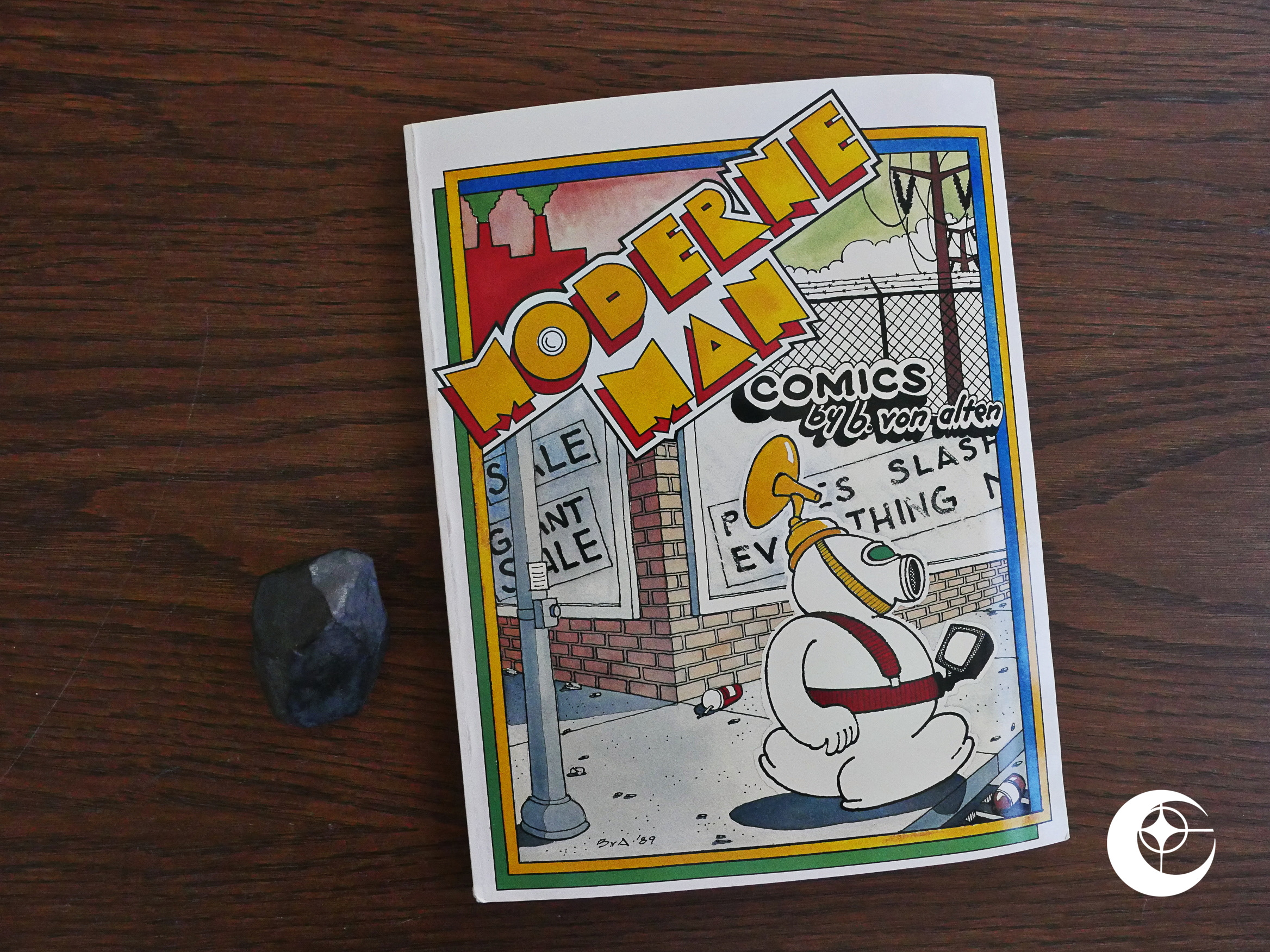

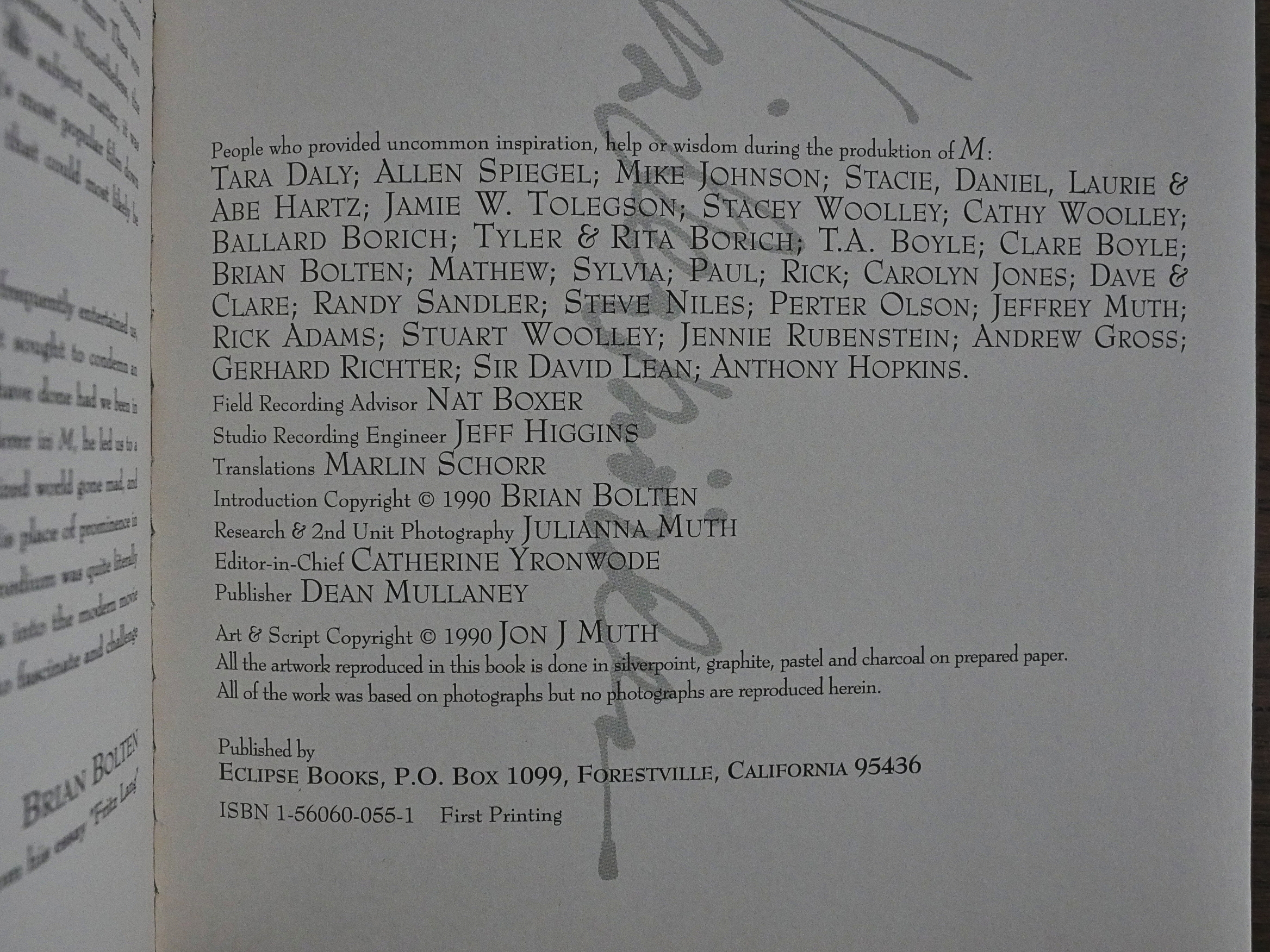

Words Without Pictures (1990) edited by Stephen Niles.

What’s this then? A book book? A book book book?

It’s co-published with Arcane Books, which is Steve Niles.

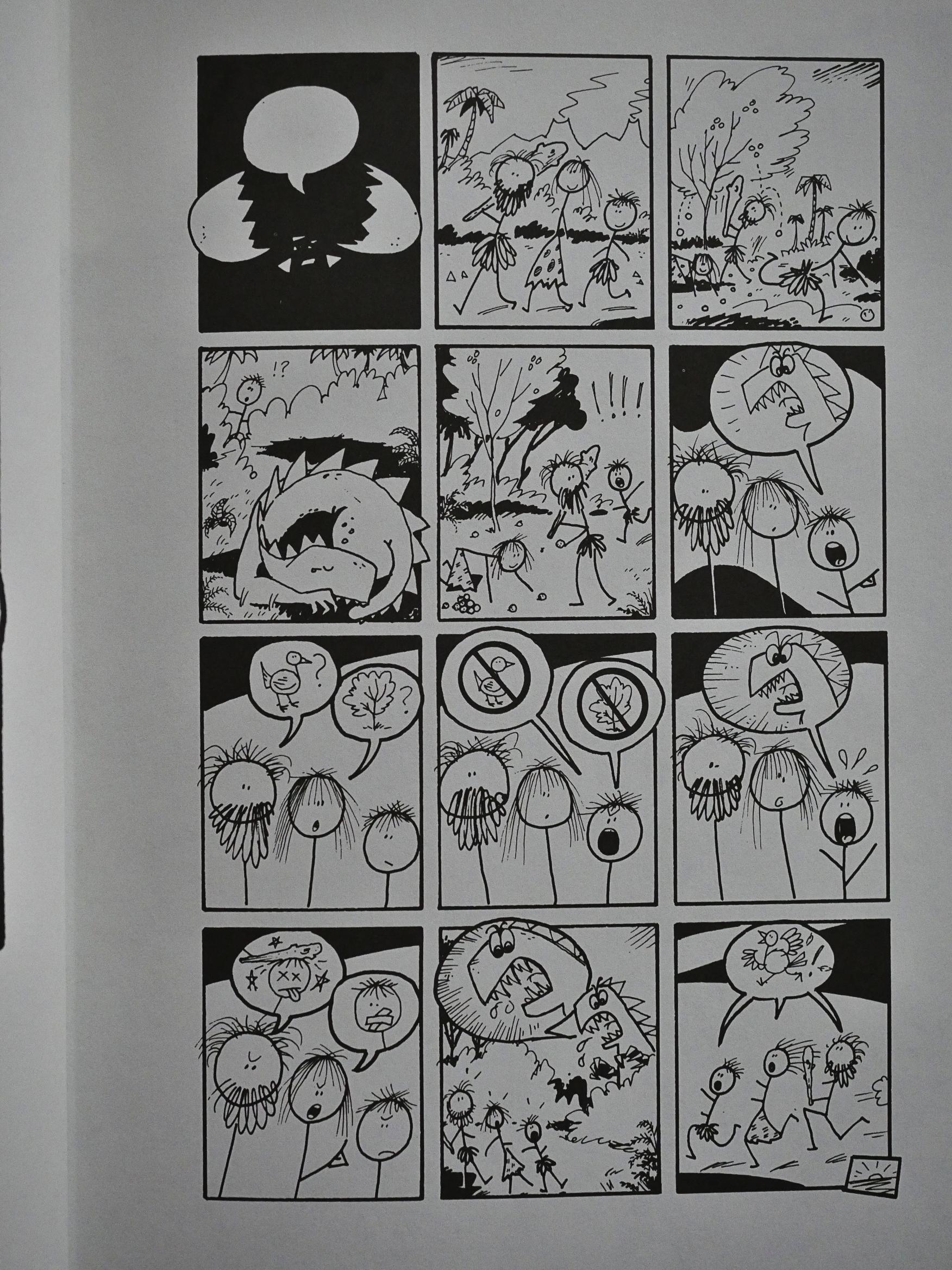

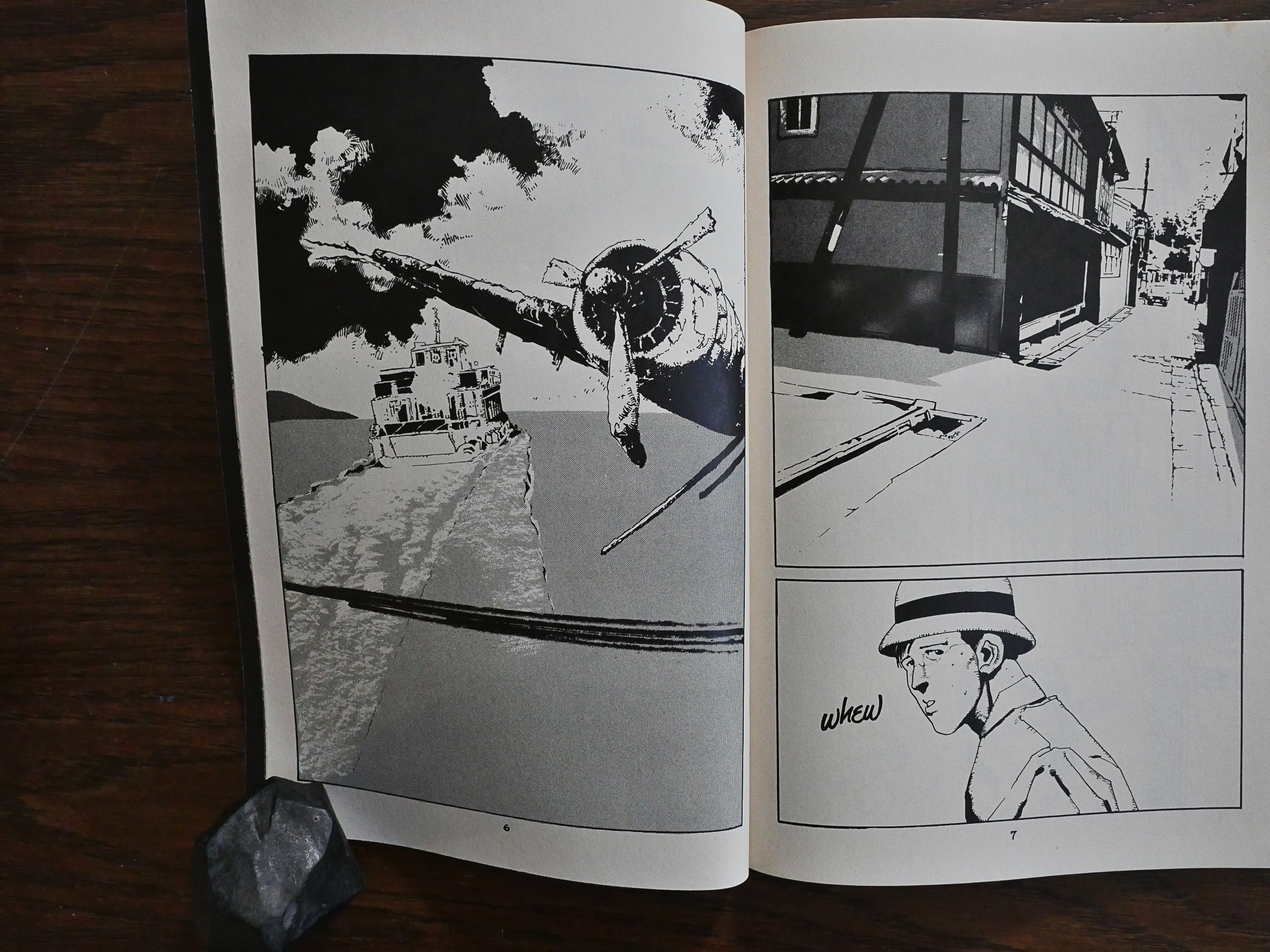

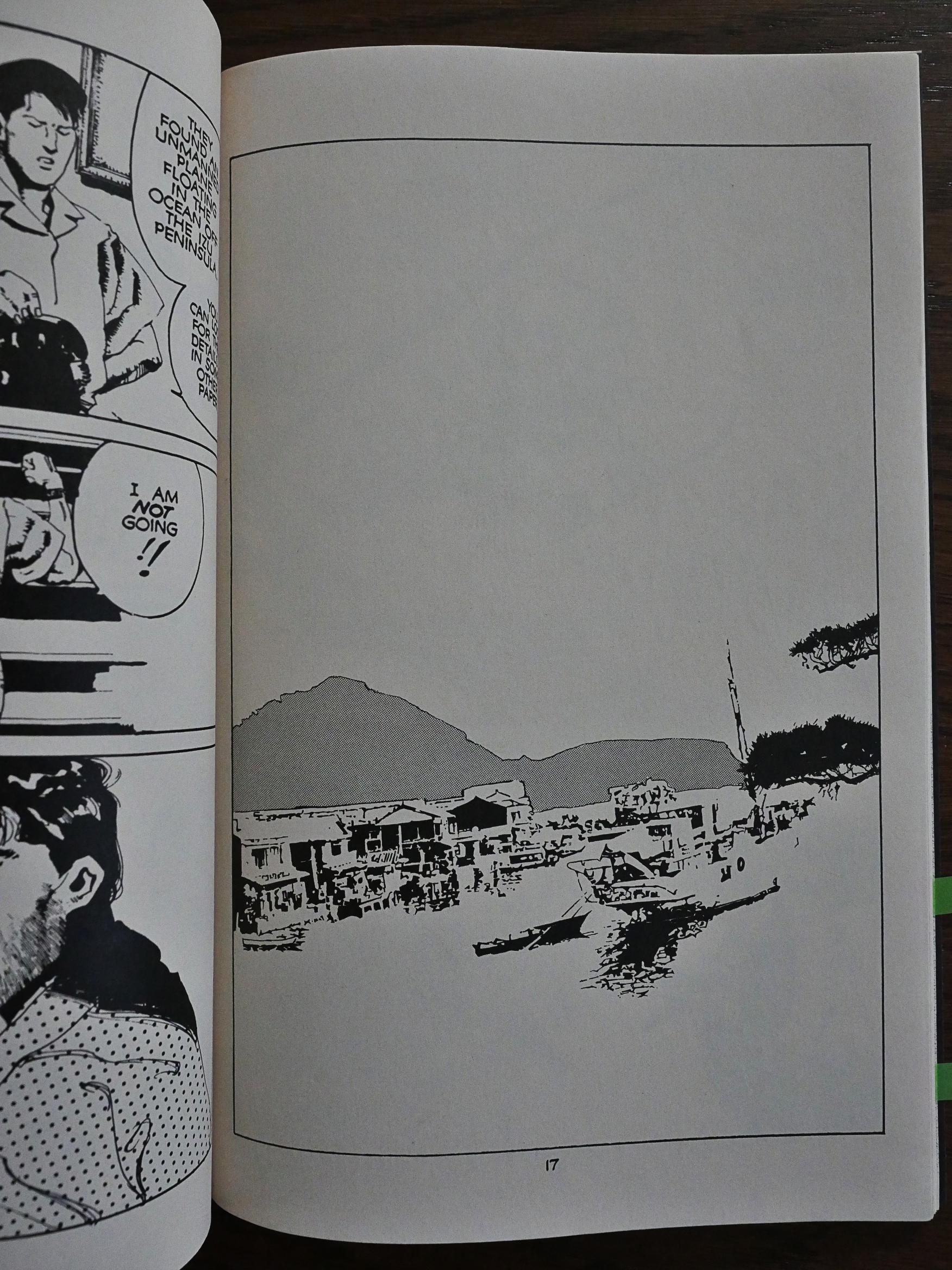

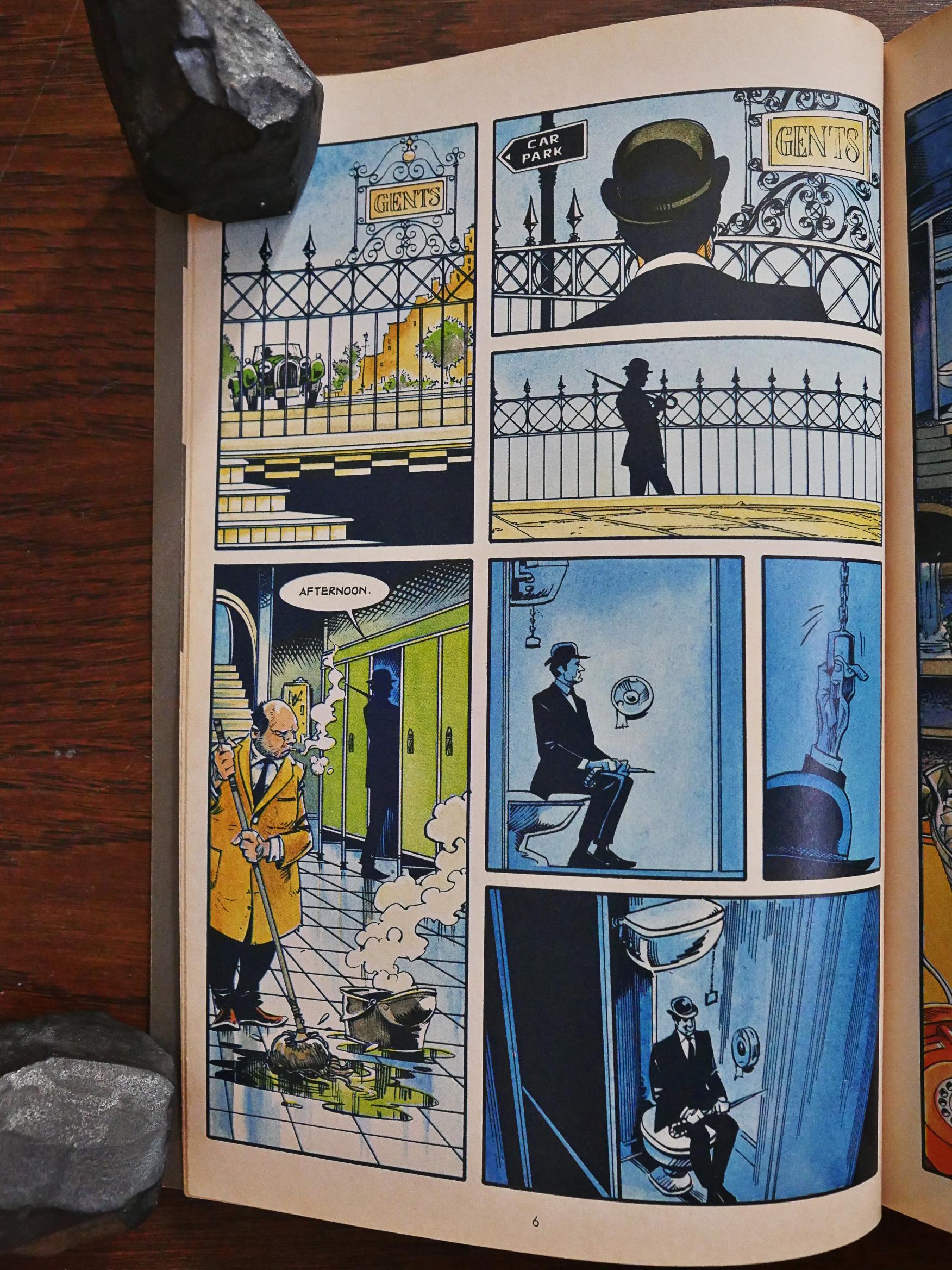

*phew* Comics! Matt Feazell does the introduction appropriately enough with a wordless single page strip.

But then we’re on to the main portion.

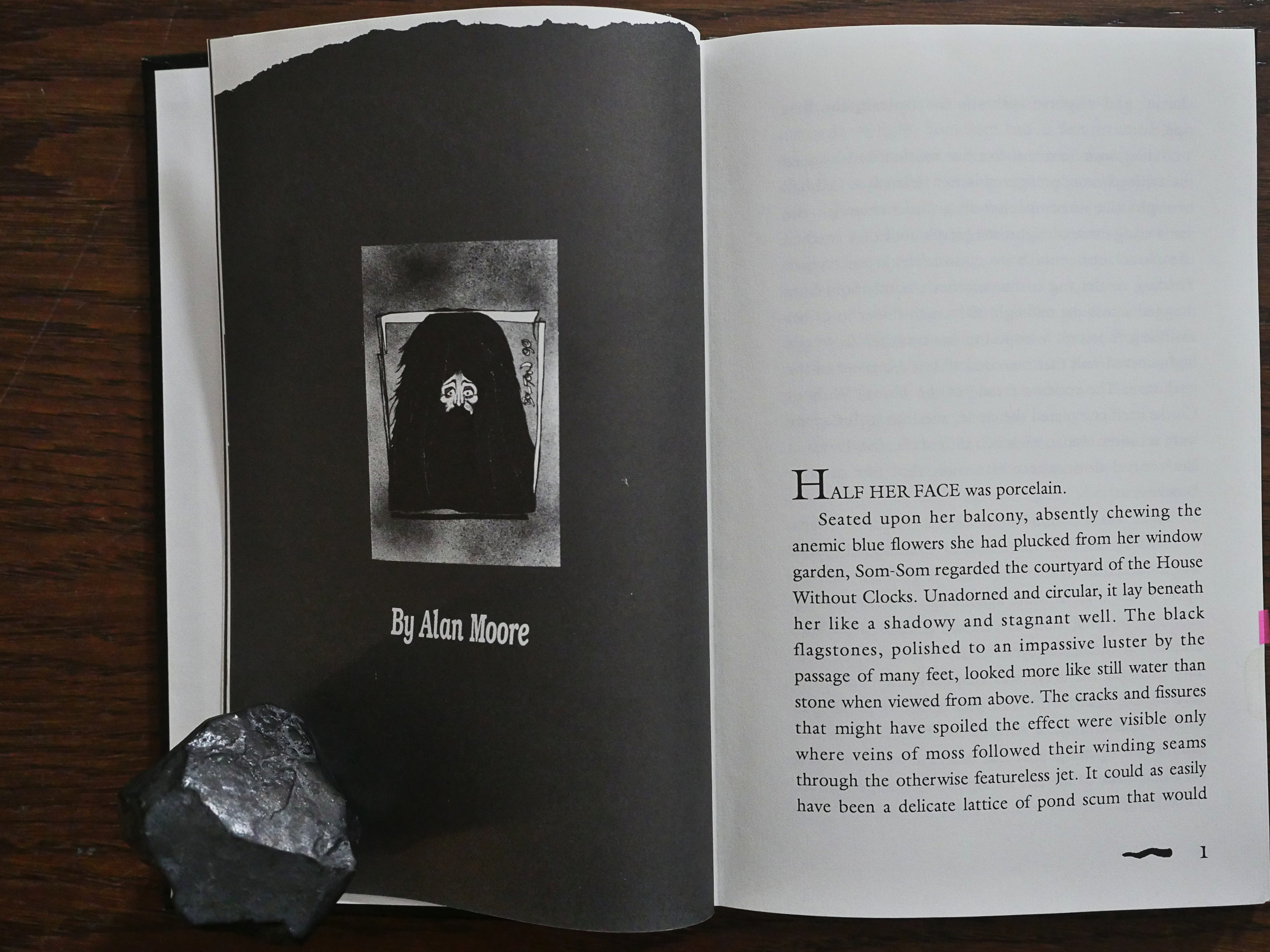

This is basically a short story collection from some well-known and some not so well known people who usually do comic books. It’s a 170 page book, and the first seventy pages are written by Alan Moore, so it’s not hard to guess at the impetus for the book.

I think this is the only thing Eclipse published in this format, so that’s kinda interesting.

I mean, if you’re interested in that kind of thing. If not, not? I guess?

I haven’t read any of Moore’s prose works before, but it’s pretty much like you’d imagine. Lots and lots of adjectives and adverbs and phrases like “spectrally perfumed corridors”. That makes sense, I’m sure.

Or you could write “She lit the lamp.” That’s another way to write that.

Just saying.

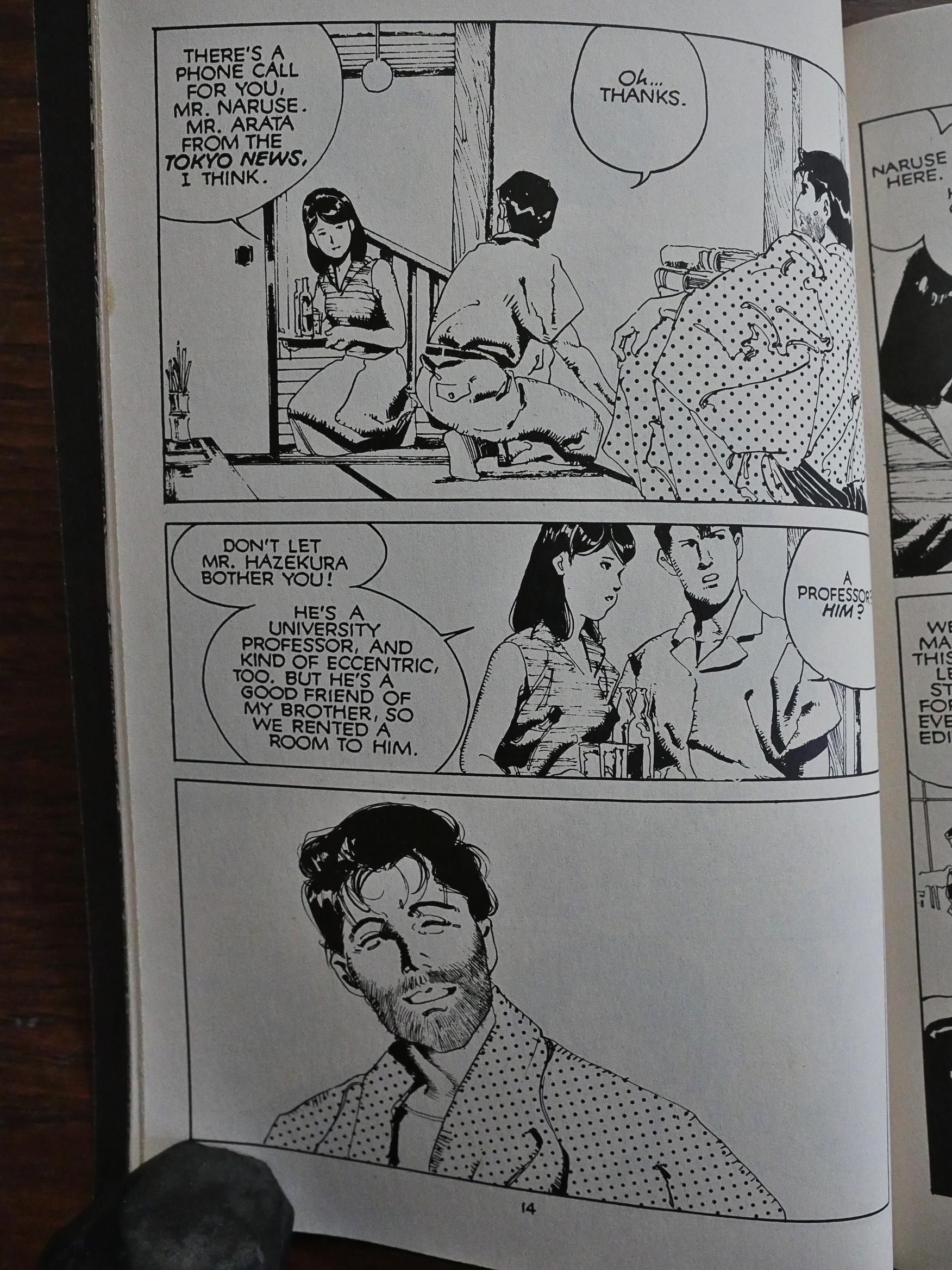

John Bolton contributes caricatures of the authors, so here’s Neil Gaiman with huge sunglasses.

It’s a relief reading straightforward prose after the over-cooked Moore mess. It starts off amusingly enough (above some scallywag is explaining what the collective noun is for somebody who works in a bank), but then things turn horrific. It’s a slow burner of a story, and it’s quite successful.

So I guess this is a horror anthology and not an anthology of general literature, which I had assumed?

Gaiman does an afterword to his story, and is the only one who does.

Jon J Muth writes four poems.

Some of Bolton’s portraits are weirder than others. I guess these are meant to be funny, but since I don’t know how she looks in real life, it’s kinda obscure. But it’s nice. It’s more Sienkiewiczian than Boltonish.

Mark Evanier’s story stands out… but not in a good way. It reeks of professionalism. It uses one (1) metaphor, and sticks to it like a nail on Pinhead. I wonder if this was a pitch for a quirky TV special or something. The characters are TV deep.

Let’s see if I can find any reviews for this book…

Here’s one from Goodreads:

What an odd, compelling book! The stories are magnificent, there isn’t a bad story among them. The stories have themes around sadness, grief, fear, change, love, and sex. I really enjoyed this book! Interesting that the first story, by Alan Moore, was the only one that didn’t fully keep my interest, and I had the same experience with The Watchmen.

And here’s one from Amazon:

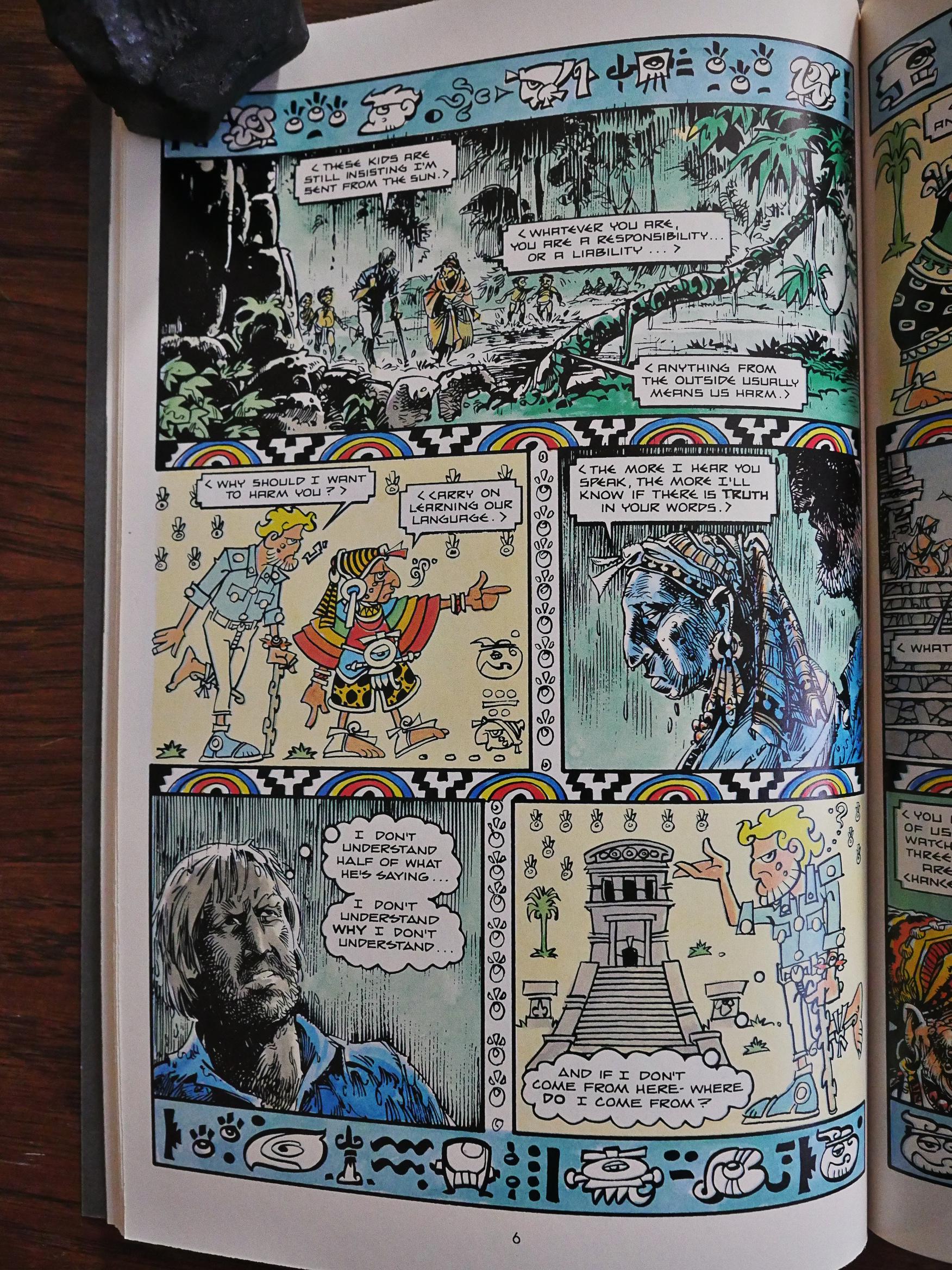

The best and longest story, and one that is worth the price of admission all on its own, is by Alan Moore. It is a vey strange and exotic story about a young woman in the orient undergoing a process that will put her more deeply in touch with her unconscious mind in order to turn her into a sort of Shaman. This story should appeal to fans of Moore’s Promethea.

Can’t find any substantial reviews, though.