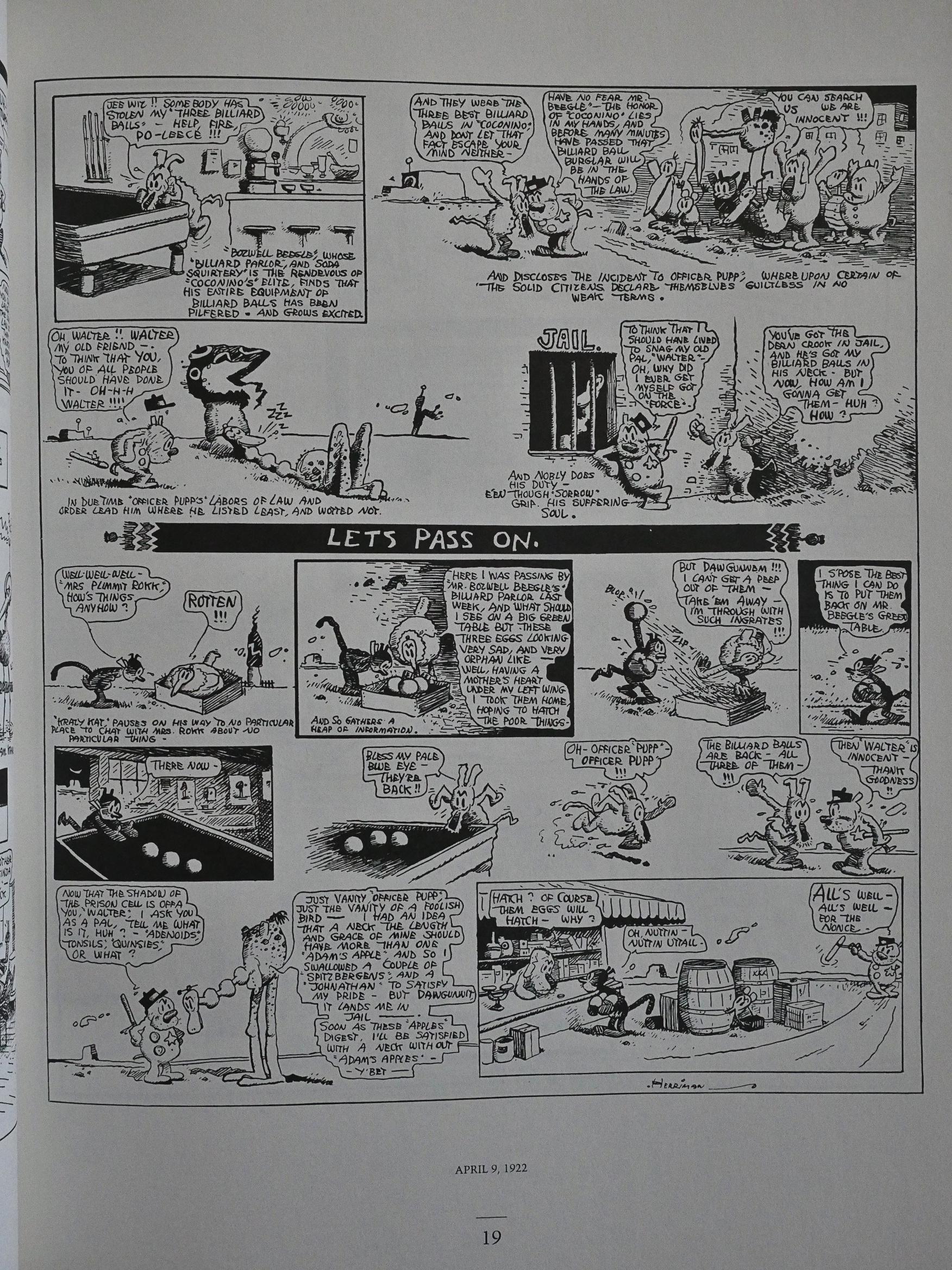

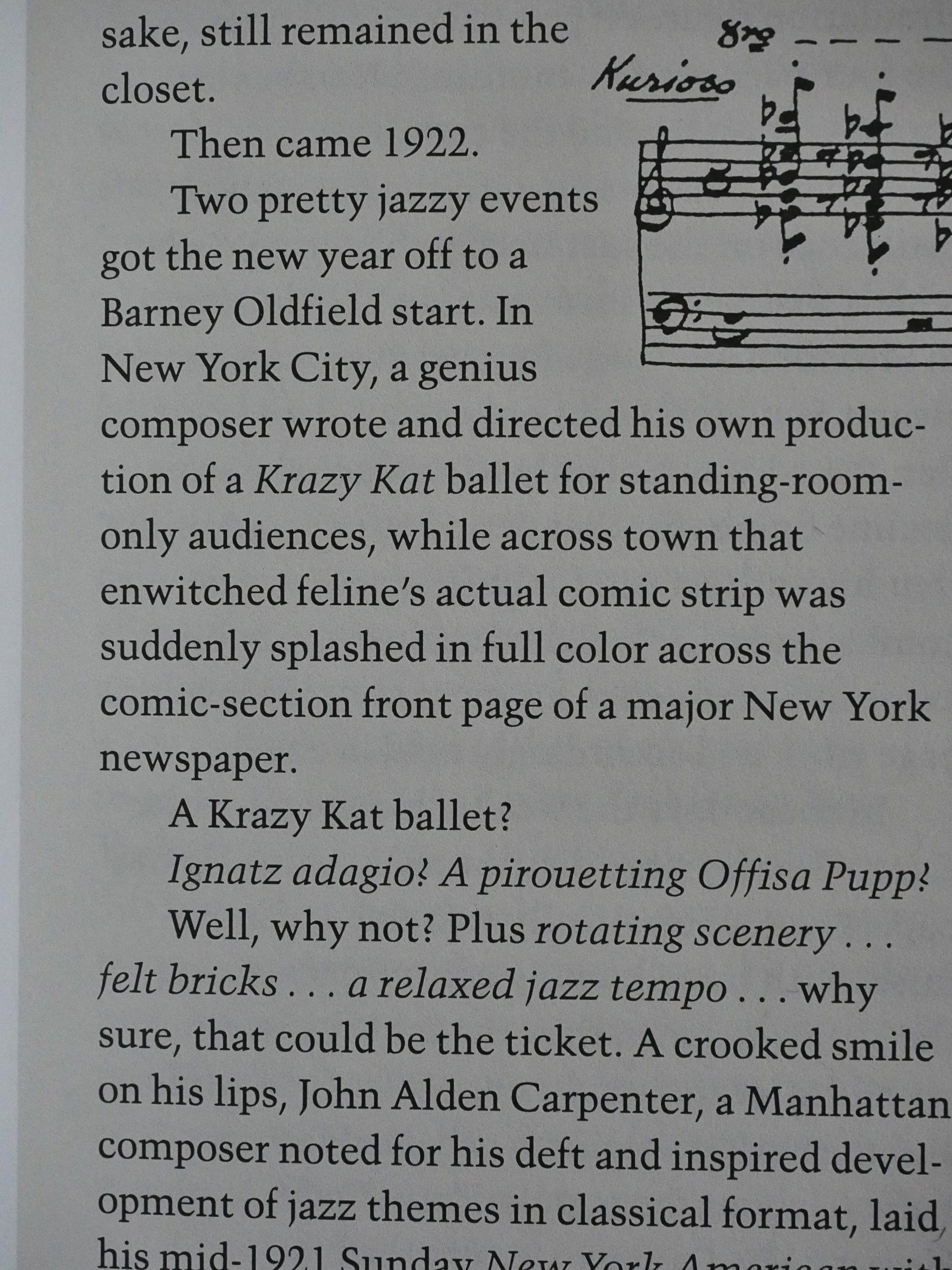

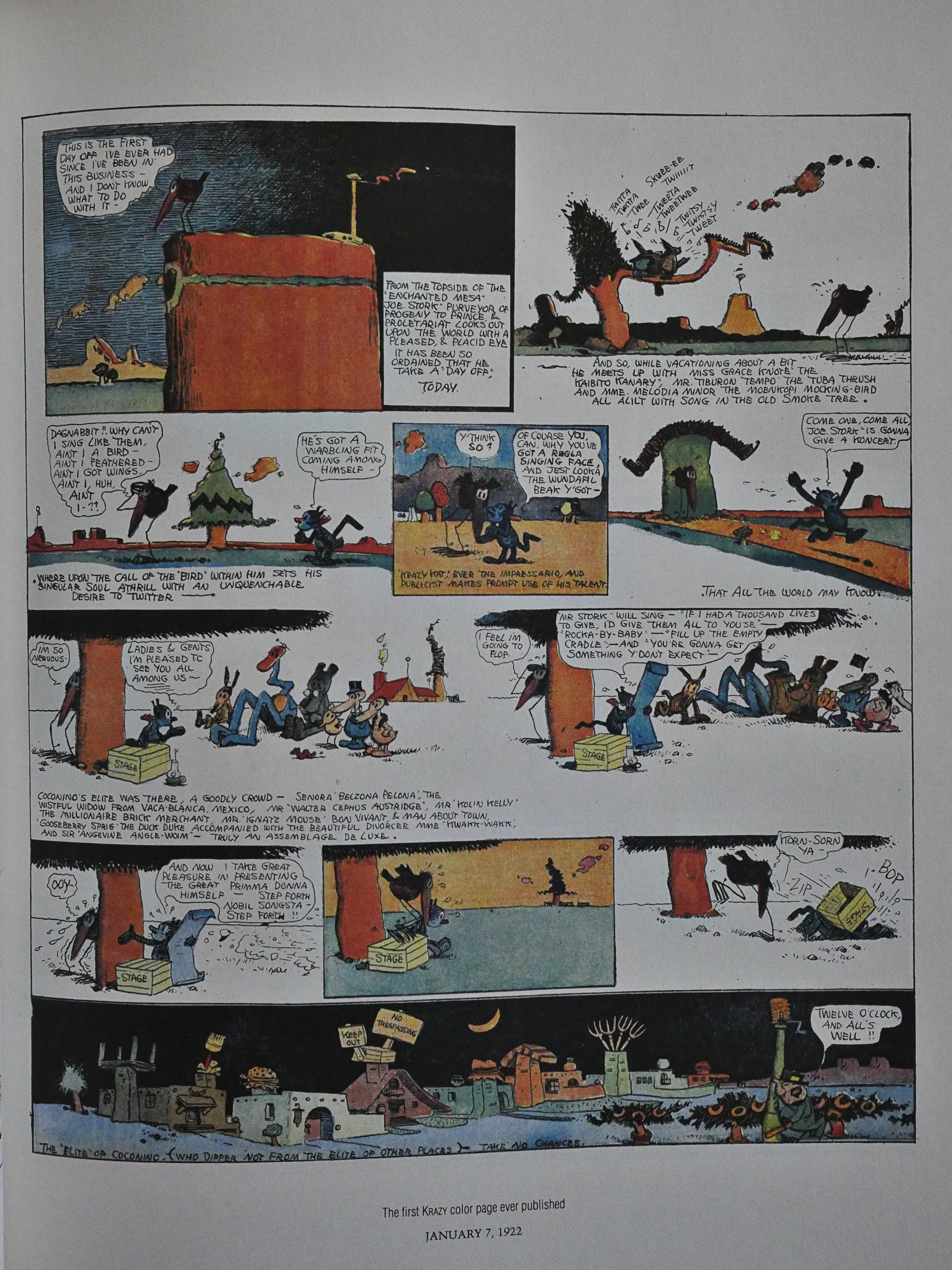

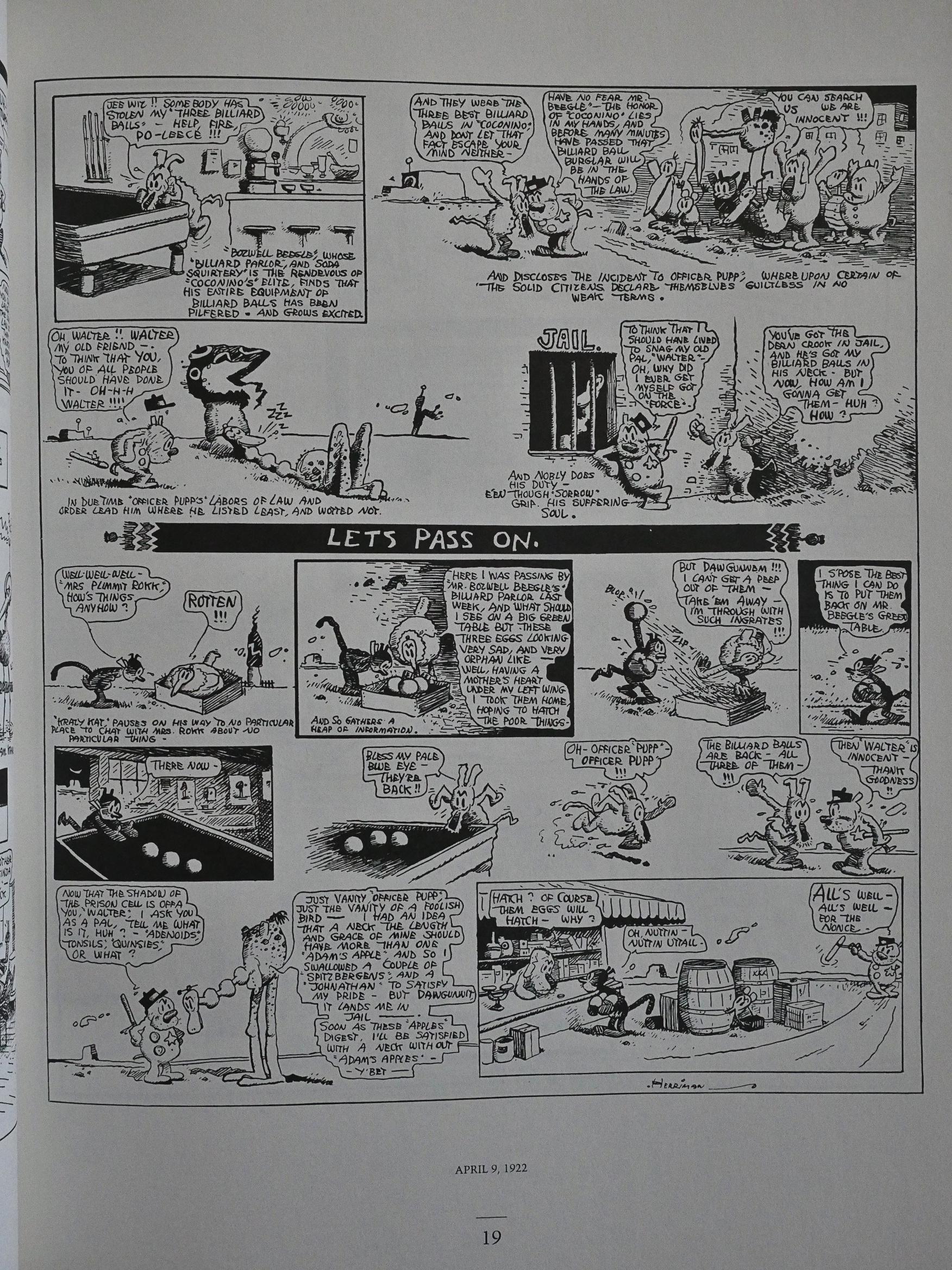

Apparently 1922 was the breakthrough year for Krazy Kat as far as high culture recognition. A ballet was created in New York, and to celebrate, Herriman was given a weekly colour page in the local Hearst paper, all of which gave him a lot of attention. Especially from the cultural elite.

So while this was going on, there was the normal national black and white Sundays (in which Offisa Pup was developing a more explicit crush on Krazy)…

… as well as a colour page in New York. The very first page has Krazy coloured blue, while Krazy shifted to the yellow we’re used to now. A printer’s error or did Herriman change his mind? Blackbeard’s commentary doesn’t, er, comment.

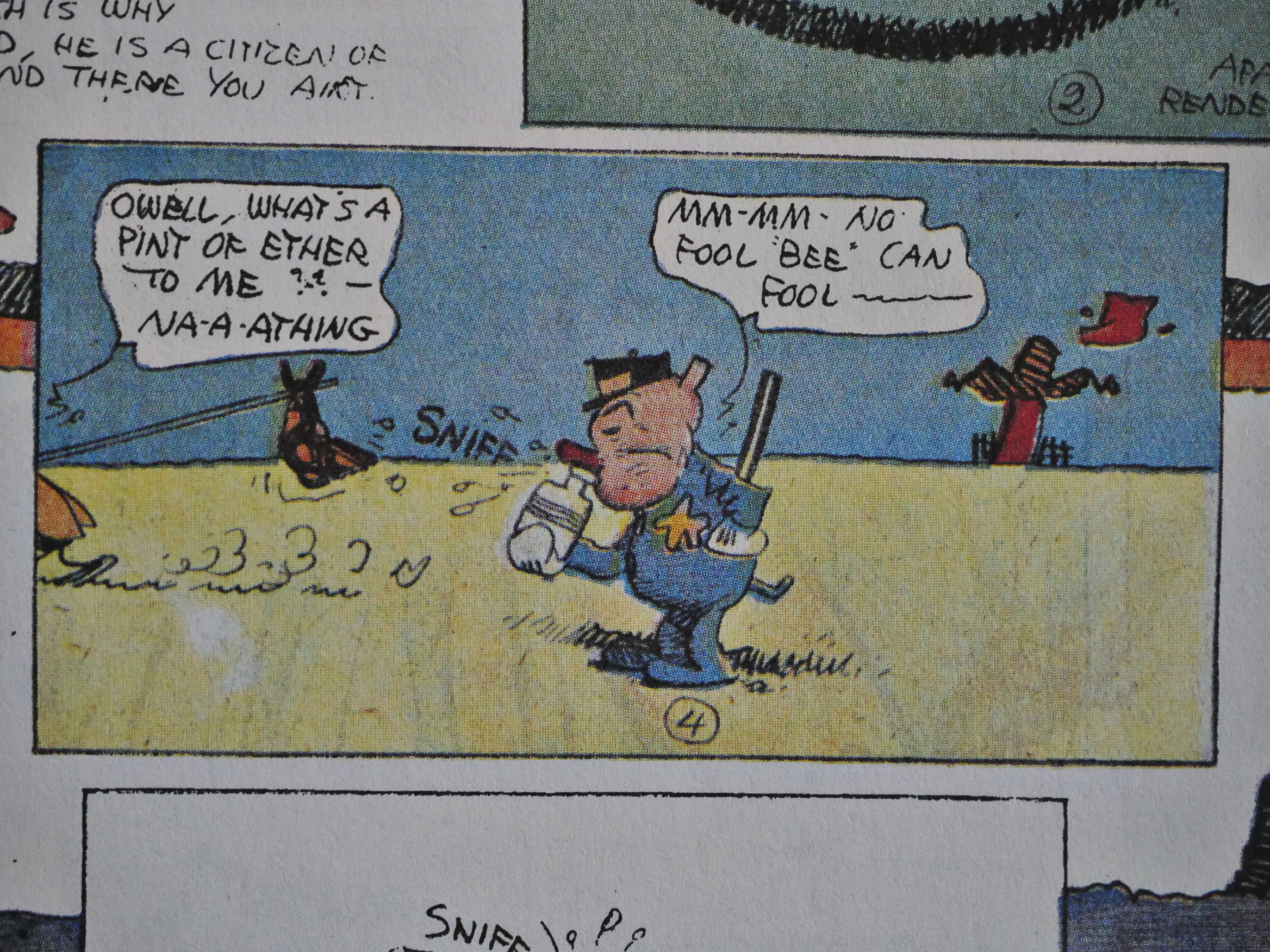

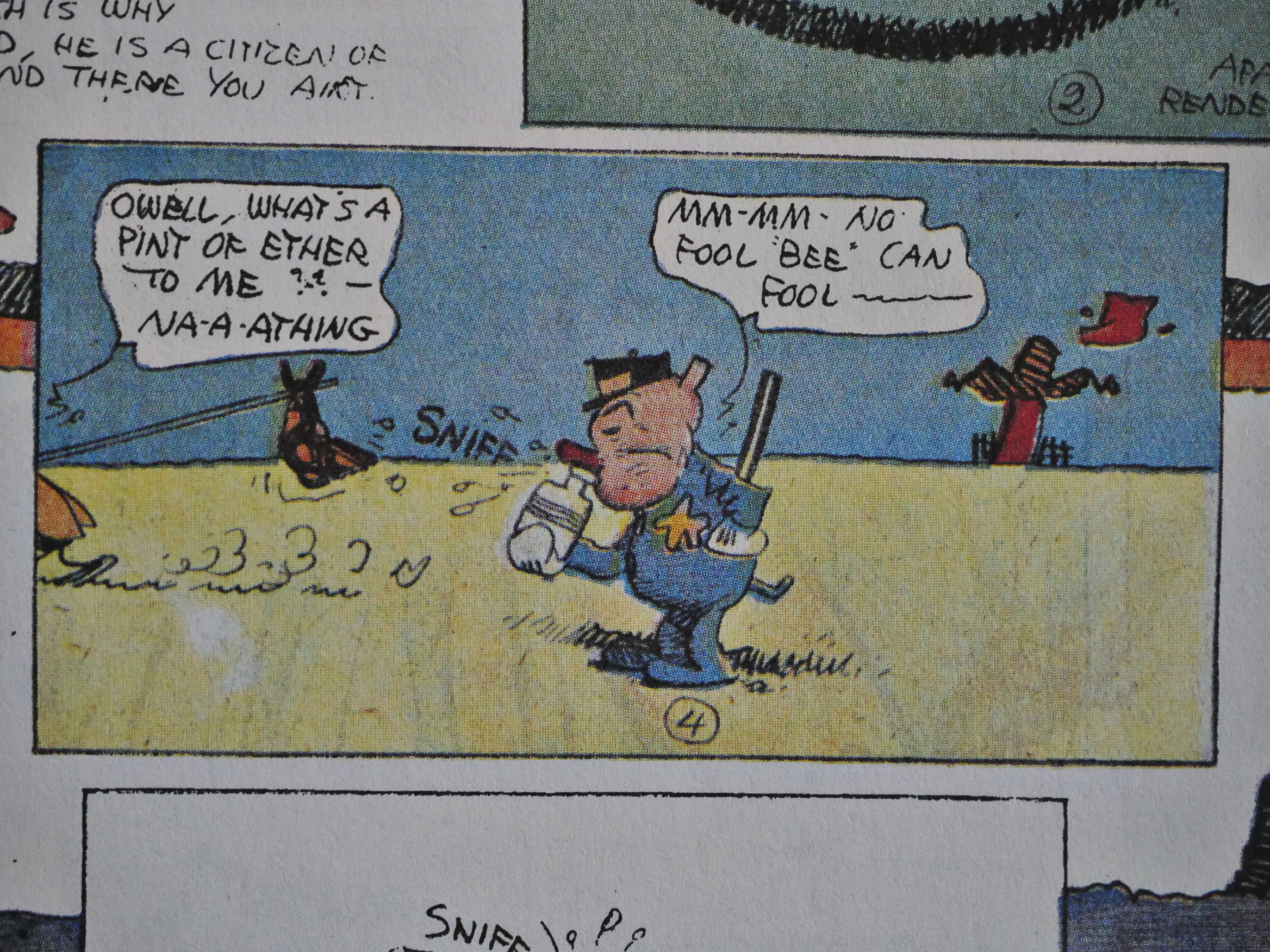

While the colour pages are all brand new, a couple of them recycle gags from older pages, like this one where Offisa Pup (and eventually all of them) sniff a bottle of ether.

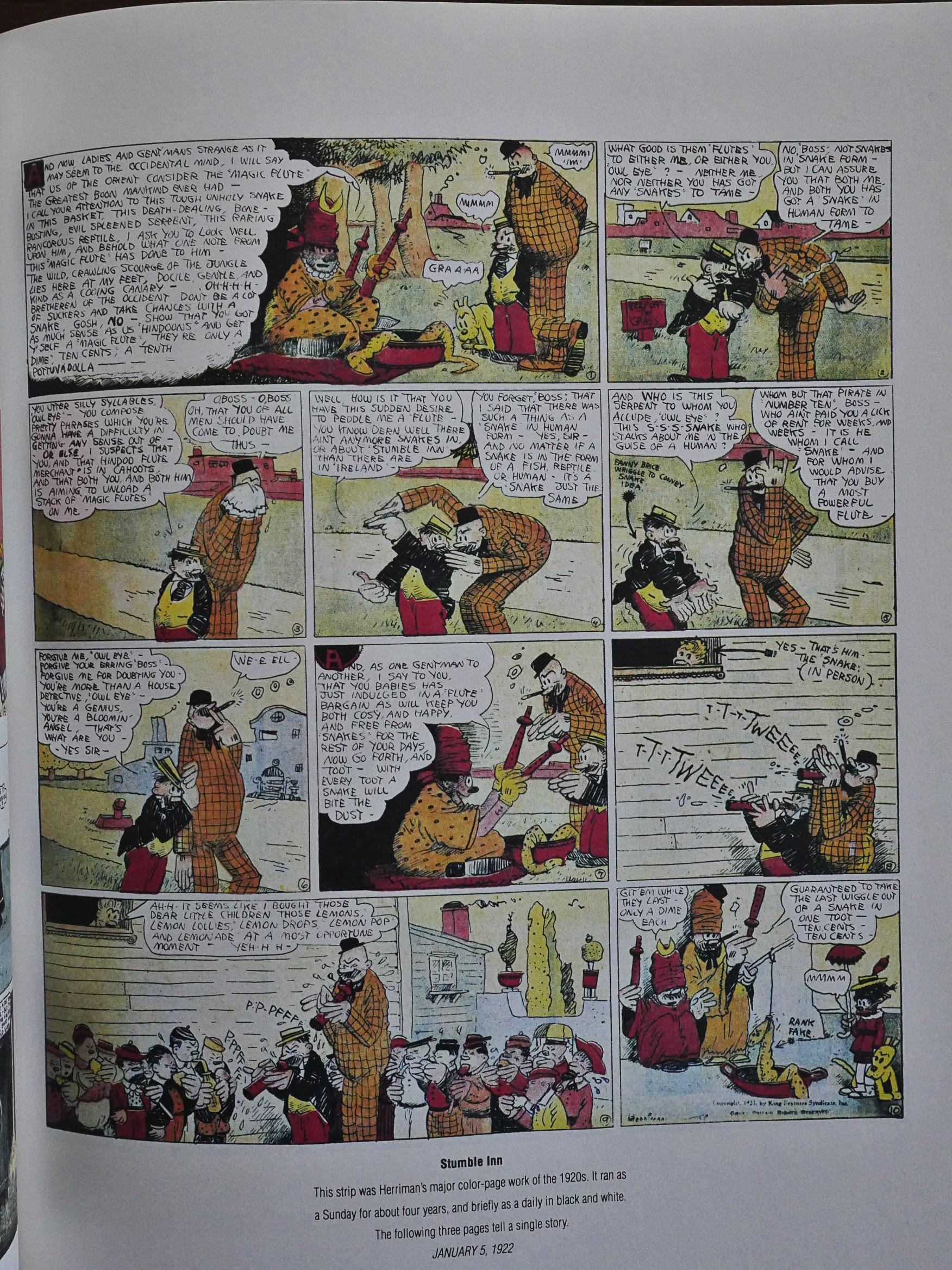

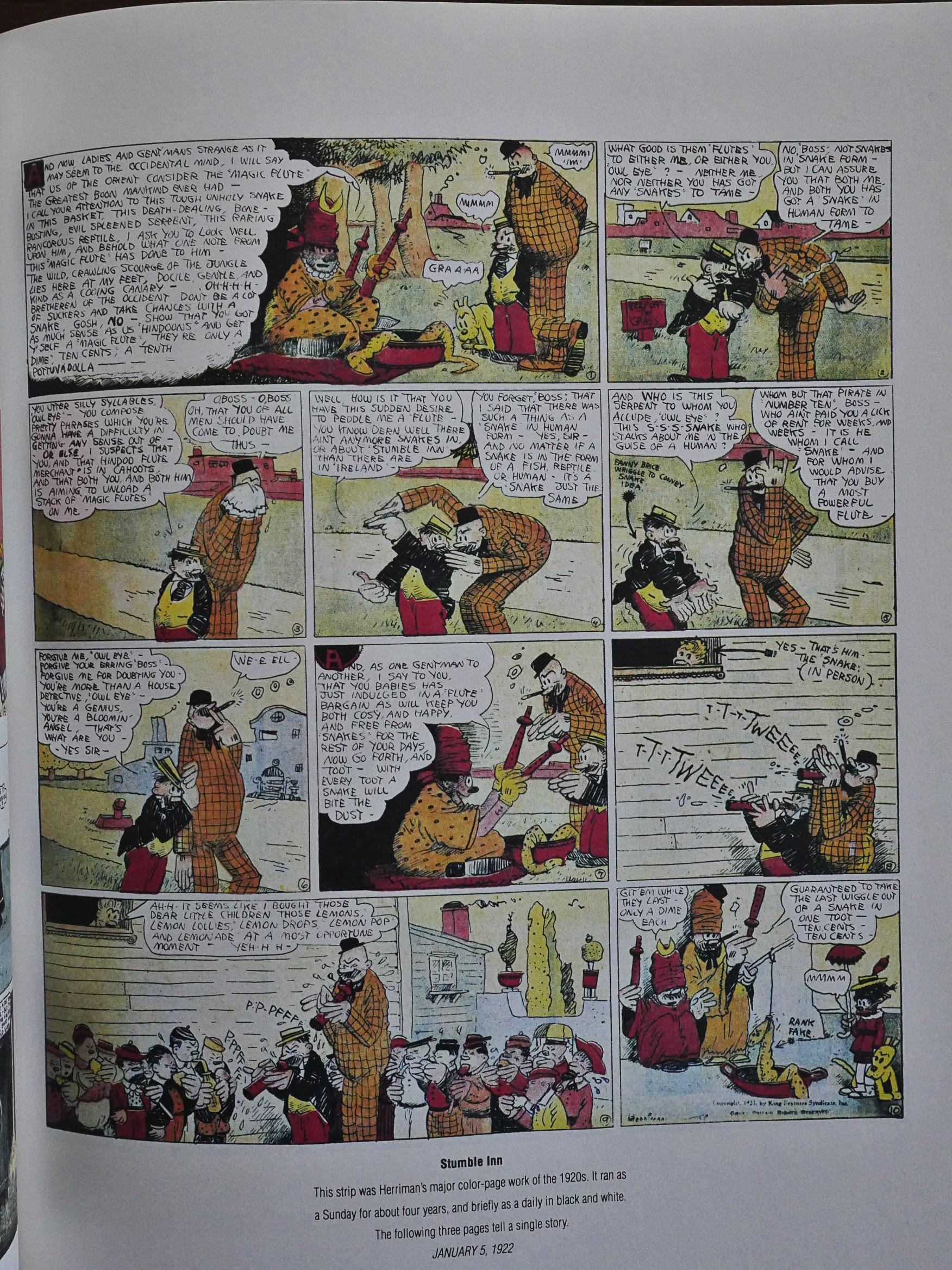

To fill out the rest of the 16 page colour supplement in this volume, we get a sampling from some other strips Herriman had going around this time.

There’s something about this strip… Mrs. Plimmit Rock makes an appearance in the middle of this strip where it’s divulged that she’s the one who stole the billiard balls, and then the strip winds its way to the resolution. But then there’s the very last panel, where Krazy buys eggs, and we have to make the connection back to her predicament. I think it shows how much faith Herriman had in the reader getting involved, and it’s sweeter for not having Krazy’s intentions spelled out: Of course Krazy didn’t forget about her, even if we (as readers) did.

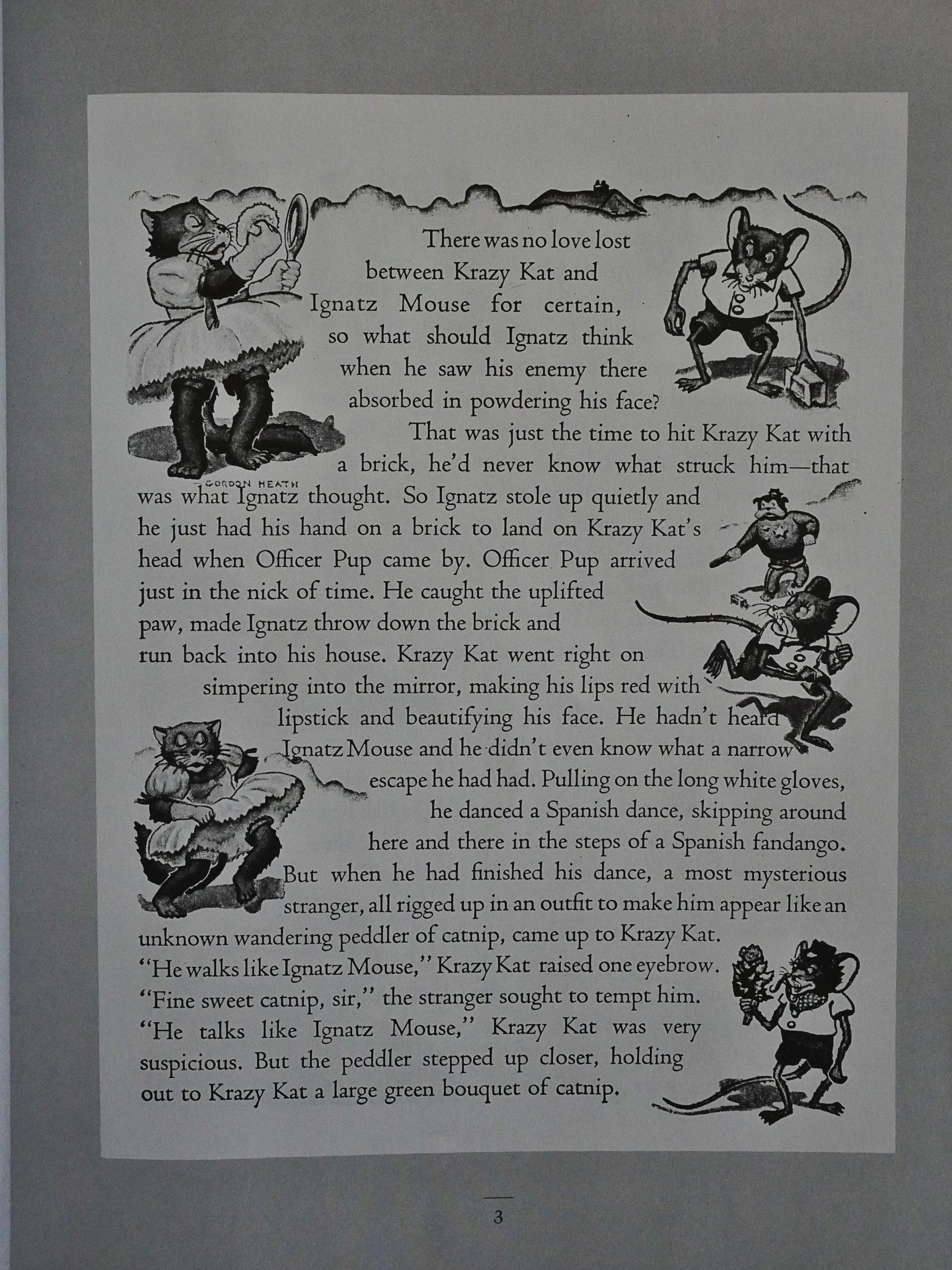

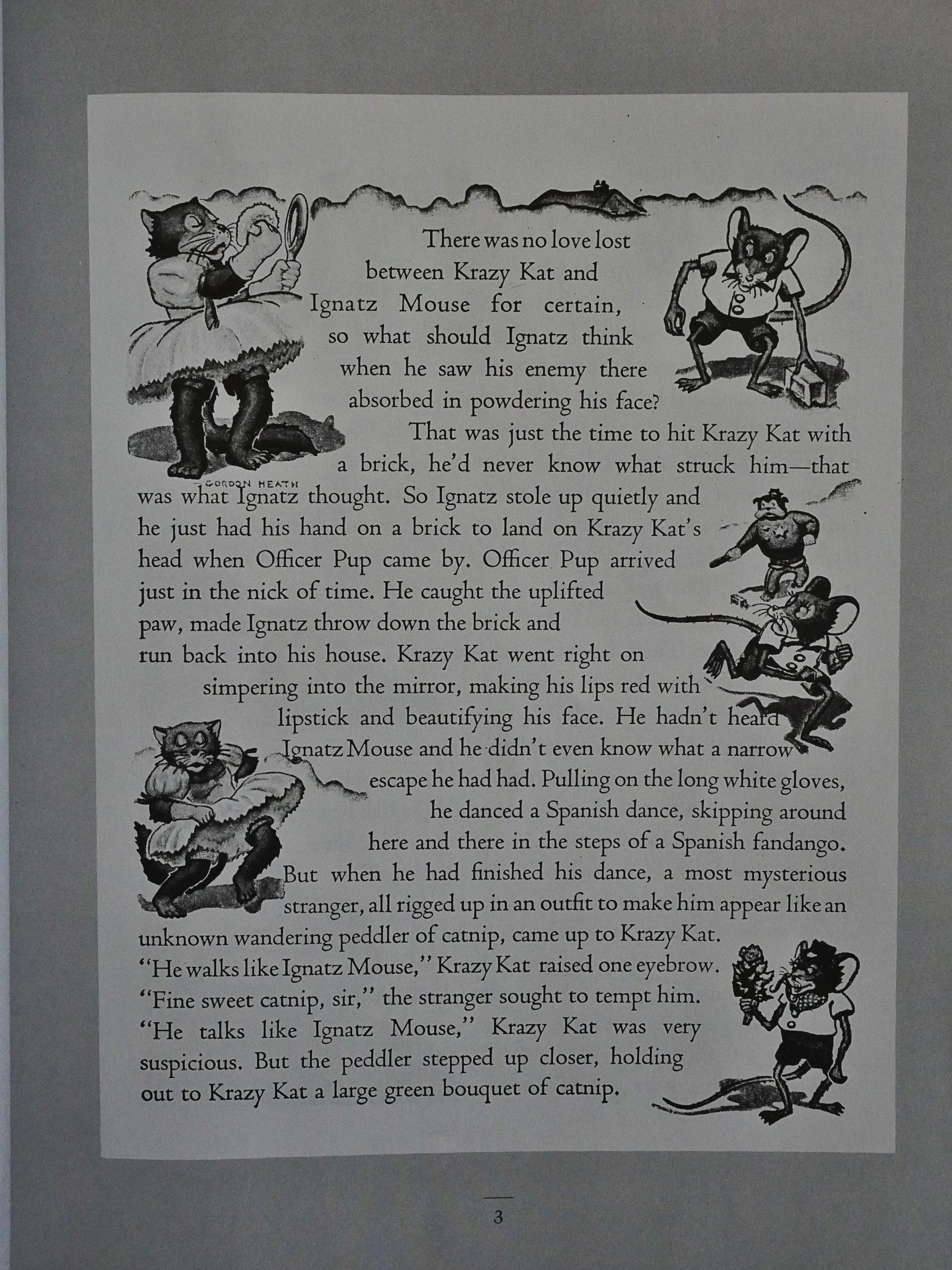

The final volume, from 1924, is apparently written by John Alden Carpenter, the guy who did the ballet? This isn’t stated explicitly, but I find no other way to interpret the introduction. It’s drawn by Gordon Heath, and I think it demonstrates what a horrible, horrible strip Krazy Kat would have been if Herriman wasn’t the one to do it. I mean, the artwork’s horrible, but the text is 10x worse.

*shiver*

We are talking in the majestic plural.

The “debaffler” pages are pretty informative, but sometimes Blackbeard feels compelled to use the space to make some jokes of his own.

They’re… not as good as Herriman’s own jokes.

This is a recurring problem with reprints of older, funny comics: The people writing the editorial material feel compelled to bubble over with bonhomie and mirth (WE ARE WRITING AN INTRODUCTION FOR A FUNNY COMIC BOOK! CAN YOU BELIEVE IT! IT IS SO FUNNY!) and it’s usually a total drag.

The last volume was published by Eclipse in 1992, and they were in severe economical problems, so I’m guessing it was more that than horrible sales. But I have no idea.

More than ten years would pass until somebody started reprinting Herriman again, and it was Fantagraphics that picked up the thread. They started, sensibly enough, with 1925, and continued until the end before they went back to 1916 and come full circle:

Fantagraphics will be collecting these first nine years of Sundays into three volumes comprising three years apiece, starting with the very first Sundays from 1916 through 1918, and incorporating all the original articles and special features from the first edition, including rare art, series editor Bill Blackbeard’s definitive historical overview The Kat’s Kreation, and updated and expanded DeBaffler endnotes explaining some of the arcana behind the strip’s jokes.

So, three volumes collecting these nine Eclipse volumes. By this time, tear sheets had been found for most of the strip’s run, so better reproductions were possible.

I don’t have the Fantagraphics editions of these years, but I do have the 1925-1944 books, and they are, of course, wonderful, too.