Total Eclipse (1988) #1-5 by Marv Wolfman, Bo Hampton, Rick Bryant, et al.

This series was meant as a celebration and a ratcheting up of the Eclipse comic book comics line: Line-wide crossovers were all the rage at the time, and Eclipse even got the writer for DC Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths to write this series. It was a great success for DC; this was the end of another chapter of Eclipse’s story.

Eclipse had concentrated for the past few years on publishing action/adventure/super-hero periodical floppies (bi-weekly, monthly, bi-monthly, whatever) to some success. That is, Airboy and Scout were successes; the rest not so much.

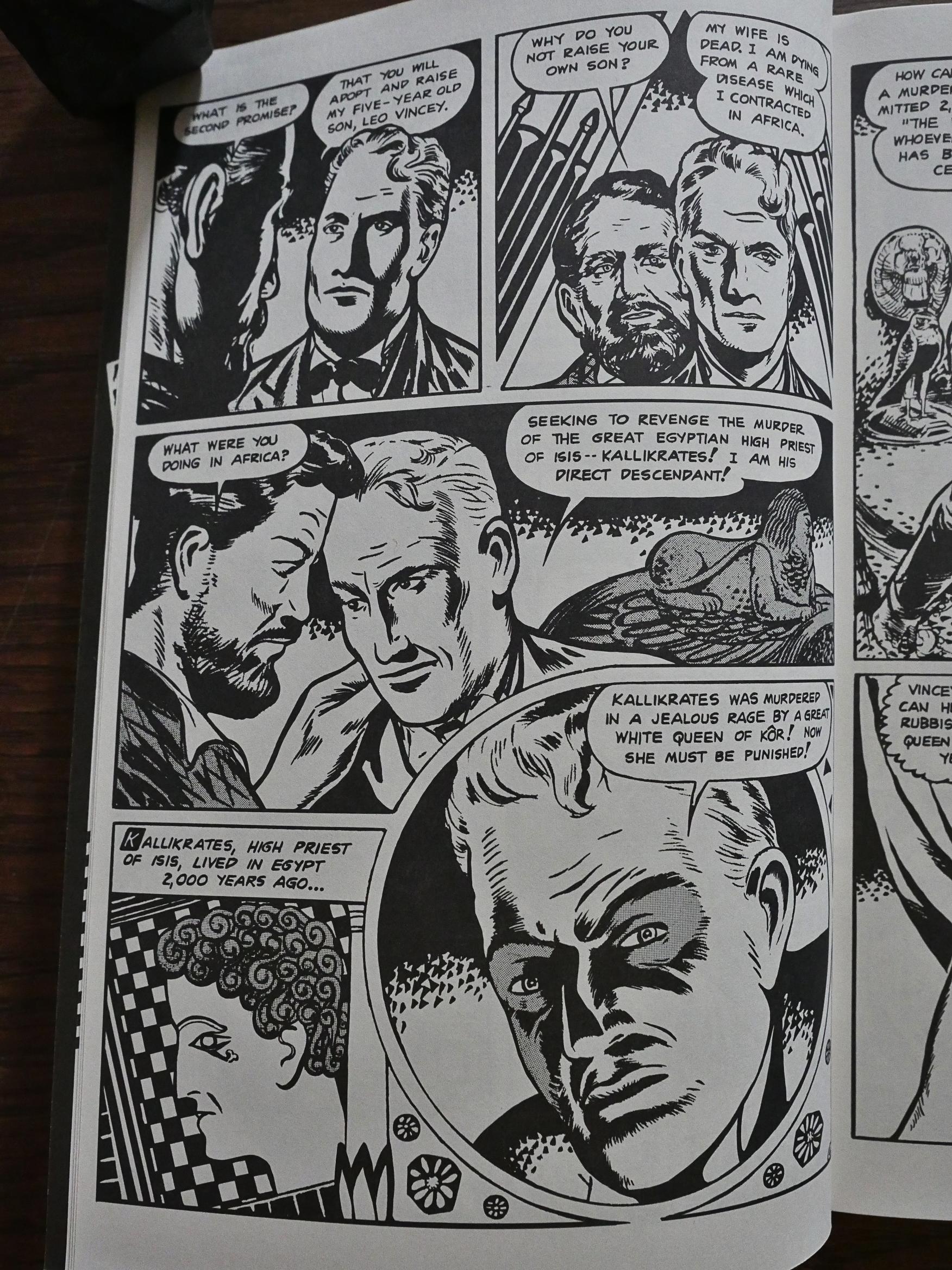

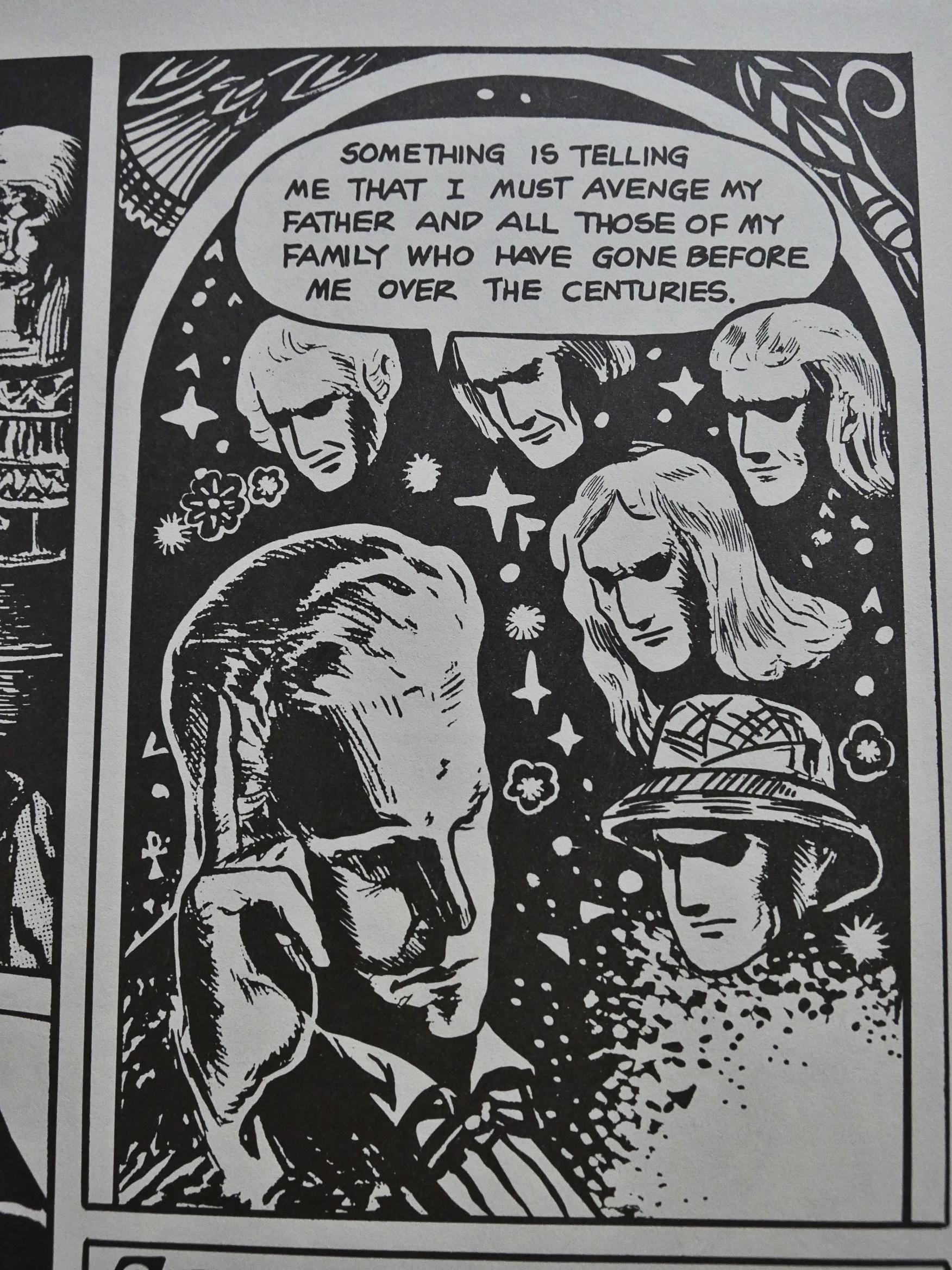

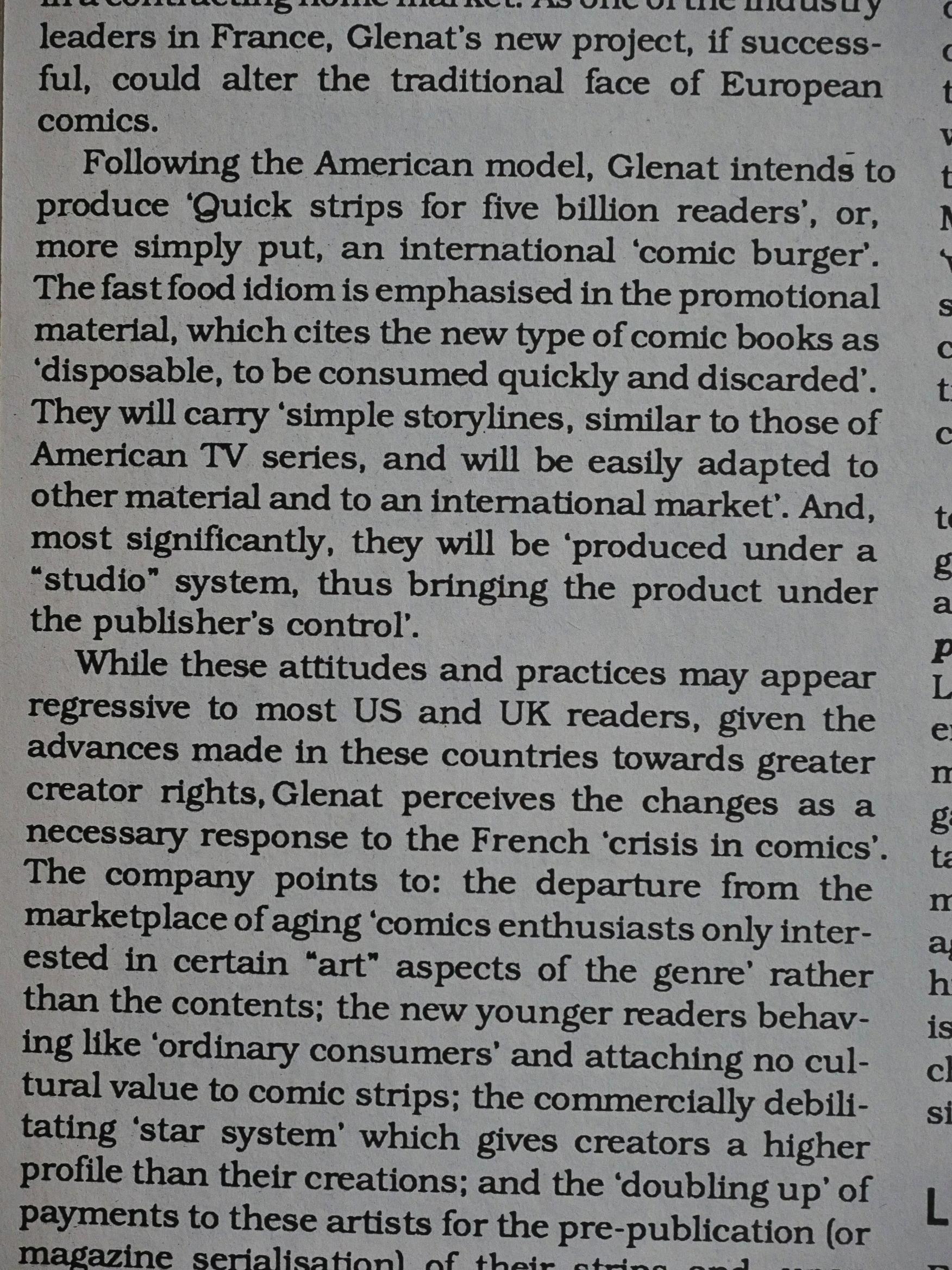

After Total Eclipse, no further series like that would be debuted. From now on, Eclipse would concentrate on graphic novels, one-shots and series reprinting things from other places in the world (mostly Japanese, but also a smattering of European and Argentinian comics).

(Not that Eclipse stopped publishing these comics like *snap*: Many of them continued their long runs for quite some time, but no new ones were developed.)

In one way, you could say that Eclipse were returning to their roots: They started off being a graphic novel publisher. But while the original push was all creator-owned, many of the graphic novels over the following years are licensed properties like James Bond, The Hobbit and that Anne McCaffrey Dragon thing that I forget what is called.

We have to wait until the Twilight of the Eclipse (i.e., 1992) for the next attempt at launching domestic periodic floppies (and they’d fail).

This is also a personal watershed of a kind for me: I had read pretty much all Eclipse comics up until (say) 1984, a smattering of their comics until now, and virtually none of their comics after this, so I’m pretty curious what these comics are going to be like.

ANYWAY!

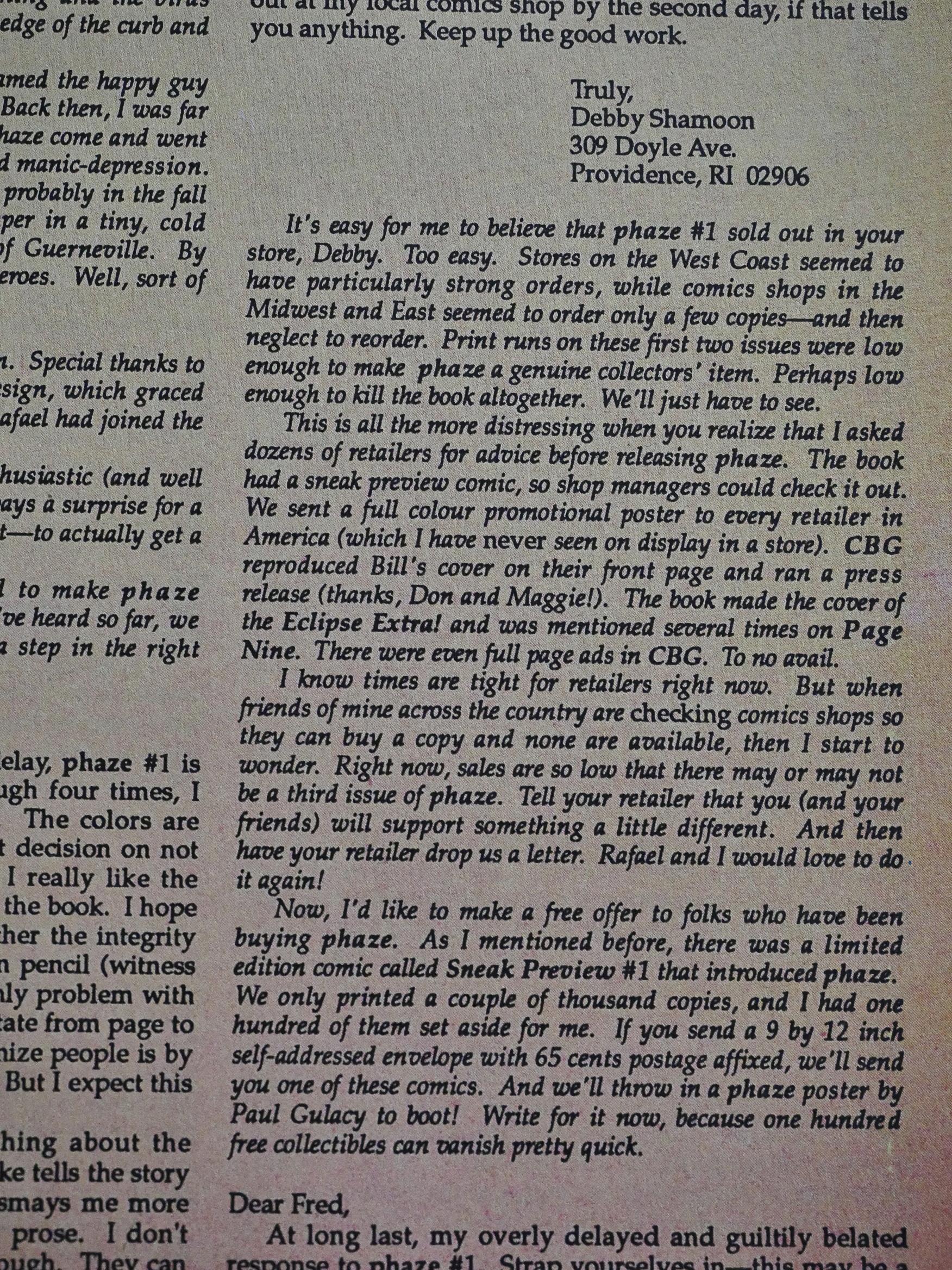

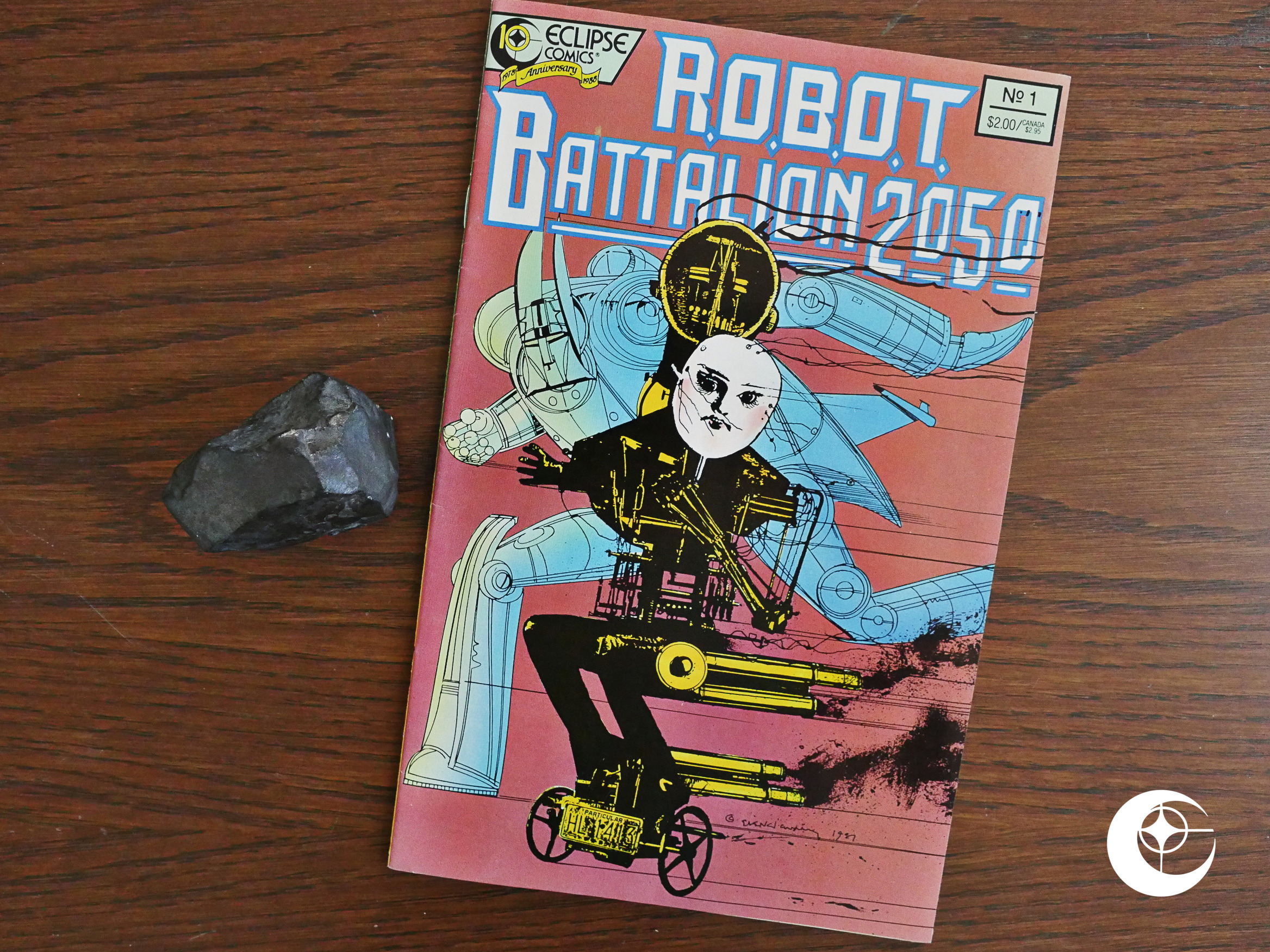

Let’s talk about this series. It’s five 48-page squarebound standard-size comics (i.e., the “prestige” format that Frank Miller’s Dark Knight Return popularised). Most of the issues were released with three or four months passing between them, which I would guess might have contributed to the (perceived) failing of this series. I have no idea what the sales numbers were, though, but I vaguely remember there being some muttering about this at the time.

It’s too bad I don’t have a complete run on Amazing Heroes digitised and searchable; there should be some chatter in there about the series.

Hm… sounds like a project.

ANYWAY!

Those … infinite worlds kinda remind you of Crisis on Infinite Earth, doesn’t it?

Weirdly enough, the Strike! storyline continues without a glitch from the Sgt. Strike one-shot.

But, really, there aren’t that many connections to the other books. We see a few “see Foo #bar” here and there, but a lot less than I would have imagined in this book.

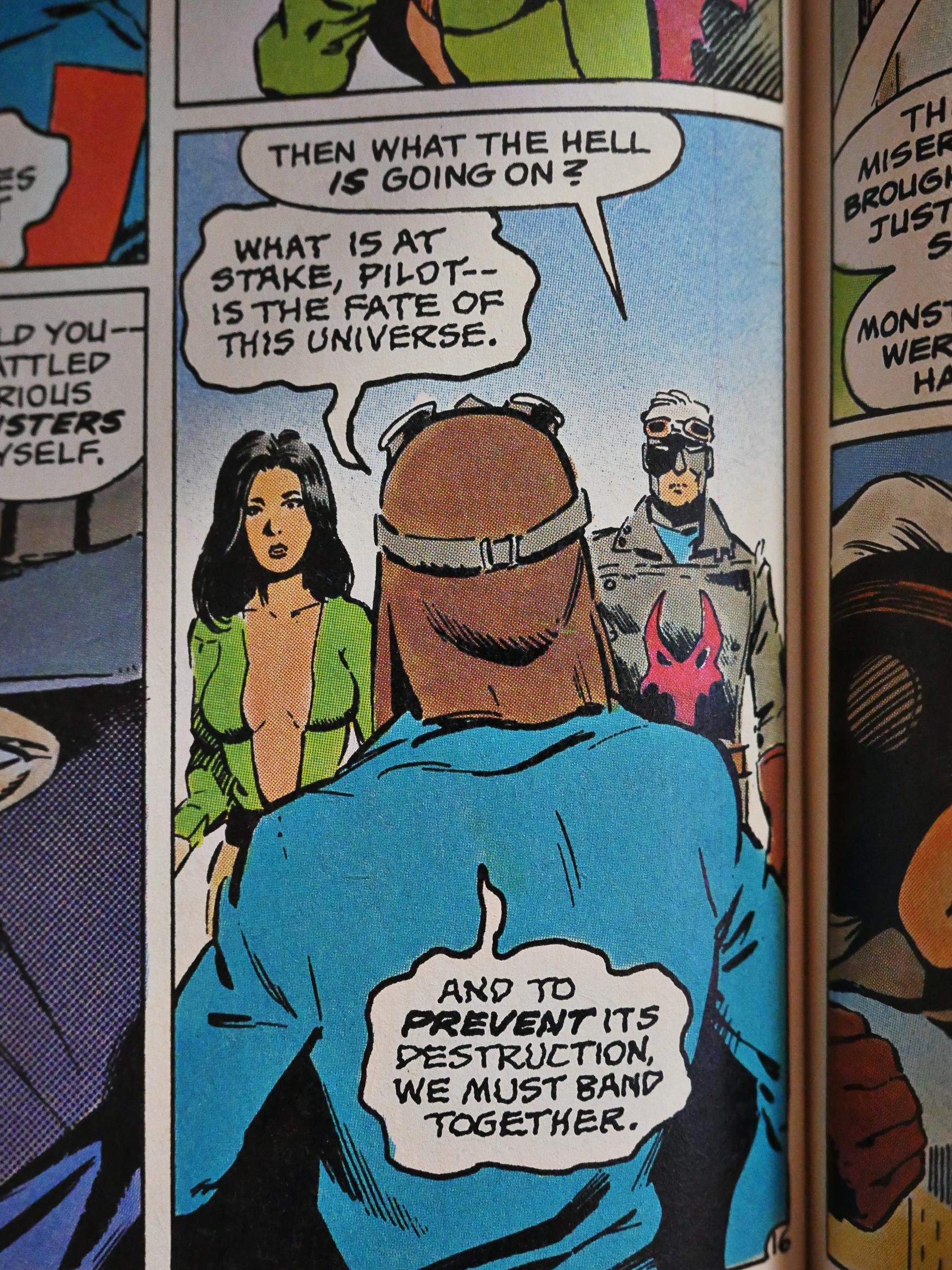

The selection of characters that appear here is also not quite what I would have expected. Basically, it’s everybody from the Airboyoverse, a few of the second-stringer 4Winds titles (Strike!, The Prowler), The Liberty Project, the New Wave characters and Miracleman. Many of these are owned by Eclipse in one way or another, or are from 4Winds titles that had ended. Characters you’d expect to pop up that would have made sense would have been DNAgents or Zot! or Pelleas and or Melisande.

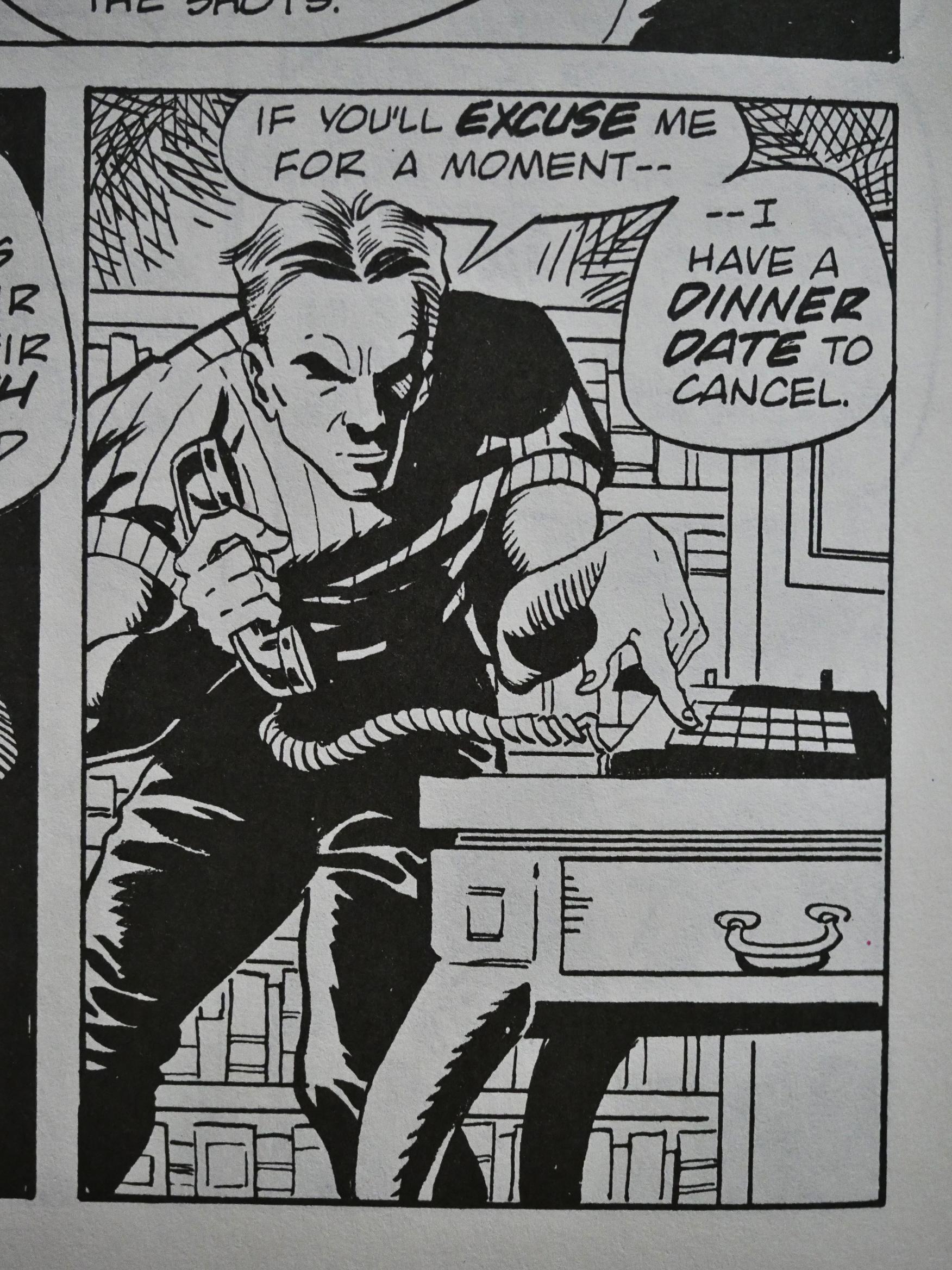

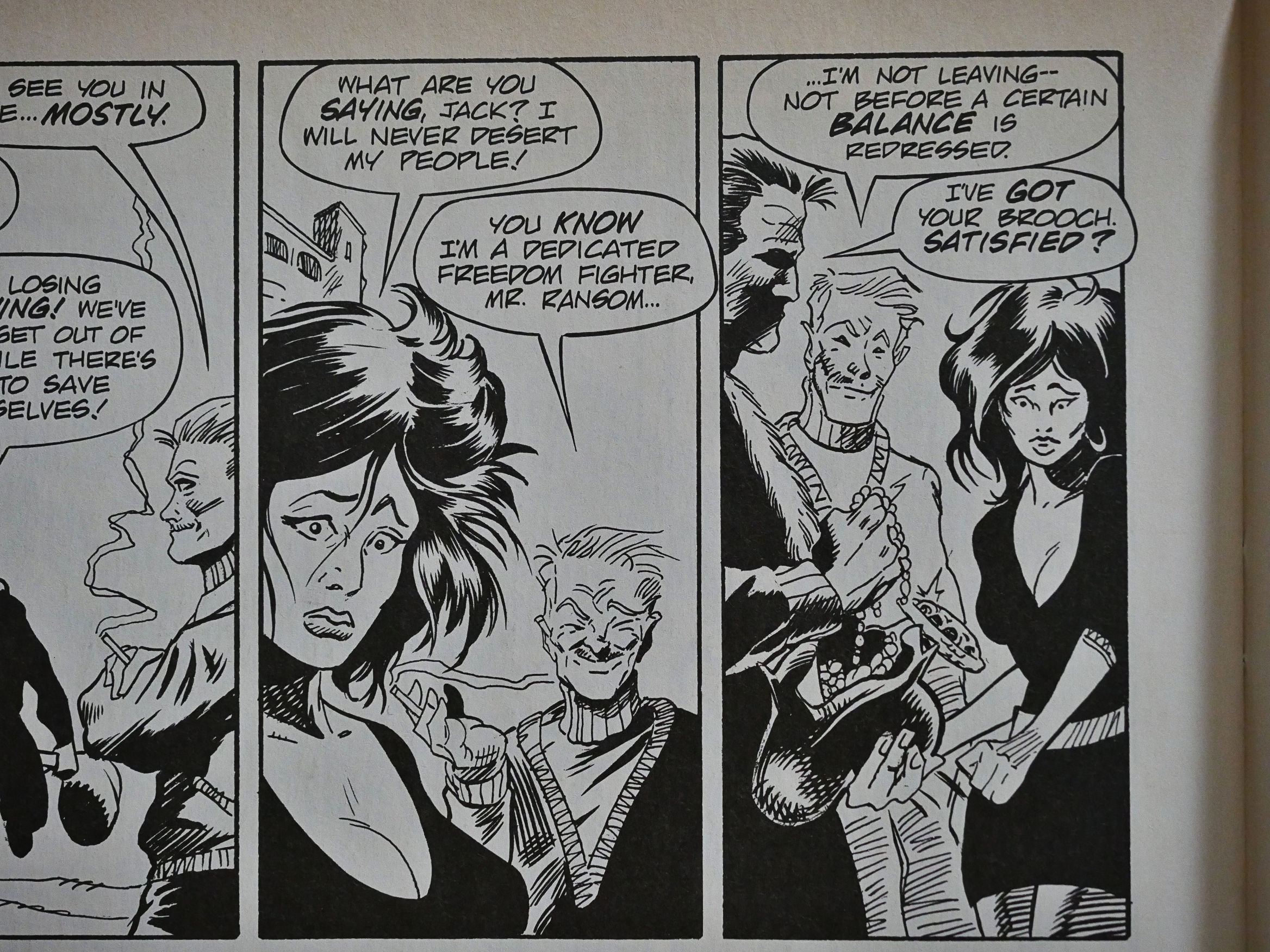

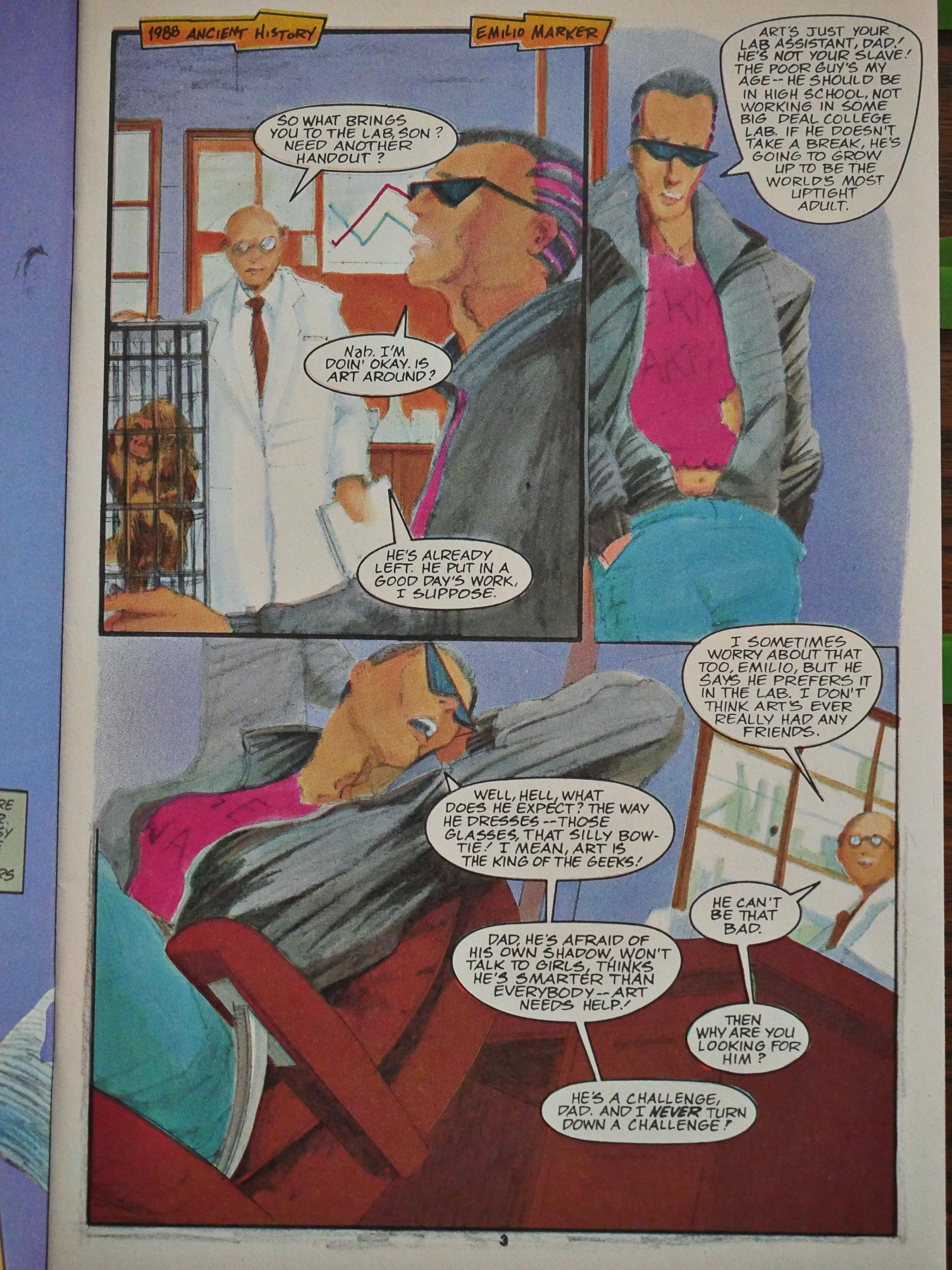

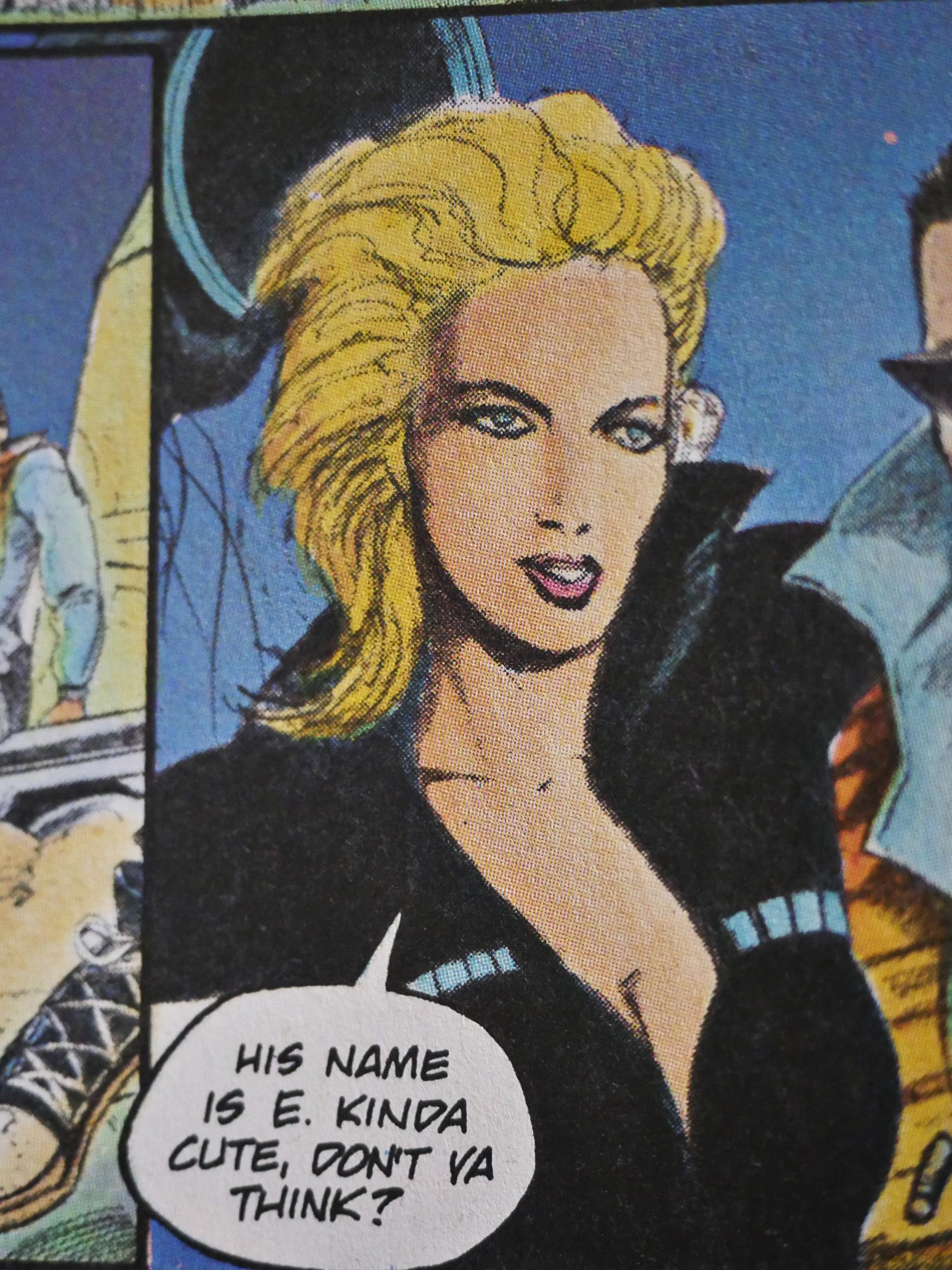

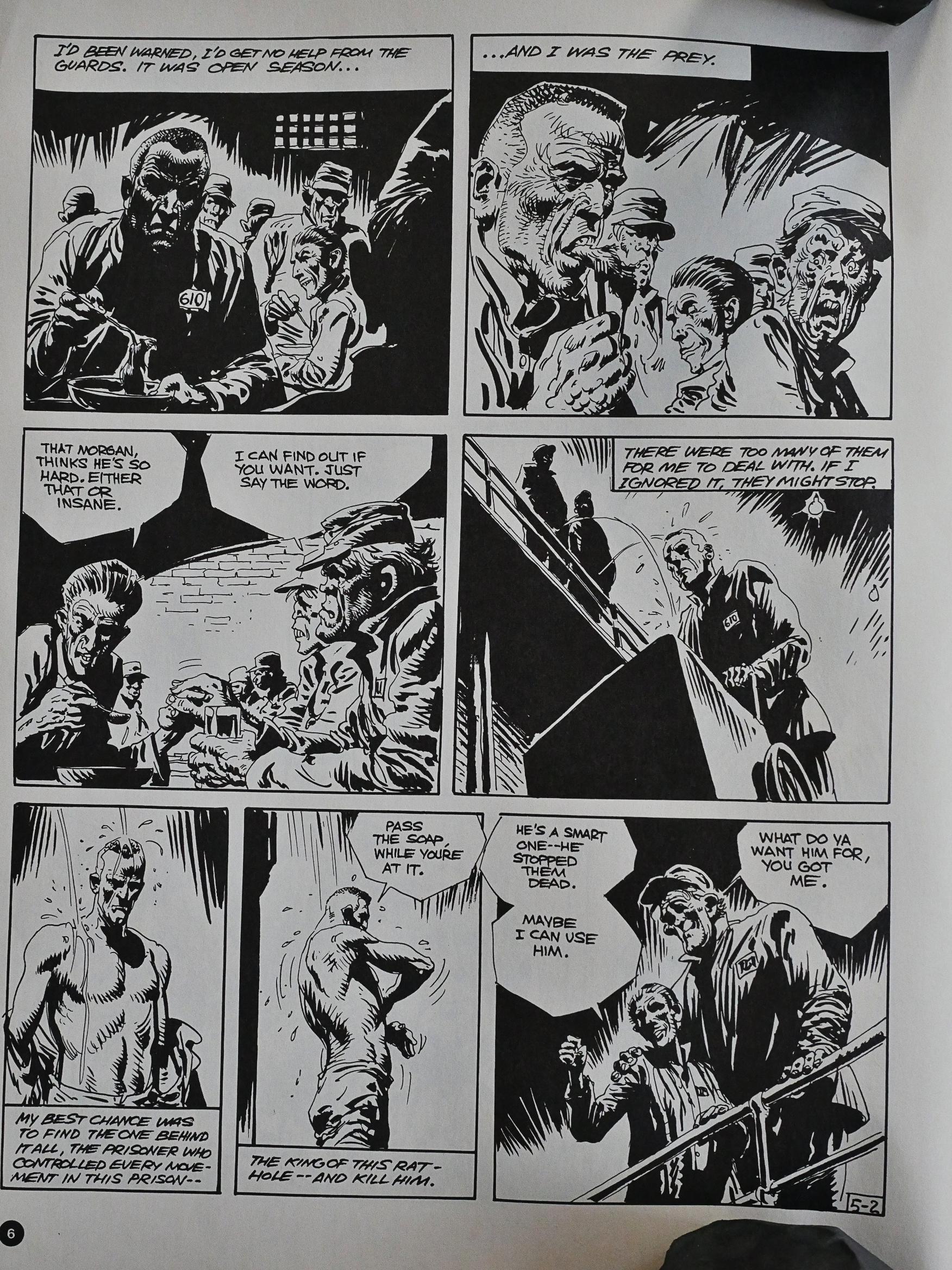

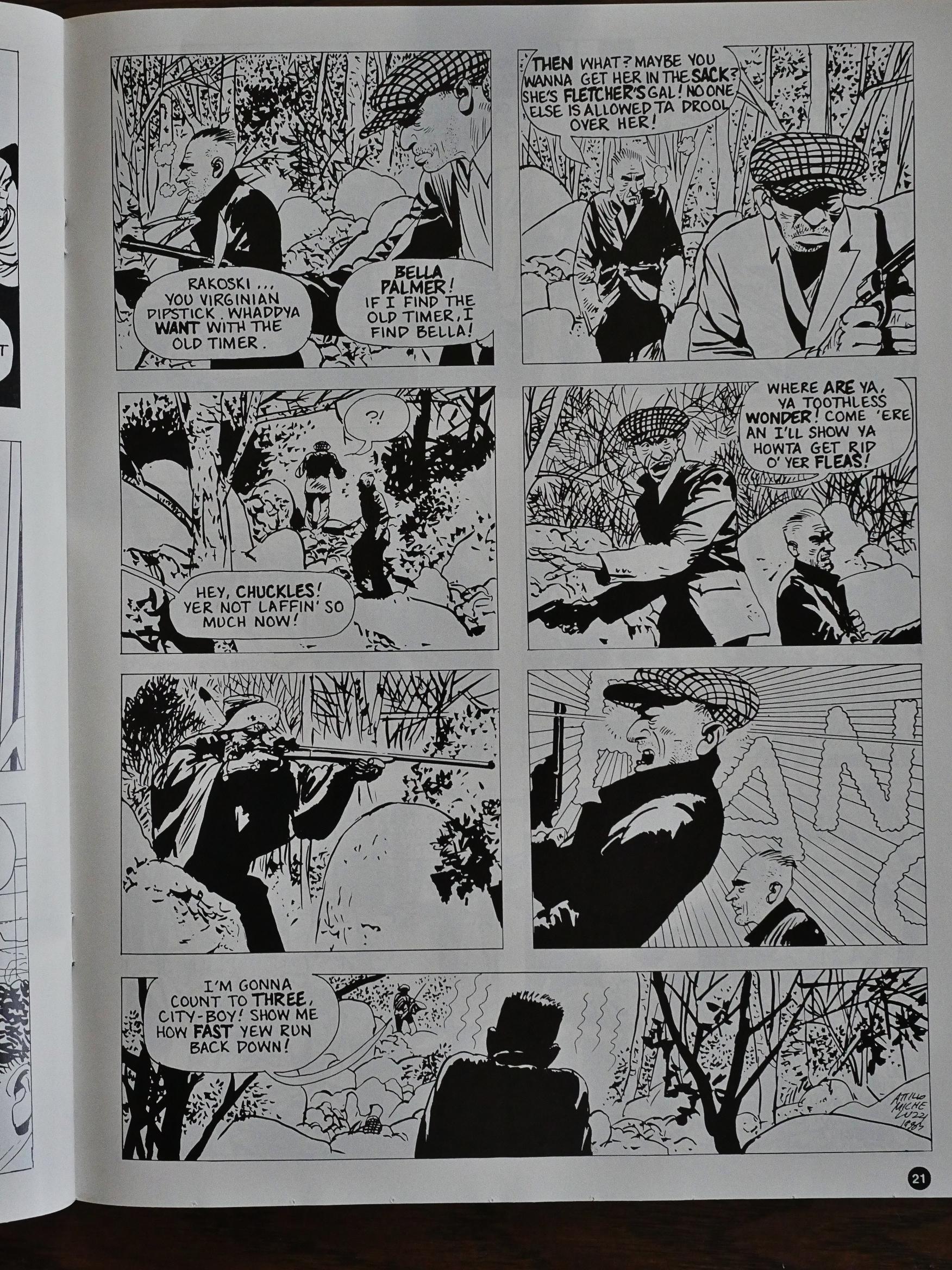

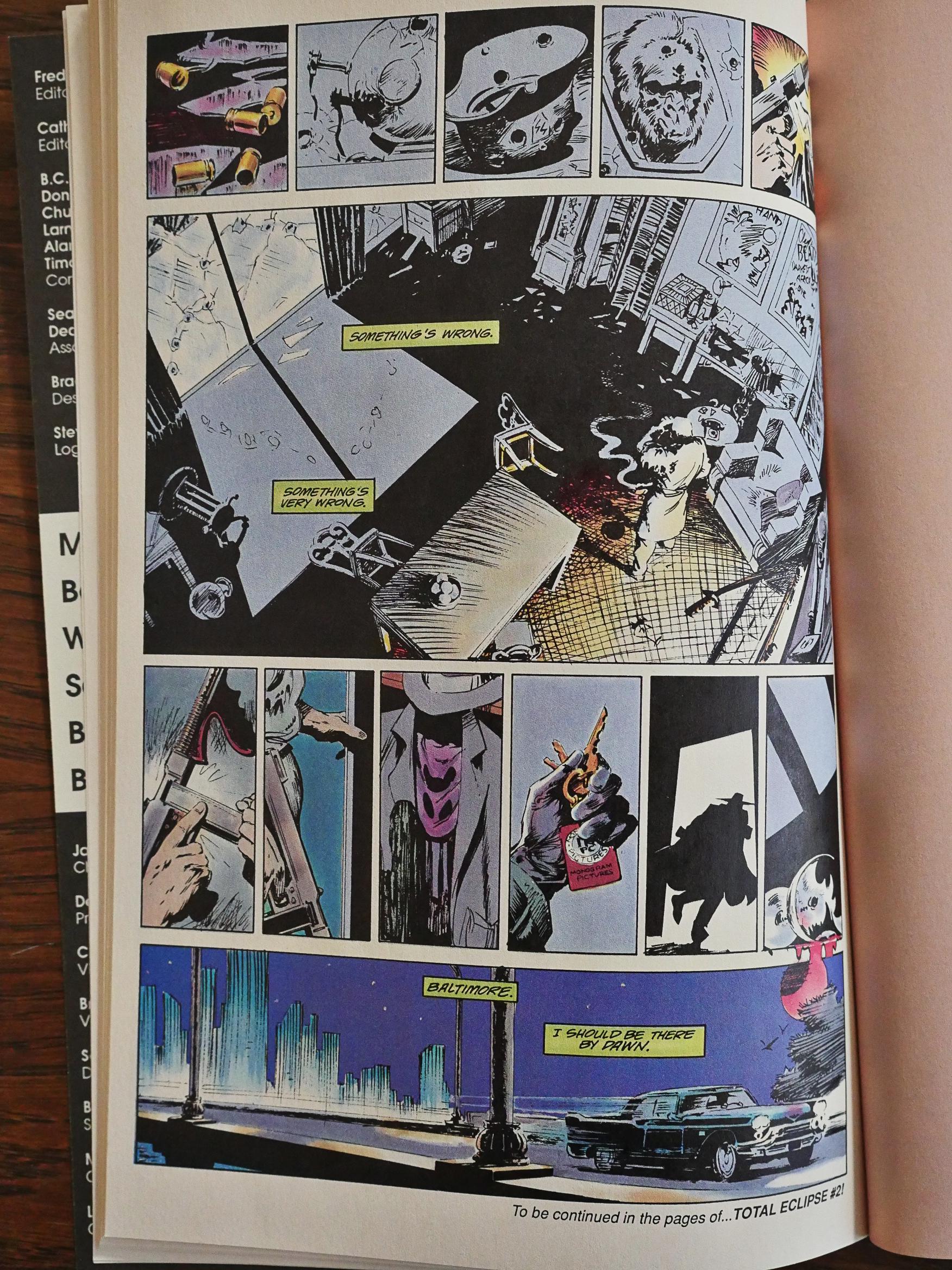

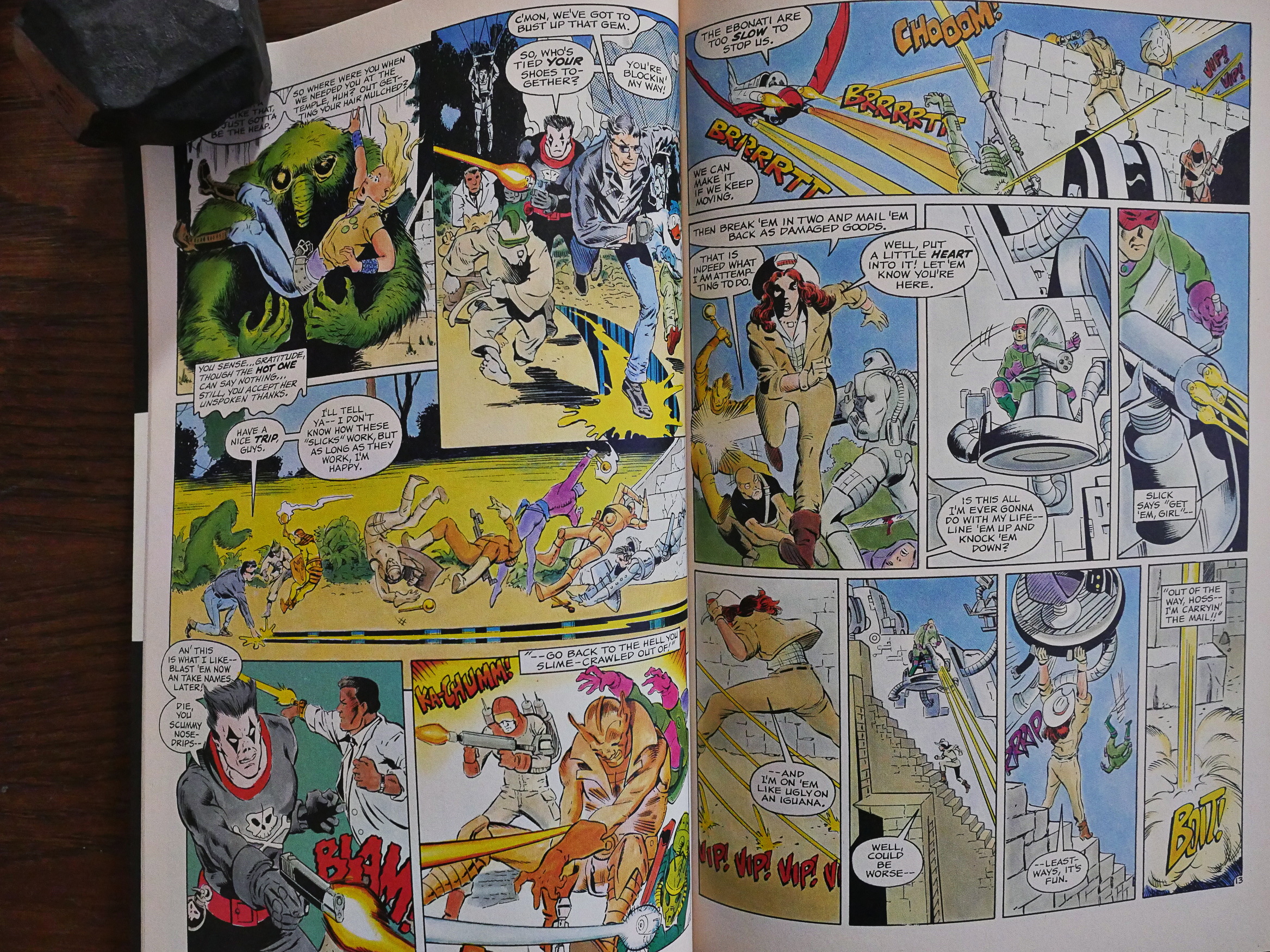

Each issue is about 30 pages of the main story, and then a ten page backup that concentrates on one of the characters within the Total Eclipse framework. It works really well and allows the reader to sample how the “real” creators handle the characters, like in this Prowler bit by Timothy Truman, Brent Anderson and Mike Dringenberg.

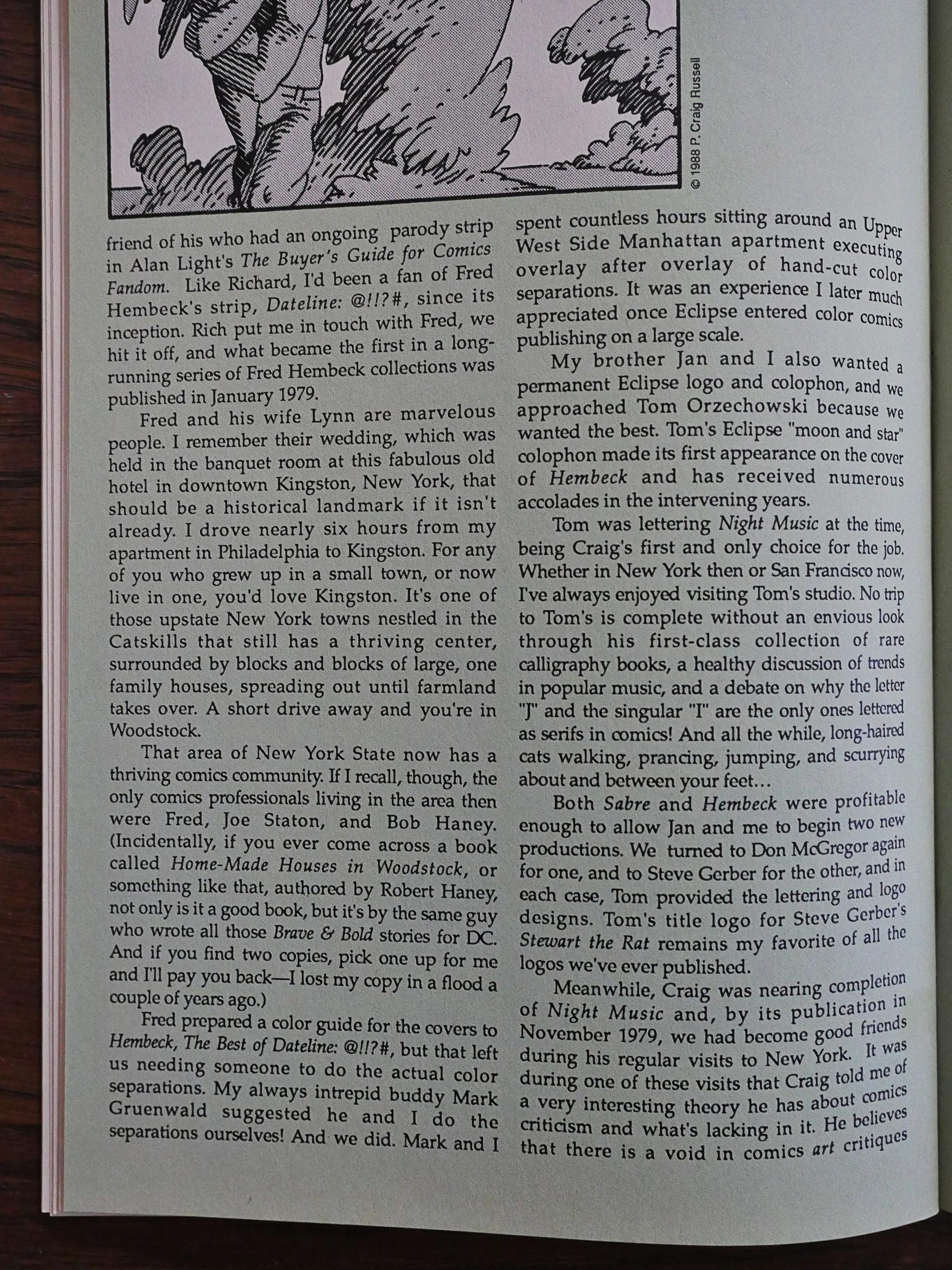

And finally, in every issue we get four pages of text by publisher Dean Mullaney. It’s both a personal history as well as a history of Eclipse Comics, and it’s quite interesting. We’ll return with some specifics later…

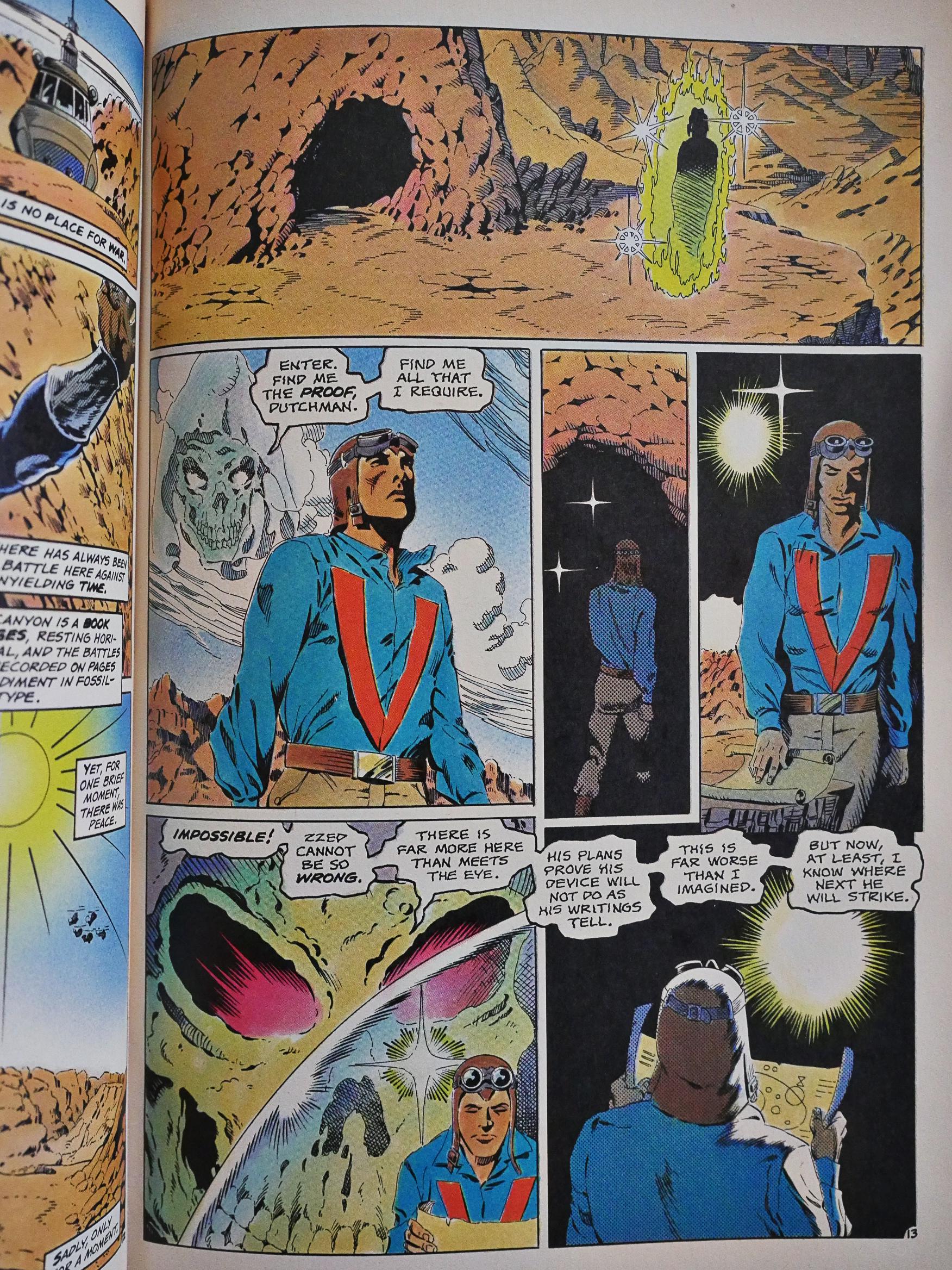

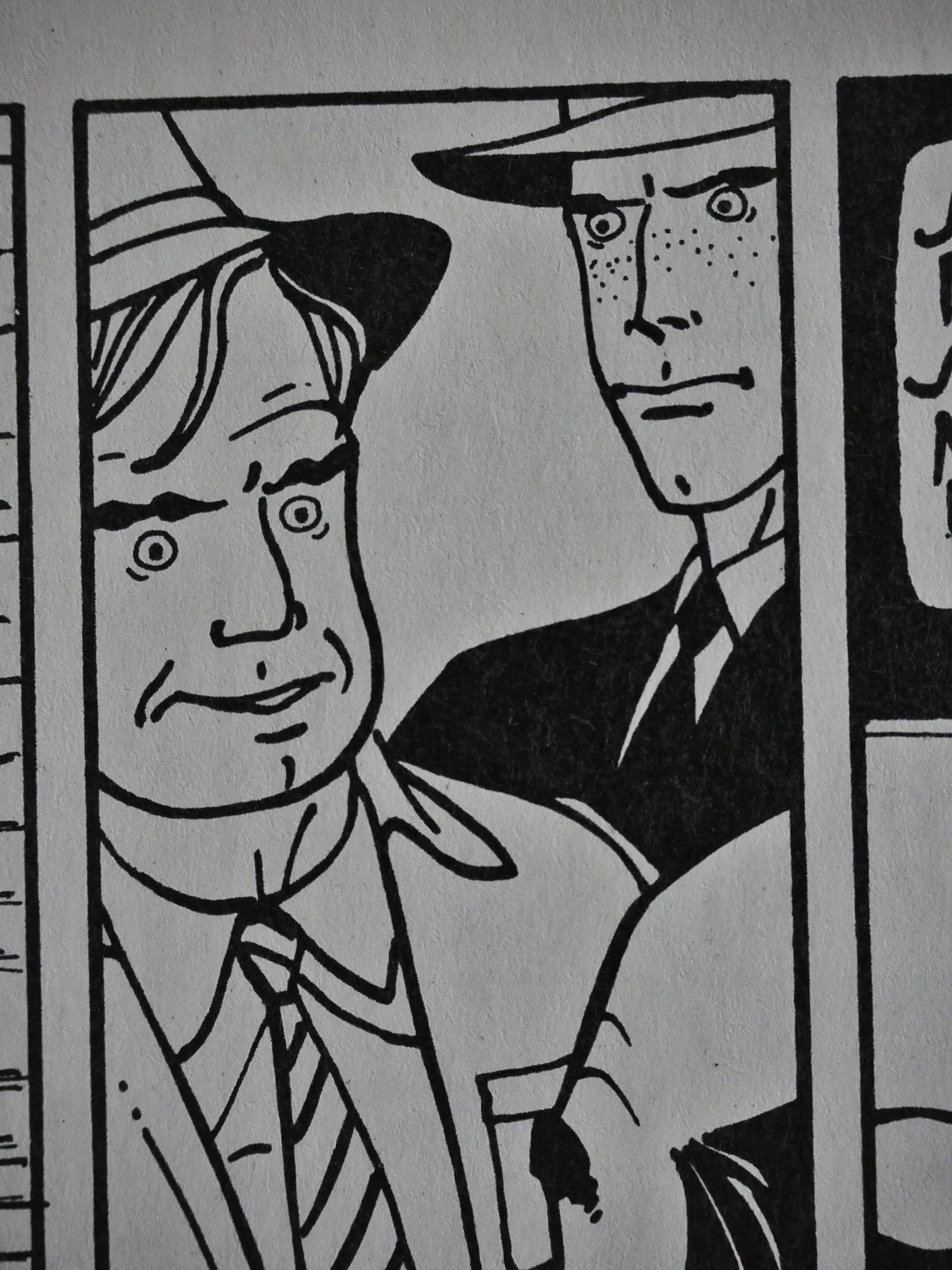

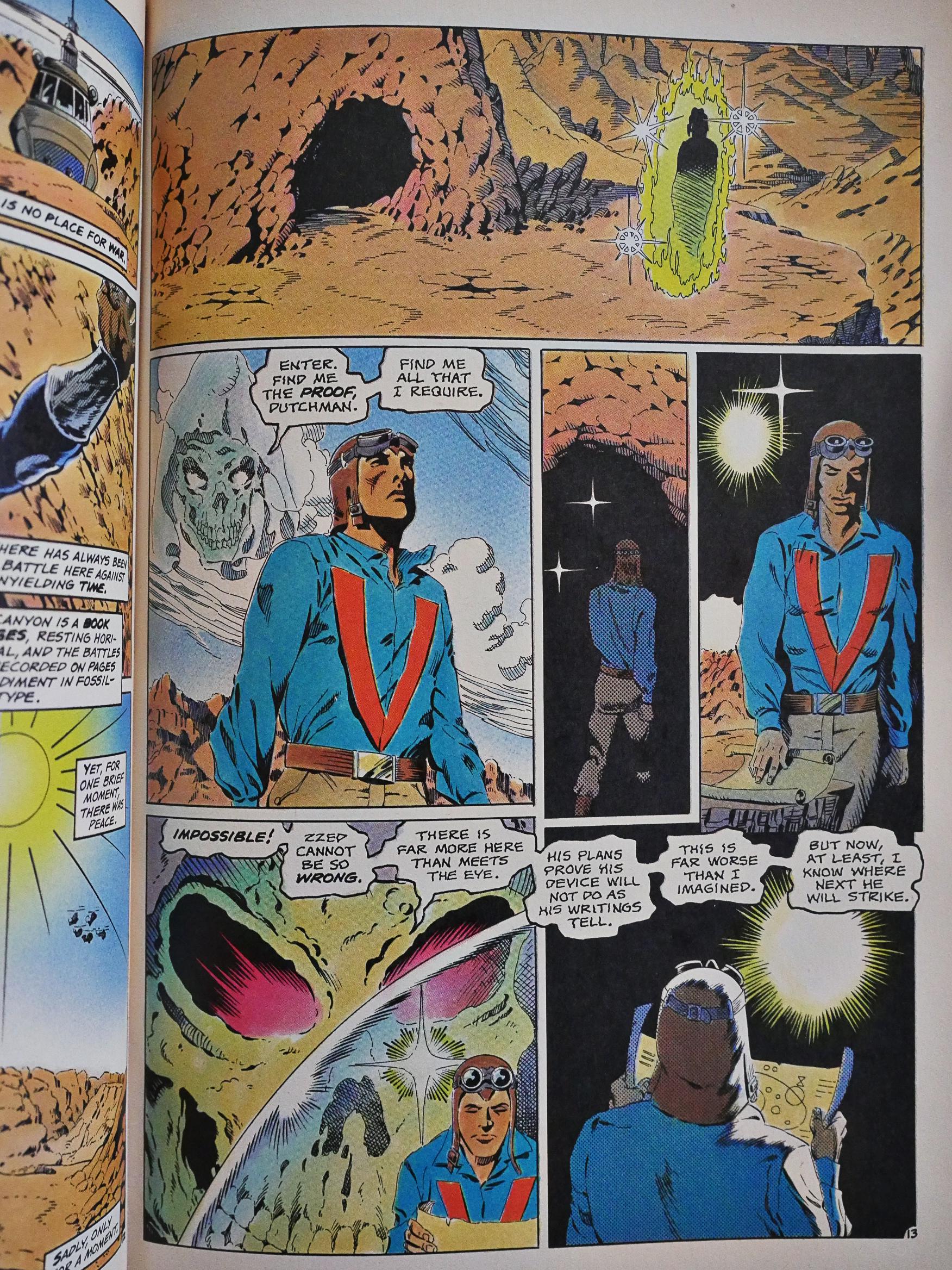

I enjoy Bo Hampton’s artwork in general, but I don’t think this is his best effort. He doesn’t seem to have an obsession with drawing all these characters (which seems very different from George Perez on Crises, for instance), so their faces in particular are often rather indistinct. The Dutchman’s face above… do any of the three renderings resemble each other much? No? Right. But Hampton’s still a pretty good storyteller, and I love that next-to-last panel on that page.

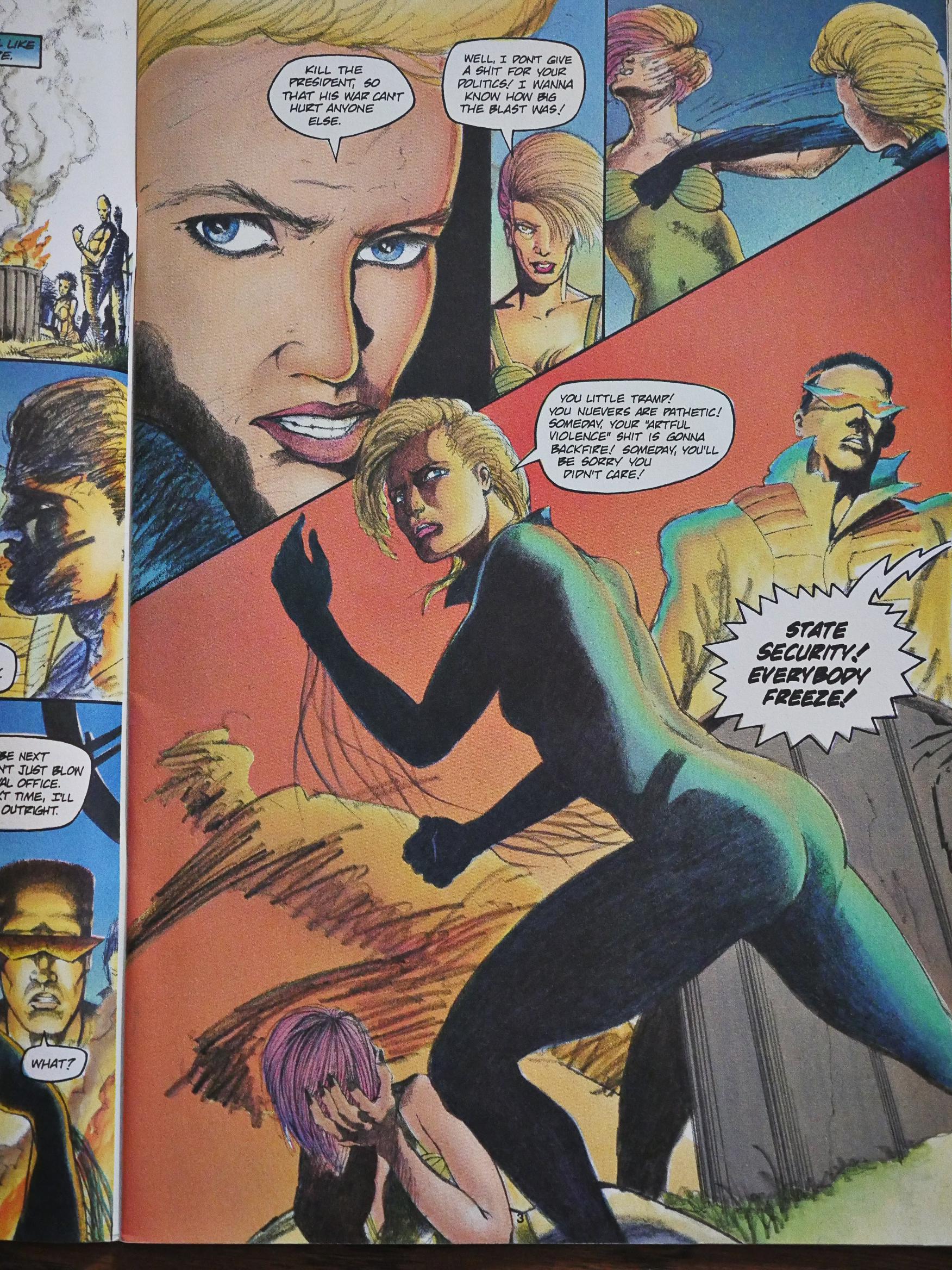

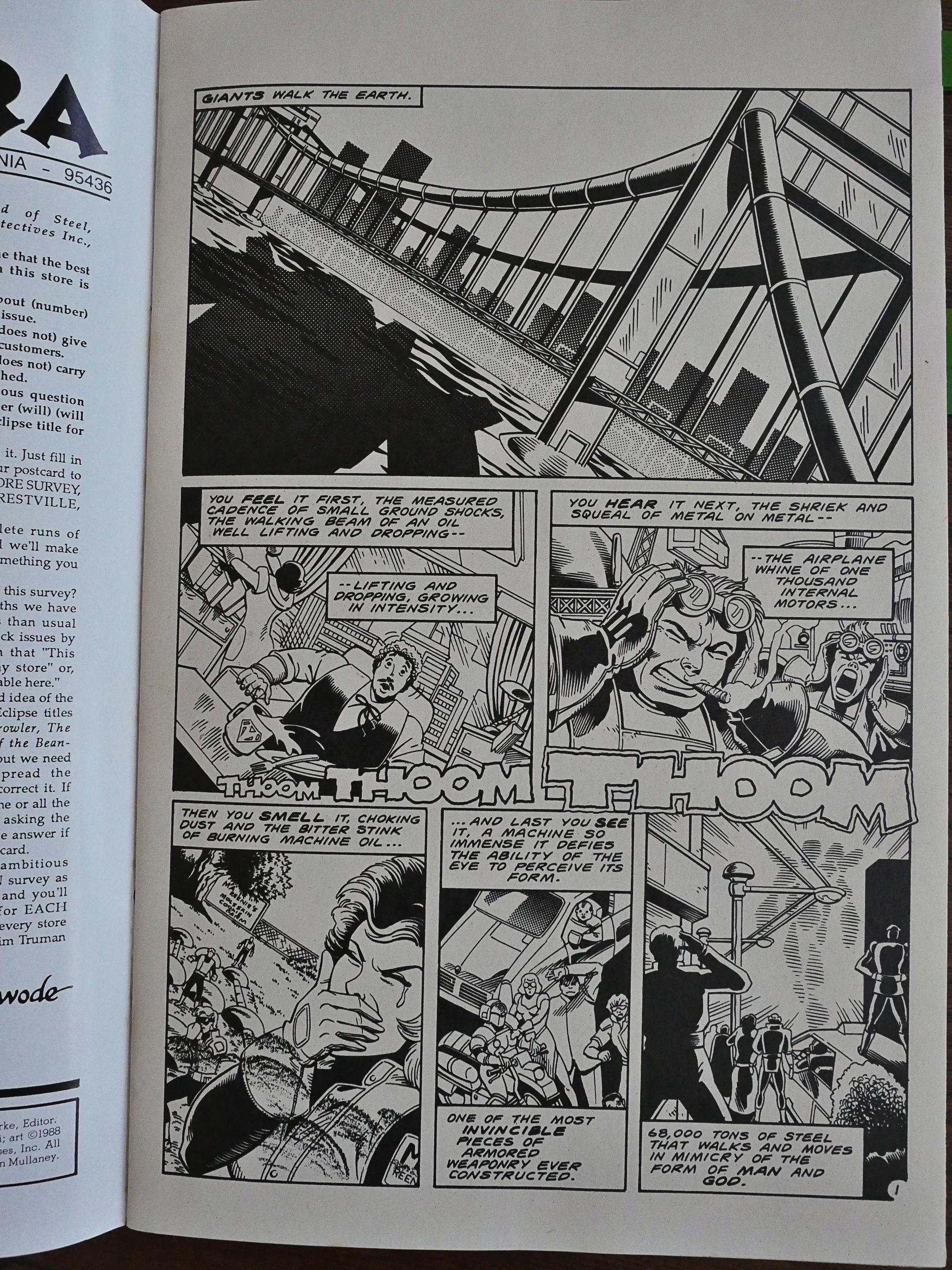

Oh. The story. When you make one of these crossover, you always have to put the entire universe in jeopardy, and Wolfman does just that.

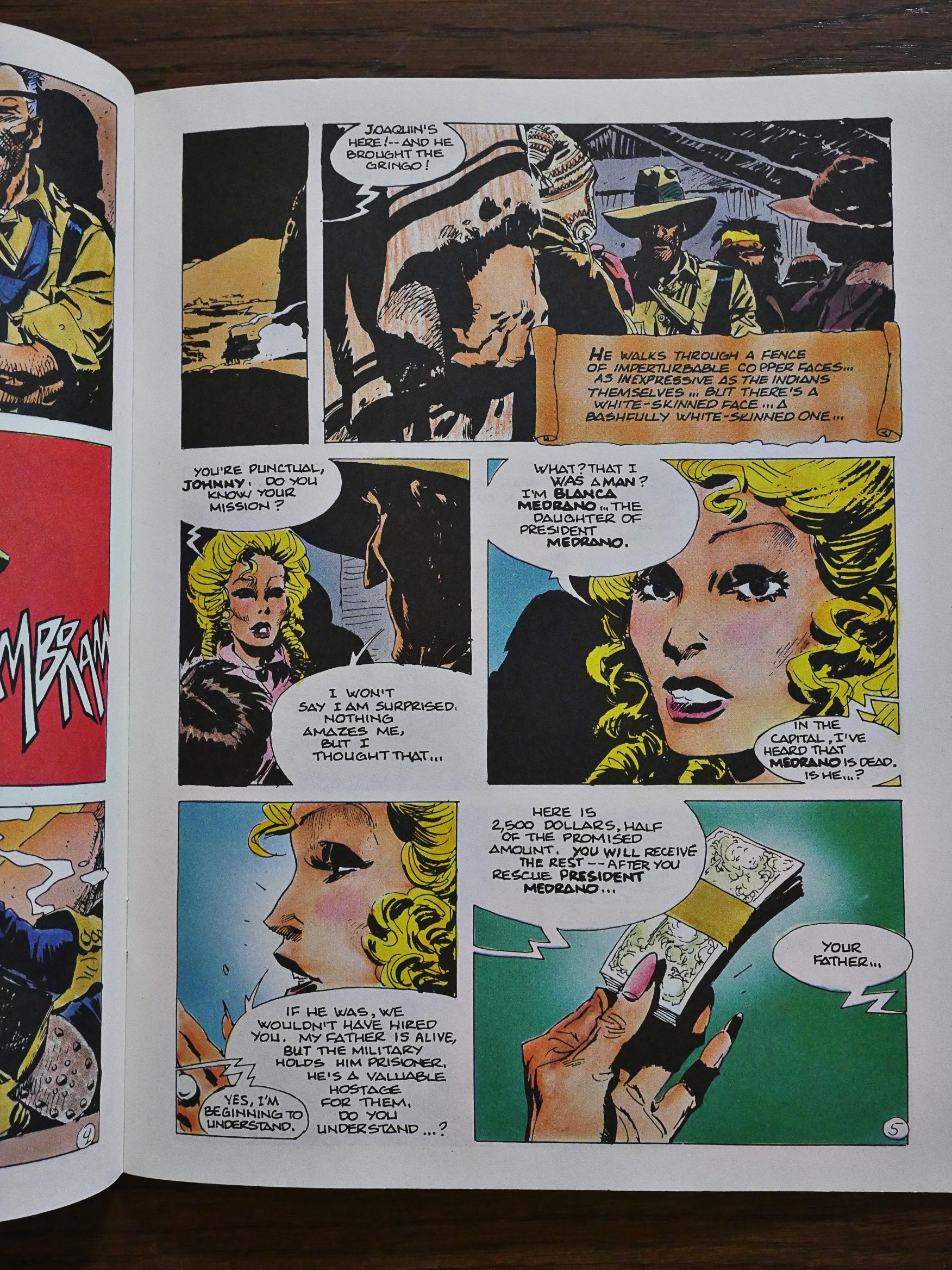

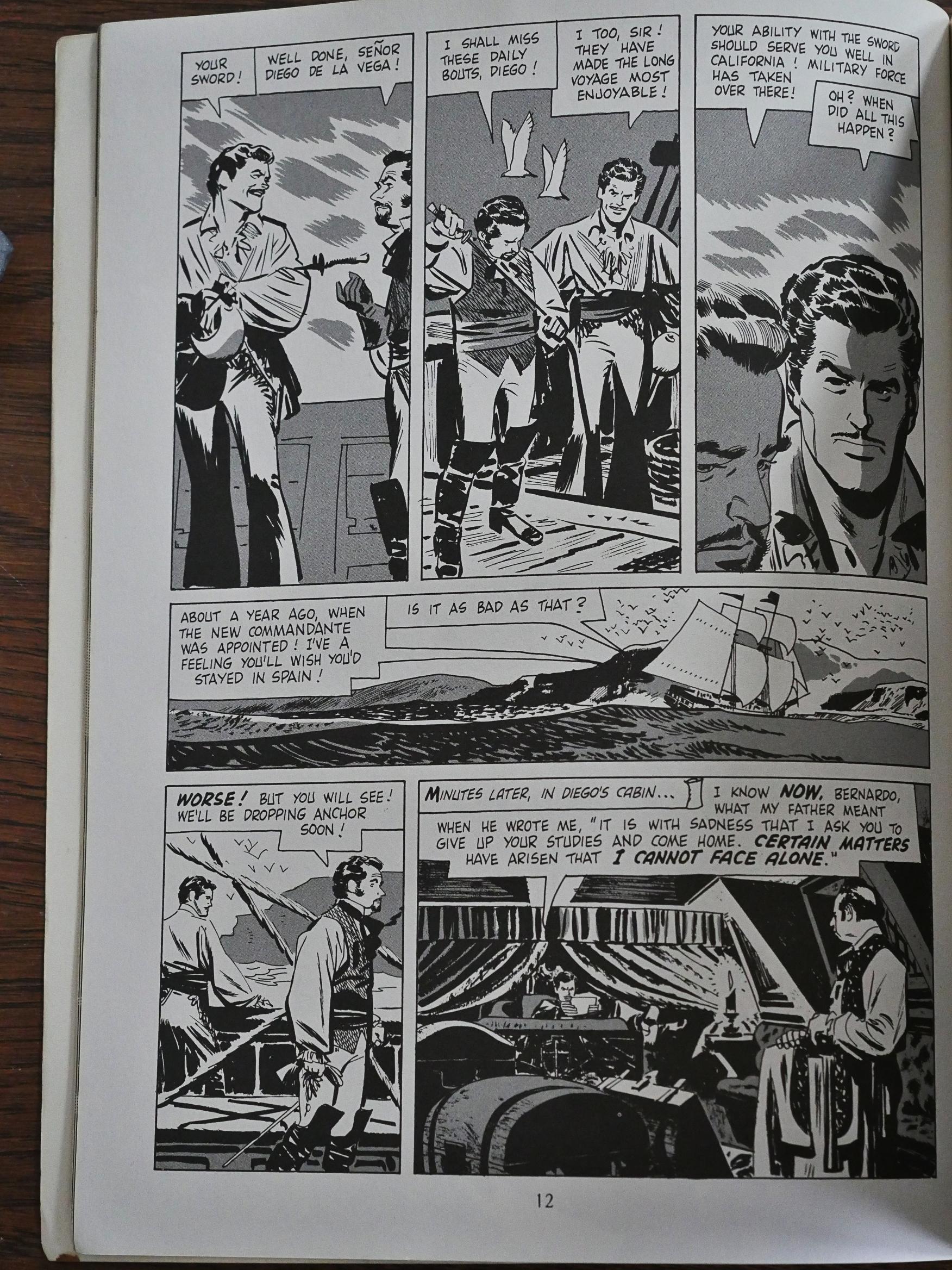

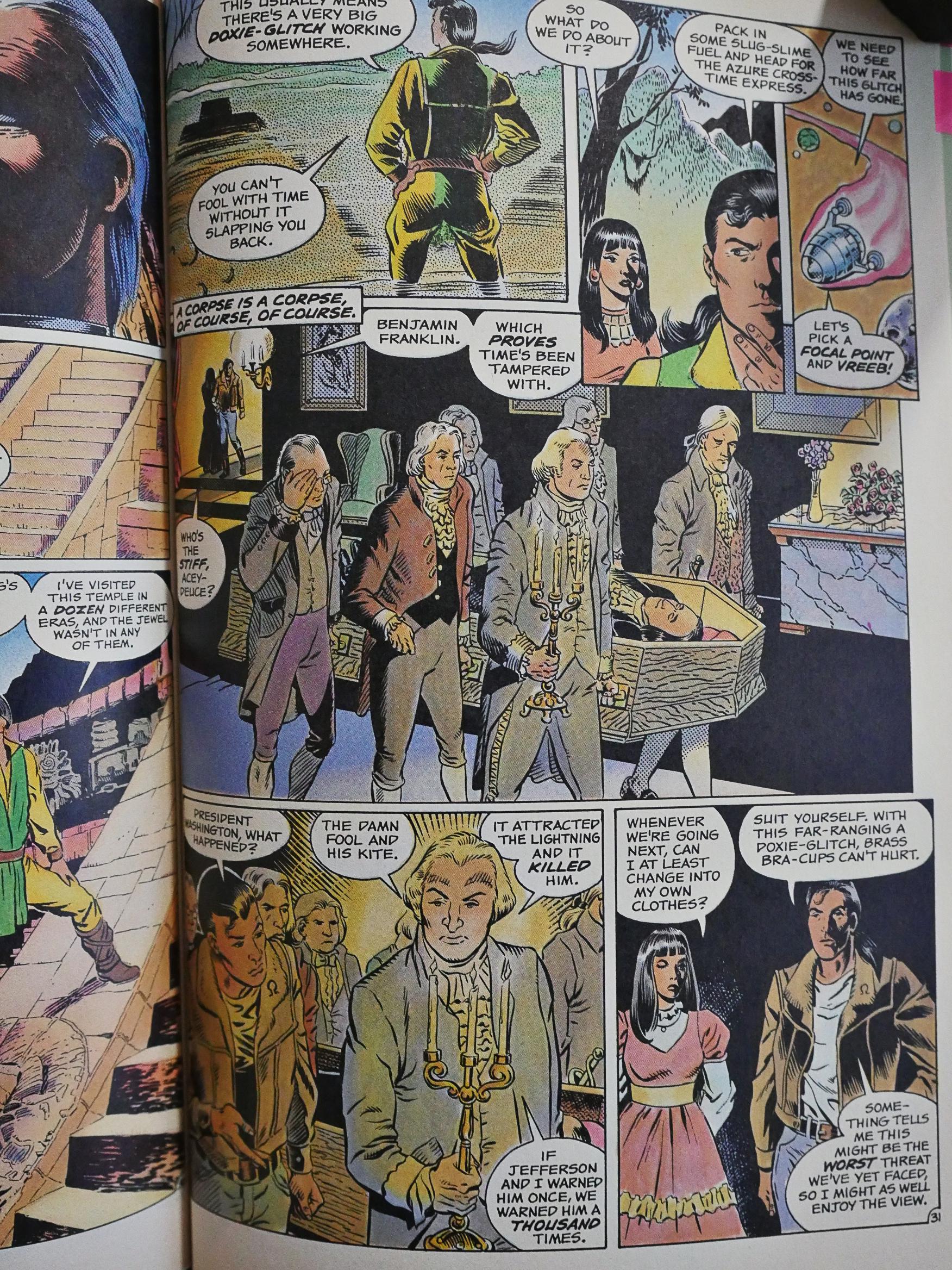

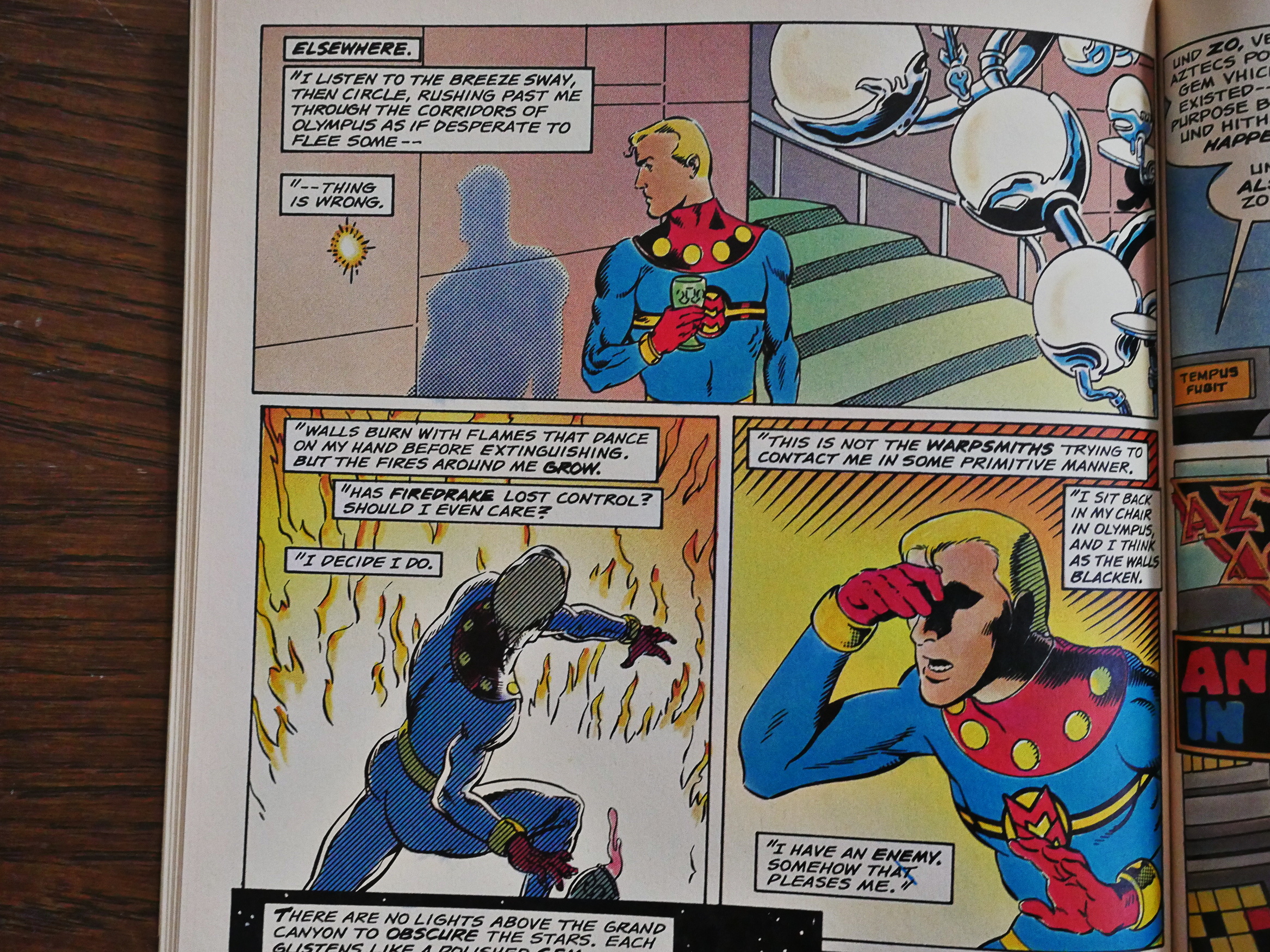

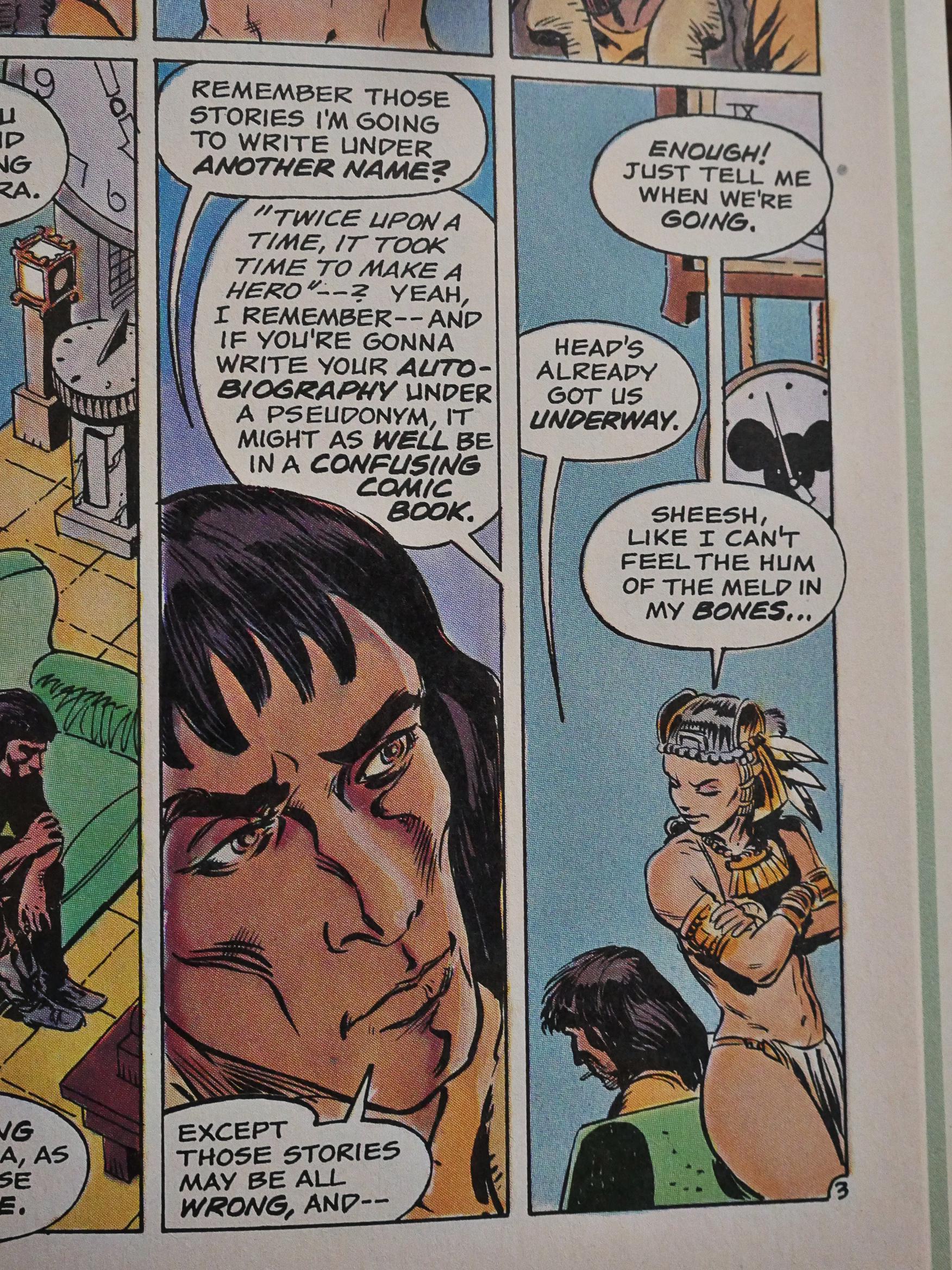

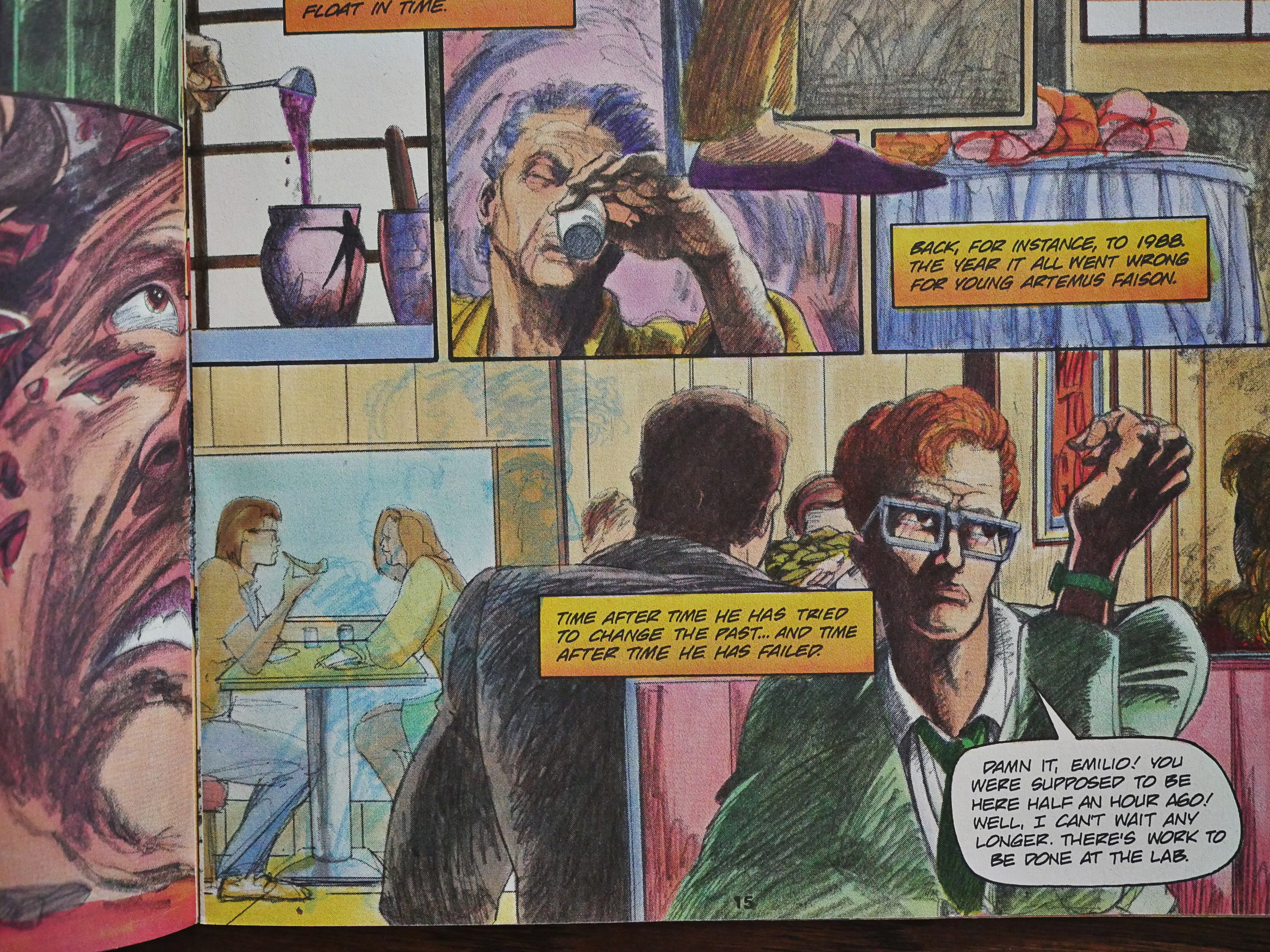

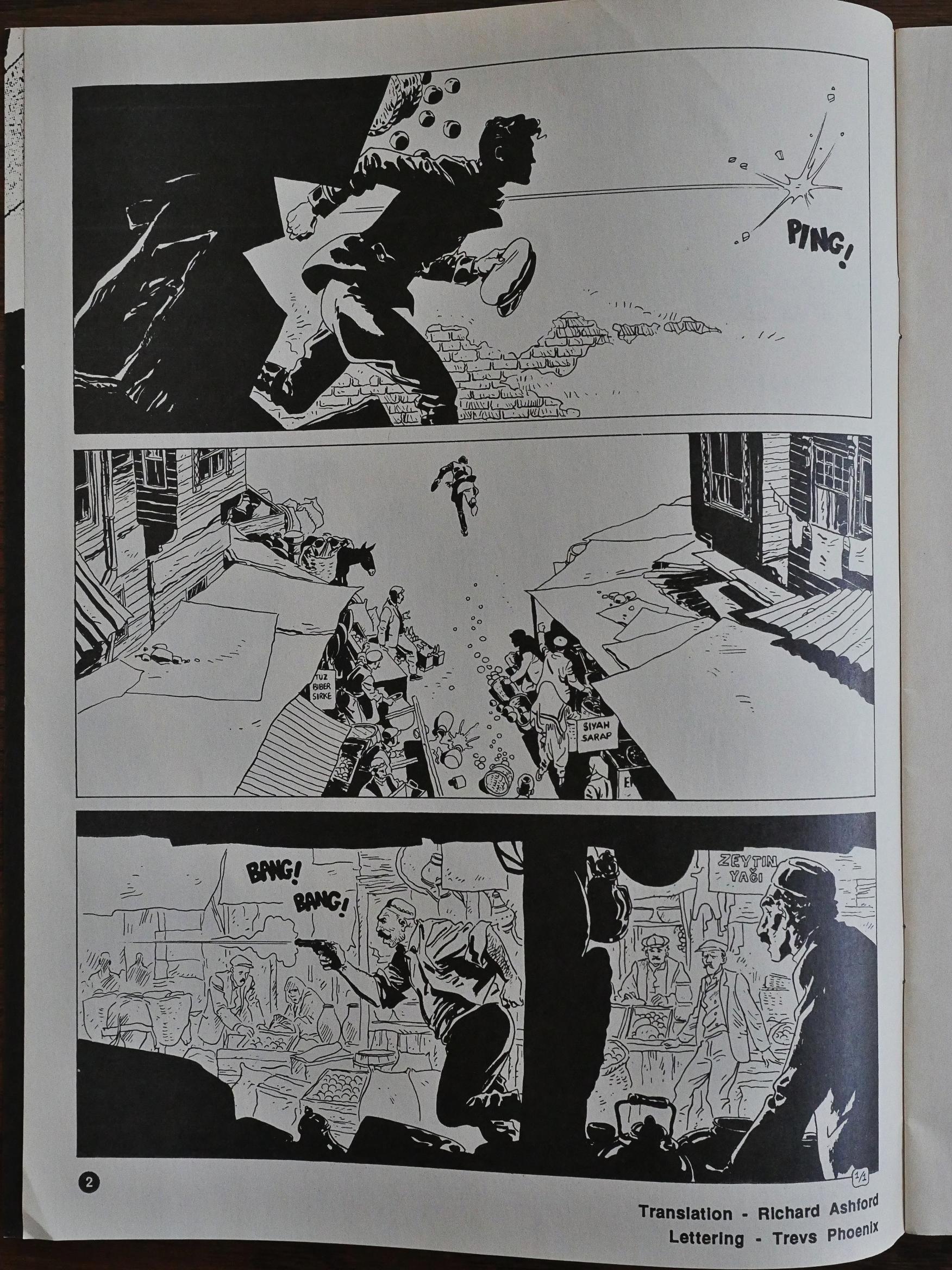

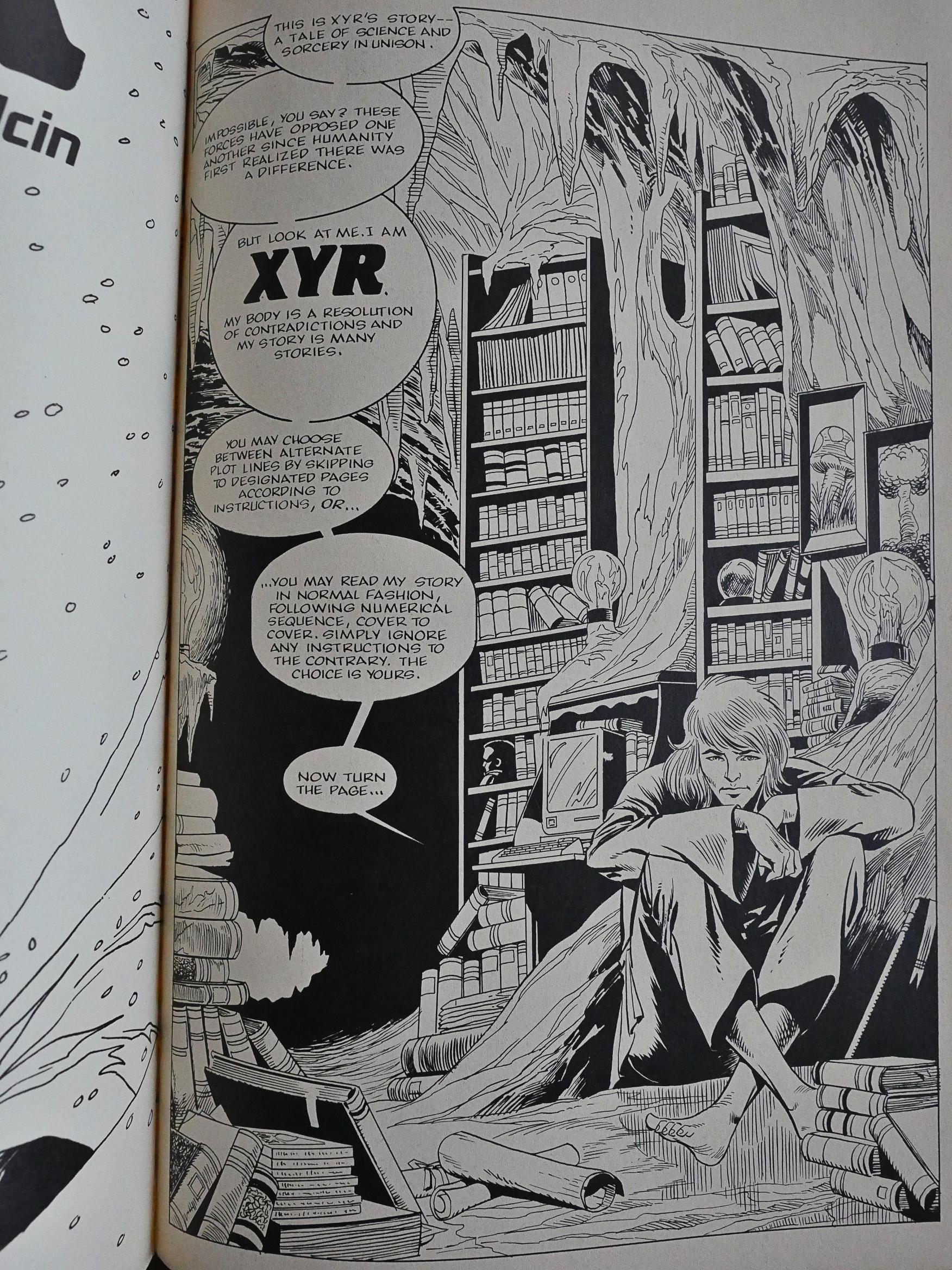

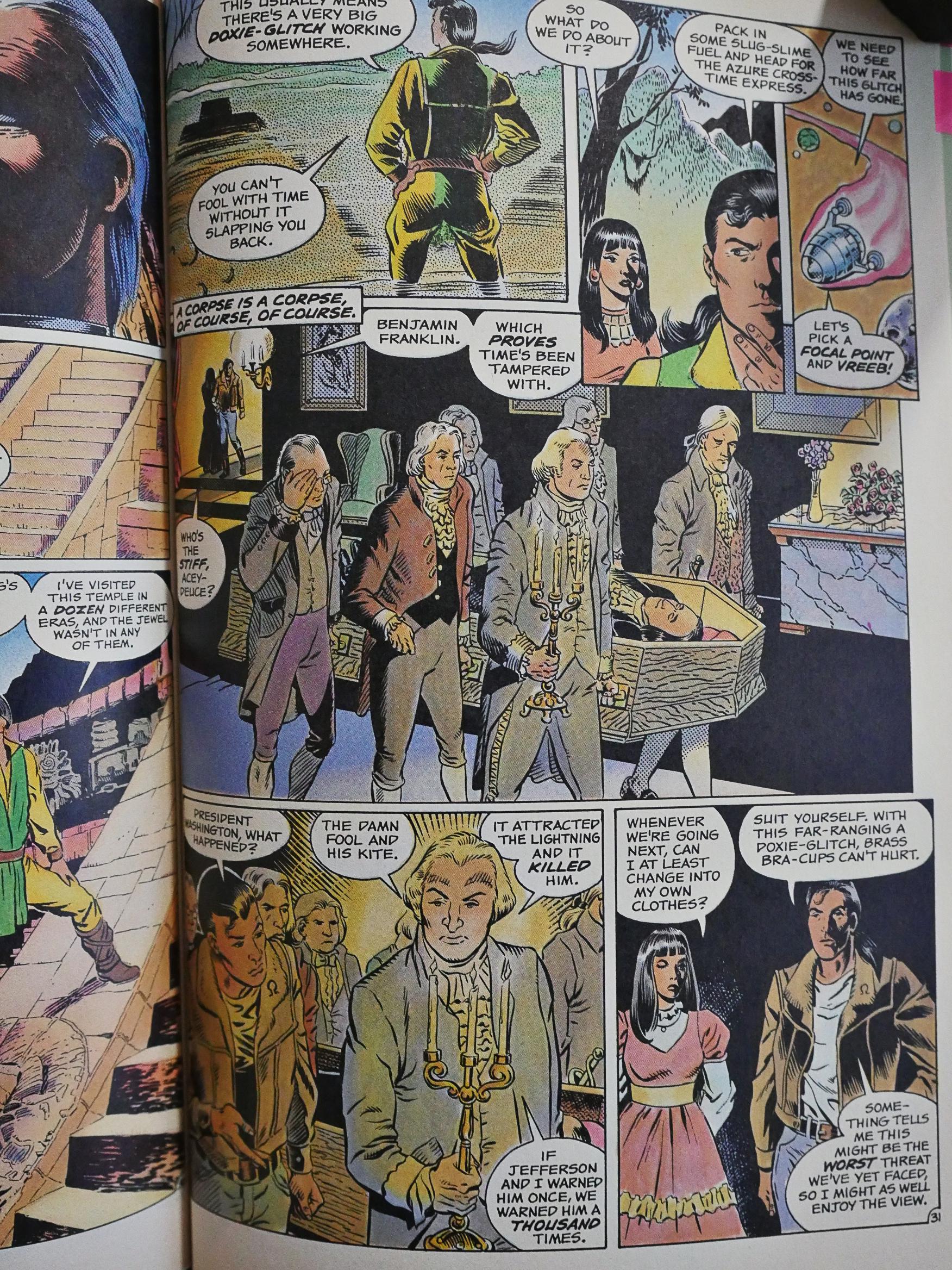

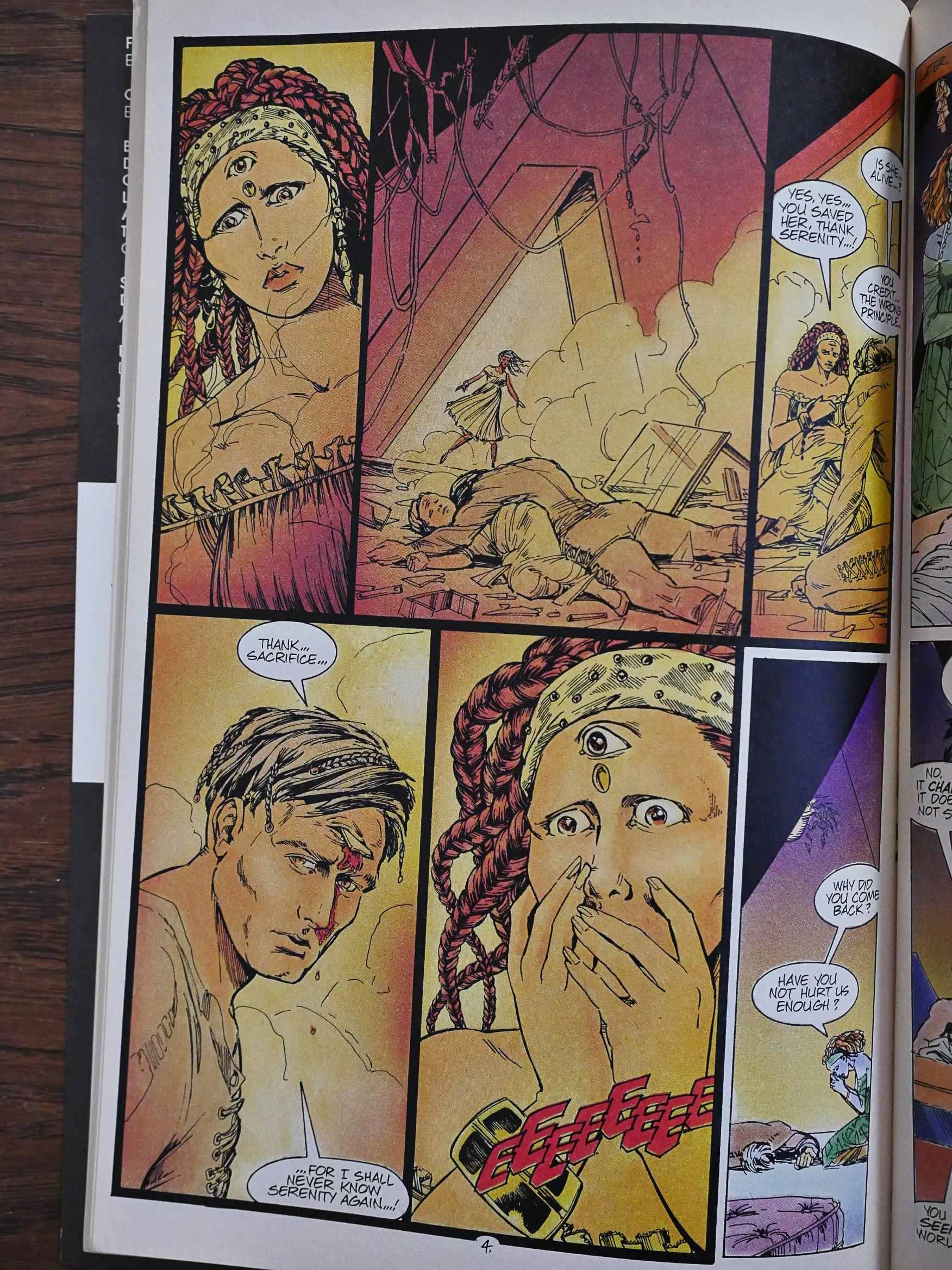

What surprised me, though, was what he concentrated on as the vehicle for it all: This all basically takes place within Doug Moench’s Aztec Ace world. At the start, when Wolfman introduced the Aztec Ace thing, he even emulated Moench’s storytelling tics: The page above wouldn’t be out of place in an Aztec Ace issue.

As things progresses and all the heroes and villains thrash around in the Ace-ness, Wolfman cuts back on that stuff a lot.

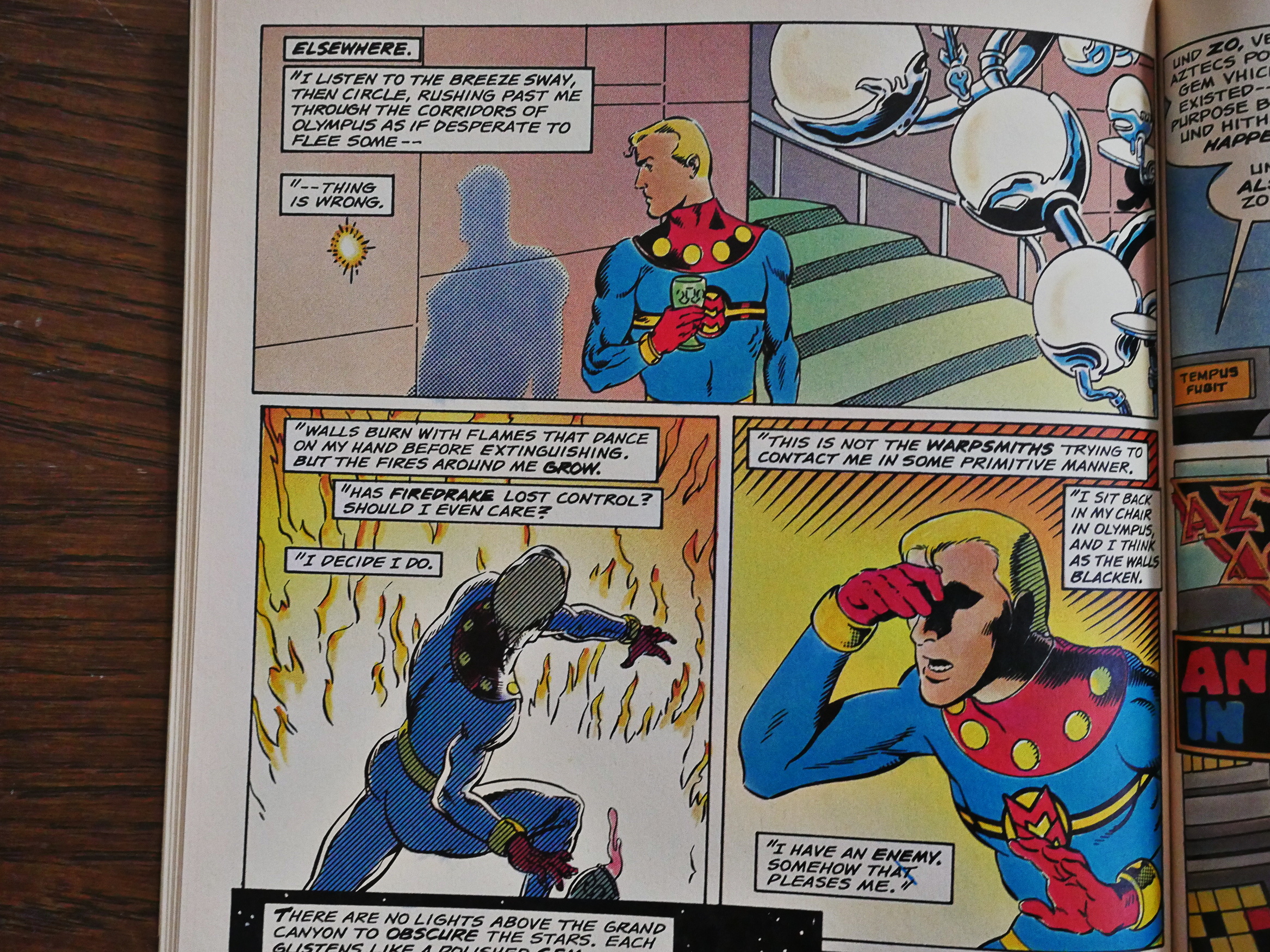

Wolfman also tries his hand at being Alan Moore whenever Miracleman is on the page, with, er, not very convincing results.

The references he makes to the rather harrowing proceedings at the end of Moore and Totleben’s tenure on Miracleman feel trivialising and in bad taste. DC is doing the same with Moore’s Watchmen these days, so I guess Moore is just doomed to have his creations fucked over by lesser talents.

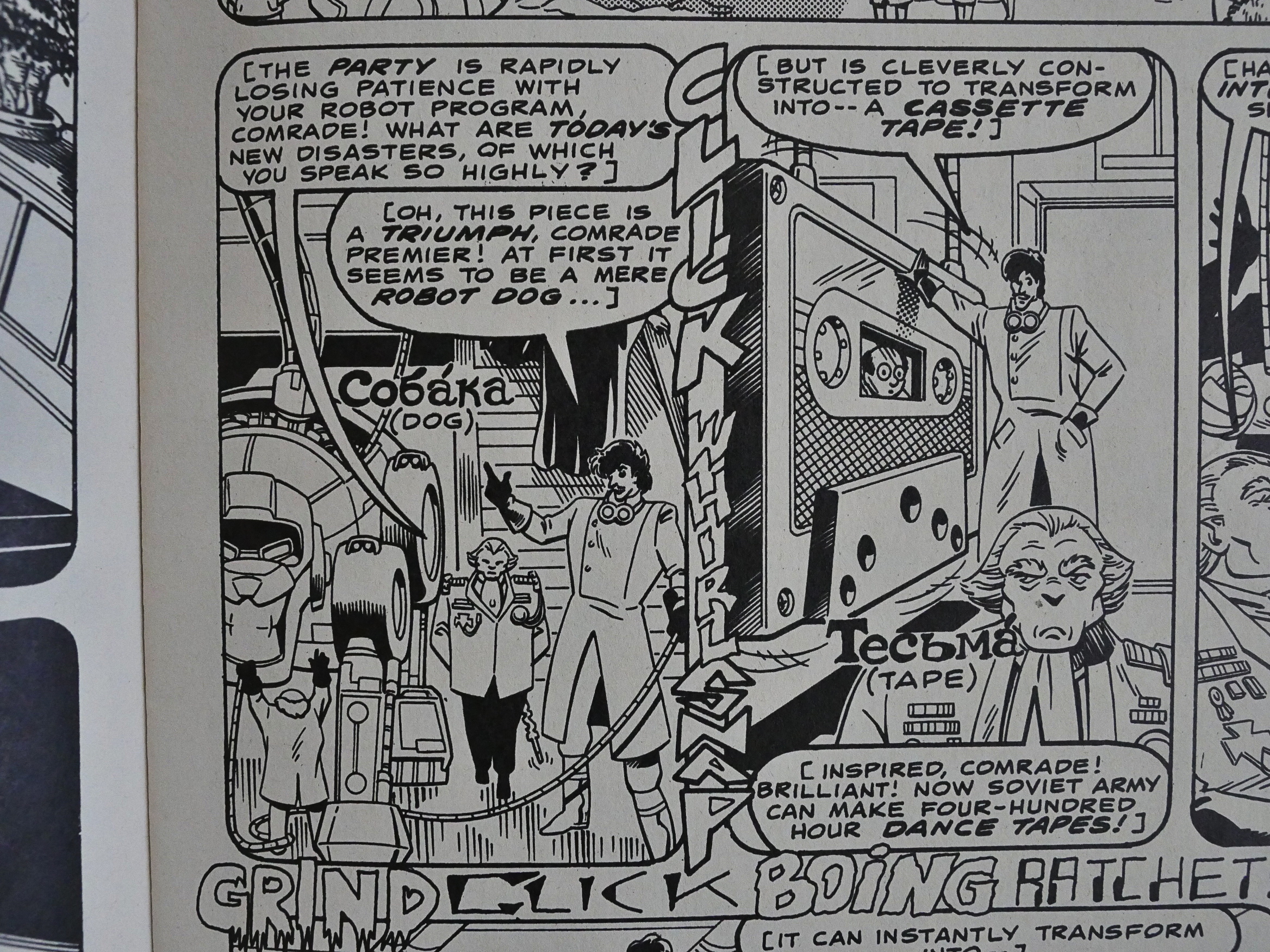

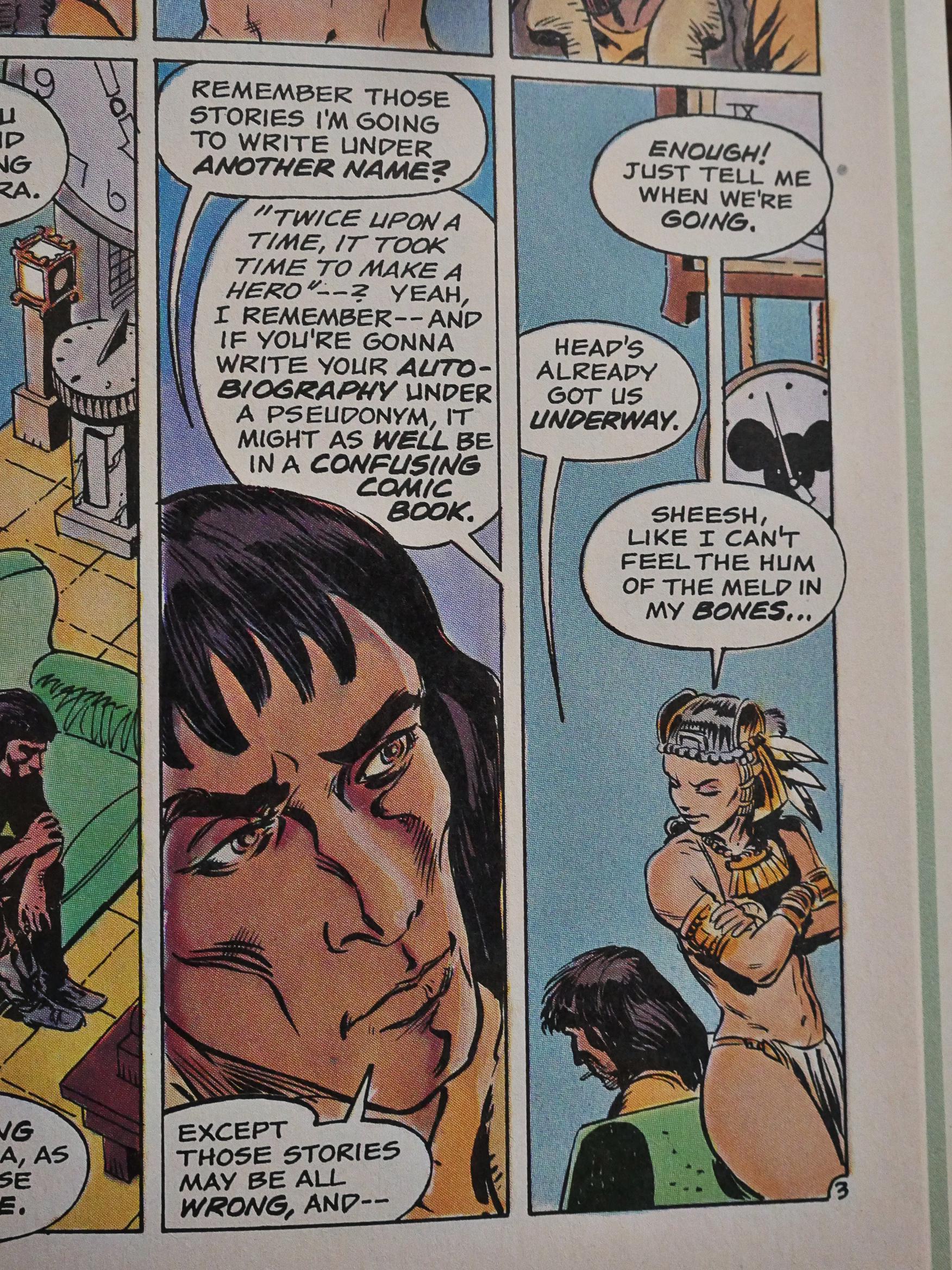

Tee hee. A confusing comic book.

Mullaney’s history lesson about Eclipse is quite detailed at the start, and then grows progressively less so. But that’s understandable. It’s how those first comics got to be published that’s interesting, and then it gets to be routine.

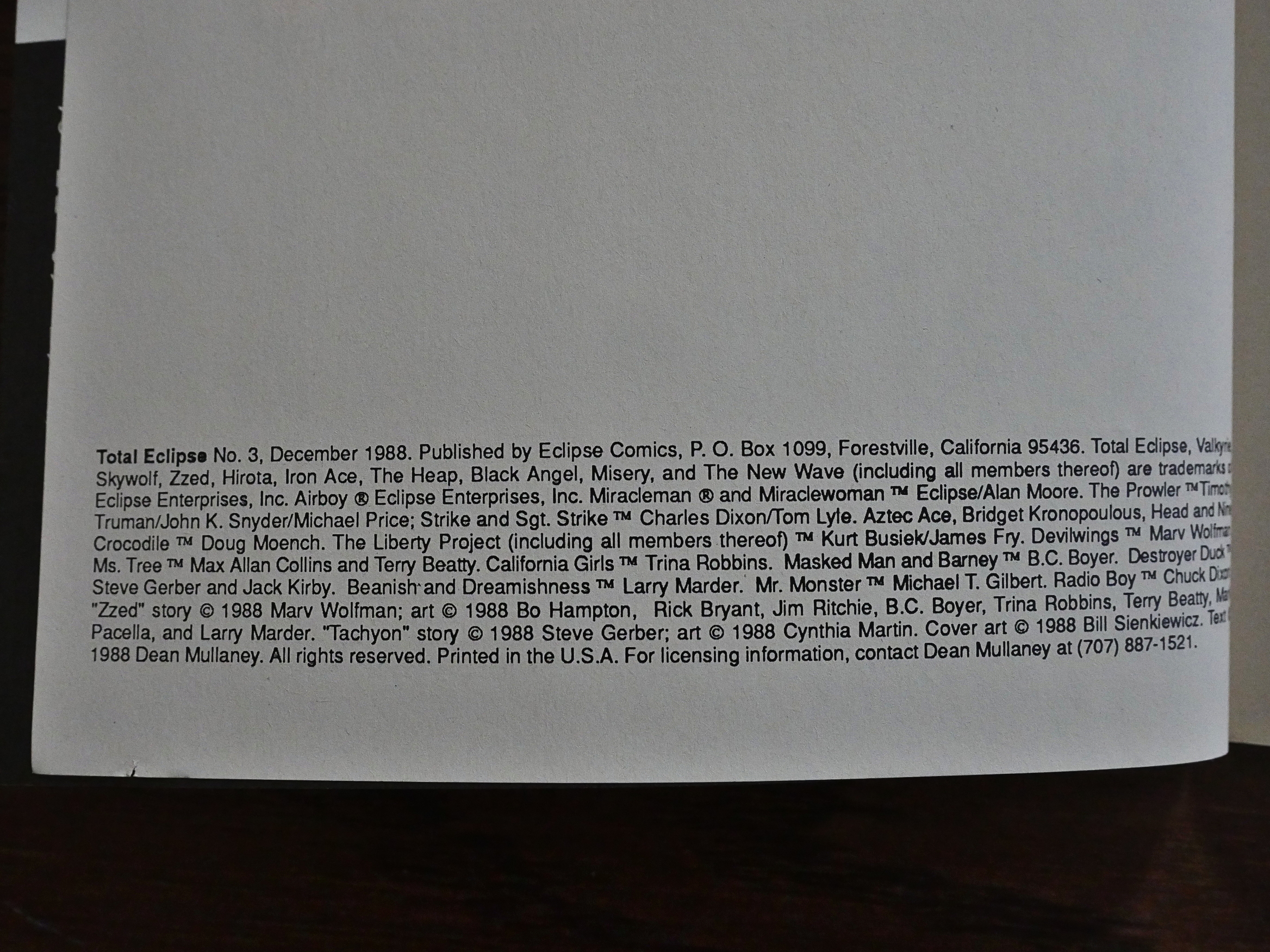

Since this is a crossover between many creator-owned comics and characters, the indicia grows comically long.

Oh, yeah! Beanish from Tales of the Beanworld drops by and turns out to actually do something plot-wise in the book. Not a very interesting thing, because, let’s face it, nothing interesting happens in this book, but still.

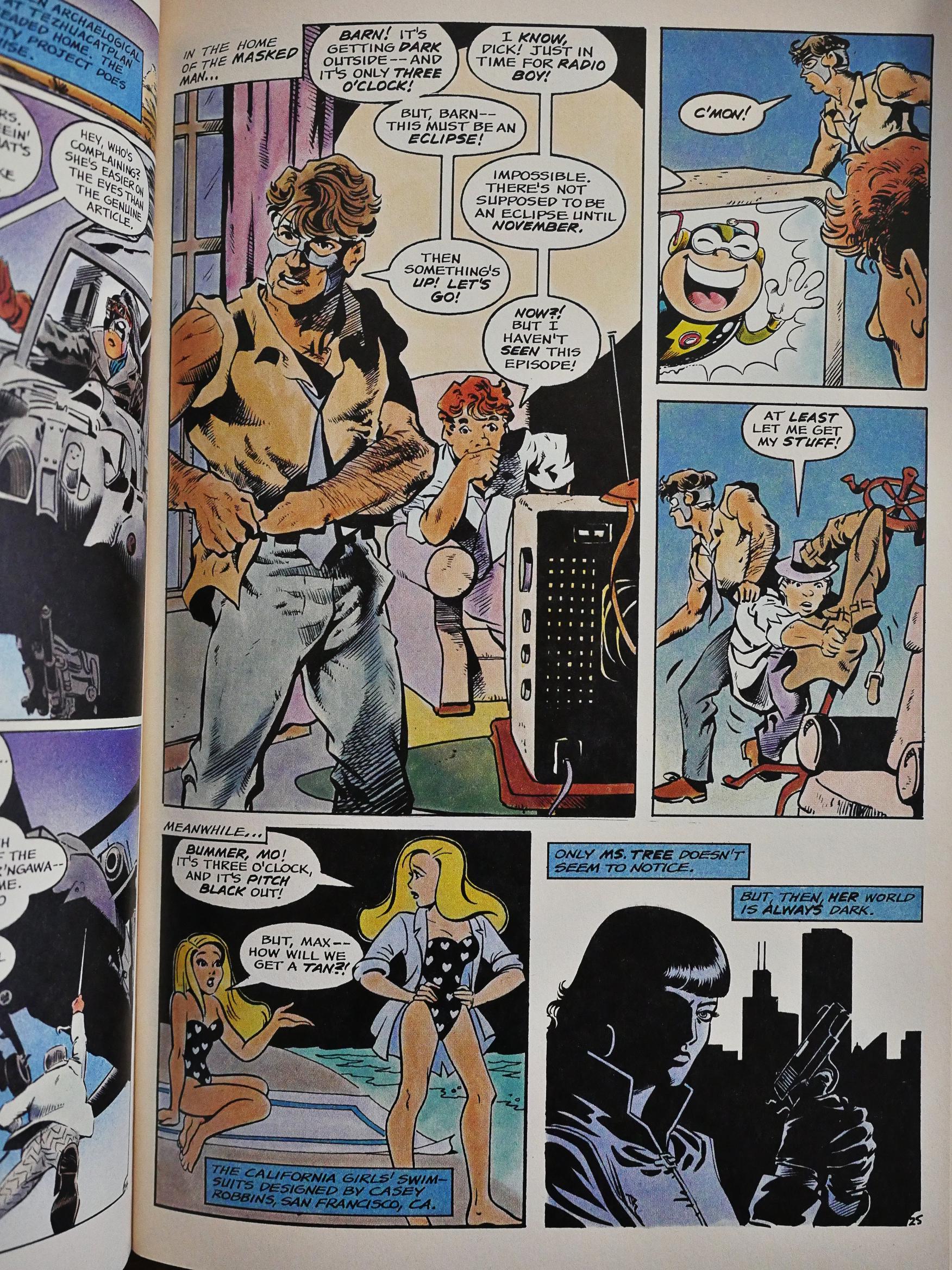

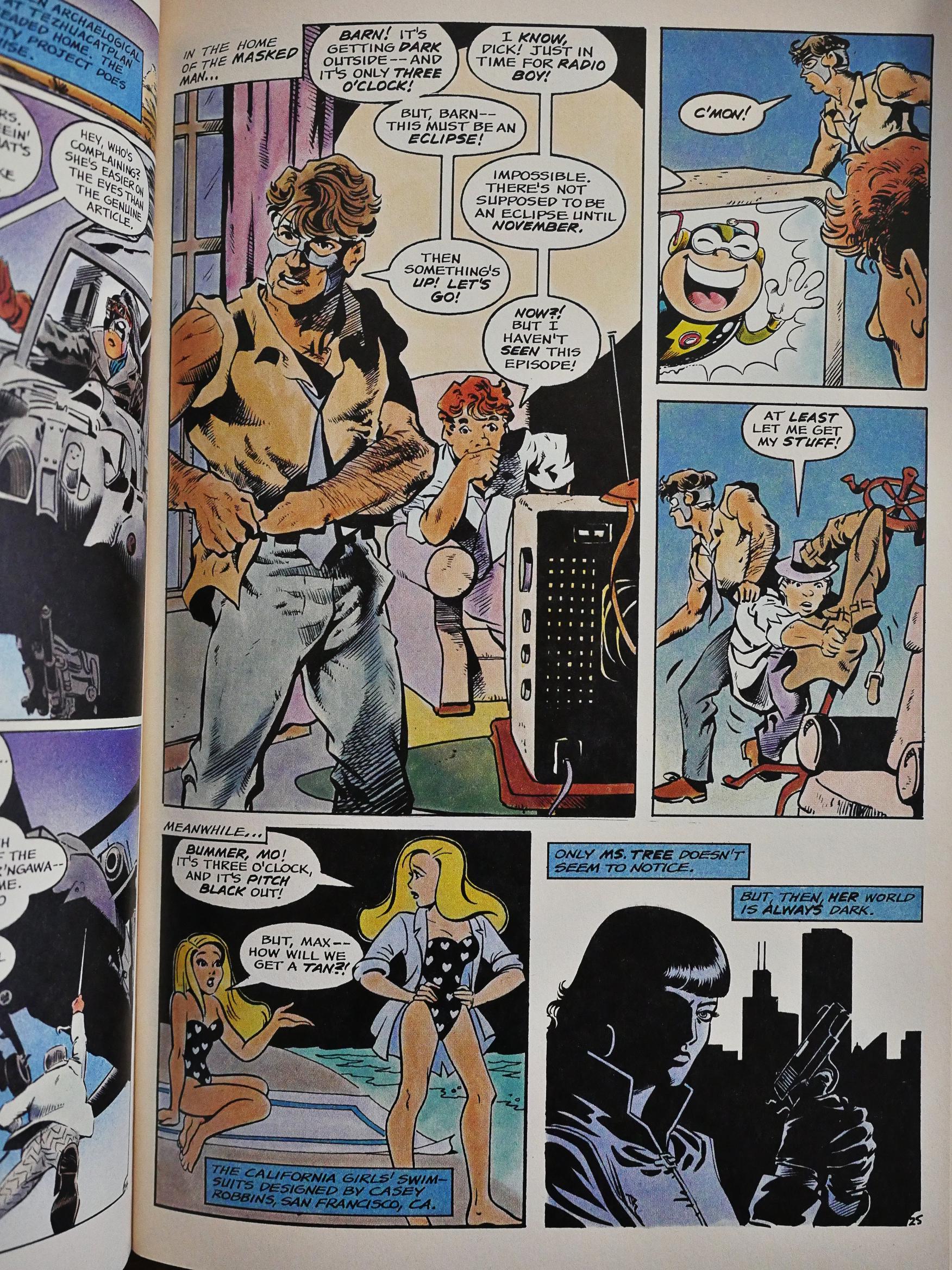

Characters that drop by without any impact whatsoever includes Trina Robbins’ California Girls, but I love that even here, we get to know who designed those outfits. And the page reminds me a bit of certain Crisis crossovers that consisted of nothing but the hero looking up at the sky in a panel in the book thinking “Hm… something’s going on…”

Perhaps this is Wolfman making a sly wink at that debacle. Or perhaps they’re just having fun.

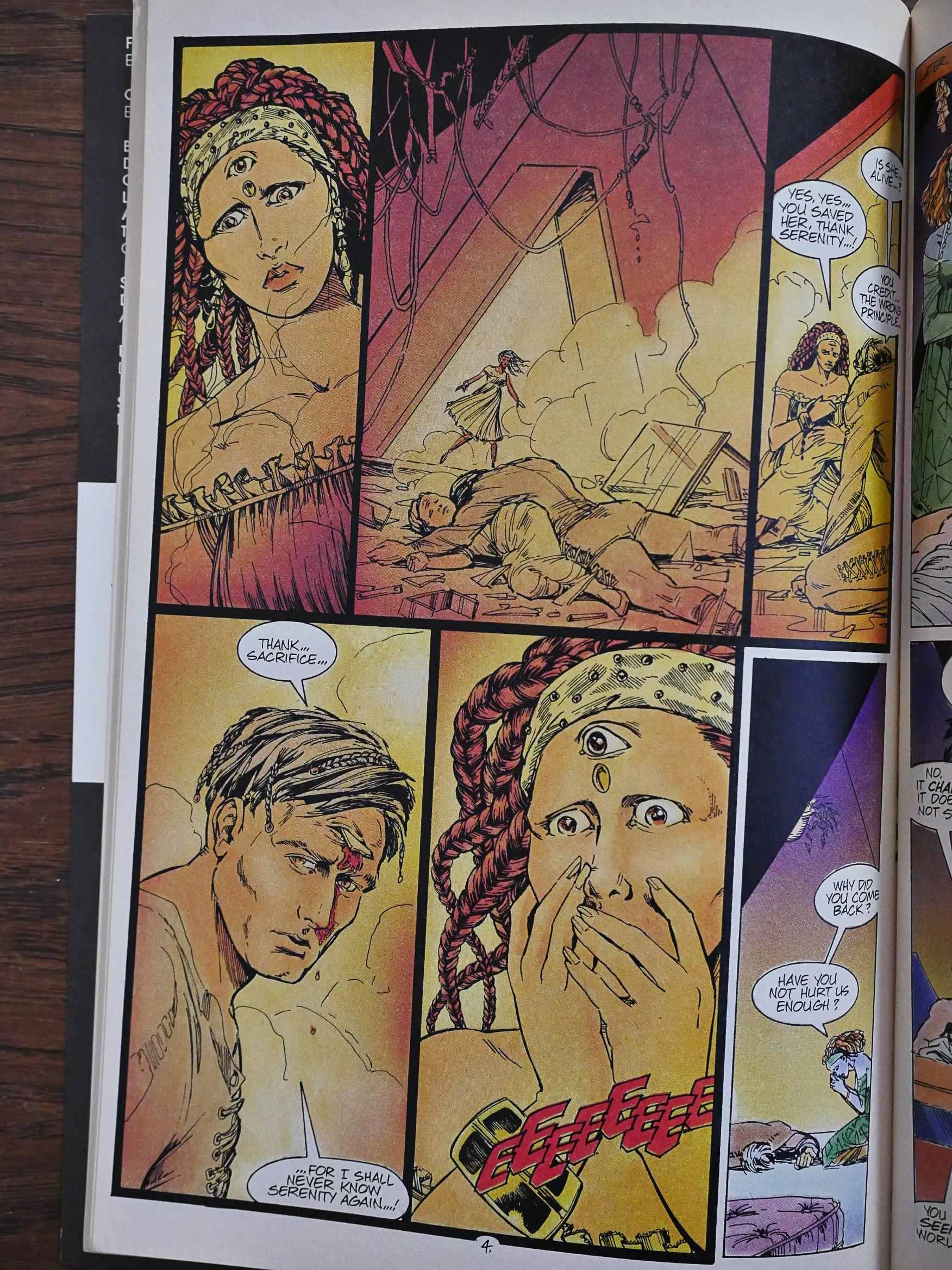

Steve Gerber drops by to write a backup feature about, er… Tachyon? Is that what he’s called? He’s with the New Wave. The artwork by Cynthia Martin is quite stylish with all those thin thin lines.

And Eclipse had plans to spin this off into its own series, and that never happened, because Eclipse stopped doing new super-hero series. Which they had to know that they were going to do by this point, but perhaps this had been completed a year earlier when Eclipse were still in that business.

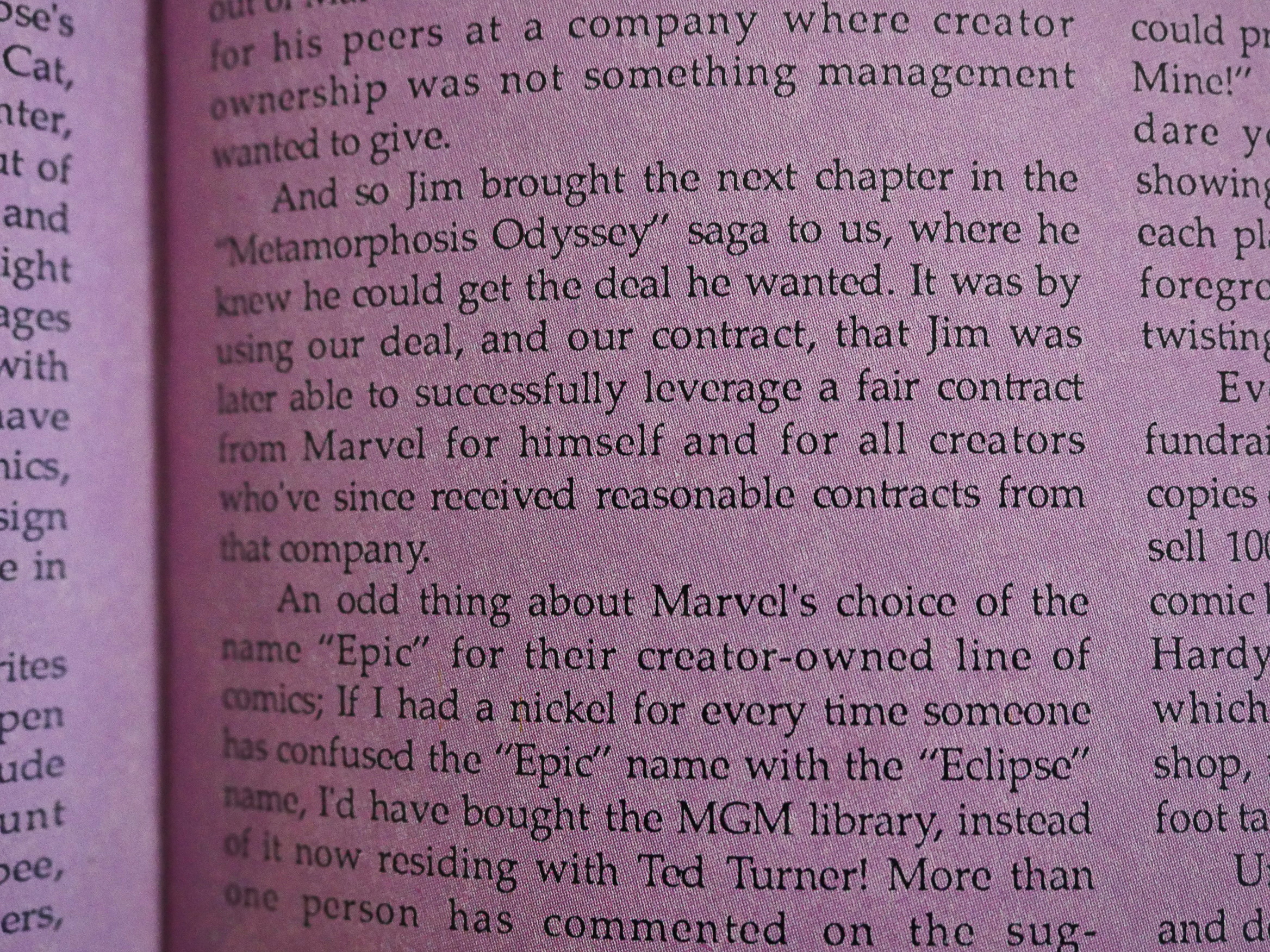

I had surmised that the artists tied to Marvel were using Eclipse as a bargaining chip, and Mullaney confirms it. And they all returned to Marvel after Marvel caved, so it was a success for the creators. Less for Eclipse, who had to find other people and projects to publish.

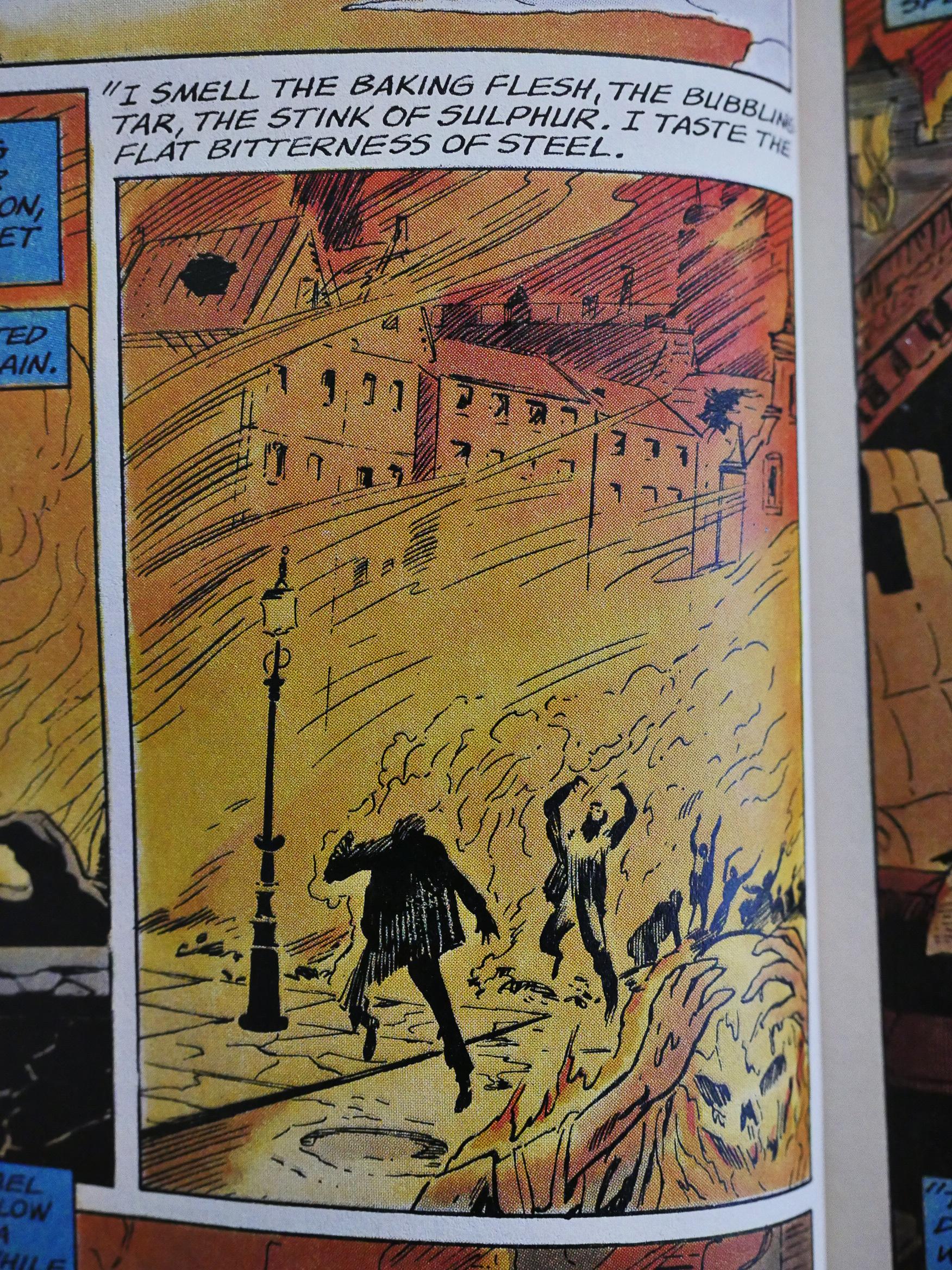

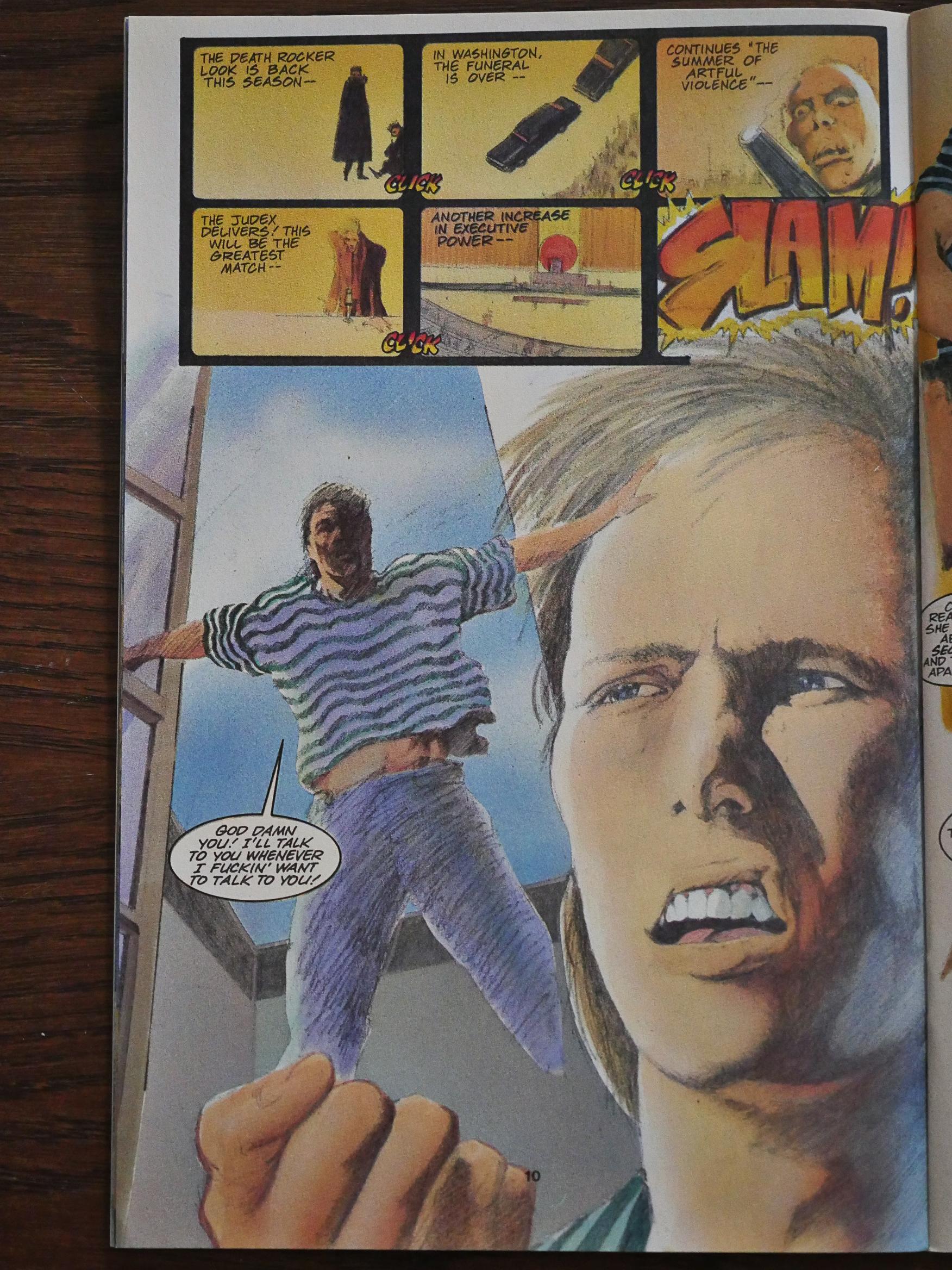

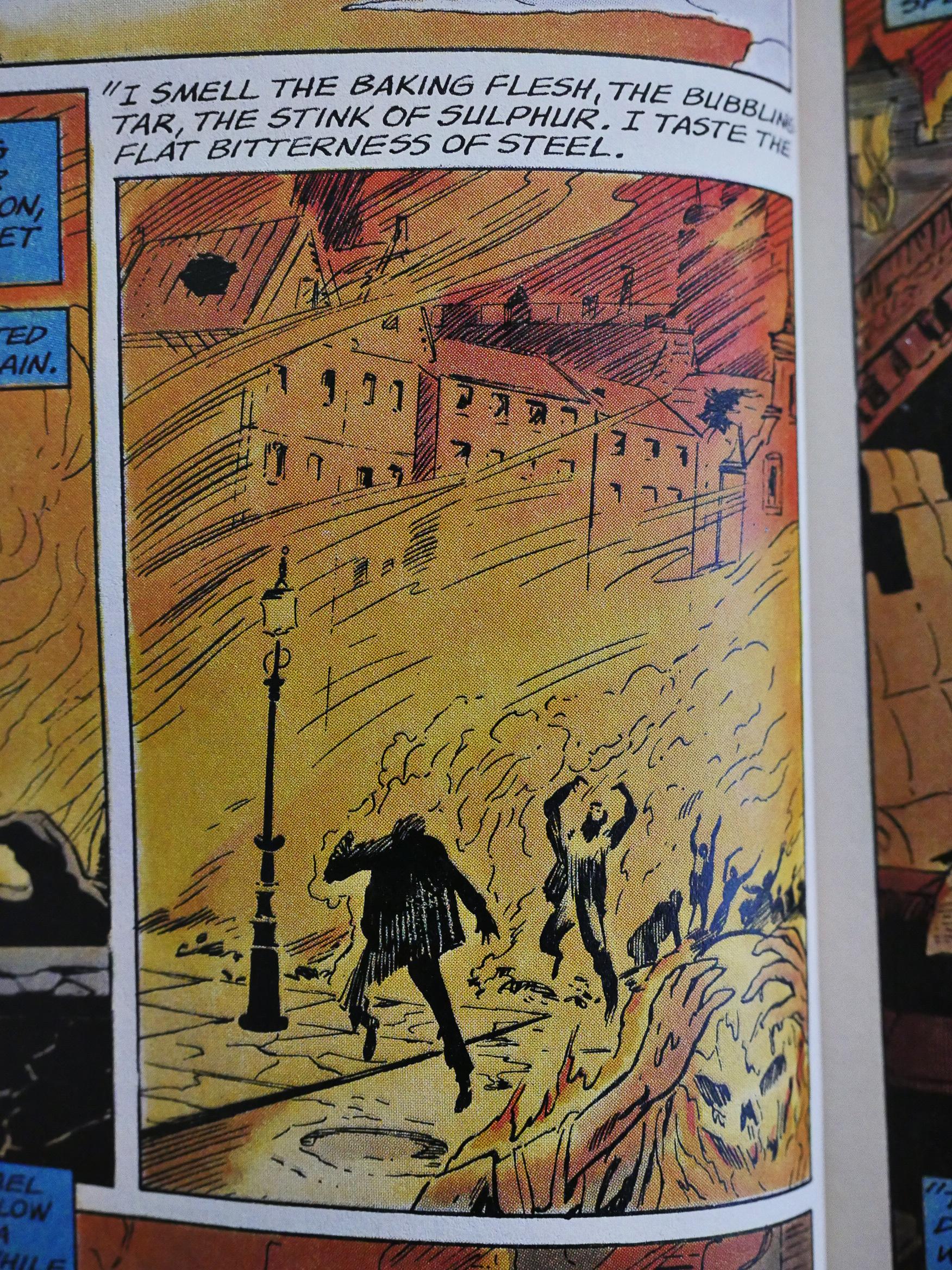

One backup feature stands out like a twelve inch nail protruding from somebody’s eye socket: Neil Gaiman and Mark Buckingham’s Miracleman strip. It’s a prologue of sorts to their run on Miracleman, and it’s brutal. The tone of Total Eclipse is rather lighthearted within all the standard super-hero mayhem, and this is something completely different.

And excellent, although it’s probably gorier than it had to be.

Mullaney tells the tale of when Marvel flooded the direct sales market with titles, forcing many smaller companies into bankruptcy. One of them was Pacific Comics, from whence Eclipse bought the unpublished titles. What I found interesting here was that Mullaney got the colour negatives for all the comics in the pipeline, which I hadn’t seen stated explicitly anywhere before. But that explains how Eclipse were able to publish so many new titles over a few months.

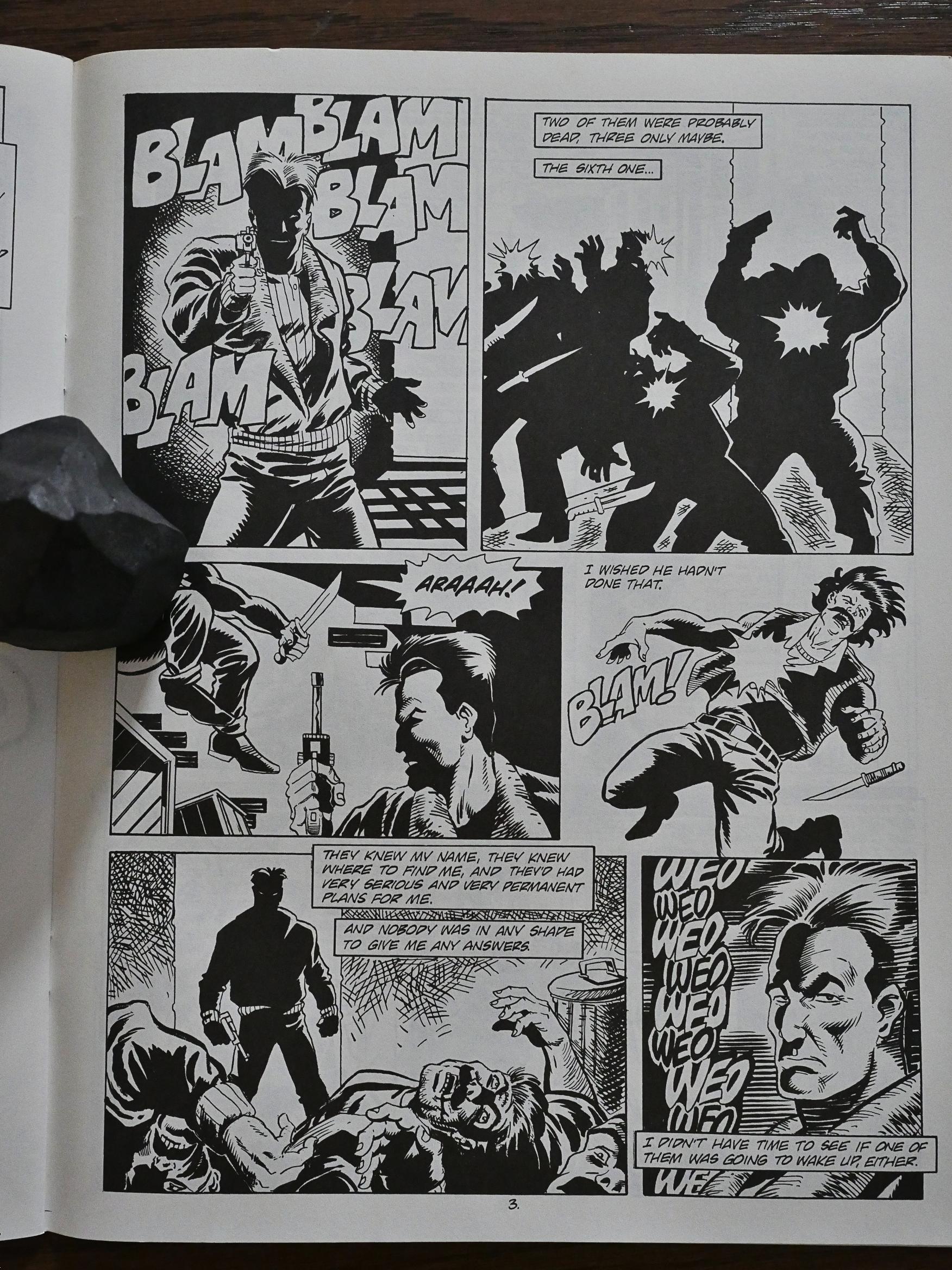

Uhm… Should I write more about the plot? No? Trust me, you don’t want to know. But if you like pages and pages and pages of fighting like this, you can do worse, I guess.

I don’t really, so I found the thing rather dull.

But I liked having Beanish in here.

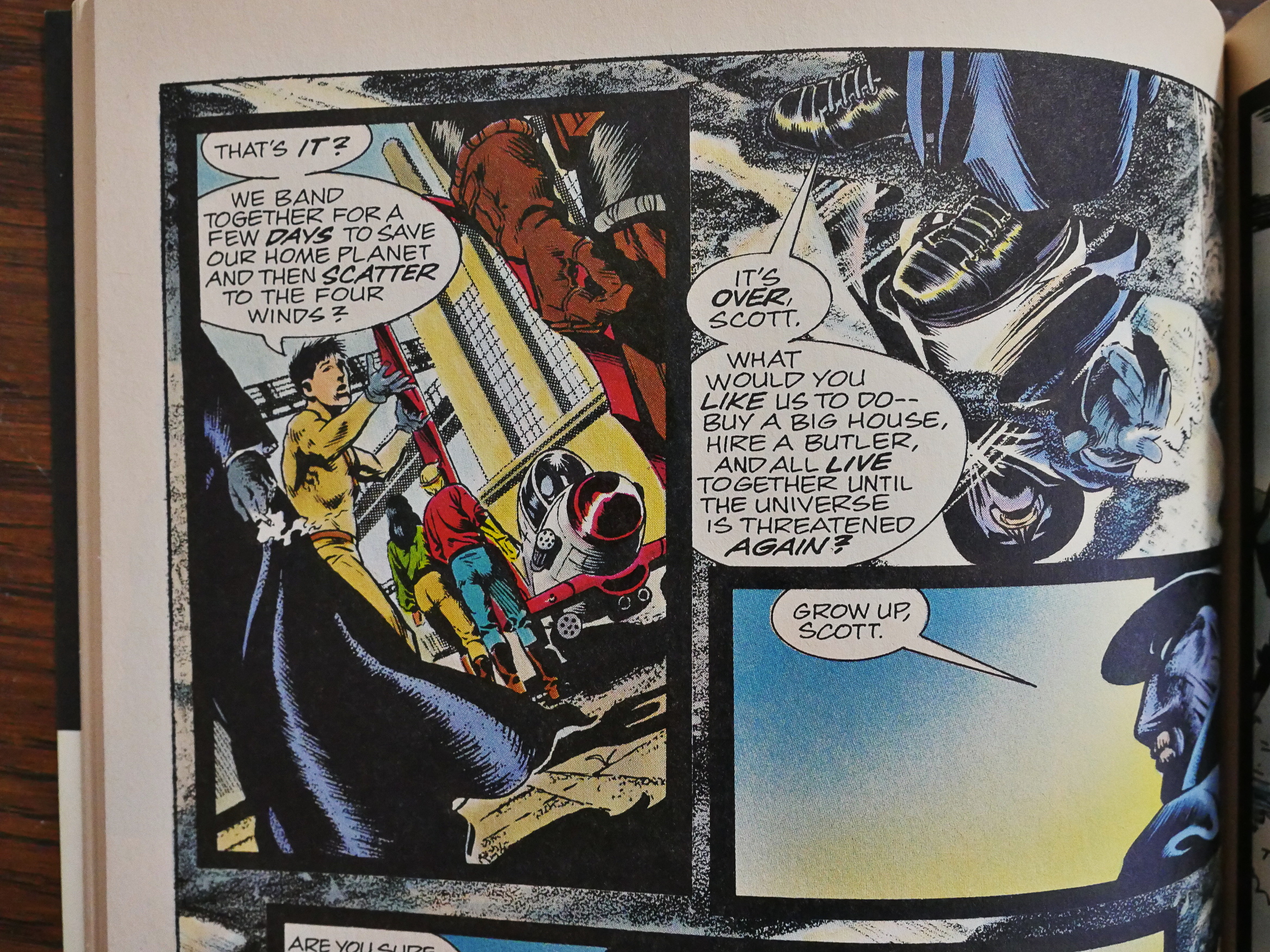

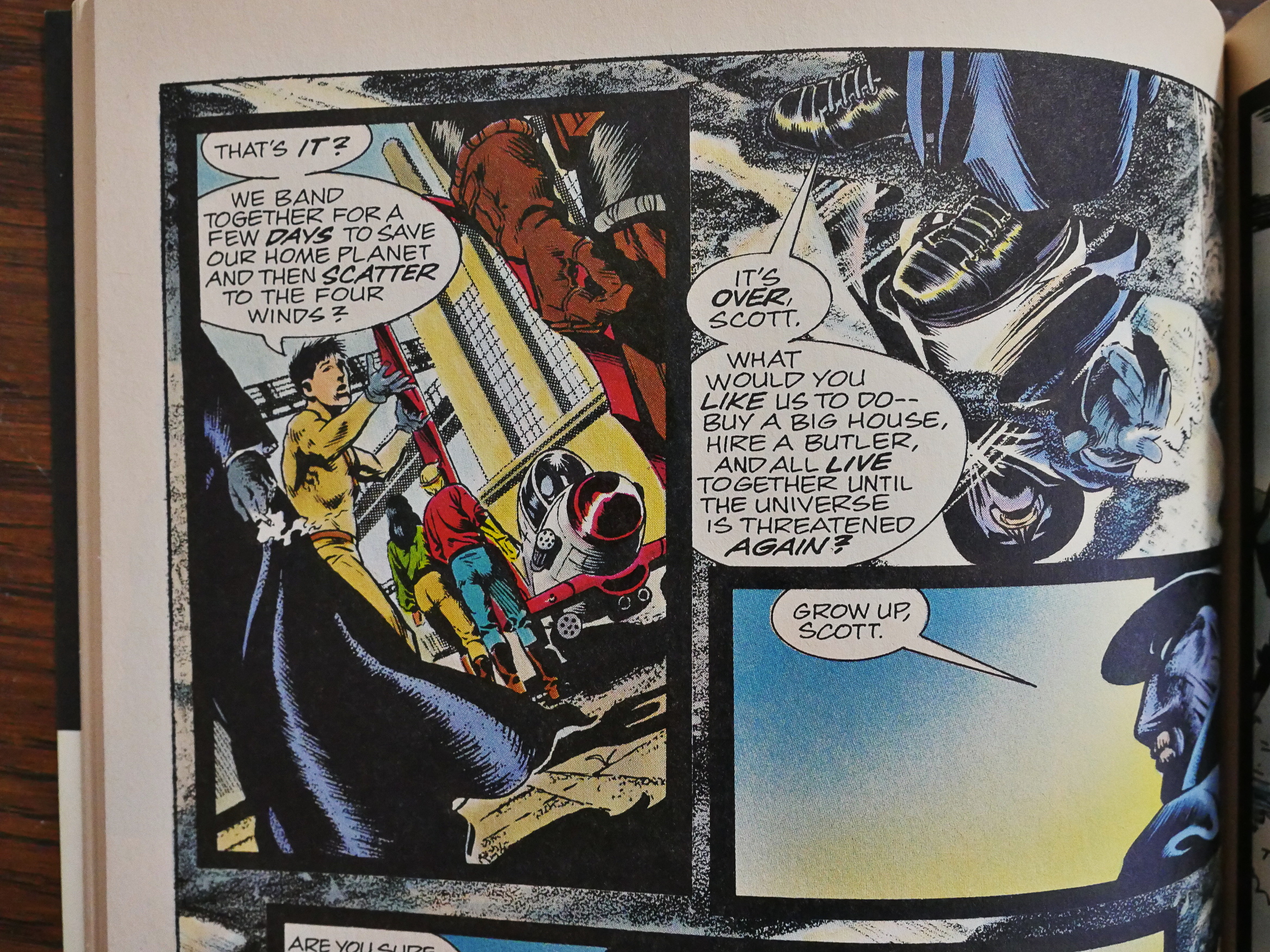

The ending is quite nice. Basically, everything returns to the status quo, except that they kill off one character. (Who nobody liked in the first place.) But it ends on a pretty up tone, fitting the rest of the book.

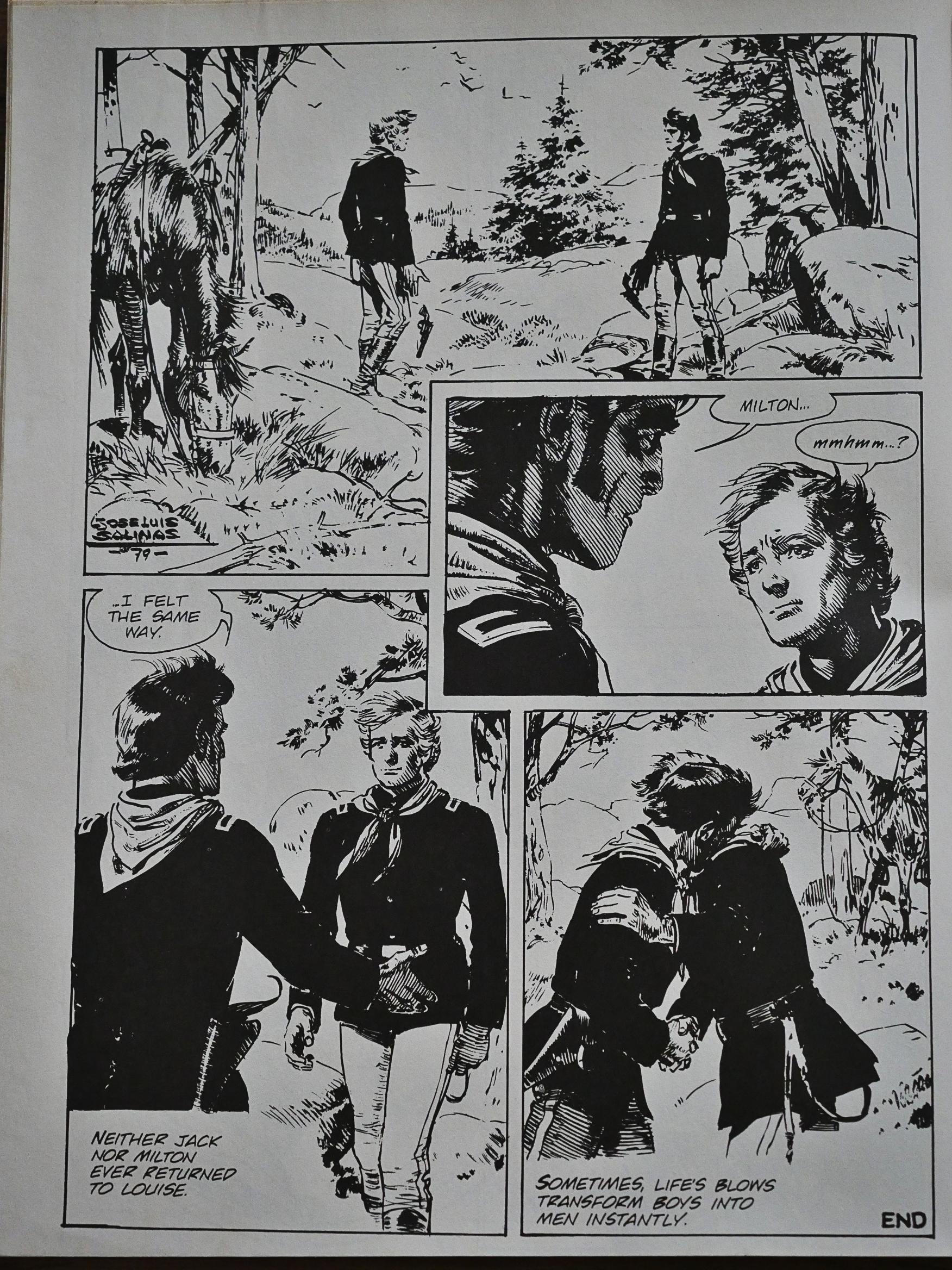

And then we get the final backup story, written by Chuck Dixon and with excellent artwork by Stan Woch, and it’s a bit of a downer. It’s a strange editorial choice.

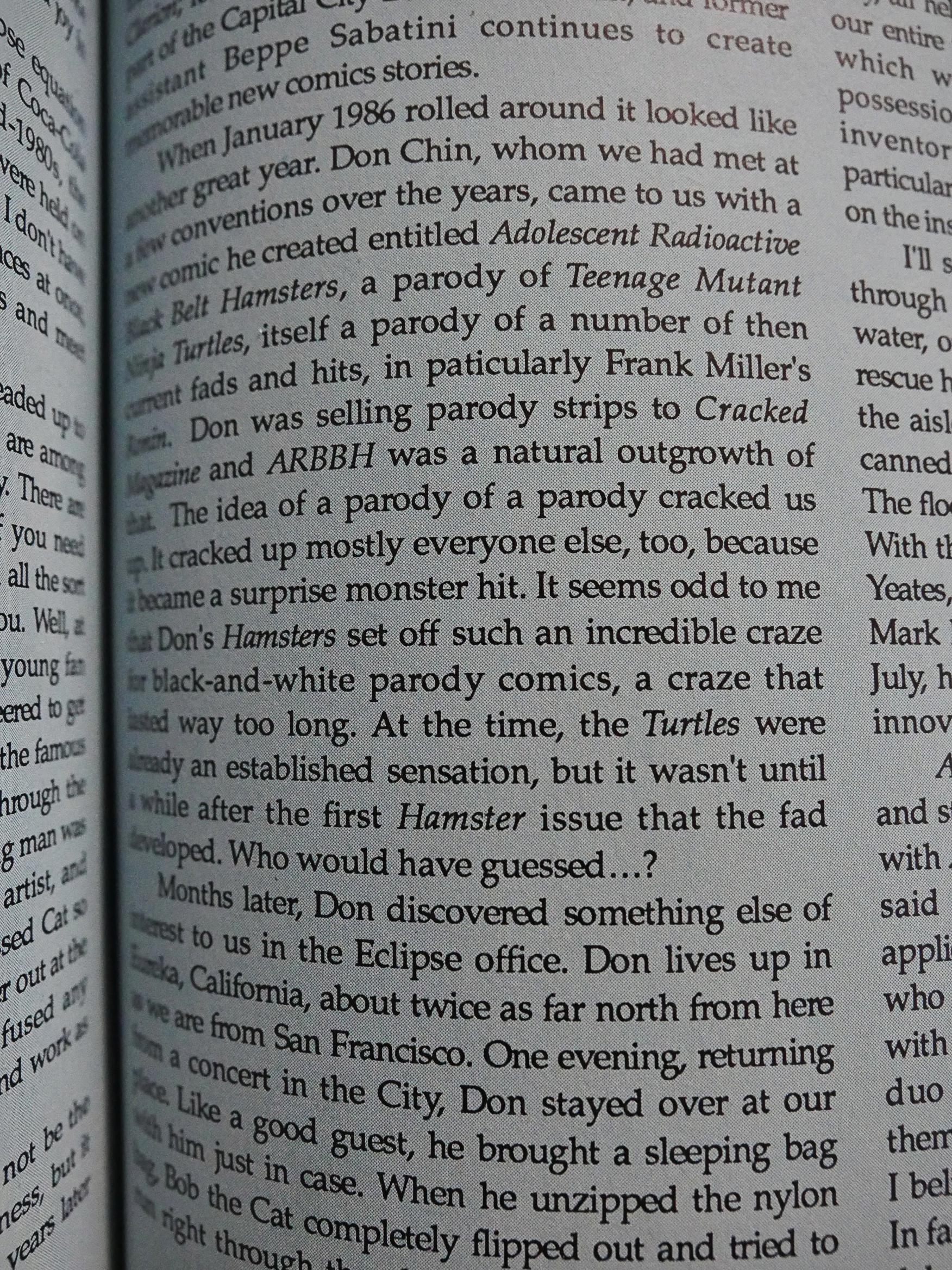

In the final issue’s story of Eclipse Comics, Mullaney pretty much own up to having started the black and white boom, but doesn’t mention that it also almost broke the American indie comics business, although “a craze that lasted way too long” might be read as a semi mea culpa, I guess.

So there you have it: Eclipse bet hard on this series, with nice covers by Bill Sienkiewicz and all (I especially like the one with the Beanworld character all over it), but it was a bet that didn’t pay off, apparently.

I tried googling a bit to see what other people thought of it:

So, the basic thing of it is that the villain became a hero, and neither of the remaining villains was brought to justice or even captured. Add to that the madness of it all (Eclipse’s publishing at this point consisted of a couple dozen different realities, including the revived characters from Hillman Publications.) and the fact that Eclipse’s publications didn’t last much longer after this crossover, and you’ve a recipe for 80’s comic boom madness. I pride myself on having collections of Miracleman, The Liberty Project, Aztec Ace and several others (and I’m working on a run of Destroyer Duck, which are harder to come by than hen’s teeth these days) and even *I* don’t have a clear understanding of what this is all about.

Hm… Oh, here’s Wolfman talking about it:

When I took on Total Eclipse, which was Eclipse’s attempt at shoving their universe together, I did it as a favor. I didn’t know or care about the Eclipse universe (aside from selected books which I really did like) and I didn’t have a specific story to tell as I had with Crisis. But I was asked by people I couldn’t say no to, and I did the job. The book was, as is the cliché, a job of work.

I was asked to take Kurt’s Elcipse series and somehow incorporate it into my larger story. I did my best, but my heart wasn’t in it for any number of reasons. Total Eclipse came out, sold two copies, and vanished. I tried to do as good a job as I could, and for all I know the two people who bought it loved it, but I’m sure I did no justice to Kurt’s or anyone else’s creations.

Well, that explains a lot.