Stig’s Inferno (1984 Vortex) #1-5, Stig’s Inferno (1987) #6-7 by Ty Templeton.

As a teenager, this was one of my favourite comics, and I still perk up at the mention of Ty Templeton’s name despite not really following his career much after starting to work at super-hero comics. I seem to dimly remember an … origin story … of … Doctor Light? Can that be right? Early 90s?

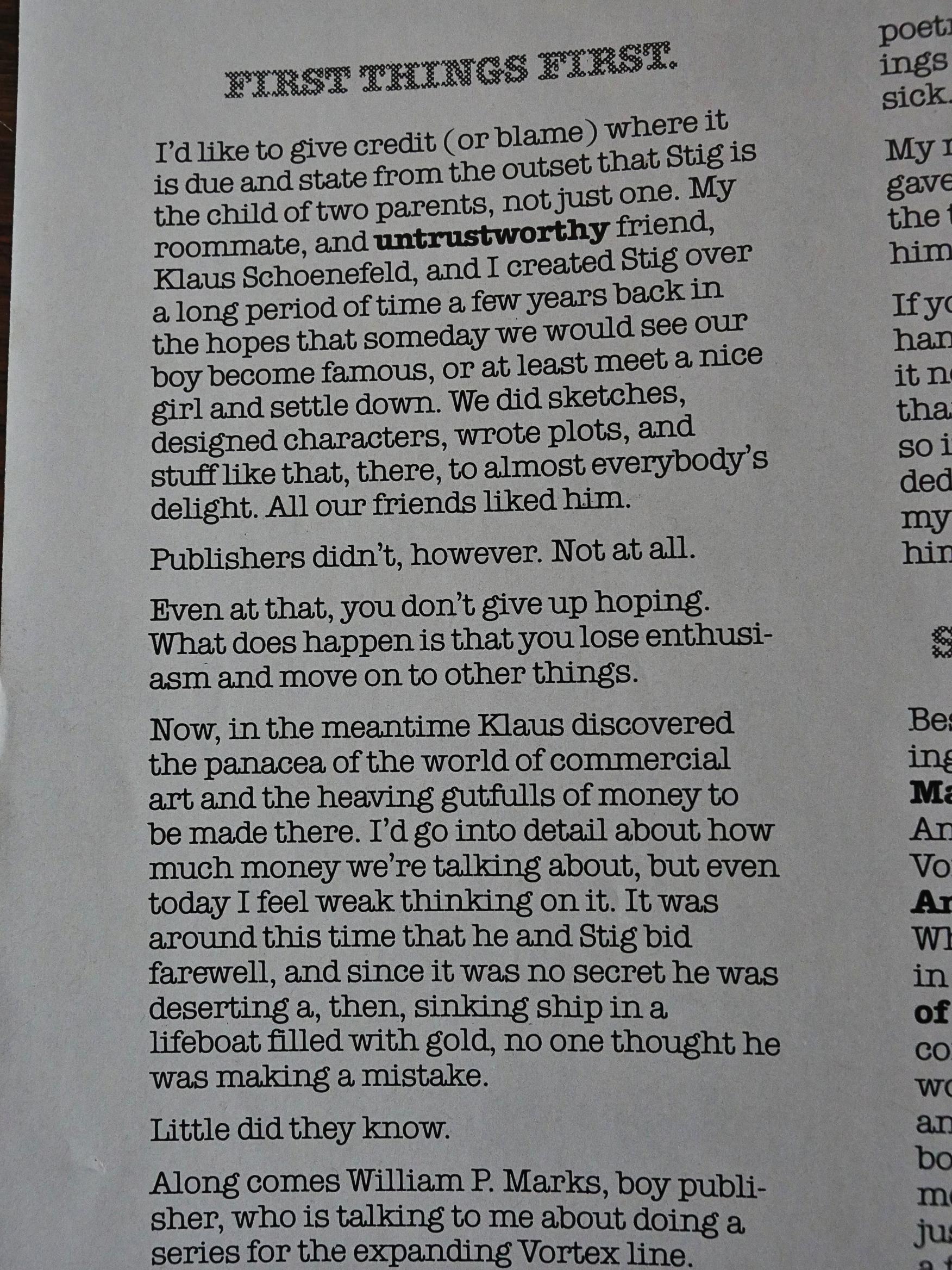

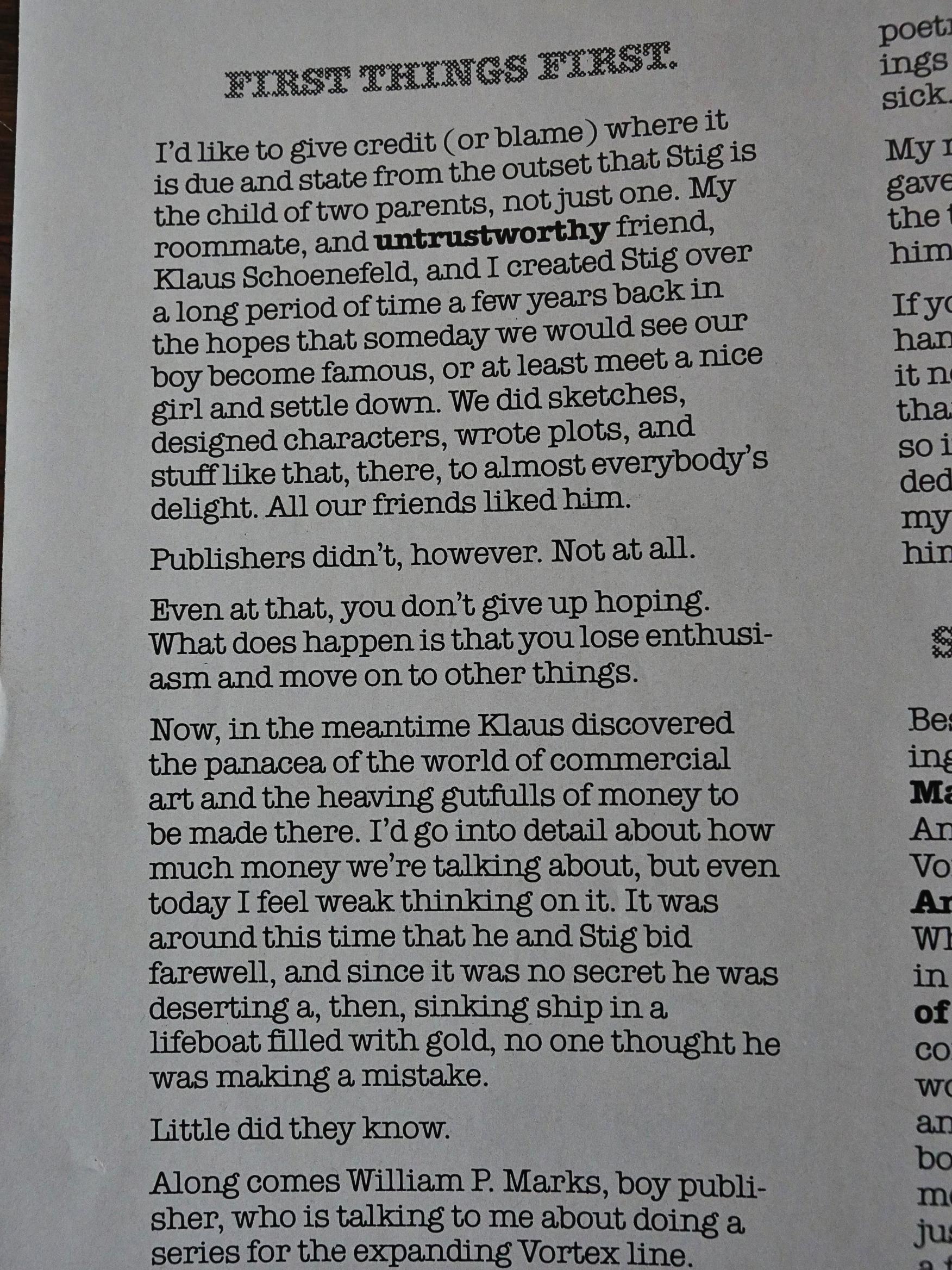

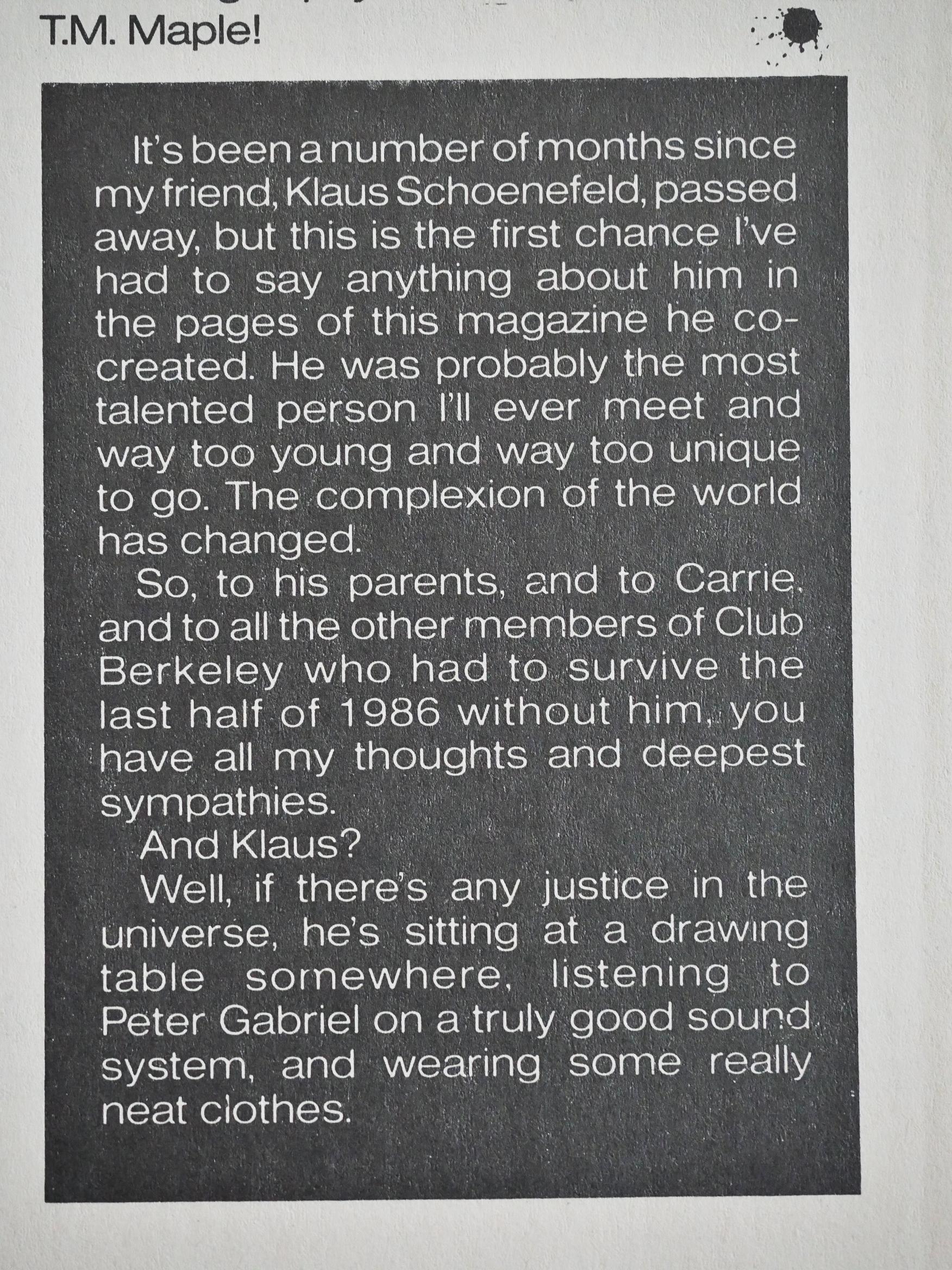

Anyway, this was originally published (lethargically) by Vortex Comics for the five first issues. Templeton explains that Stig’s Inferno was co-created by Klaus Schoenefeld, but was picked up by (later notorious) publisher Bill Marks after Schoenefeld had stopped doing comics, so Templeton did the book solo.

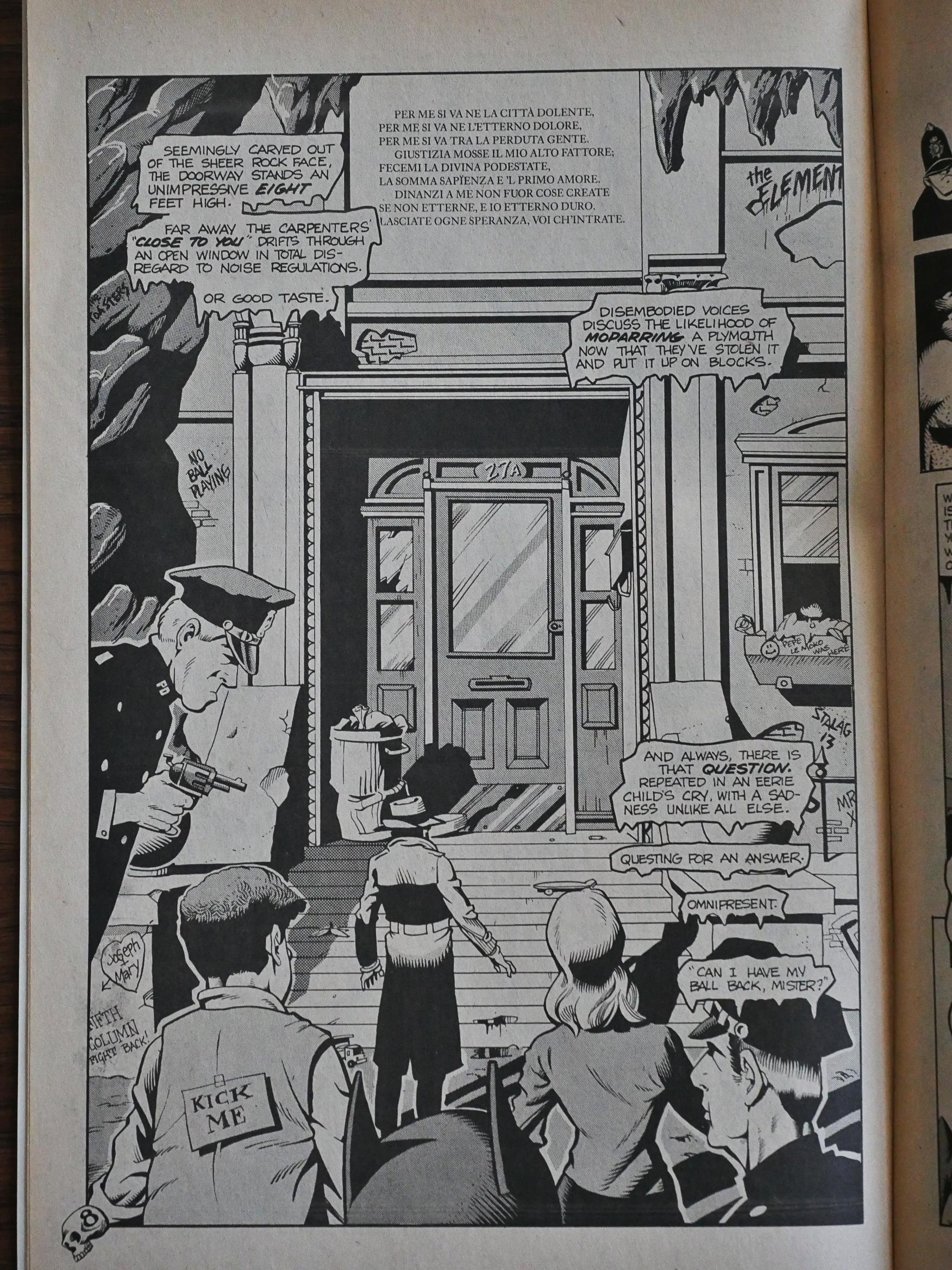

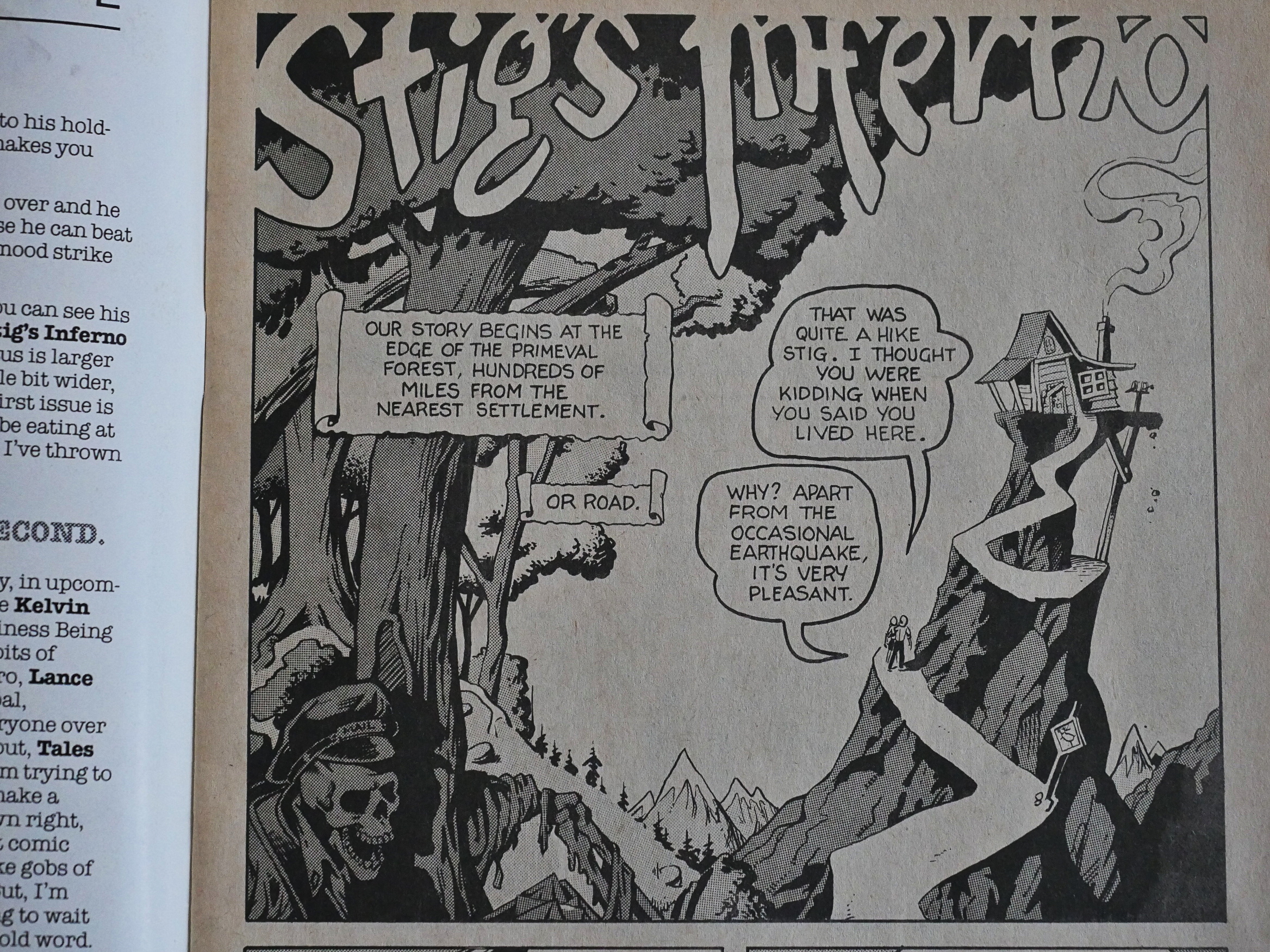

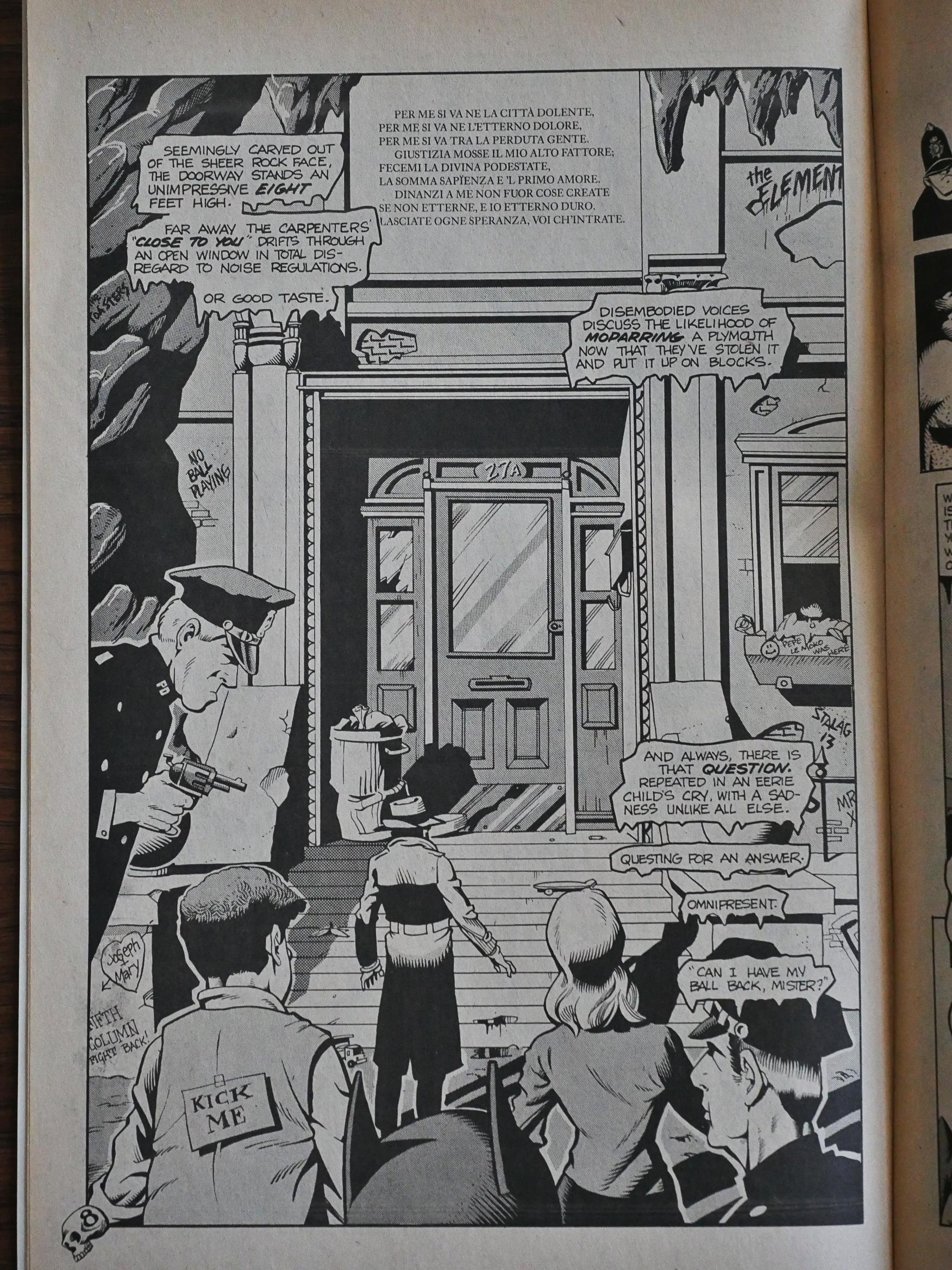

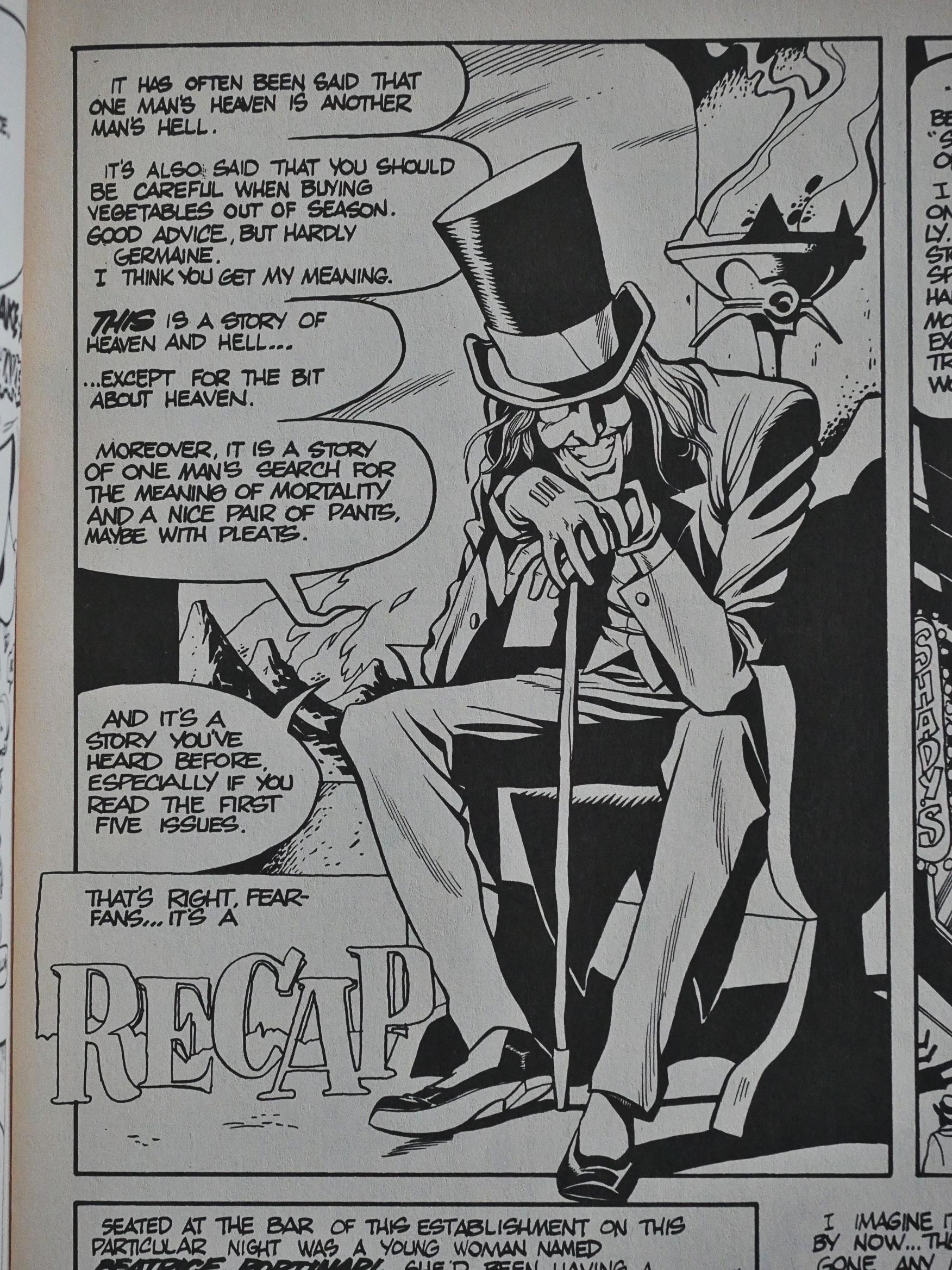

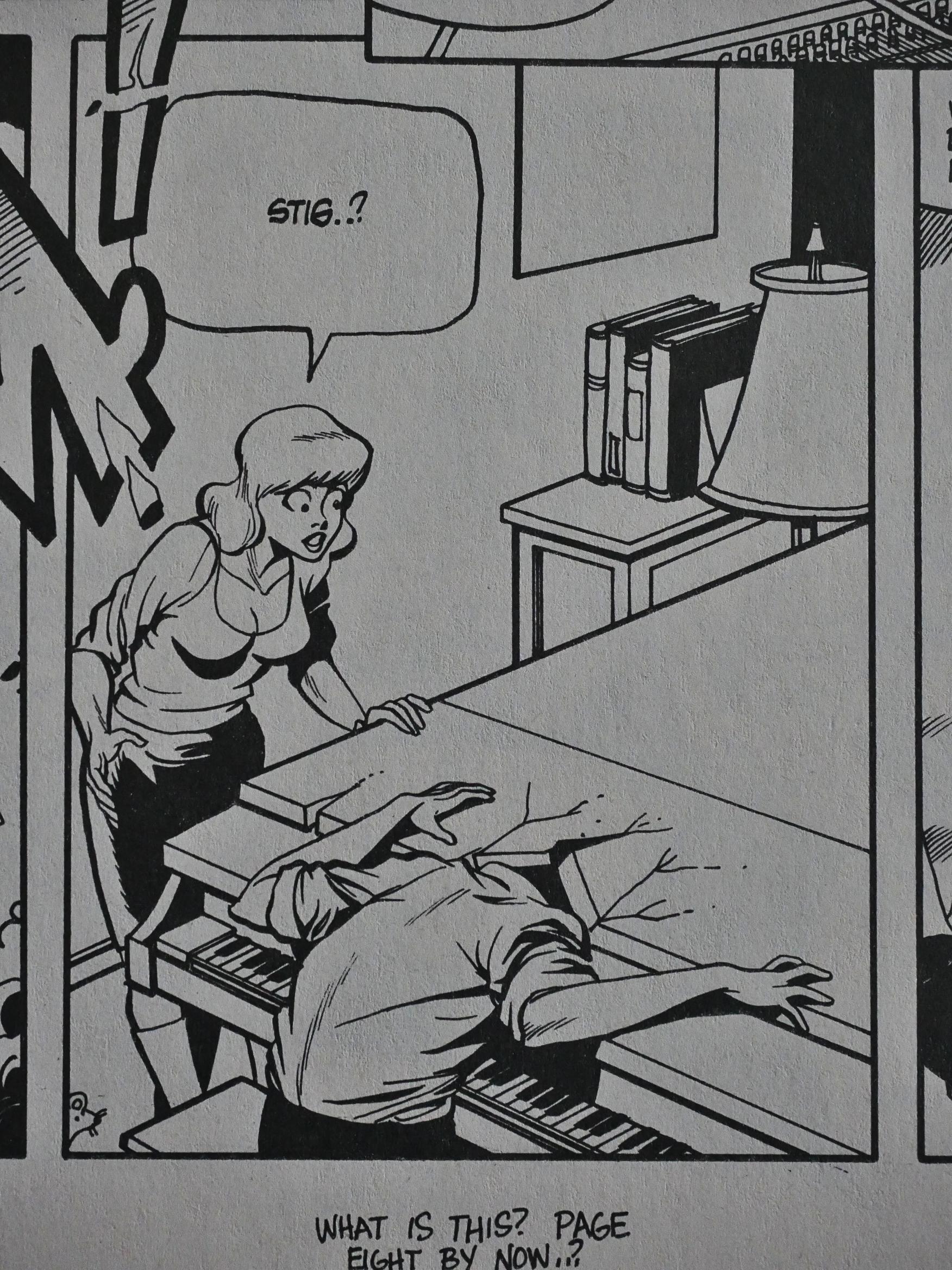

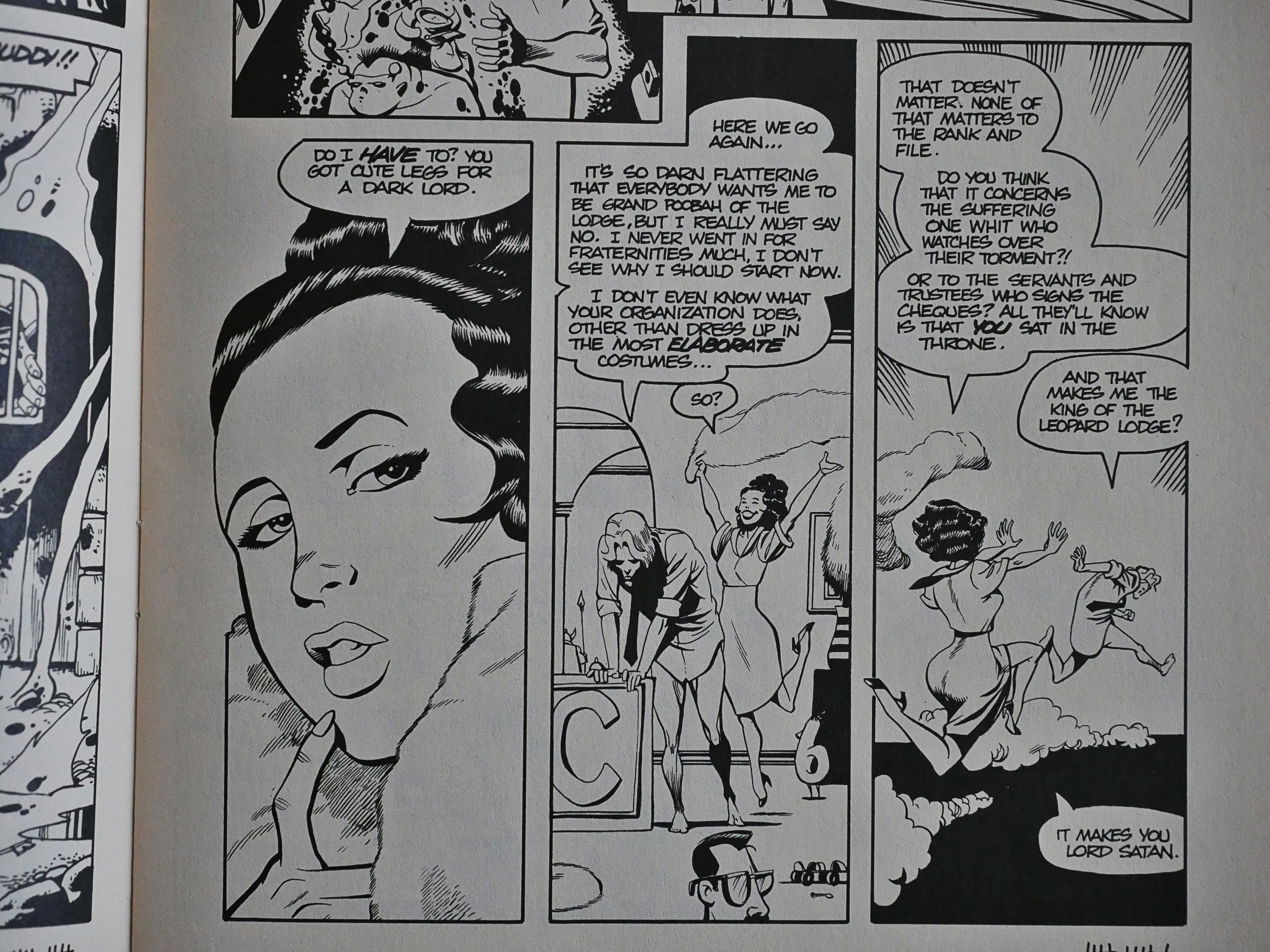

The immediate attraction here is, of course, Templeton’s almost impossibly sharp artwork. It’s got a Wally Wood feel to spotting of blacks, but otherwise Templeton isn’t a Wood disciple, I think.

His faces and figures are… Uhm… A bit Bill Elder? I don’t know, but the mix is really attractive and fun to look at and to read.

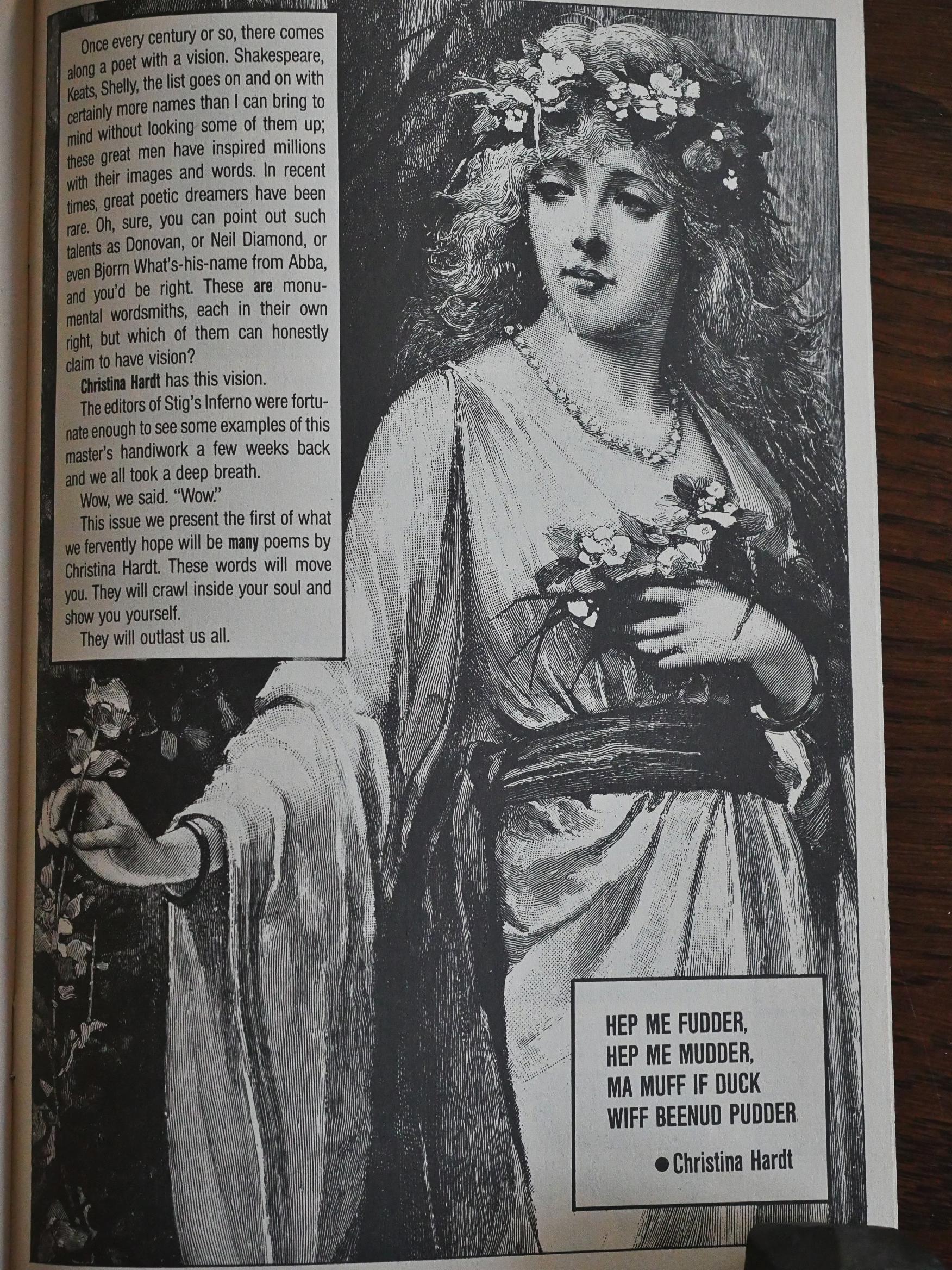

And the jokes were just perfect for a *counts on fingers* 15 year old me. I thought it was the silliest and funniest thing ever. Re-reading it now, I, er, don’t, but I still find it very amusing. There’s so many of these jokes that even if half of them don’t quite land, the cumulative effect is appreciable.

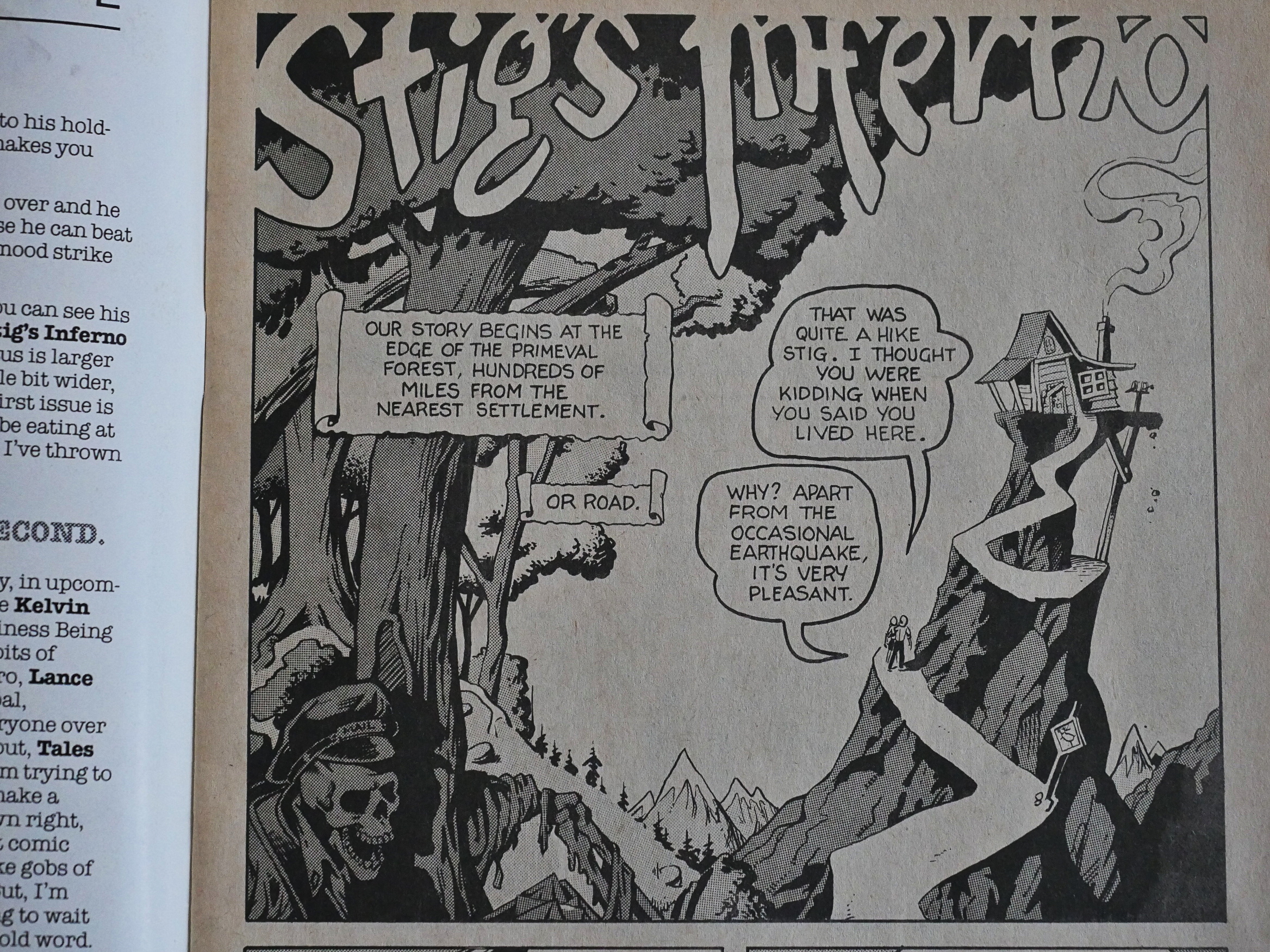

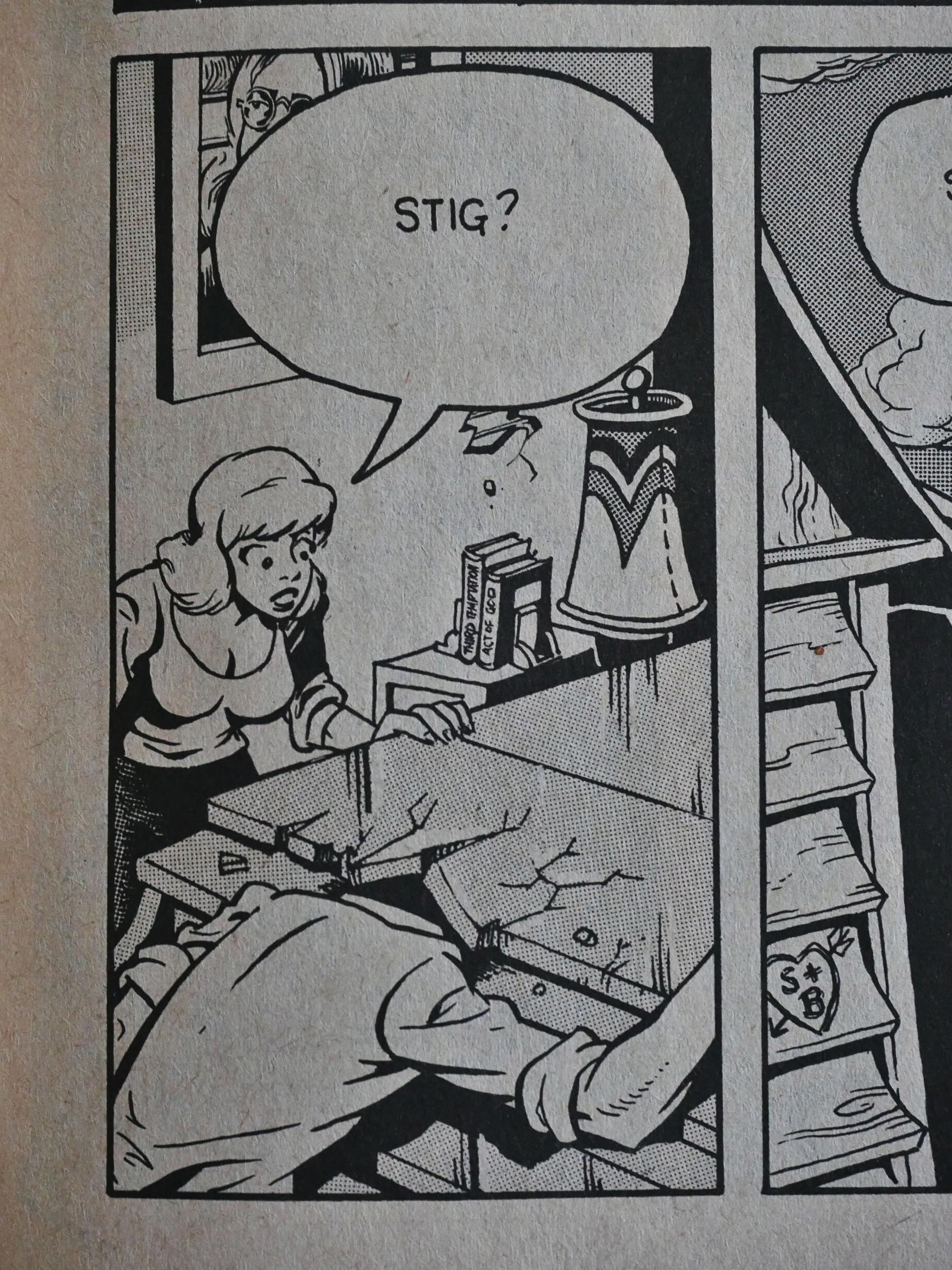

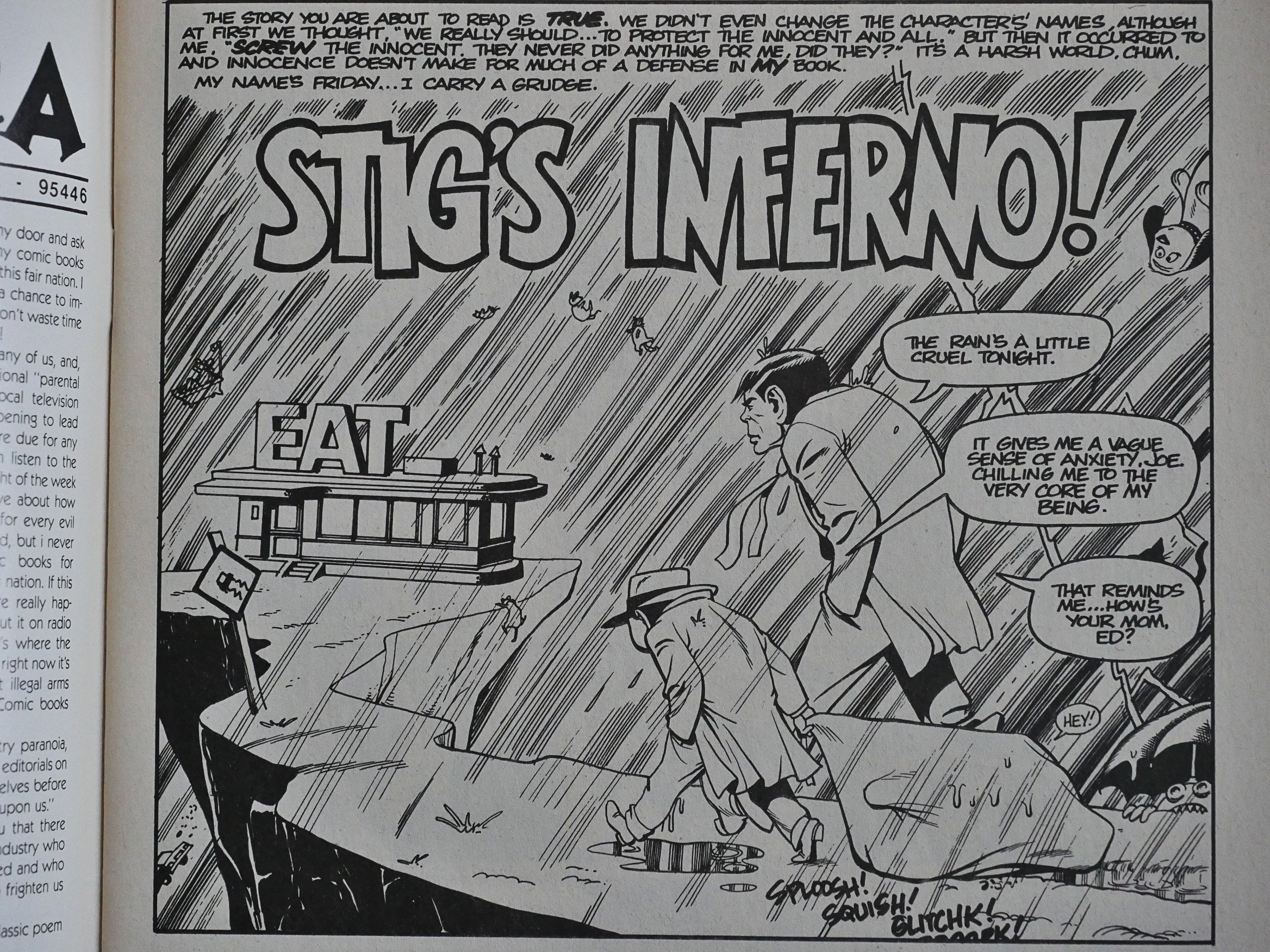

The plot is that Stig dies…

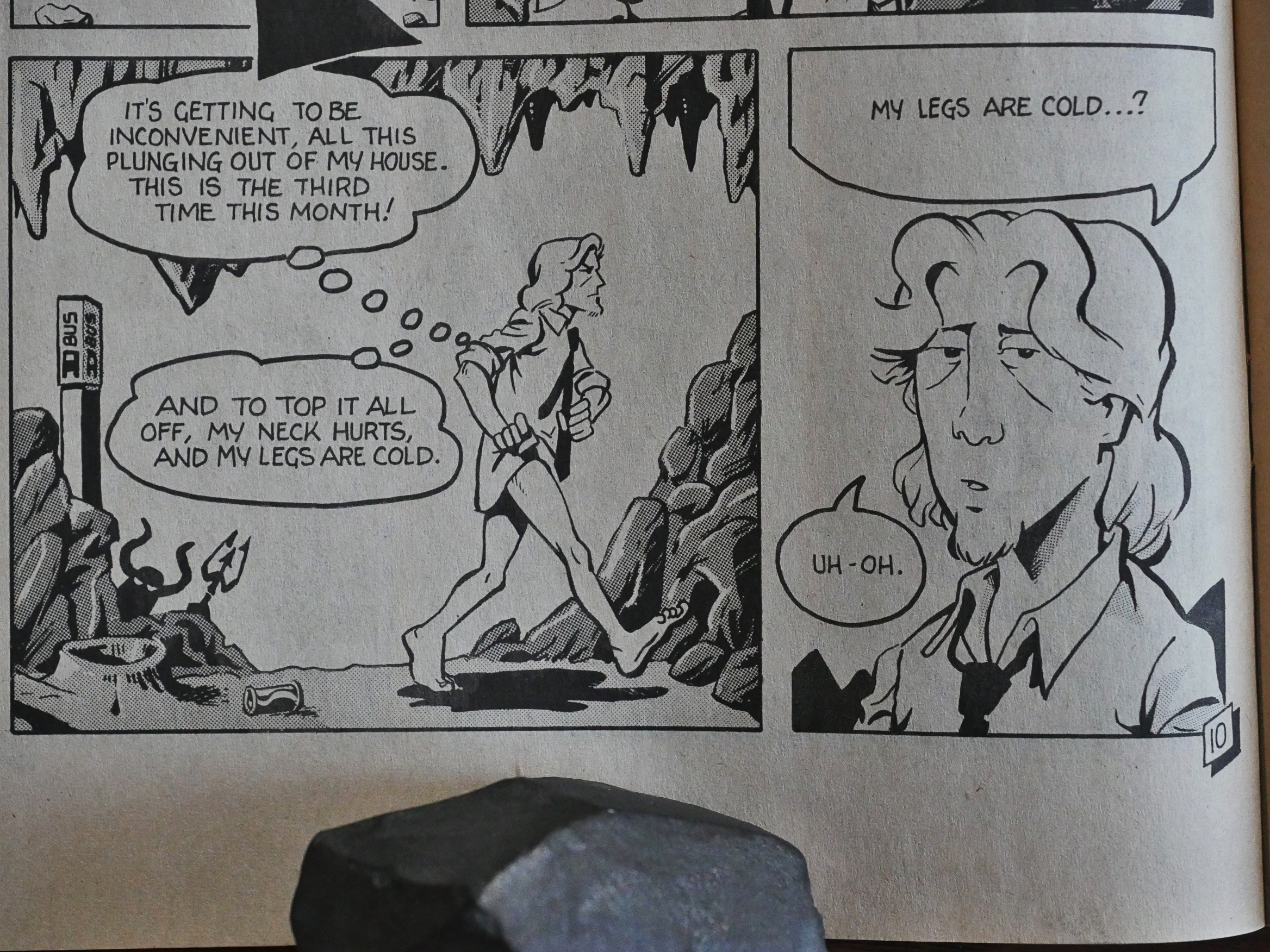

… and then lands up in hell without knowing that he’s dead or that he’s in hell. He thinks he’s in a fantasy film shoot most of the time.

Oh, and he’s pantsless. If there’s one thing people know about this book if they know anything, it’s that it’s about that pantsless guy in hell.

(Art by Templeton and Anthony van Bruggen.)

The Vortex issues are brief: They’re only 24 pages long, which is an unusual length. The vast majority of American comic books are (or were) 32 pages long, and if they wanted to go shorter, they have to go to 16 pages (which Eclipse did with books like Airboy). Vortex is a Canadian publisher, though, and perhaps they have printers there that fold paper in a different way.

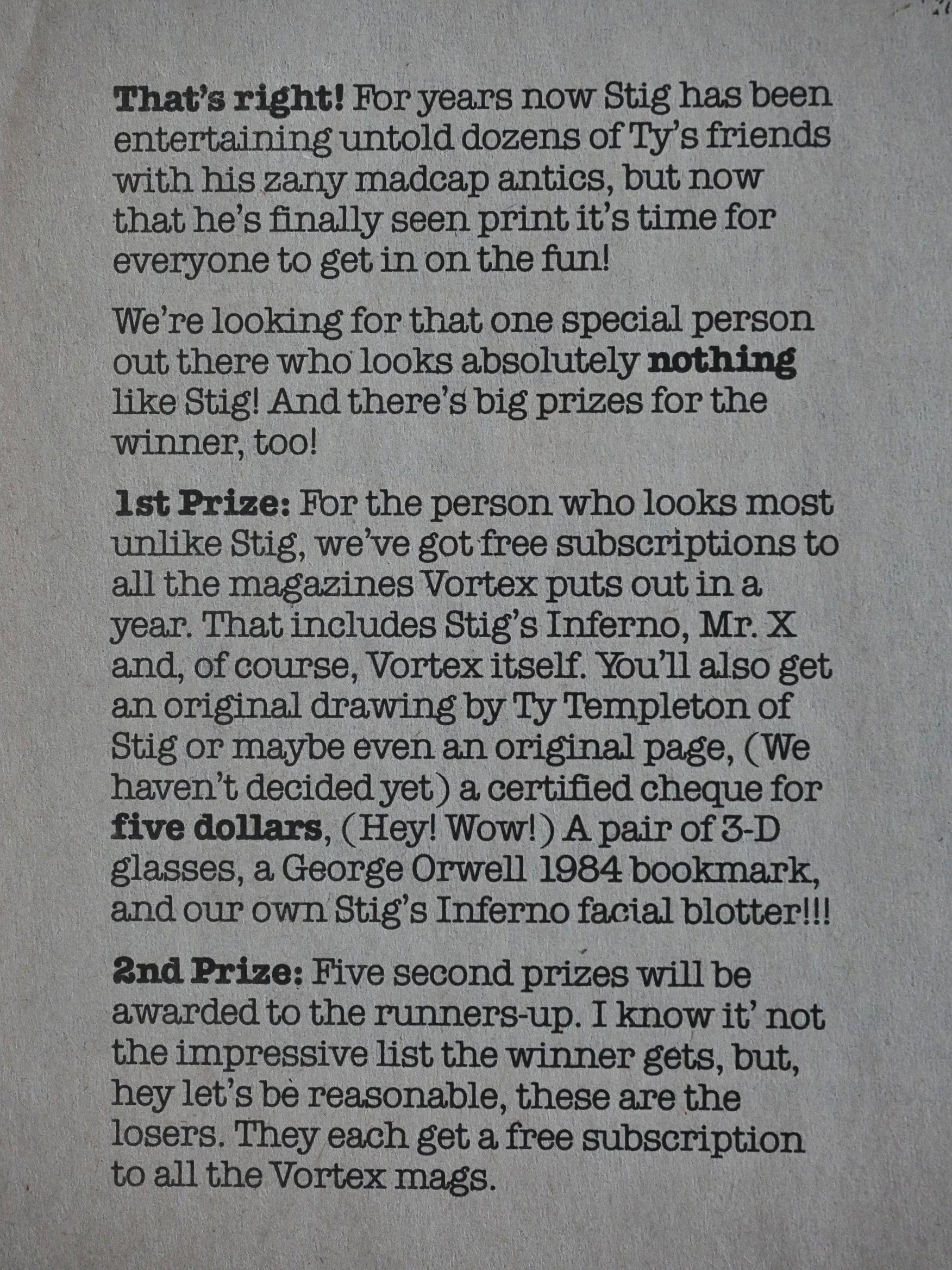

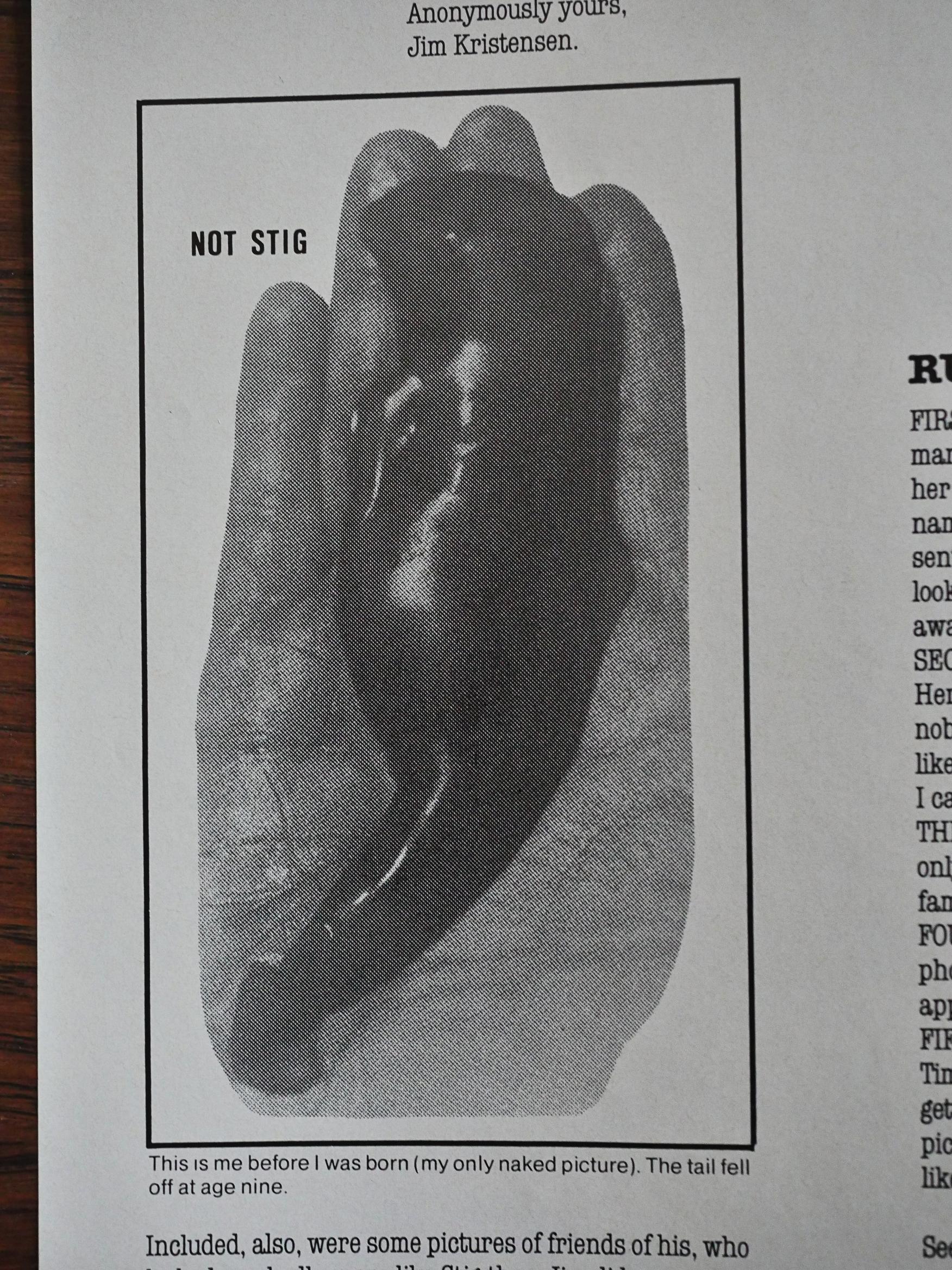

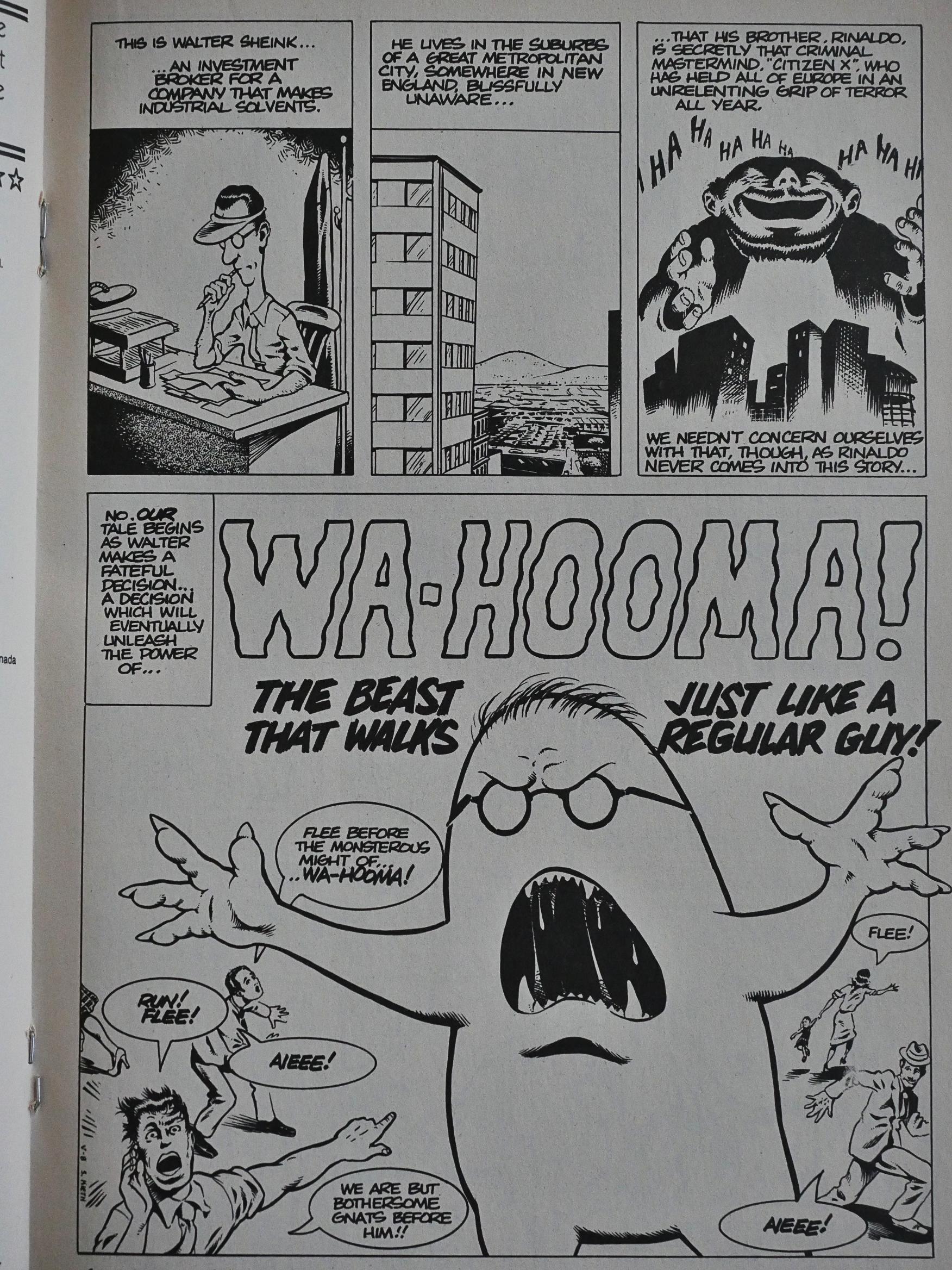

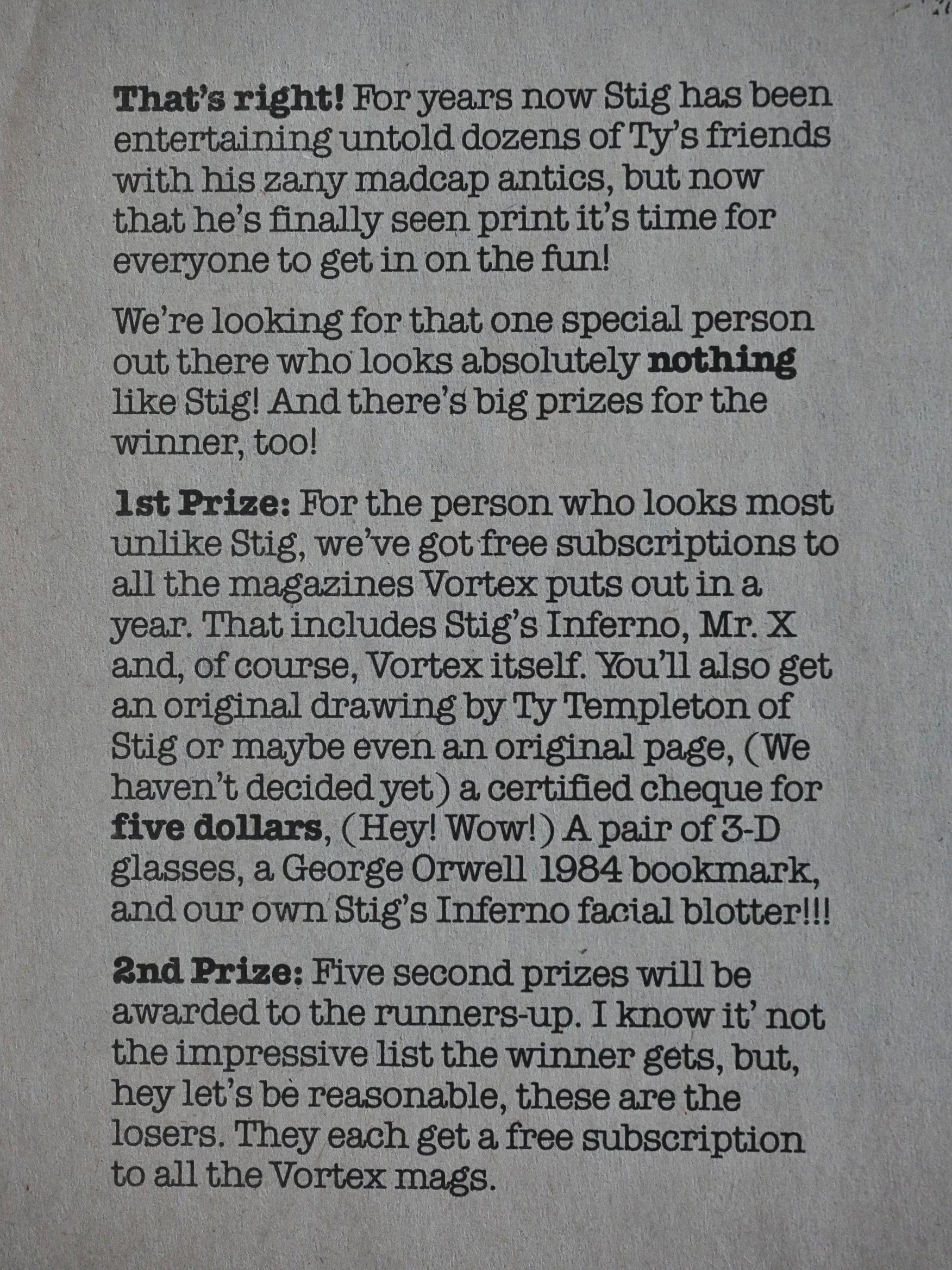

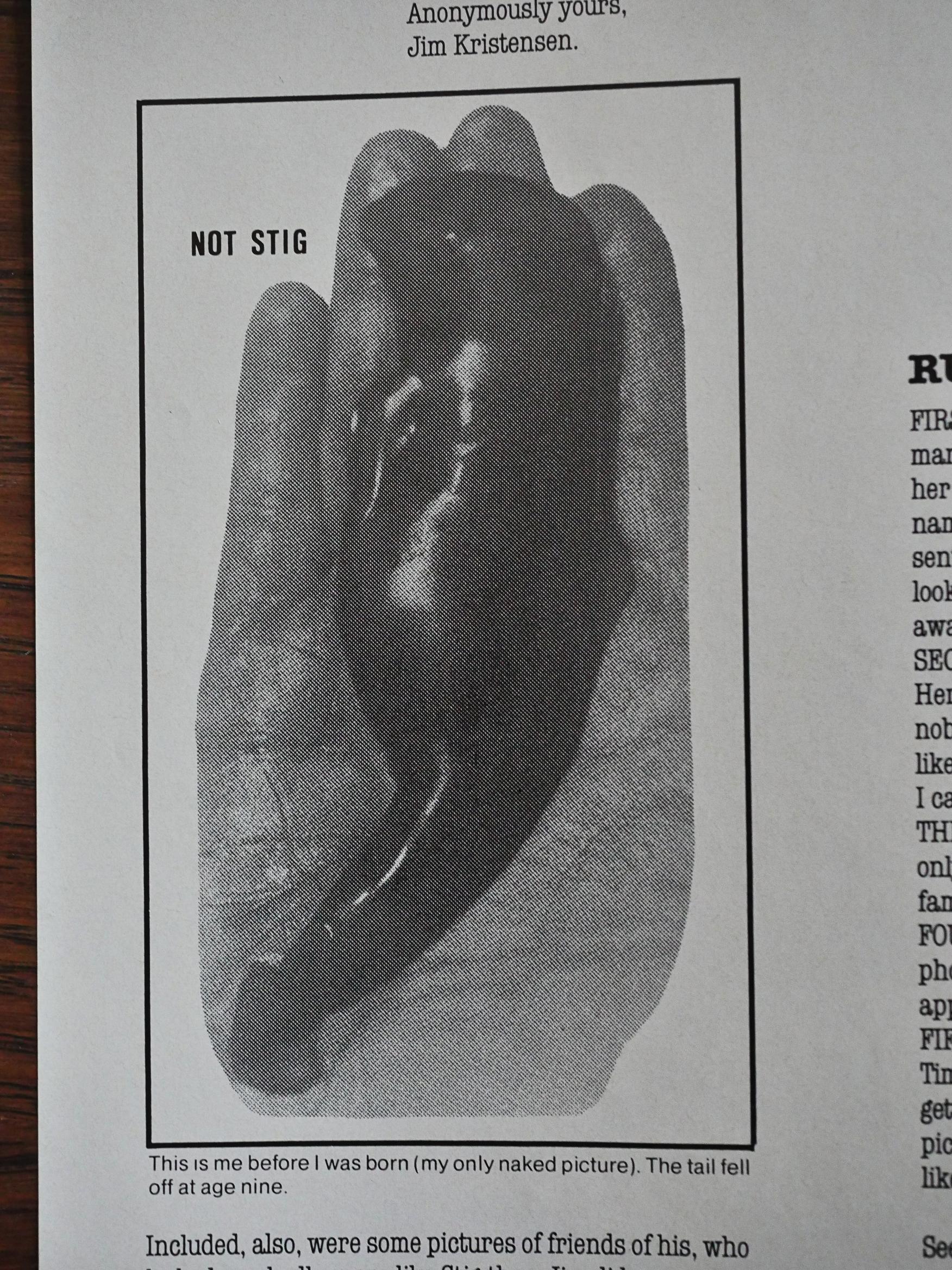

And the main feature only occupies twelve to fifteen pages of each issue, so there’s only a short jolt of Stigness before it’s onto something else that’s almost equally silly, like this Not Stig competition…

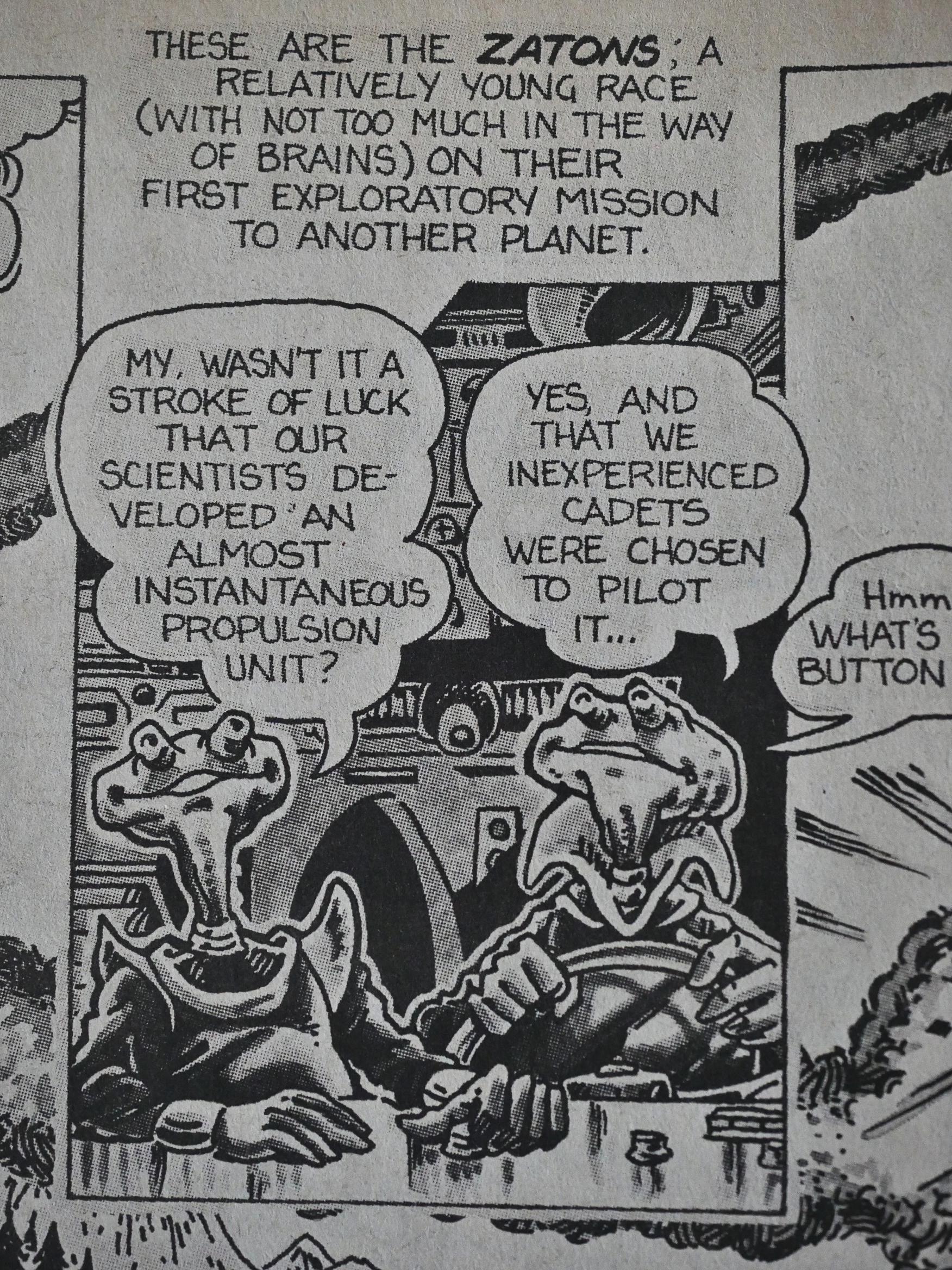

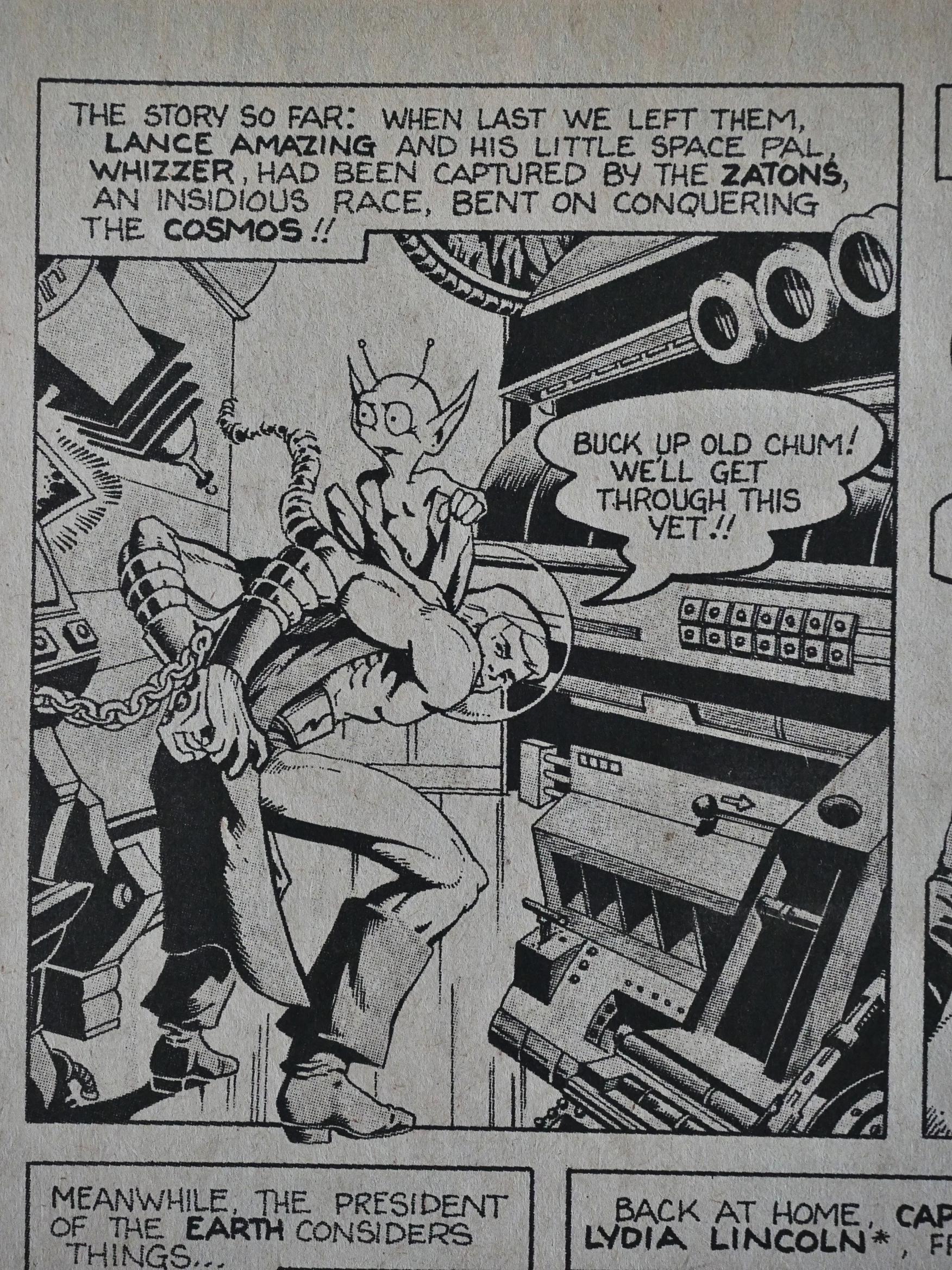

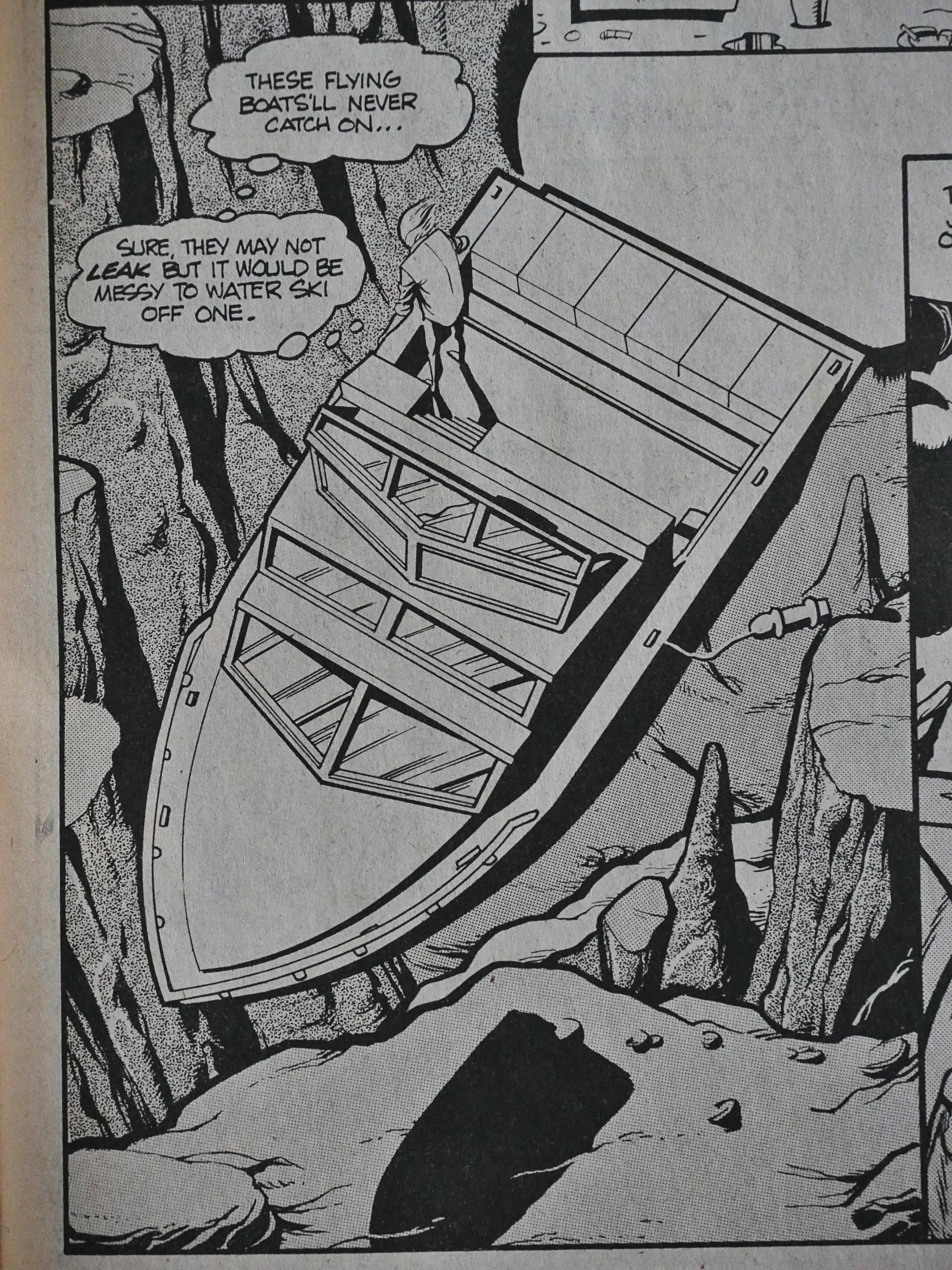

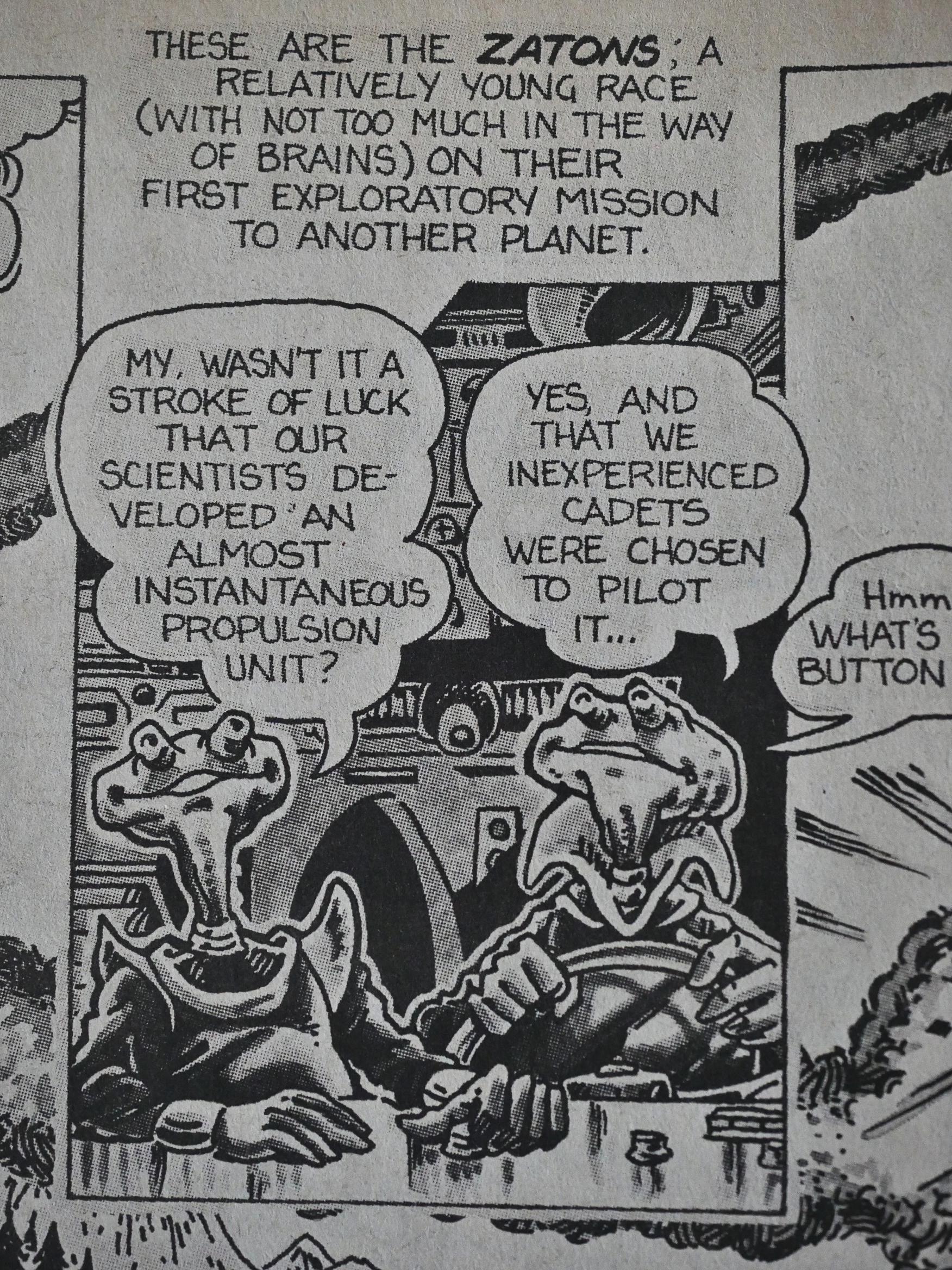

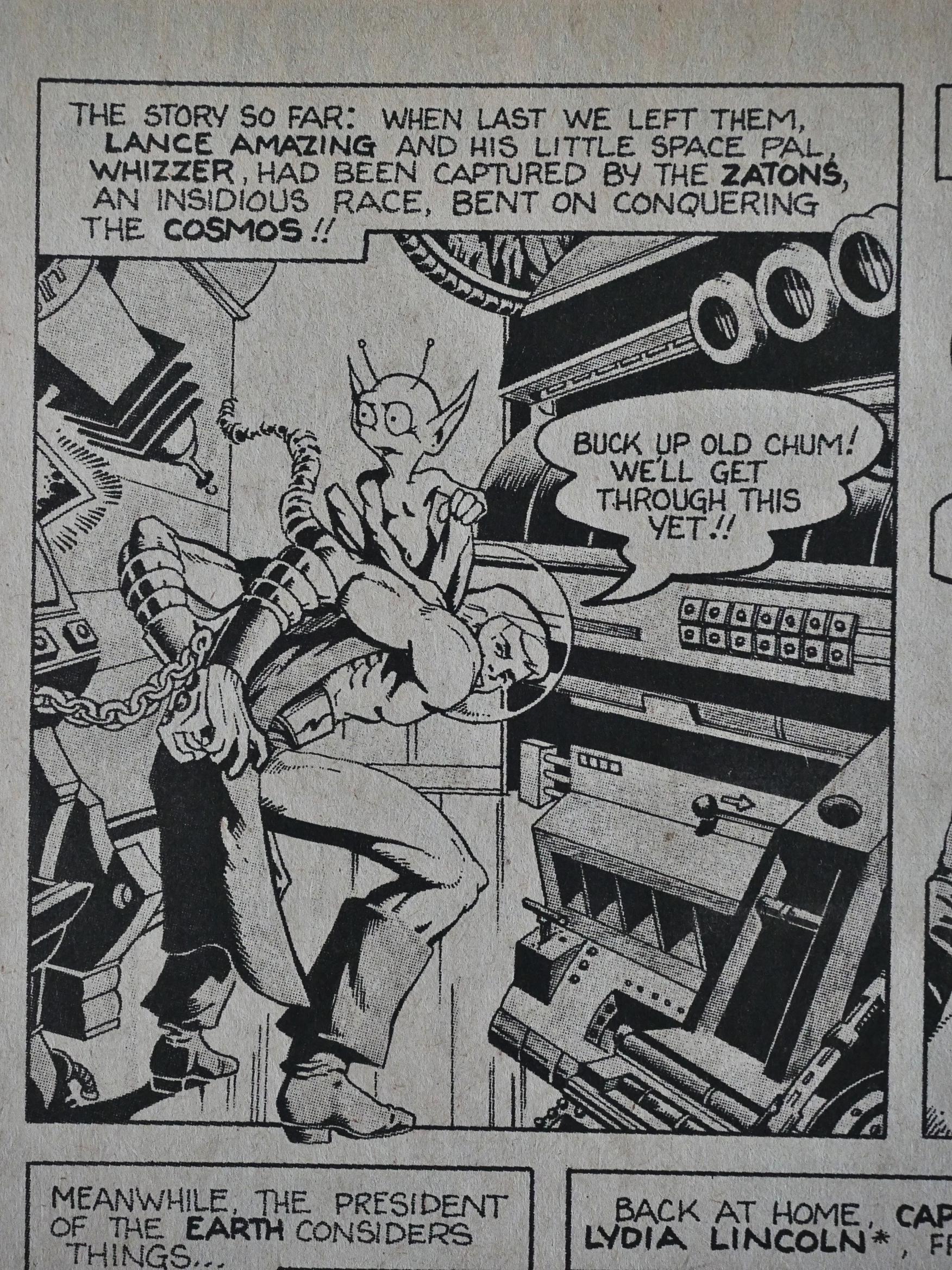

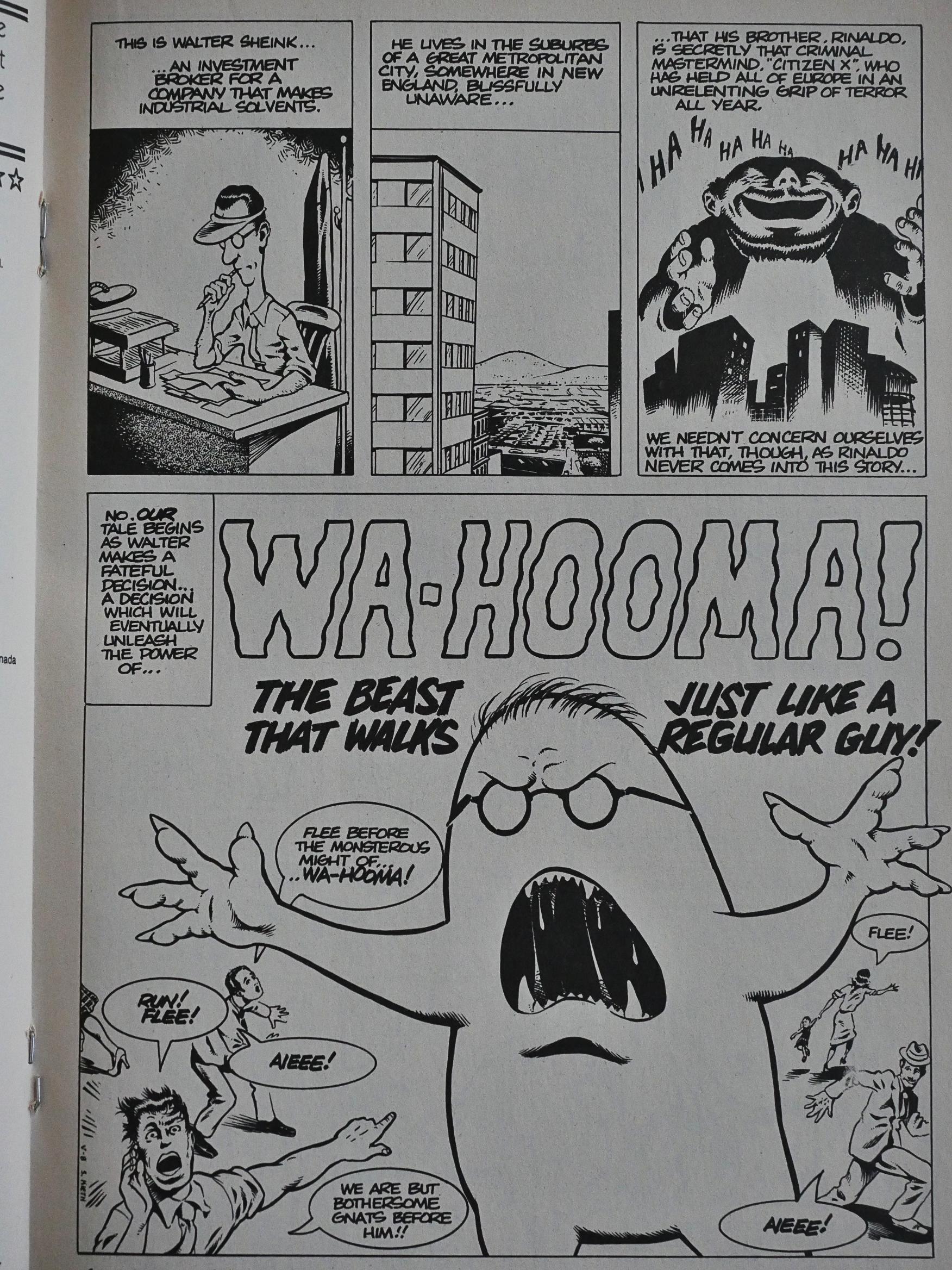

… or even sillier things, like the very brief Lance Amazing backup.

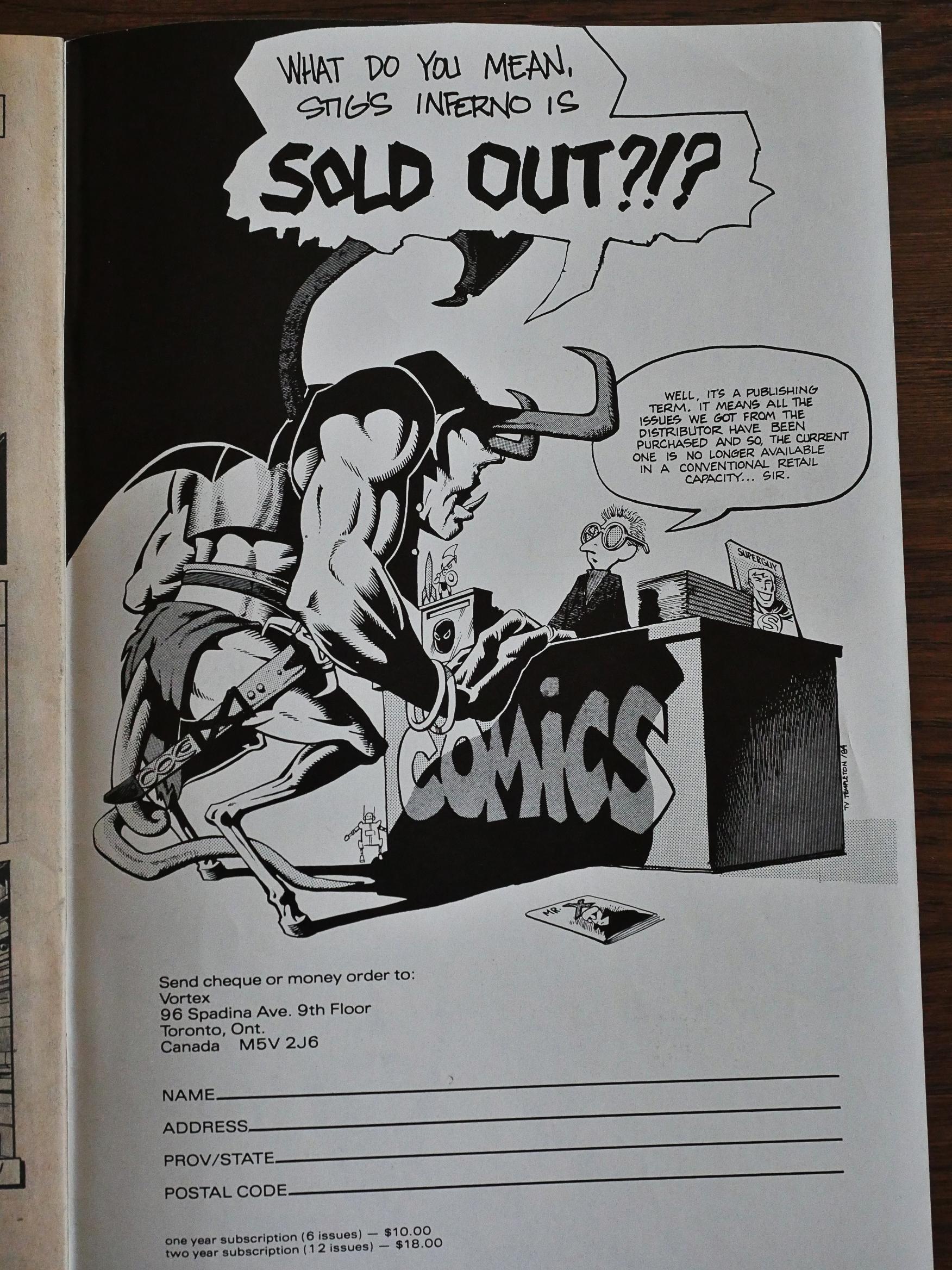

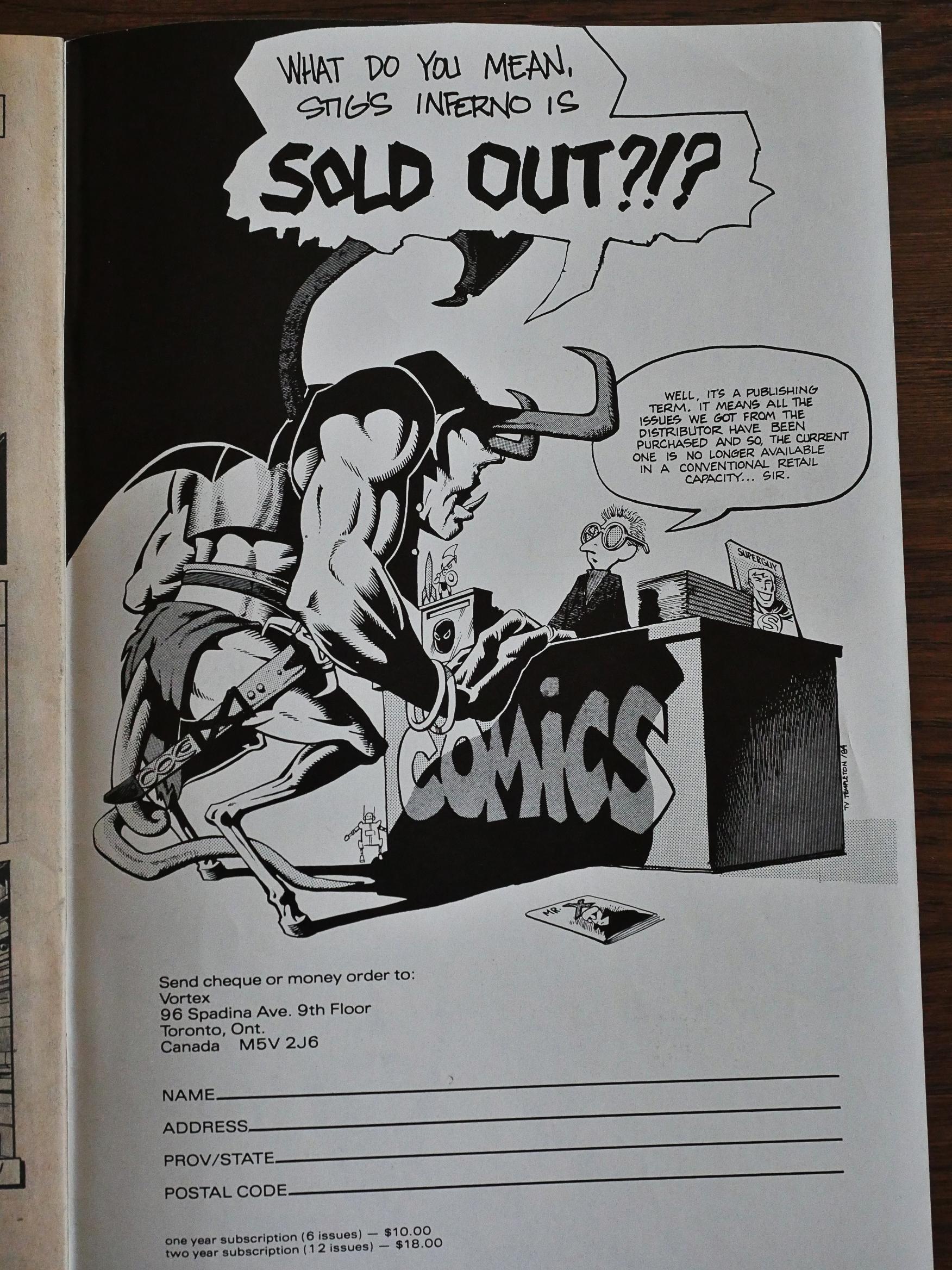

Wow, that’s a super-sharp ad.

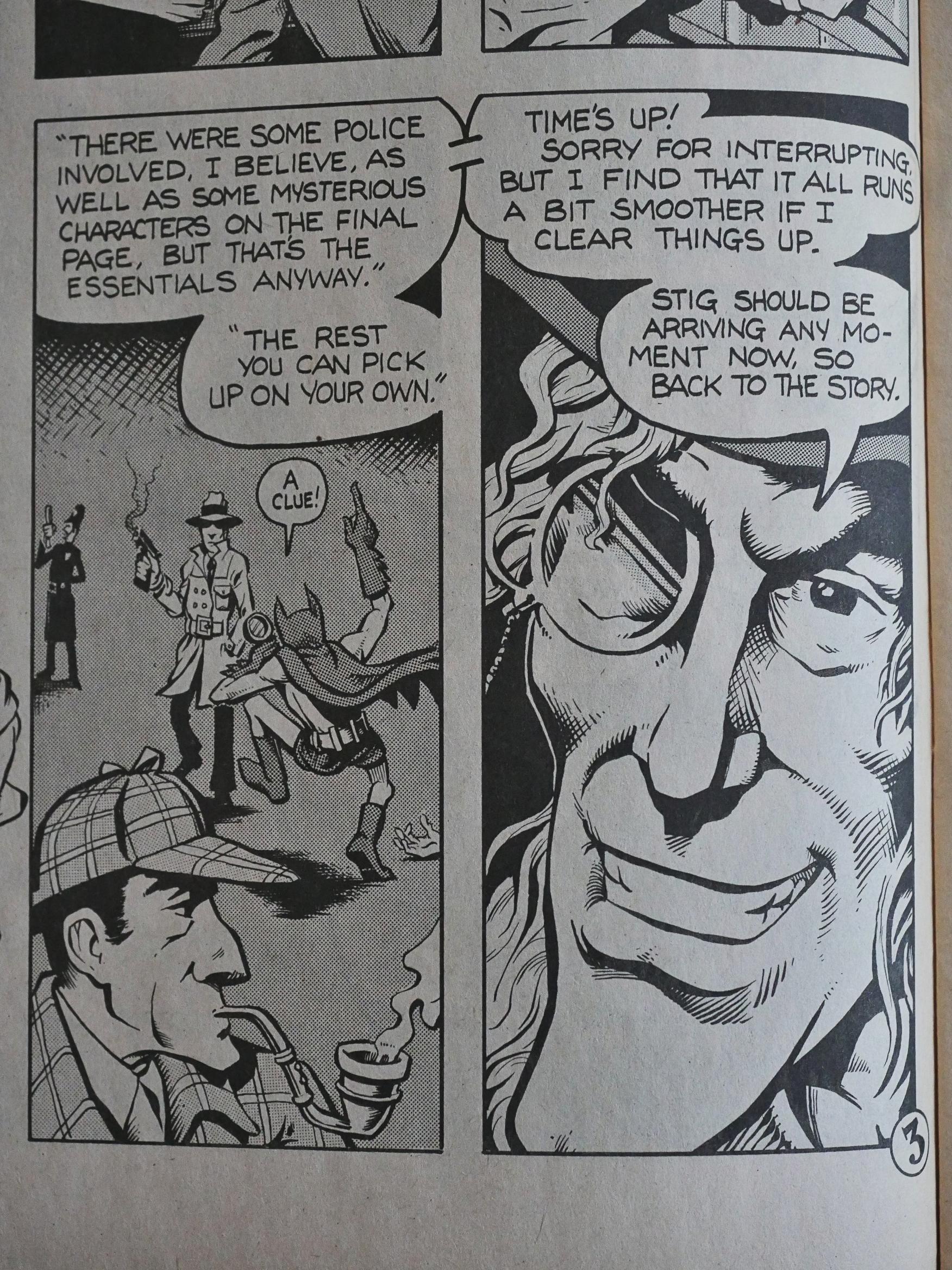

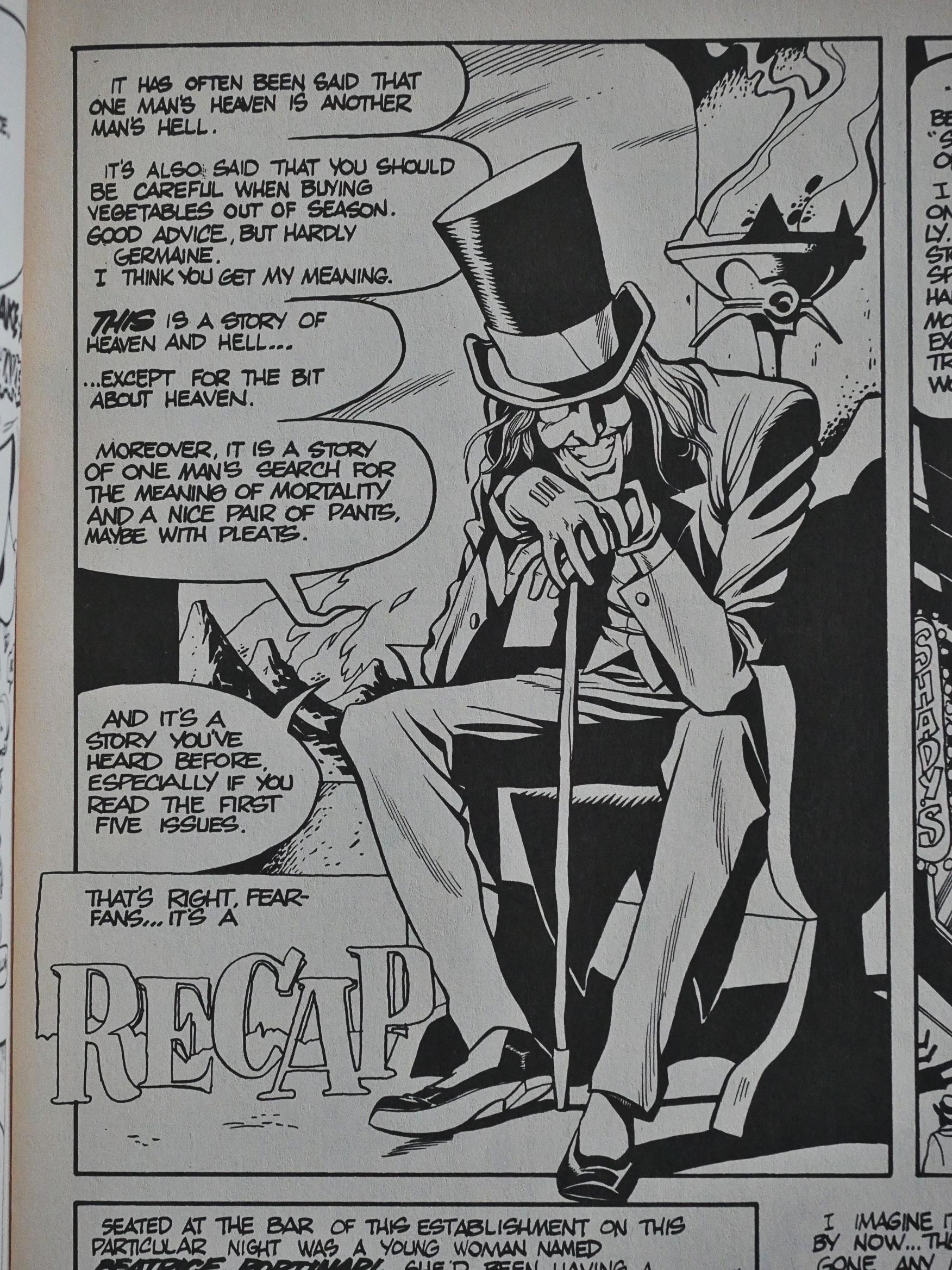

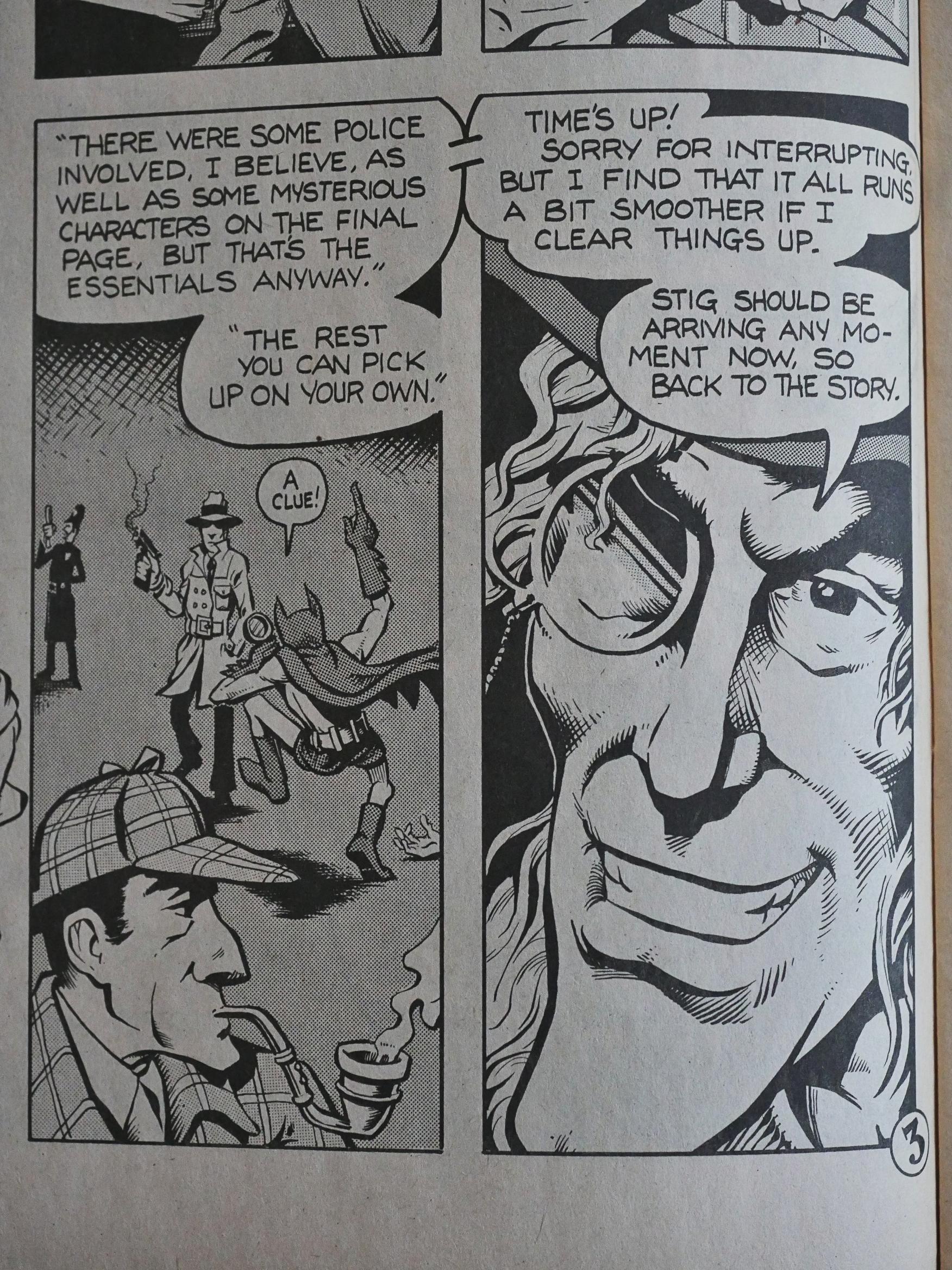

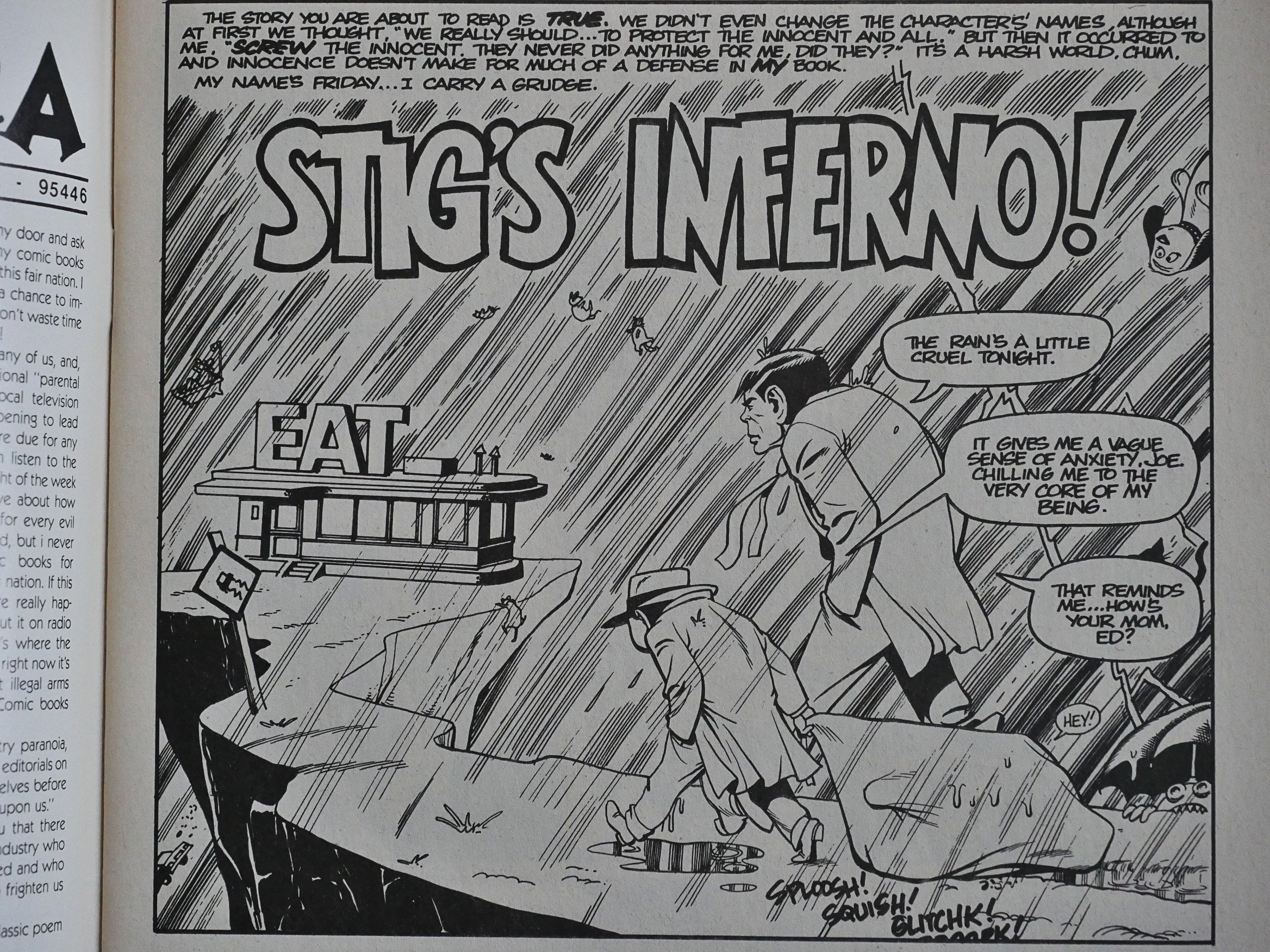

In the second issue, Templeton introduces a Crypt-Keeper like figure to provide the recaps and framing sequences between the stories. And recaps are probably necessary, because the five issues were published over a two-year period.

The winner of the Not Stig competition.

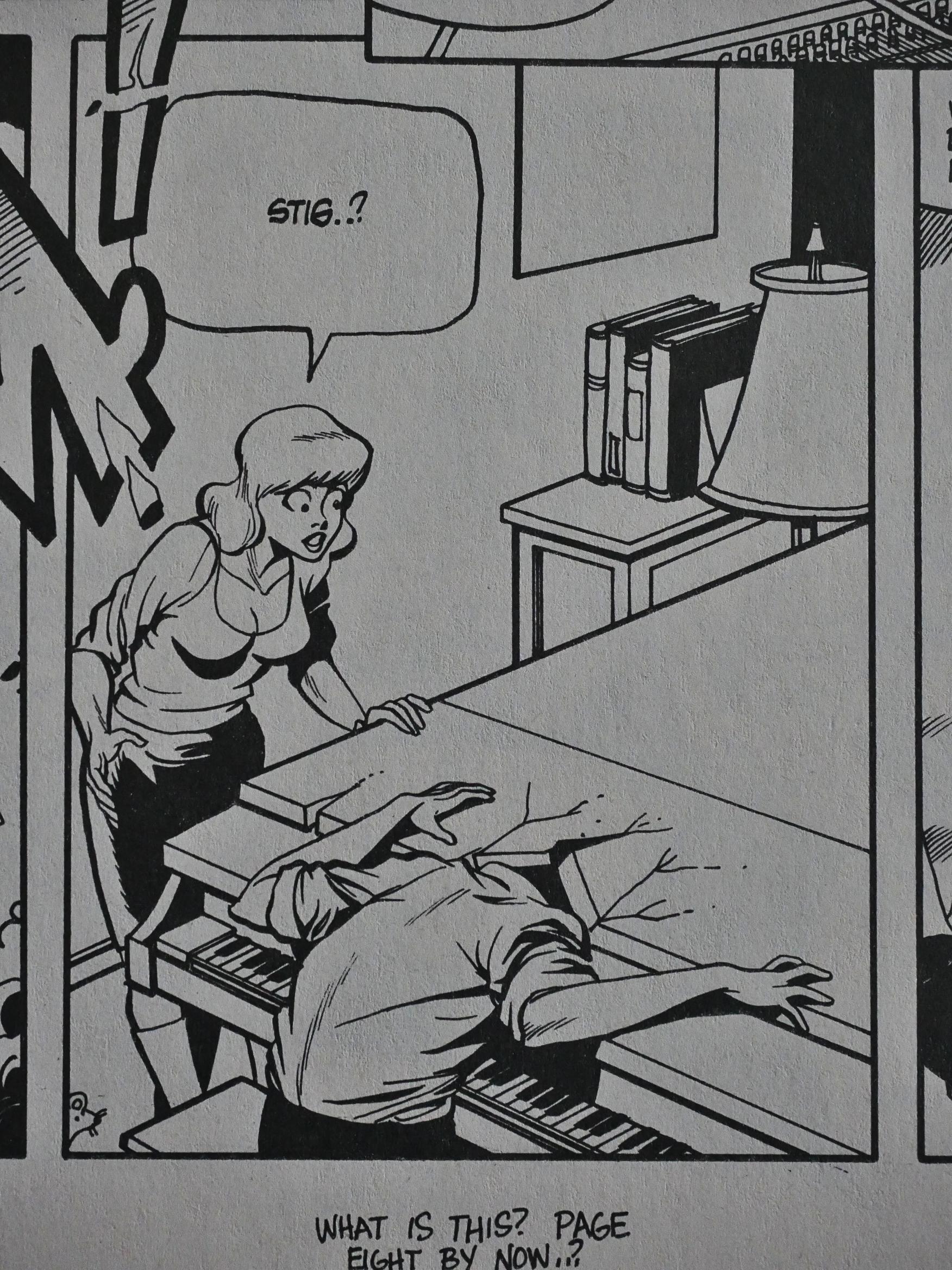

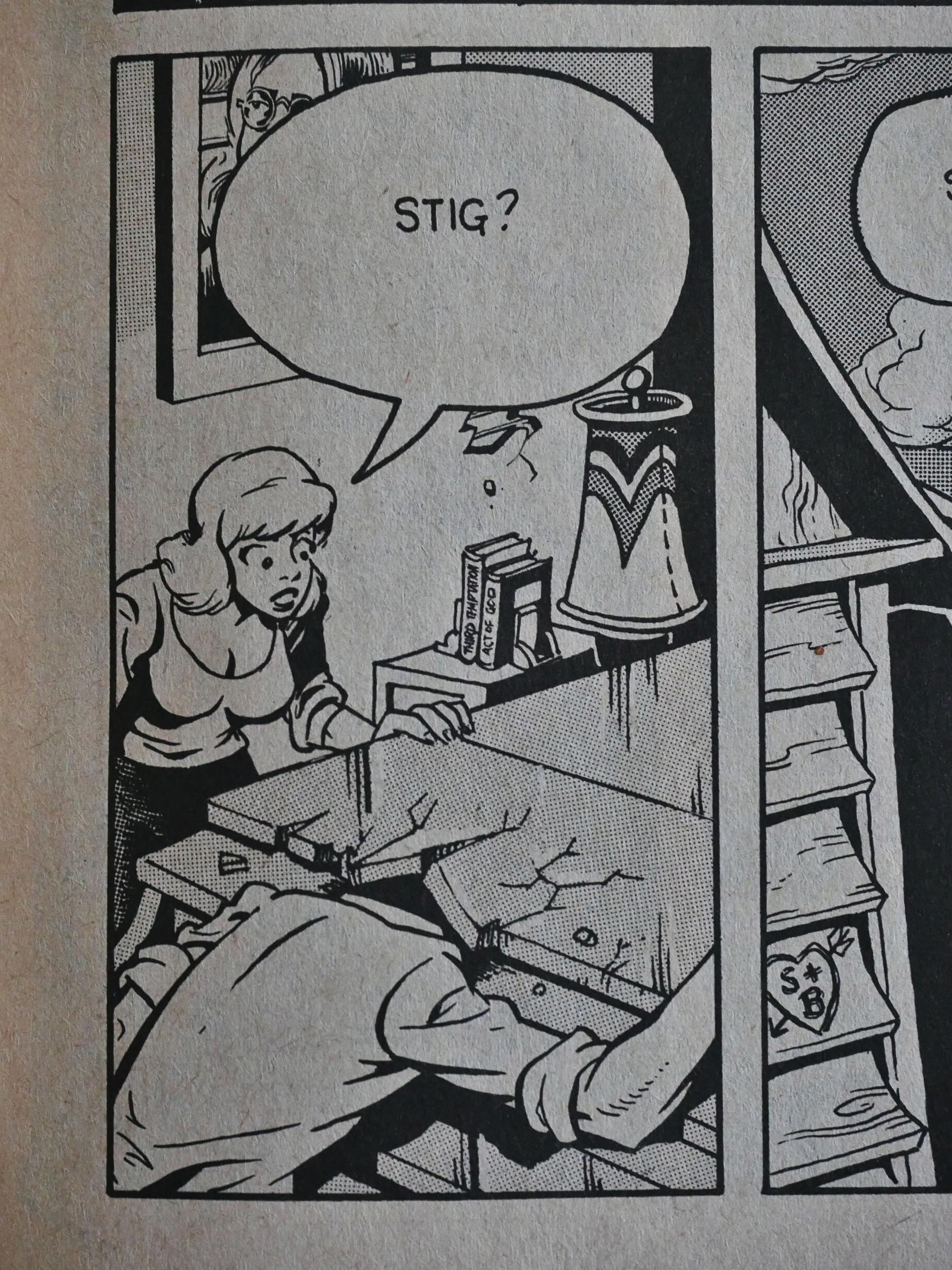

Reading this now, I’m finding it hard to guess whether Templeton had any plan with this book beyond the central premise. He’s got a pretty large cast that contribute to several plot threads, and since there are so few pages to develop them in (and not to mention the gags and the jokes), some of them don’t get very far.

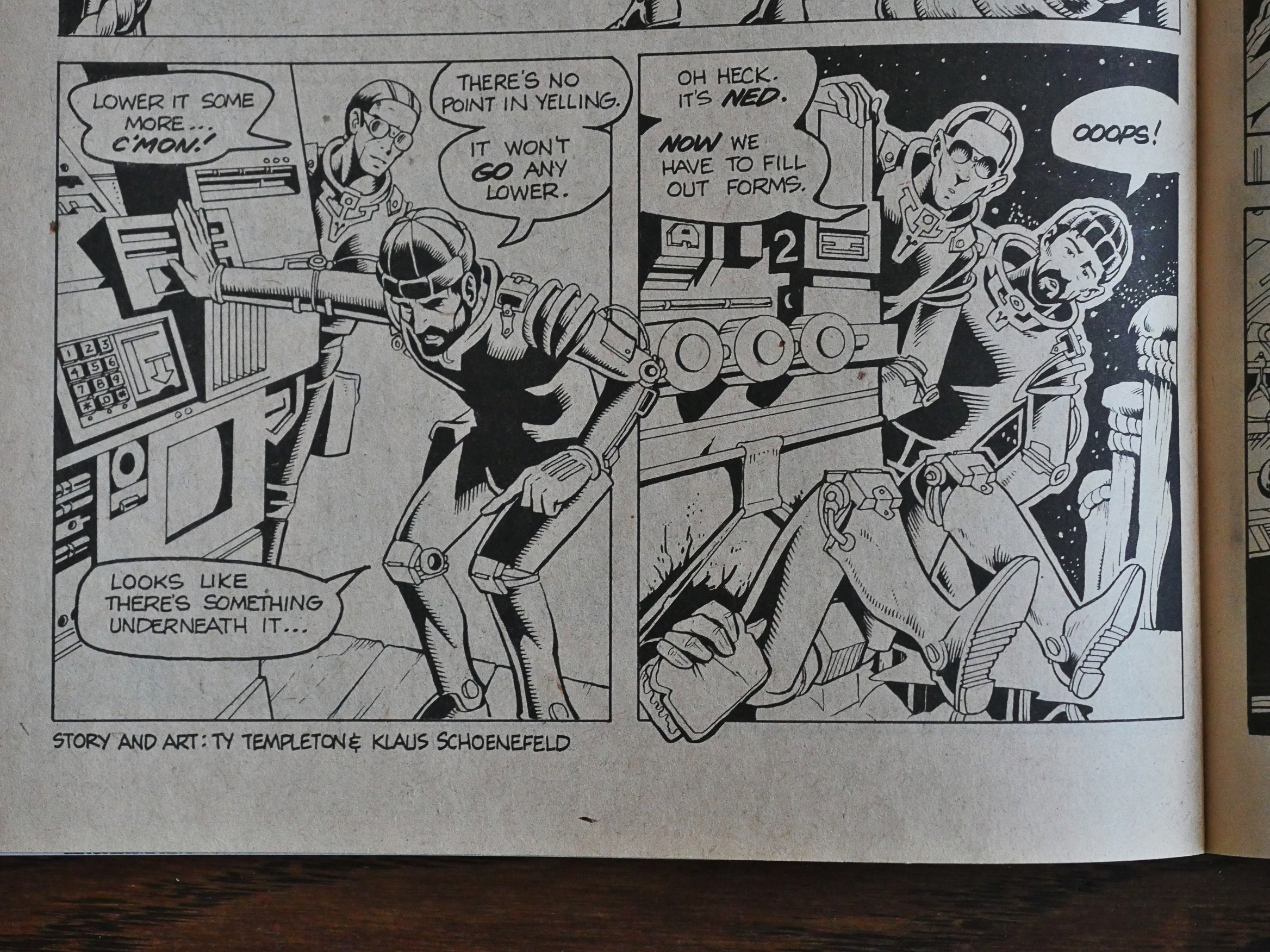

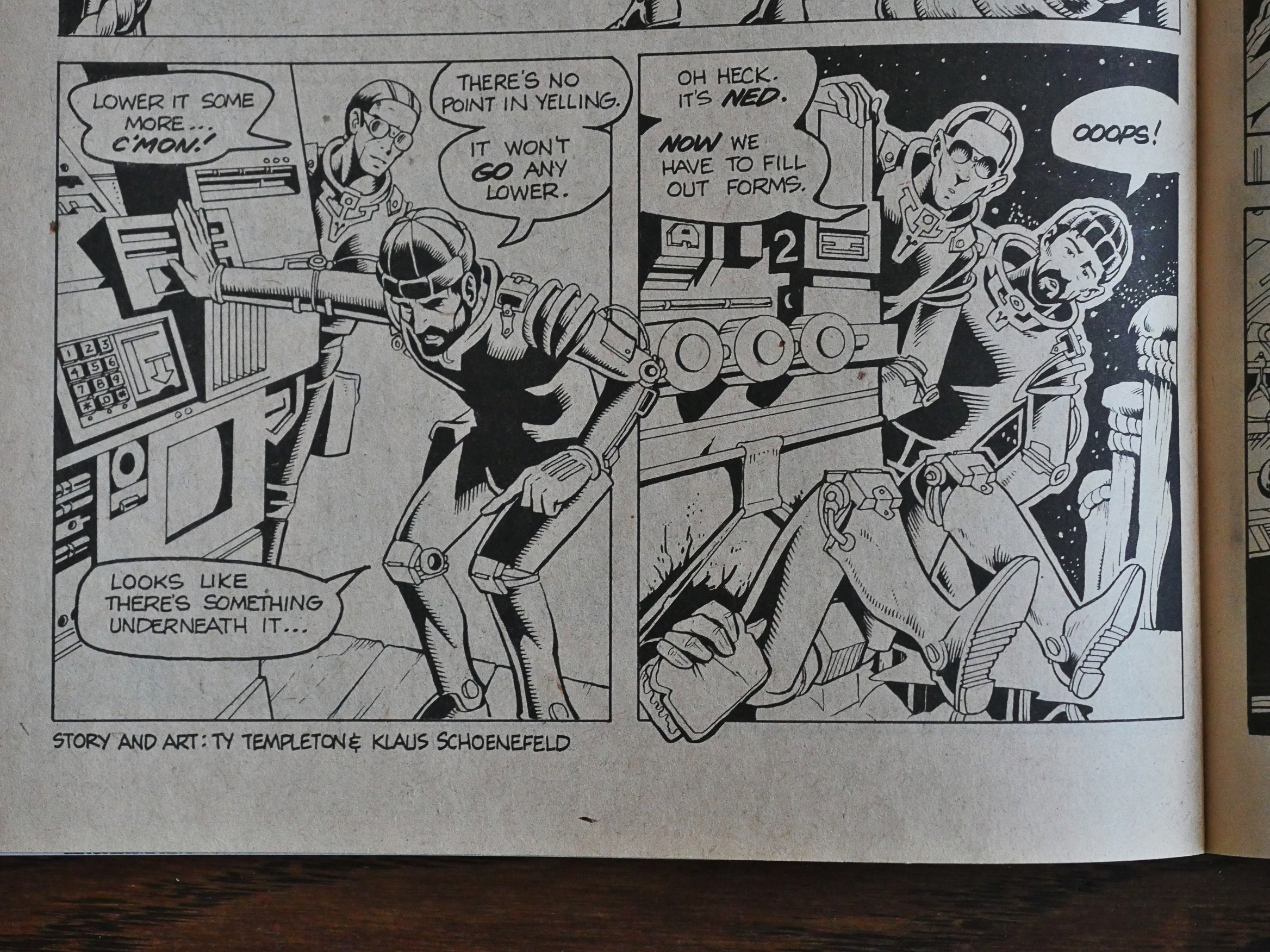

Templeton’s entry into comics apparently made Schoenefeld reconsider his retirement from the field, and he collaborated on the art on a couple of backup features. (As well as starting his own series, Kelvin Mace.)

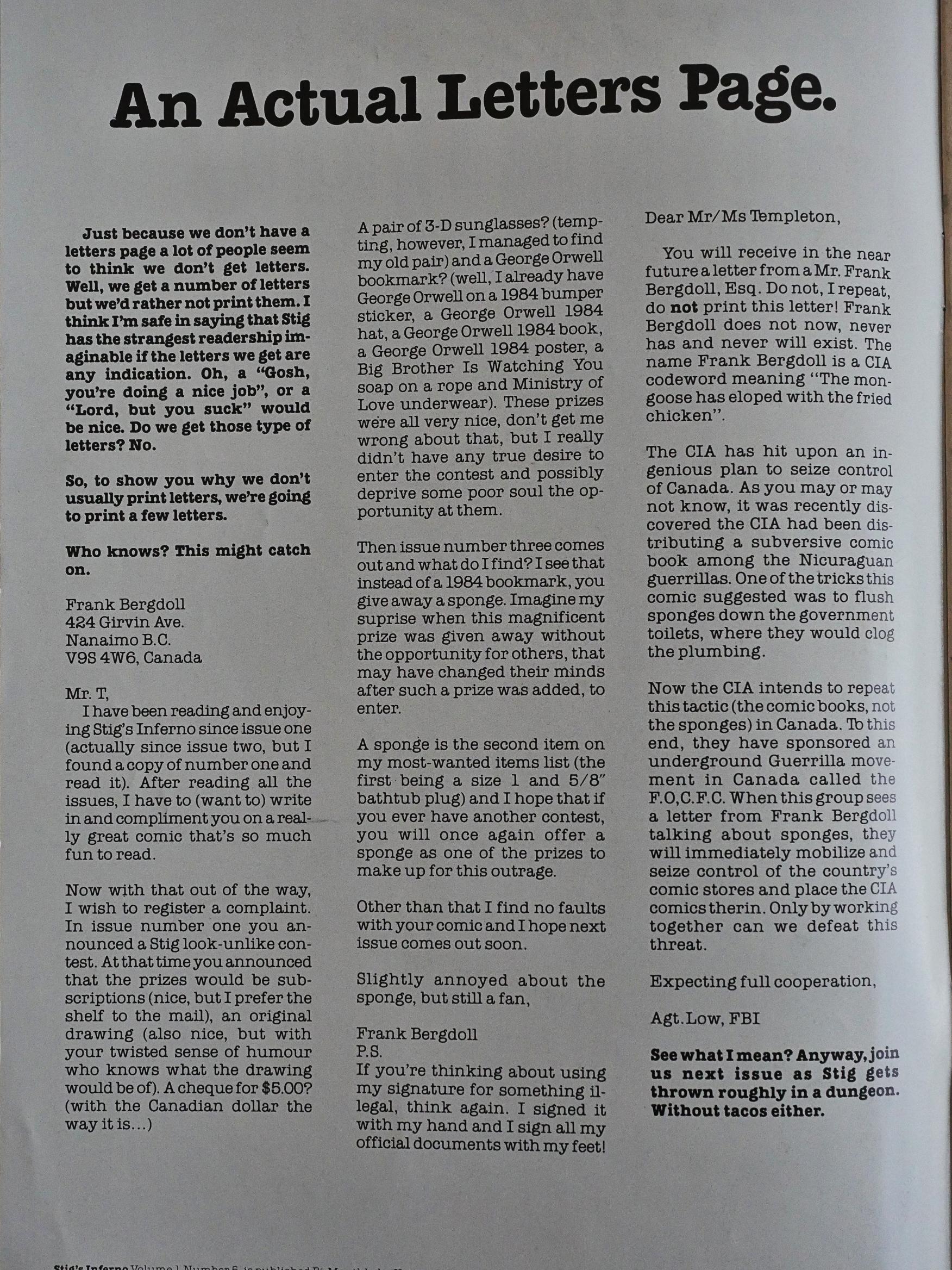

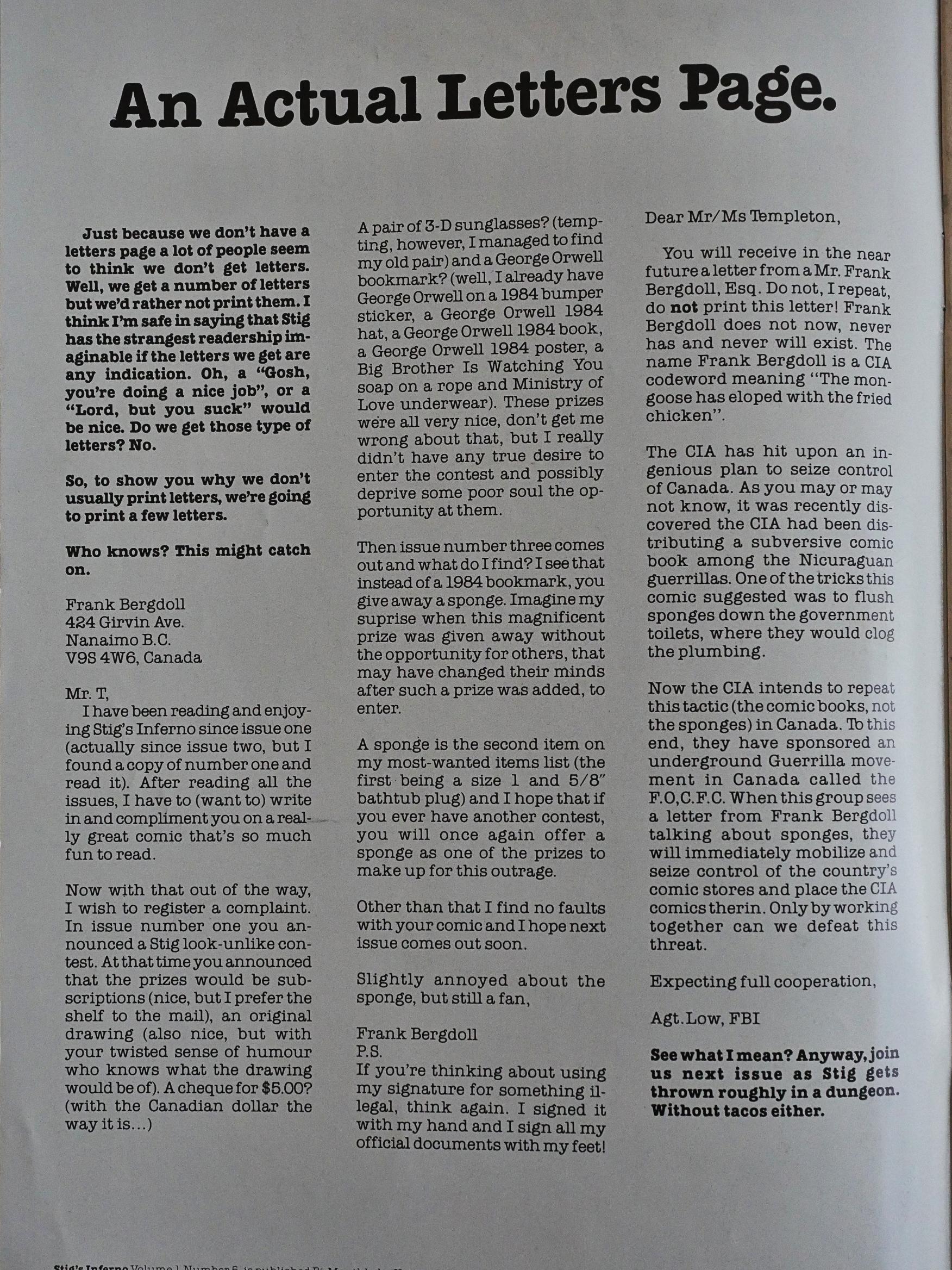

Templeton complained (perhaps facetiously) about the weirdness of the letters he’s getting, but that’s a pretty good one.

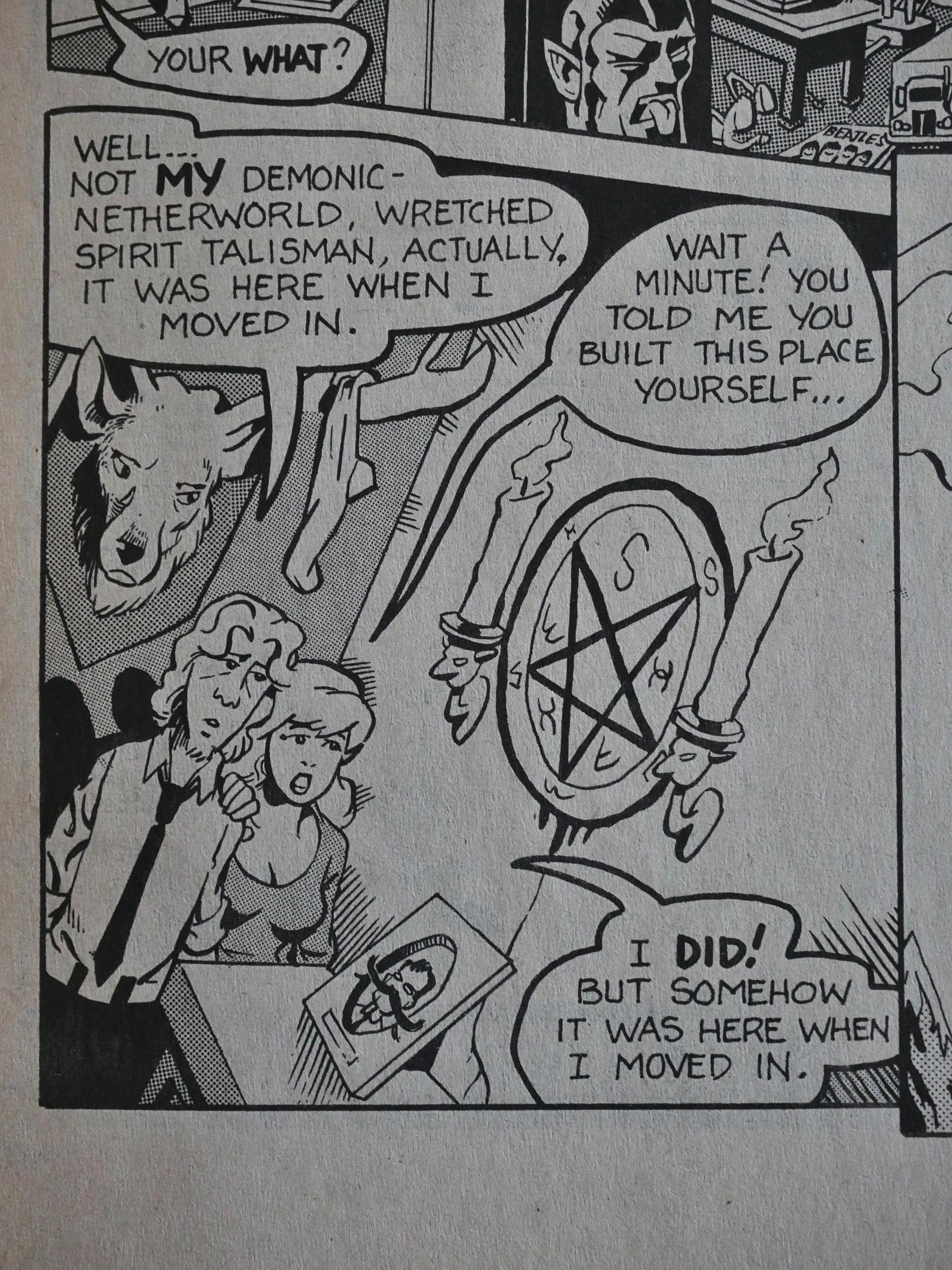

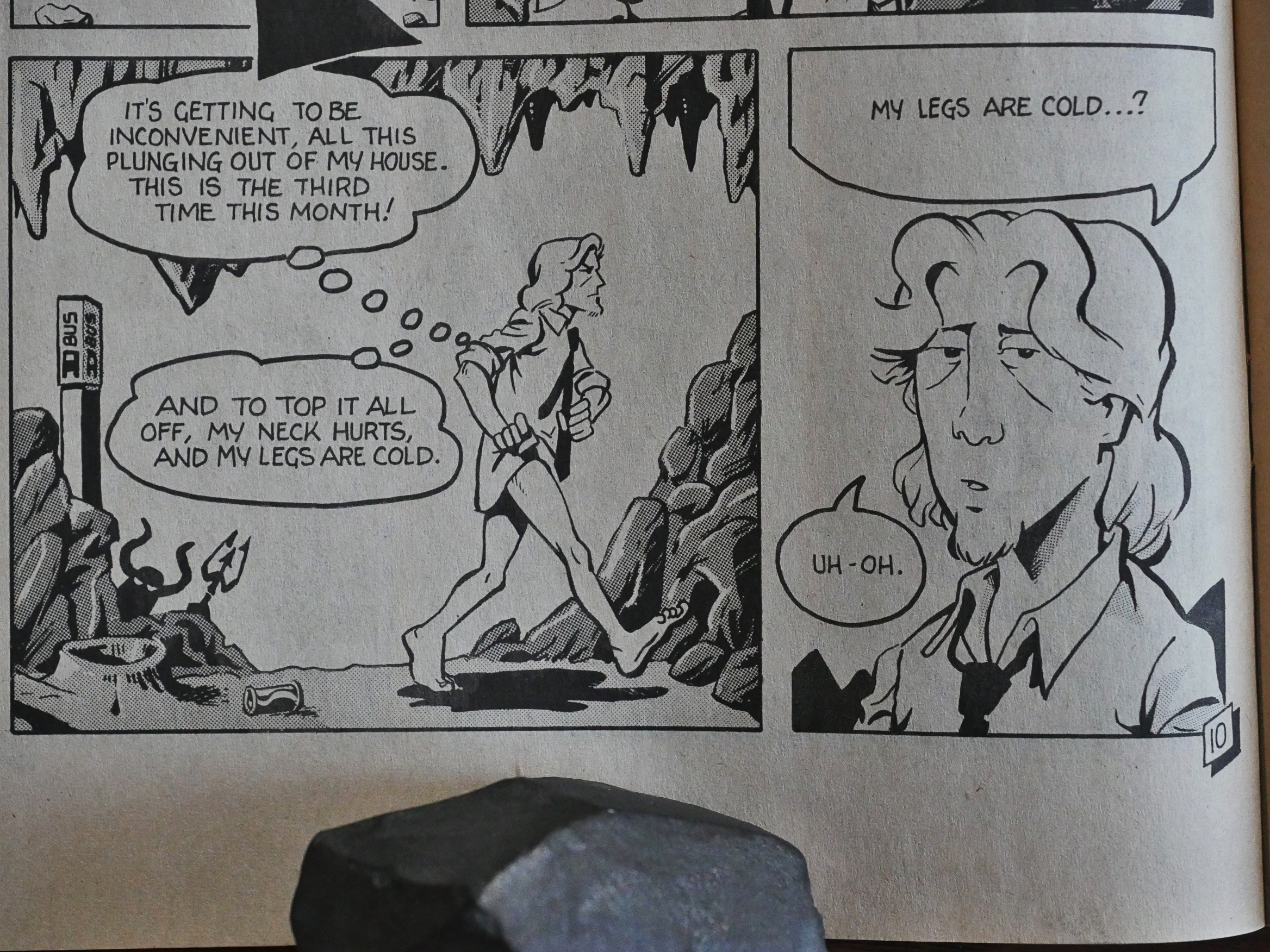

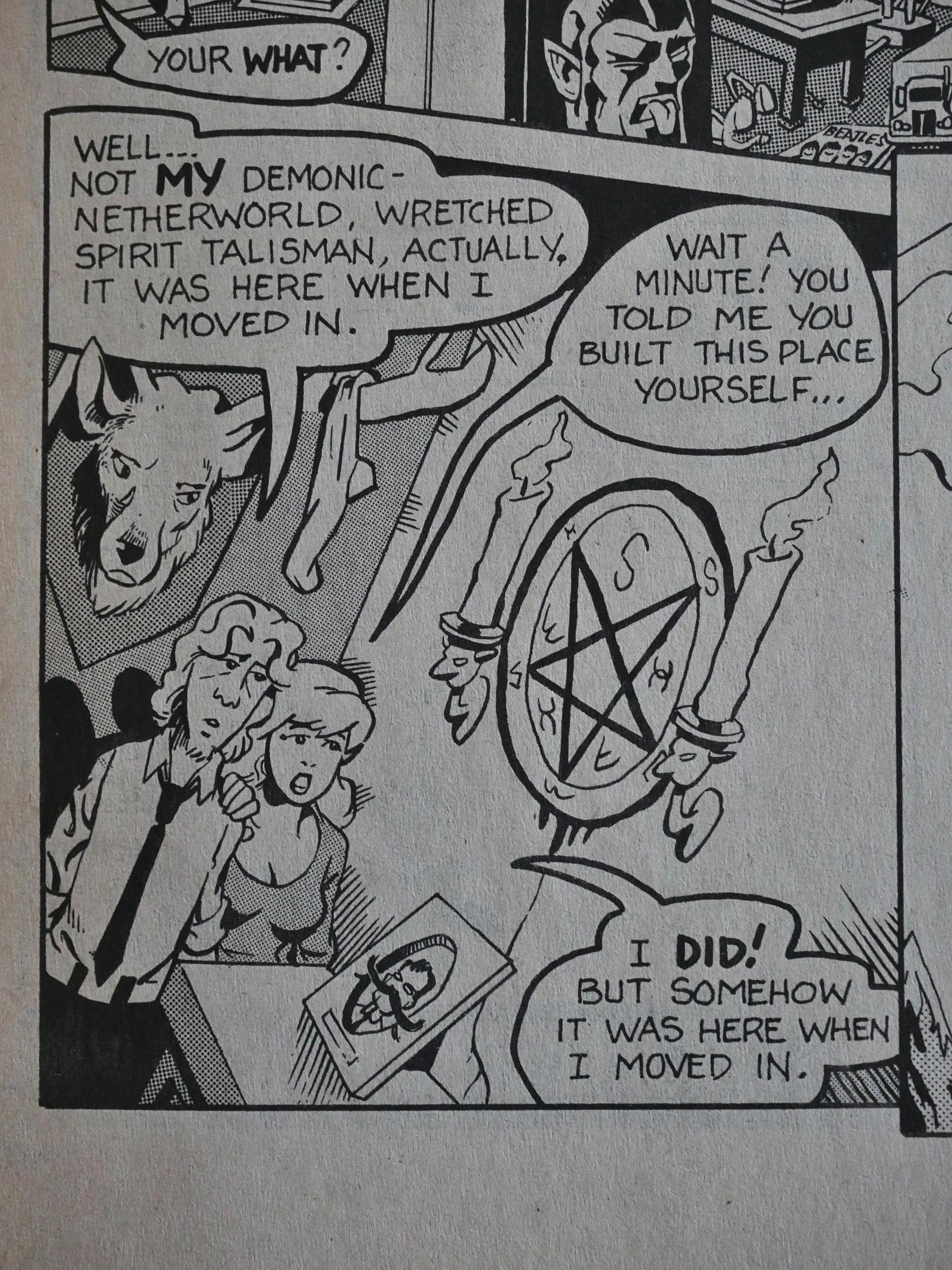

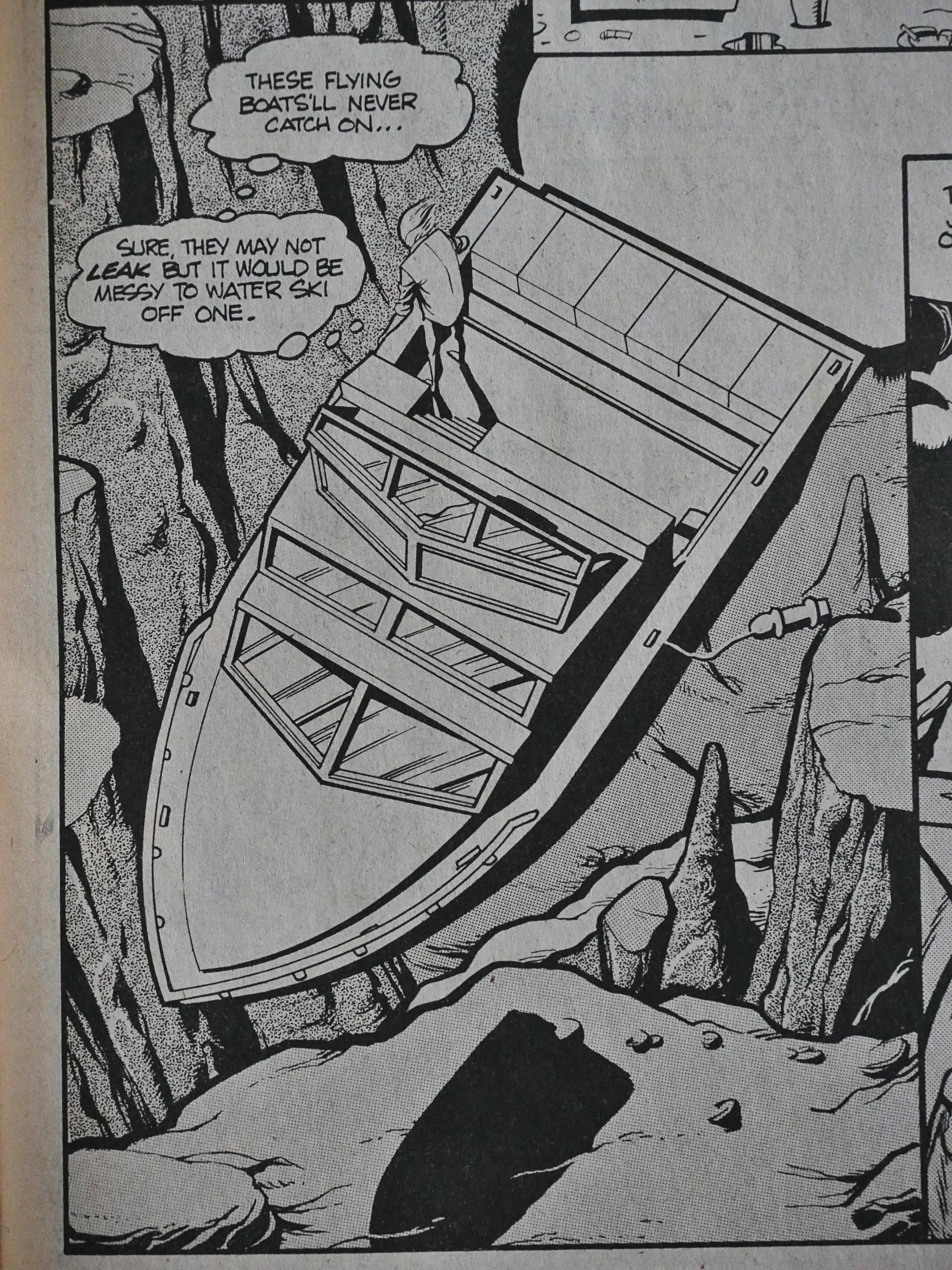

Stuff like this… is this going anywhere, or is it just a random joke? I’m leaning towards random joke, and Templeton not really knowing where he’s doing with it all.

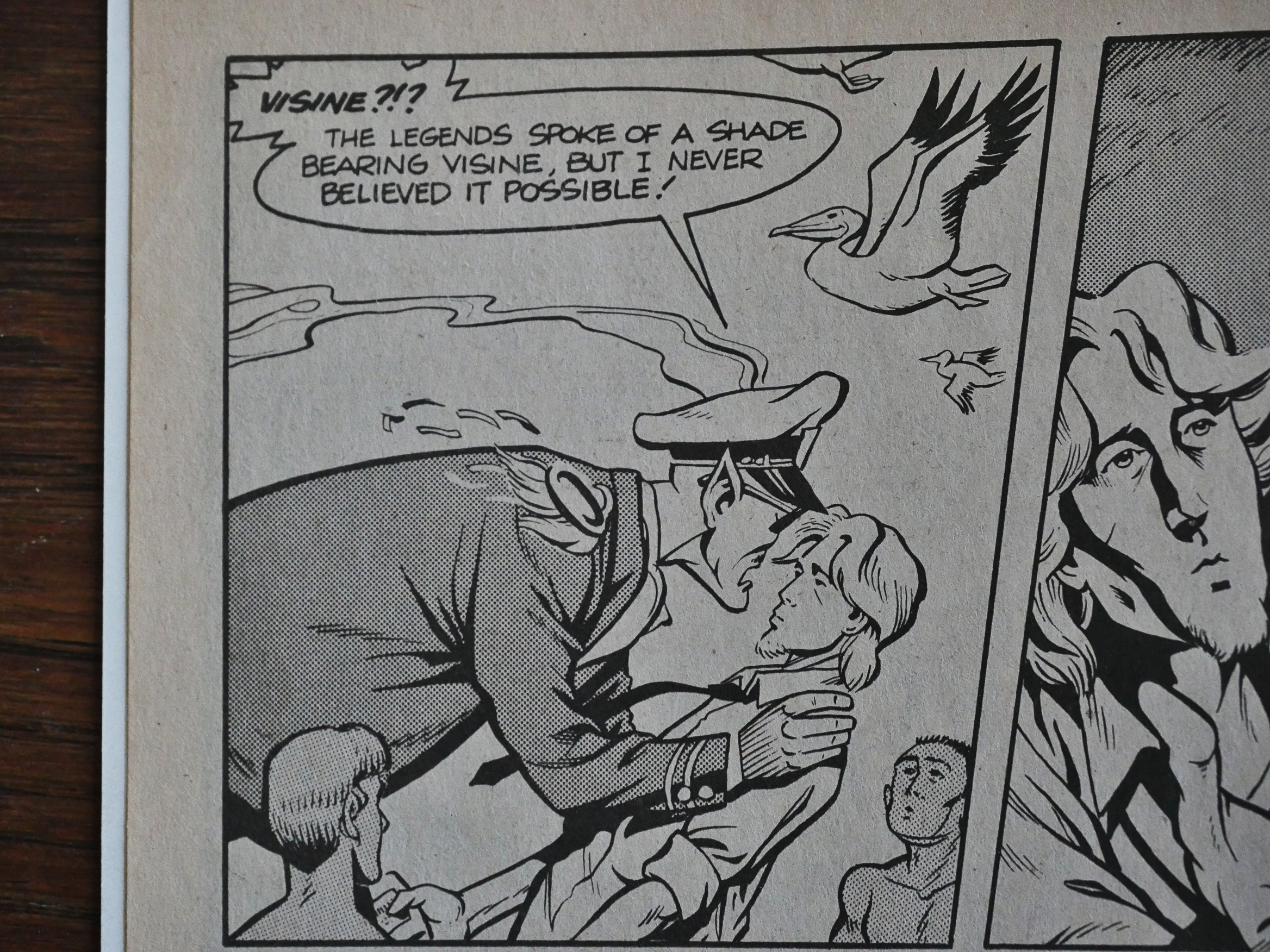

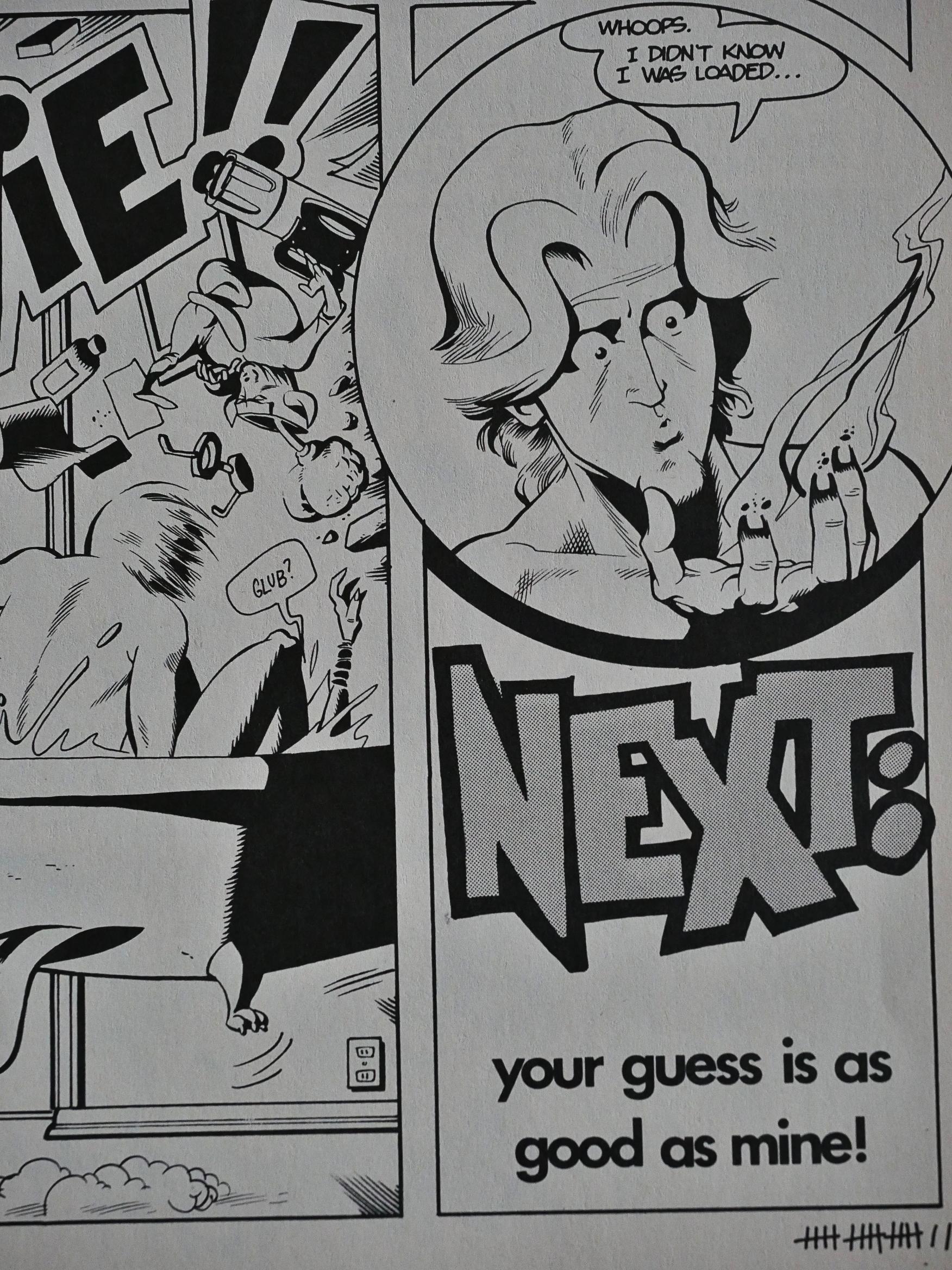

That joke made me laugh out loud. It’s just so stupid.

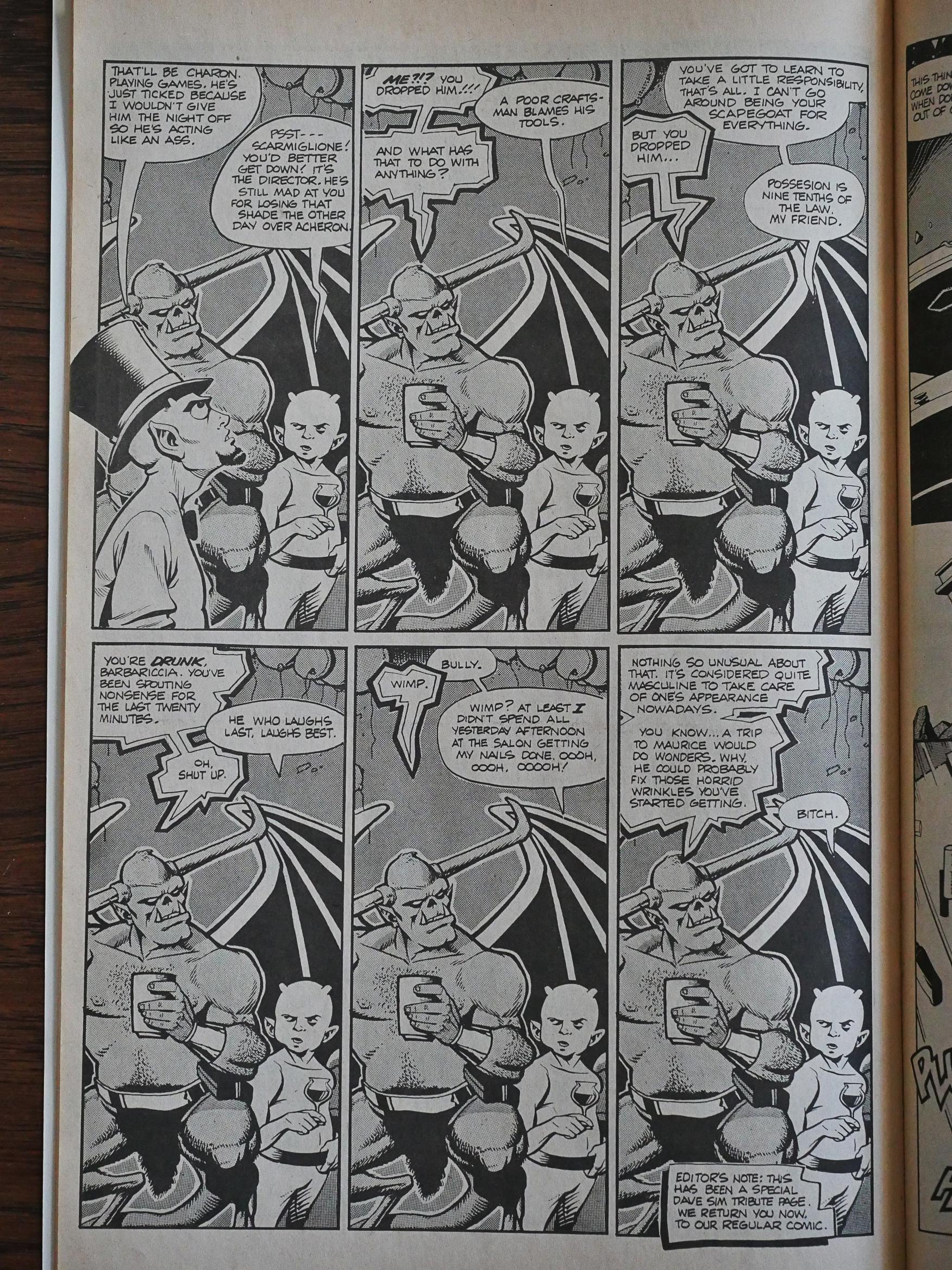

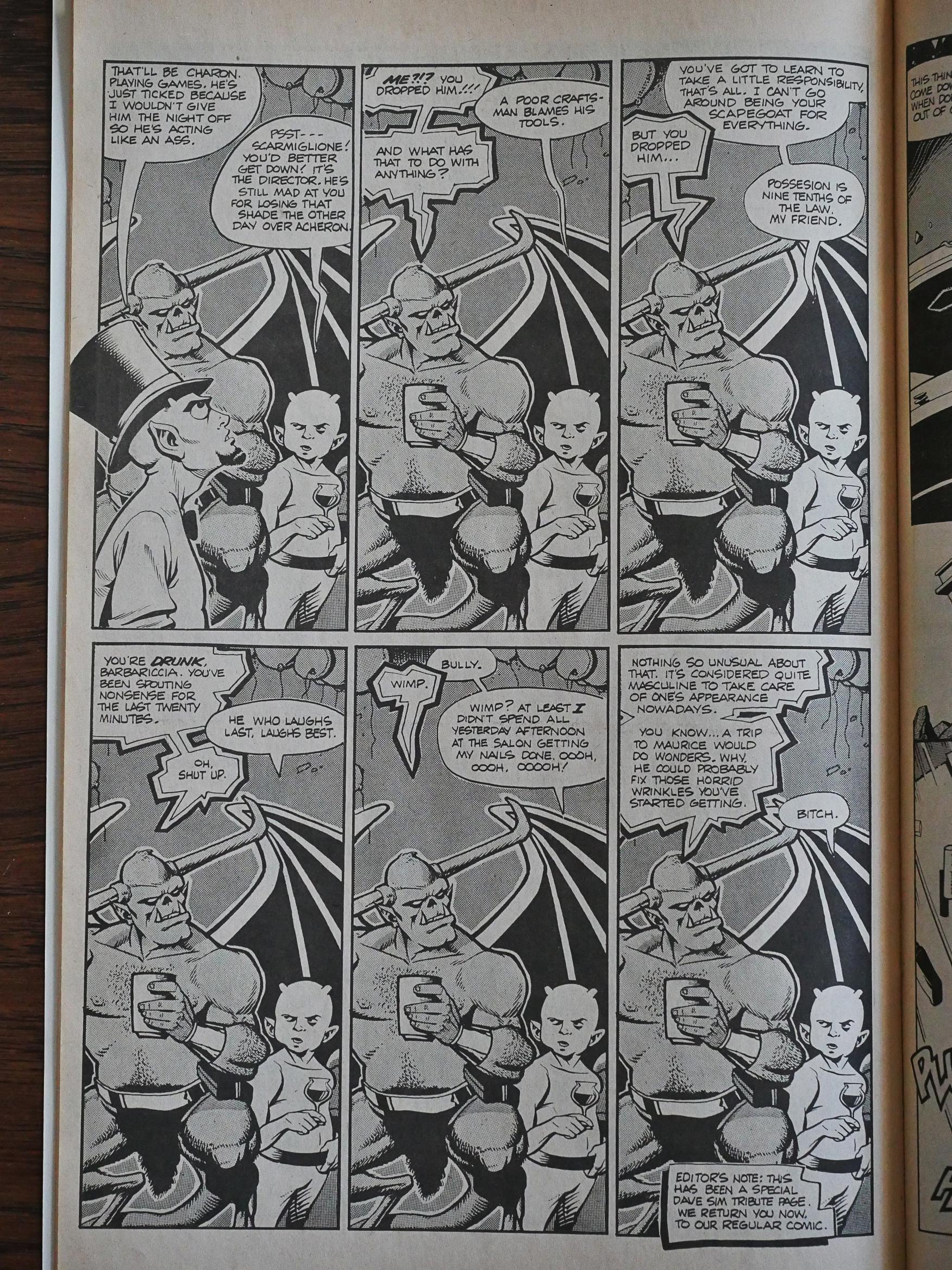

Templeton doesn’t indulge in much “fourth wall” humour (i.e., mentioning that we’re in a comic book), but that’s a nice commentary on Dave Sim’s Cerebus, which was using photocopying a lot as an effect around this time.

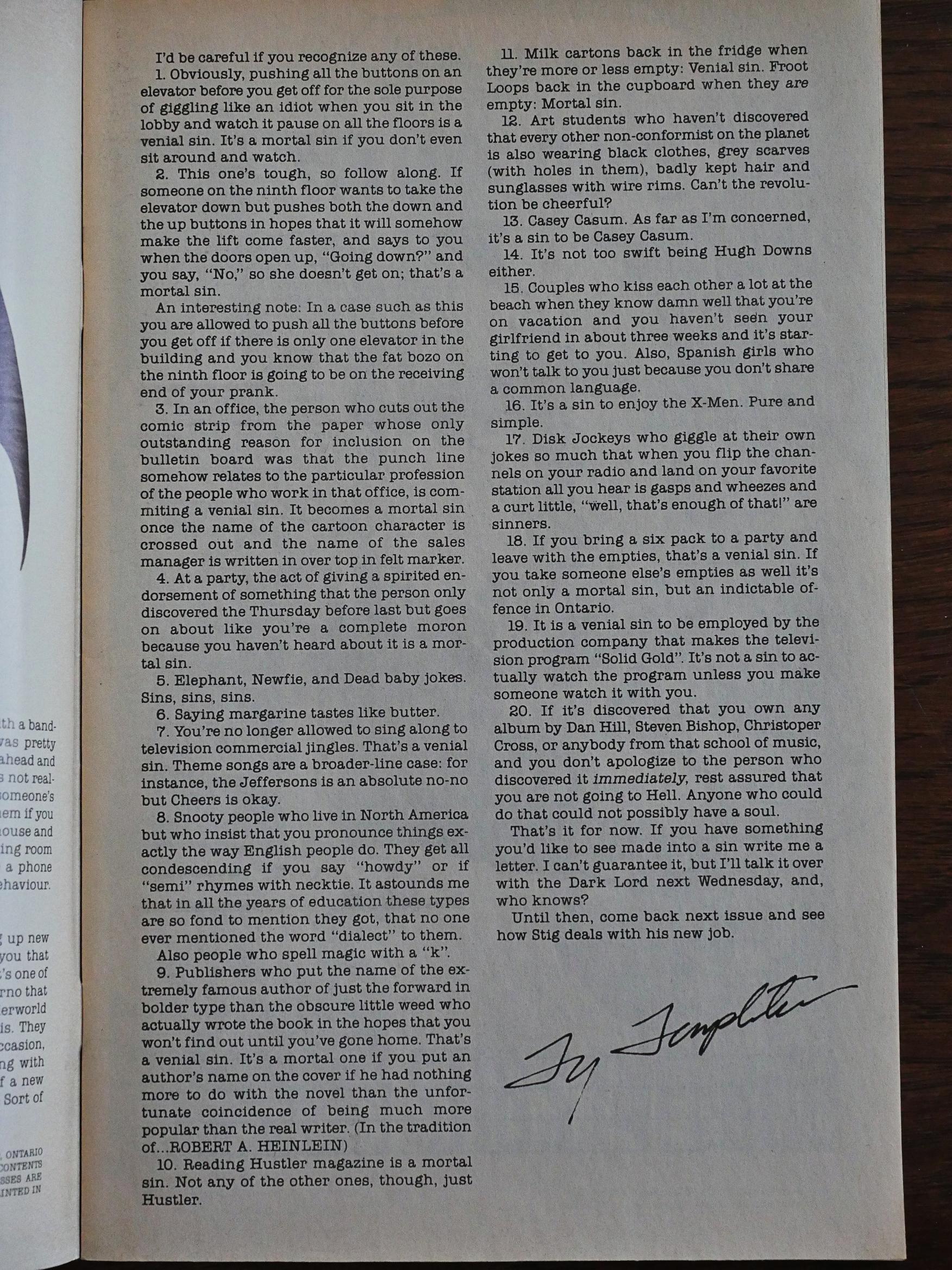

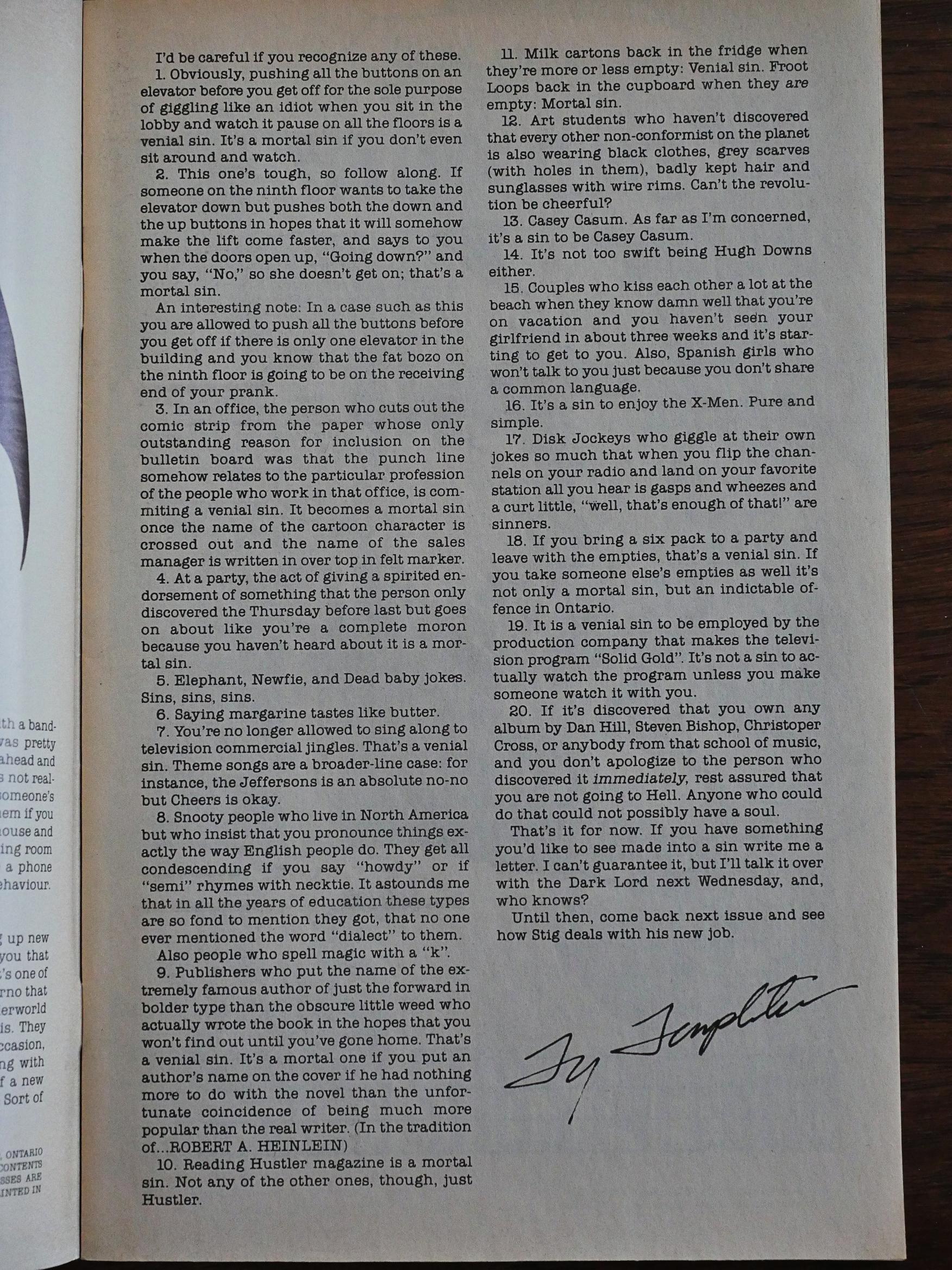

I think I agree with most of Templeton’s list of deadly and venal sins here, especially the one about hitting both the up and down buttons on elevators.

And then! Eclipse! Templeton had by this time (early 1987) worked for Eclipse on a number of projects, like Adolescent etc and The New Wave. So perhaps it seemed natural for him to restart it there, especially since 1) it’s in black and white and 2) there’s a boom going on.

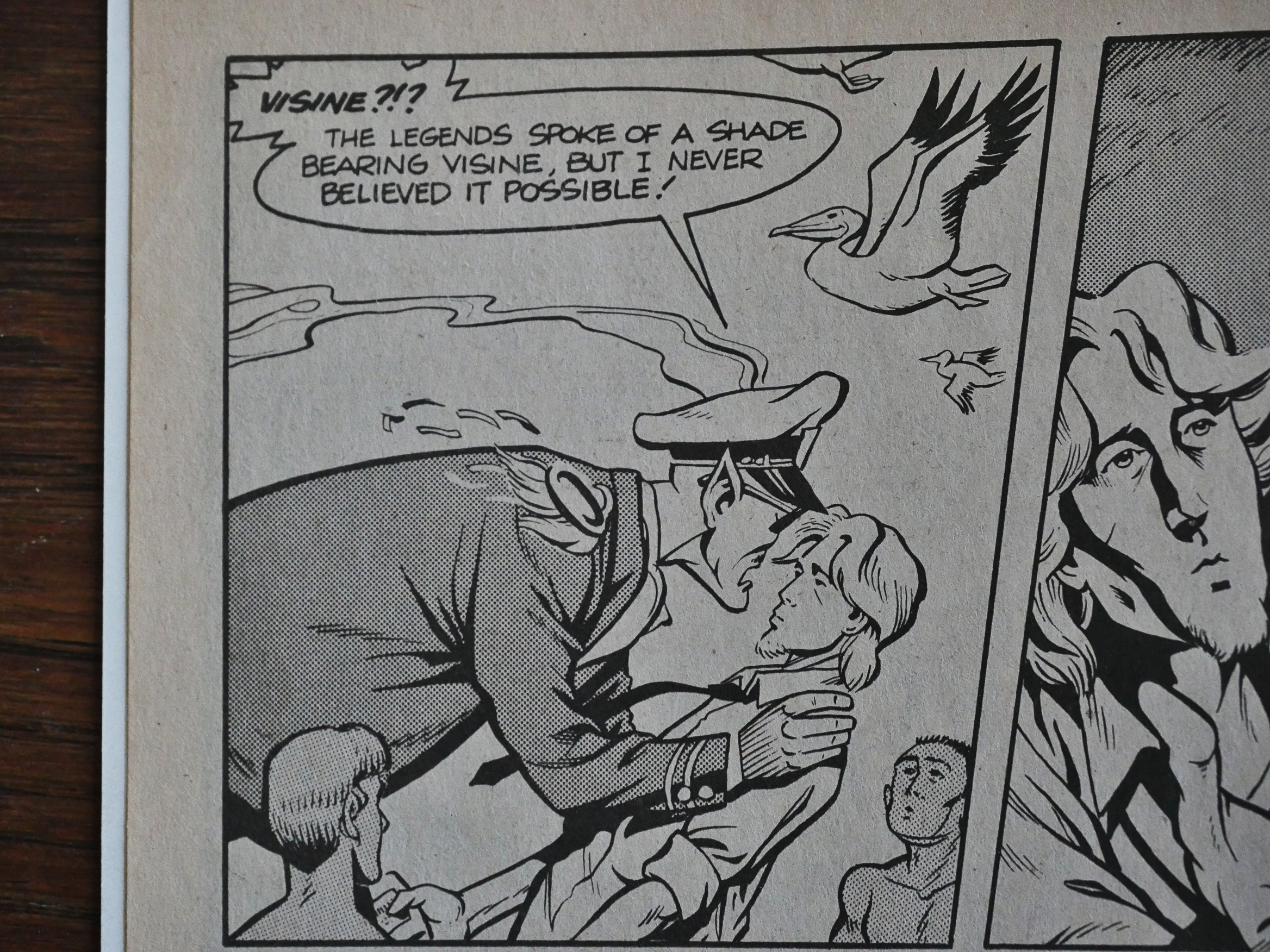

The artwork hasn’t changed a lot in the intervening year(s), but that looks very Mad Magazine.

The first issue’s portion of Stig doesn’t advance the story at all. Instead it’s all recap.

Not only that, but Templeton reprints several pages from the first five issues, lightly modified.

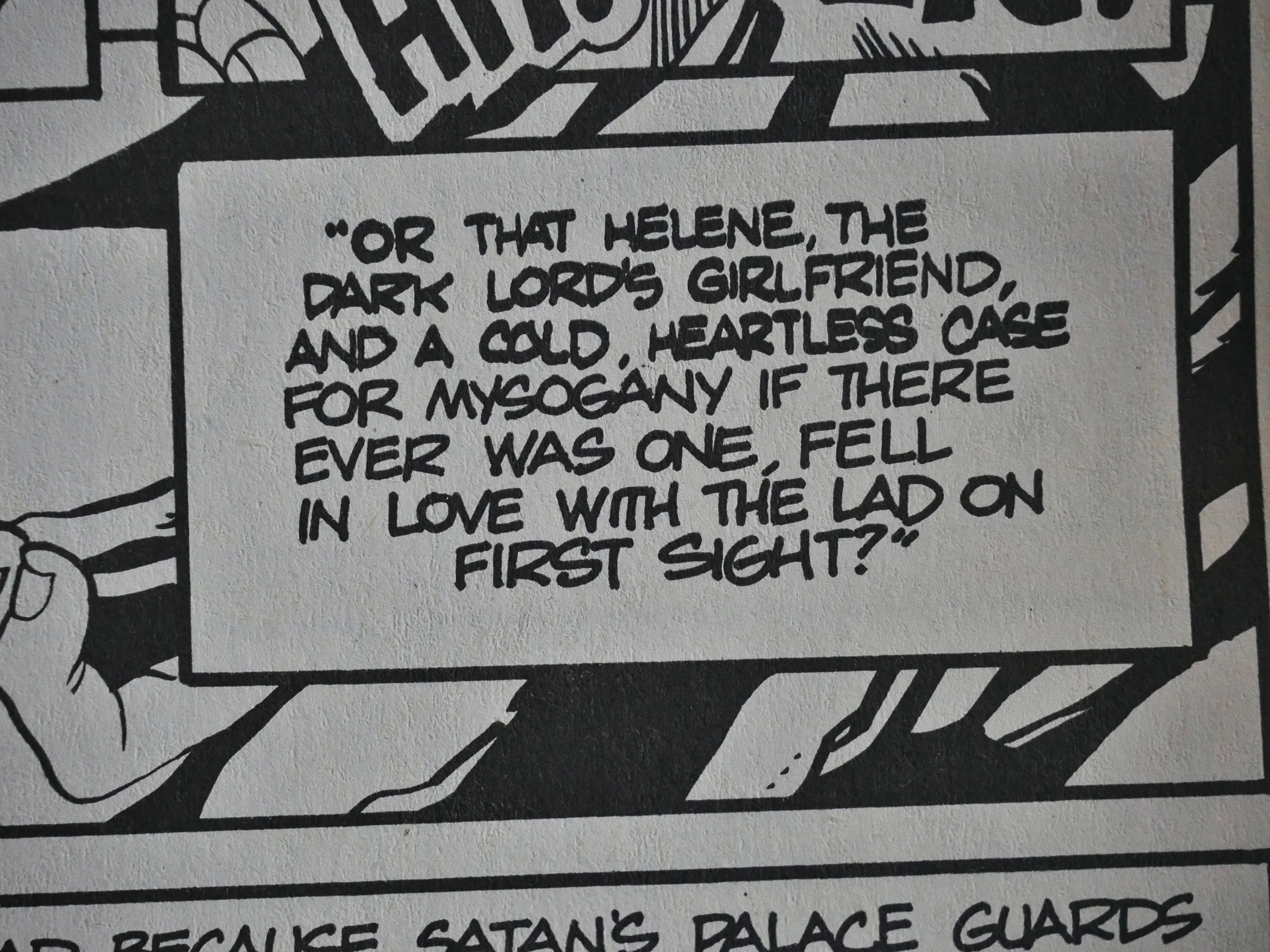

And there’s nobody doing proffreading.

So the first new issue is rather a disappointment.

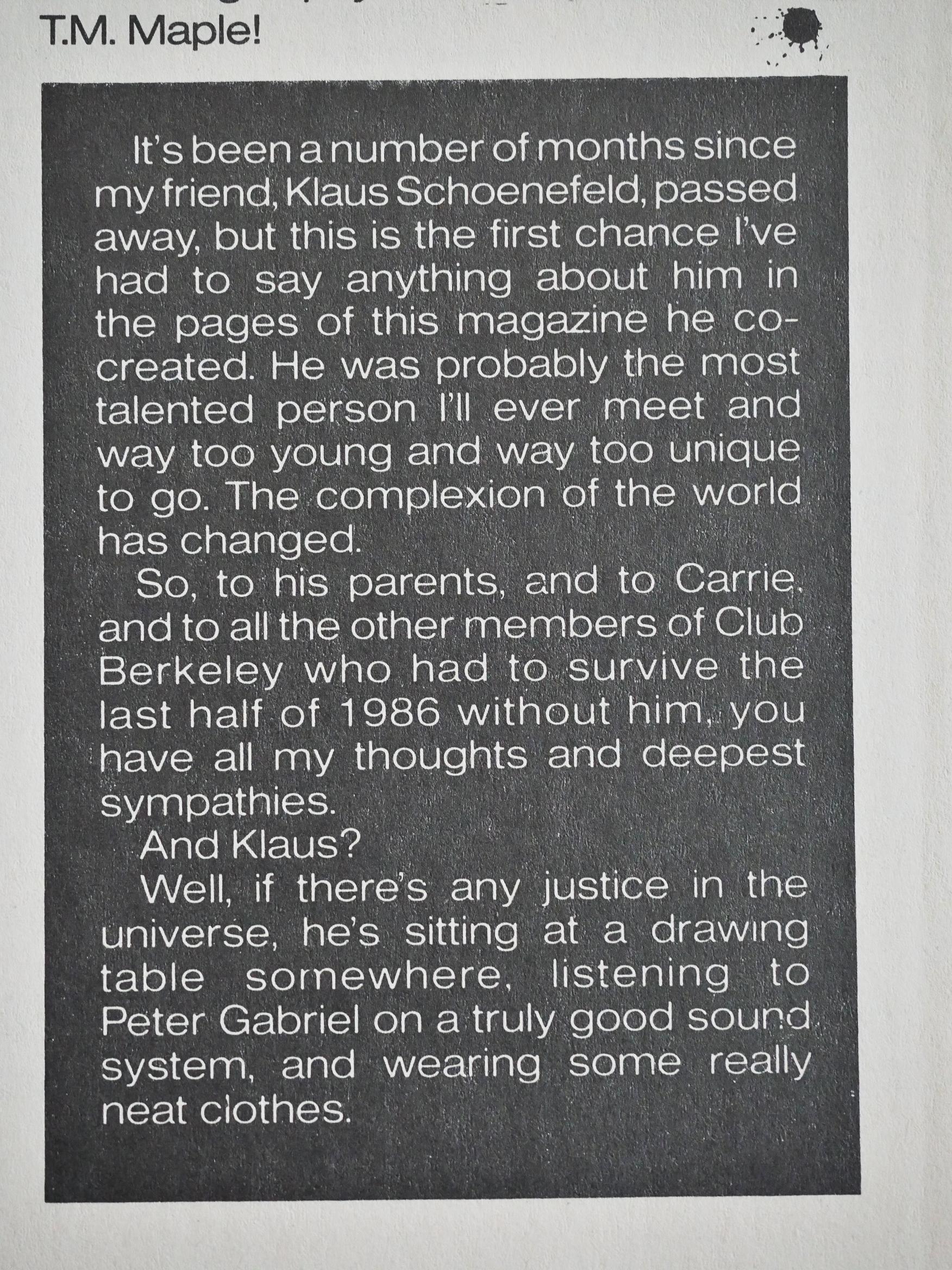

Meanwhile, Stig’s co-creator Klaus Schoenefeld died of a heart attack at only age 25.

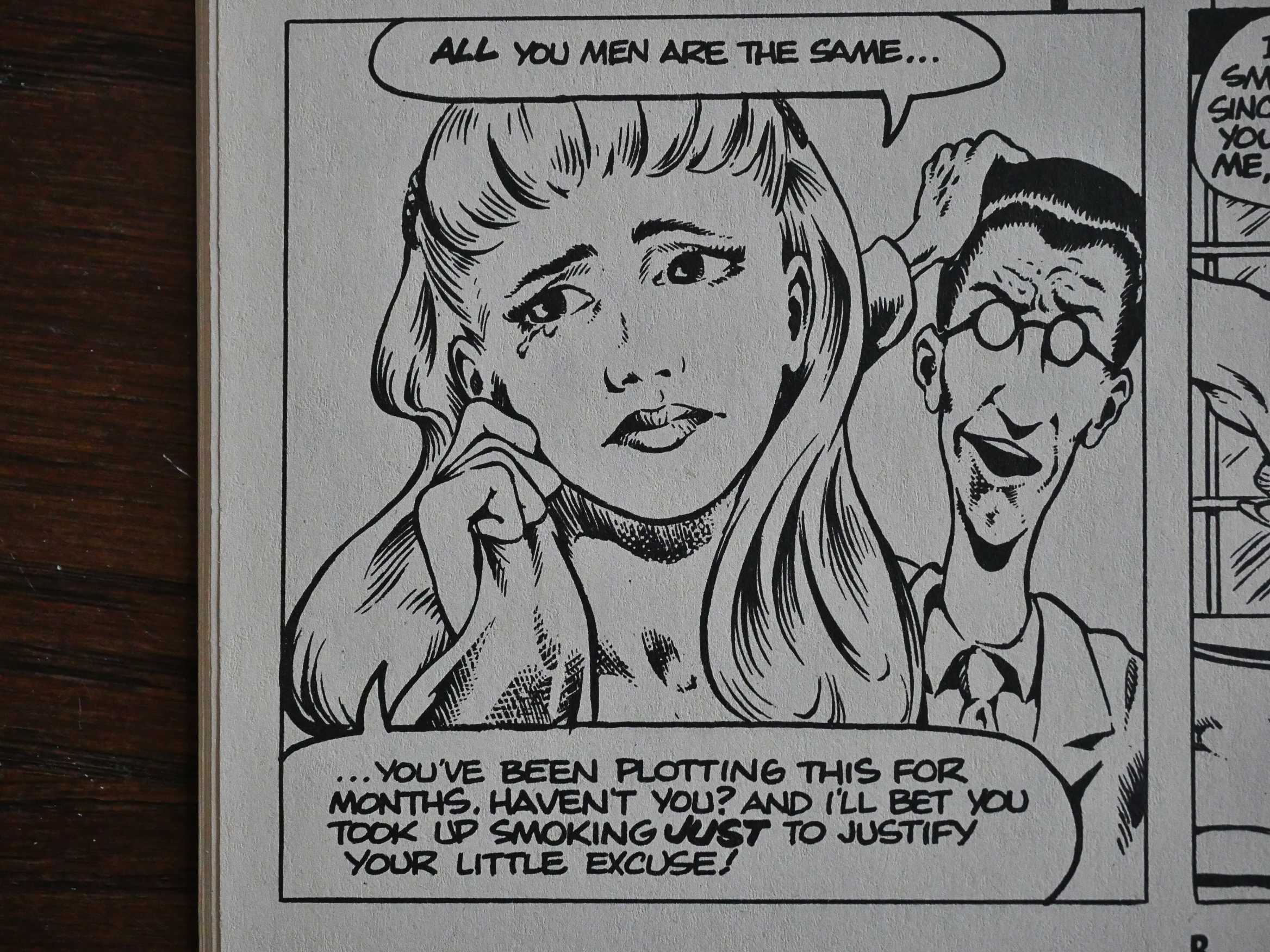

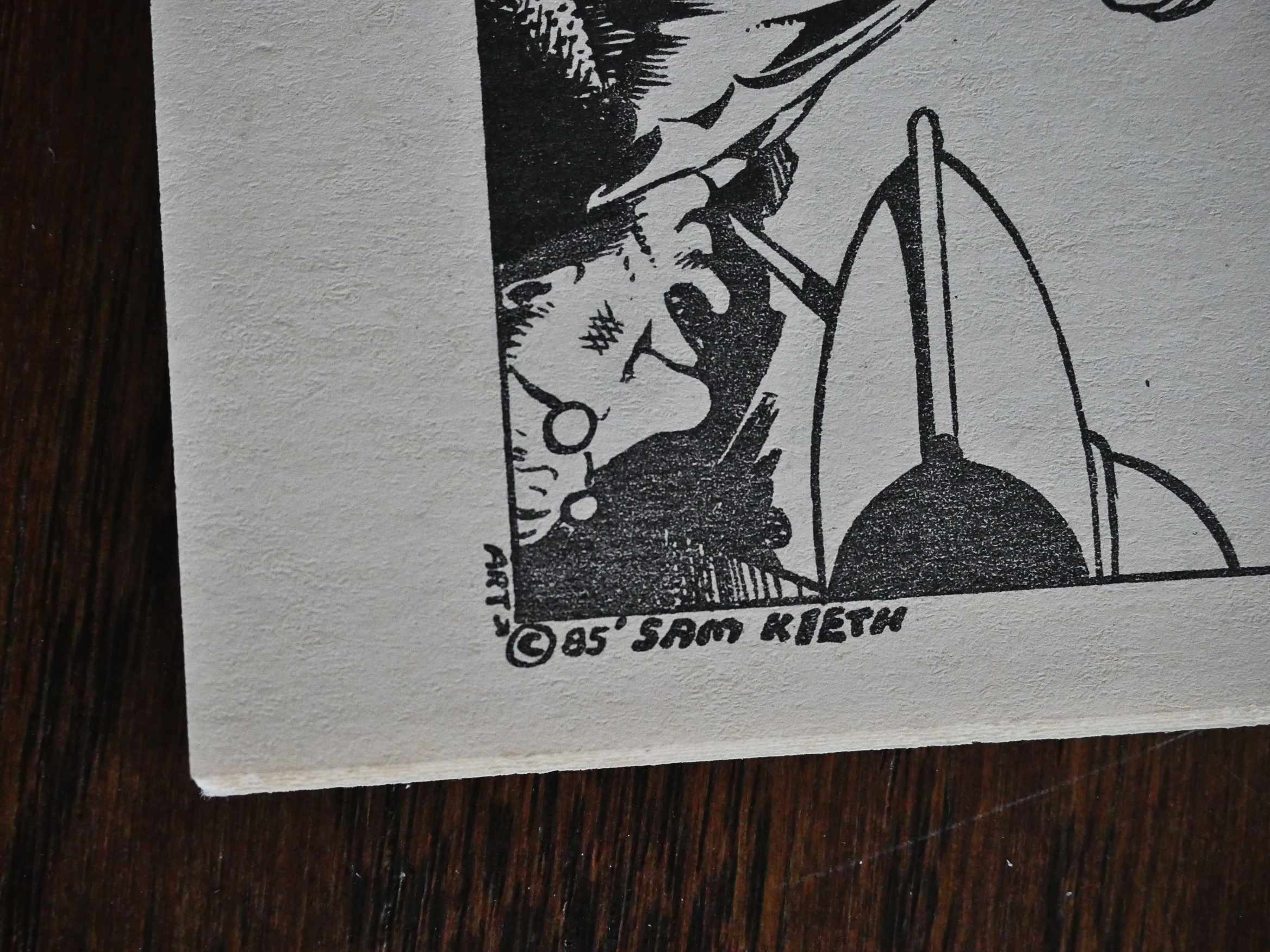

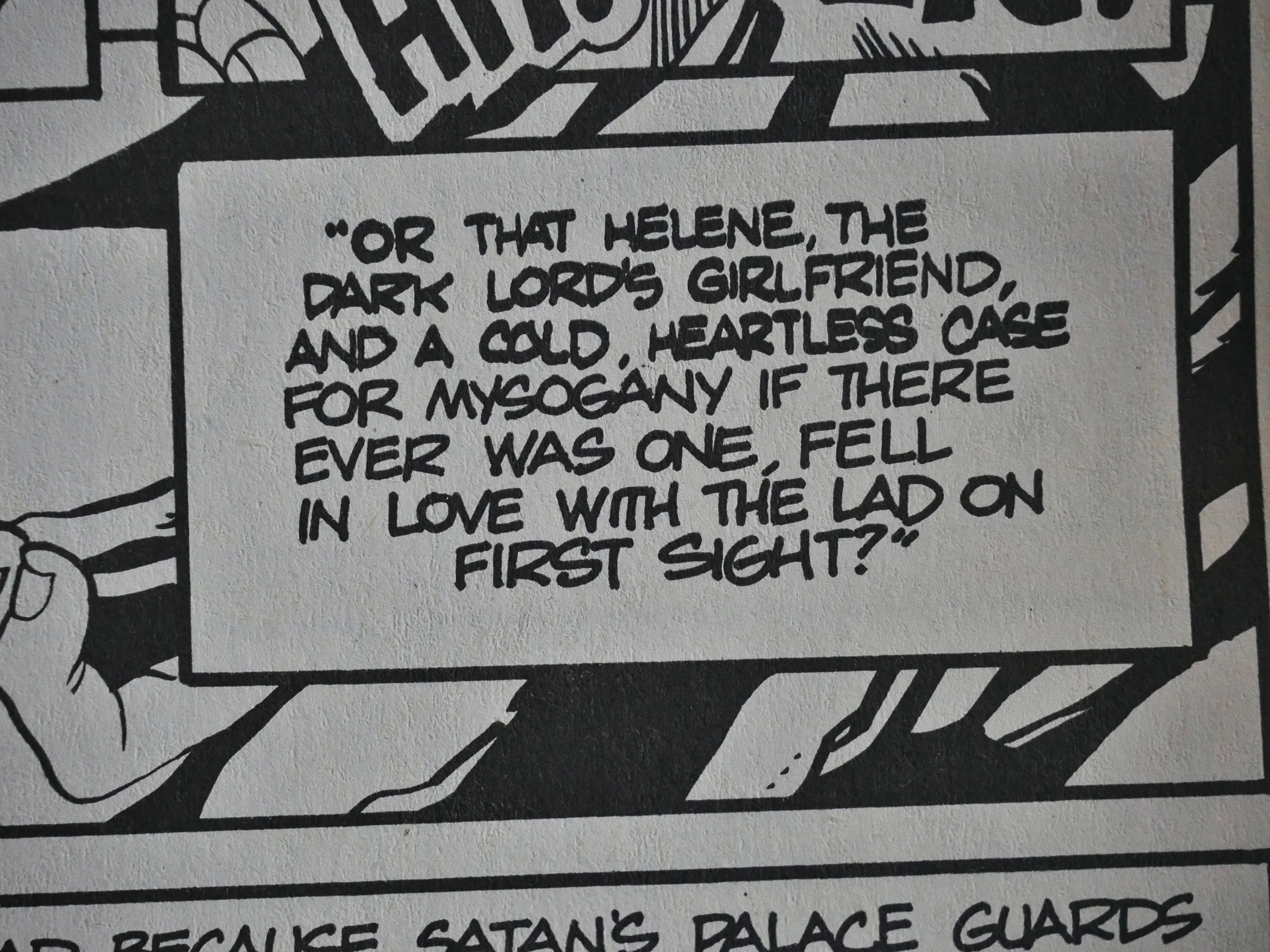

To fill out the first Eclipse issue, we have a Sam Kieth-drawn monster/romance parody.

Kieth is probably aping Dave Stevens here in his rather handsome rendering of women.

Oh, so this is from 1985? It’s a piece they had floating around they jammed into this book? It’s funny, anyway.

I don’t mind these filler pages: They give the book a grab bag feel; some surprises are good and some aren’t, but it’s certainly better than filling up pages with house ads.

Finally! In the second Eclipse issue Templeton advances the er plot.

There’s a surprising amount of it, too: It probably the most text-heavy issue in the series.

And then it’s over. Perhaps Templeton didn’t really have a plan?

c! c!

Vortex reprinted the Vortex issues of Stig’s Inferno in one volume, but the series has never been reprinted as a whole, and hasn’t been continued anywhere that I’m aware of. And you kinda see why: Even if it’s beautifully rendered and quite funny, it just doesn’t go anywhere. It’s weird that Templeton didn’t just slap a (say) 20 page ending onto it and lightly edit the middle bits. Then he’d have something that I think some people would really like to read.

Templeton has put the entire thing here, so you can read it for free. If, for some reason, you wish to read a recap of the plot, it’s here.

But what did the critics think? I don’t know! I thought it had a bigger presence than it did, because I can’t find a single review of it in The Comics Journal.

But there’s this. Gary Groth talks about his arch nemesis, Eclipse, in his story of the black and white boom (and bust):

Anyway, Eclipse wouldn’t touch black-and-white comics until — you guessed it — the black-and-white explosion. In July 1986, Eclipse published one black-and-white comic (Adolescent Radioactive Black Belt Hamsters); by October Eclipse had announced four titles; in November, six; in February and March, eight each; and by April, they had announced nine. Ty Templeton, whose own black-and-white Stig’s Inferno was published by Eclipse (and was probably the best B&W from Eclipse up to that time), confirms my view that this flurry of publishing activity was so much unprincipled strip-mining. In an Amazing Heroes interview, Templeton said:

I don’t think for a minute that Dean [Mullaney] wanted to publish [Stig’s Inferno] until black-and-whites became really big. Because at no time did we talk about it and then, one day, out of the blue, he just called me and said, “We’ve cleared our schedule, we can do Stig.” I think that’s only because the black-and-white market suddenly looked hot. So I hope that he wants to continue doing it even though black-and-whites are dying out, because if the sales drop down to the point that nobody’s making money, like they did with the Hamsters and the Koalas, he might suddenly go, “We-e-ell, this isn’t the gold mine we thought it was.”

From one of their own creators, Eclipse stands condemned.

I guess that explains the general feeling of not really committing in the two Eclipse issues. They’re filled with all sorts of filler instead of really expanding on the storyline.

Still worth reading.