Son of Celluloid (1991), Revelations (1991), Dread (1992), The Yattering and Jack (1991), The Life of Death (1993) by Steve Niles and Fred Burke et al. adapted from short stories by Clive Barker.

For a few years, it seemed like Eclipse Comics was subsisting on publishing Barker-related books. There were sketchbook collections (called things like “Illustrator”), a thick fanzine (called “Pandemonium”), a portfolio, but most importantly, Tapping the Vein, which over five issues adapted ten of Barker’s best short stories from Books of Blood.

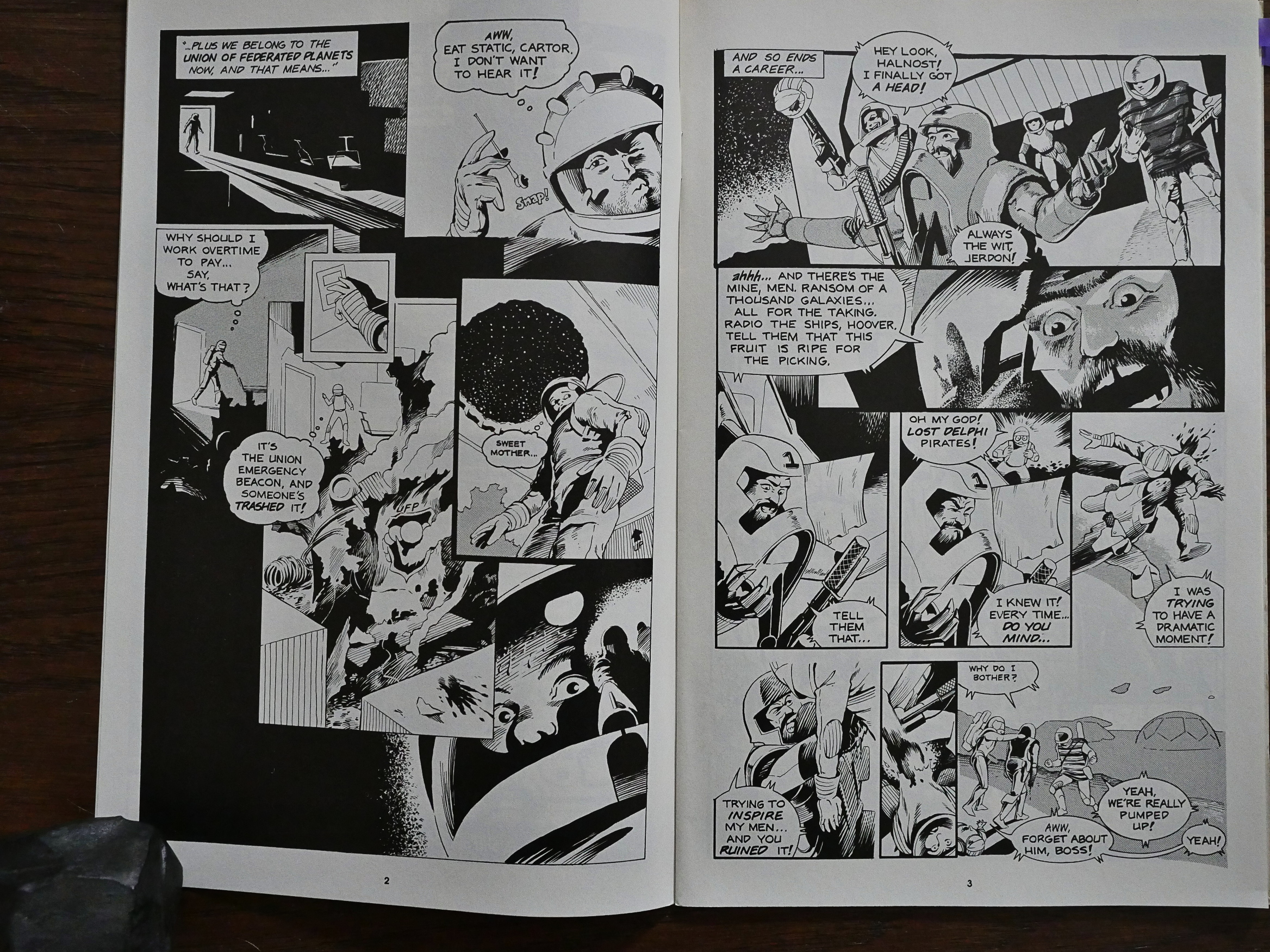

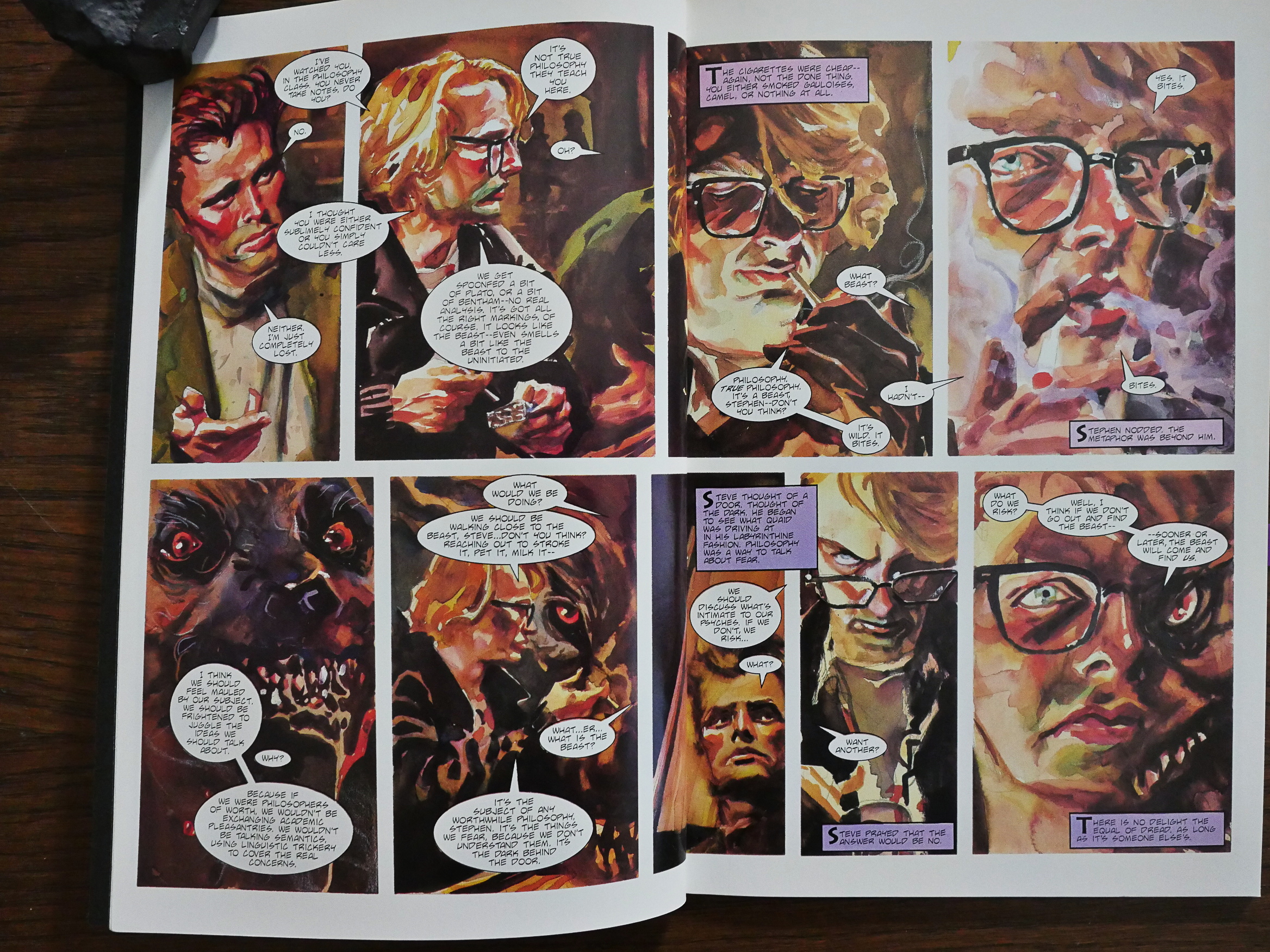

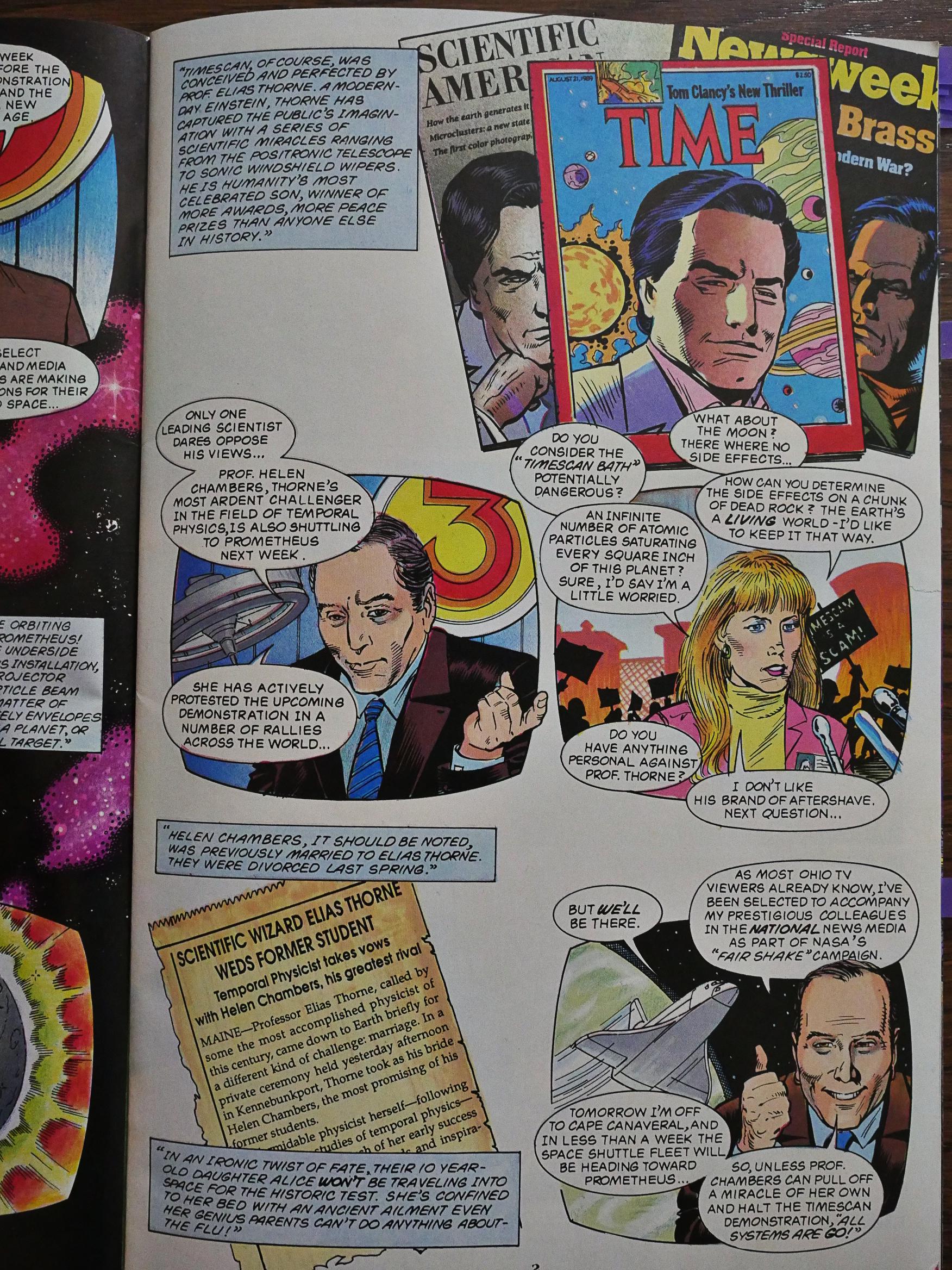

The adaptations were mostly pretty good reads, but they suffered from adhering to a 24 page format, and since The Eclipse Way of adapting literary works is to cram as much of the original text into comics form, it meant that many of the adaptations were very leaden and laden with captions.

So Eclipse did the logical thing and created a series of books that would do the adaptations in however many pages it took. We got six books with adaptations 48 to 60 pages long. But did it help? Let’s have a look.

This is the only hardback edition of these books that I have, so let’s just take an even nerdier peek at how it looks. It’s got a kinda stylish front cover, with metallic embossed lettering…

… and a mood-setting … er… I’m sure these paper pages (that binds the innards to the cover) has a printerey name, but it escapes me at the moment.

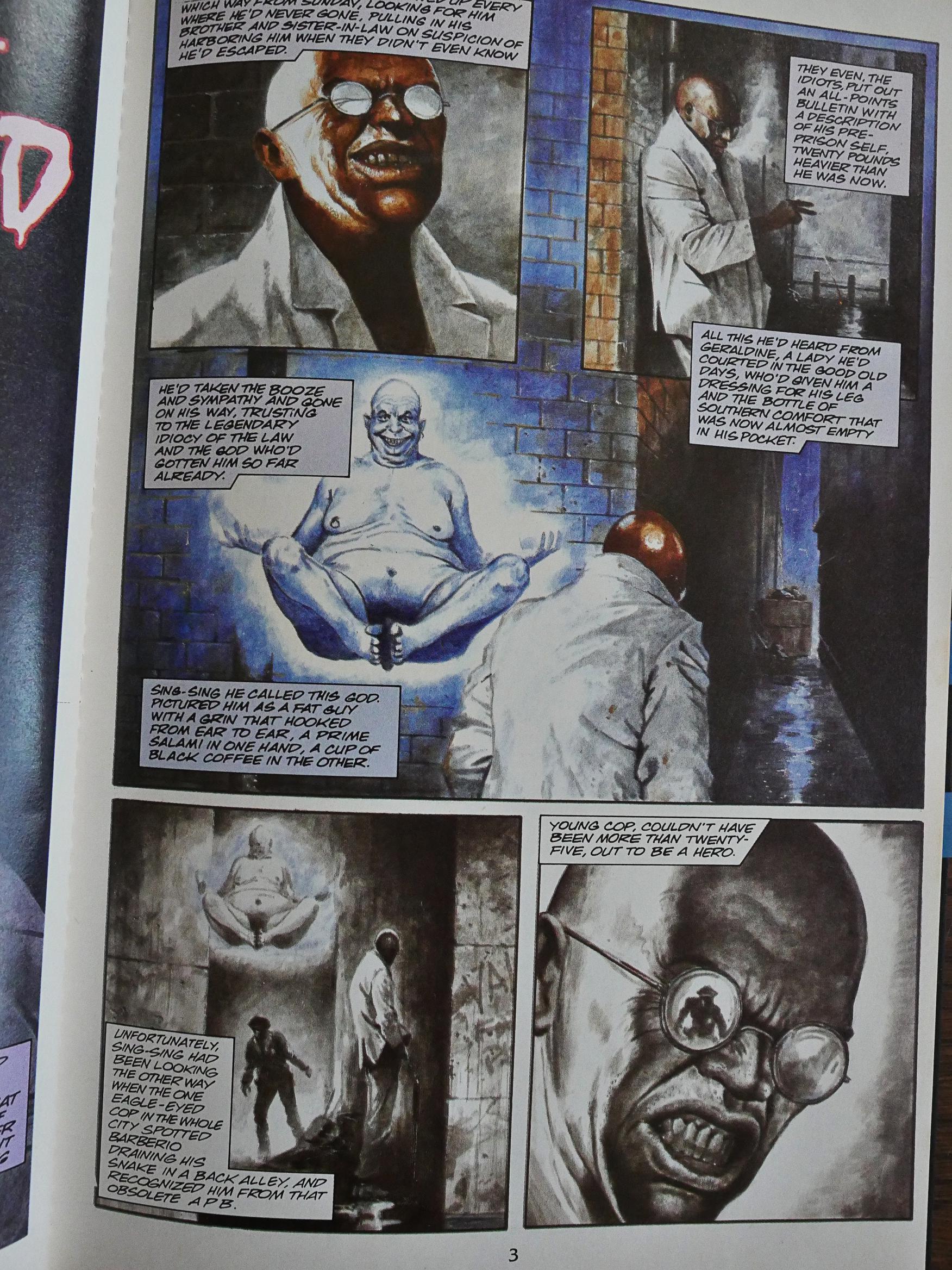

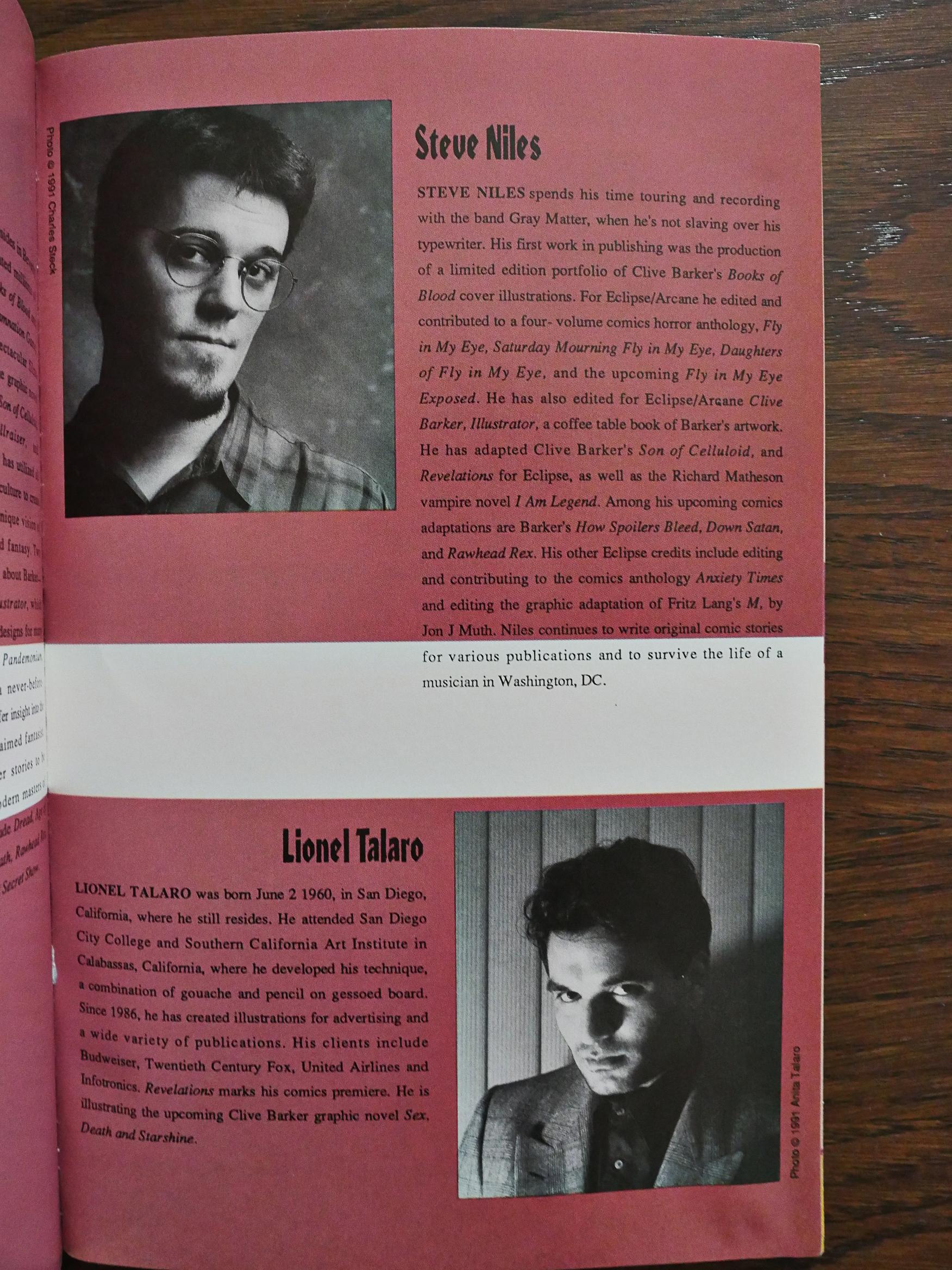

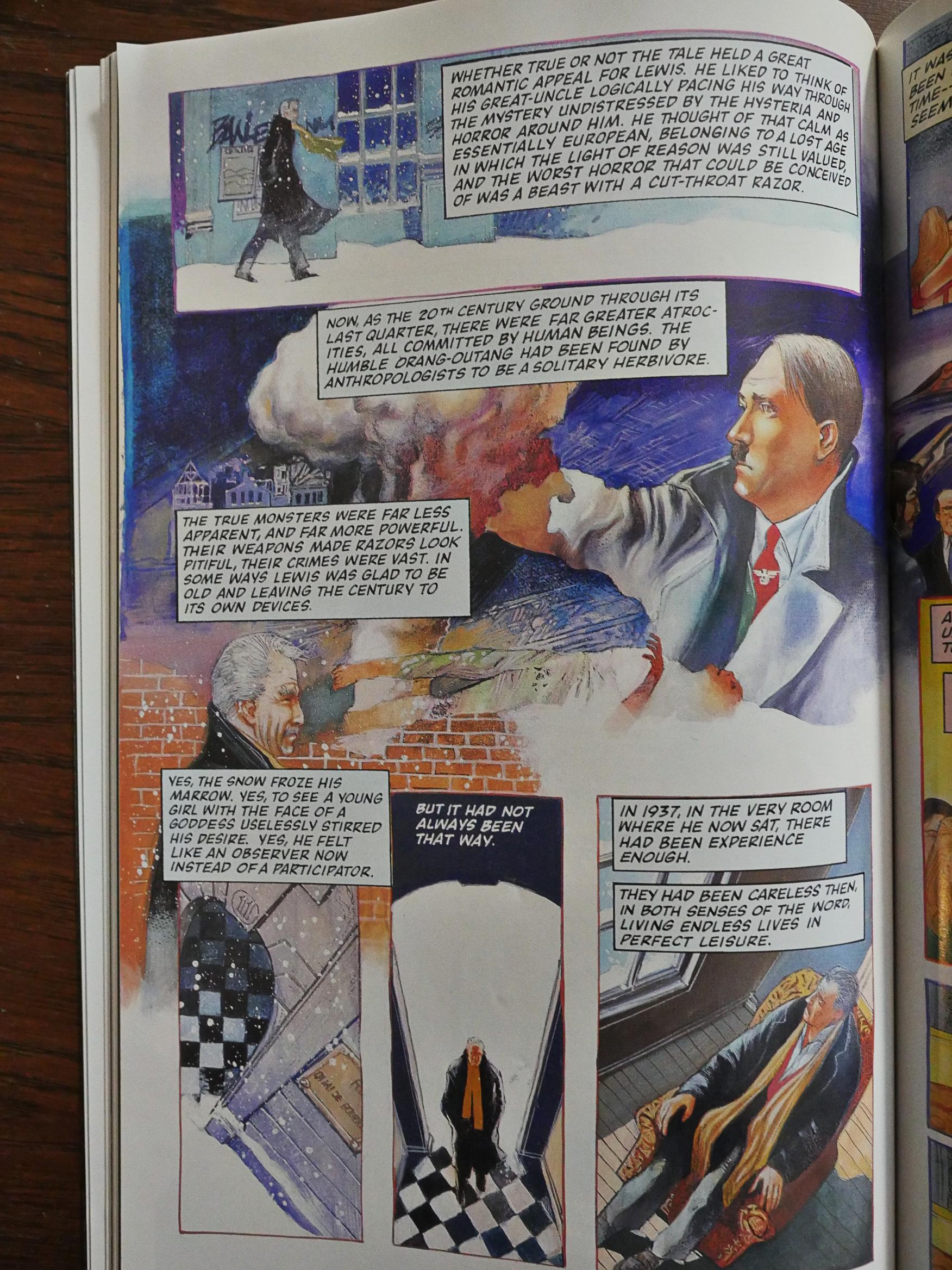

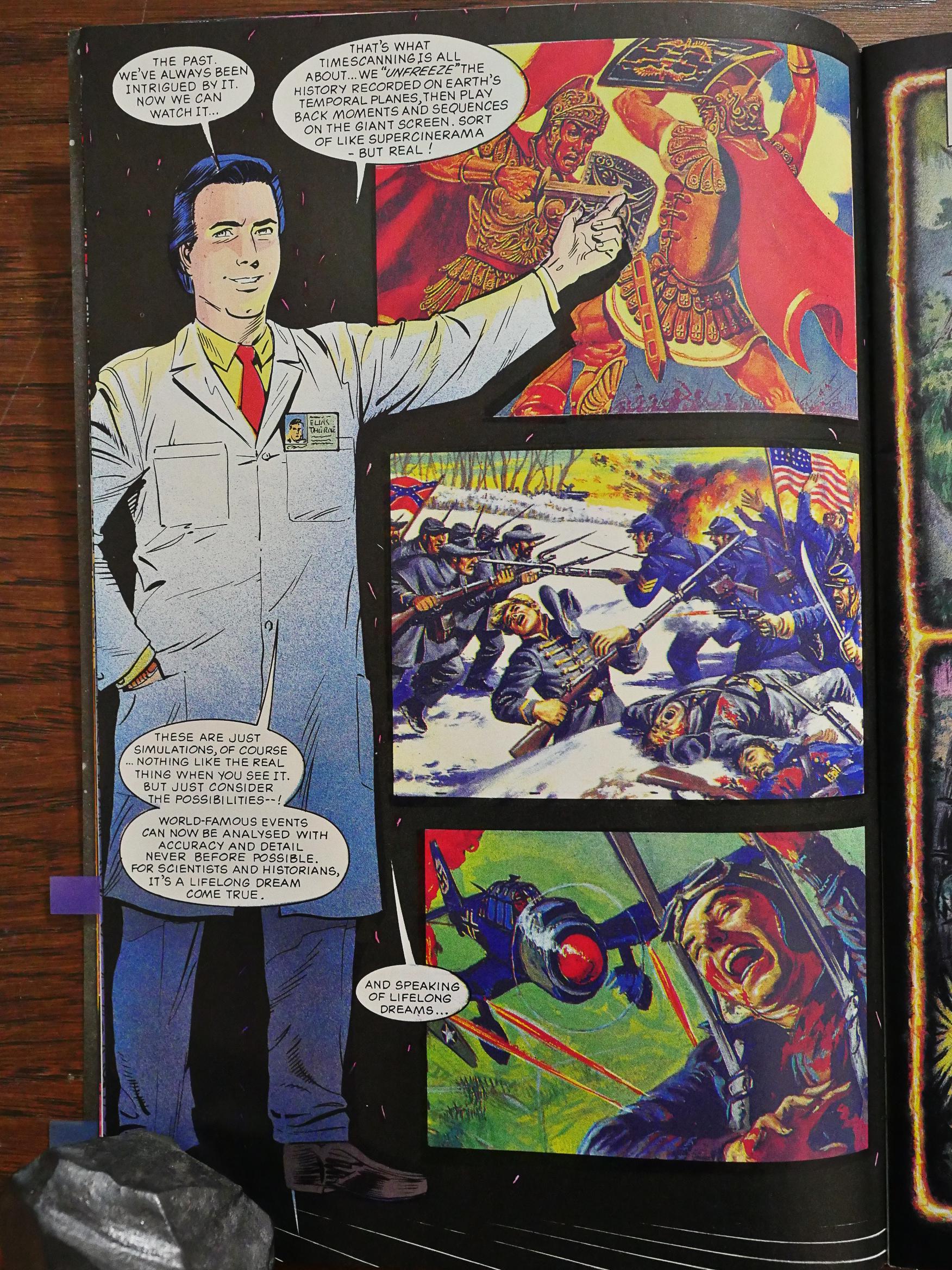

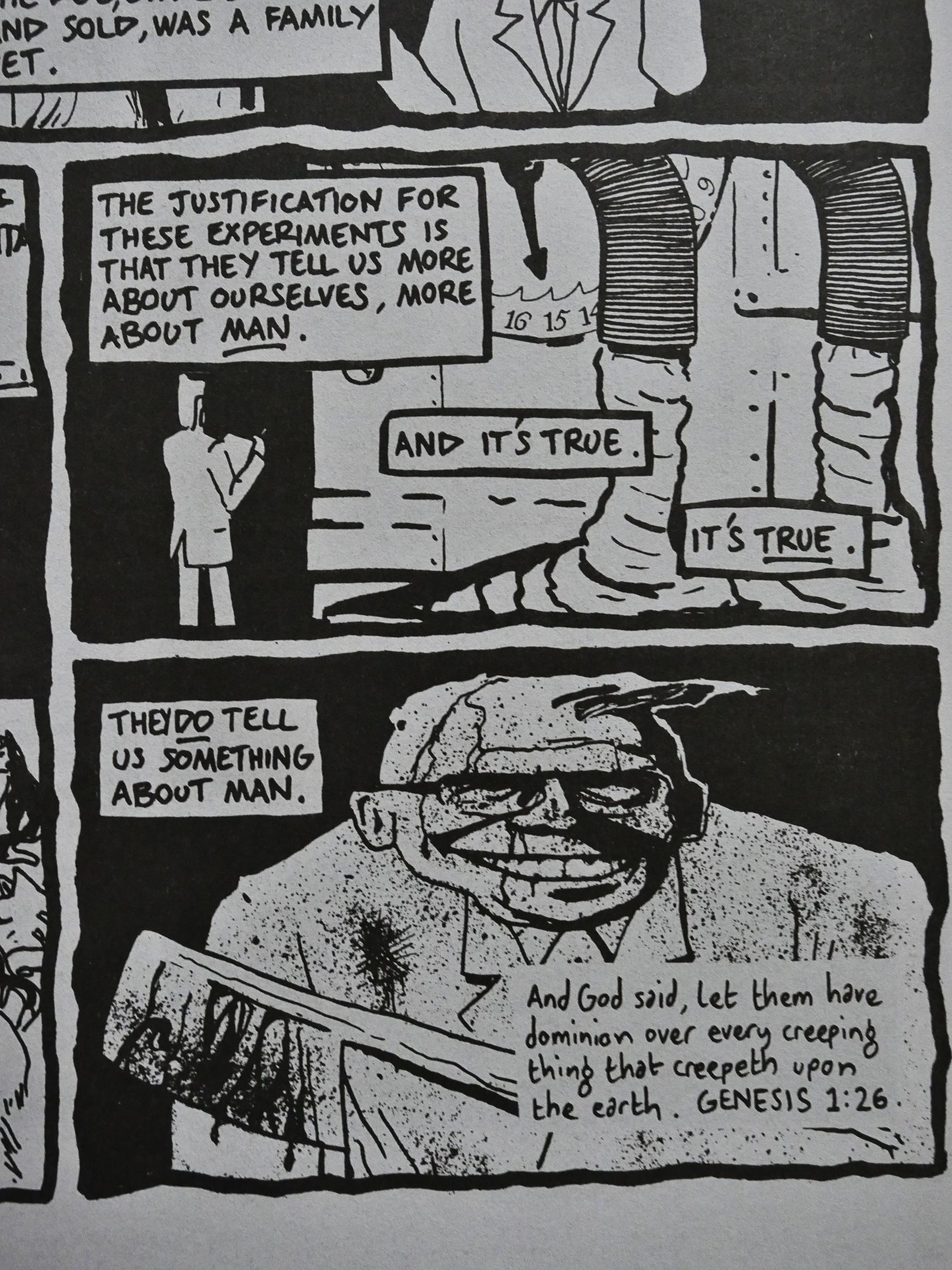

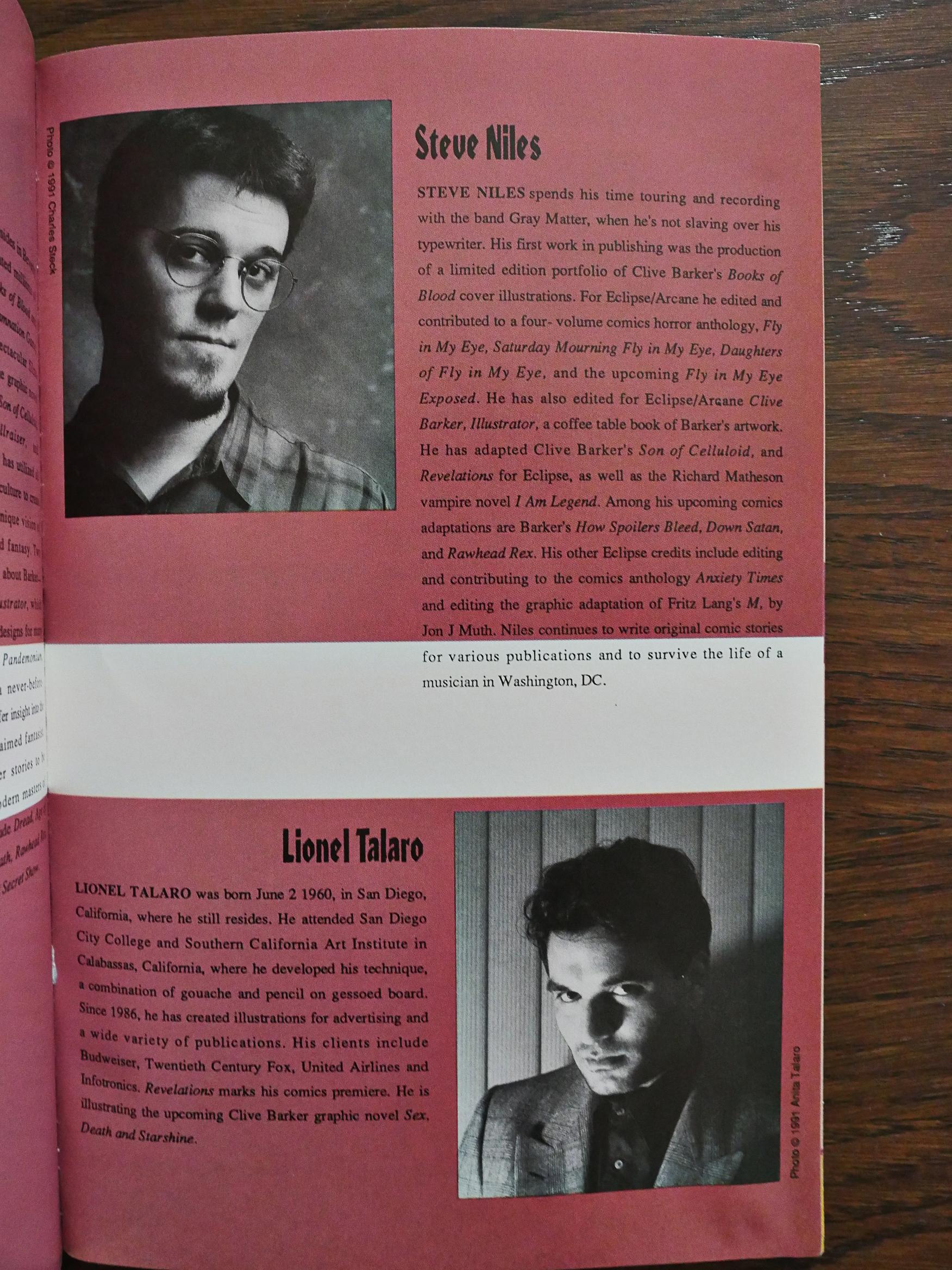

Anyway, Steve Niles does the adaptation, once again, and Les Edwards, who’d primarily been a cover illustrator before, does the artwork. As usual in these Barker adaptations, we’re neck deep in purple prose. Eclipse’s approach is apparently to try to cram as many of the original words in as possible. I guess that keeps Barker happy? Few writers like having their words cut.

And, as usual, that means that the artwork shows pretty much what the words describe… except for the odd glitch or two, where the captions describe that god as having a salami in one hand and a cup of coffee in the other. And the artwork clearly shows that that’s not the case.

For a newcomer to comics, Edwards does a pretty good job. The book’s very readable.

But these aren’t exactly good comics.

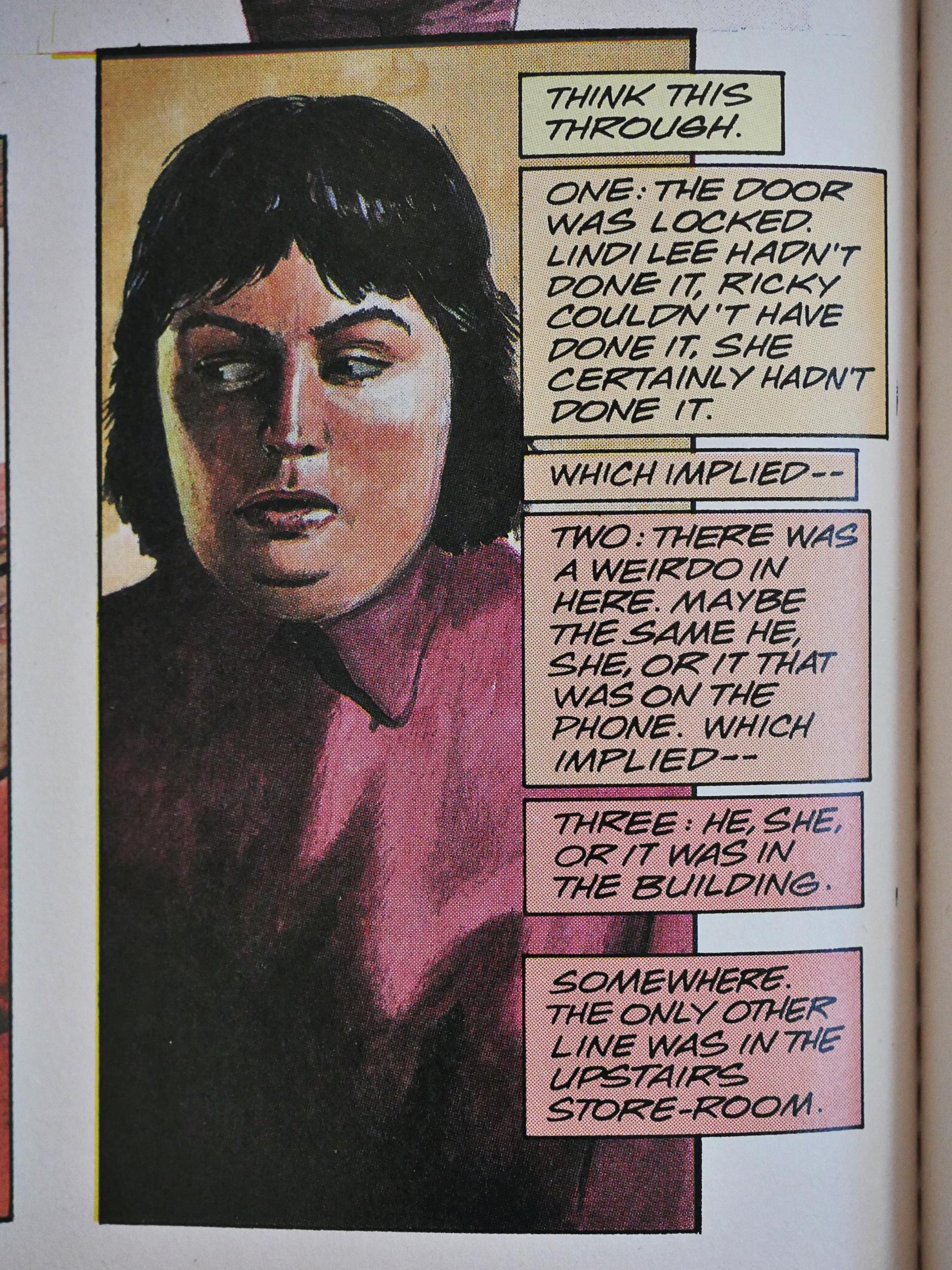

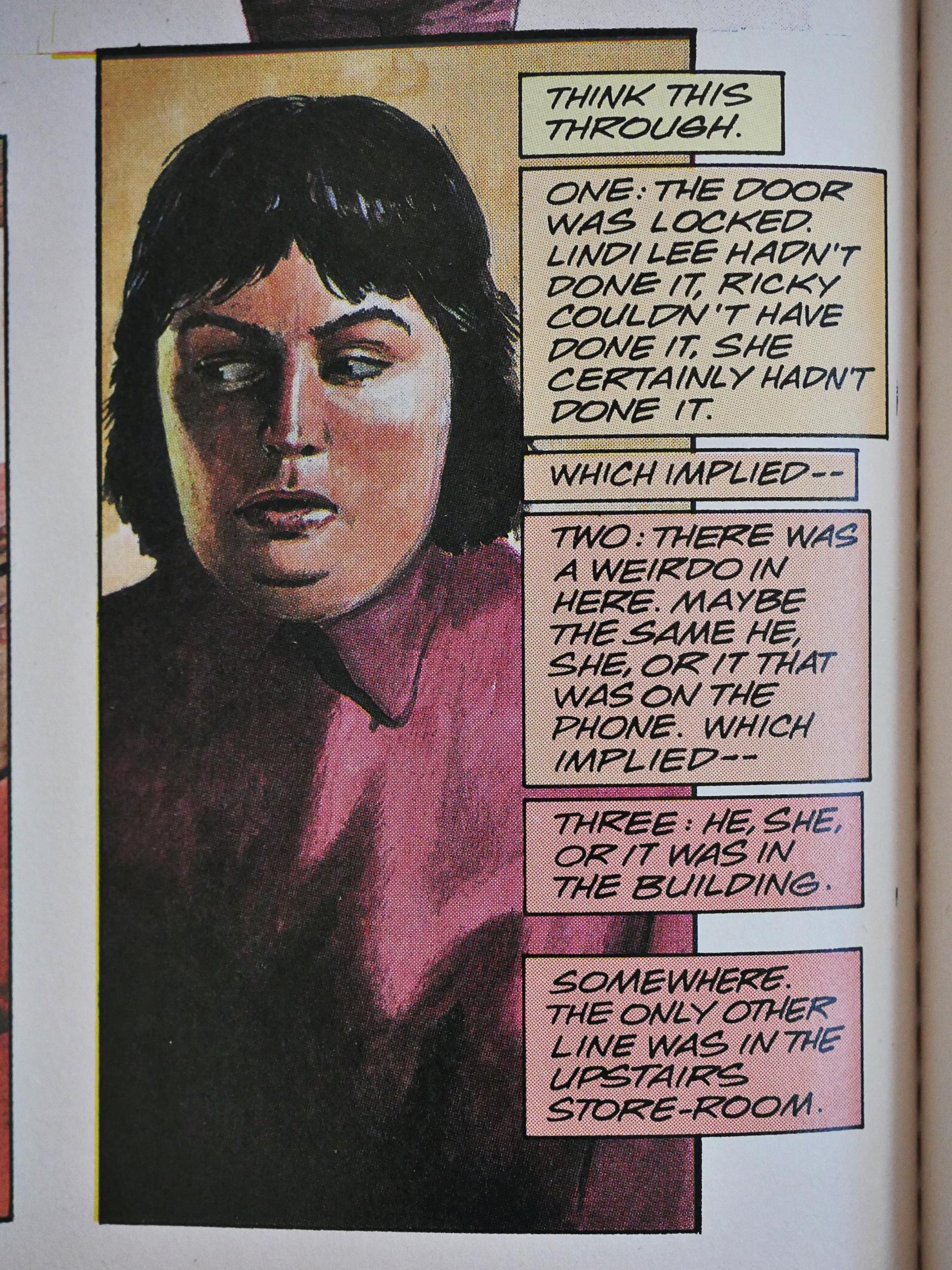

It’s still an entertaining read, because Barker is (once again) ahead of the horror writing pack by putting in a protagonist who’s aware of horror tropes, and thinks things through logically. This is something that horror movies would exploit (to great success) starting a decade later or so.

And unusually enough for a Barker story, the story has a happy ending (sort of). I mean, at least the protagonist doesn’t suffer a horrible death or anything, which is Barker’s go-to move.

She even goes on a diet, so that’s nice for her.

Oops! Spoilers!

The edition of The Yattering and Jack I have is the reprint from 1993. If I understand things correctly, this was originally published in a 64 page package in 1991. Eclipse then got a distribution/co-publishing deal with Harper Collins, and repackaged several (all?) of the Barker adaptations (and stuck a short Barker from Tapping the Vein into each as a backup). So you ended up with something that’s around 90 pages long: Anything shorter might perhaps fare less well in bookstores?

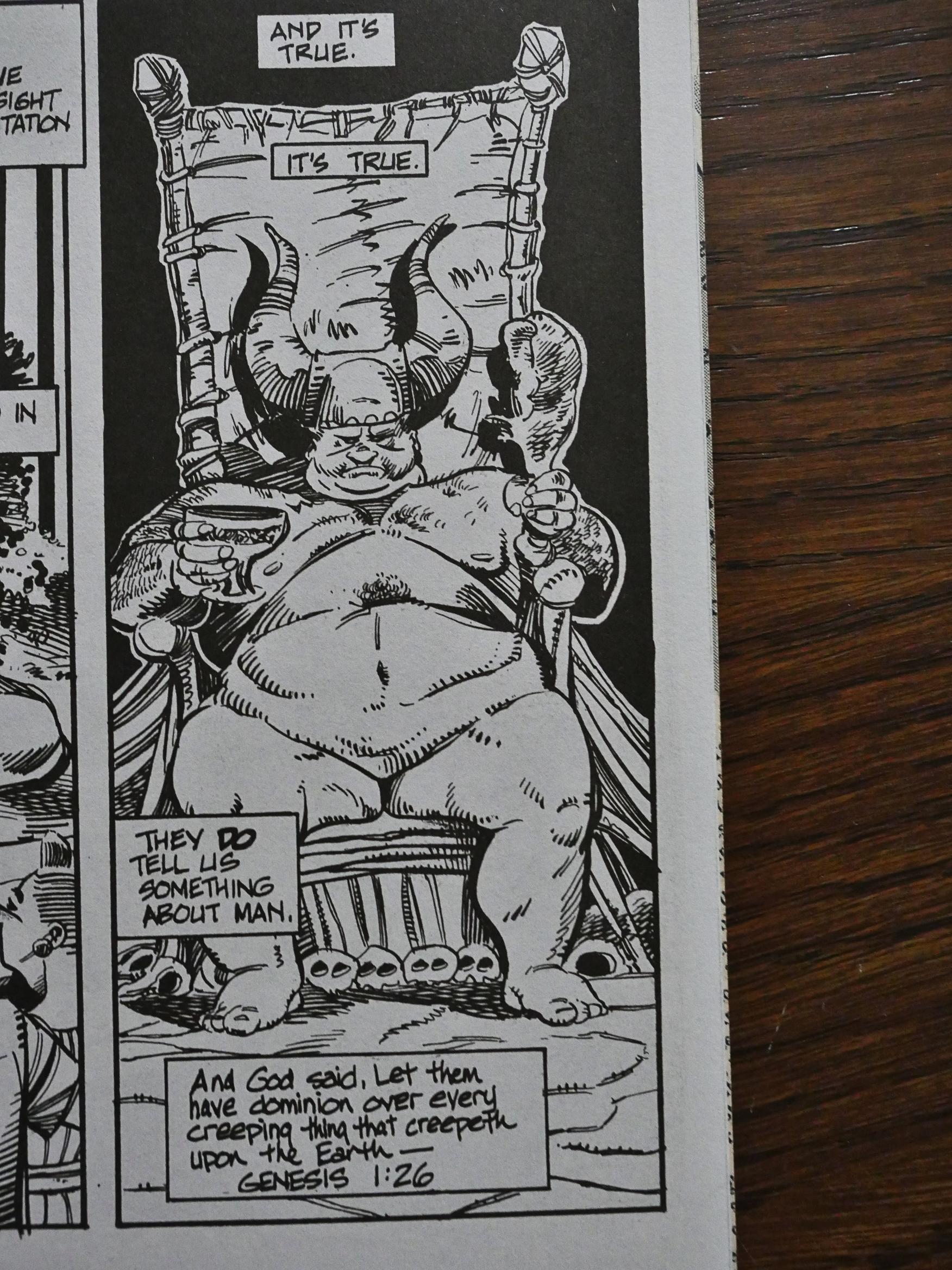

The artist on Yattering is John Bolton, and he’s clearly having a lot of fun with this material.

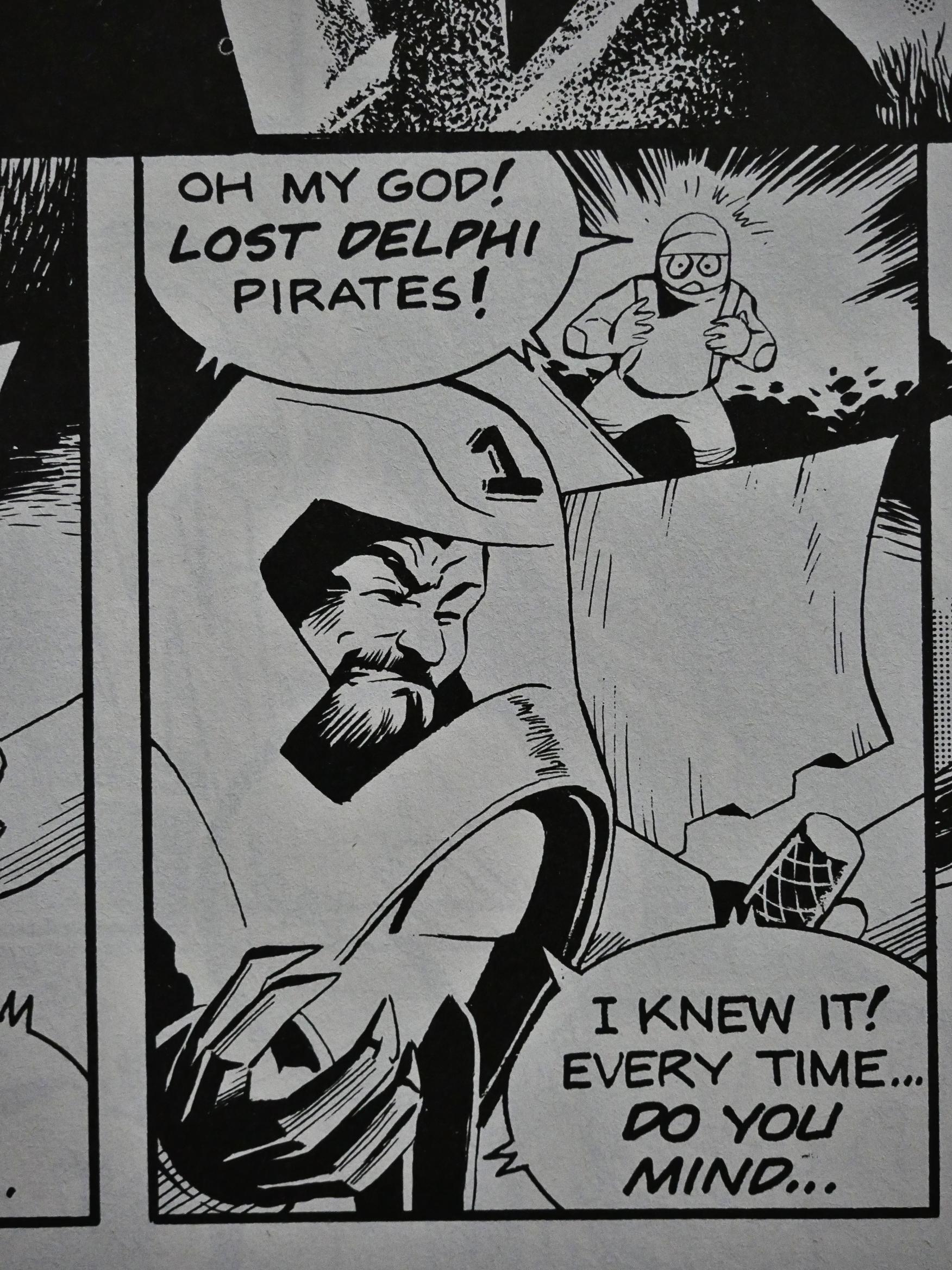

And it’s Barker’s funniest story from Books of Blood, if I remember correctly. That doesn’t really say much, because it’s pretty much the only one that tries to be funny, and it’s more of a “oh, that’s very mirthful indeed” thing than a “ha ha” story. It’s about a guy tricking the devil (I mean, a demon).

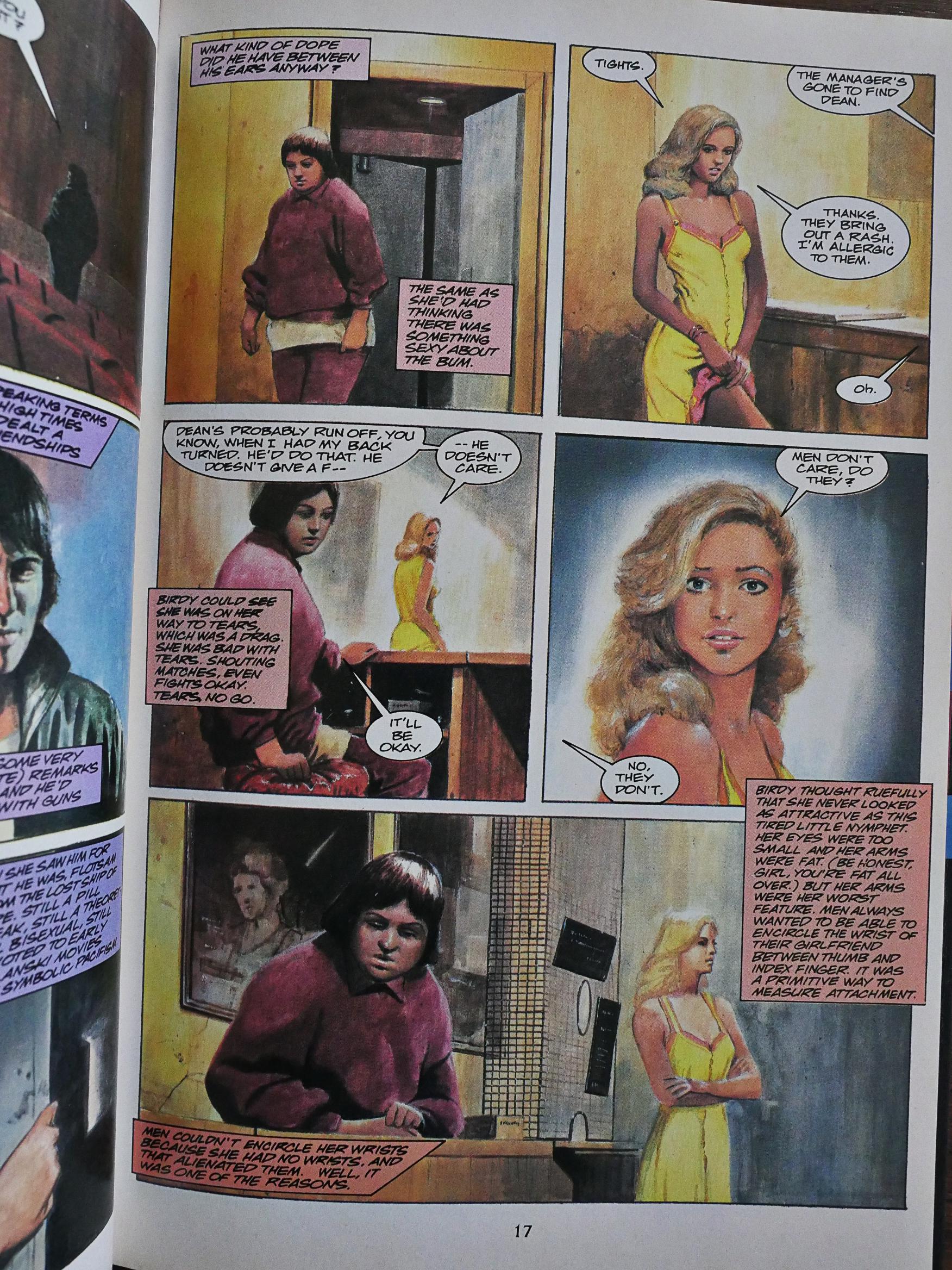

And the longer format helps. Steve Niles insists on preserving a lot of Barker’s words, even when they’re perhaps somewhat superfluous, but we’re not in “illustrated text” territory, which a lot of the other Eclipse adaptations suffered from.

John Bolton certainly knows how to draw cartooney cats and bursts of action, as well as static tableaux.

There’s something very humanist about his approach. It’s somewhat photo-reference based, but it’s not crippled by it, as some of the other painterly artists Eclipse favoured around this time.

It was nominated for “Best Graphic Album” in the 1992 Eisner awards, but didn’t win.

And we get a reprint from a Tapping the Vein in this edition of Yattering.

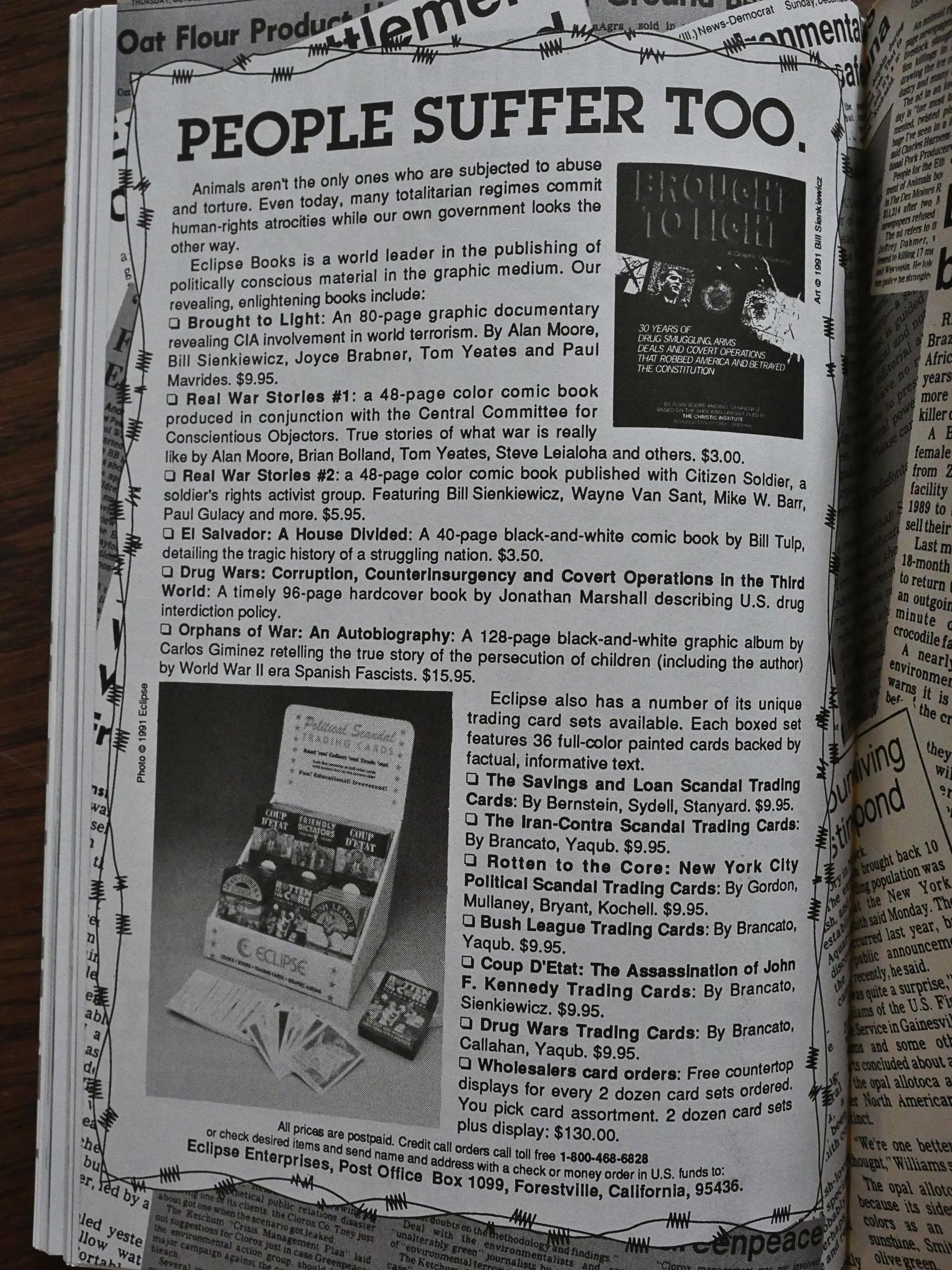

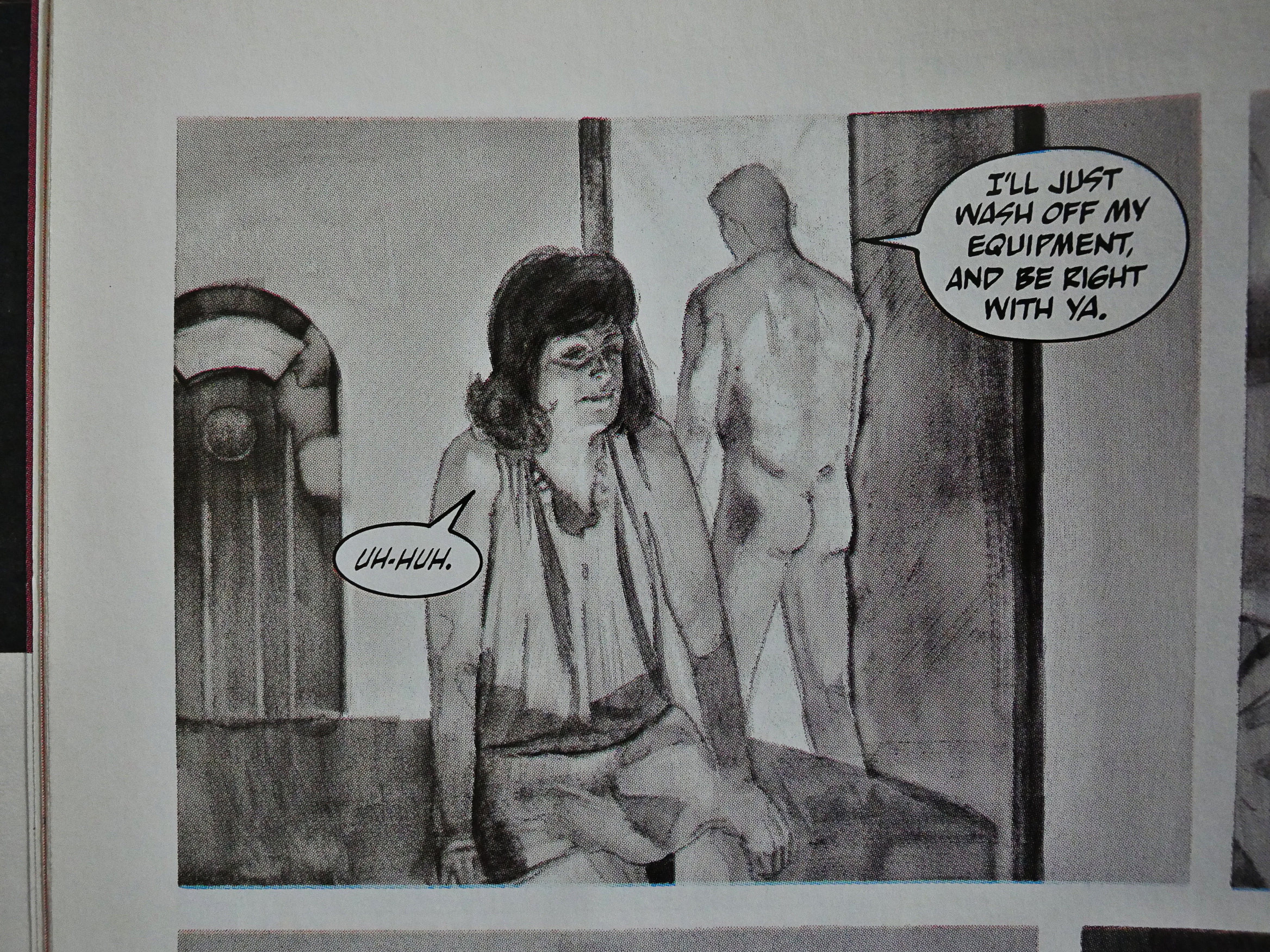

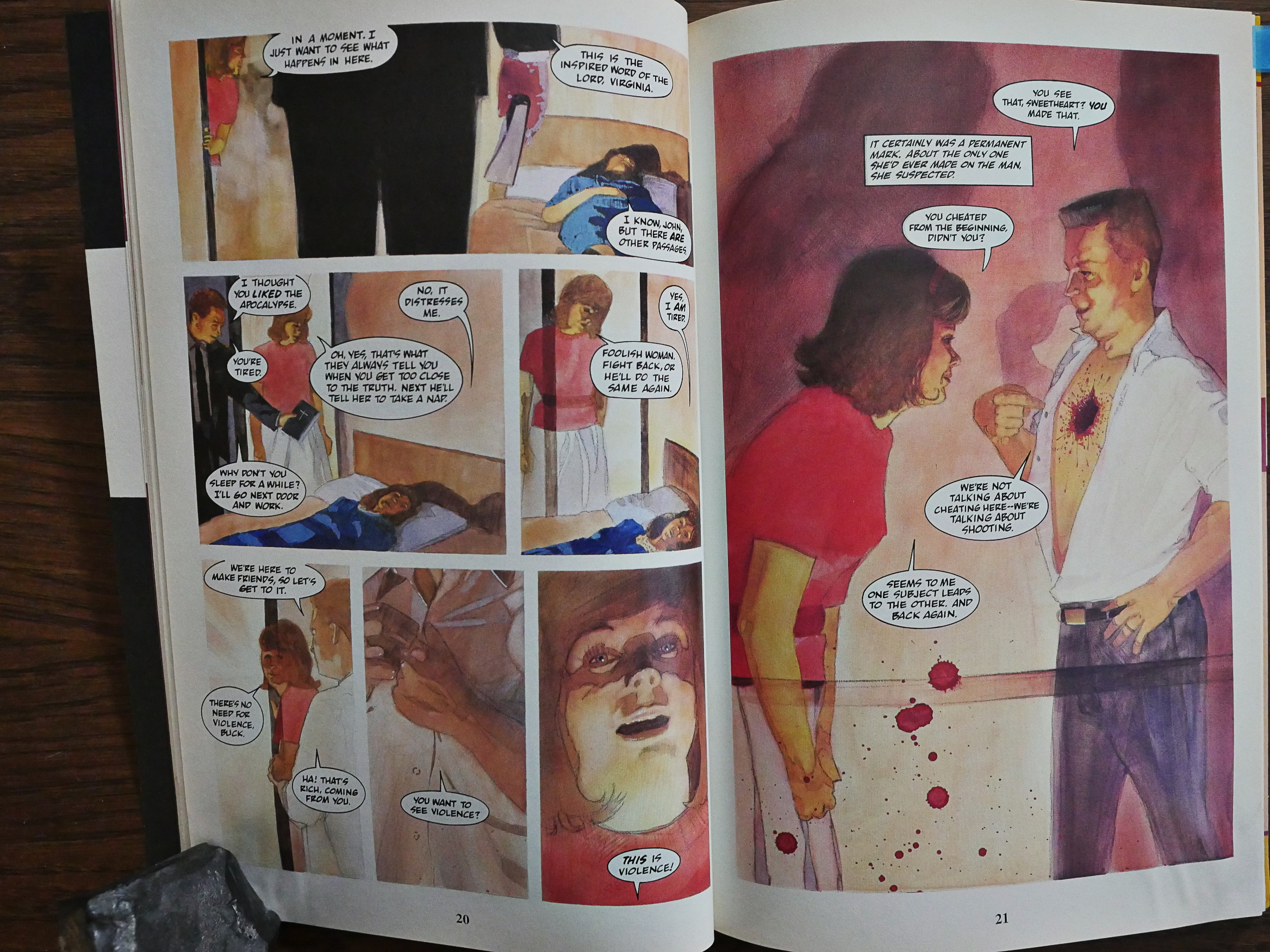

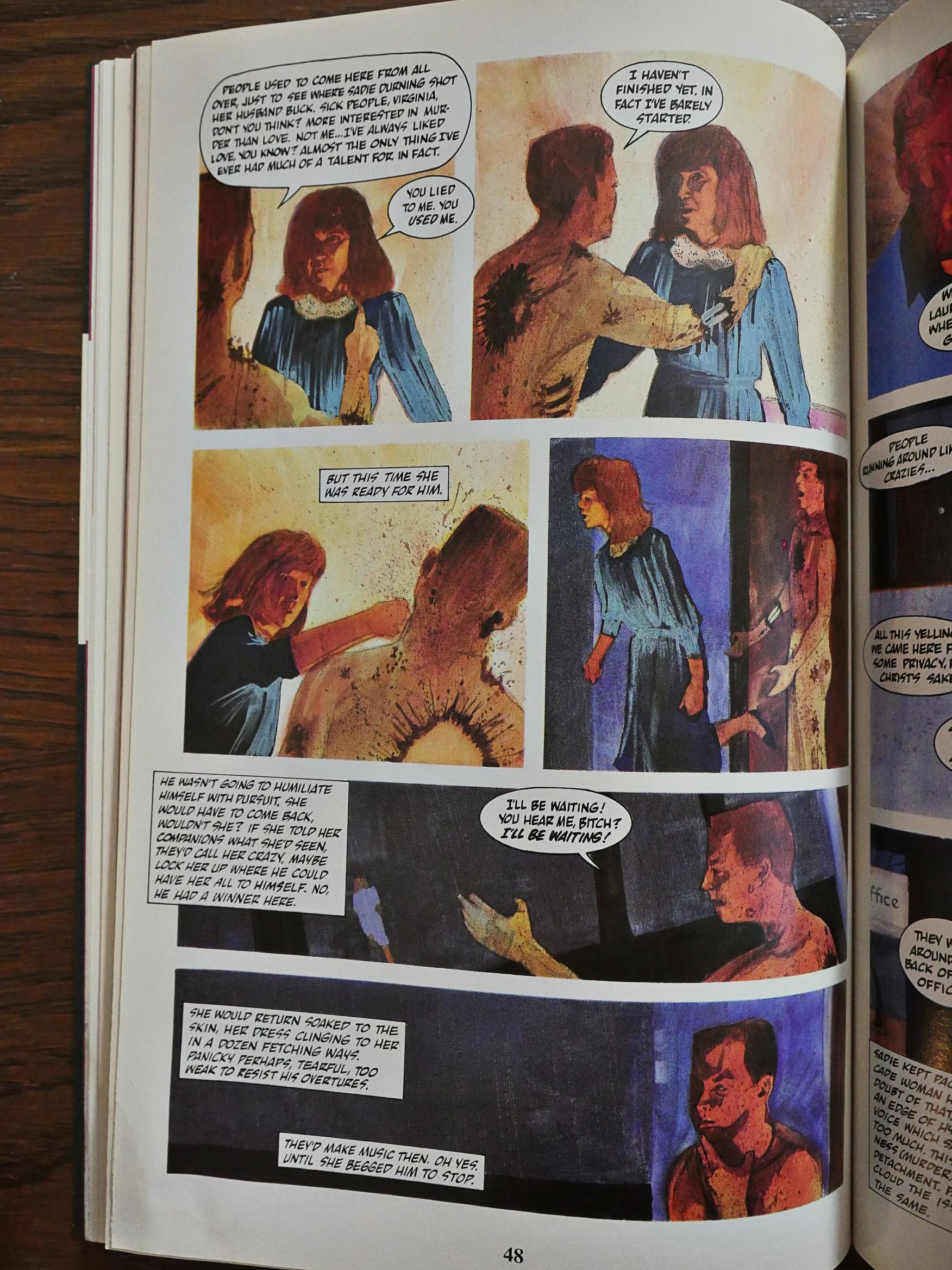

I was curious about Revelations. cat ⊕ yronwode promised, I meant, warned in one of her page two columns that people would find this book very controversial indeed… if they were able to find it at all. It not only has “fully frontal” nudity, but it deals with religion, I mean Christianity, and that’s so controversial that retailers all over the US were refusing to carry it. Or something.

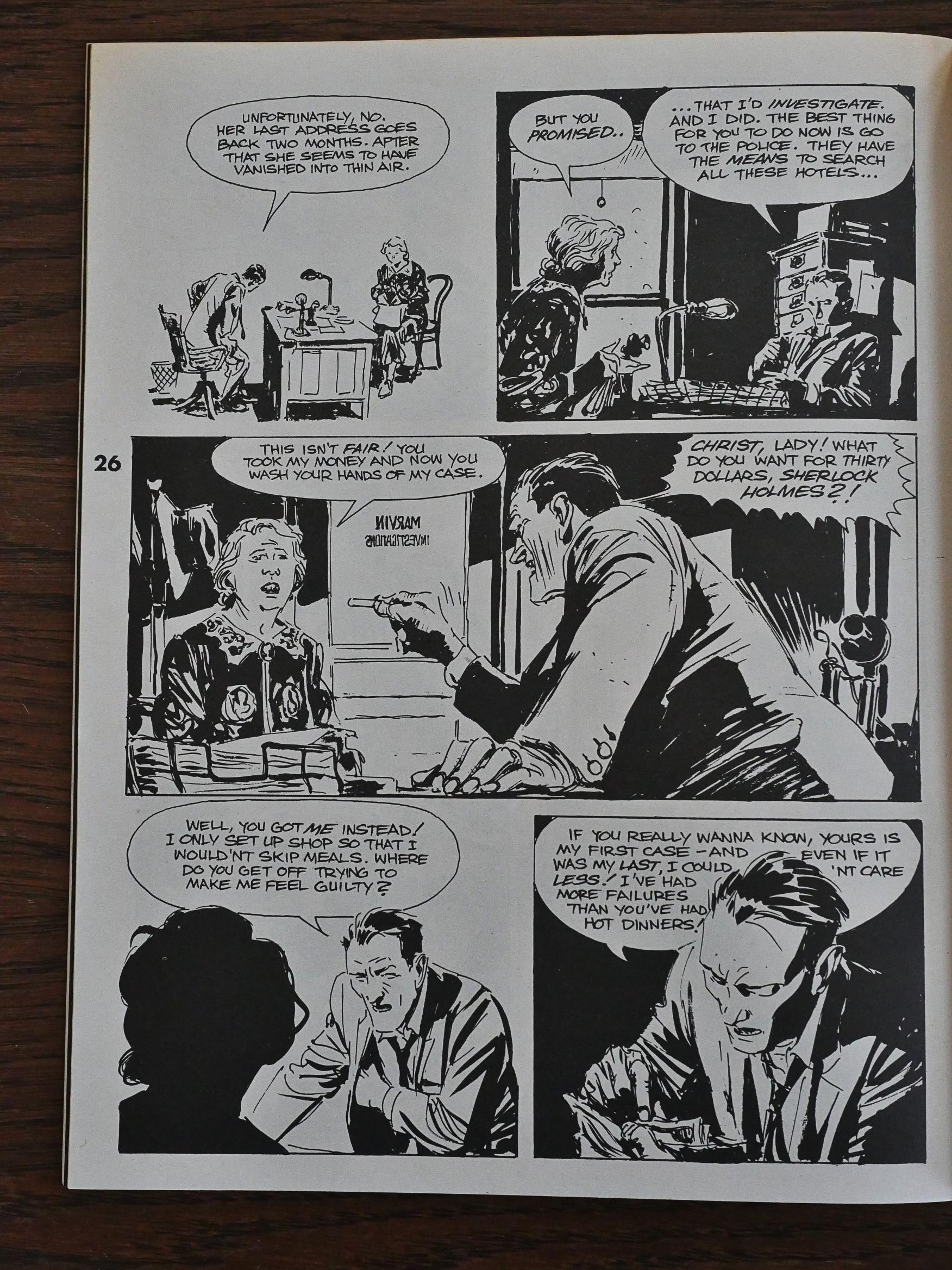

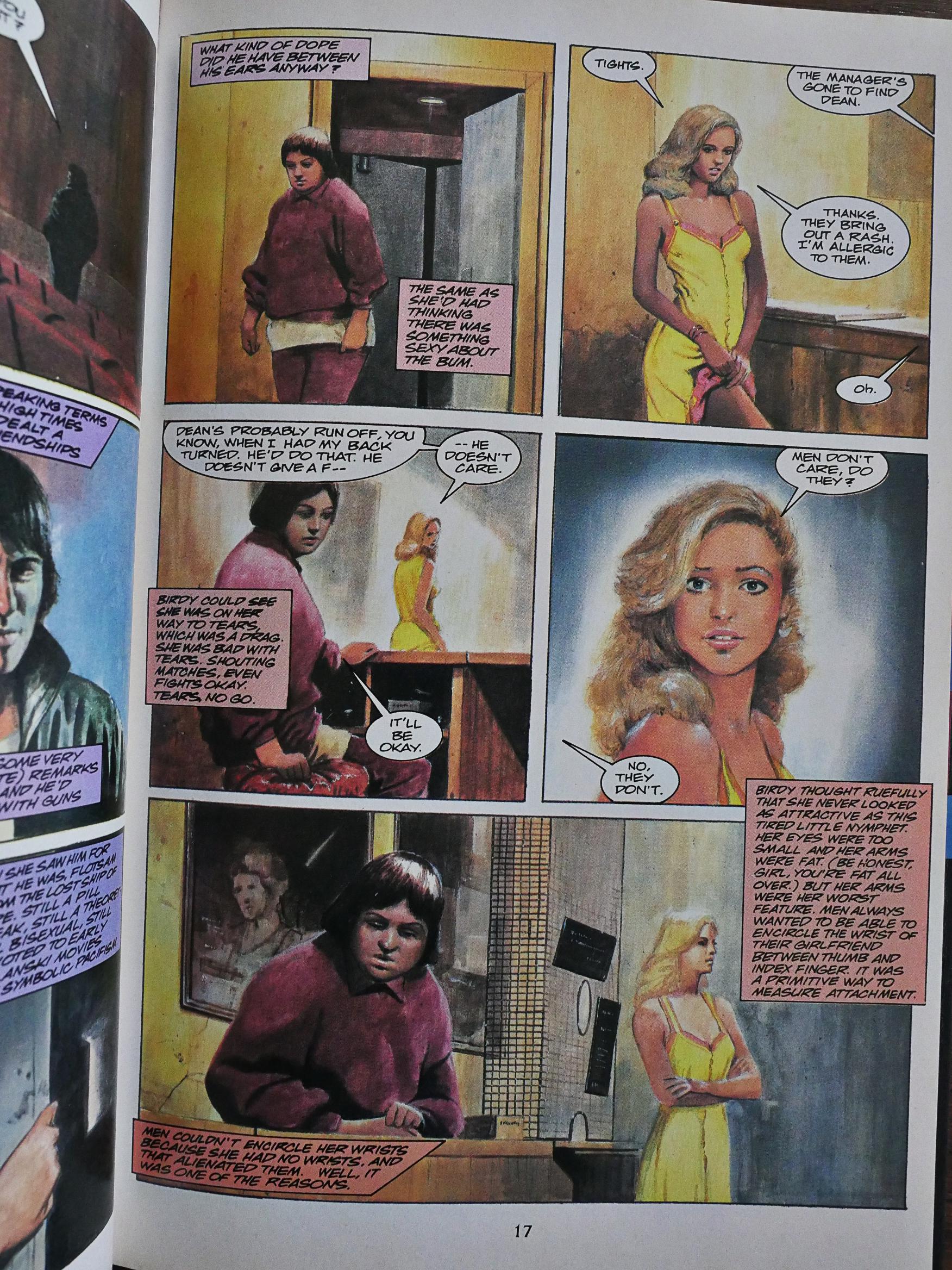

Lionel Talaro’s artwork is very photo-based, but he’s got a wonderful sense of colour and drama. Steve Niles, again, did the adaptation, and I think perhaps it’s the best one of the bunch. Niles keeps a lot of Barker’s exposition, but it’s a pretty brief, uncomplicated story, so it reads well. The pages aren’t totally overpowered by captions.

The promised nudity does appear, but isn’t, I think, anything anybody would be shocked by.

Neither is it particularly blasphemous, so either those retailers were on bad acid, or yronwode was trying to pique the reader’s interest by promising controversy.

While Talaro’s artwork mostly looks great, he doesn’t do action. I mean, he tries to, but it’s pretty bad. I guess that’s what happens when you tell people “stand that way!”, take a snapshot, and then draw exactly what’s on the picture.

Ah; it’s his first comic book. Makes sense.

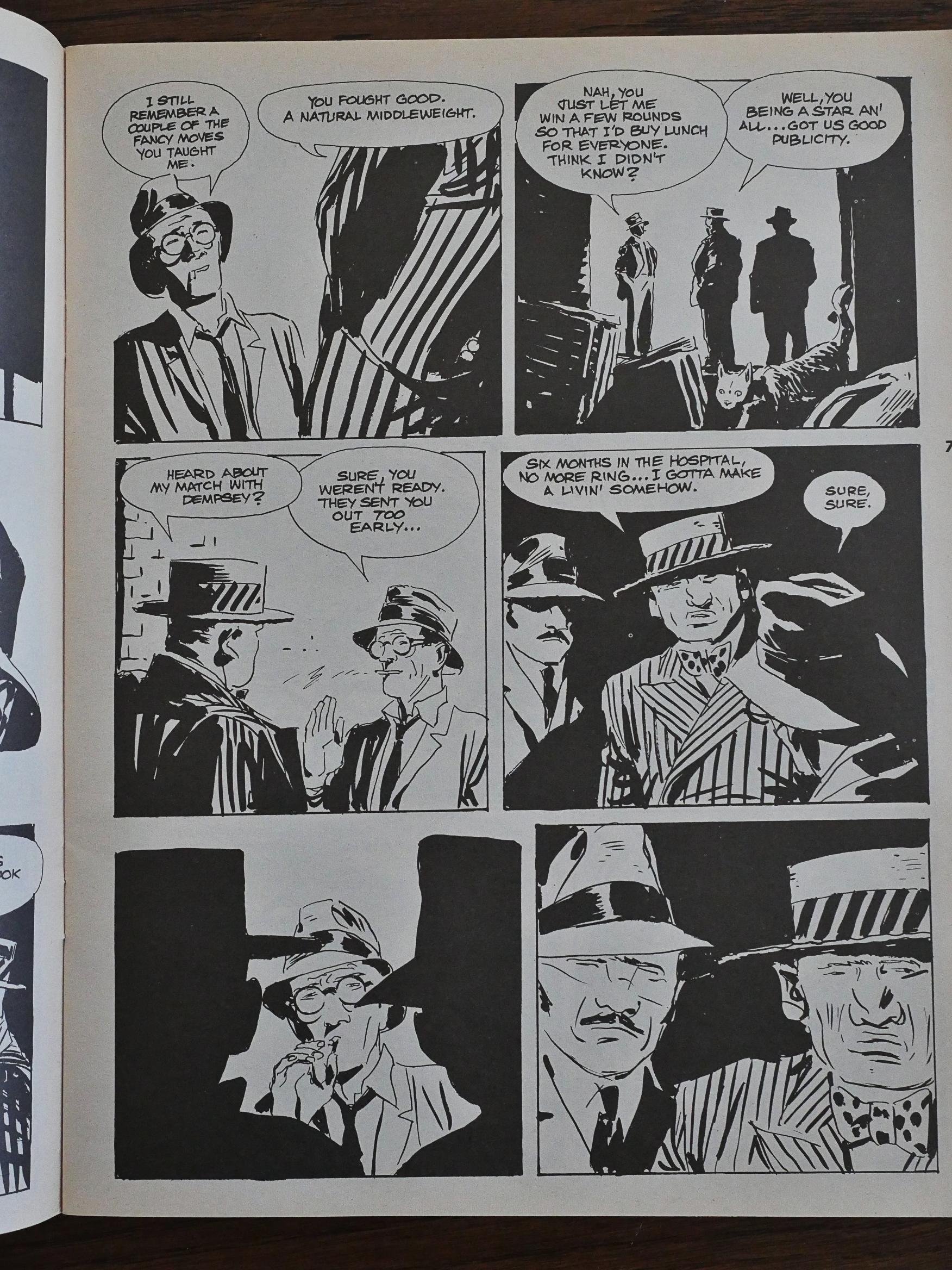

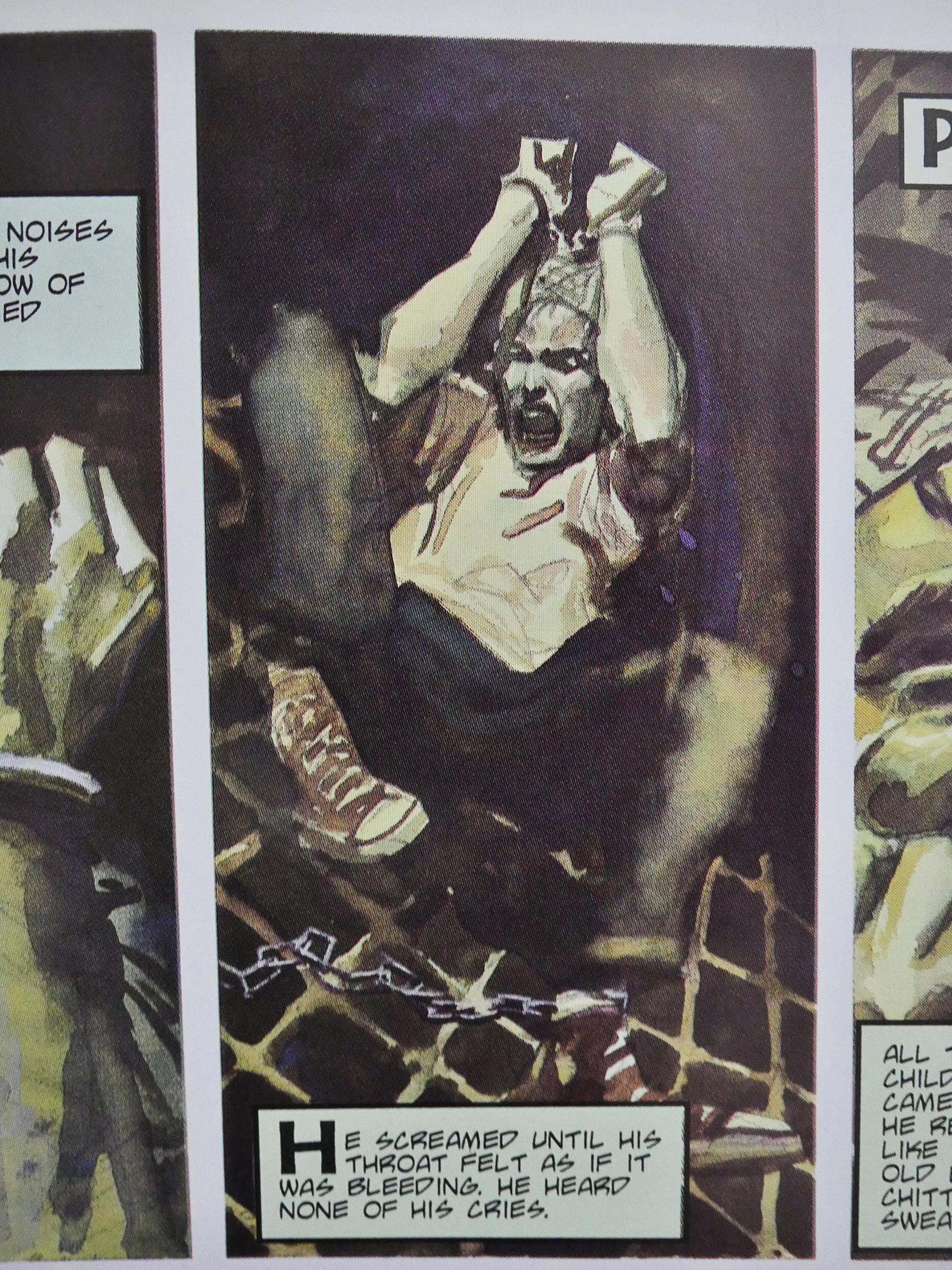

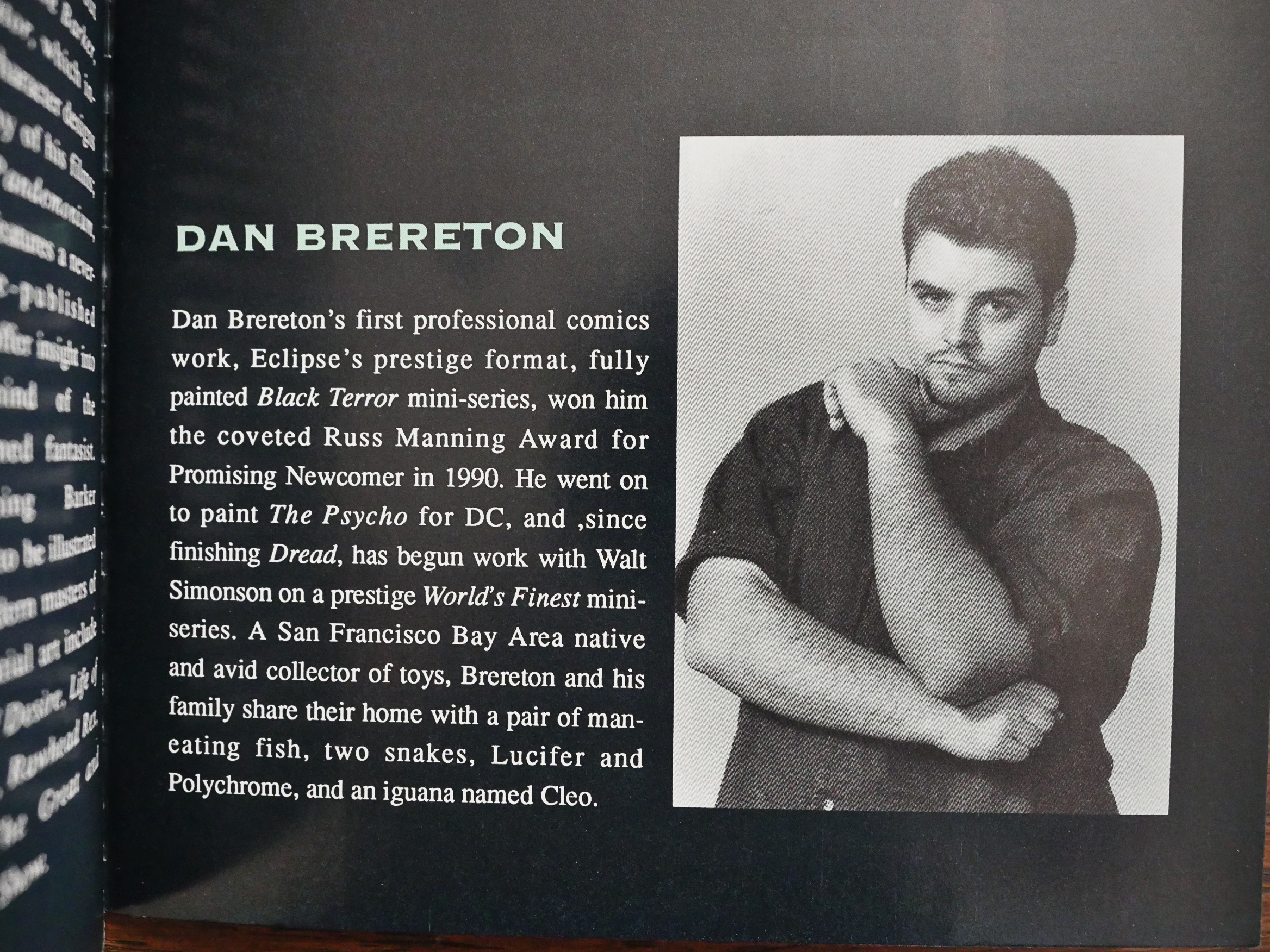

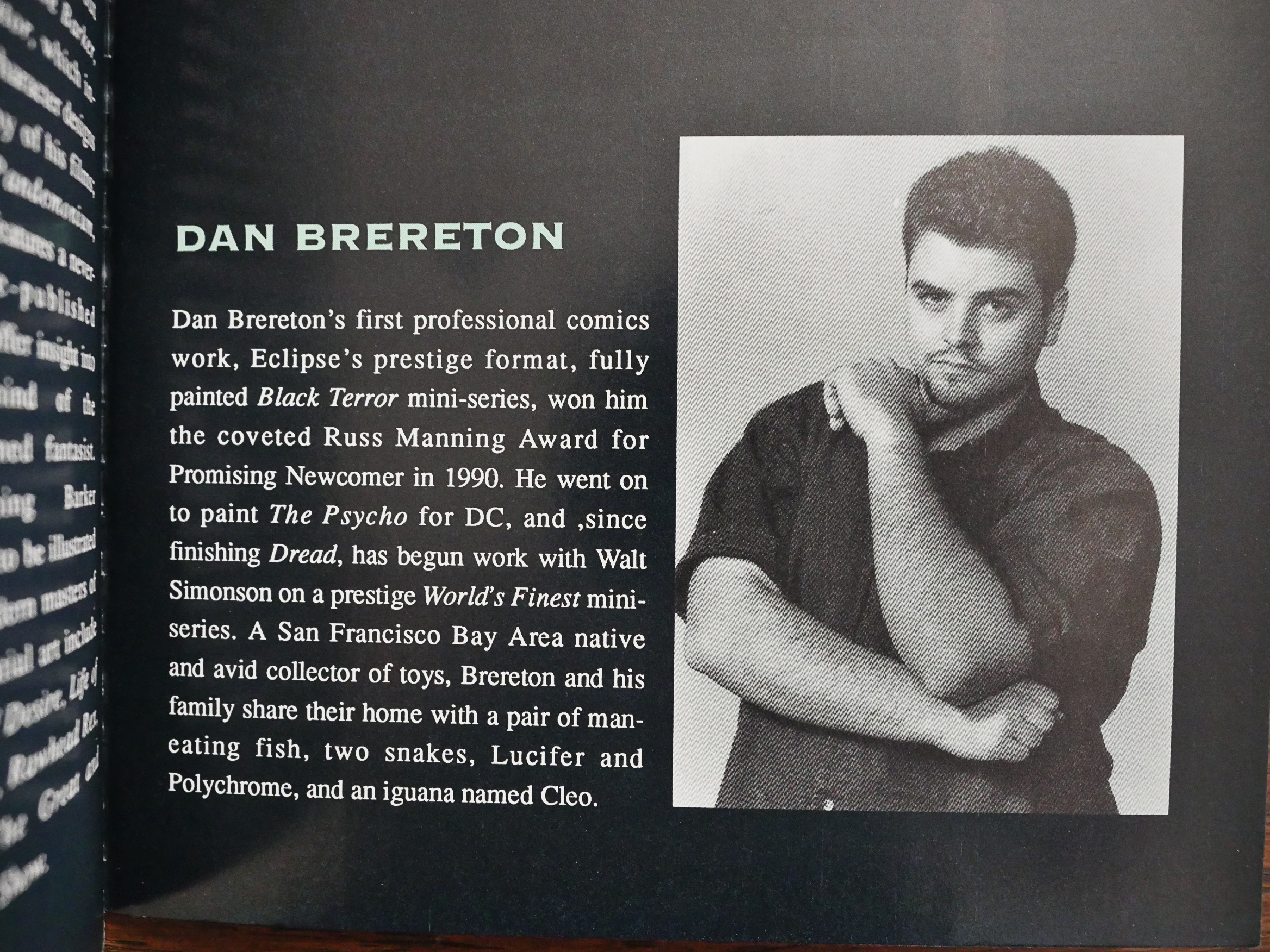

Then there’s Dread… and artist Dan Brereton at least calls out his photo reference.

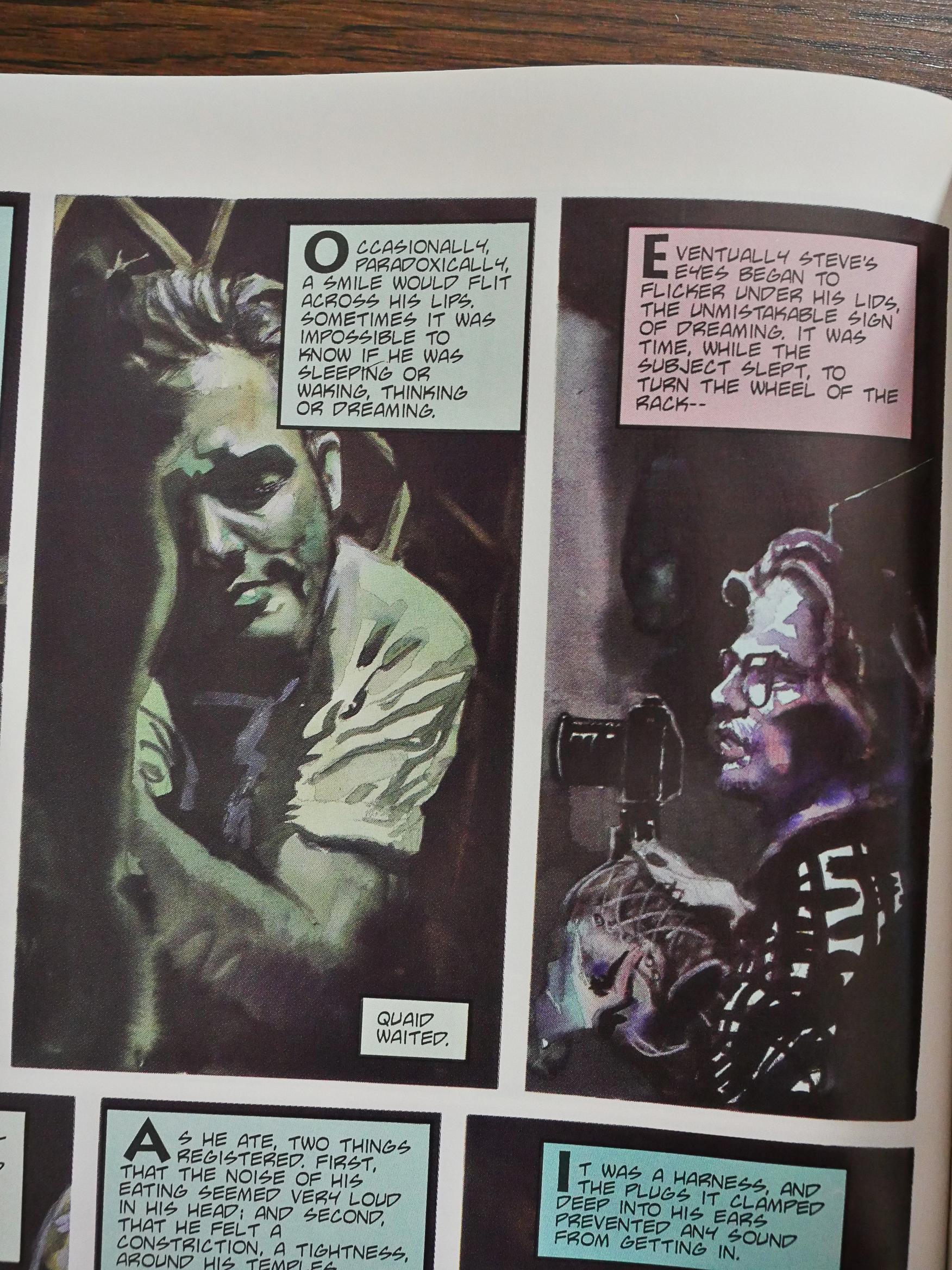

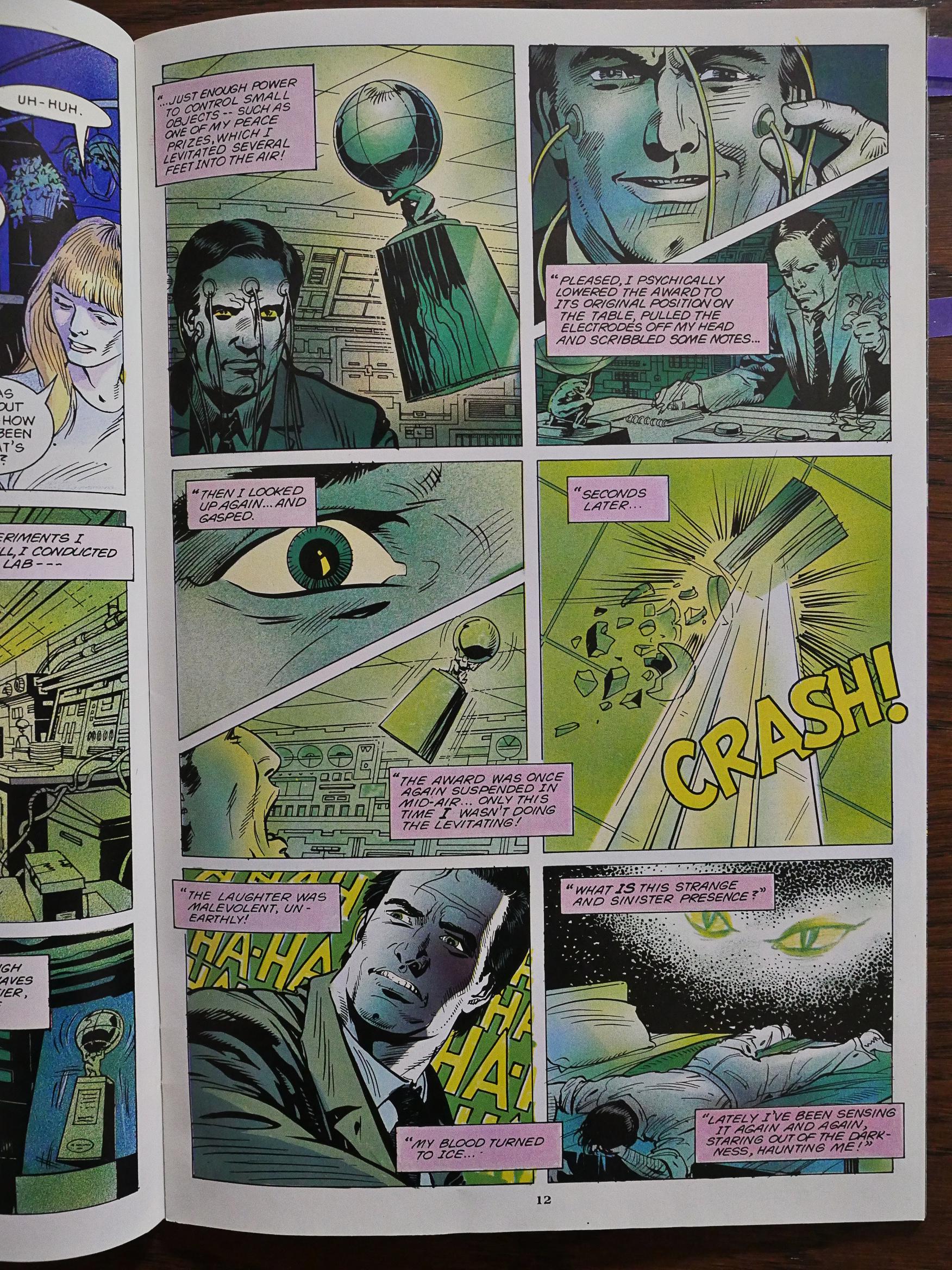

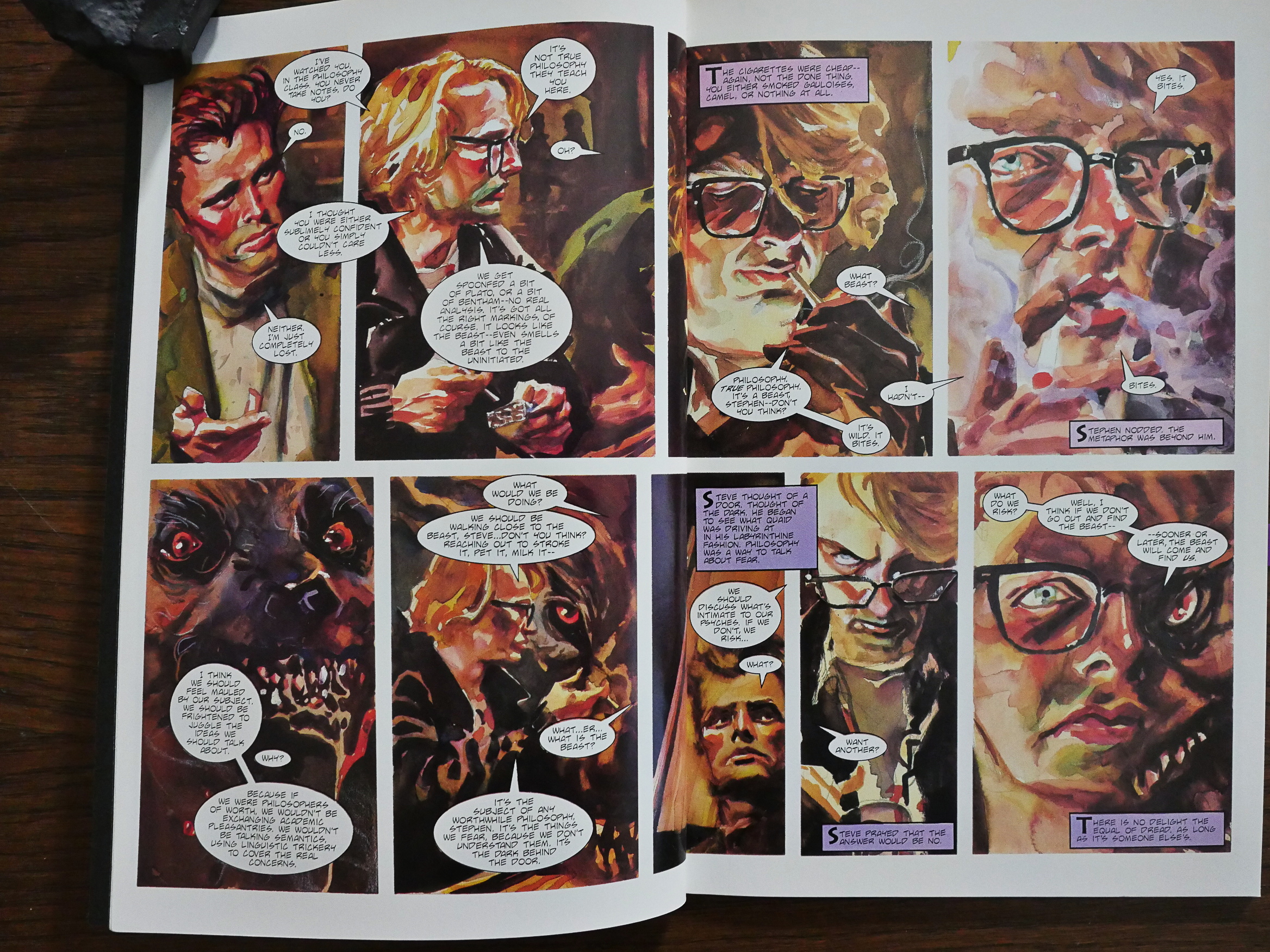

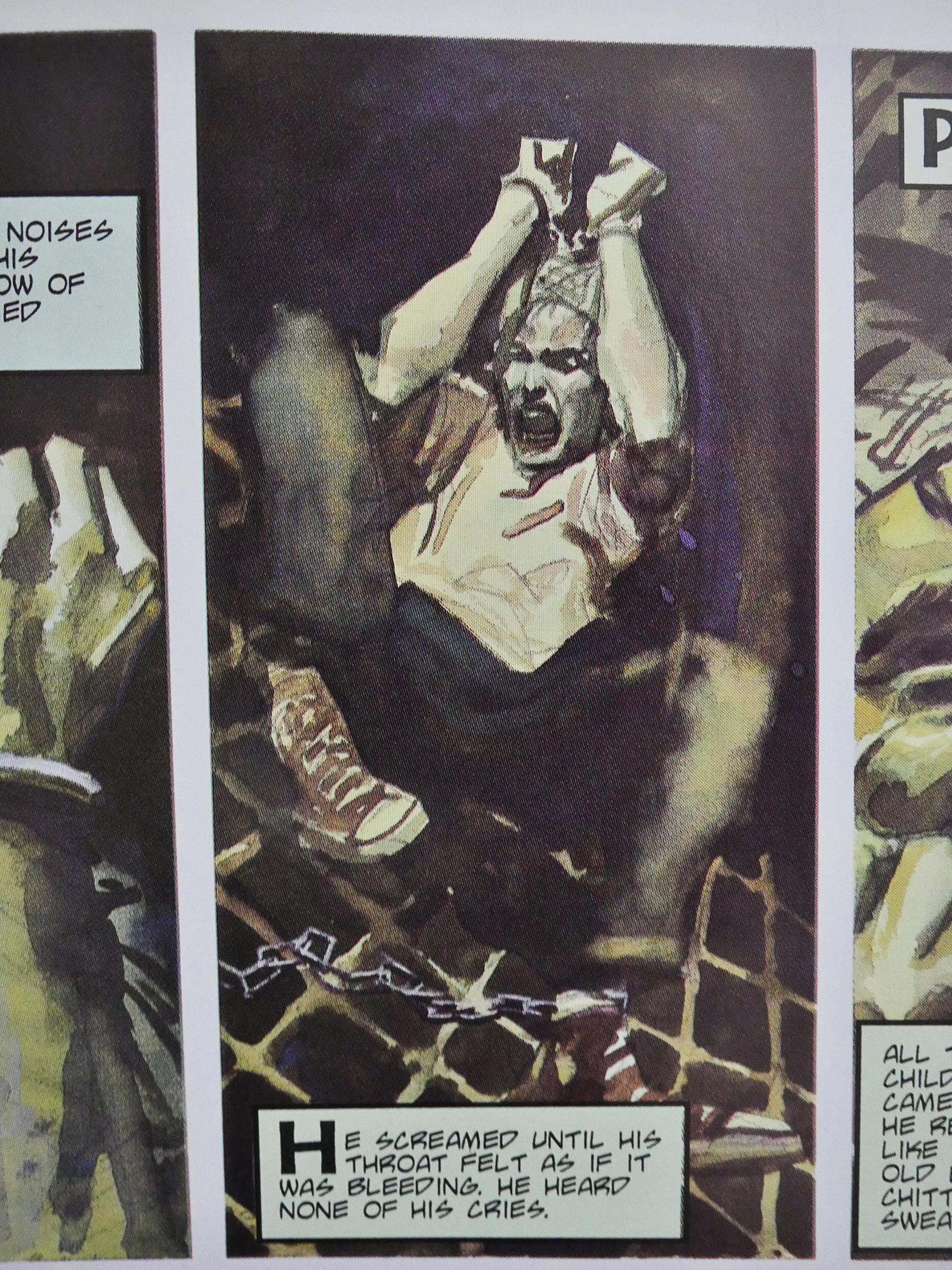

And, indeed, these are very much based on photo reference, Brereton goes hog wild with angles and colours and strange transformations. It’s a really fun book just to look at: Every new page spread has something new and interesting.

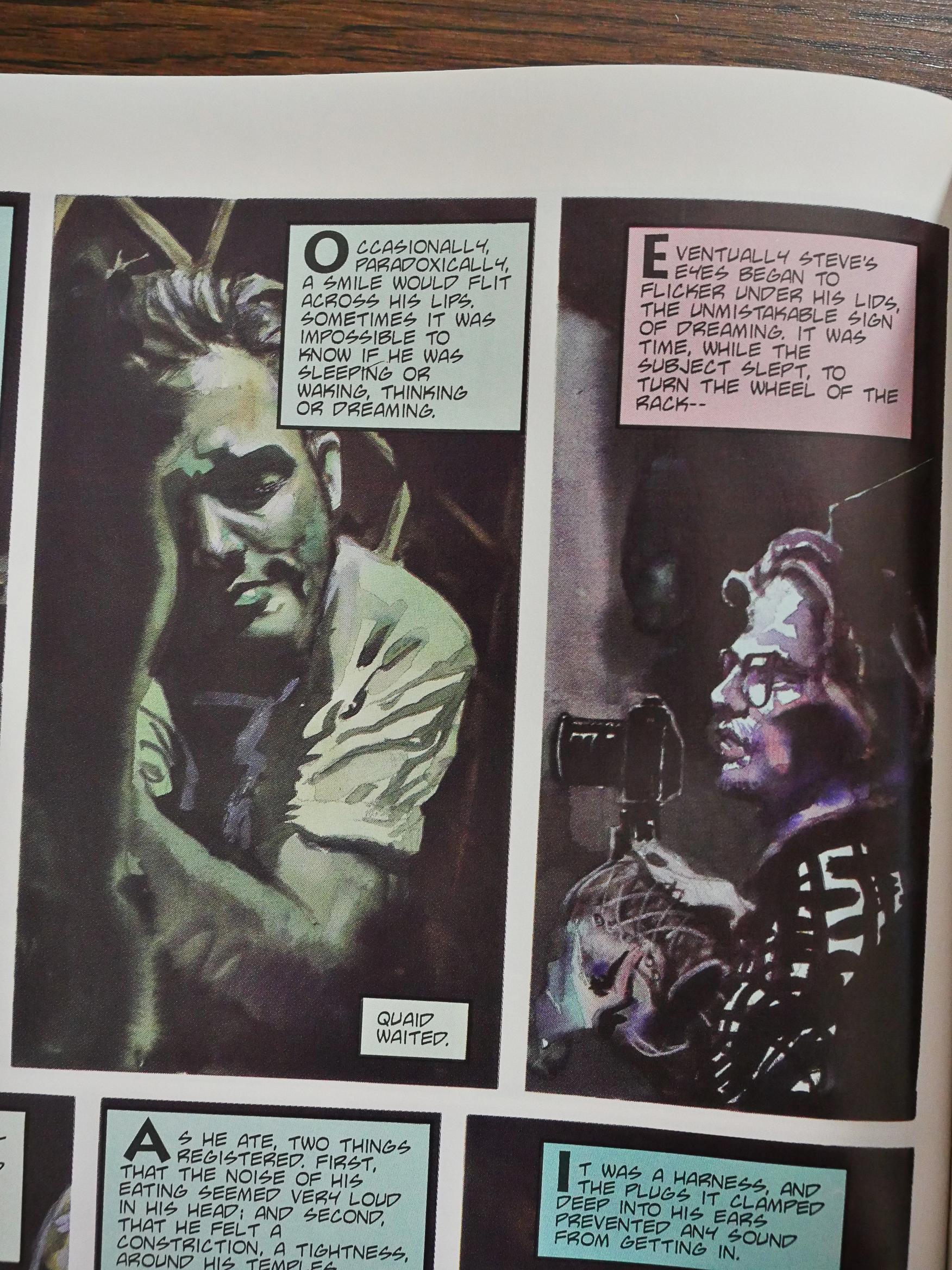

If only I could say the same about Barker’s story or Fred Burke’s adaptation. It’s ridiculously exposition heavy. I understand that they want to retain Barker’s mood, and the easiest way to do that is to just put as many of his words in as possible, but it gets a bit tedious having the captions and the images telling us the same thing.

And the story is basically just a tortured O’Henry thing that takes way too long to get to the point, and the point isn’t really very sharp.

And what’s it about these people sleeping so heavily?

And has Barker never worn hearing protection? You can still hear your voice, dude.

Oh, Brereton won a Russ Manning Award (whatever that was) for The Black Terror? That’s totally understandable.

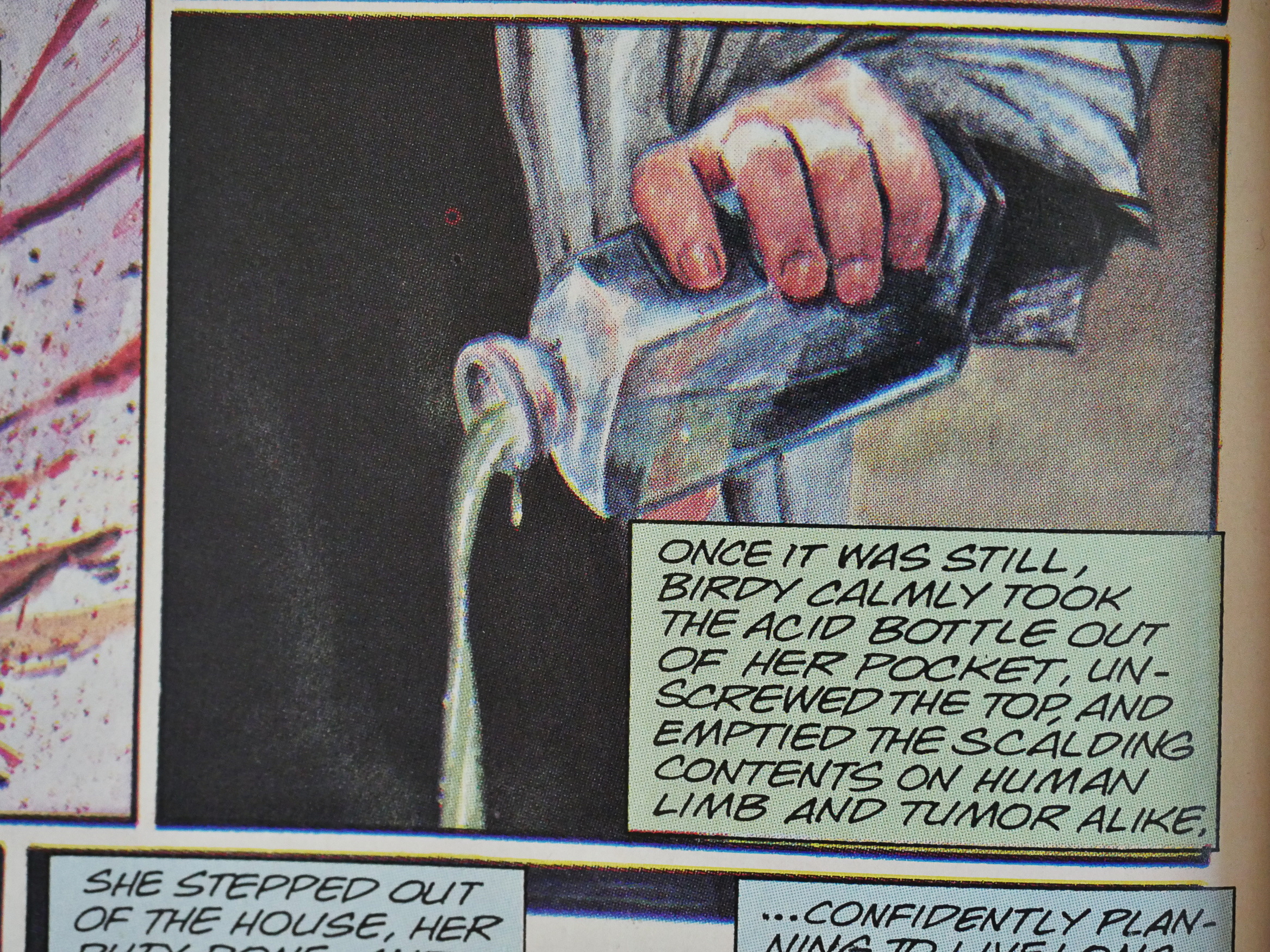

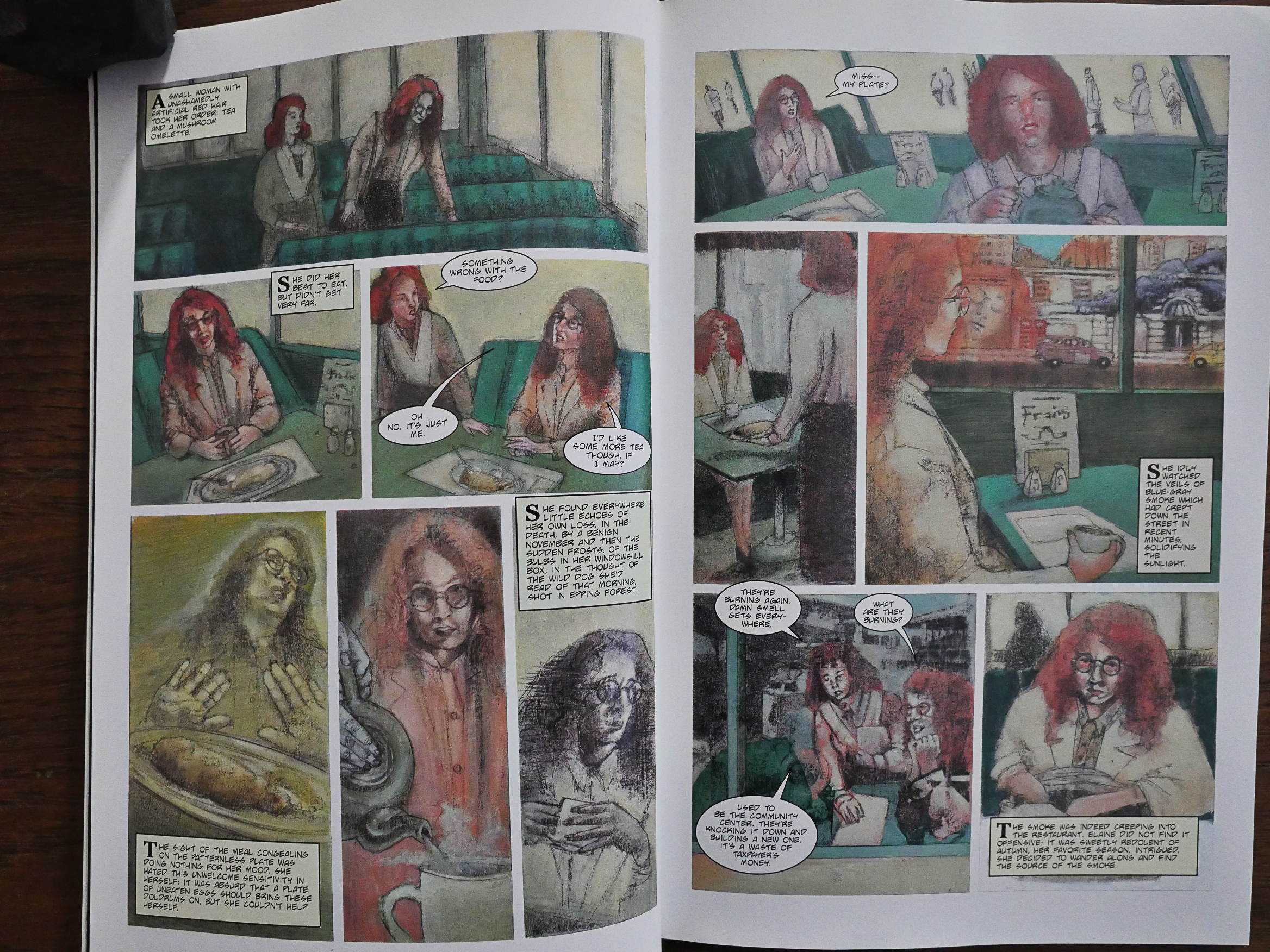

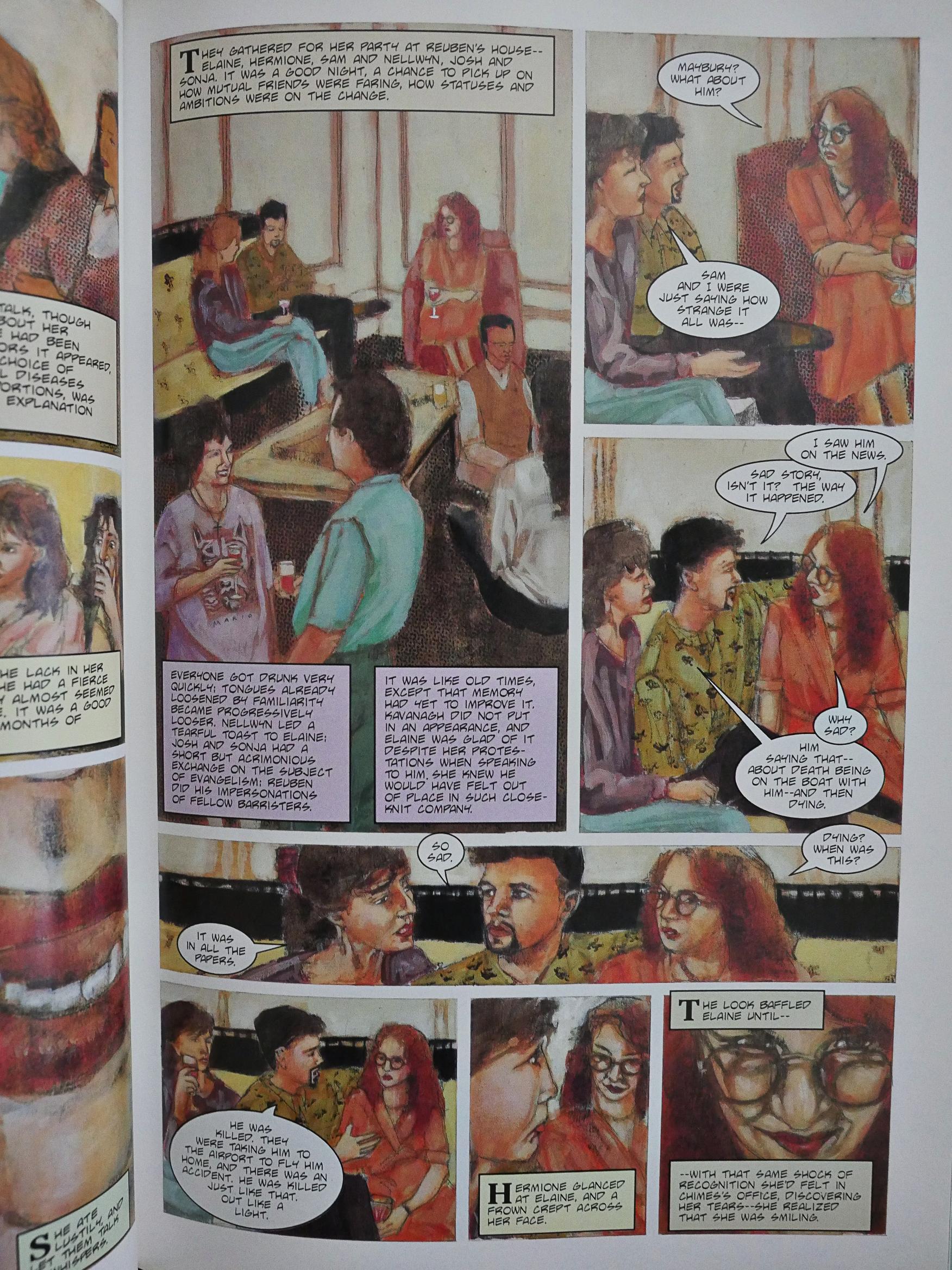

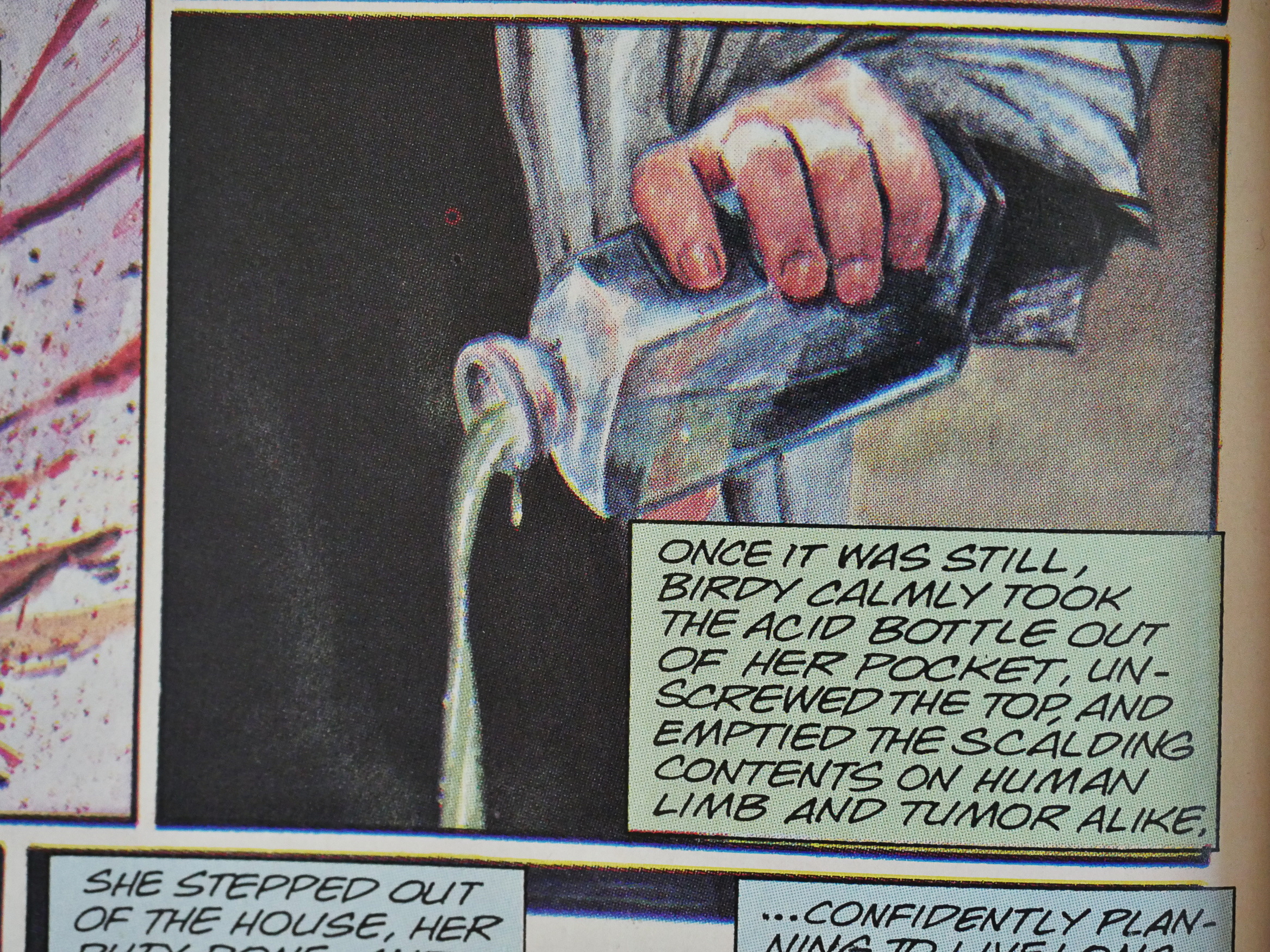

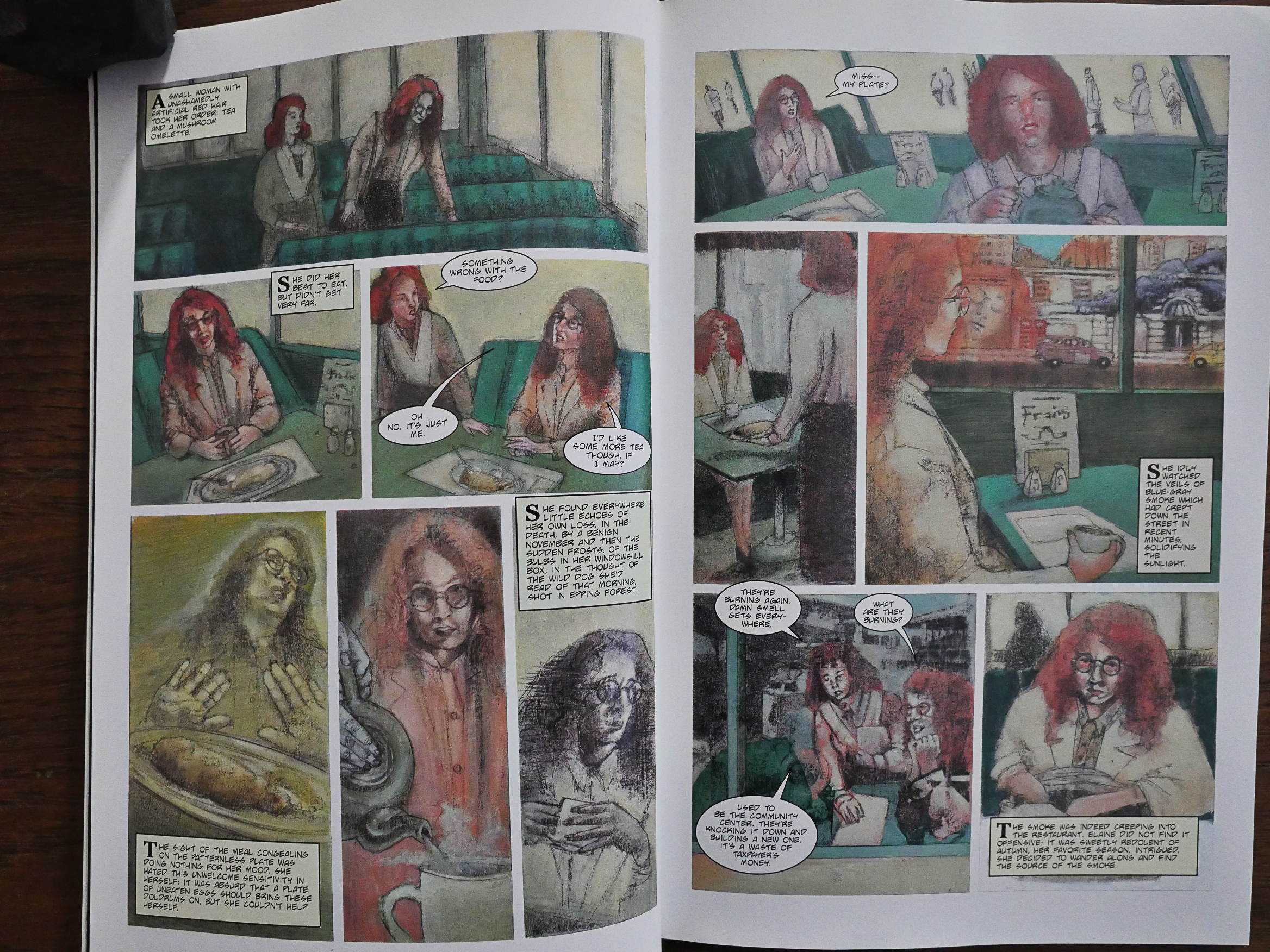

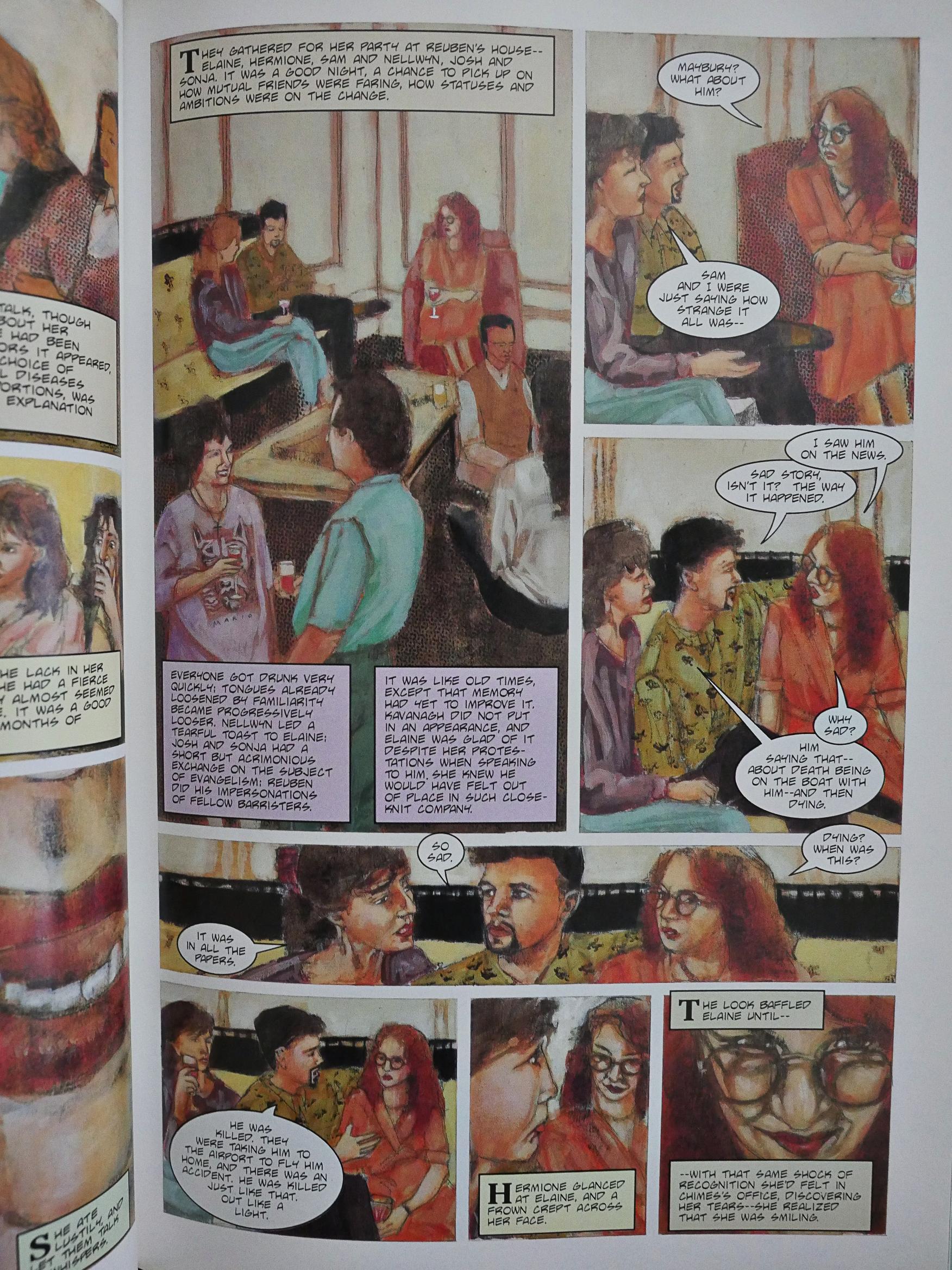

And finally (well, except for Rawhead Rex, which I’ll cover in a separate blog post because it’s the very last thing Eclipse published, and it also has an interesting controversy behind it) and least, we have The Life of Death. It’s got some good character portraits (both literally and figuratively), but it’s not that interesting of a story. I don’t know how many stories they had left to choose from, but it’s understandable that they didn’t go for this one first…

Stewart Stanyard’s artwork does suit this static story very well. He manages to scare up some interest in all these scenes where little happens.

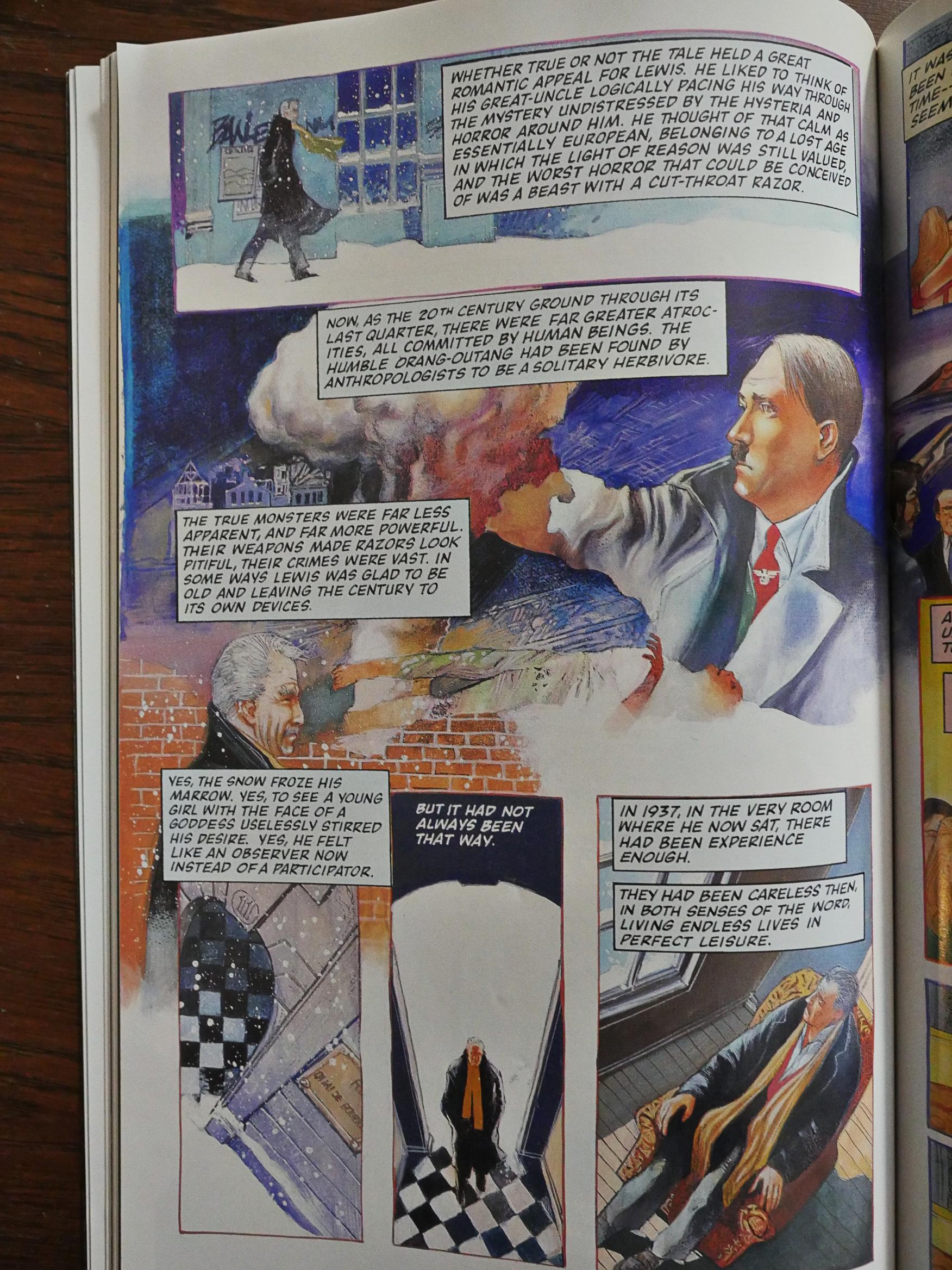

The backup story here, New Murders on the Rue Morgue, with artwork by Hector Gomez, is not a reprint from Tapping the Vein, I think? It’s also not very good.

My google-fu may just be very bad, but these comics don’t seem to have been reprinted after Eclipse went under? Can that be true? Some rights issue, perhaps? Because I can’t believe that these wouldn’t still sell, even if they’re not exactly perfect. Spending this evening reading these comics was rather nice.

Since these comics have been out of circulation for a couple of decades, finding people talking about them on the web isn’t easy. Here’s somebody on Goodreads:

I read Dread in Books of Blood Volume 2 a few years back and found it a bit difficult to get into. This graphic novel still makes the skin crawl but cuts out a lot of the tedious talk that bogged down the novella. The artwork is dread-worthy, washed with a dark-hued palette that certainly fits the tone of the story. This isn’t my favorite Barker short but it’s worth seeking out of if you’re a fan.

I’m not the only one who questioned Eclipse’s choice of stories to adapt:

Although “the life of death” short story is both unsettling and involving, the addition of the illustrations in this graphic novel do nothing to embellish the experience of Barker’s writing. The ” Murders in the Rue Morgue” is short enough to be painless, but still not interesting. It is a shame that they did not choose better stories for this compilation, although I sometimes think that certain authors works should not be “visualized” by anyone save the actual reader in their own mind’s eye. Pass on this one