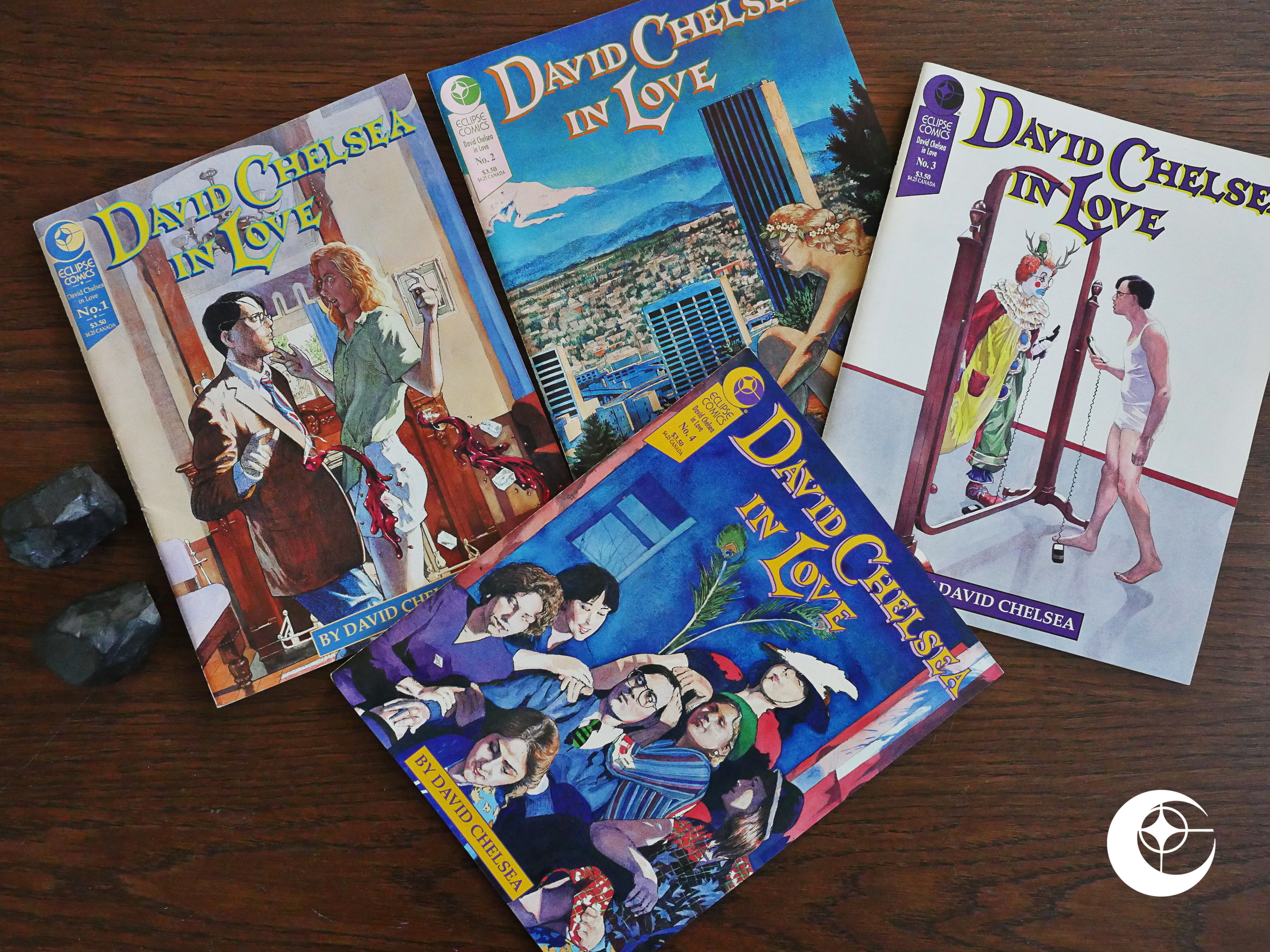

David Chelsea in Love (1991) #1-4 by David Chelsea.

This was one of the few late-stage Eclipse books I bought at the time, and I was hugely taken by it. Just as with Alec, it seemed like a new, fresh twist on autobiographical comics. Even if that new twist was basically making the storyline feel like an independent romantic comedy.

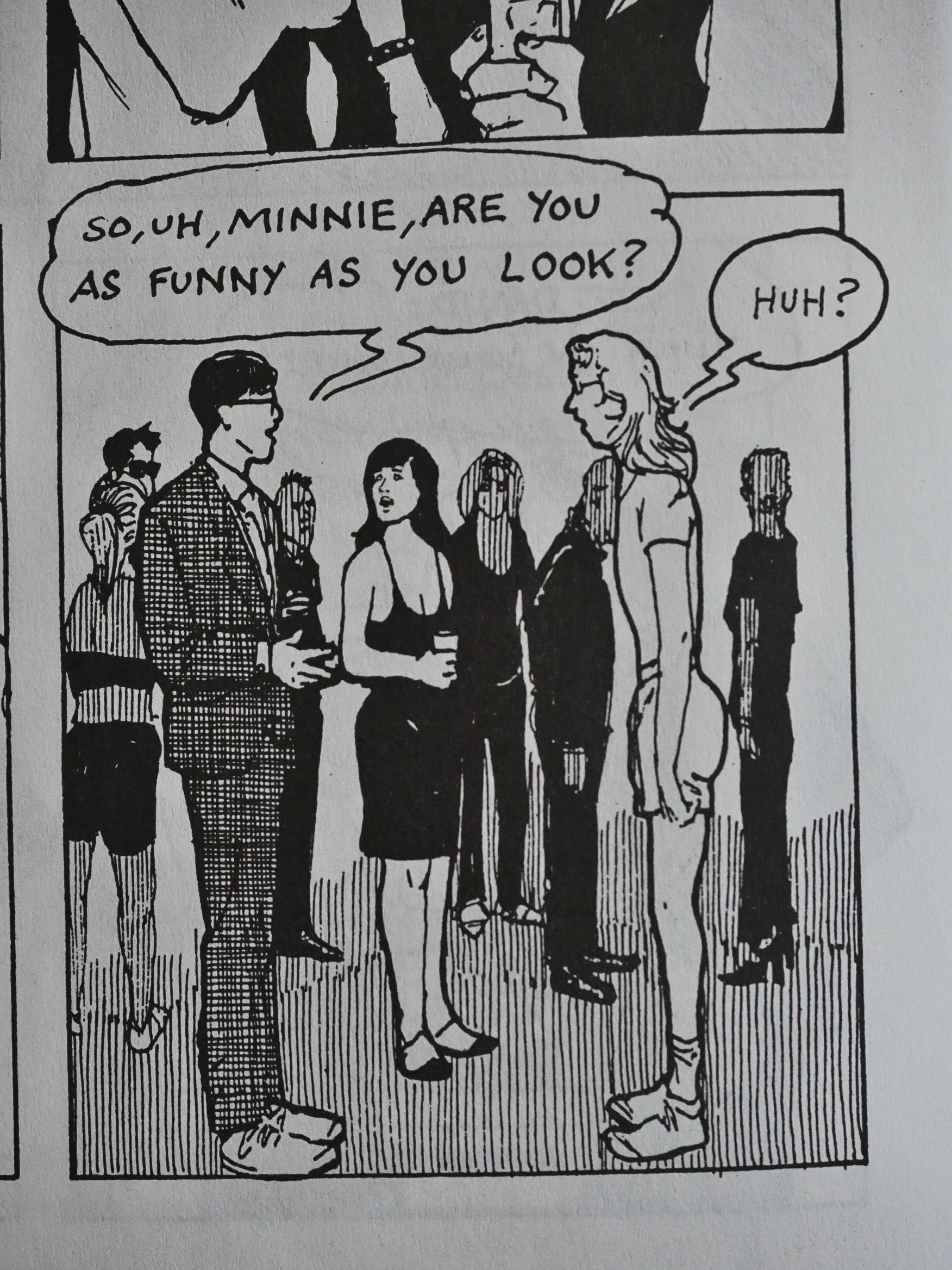

With meet cutes and all.

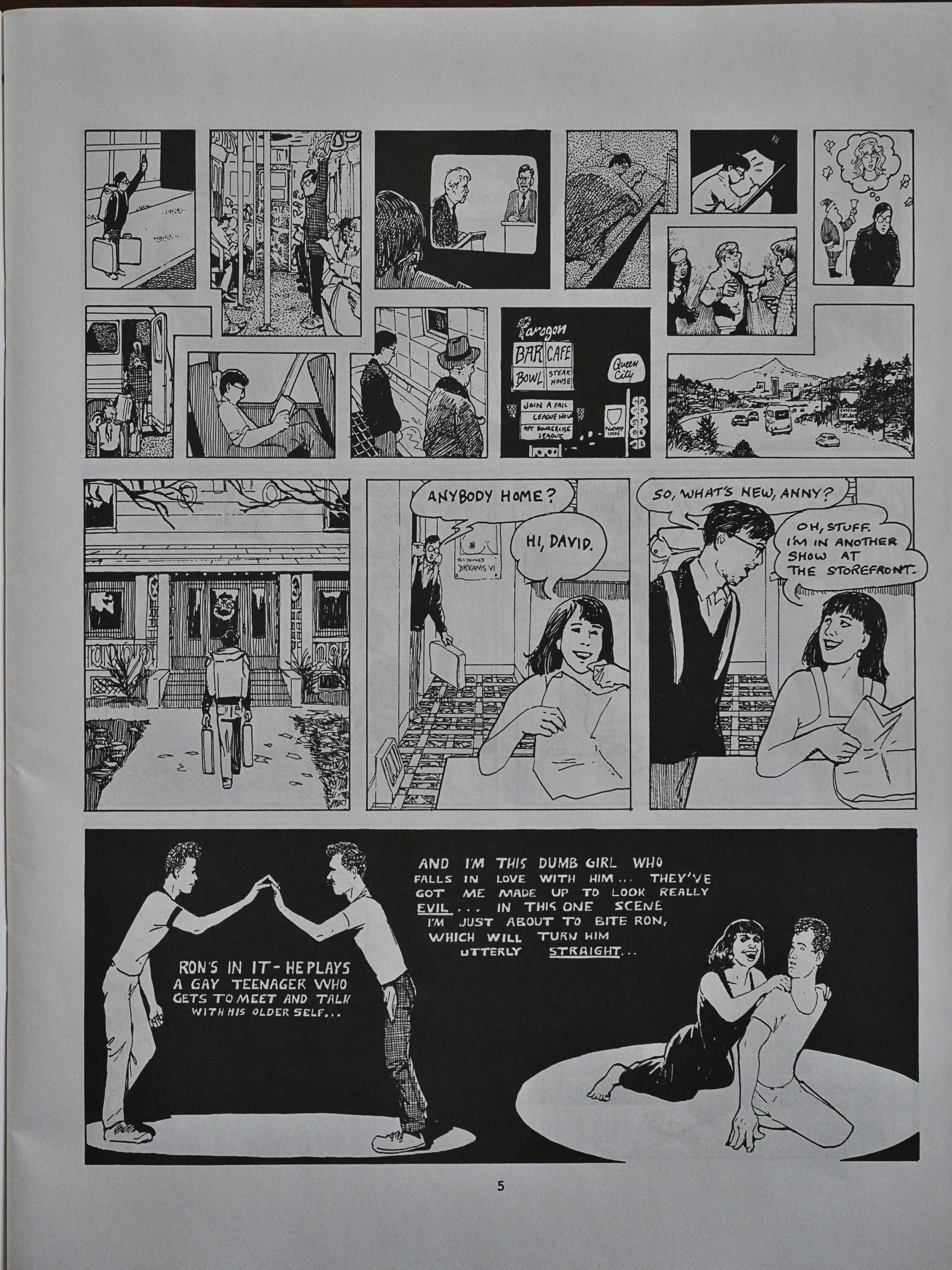

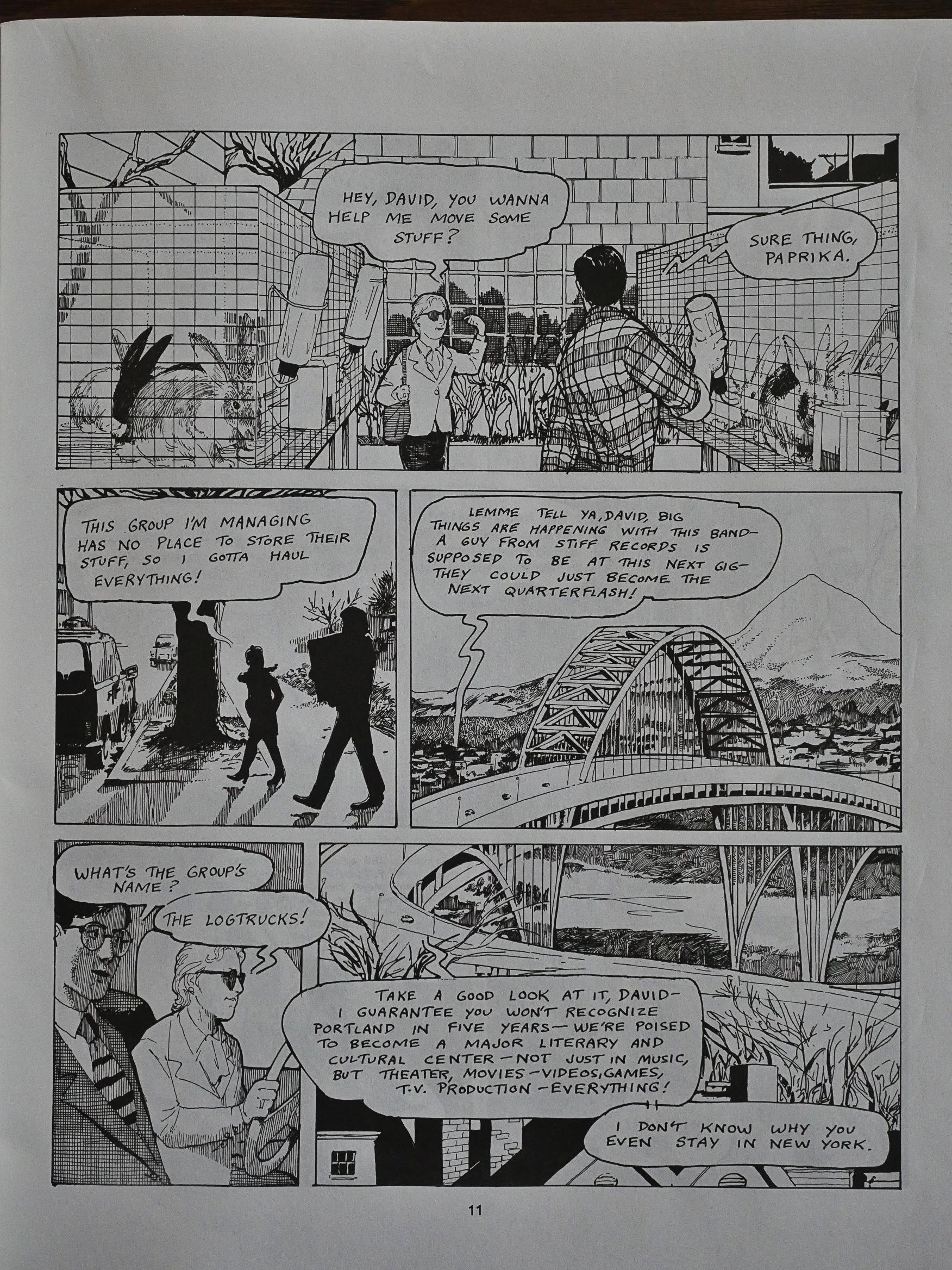

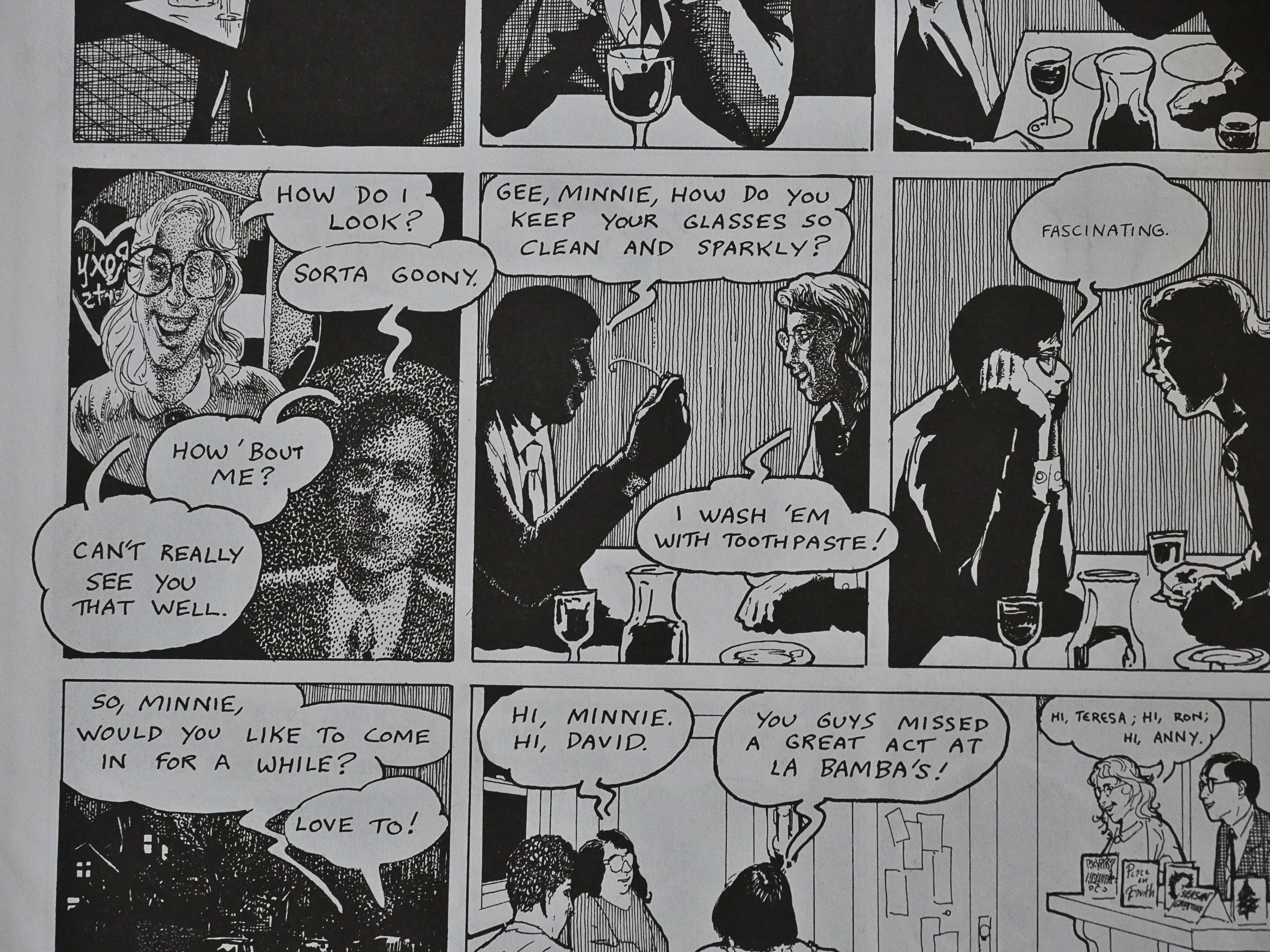

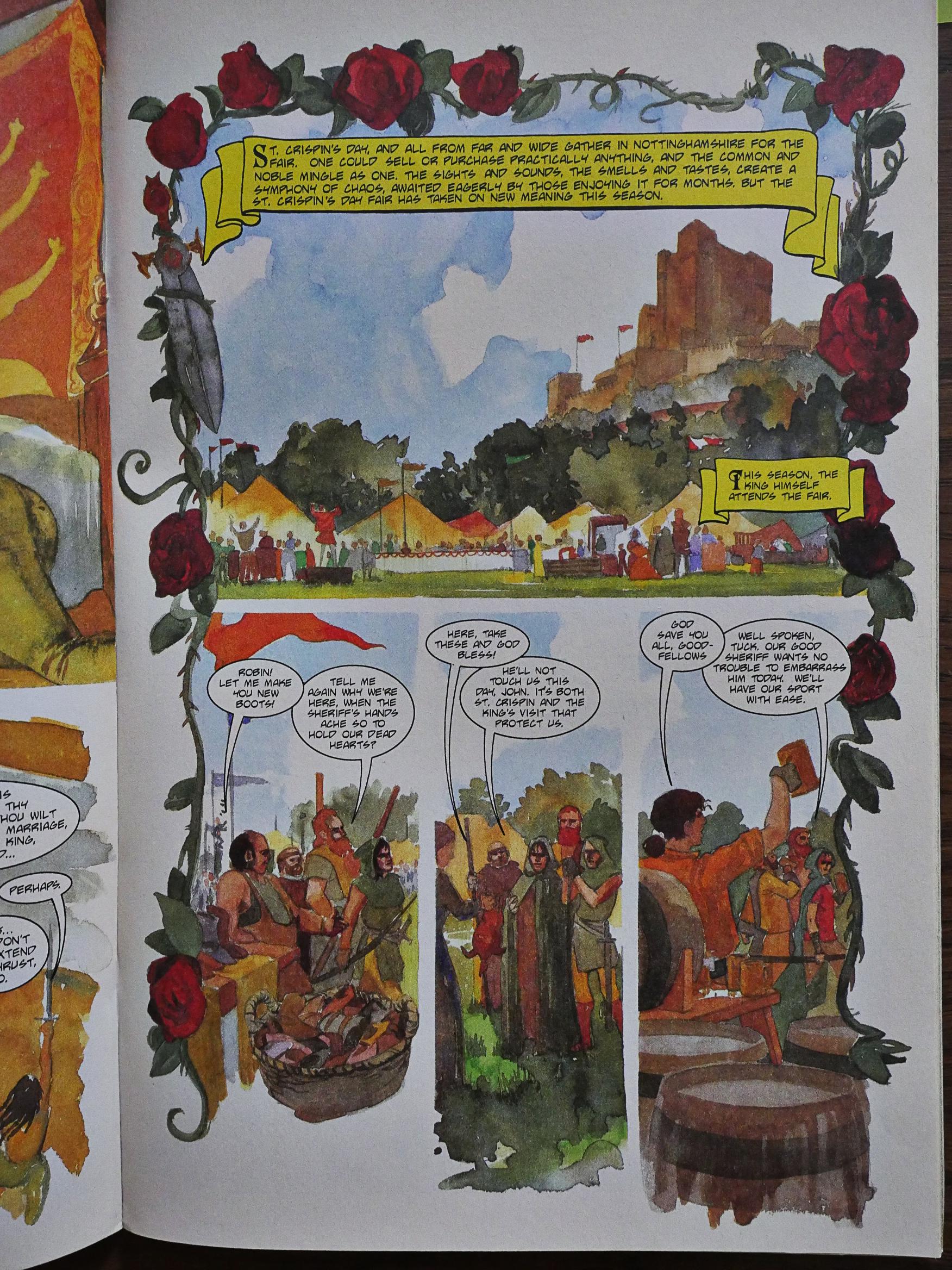

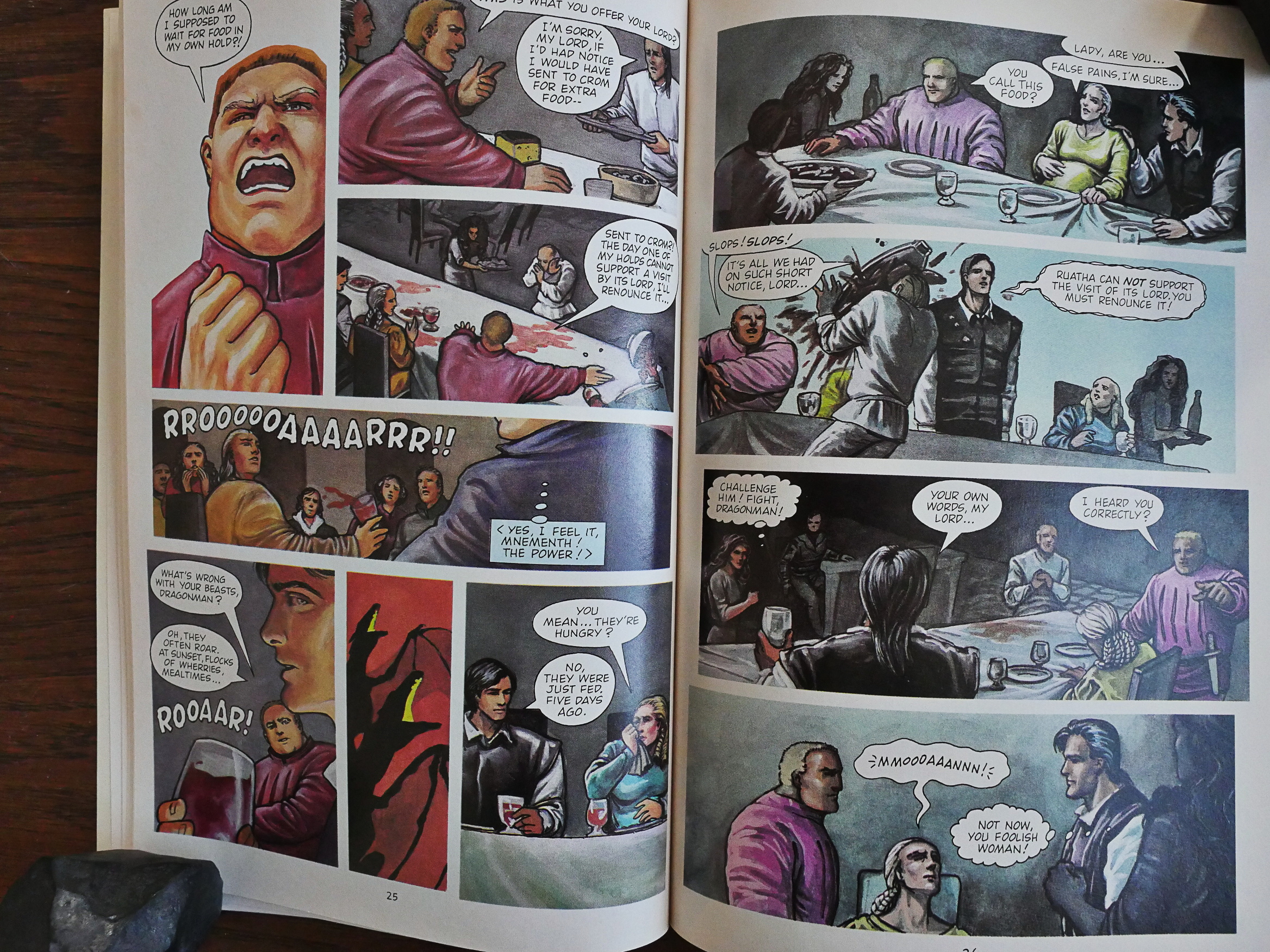

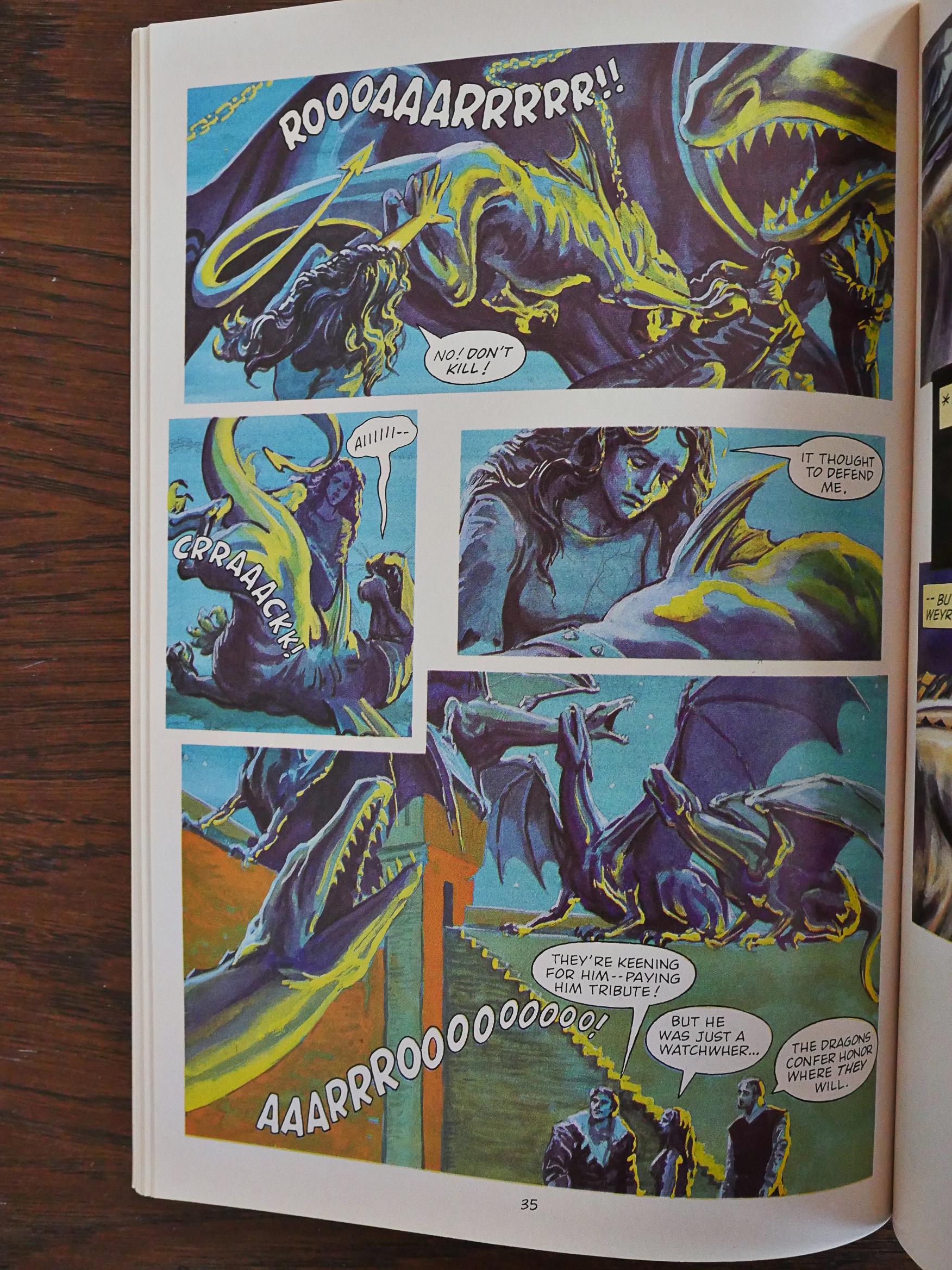

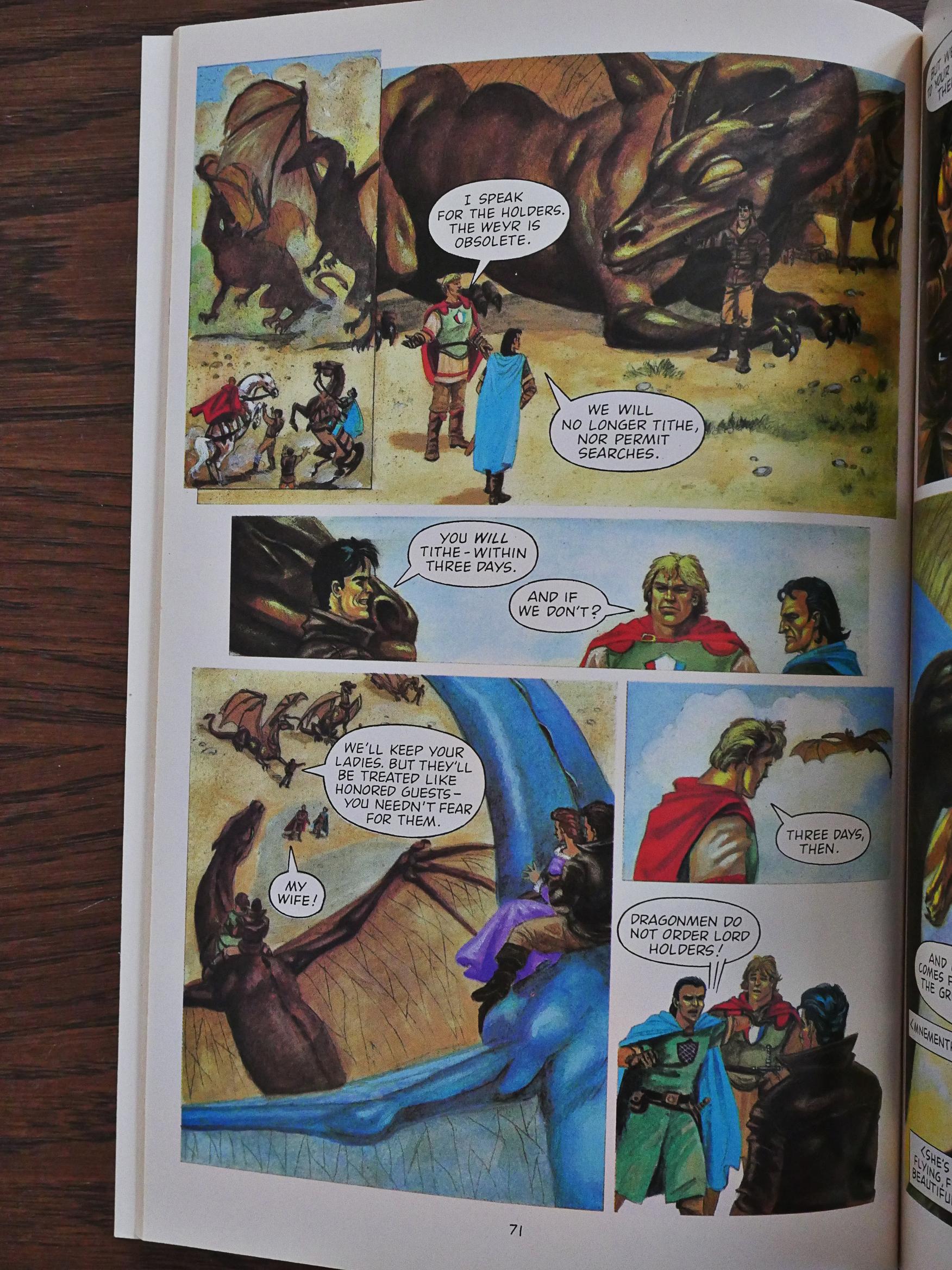

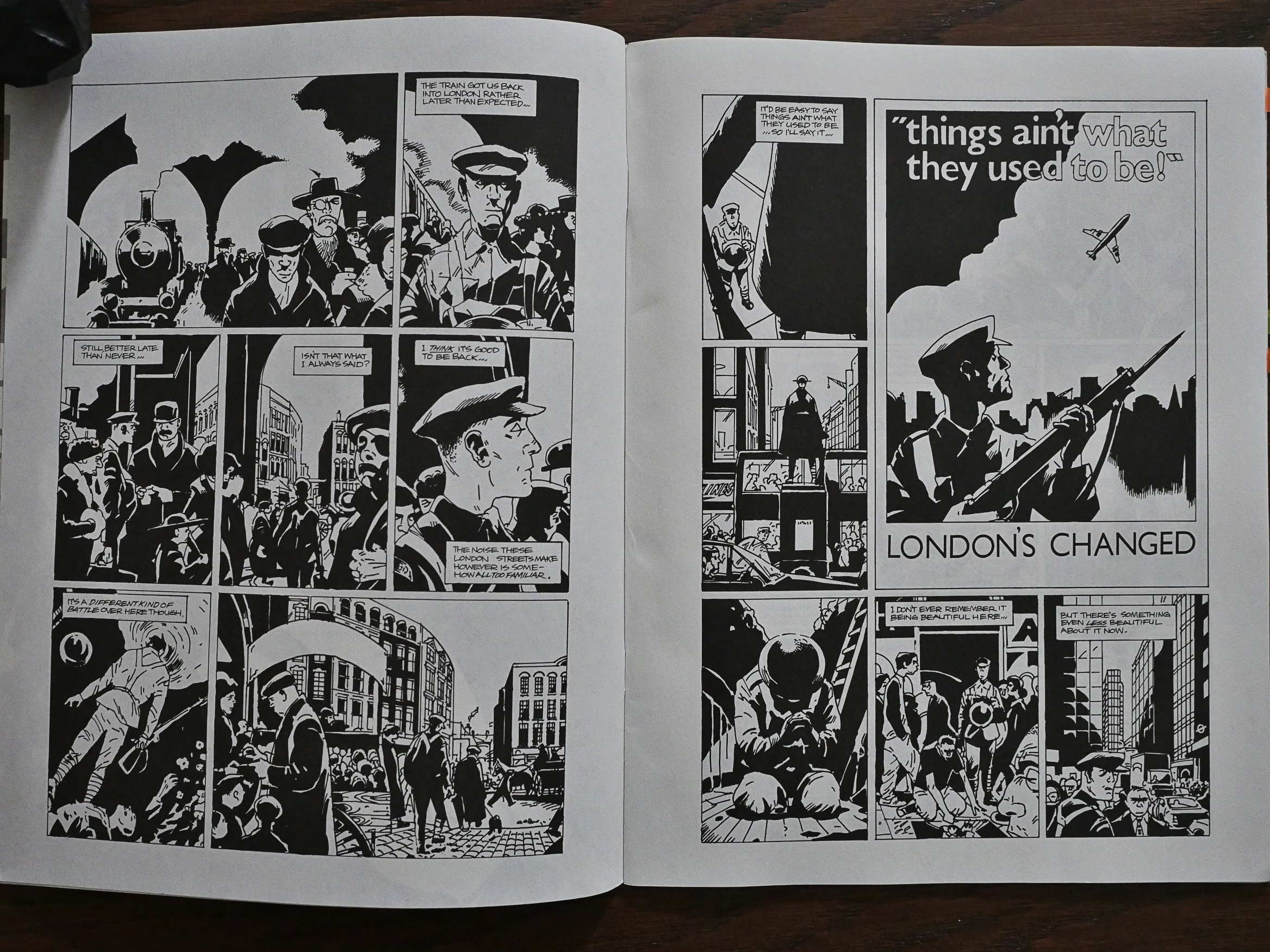

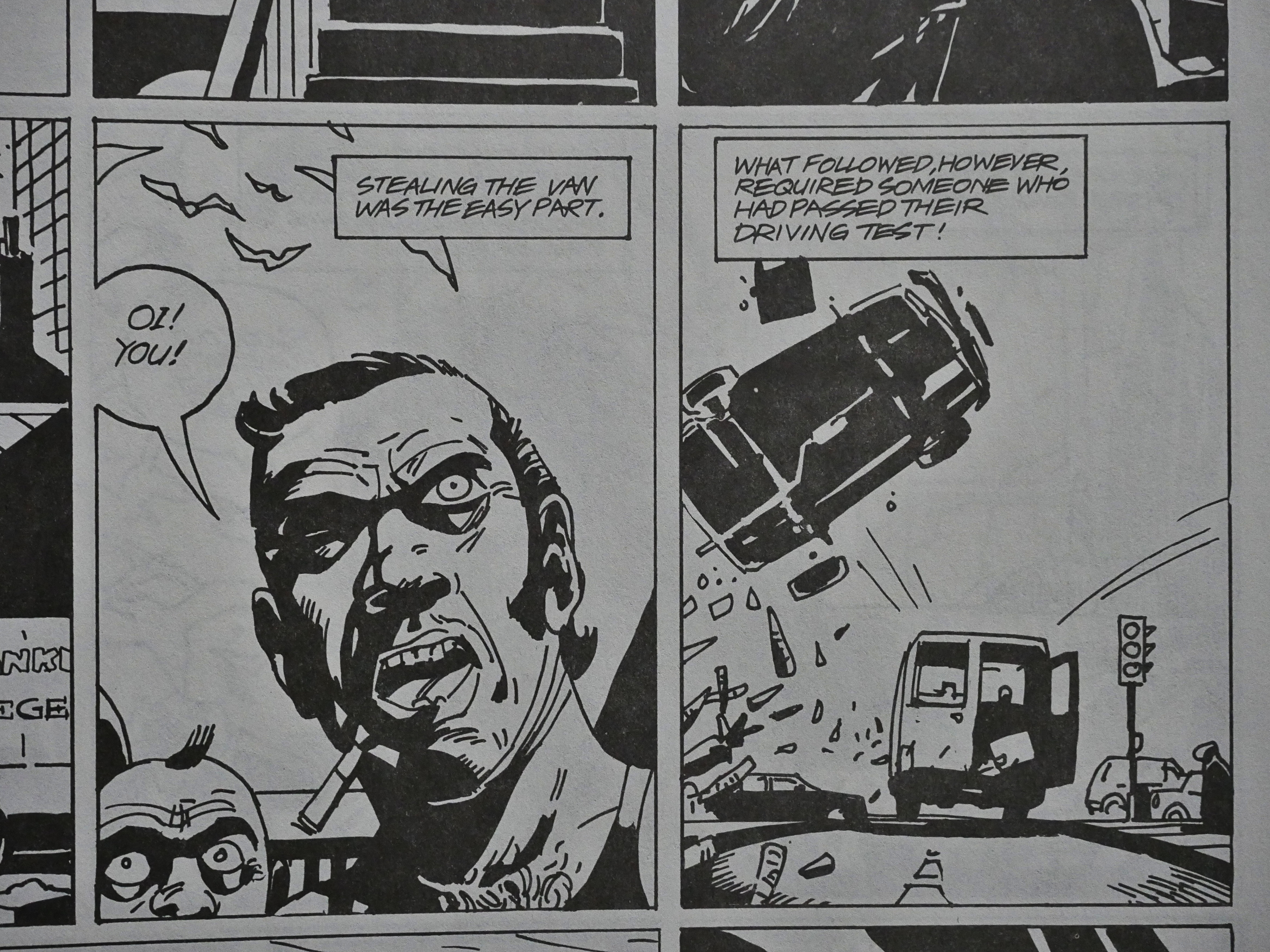

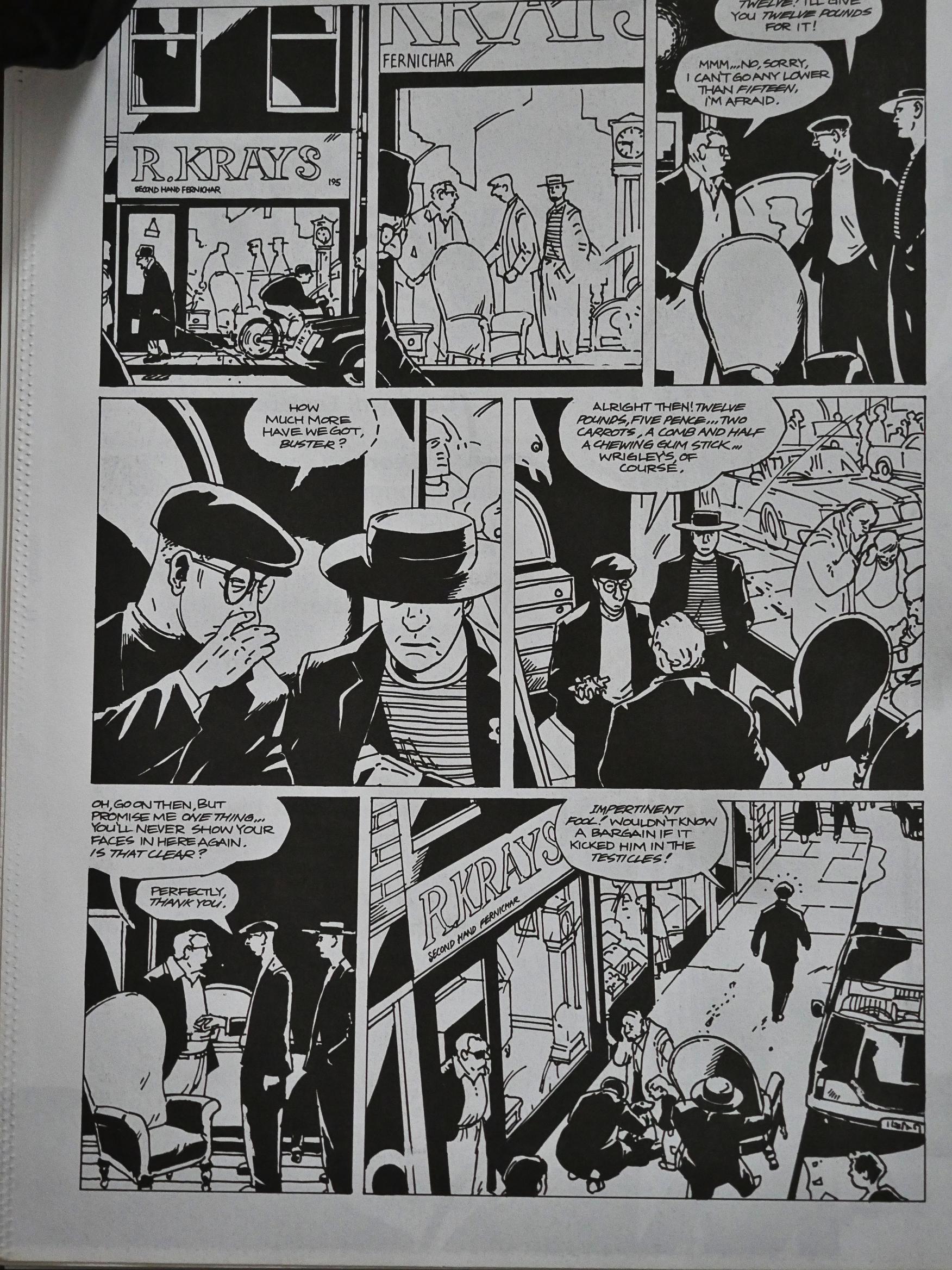

But it’s much messier and feels a lot more true to life than those films usually are. There’s a lot of back and forth in this book: Both literally (everybody moves between New York and Portland a lot, and those moves are depicted in the manner above, with a lots of tiny panels in a travel montage) and plot wise: Both David and Minnie (the central pair here) go through a bewildering number of breakups and reconciliations, and have a huge number of lovers.

Anyway, while the title of the book, and, well, the contents of the book would have you believe that this is autobiography, the indicia claims that it’s fiction, and that David Chelsea’s real name is David Celsi. So… perhaps that’s true?

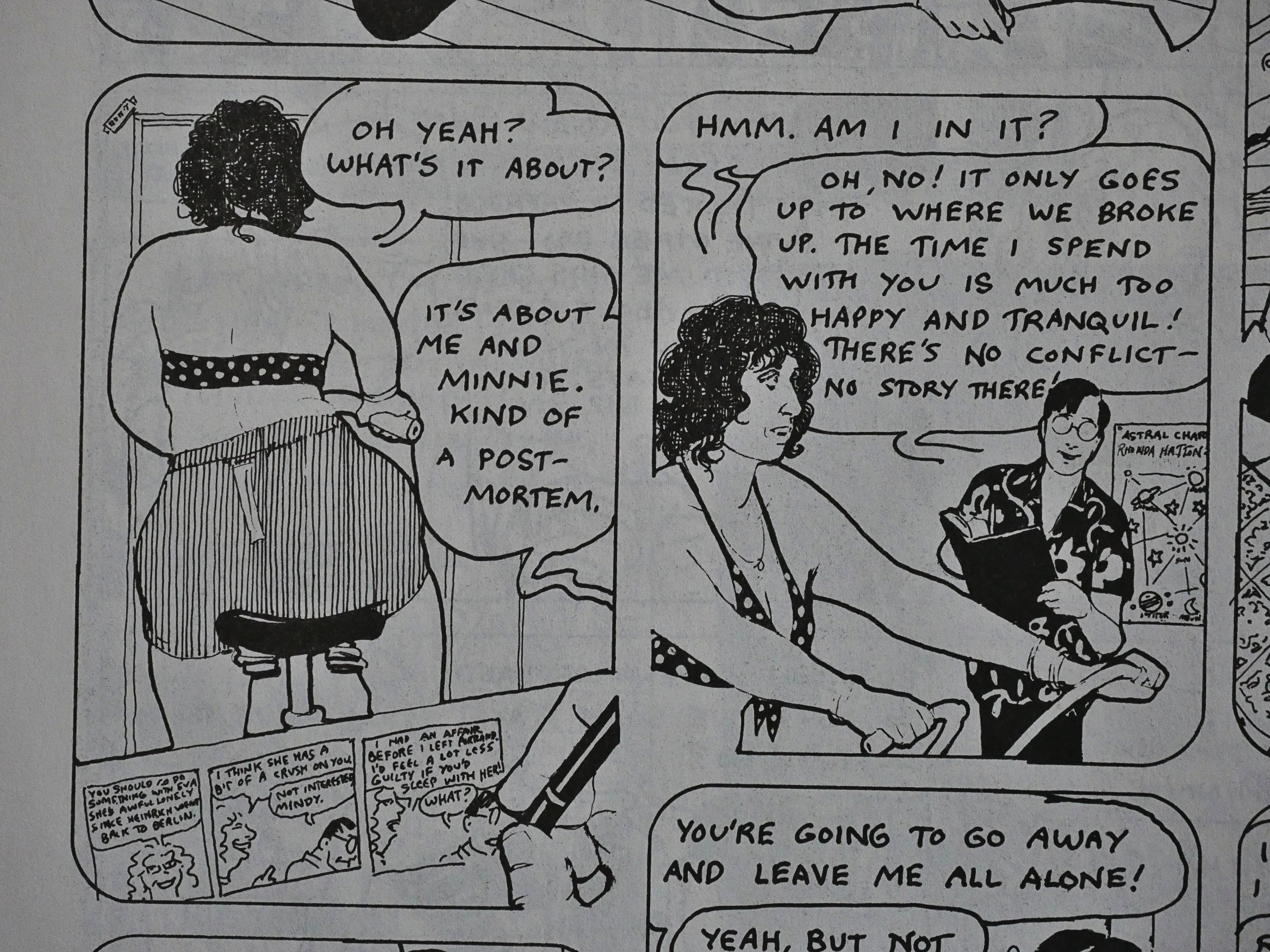

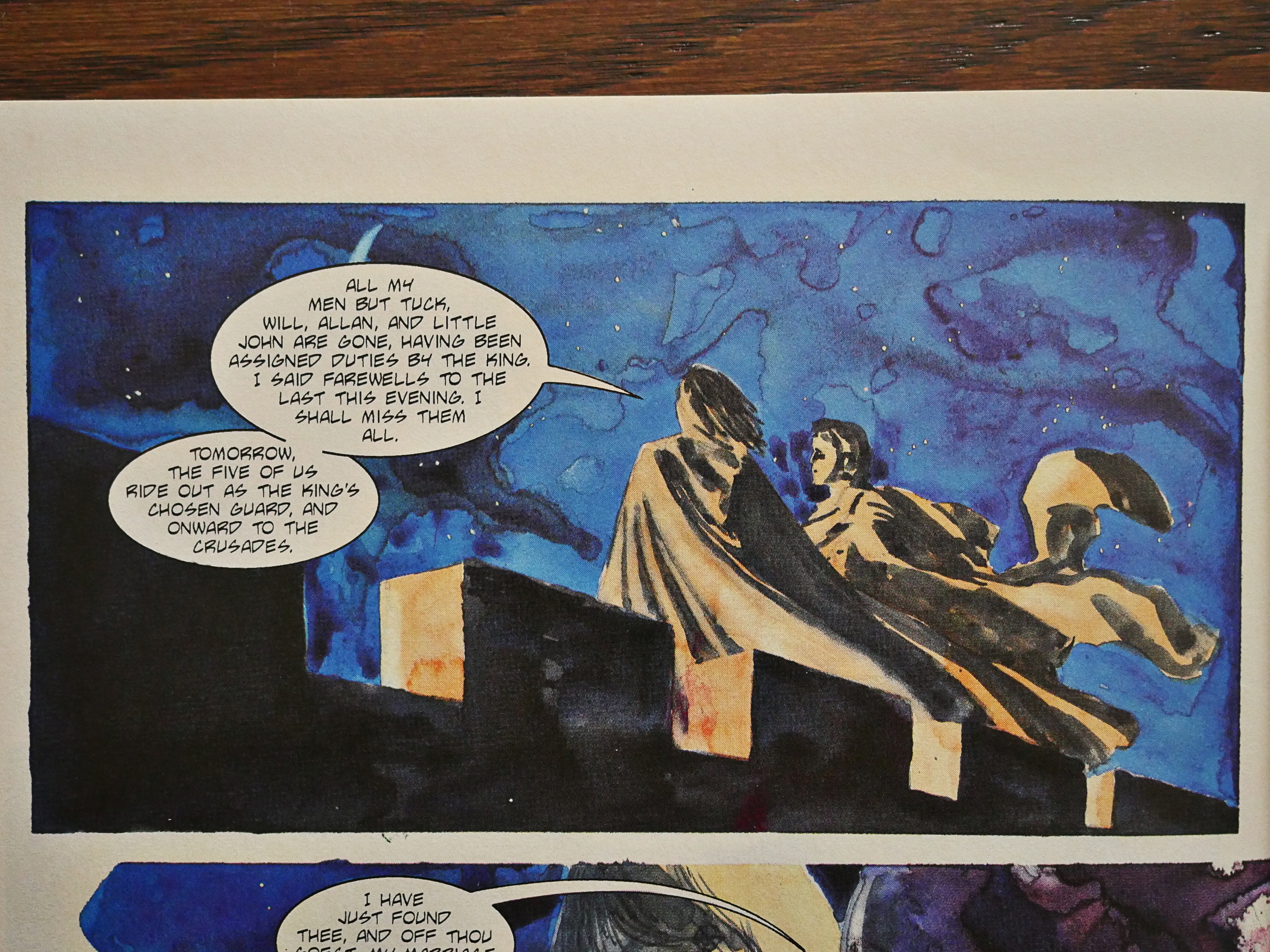

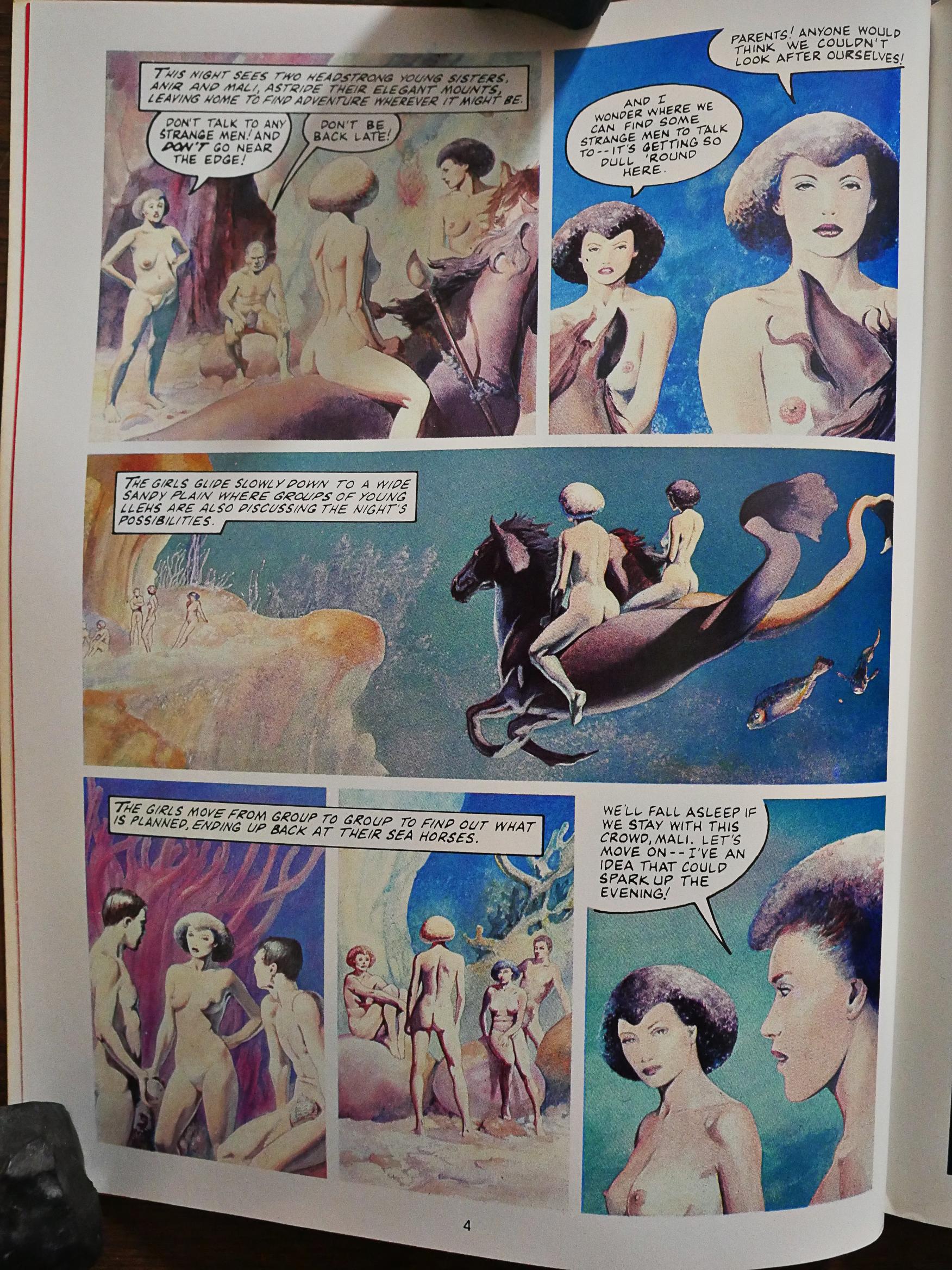

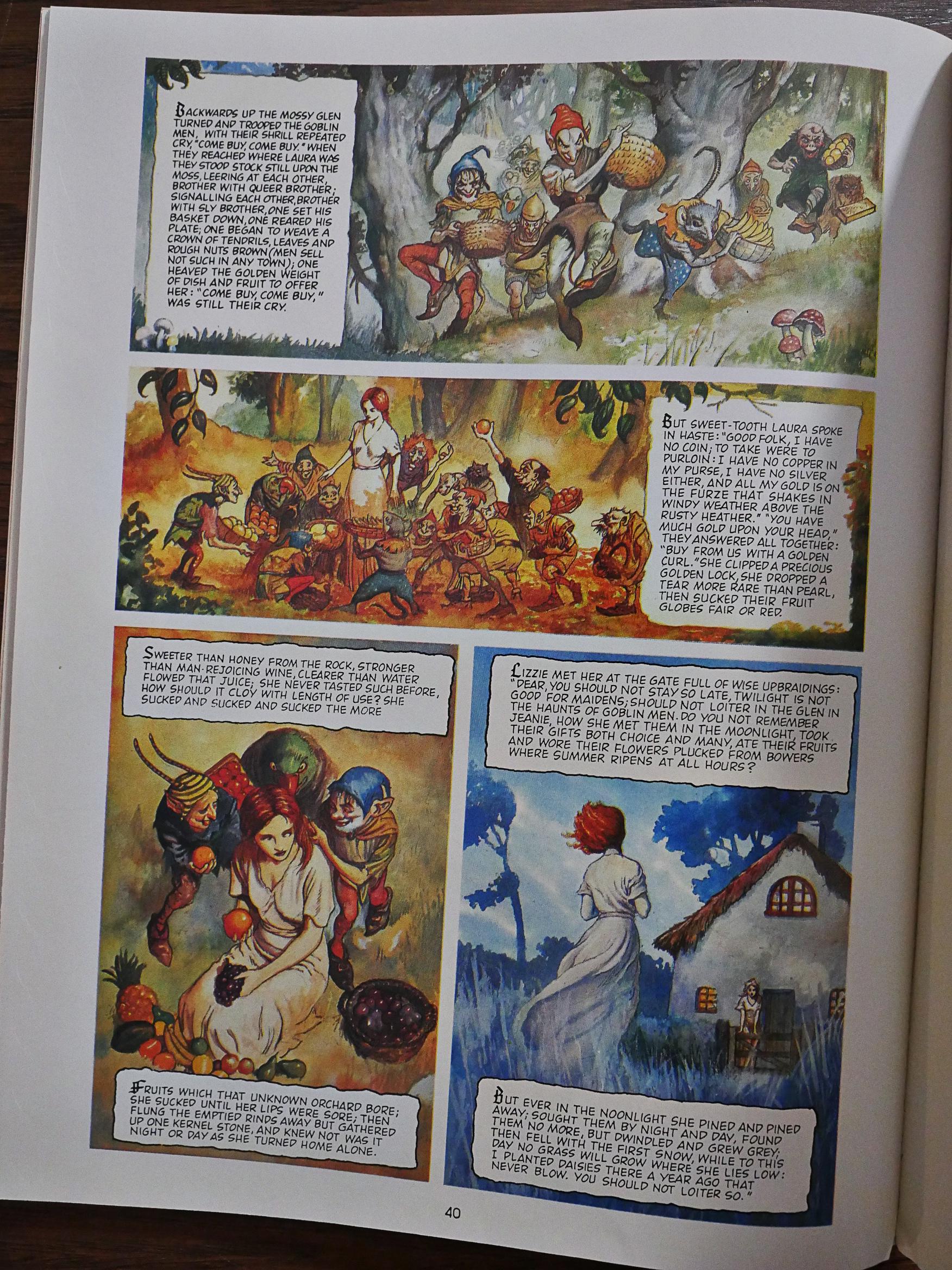

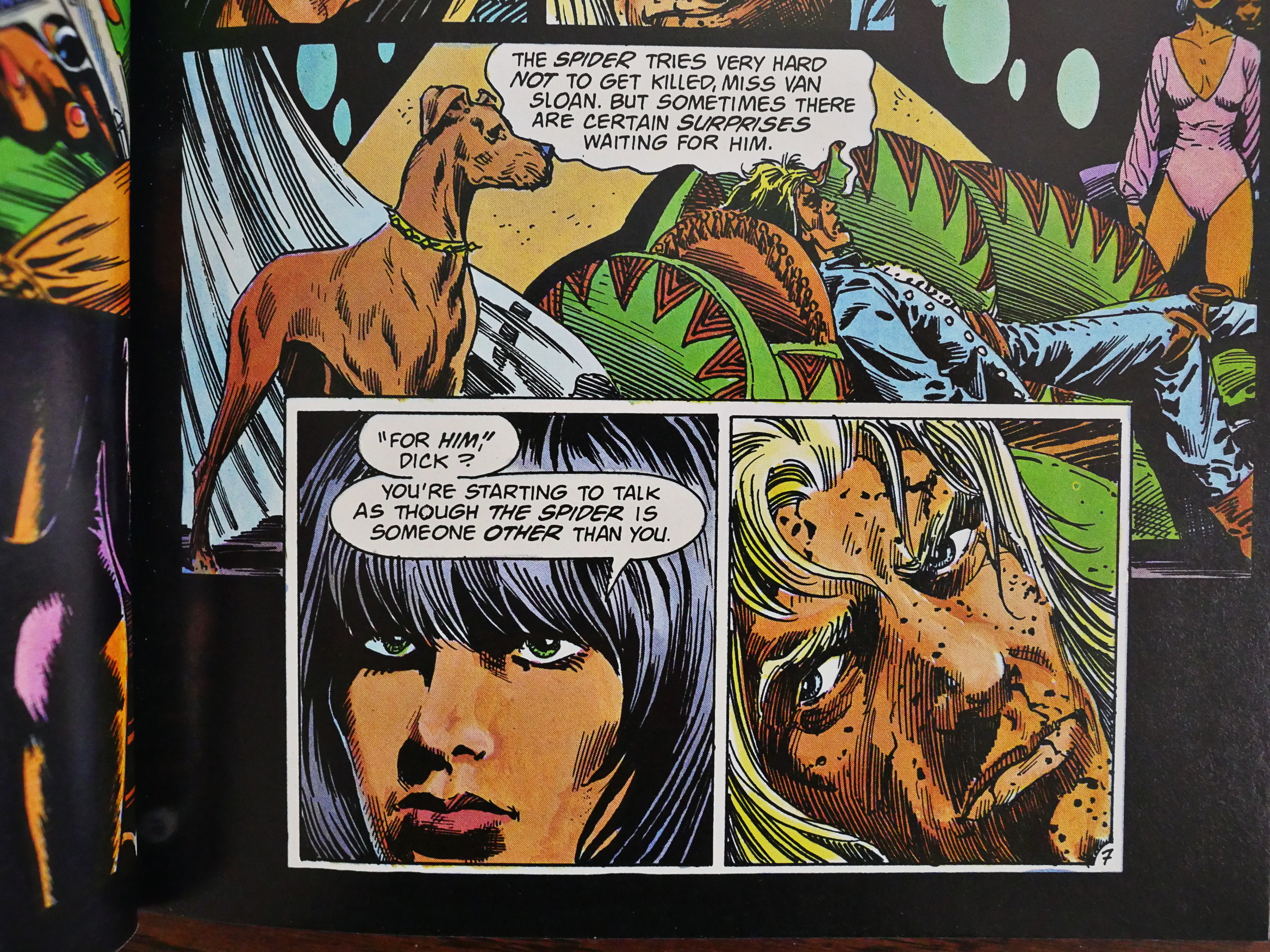

Chelsea does a number of fun layouts, some of which work better than others. The one above, for instance, with two of the panels being contiguous in space but not continuous in time is more distracting than anything else. I think it’s the panel to the bottom left that makes of read kinda wonkily.

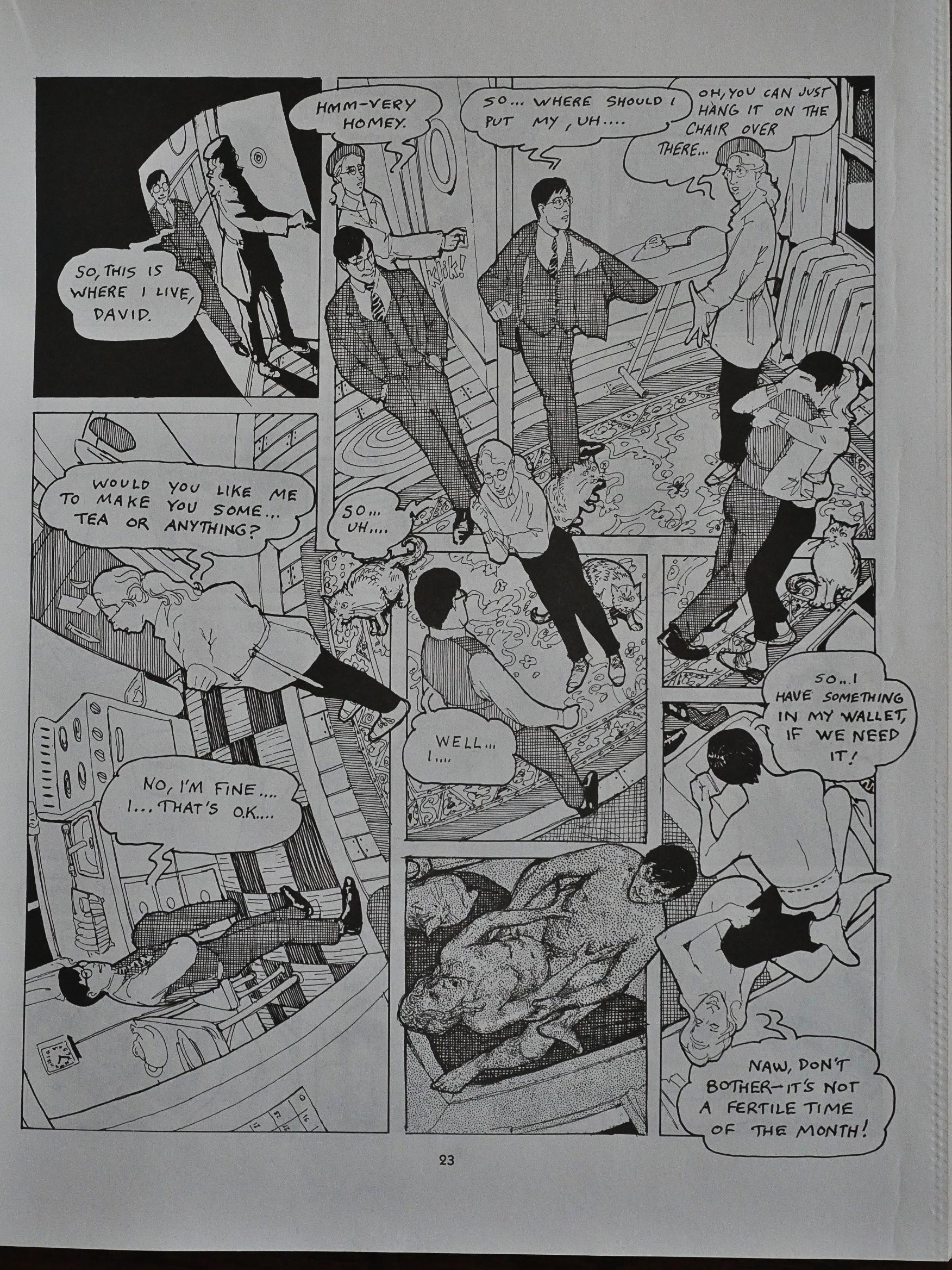

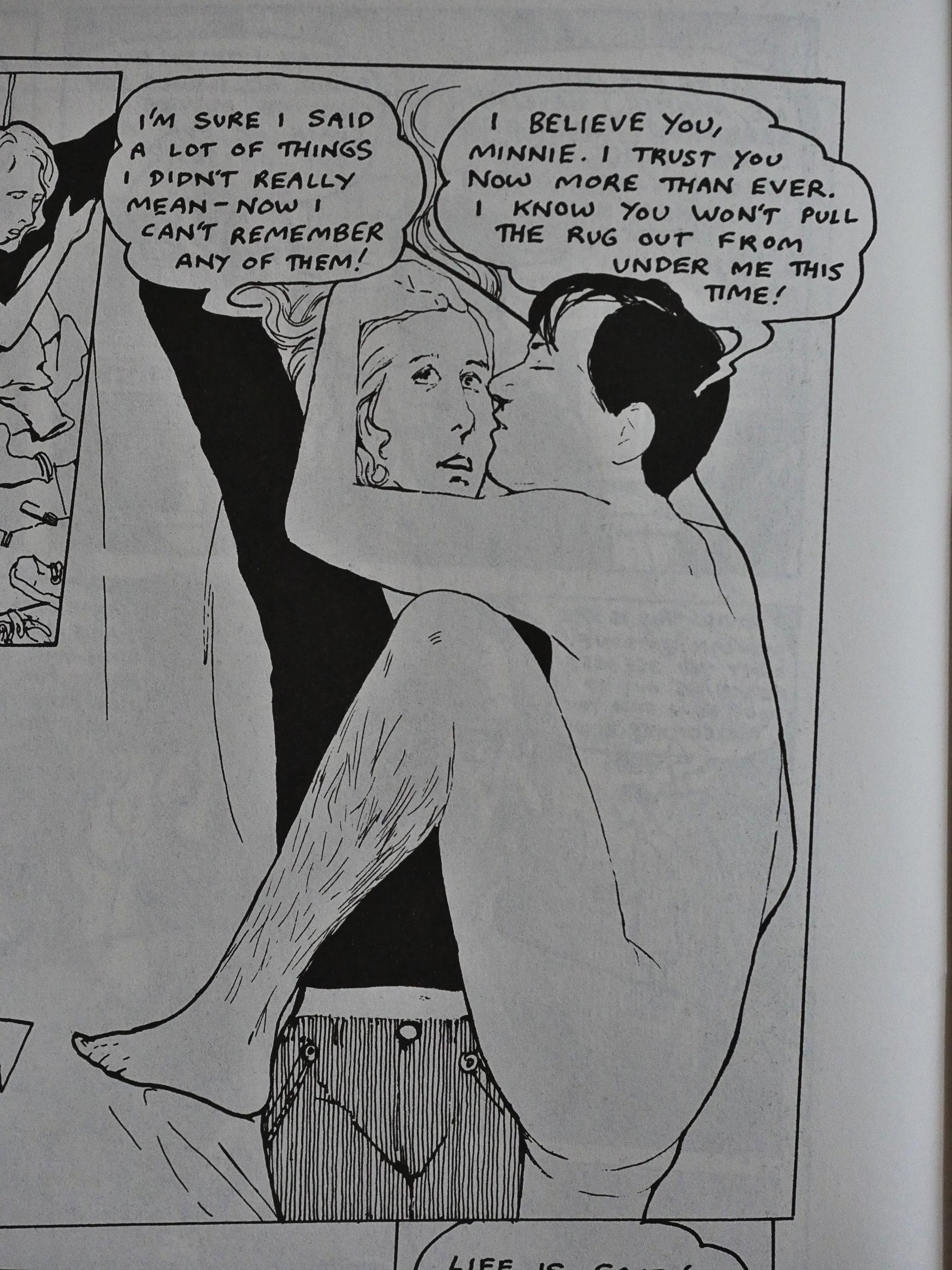

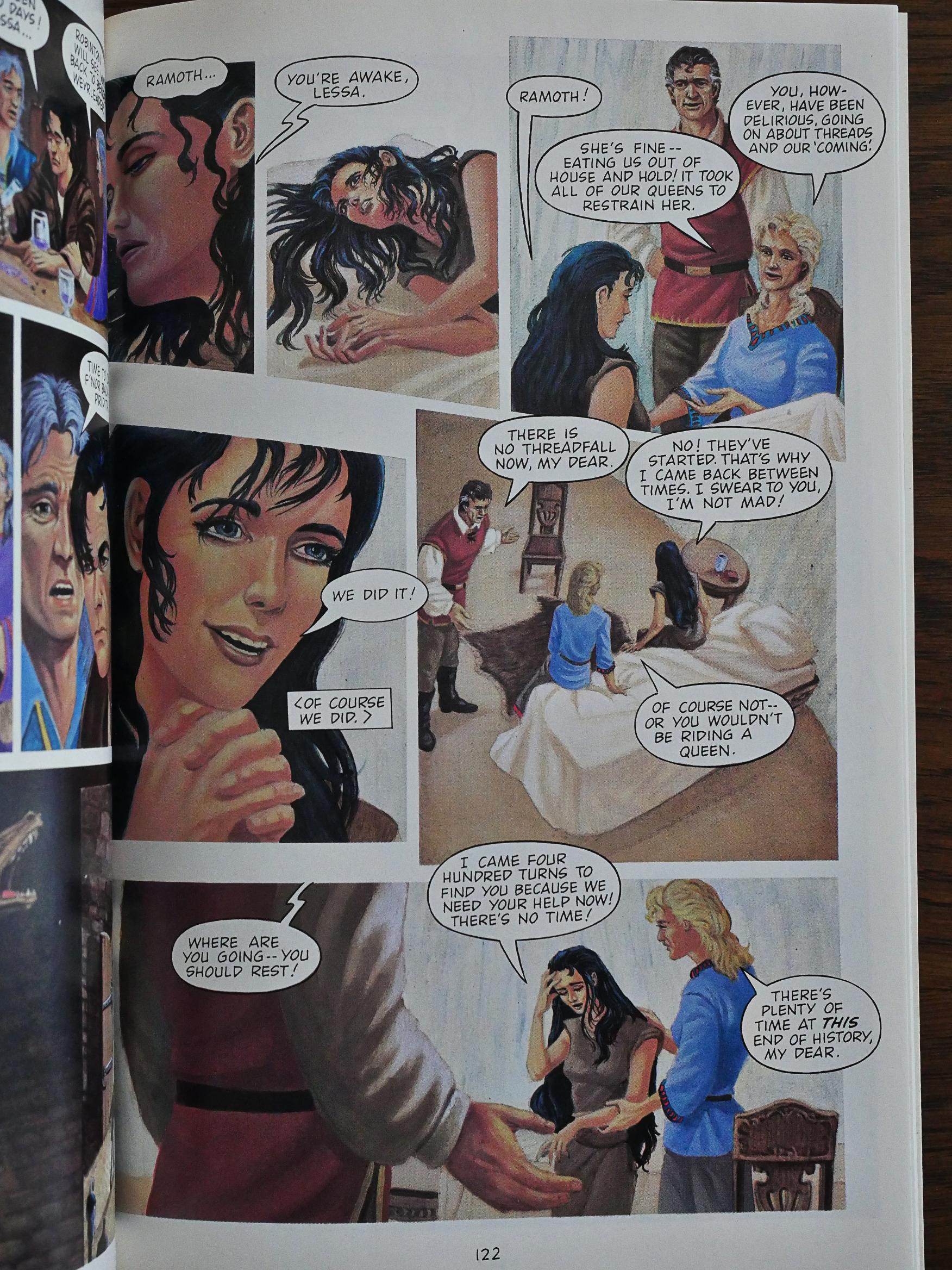

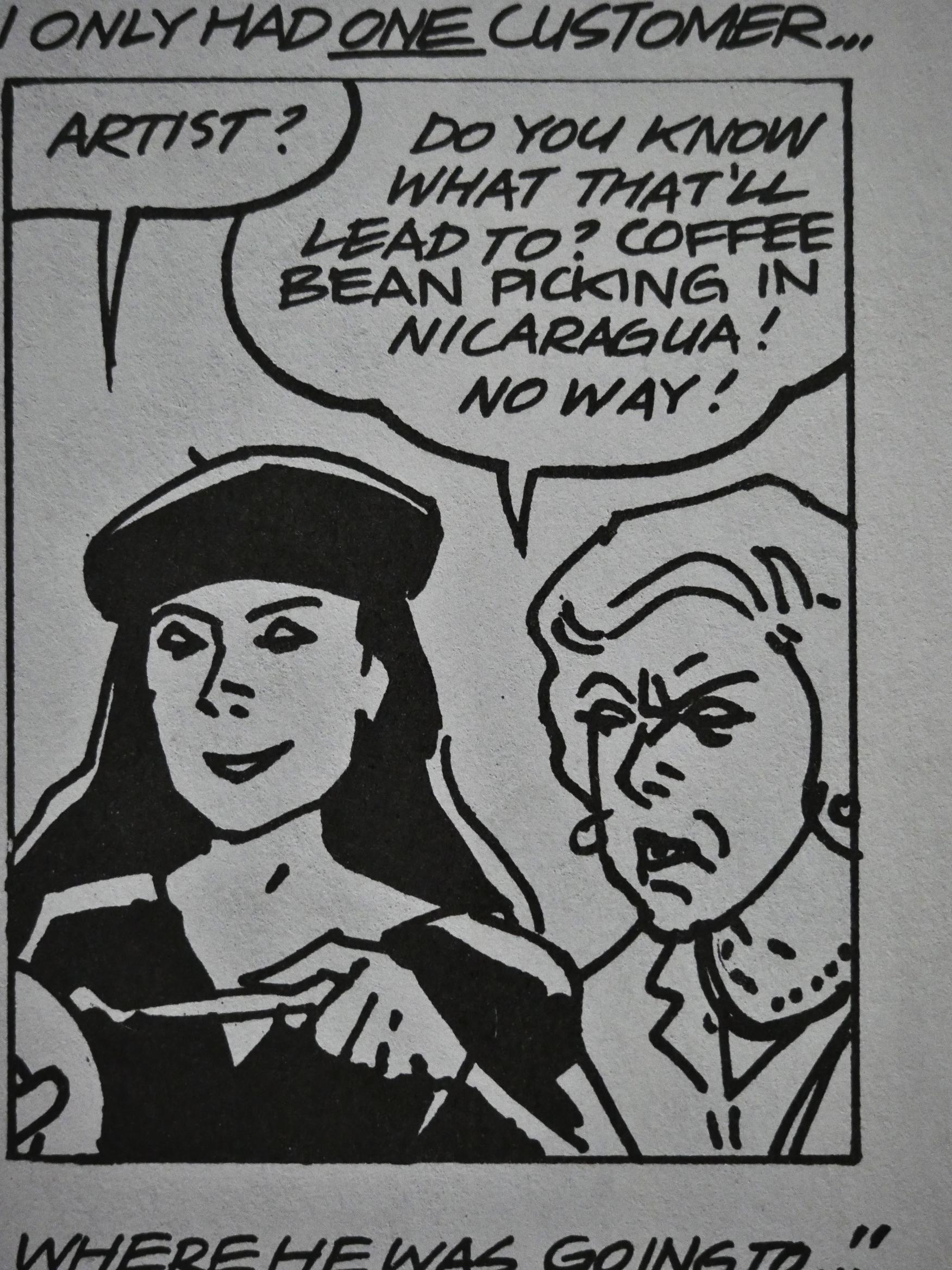

Other layouts work a lot better, like above, where David and Minnie get together in Minnie’s apartment for the first time. The dizzying layout reflects and enhances the characters’ giddiness. It’s kinda perfect in its confusion.

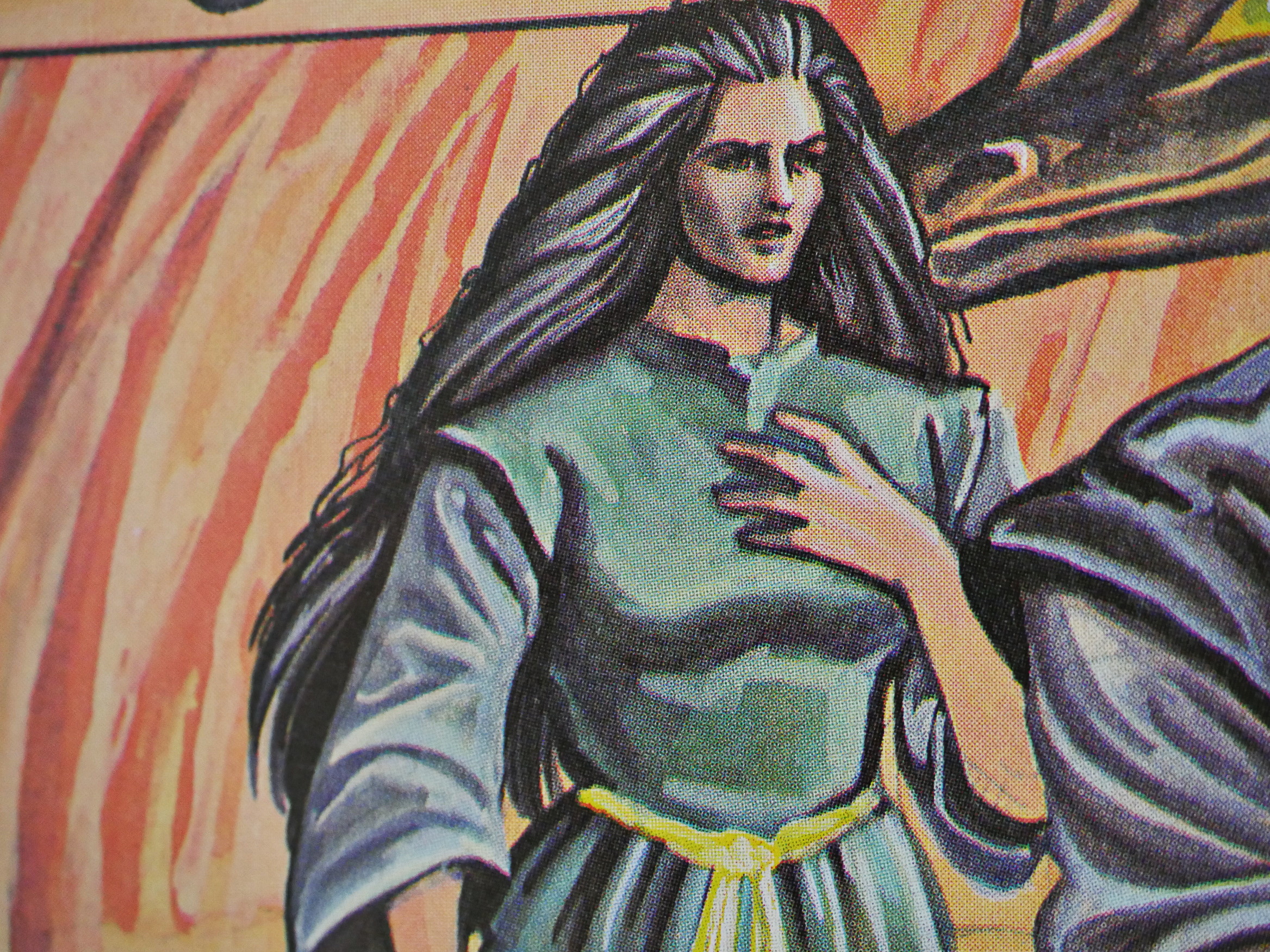

This four part series, 48 pages each, magazine size, is all about love and stuff. And the sweet stuff is really, really sweet.

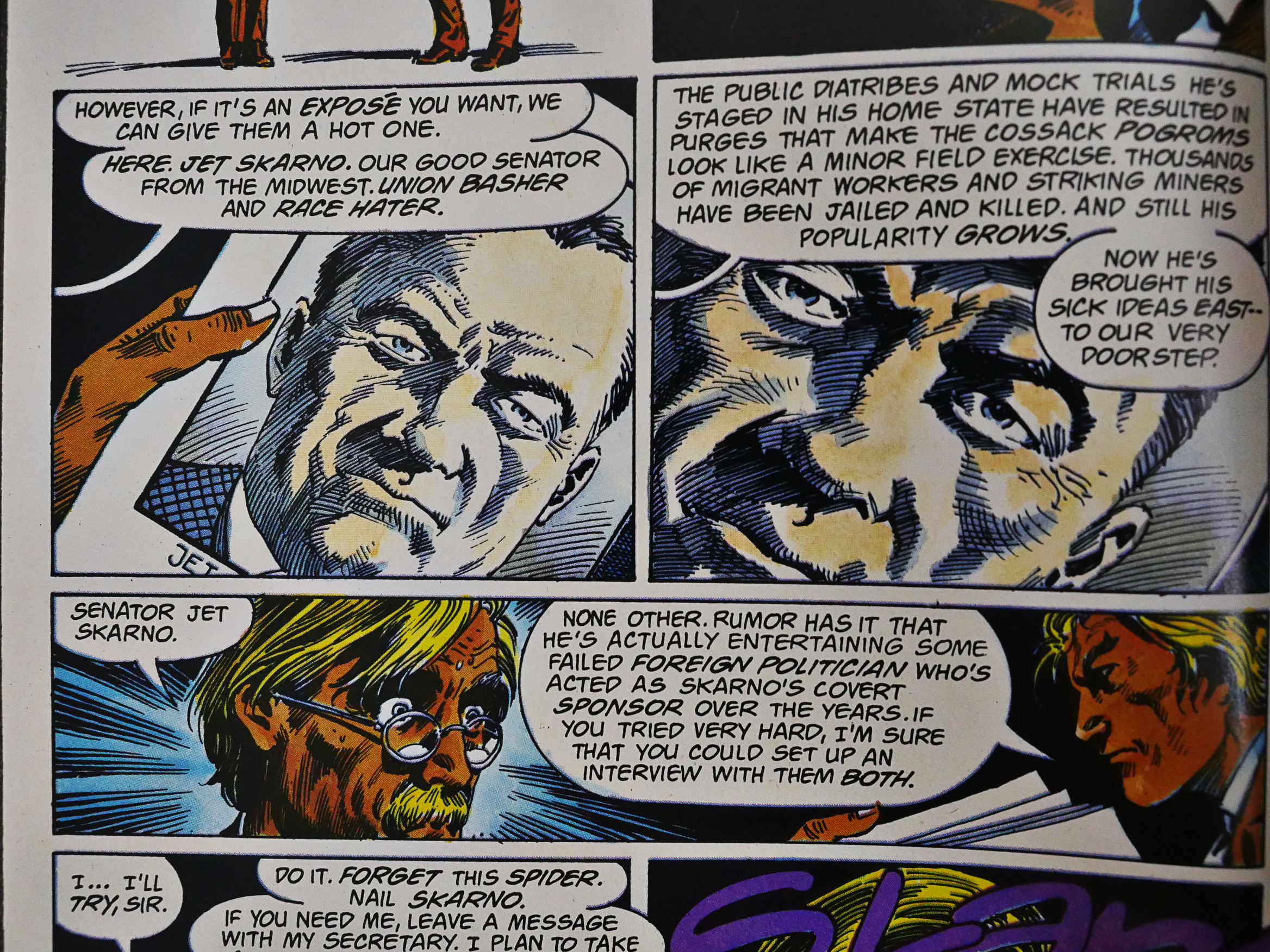

Chelsea helpfully provides a recap page in the second issue, which is basically exactly the way a daytime soap would have recapped the plot. Which is also very appropriate, because Chelsea spends an unhealthy amount of time watching soaps.

For the third issue recap, Chelsea goes for a totally different approach, with the characters selfconsciously tell the readers what’s up.

I really like these travel montages. They also tell us how the time is passing. The preceding montage had the inauguration of Ronald Reagan, while this one has an even more important event: Raw magazine #3, which tells us that we’re in 1981. Good to be clear!

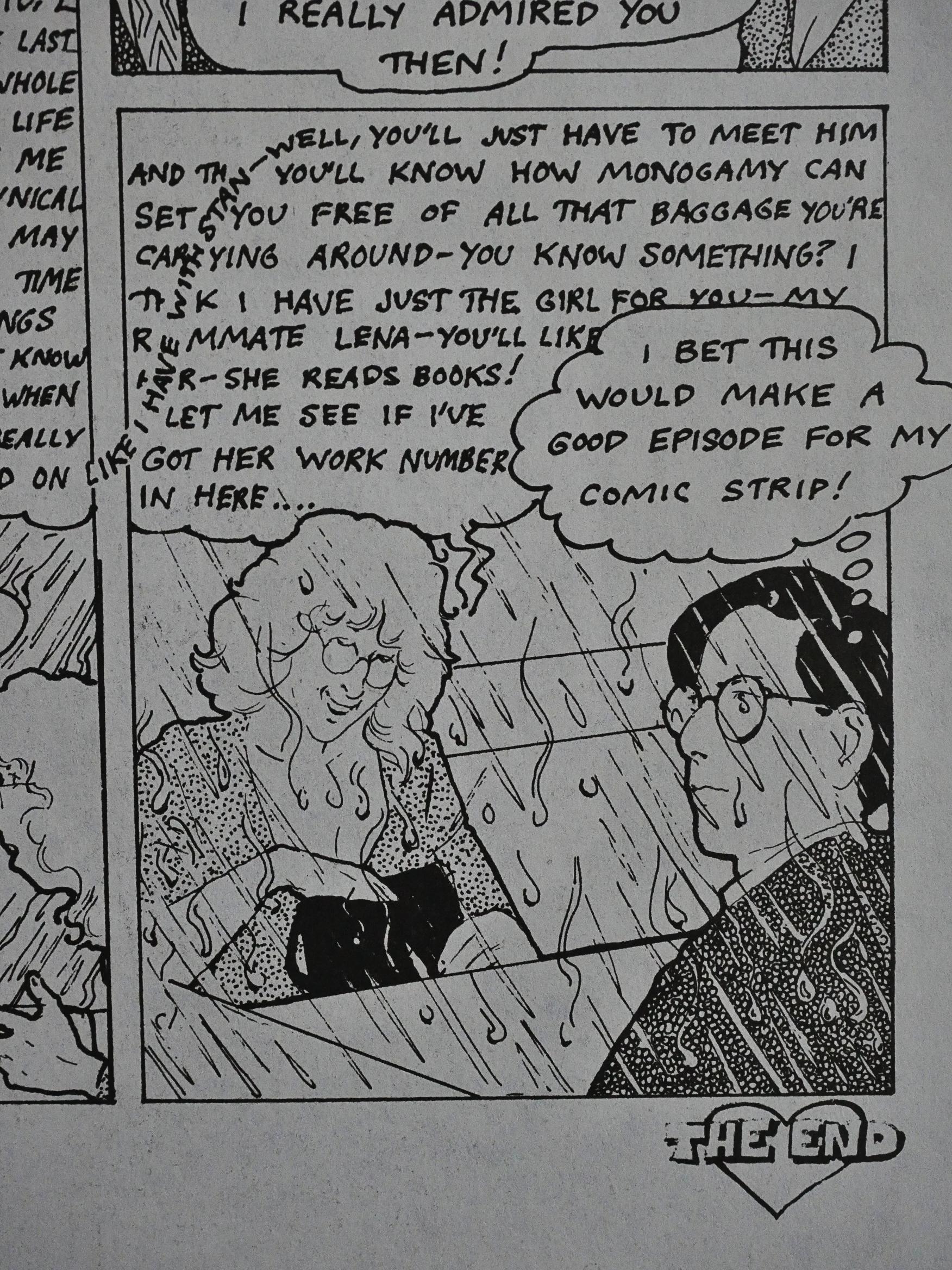

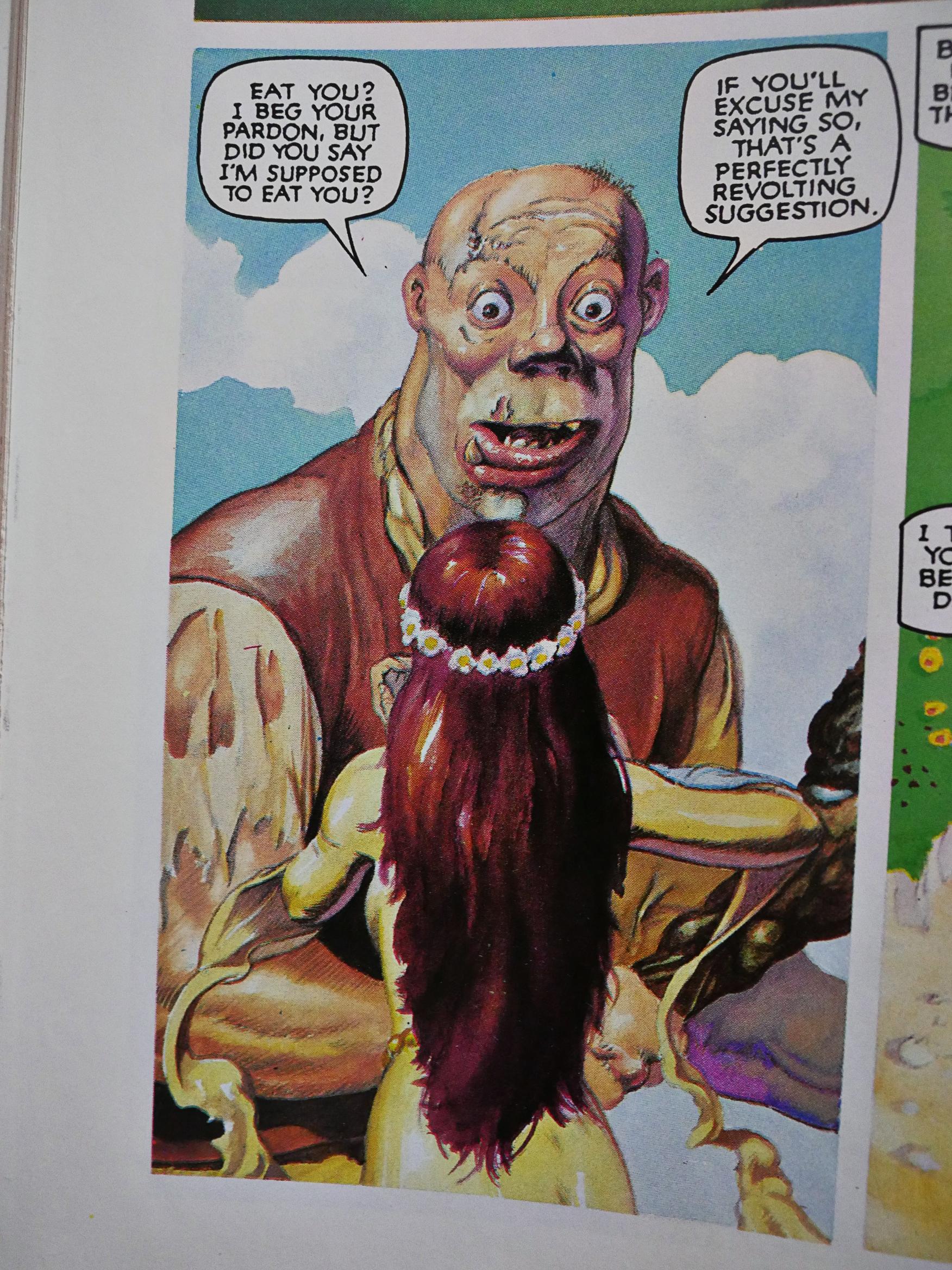

Did I mention that this is also a funny book? It’s a funny book.

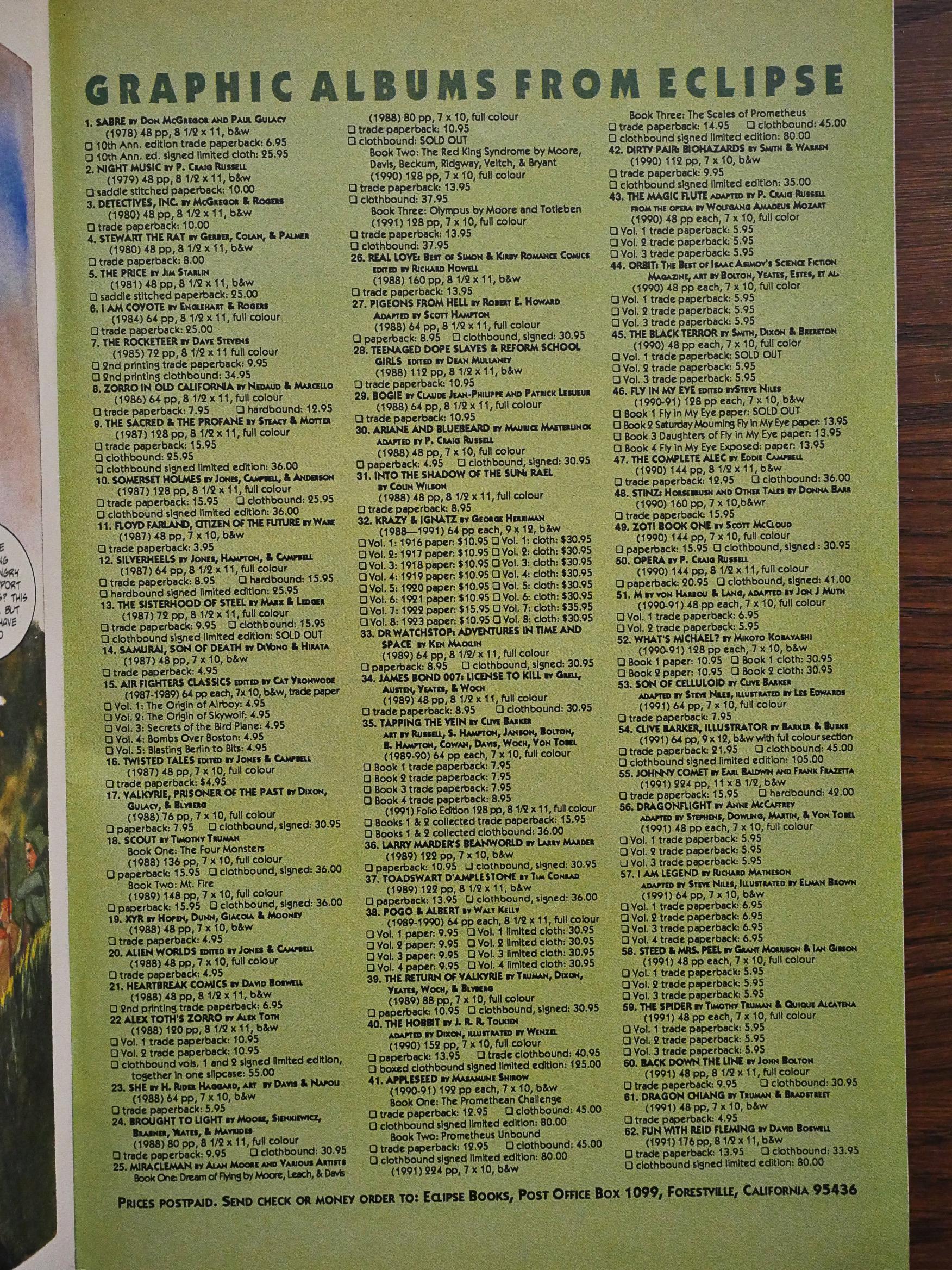

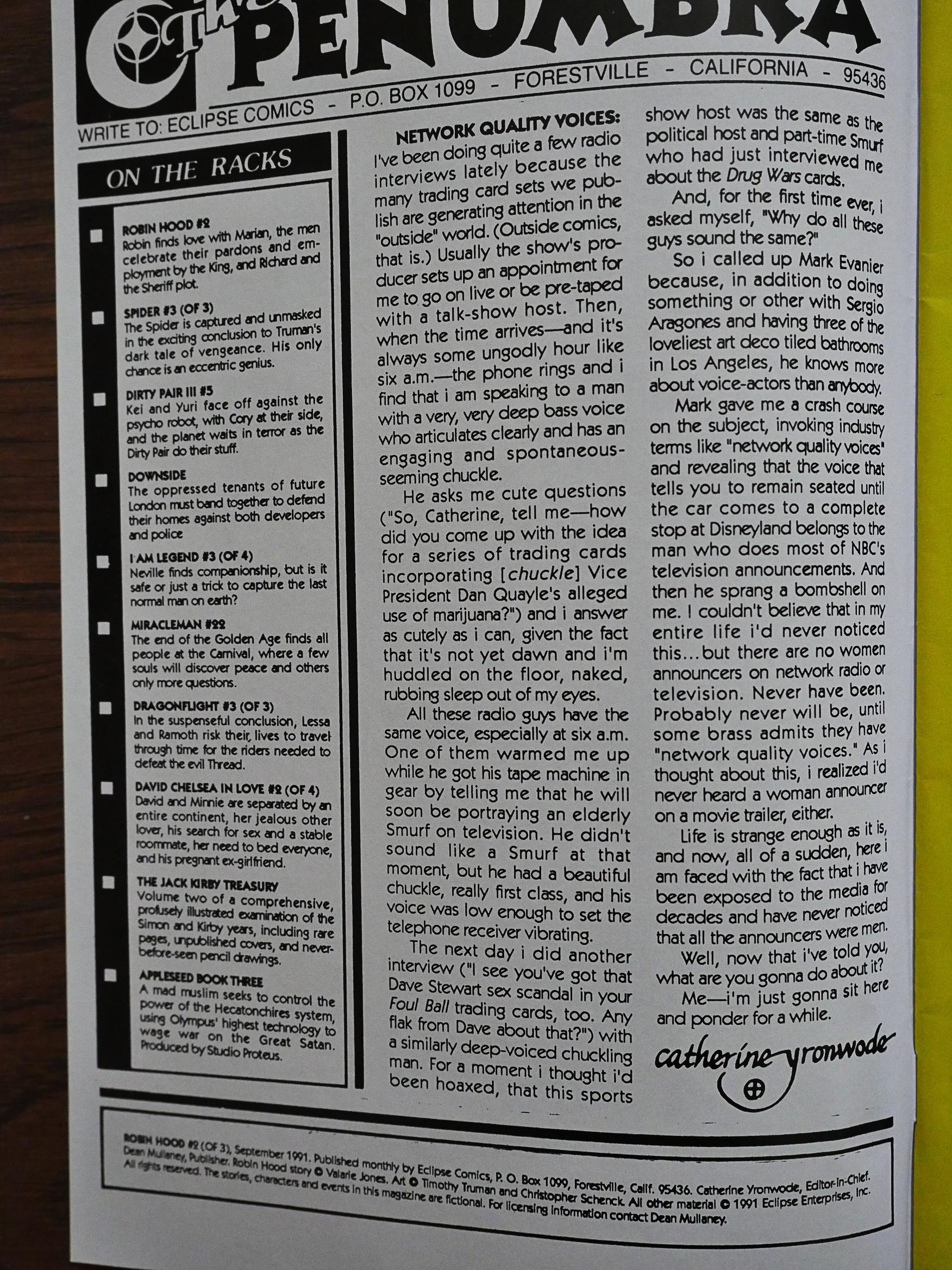

Editor cat yronwode writes one page about Eclipse’s publishing strategy: Publishing Kill-Man Comics pays the bills which enables them to publish comics like this, and she also gets a dig in at Fantagraphics, who had just started the Eros line of comics of “lowest-common-denominator line of impersonal and fetish-oriented pornography”. Which is pretty accurate. (She slyly doesn’t actually name Fantagraphics.) All part of the long-running simmering feud between these companies, I guess…

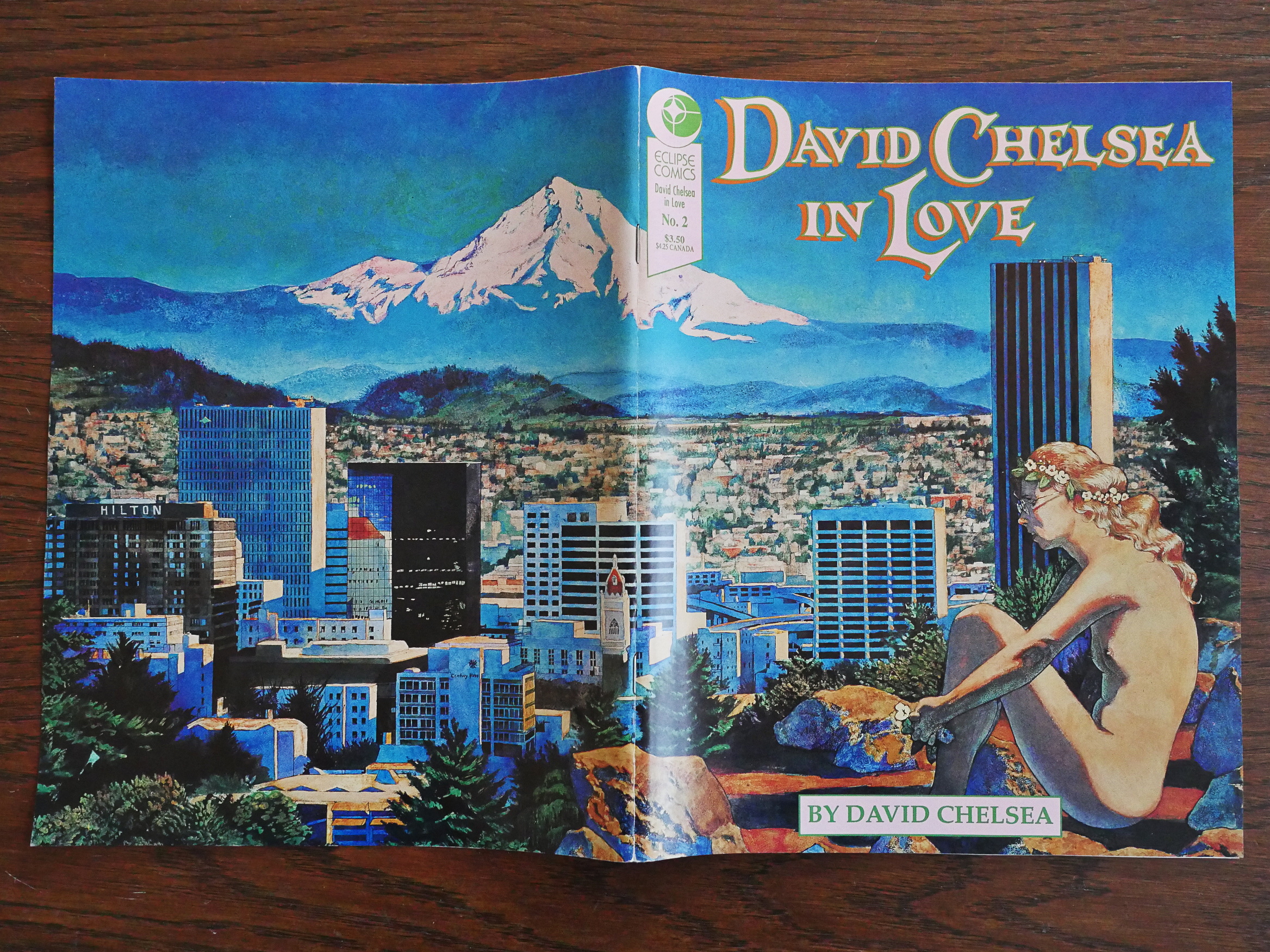

Chelsea does one double page cover, and very nice it is, too.

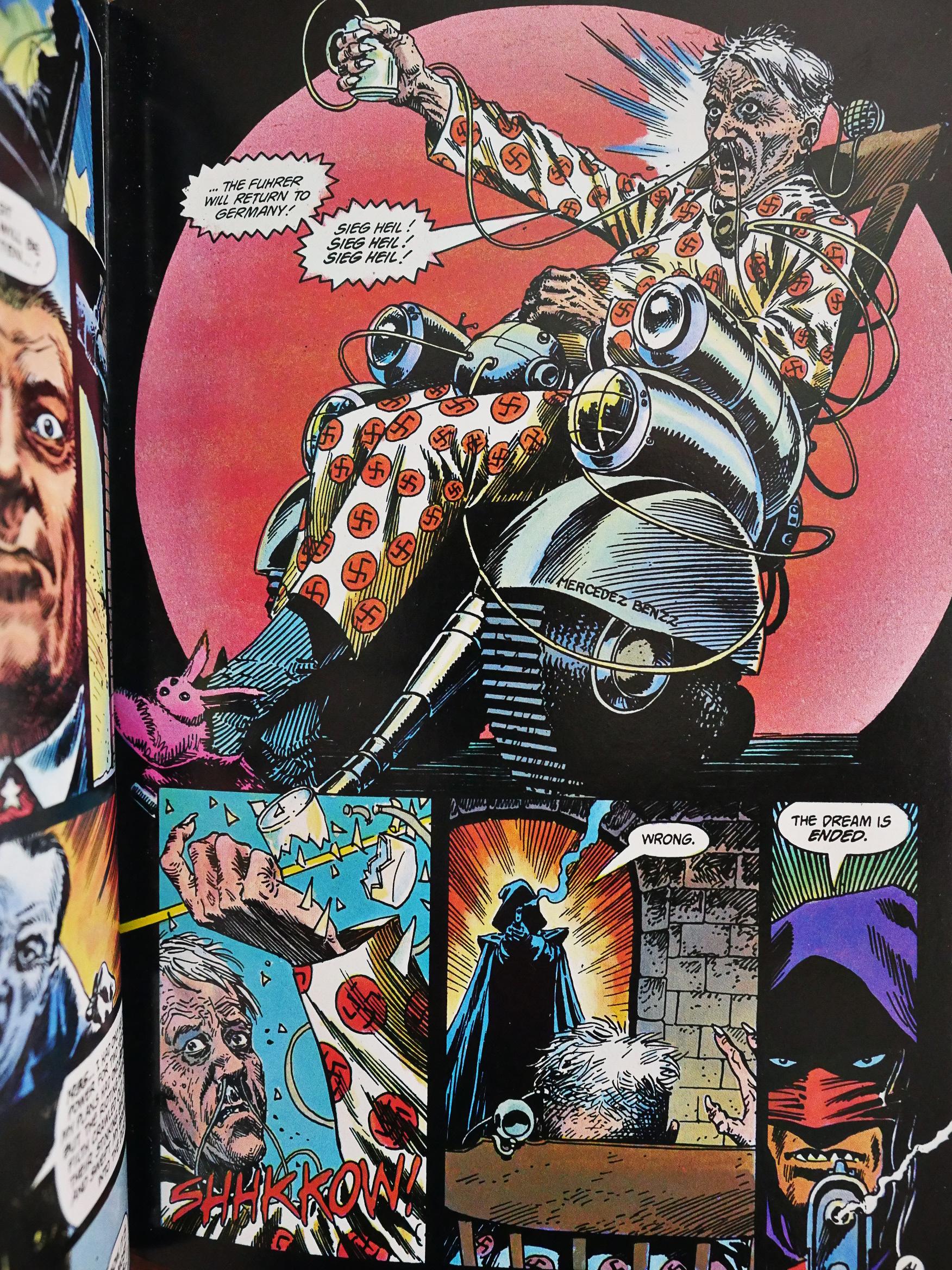

As we get closer to the end, the book becomes somewhat self-reflective. Chelsea’s started drawing this comic (or its predecessor), so naturally everybody around him starts getting antsy about being in the story or not.

Heh. A reference to the Yoko Ono/John Lennon picture by Annie Leibowitz. Could this be foreshadowing?!

Indeed.

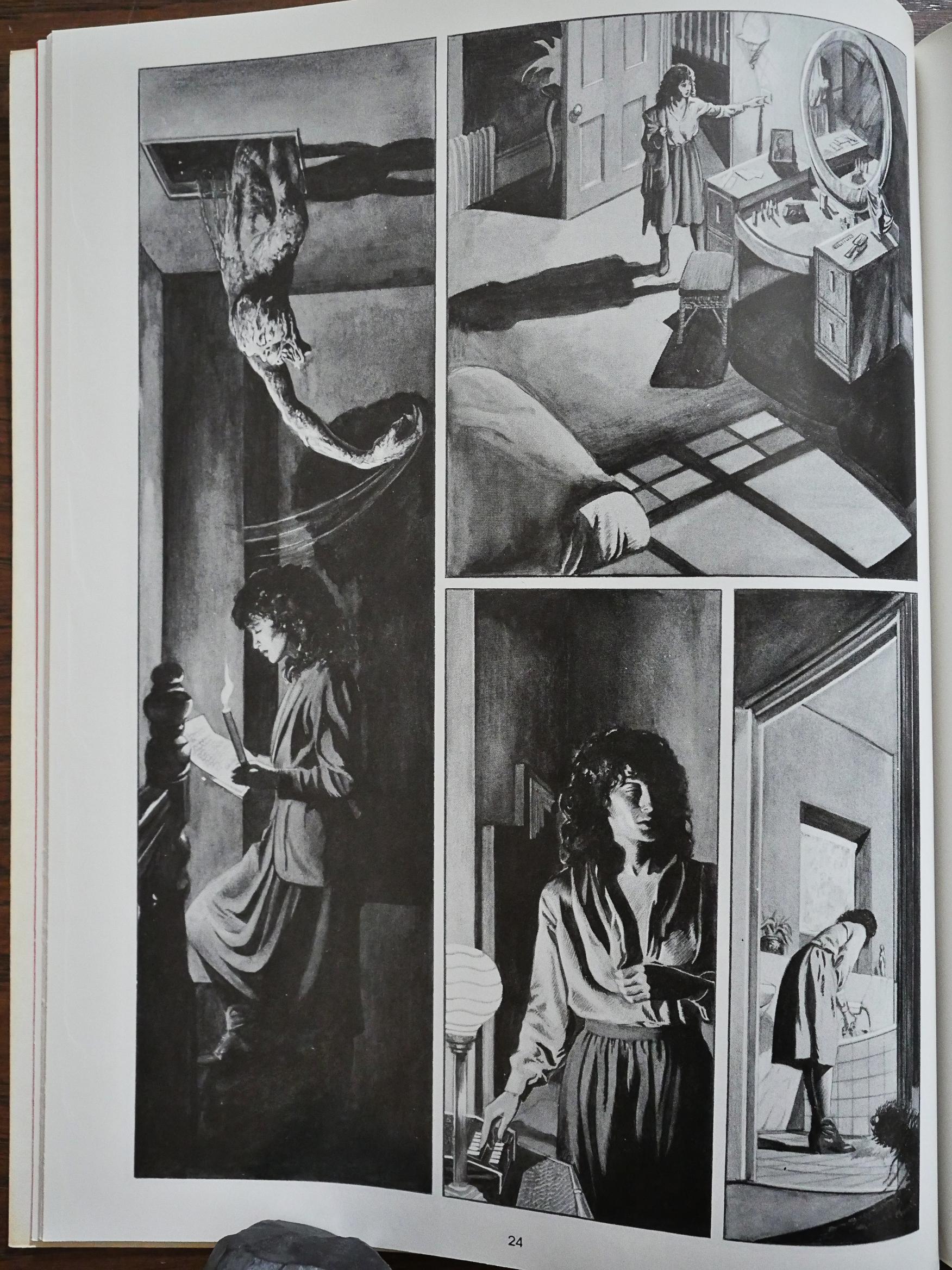

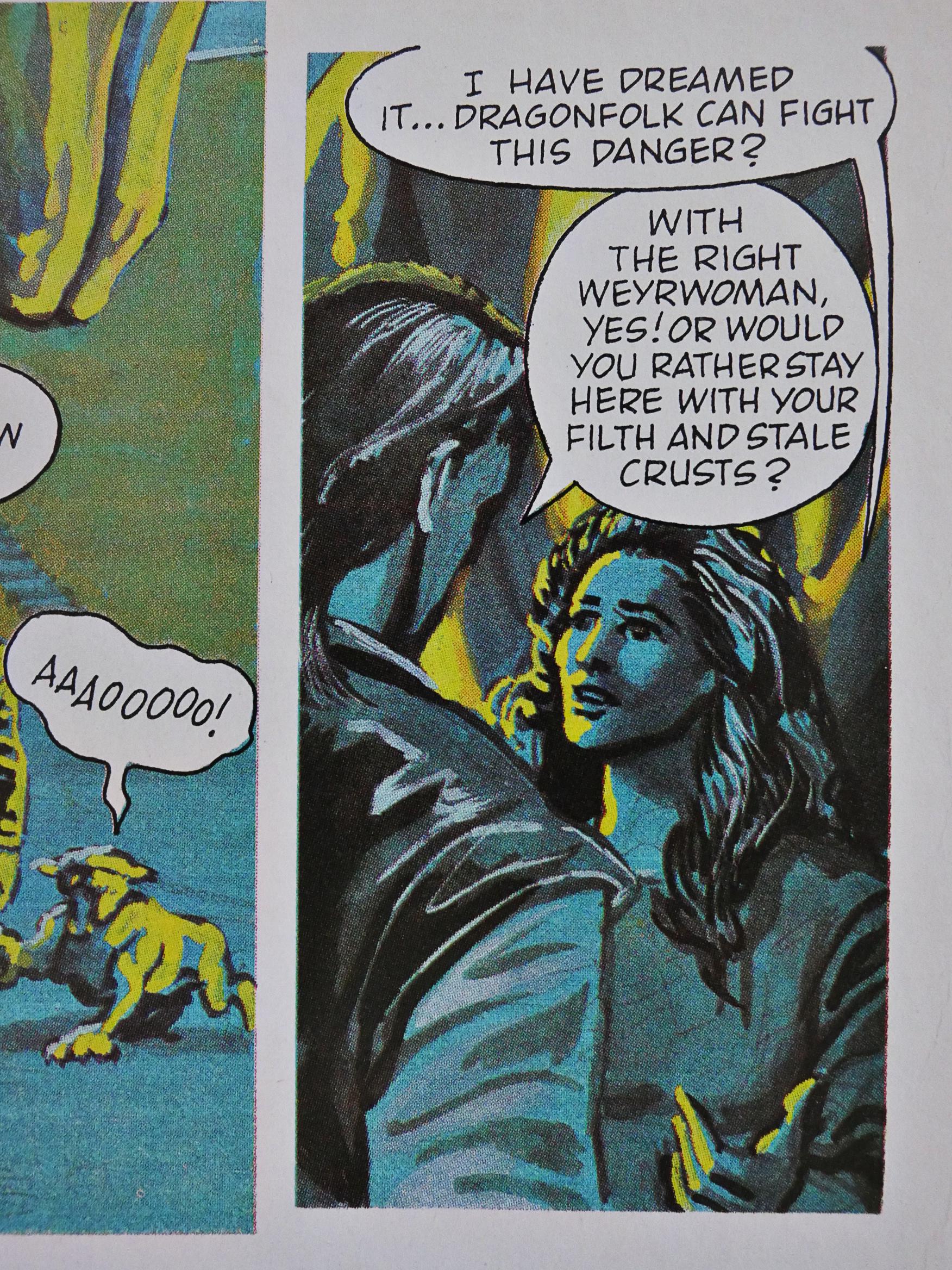

I love the subtle way Chelsea changes his art style when he’s depicting his dreams. The outlines become heavier and the other lines become wispier, but clearer.

Chelsea attempts submitting the story to Raw Magazine, I mean Shred: The Tattered Remnants of Comics and is rebuffed by a bubblegum blowing Art Spiegelman. Which seems kinda out of character, which makes it even funnier.

A couple pages later, Chelsea drops the Shred pretence and just namechecks Raw.

It did!

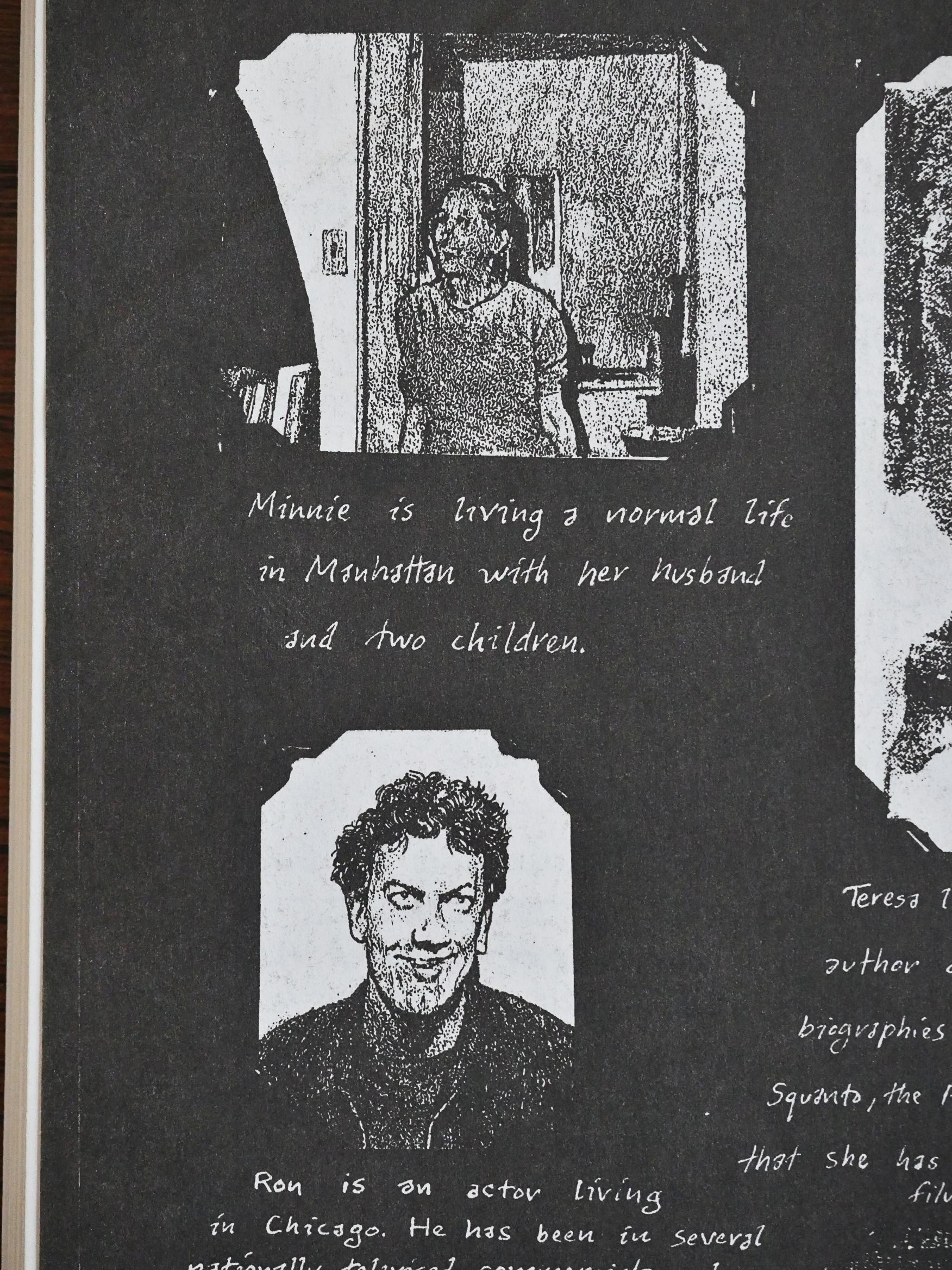

On the final two pages, we get a “where are they now” summary of all the characters, which would seem to point to this being “real”?

On the other hand, some of their fates don’t seem very likely.

Eclipse published a collected edition of this as well, and it’s also been published by Reed in 2003. He’s also published a book called Perspective! for Comic Book Artists: How to Achieve a Professional Look in your Artwork, which er, is something, I guess, but he’s not been a very prolific comics artist after this book.

I think I’ve read them all, also the 24 hour comics, and they’re pretty good. This probably remains his major comics work.

Here’s Rich Kreiner from Comics Journal #147:

he first of four installments of David Chelsea’s autobiographical romance shows him to a struggling commercial anist in New York who is trying to maintain a long-distance relationship with… Actually, David Chelsea appears as just a guy trying to get laid.

[…]

I find myself continually making a disconcerting distinction between Chelsea the creator and Chelsea the character. The level Of passion, the Objectivity Of eye and hand, and the coolness of execution permit the schism. Such a distinction is less felt with the best comic book autobiographers because of not only their skilled intensity. Compare Harvey Pekar’s powerful presence in his most trifling stories. Or compare the empathy so easily invoked in Chester Brown’s Playboy tales. There’s the absolutely vital funkiness infused by Julie Doucet, the raucous breast-beating of Joe Matt, the morally uncluttered yarns of Dennis Eichhorn, and let’s not even get started with Crumb, okay?