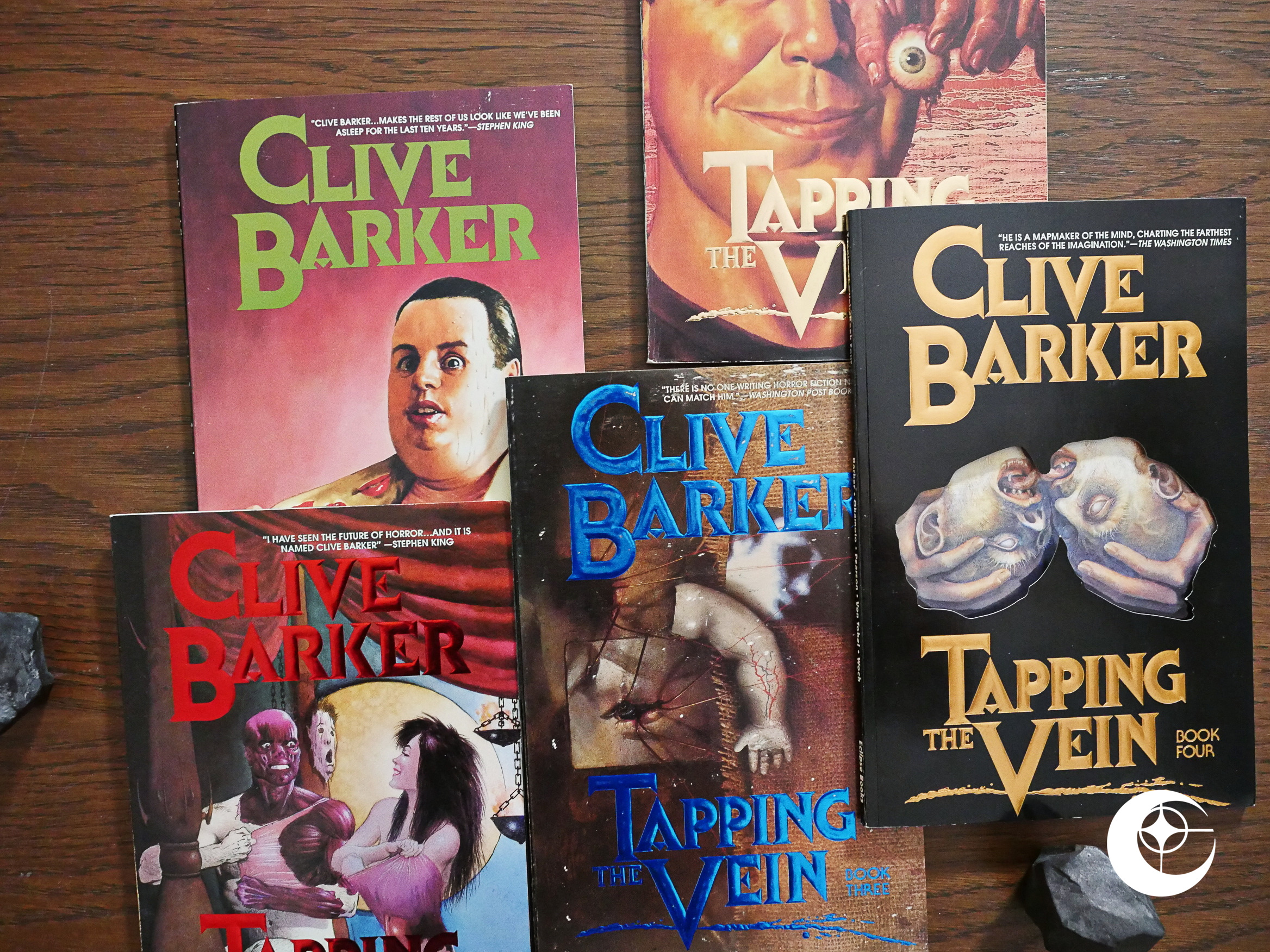

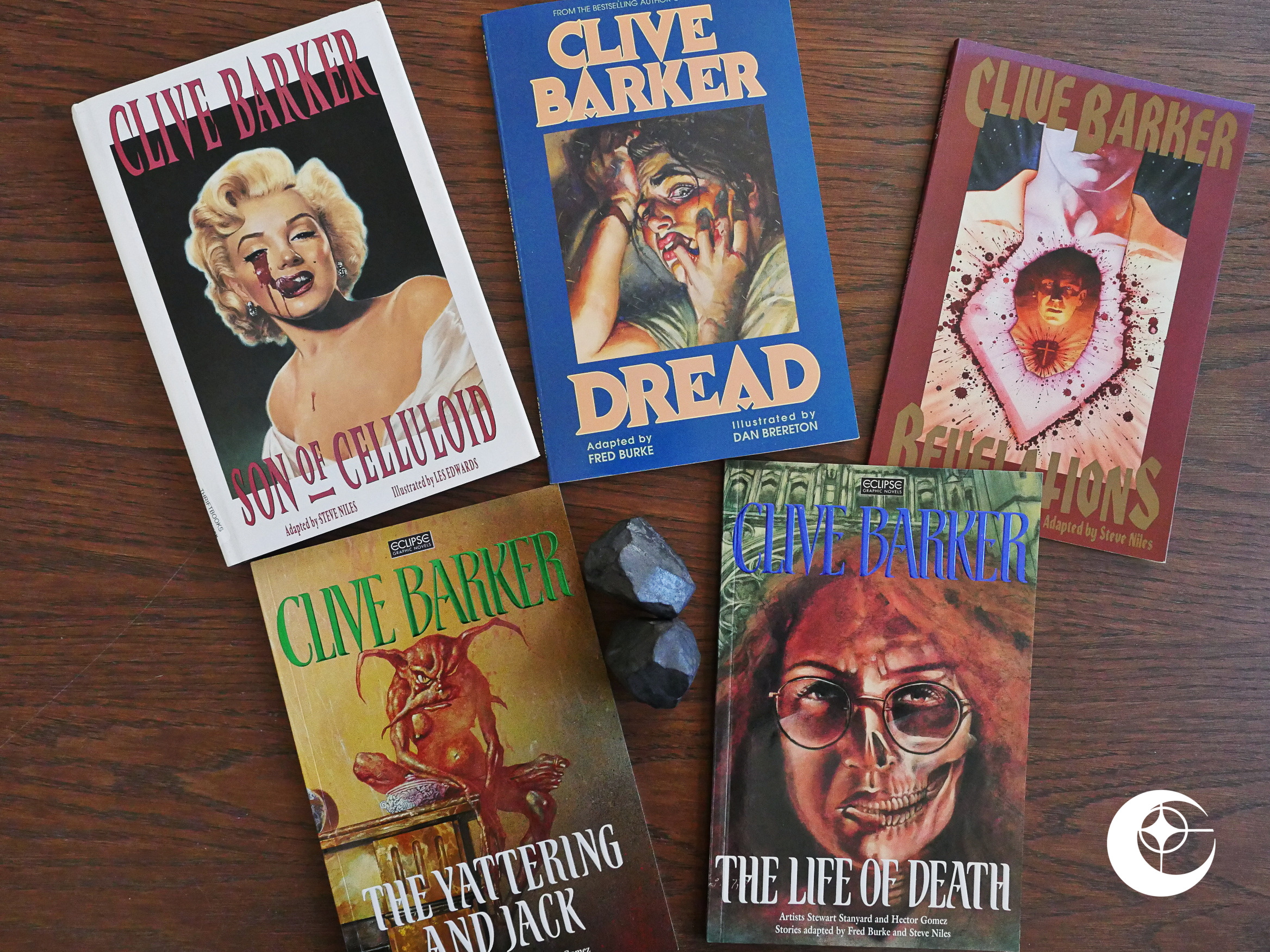

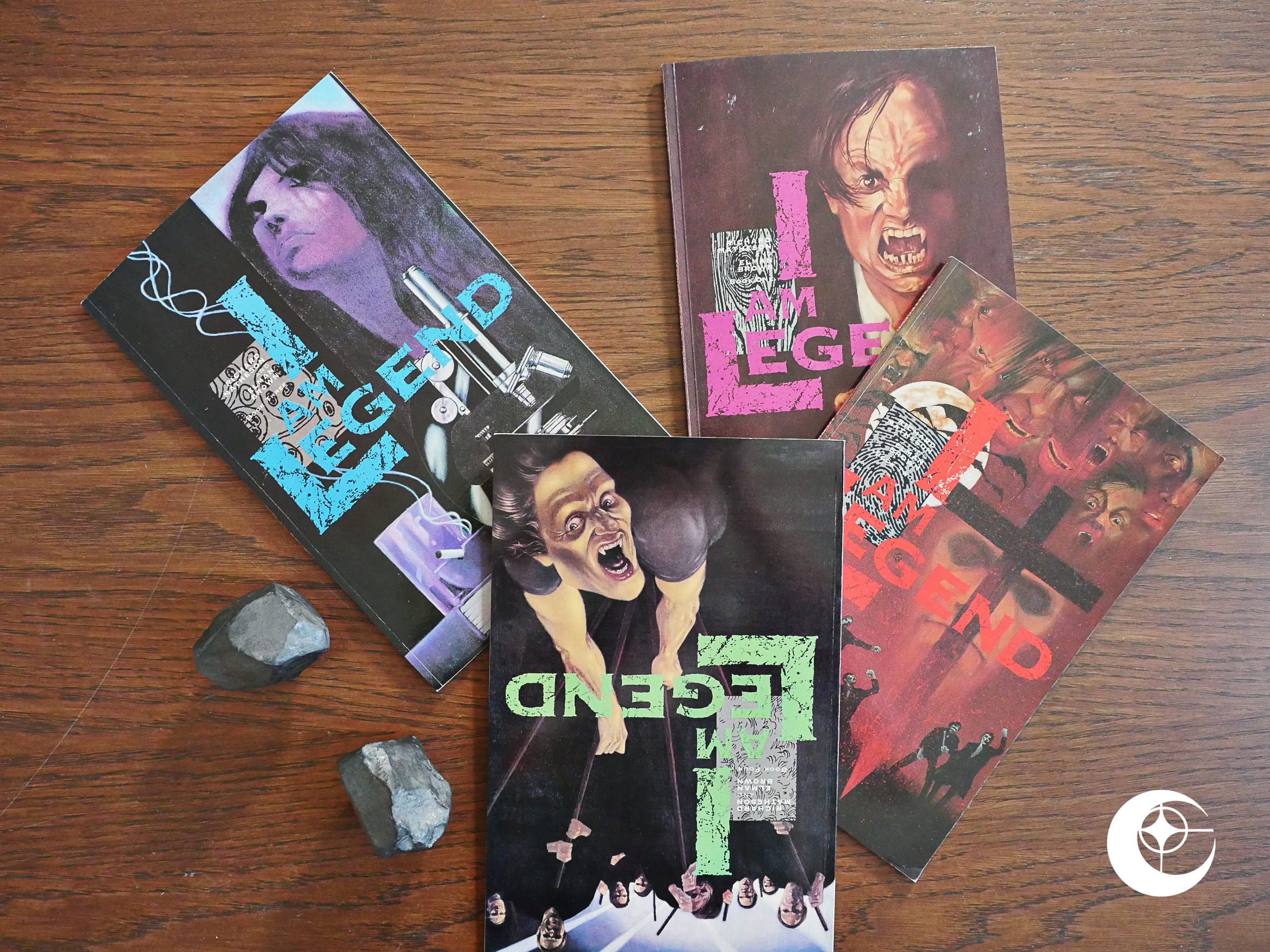

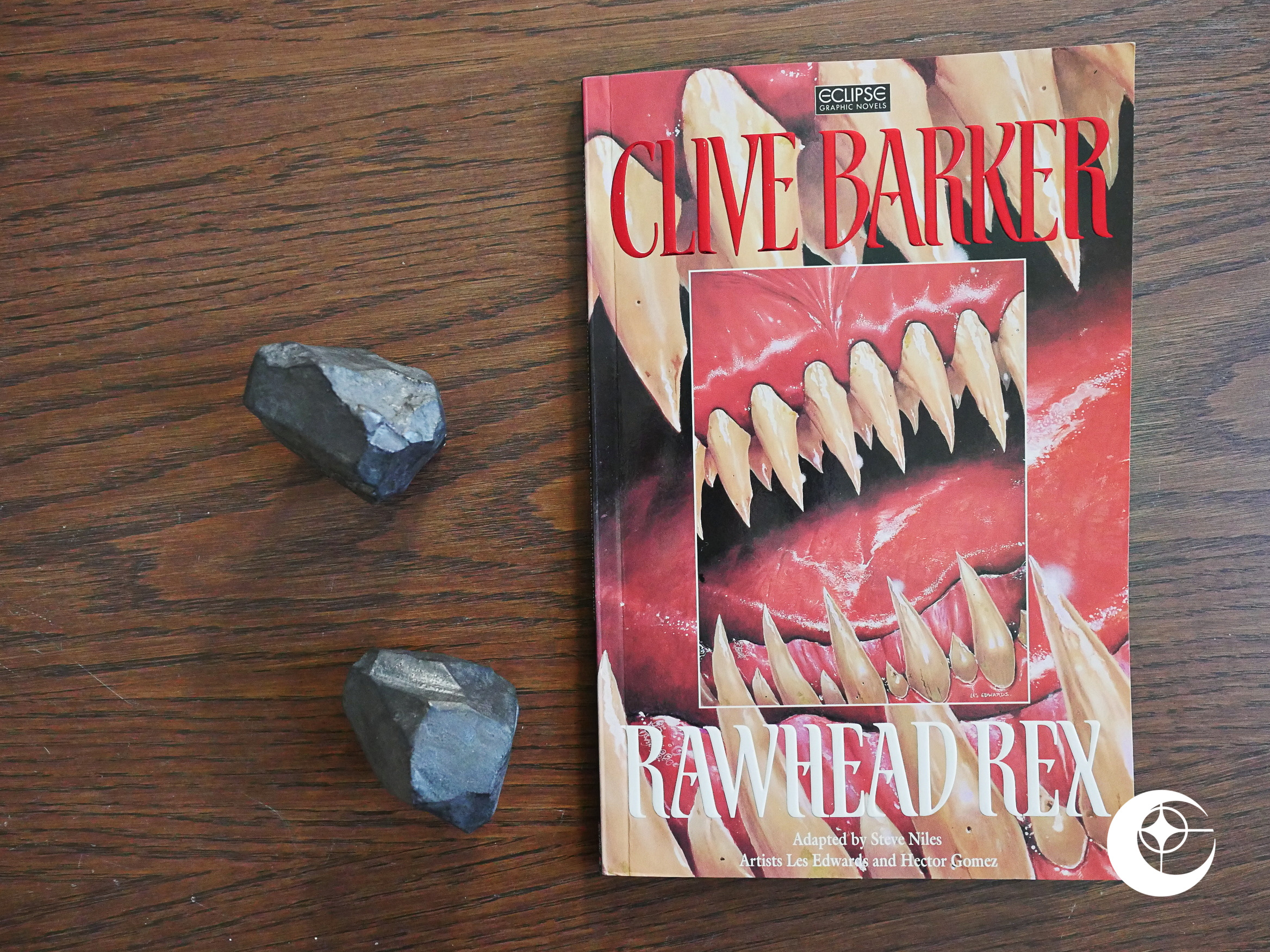

Rawhead Rex (1994) adapted by Steve Niles, Les Edwards and Hector Gomez.

I covered the other five stand-alone Barker adaptations in another post, but I saved this for a separate blog post because it not only has an interesting origin story, but it’s the final thing Eclipse ever published, I think.

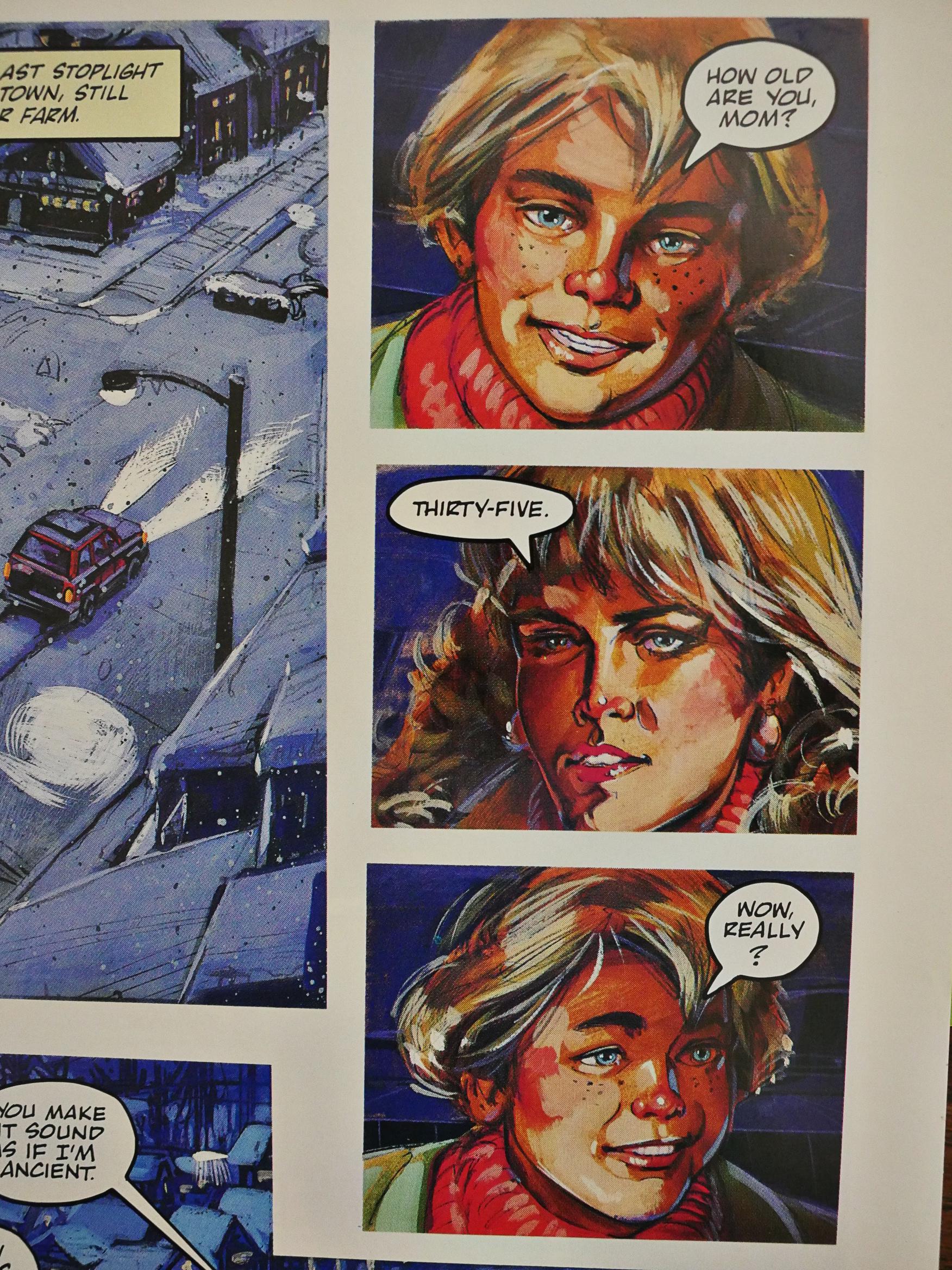

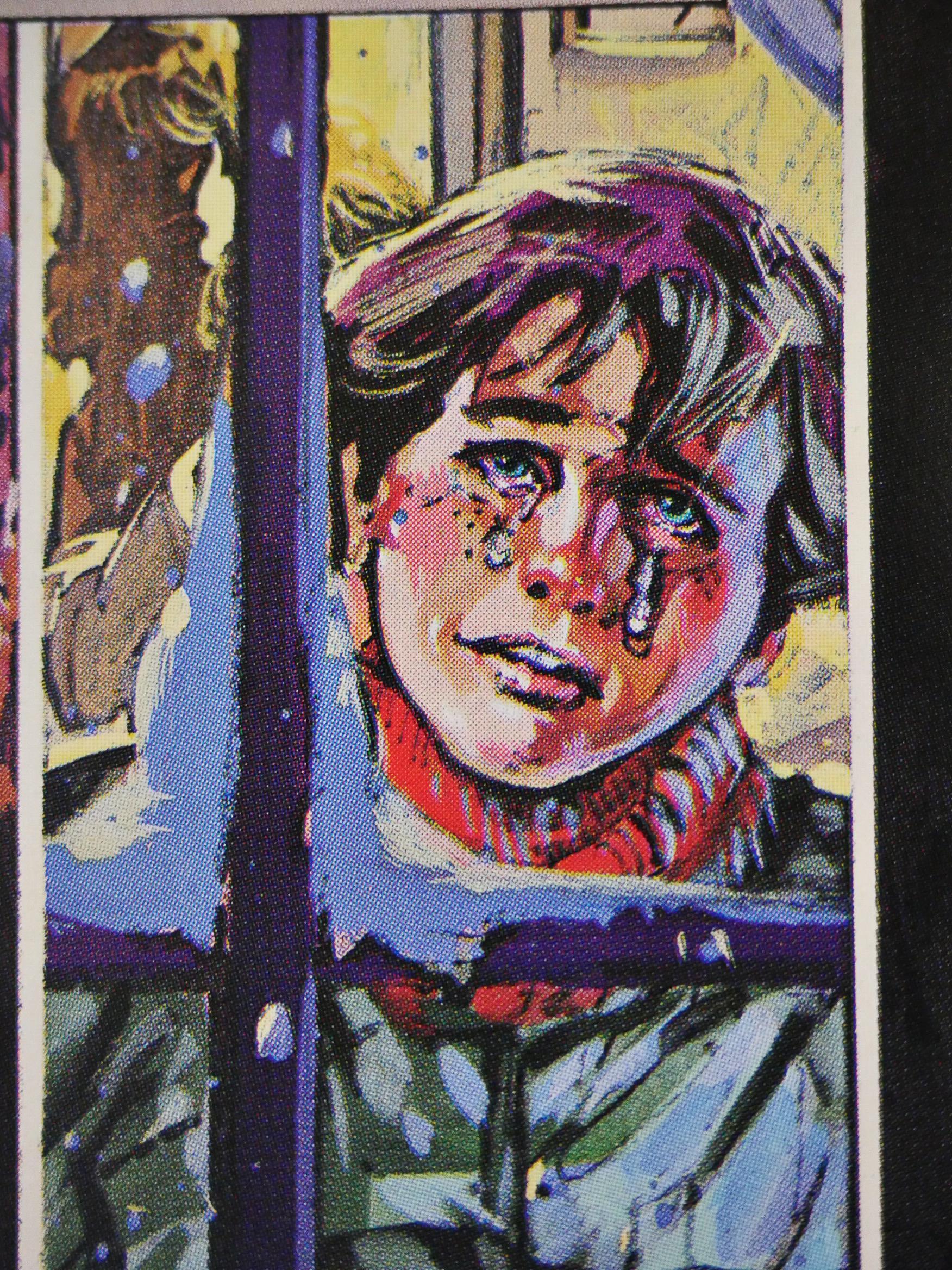

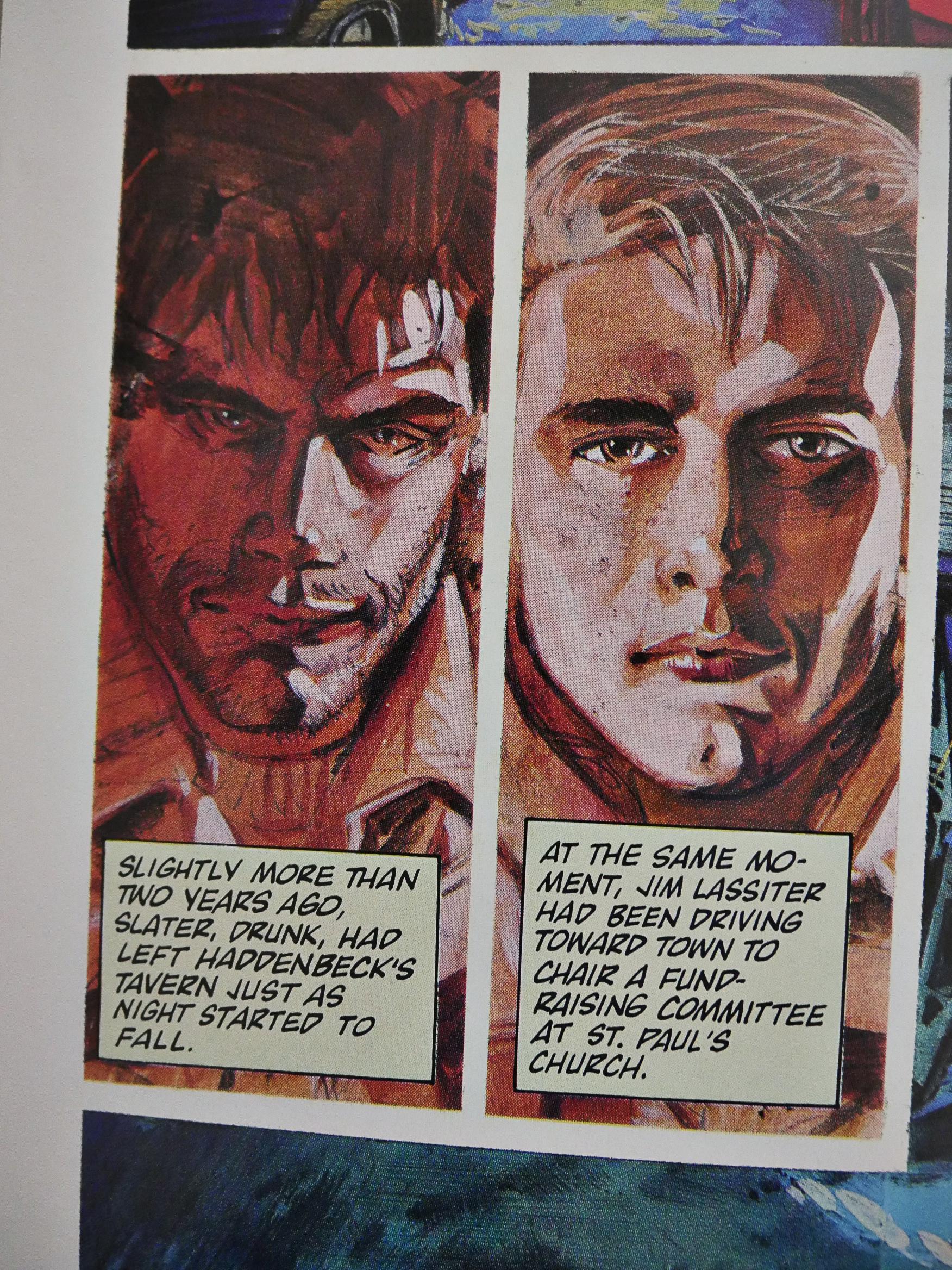

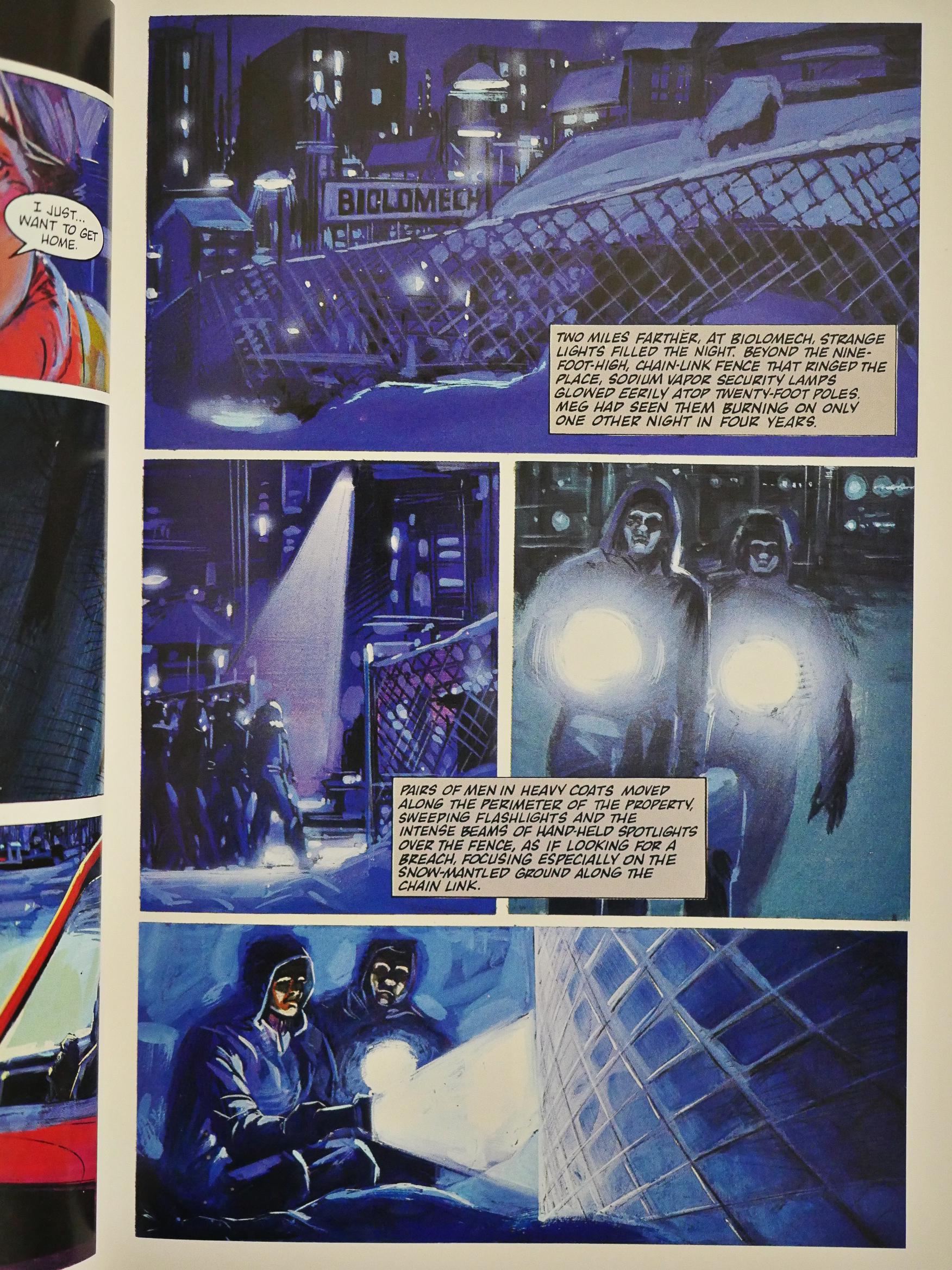

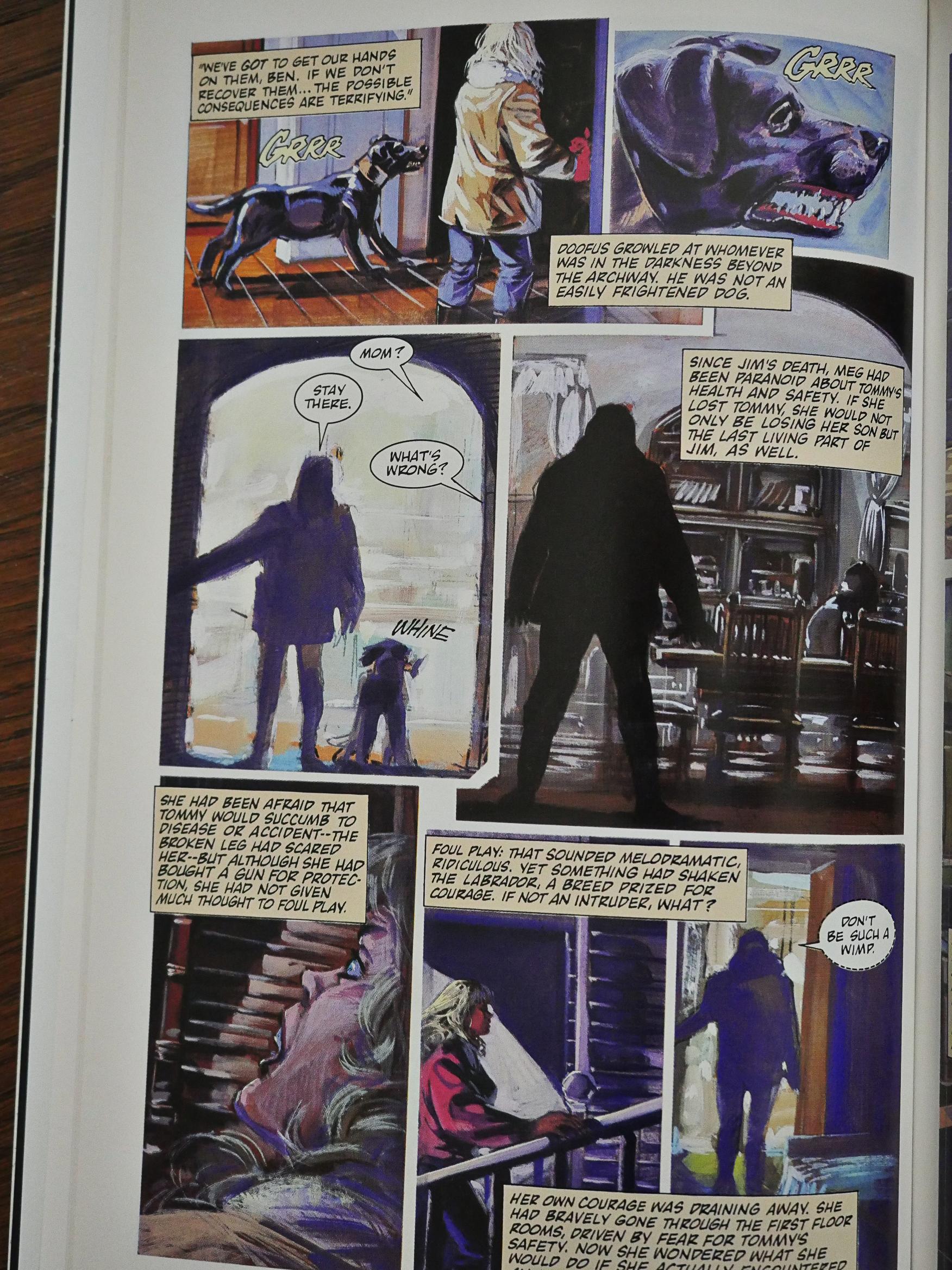

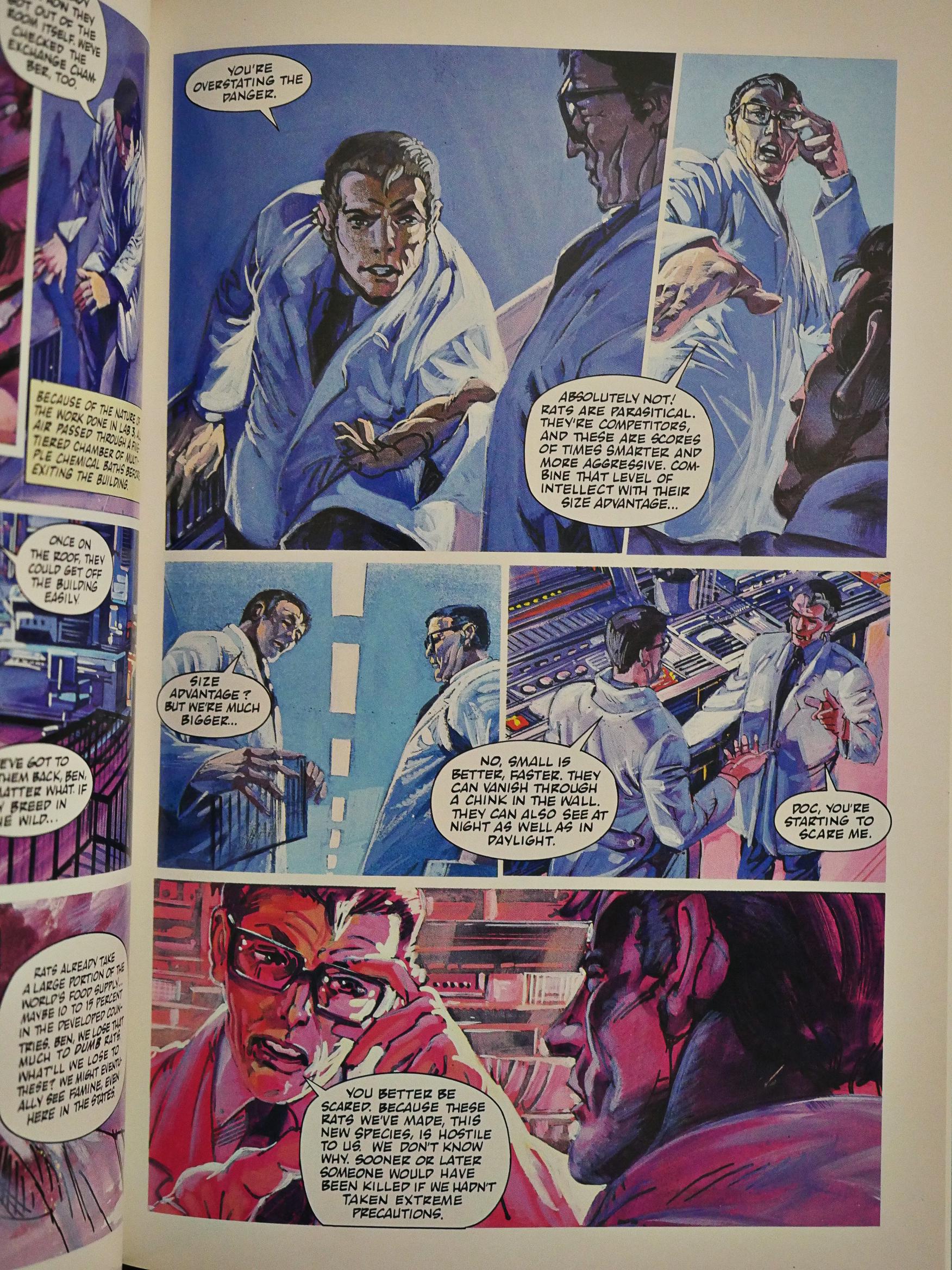

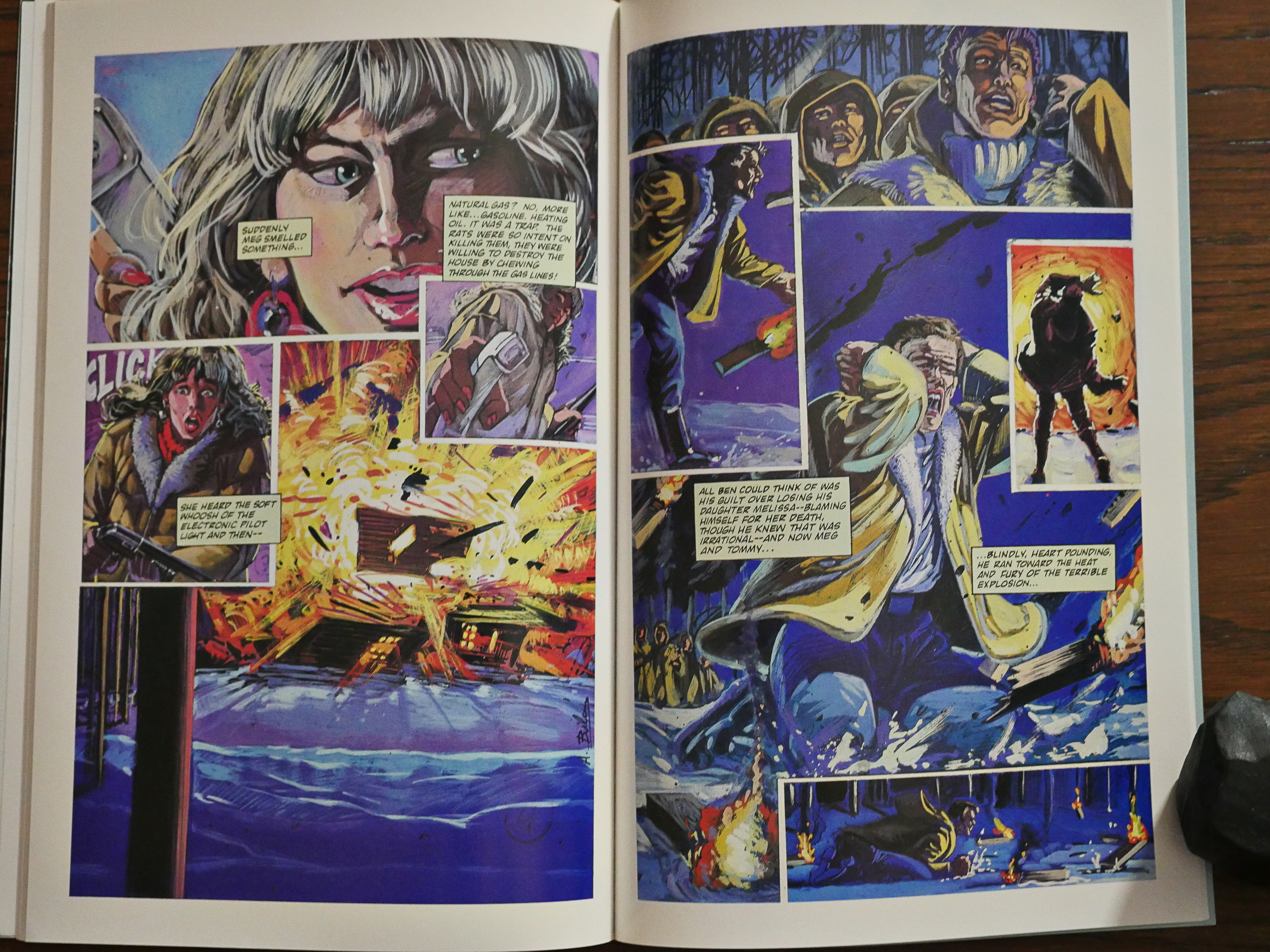

But before we get into that, let’s have a look at the book. Yup, that’s the standard Eclipse approach to adapting a short story: Cram in as much of the original text as possible in captions that float around nicely painted artwork. This time it’s by Steve Niles and Les Edwards.

It’s a remarkably grisly adaptation (but I’m not going to show any of the more full-on pages, because this is, after all, a family oriented blog). It’s not like the other Barker adaptations had shied away from showing violence or anything, but the sheer detail of Edwards’ carcasses and entrails is rather over the top.

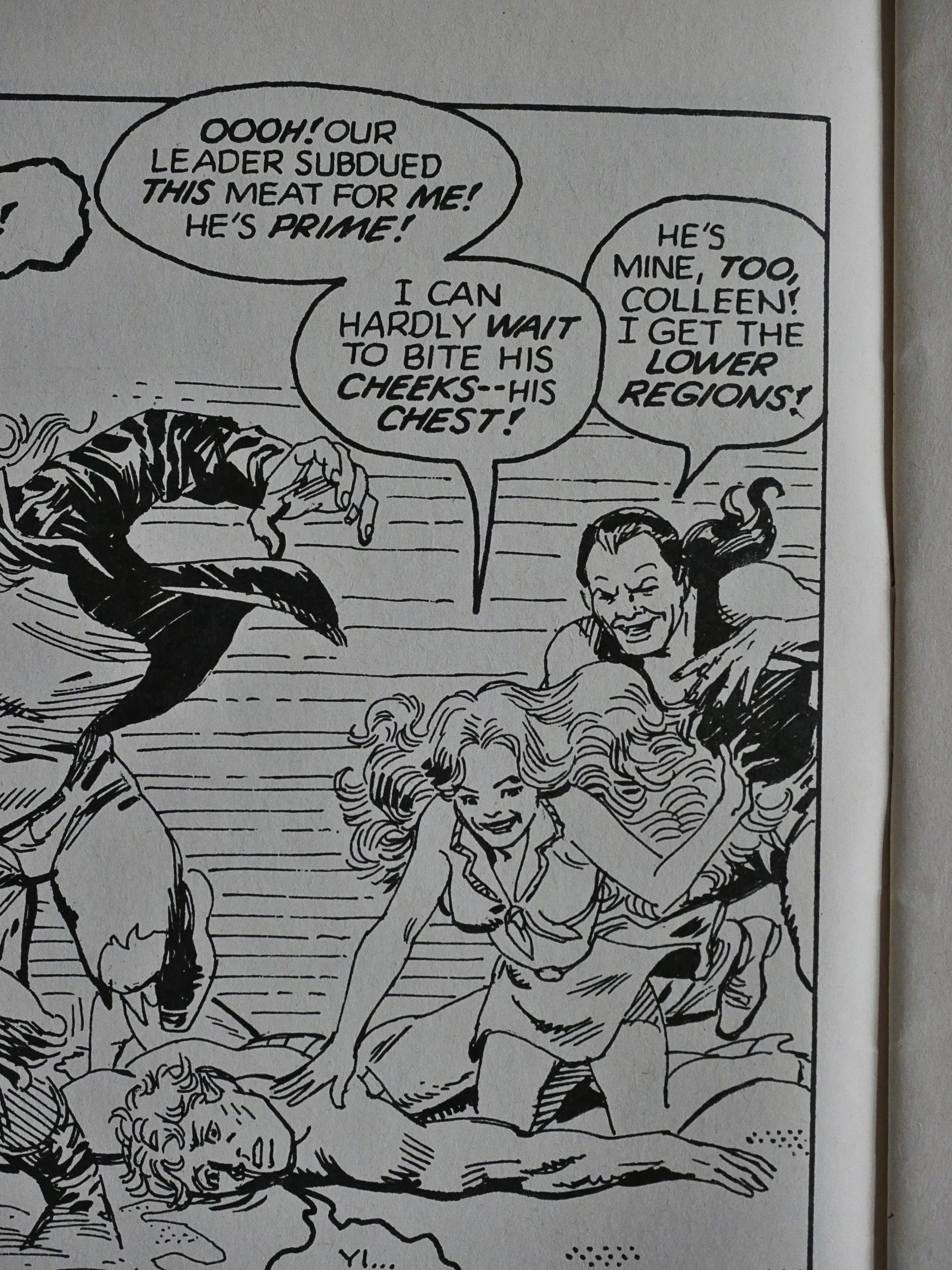

The story, which I think I’ve read before as a short story back in the 80s, is all about male and female power. VERY SYMBOL. But it’s fun to see menstruation being a super power.

Edwards’ artwork looks very photo reference based. Except for the monster, which I hope isn’t? But, as usual, it means that the artwork is limited by how good actors they managed to scare up to be photo models. And, as usual, they aren’t very.

But you have to say that the stiffness of the characters suits the stiff and portentous prose, right?

Heh heh. That’s an impressively deranged looking priest.

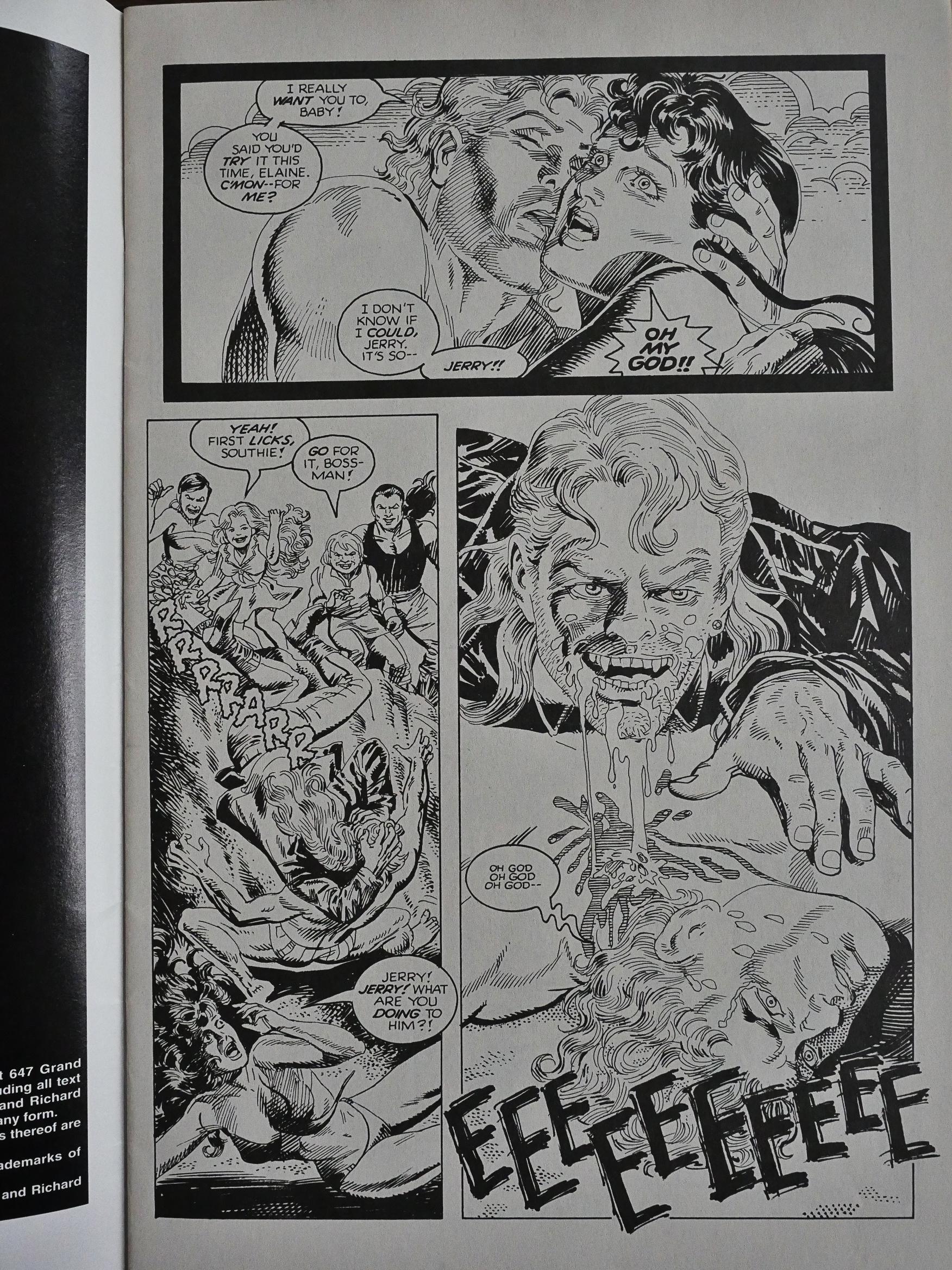

Oh, yeah, now I see what the monster reminded me of: The xenomorph from Alien. But, of course, that monster was also modelled after a penis, so that’s not that surprising.

I didn’t think that this was a particularly exciting reading experience. Like I keep saying about these adaptations (I should find a new phrase (oh, wait, this is the last post I”M FREE!1!!)), it’s more like reading an illustrated prose story than reading a comic book. You could rearrange these drawings and blocks of texts and just have a traditional picture book, and you’d get the same effect.

The second story in this book, with artwork by Hector Gomez (which is about werewolves OOPS SPOILERS), is so drenched with prose that it looks like a parody of what you imagine an adaptation to be.

And I think they were scraping the bottom of the Books of Blood barrel here. It doesn’t seem like a particularly compelling story.

But here’s the stunning origin story of the Eclipse adaptation of Rawhead Rex. I’m quoting at length from Steve Bissette’s interview in The Comics Journal 185:

Around that same time was Rawhead Rex: similar lesson. Michael Zulli and I struck a deal with Steve Niles at Arcane Publishing; I was going to do the story adaptation, and we going to collaborate on the artwork.

Steve was a young guy, like 20, 21 — very young guy. Heaven knows how, but Steve ended up with the rights to Clive Barker’s material in comic book form some of it, in any case, Clive was also doing stuff with Marvel, which Steve Niles was not concerned with.

So we struck a deal to do Rawhead Rex, same thing happens, marketing machine goes into place. The only art that I was ever paid for by Arcane Press was a poster I did. I wasn’t paid in money, I was paid in Clive Barker portfolios. (laughs) Which I still have. Beautiful portfolios.

Arcane immediately started having business problems. Steve, being young and inexperienced, hired some business management people, who did what business management people do: They made sure they got paid. (laughs) It’s absurd to hire business managers for a business whereyou’ve only published one book. (He had a book Out called Bad Moon,)

The promo of Rawhead Rex was more important to Arcane Publishing than the doing of Rawhead Rex. When it came to the point where Arcane could not pay for the work, I came back to them with what I thought was a creative solution; Michael Zulli thought so too, and Clive Barker was willing to work with it: We’d serialize it in Taboo.

Now think about this for just a moment, Kim, this is how foolhardy Bissette was. I am now going to now work my ass off to pay myself to draw Rawhead Rex. At that time, it seemed worth it in the long run. Alan had been sending John Totleben and me Clive’s books in the Sphere paperback editions as they first came out in England. We met Clive in England, again through Alan, long before people in the U.S. were aware Of who Clive was. I had by that time read all six Books of Blood, thanks to Alan. I knew that Clive was a revelation, an important author in the genre.

At one point, we all met at the DC offices; Clive , actually did persuade Dick Giordano to let John and I adapt and illustrate any one of his stories we chose! So to me, to invest my own money into doing this serialization in Taboo made a certain amount Of sense. If we then retained all the rights to the Rawhead Rex property in comic form we had something to go to the book market with. Ah, that promised land again. So it sounds wacky in hindsight, but at the time I was able to rationalize it.

Zulli cleared his work schedule So that he could start work within a specific window, and I was overjoyed that I would finally draw a serial running in my own book; up to then I’d only done one or two short pieces in Taboo. I was working my ass off to make enough money to pay Alan and Eddie and all these other folks in Taboo.

I had broken “Rawhead Rex” down to comic layouts in a paperback copy of Books of Blood; it was going to be 92 pages long. I called up Clive and we worked Out a couple of narrative sequences I felt were necessary for the story to work as a visual narrative.

Things got sticky when Niles called and said, “Well, Arcane’s going out Of publishing. I’m going to work with Eclipse.” And I went, “No fuckin’ way” (laughs). This was after the Scout thing and all this other shit. Steve groaned and he says, “Not you, too — everybody says that.” He was losing long-term commitments he’ d had w ith people like Ted McKeever because he had to gravitate to where the money was to continue packaging and publishing projects, which was Eclipse. Eclipse wanted Steve Niles not because Steve was a visionary of any kind; he had the Barker stuff. They wanted to corner that market. They wanted to be, along with Marvel, the only publisher of the Barker material. It was one of the more lucrative properties Eclipse had in its final years.

THOMPSON: It kept them alive for a few more years, probably.

BISSETTE: Yeah, I’m sure. At that point, I told Steve, “Look, I just don’t see the sense in this.” What I didn’t know was Arcane’s option on “Rawhead” had expired, and Eclipse had purchased it.

One phone call from Dean Mullaney killed it for me.

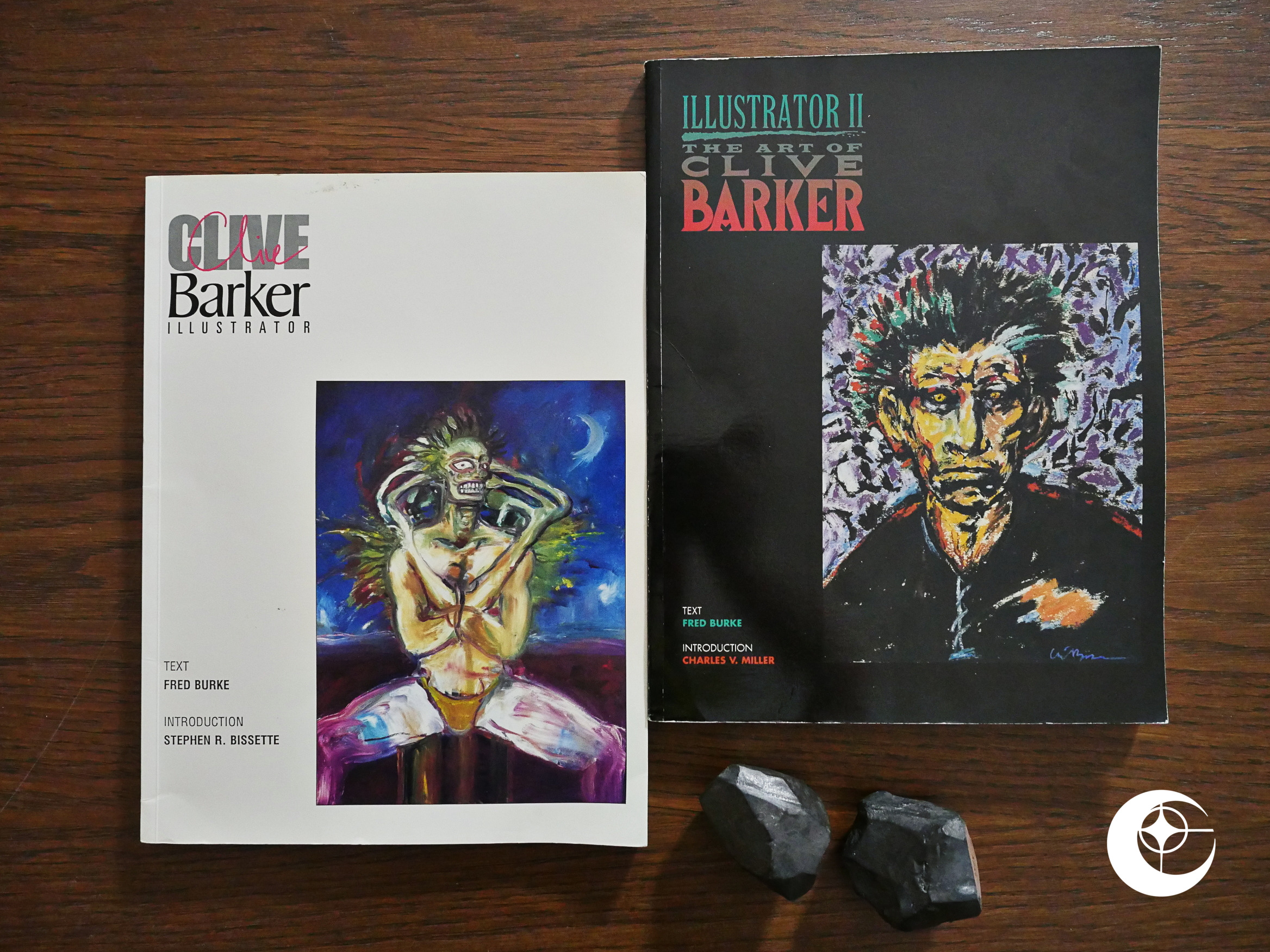

I had already been through a little dance with Dean. Dean had approached me when Eclipse was putting together the Clive Barker anthology Tapping the Vein; he wanted me to take on doing one of the adaptations. I countered with, “My problems with Eclipse beside the point, Dean, you would not want to publish what I would draw from Clive’s stories.” And he said, “What do you mean?” He had only read one Barker story, the first story in the Books of Blood. They had already chosen the story for me, “Jacqueline Ess, Her Will and Testament,” in which the title character, a prostitute, can manipulate the molecules ofher ow n flesh to satisfy her customers; it ends with a vicious confrontation between the man she’s fallen in love with and her pimp, and she folds her body around her lover to become this single, organic being. Clive being Clive, it’s very explicit. I don’t have a problem with that. For me, especially with some of the stories Clive was doing at that time, it had to be explicit for you to understand it, like a David Cronenberg film. If you don’t see that shit in The Brood or Videodrome, it makes no sense to you — the concepts are so alien to how most people think Ilaughsl that it has to be made explicit. I read a passage to Dean, as her vagina folds around itself, and he was just mortified. “Well, couldn’t you put it in the shadows and have a caption?” “Dean, there’s my point, you’re not going to want to publish what I draw from this.”

So I had already had my little dance with them and bowed out. With Rawhead Rex, I got one call from Dean: “Well, we’re a team now!” Zulli’s and my attitude was, using the Dean’s metaphor, we weren’t baseball players, we were not about to be traded from one publisher to another. Dean’s arguing that I could still publish it in Taboo. “Dean, I am not going to bust my hump topayme, Michael Zulli and Clive Barker so you get a book at the end of it.”

That was the end of Rawhead Rex, and it got very vindictive, because we felt it important to publish our designs. Clive’s ownership of “Rawhead Rex” the Story is unquestioned, but we own those drawings that we did. That design is Zulli’s and my design, so we went through some pains to get them published —you ran them in the sketchbook in the Journal with my interview, we sent a press release with some of the drawings to the CBG. It was very important to us that that stuff, it be seen so that whatever Eclipse did, they would have to do it differently than had, and they ultimately did.

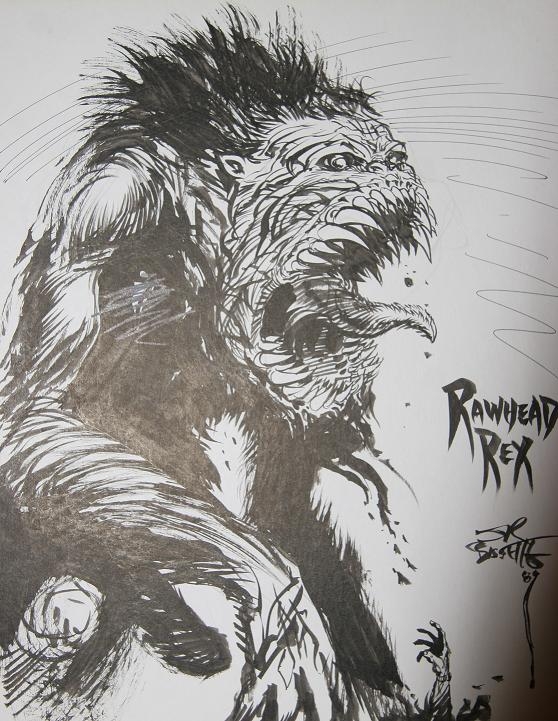

And here’s Bissette’s design for the monster:

That’s very different and not very penisy at all. I mean, except for the penis.

Anyway, sorry I had to quote at length, but it was difficult to cut anything. But it does confirm my hypothesis about how the Barker short stories ended up at Eclipse: Via Steve Niles, who ended up working for Eclipse.

But this is the final thing Eclipse published. Here’s what publisher Dean Mullaney said was the reason they closed up shop was:

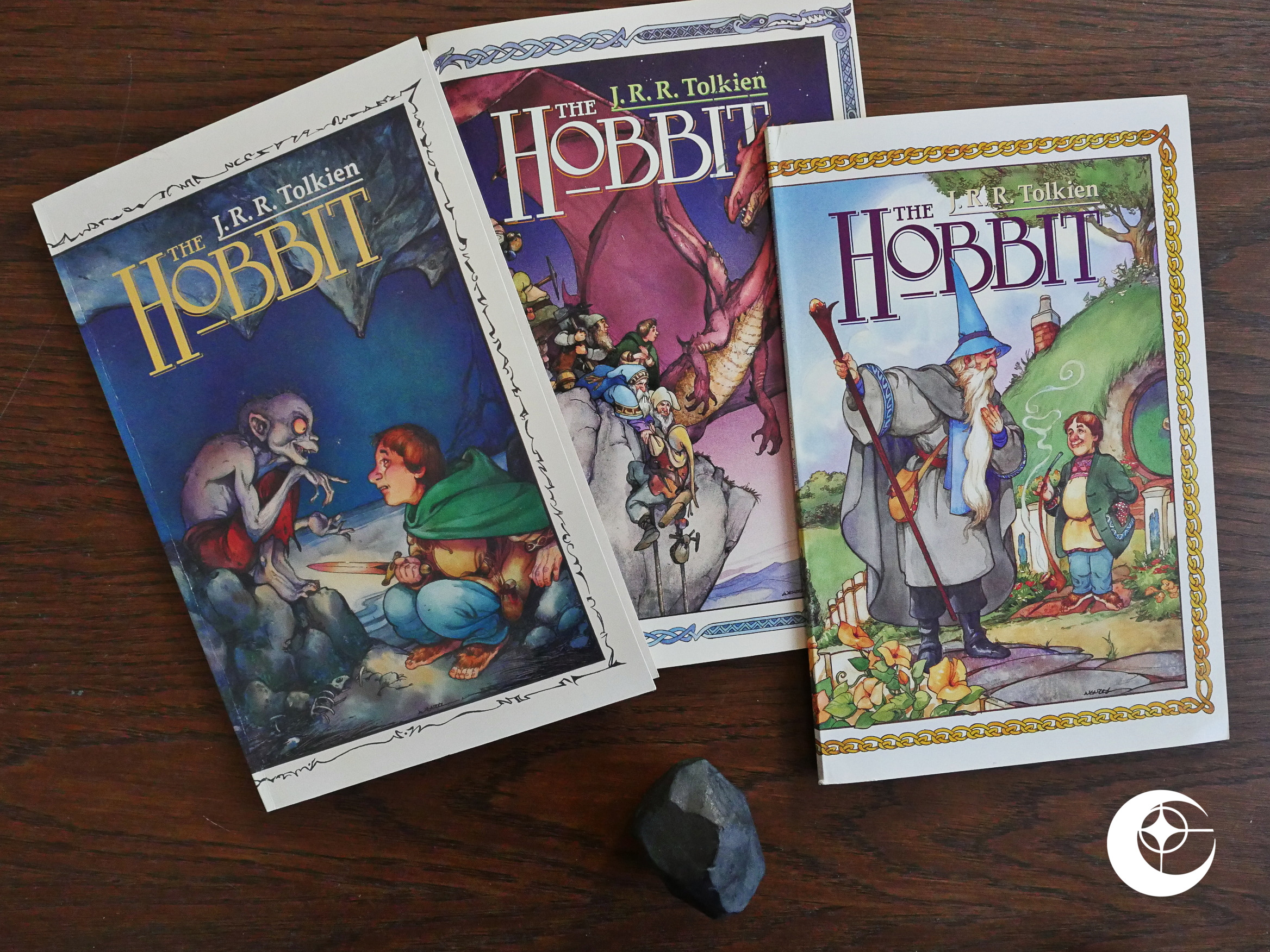

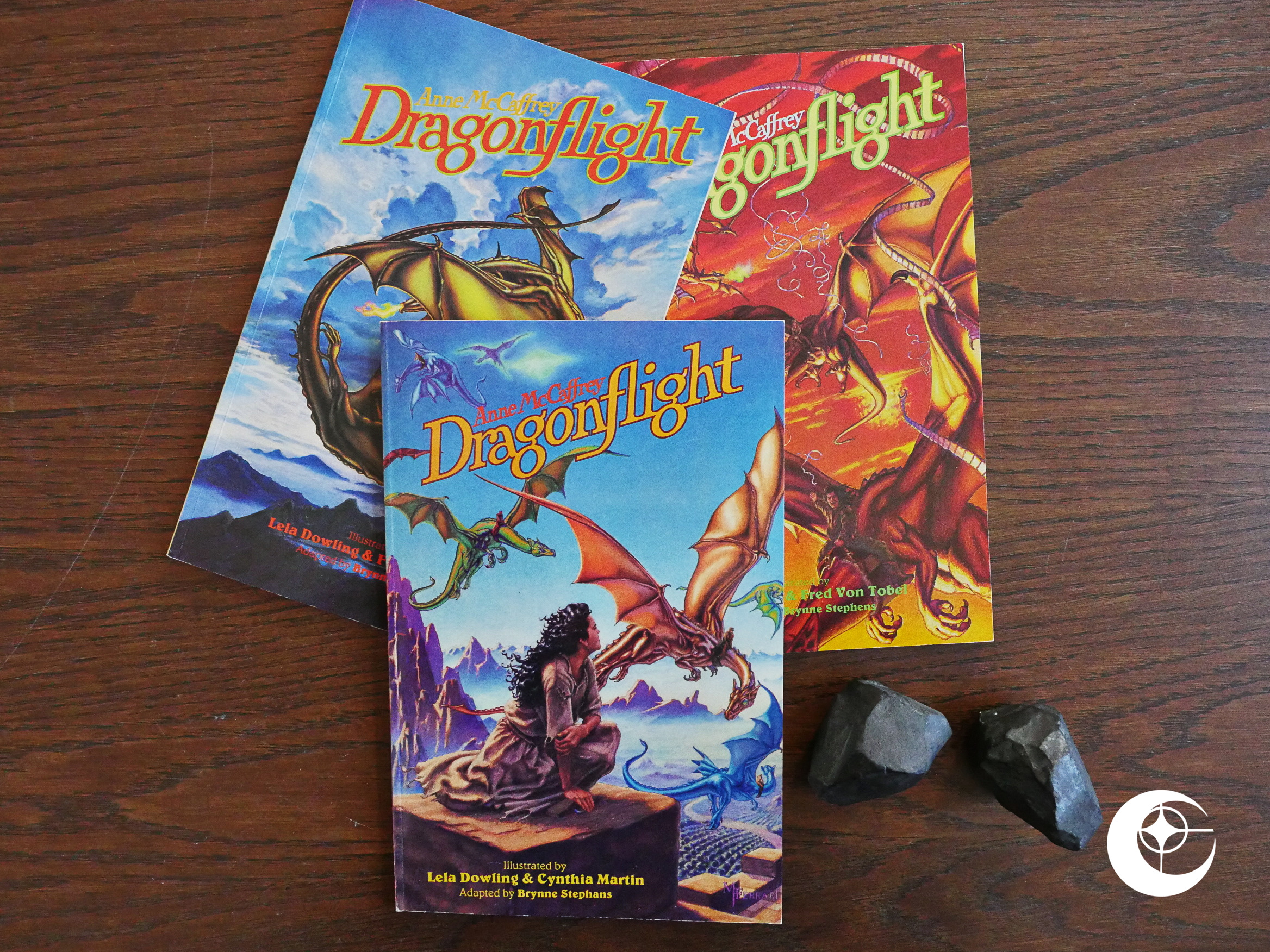

Eclipse had signed a mutually-exclusive contract with HarperCollins to produce graphic novels. The plan was to first introduce titles by authors already known to booksellers — J.R.R. Tolkien, Clive Barker, Dean Koontz, Anne McCaffrey… we even had an original by Doris Lessing in the planning stages.

Unfortunately, HarperCollins didn’t, in my opinion, really understand what graphic novels were all about. And there were internal conflicts at HC, to which I was never privy, that left Eclipse holding the bag. They had given us an advance to start production, but that money ran out, and we had a full schedule in production. We never received a single royalty statement, let alone check, from HC’s sales to bookstores. The cash flow deficit eventually forced us to close up shop.

Now, Toren Smith sued Eclipse in December 1993. He won the suit and was awarded $122,238.59 in September 30th, 1994. (Those last 59c probably hurt the most.) Eclipse filed for chapter 7 bankruptcy on December 21st, 1994.

catherine ⊕ yronwode said this in 2013:

Now, Dean has directly stated that he was owed money by Harper-Collins (“I still have no idea how many copies of our graphic novels Harper sold, or what they did with the money owed us and creators”), and that might explain his company’s failure to continue payments to Toren Smith — except for one thing: Dean and Jan could (and should) have sued Harper-Collins for breach of contract, and apparently they did not. So my next question would be to ask Dean why he and Jan did not sue Harper-Collins for failing to produce sales records and royalty statements.

Yeah, Mullaney’s explanation as to why Eclipse folded raises more questions than it answers, doesn’t it?

This is the last comic Eclipse published… but I’m sure you’ll be relieved to learn that it’s not the last post on this blog. I’ll be posting an overview of Eclipse’s history (through the comics), and then a number of indices that focus on certain parts of Eclipse’s output (i.e., a post to list all the graphic novels, another for the 3-D comics, another for the Japanese translations, and so on). We’ll return to some of these questions in those posts.

Is there any way to read old US court transcripts, by any chance?

[edit some time later: There is! Read the documents here.]

51: Son of Celluloid (1991)

51: Son of Celluloid (1991)

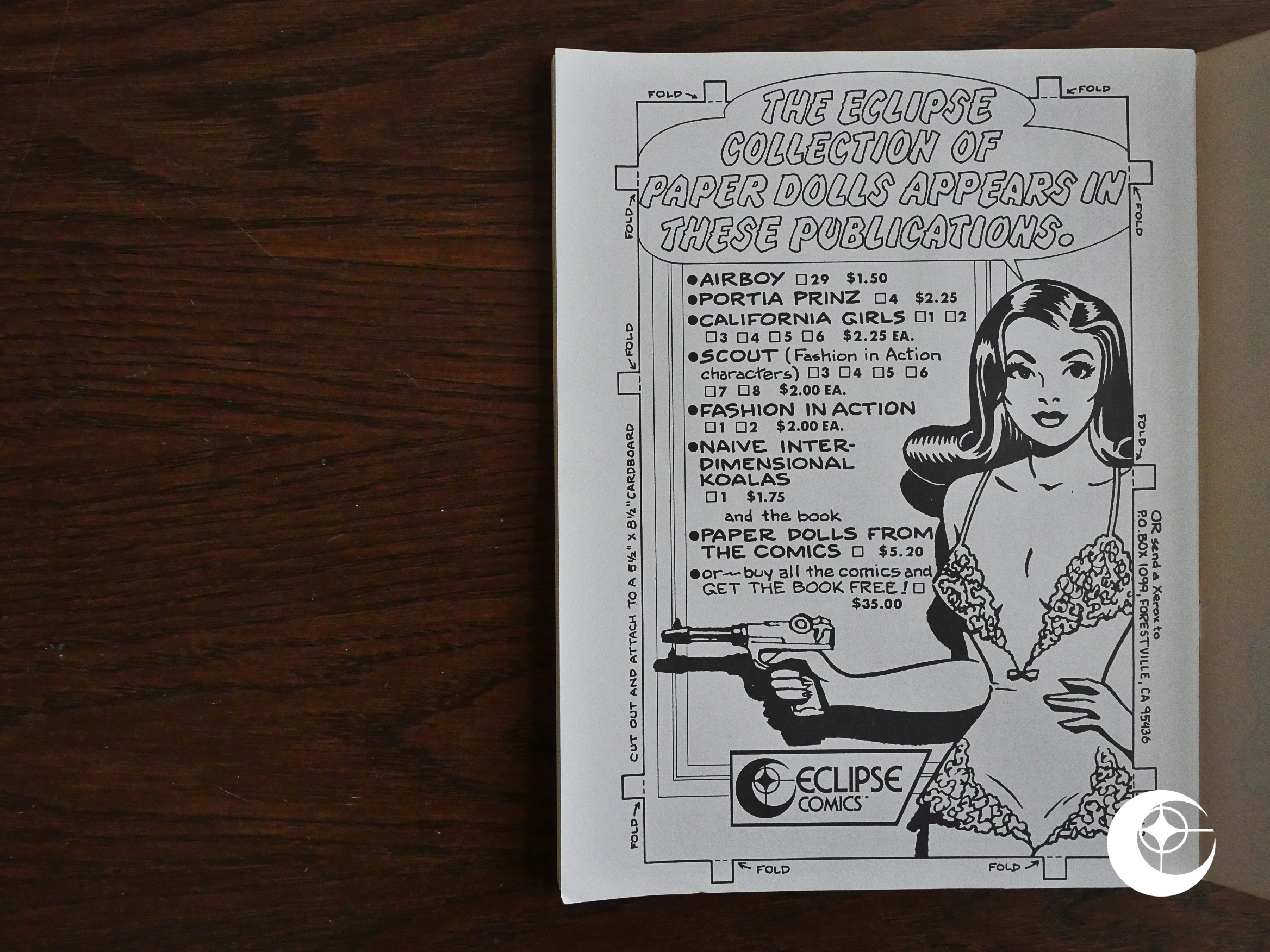

Airboy (1986) #29

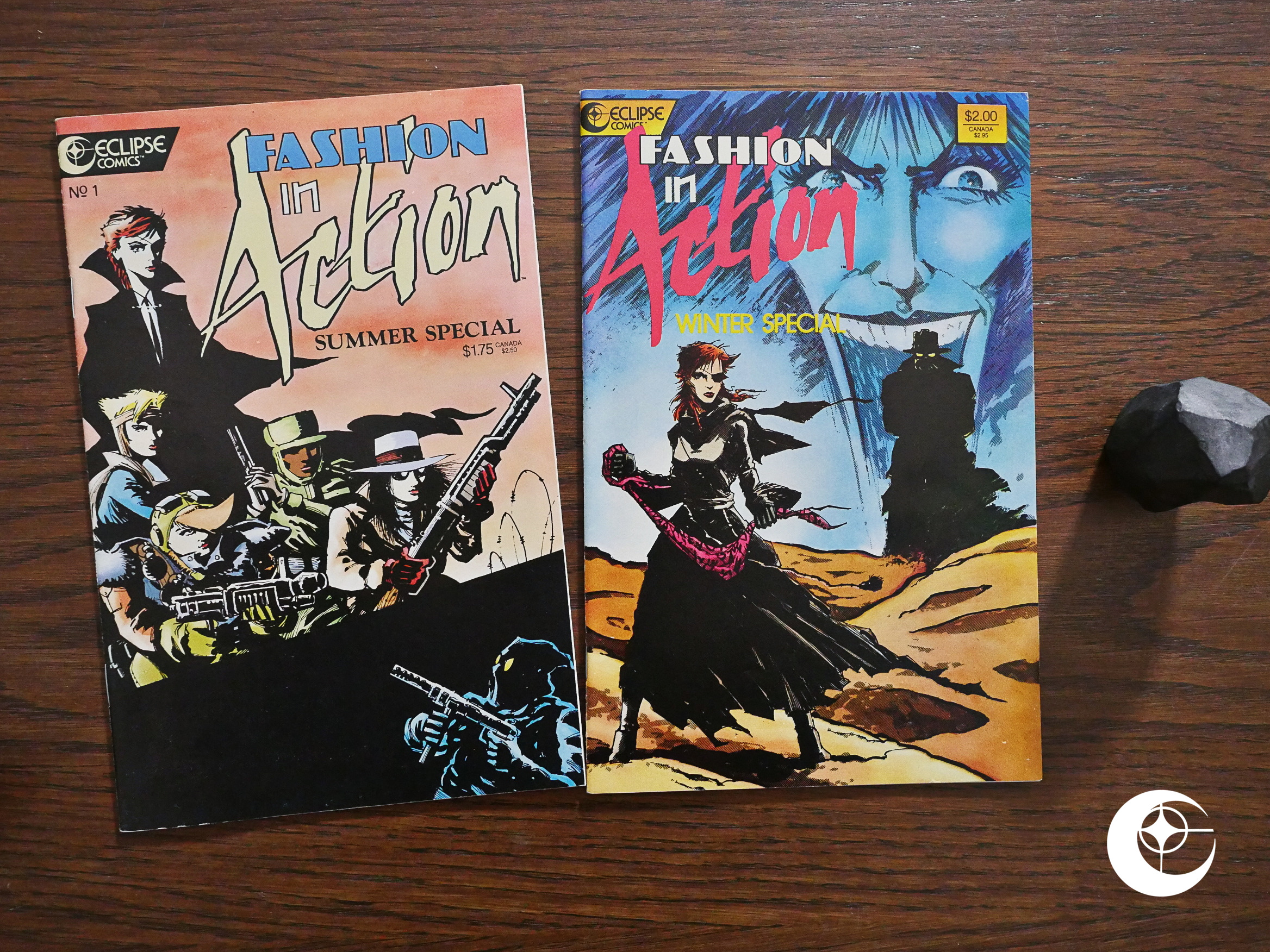

Airboy (1986) #29 Fashion in Action Summer Special (1986) #1

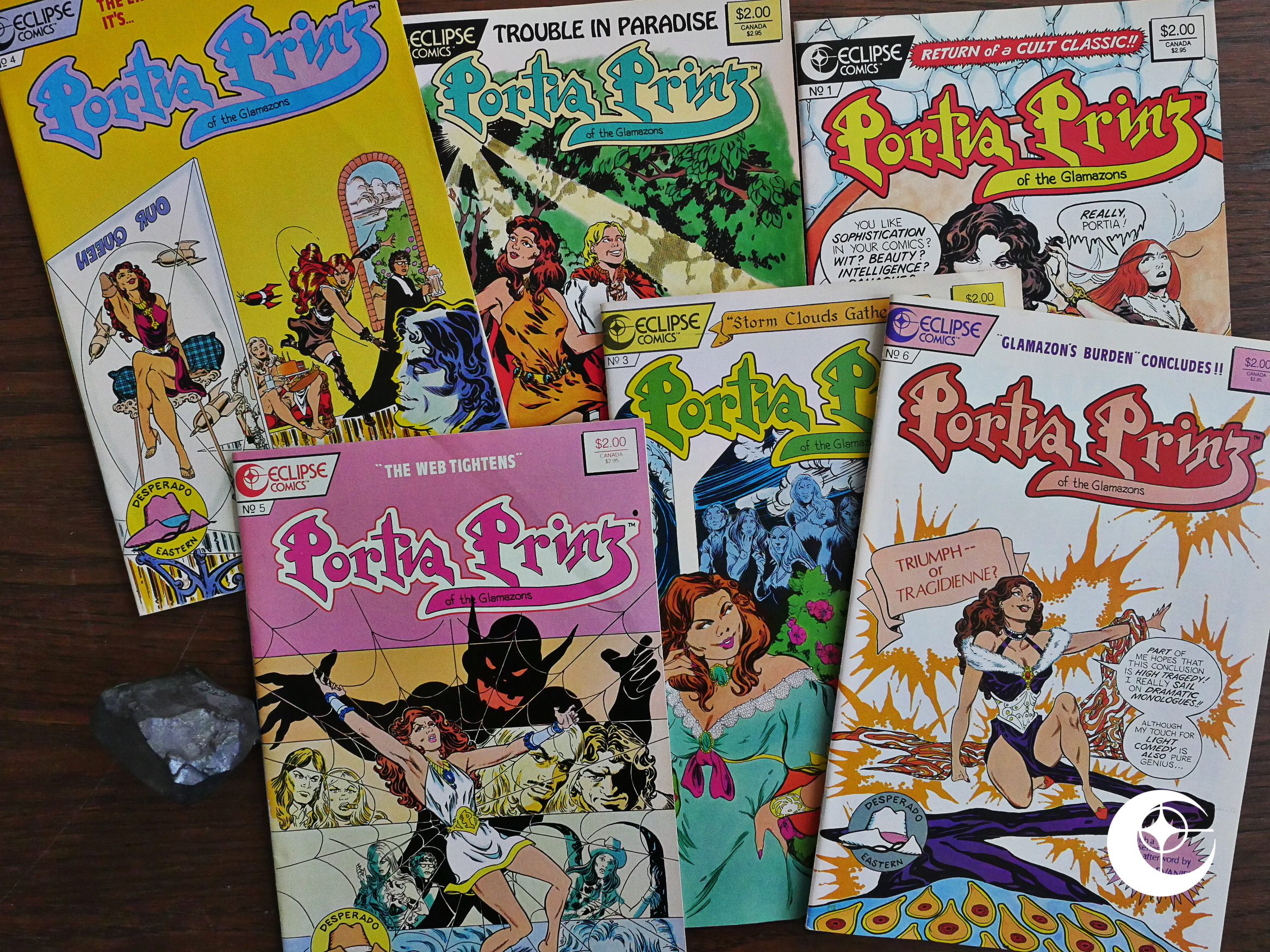

Fashion in Action Summer Special (1986) #1 Portia Prinz of the Glamazons (1986) #4

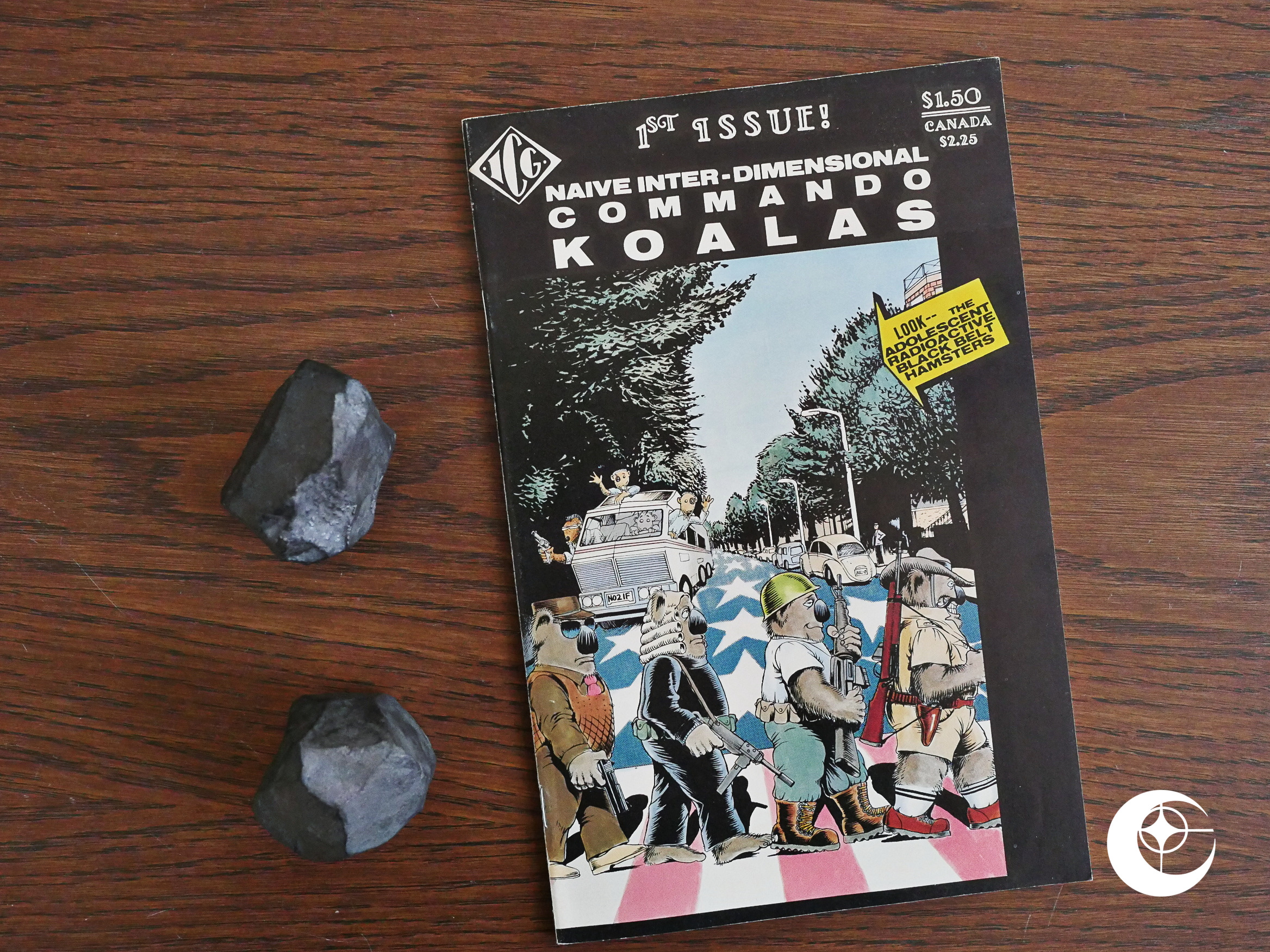

Portia Prinz of the Glamazons (1986) #4 Naive Inter-Dimensional Commando Koalas (1986) #1

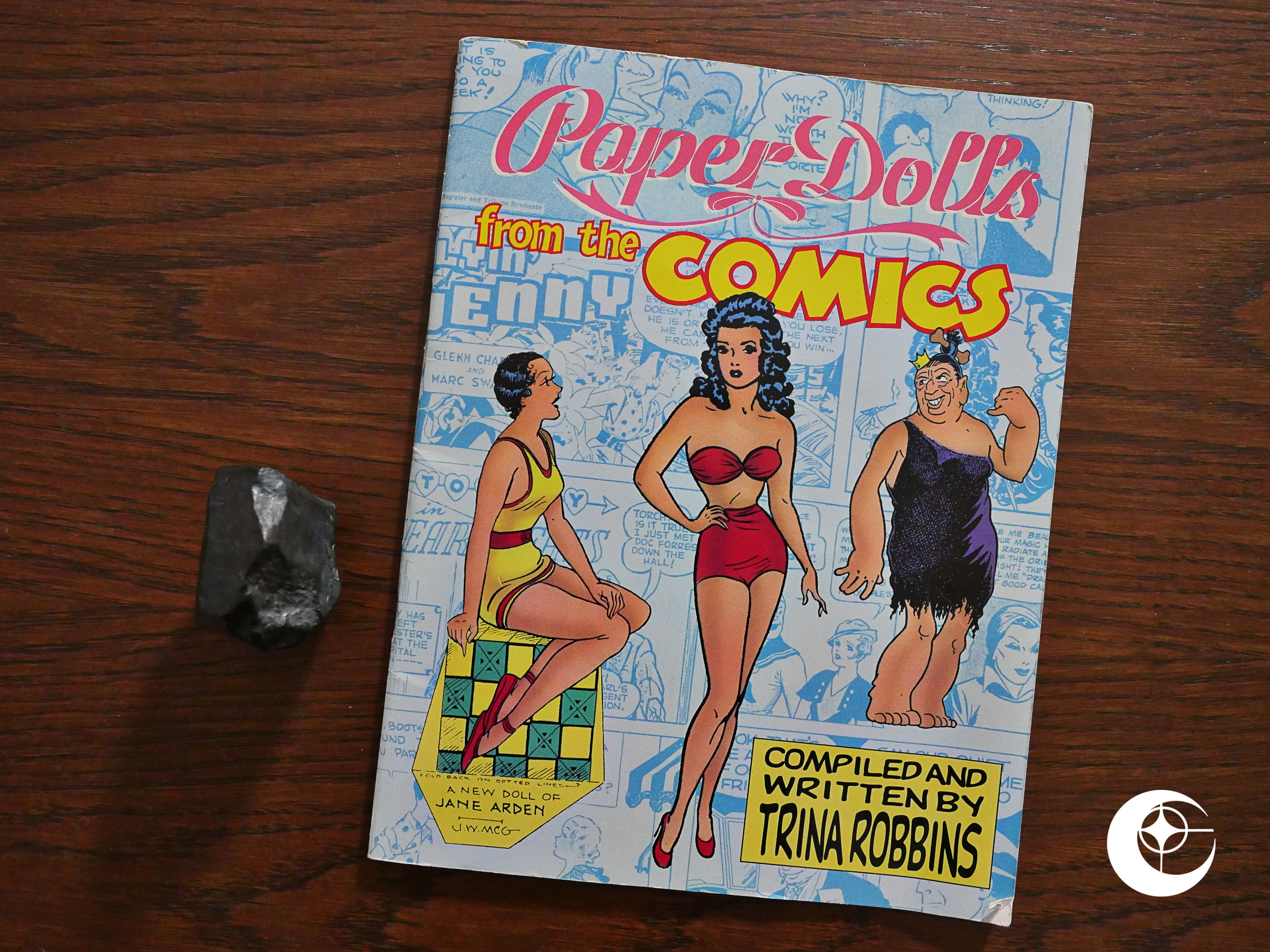

Naive Inter-Dimensional Commando Koalas (1986) #1 Paper Dolls from the Comics (1987) #1

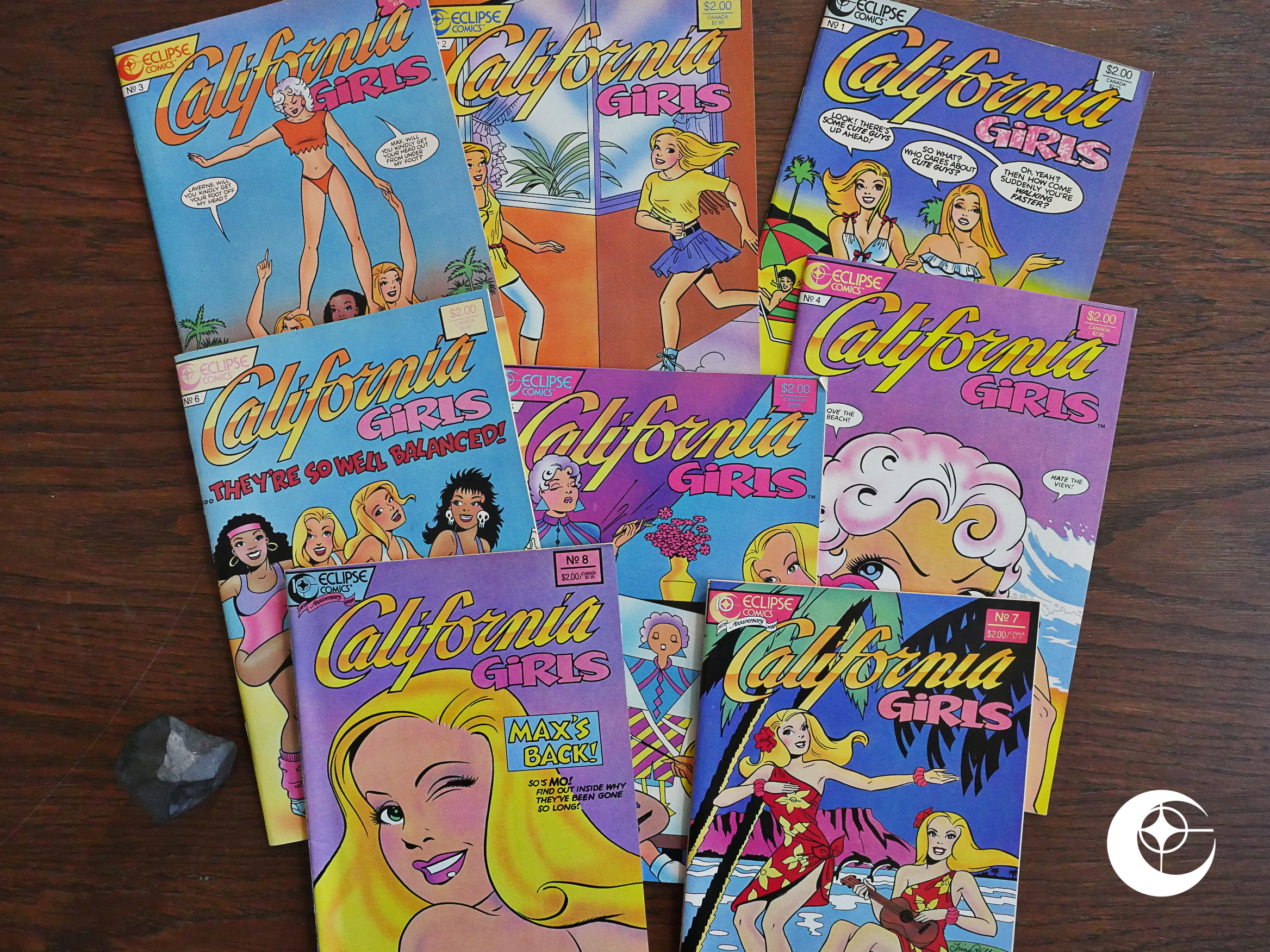

Paper Dolls from the Comics (1987) #1 California Girls (1987) #1-8

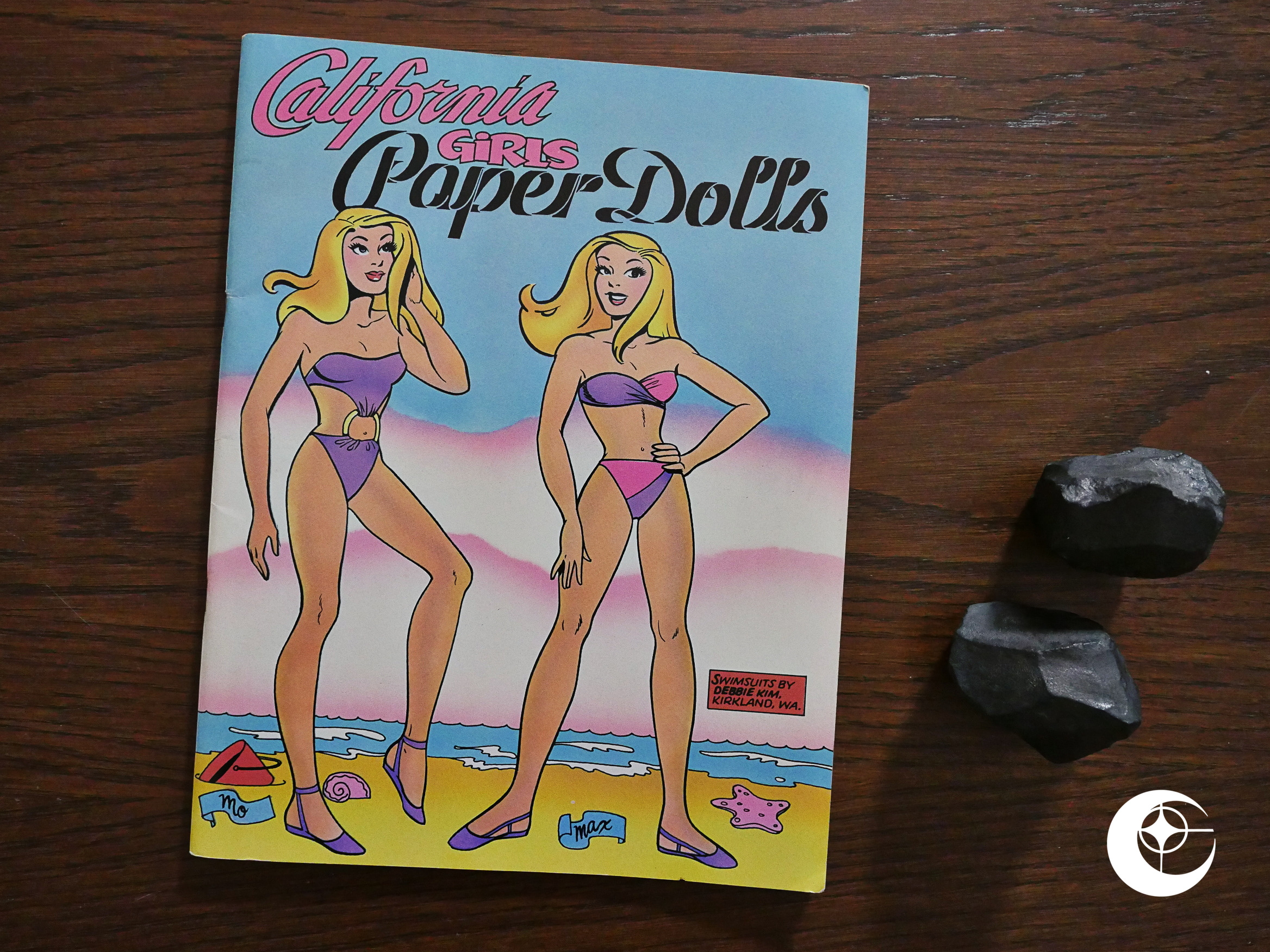

California Girls (1987) #1-8 California Girls Paper Dolls (1988) #1

California Girls Paper Dolls (1988) #1

written by somebody with no association whatsoever with that publisher.

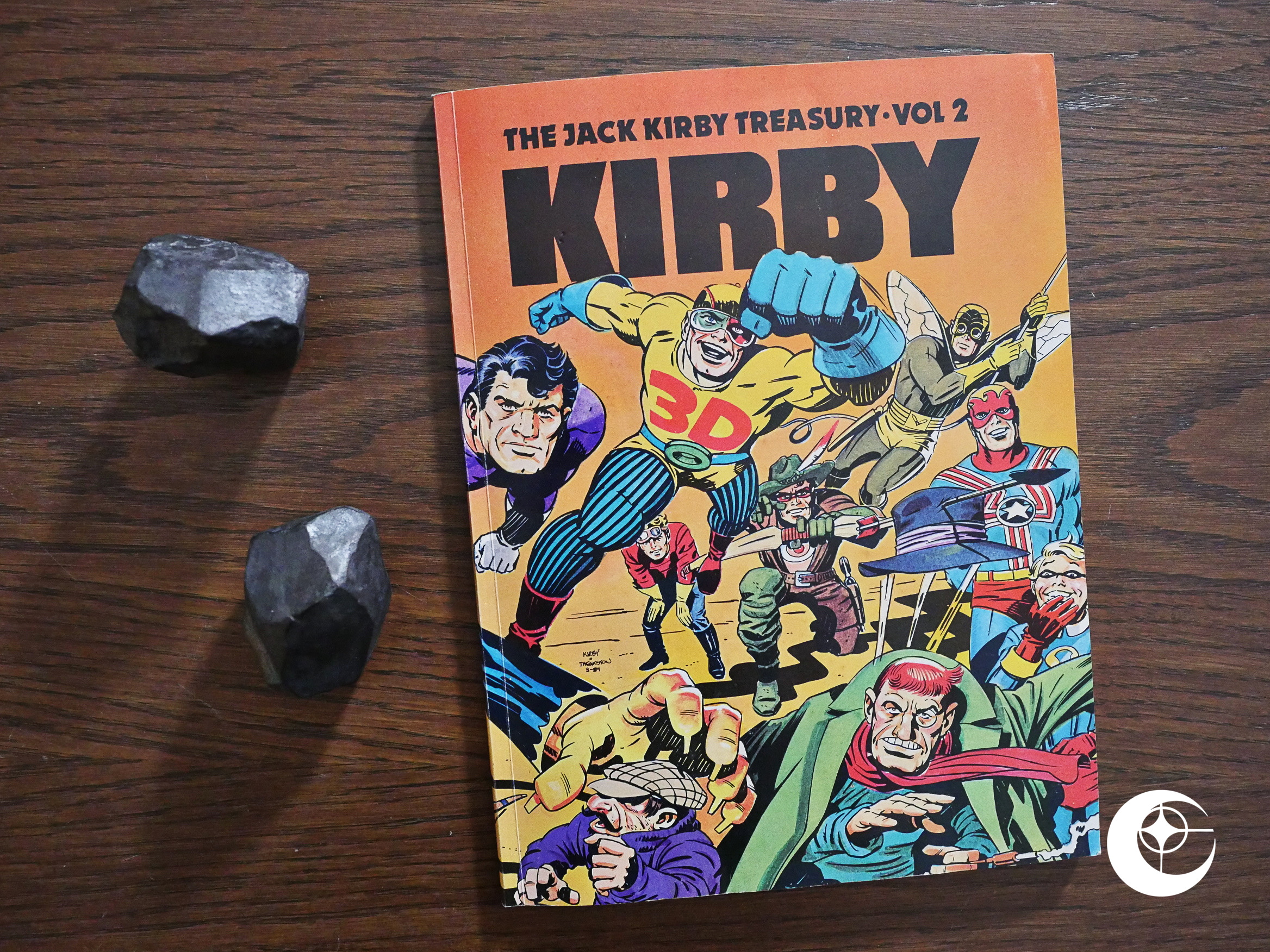

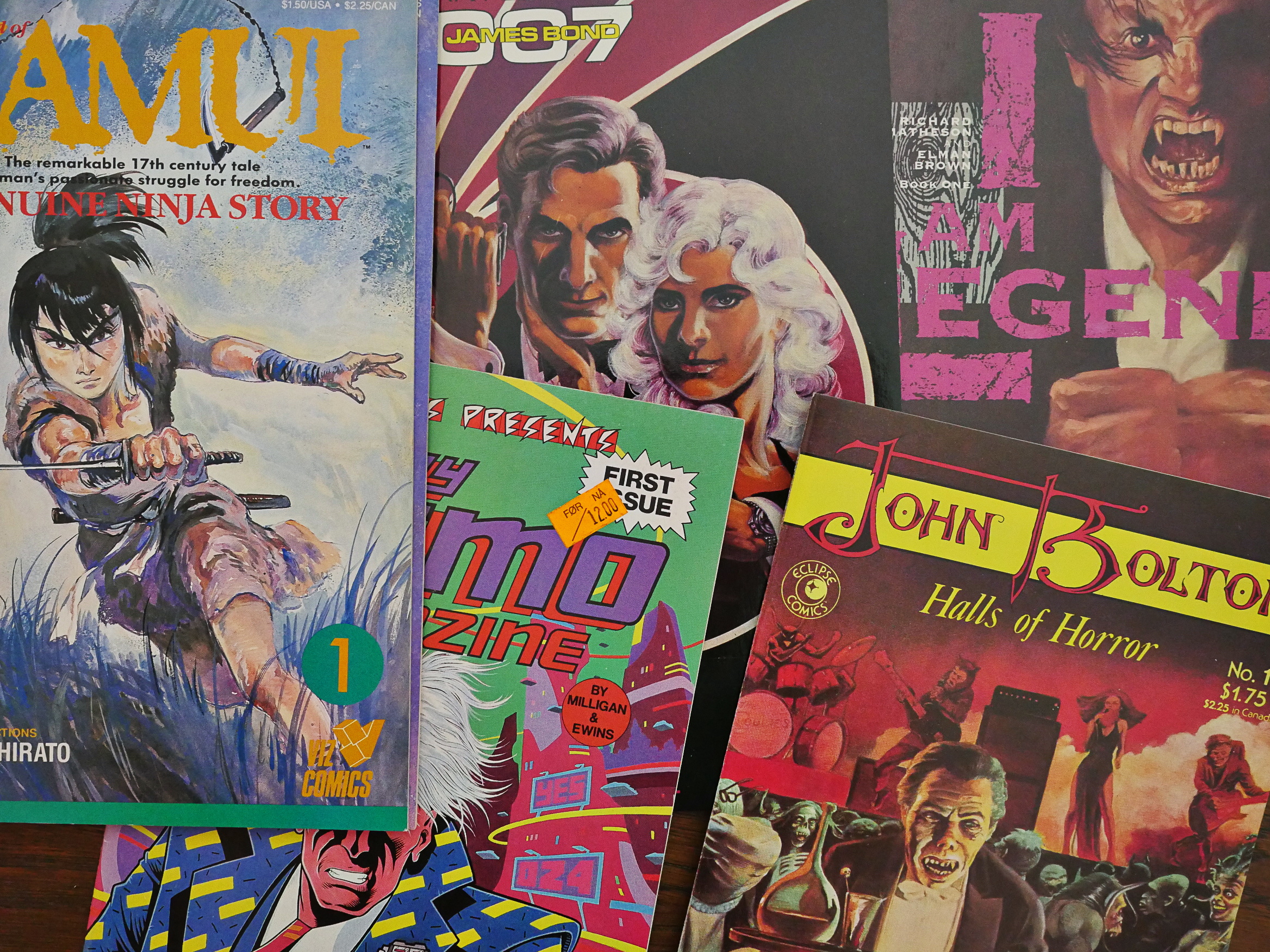

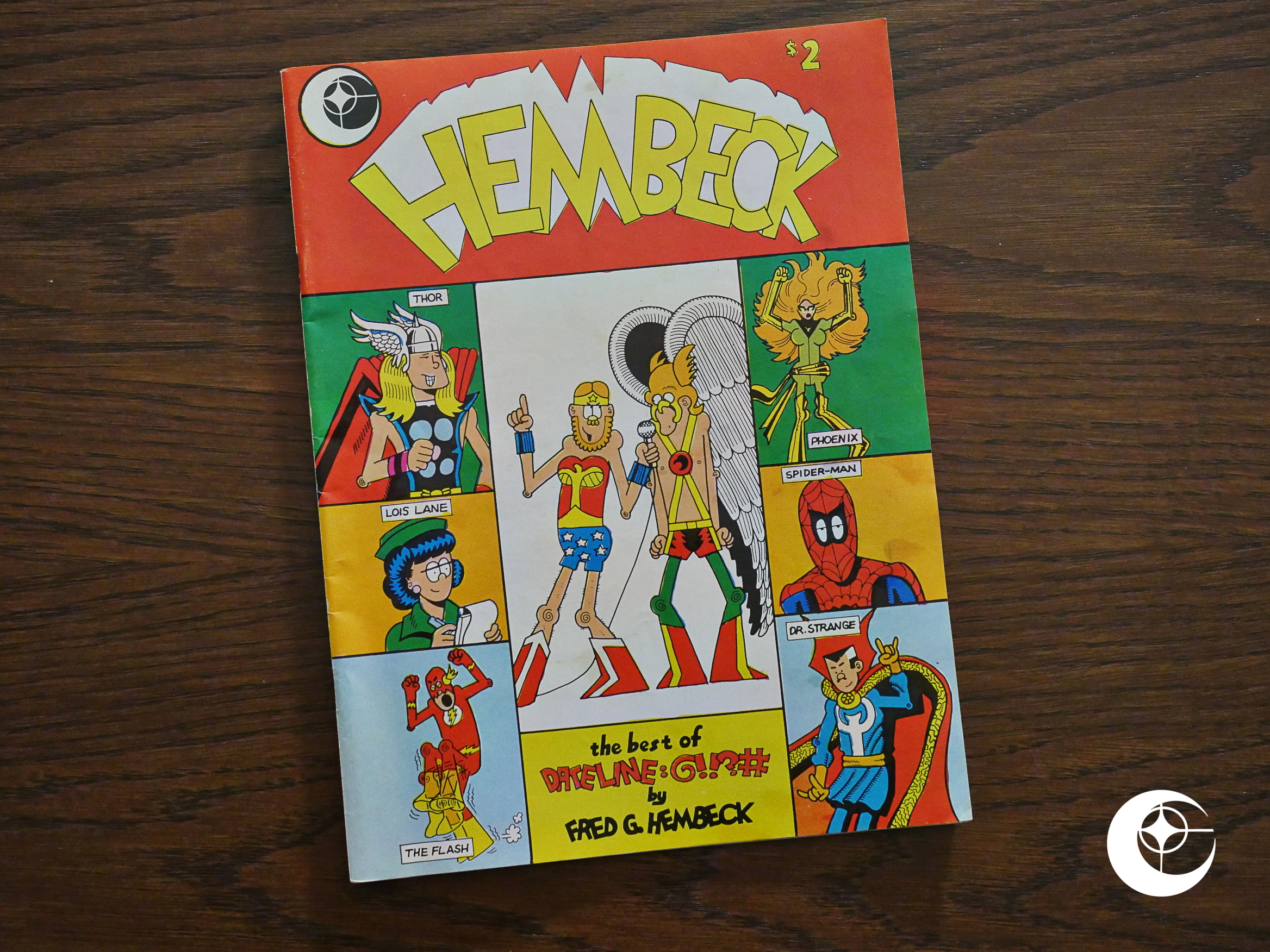

written by somebody with no association whatsoever with that publisher. Hembeck: The Best of Dateline: @!!?# (1979) #1

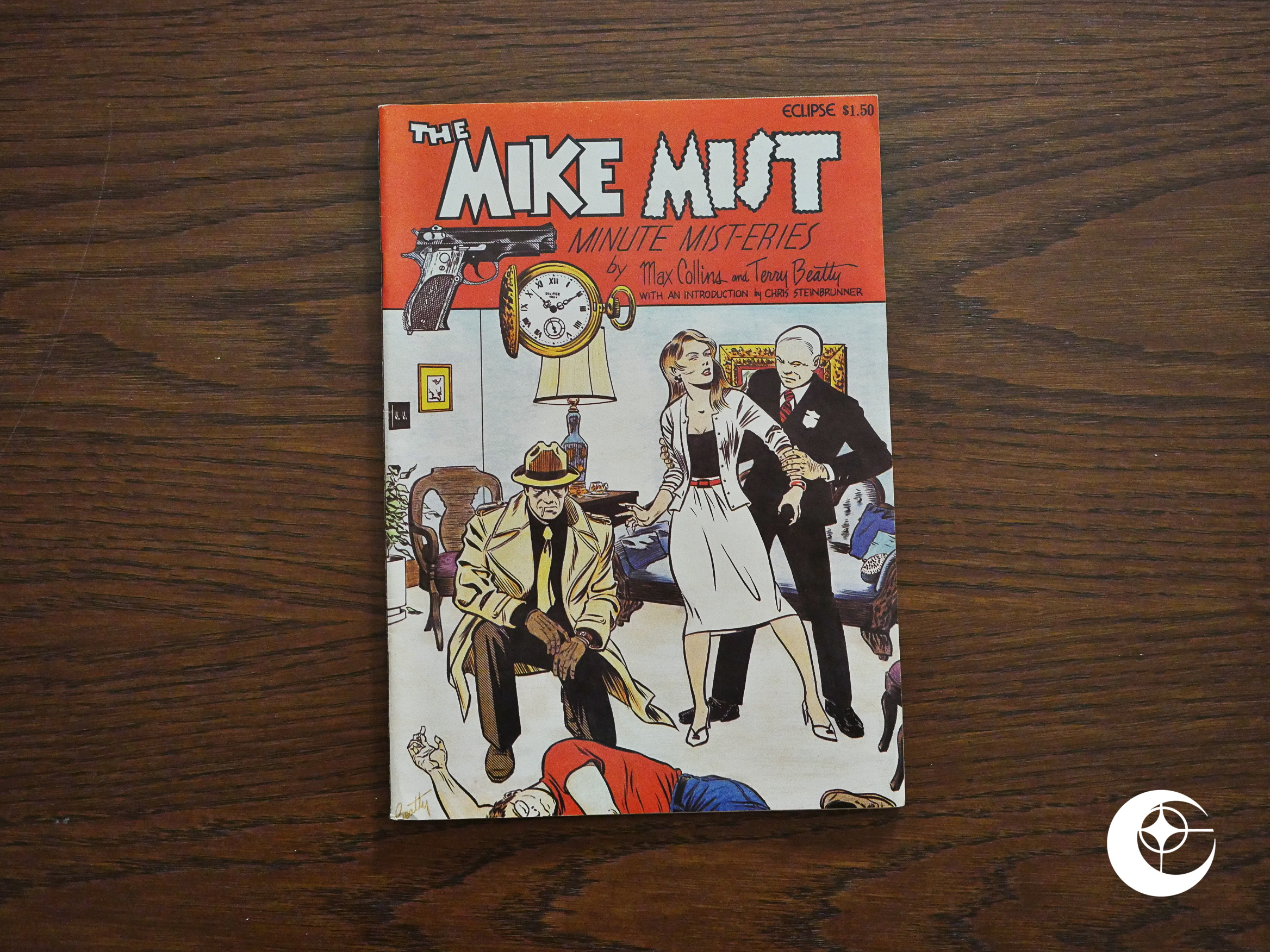

Hembeck: The Best of Dateline: @!!?# (1979) #1 The Mike Mist Minute Mist-Eries (1981) #1

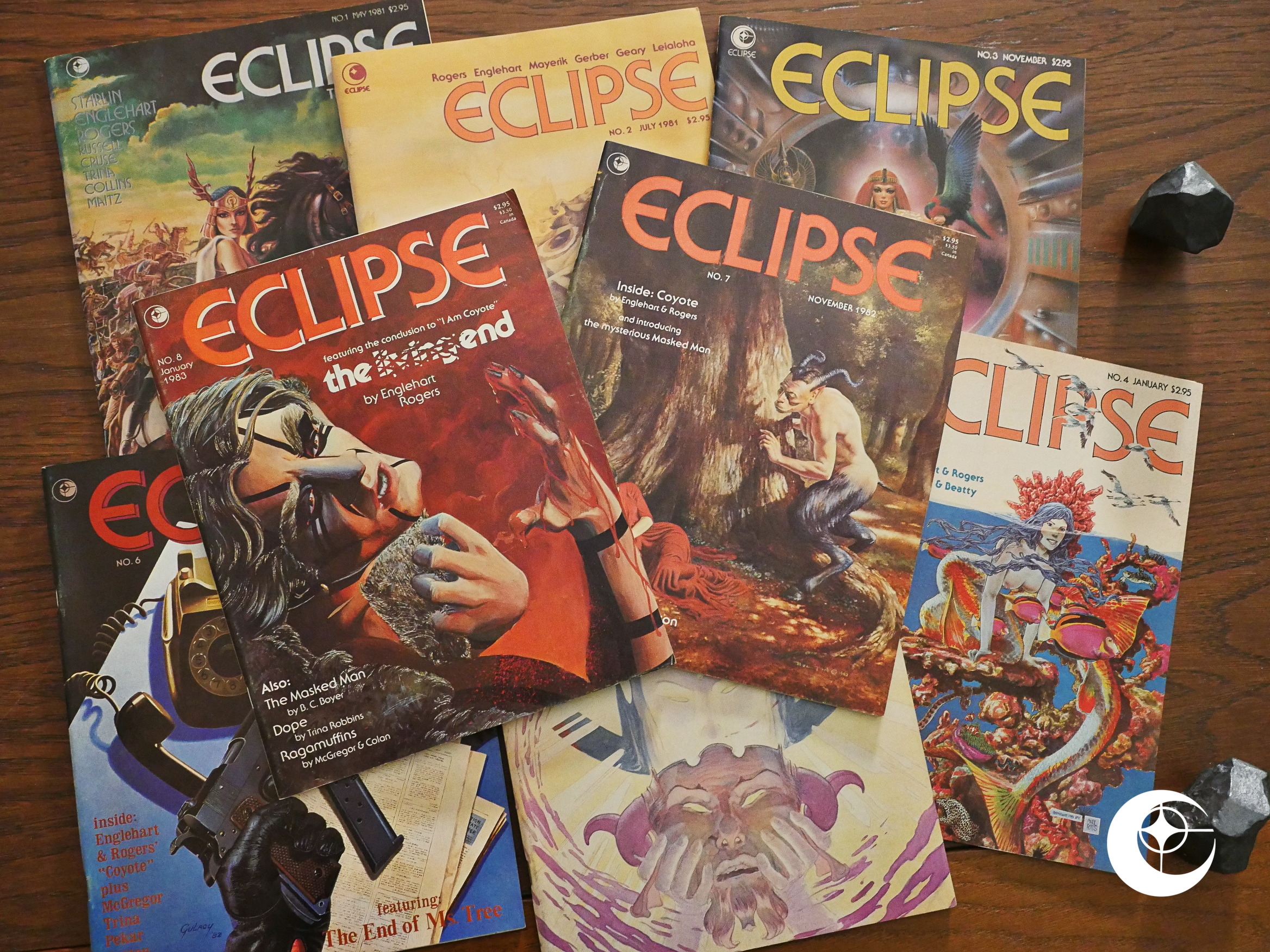

The Mike Mist Minute Mist-Eries (1981) #1 Eclipse, the Magazine (1981) #1-8

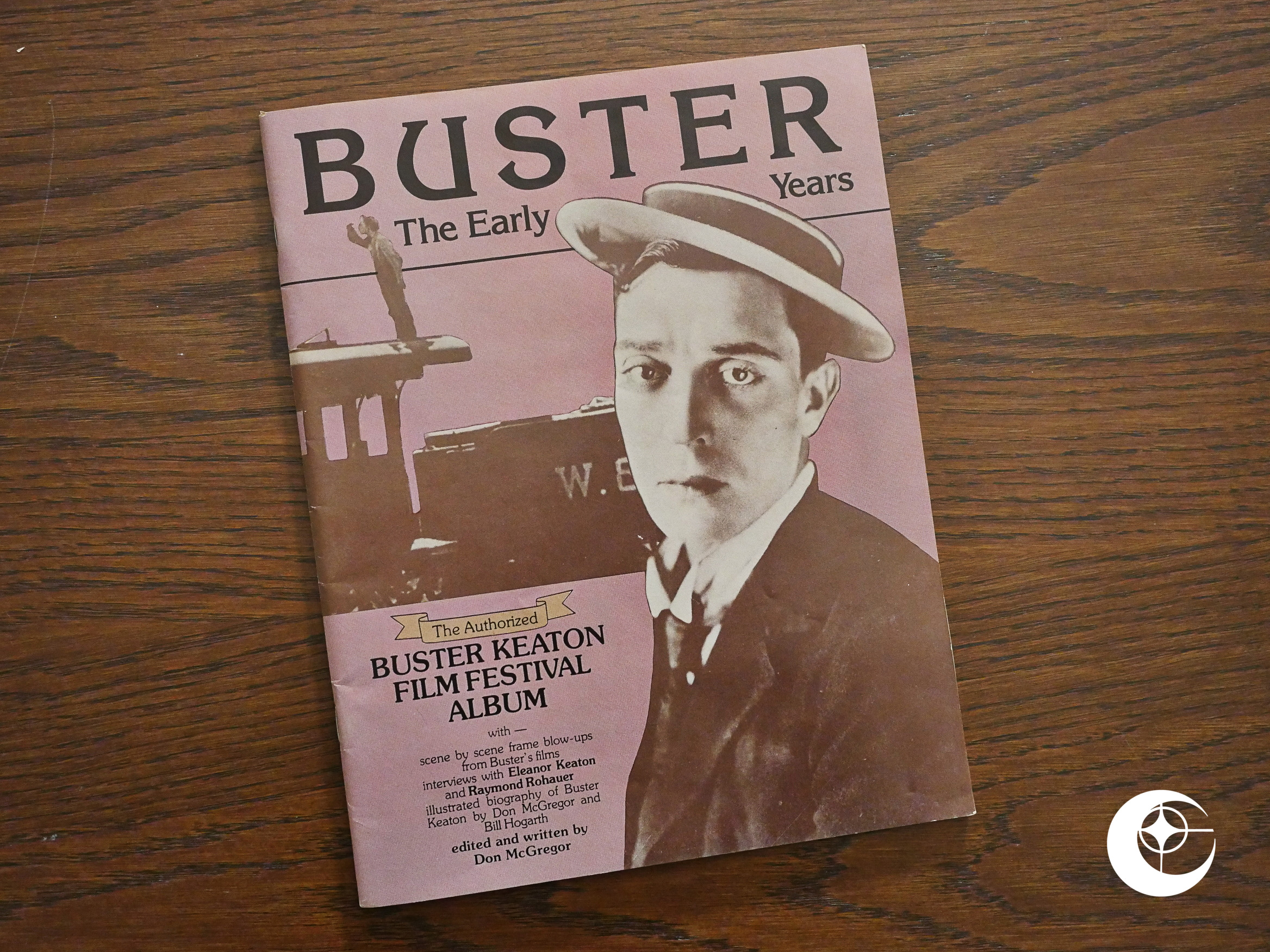

Eclipse, the Magazine (1981) #1-8 Buster Keaton (1982)

Buster Keaton (1982) Destroyer Duck (1982) #1-7

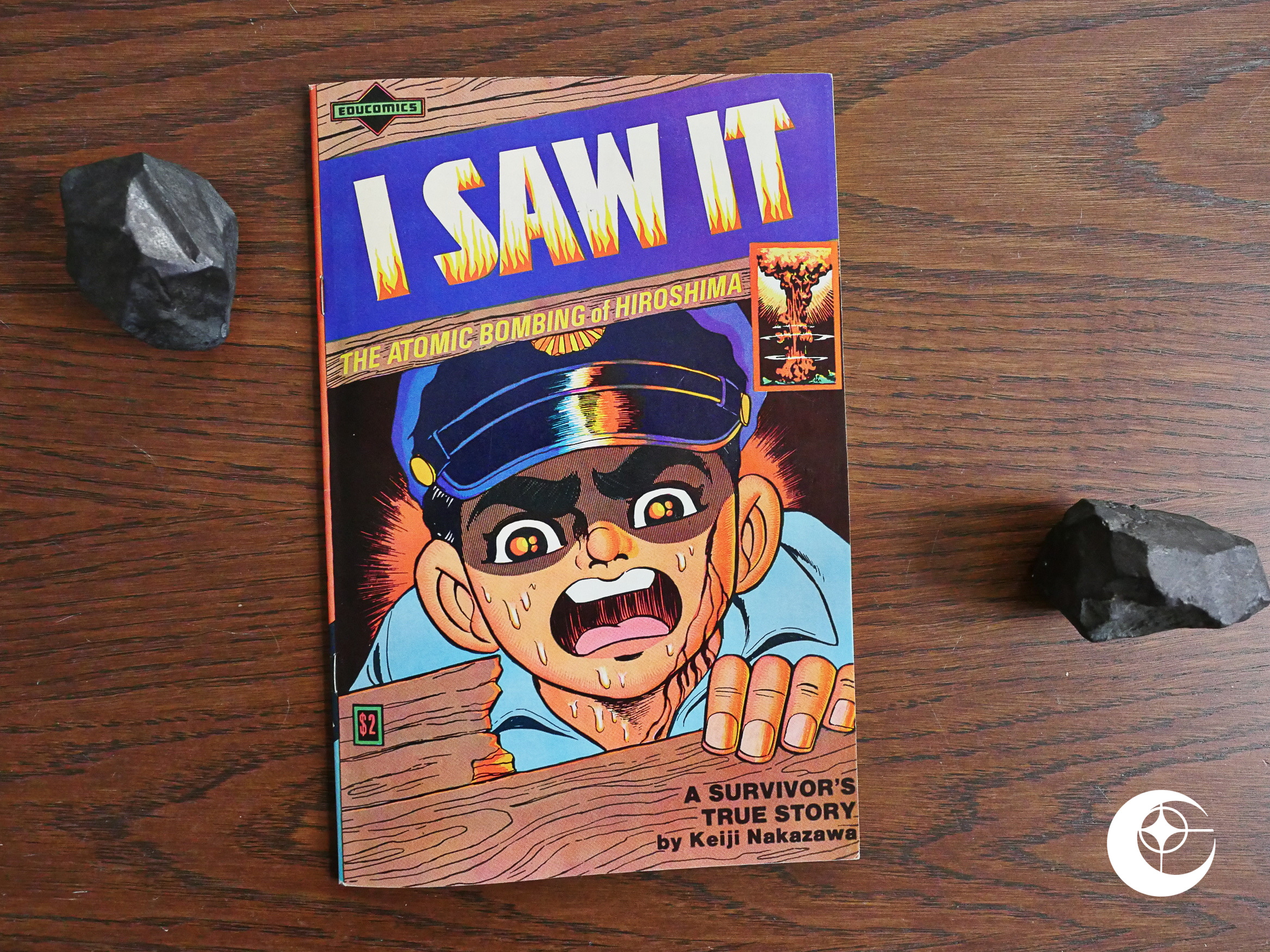

Destroyer Duck (1982) #1-7 I Saw It (1982)

I Saw It (1982) Scorpio Rose (1983) #1-2

Scorpio Rose (1983) #1-2 Ms. Tree’s Thrilling Detective Adventures (1983) #1-3

Ms. Tree’s Thrilling Detective Adventures (1983) #1-3 John Law Detective (1983) #1

John Law Detective (1983) #1 The DNAgents (1983) #1-24

The DNAgents (1983) #1-24 Eclipse Monthly (1983) #1-10

Eclipse Monthly (1983) #1-10 Aztec Ace (1984) #1-15

Aztec Ace (1984) #1-15 Star*Reach Classics (1984) #1-6

Star*Reach Classics (1984) #1-6 Crossfire (1984) #1-26

Crossfire (1984) #1-26 Cap’n Quick & a Foozle (1984) #1-2

Cap’n Quick & a Foozle (1984) #1-2 Groo Special (1984) #1

Groo Special (1984) #1 Axel Pressbutton (1984) #1-6

Axel Pressbutton (1984) #1-6 Siegel and Shuster: Dateline 1930s (1984) #1-2

Siegel and Shuster: Dateline 1930s (1984) #1-2 Sun-Runners (1984) #4-7

Sun-Runners (1984) #4-7 Strange Days (1984) #1-3

Strange Days (1984) #1-3 Berni Wrightson, Master of the Macabre (1984) #5

Berni Wrightson, Master of the Macabre (1984) #5 The Masked Man (1984) #1-12

The Masked Man (1984) #1-12 Doc Stearn…Mr. Monster (1985) #1-10

Doc Stearn…Mr. Monster (1985) #1-10 Ragamuffins (1985) #1

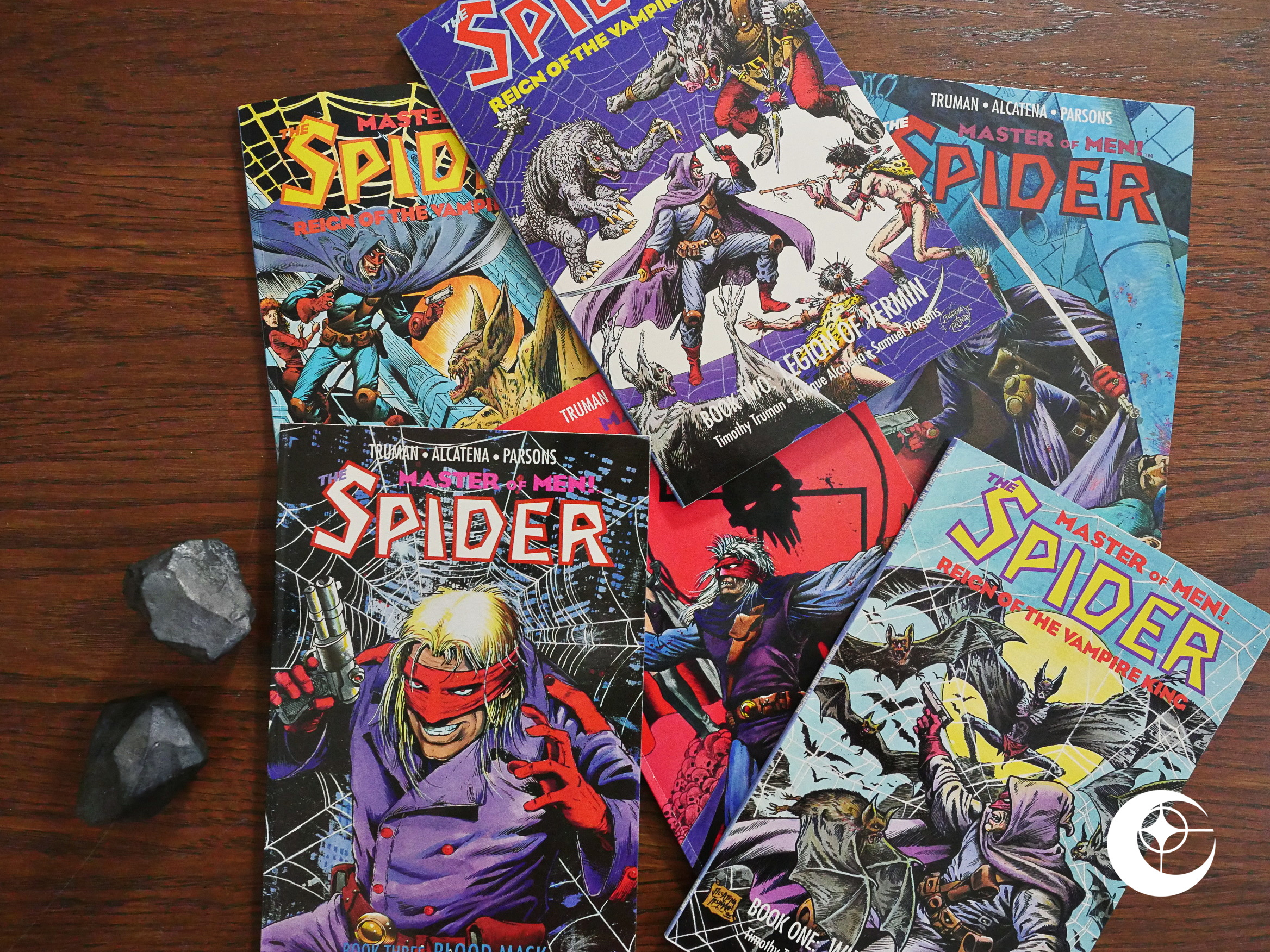

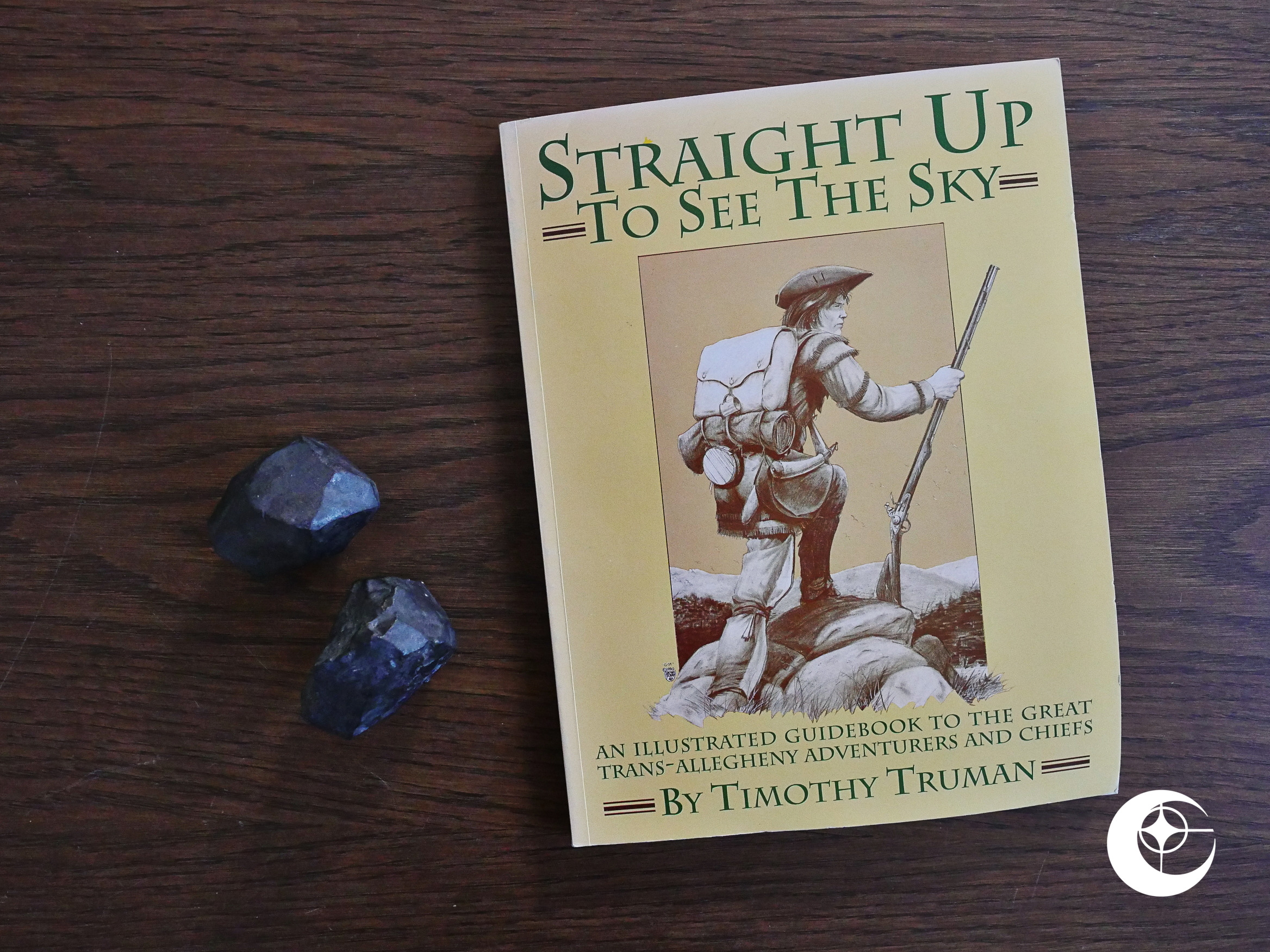

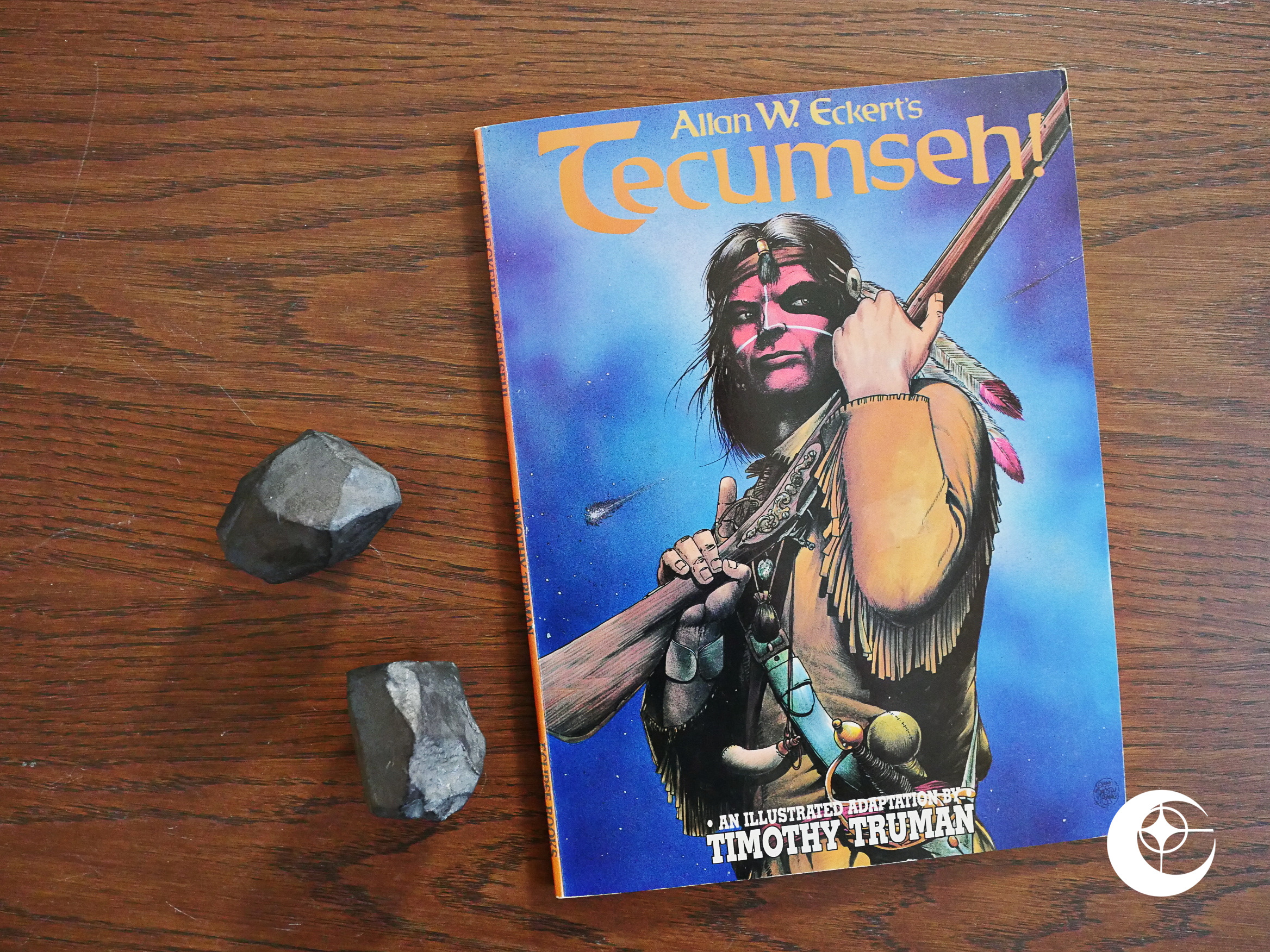

Ragamuffins (1985) #1 Killer… Tales by Timothy Truman (1985) #1

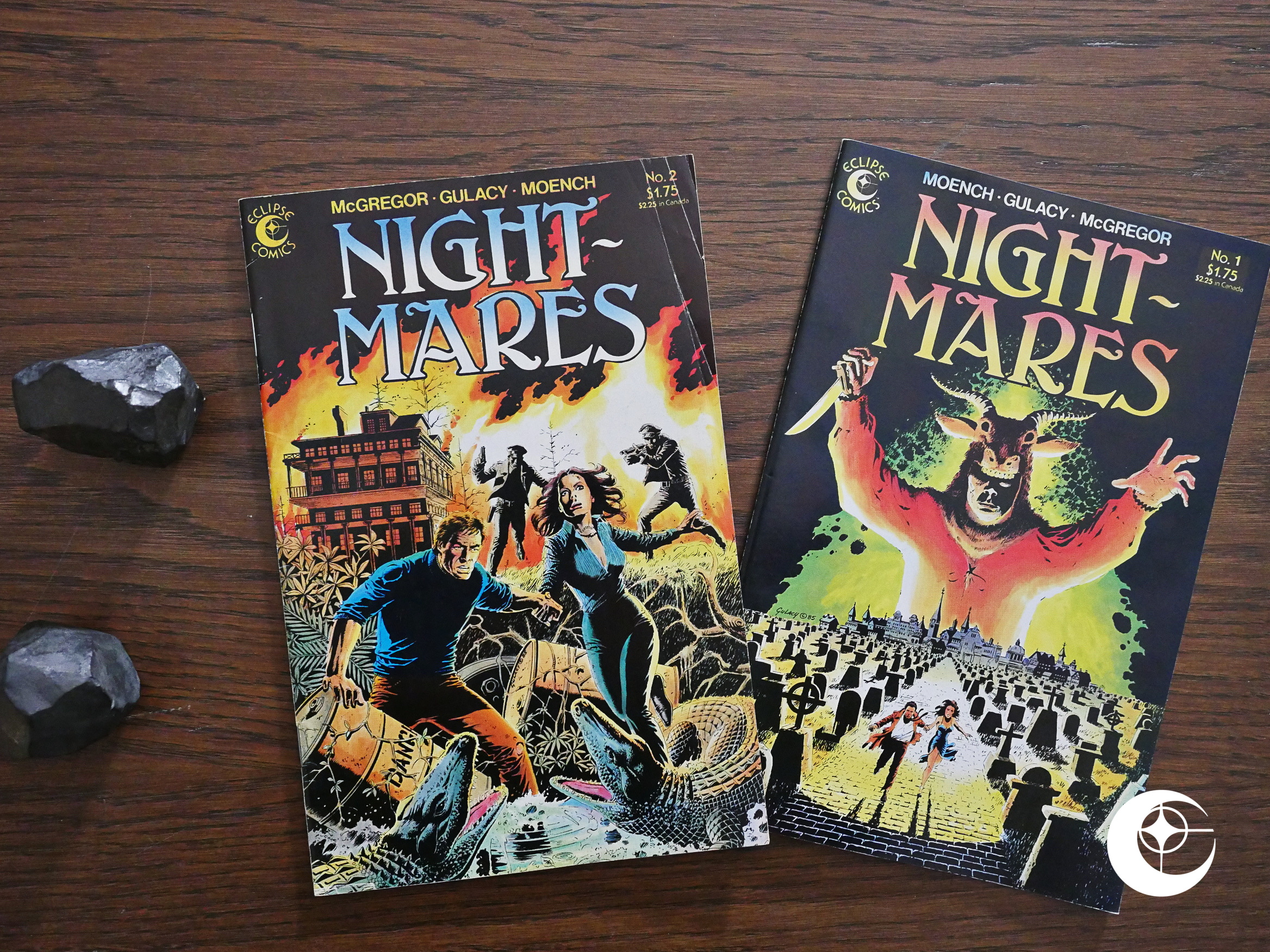

Killer… Tales by Timothy Truman (1985) #1 Nightmares (1985) #1-2

Nightmares (1985) #1-2 Alien Encounters (1985) #1-14

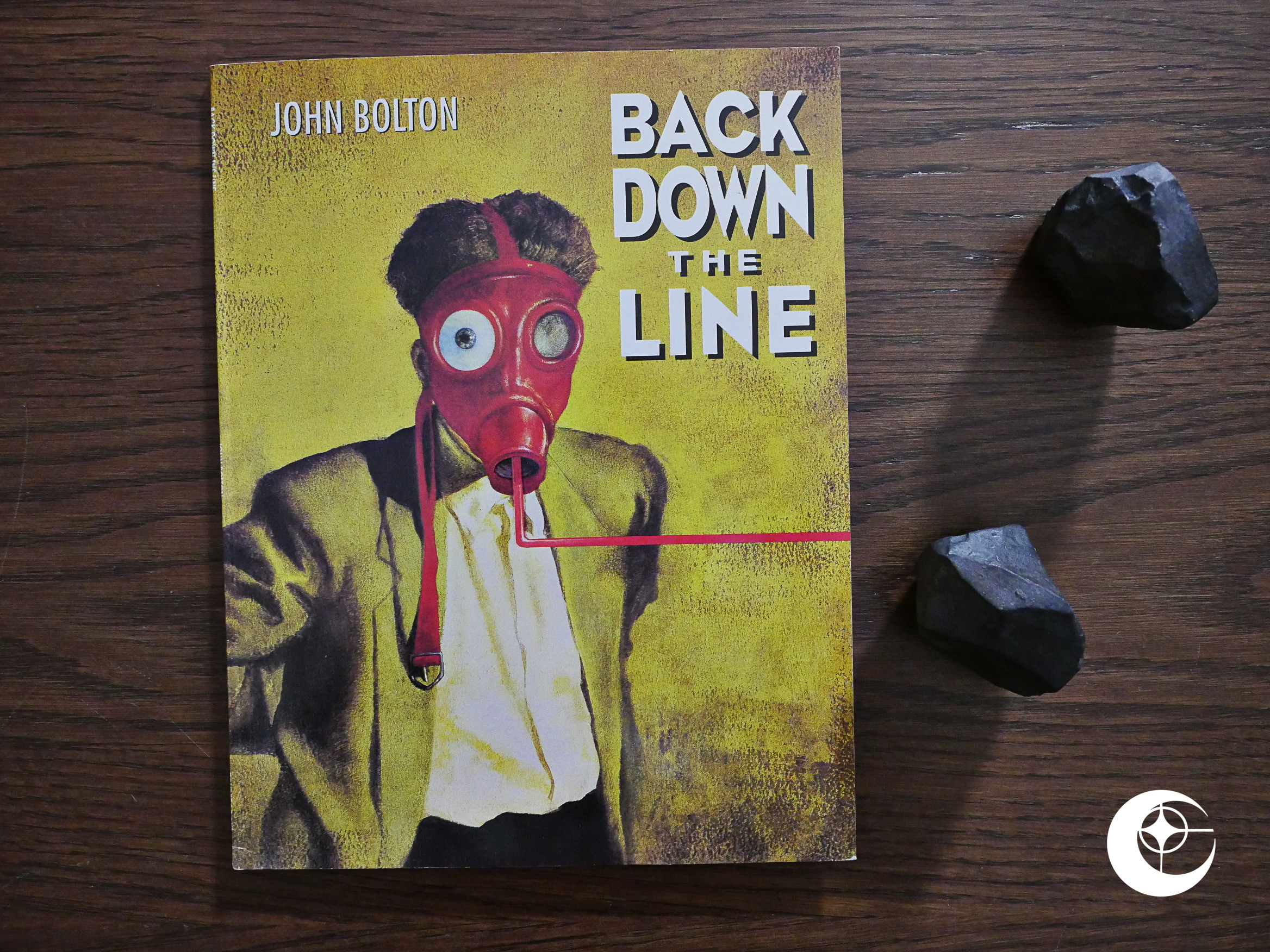

Alien Encounters (1985) #1-14 John Bolton’s Halls of Horror (1985) #1-2

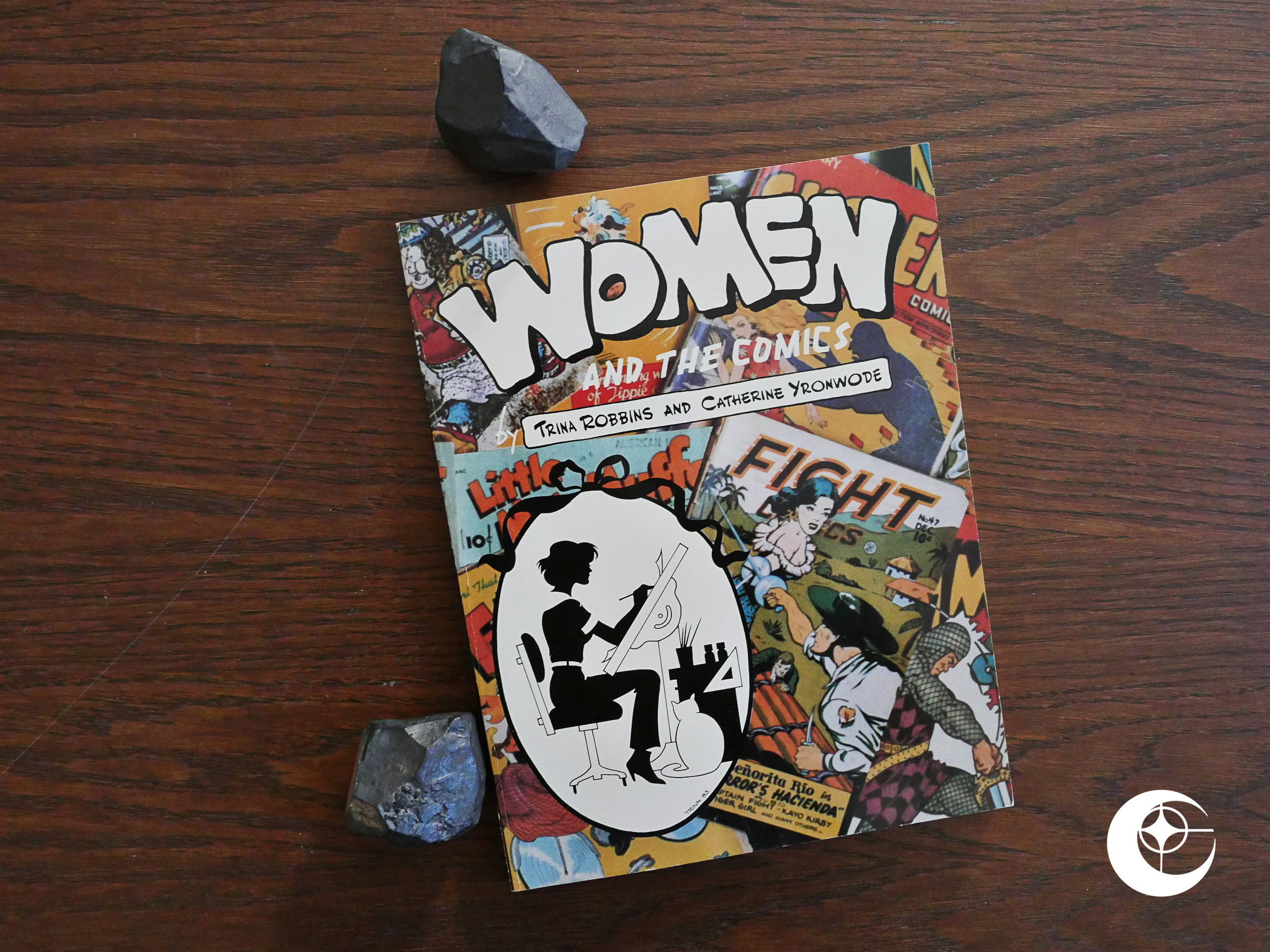

John Bolton’s Halls of Horror (1985) #1-2 Women and the Comics (1985) #1

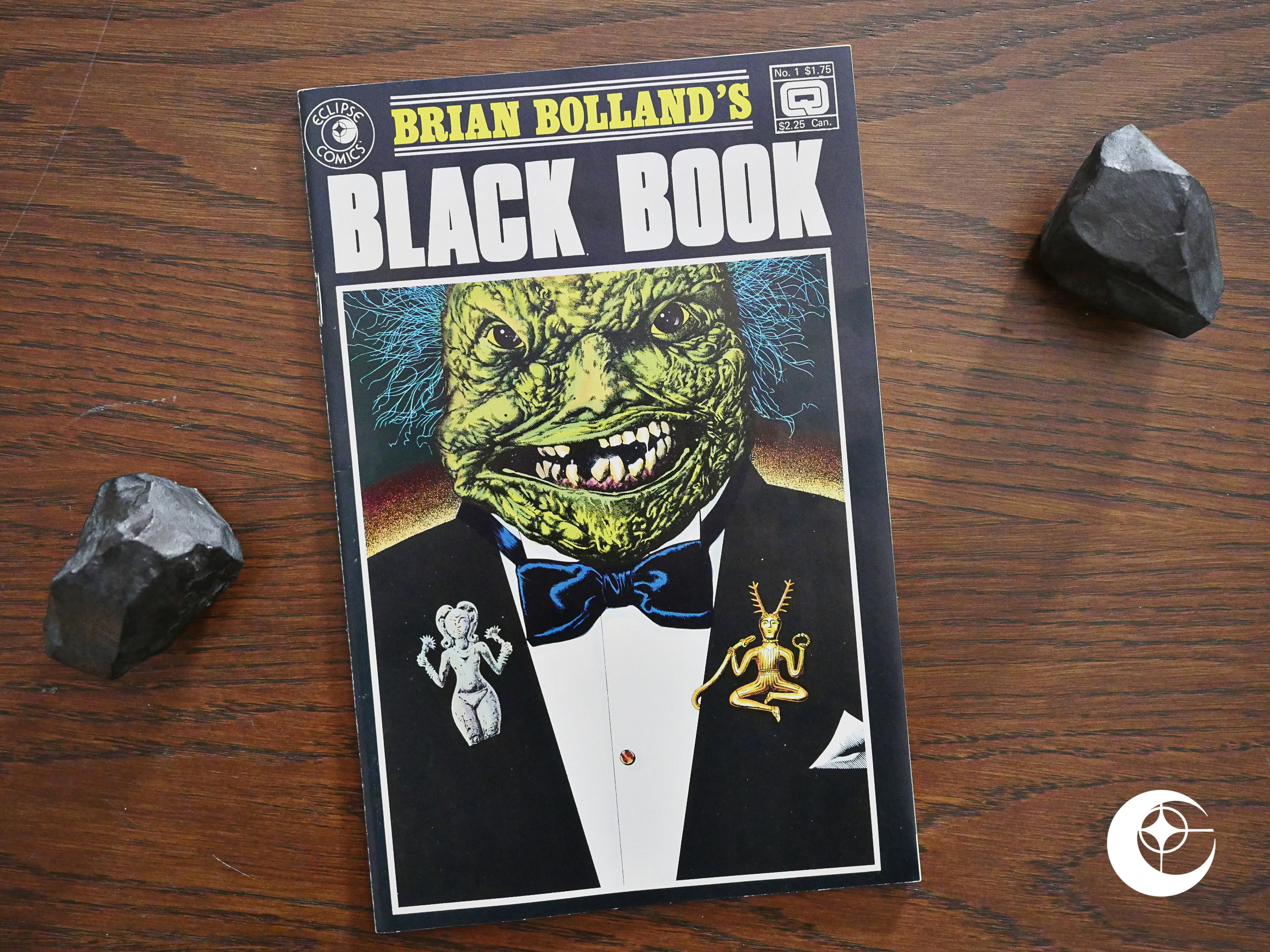

Women and the Comics (1985) #1 Brian Bolland’s Black Book (1985) #1

Brian Bolland’s Black Book (1985) #1 Tales of Terror (1985) #1-13

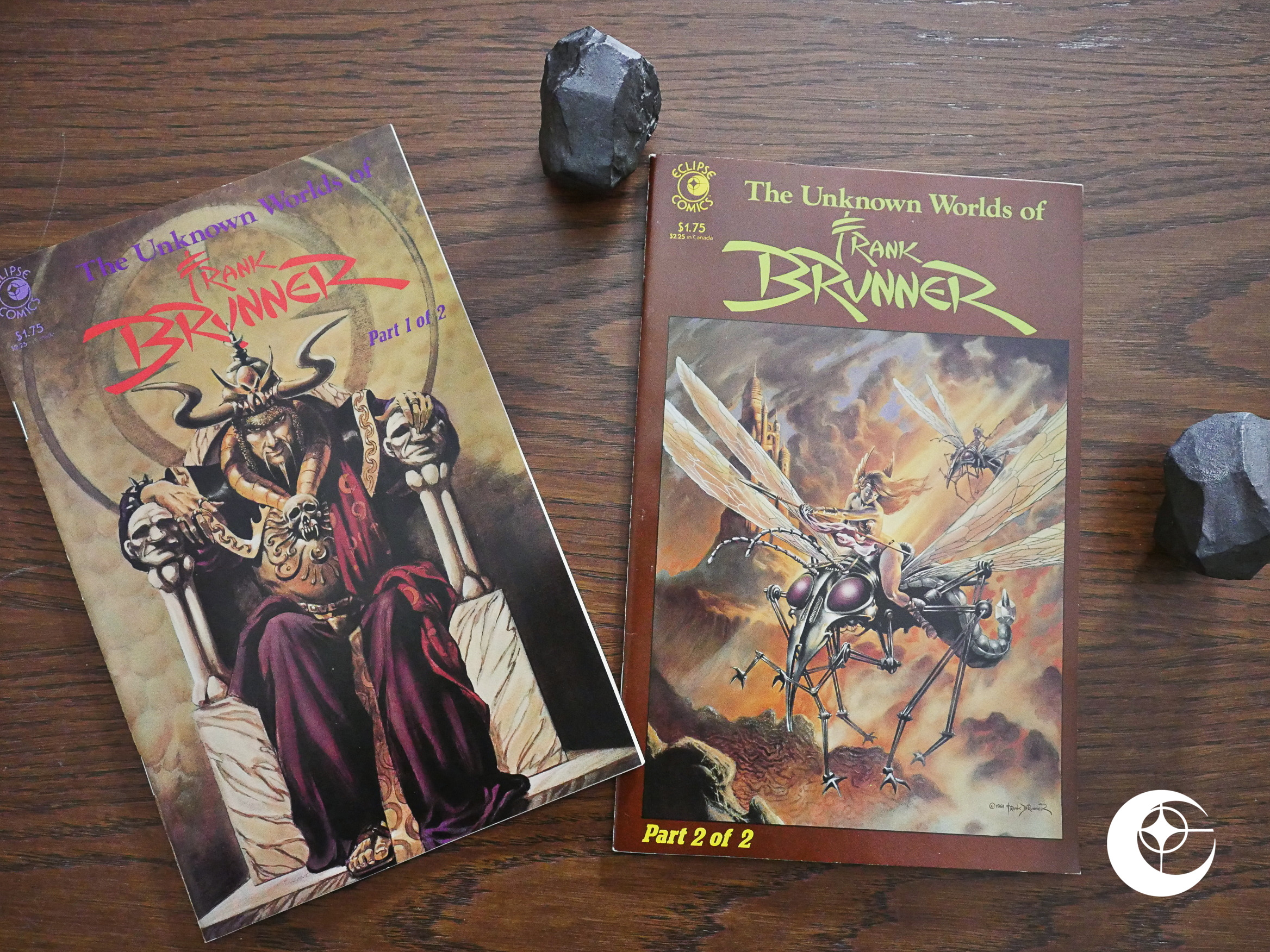

Tales of Terror (1985) #1-13 The Unknown Worlds of Frank Brunner (1985) #1-2

The Unknown Worlds of Frank Brunner (1985) #1-2 Bedlam (1985) #1-2

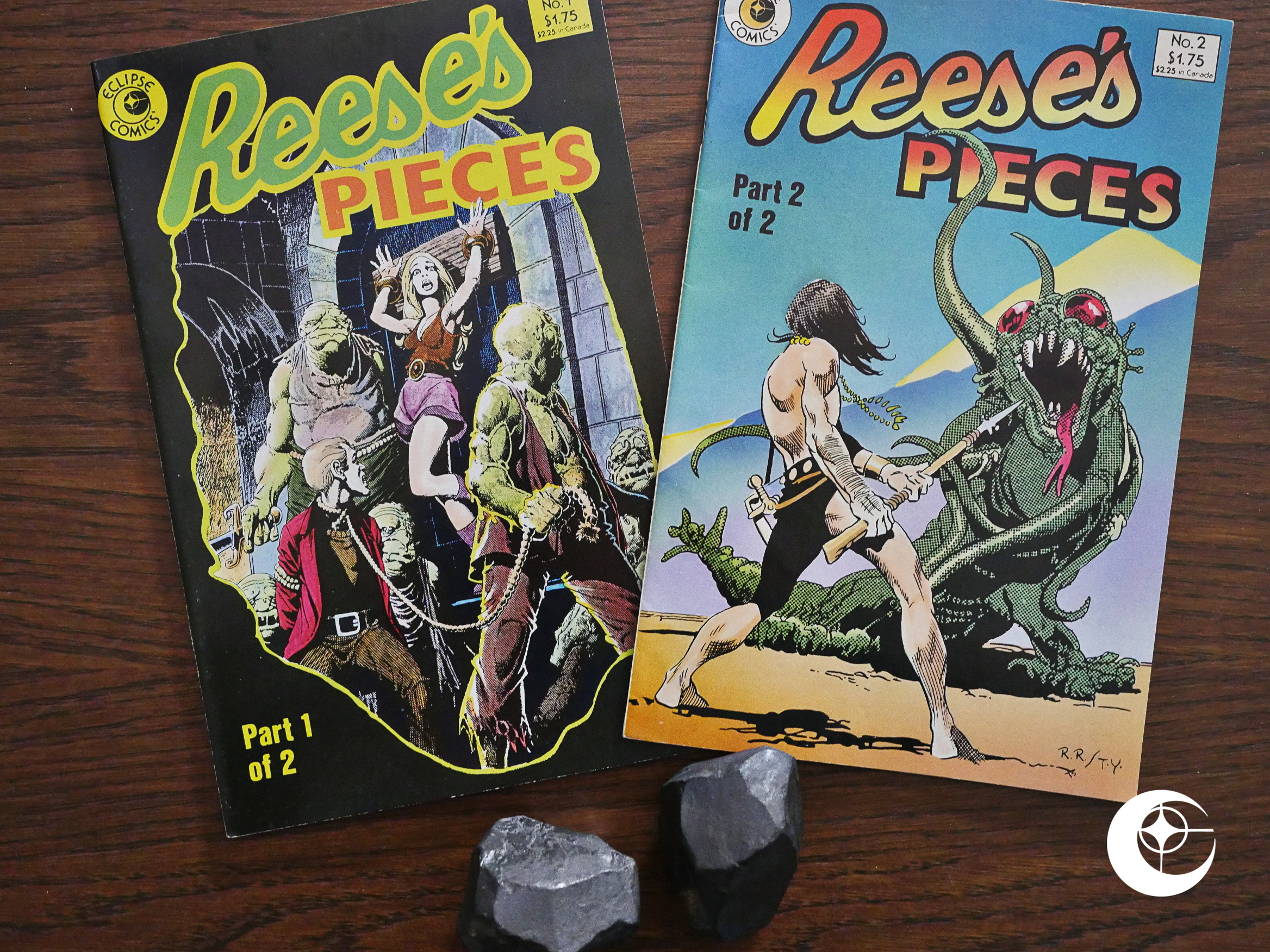

Bedlam (1985) #1-2 Reese’s Pieces (1985) #1-2

Reese’s Pieces (1985) #1-2 Seduction of the Innocent 3-D (1985) #1-2

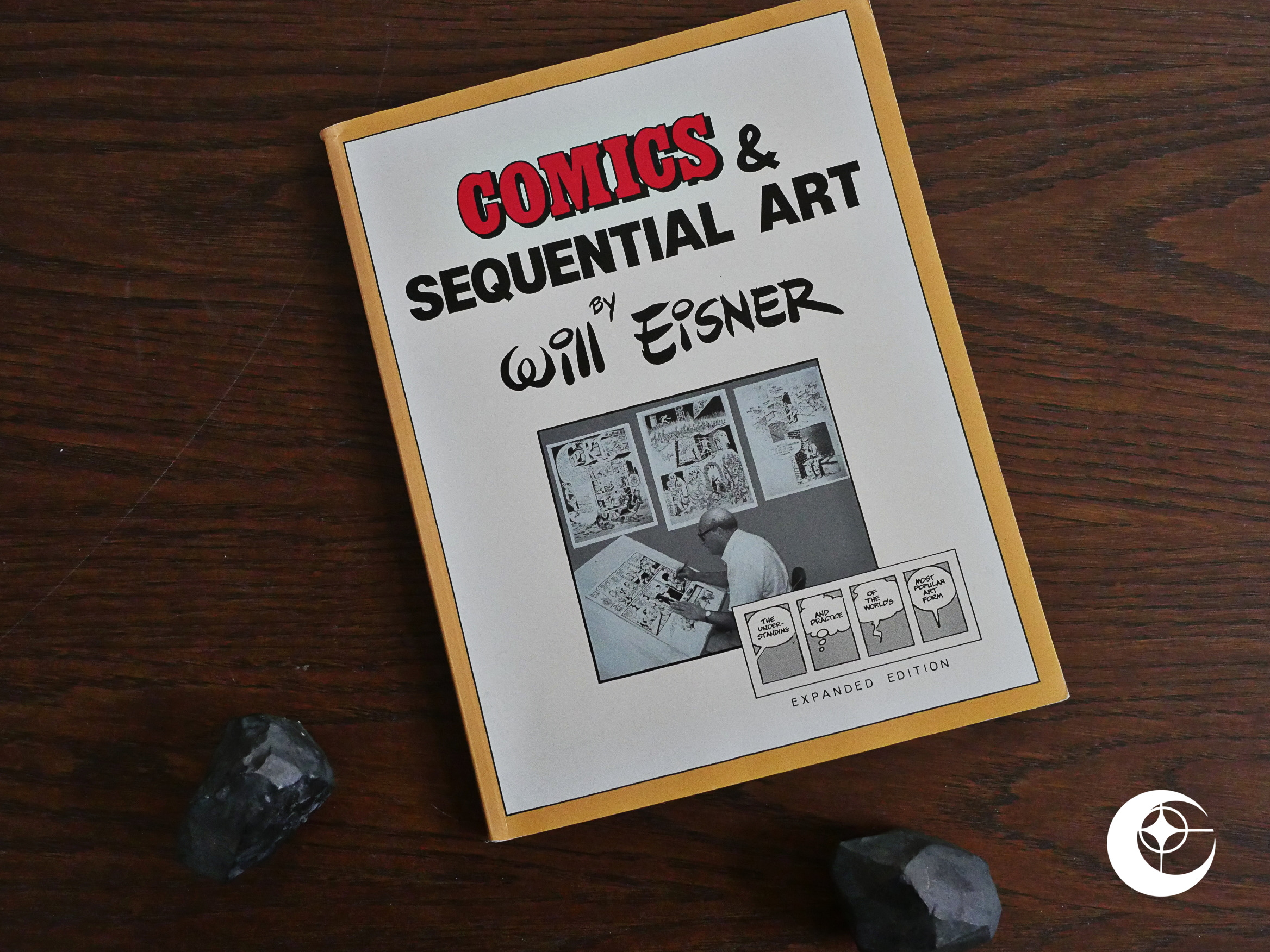

Seduction of the Innocent 3-D (1985) #1-2 Comics & Sequential Art (1985) #1

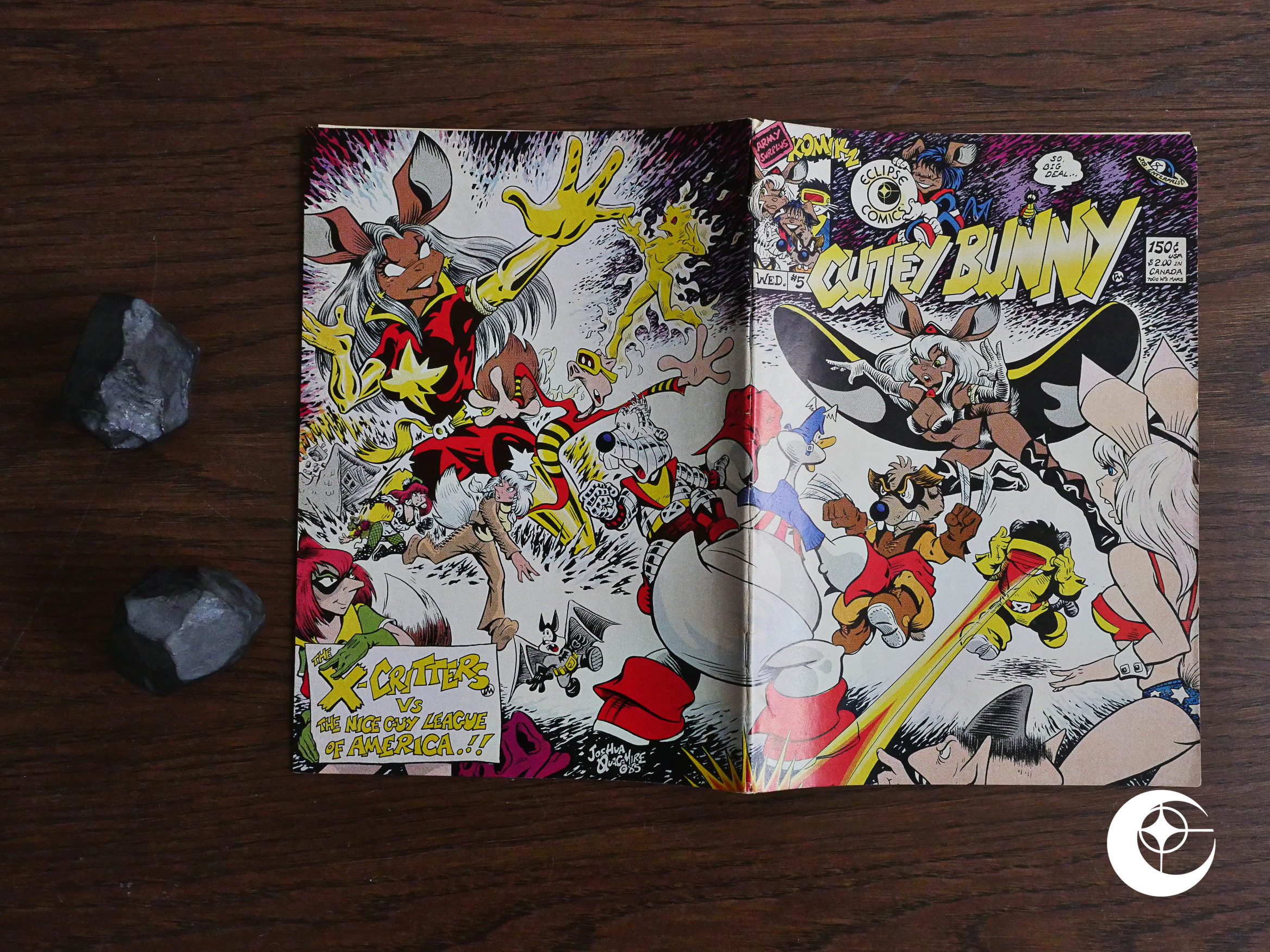

Comics & Sequential Art (1985) #1 Army Surplus Komikz Featuring: Cutey Bunny (1985) #5

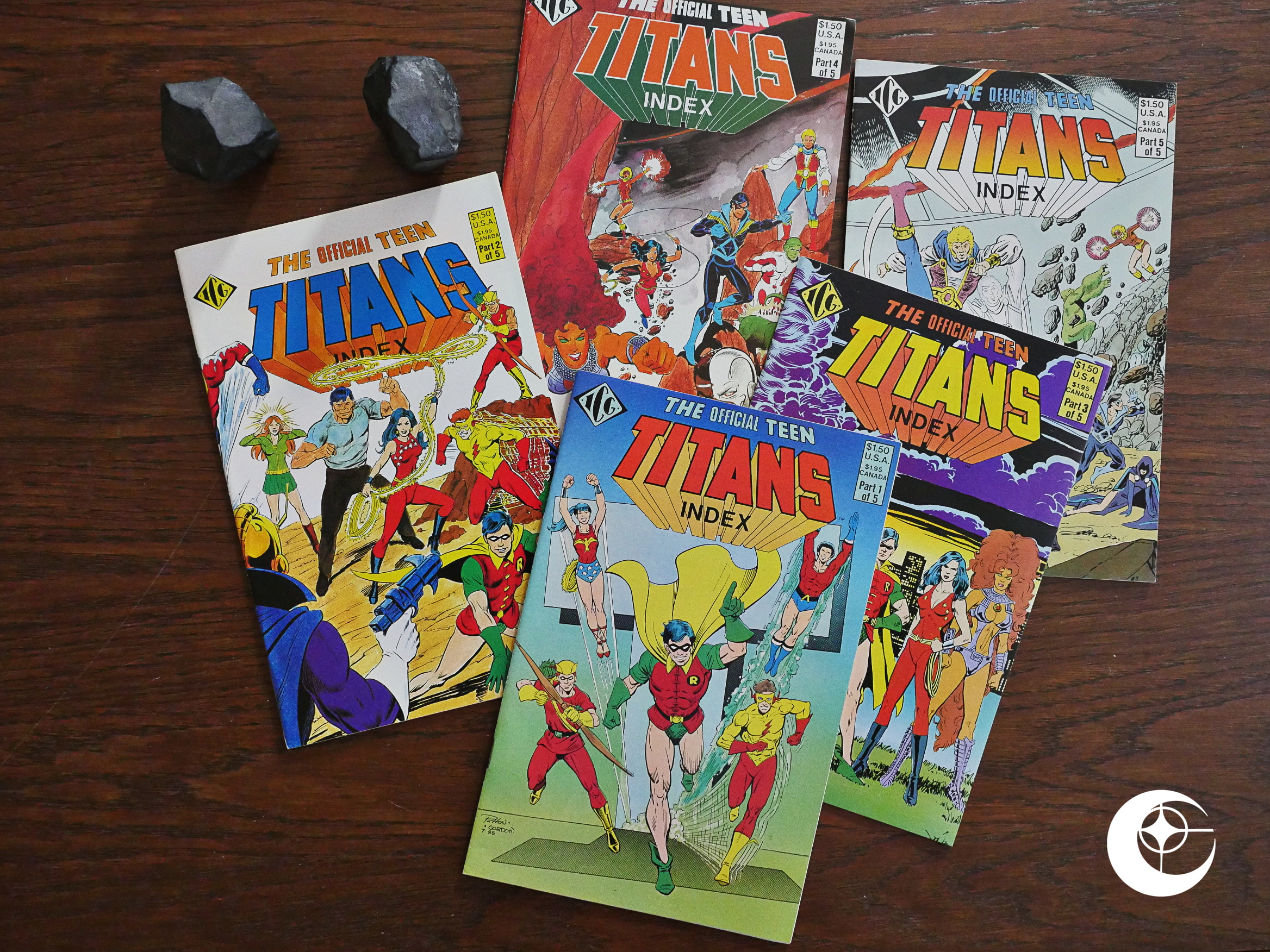

Army Surplus Komikz Featuring: Cutey Bunny (1985) #5 The Official Teen Titans Index (1985) #1-5

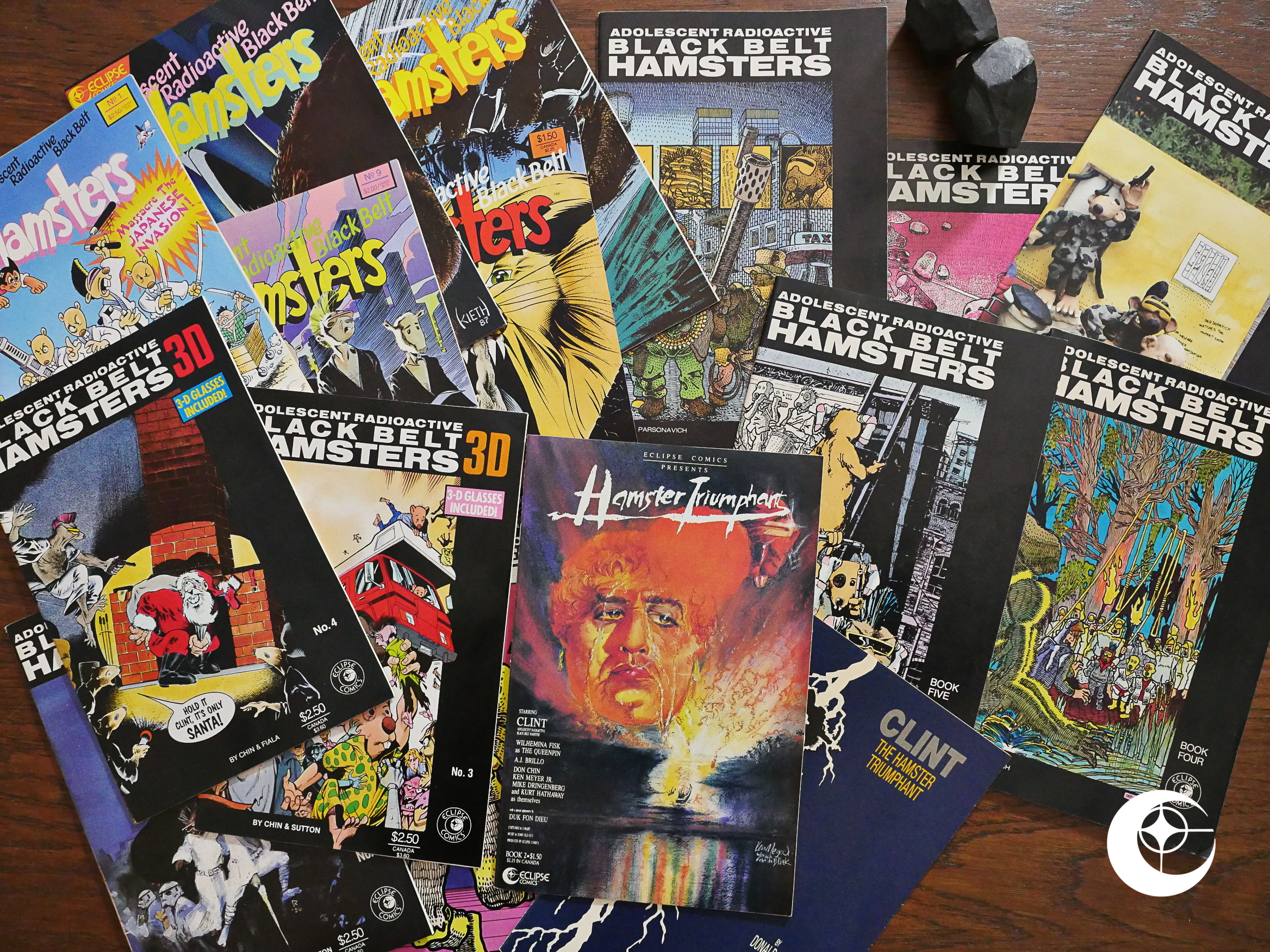

The Official Teen Titans Index (1985) #1-5 Adolescent Radioactive Black Belt Hamsters (1986) #1-9

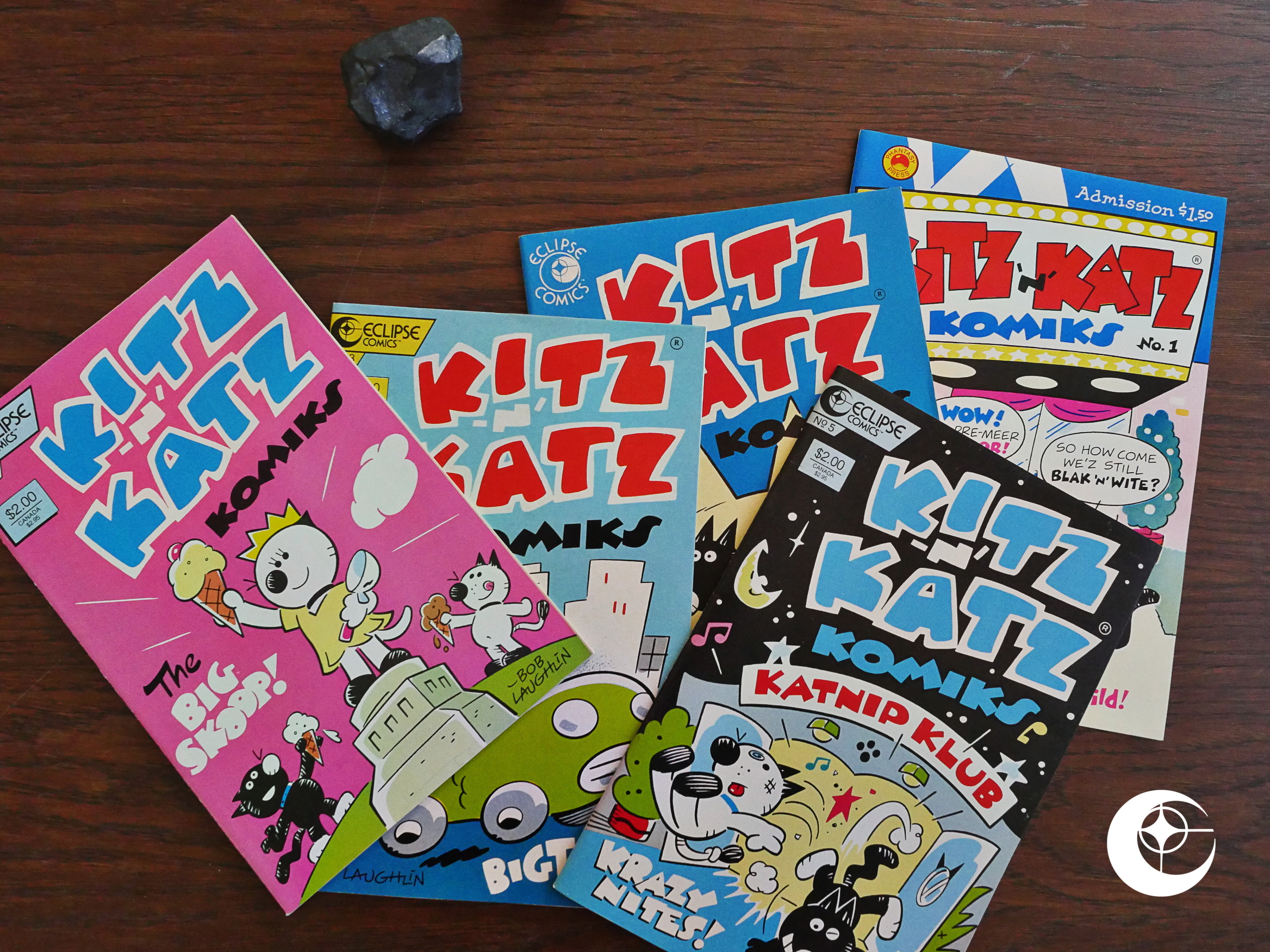

Adolescent Radioactive Black Belt Hamsters (1986) #1-9 Kitz ‘n’ Katz Komiks (1986) #1-4

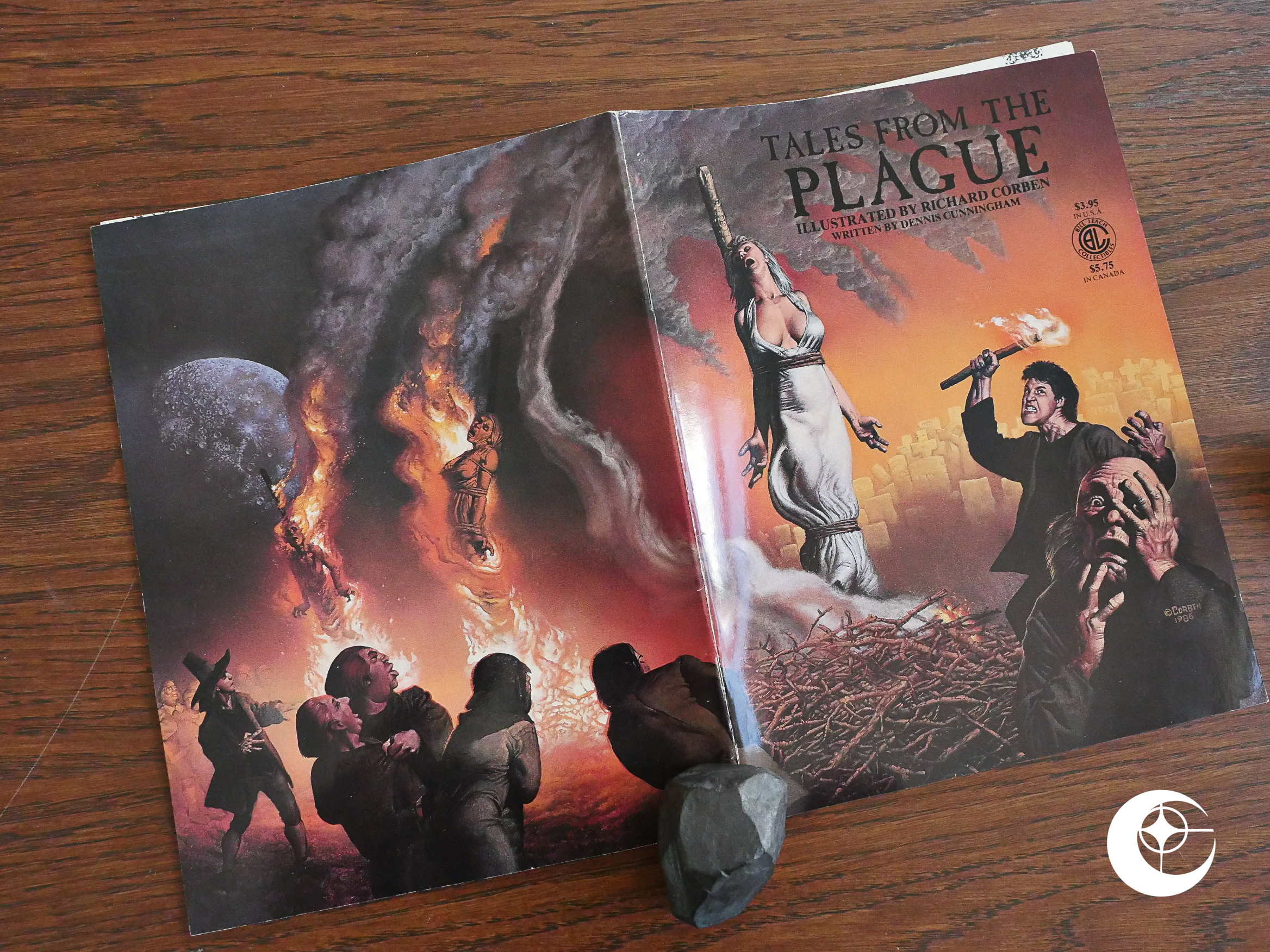

Kitz ‘n’ Katz Komiks (1986) #1-4 Tales from the Plague (1986) #1

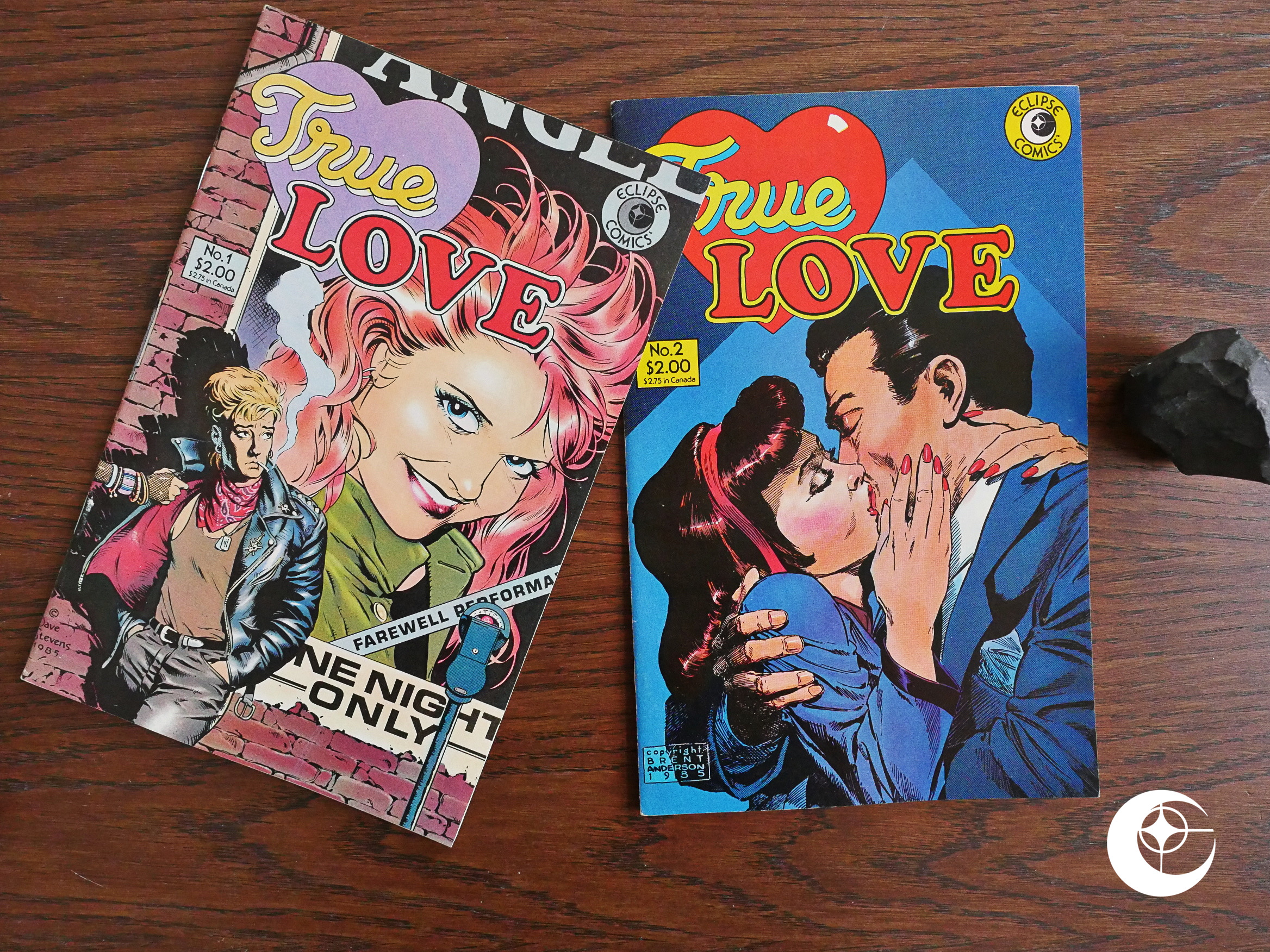

Tales from the Plague (1986) #1 True Love (1986) #1-2

True Love (1986) #1-2 World of Wood (1986) #1-5

World of Wood (1986) #1-5 Champions (1986) #1-6

Champions (1986) #1-6 The New Wave (1986) #1-13

The New Wave (1986) #1-13 Espers (1986) #1-5

Espers (1986) #1-5 The Spiral Path (1986) #1-2

The Spiral Path (1986) #1-2 Tor 3-D (1986) #1-2

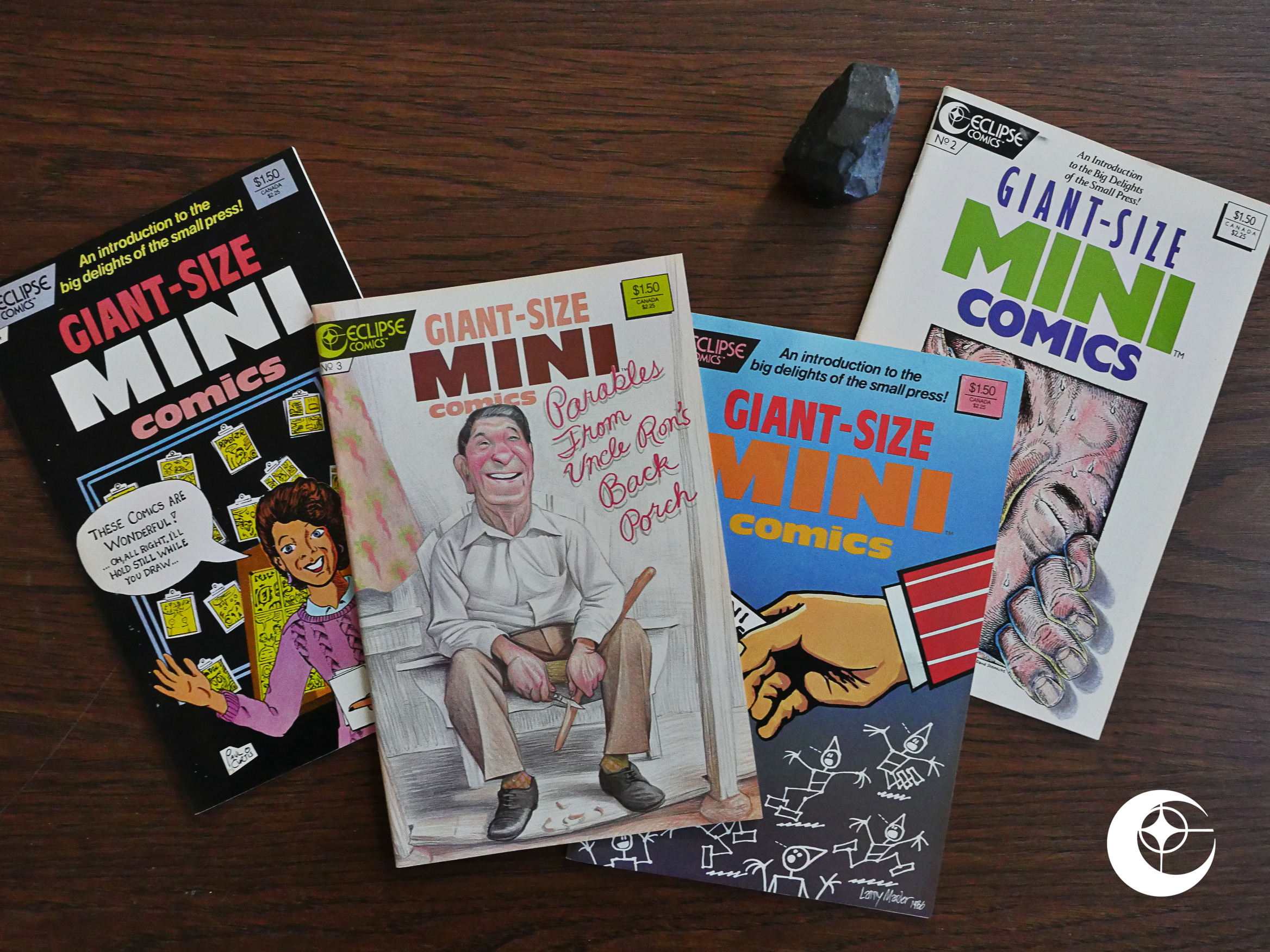

Tor 3-D (1986) #1-2 Giant-Size Mini Comics (1986) #1-4

Giant-Size Mini Comics (1986) #1-4 Zooniverse (1986) #1-6

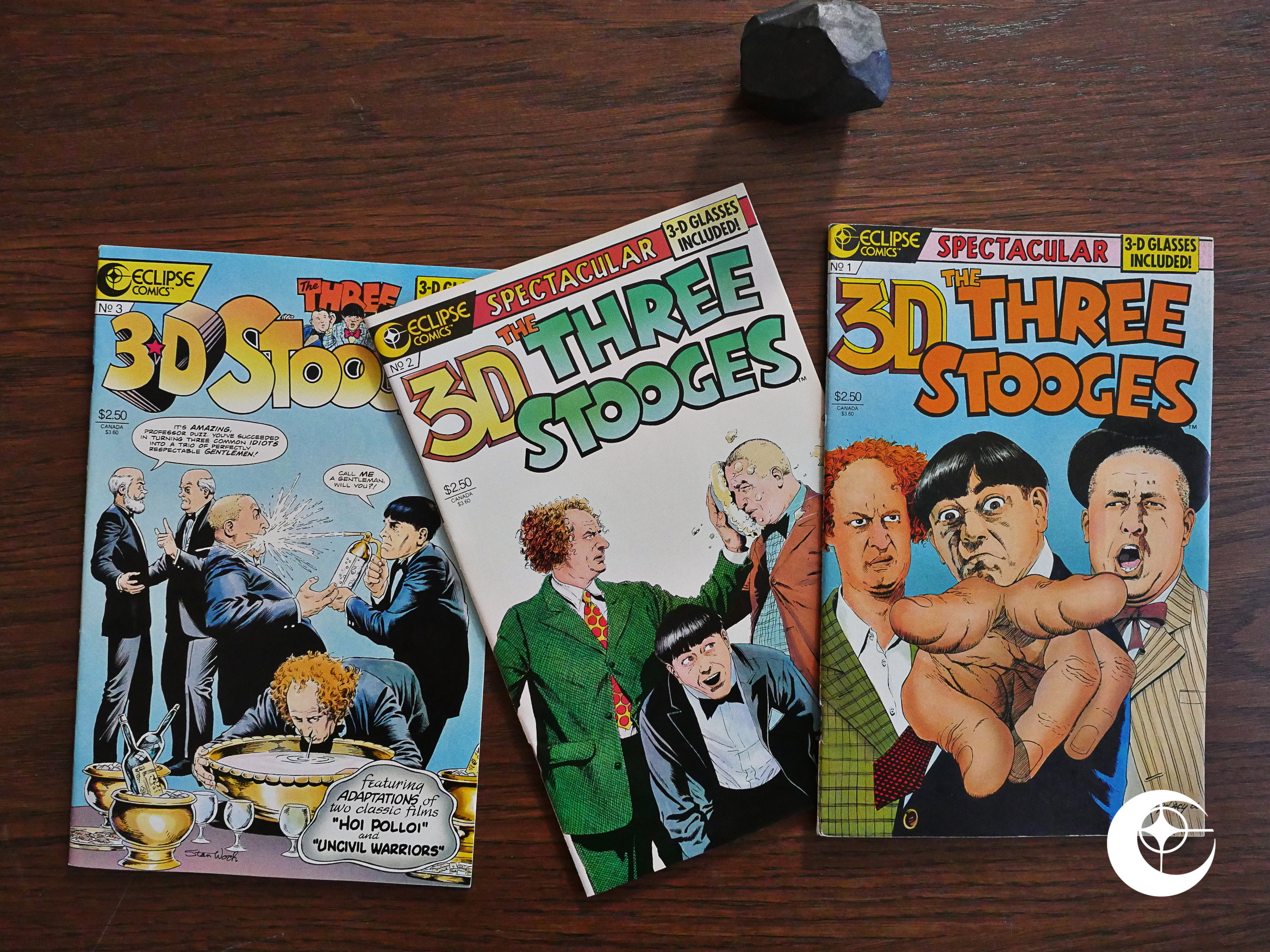

Zooniverse (1986) #1-6 Three-D Three Stooges (1986) #1-3

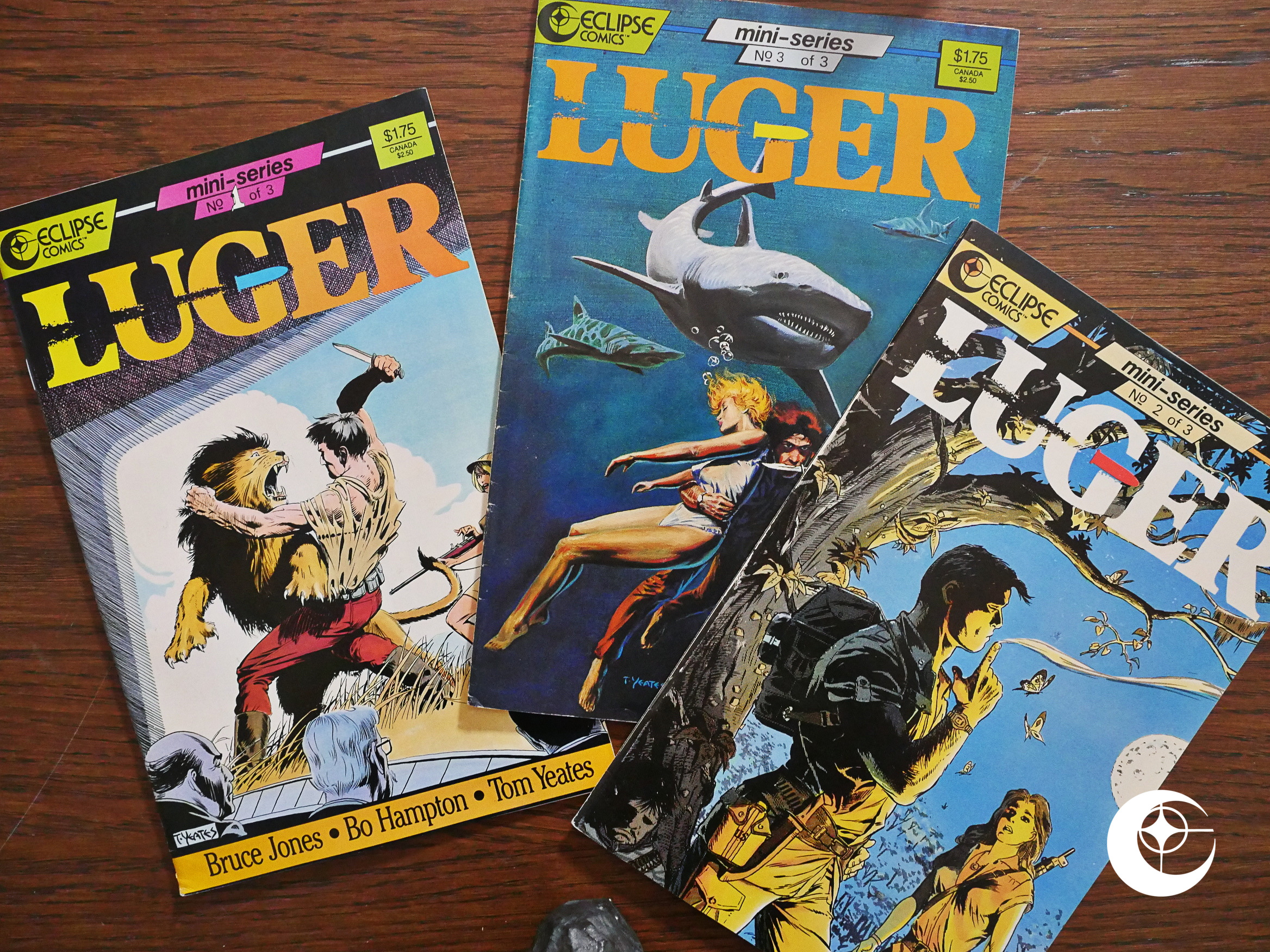

Three-D Three Stooges (1986) #1-3 Luger (1986) #1-3

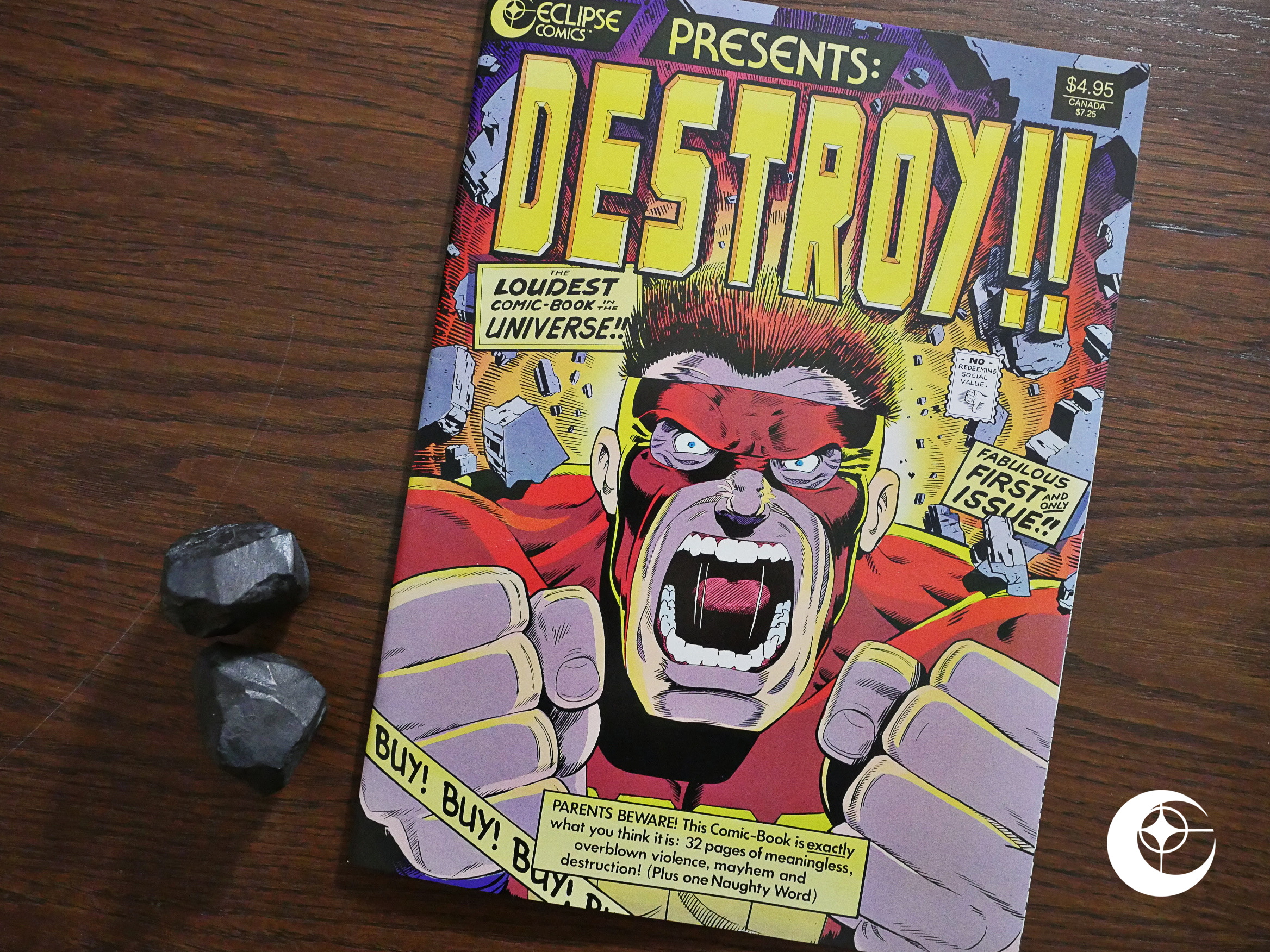

Luger (1986) #1-3 Destroy!! (1986) #1

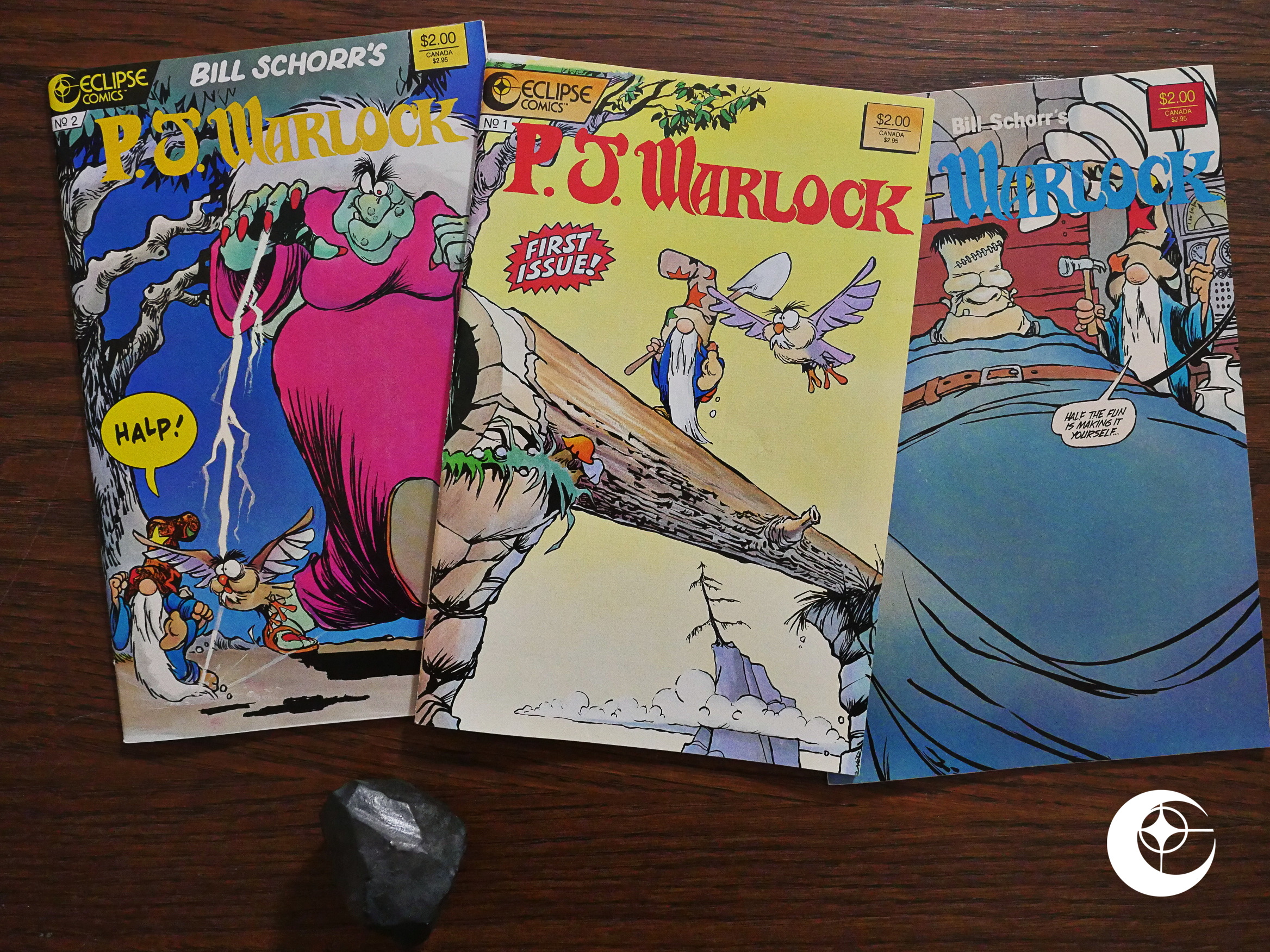

Destroy!! (1986) #1 P.J. Warlock (1986) #1-3

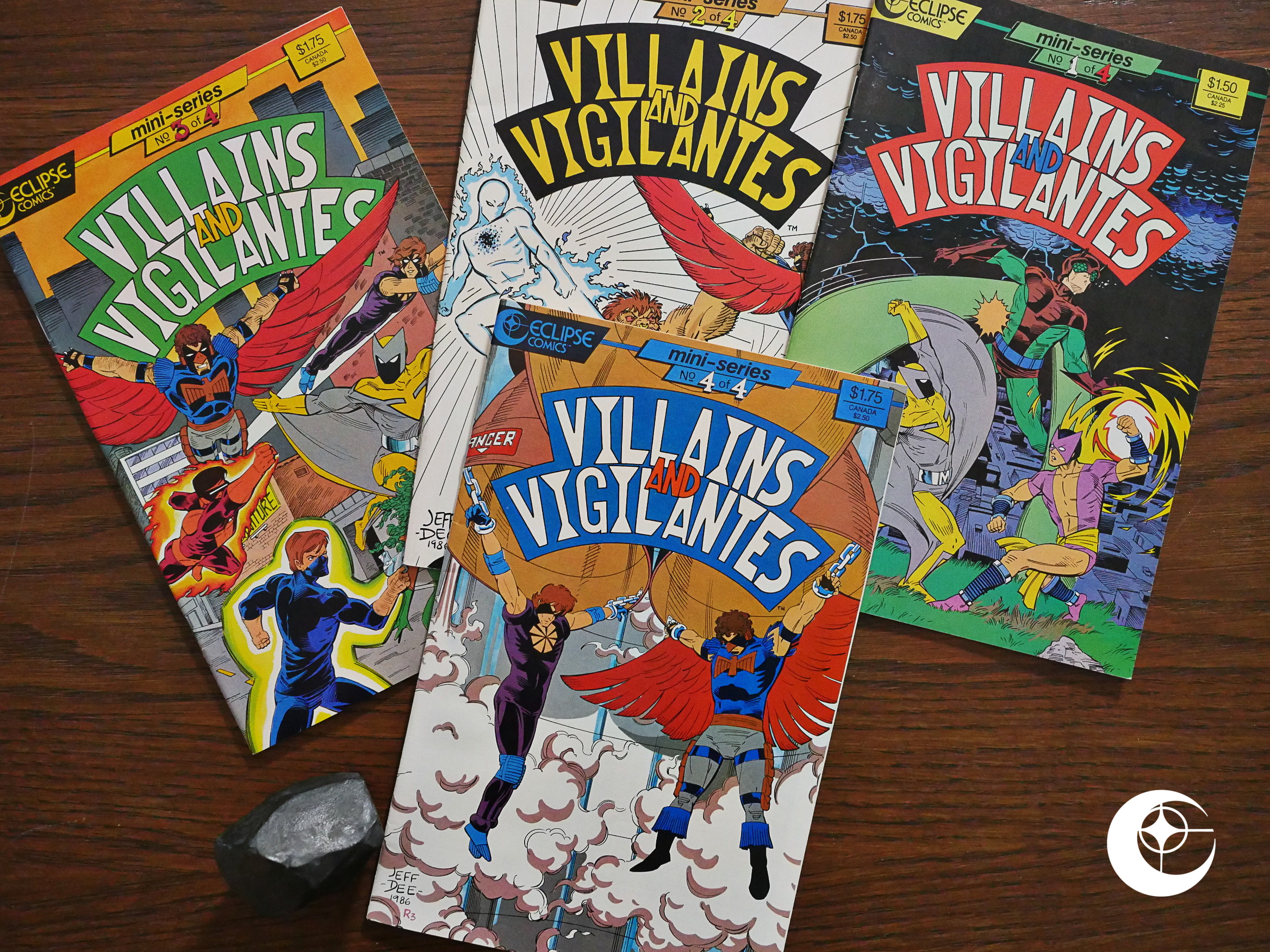

P.J. Warlock (1986) #1-3 Villains and Vigilantes (1986) #1-4

Villains and Vigilantes (1986) #1-4 The Dreamery (1986) #1-14

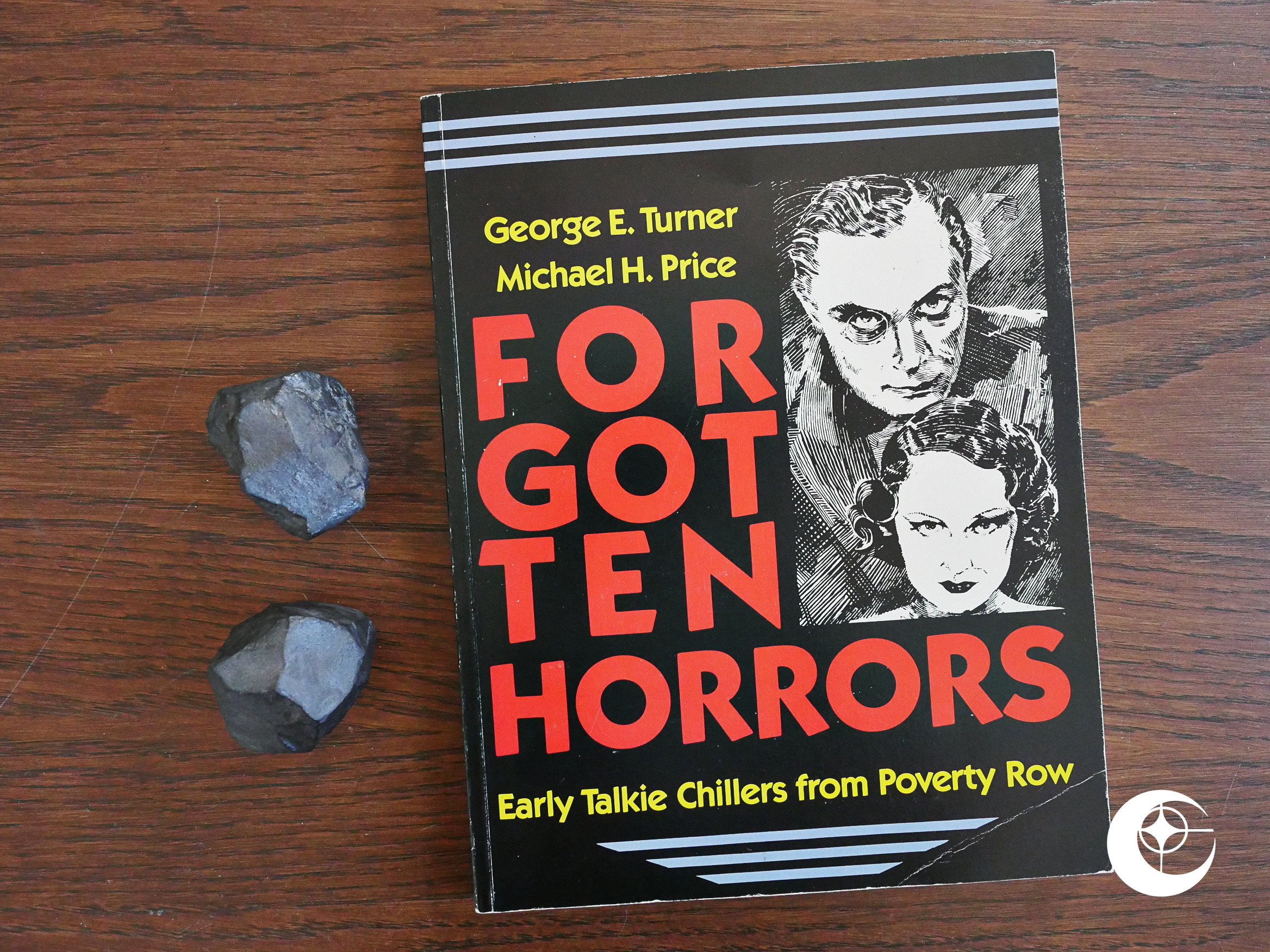

The Dreamery (1986) #1-14 Forgotten Horrors (1986) #1

Forgotten Horrors (1986) #1 Spaced (1986) #10-13

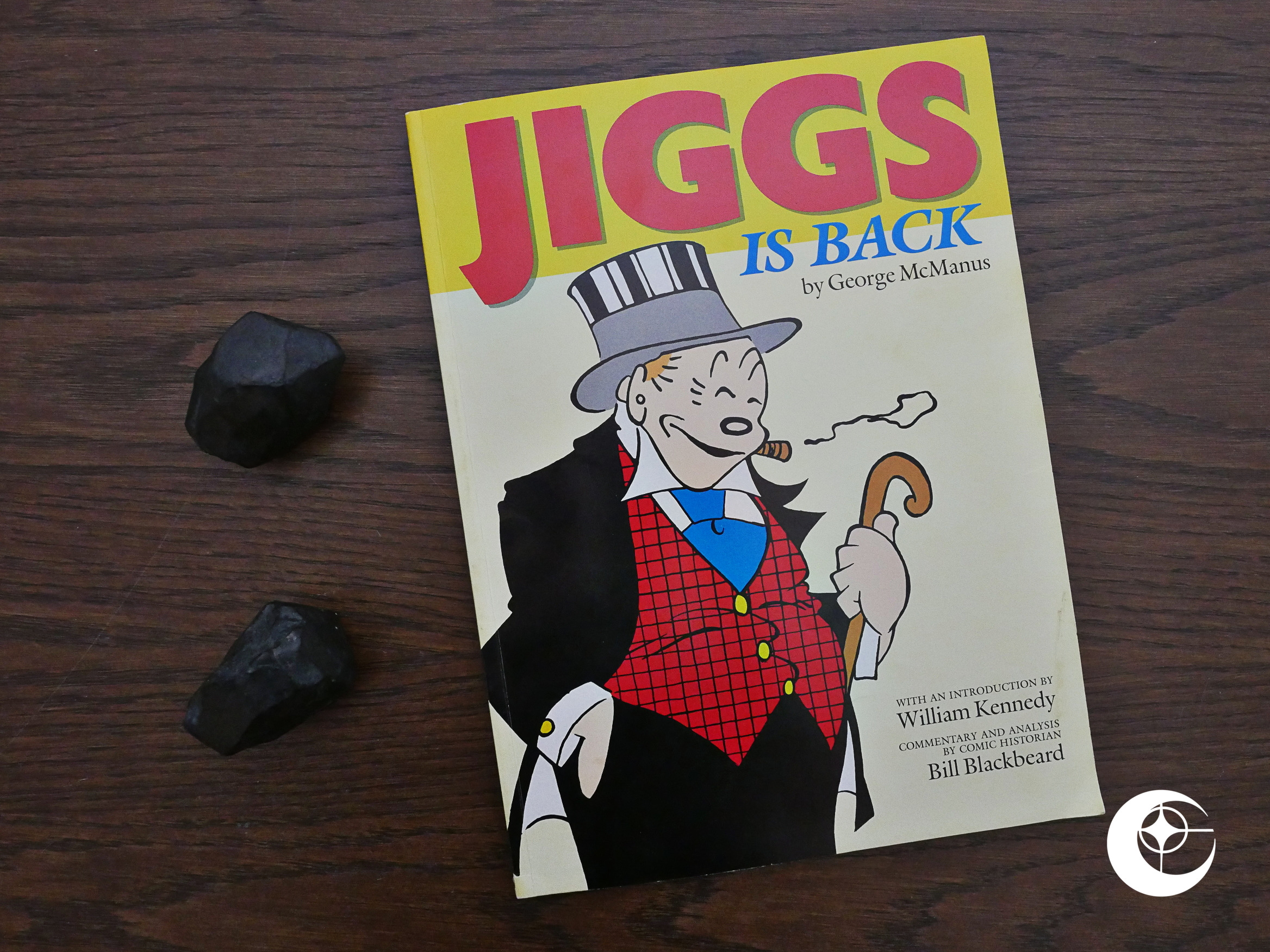

Spaced (1986) #10-13 Jiggs is Back (1986) #1

Jiggs is Back (1986) #1 Fusion (1987) #1-17

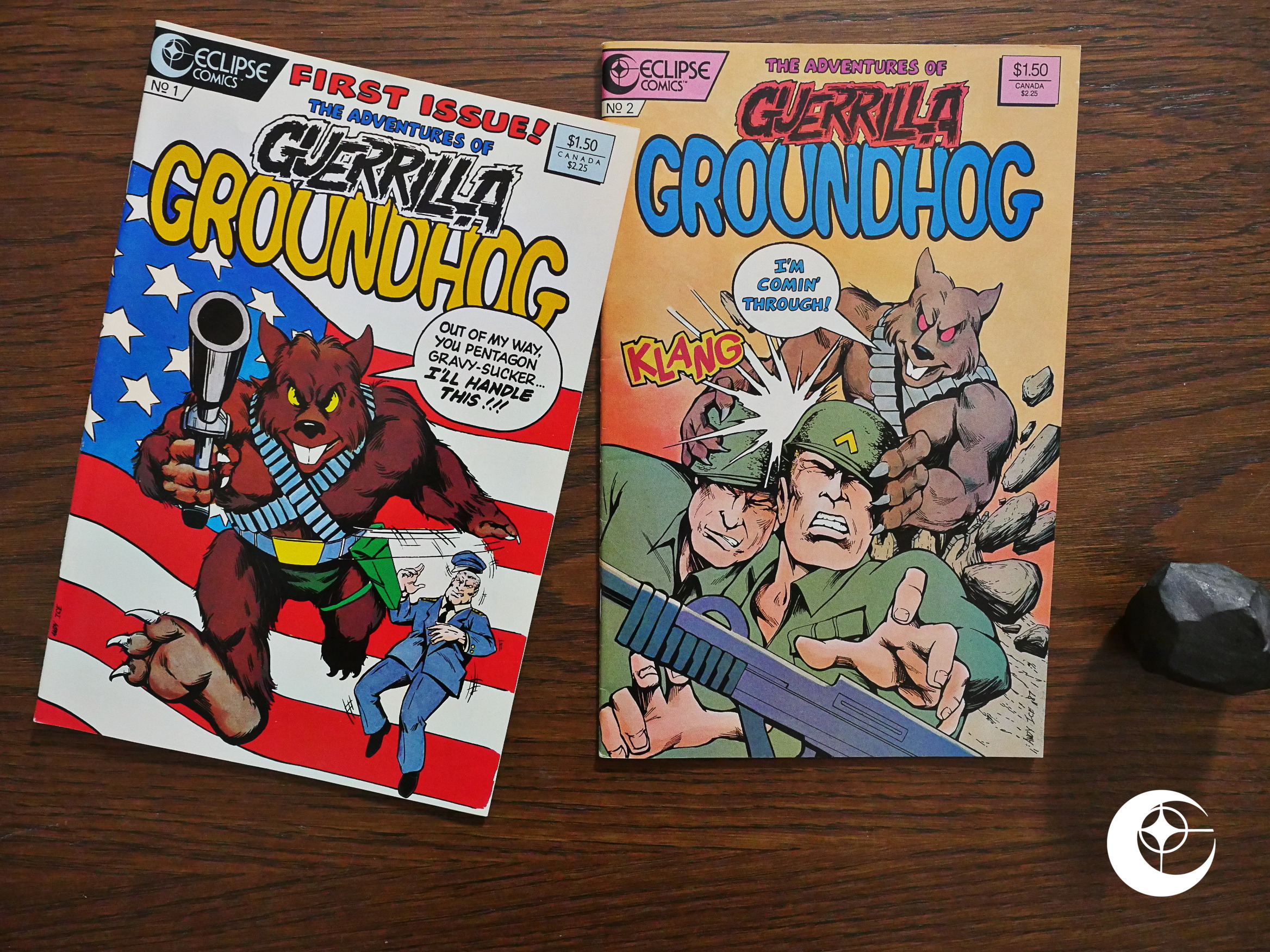

Fusion (1987) #1-17 Guerrilla Groundhog (1987) #1-2

Guerrilla Groundhog (1987) #1-2 Stig’s Inferno (1987) #6-7

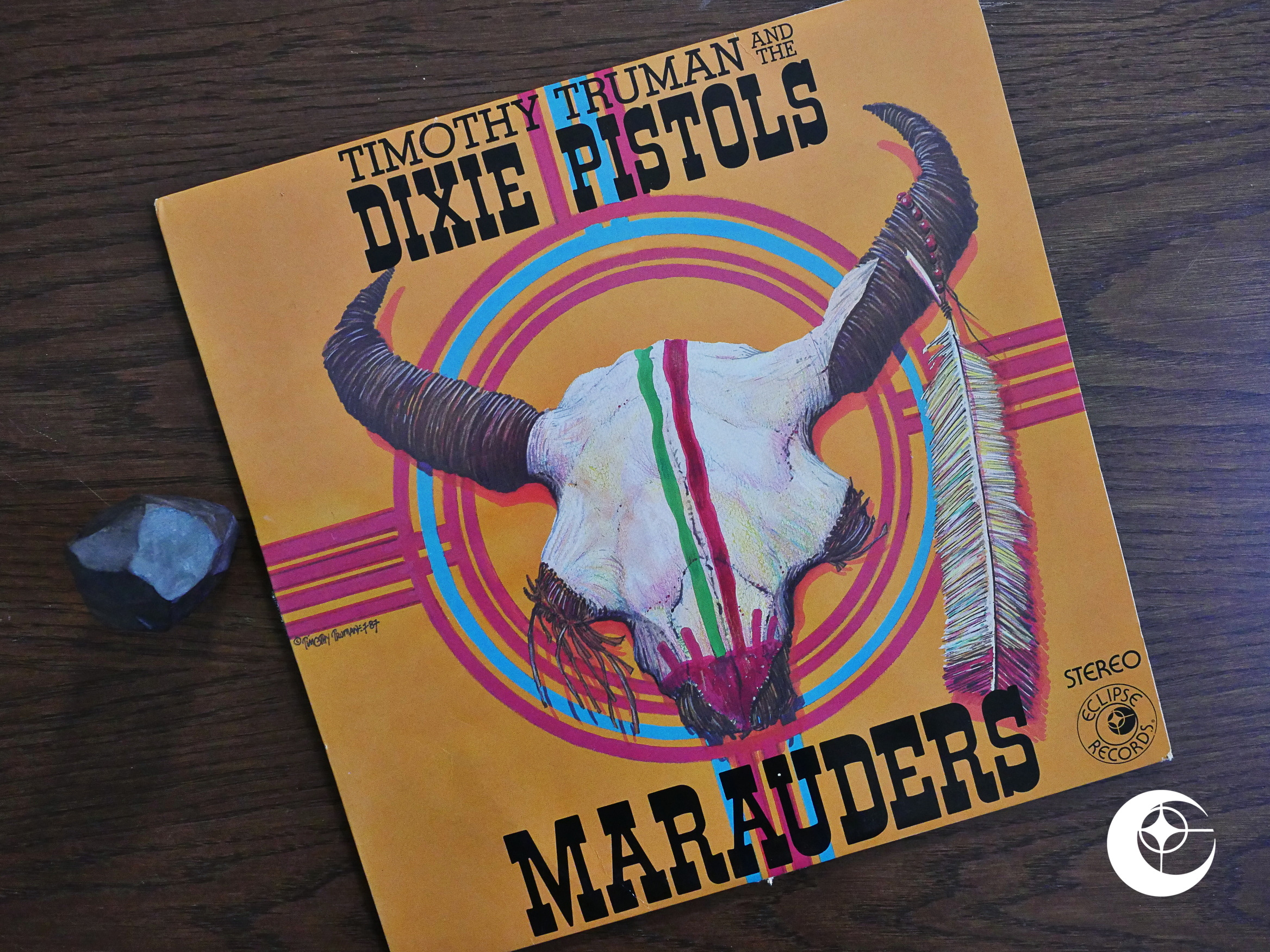

Stig’s Inferno (1987) #6-7 Marauders (1987)

Marauders (1987) Bullet Crow, Fowl of Fortune (1987) #1-2

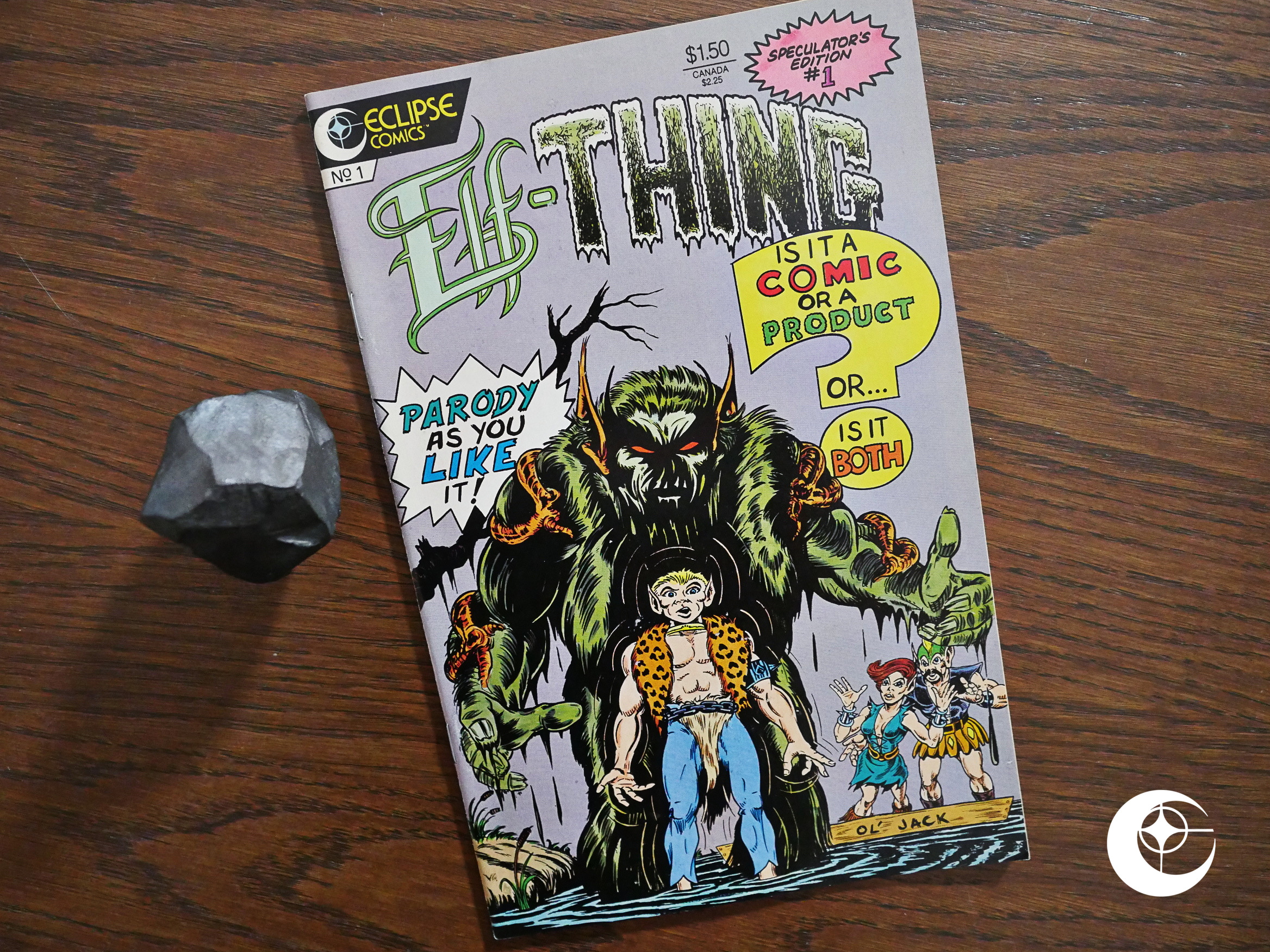

Bullet Crow, Fowl of Fortune (1987) #1-2 Elf-Thing (1987) #1

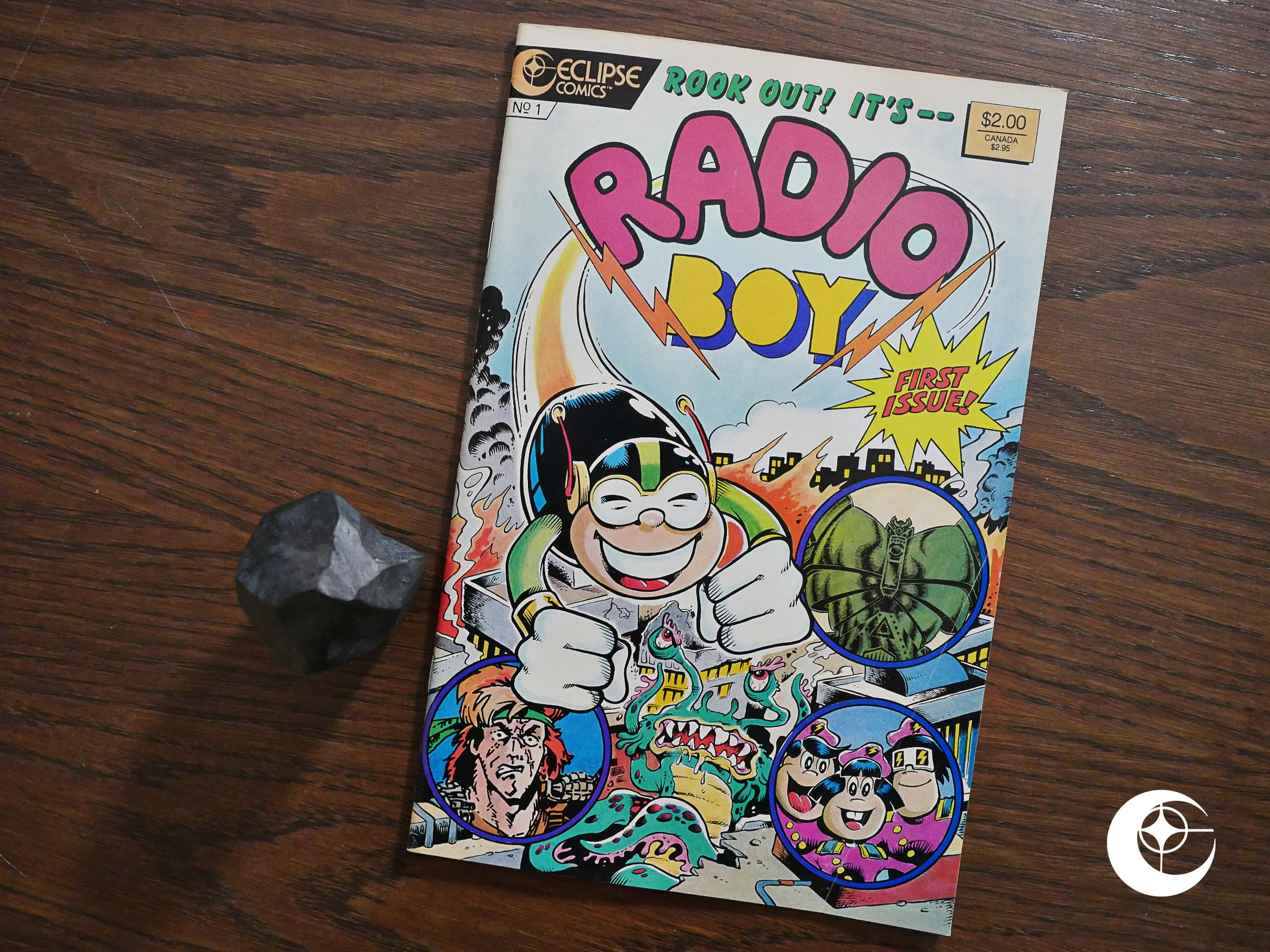

Elf-Thing (1987) #1 Radio Boy (1987) #1

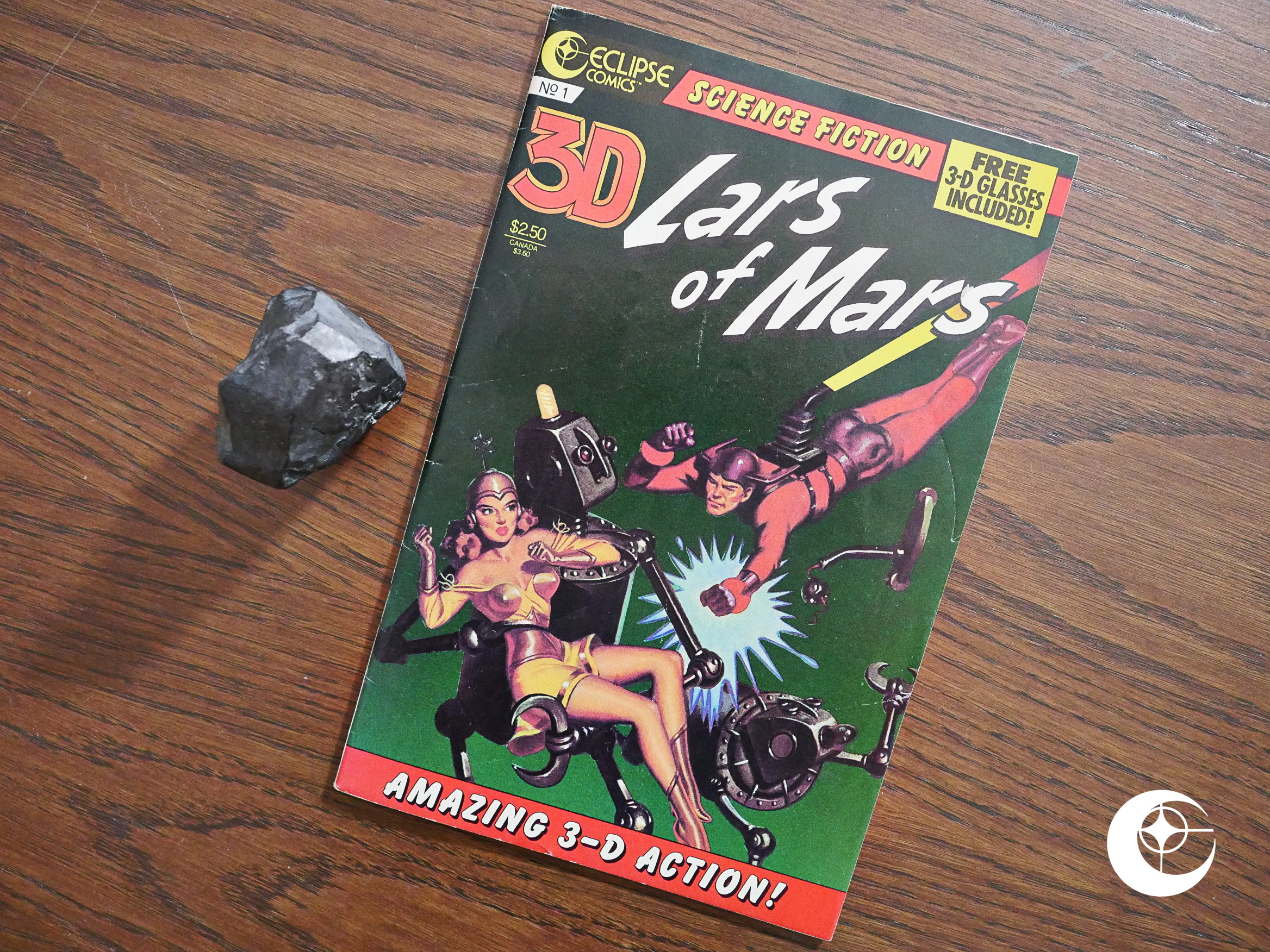

Radio Boy (1987) #1 Lars of Mars 3-D (1987) #1

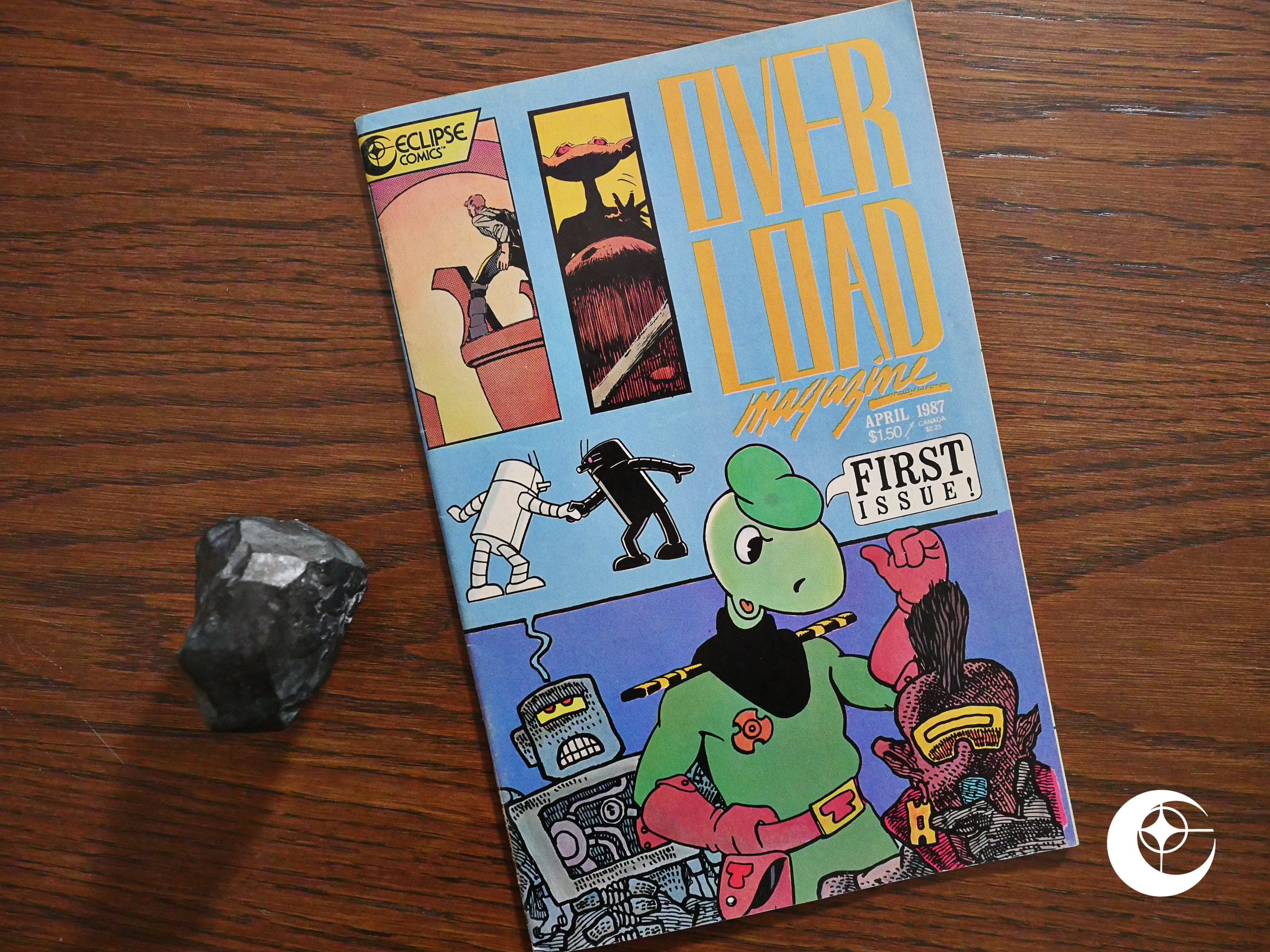

Lars of Mars 3-D (1987) #1 Overload Magazine (1987) #1

Overload Magazine (1987) #1 Area 88 (1987) #1-36

Area 88 (1987) #1-36 Kamui (1987) #1

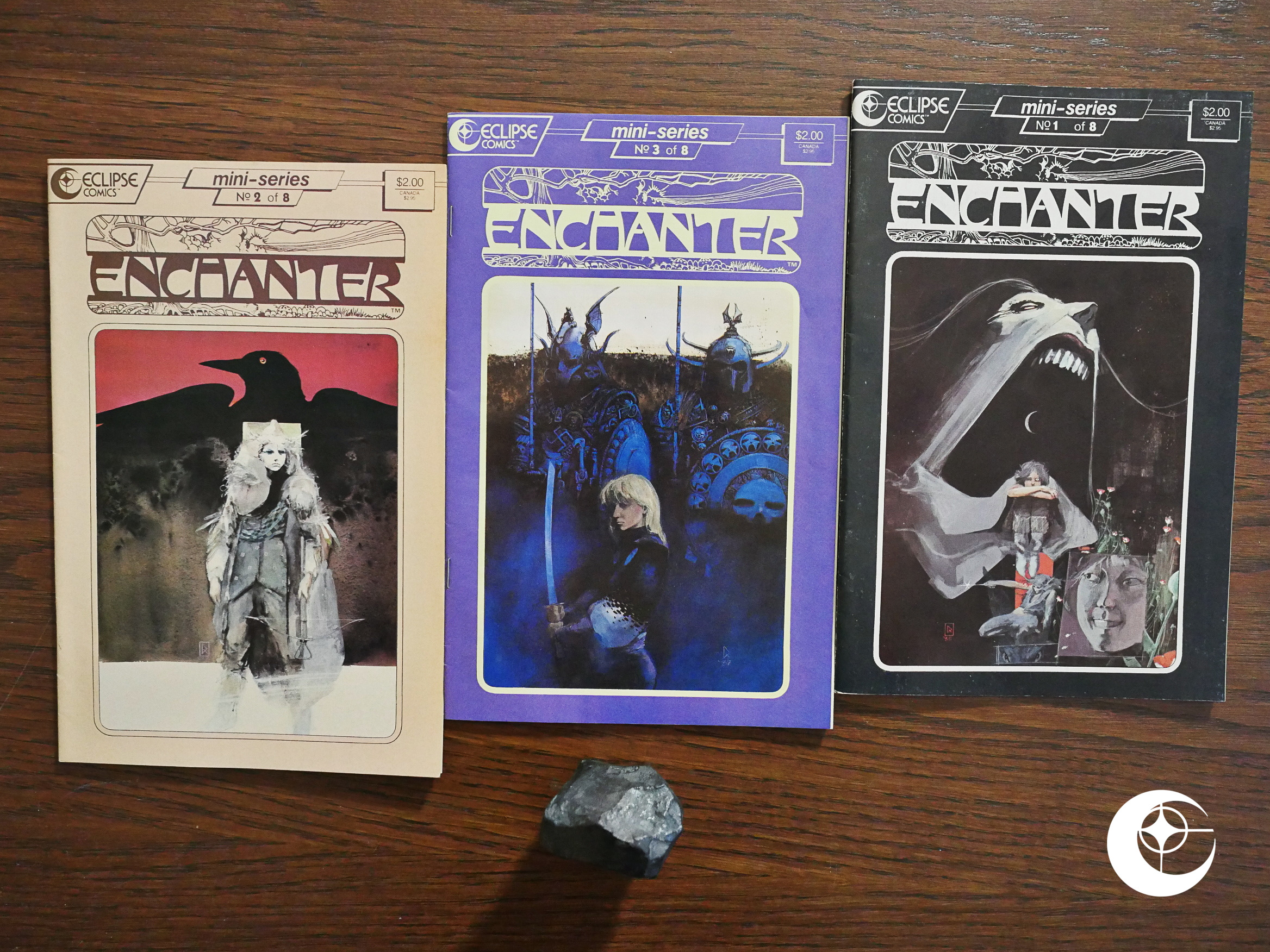

Kamui (1987) #1 Enchanter (1987) #1-3

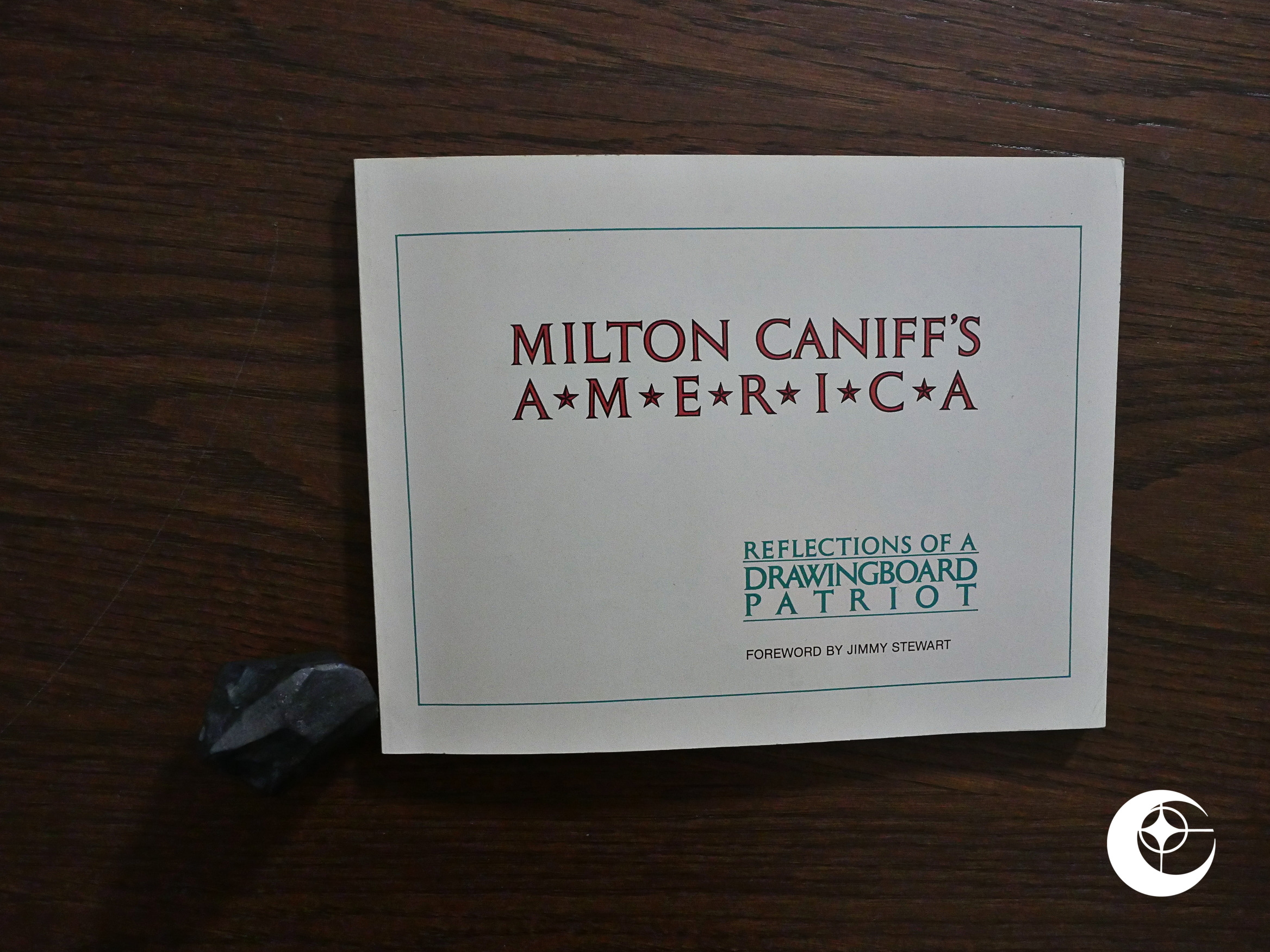

Enchanter (1987) #1-3 Milton Caniff’s America (1987)

Milton Caniff’s America (1987) Lost Planet (1987) #1-6

Lost Planet (1987) #1-6 Mai, the Psychic Girl (1987) #1-28

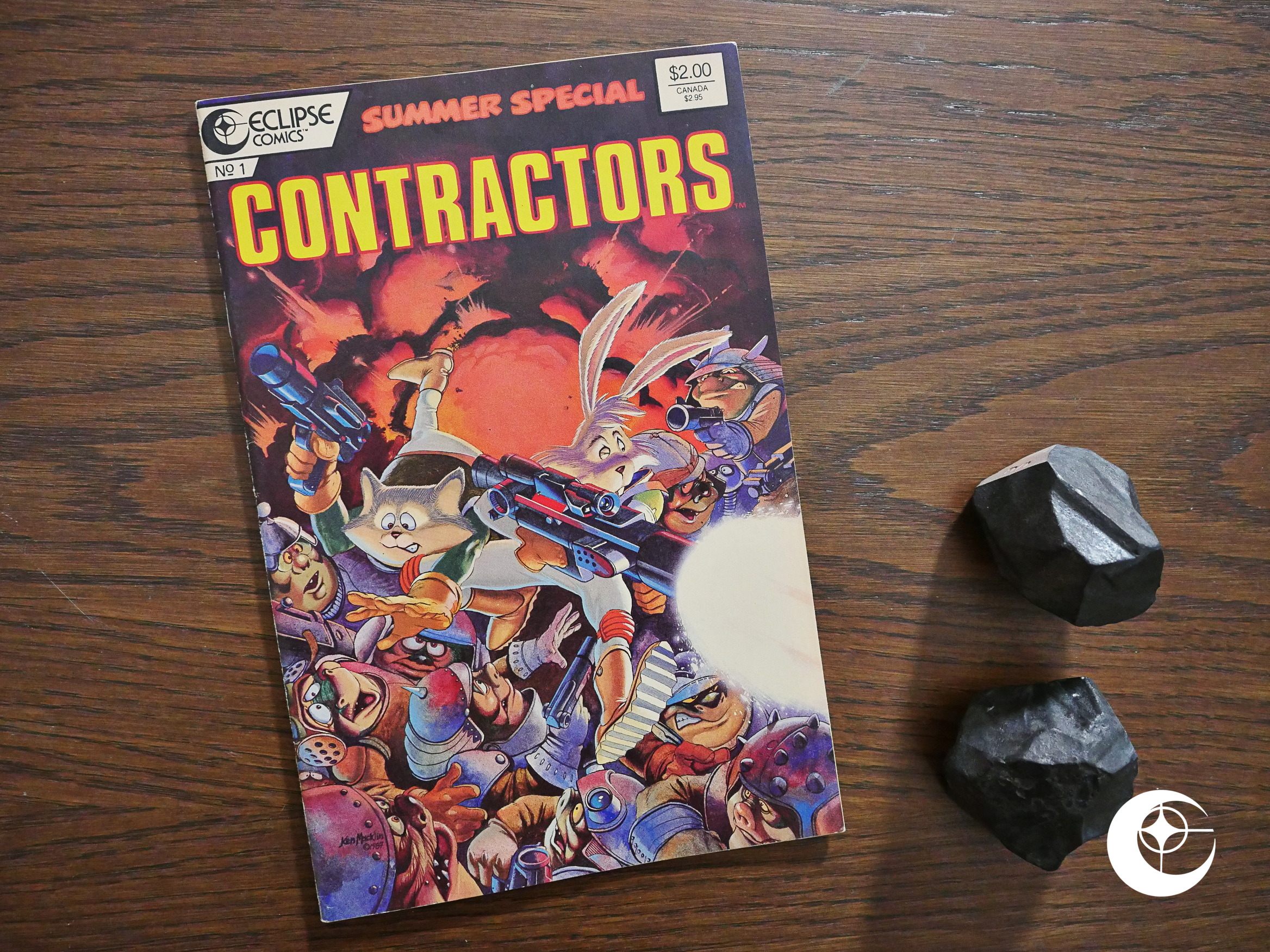

Mai, the Psychic Girl (1987) #1-28 Contractors (1987) #1

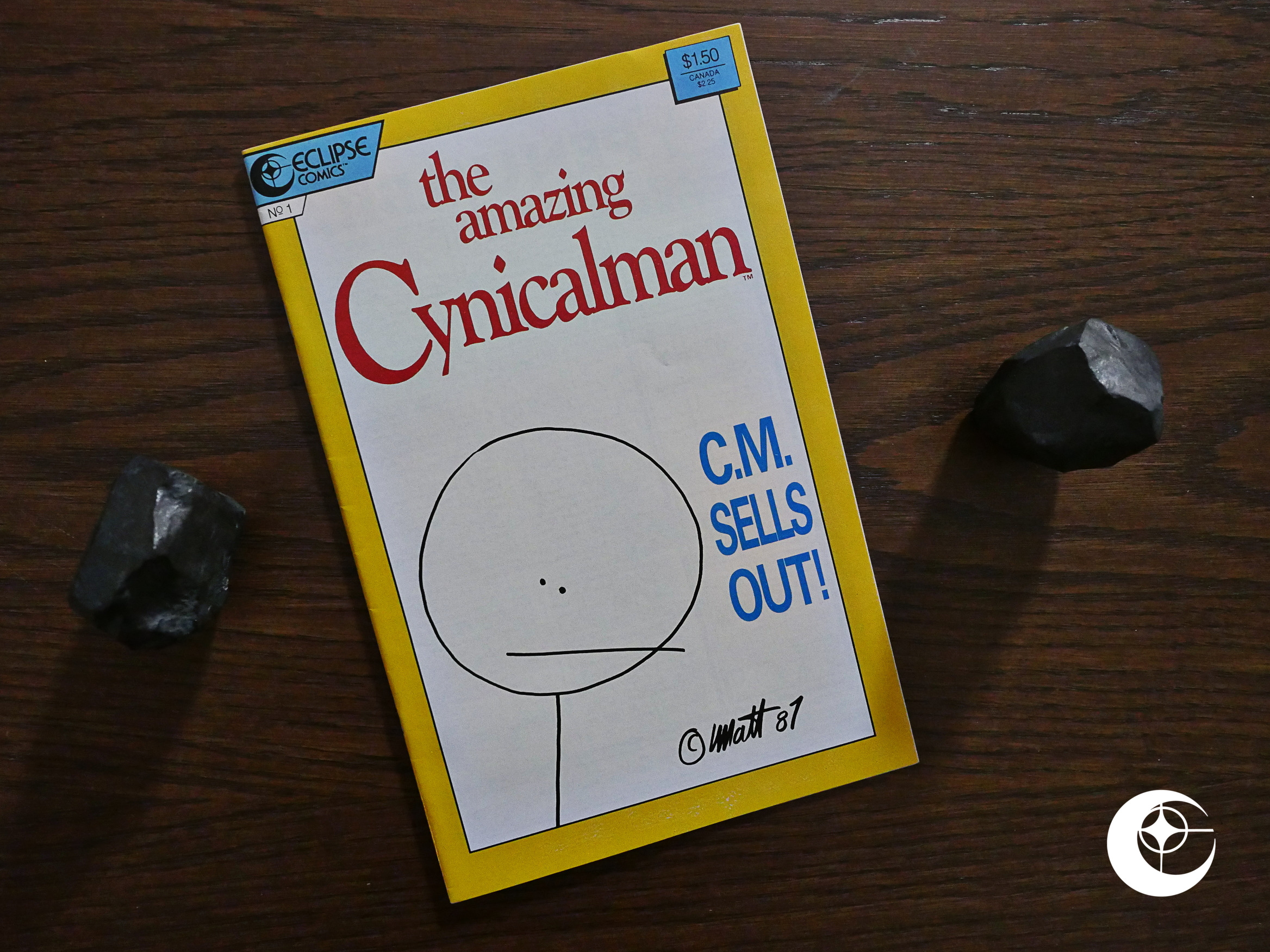

Contractors (1987) #1 The Amazing Cynicalman (1987) #1

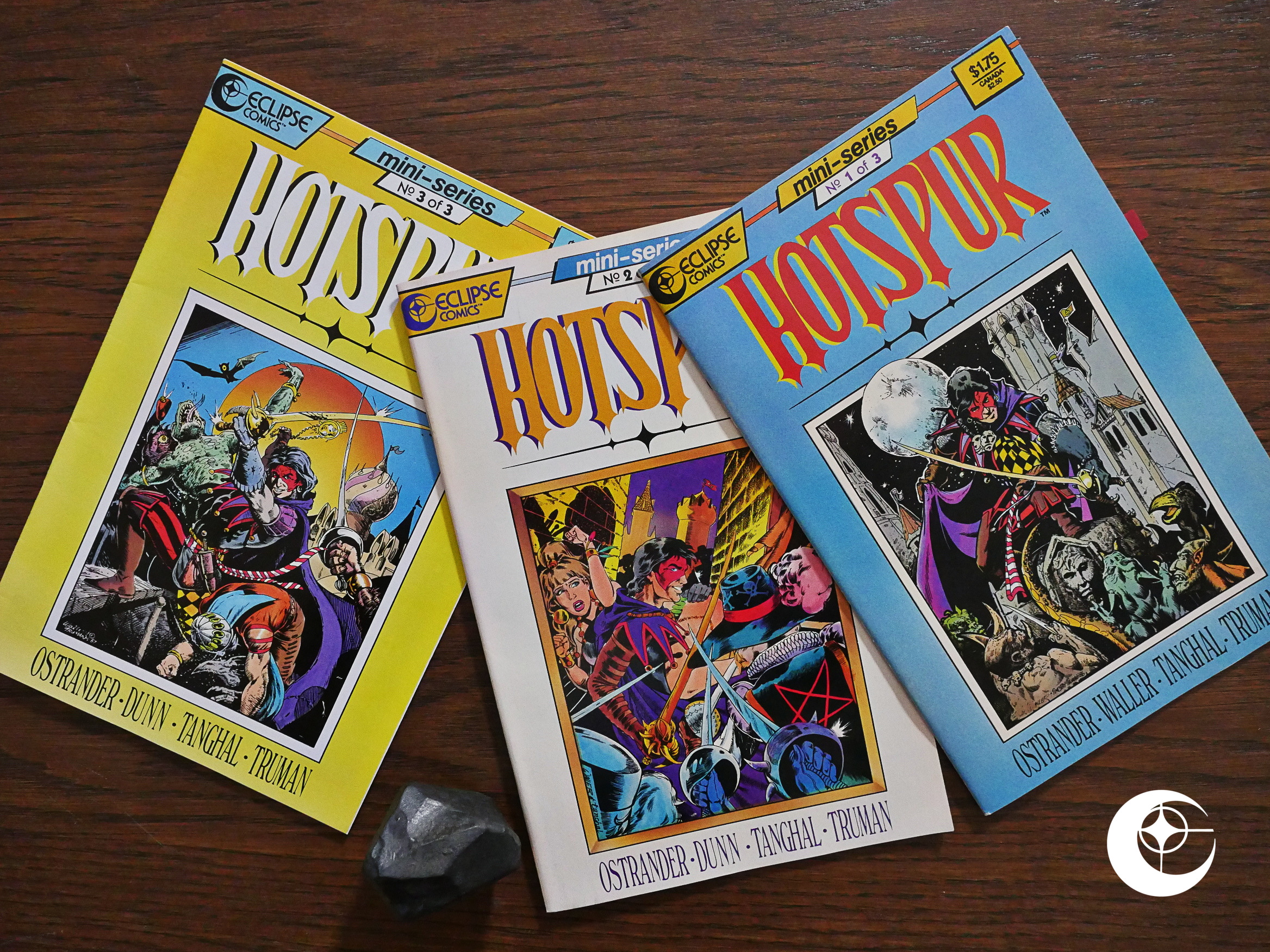

The Amazing Cynicalman (1987) #1 Hotspur (1987) #1-3

Hotspur (1987) #1-3 The Liberty Project (1987) #1-8

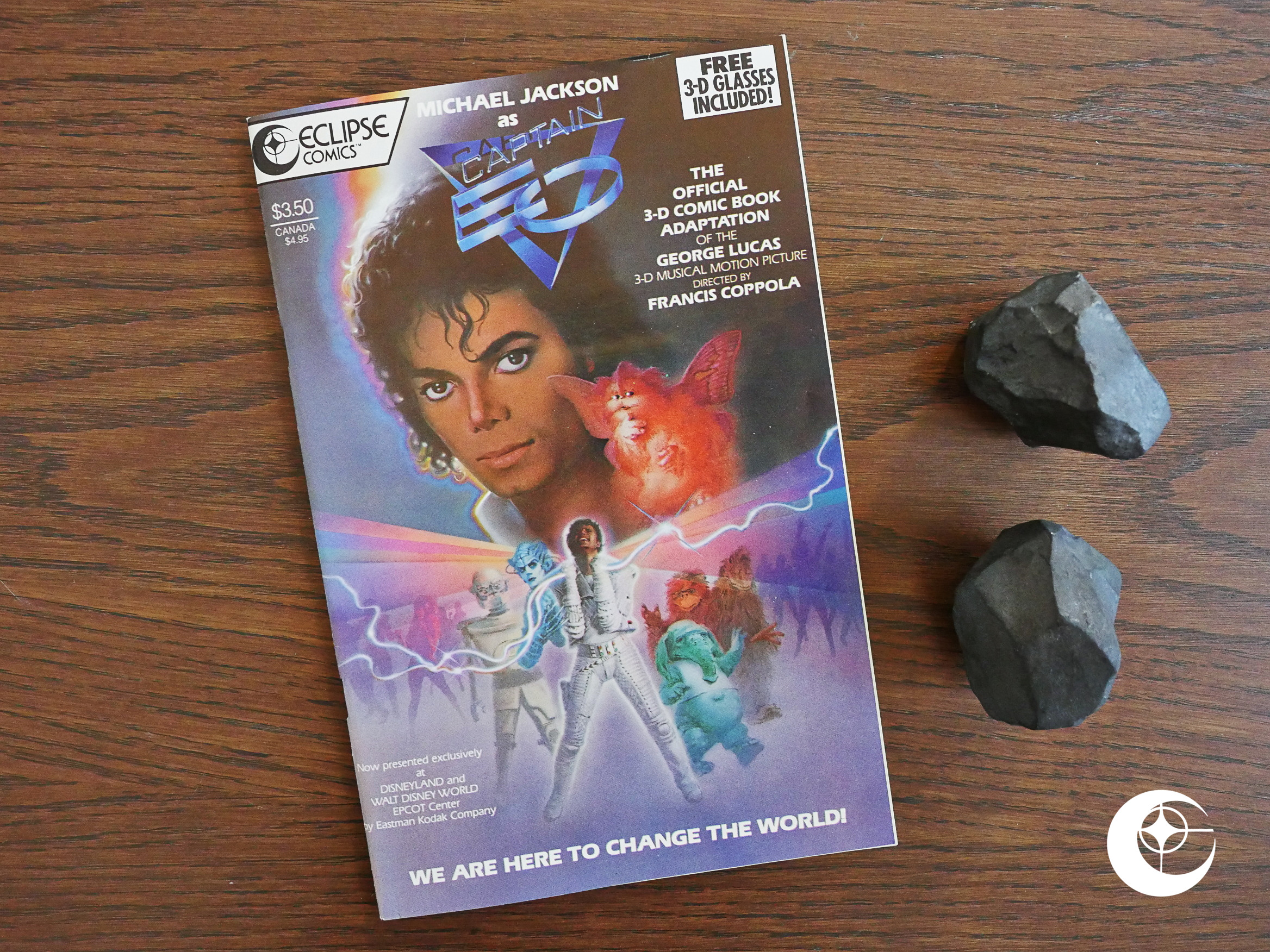

The Liberty Project (1987) #1-8 Captain EO 3-D (1987) #1

Captain EO 3-D (1987) #1 The Prowler (1987) #1-4

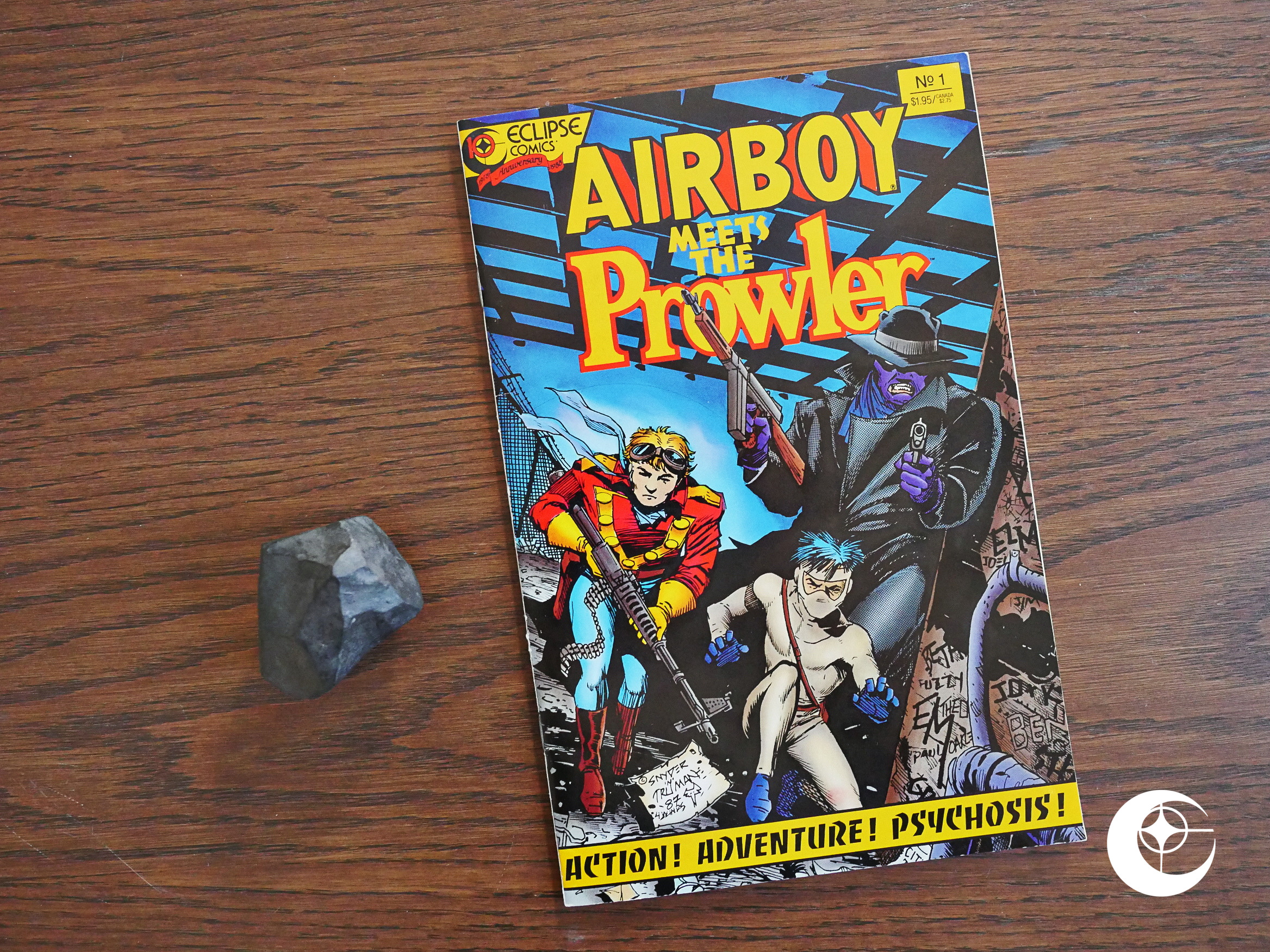

The Prowler (1987) #1-4 Airboy Meets the Prowler (1987) #1

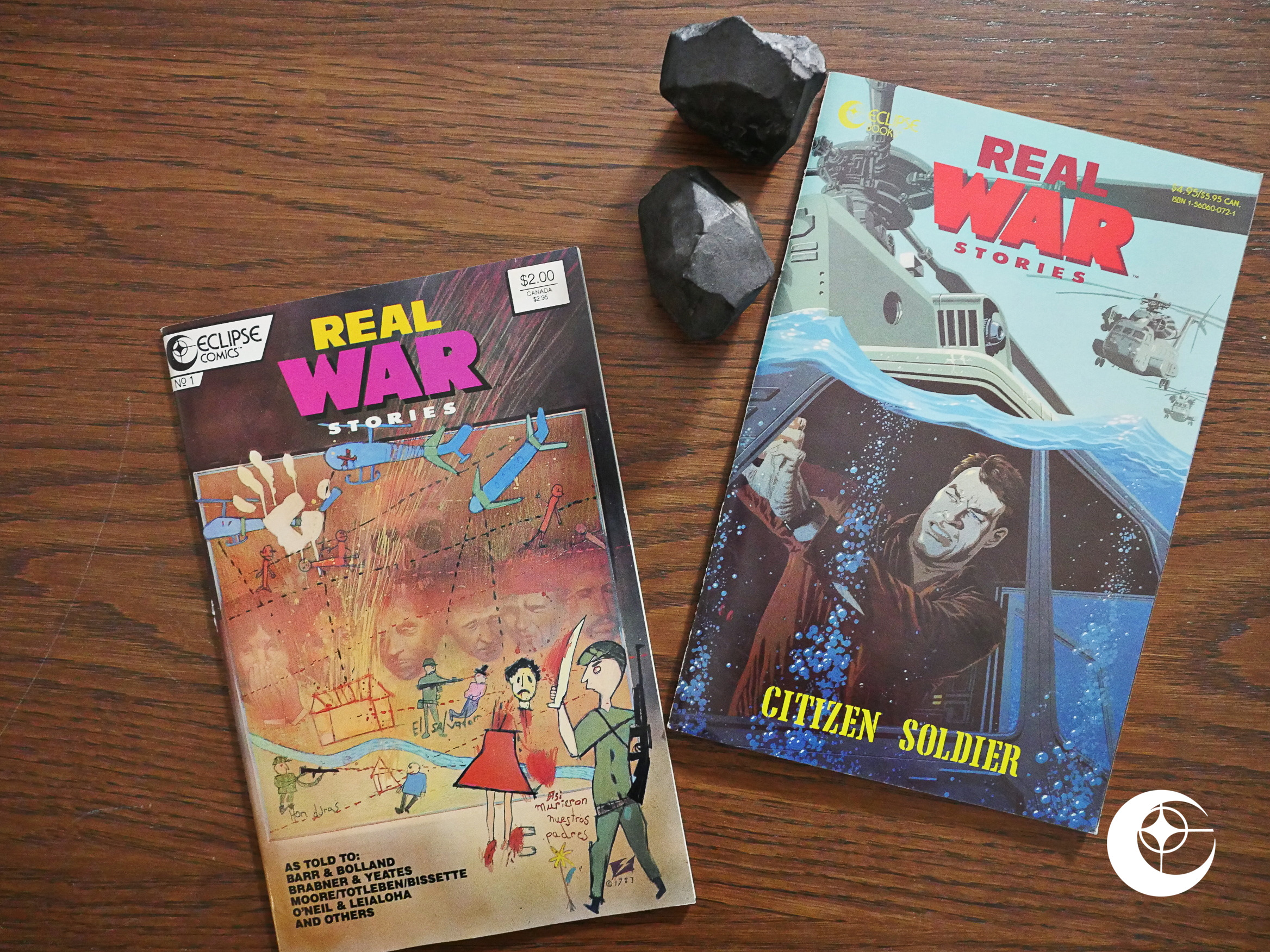

Airboy Meets the Prowler (1987) #1 Real War Stories (1987) #1-2

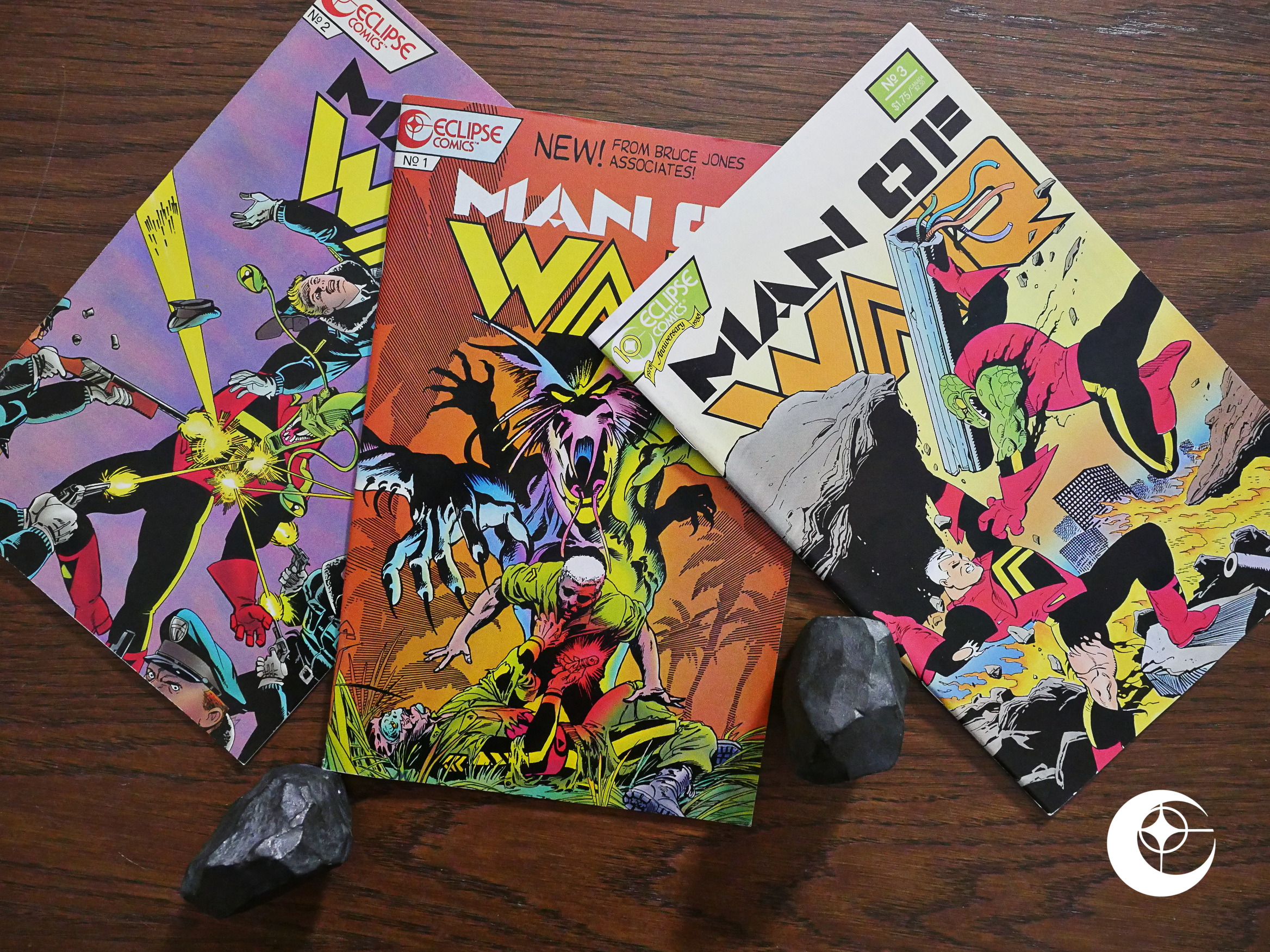

Real War Stories (1987) #1-2 Man of War (1987) #1-3

Man of War (1987) #1-3 Strike! (1987) #1-6

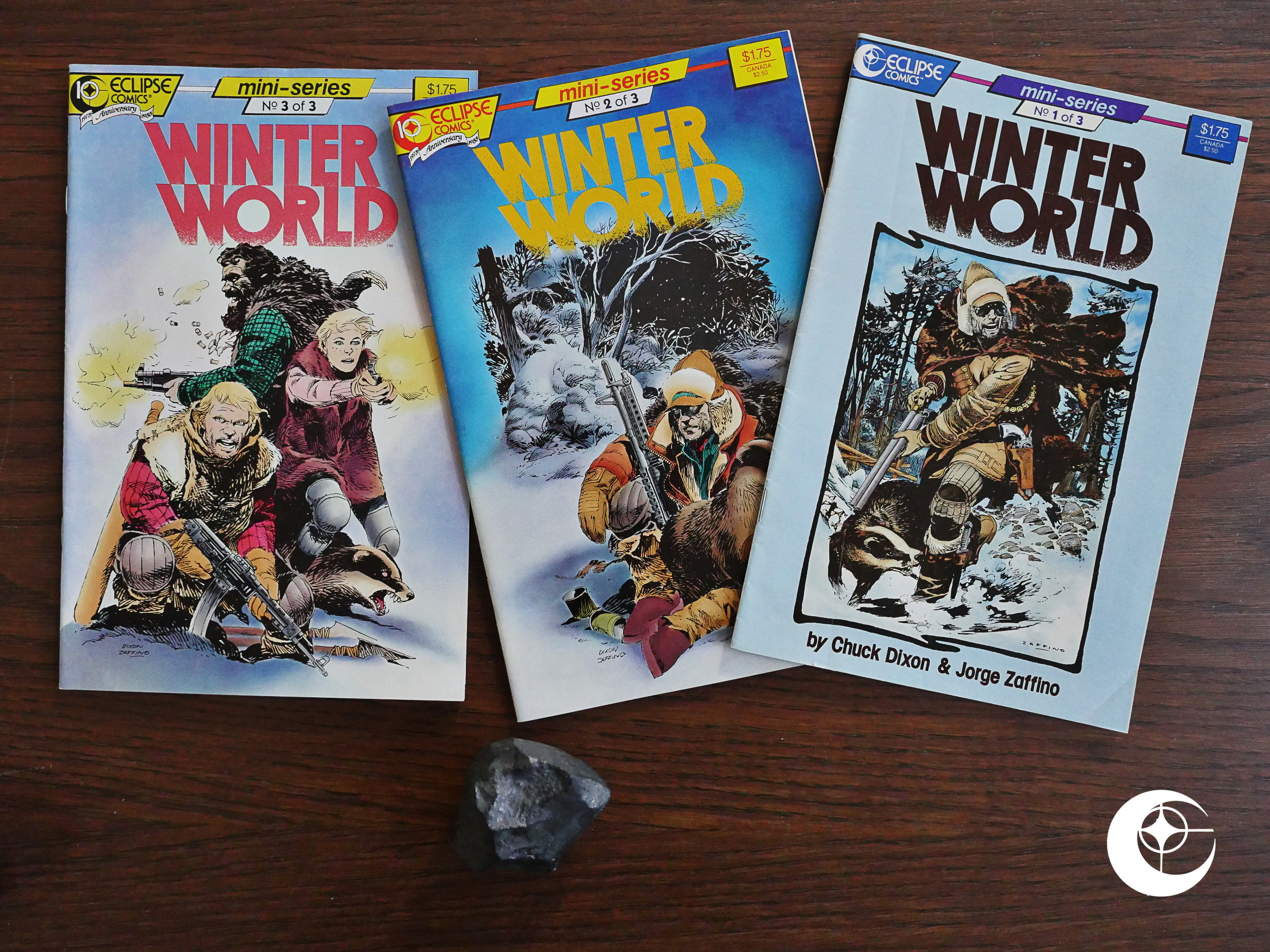

Strike! (1987) #1-6 Winter World (1987) #1-3

Winter World (1987) #1-3 Halloween Horror (1987) #1

Halloween Horror (1987) #1 Swords of Texas (1987) #1-4

Swords of Texas (1987) #1-4 New America (1987) #1-4

New America (1987) #1-4 Walt Kelly’s Christmas Classics (1987) #1

Walt Kelly’s Christmas Classics (1987) #1 Xenon (1987) #1-23

Xenon (1987) #1-23 Axa (1987) #1-2

Axa (1987) #1-2 Directory to a Non-Existent Universe (1987) #1

Directory to a Non-Existent Universe (1987) #1 Target: Airboy (1988) #1

Target: Airboy (1988) #1 Airboy versus the Airmaidens (1988) #1

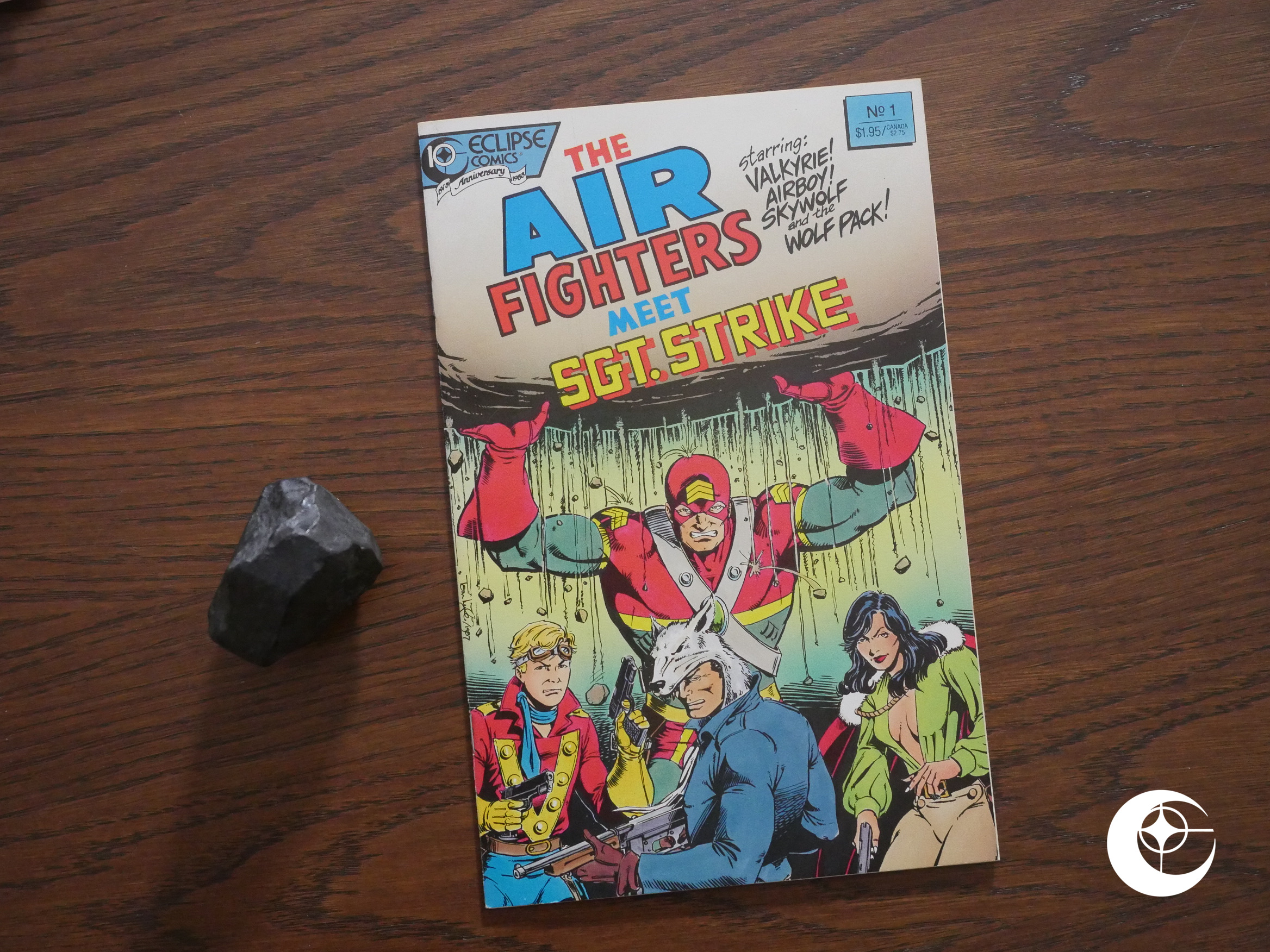

Airboy versus the Airmaidens (1988) #1 The Airfighters Meet Sgt. Strike Special (1988) #1

The Airfighters Meet Sgt. Strike Special (1988) #1 Total Eclipse: The Seraphim Objective (1988) #1

Total Eclipse: The Seraphim Objective (1988) #1 The Revenge of the Prowler (1988) #1-4

The Revenge of the Prowler (1988) #1-4 The Prowler in White Zombie (1988) #1

The Prowler in White Zombie (1988) #1 Hand of Fate (1988) #1-3

Hand of Fate (1988) #1-3 Weird Romance (1988) #1

Weird Romance (1988) #1 R.O.B.O.T. Battalion 2050 (1988) #1

R.O.B.O.T. Battalion 2050 (1988) #1 Scout: War Shaman (1988) #1-16

Scout: War Shaman (1988) #1-16 Phaze (1988) #1-2

Phaze (1988) #1-2 Total Eclipse (1988) #1-5

Total Eclipse (1988) #1-5 Merchants of Death (1988) #1-4

Merchants of Death (1988) #1-4 New York: Year Zero (1988) #1-4

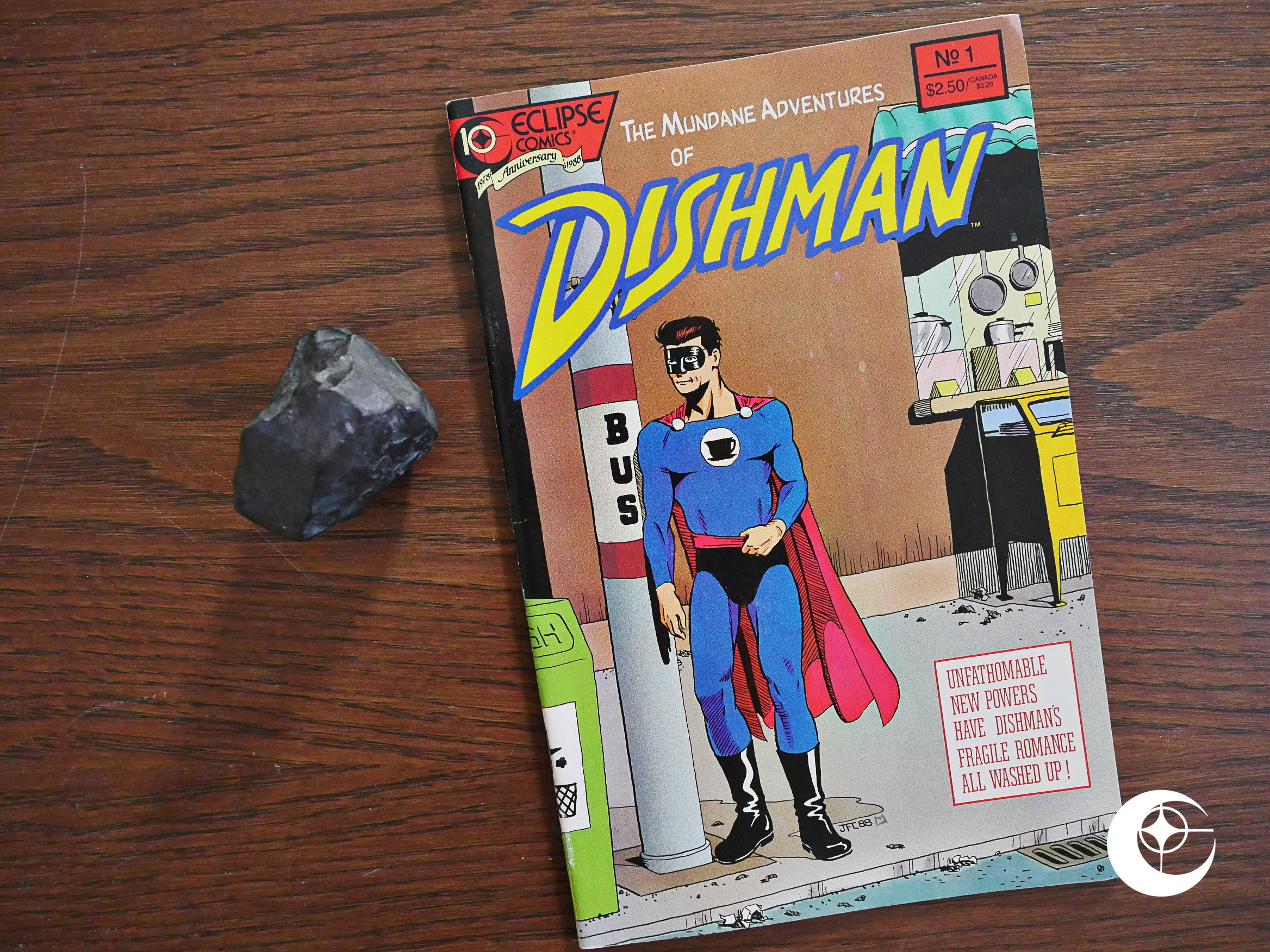

New York: Year Zero (1988) #1-4 Dishman (1988) #1

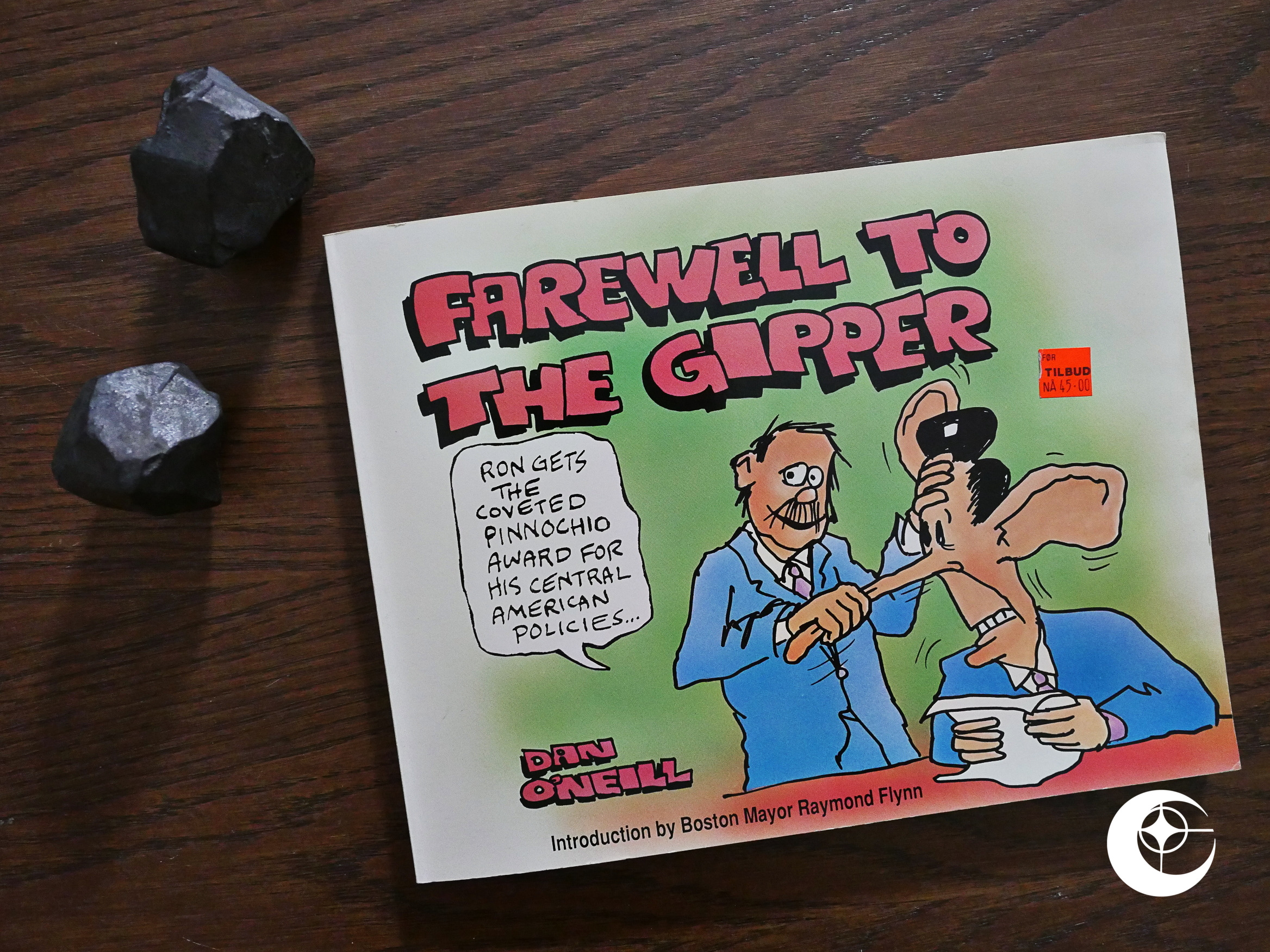

Dishman (1988) #1 Farewell to the Gipper (1988) #1

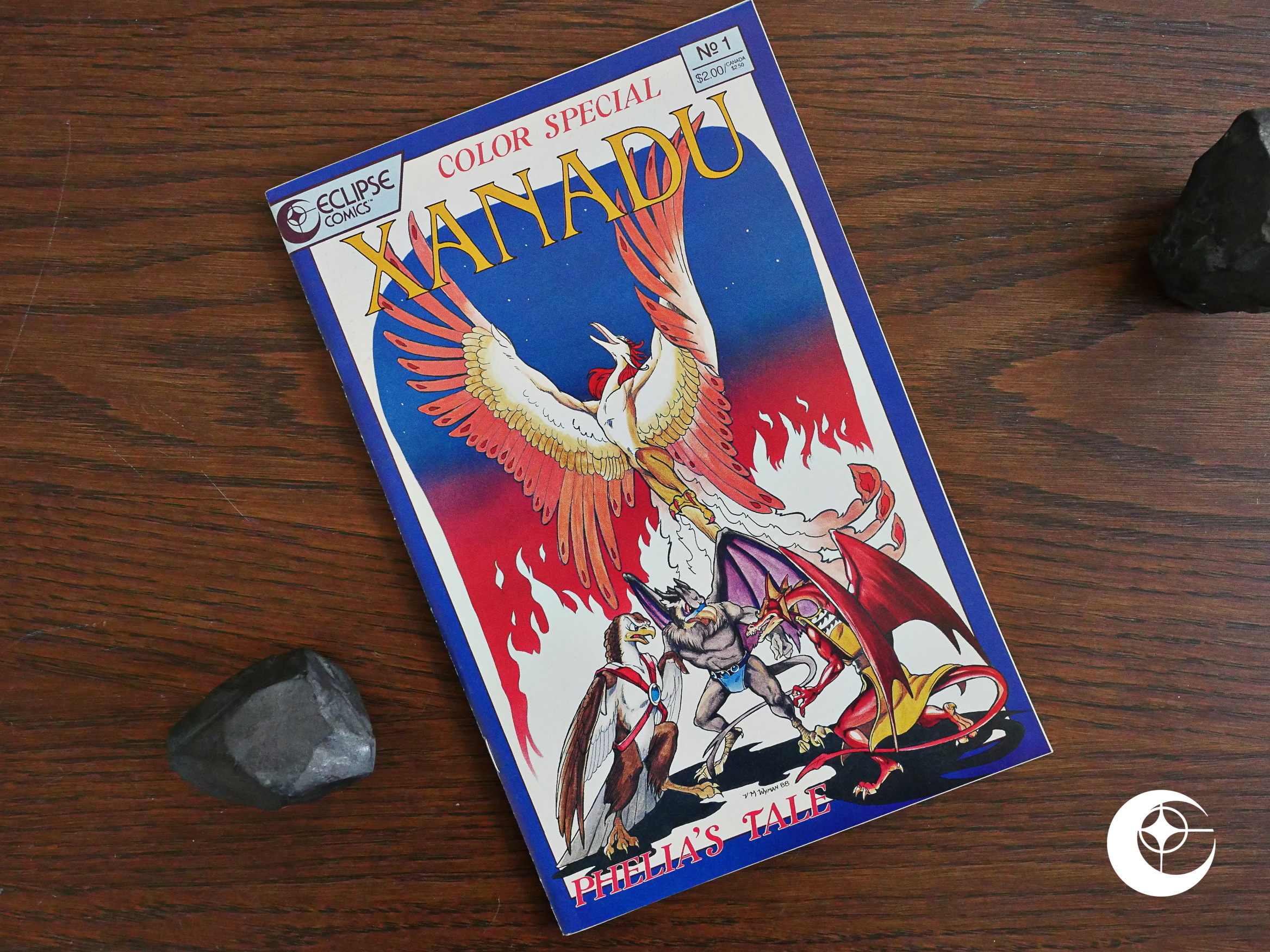

Farewell to the Gipper (1988) #1 Xanadu Color Special (1988) #1

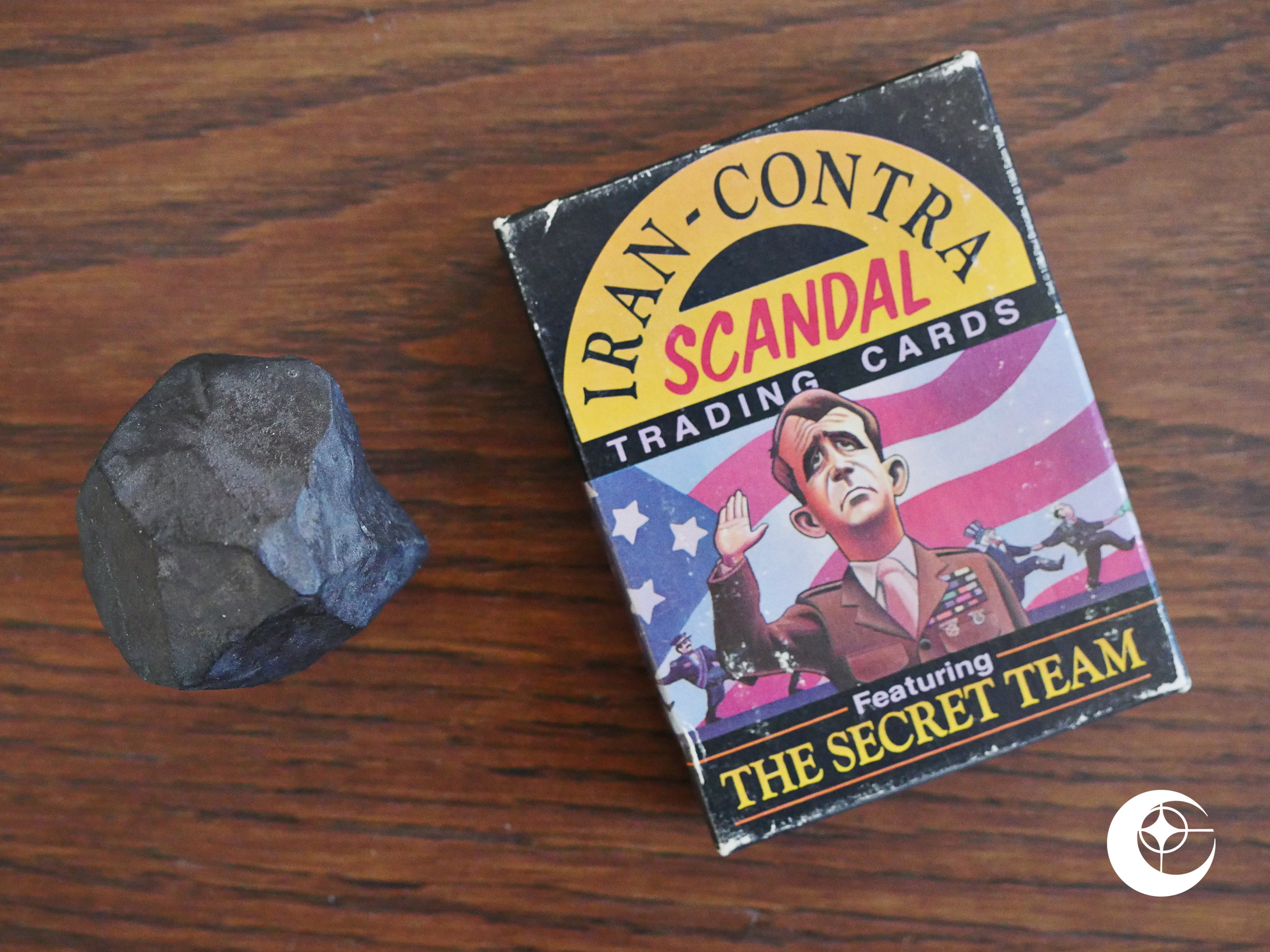

Xanadu Color Special (1988) #1 The Iran-Contra Scandal Trading Cards (1988)

The Iran-Contra Scandal Trading Cards (1988) Tips from Top Cartoonists (1988)

Tips from Top Cartoonists (1988) Lil’ Grusome and the Nutshell Gang (1988)

Lil’ Grusome and the Nutshell Gang (1988) Weasel Patrol (1989) #1

Weasel Patrol (1989) #1 Swordsmen and Saurians (1989)

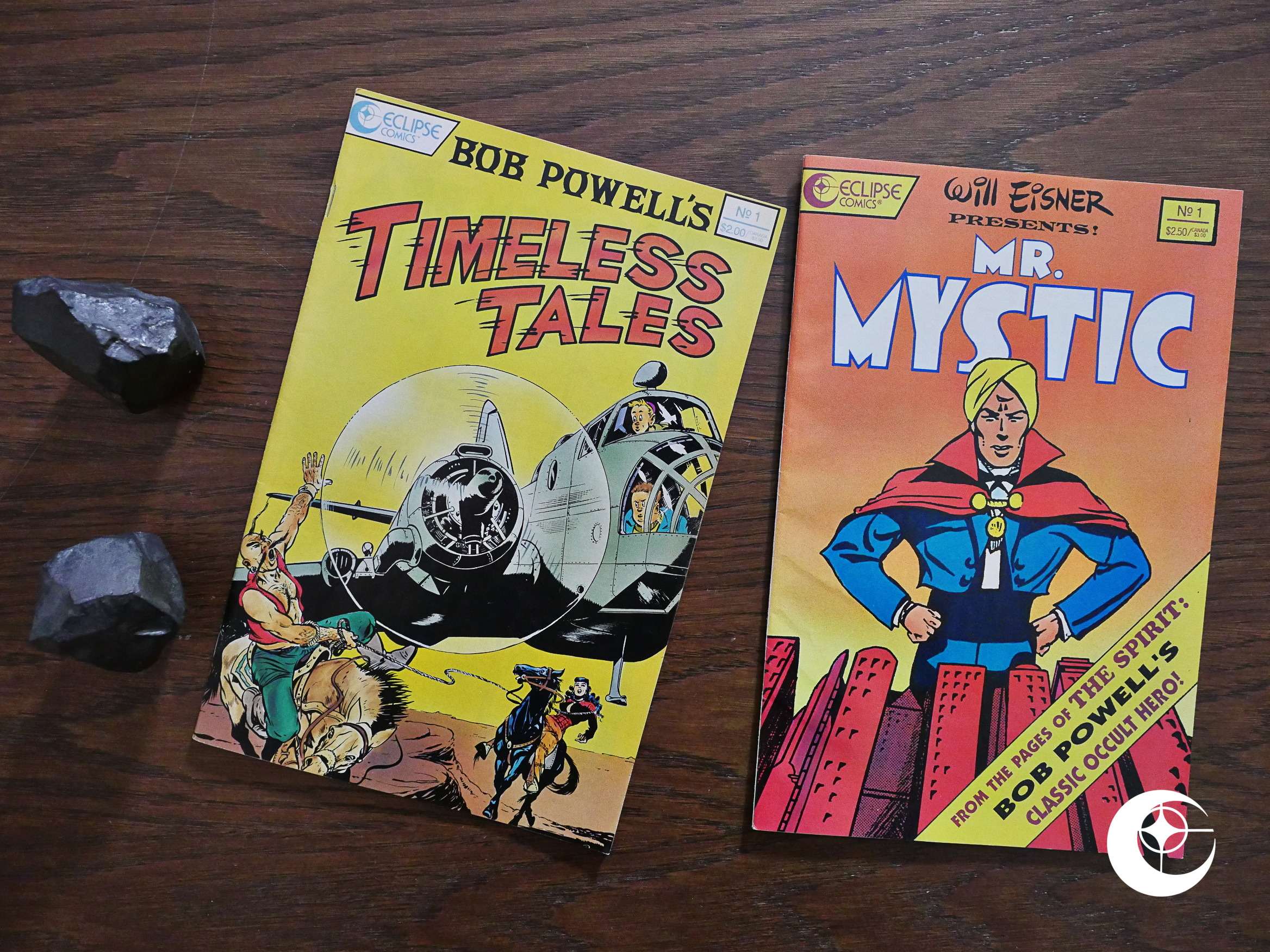

Swordsmen and Saurians (1989) Bob Powell’s Timeless Tales (1989) #1

Bob Powell’s Timeless Tales (1989) #1 Cyber 7 (1989) #1-7

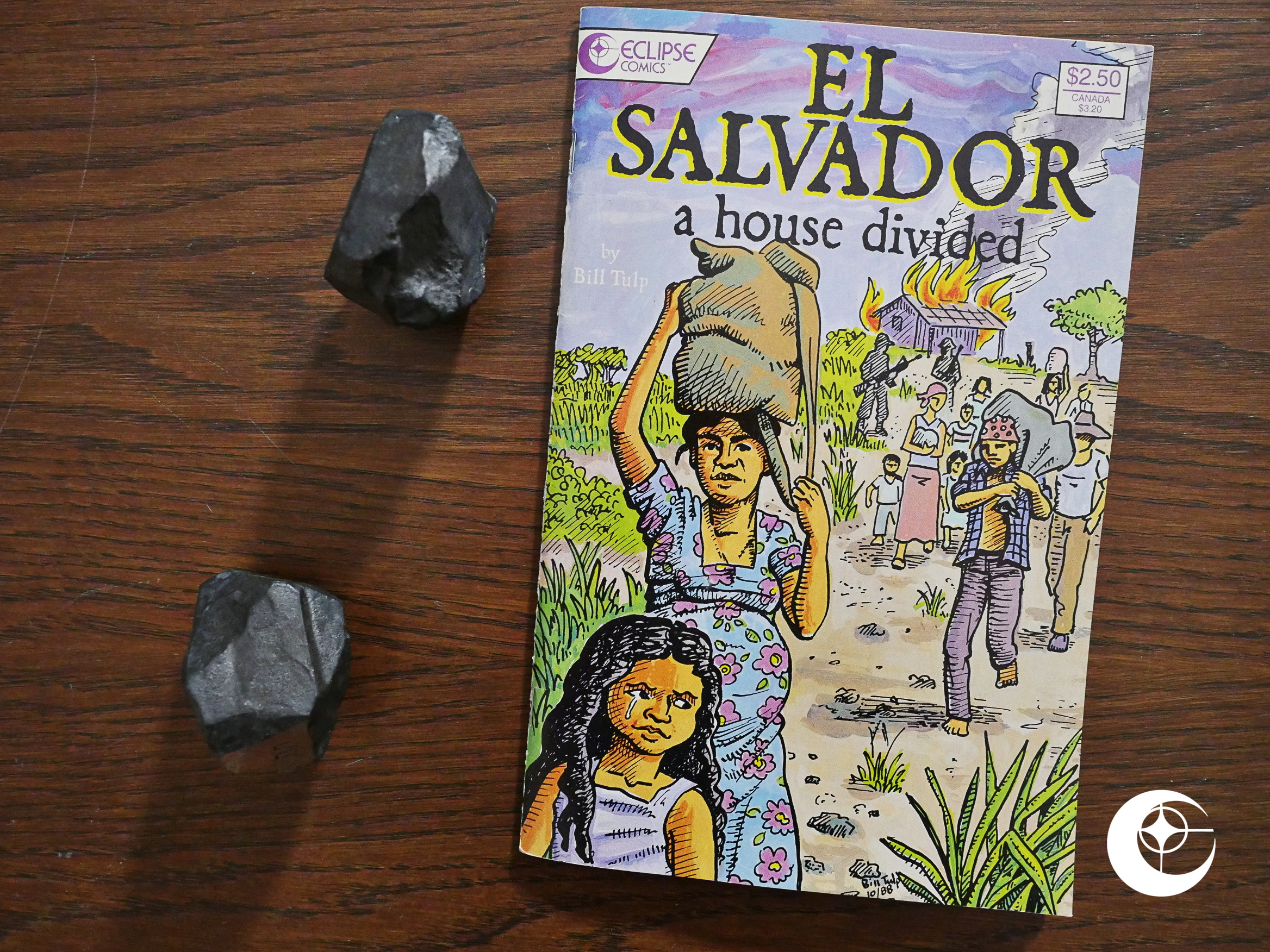

Cyber 7 (1989) #1-7 El Salvador: A House Divided (1989)

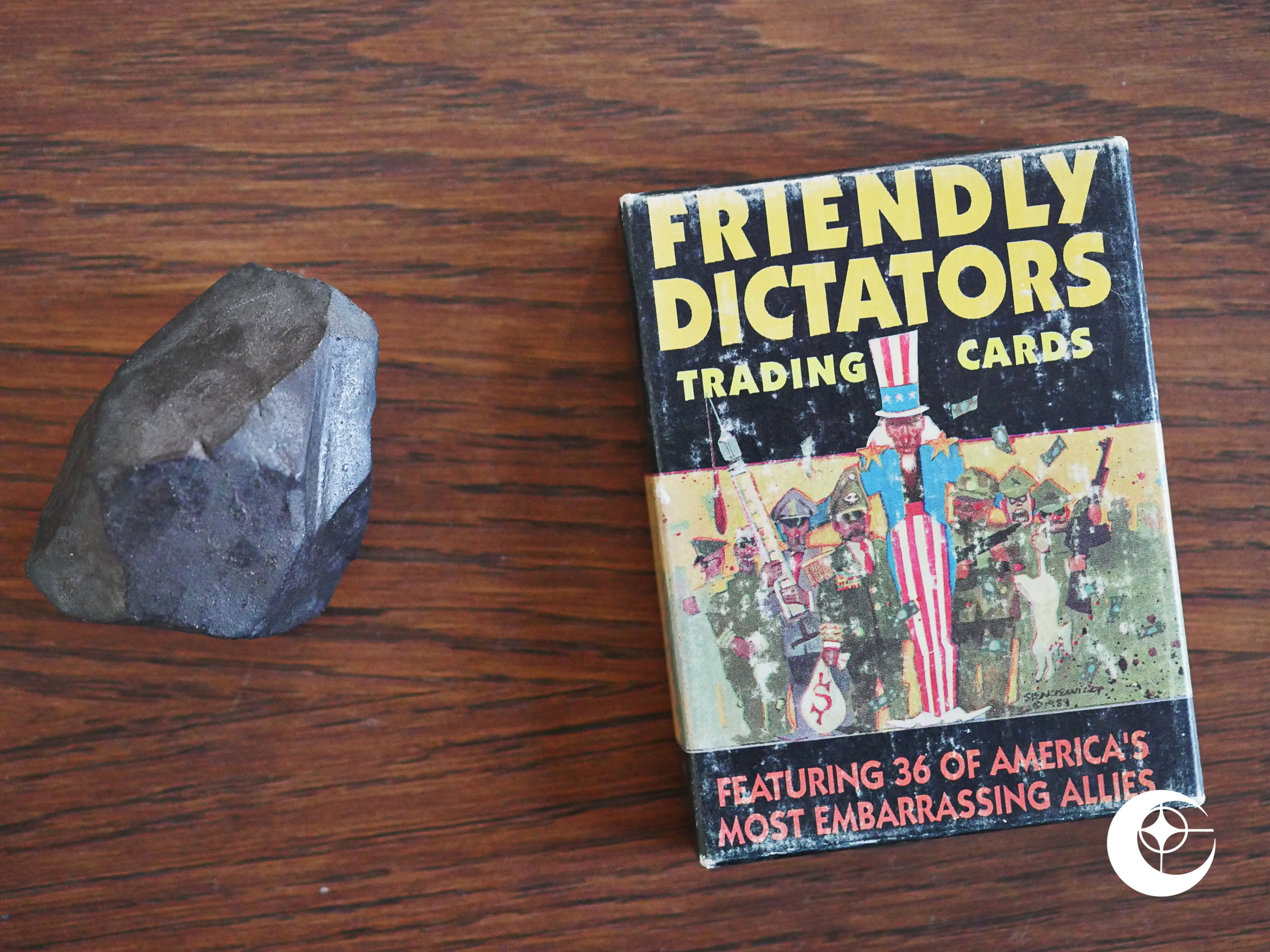

El Salvador: A House Divided (1989) Friendly Dictators Trading Cards (1989) #1

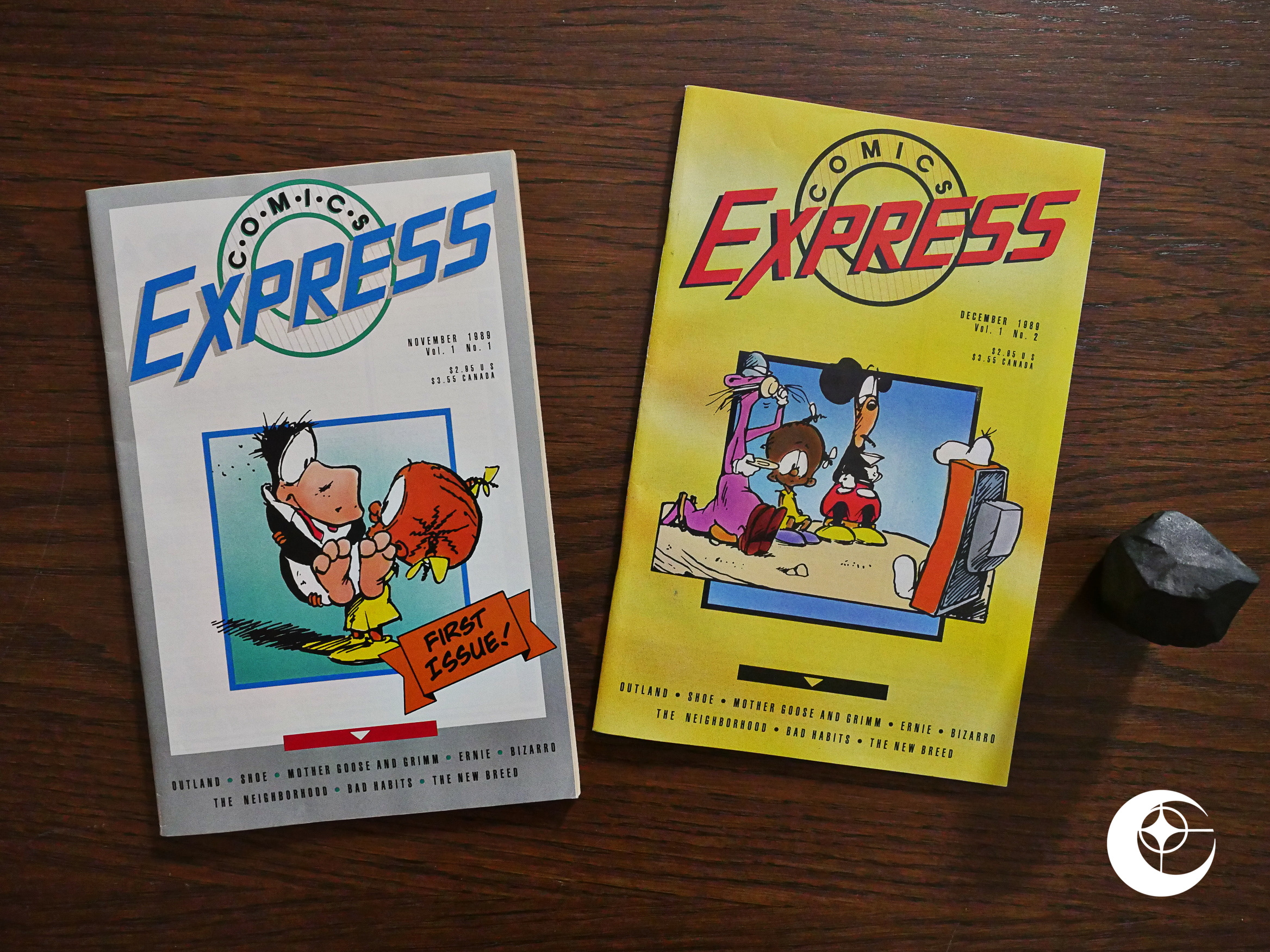

Friendly Dictators Trading Cards (1989) #1 Comics Express (1989) #1-2

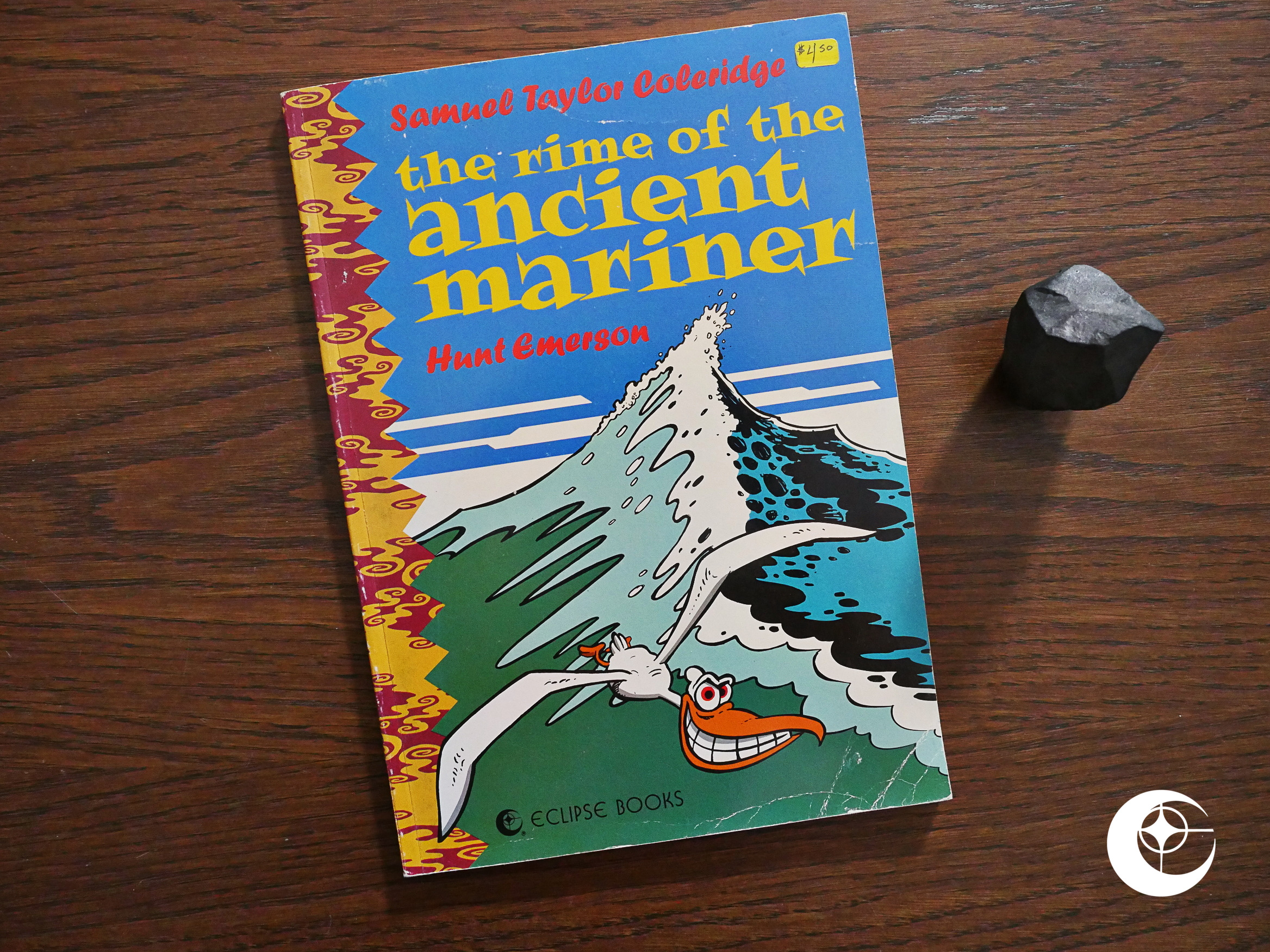

Comics Express (1989) #1-2 The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1989)

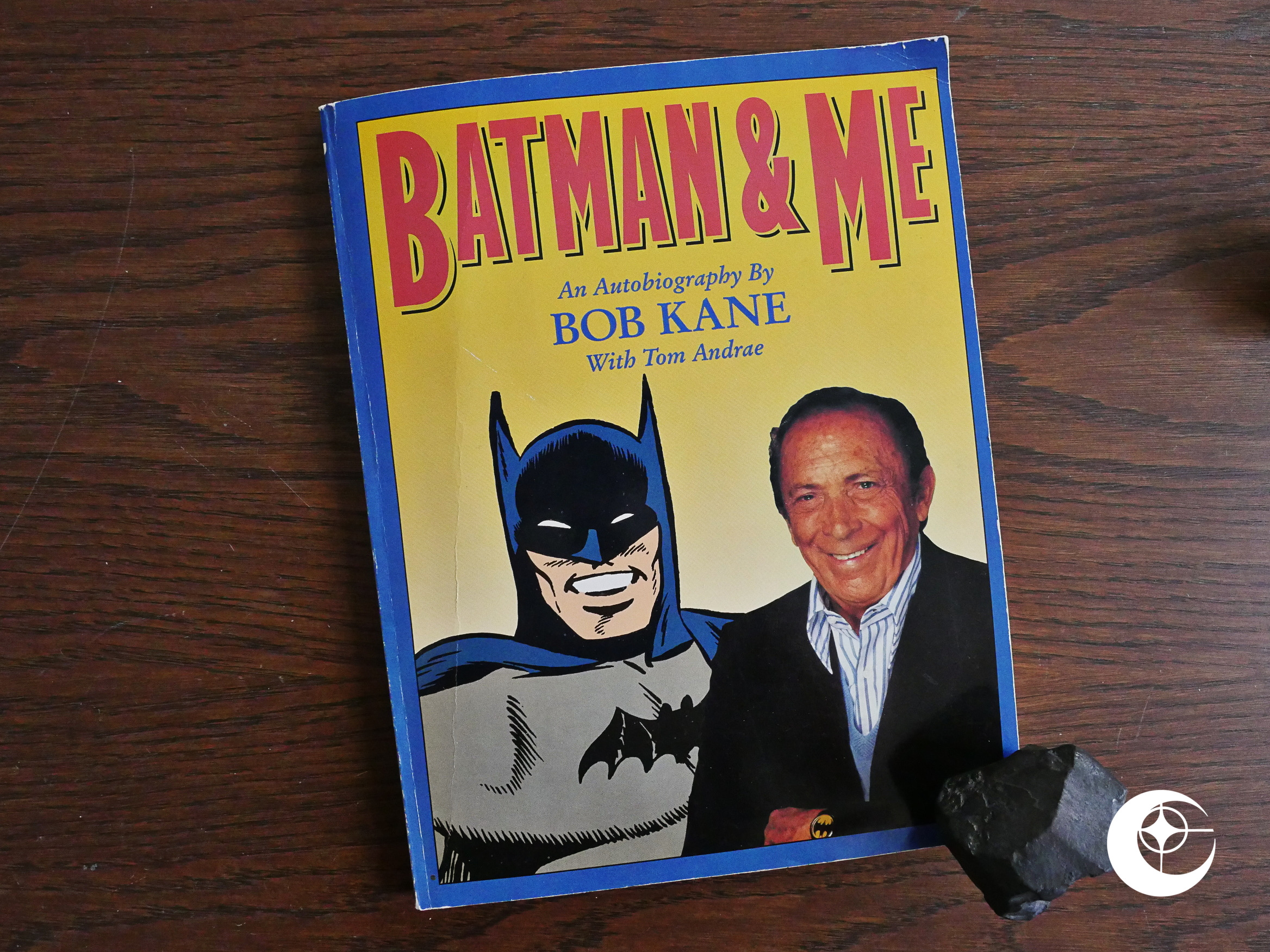

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1989) Batman & Me (1989)

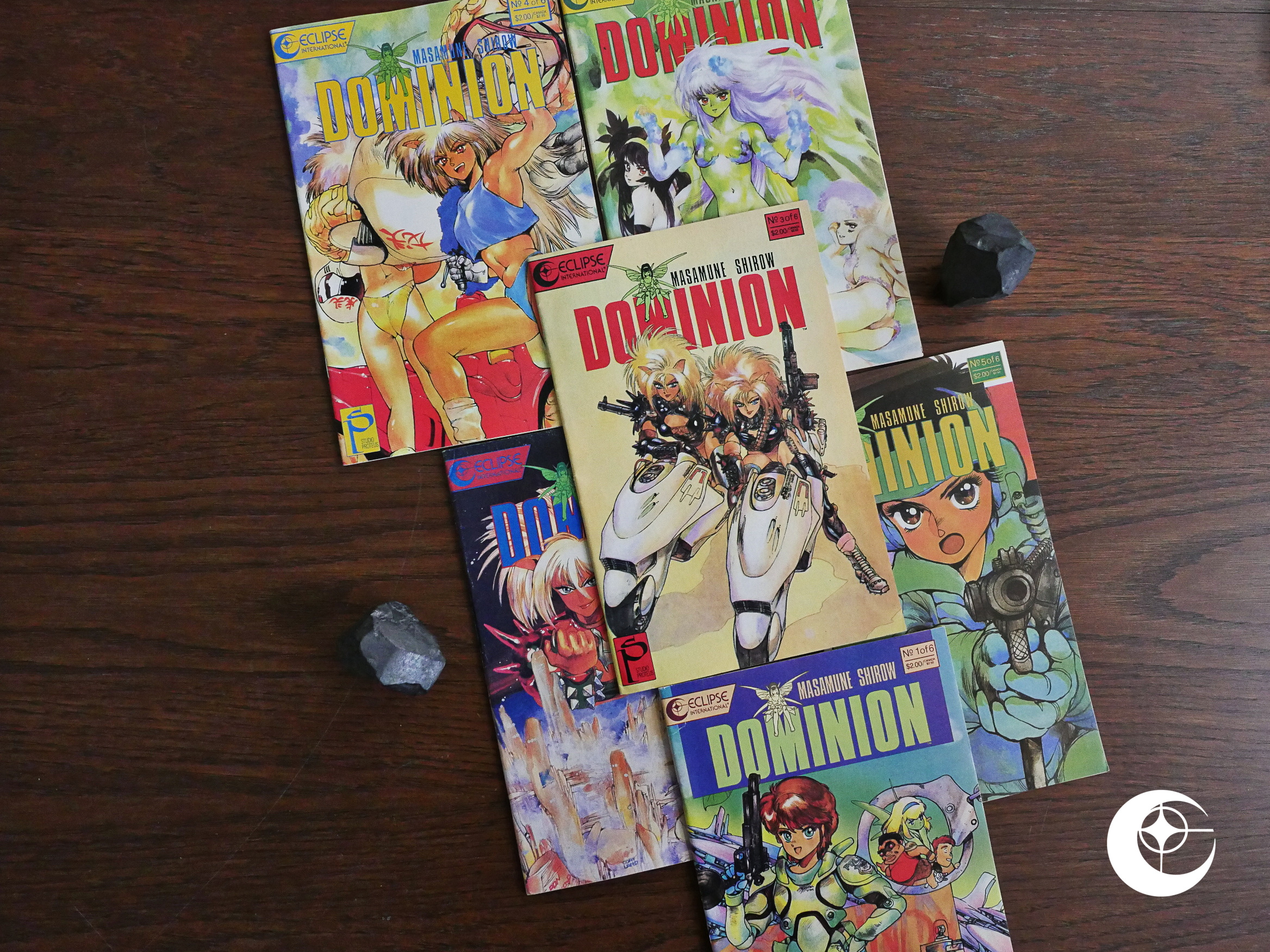

Batman & Me (1989) Dominion (1989) #1-6

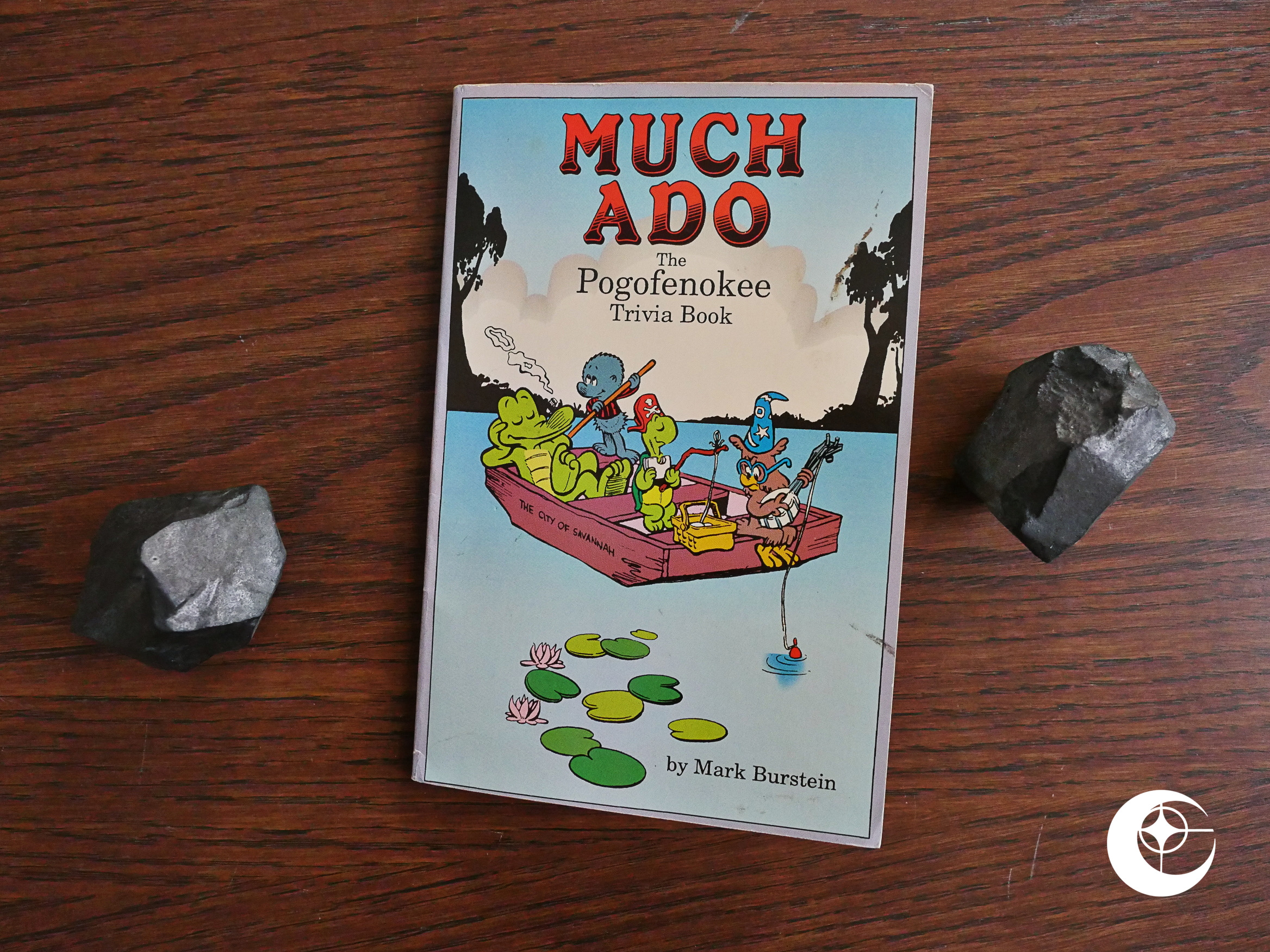

Dominion (1989) #1-6 by Walt Kelly, Much Ado: The Pogofenokee Trivia Book (1990)

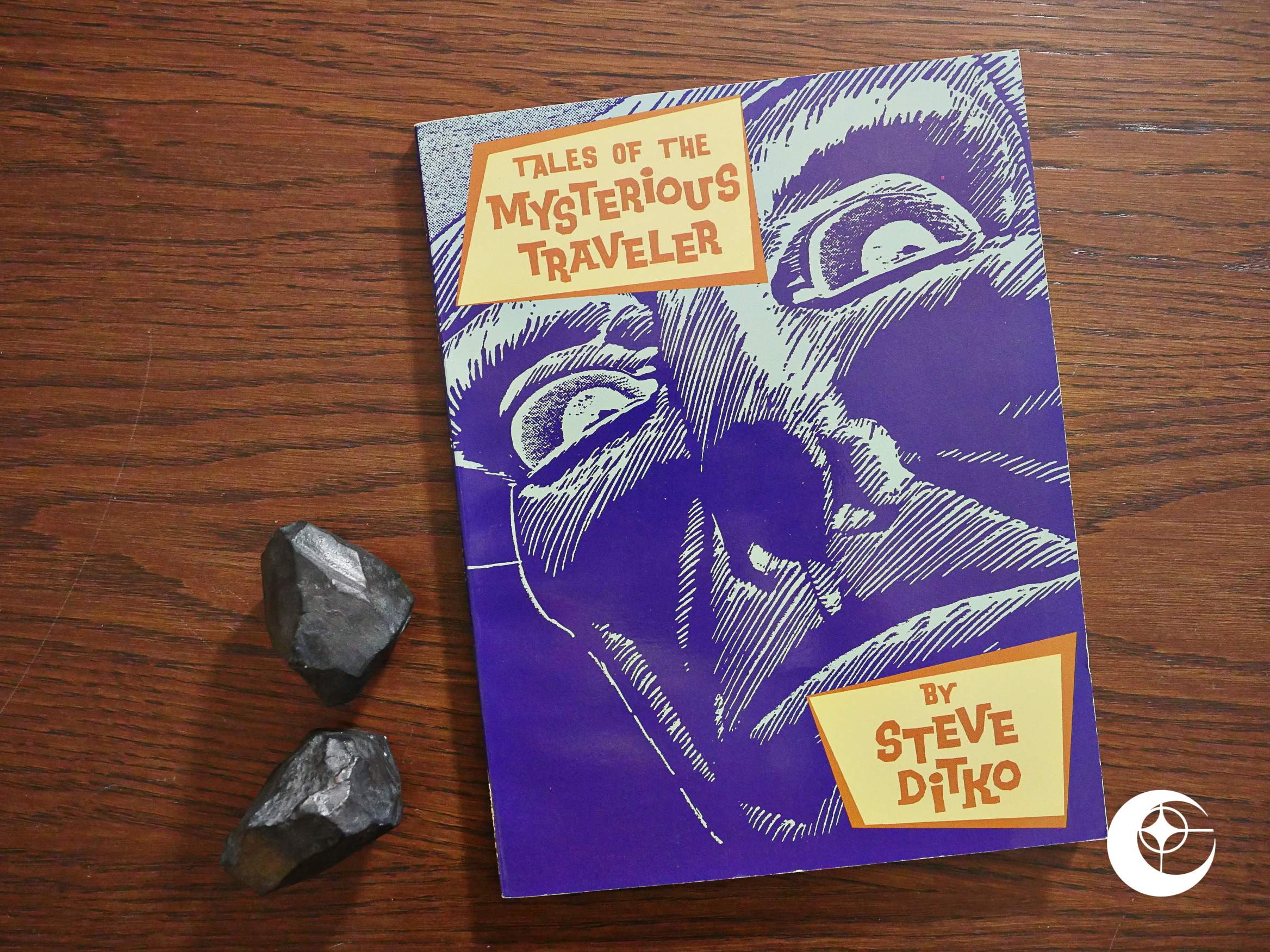

by Walt Kelly, Much Ado: The Pogofenokee Trivia Book (1990) Tales of the Mysterious Traveler (1990)

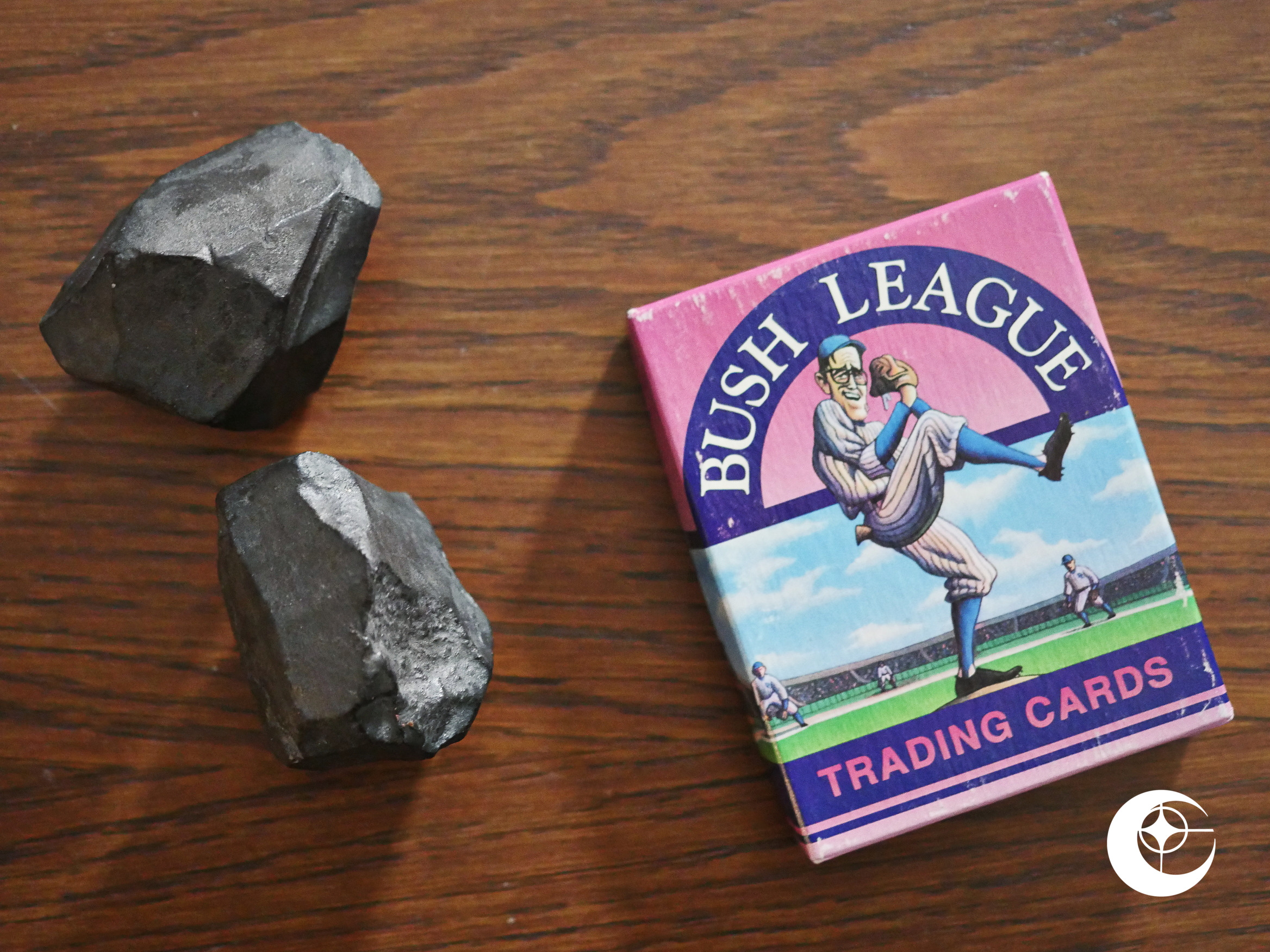

Tales of the Mysterious Traveler (1990) Bush League Trading Cards (1990)

Bush League Trading Cards (1990) Black Magic (1990) #1-4

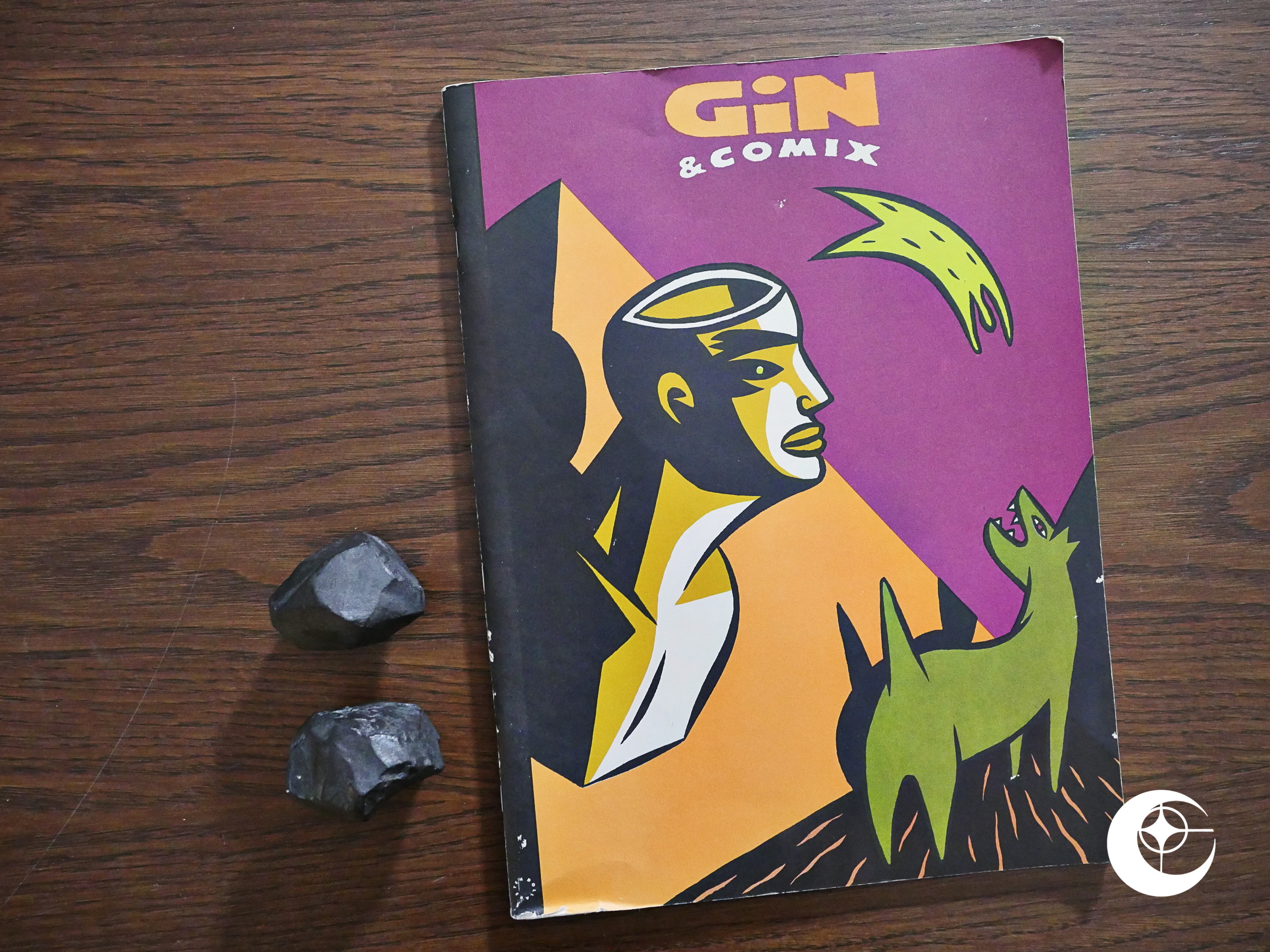

Black Magic (1990) #1-4 Gin and Comix (1990) #1

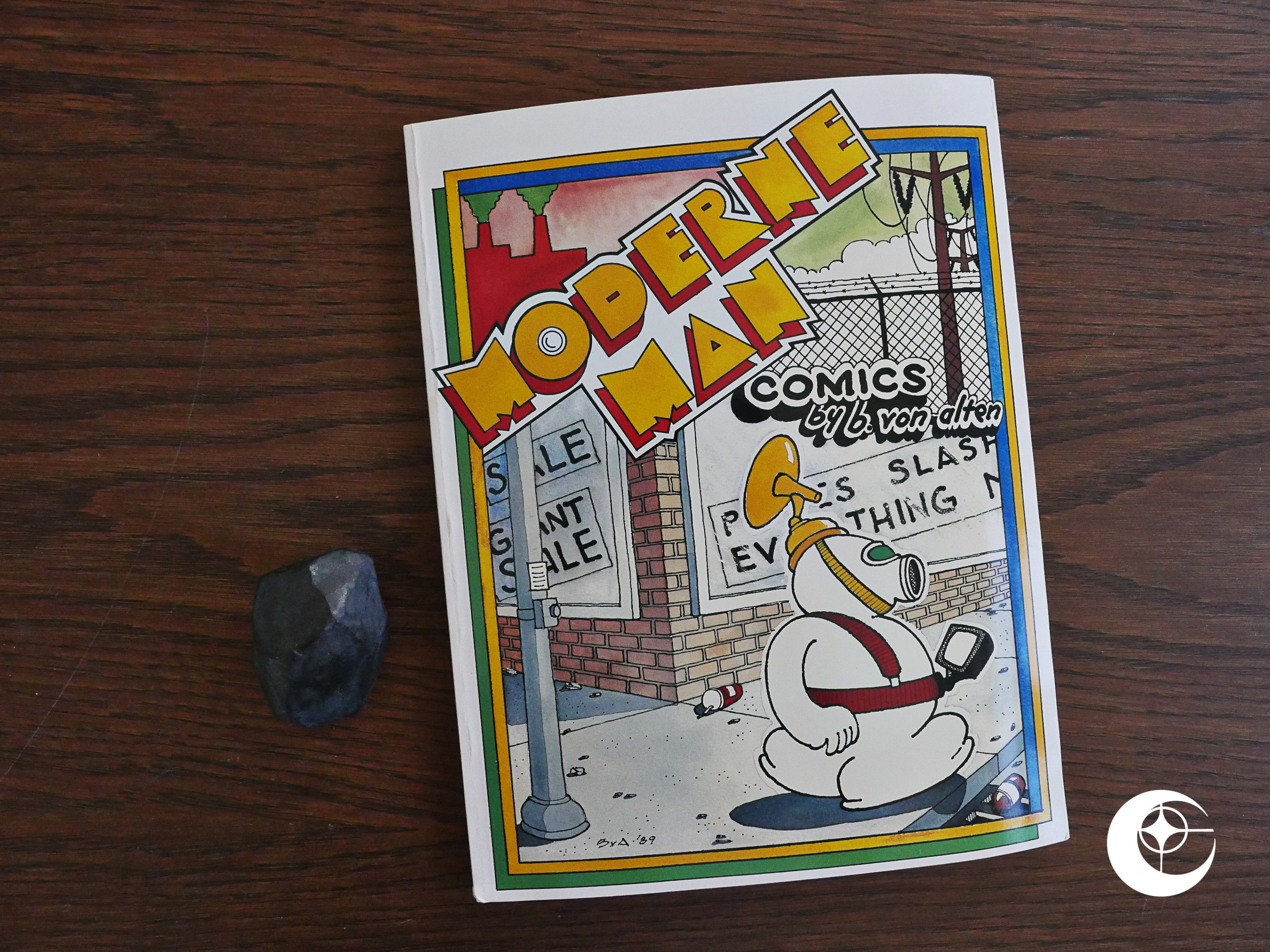

Gin and Comix (1990) #1 Moderne Man Comics (1990) #1

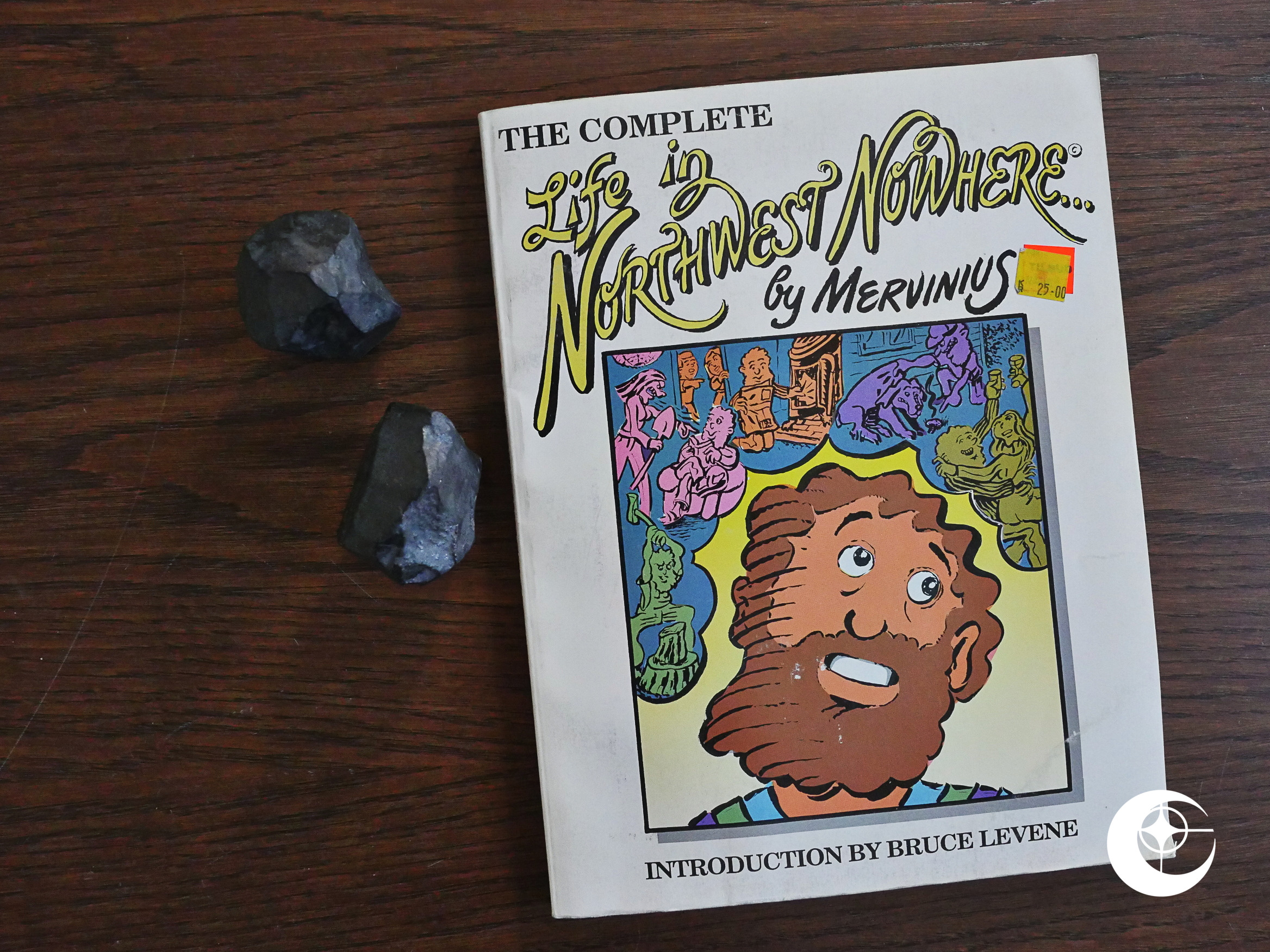

Moderne Man Comics (1990) #1 Life in Northwest Nowhere (1990)

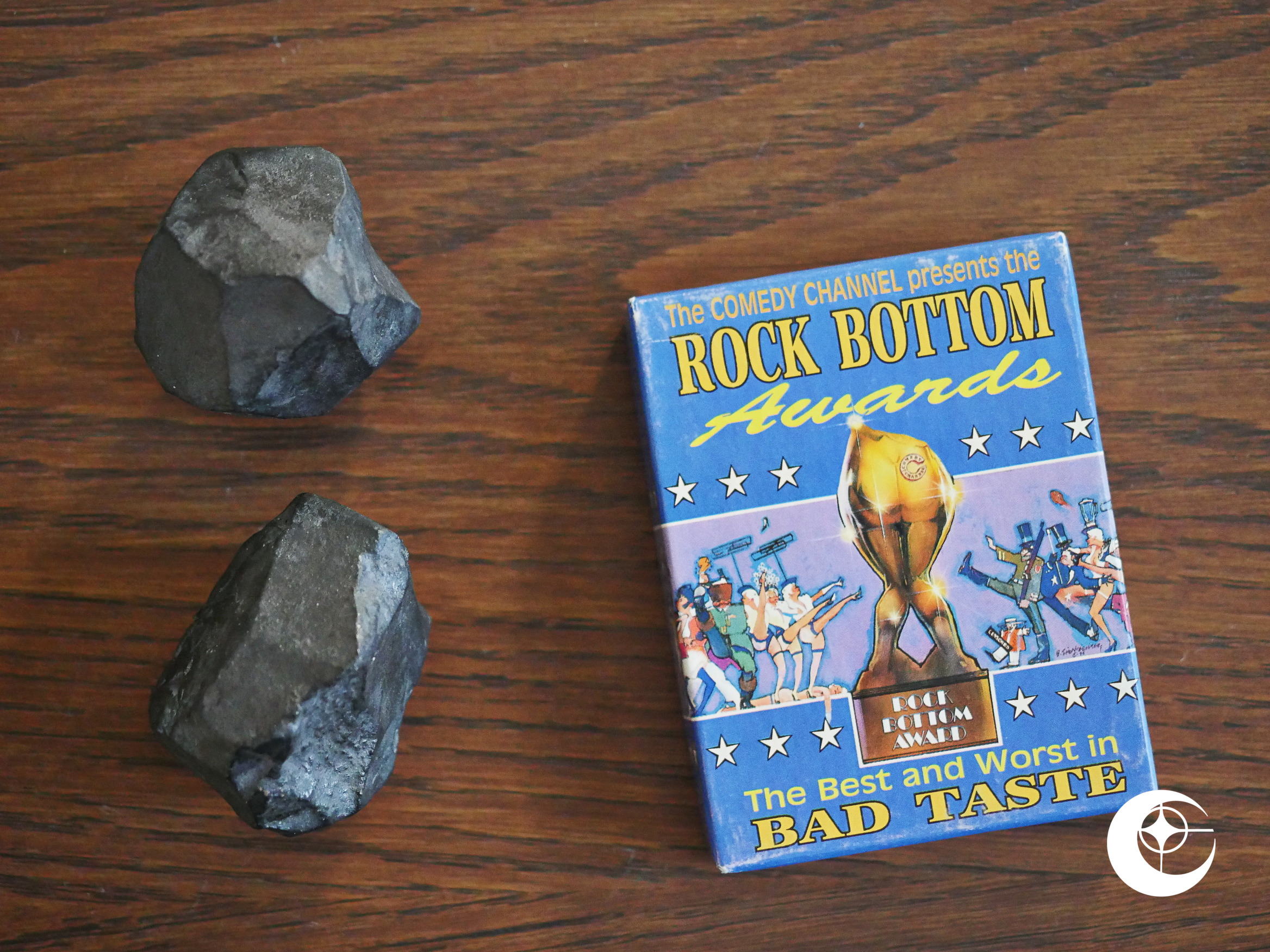

Life in Northwest Nowhere (1990) Rock Bottom Trading Cards (1990)

Rock Bottom Trading Cards (1990) Lost Continent (1990) #1-6

Lost Continent (1990) #1-6 Words Without Pictures (1990)

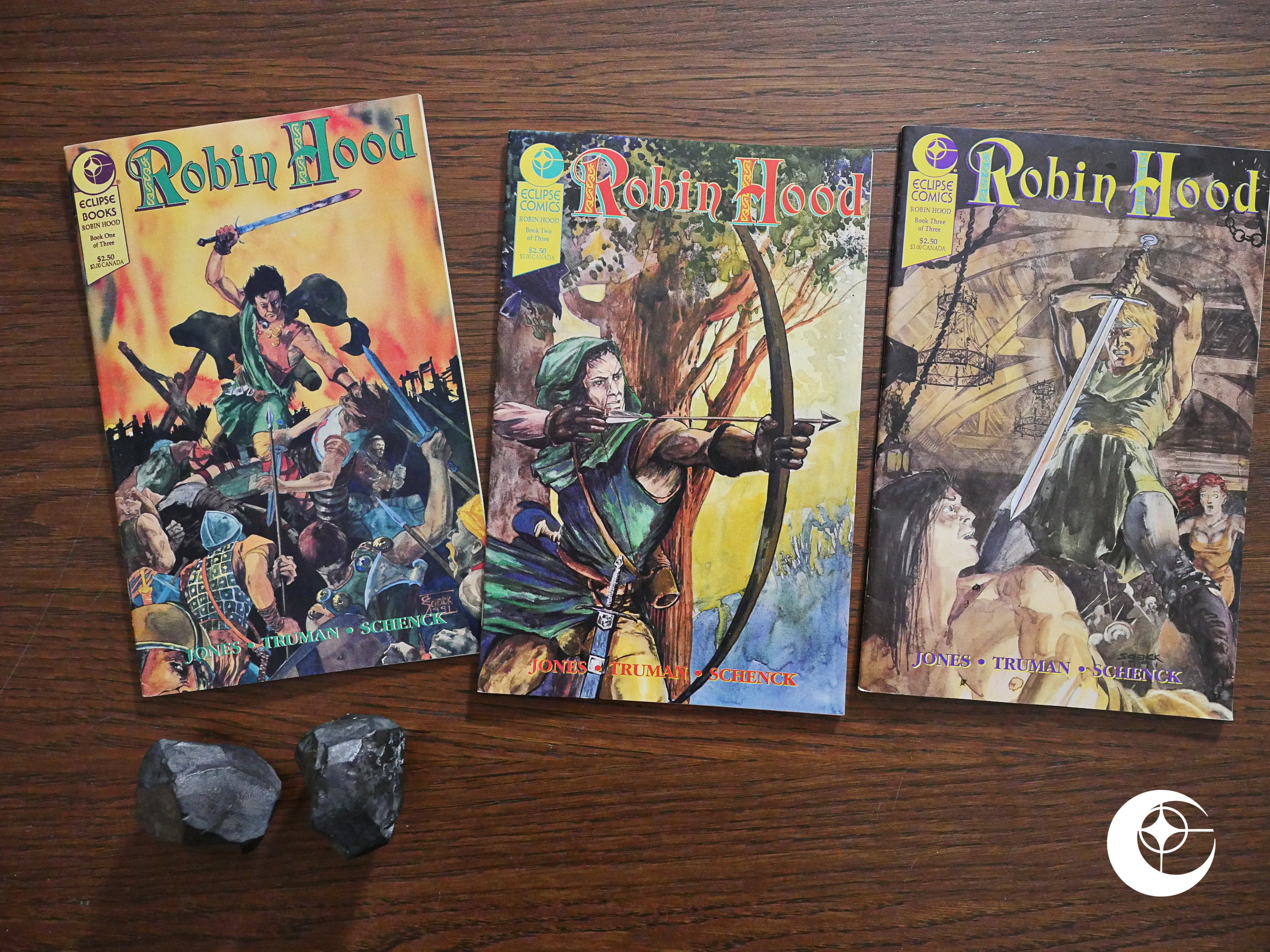

Words Without Pictures (1990) Robin Hood (1991) #1-3

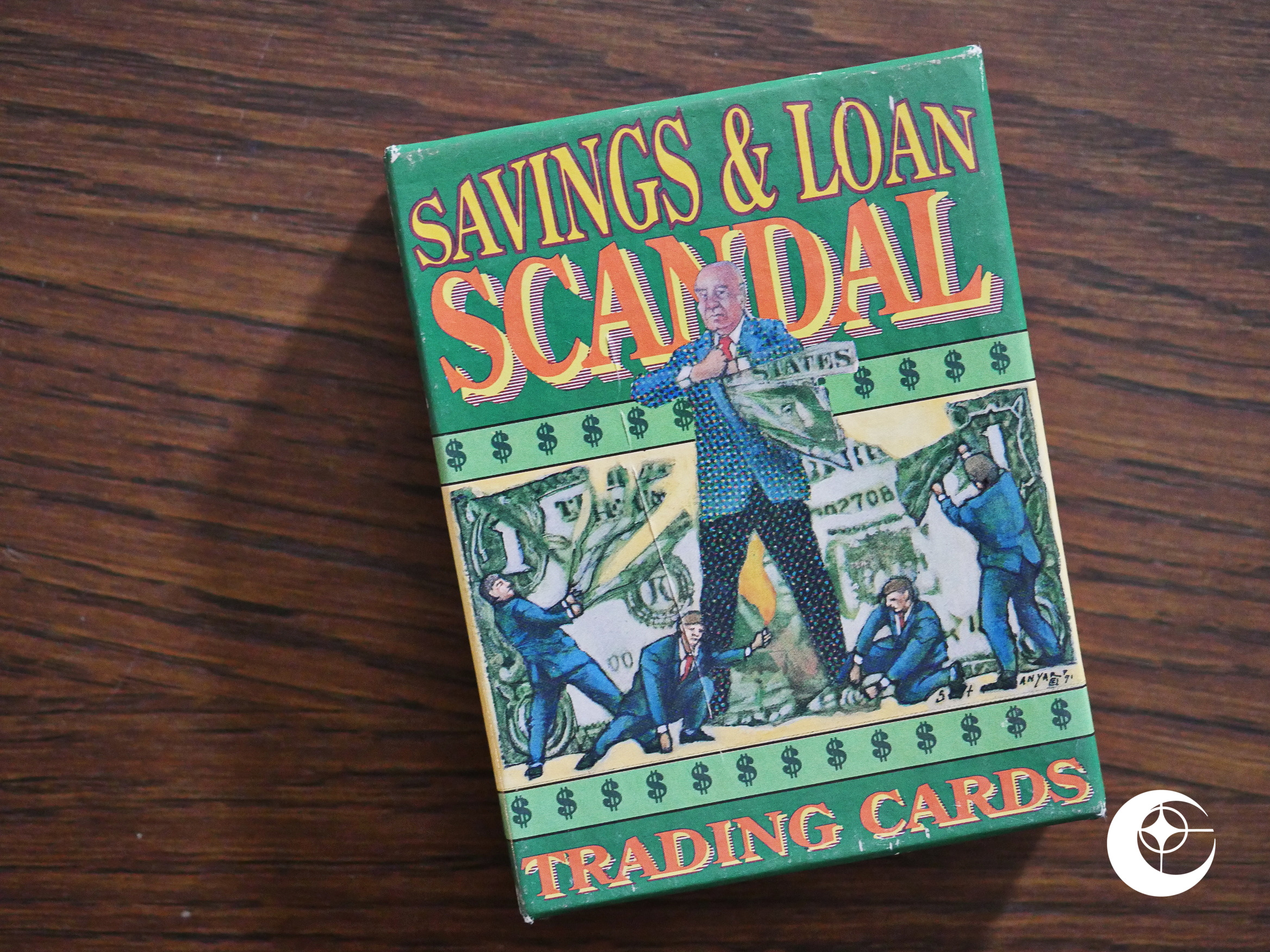

Robin Hood (1991) #1-3 The Savings and Loans Scandal Trading Cards (1991)

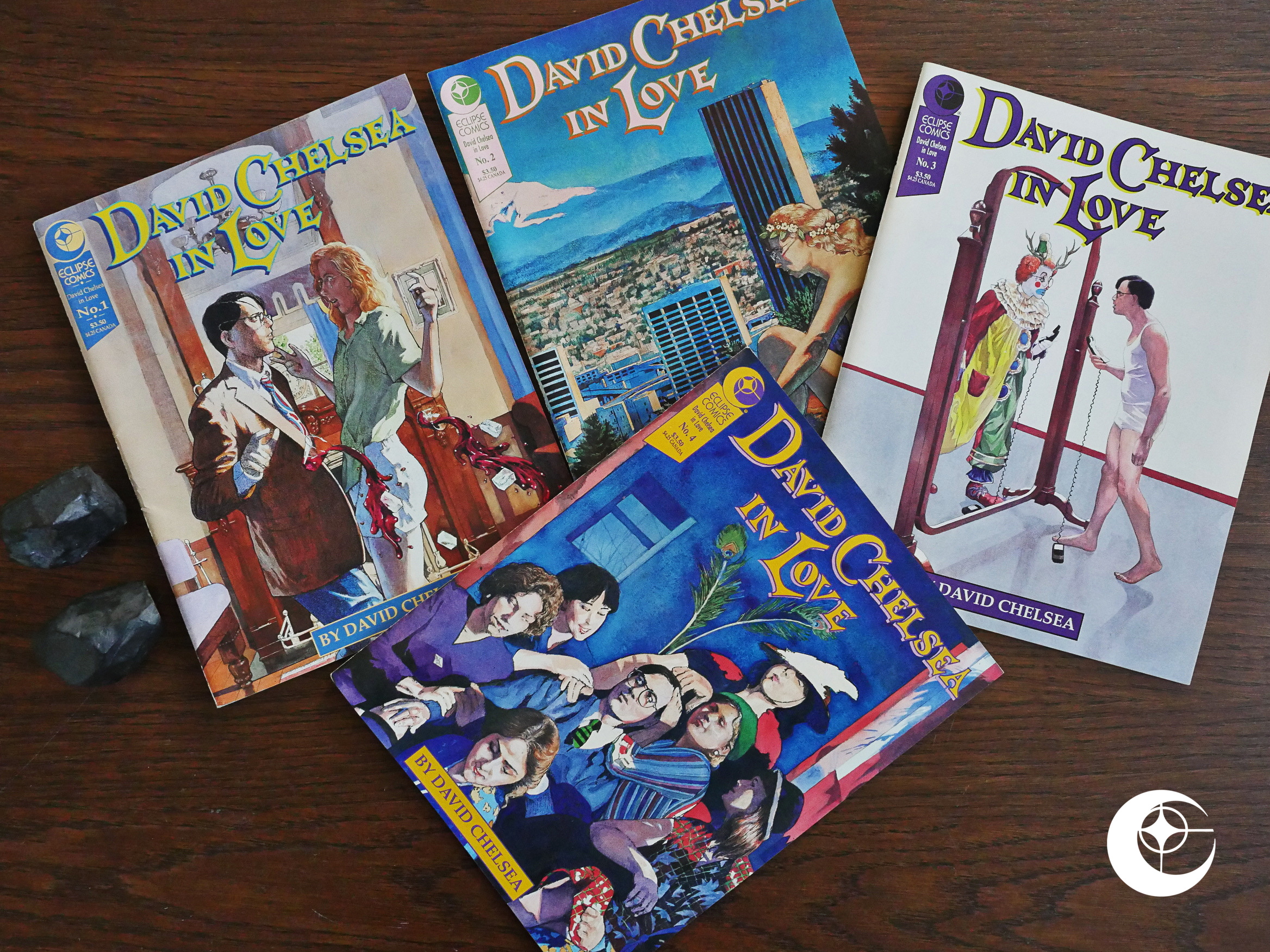

The Savings and Loans Scandal Trading Cards (1991) David Chelsea in Love (1991) #1-4

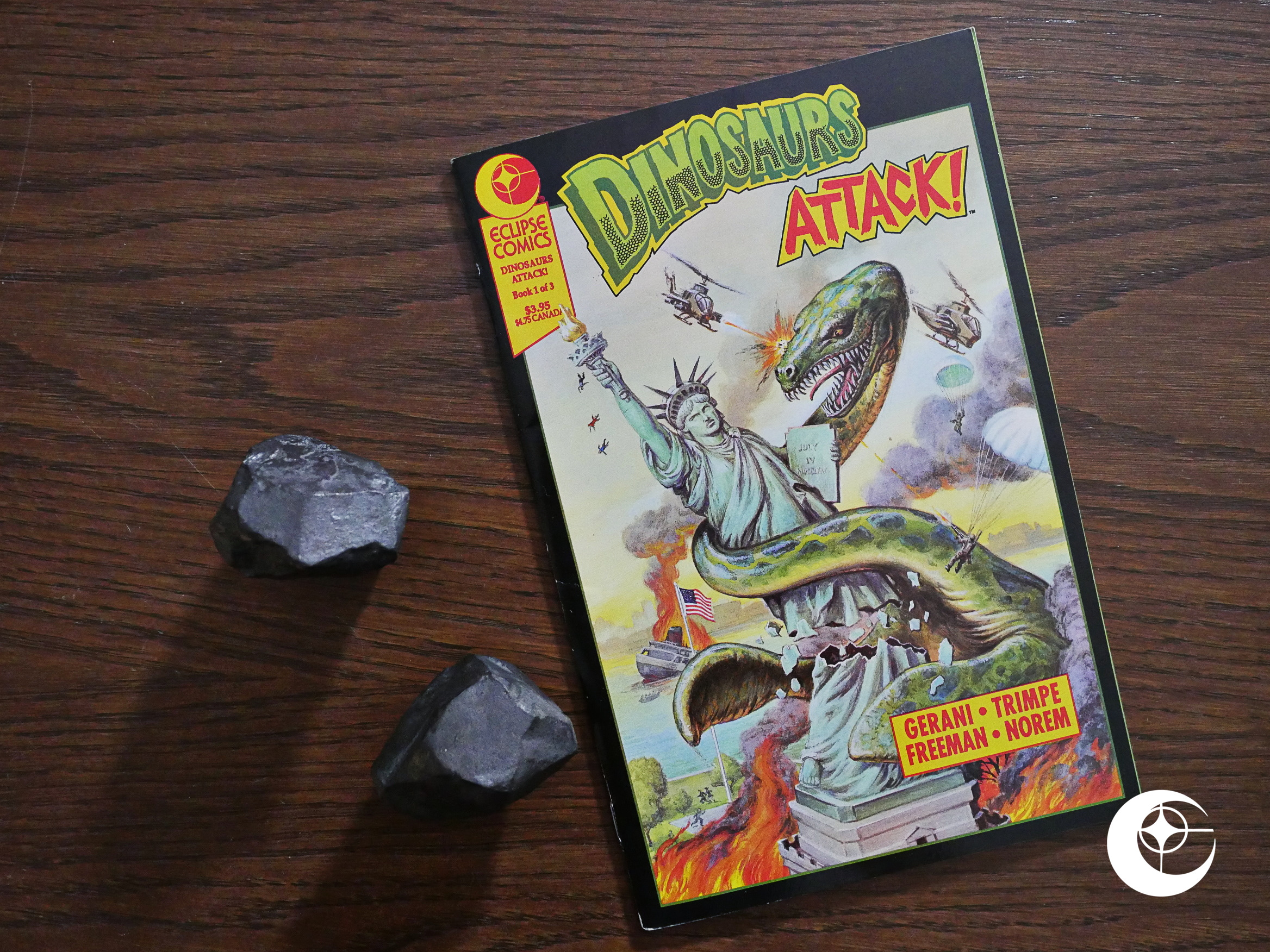

David Chelsea in Love (1991) #1-4 Dinosaurs Attack! The Graphic Novel (1991) #1

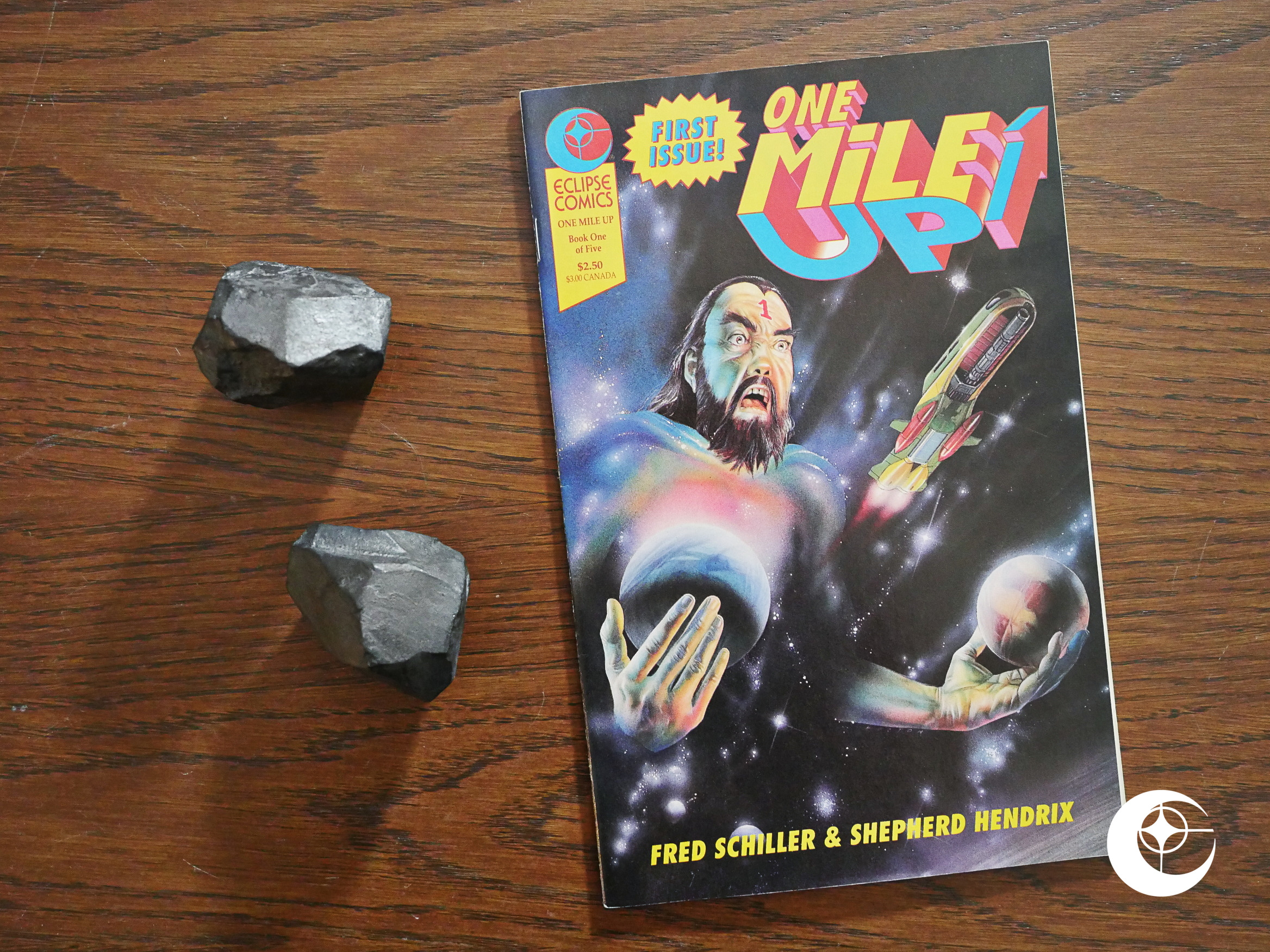

Dinosaurs Attack! The Graphic Novel (1991) #1 One Mile Up (1991) #1

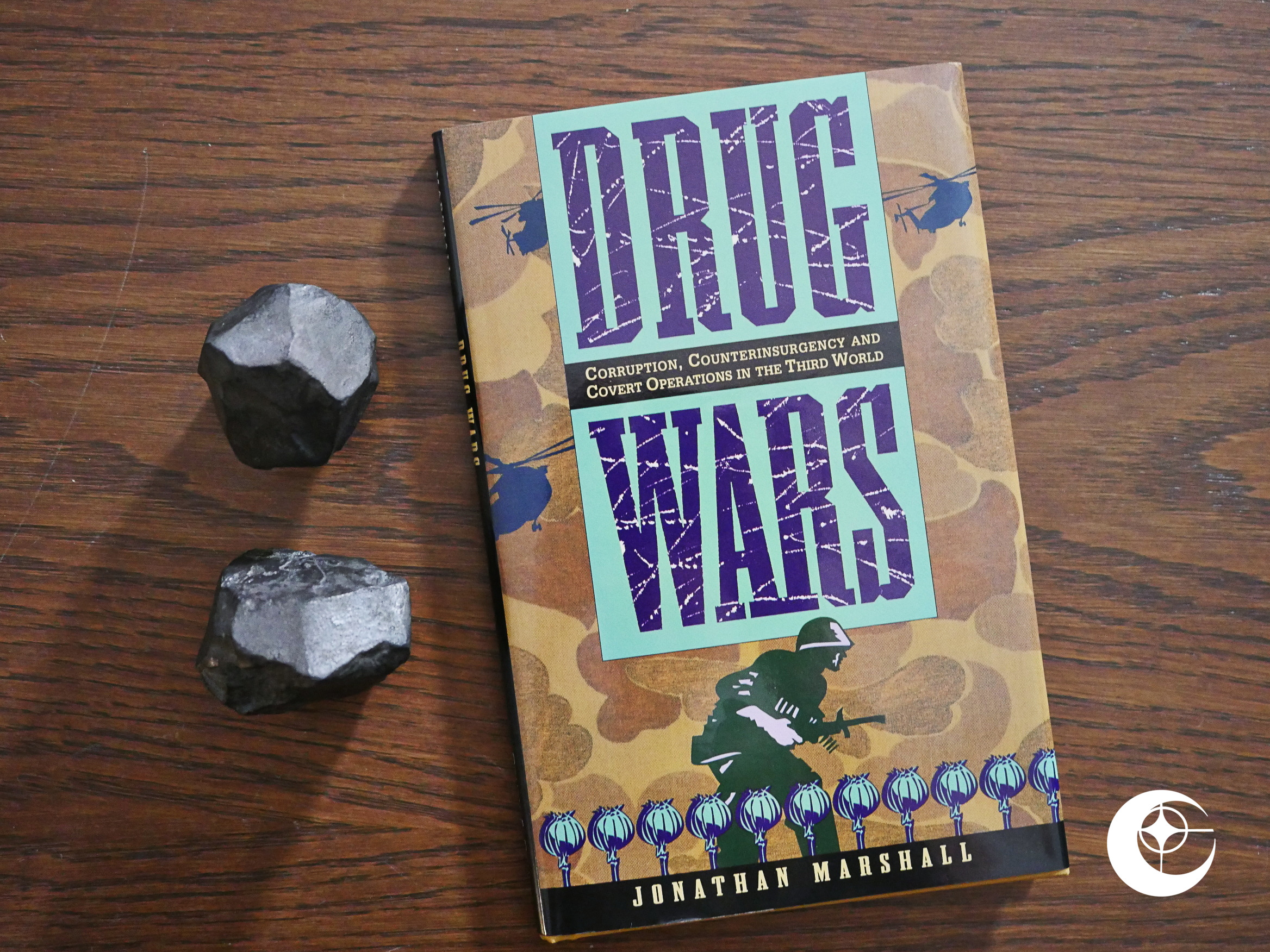

One Mile Up (1991) #1 Drug Wars (1991)

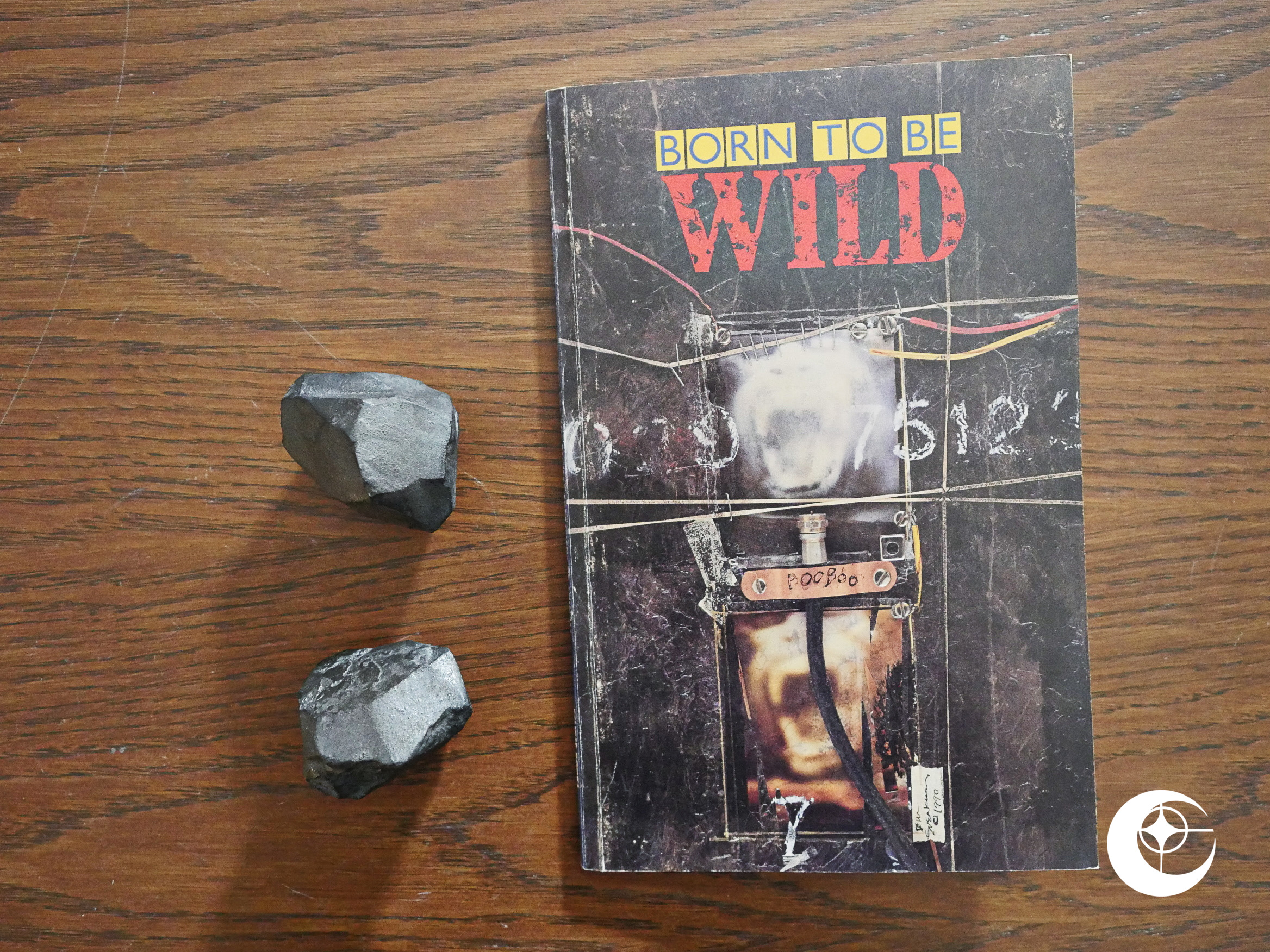

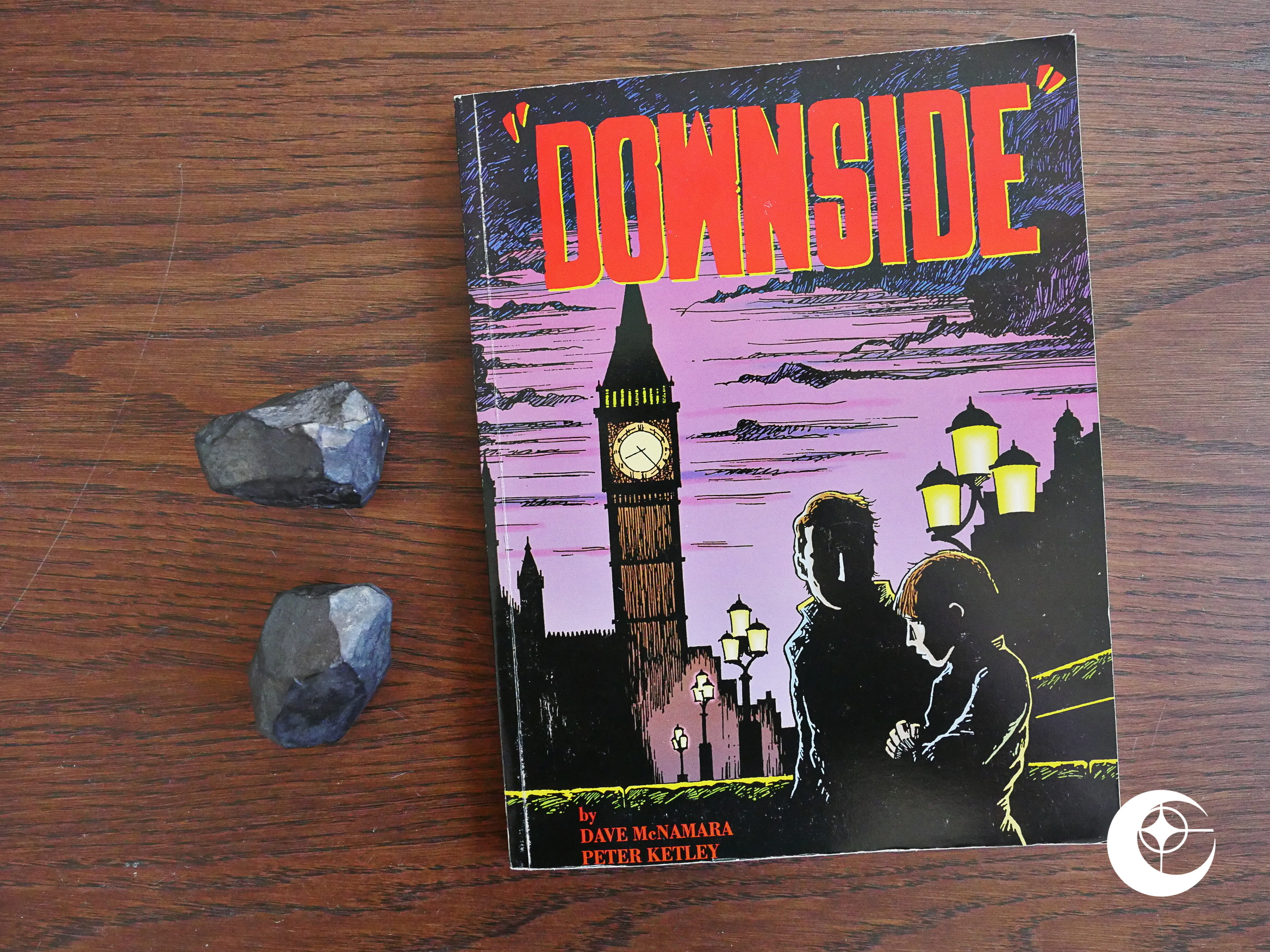

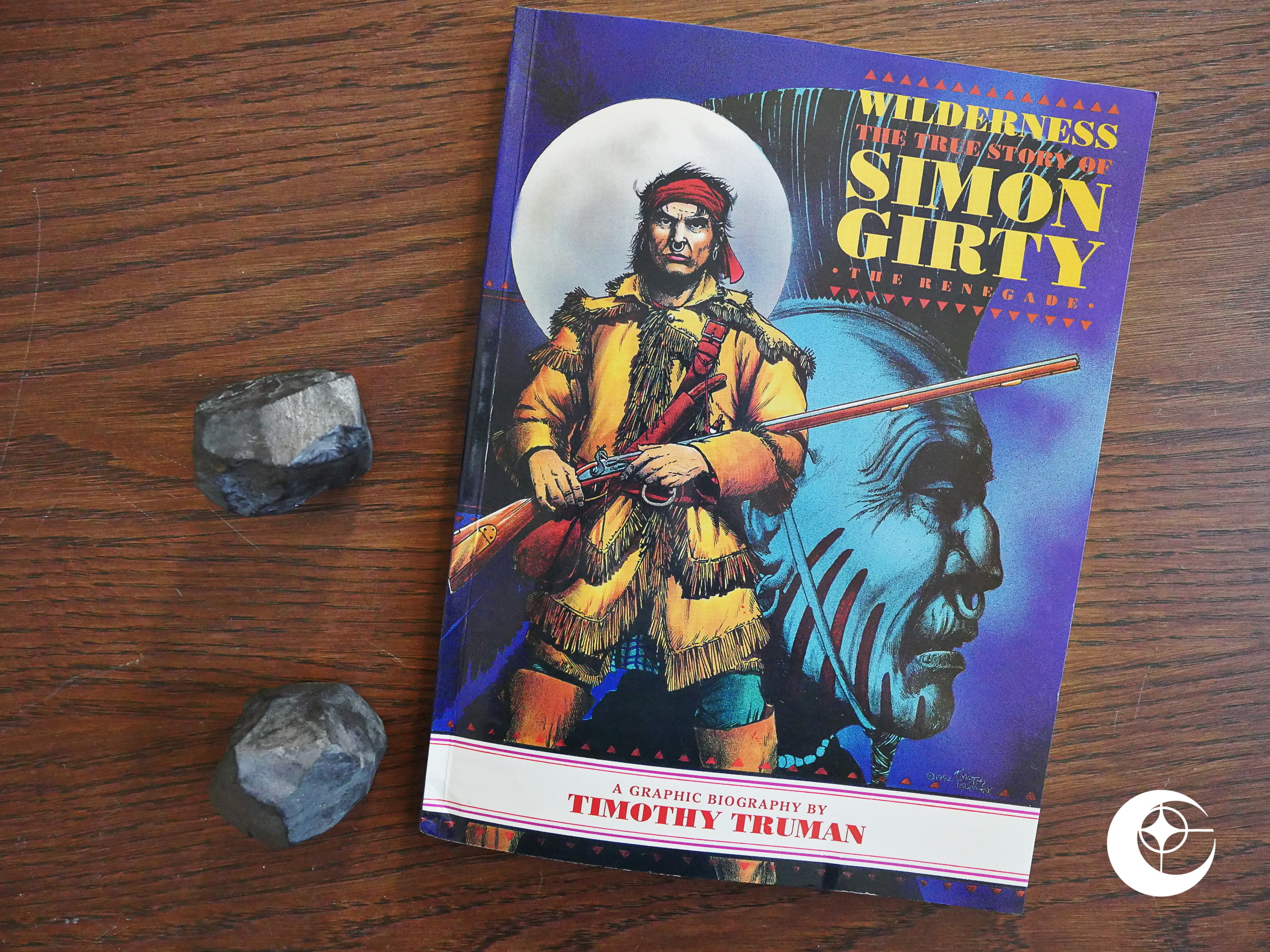

Drug Wars (1991) Wilderness: The True Story of Simon Girty (1992)

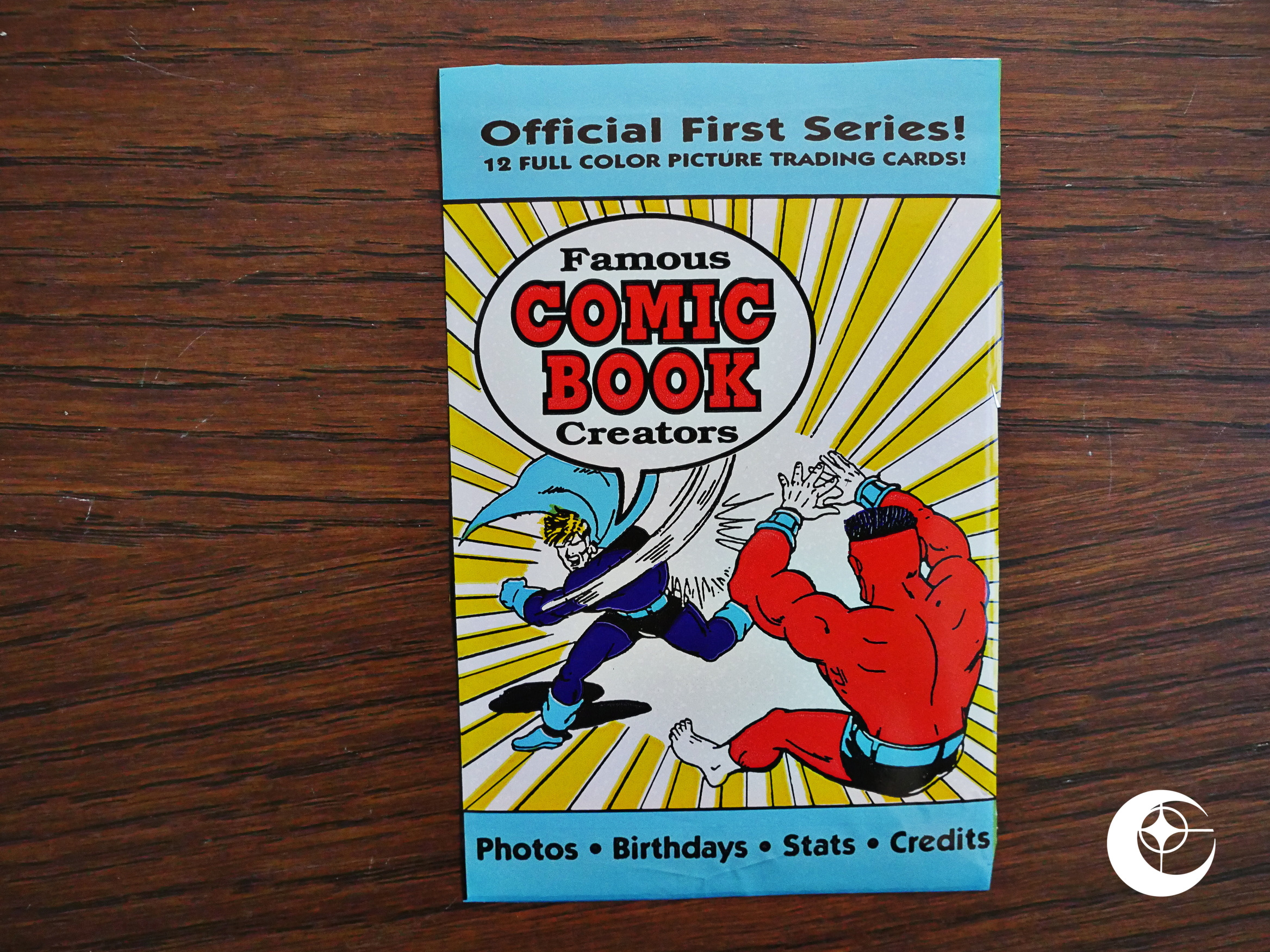

Wilderness: The True Story of Simon Girty (1992) Famous Comic Book Creators Trading Cards (1992)

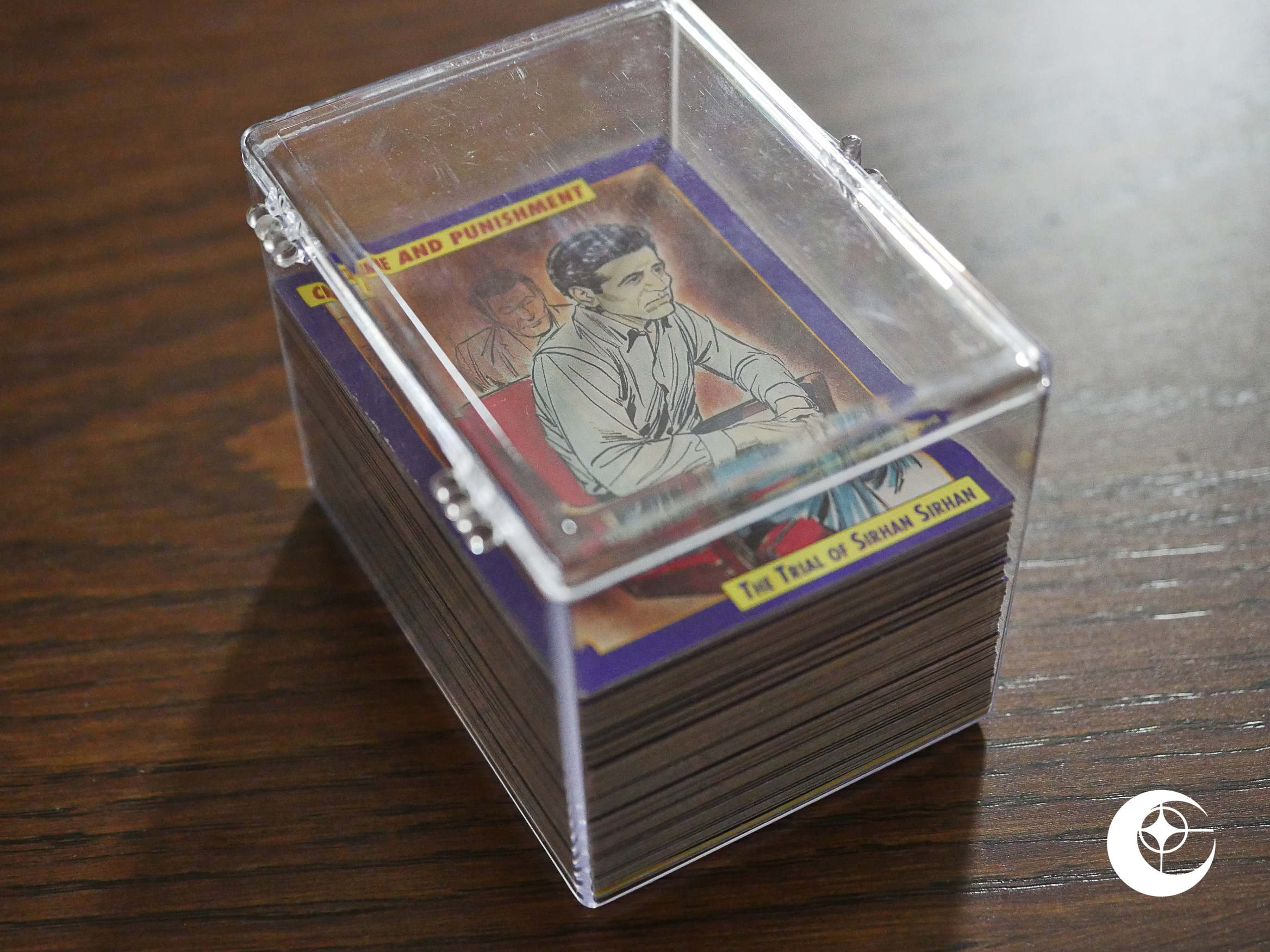

Famous Comic Book Creators Trading Cards (1992) Crime and Punishment Trading Cards (1992)

Crime and Punishment Trading Cards (1992) X-Farce (1992) #1

X-Farce (1992) #1 Mad Dogs (1992) #1-3

Mad Dogs (1992) #1-3 Metaphysique (1992) #1-2

Metaphysique (1992) #1-2 Blood is the Harvest (1992) #1-4

Blood is the Harvest (1992) #1-4 Parts Unknown (1992) #1-4

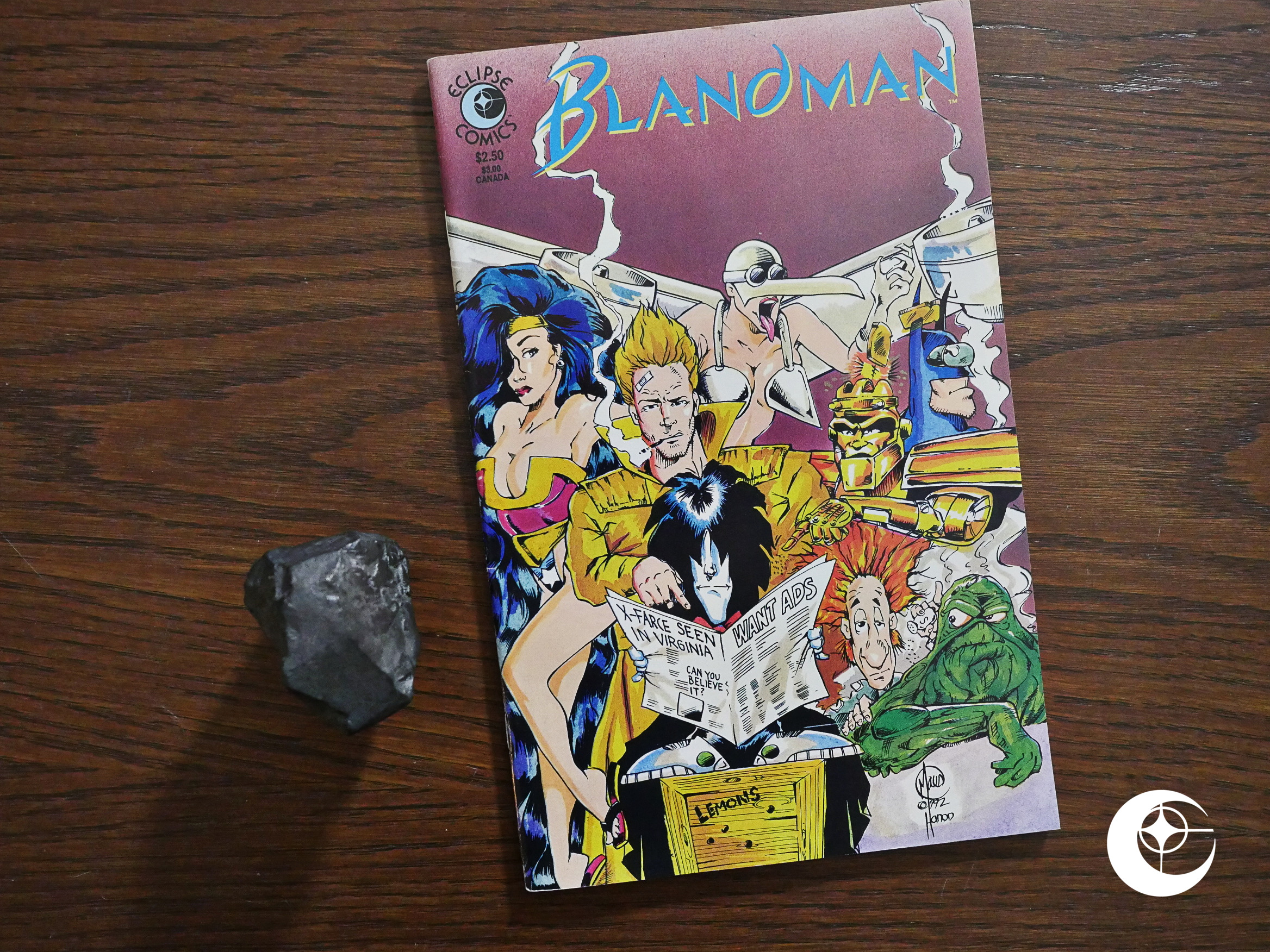

Parts Unknown (1992) #1-4 Blandman (1992) #1

Blandman (1992) #1 Retaliator (1992) #1-4

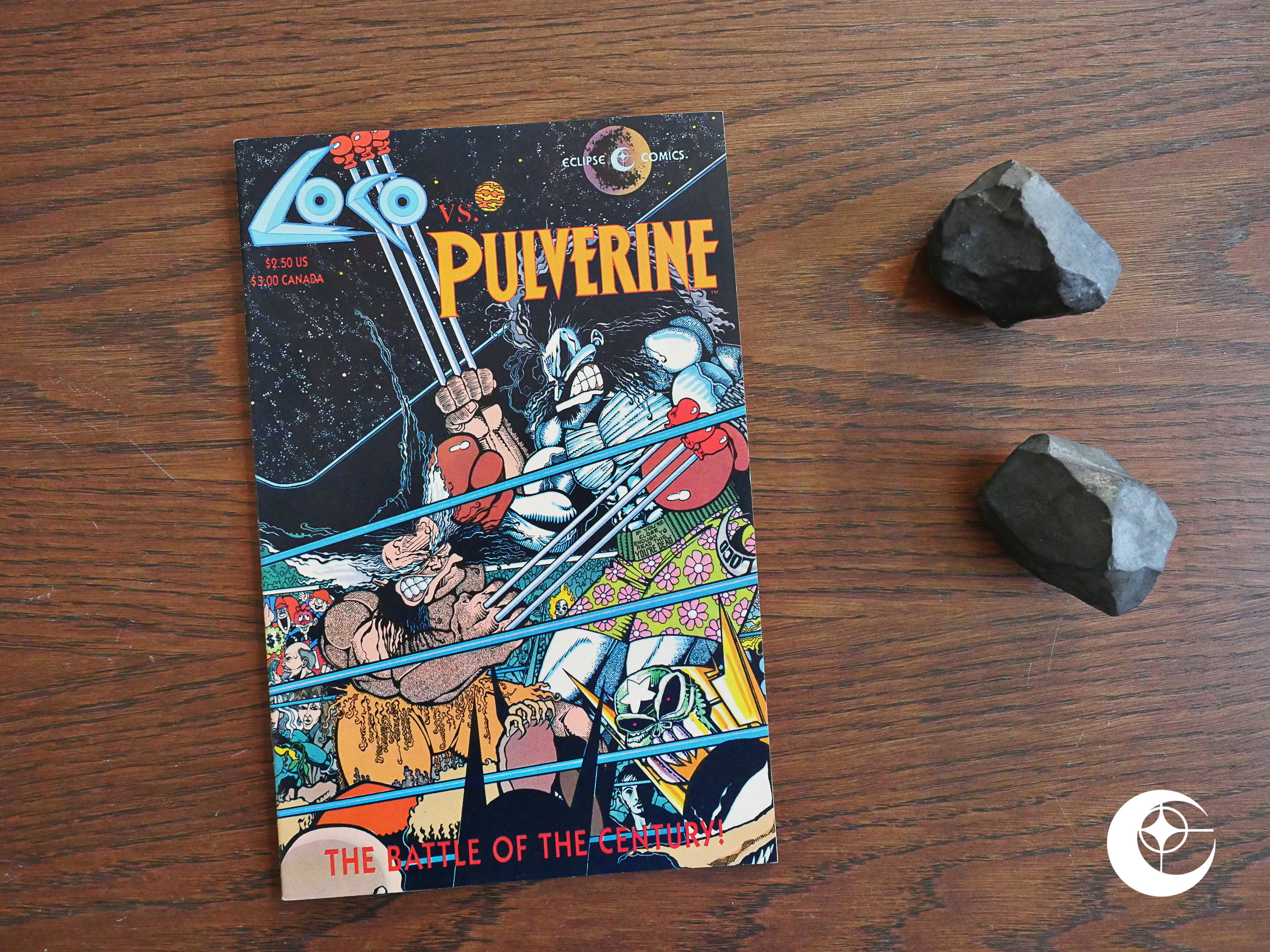

Retaliator (1992) #1-4 Loco vs. Pulverine (1992) #1

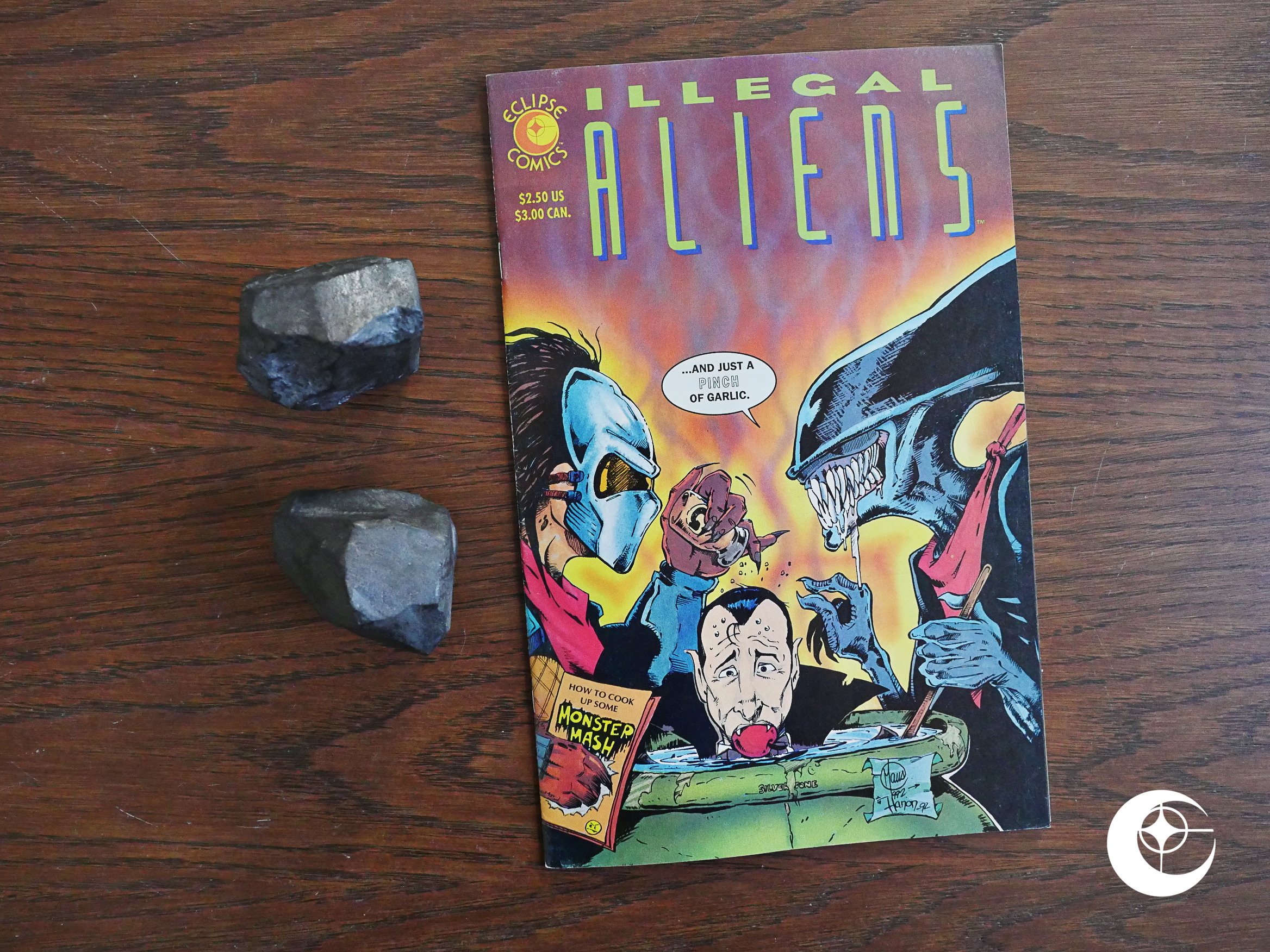

Loco vs. Pulverine (1992) #1 Illegal Aliens (1992) #1

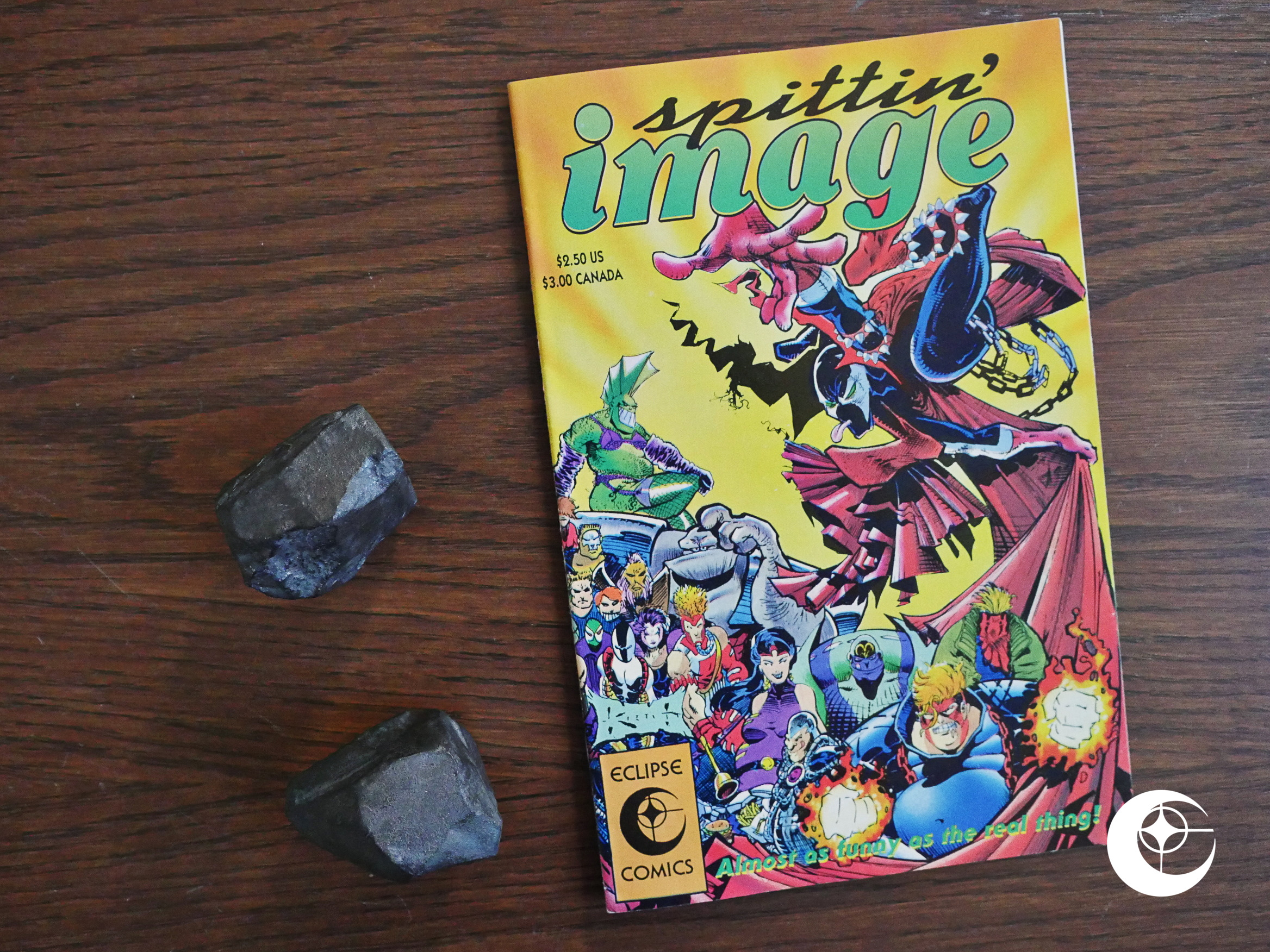

Illegal Aliens (1992) #1 Spittin’ Image (1992) #1

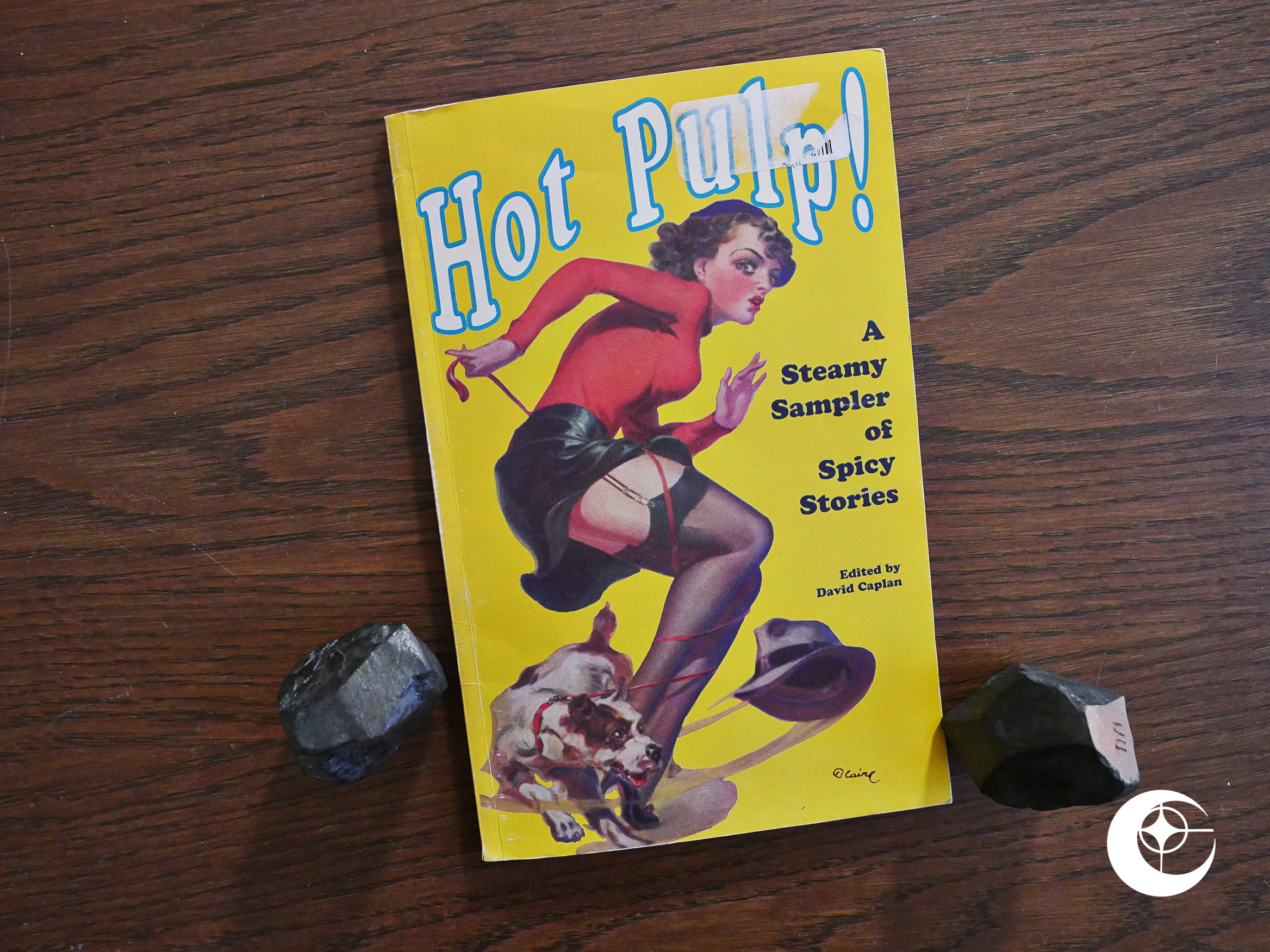

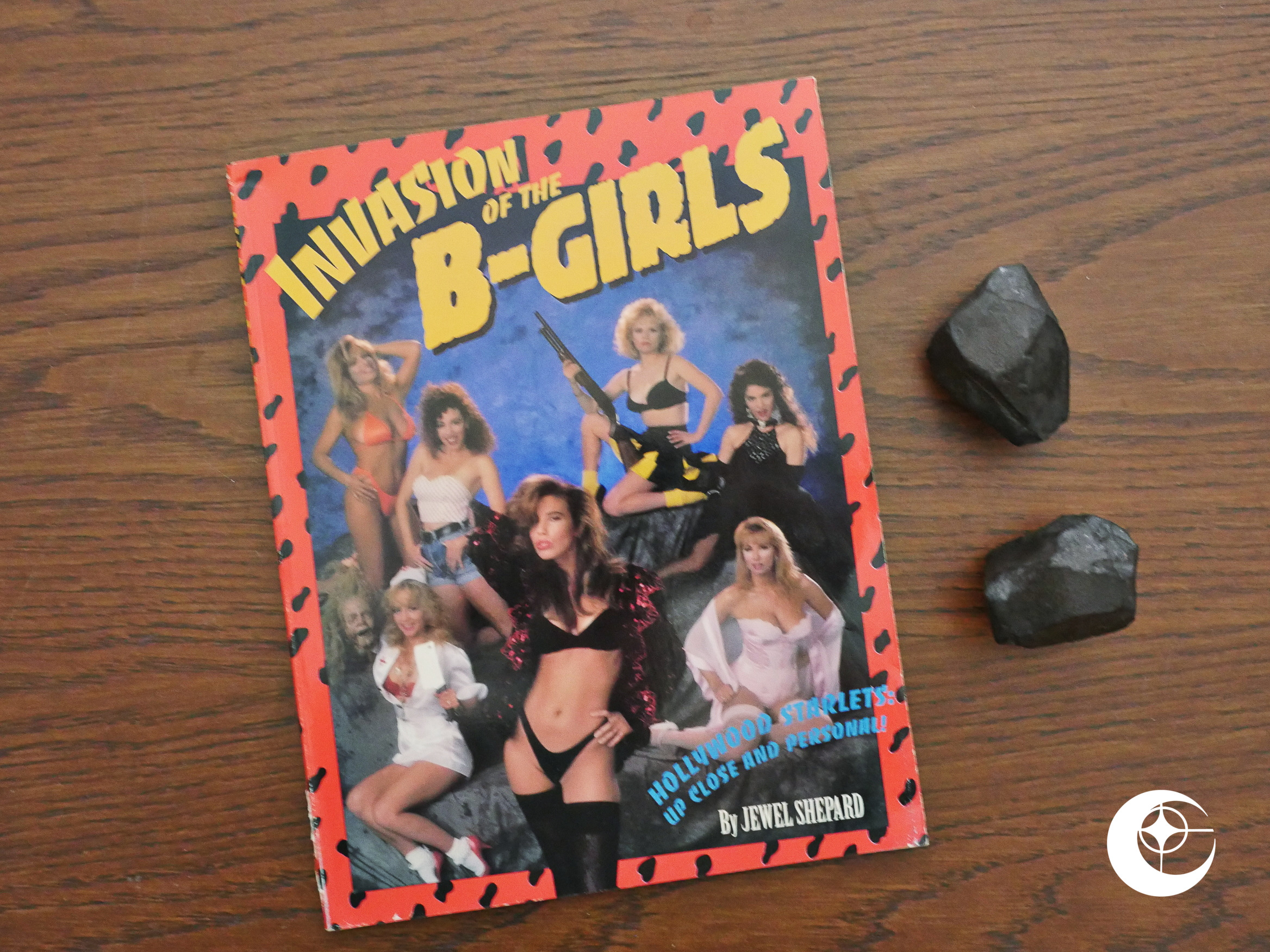

Spittin’ Image (1992) #1 Invasion of the B-Girls (1992)

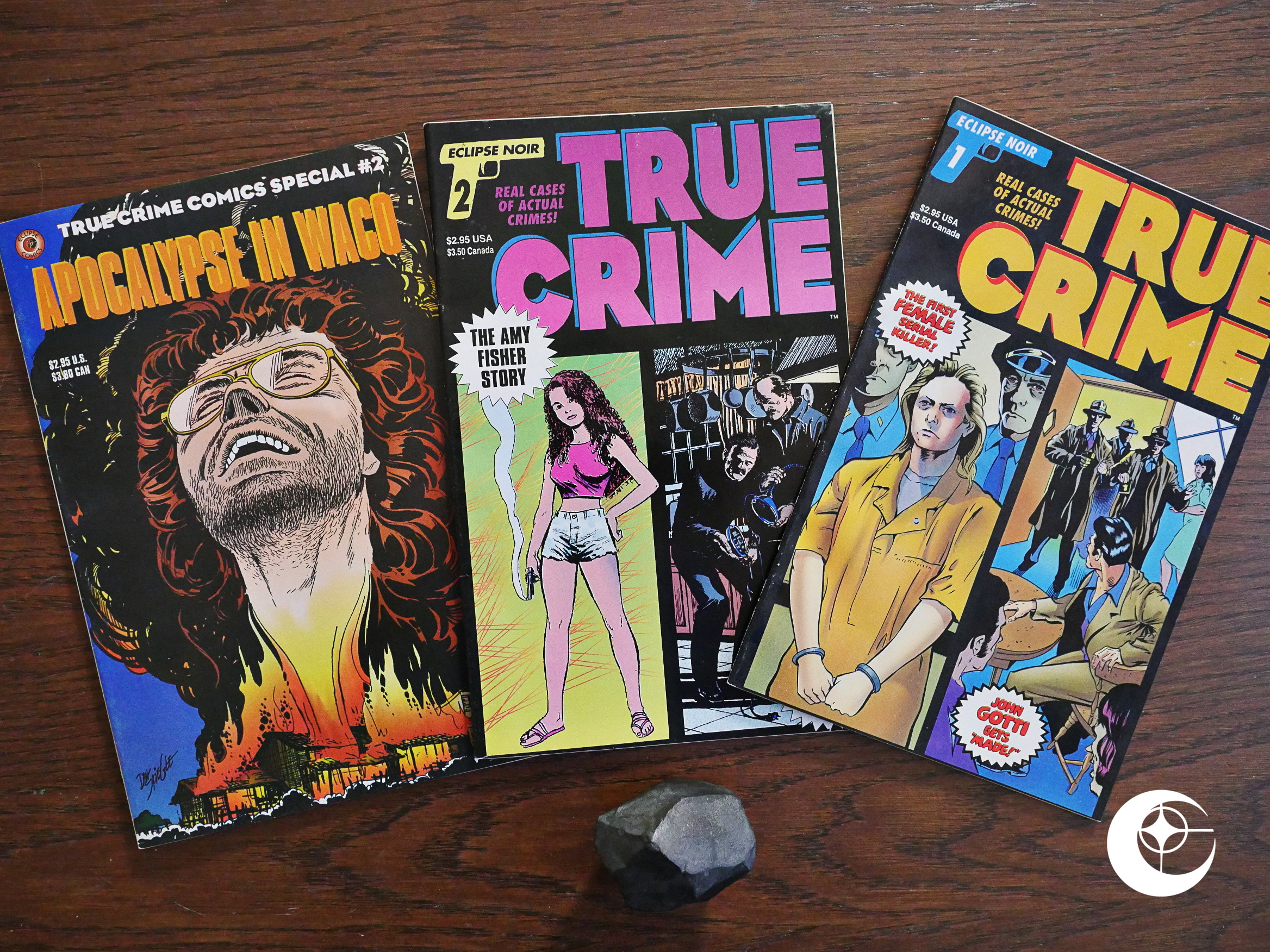

Invasion of the B-Girls (1992) True Crime Comics (1993) #1-2

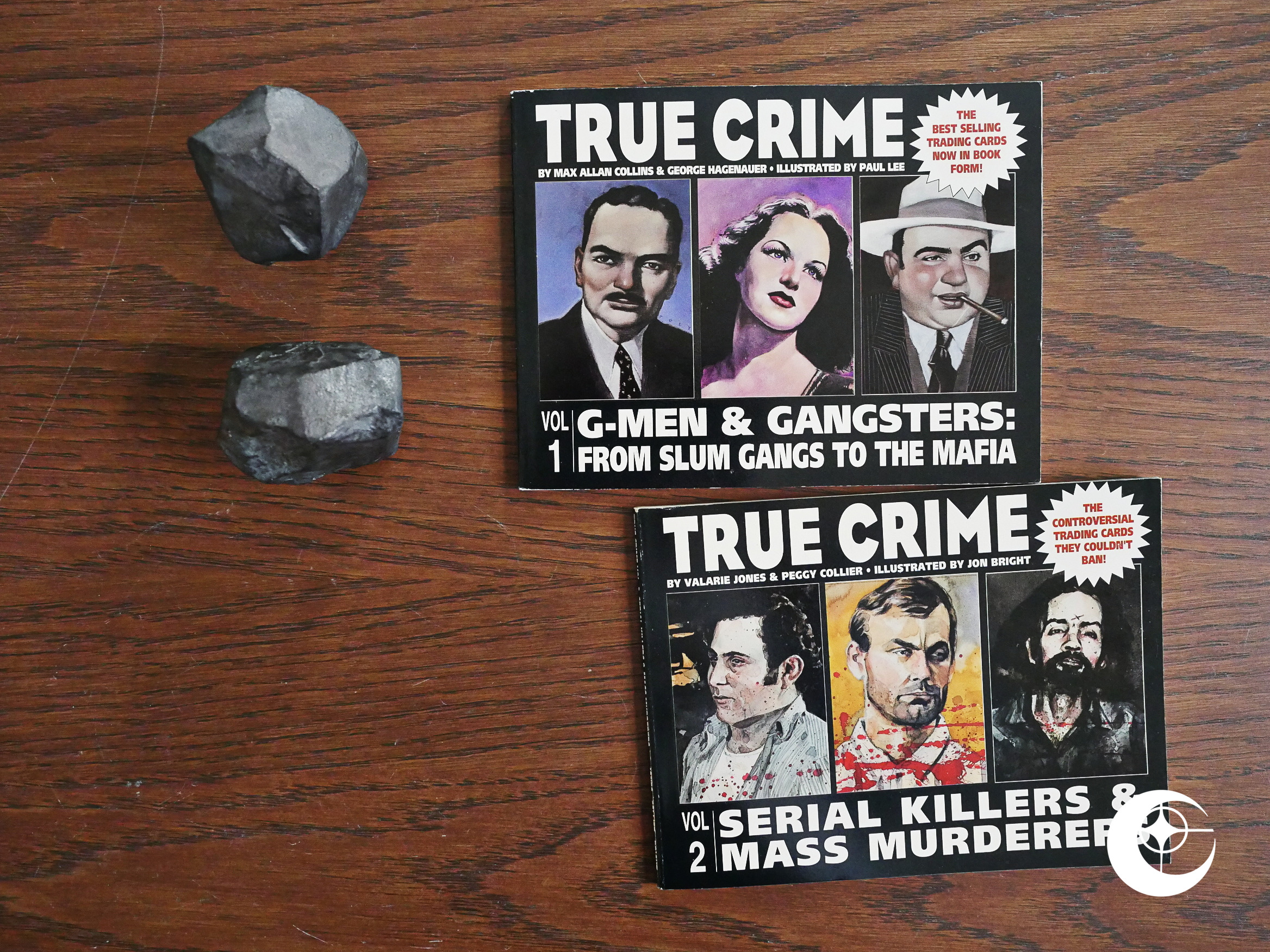

True Crime Comics (1993) #1-2 True Crime (1993) #1-2

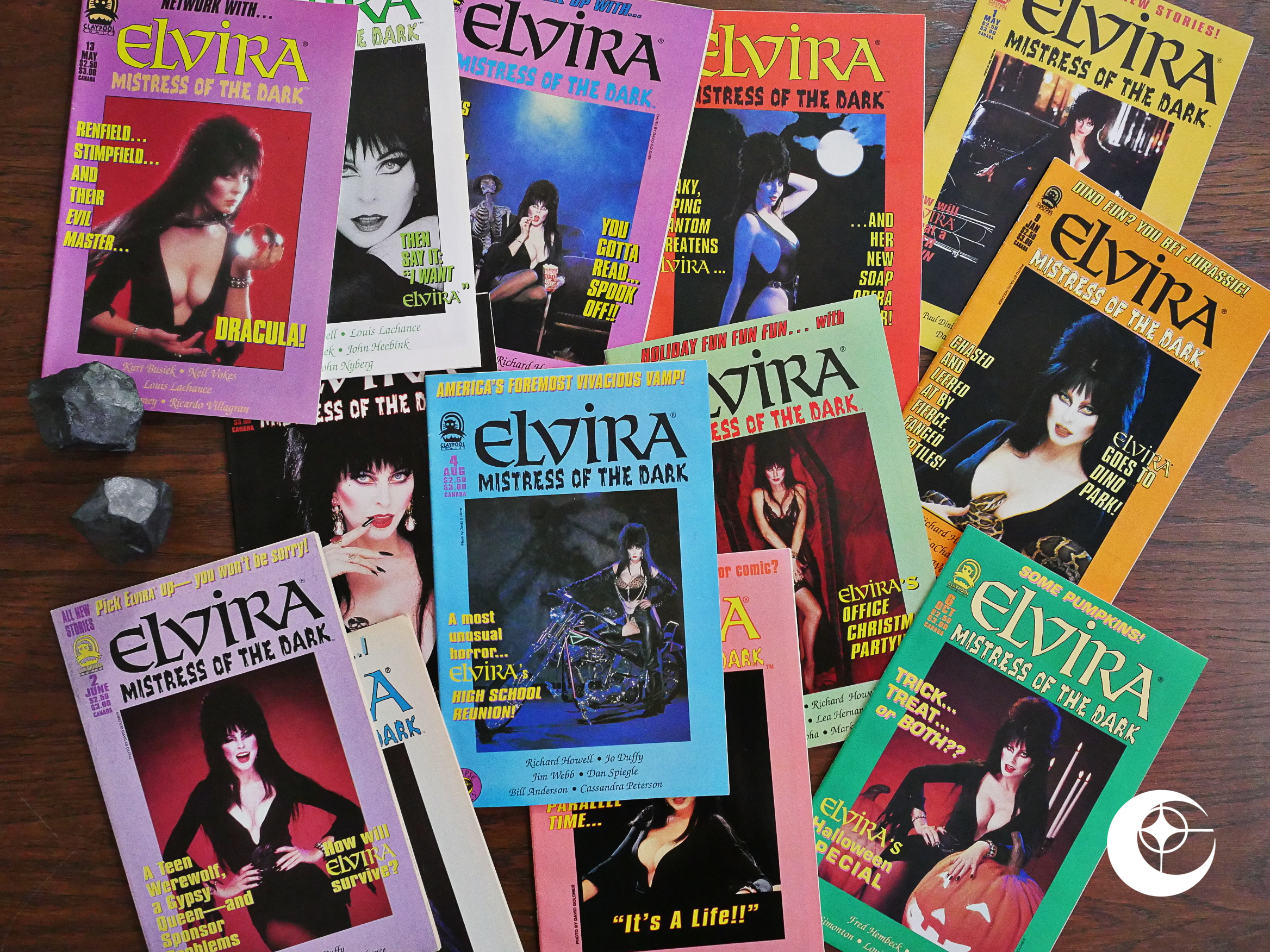

True Crime (1993) #1-2 Elvira, Mistress of the Dark (1993) #1-11

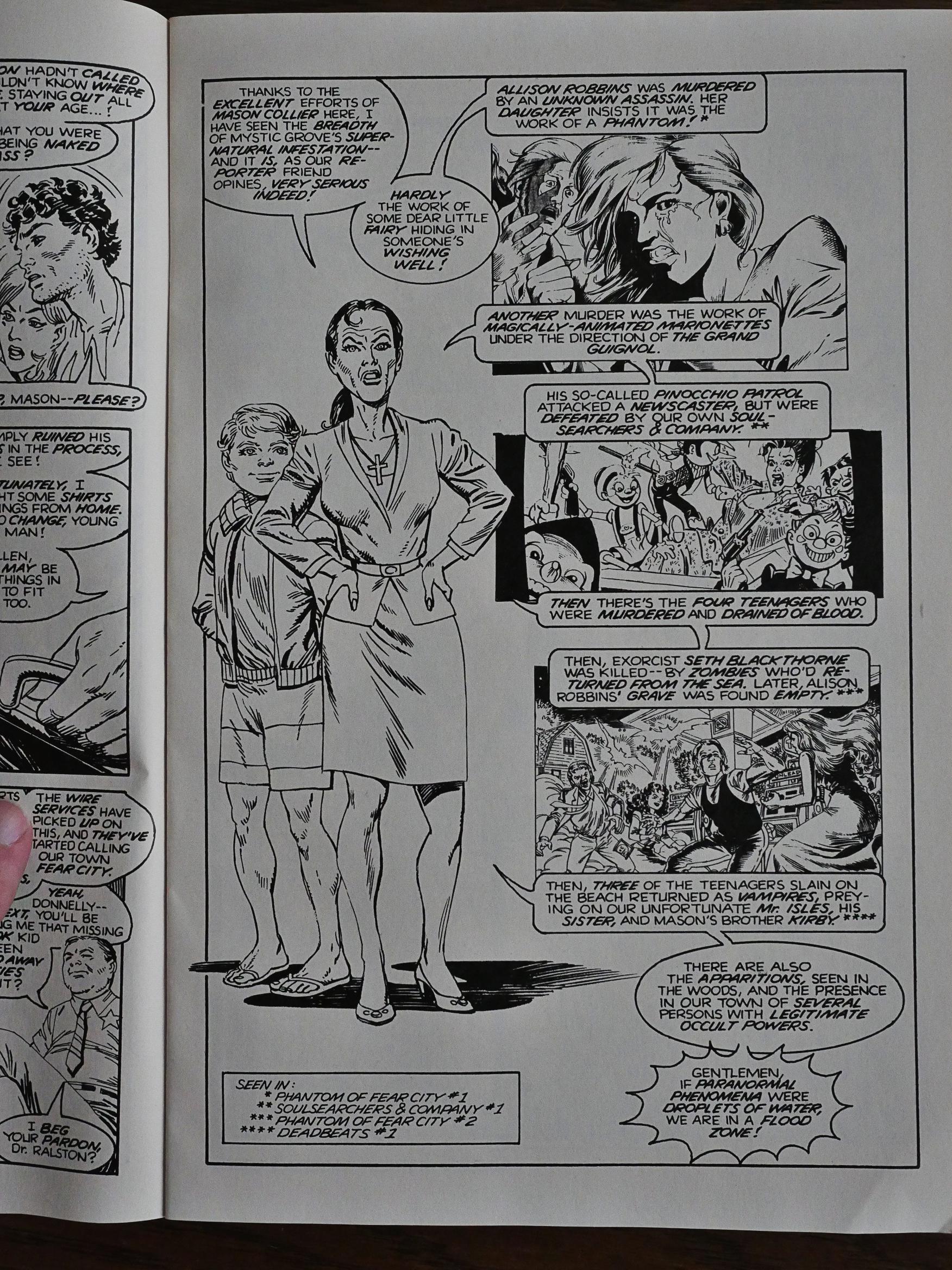

Elvira, Mistress of the Dark (1993) #1-11 Phantom of Fear City (1993) #1-6

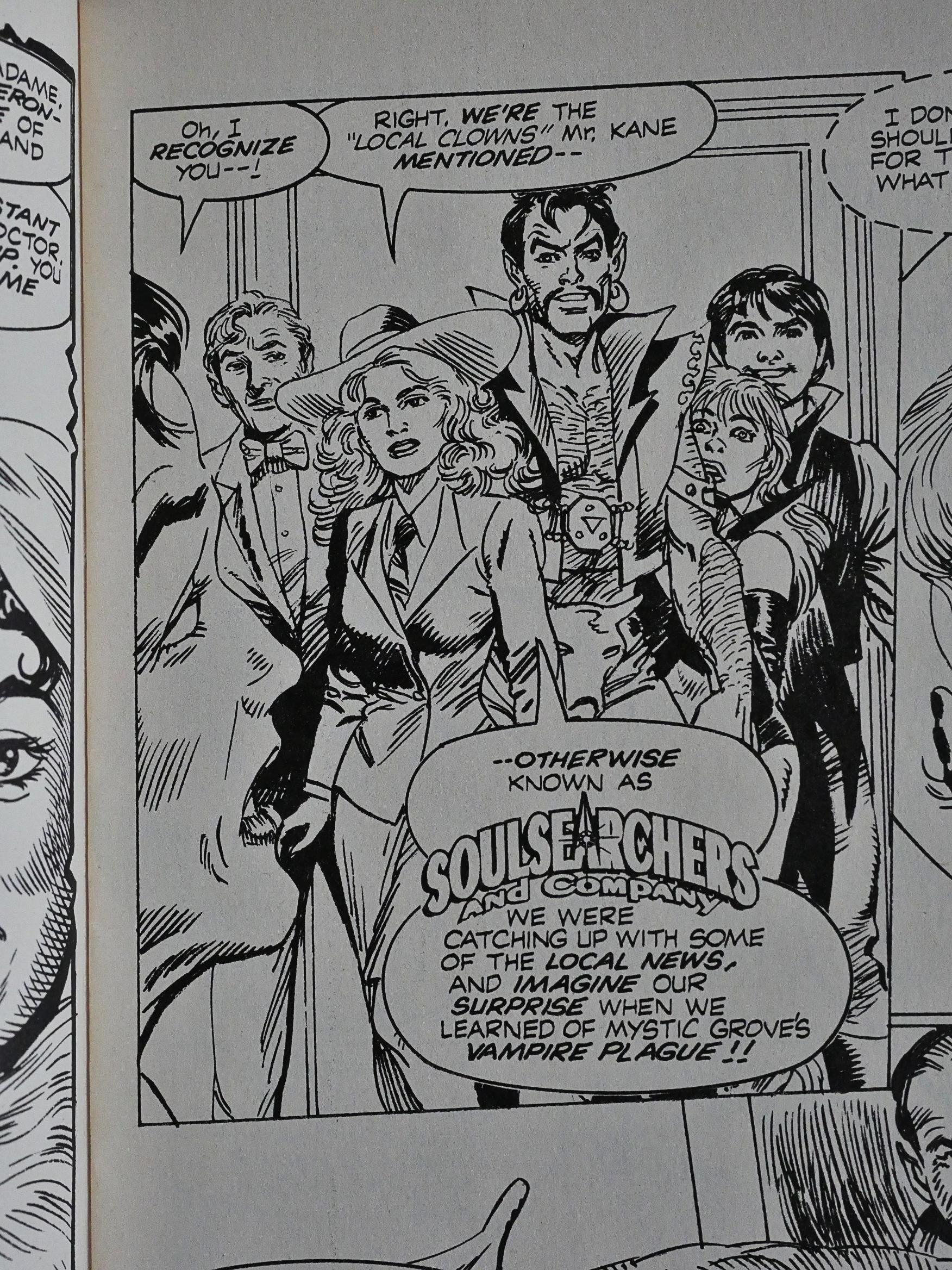

Phantom of Fear City (1993) #1-6 Soulsearchers and Company (1993) #1-6

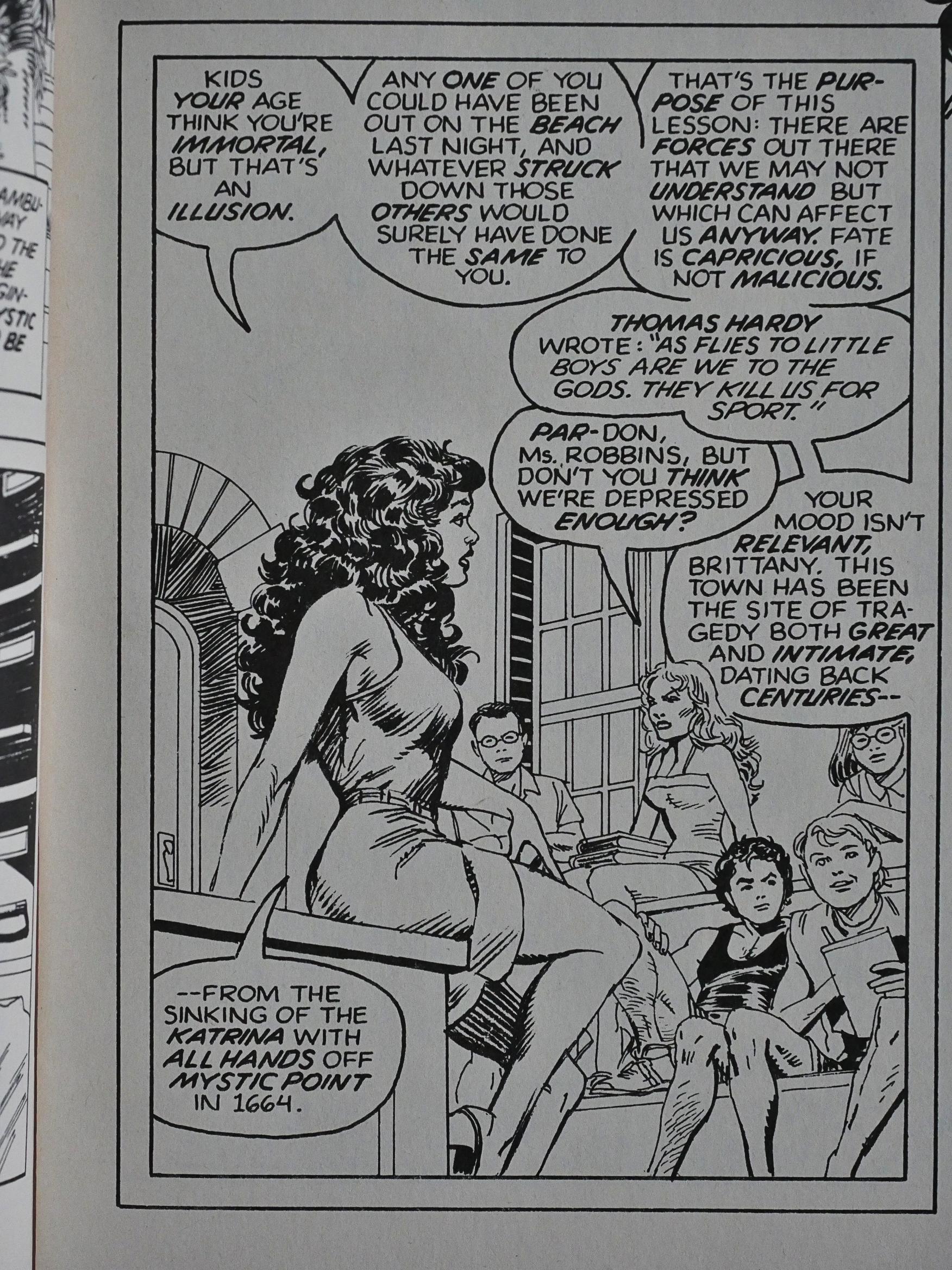

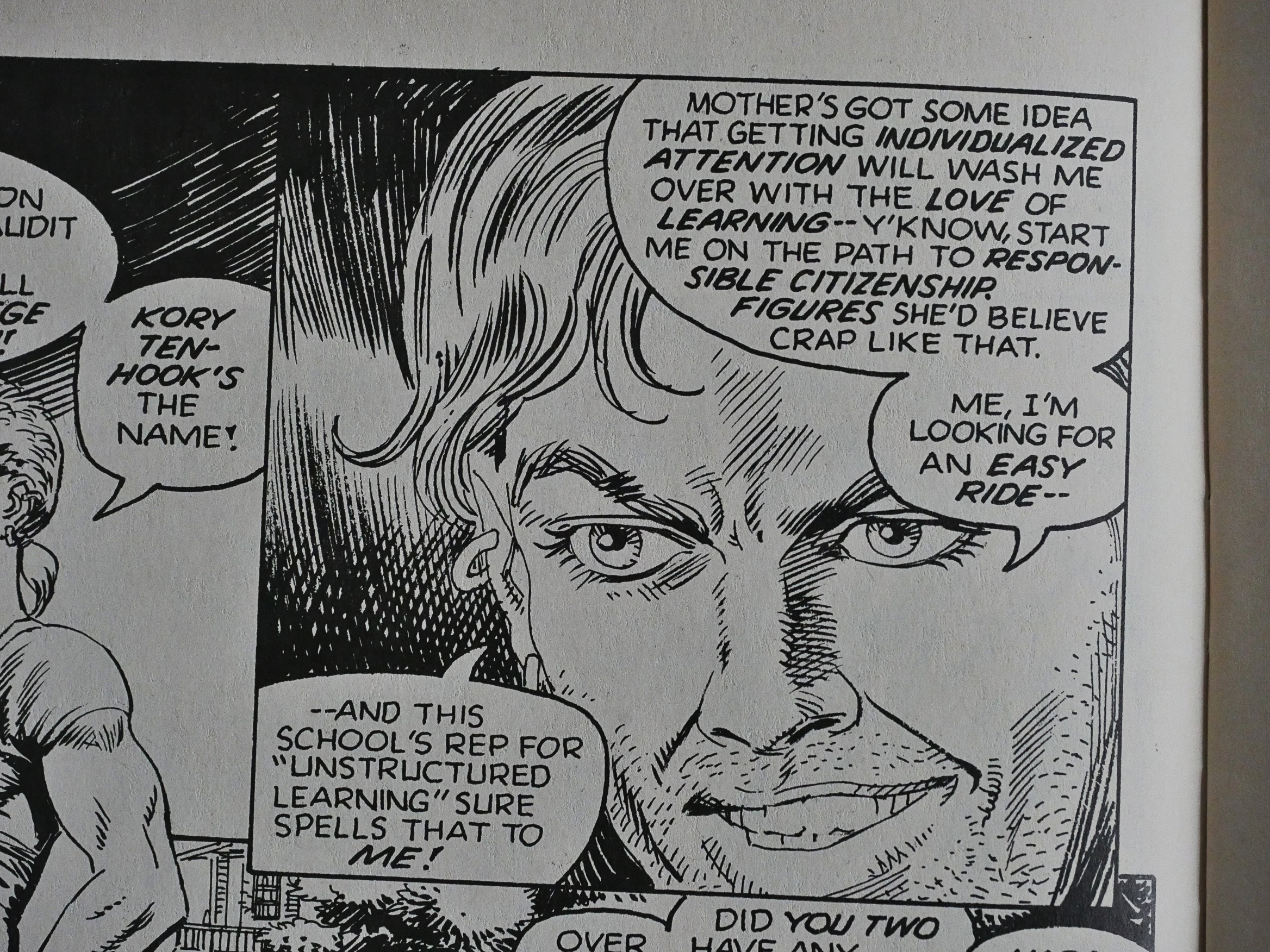

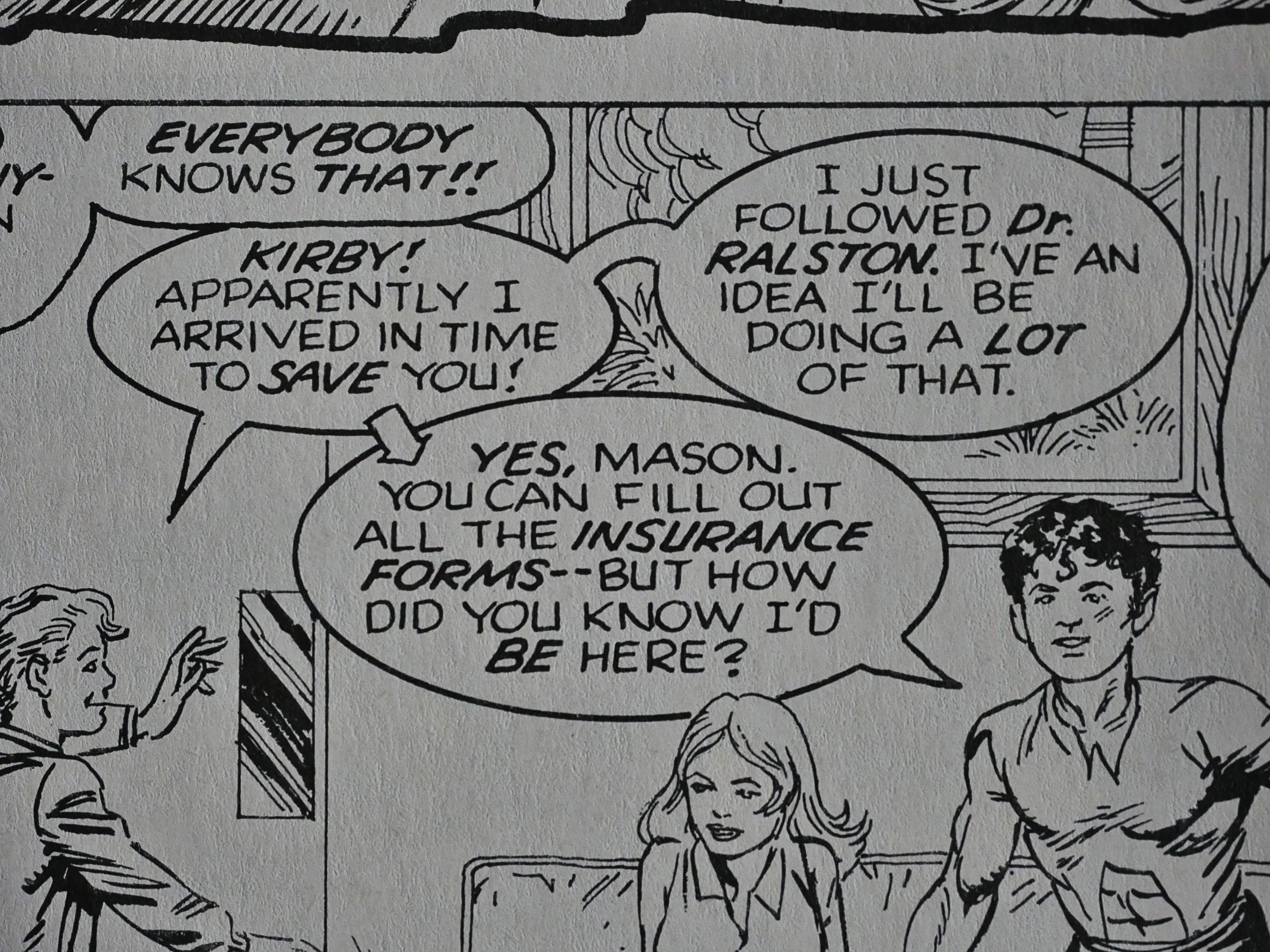

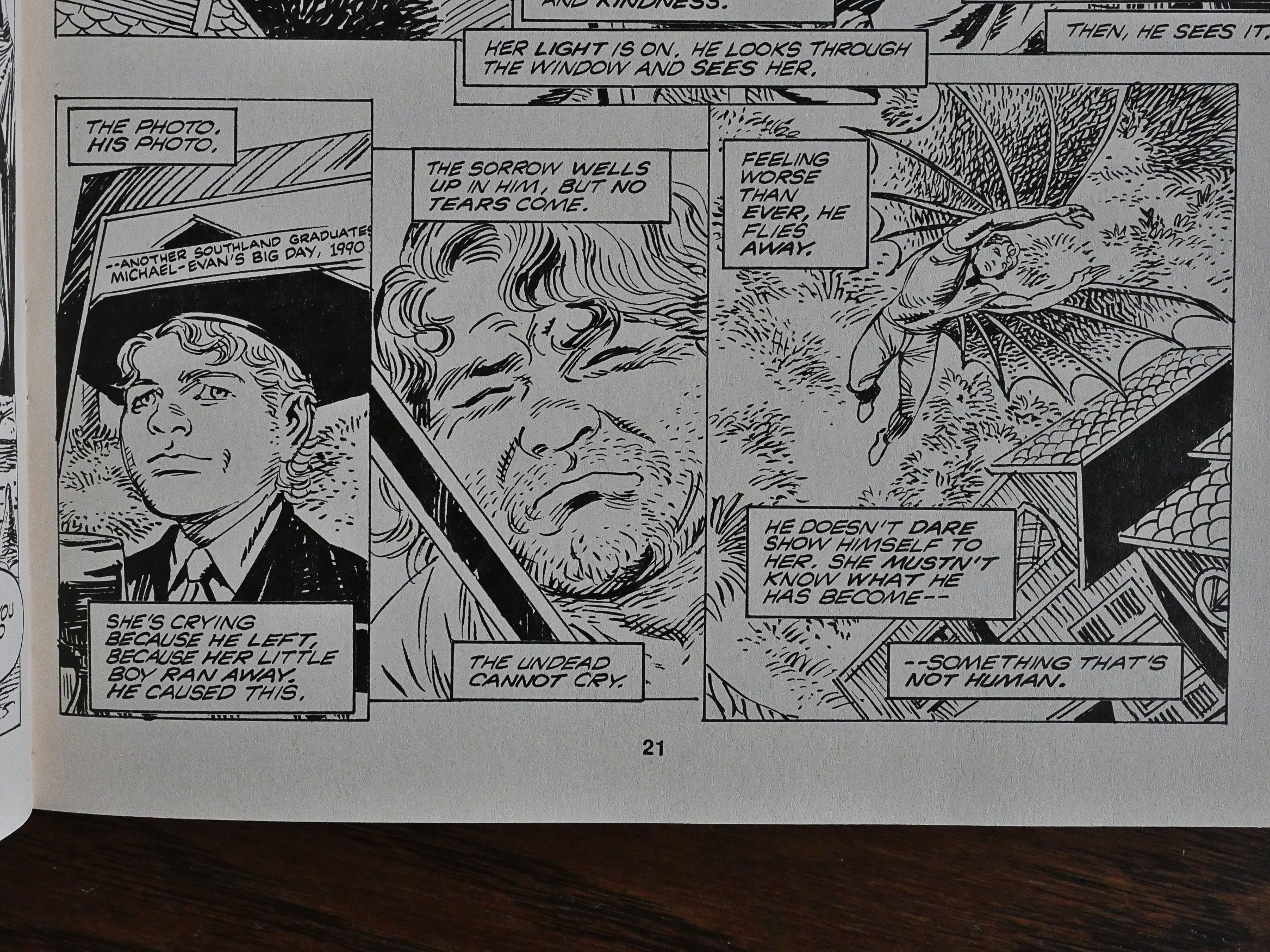

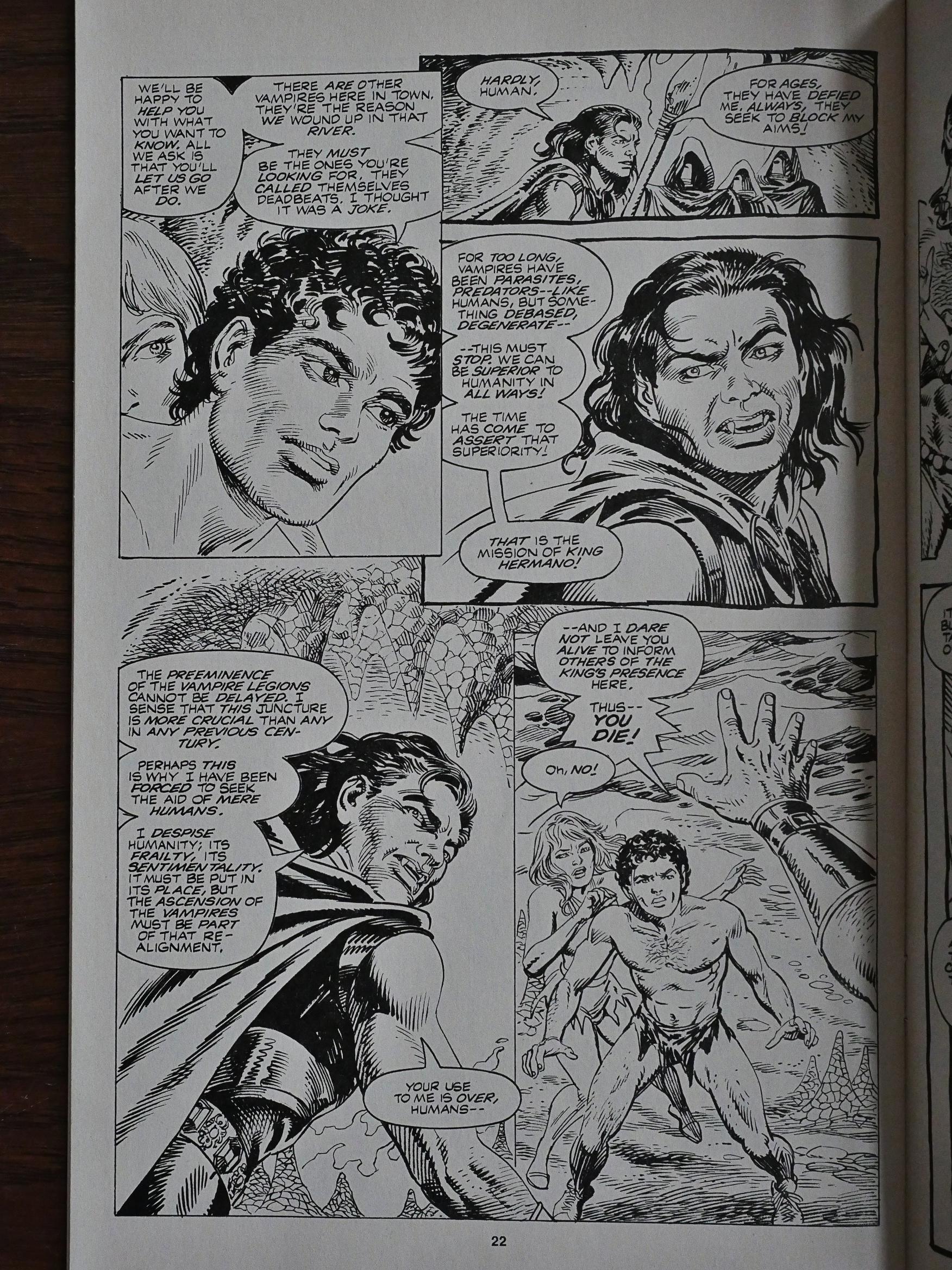

Soulsearchers and Company (1993) #1-6 Deadbeats (1993) #1-6

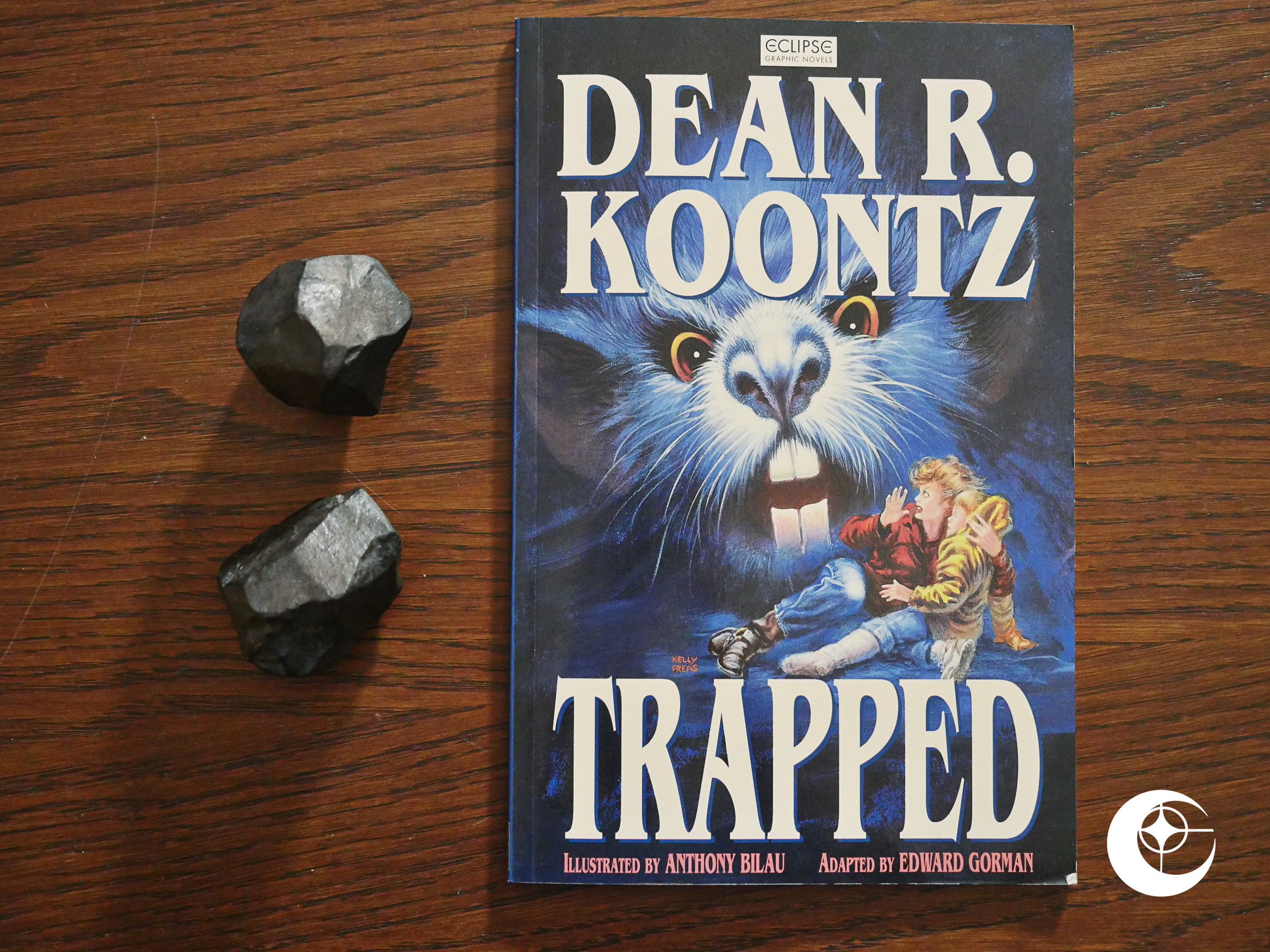

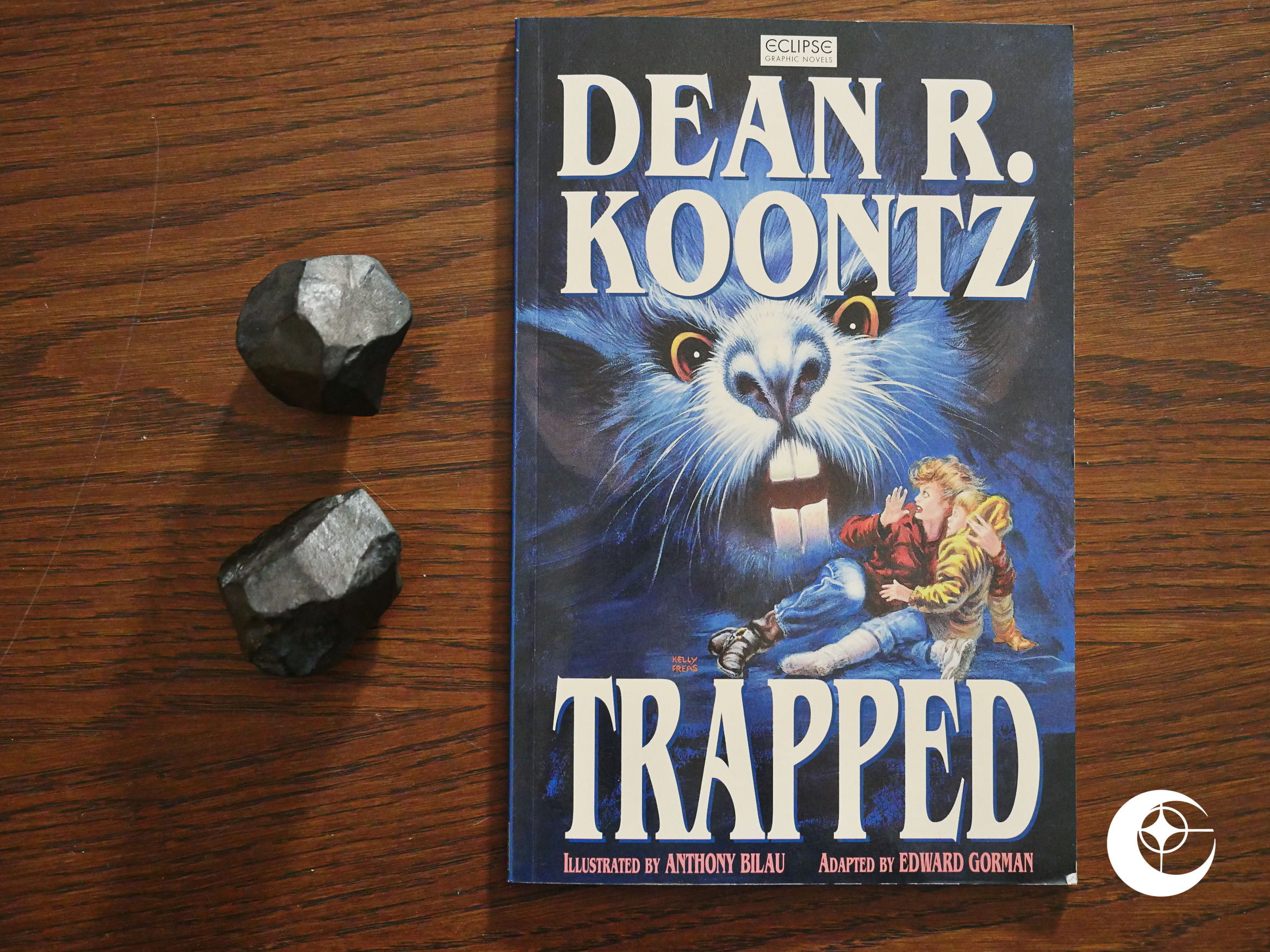

Deadbeats (1993) #1-6 Trapped (1993)

Trapped (1993) Rawhead Rex (1994)

Rawhead Rex (1994)