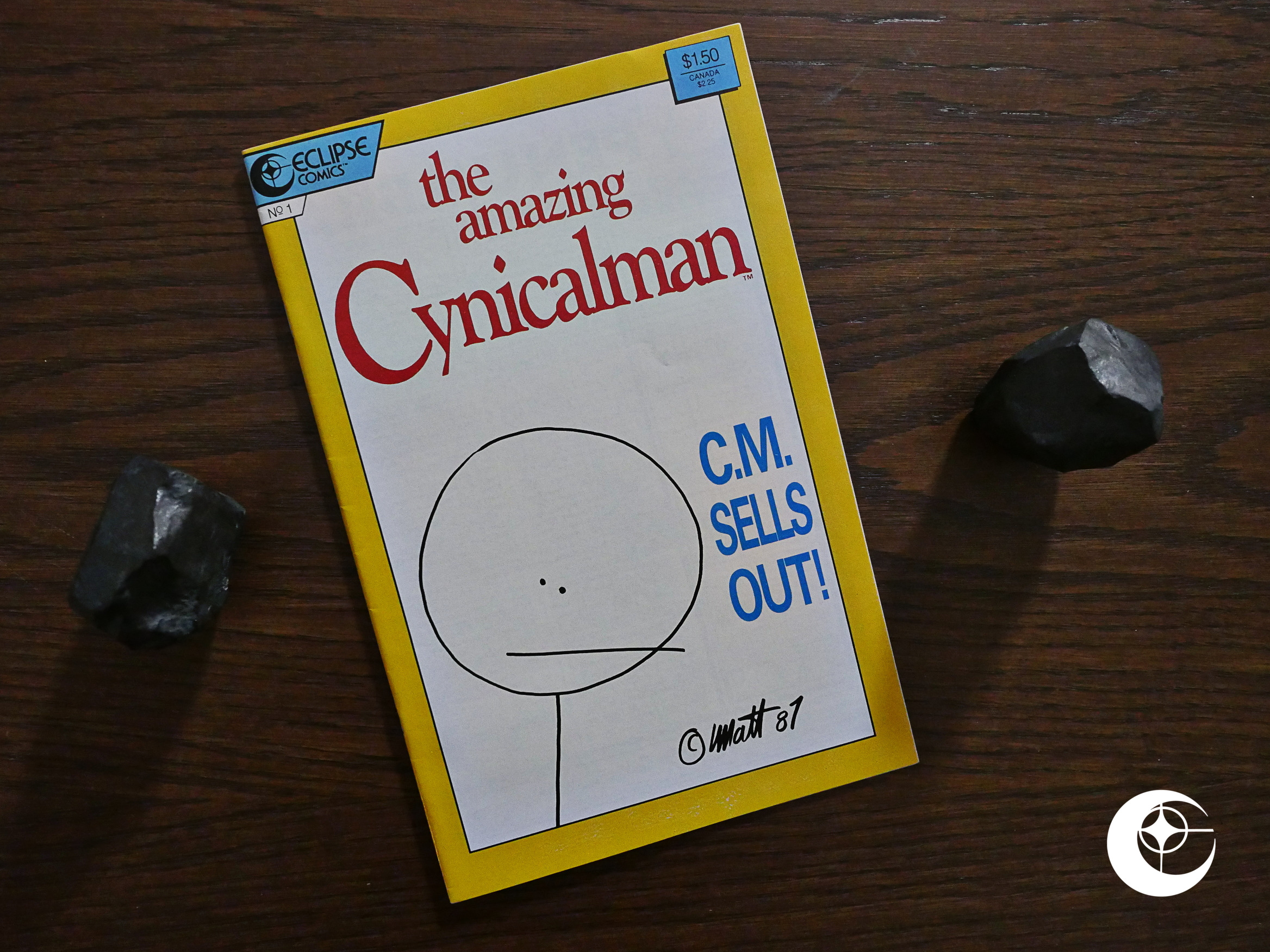

Area 88 (1987) #1-36, Area 88 (1988 Viz) #37-42 by Kaoru Shintani et al.

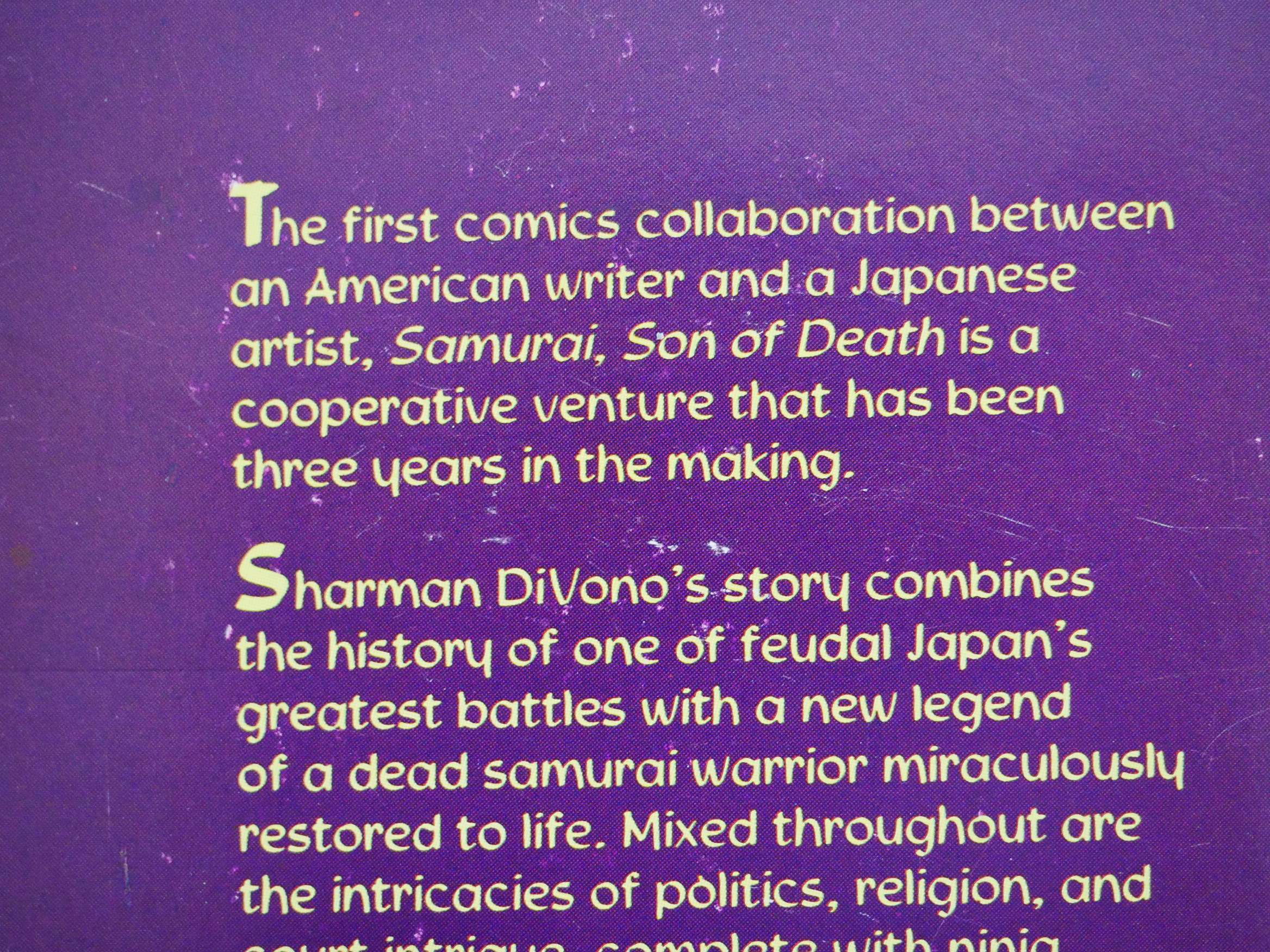

With this comic, a new era starts for Eclipse comics, and probably the most historically significant. If Eclipse is ever mentioned any more, it’s as the company that brought Japanese comics to the US.

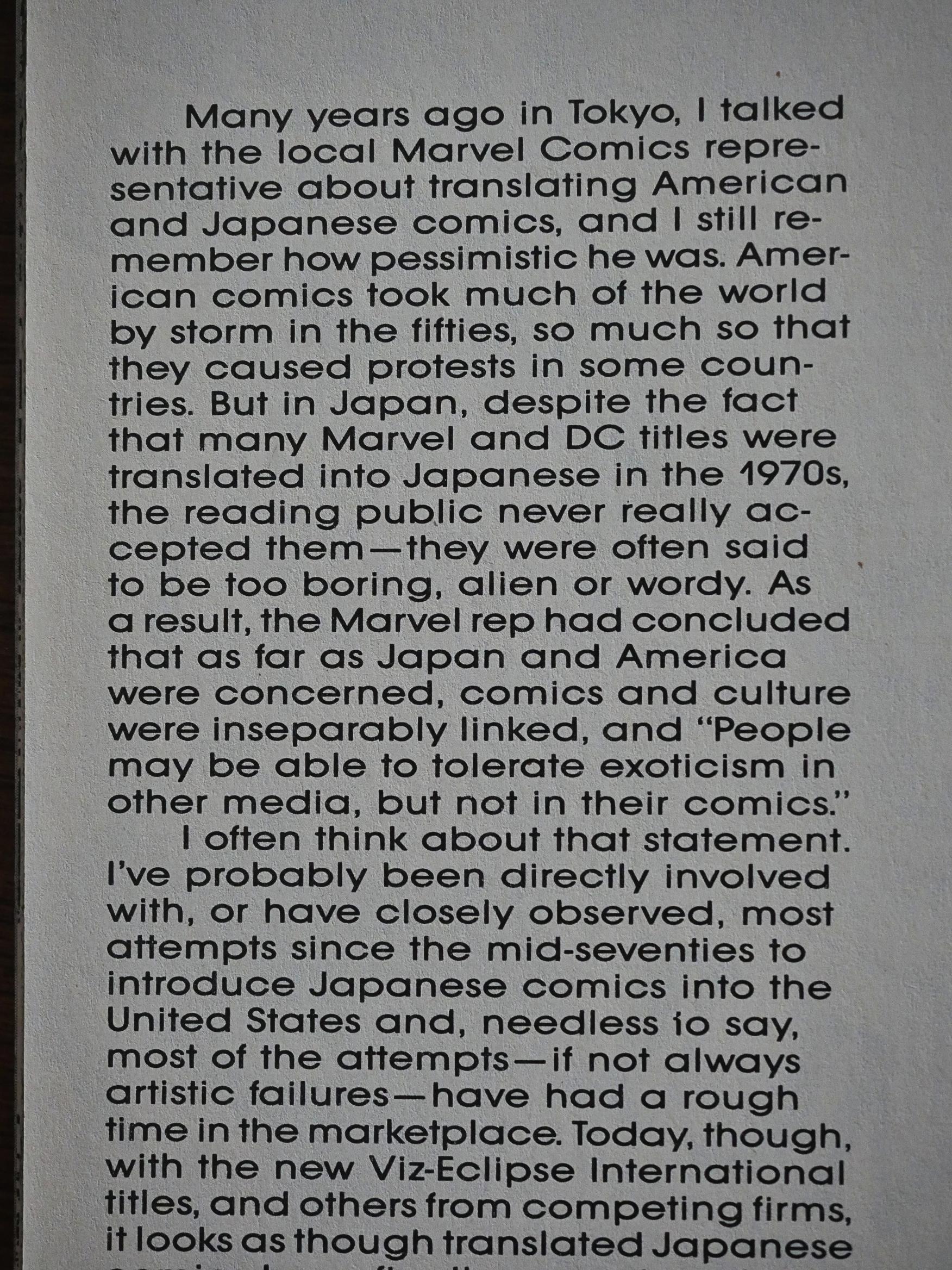

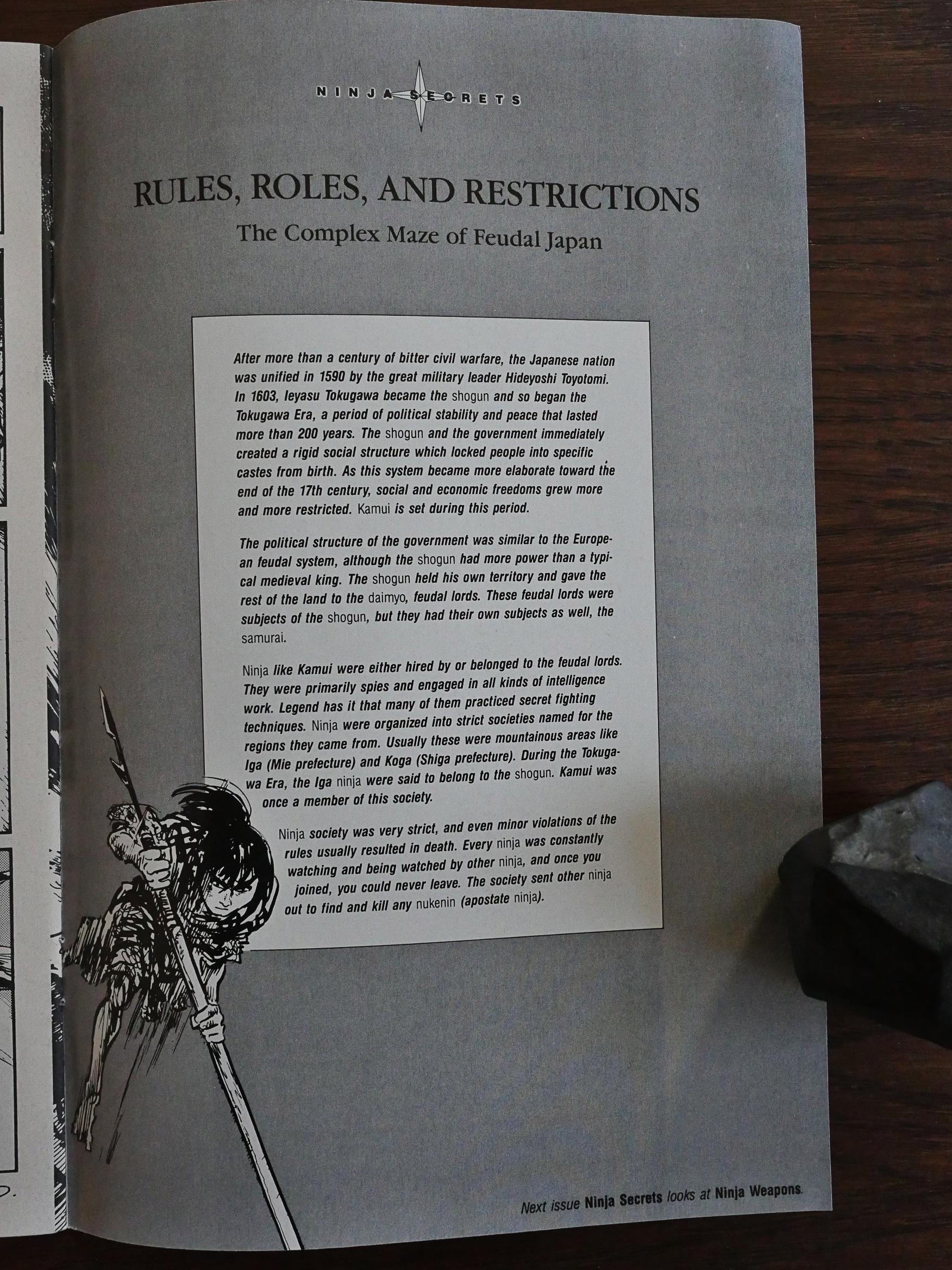

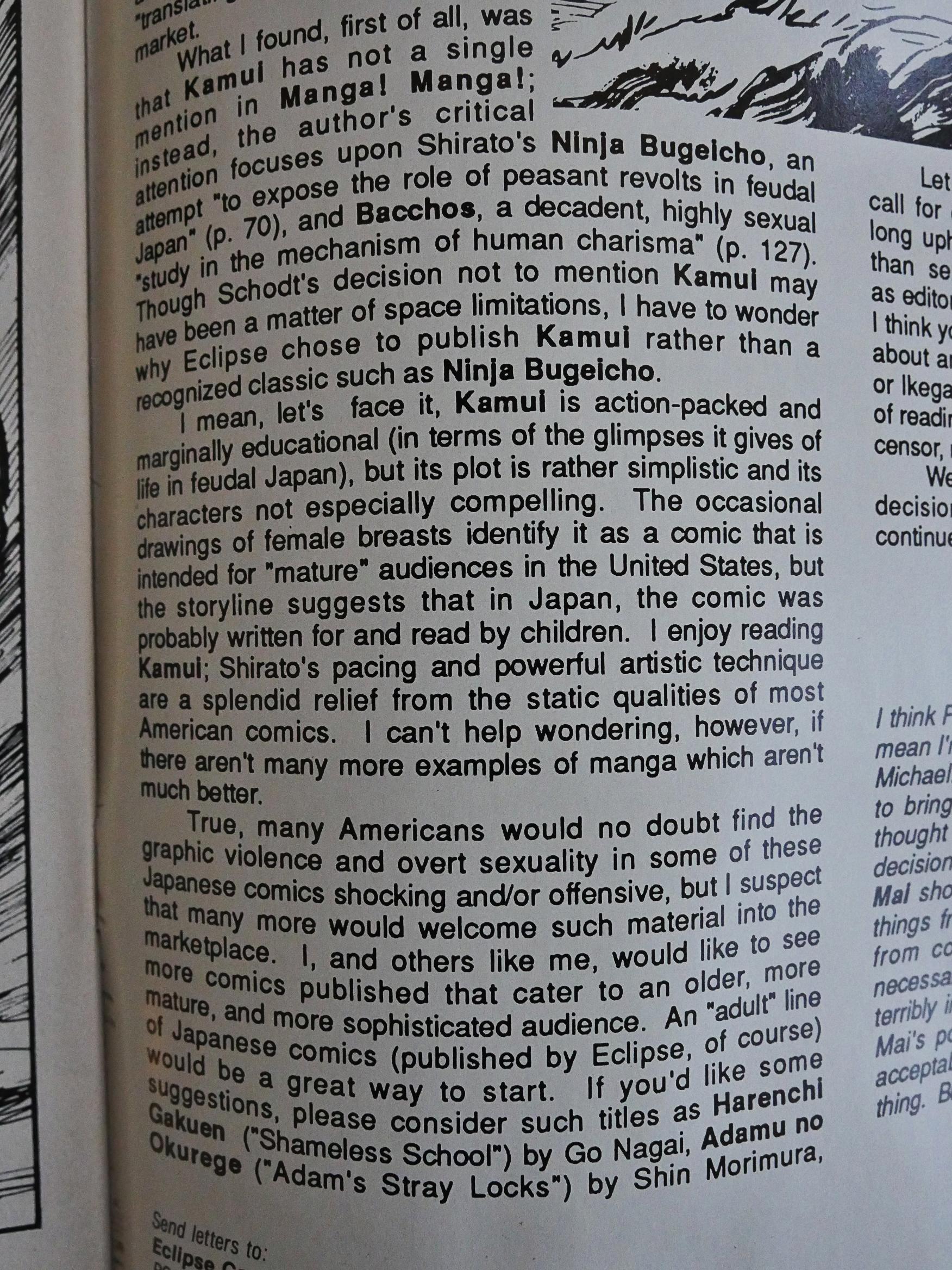

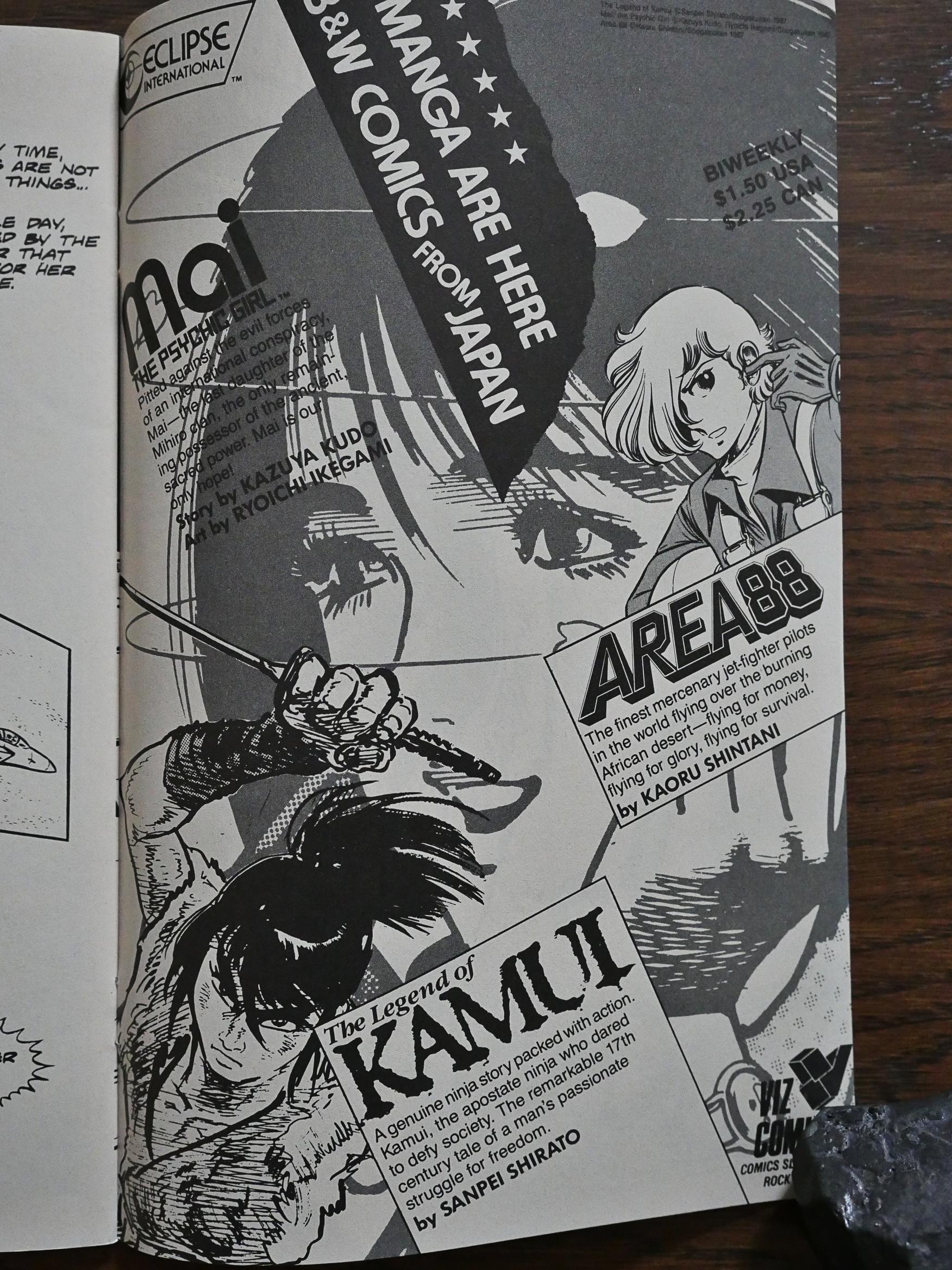

Less than a handful of Japanese titles had been published before this in the US: Barefoot Gen and I Saw It (both about Hiroshima and Nagasaki) had made some waves, and Raw Magazine had published some more Japanese underground comics, but nobody had ever attempted to translate and publish Japanese children’s comics for an American market before.

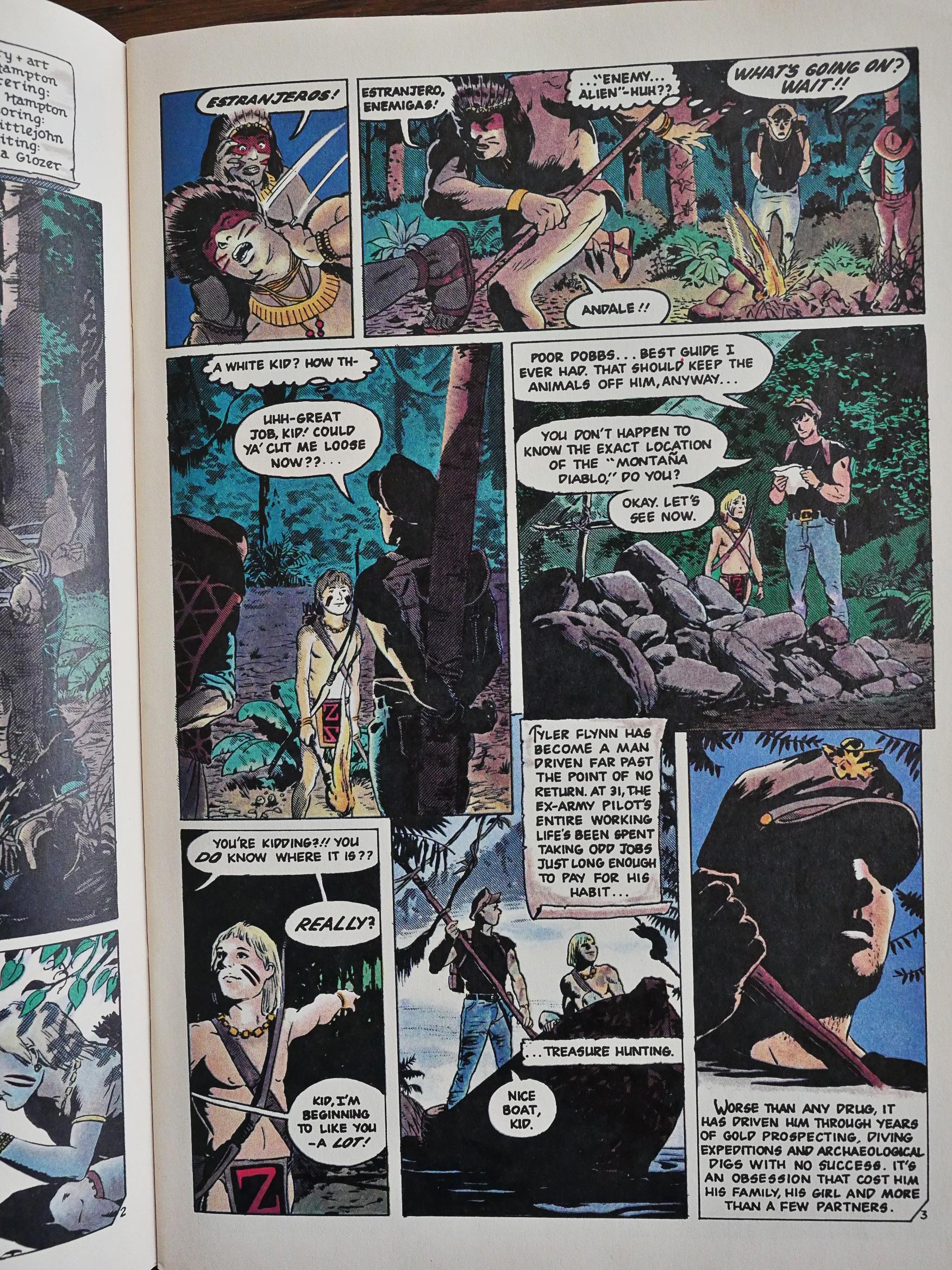

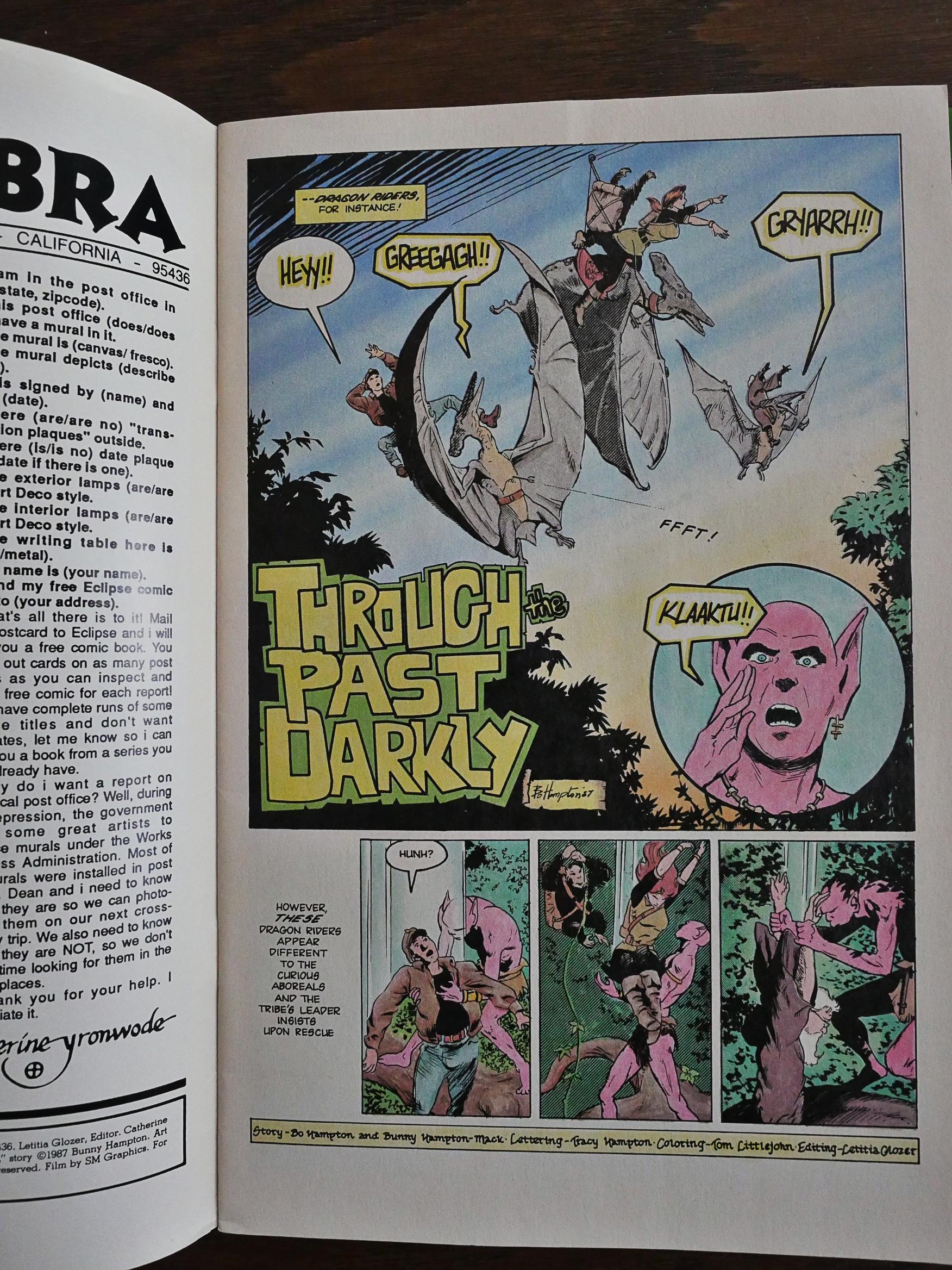

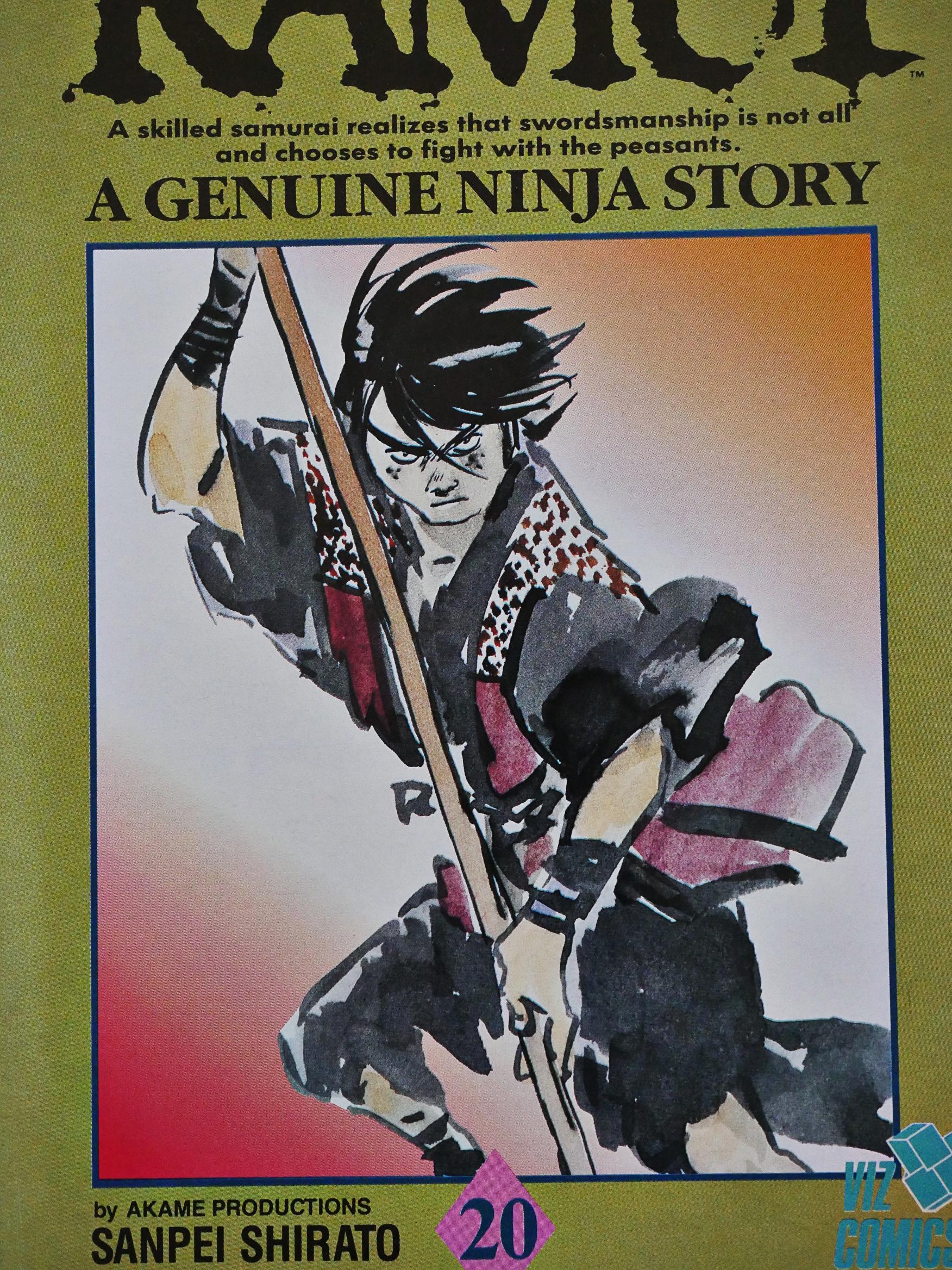

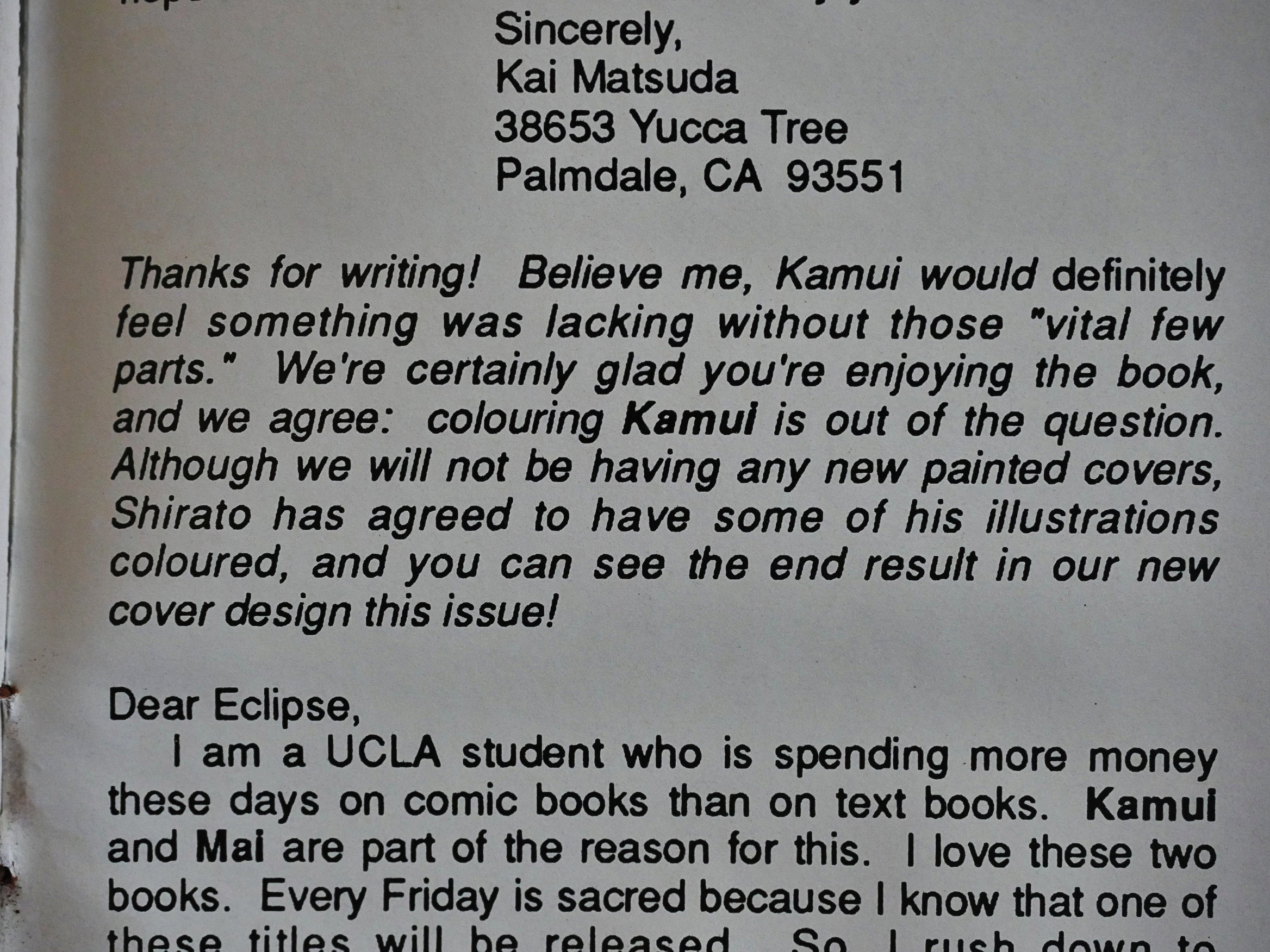

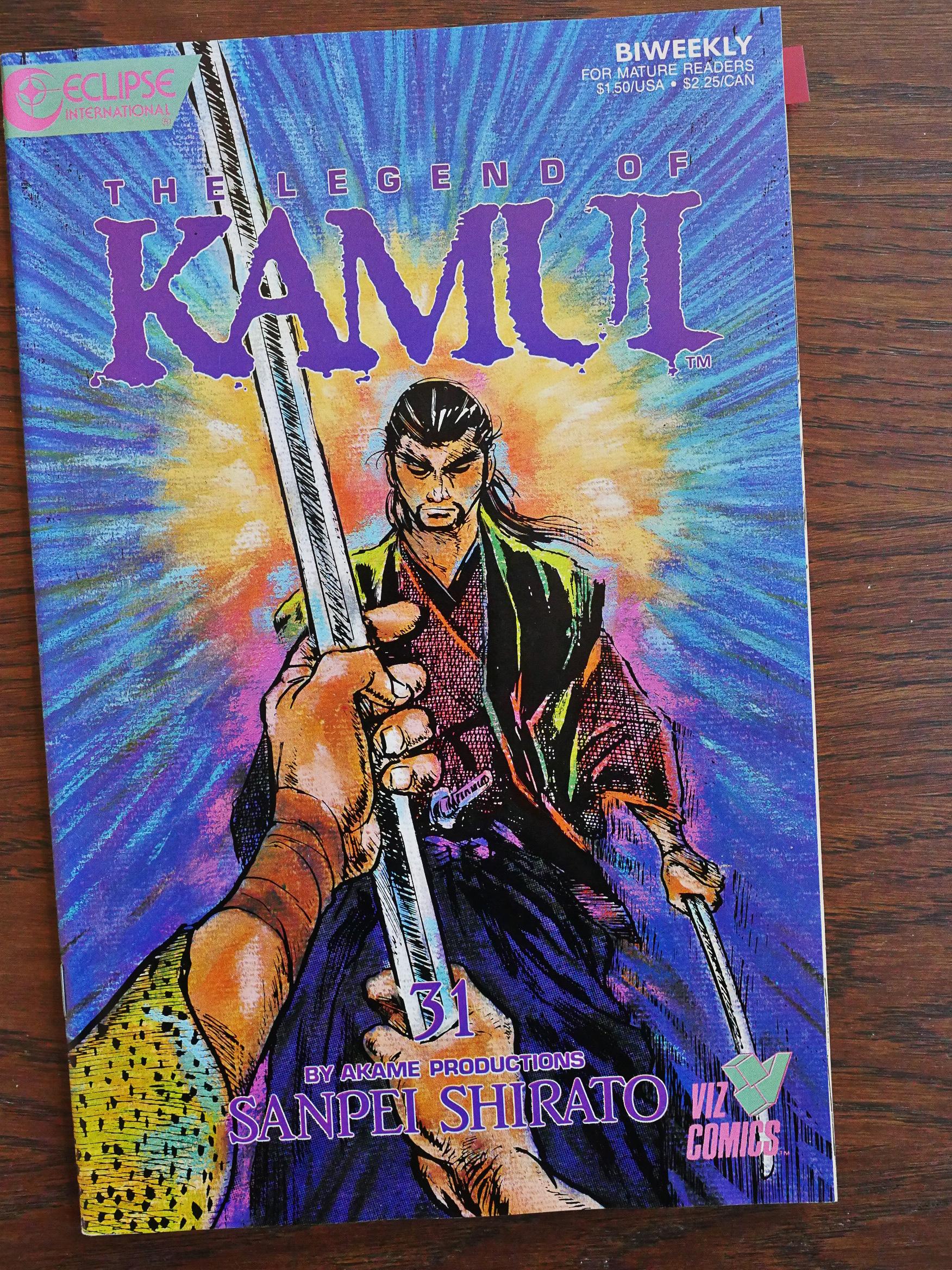

And Eclipse attacked the challenge wholeheartedly, it seems: They started three bi-monthly series in May 1987 (this one, Mai and Kamui), so it represented a significant part of their monthly output. Looking over the list of comics I have to read to complete this blog series, a bit less than half the remaining comics are translations of Japanese titles. For the non-Japanese comics, Eclipse would concentrate on graphic novels and mini-series, so there’s oodles of titles to go through, but not that many issues.

The format that eventually made a break-through in the US wasn’t this, though. This sold like hotcakes in the direct sales market, but it wasn’t a cultural phenomenon. That didn’t happen until the early 2000s, when Tokyopop started publishing un-flopped (i.e., reading in the original Japanese right-to-left order), cheap smaller-sized books instead of stapled, normal-US-sized, flopped pamphlets, which is what Eclipse (co-publishing with Viz) was doing here.

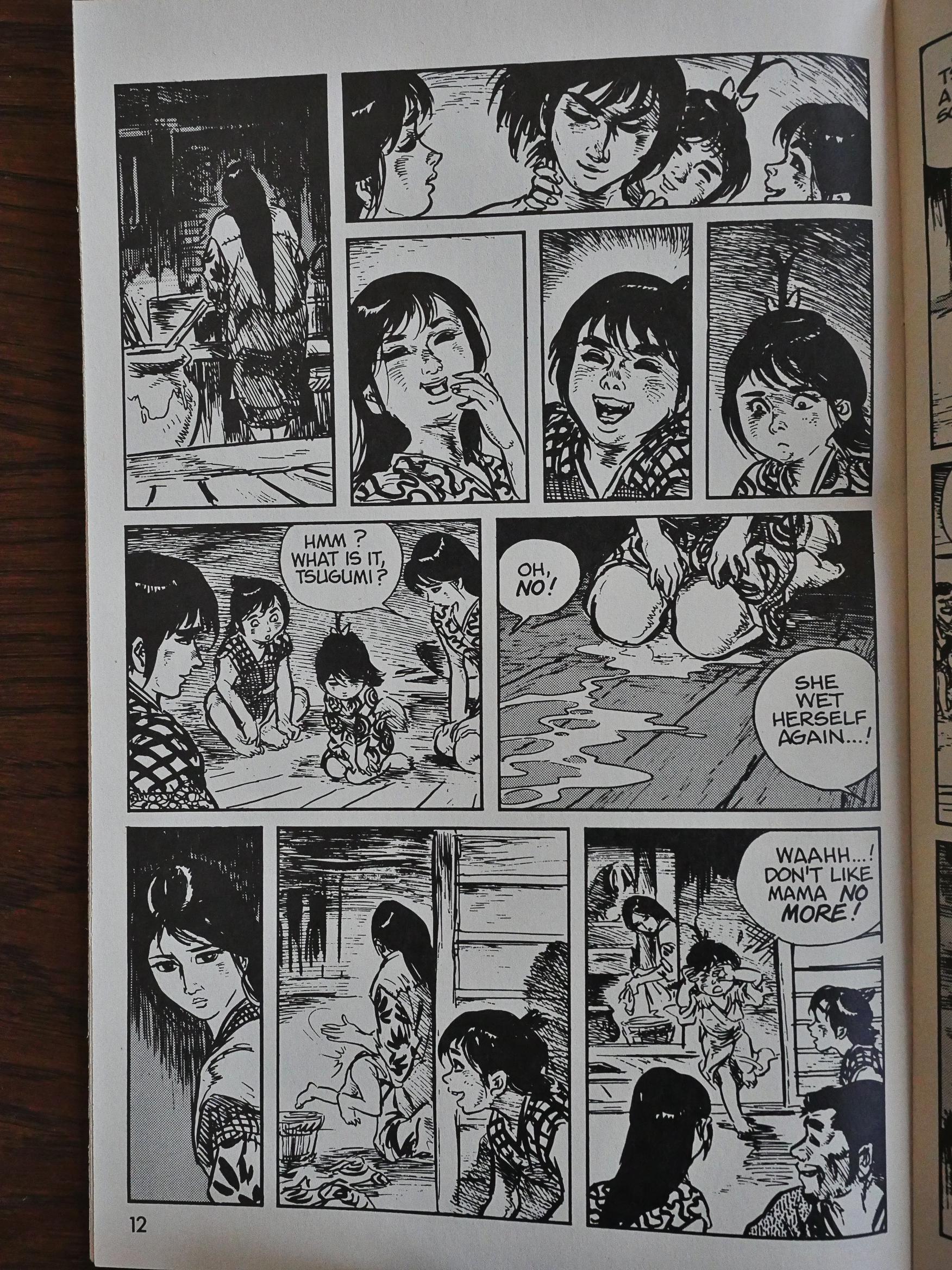

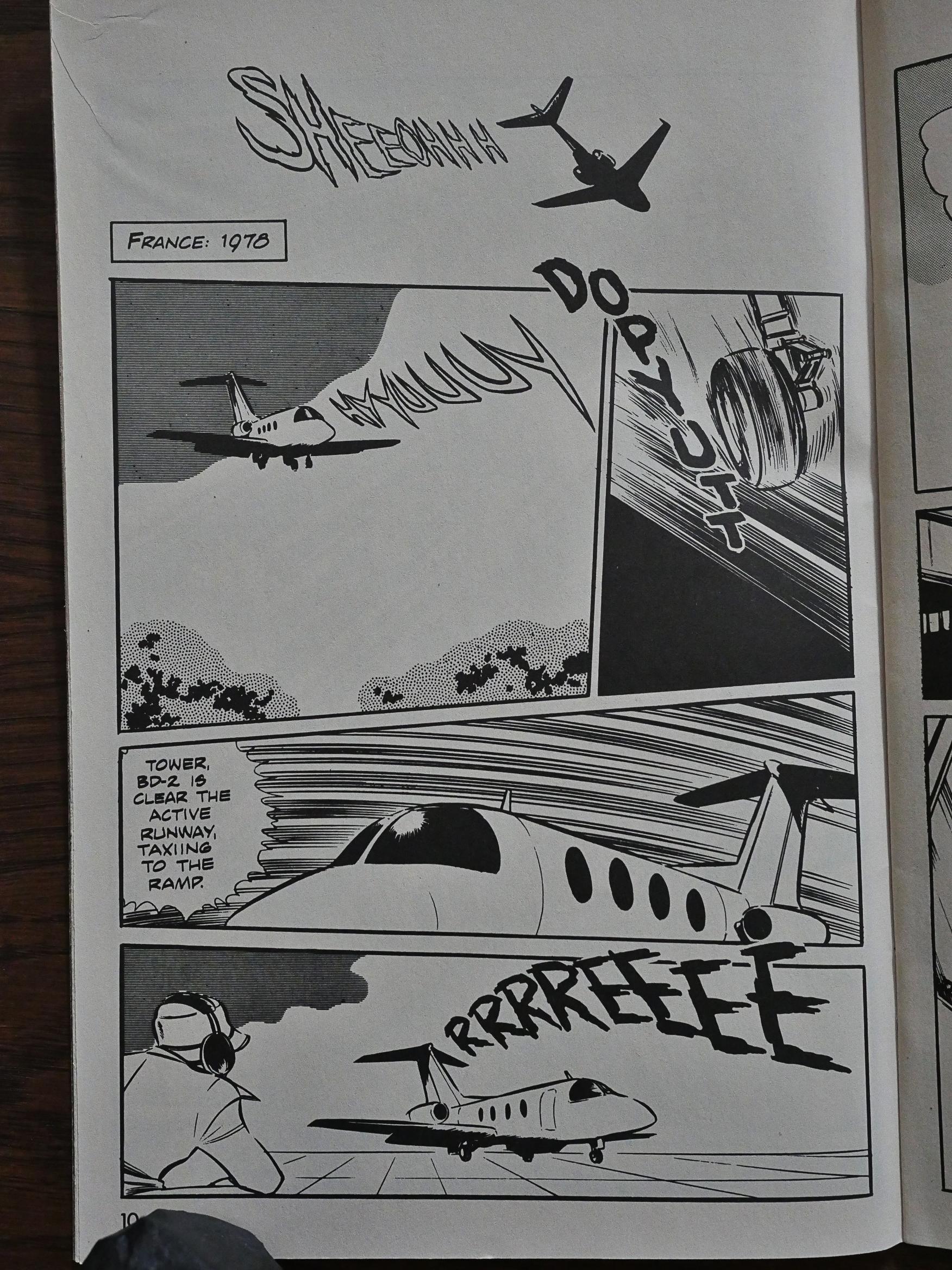

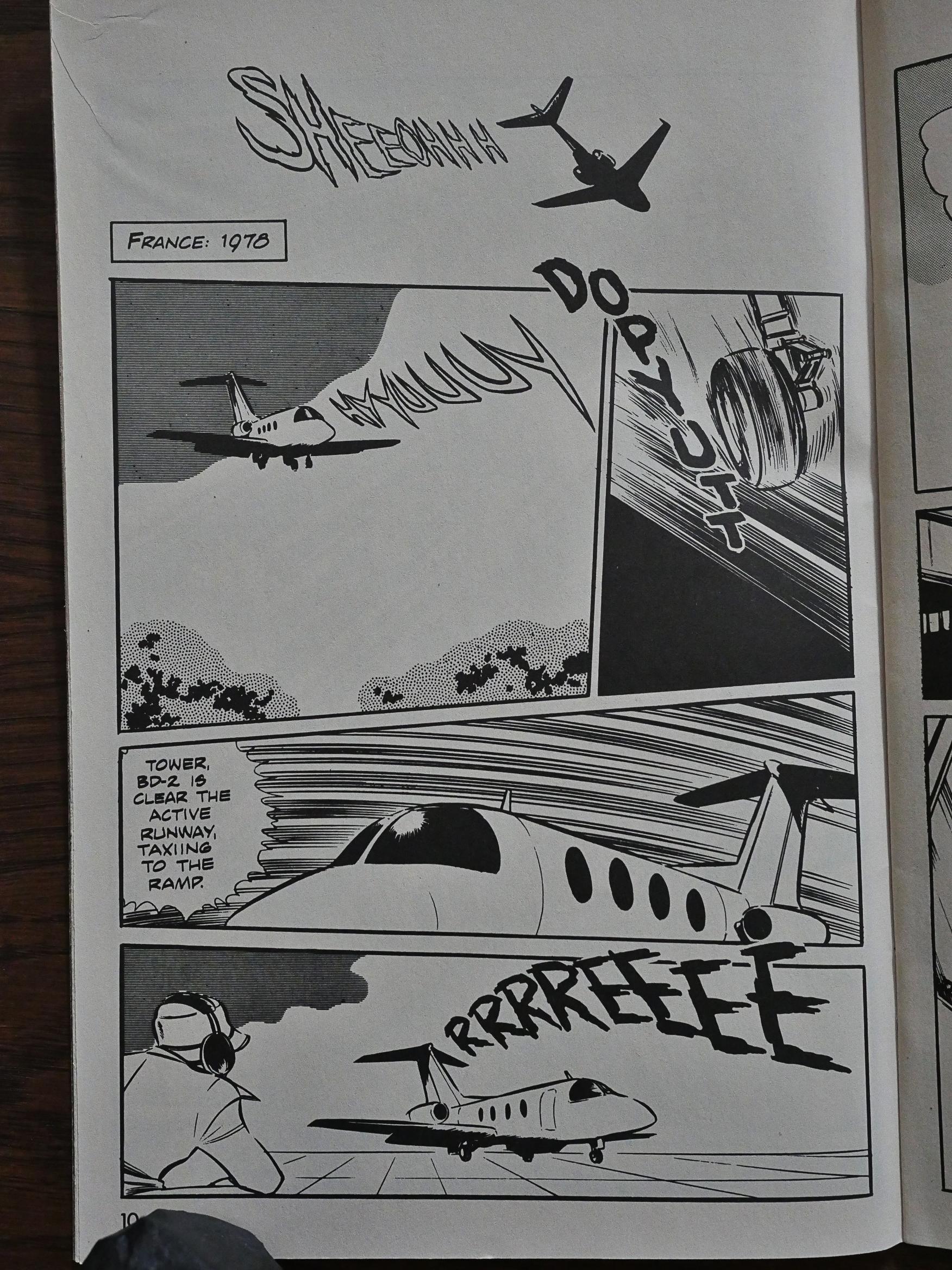

And it’s strange to read these comics now. The pages are so big! The lettering is so big! These books are so short! It’s a weird feeling going back to these floppies after reading the “new” (i.e., more Japanese) format for fifteen years now.

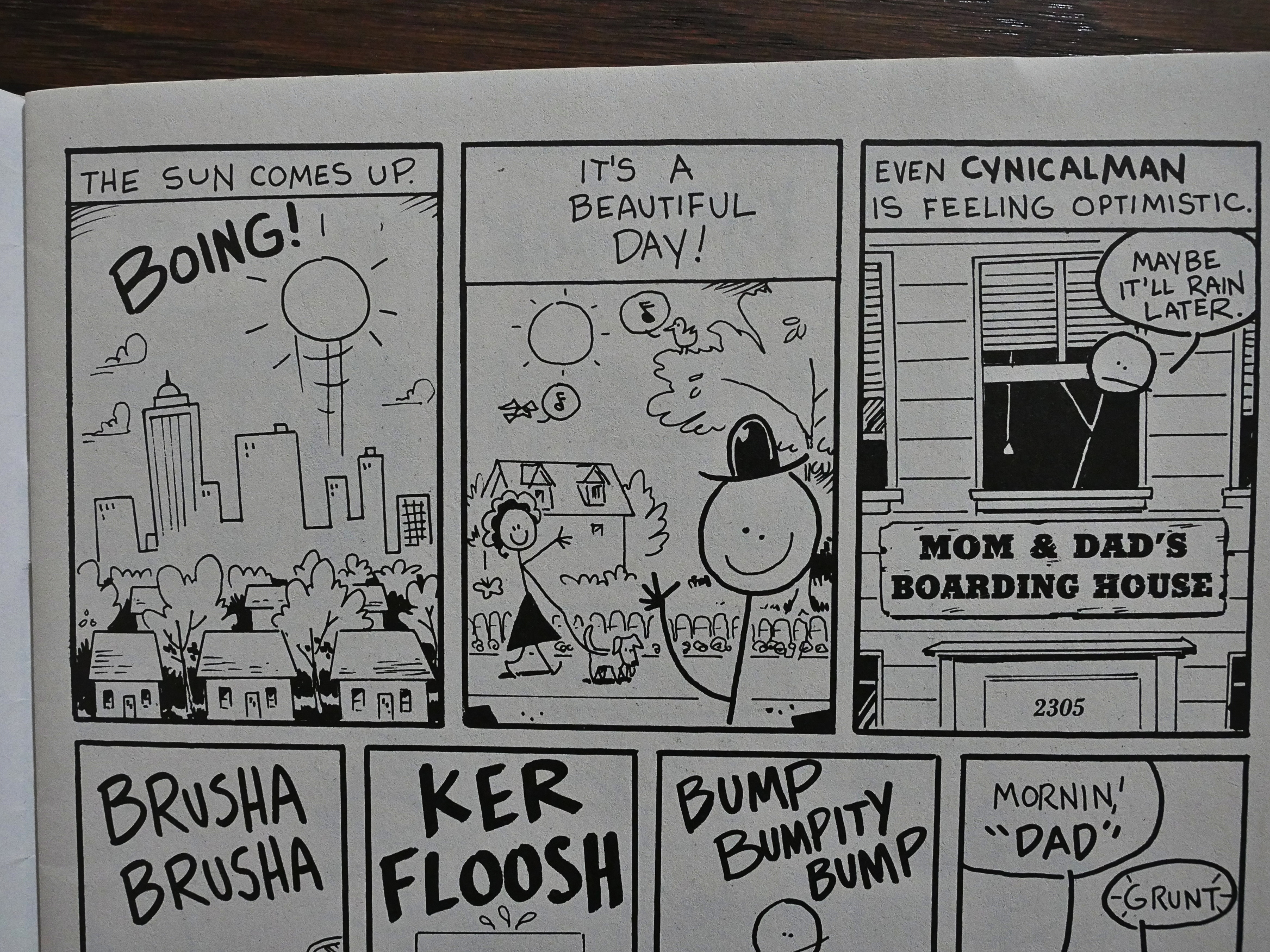

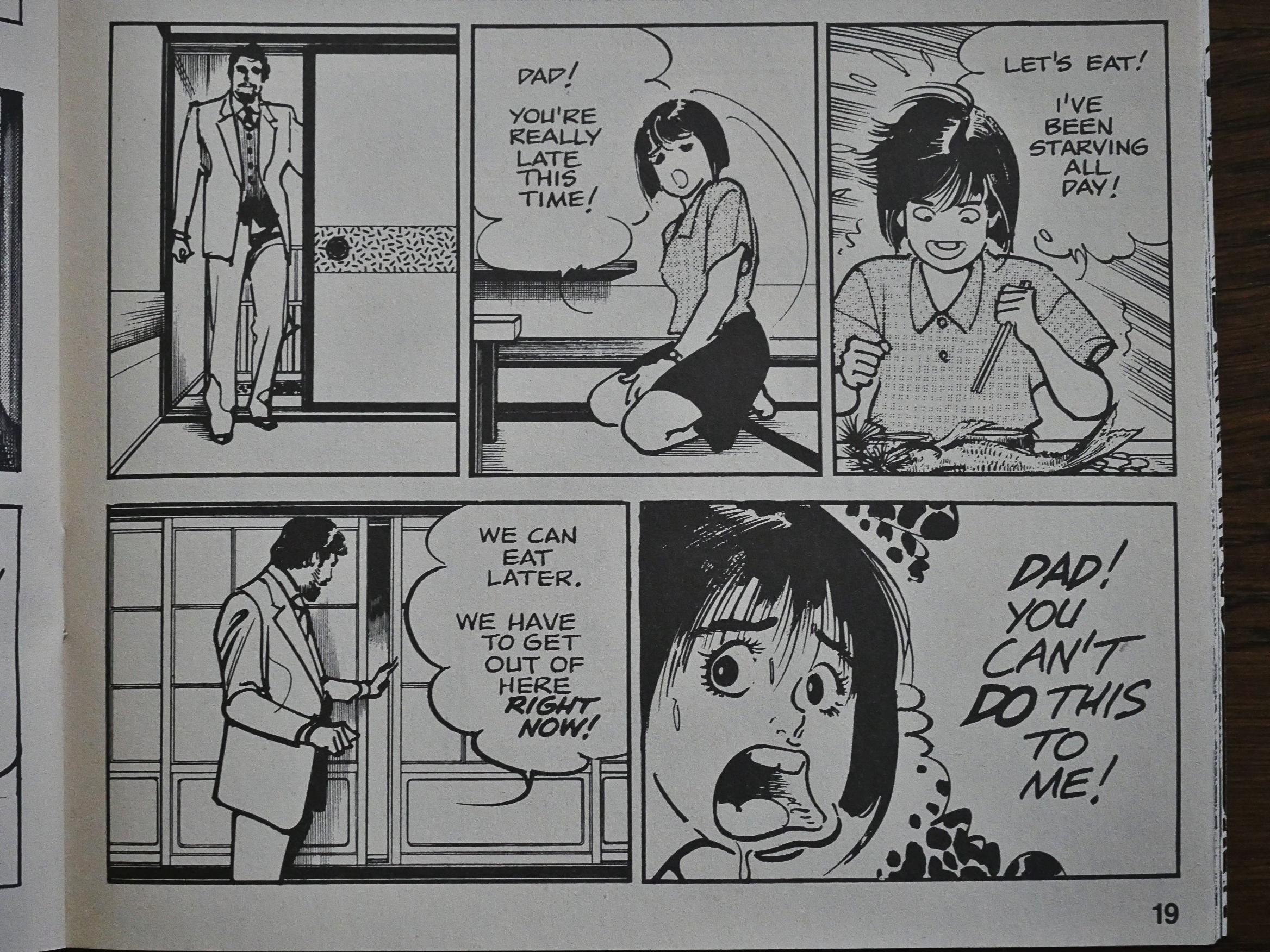

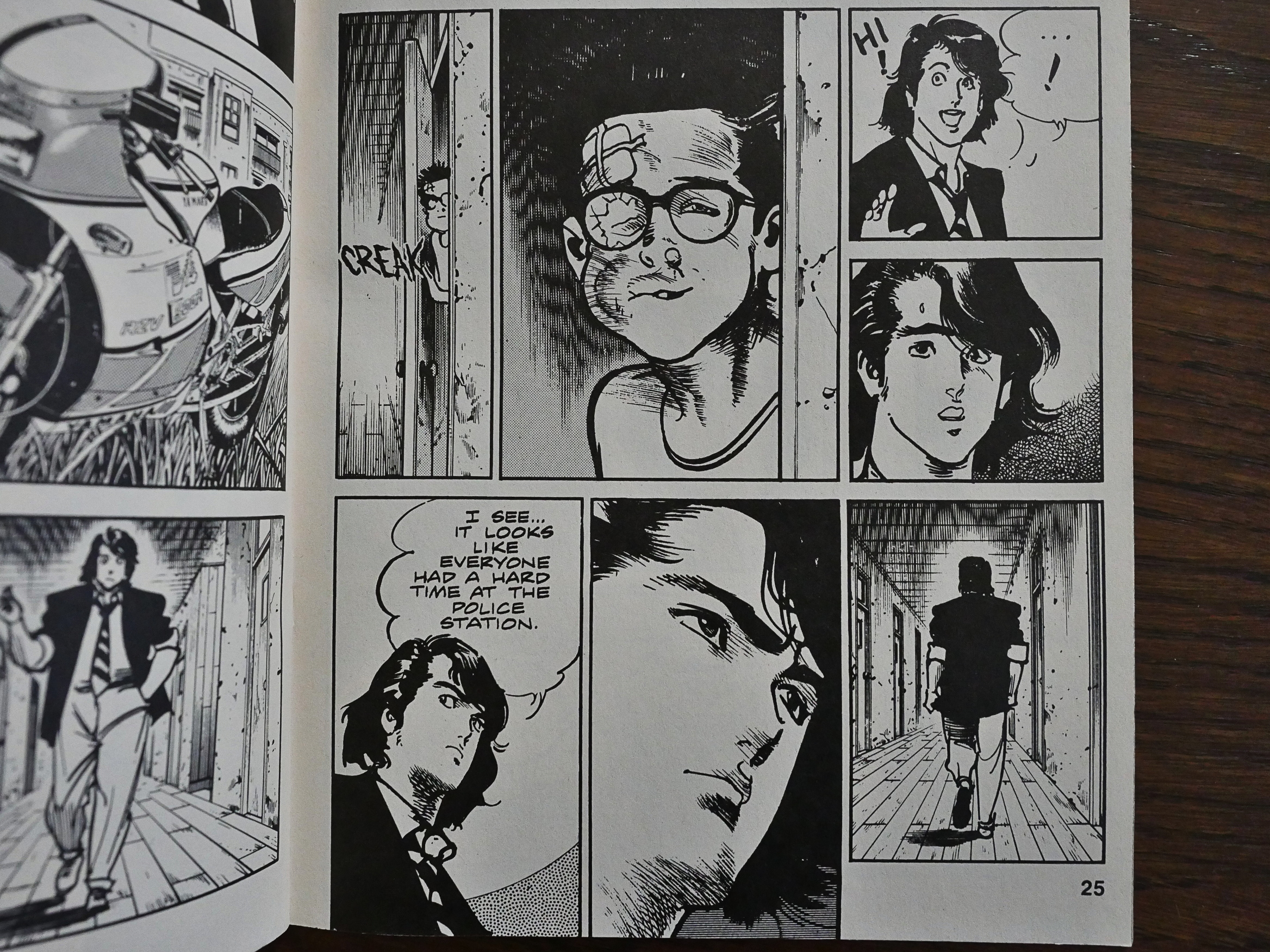

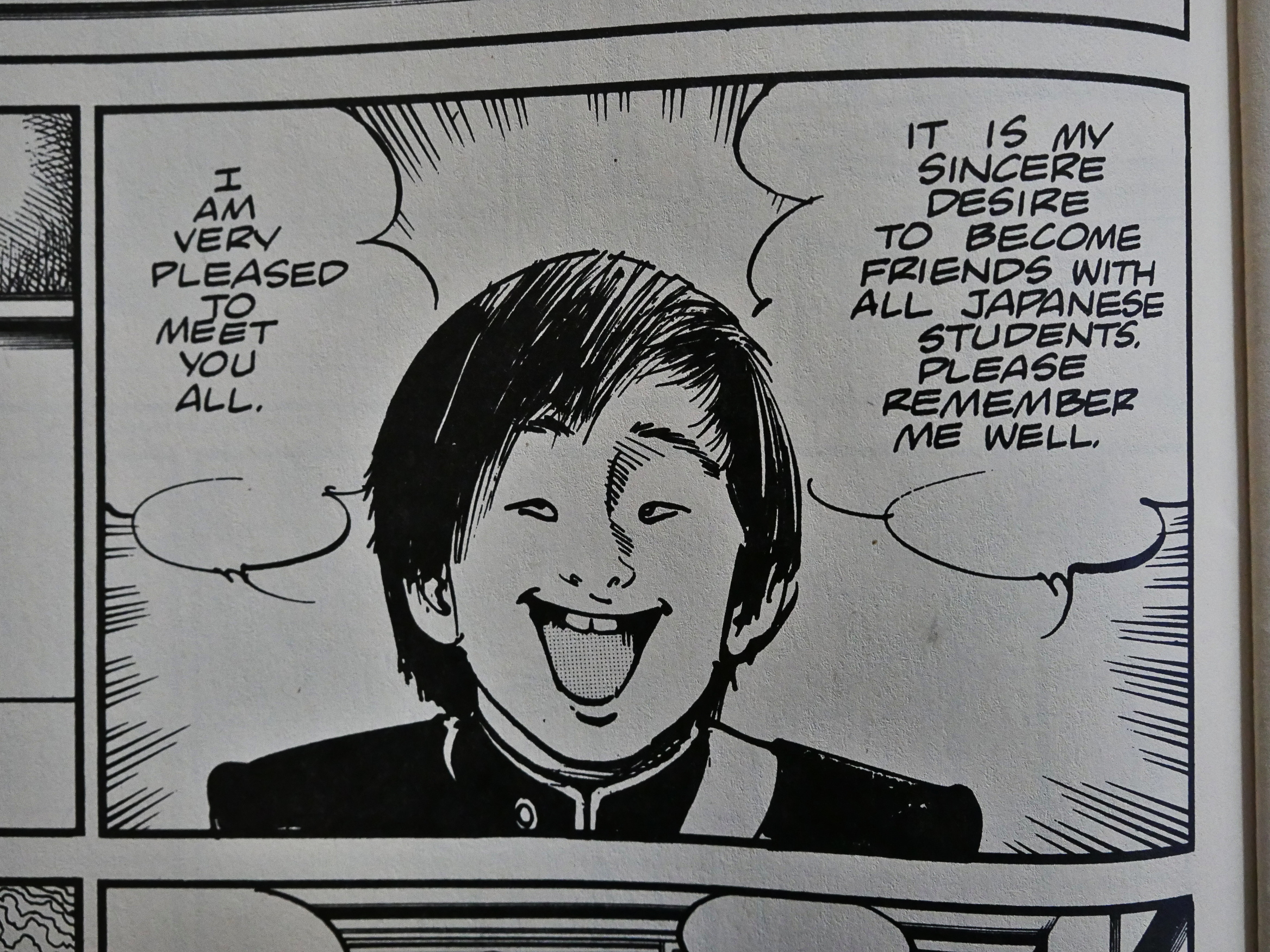

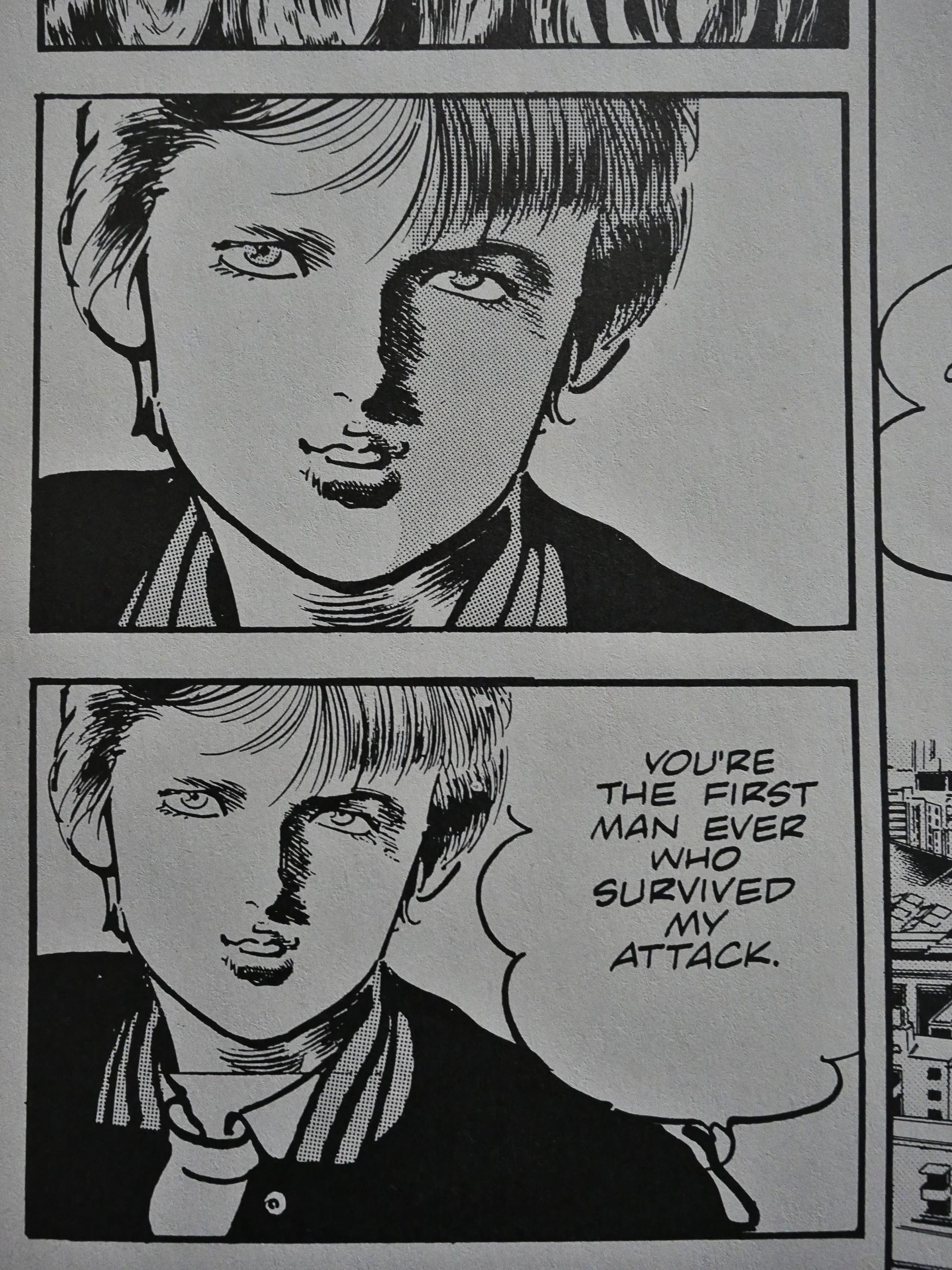

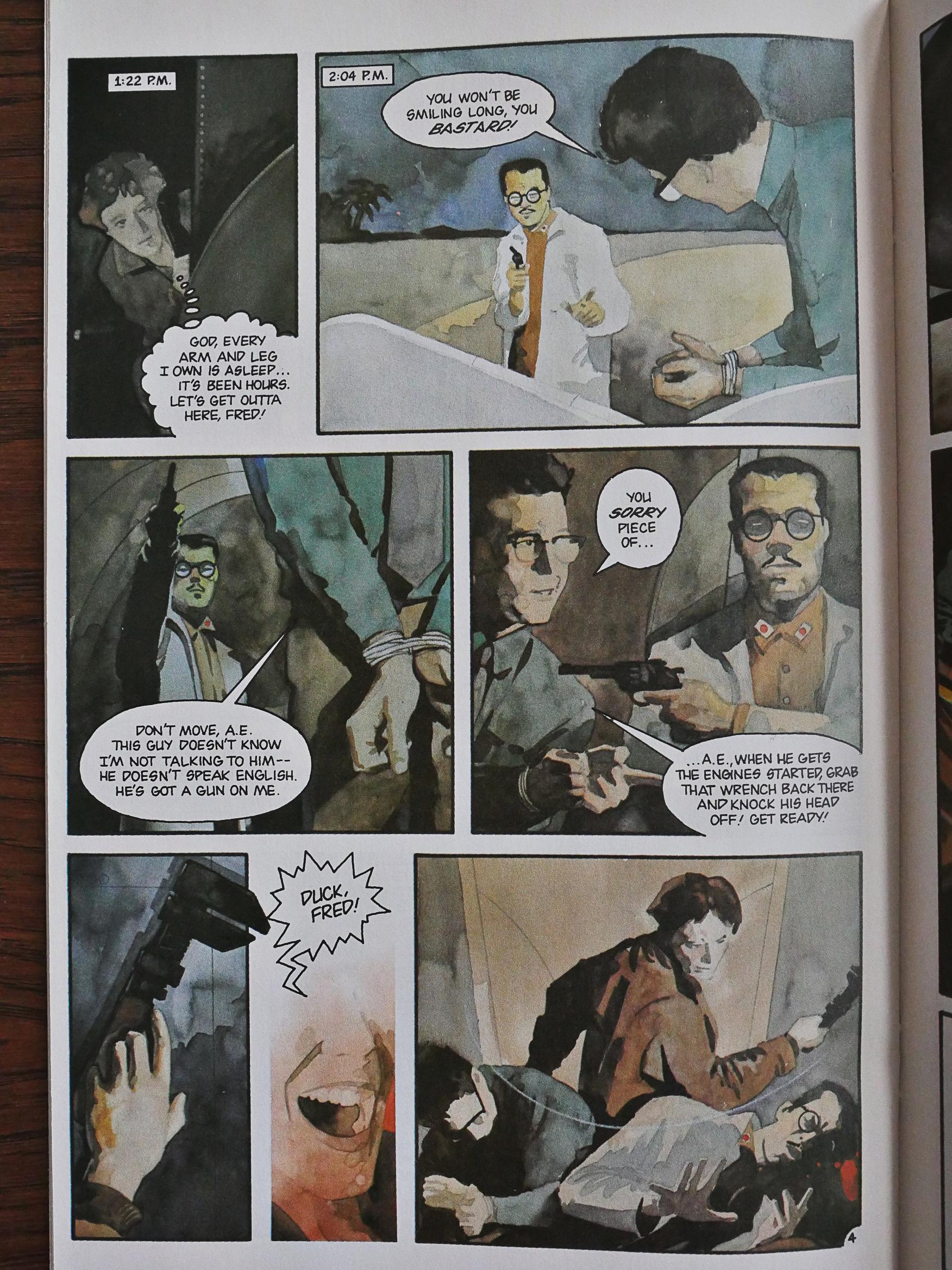

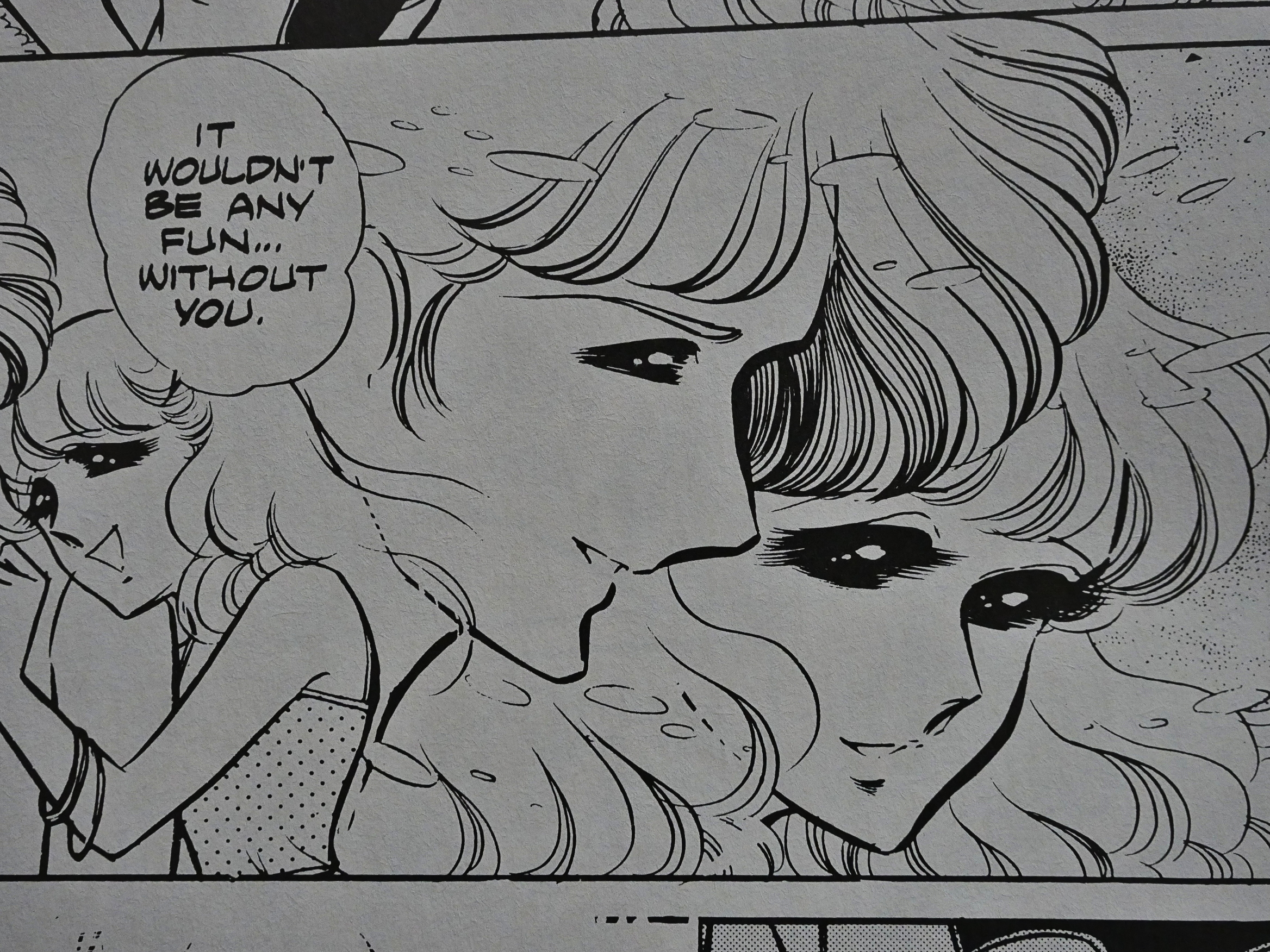

This is an action book, but Kaoru Shintani had also done romance comics before starting this series, and you can see the influence in the extravagant hairstyles and the not-very-macho posture of the hero (to the right here).

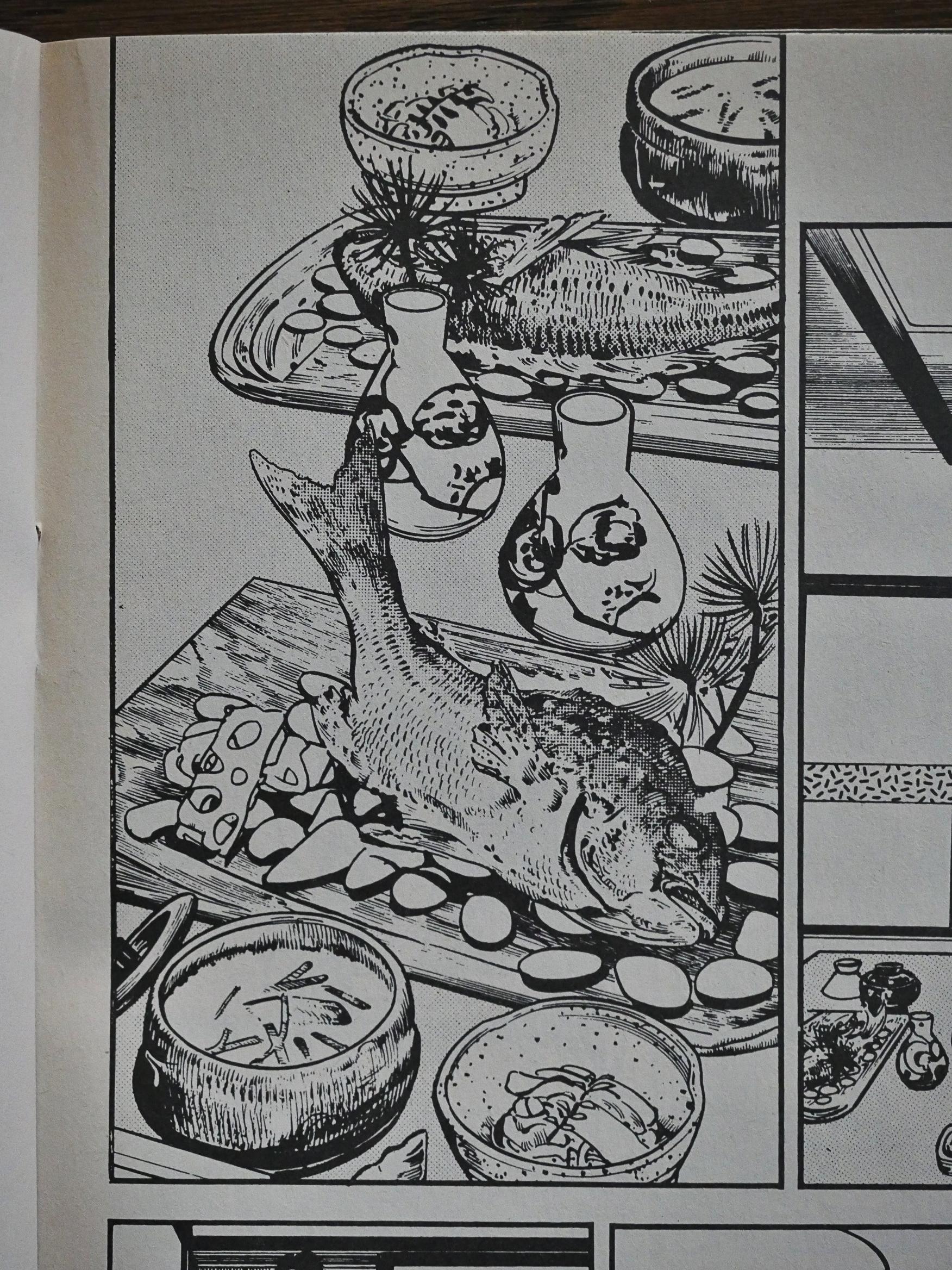

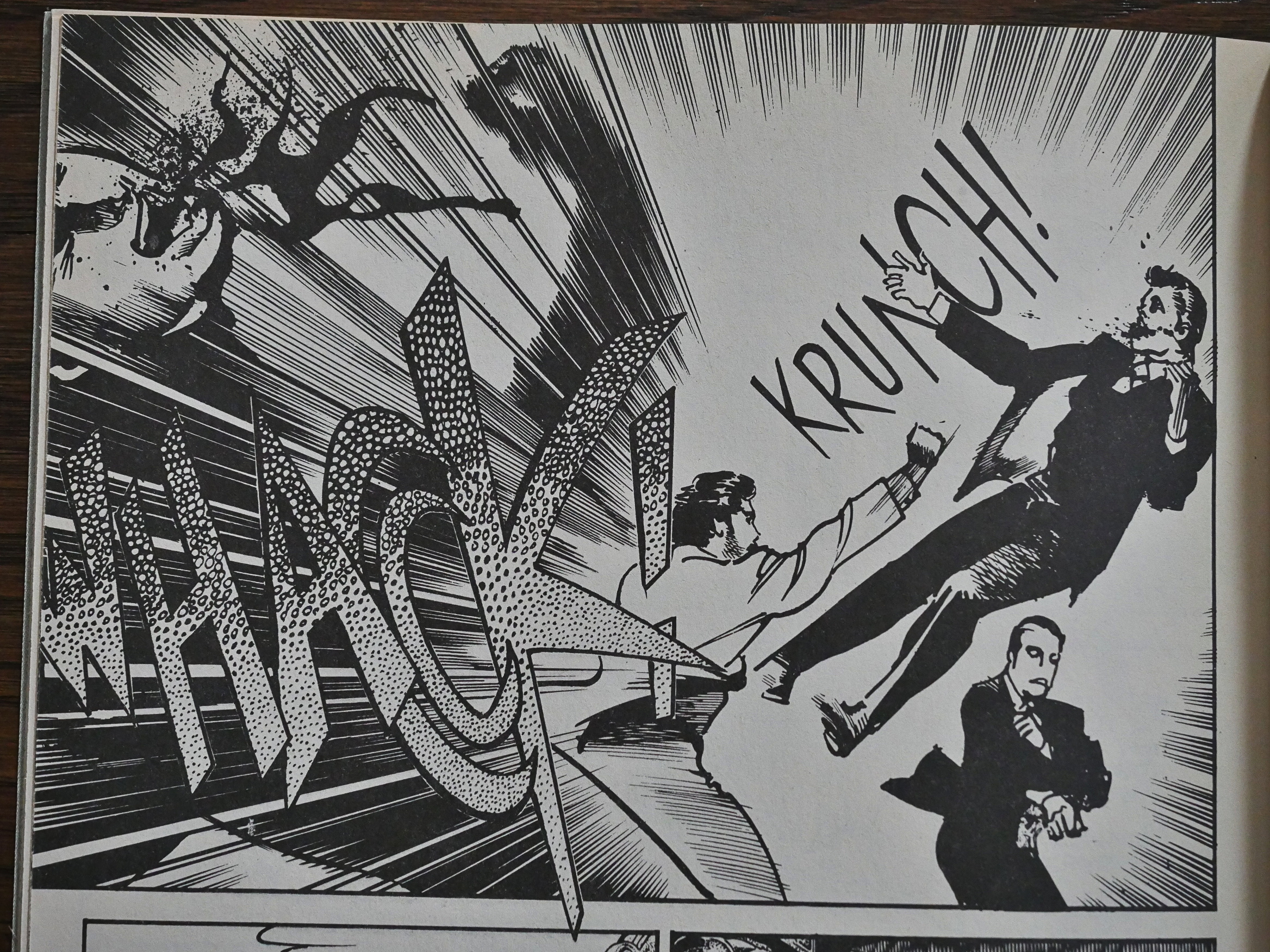

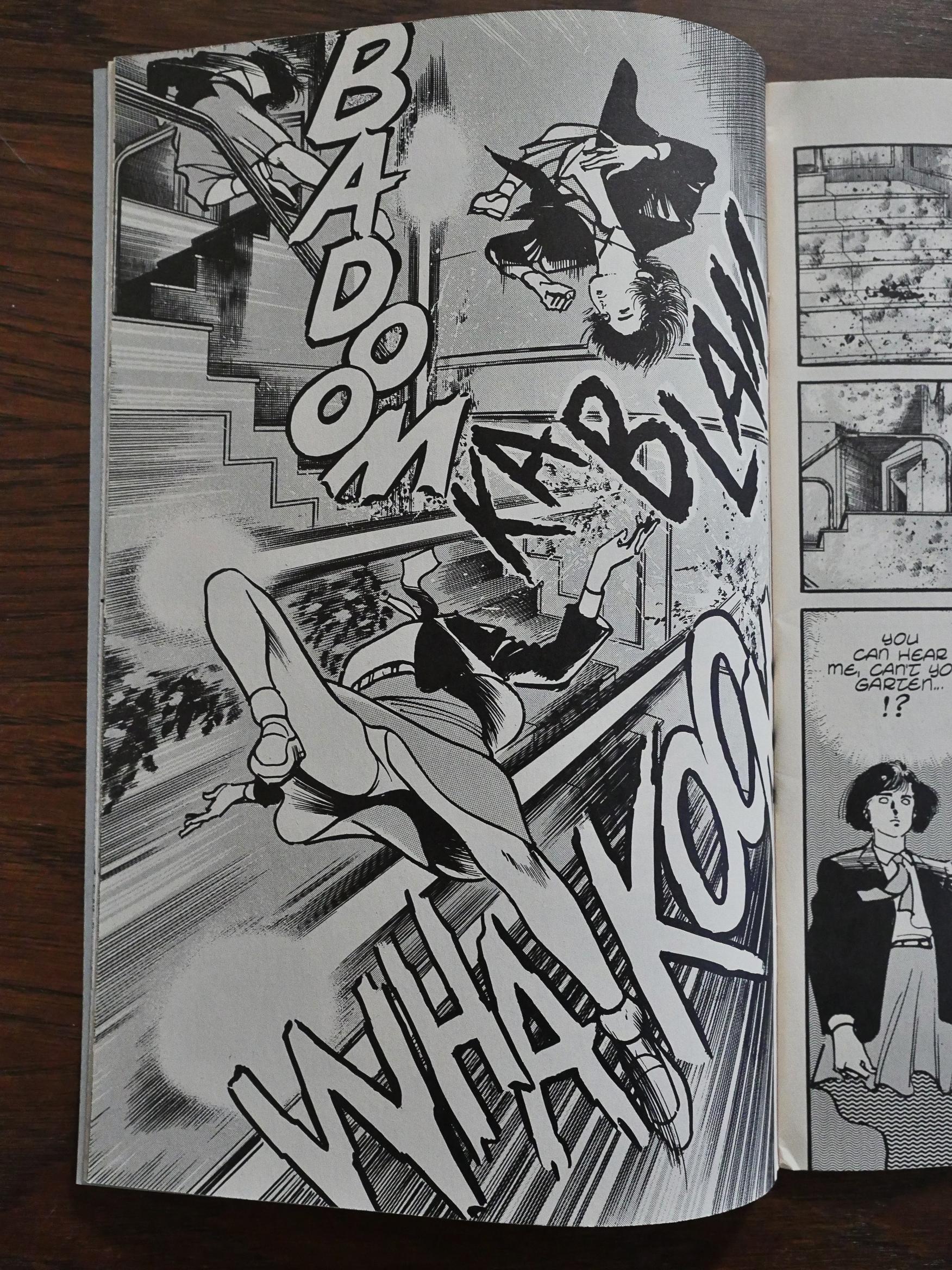

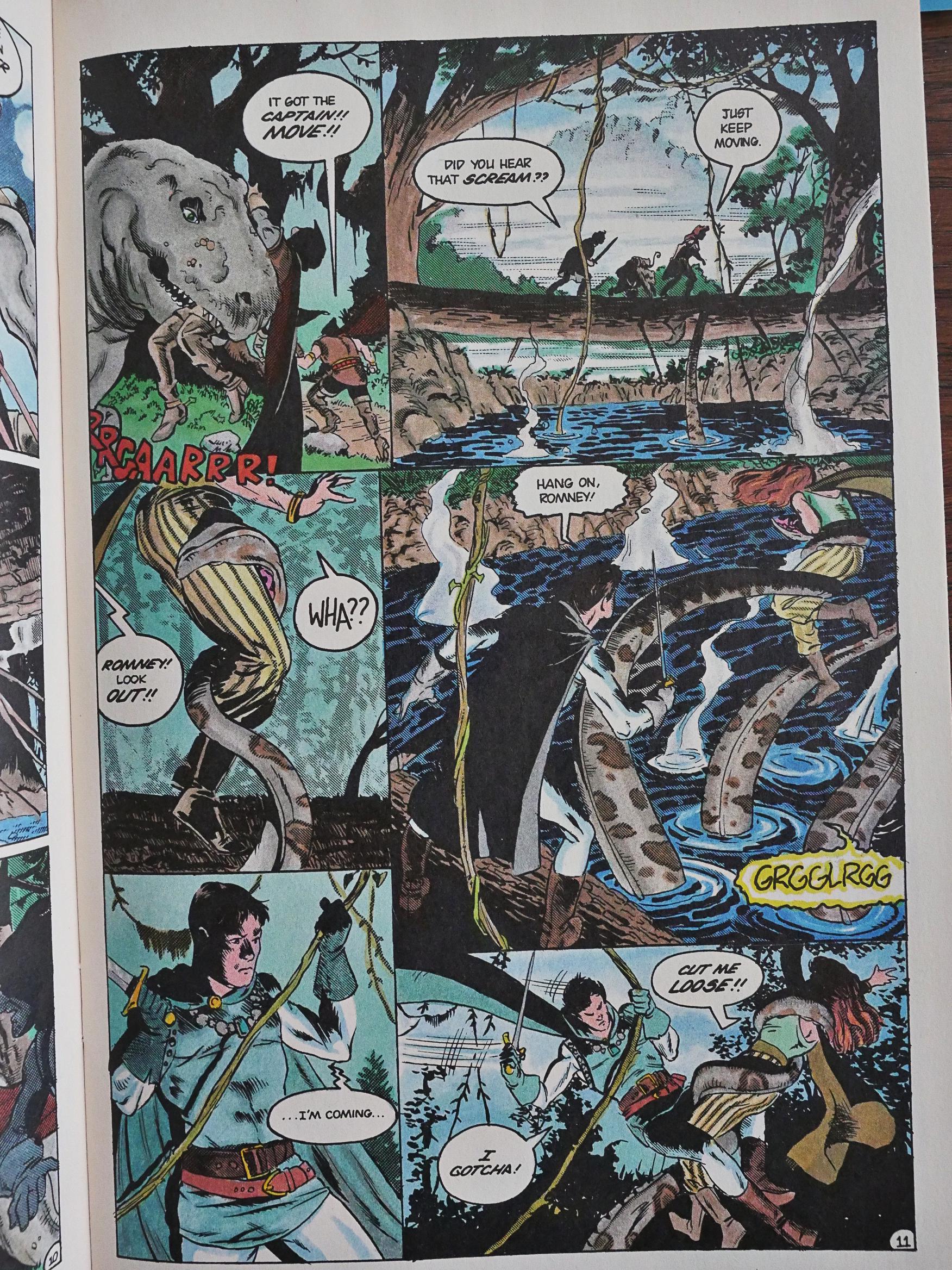

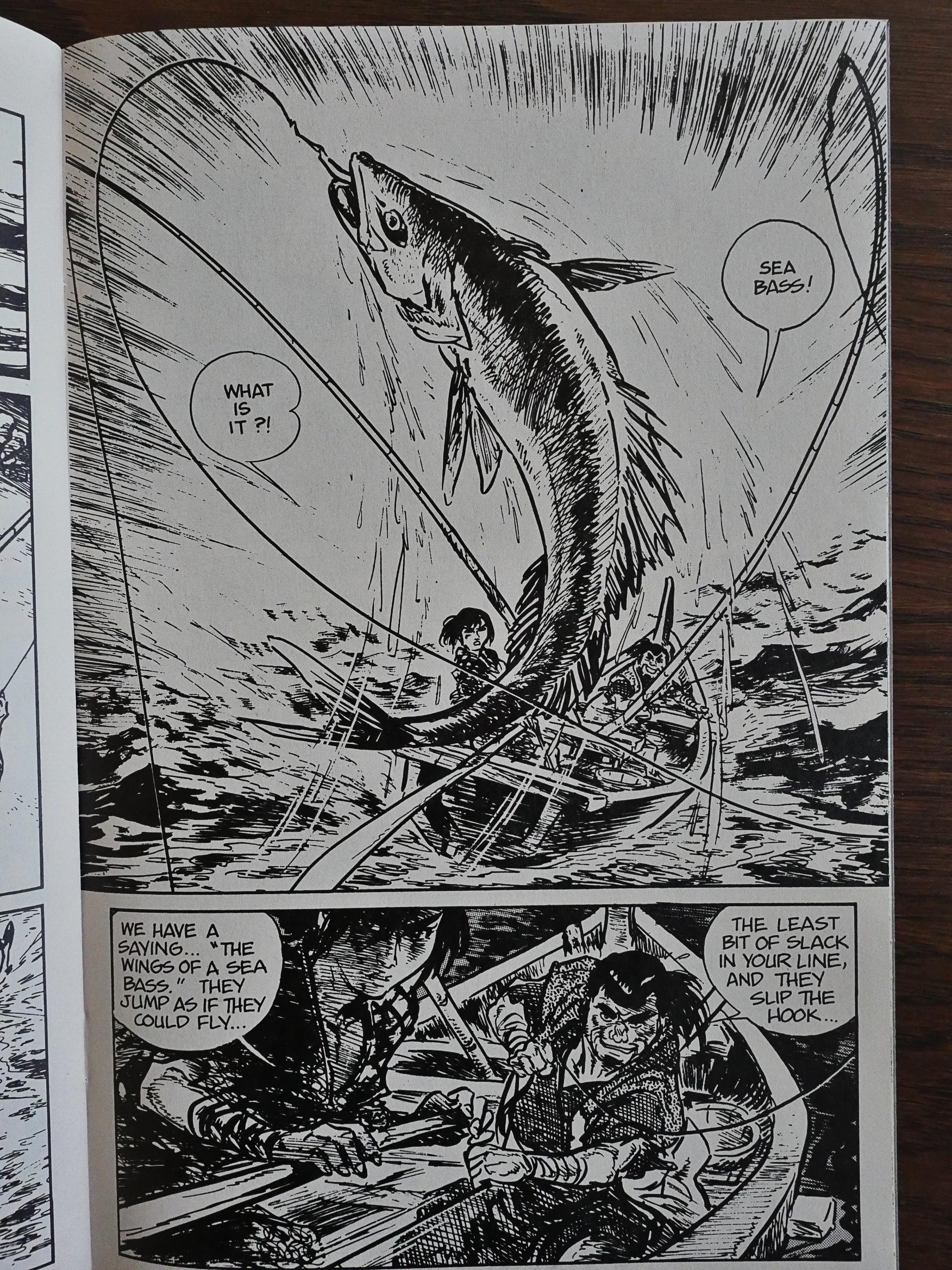

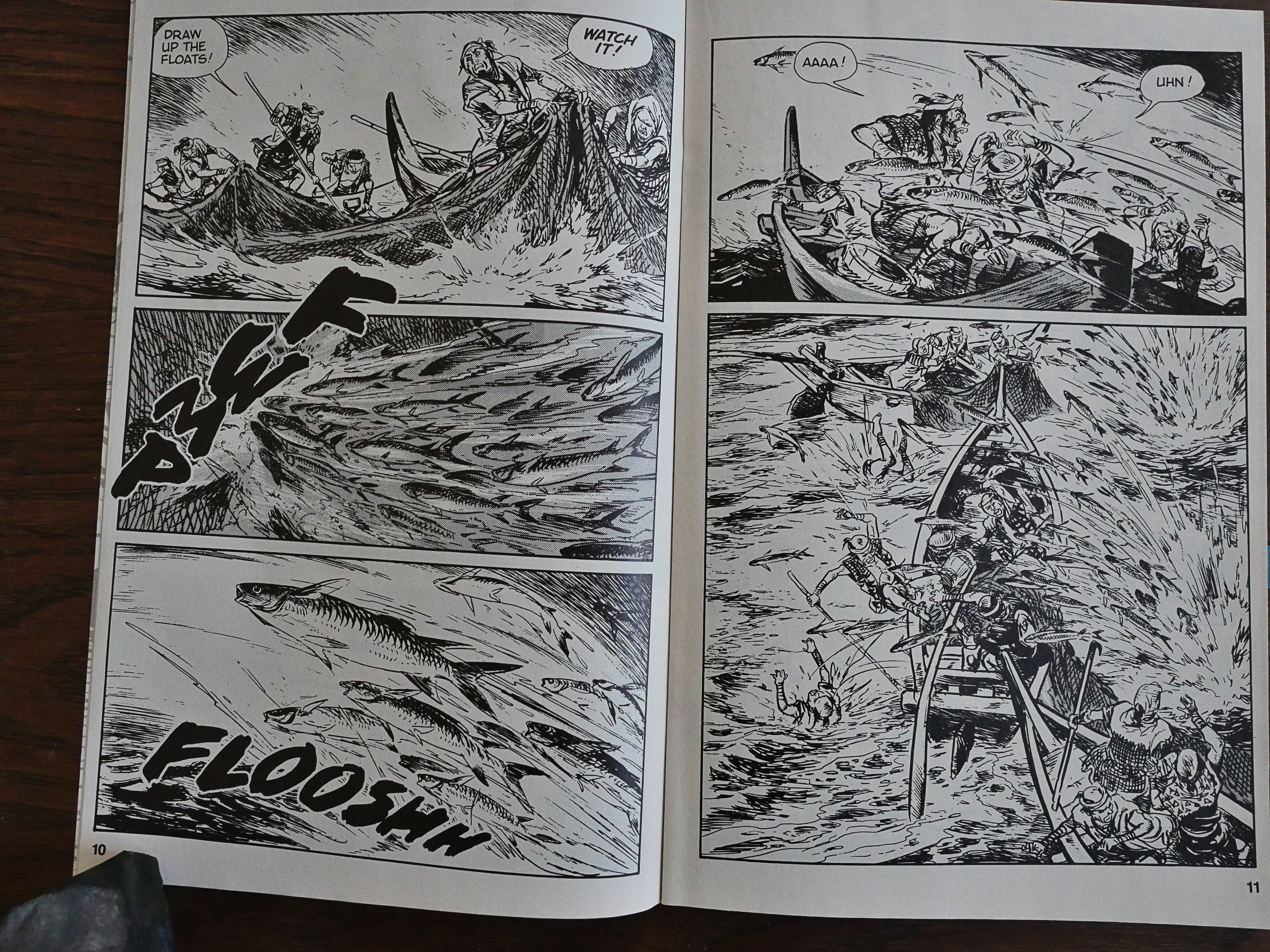

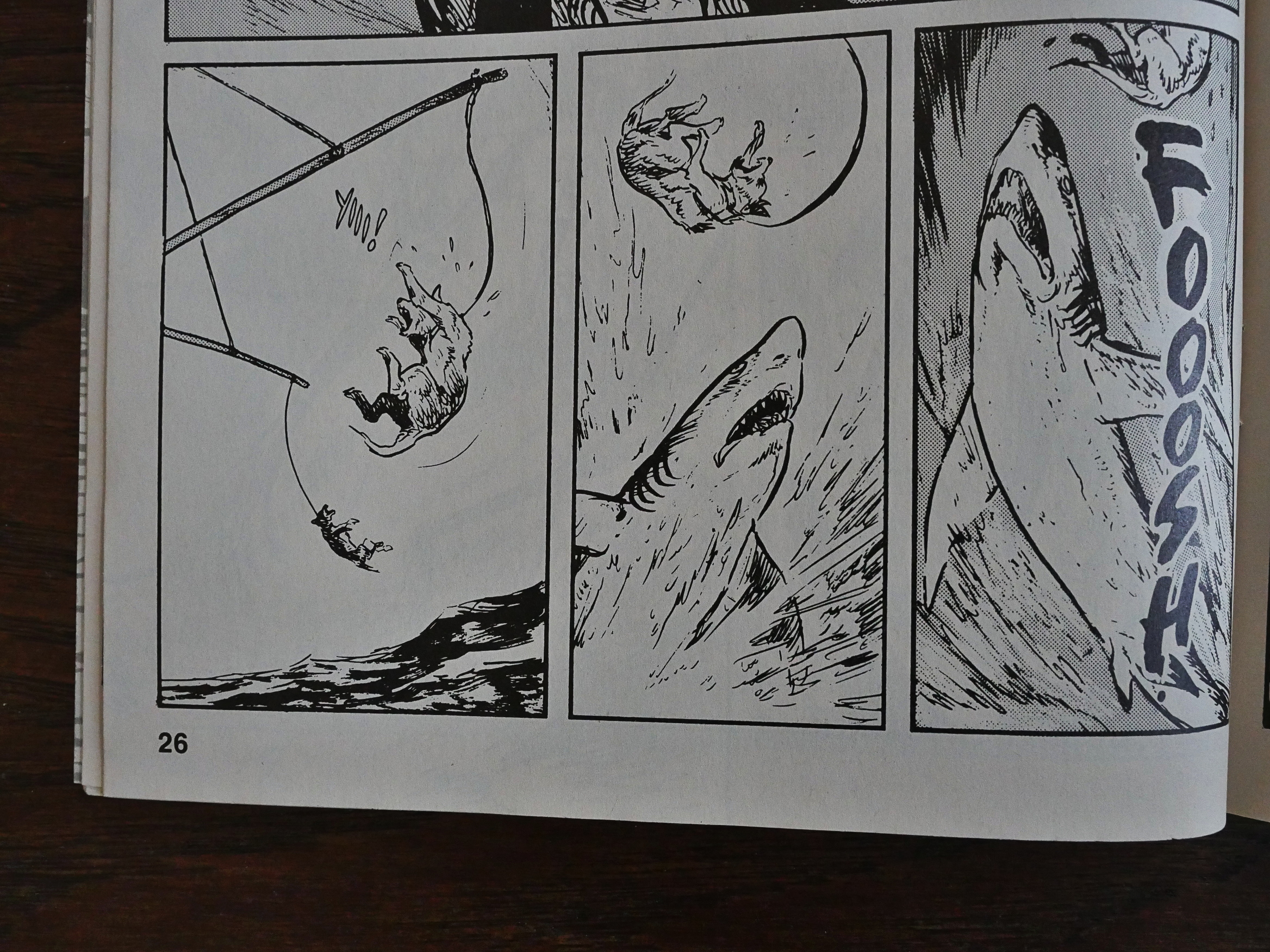

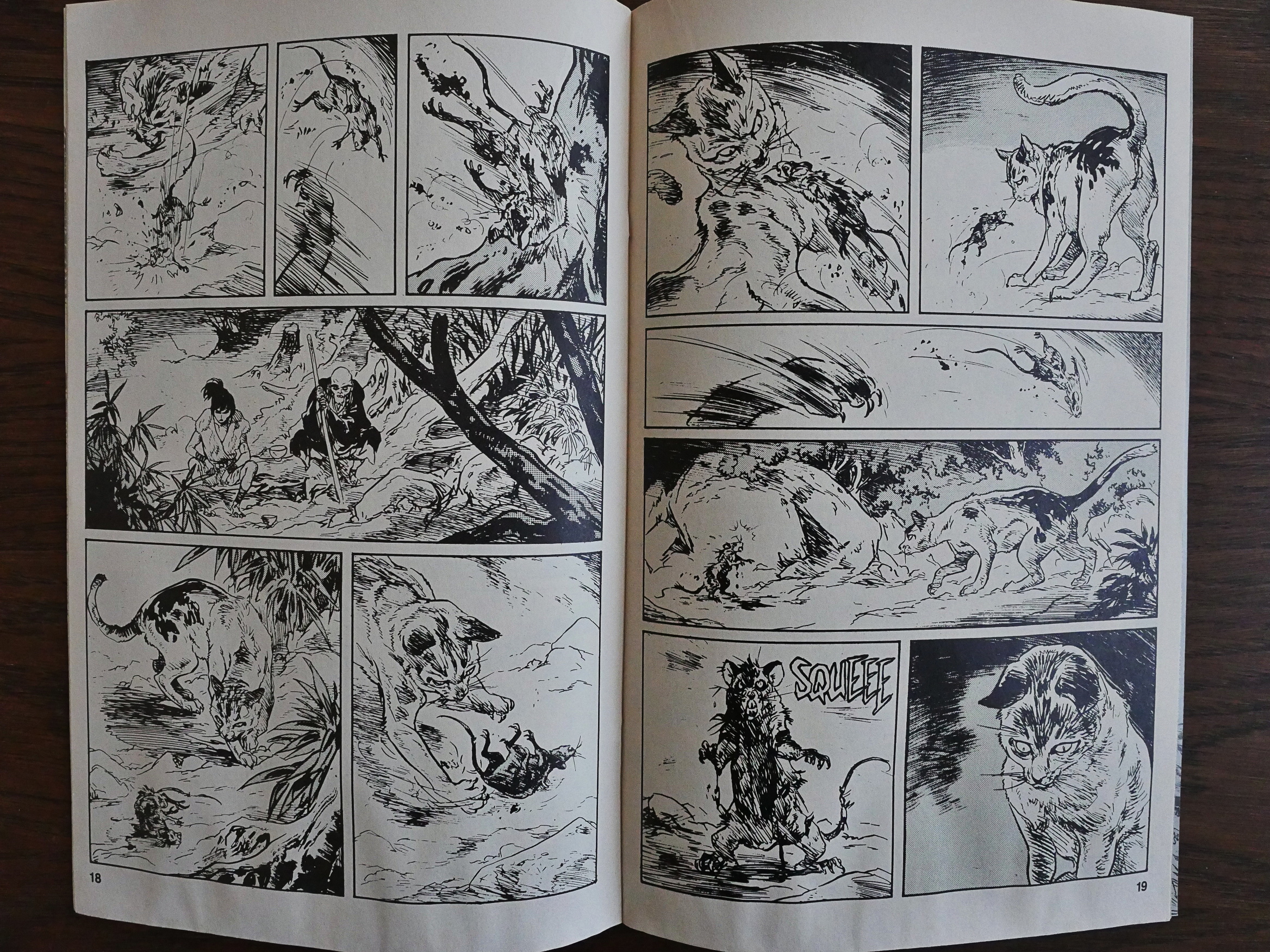

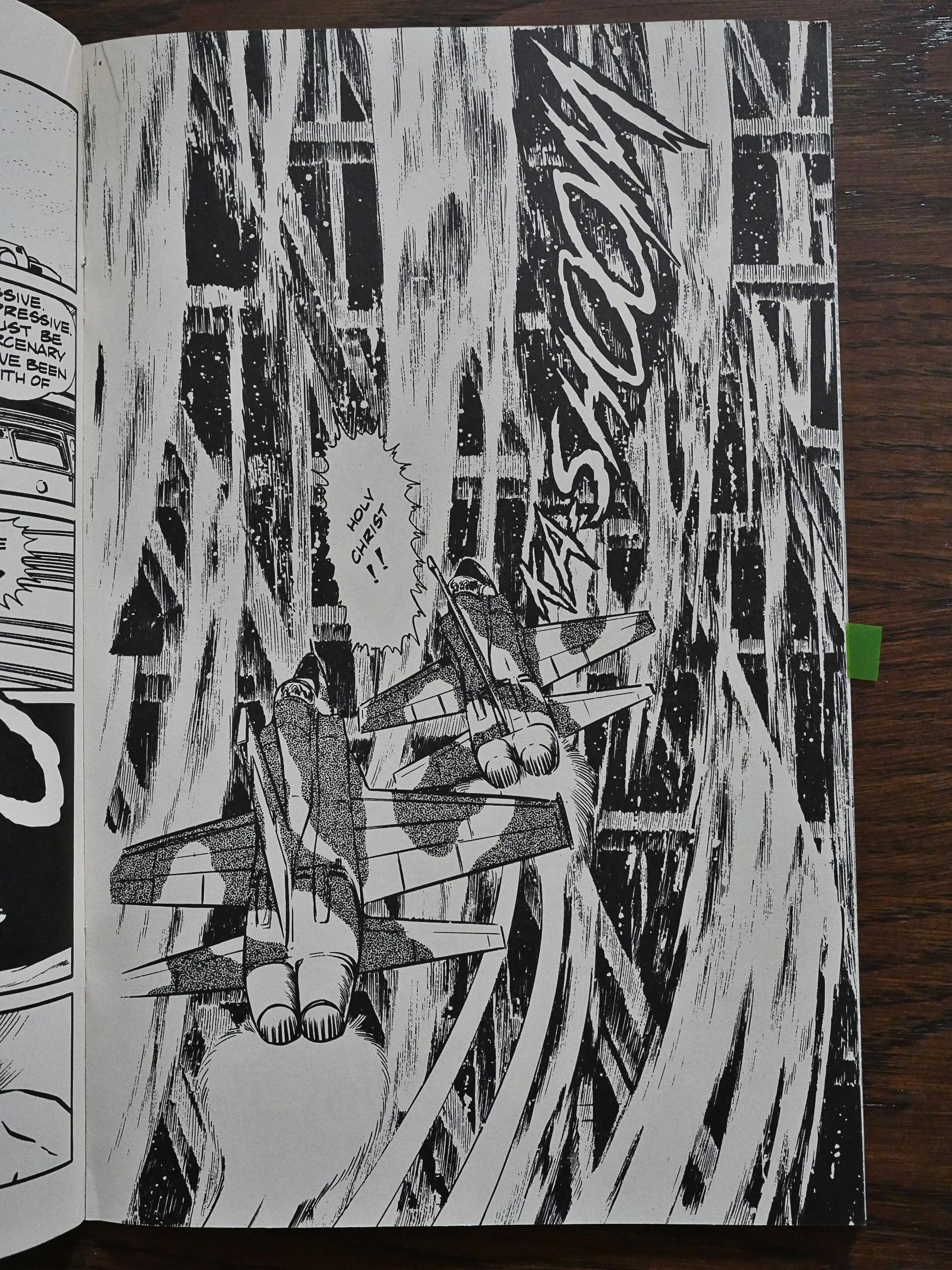

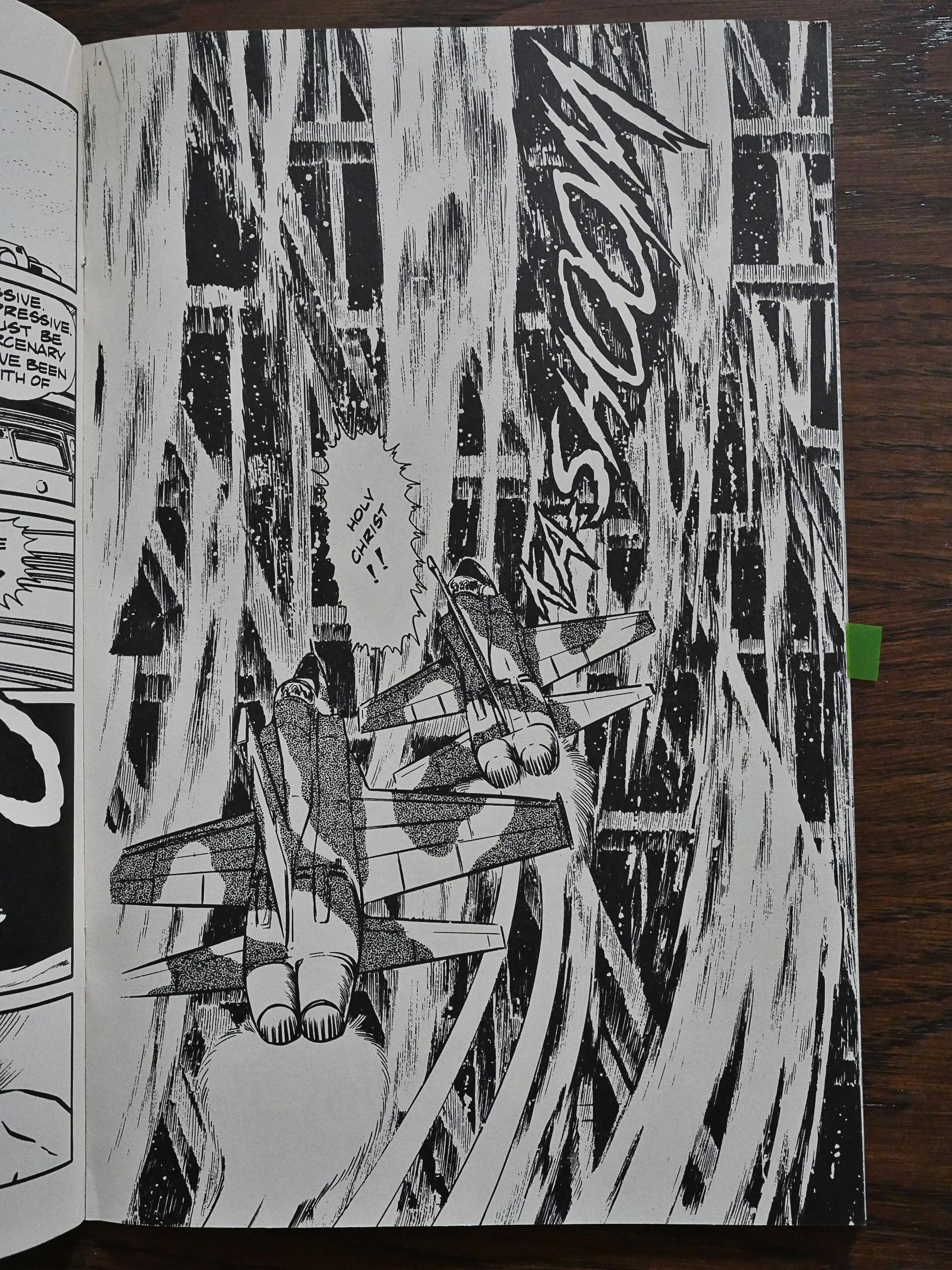

These comics read fast. Quite decompressed. I read the entire stack this (long) evening, and that’s… 1100 pages or something? There are a lot scenes of fighter planes fighting, and they flow past very quickly, even if they’re the prettiest part of the book. I’m assuming Kaoru Shintani has a coterie of assistants whose only job it is to draw pages upon pages of airplanes whizzing past (virtually all Japanese children’s comics are created by studios headed by one person, but created by a number of uncredited people).

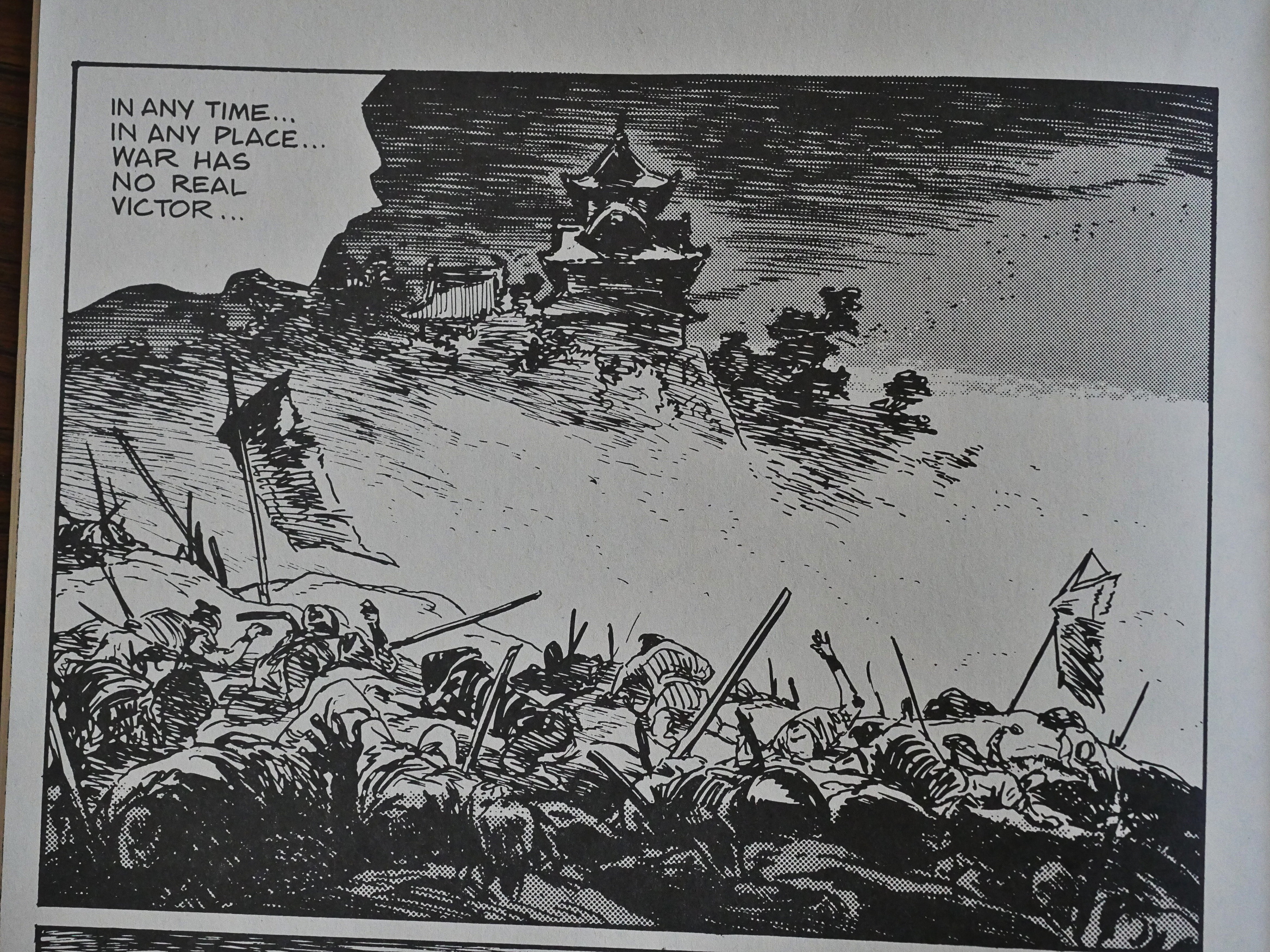

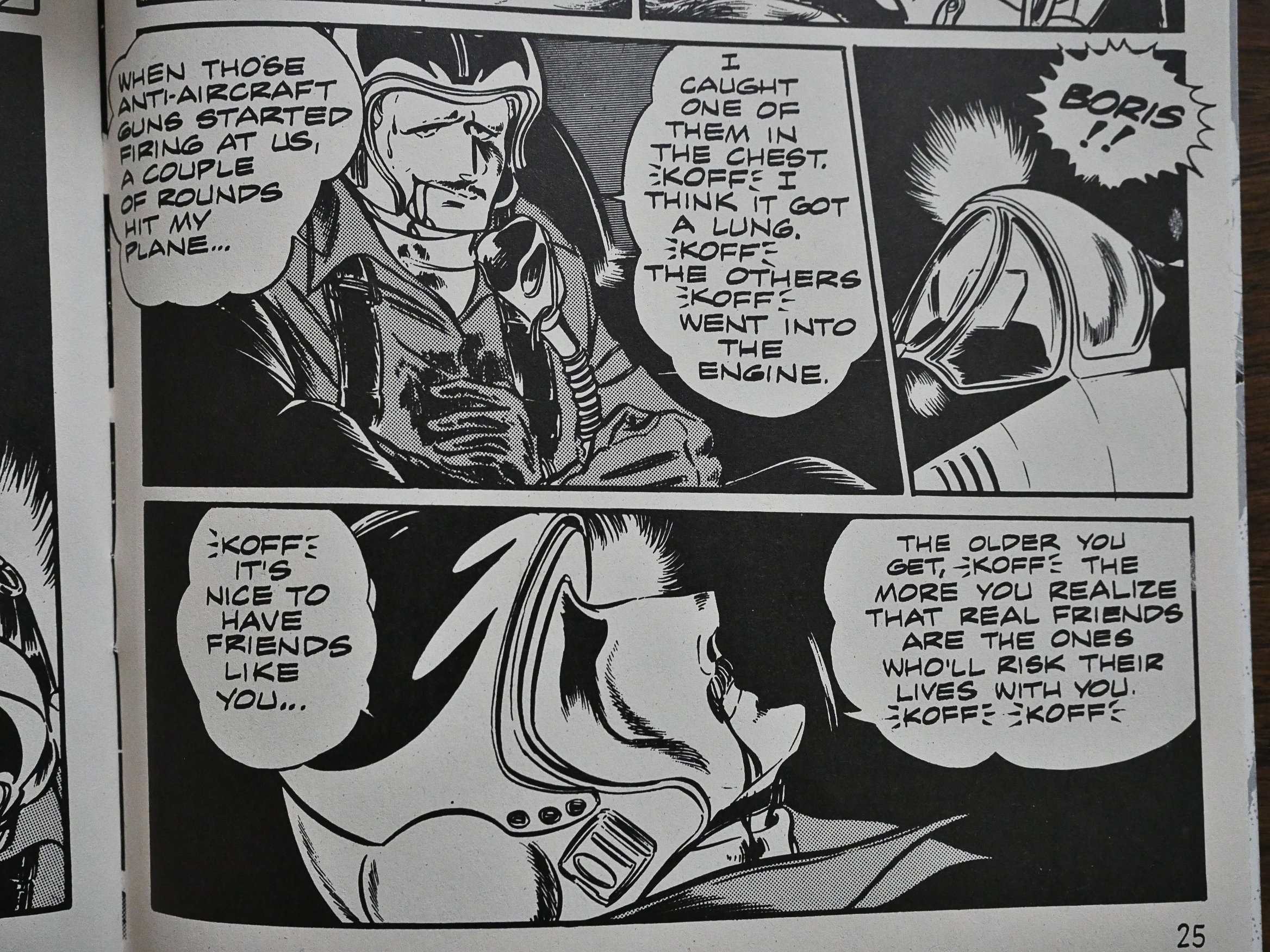

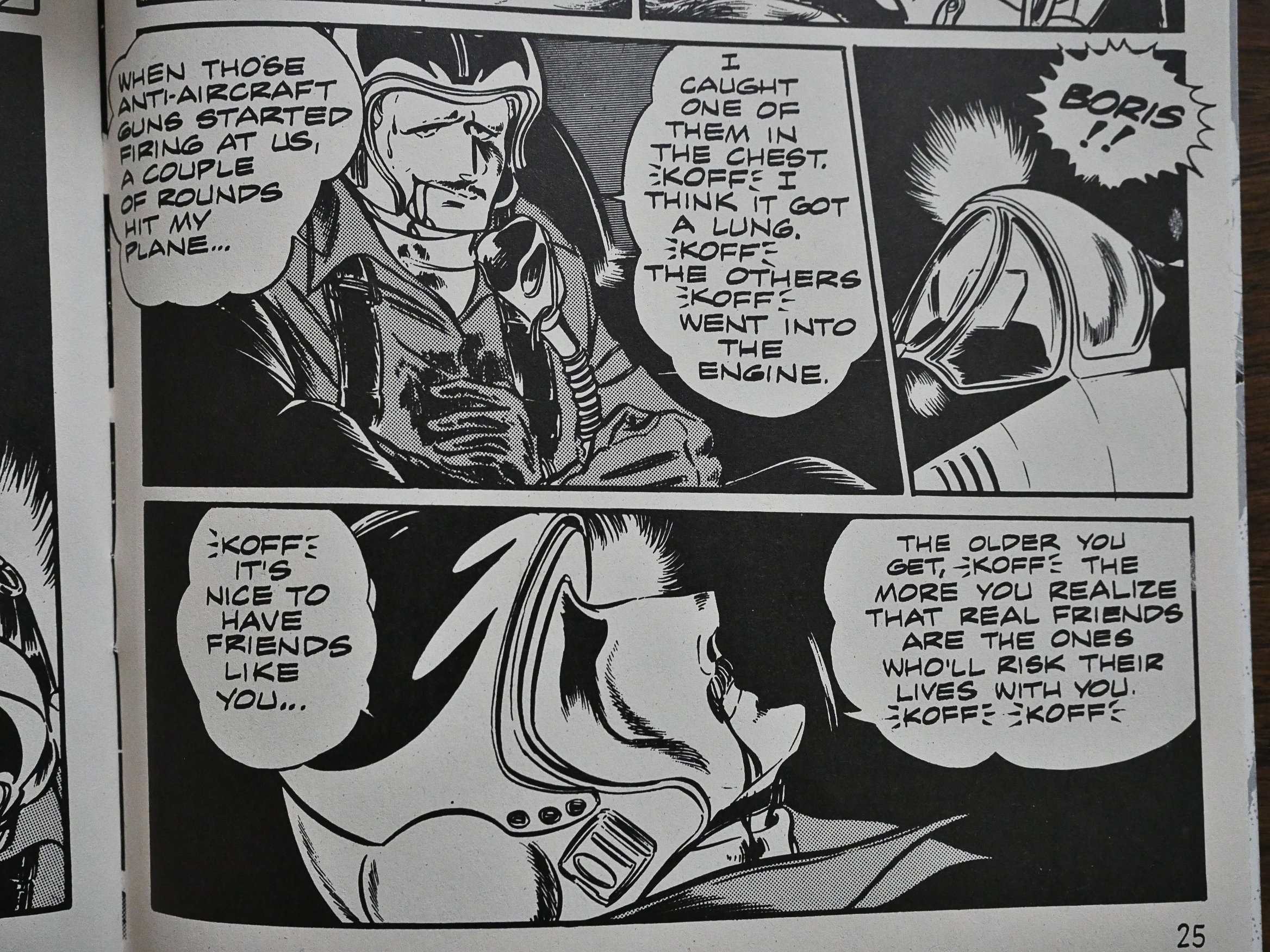

In the advertising copy for this book (and in the editorial pages), it’s stressed again and again how anti-war this book is. Which is kinda risible, because it makes the fighting look so cool. On the other hand, Kaoru Shintani favourite trick is to introduce a sympathetic new character, and then kill him off 18 pages later. War is hell!

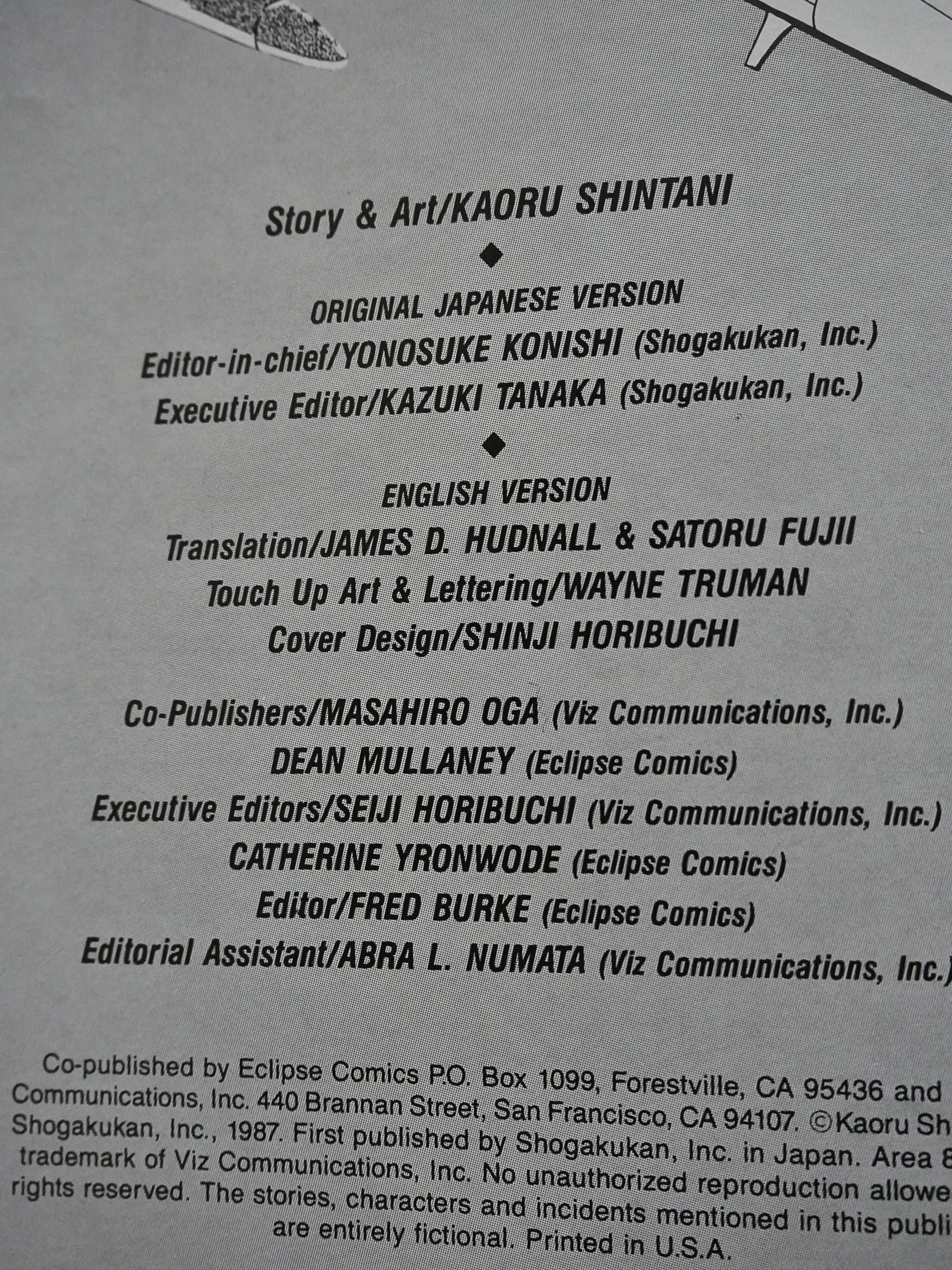

I wonder what the division of labour was between Viz and Eclipse. Did Viz do everything and just hand over camera-ready pages to Eclipse, or did Eclipse do the coordination with the translators and stuff? It’s never explained. If it’s the former, it’s more easy to understand why Eclipse would go all in, because it would then be no financial risk on their part at all. And they had a lot of empty schedule to fill after the black-and-white boom had gone bust a few months earlier.

I know you’re thinking: If this comic is just about pilots sitting in planes that SHEEEOH and RRREEE past, doesn’t that get boring? It would have, but these are thoughtful pilots, and while DOPYUTTing through the air, their minds would often slip back into the past and dwell on how they ended up as mercenaries in an airforce in a country that has lots of desert and is probably near Saudi-Arabia somewhere.

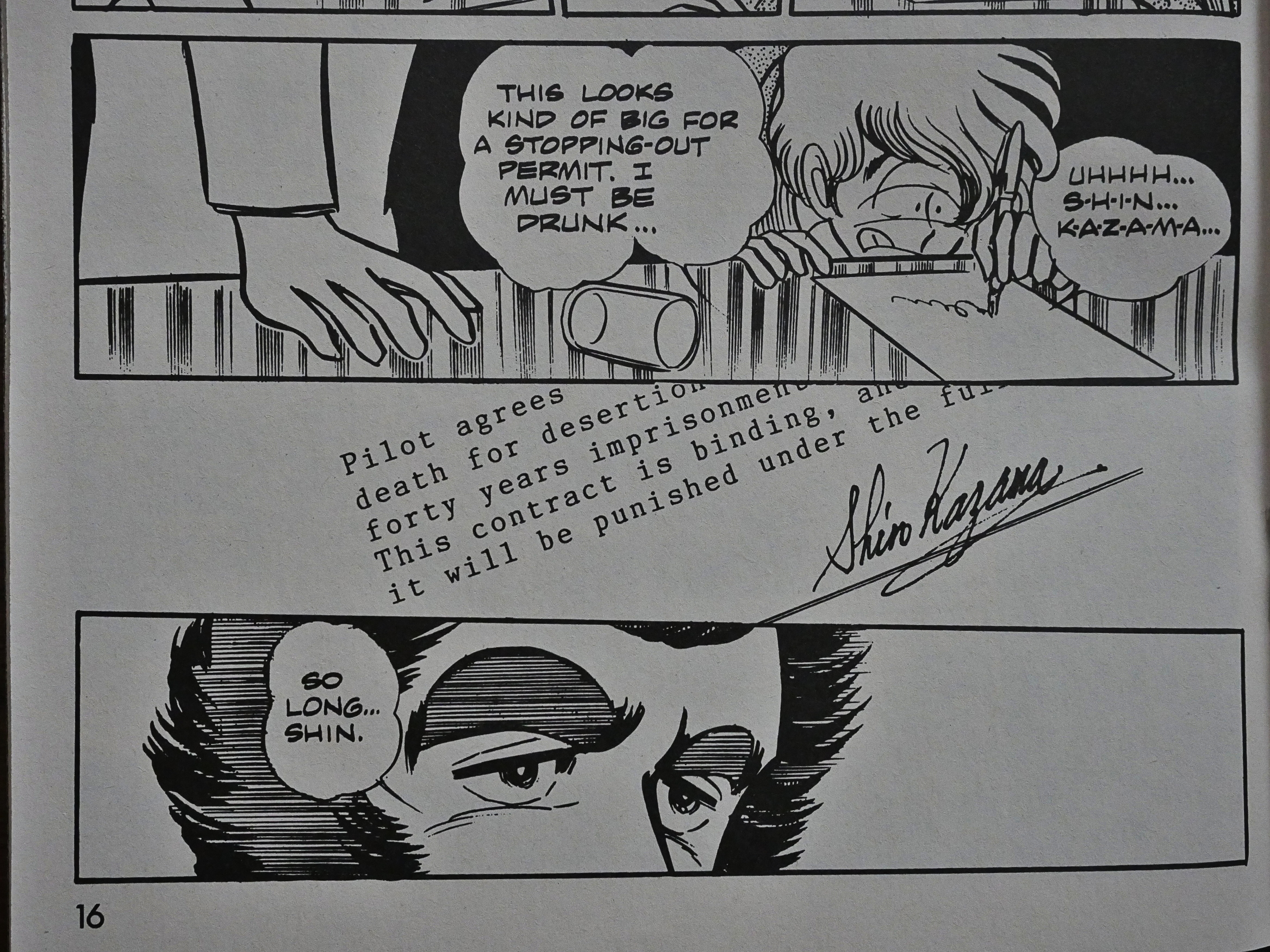

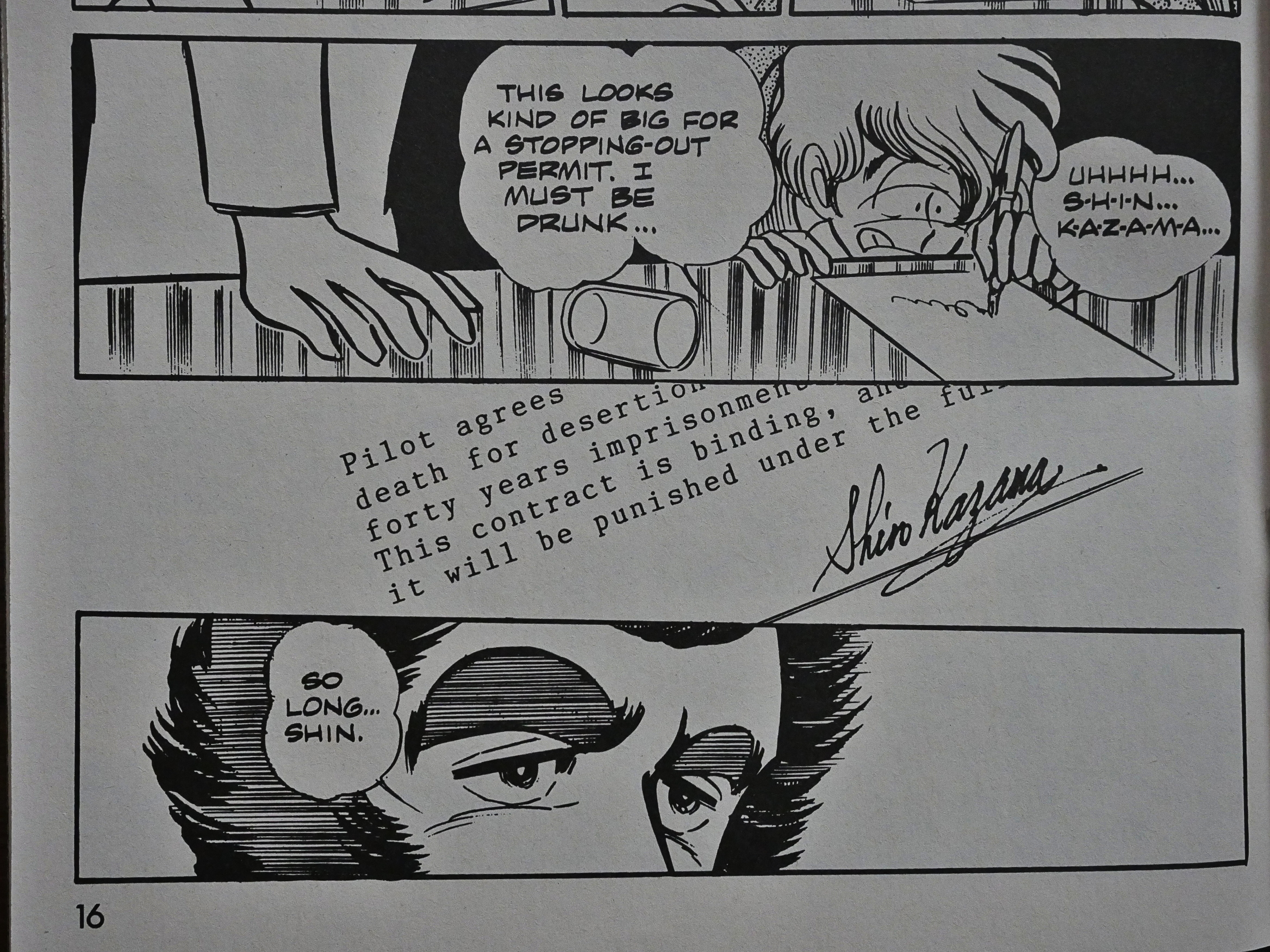

And it turns out that some of them have the Stupidest Origin Story Ever. Our hero, for instance, ended up in the troupe by being tricked to sign a document while drunk. That holds up legally in many jurisdictions I’m sure.

And the plots are mostly very stupid, but eh, whatever. I used to read European race car comics as a child (Michel Vaillant), and those weren’t… Hm… OK… Those were less stupid. But not a lot!

The trade dress of these books is almost completely separate from Eclipse’s wider line of comics: No editorials from cat ⊕ yronwode and virtually no house ads except for the other Viz books. And the design of the covers of these books is very distinct, which leads me to suspect even more that these books were mostly created by the hands of Viz.

Did I mention that Kaoru Shintani also did romance comics?

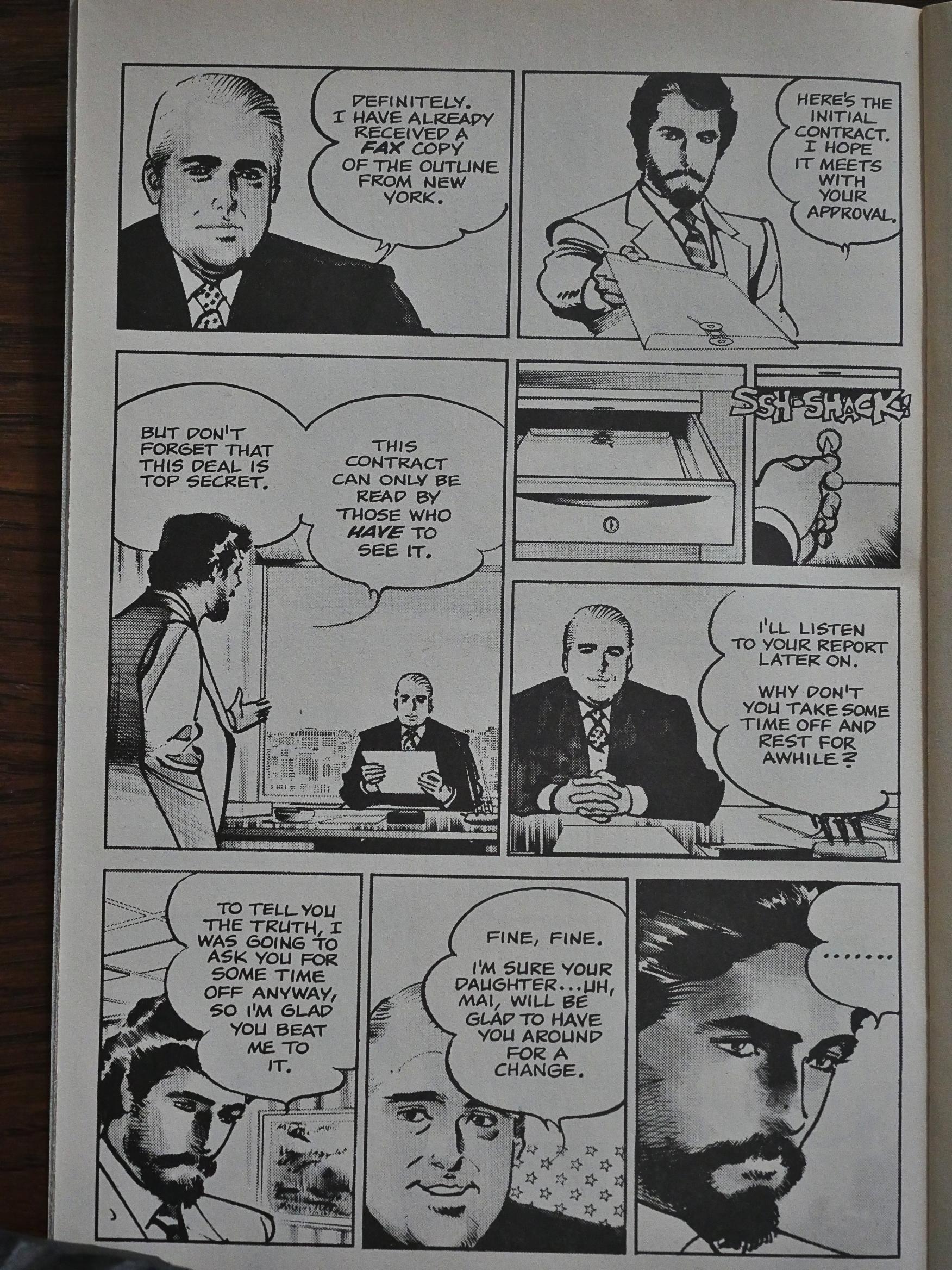

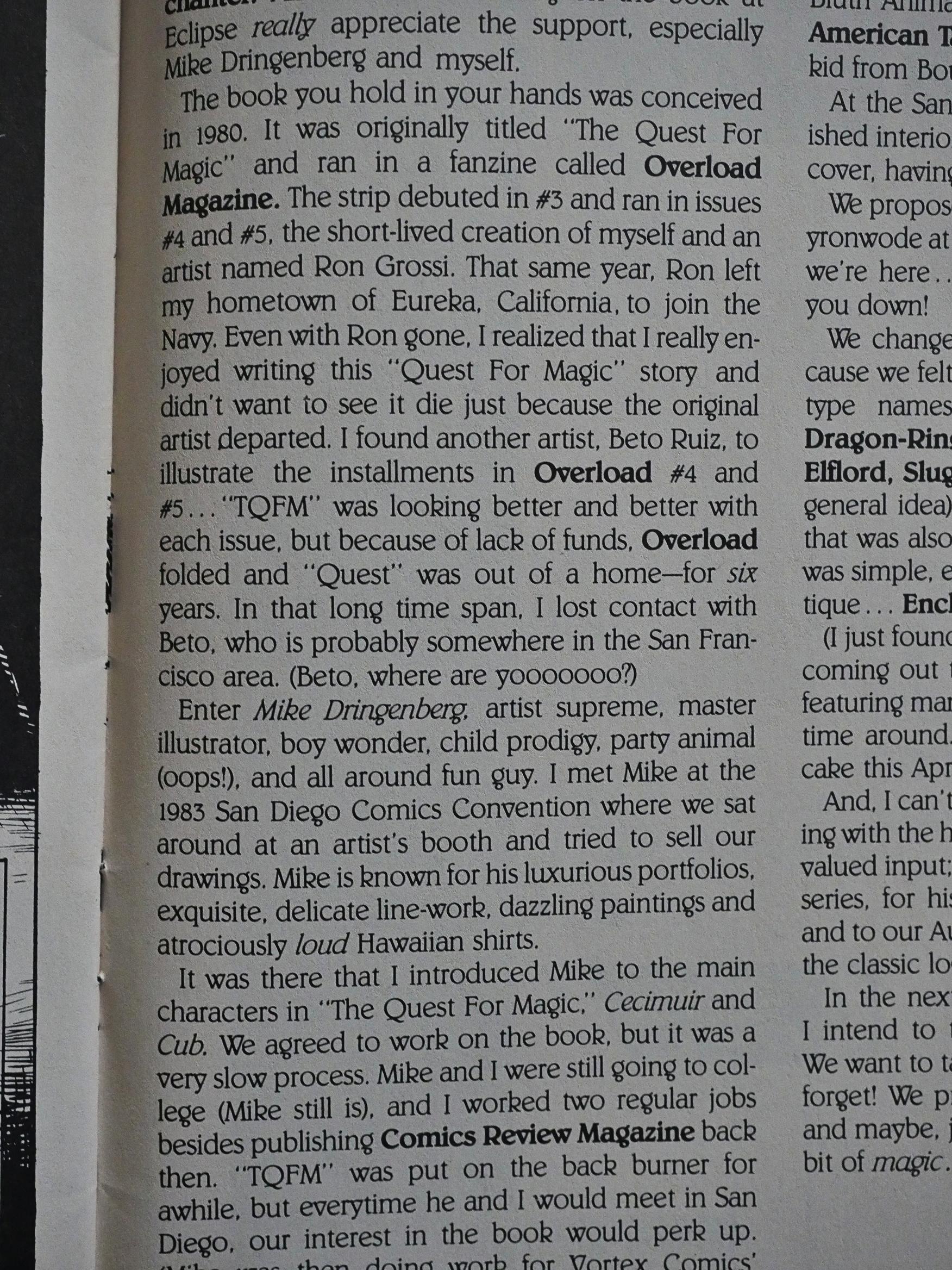

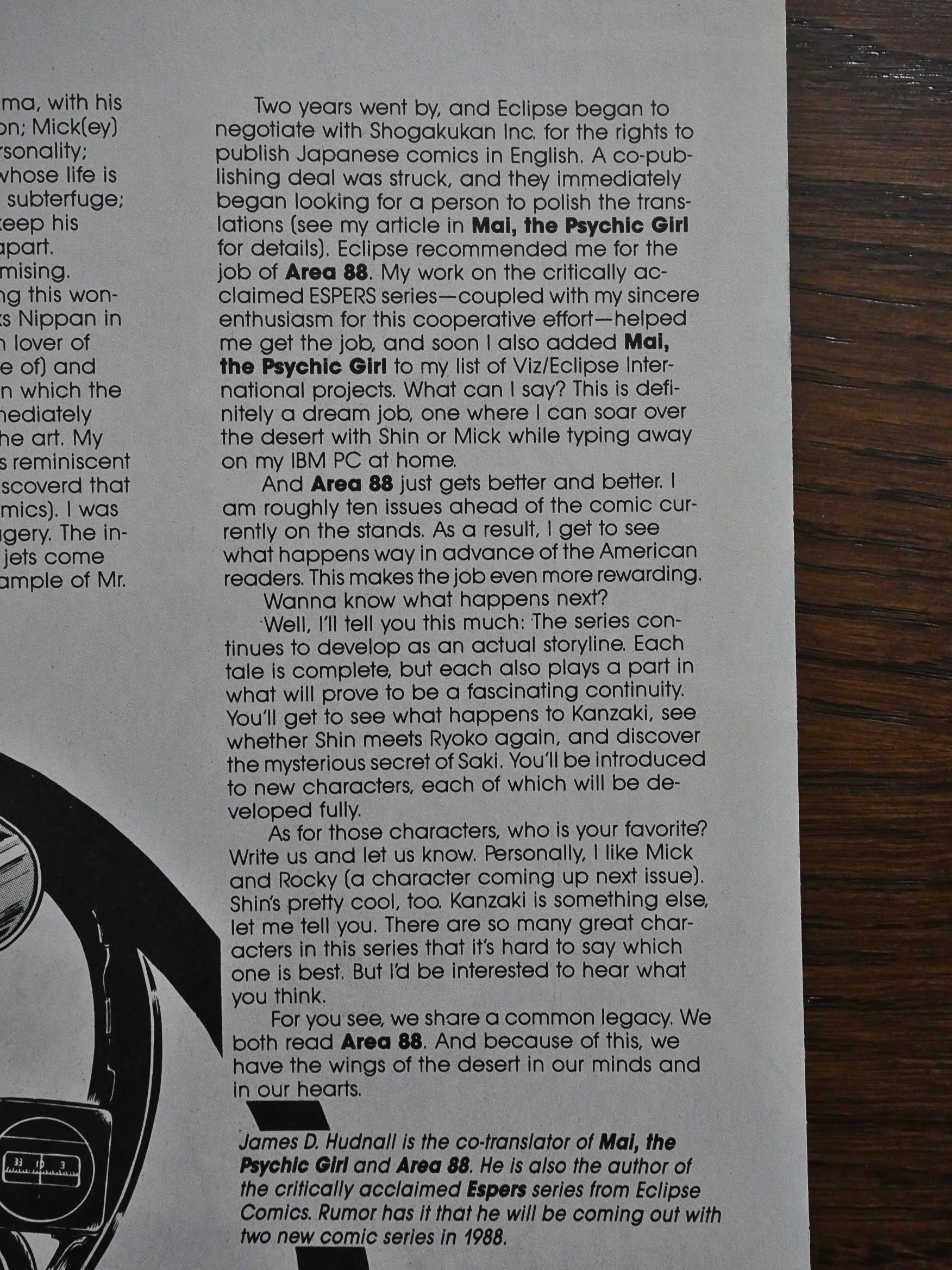

James D. Hudnall, creator of the critically acclaimed Espers (according to James D. Hudnall) writes about the translating process. First it’s translated non-idiomaticly to English by a Japanese person, and then Hudnall fixes up the English.

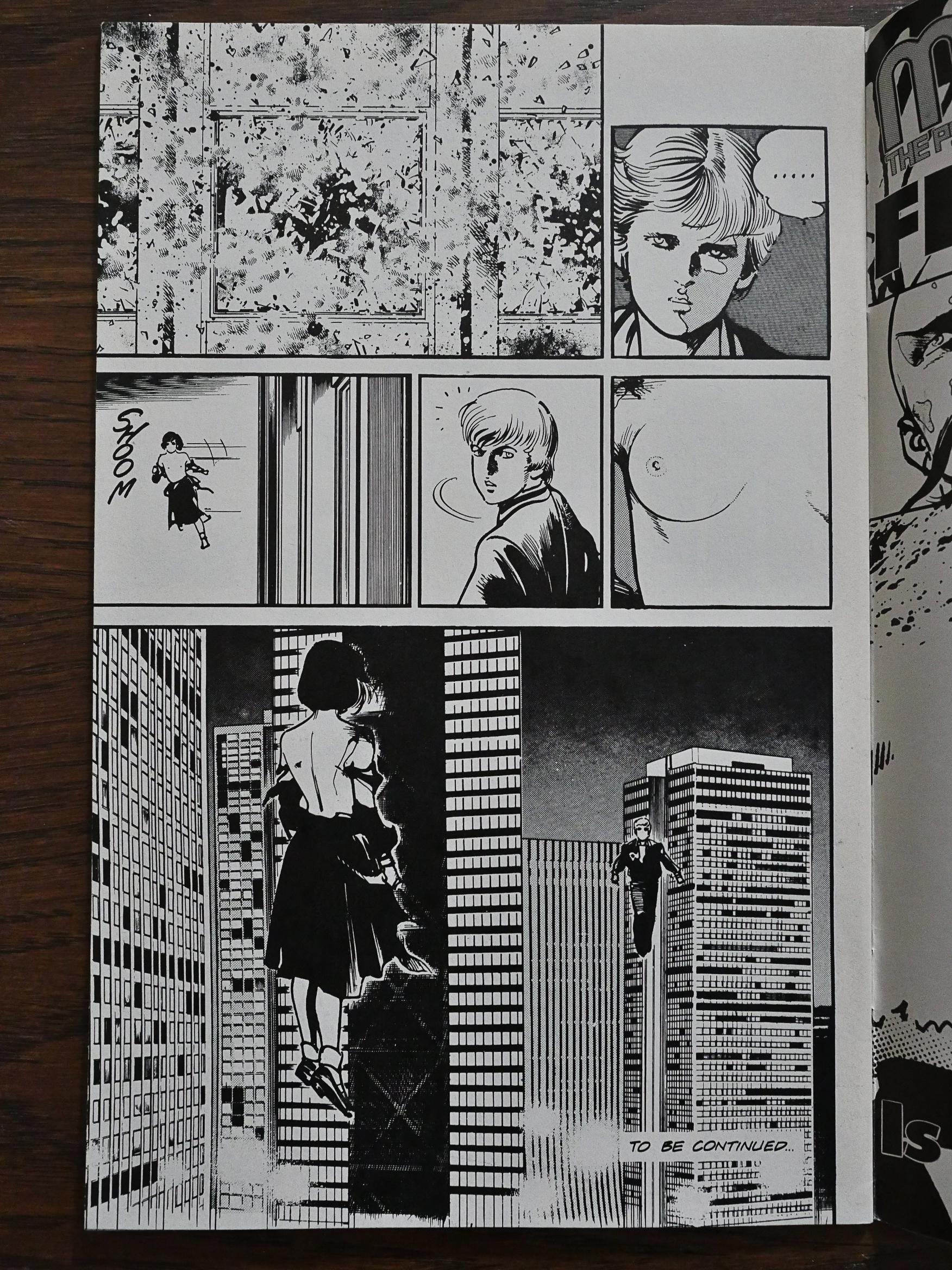

Kaoru Shintani’s studio may be adept at drawing airplanes, but when it comes to simple sequences where things happen, things can often get slightly confusing. In the scene above, the photographer removes a roll of film from his camera, twists of the heel of his boot to reveal a hidden room, and then slips the roll into that room. You know the approximate diameter of those rolls? He had boots with heels that high? In a war zone? Fashion forward choice!

And since this is a Japanese comic book, there’s always racism. The only black characters to appear in this series are those three, and they’re later revealed (in the same issue) to be scoundrels and are almost lynched. And are never seen again.

Did I mention the plot being stupid? Yes, Our Hero is $20K away from Freedom (out of a total of $1.5M), but does his very good friend offer to lend him that money, or does he sell his airplane (which is worth a lot) to bring in that $20K, or… does he wreck that plane later the same issue, bringing him 1M into the hole again? Take a guess!

I know, I know, it’s a children’s book, and I don’t find this that annoying. It’s fine. But with a little more care, this could have been a more exciting book. Because it’s a fun read, but you have to just go “OK then!” every other issue.

OK then!

And we learn a lot of interesting facts, like how all Swiss people were mercenaries during World War II, and were all killed.

*gulp* There’s allegedly enough material to keep the series going for 240 issues.

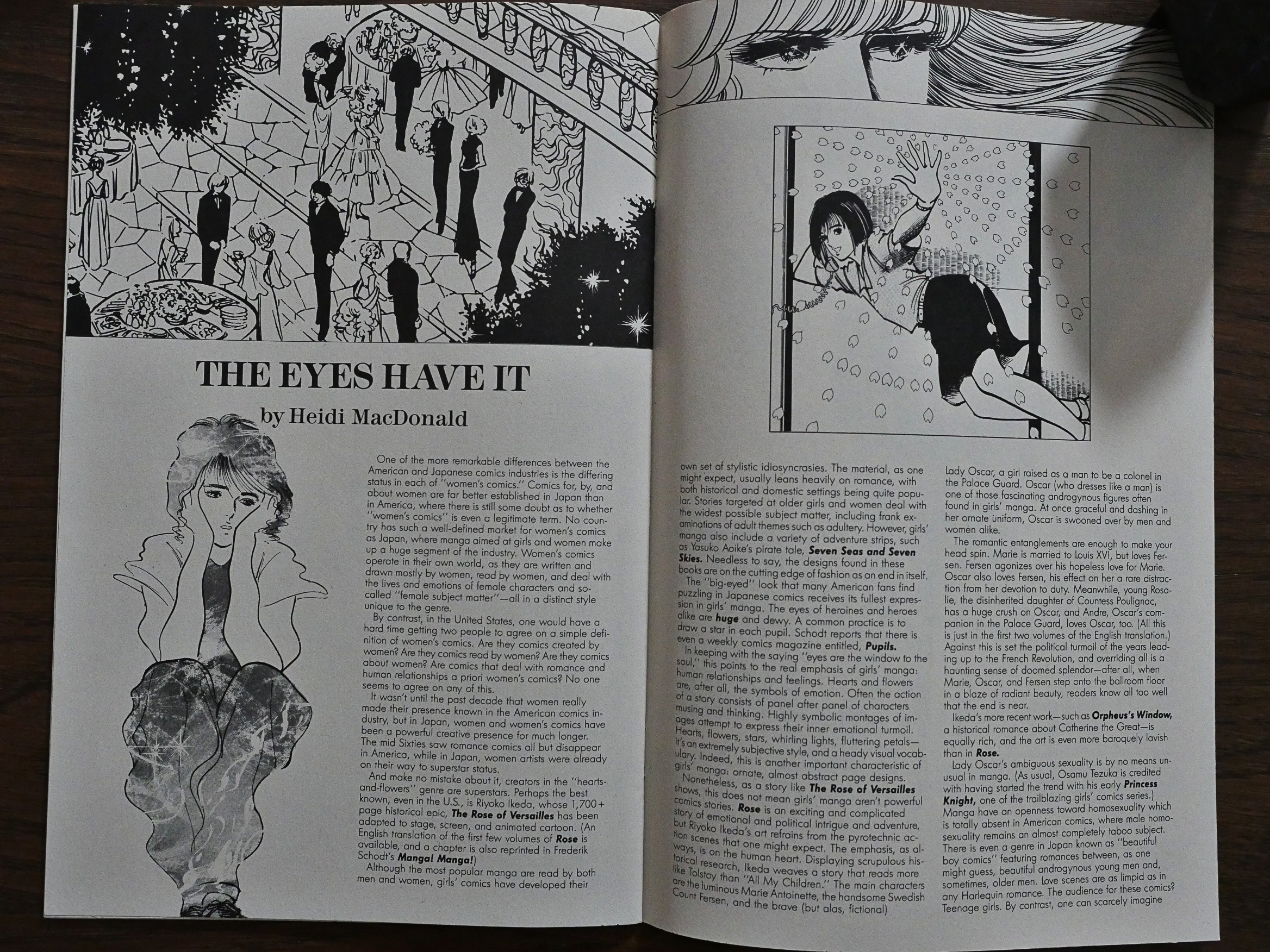

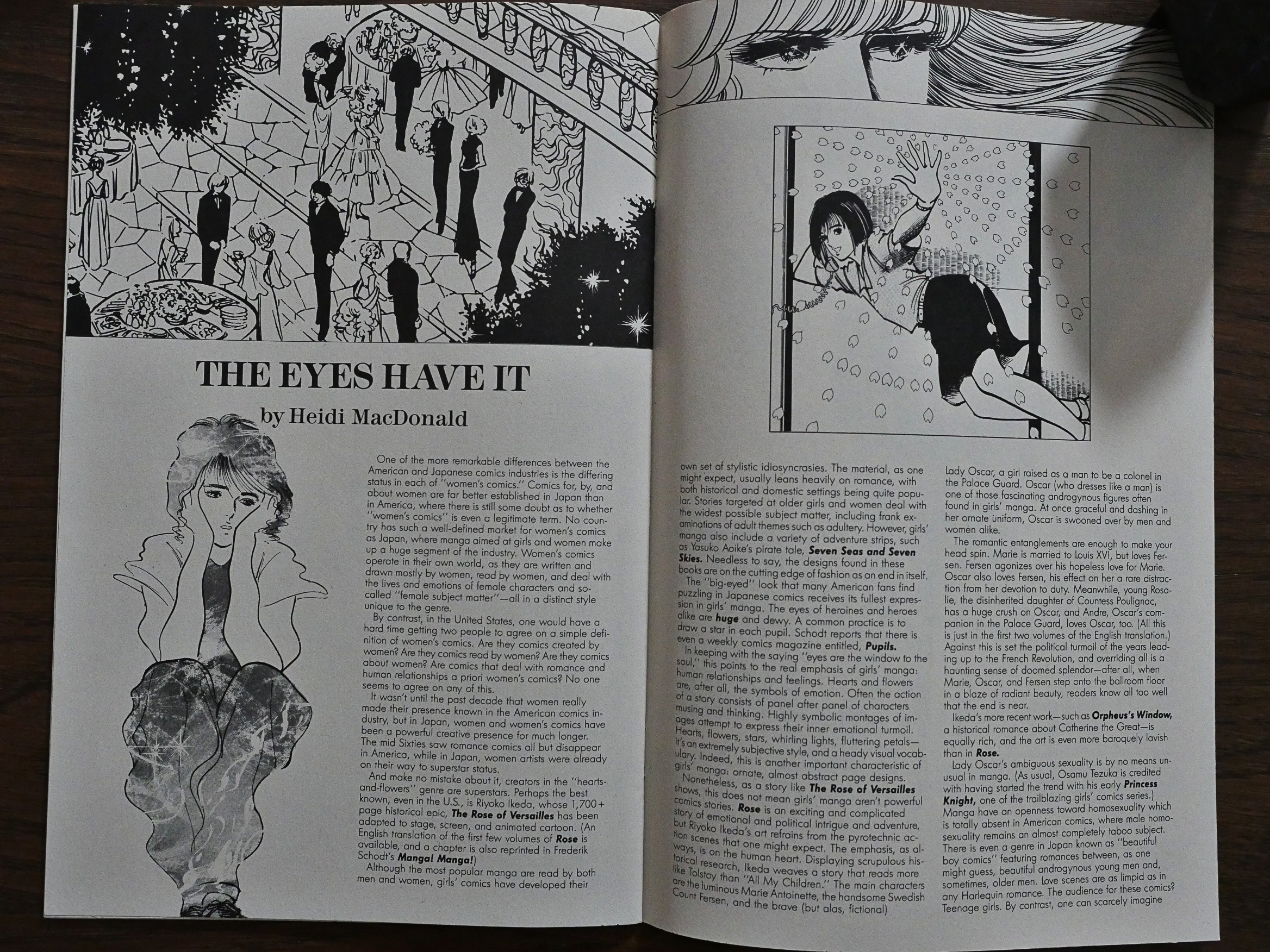

The chapters are of uneven length. Some are 32 pages and take up the entire issue (and I wonder whether they lopped off some pages if the chapters were too long), but most are around the 28 page mark. Which leaves room for text features, and most of them are about Japan and Japanese comics. Heidi MacDonald provides and overview of comics mostly marketed towards girls.

Some non-Viz Eclipse house ads sneak in, like this for Real War Stories. I wonder whether Eclipse snuck that in just to fuck with Viz, because Area 88 isn’t very real as war stories go.

The back covers are also very un-Eclipse: They’re all like this, with just a single little image dropped into a flat-coloured space. It’s nice.

As the series progresses, we get more and more plot happening off-base. There’s intrigue and plotting, but most of all, there’s accidents. Every thing that drives the plot forward happens because of the main characters happening to meet each other. It’s very lazy.

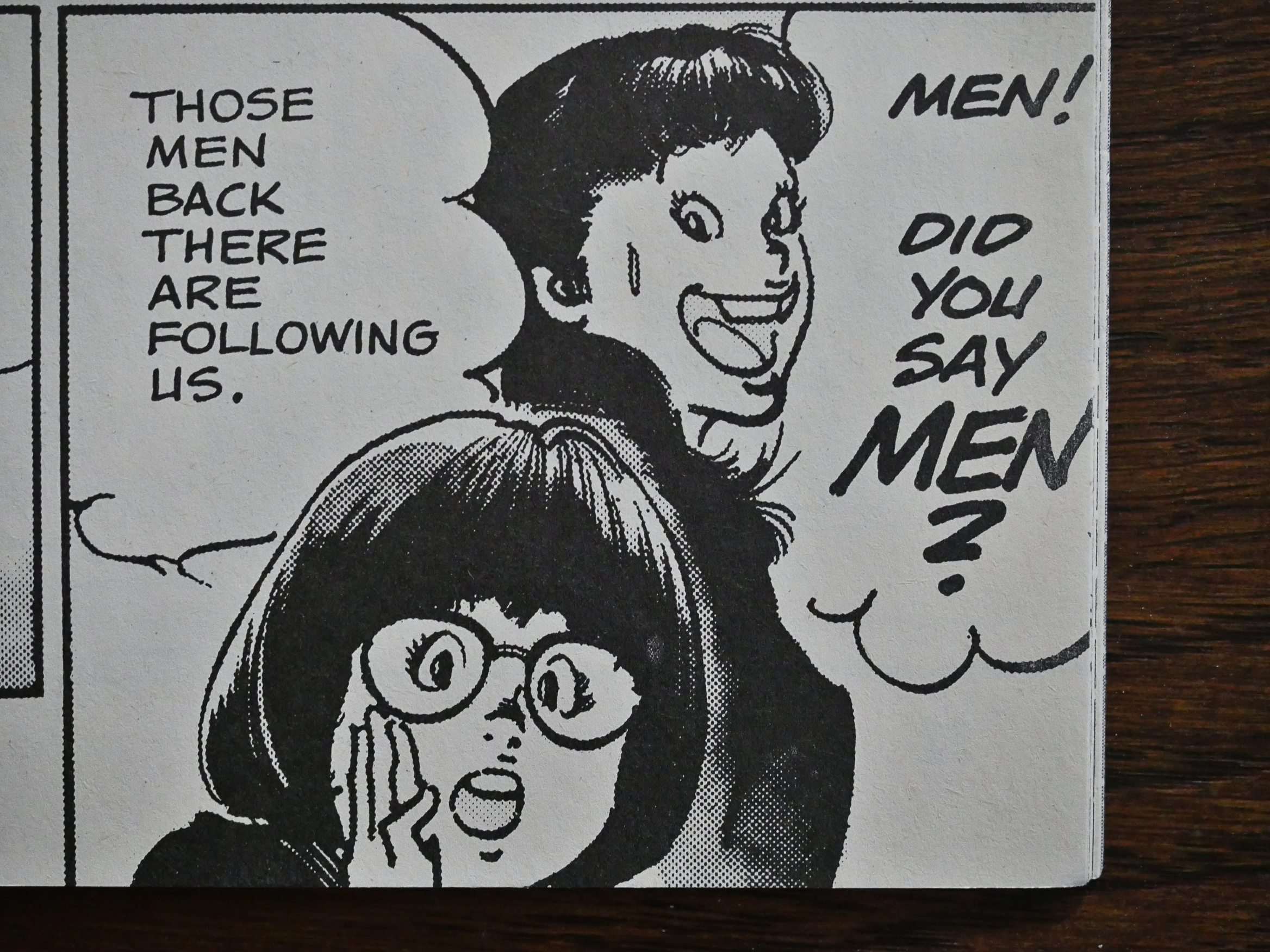

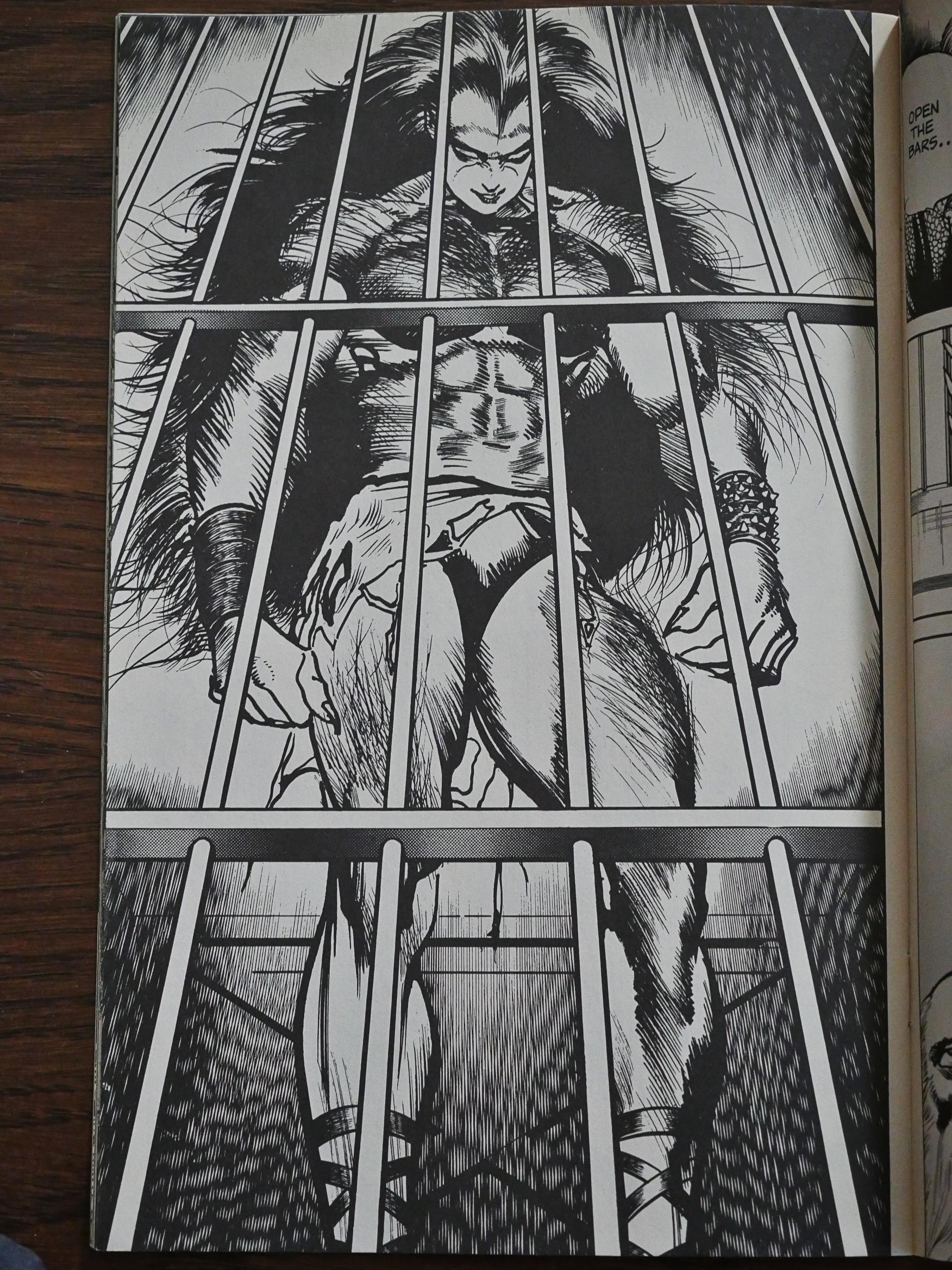

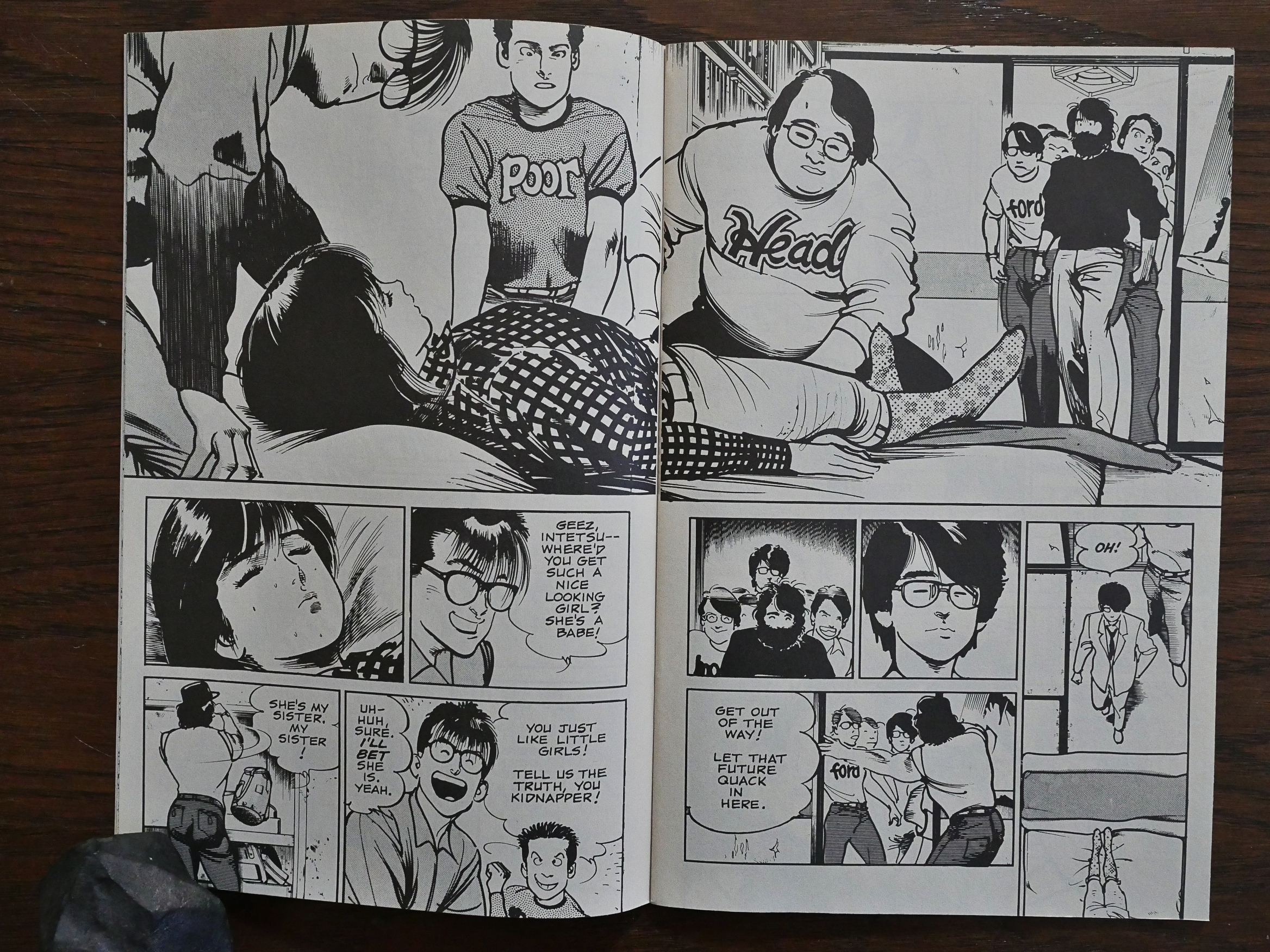

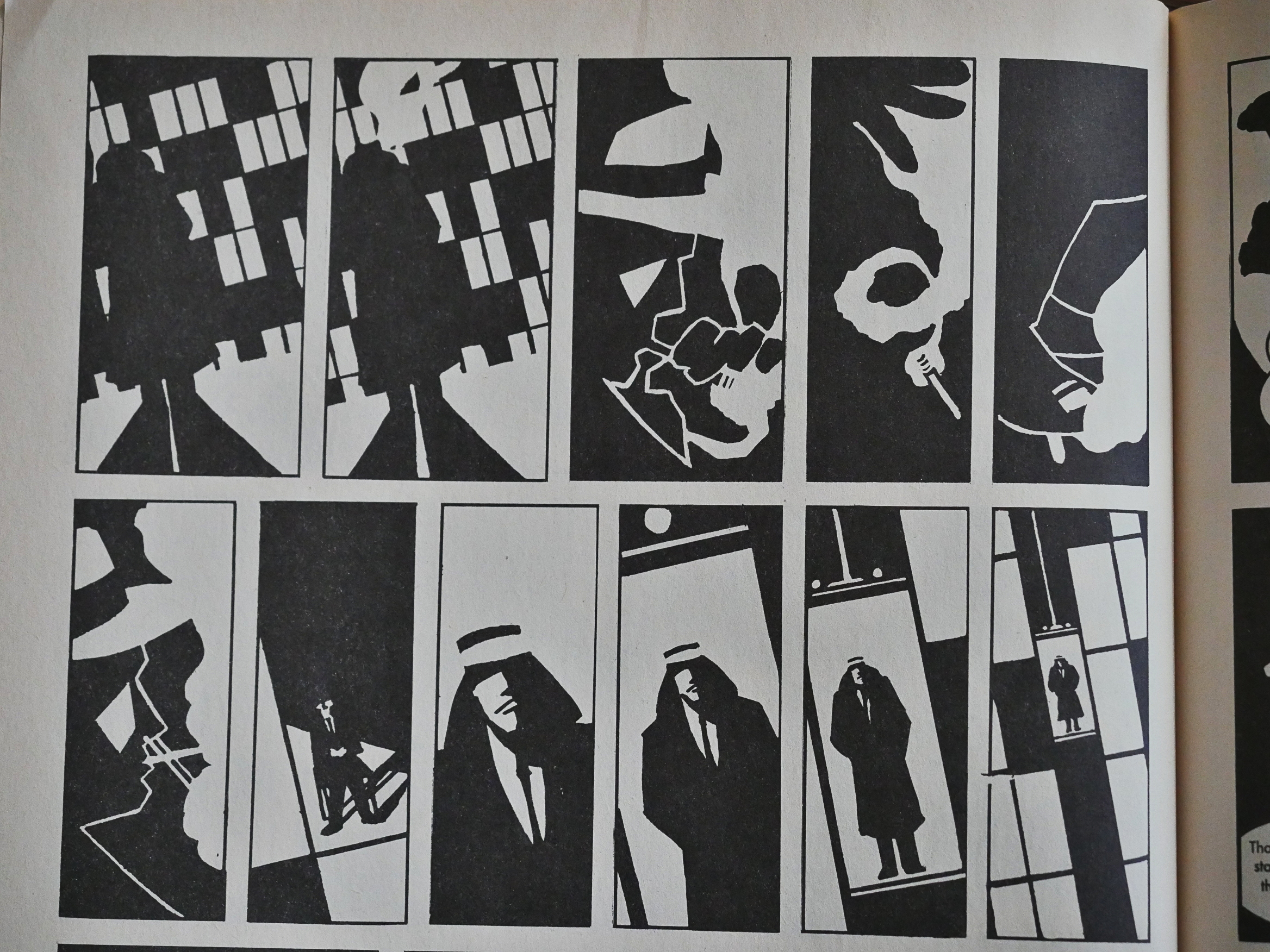

While the planes look very realistic, Kaoru Shintani (et al.) draws the male character’s faces in a very cartoonish manner. Each character has at least one defining er deformity, and I love it, because it makes it possible to tell them apart. Like here’s one with a huge nose…

… and here’s one with no nose. Faces in Japanese comics are often drawn identically from character to character, which means that the only way to differentiate them is to look at the hairstyles. Kaoru Shintani isn’t of that school, which is great.

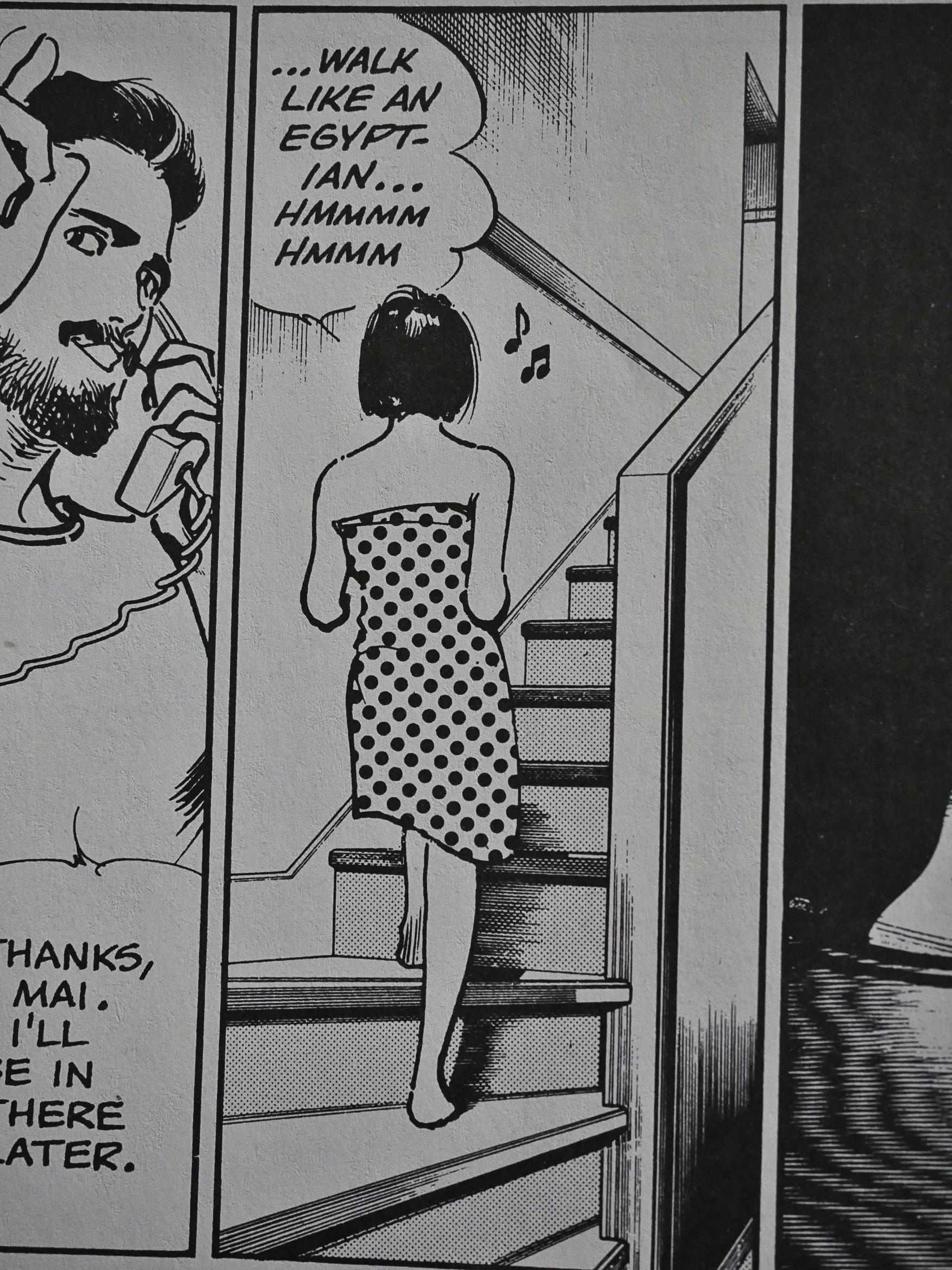

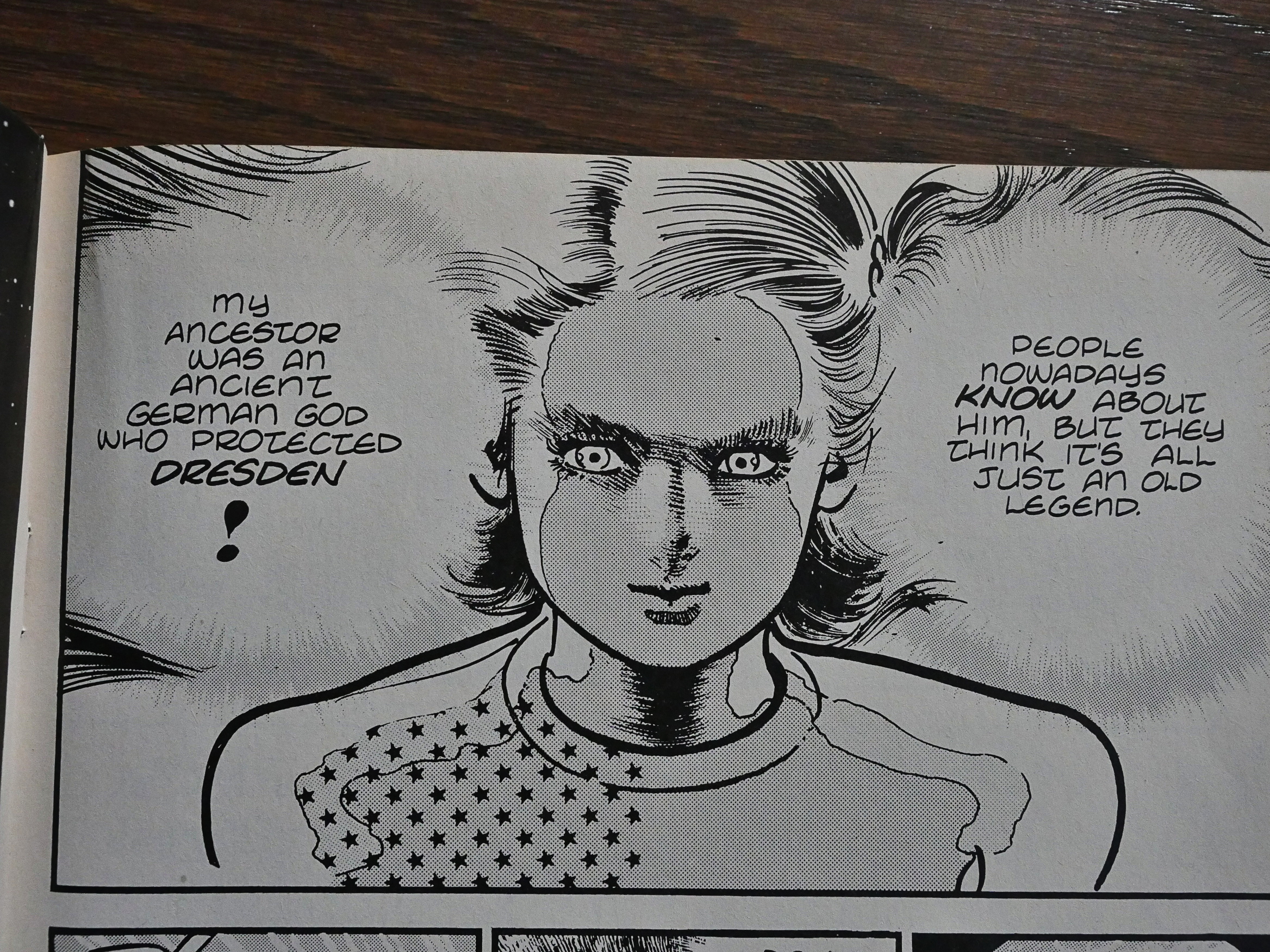

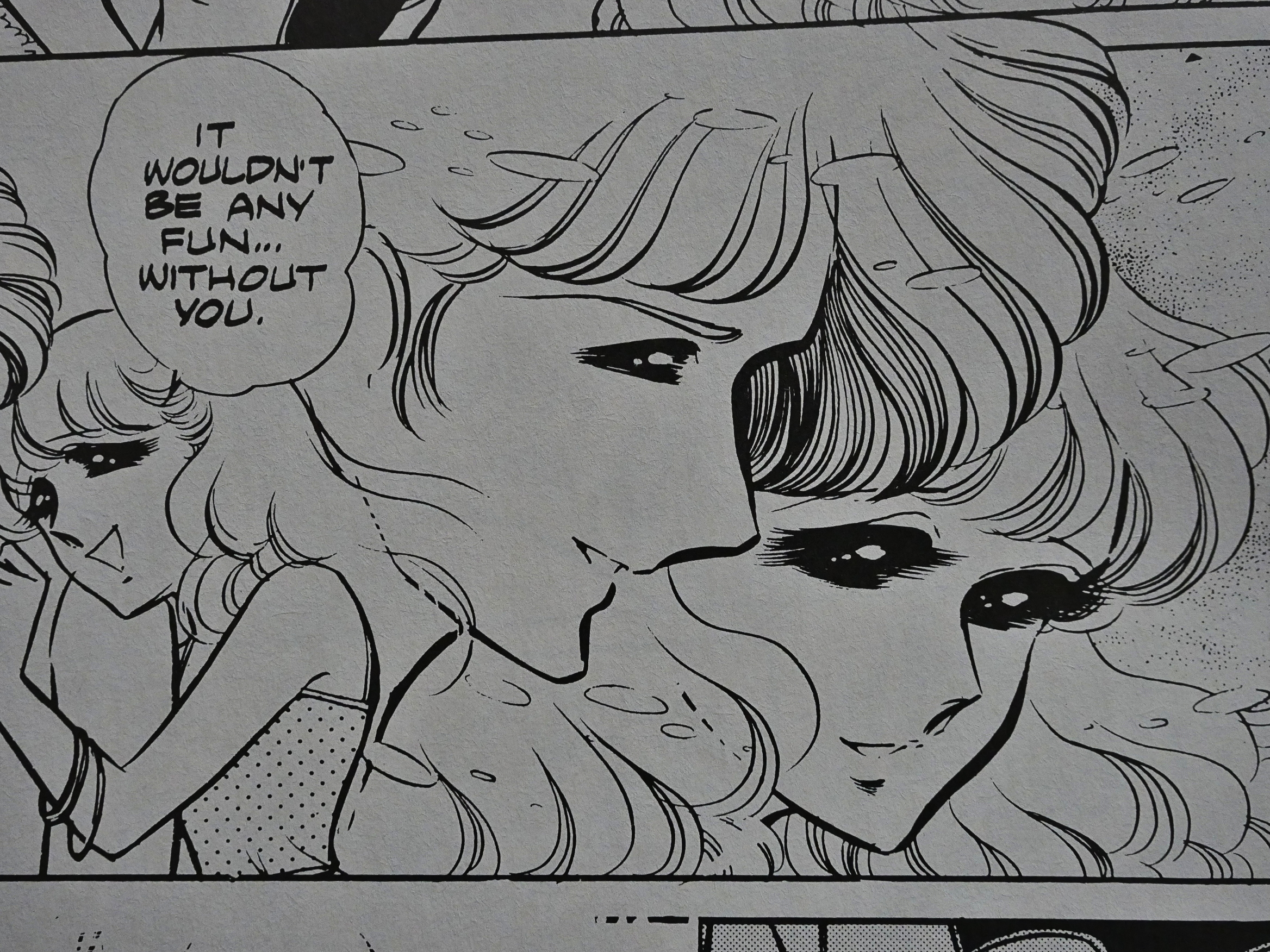

But then there’s the female characters. They’re all pretty, so they’re all drawn with the same features, so you’re back to the “well, she’s got slightly curlier hair… so that must be Ryoko up to the right”.

In one of the text pages we learn that Kaoru Shintani ran a horrifying hell-camp of a sweatshop studio where they cranked out almost six pages per day. (They didn’t phrase it quite that way.)

The Viz editorial staff sure know a lot about planes, so we get a handful of these pages with All The Facts.

Speaking of male faces… is that fish-lip guy supposed to be a reference to anything?

The leader of “namely, the anti-government forces!” presents himself. Like all rebel groups, they don’t bother coming up with a name for themselves.

Pin-ups!

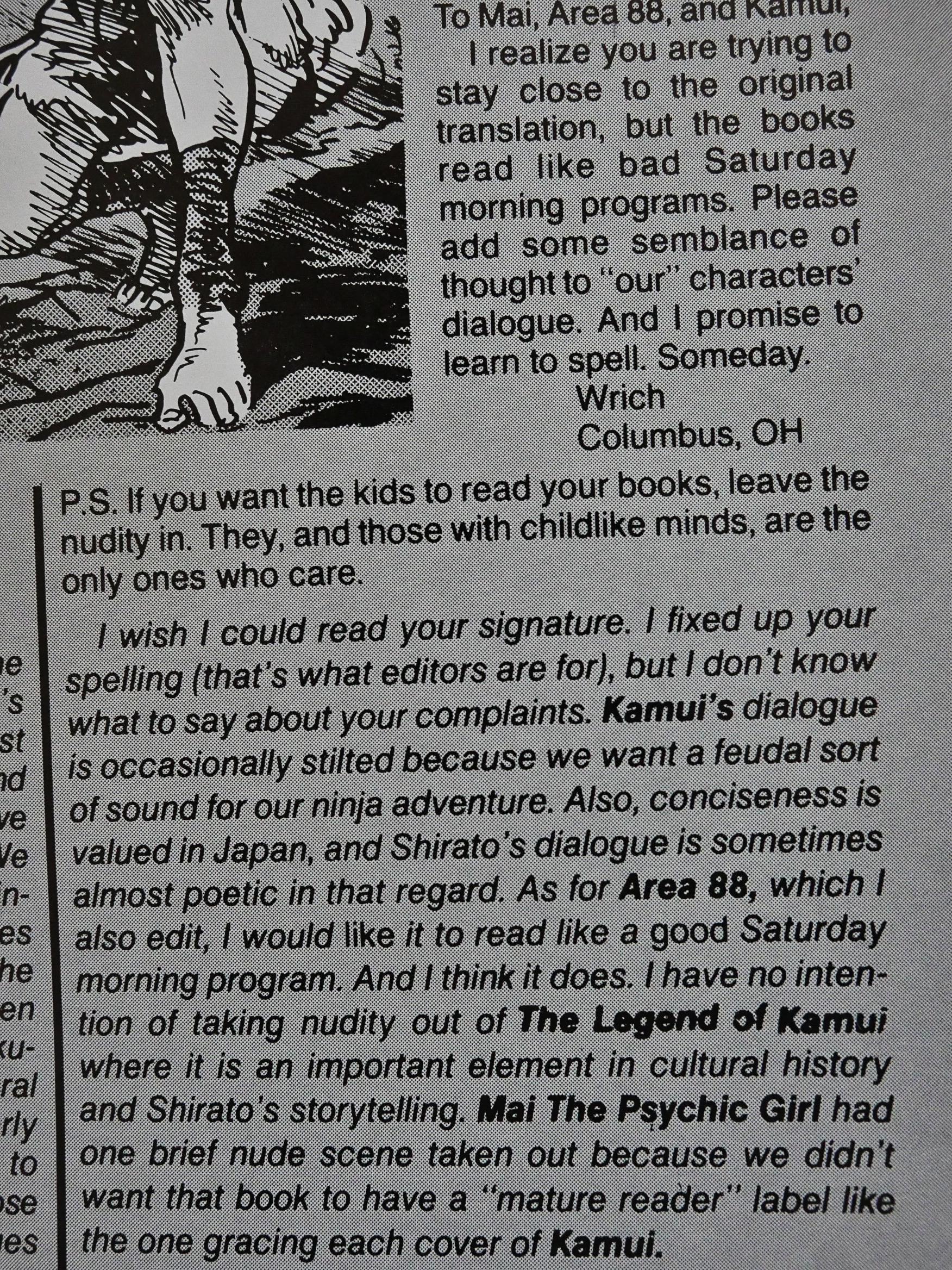

Editor Fred Burke starts off every letters column with a little paragraph about his life. It’s nice.

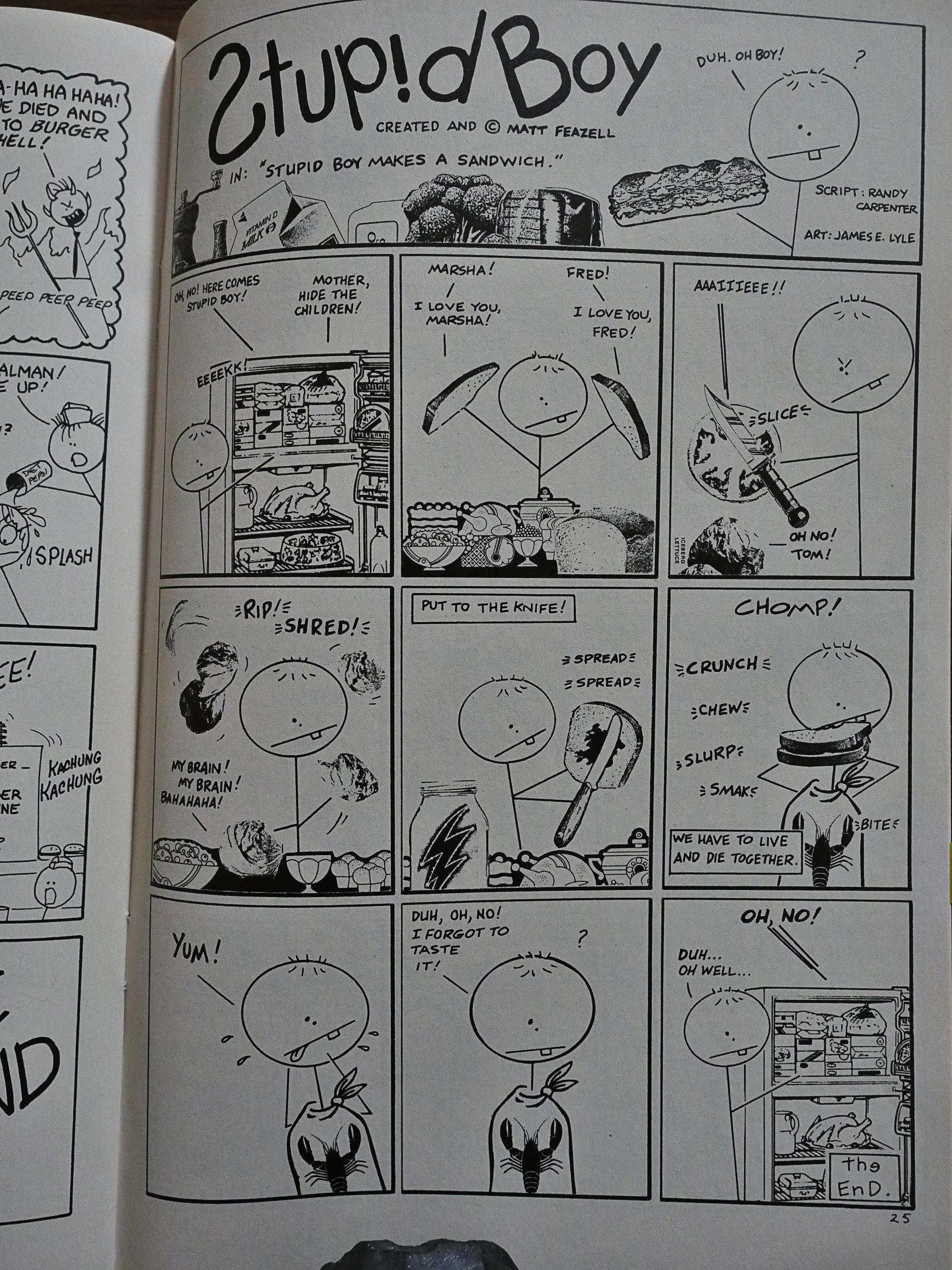

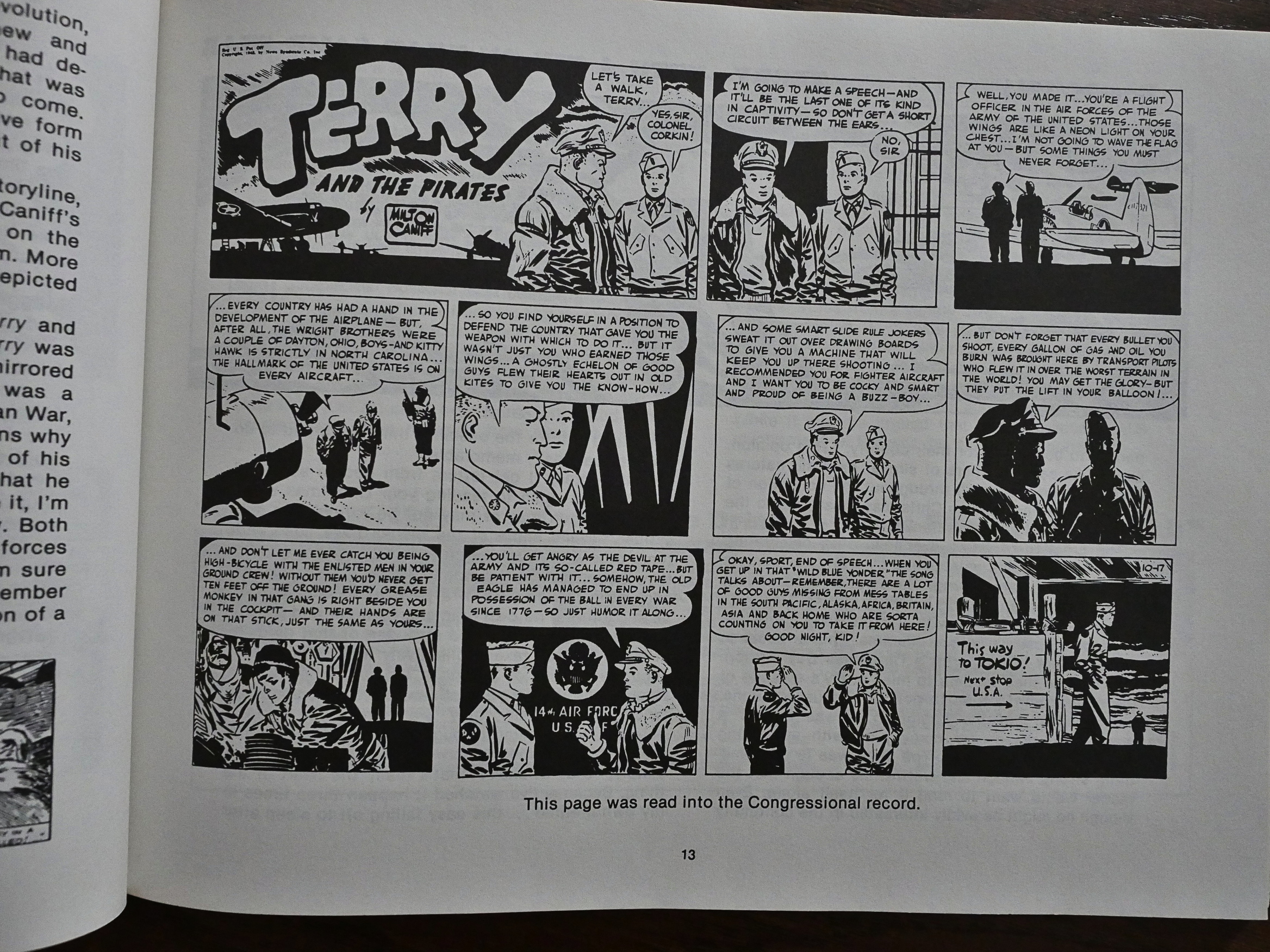

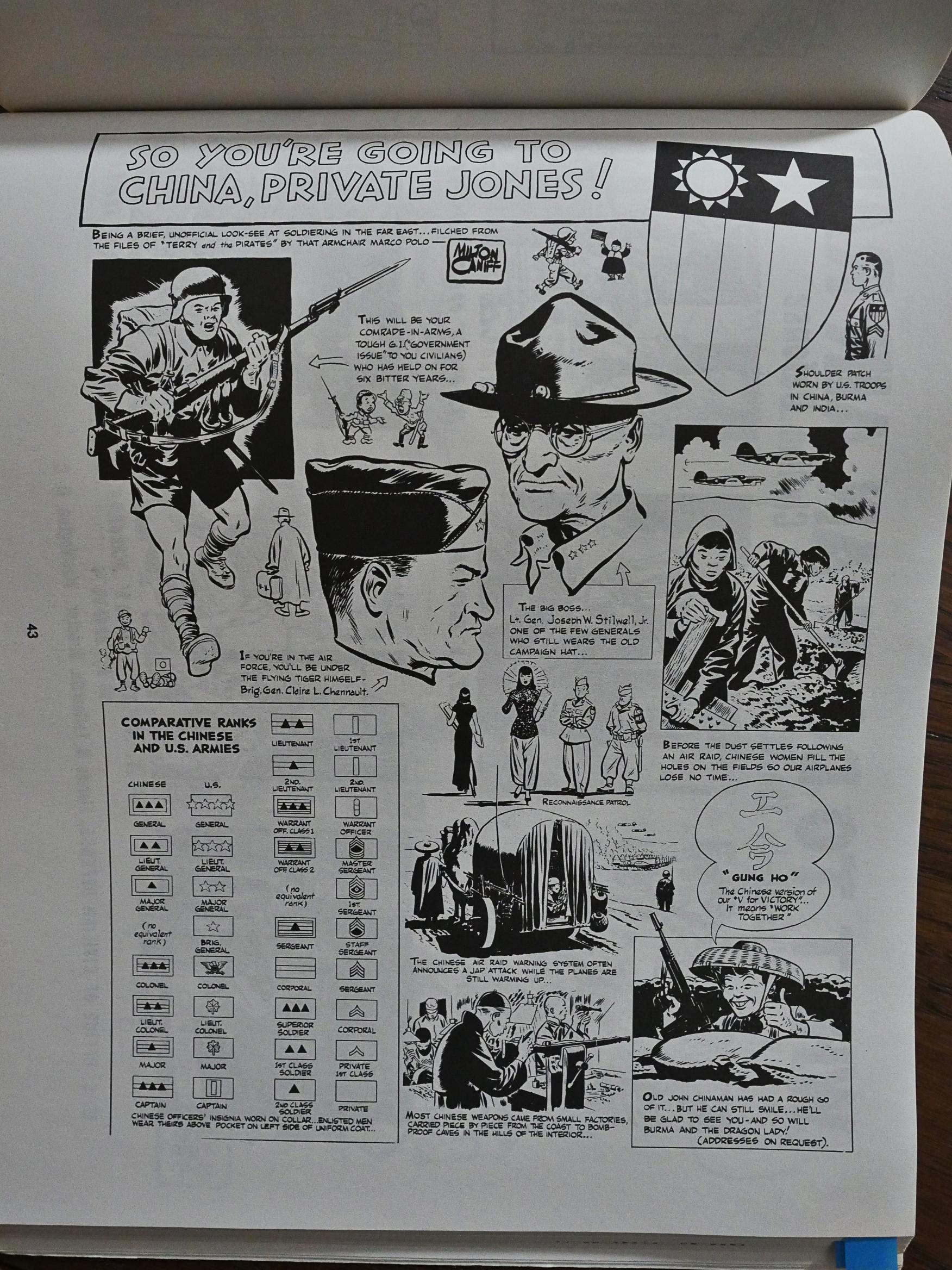

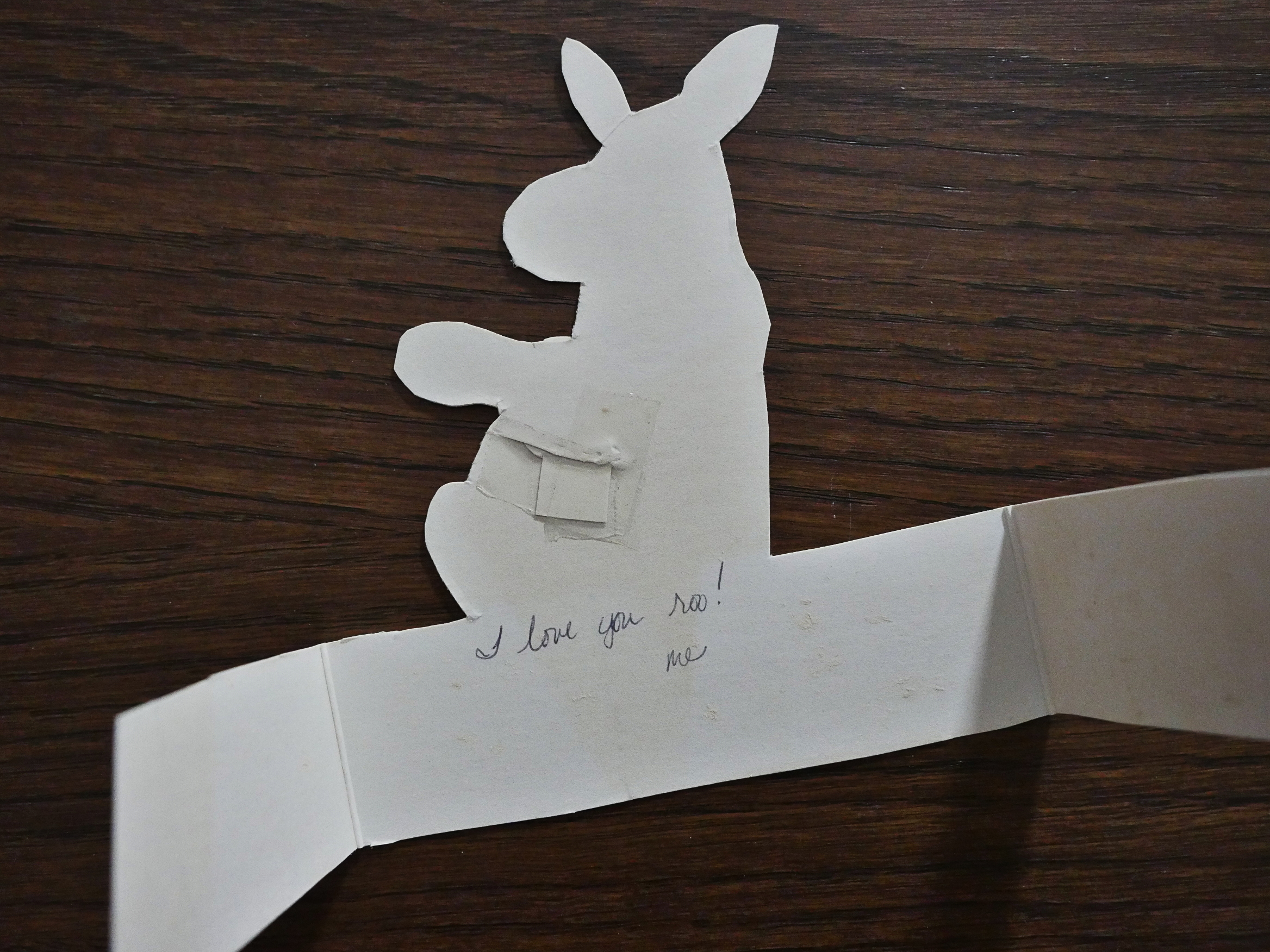

Whaa… I bought these comics used, and in one of them I found this newspaper comic strip that somebody had cut out. And used as a bookmark? Or had it just gotten wedged into this book?

The plot gets strangely convoluted after a while, even as it seems that nothing much is happening. It’s a strange trick: It feels like the conspiracies proceed at a snail’s pace, but it actually builds up and gets quite interesting after a while.

Hm… is that hair curly enough for that to be Ryoko? No… Must be somebody else!

And then it’s announced that Viz would take the book and leave Eclipse. Whaa?

One the one hand, the book isn’t well constructed. Whenever somebody needs to find something out, they’ll just stumble over the conspirators while being in an airport lounge in Rome. On the other hand, that panel up there is the pay-off for a sequence thirty issues ago, so perhaps somebody at the studio were taking notes and has a plan.

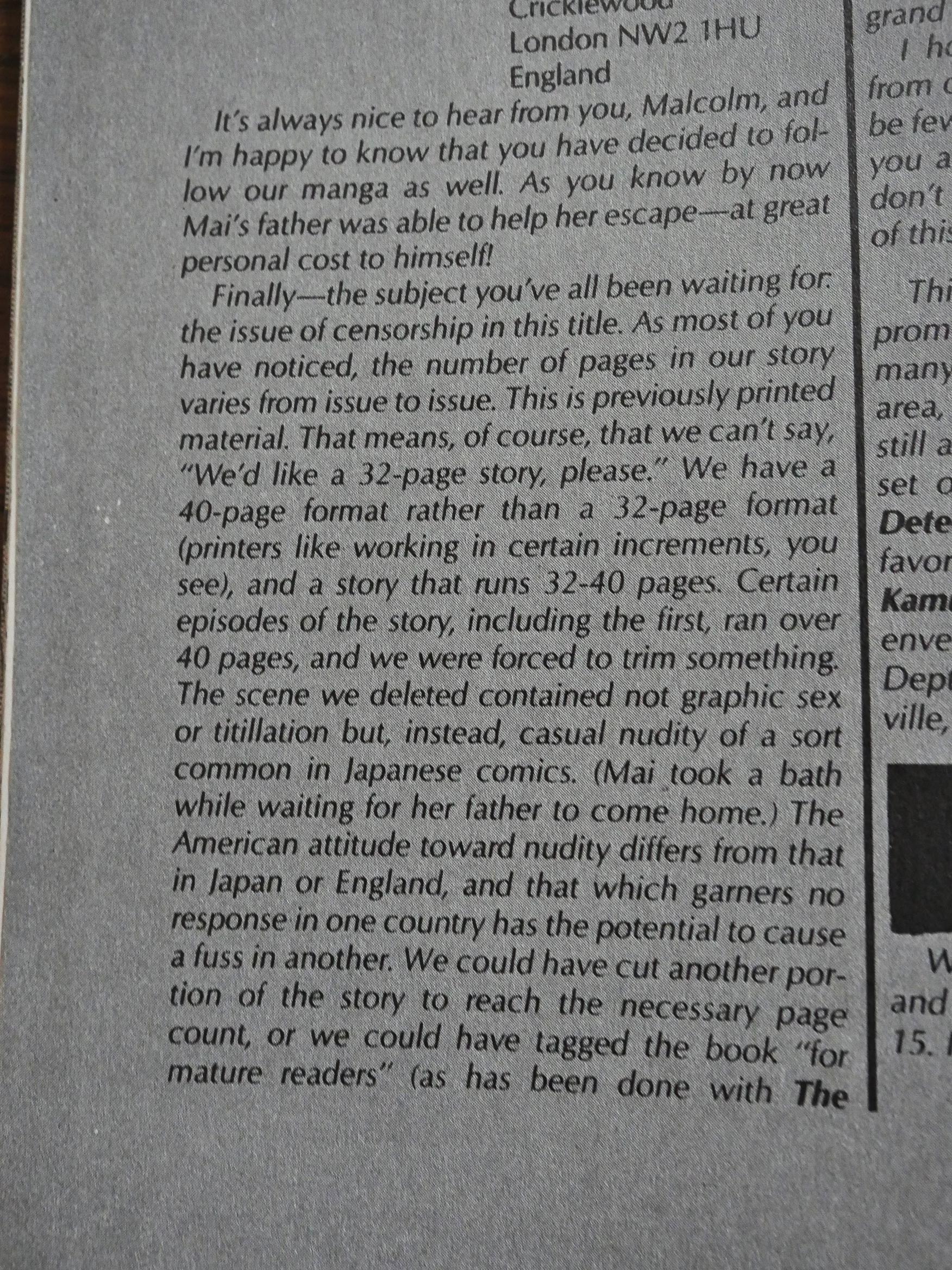

A reader writes in and asks what’s up with all the racism in these Japanese comics, and the editor explains that they considered just erasing the black characters, but decided against it. And apparently hopes that the influence from America in Japan will make Japan less racist. Yes. I think that’s what he’s saying?

So after 36 bi-monthly issues the book moves to Viz.

The printing quality takes a nosedive. The Eclipse issues were very crisp and nice, but here the finer lines are eradicated, and everything gets a wispy look.

And we get pictures of planes on the covers instead of drawings. Mostly because they’d ran out of colour drawings by Kaoru Shintani.

I take it back about the note-taking: He’s saying here that they’d never use nukes in the war, but we saw in an early issue that they did use a nuke and tried to use another one.

Huh. On this subscription form, they’re only announcing the book up till #42, and that’s how many they published. Why yank it from Eclipse just to cancel it a couple of months later? It’s weird.

And… Aaargh! I forgot to buy the last three Viz issues, so I don’t know whether they tied anything up, but it seems unlikely. There are 200 more potential issues to be published, remember? So I’m assuming it didn’t end very satisfactorily.

And weirdly enough, even after the Manga boom, Area 88 has never been printed in the US again. And googling a bit shows that it was released in 23 paperback volumes in Japan.

It’s so odd. The series they picked as the first one to be published in the US has never been translated to completion.

On the other hand, I can certainly see why it’s not as popular as One Piece, which… has fewer long scenes of jet planes shooting at each other.

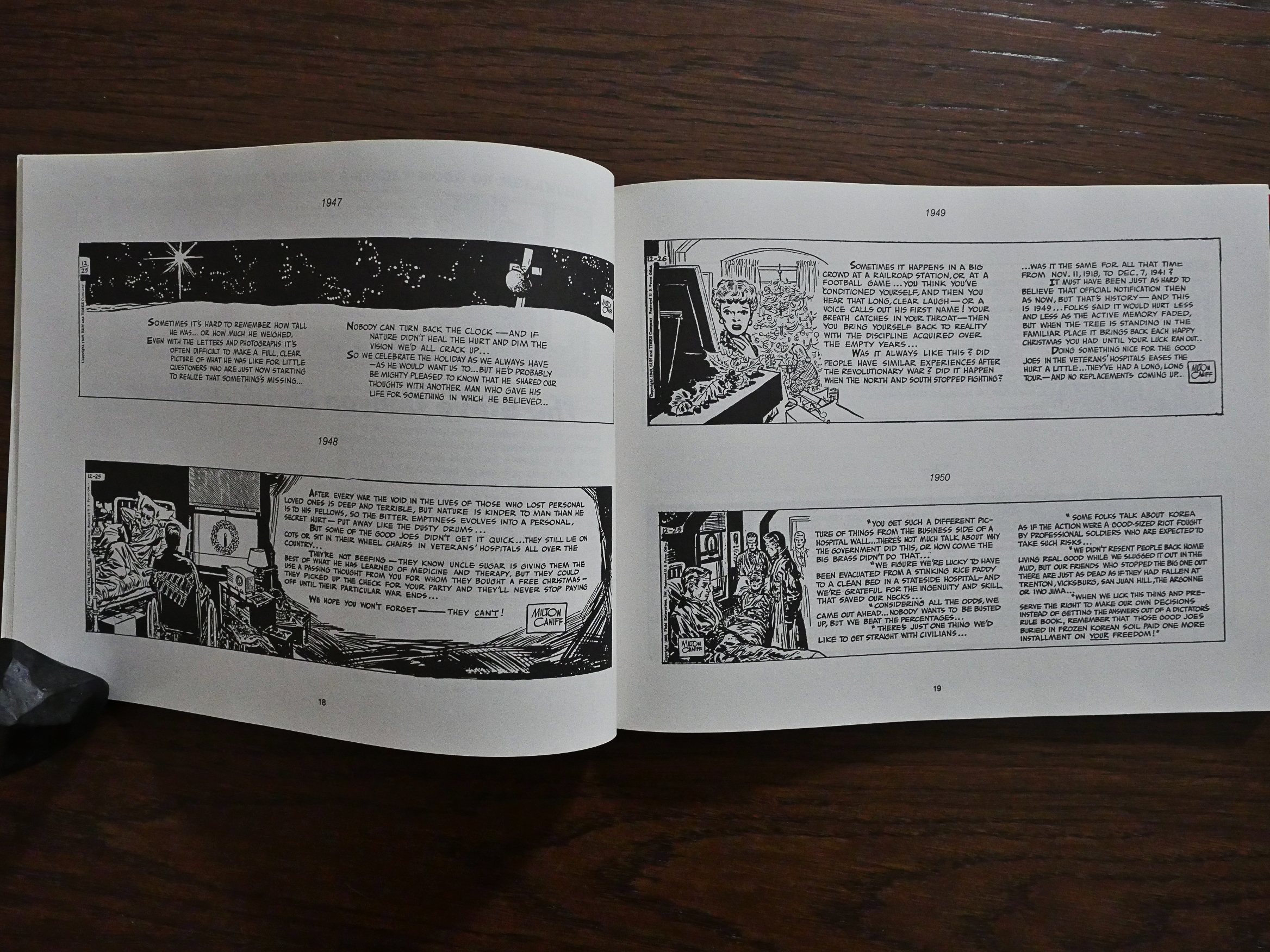

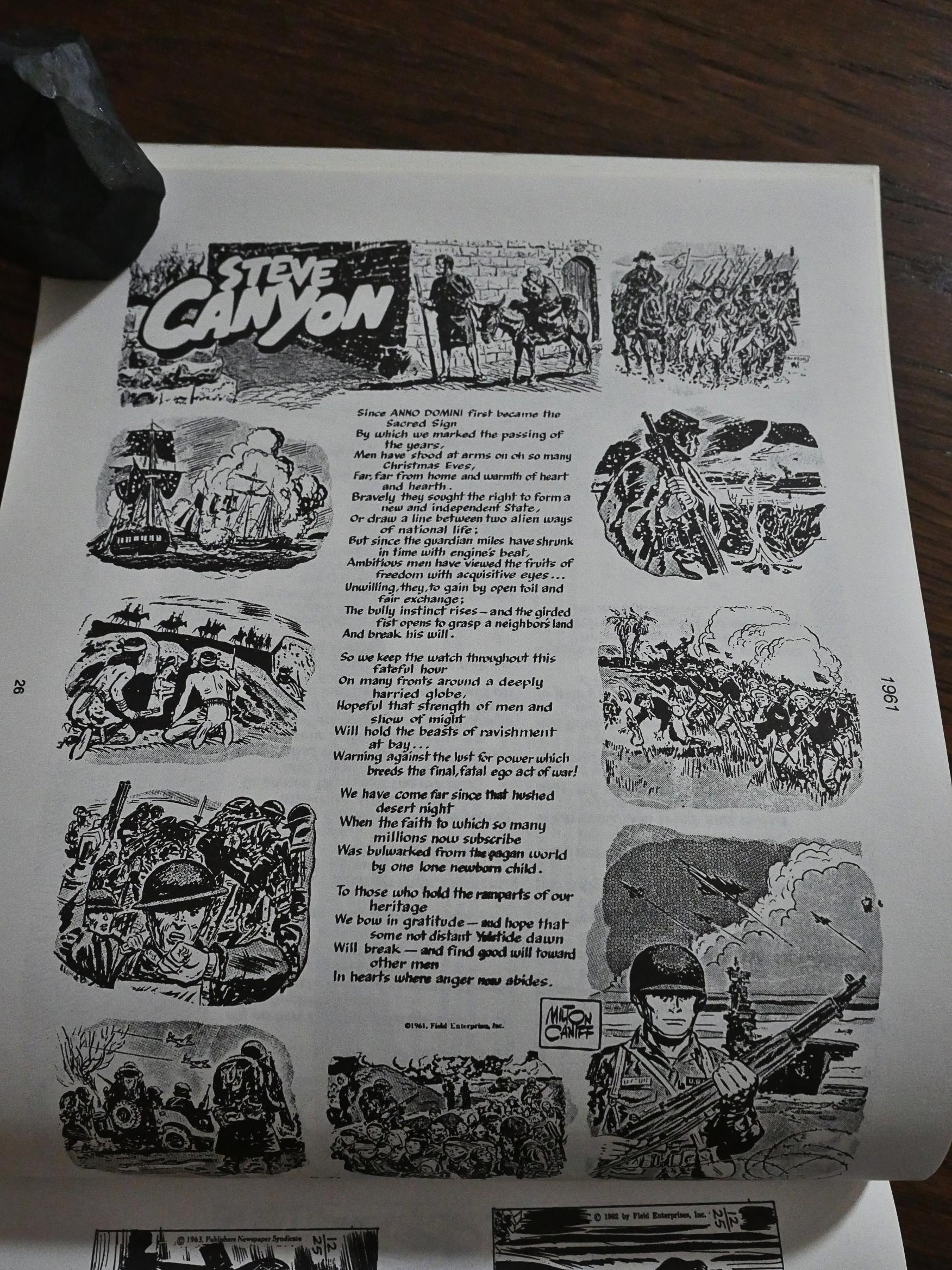

And these fell out of the final issue. I’m assuming it’s a clipping made by the same person as the other issue…

Aww.

I guess these issues were once owned by a child.

But what happened between Viz and Eclipse? The Comics Journal #123:

VIZ AND ECLIPSE SPLIT

In November Viz Communications will end its joint publishing venture with Eclipse Comics. Viz, a subsidary of the large Japanese publisher Shogakukan Inc., was formed in 1986 and began copublishing comic books with Eclipse in 1987 including Mai: The Psychic Girl, Xenon, Area 88, and The Izgend of Kamui.

Viz General Manager Seiji Horibuchi said the decision was made to split with Eclipse because sales on the titles were less than Eclipse had promised. Eclipse publisher Dean Mullaney agreed, adding only that sales could not be attributed to only one party in such a co-publishing venture.

Viz and Eclipse have agreed to allow their contract to expire in November. Mullaney called the split amicable.

Mai and Xenon were finite series. Mai will end in July and Xenon will end in November. The rights to Area 88 and Kamui will pass wholly to Viz in November. Eclipse had announced another Viz book. LUM*Umsei Yatsura. originally for Spring release, then pushed it back until 1989. It will now be published by Viz in ’89. Both Mullaney and Horibuchi said that the delay for LUM was not related to the break-up, although their accounts differ as to what the cause was.

Shortly after the book was delayed, Eclipse issued a press release attributing the delay to Shogakukan’s insistance that the book be printed in Japan. Horibuchi told the Journal this was not the case. He said the delay was due to a number of complex reasons which he declined to enumerate.

He said he requested that Mullaney retract the release, and Mullaney agreed. Mullaney claimed, however, that he had never been asked to retract the press release and told the Journal that as far as he knew the delay was caused by Viz’s insistence on Japanese printing.

OK then!

The final six issues of Area 88 were printed in Canada, so I guess Viz… changed their minds? Or perhaps somebody’s er misremembering.

Despite the alleged low sales, Eclipse would publish a number of Japanese comics over the following two years, but with a new packager: Studio Proteus. That ultimately ended in Eclipse going bankrupt, but not for the reasons you might guess.

I’ll cover that story when we get to it chronologically.